The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 9 June 2017 11:22 am Bergino Baseball Clubhouse proprietor Jay Goldberg possesses the wryest of wits. In graciously inviting me to pull up a chair and talk about Piazza: Catcher, Slugger, Icon, Star at his one-of-a-kind shop a few blocks south of Union Square, he offered me the date of June 15. We would discuss my new book, of course, “and given that it’s the 40th anniversary of one of the worst days for both of us, we would certainly discuss that, too.”

How do you dispute intuitive scheduling like that? The symmetry, I agreed, was too good to pass up, and thus I will be there (and hope you will be, too) this Thursday night at 7 o’clock. Not coincidentally, I told Jay, June 15, 1977, inhabits the narrative of Piazza like a ghost. I’m not sure a person, especially a Mets-loving person, could have grasped the concept of a superstar franchise player being traded in the middle of his prime in the middle of a season for blockheaded management reasons if it hadn’t happened before.

In May of 1998, it was the Dodgers who were the blockheads. In June of 1977, it was the Mets who made their fans cry good grief.

This guy made for a Terrific catcher. The story of Mike Piazza as a legendary Met is informed by the precedent of Tom Seaver in a couple of ways. One, most obviously, is that Tom represented the previously unreachable precedent which Mike, to our way of thinking, was striving to match. Everything that was said about Mike’s prospective Hall of Fame enshrinement and number retirement tended to be placed in the context of Tom. “First Met since…” “Only Met other than…” The Seaver standard served as a relevant emotional metric, and Piazza was, by consensus, the first Met to measure up. Nobody announced in advance that the final Shea Goodbye pitch would be Seaver to Piazza, but when the ceremonial battery formed, and 31 joined 41 as the only two Mets to walk through the center field gate, it made total sense to us.

Cosmically speaking, I’d like to believe it’s no accident that Tom Seaver’s Hall of Fame induction and Mike Piazza’s major league debut came within a month of one another, on the back end of the Summer of ’92. The fact that the former event occurred on August 2 and the latter September 1 — with the bridge between them thirty days of unrelentingly crummy Metsiness that foreshadowed the annus horribilis ahead and, ultimately, the several years of toxic-spill cleanup that 1993 would necessitate in Flushing — struck me as too good to be serendipity. It’s why I started the story of Piazza in Cooperstown with Seaver; shifted it to Shea for everything that was going wrong with the team Tom had long before legitimized; and then moved the focus to Wrigley Field the day the Dodgers promoted the kid catcher who’d hit .377 for San Antonio and .341 for Albuquerque.

Within the book’s first act, I also sought to establish how difficult it can be to cast in bronze an eternal identity once you start taking your talents elsewhere…or if somebody is sending you and them away. Seaver’s image for the ages was always going to be tethered to the Mets in our hearts and minds, and the record books testified it wasn’t just our imagination running away with us. Yet fate kept finding bad terms for Tom to leave New York on. You think Seaver was thinking kindly of his Mets association forty years ago next week when he found out he was about to call Southern Ohio his professional home? When he pitched against the Mets on eleven separate occasions? When he sat in the dugout opposite theirs with a world title hanging in the balance?

Given the “go in as a Met” topic that hovered over all our talk of Piazza before 75% of BBWAA voters made the inevitable a reality — and Mike made it crystal clear whose cap he’d be wearing forever after — I thought it would be instructive to examine for my book how much of a sure thing it was that Tom Seaver, the Met of Mets, would himself go in as a Met. My conclusion is that, as one of Tom’s managers might have put it, it wasn’t a certainty until it was a certainty.

What was certain was I had to cut certain sections of my manuscript for space, and the extended Seaver discussion wound up being one of them. In commemoration of the 40th anniversary of one of the shall we say most memorable days Mets fandom has ever known, and in anticipation of a much happier night at Bergino Baseball Clubhouse, I decided to share what I wrote here.

***

Conceivably, it could have looked different, though there was a time that itself was inconceivable. That time was prior to June 15, 1977, a date destined to live in infamy among Mets fans of a certain age. It was the day Tom Seaver was traded to Cincinnati.

It never should have happened, not if you believed that some players and some teams were made for one another. Tom had been a Met for more than a decade by then, most of it under the ancient system in which ballplayers played ball and management did with them what it wanted. Then came free agency and, with it, the chance for ballclubs and ballplayers to improve their respective lots. Seaver wasn’t happy with how his club was running its affairs — shunning the opportunity to enhance the offense behind him — and he didn’t care for his suddenly outdated compensation package. In a nutshell, the man he worked for, Mets chairman of the board M. Donald Grant, didn’t care for what he considered Seaver’s uppity attitude.

The match made in heaven in 1966, when a pitcher’s name was pulled out of a hat in a special lottery on behalf of a franchise desperate for a transcendent figure, was on the verge of dissolution. The Mets had gotten lucky when Seaver’s original professional contract was voided by then-Commissioner Spike Eckert. Twenty-one year-old Tom, from the University of Southern California, found himself in a murky void, caught between the pro team that drafted and signed him, the Atlanta Braves, and USC, where his amateur status hadn’t fully worn off. The Braves couldn’t keep Seaver, but Seaver, it was decided, couldn’t be kept from pursuing his career. Thus, the lottery that every team besides Atlanta was invited to join, yet only three did: the Cleveland Indians, the Philadelphia Phillies and the New York Mets. All it took to get him was a willingness to match the $51,500 bonus the Braves had planned on paying him and fate.

Fate sided with the Mets. It was their name on the slip of paper Eckert drew from the most charmed hat in Mets history. They got Seaver. Seaver went to Triple-A Jacksonville for a year, then made Flushing, Queens, major league a year later. The team that had never finished higher than ninth prior to Seaver’s arrival…well, they finished tenth with him, but one could only recoil at imagining where they might be headed without him. Fortunately, for ten years, the Mets never had to seriously contemplate such a question.

Seaver pitched. The Mets improved. Hodges, beloved Brooklyn Dodger and Original Met, came home to manage him and Harrelson and Koosman and Grote and a clubhouse of young players who possessed talent but craved guidance. Gil guided. The Mets improved exponentially. Seaver excelled. The Mets followed suit and won a world championship in 1969 that could hardly be fathomed and would never be forgotten. Then the Mets leveled off. Seaver didn’t. He kept pitching and kept excelling. His right arm was as strong a reason as any that the Mets stitched together another pennant, this one under Berra, in 1973. Through a torrent of innings and a paucity of runs and even in the aftermath of the tragic death of his professional mentor Hodges, Seaver kept going.

In the spring of ’77, though, he was going out the door. Trade rumors began to boil over that spring. The pot was stirred to excess by Grant’s ally, the legendary Daily News columnist Dick Young. Young invoked a supposed jealous streak Tom’s wife Nancy maintained toward Nolan Ryan’s wife Ruth. Ryan, the Met foolishly dealt to the Angels half-a-dozen years earlier, had grown into a star pitcher in California. Young’s story had it that Nancy Seaver was upset Ruth Ryan’s husband was getting paid more than her own. Tom didn’t care for this tactic whatsoever. His demand to be traded was set in stone. Late on deadline day, June 15, he went to Cincinnati in exchange for four players who weren’t and never would be the equivalent of one Tom Seaver.

“As far as the fans go, I’ve given them a great number of thrills,” an uncharacteristically emotional Seaver told reporters in front of the locker he was compelled to clean out, “and they’ve been equally returned.” It was a transactional assessment, but it was also correct.

The Mets were back where Seaver found them when he joined them: in the cellar. They struggled in his absence. They might have struggled anyway, given Grant’s aversion to modernity. The organization was rotting from within. No viable reinforcements were graduating from the minors and no significant help was being obtained on the open market. The Mets of the late 1970s were probably doomed with Seaver or without him. But the Mets without Seaver, on principle and on the field, were unbearable.

Tom thrived in Cincinnati, no matter how odd his familiar form appeared trimmed in red. He pitched a no-hitter for his new team. He pitched them into the playoffs once, to the best record in baseball another time…but not the playoffs, amid the bizarre split-season contrivance of strike-sundered 1981 (a baseball version of the electoral college trumping the popular vote). Wear and tear was finally showing on him in 1982, his sixth season with his second club. The Reds, rarely less than very good for a generation, had finally stopped winning. They didn’t necessarily need to continue paying an all-time great starting pitcher whose every-fifth-day effectiveness was ebbing.

The Mets had undergone many changes in Seaver’s absence, though you couldn’t tell it by the National League East standings. They continued to dwell near the bottom of them, but behind the scenes, things were very different. Grant was gone. The team had been sold. The new owners hired a general manager, Frank Cashen, determined to overhaul the entire operation. Cashen was building from within, drafting and nurturing a contender, occasionally shelling out for external help to patch over the rebuilding process. In the winter heading into ’82, he did some headline-grabbing business with Cincinnati, taking off their hands the bulging salary demands of George Foster, an RBI man of the highest order. It was a crowd-pleasing move. That it didn’t work out — Foster’s production couldn’t have diminished any faster had that been the plan — didn’t mean it wasn’t a good idea. Rebuilding was taking its not-so-sweet time. The goodwill attached to the 1980 regime change faded almost as quickly as Foster’s talent for driving in runs. Nineteen Eighty-Two marked the sixth consecutive year of the Mets holding down one of the two lowest spots in their division. A diversion couldn’t hurt.

Especially one that could still pitch a little.

Five-and-a-half years after the unthinkable trade of Tom Seaver from the Mets, Tom Seaver was traded to the Mets. All was right with the world again, save for the standings. The Mets remained well south of contention as 1983 dawned, but finishing last with Seaver loomed as so much more pleasant than finishing last without him. Opening Day told the story beautifully. Shea Stadium was packed. Public address announcer Jack Franchetti introduced “Number Forty-One” as the starting pitcher. No more needed to be said. Tom Seaver, in his native colors of blue and orange, strode down the right field line from the home bullpen. He stepped on the mound and threw to Pete Rose, these days a Philadelphia Phillie. His first pitch was a strike. His return was a home run.

Seaver the second-time Met was a phenomenon. Then it was just how it was supposed to be. Tom’s presence blended into another sixth-place finish. He still pitched well, but the team still didn’t score much for him or any of its pitchers. The losing continued. Cashen continued to conjure. The Mets’ slogan, when they were sold to a group headed by Nelson Doubleday and Fred Wilpon, was “The Magic is Back.” That prematurely ballyhooed wizardry was about to manifest itself for real.

In May, the Mets promoted Darryl Strawberry, the first draft pick Cashen had made for the Mets. Strawberry probably wasn’t yet ripe, but the season wasn’t producing a bumper crop of wins. Darryl could learn in New York as well as he could in Tidewater. In June, on the sixth anniversary of the Midnight Massacre that made Seaver an ex-Met, the GM stunned baseball by making Keith Hernandez an ex-Cardinal. Hernandez was an in-his-prime Gold Glove first baseman and clutch hitter. He was exactly the kind of player Seaver lobbied the Mets to acquire when free agency dawned. Cashen all but pulled him out of a hat — more magician’s than commissioner’s — giving up two young pitchers he could do without. St. Louis didn’t want Keith any longer and New York didn’t particularly care why.

Last place wouldn’t be escaped in 1983, but by August, the Mets no longer looked like long-term occupants. Strawberry was learning. Hernandez was getting comfortable. Others were coming around. Seaver was Seaver. A team on the rise and a legend in residence. For the first time since Tug McGraw implored a city to Believe, Mets fans had the sense they really could, and not live to regret it.

Then they were consigned to a sickeningly familiar state of disbelief. Tom Seaver, missed for so long, welcomed back so warmly, was gone again. It wasn’t as ugly as the first time it happened, but it was awful enough. This time, the culprit amounted to a whopper of a clerical error. That strike that cost Seaver’s Reds a postseason berth in 1981 yielded a strange compromise between players and owners called the compensation pool. In essence, if Team A signed a free agent from Team B, Team B was entitled to pick a player from Team Z, a.k.a., a team that was otherwise uninvolved in the initial transaction if Team B so chose.

For example, the Toronto Blue Jays opted to engage the services of pitcher Dennis Lamp, previously of the Chicago White Sox. The White Sox, under the terms of the Basic Agreement, were allowed to seek compensation from a pool of players left unprotected by everybody else. Floating in that pool was a 39-year-old pitcher who had just had a pretty good season for a last-place team. Because of his age, let alone his symbolic importance to his team, he seemed like the kind of player another team would leave alone.

The Mets protected the names that represented their immediate future in that compensation draft. They weren’t going to expose a Strawberry or a Hernandez or any of the youngsters who had just arrived or were on their way. A veteran like Tom Seaver, however, seemed safe enough to not technically guard. Who would dare pluck the Mona Lisa from the Louvre?

If the Louvre was careless enough to leave its doors unlocked, the Chicago White Sox, that’s who. They went for the masterpiece of veteran pitchers, Tom Seaver. Without warning, without an M. Donald Grant or a Dick Young stoking the tabloid fires, Seaver was again an ex-Met.

If January 20, 1984, the day Seaver’s contract was transferred to Chicago’s American League entity, didn’t live in infamy, it resided not too far down the block from June 15, 1977, in the same neighborhood of dates and events that made Mets fans shudder to their core. On both occasions, the Mets rolled out the moving van and packed their greatest player ever off to a distant city. It wasn’t as obnoxious or as obvious as what happened amid the Grant-Young maneuvers that sent Seaver to Cincinnati, but the result was the same. Tom Seaver was no longer a New York Met.

In short order, as conspiracy-theorists wondered just how much of an accident Seaver’s departure really was, the New York Mets revealed themselves as no longer a last-place ballclub. All of Cashen’s planning and planting began to pay off in the summer ahead. Under a new manager, Davey Johnson (who may or may not have wanted a strong figure like Seaver exerting influence inside his youthful clubhouse, if you bought the conspiratorial thinking), the Mets challenged convincingly for the NL East title in 1984 until the season’s last week. They challenged even harder in 1985, falling heartbreakingly short on the last weekend. Then, as if it had been marked as the destination on their road map all along, they blew the doors off the division in 1986 en route to winning their first World Series since 1969.

It would be simple enough to say that after a while, Mets fans didn’t miss Tom Seaver, not when their ballclub was leaping from 68 wins to 90 to 98 to 108 and the brassiest of brass rings, yet that is to not fully appreciate fan loyalty. Sure, there is the uniform, and there is the cap, and there is a fealty to success. The fan can be guided by the same transactional impulses as front office architects and free agent players.

But some things you don’t take away and expect to go unmissed. You don’t take away a first love. You don’t take away a first star. You don’t go to the trouble of bringing back the FRANCHISE POWER PITCHER WHO TRANSFORMED METS FROM LOVABLE LOSERS INTO FORMIDABLE FOE only to let him go a year later. You also don’t not notice that Tom Seaver, who left New York the second time with 273 career wins on his ledger, wore garish horizontal stripes and a shirt that screamed SOX on the hallowed occasion of his 300th victory. It took place in New York, in front of Mets fans, but the Mets fans were one-day visitors to Yankee Stadium, same as Tom. The milestone was a fine moment, but it was also indicative of a right arm that was still churning out productive pitches. During the season of No. 41’s No. 300, the Mets were battling St. Louis for first place. Seaver was in the process of winning sixteen games for the White Sox. The Mets finished three games behind the Cardinals. The math suggests those wins of Tom’s would have looked much more attractive adorned by Mets gear. The 1985 Mets were formidable foes on most fronts, yet relied on soft-tossing Ed Lynch and still-learning Rick Aguilera for starting pitching depth down the stretch. They weren’t terrible, but Tom was still Terrific.

When Seaver, having reached the age that he’d been wearing on the back of his jersey since he was 22, requested another trade, in 1986, it was to be closer to his home in Connecticut. The Mets didn’t need much of a boost that season, so he was off to Boston, mentoring a meteorically rising righthander named Roger Clemens (“At home, I’ll tell him what time the game starts. On the road, I’ll tell him what time the bus leaves,” is how Tom described the extent of his guidance) and helping another team to the playoffs until his right knee, the one that absorbed dirt from the pitching mound when his motion was ideal, gave out in September. Tom was forced to sit inactive in the dugout during the ensuing World Series at Fenway Park and, yes, Shea Stadium. Seaver the Red Sock was a footnote to the circumstances of the Mets’ second world championship seventeen autumns after he was the heart and soul of the first one. Had he, instead of sacrificial lamb Al Nipper, been available to pitch for Boston in Game Four, it could be legitimately wondered whether the Mets would have won that second world championship when they did.

Seaver versus the Mets in the World Series…shudder.

Desperation less than fate boomeranged Seaver to Flushing the following June. His recovery, along with more ownership shenanigans — collusion had squeezed the free agent market of its usual brisk high-dollar activity — seemed to quietly end his career. But the Mets, trying to defend their title, were short of starting pitching. Injuries were taking a toll, and there was a spry gent up the road in Greenwich who knew how to get hitters out and was quite familiar with the route to Shea. The Mets and Seaver reunited one more time, conditionally. Tom would have to pitch his way into shape. He and they would have to be convinced that at 42, No. 41 could still do what he’d been doing all those years before.

It didn’t work out. Seaver started an exhibition at Tidewater for the Mets. He didn’t look great. He pitched what were called simulated games, throwing his best stuff to a cadre of bench players. He didn’t look right. Backup catcher Barry Lyons in particular wracked him around. If Seaver couldn’t handle little-known Lyons, what were the chances he could tame the Hawk, Andre Dawson, or the Cobra, Dave Parker? Finally, on June 22, 1987, at a press conference called not because of a feud with a feudal-minded executive and not because of a too-clever-by-half paperwork omission, Tom Seaver and the Mets parted ways, at last more or less on the same page. Their relationship was described as strained in the press — Cashen and Johnson were by no means Grantlike villains, but they hadn’t exactly fallen over themselves to keep Tom on their team when he still had some competitive pitches left in that right arm. Yet in front of the cameras and microphones, only the most conciliatory of sentiments were uttered. “The single most important player in the history of the Mets,” the GM declared, was “retiring as a Met.”

Considering how rarely any player retired as a Met, it was more of an achievement than face value would imply. Rusty Staub received a knowing ovation on Closing Day 1985. Otherwise, Koosman ended with the Phillies, Harrelson (before returning to Shea to coach) played his last games with Texas, Grote bounced to Los Angeles, then Kansas City…and so on. Cleon Jones went out with the White Sox, Tommie Agee faded away as a Cardinal, Ed Kranepool was allowed to walk and keep walking after parts of eighteen seasons as a Met — the first eighteen seasons there were Mets. If Tom Seaver couldn’t pitch any longer as a Met, then retiring as one was the next best resolution in light of the wary ride the Franchise and the franchise had intermittently shared over the previous decade and change.

Seaver’s 41 had been out of circulation since the end of the 1983 season. Nobody wore it in Queens during his Cincinnati exile, either. Cashen announced the number, like he who wore it so elegantly, would be retired. That ceremony would wait a year. The Hall of Fame would wait five. Given the firmly established rapprochement between former pitcher and old team, there could be no doubt that Tom Seaver would enter that august institution embodying the New York Mets. The statistics wouldn’t have it any other way and there was no discernible reason for the twice-spurned Seaver to want it any other way.

It would be a first. Since the founding of the Mets a quarter-of-a-century earlier, several men with blue-and-orange ties had gained Cooperstown induction: Warren Spahn, Willie Mays, Yogi Berra and Duke Snider as players, Casey Stengel as a manager, George Weiss as an executive. None, however, was in primarily by dint of what he accomplished as or with the Mets. Ralph Kiner remained on the BBWAA radar for a necessary fifteenth ballot, his last eligible year to be voted on by the writers, perhaps because he was a highly visible Mets broadcaster, but it was Ralph’s production as a Pittsburgh Pirate that finally earned him election in 1975. Lindsey Nelson came to be so closely identified with the Mets between 1962 and 1978 that Yankee outlet WPIX-TV enlisted his services on August 4, 1985, to call Seaver’s 300th win. Nelson received the Ford C. Frick Award in 1988, Cooperstown’s paean to excellence in broadcasting. It was a substantial honor, but not exactly the same as being elected to the Hall (and Lindsey was a national broadcaster of considerable renown before and outside his work with the Mets).

Tom Seaver went into the Hall of Fame in 1992 because of what Tom Seaver did as a Met. It was all enshrined so as to be marveled at: 198 of 311 wins; 2,541 of 3,630 strikeouts; all of his Cy Youngs; his only World Series ring; and, if you still weren’t sure, the NY on the cap on the plaque. That couldn’t be traded for Pat Zachry, Doug Flynn, Steve Henderson and Dan Norman, and it couldn’t be left exposed as potential compensation because Dennis Lamp lit out for Canada.

***

Out in California, Tom recently received a visit from Bill Madden, who wrote about it in the Daily News. If you wish to catch up with the greatest vintner to ever toe a big league rubber, you can read about it here.

The recent passing of Frank Deford brought to mind a profile the acest of ace reporters wrote for Sports Illustrated in 1981, while Seaver’s Reds “best record in baseball” campaign was on hold due to the summerlong strike. It captures a fascinating moment in time for a Met in exile. I recommend you click here and read it.

To reiterate, I will be joining Jay Goldberg at Bergino Baseball Clubhouse, 67 E. 11th St. in Manhattan, to discuss Piazza: Catcher, Slugger, Icon, Star, Thursday night, June 15, 7 PM. No doubt Tom Seaver will come up. No doubt, also, that Jay will put that night’s Mets game on in the store once the official chatting winds down. Copies of my book will be available from Bergino and I’ll be happy to sign. I really do hope you’ll swing by. The details are here.

by Greg Prince on 8 June 2017 10:05 am My preferences have little impact on determining the outcome of baseball games I sit down to watch, or maybe you’ve noticed the unbroken winning streak the Mets haven’t been on for the past five decades. Nevertheless, I decided I was going to be reasonably content with a Mets loss Wednesday night provided Zack Wheeler and I got out of it what we needed. We didn’t need Yu Darvish mowing down the Met lineup, but I took that as a given. What wasn’t so obvious going in was what Zack would do. In 2017, we’ve learned to expect nothing from Mets starting pitching. Get any more than nothing, and how can you not be sort of satisfied?

Darvish was Darvish for the first nine Met batters, each of whom politely took a turn and made an out across the first three innings. Wheeler was the Wheeler we anxiously clench our fists over in his initial inning on the mound. We don’t shake these fists, but we do clutch our anxieties inside of them. How many balls, Zack? How many baserunners? How many gosh darn pitches you gonna throw? For other Met starters, the pitch count might get your attention if it appears alarming. For Zack, we automatically keep track.

The bottom of the first in Arlington was vintage Zack, which is to say borderline agony. Four pitches for a single. Six pitches for a walk. A first-pitch single to Elvis Andrus, which was good news/bad news. Only one pitch and the runners only moved up a base, but oy, the bases are loaded, nobody is out, Zack is in trouble. After Jacob deGrom, the putative ace of the staff, was shellacked the night before, how could the bad news not overwhelm the good news in a matter of pitches?

Wheeler would answer. He’d need six pitches to produce a fielder’s choice groundout that scored the first Texas run, and then exactly one more for a double play grounder that curtailed the damage. Every other Mets pitcher, I’d be thinking, all right, we gave up one run. With Wheeler, I was an adding machine: let’s see, eighteen pitches…if he can rein it in, he can go at least five, maybe six.

Count Zackula had me paying less attention to my fingers and toes as the innings went by, because it was no longer about how many pitches he was throwing, but how well he was throwing them. That he did very well. Zack was in command in a way I’ve seen few Mets steer a start this year. He knew what he was doing on the inside of the plate. He fooled Texas hitters when he had to. He was economical, even. He was what he had to be, maybe what he is about to be. Six years since he was traded to the Mets and hailed as an ace-in-waiting, perhaps his future has arrived.

Zack Wheeler is the best starting pitcher the Mets have right now. Until his start against the Rangers, that was by default. For the moment, in the wake of a start where he got better the longer he went, it is a title rightly bestowed. Zack gave the Mets seven full innings on 108 pitches. Over the final six he threw, he allowed only four hits (three of them singles), two walks and no runs. He transcended serviceable and veered toward masterful.

Darvish, meanwhile, continued to be very good, but decidedly imperfect when it came to facing, if you’ll excuse the expression, the Mets’ designated hitter, Jay Bruce. For the first eight innings, our gloveless native Texan was also our lone star on offense, belting two home runs, one with a man on. We had a 3-1 lead through seven marvelous Wheeler innings. The outstanding outing I’d hoped for didn’t have to be mutually exclusive from defeating Darvish.

As long as they insist on silly rules in American League parks, maybe we could have ended it there, neat and tidy. But no, junior circuit baseball encompasses nine innings, however bastardized their lineups, so it came to pass that when Wheeler was removed and Jerry Blevins entered, the game was still up for grabs. Alas, in the bottom of the eighth, good ol’ Jer’ gave up a single to Nomar Mazara and a home run to Robinson Chirinos. This revolting development fit snugly within the prevailing sense that nothing ever goes right for the Mets, yet somehow I didn’t feel overly distressed about the bottom line. Wheeler was still wonderful during his seven innings. No, they couldn’t take that away from him. Or me.

And, surprise of surprises, the Mets didn’t proceed to find a way to lose. Blevins got out of the eighth and the Mets did something constructive with the ninth. With one out, Lucas Duda doubled authoritatively down the right field line off Matt Bush and immediately gave way to pinch-runner Matt Reynolds. With two out, Curtis Granderson patiently elicited a seven-pitch walk after being down oh-and-two to the Rangers’ closer. Jose Reyes, whose major league career commenced in this very same facility fourteen Junes and who knows how many corporate identities ago, was up next, attempting to wring a little more life from what remains of his professional tenure. Jose has earned his way to the bench, but he was in the lineup Wednesday night. Prior to the ninth, he’d done little to liberate himself from the pine on a going basis, par for the sad course of late.

On Tuesday, SNY showed a delightful flashback to the evening in 2003 when a highly touted 19-year-old shortstop alighted in Arlington to make his Met debut, the Amed Rosario of his time, you might say. You couldn’t miss the smile or the potential on Kid Jose. Then the 2017 camera spotted a reserve infielder, on the edge of 34, sitting forlornly in the dugout, not hitting, not happy. You could have penciled in your own thought bubble of despair. Jose’s looked slow in the field, lost at bat and head up his ass jogging to first, but — and this is not intended as faint praise — he still appears to be a helluva teammate. When another Met scores, he’s the most animated of fans. He greeted Bruce like a brother when he went deep. He does it with everybody. Nobody is more ebullient in congratulating a colleague, nobody seems to enjoy his fellow Mets’ successes as much. It reminds me warmly not only of vintage Jose from 2006 (when he was regularly on the receiving end of enthusiastic handshakes and hugs), but of the late summer of 2016. It wasn’t so long ago that Reyes was hailed as the veteran team leader, he and Asdrubal Cabrera praised for getting and staying on Yoenis Cespedes, and the three of them setting an example for all to Do Your Thing, as the clubhouse slogan went.

We haven’t seen much of Cespedes lately; Cabrera of these days isn’t the Cabrera of those days; and Reyes is back to craning his neck to get a gander at .200. You can’t as effectively urge others to Do Their Thing when you can’t do a thing at all.

As the ninth unfolded, I had the sense it would be slumping Jose up with the game on the line, aging Jose in the spotlight in the stadium where it all began for him. I had a sense Granderson would find his way on base to unintentionally pass the buck, the baton and the responsibility for Wednesday’s result to Reyes. I had no sense of whether this would be good for him or us. On instinct, I stood and I paced in small circles as I don’t think I’ve done before this season. It hadn’t previously seemed worth the trouble.

On a two-oh pitch, Jose lined a ball past Bush. Could he have actually driven in the go-ahead run? The liner up the middle wasn’t struck terribly hard and the Ranger defense was positioned to corral it. From the outfield grass to the right of second base, Rougned Odor picked it off the ground on one hop. It was a just difficult enough play to make so that Odor wound up bouncing his throw to Andrus, covering second. Andrus went about gathering it in ahead of Granderson’s slide. With Elvis’s back to us and his glove obscured by his body, it looked like Curtis was going to be out to end the threat and the inning.

Looks were deceiving. Texas’s shortstop had a hotter potato on his hands than we at home could discern. Slowly but assuredly, second base umpire Chris Guccione determined Andrus never fully controlled the ball before dropping it altogether. As Guccione went about declaring something had gone horribly awry for a Mets opponent for a change, Reynolds — too callow to know any better — kept running until he crossed home plate. Replay review was deployed, but to no avail for the Rangers. The Mets led, 4-3, on a modestly vexing fielder’s choice facilitated by a .187 hitter who came through barely by not coming up empty.

Buoyed by the unlikely circumstance of some other team imploding to the Mets’ advantage, Addison Reed retired the Rangers in order in the bottom of the ninth. Reed recorded his ninth save, Blevins — whose gopher to Chirinos rendered Wheeler’s effort non-decisive — his third win. It was every bit the W that Clayton Kershaw was awarded earlier Wednesday for going seven and fanning nine in vanquishing Washington. Kershaw pitched lengthily and brilliantly. Blevins had a bad blip that negated Wheeler’s efforts within the box score. Yet Kershaw and Blevins were both victors in the ancient statistical sense. Assignation of pitcher wins can be as ridiculous as the designation of a player to do no more than hit and sit, but when it all works out for what we consider the best, we’ll quietly ride our high horse out of Texas with a split in our saddle bag and try not to raise too much of a ruckus regarding what we find objectionable in the details.

Between you and me, though, pitcher wins are rather inane and the DH remains an absolute travesty.

For one ultimately pleasant evening, the Mets paused their ongoing re-enactment of 1974, the year this year is most reminding me of (also, the last year I paid rapt attention to the Texas Rangers). Nineteen Seventy-Four represented the comedown from the adrenaline rush of 1973. The only significant change those Mets made after their near-impossible surge into the postseason was cutting ties with an iconic quadragenarian. The post-Willie Mays Mets were stuck in the kind of mud these Mets, post-Bartolo Colon, have been. After 57 games in 1974, the Mets were 23-34. After 57 games in 2017, the Mets are 25-32. Wayne Garrett, a .422 hitter down the ’73 stretch, was batting .176, eleven points lower than Reyes. Tom Seaver’s ERA was 3.61, which for 1974 — and Seaver — was as unsightly as 4.75 is for deGrom. Hell, Tom, following his second Cy Young season, had only three wins…or as many as Blevins does at present.

One September’s inspiring heroes were the next June’s mere mortals. The pitching didn’t nearly match its reputation. Roster replenishment was mostly eschewed. Sound familiar? For what it’s worth, those Mets had no You Gotta Believe encore in them. They were in fifth place and eight games out of first at this juncture 43 years ago en route to finishing in fifth, seventeen behind the division-winning Pirates. The only NL East team the Mets led after 57 games in 1974, however, was that very same Pittsburgh crew, which wallowed nine games from first. Like the Mets the season before, they didn’t lay down and die just because they were pretty much dead. Not every cause apparently lost in June stays irretrievably lost until October. If you choose to Believe as we did in 1973 and 2016, you may wish to take note that the 2017 Mets are, as of today, nine games out of a Wild Card spot.

Nah, I’m not buying it, either, but you never know.

You are cordially invited to Bergino Baseball Clubhouse on Thursday, June 15, 7 PM, where I will be discussing my book Piazza: Catcher, Slugger, Icon, Star and other matters related to New York Mets history. Details are here. I hope to see you there.

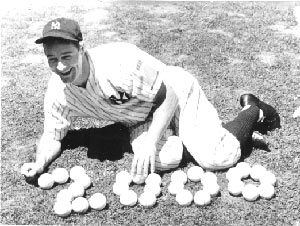

by Jason Fry on 7 June 2017 12:56 pm Hmm, is that how you spell Milestone Achieved? It looks a little funny, but there’s no wavy red line under it, so I guess it must be correct.

As you may have heard, Tuesday’s night game — played in whatever suburb of Dallas that’s considered to be in whatever that park that looks perfectly new but is soon to be replaced is called — was the 2,000th in a row we’ve chronicled here at Faith and Fear since the winter day we decided to celebrate the inauguration of the Carlos Beltran era by exchanging our thoughts about the Mets in a public forum instead of in extremely long emails.

Whether or not you’re talking baseball, milestones are rarely particularly interesting in themselves — the significance is in what’s come before, not what’s occurred in the moment. There are exceptions — Derek Jeter comes immediately and apologetically to mind — but most 3,000th hits are singles necessitating a pause in run-of-the-mill games, most 300th wins are corralled by bullpens while everyone waits impatiently, and lots of playoff spots are secured on the road before a few temporarily nomadic loyalists amid indifferent home crowds.

So no, we didn’t get a second no-hitter, four home runs from an unlikely source, or anything like that. We didn’t even get Gary Cohen — though vacation play-by-play guy Scott Braun’s only sin was being unfamiliar, which is more about us than his work alongside Ron Darling.

What we did get was an all-too-typical 2017 Mets loss: more hitting than you might expect, bafflingly horrific starting pitching, inadequate defense and an extra twist of the knife in case you’d forgotten what an utter drag this season has been.

Jacob deGrom was terrible again, offered a consoling arm after his removal by Terry Collins and later insisting to reporters that he feels fine and doesn’t know what’s wrong other than location and pitches doing nothing, which is more than enough to ensure a bad day. The defense behind him was execrable in ways big and small, with Met fielders just missing converting some difficult plays and quietly botching some not-so-difficult ones. The bats put up big numbers in the box score, but left a bushel of runners in scoring position. Of course there was a ferocious ninth-inning attempt at a comeback that got you a bit excited despite knowing better. And of course that comeback fizzled, with a game-ending double play coming as a petty, mean-spirited coup de grace.

What’s to be done with this team as we ponder recaps 2,001 and up?

Sports Illustrated’s Jay Jaffe recently looked at the Mets as one of the teams that has to decide whether or not to sell, and noted that a Mets sale could net a pretty good return: Jay Bruce, Lucas Duda, Neil Walker and Addison Reed are all pending free agents who would be among the best options at their positions for playoff-hunting clubs, while Asdrubal Cabrera is signed through next year and could be moveable. Hell, someone might be even persuaded to take a flier on a couple of months of Curtis Granderson and/or Jose Reyes.

Surveying that list, my reaction is: Goodness, trade as many of them as you can. Bruce, Duda, Walker and Reed might net a couple of actual prospects, or at least some interesting lottery tickets. Both Amed Rosario and Dom Smith look ready to try their hand at the big leagues, and are a week or so away from escaping Super 2 status. Rosario would immediately help the Mets’ infield defense, taking some of the pressure off the pitchers. Once Yoenis Cespedes returns — as stubborn hope insists he will — the Mets will be back to trying to solve a corner-outfield logjam.

Most significantly, a summer sale wouldn’t be a long-term rebuild but a short-term reload. Even without factoring in returns on trades or potential winter acquisitions, Rosario and Smith would join a lineup that would still feature Cespedes, Michael Conforto and Wilmer Flores (who’s somehow still only 25). They’d get more time to find their big-league footing without being treated as saviors. And you’d be returning all the starting pitchers, with fingers crossed for better health and luck.

I’d be intrigued by that team for the rest of 2017. I’d be eager to see what they could accomplish in 2018. Maybe they could even help the Mets attain milestones instead of millstones.

by Greg Prince on 6 June 2017 3:11 pm The Mets winning 11 games in a row.

Dwight Gooden winning 14 games in a row in one season.

Tom Seaver winning 16 games in a row over two seasons.

Tom Seaver striking out 200+ batters a year 9 years in a row.

Tom Seaver striking out 10 batters in a row to finish a game.

Jacob deGrom striking out 8 batters in a row to begin a game.

R.A. Dickey pitching one-hitters 2 starts in a row.

Turk Wendell pitching in 9 games in a row.

Moises Alou hitting in 30 games in a row.

Mike Vail hitting in 23 games in a row as a rookie.

John Olerud reaching base 15 times in a row.

Richard Hidalgo homering in 5 games in a row.

Mike Piazza recording an RBI in 15 games in a row.

Jose Vizcaino recording a hit in 9 at-bats in a row.

Rusty Staub recording a pinch-hit in 8 pinch-hit at-bats in a row.

Jeurys Familia converting 52 saves opportunities in a row.

Jose Reyes playing in 200 games in a row.

And, barring uncooperative weather, electrical shenanigans or some other stripe of catastrophe in the hours ahead, Faith and Fear recapping 2,000 regular-season Mets games in a row.

He was referred to as the Iron Horse, yet how many games in a row did Lou Gehrig blog? You read that right, if you read it all. We are on the cusp of FAFIF 2,000 (or F2K). There’s Cal Ripken, there’s Lou Gehrig, and then there’s us, if you’re not too picky about what actually happened in our respective consecutive games played/blogged streaks.

Some Mets streaks are more famous than others. Anthony Young’s streak of 27 losses in a row may be the most famous of them all, but it wasn’t delightful. Jose-Jose’s all-time Mets best games-played streak from 2005-2006 isn’t famous at all (even I had to look it up), but it does get at the consistency inherent in our heretofore unknown streak. How obscure is FAFIF’s run at 2,000? You’ve just now heard of it. Jason only heard of it last week when I told him about it, and he’s one of the two bloggers responsible for it. Nevertheless, this streak is real and it is spectacular. Or maybe it’s just real. I don’t know. We started a blog before the beginning of the 2005 season, we recapped the first game (a loss), we recapped the next game (a loss) and we kept going until suddenly we were up to 1,999 on Sunday (a loss).

Contrary to the impression I’ve crafted directly above, they haven’t all been losses. The Mets’ record since we’ve taken it upon ourselves to have something to say out loud about every game they’ve played is 1,011 wins and 988 losses. That, like Jeurys’s streak, takes into account the regular season only. For the record, we’ve recapped 25 postseason games in a row. We’d be happy to recap more of those.

We don’t know when more of those will be available. We do know a game between the Mets and Rangers is scheduled tonight and, should it be played to a decision, we plan to tell you our thoughts about it sometime between its final out and the first pitch of the game after it, which projects as the 2,001st in our streak.

Not to get ahead of ourselves. As has been the case since April 4, 2005, we blog ’em one game at a time.

by Greg Prince on 5 June 2017 4:05 pm With your first selection of what to do on Thursday night, June 15, at 7 o’clock, I hope you’ll choose to make a visit to Bergino Baseball Clubhouse, 67 E. 11th St. in Manhattan. I’ll be there talking about my book Piazza: Catcher, Slugger, Icon, Star with gracious owner and podcast host Jay Goldberg, going deep on the catcher who went deep more than any other, especially how the Mets came to be the unlikely landing spot for the unlikely superstar. Copies will be available, and if you’d like me to sign yours, I’d be delighted to bring out the ink.

The 62nd-round pick nobody saw coming to the majors, let alone landing in New York. Though it’s Piazza’s name atop the marquee, the Mets of the 1990s — particularly before they ever got together with Mike — are as intrinsic to the story as the title character. One of my goals in writing this book was to trace was how a franchise and its eventual face could have no common ground in the middle of a decade yet become eternally enmeshed and synonymous with one another before that decade was done. Thus, I spent a good deal of the early chapters exploring who the Mets were when Piazza was revving up his bat in L.A. and how they tried to morph into something better before he arrived in New York — and how tough that was for them to accomplish.

Maybe it would have been had they drafted better.

A tentpole of the Piazza legend is where he stood in the amateur draft. Essentially, he had no status. You probably know the numbers most associated with 31’s humble professional beginnings: drafted in the 62nd round with the 1,390th overall pick by the Dodgers in 1988 because Tommy Lasorda was pals with Mike’s father, Vince Piazza. Mike’s power potential was recognizable, but he didn’t have a position, hadn’t done much as a college player and, well, he needed a break if he was gonna get picked by anybody. Enter the “courtesy pick,” as it was called. A favor for Lasorda who wanted to do a favor for the elder Piazza? Pals, schmals. The Dodgers were smart to give a kid who might hit an opportunity. Mike took it from there.

Where in that era, I wondered, was the Mets’ draft choice who nobody saw coming but broke through? Where, for that matter, was the Mets’ draft choice who was seen coming, made it big and kept the club’s streak of winning seasons going? Ah, there was the rub. The Mets weren’t drafting so hot in those days. Or most days.

I wrote a lot about the Mets’ draft history within the context of Piazza’s ascent, culminating in his veritable national debut at the 1993 All-Star Game, where Mike was one of the glittering attractions alongside Ken Griffey and Barry Bonds. The last-place Mets had nobody like any of them in terms of performance or personality or both. Their All-Star was Bobby Bonilla, having a decent season at the plate but at the bottom of the league in public relations. Alas, I wound up cutting almost all of it for space. Since another MLB draft is right around the corner — the Mets will pick 20th on Monday night, June 12 (and higher, probably, in 2018) — I thought it would be timely to share this deleted scene from Piazza.

To paraphrase Troy McClure from “The Simpsons 138th Episode Spectacular,” if that’s what was cut, what was left in must be pure gold.

***

No wonder the Dodgers’ 1988 draft was the stuff of legend. But you know whose 1988 draft you didn’t hear much about in 1993? Or ever? The New York Mets.

The amateur draft behaved more like a stiff wind that blew in the face of their efforts to move forward, particularly where top draft picks were concerned. The Frank Cashen Mets were constructed on a foundation of sturdy high school choices: Darryl Strawberry (first selection in the nation, 1980) and Dwight Gooden (first round, fifth overall, 1982). It was enough to make a fan forget how little the Mets derived from their upper-echelon picks in the alternating years. The Mets drafted high in the early ’80s because they were constantly finishing low. They didn’t always make the most of it. Witness the choices of Terry Blocker (with the fourth overall pick in 1981) and Eddie Williams (No. 4 in 1983).

The missed opportunities of Mets drafts past were beginning to echo down the halls of time. From 1965 — the year the June amateur draft was instituted — to 1976, the Mets selected three major league mainstays with their respective first-round picks: Jon Matlack (1967), Tim Foli (1968) and Lee Mazzilli (1973). Before, between and after these diamonds in the rough were harvested, it was all fool’s gold. Whether injuries or overestimation undermined the best efforts of their scouts and decisionmakers, the Mets derived virtually no big league help from the first round on nine separate occasions. It seems cruel to dredge up the classic example of highly regarded catching prospect Steve Chilcott being the apple of the Mets’ eye when they owned the first overall pick in the 1966 draft, leaving outfielder Reggie Jackson on the table for the Kansas City Athletics to pluck, but that choice was indeed made.

Reggie Jackson was at the All-Star Game in Baltimore. He’d be at Cooperstown later in July as a first-ballot Hall of Famer, going in as so many before him had, as a Yankee. There was thought that since he established himself as a superstar in Oakland, that he, like Rollie Fingers the year before, would be portrayed on his plaque with an Athletic A. Or he could have followed Catfish Hunter’s example. When the righty was voted in by the writers in 1987, he chose to not choose between his tenures with the A’s and Yankees and asked to be enshrined with a blank cap. But a front-office position in the Bronx materialized for Jackson and that other NY won out. Mr. October, as ever with an eye on the bottom line, declared upon his election, “Going into the Hall of Fame with players like Mantle, Ford, Gehrig, DiMaggio, Ruth, is good for Reggie Jackson, so I’ll go in as a Yankee.”

Take that, Rollie.

Chilcott, meanwhile, would have for eternal company several other Met first-rounders who never saw the majors. George Ambrow (1970), Richard Bengston (1972) and Tom Thurberg (1976) also never rose to the heights of their profession. Another, Cliff Speck, taken seventeenth overall by the Mets in 1974, bounced around the minors for more than a decade before finally making the majors as a Brave a dozen years later. Speck pitched in thirteen games for Atlanta in 1986, but was back at Triple-A in 1987, never to return to what we soon, thanks to Bull Durham, learned to call The Show.

Cliff Speck’s thirteen games in the majors didn’t amount to much, unless you’re Les Rohr (Mets first top pick, 1965), Randy Sterling (1969) and Rich Puig (1971), and together the three of you combined for thirteen major league games in toto. Throw in Speck’s résumé and you’re up to 26…or about half as many as the first Mets pick of 1975, Butch Benton, compiled for three teams in four non-consecutive seasons over an eight-year span. Nevertheless, one resists the temptation to say Speck fell of a cliff or that Cliff’s career amounted to little more than a speck on the MLB map, because who wouldn’t want to pitch in thirteen major league games? When Kevin Costner as Crash Davis explained to his celluloid teammates what The Show was like in 1988 — white balls for batting practice, cathedrals for ballparks, room service back at the hotel — we in the audience could all picture ourselves enduring the 377 minor league games Cliff Speck pitched in the minors to experience the thirteen greatest games of his life.

For mere mortals, the 377 minor league appearances Speck made between ’74 and ’88 sound pretty good. As Crash’s manager in Durham told him, going to the ballpark and getting paid to do it beats the hell out of working at Sears.

***

Drafting amateur baseball players is an inexact science for all. College baseball doesn’t yield the same sense of certainty the higher-profile college sports do, and when you’re talking about high school athletes, you’re attempting to project not just what a baseball player might achieve but discern what kind of an adult an adolescent might turn into. Scouting reports that don’t include a bevy of question marks simply aren’t being honest.

Still, you’d figure you’d get a few right now and then, if just by accident. The Met eye for amateur talent turned keen between 1977 and 1979, with Wally Backman, Hubie Brooks and Tim Leary each a top pick destined for a solid career (though Leary had to endure a debilitating injury as a Met before succeeding as a Dodger). Beyond Strawberry and Gooden, the Mets either lucked or skilled their way into some fine picks once Cashen took over baseball operations.

Blocker, the head of the class of ’81 might have fizzled, but underclassman Lenny Dykstra, chosen in the thirteenth round, went on to flourish, as did the Mets’ twelfth-round pick, a high school pitcher from Texas named Roger Clemens…though Clemens rejected the Mets’ offer and headed for college for the time being. Nineteen Eighty-Three yielded the underwhelming Williams, but also righty starter Rick Aguilera, eagle-eyed batsman Dave Magadan and submarine-flinging reliever Jeff Innis. Behind Gooden in 1982, they took bullpen stalwart Roger McDowell in the third round; in the old secondary phase of that June’s draft, they scooped up closer-to-be Randy Myers in the second round. In the soon-to-be-discontinued January amateur draft of 1984, they took shortstop Kevin Elster with their second selection. Names not associated with great feats in Met uniforms — John Christensen, Floyd Youmans, Calvin Schiraldi — were drafted as well in this era, proving their true value once they were inserted into trades that brought to New York players — Bobby Ojeda, Gary Carter — who are indelibly associated with great feats in Met uniforms.

On a lesser scale, the Mets’ and nation’s first pick of 1984, Shawn Abner, proved himself valuable as trade fodder in the wake of the 1986 World Series when the Mets used him to help nab San Diego’s sound-as-a-pound left fielder Kevin McReynolds. And in June 1985, with the twentieth overall pick in the nation, fifteen spots after the Pirates took Barry Bonds, the Mets went for Gregg Jefferies, who emerged as Baseball America’s Minor League Player of the Year twice and played in the same 1993 All-Star Game as Piazza.

By then, Gregg was a member of the Cardinals, having worn out his hotly anticipated welcome in New York, but that’s another story. Or maybe it isn’t. Jefferies couldn’t have shown more talent rising up the Met chain. His first few weeks as a regular, coinciding with the stretch drive of 1988, were so electrifying you could picture him doing public service spots for Con Edison. Heaven, earth and Backman were moved to make the 21-year-old rookie the everyday second baseman for 1989 and, presumably, the decade ahead.

From there, Jefferies didn’t exactly flop, but it couldn’t be said that he flourished. Mostly he rubbed his teammates the wrong way. Jefferies was a prodigy with a bat, a liability with a glove and maybe not mature enough to handle his workplace environment. It is less recalled that he garnered Rookie of the Year votes in both 1988 and 1989 and that he led the league in doubles in 1990 than it is that he was the subject of veteran enmity (Myers scrawled “Are We Trying?” across a lineup card in a not-so-veiled shot at the struggling tyro), made allies of enemies (McDowell fought him as a Phillie and the Mets weren’t exactly rooting against their old teammate) and faxed a cease-and-desist letter of sorts to WFAN that constituted a public plea to be left alone.

That he had talent was borne out once he fell into the nurturing hands of St. Louis manager Joe Torre. That his ability to cope wouldn’t outstrip his ability to lash line drives in Flushing was not immediately evident when the Mets drafted and signed him out of Serra High School in San Mateo, California. But because these things are inexact, and because someone of Jefferies’s ilk did not stick around to anchor the Met offense in post-Strawberry New York…and because Jefferies was an absolute success story relative to the top Met draft picks that followed him, you can see — certainly with hindsight — that a subterranean down year like 1993 was bound to materialize and wash away whatever good vibes remained from up year nonpareil 1986.

In the draft conducted during the June the Mets were running and hiding from the National League East like they had never run and hid before, the Mets used their first pick on the son of a major leaguer. Lee May, Jr., like Ken Griffey, Jr., was the progeny of a component of the Big Red Machine, albeit a slightly earlier version that hadn’t yet worked all its bugs out. The elder May was a serious slugger, knocking 111 home runs out of NL ballparks between 1969 and 1971. He was at the center of the package that was sent to Houston to obtain Joe Morgan. Morgan added a new dimension to Cincinnati, revving the Reds — once they tightened their bolts with the likes of Griffey, Sr. — toward their two world championships. When Junior was taken first overall by the Mariners in 1987, you took his championship bloodlines seriously.

When the Mets picked May out of a Cincinnati high school…well, to be honest, in 1986, the draft didn’t grab your attention the way it would in years to come, but you recognized a name like Lee May. You figured the son of a man who produced 354 home runs, made three All-Star Games and earned MVP votes on six occasions was at least going to show up at Shea one of these days.

He didn’t. Lee May, Jr., topped out at Tidewater, failing to reach double-digits in home runs in an eight-year career, never batting higher than .257 at any of his minor league stops. May would later find a place in the game as a hitting instructor (his son, Jacob, was drafted by the White Sox in 2013), but he was not around to help Jefferies and the Mets as 1986 commenced receding in the immediate collective consciousness.

Nor was Chris Donnels very much. In the same first round that bestowed Griffey on the Mariners, the Mets took Donnels. Being defending world champs, they drafted 23 picks later. To say Donnels didn’t belong in the same round as Griffey isn’t exactly a slam at Donnels. Griffey proved a draft unto himself.

But could have the Mets done better for themselves than the third baseman from Loyola Marymount University? They did, in later rounds of the 1987 draft, taking yet another MLB legacy, slowly developing catcher Todd Hundley, in the second round and intermittently promising lefty pitcher Pete Schourek in the third. With their 38th-round pick, the Mets tabbed Anthony Young, who may not have succeeded a great deal more than Donnels — 82 games as a Met in ’91 and ’92 before drifting to the Florida Marlins in the expansion draft — but he was still on hand in ’93 and he certainly became more famous.

Or infamous.

***

The reinforcements simply weren’t bubbling up from beneath the surface. If the Mets were trying to patch together the remnants of their would-be dynasty with expensive dollops of Krazy Glue, it was because there wasn’t bonding element otherwise available to them. Once the Mets reached the mountaintop with so many homegrown stars and studs, they got very little out of the drafts that followed. 1988, the Year of Piazza, was par for the uninspiring course.

They got no Strawberry. They got no Gooden. In terms of who they selected and signed from that draft, they got exactly two players who would reach the major leagues with them: shortstop Kevin Baez (batted .179 in 63 games between 1990 and 1993) and second baseman Doug Saunders (28 games in 1993, encompassing 73 plate appearances without a single run batted in, the franchise record for offensive unproductivity among non-pitchers).

But both did make The Show, knowing the delights Crash Davis went wistful over for moviegoers. So did Joe Vitko, drafted by the Mets in the 38th round of 1988. The righty pitcher declined to sign, continued at college and remained attractive enough to the Mets for them to pick him in the twenty-fourth round of 1989. This time he said yes. Three years later, he was in the majors, carving out his own Saunders-like niche in the Met annals as the first Met player to be born in the 1970s, unwittingly heralding a lost generation of prospects. Joe pitched in three games in September 1992, then never again in the majors.

Dave Proctor had the “never” part down cold. Dave was the Mets’ first-round pick in 1988, sixty-one rounds and 1,369 slots ahead of Piazza. The righthanded pitcher from Allen County Community College in Kansas was as good a bet as any to pay off in the world of the amateur draft. The Dodgers themselves thought so two years earlier when they picked him as a high school senior in the twenty-ninth round. Like Clemens in 1981 (and many throughout the history of the amateur draft), he decided to go to school and see if he could do better. Proctor’s stock had only risen since. Dave had a family tie of his own not just to baseball, but to the Mets. His uncle was Mike Torrez, the Opening Day starter for the Amazins in 1984, filling the George Lazenby role between Tom Seaver in ’83 and Gooden in ’85.

With Torrez serving as his nephew’s negotiator, the twenty-year-old looked forward to inking his pact and getting on with his career. “He’s always told me how good New York is to pitch in,” the draftee said, adding patiently of his new employer, “I think they’re looking to me for more in the future, not going in right away. They want to develop me, and the Mets have a tradition of good arms, and I’m hoping they can mold me into one.”

It didn’t happen. Proctor tried. The Mets tried. His arm didn’t cooperate. An injury halted his rise at Double-A Binghamton, where one final start in 1992 resulted in an ugly 23.62 ERA. It doesn’t mean his JC coach was off base when he declared in 1988, “Dave’s got the world by the horns. I think he’s ready to go out and have a bright future in major league baseball.” The Mets agreed. Fate refused to concur.

May. Donnels. Proctor. In a more predictable enterprise, these were the players who should have been surrounding the likes of Jefferies when the Mets faced off against Piazza and the Dodgers in 1993, presumably pre-empting the need to lure free agents to Flushing. Yet none of the above was a New York Met during what projected as the primes of their major league careers. Conversely, Piazza wasn’t supposed to be hitting home runs at Shea or any other National League ballpark, never mind tipping a cap among All-Stars at Camden Yards.

Did we mention how unpredictable baseball can be?

On first-round Russian roulette went, the Mets almost always finding the bullet in the chamber. Alan Zinter in 1989. Al Shirley in 1991. Jeromy Burnitz, their top pick in ’90, actually made the majors in June of 1993, injecting a little thump into the Met lineup and a little hope into the Met future, and Preston Wilson — Mookie’s stepson — was going to benefit from all the goodwill possible after getting the nod in ’92. But in 1993, when Mets fans could have used the biggest jolt of optimism possible, their team took Kirk Presley.

Presley as in Elvis. Kirk was the King’s third cousin, born in Tupelo, Mississippi, and everything. Talk about a family connection. It had nothing to do with baseball, but it was something to remember Kirk by, as his potential, too, succumbed to aches and pains. An otherworldly 37–1 right-hander with a 0.58 ERA and multiple no-hitters on his scholastic ledger, the youngster who never knew his outsize older relative didn’t get the chance to shape a professional identity of his own, beyond that of yet another failed top Mets draft pick. “It is frustrating when that’s the first question they ask,” the 18-year-old admitted of Elvis the summer he was drafted, “but I guess that’s part of it.”

It could have been worse. Right around the time Presley was getting fed up with every reporter’s obvious angle, the Mets were being hounded and dogged (sorry, Kirk) by questions they were tiring of answering. When you’re a last-place team plumbing new depths of notoriety, it’s hard to hew to Crash Davis’s timeless interview advice and stick with “we gotta play it one day at a time” as your all-purpose thoughtful response.

To paraphrase the other Elvis — Costello — every day the 1993 Mets rewrote the book. Bonilla may never have taken Bob Klapisch on that tour of the Bronx, but in a way, Bobby got his revenge on Bob, for The Worst Team Money Could Buy was already and instantly out of date.

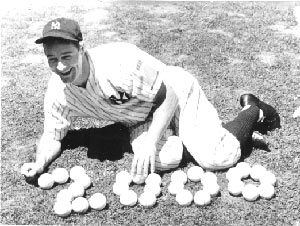

by Greg Prince on 5 June 2017 12:38 am Jimmy Piersall and the Mets might not have been the best fit when they came together for 40 games in 1963, but no .194 hitter ever left behind a more camera-ready legacy. The story’s been told as much as any from the second season of New York Mets baseball. Piersall, who had his talents and his troubles, landed on the worst team in captivity, sent from Washington, D.C., to Washington Heights as compensation for the managerial services of beloved just-retired first baseman Gil Hodges. The career American Leaguer, two-time All-Star outfielder, and subject of a major motion picture starring Anthony Perkins — following Piersall’s nervous breakdown and the book he wrote documenting it — was miscast as a member of Casey Stengel’s tenth-place ensemble, but he definitely had one intensely memorable Met swing in him.

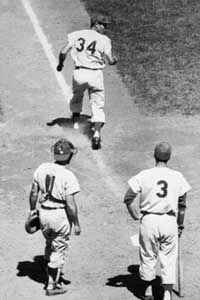

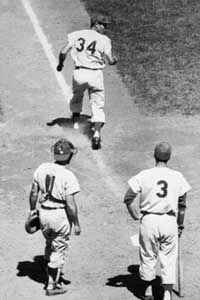

Sitting on 99 lifetime home runs for almost a month after joining the Mets on May 24, Piersall decided that when he finally moved into triple-digits, he was going to do something special to celebrate. Finally, on June 23, in the first game of a Sunday Polo Grounds doubleheader versus the Phillies, the Mets’ starting center fielder swung and connected for No. 100 off a mild-mannered (cough-cough) righty named Dallas Green.

Jimmy Piersall eschewed Satchel Paige’s advice and looked back. He kind of had to. Then, once he knew it was gone, he ran the bases in a backwards motion, reversing his gait all the way from first to home. This trip was different from what anybody had ever seen in a baseball game, and it has yet to be forgotten. When it was reported on this Sunday in June, 54 years later, that Piersall had died at 87, it was hard not to conjure the signature image of No. 34 approaching the plate, the runner glancing over his right shoulder to make certain he wasn’t straying from the baseline. Two other players are visible in the foreground of the photograph that survives, neither of them forming a welcoming committee. On-deck hitter Tim Harkness’s body language indicates impatience (and admirable restraint in not wielding his bat ASAP). Phillies catcher Clay Dalrymple is likely monitoring the actions of his batterymate, for Green did not appreciate Piersall’s brand of flair. Dallas wrote decades later in his memoir, “I was pissed off by his antics. I stalked him as he rounded the bases, swearing up a storm.”

The backpedaling bit didn’t go over huge among Metsian observers, either. In the Daily News, Dick Young labeled Piersall “a pure-beef hot dog,” and compared him to the tap dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. Nonpareil character Stengel — who had long ago revealed a sparrow under his cap while playing big league baseball — legendarily declared there was room for only one clown on his team, and it wasn’t gonna be the guy whose NL average was trending inexorably downward. By mid-July, the former Red Sock, Indian and Senator, added Met to his ex-files. Jimmy caught on with the Los Angeles Angels (then actually of Los Angeles) and played for them until 1967, homering only four more times, rounding the bases in orthodox fashion on each occasion.

How mundane. Duke Snider, who had recently launched a milestone home run of his own for the very same 1963 Mets, said to the man of the counterclockwise hour, “I hit my 400th homer and all I got was the ball. You hit your 100th and go coast-to-coast.” Indeed, Piersall received national attention, a one-way ticket to Southern California and enduring…notoriety is often misused, but it seems to be the go-to word here. On a team where loads of losing was gamely tolerated, the guy who hit a home run to key an eventual 5-0 win was grimly frowned upon in real time and in most retellings.

Nevertheless, we remember it to this day and appreciate it as an element of what made the early Mets the early Mets. Nobody got killed. Nobody got hurt. Piersall’s feel for what was good fun may have gone afoul of his sport’s code of honor, yet, generally speaking, he didn’t exempt himself from his singular sense of the absurd. Or as he was known to say, “I’m crazy, and I got the papers to show it.”

At least Piersall meant to go backwards — and at least his team won the day he did so. I doubt going backwards was part of the current Mets’ plan, yet there they keep going, in the wrong direction. They’ve dropped from the periphery of contention, they’ve drifted well south of .500 and even their routine inning-ending machinations can’t properly end innings.

Posterity will tell if the signature play of Sunday, June 4, 2017, will linger in the baseball subconscious as its predecessor from Sunday, June 23, 1963, has. My guess is probably not, yet once again, the Mets did something so decidedly different from the norm that onlookers were left to wonder if anybody else had ever seen anything like it.

• First, with one out and Josh Harrison on first, they turned a 5-4-3 double play to complete the top of the seventh at Citi Field.

• Then they left the field for the weekly extended-mix version of the seventh-inning stretch, the one that commences with “God Bless America,” continues with “Take Me Out To The Ball Game” and concludes with “Lazy Mary”.

• Then they prepared for the bottom of the seventh, only to be informed, no, your double play didn’t count, it’s still the top of the seventh, get your pitcher back on the mound.

Yeah, that sort of sequence doesn’t unfold very often.

Give or take a silly millimeter, this wasn’t the Mets’ fault, exactly. Well, theoretically, Neil Walker could have kept a foot more convincingly planted on second base while retrieving the relay of John Jaso’s grounder from third baseman Wilmer Flores. As was, Walker caught the ball and threw it for an uncontested out at first. Jaso was definitely retired on the play. Harrison, meanwhile, didn’t bother running all the way from first to second; he knows what a 5-4-3 double play looks like when he’s caught in the middle of one. If replay review didn’t exist, you wouldn’t have blinked at the out call on what we used to refer to as a neighborhood play, the neighborhood in this case appearing to be comprised of attached row houses. There was virtually no space between Neil’s shoe and second base. But just as replay review exists, so did the slightest sliver of daylight when it mattered. Pirate skipper Clint Hurdle thus issued a challenge to confirm that Walker’s foot was not on second base at the precise moment he took Flores’s throw, and the umpires were obliged to cooperate. Confirmation was forthcoming. Harrison was ruled safe.

In any other inning, or even on another day of the week in the same inning, such inanity would have proceeded relatively smoothly and generated no more than annoyance for transpiring at all. But Sunday being Sunday, and “God Bless America” being sacred (for if it is not sung at a ballpark, America might not get blessed), the umps felt compelled to respectfully wait to go through the motions of making it clear to everybody who might care that video officials in Chelsea were being consulted. As a result, Terry Collins, his team, the fans on hand and the folks at home were quite surprised to learn that, once the seventh-inning stretch rituals were over, the top of the seventh was to be rejoined, already in progress, with two out and pinch-runner Max Moroff on second.

Naturally, it all conspired to undermine whatever was left of the Mets’ chances. Josh Edgin, who had thrown the nullified double play ball, immediately surrendered a run-scoring single to David Freese, which increased the Pirates’ lead from substantial to prohibitive. Then Edgin got the third out. Then there was another seventh-inning stretch, albeit sans “God Bless America”. Whether it’s the crew in Chelsea or the Lord in heaven, you can bother ultimate arbiters with your sincerest beseechments only so many times in one day.

Eventually, the lopsided visitor-friendly score built to an 11-1 final that is rather misleading, for the contest was never that close. The defense was bad, the offense was worse and Tyler Pill was no remedy for what ailed us. The only legitimate home-team highlight occurred when Collins couldn’t resist demanding his own challenge in the top of the eighth. Since the play nominally in question wasn’t remotely disputable, I assume Terry insisted the umps ask the replay officials to examine his life choices and see if the decisions that led him to manage such a lousy club on such a lousy day could possibly be reversed.

There wasn’t enough to overturn.

by Jason Fry on 4 June 2017 11:40 am Lots of seasons don’t go quite the way you fantasize — your team’s undone by some combination of poor performances, bad decisions, ill health, lousy luck, or just by not being as good as the competition. By late spring you figure your October will be free; by summer you’re thinking about next season. Which is all OK — it’s just baseball, after all. For us, a bad harvest doesn’t mean famine or foreclosure, just needing to diversify our sources of entertainment.

So far, the 2017 Mets haven’t lost a spectacular number of games — once things normalize a bit, they’re probably some variation of a .500 team, which is only heart-rending compared with preseason rankings. What feels different this year is the way the Mets have lost those games. I know it’s the confirmation bias talking, but the 2017 Mets seem allergic to run-of-the-mill losses. Every single one seems to be a tragedy or a farce, leaving you with a ragged hole in the chest where your battered orange and blue heart used to beat. Lose 6-3 on a sleepy afternoon? No sir, not this squad. They’re going to load the bases with nobody out and still fail, or find a new reliever to melt down hideously, or gag on a game-ending double play.

Which made Saturday all the more extraordinary: with all the pieces arranged for disaster, the Mets walked away from the puzzle. The dog didn’t bark. No murderer came to the door. They actually won.

Perhaps it helped that they were playing the Pirates, a team having a similar season of perplexing disappointment. (Though in a far kinder division in terms of second chances.) Or that Neil Walker was playing the Pirates, whom he treats like a scorned ex hell-bent on showing you how wrong you were.

Robert Gsellman didn’t go deep enough to make us stop sighing about the shell-shocked bullpen, but he did pitch well enough to make us scrutinize the starting pitching and ask Whither Gsellman? without being ironic. (Seriously: Whither Gsellman?) Fernando Salas entered with a skinny lead and exited with that skinny lead intact. Jerry Blevins came in and did his usual masterful work (his strikeout of Josh Bell was pure and simple cruelty), even with his teammates providing their usual bout of sabotage.

And then Terry brought in Addison Reed an inning early.

At first I thought Terry had gone modern, reasoning the closer’s job was to dispatch the toughest hitters in the order when they arrived instead of automatically handling the final inning. But Terry doesn’t do modern, and I’d forgotten Andrew McCutchen‘s slide down in the Pirates’ order. No, Reed was going to get six outs or die trying.

Which Reed did, somehow. John Jaso didn’t ruin everything, as he has before. Nor did Gregory Polanco, David Freese or Bell. Reed walked off the mound with 36 pitches thrown and a victory secured, and the Mets had won a 4-2 game. If that sounds relatively ho-hum, well, 2017 will remind you otherwise soon enough.

by Greg Prince on 3 June 2017 3:09 am Lucas Duda’s second home run had just left the building and perhaps the solar system. The Mets’ seventh run of the evening was crossing the plate, their lead over the Pirates was reaching three and it was only the fifth inning. My good friend Jeff, once he was done jumping up and down like the kid a long Lucas Duda home run will turn an adult Mets fan into, draped his right arm around my shoulders and grabbed me as good friends will when they want to share with you something they’ve decided you need to hear.

“Guys like us,” Jeff declared amid the cheers — “this is what we dream of. Other guys may dream of sleeping with supermodels. Not us.” He made a sweeping motion with his left hand to encompass the pulsating scoreboard, the forlorn visitors hanging their heads all over the field, the giddy occupants of the first base dugout and our neighbors whooping it up around us in Promenade. “This is our dream.”

That was in the bottom of the fifth. We woke up in the top of the sixth. No dream. No supermodels. Just Pirates running round and round.

The Mets had led the Pirates, 7-4, when the fifth ended. Before they batted again, they trailed, 11-7. Prospective winning pitcher Matt Harvey gave way to presumptive savior Paul Sewald. Between them, they gave up as many runs as they possibly could. Neil Ramirez came on to…well, Neil Ramirez came on. Tells you pretty much what you need to know.