The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 6 September 2011 11:30 am Welcome to The Happiest Recap, a solid gold slate of New York Mets games culled from every schedule the Mets have ever played en route to this, their fiftieth year in baseball. We’ve created a dream season that includes the “best” 133rd game in any Mets season, the “best” 134th game in any Mets season, the “best” 135th game in any Mets season…and we keep going from there until we have a completed schedule worthy of Bob Murphy coming back with the Happy Recap after this word from our sponsor on the WFAN Mets Radio Network.

GAME 133: September 6, 1985 — Mets 2 DODGERS 0 (13)

(Mets All-Time Game 133 Record: 24-24; Mets 1985 Record: 81-52)

September + Pennant Race + 1985 could only add up to one conclusion for the New York Mets: Dwight Gooden. The 20-year-old 20-game winner had dominated the National League for the better part of five months. He would now attempt to own his spectacular season’s sixth, under the most pressing of circumstances.

The Mets entered this weekend series against the N.L. West-leading Dodgers a game-and-a-half back in their own Senior Circuit sector, and Doc offered the best chance to pick up or at least maintain ground. But Gooden was going up against a pretty formidable opponent, too: Fernando Valenzuela. The two had hooked up twice previously in 1985, each pitcher taking a decision. The Mets had seen Valenzuela in New York less than two weeks earlier and found little success against him, losing 6-1 as Fernando tossed a complete game.

Friday night at Dodger Stadium…the 20-4 righty with a 1.81 ERA going for the visitors…the 16-9, 2.37 southpaw toeing Chavez Ravine’s high rubber for the home team. On paper, it couldn’t get much better than Gooden vs. Valenzuela.

On the field, however, it could exceed the paper.

It was stupendous. It was ace vs. ace doing exactly what you paid for if you were fortunate enough to be among the 51,868 in attendance. Staying up late back in New York was rarely as rewarding.

Valenzuela drew from the Mets three efficient groundouts to start the game in the first. Gooden answered back with a pair of strikeouts and a flyout. And they were off.

Neither fully suffocated the opposition, but for 7½ innings, no baserunner on either side reached third The Mets — with a righty-leaning lineup that featured Tom Paciorek in right bumping Darryl Strawberry to center, and Gary Carter at first in place of Keith Hernandez, who was still in transit after testifying at the baseball drug trial in Pittsburgh when the game began — twice got two baserunners on with one out, in the second and the fourth. But on each occasion, Valenzuela got the ground ball double play he needed. Doc brushed off the occasional pesky Dodger and racked up nine strikeouts through seven frames.

The first serious threat against Gooden came in the bottom of the eighth. Mike Scioscia and Greg Brock opened the inning with singles. A ground ball to Gooden cut down the lead runner and another to Rafael Santana forced a man at second. Still, that left L.A. with runners on first and third, with Mariano Duncan representing the go-ahead run in nothing-nothing game. The uprising was quelled when Paciorek made a terrific diving catch on Duncan’s fly to right.

“How he caught the ball,” Lasorda grumbled, “I’ll never know.”

The Mets didn’t touch Valenzuela in top of the ninth. The Dodgers sniffed an opportunity in the bottom of the inning when Ray Knight’s error put Mike Marshall on, but Gooden responded by striking out MVP candidate Pedro Guerrero, Gooden’s tenth K of the night. Marshall had taken off on the pitch, but was gunned down by Carter caddy Ronn Reynolds at second.

0-0 heading to extras. Valenzuela kept pitching. Davey Johnson went to his bench. Mookie Wilson pinch-hit for Reynolds, but flied out. Two batters later, the late-arriving Hernandez pinch-hit for Gooden with Santana on first, but Fernando teased a 6-3 DP grounder from Mex.

Still 0-0. The tie was entrusted to Roger McDowell in the bottom of the tenth. He let Bill Madlock single and advance to second on a sacrifice but threw his own double play ball to get out of it. Valenzuela remained in for the eleventh and retired Wally Backman, Paciorek in Strawberry all on grounders. Finally, in the bottom of the eleventh, Tommy Lasorda pinch-hit for Fernando with Len Matuszek. It was to no avail, but Duncan followed by singling, stealing and moving to third on a grounder. McDowell, however, stranded him there.

Tom Niedenfuer was the Dodgers’ new pitcher in the twelfth. The Mets did nothing of substance against him. Terry Leach replaced McDowell in the bottom of the inning and surrendered two quick singles. He gave way to Jesse Orosco who left the runners on.

The thirteenth commenced, the teams still knotted at nothing. Santana led off with a single, but a Hernandez grounder forced him at second. It seemed every Met rally was dying in the infield. But finally Backman hit a ball that reached the outfield. Keith ran for third, where the throw that couldn’t cut him down allowed Wally to follow him to second. It was the first time all night the Mets had brought a runner within ninety feet of scoring. Danny Heep pinch-hit for Paciorek, a lefty to face the righty Niedenfuer. Lasorda decided to pitch to Heep and it worked, as Danny fouled out to Scioscia.

With two out and first still open, the Dodger skipper was faced with two options, neither of them thrilling from an L.A. perspective. He could walk Strawberry to load the bases but have to face Carter — who had just homered five times in the Mets’ two previous games in San Diego — or he could take on the lefty Straw.

He told Niedenfuer to go after Darryl. If it was the lesser of two evils, it wasn’t by much. Straw didn’t homer, but he did deposit a ball over the left field fence on one bounce. Darryl’s opposite-field ground-rule double scored Hernandez and Backman and, at last, somebody was ahead: the Mets, 2-0.

Niedenfuer still had Carter on his dance card, but this time Lasorda insisted on an intentional walk. With two on and two out, and the game on the edge of being broken open, Knight singled…right into Strawberry. Darryl was hit by the batted ball, which meant a third out for the Mets. They’d have to settle for a 2-0 lead.

Now it was up to Orosco to nail down what had been a classic for 12½ innings. Hammering wasn’t quite Jesse’s thing, however. He walked Bill Russell to commence the bottom of the thirteenth. Strikeouts of Duncan and Candy Maldonado calmed Met nerves, but then Marshall singled and Guerrero walked. The bases were loaded for the first time all night by either team. And what a time to load them. Madlock, who owned four batting titles in his career and four hits on the night, was the next batter.

He was also the last batter. Orosco popped him to Hernandez at first. The Dodgers were left to rue eleven runners left on base as the Mets rode the exploits of Doc and Darryl to a 2-0 win that kept them apace with St. Louis.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On August 31, 1973, a Friday night in St. Louis, Ray Sadecki and the sixth-place Mets fell behind 3-0 in the first on consecutive Cardinal hits from Joe Torre (double), Ted Simmons (single) and old friend Tommie Agee (triple). Sadecki stiffened for the next five innings, giving up no more runs to the Redbirds, while the Mets chipped away on a Buddy Harrelson RBI single in the second and a Cleon Jones sacrifice fly in the third — though aggressive baserunning ran them out of each inning before they could get anything else. Ed Kranepool singled in the tying run off Mike Nagy in the sixth, with yet another Met (Rusty Staub) going out on a throw from the outfield.

After pinch-hitting for Sadecki in the top of the seventh, Yogi Berra turned to Tug McGraw, who had only recently began to turn his season around, however subtly. He won his first decision all year on August 22 and had lowered his ERA from 5.45 on August 20 to 5.18 entering this game five appearances later. McGraw had been a mystery through the summer of 1973, but now summer was ending, so maybe his mysterious miseries were wearing off as well.

Tug held the Cardinals scoreless in the seventh, eighth and ninth, long enough for the Mets to arrive in the tenth inning still tied at three. After Diego Segui struck out Harrelson and Segui to begin the festivities, the Mets sprung into action with five consecutive singles: Wayne Garrett, Felix Millan and Jones off Segui and Staub and Kranepool off ex-Met Rich Folkers. Three runs resulted and gave McGraw a 6-3 lead to take to the bottom of the tenth. He’d give up a run, but nothing more and the Mets would win 6-4.

A nice win, to be sure, but much nicer was that the Mets, unwilling basement tenants for so much of July and August, vacated last place in the N.L. East on the last night of August and would enter September in fifth place. That may not sound like a great position to start the traditional final month of the schedule, but it was not a traditional year in the division. Upon leapfrogging the Phillies, the Mets sat only 5½ games from first place at the dawn of September 1973.

And from there, who knew what might happen?

GAME 134: September 5, 1969 (1st) — METS 5 Phillies 1

(Mets All-Time Game 134 Record: 26-22; Mets 1969 Record: 78-56)

It was a milestone that, before 1967, seemed out of the Mets’ grasp for at least another generation. Come 1967, you knew it was only a matter of time.

Three years’ time, as it turned out.

From 1962 through 1966, the heart of an era when 20 wins was the price of admission for a pitcher seeking affirmation for having pitched a great season, the Mets had never had a hurler return from a year on the mound with more than 13 victories. Of course the Mets didn’t have any great teams then, so it’s no wonder something as modest as Al Jackson’s 13-17 record in 1963 — quite respectable for the 51-111 club on which it was earned — was as good as it got.

Then along came Tom.

Tom Seaver was a break with all that had gone on before in Metsdom, won-lost records included. On September 13, 1967, as Seaver’s sensational rookie campaign neared its end, the hard-throwing righty was handed a 2-1 lead in the top of the ninth at Atlanta when his catcher, Jerry Grote, singled in Ed Kranepool with the go-ahead run off Pat Jarvis. In the bottom of the inning, Seaver was all business. A flyout to right of Rico Carty, a grounder to short of Felix Millan and fly to left by Mike Lum, landing in Tommy Davis’s glove, finished off the Braves. With that, Tom Seaver set a new record, becoming the first Met pitcher to win 14 games in one season.

Before the year was out, Seaver would raise the mark to 16 wins, and he’d put up the same total one year later. His mark, however would be surpassed by another rookie, Jerry Koosman, whose Year of the Pitcher exploits in 1968 yielded him a spectacular 19 wins.

Now, in September 1969, the Mets were aiming higher than ever, including Seaver, who came into this first game of a Friday doubleheader at Shea against the Phillies with a 19-7 record, matching Koosman’s ’68 amount with a month to go. The team was in second place, five games behind the Cubs. That the Mets were bearing down on first-place Chicago was the most accurate barometer of how far the Mets had come in such a short time, but the fact that they possessed a starting pitcher on the precipice of a heretofore unthinkable Met milestone…just chalk it up as another Amazin’ element of a season whose most magical properties were yet to be revealed.

Seaver was never much for magic. He was skill and competitiveness, so why shouldn’t he be 19-7? Better yet, why shouldn’t he be about to be 20-7?

A second-inning leadoff single to Johnny Callison and an RBI triple to Deron Johnson would provide a momentary impediment to Tom’s provisional aspirations, but the Phillies didn’t score anything else and their 1-0 lead was short-lived. In the bottom of the second, two Grant Jackson walks (to Ron Swoboda and Rod Gaspar) sandwiched a Richie Allen error (on a Grote grounder) to load the bases for Al Weis. Weis singled off Jackson’s glove to put one on the board for the Mets, and Seaver’s subsequent infield groundout, thanks to Weis’s tough takeout slide at second, became two unearned runs as Gaspar hustled home behind Grote.

With a two-run advantage, Seaver’s businesslike instincts kicked in. He was perfect in four of the next six innings and allowed two unrelated hits in the two other frames. When Grote added a two-run homer off John Boozer in the bottom of the eighth, that matter of time was reduced to only three outs.

Allen grounded out. Callison struck out. Johnson was all that stood between a Met and a milestone. A one-two count set the stage. Ralph Kiner calls it:

“No pitcher for the Mets has won twenty ballgames in their history. Seaver’s one strike away. Here’s the one-two pitch…swung on and missed, strike three! So Tom Seaver becomes the first twenty-game winner in Mets history, the first twenty-game winner in the National League, and the Mets win it by a score of five to one.”

An economy of words for an economic effort. Though Mets fans had waited nearly eight years for such a moment, Seaver expended a mere one hour and fifty-two minutes capturing it. Five hits, one walk, seven strikeouts…yes, very much a vintage Tom Seaver effort, just as it was becoming universally understood exactly what that meant.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On September 4, 1976, what had been a blowout became a duel in earnest. It wasn’t supposed to be that way from a Mets perspective, not in July when it was a Met doing the blowing out, but fate had interceded, so you took what you could get.

Dave Kingman homered off Carl Morton of the Braves on July 18, giving Sky King 32 roundtrippers for the season after 92 Mets games. His most relevant National League slugging competition at the time came from Hack Wilson, the holder of the N.L. mark for most homers in a season. Hack hit 56 in 1930, and Kingman held a healthy lead over Wilson’s 29 in 92 46-year-old Cubs games as he headed for history.

Then Dave took a dive.

He tried to catch a fly ball off the bat of Phil Niekro the next night, and when the dust settled in left field, Kingman came up lame, tearing a ligament in his left thumb. Kingman was en route to the DL, Wilson was safe for posterity and the season’s lead Sky built was very much in danger, for while Kingman sat for more than a month, perennial National League home run champ Mike Schmidt charged. Schmitty, who topped Sky by a single dinger in 1975, had pulled even, 32 to 32, with Dave during the big man’s absence, so when the Mets and Phillies met at Shea this Saturday afternoon, power would speak to power.

Schmidt struck first, taking Nino Espinosa deep in the sixth, bringing the Phils within a run of the Mets at 4-3 and grabbing a 33-32 lead over Kingman in the contest most Mets fans were really watching. The Phillies had already buried the Mets in the N.L. East, so this was the closest thing to a pennant race to be found in Flushing.

In the bottom of the seventh, Dave got his groove back, belting a two-run shot off Ron Schueler for his 33rd home run of the season. The Mets were up 7-3, which would become the final in the game, while Kingman and Schmidt remained deadlocked in the all-important tater column.

GAME 135: September 8, 1985 — Mets 4 DODGERS 3 (14)

(Mets All-Time Game 135 Record: 20-28; Mets 1985 Record: 82-53)

The Mets were about to be done playing outside their division this Sunday in Los Angeles. That’s where their seasonlong battle for N.L. East supremacy with the Cardinals would be settled over the ensuing four weeks, which represented right and proper scheduling. Yet the Mets couldn’t leave the West behind without one final dramatic flourish so befitting the way they traveled far and wide in 1985.

Some seasons don’t pack as much drama into 162 games as the Mets did for this late-summer swing through California. They had split four games in San Francisco, all of which were either one-run or extra-inning affairs (the last of them won on a slumpbusting Keith Hernandez pinch-homer off lefty Mark Davis); they bullrushed San Diego, sweeping the Padres with eight homers in three games (five by Gary Carter across two games); they won an thirteen-inning thriller that had been scoreless for twelve in the L.A. opener, then lost a Saturday Game of the Week that featured a benches-clearing scuffle after Mariano Duncan charged Ed Lynch, a Darryl Strawberry homer to tie things in the top of the ninth and a two-out walkoff single from Mike Marshall to snap the Mets’ five-game winning streak.

On Sunday, the Mets might have been thinking “getaway game,” but they wouldn’t escape Los Angeles quickly or quietly.

Carter belted a leadoff home run in the second off Orel Hershiser for an early 1-0 Met lead. Sid Fernandez threw seven wonderful innings, marred only when Duncan’s sac fly scored Steve Sax in the fifth. El Sid’s effort was rewarded in the eighth when a wild pitch while Mookie Wilson, making his first start since returning from arthroscopic shoulder surgery, was batting gave the Mets the go-ahead run, and Hernandez’s single scored Wilson (who had reached on a Duncan error).

Fernandez came out for a pinch-hitter during the rally, giving way to Jesse Orosco. Orosco, in turn, gave away the 3-1 lead on a leadoff walk to Duncan and a game-tying two-run homer to Marshall. In what, with any luck, was a preview of the 1985 NLCS, there were certain Dodgers getting the Mets’ goats, namely Duncan and Marshall.

Hershiser stayed in one more inning and kept the Mets from scoring when he grounded Clint Hurdle back to the mound with two on. Roger McDowell took over pitching duties for the Mets in the ninth and avoided calamity for two innings. Hershiser was succeed by Ken Howell, and he kept the Mets from scoring in the tenth or eleventh. Starter Rick Aguilera became Davey Johnson’s next reliever, in the bottom of the eleventh, and he left a pair of Dodgers on base.

It was now a battle of bullpens. Lasorda placed his team’s fate in the left hand of Carlos Diaz, a reliable southpaw for the Mets a couple of years earlier before he was traded, along with supersub Bob Bailor, for Fernandez. If Diaz was in the mood to show the Mets what they gave up on, this was a good time to do it. He struck out lefties Hernandez and Strawberry to get out of the twelfth inning, and after a 1-2-3 frame from Aguilera, took care of the Mets in the top of the thirteenth. Doug Sisk succeed Aguilera and threw his own in-order inning at Enos Cabell, Marshall and Dave Anderson.

Going to the fourteenth inning, the Mets and Dodgers stayed tied at three — but in an instant, they were untied. Mookie led off against former teammate Diaz by lining his fourth home run of the year. What a good time to switch from speed (Wilson was one of five Mets with a stolen base on the day) to power. The 4-3 lead became Sisk’s to hold, and despite the righty’s generally perilous handling of his responsibilities, Doug couldn’t have been more perfect. He got three consecutive outs and the Mets flew home with another close win.

Better yet, they were flying as high as they could in the National League East. The exhilarating 7-3 trip pulled them to within a half-game of St. Louis…and when the Cardinals dropped a makeup game the next day to the Cubs, it was a dead heat atop the division. The Mets were 82-53, the Cards were 82-53. Deliciously, this meant St. Louis would be heading to Shea for a three-game set whose conclusion would determine the frontrunner in the East.

The Mets were done playing the West, potential October appointments notwithstanding. Their 46-26 record against the “other” six clubs in the league was tasty in its own right, but it was just an appetizer for what was about to come next.

“We’re ready for the Cards,” Hernandez promised.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On September 1, 1984, the annual expansion of the rosters coincided with the opening of Mets fans’ hearts for one of their longtime favorites, a player who had been missing from all the fun their team had been having as it turned around a seven-year trend of losing. Nobody could possibly appreciate returning to active duty to these Mets than one of the Mets who soldiered on while those seven years had their way with his body and went after his will to win.

Actually, there was little chance John Stearns would ever let anything get the best of his competitive instincts, no matter how much the air of seemingly endless defeat must have choked somebody so determined to prevail. He may have played on one losing Mets team after another, but the Dude was never defeated.

Except maybe physically.

The four-time All-Star catcher hadn’t caught or batted in the major leagues in more than two years thanks to an aching, injured right elbow that took its sweet time healing. Except for a handful of pinch-running appearances, Stearns had all but fallen off the Mets fan radar in 1983 and 1984. New names signifying a new era had filled the Metsopotamian consciousness during his extended absence, so while the Hernandezes, Strawberrys and Goodens led the Mets toward a hoped-for rendezvous with destiny, Stearns was…

Where was he anyway?

John was in Colorado undergoing intense rehabilitation after a pair of operations. “My life literally revolved around my arm,” he would write in the New York Times. “I became obsessed with getting it well. I read anatomy books about the elbow” and was at the point where he could “probably teach a pre-medical course on kinesiology of the elbow, complete with medical terms and definitions.”

But the only degrees Stearns was interested in were how many from the major leagues all this work was getting him. He stayed in shape but he also began to look ahead. Stearns realized there might not be any more baseball for him. As he approached his 33rd birthday, he thought about other careers. This surely wasn’t the way he wanted to go out.

“The Mets were hot and in first place,” Stearns wrote of what was going on back in Flushing without him. “I thought about all those years I had left my guts on that field at Shea playing for last place. I thought to myself how could I miss this pennant race? How could there be any justice in watching the Mets win from the sidelines? That was the lowest point for me — watching the club click and not being a part of it.”

Finally, it all began to pay off. August 1984 rolled around and Stearns wasn’t in pain. He worked out for Davey Johnson and his coaching staff. Showing he was close to contributing, the Mets sent him to Tidewater for a rehab stint. When the rosters expanded in time for a Saturday doubleheader against the West-leading Padres, John was called up.

By now, the Mets weren’t so hot and they weren’t in first place. But they weren’t out of it either. At 5½ in back of the Cubs, they needed every win they could get to remain viable as the season’s final month got underway. They got one in the opener as Gooden struck out ten Friars in eight innings. The nightcap, however, shaped up as a different, less appealing story.

The Mets started another rookie righty, one whom they hoped would follow Gooden into phenom status. Calvin Schiraldi had been their top Tide pitcher throughout ’84, and they expected big things immediately. Alas, the only big thing they got from the 6’ 5” righty was his ERA: an unsightly 10.80 after his dreadful 3⅓-inning debut left the Mets in a 5-1 hole.

Things looked bleak as the Mets batted in the fourth. With two outs, reliever Tom Gorman was due up, but Davey Johnson opted for a pinch-hitter. It would be a September callup, but no raw rookie.

It was John Stearns.

One of the best Mets from some of the worst Met years was about to get his chance with something on the line late in a very good Met season. Though he’d spent a decade as a major leaguer, you couldn’t blame the Dude if he was as nervous as kid getting his first at-bat.

“There were two outs and nobody on,” Stearns recounted in the Times regarding his first plate appearance since August 17, 1982. “Eric Show was having a good ball game. I walked to the on-deck circle in a daze. I got in the box and Show went two-and-oh on me. I was ready and I knew I was going to get a piece of cheese (baseball talk for a fastball). I saw the pitch coming and I swung. I knew I hit the ball hard, and the next thing I remember I was standing on second base with a double. The crowd was giving me a standing ovation. I didn’t know if it was a dream or what. The experience was chilling — in my top five ever!”

If it had been only a sentimental swing, it would have plenty. But it was more. It was just what the contending Mets needed. Wally Backman singled Stearns to third and Herm Winningham (debuting this same day) doubled Stearns home. Keith Hernandez would follow with a bases-loading walk, Darryl Strawberry with a bases-loaded walk and Hubie Brooks with a three-run double.

John Stearns had ignited a five-run fourth to put the Mets up 6-5. Later Straw would homer and the Mets would go on to win 10-6 for a doubleheader sweep that pushed the Mets to within five of first. Huge win for the 1984 Mets. And for John Stearns, New York Met from 1975 through 1984, a season he’d finish by catching the Mets 90th win of the year? His hit was sure to stay with him for a long time.

“George Foster called for the ball and he gave it to me after the game,” Stearns would report. “It reads, ‘Welcome Back Dude, Show, Double 9-1-84.'”

Thanks to FAFIF reader Joe Dubin for providing broadcast audio from the game of September 5, 1969.

by Jason Fry on 6 September 2011 12:58 am Periodically you’ll read one of us insisting that subpar baseball is still preferable to sitting glumly around in the winter. I was thinking of that as the Marlins, having dispatched Chris Capuano, tattooed the even more hapless D.J. Carrasco, threatening to put 20 hits on the scoreboard of the hideous Soilmaster Stadium (or, if you prefer, Joe Robbie), which — blissfully — will be no longer part of our lives in a mere two days.

Anyway, it was 9-1 and I had to ask myself: So, Jace, would you really pay money to watch this debacle in January? Can you think of something poetic to say about the arc of Carrasco’s neck as he whirls to watch another drive hurtle up the gap? Would the highlights of this mess look good interspersed with wry commentary from Doris Kearns Goodwin and Roger Angell?

Well, no. It pretty much sucked from start to finish. But I hung around, and had a moderately OK time doing so despite the on-field horrors. Keith was irascible and Gary Cohen kept goading him, which was entertaining; I wanted to see if Jose Reyes could get some hits; I wondered if Lucas Duda or Ruben Tejada would do something that would make me happy about 2012; I wanted another glimpse of newborn Mets Josh Satin and Josh Stinson and Danny Herrera; and yeah, it was baseball and soon the only variety of that will be non-Mets baseball and soon after that there will be none at all. So I watched, and got to see a little of what I wanted and a whole lot more that I didn’t want at all, until the Mets had lost.

What else did I think about during those three-odd hours?

Mostly I thought about how thoroughly glad I would be to never see this stadium again. That feeling started with the amazing emptiness of it, with the fact that you could almost hear individual conversations. It continued with Kevin Burkhardt explaining that after they wheel the old stands back to their resting positions, the members of the grounds crew walk around in the outfield with magnets to find stray bits of metal that have been shed. And it culminated with Jose Lopez’s home run being celebrated with that au courant classic “Whoomp! (There It Is)”. The Mets are now .500 all-time in this soulless vomitorium, which seems impossible; whatever their record, let me say with great fervor that the closing ceremonies for Soilmaster should end with the deployment of a tactical nuke.

The rest of the evening brought little moments that were very Metsian. There was Jason Bay’s mammoth home run in the ninth, another one of those flickering lights that will probably turn out to be a train. There was Carrasco’s horror show, followed by the inevitable discussion that D.J. is guaranteed a contract next year. There was the sighting of Ike Davis in the dugout, along with the news that he’s being doing baseball drills for two weeks without pain — glad tidings, but ones that just remind you of just how bizarre his injury was. (As Ike told the Times, “I almost wish I’d just broke it in half — I would have been back a lot faster.”) There was word that Johan Santana might wind up pitching for the Mets this month not so much because he’s ready but because the big club will be the only one still playing games..

Better news? There was word of a call-up for Val Pascucci, about whom more tomorrow. And my hoped-for sighting of the tiny Herrera, with the flat brim of his cap pulled so low over an explosion of hair that his eyes are often invisible. He’s like a Li’l Abner street rat given a uniform and told to get out there and start chucking, and so far he’s done so with decent results. A little cartoon of a pitcher with a screwball should make any Mets fan smile, right? As should whatever else baseball brings us as this ever-shortening string is played out.

by Greg Prince on 5 September 2011 1:57 pm “The Marlins celebrated when it was over. I have always felt bad for them because they were a good team and no one came to watch them play. Now I was glad that their stadium was always empty, that they were last in the majors in attendance. I hoped that they would languish unloved and unnoticed for a very long time to come.”

—Dana Brand, The Last Days of Shea

Yeah, I hate the Marlins. We all hate the Marlins. If we didn’t hate them before the penultimate final day at Shea, then we sure did by the final, final day at Shea. Part and parcel of hating the Marlins is mocking their miserable excuse for a ballpark.

It’s not a ballpark, not in the sense that it was built for baseball. It wasn’t even built for baseball and football as Shea and so many of Shea’s contemporaries were. It was clearly a football stadium, named for a football team owner. It was Joe Robbie Stadium, christened as such in 1987, when it opened as host to the Miami Dolphins, and remained Joe Robbie Stadium in 1993, when it invited the Florida Marlins in through some side gate.

It never looked right on TV, no matter that they sort of tried to retro it up the Marlins’ first year (before anybody but the Orioles was working nostalgia in to their overall presentation). The Marlins tried to make chicken salad out of Chicken of the Sea, as it were. A place so obviously built for football was awkwardly aligned for baseball. They put up an old-fashioned scoreboard and attempted to give the outfield some crazy angles as if the Marlins were playing hard against some sidewalk, not the Florida Turnpike. As Mets fans, we had to take visceral pleasure in the orange seats; goodness knows there always seemed to be plenty of Mets fans in the area to fill a few, even as most went unfilled by anybody after a while.

I couldn’t tell you what it was like inside Joe Robbie Stadium. Never went down there for a game. Never particularly tempted. Given my modest ties to the Miami-Fort Lauderdale market (my parents used to have a condo in nearby Hallandale, and I spent not a few childhood birthdays, coming as they did over Christmas break, in Miami Beach), I might have guessed I’d find my way there, but never did. Maybe with the new ballpark, which will be an actual ballpark. Assuming the Marlins would someday get one, I figured I’d hold off on renewing my acquaintance with South Florida until they had one.

They never did with Joe Robbie Stadium. They had the last National League facility worthy of universal derision. We derided it regularly here. We were fascinated by the inability of the Marlins’ grounds crew to find proper storage for its sacks of Soilmaster. They just piled up in the dugouts, which looked rather minor league, except I recently attended my first Long Island Ducks game and I can report there was no sign of Soilmaster in the dugouts.

The emptiness, the desperate configuration, the 80% chance of showers, the fire sales going on in the background, the sacks of Soilmaster in the foreground…Joe Robbie Stadium never gained traction as an attraction for baseball.

And they couldn’t even be bothered to call it Joe Robbie Stadium after a while. Like Jack Murphy in San Diego, Joe Robbie was directly responsible for there being big-time, professional sports in Miami. Like Jack Murphy in San Diego, a stadium stood with his name on the front to honor his actions. Like Jack Murphy, nobody who had a hand in preserving local legacies gave a damn and eventually ripped the name down and sold it to the highest bidder. Or in the case of this place, a series of highest bidders.

What’s Joe Robbie Stadium called today? It’s called Joe Robbie Stadium as far as I’m concerned. Like Lionel Richie in “Sail On,” I’m giving it back its name for these final three games the Mets will ever play there. The Marlins are moving out and it will no longer be part of our baseball routine. I can’t say a modicum of respect is due, considering it’s the Marlins, but 19 seasons of Mets history have taken place an intermittent series at a time in Joe Robbie Stadium, so in honor of that much, enough with the revolving-door marquee.

Joe Robbie Stadium is where the dreadful 1993 Mets broke an unfathomable 65-game streak of not winning two in a row (as a Marlins grounds crew member was practically swallowed whole by a tarp attempting to cover the field during our first visit in).

Joe Robbie Stadium is where the still-dreadful 1993 Mets decided to make a last stand and win their final six in a row, the very last of them including a Dwight Gooden pinch-hit triple and an extensive rain delay in the ninth inning of Game 162.

Joe Robbie Stadium is where Gooden won his final game as a Met, in 1994, though we didn’t know that’s what it was at the time.

Joe Robbie Stadium is where the 1997 Mets were asked to lose one more game to allow the 1997 Marlins to clinch their first playoff spot — the Mets had chased and chased them but ran out of gas — but wouldn’t cooperate. Those Bobby V Mets took three straight and kept the champagne corked. It didn’t amount to much (the Marlins clinched soon enough) but it filled me with recurring 1997 Mets pride all over again.

Joe Robbie Stadium is where Mike Piazza, former Marlin of the changing-planes variety, played his first road games as a Met, in 1998. Got six hits in two games to give us the idea he was a good get.

Joe Robbie Stadium is where another new Met, Rickey Henderson, assured us he was a young 40 when, in April of 1999, he collected four hits, scored four runs and belted two homers.

Joe Robbie Stadium is where an incredibly unlikely late-season pennant run gathered genuine momentum in 2001, with three consecutive wins on September 7, September 8 and September 9, the last of those a nearly four-hour 9-7 barnburner.

Joe Robbie Stadium is where Jae Seo, David Weathers and Armando Benitez faced exactly 27 batters in 2003, a Mets first: one hit allowed, and that hit erased on a double play.

Joe Robbie Stadium is where Pedro Martinez was thoughtful enough to strike out 10 Marlins in 8 innings on Friday night, May 27, 2005, defeating Brian Moehler, 1-0. Why was that thoughtful? It occurred a few hours after my cat Bernie passed away, and I could never get over Pedro lining up all those Fishes in a row in tribute. (Bernie, like Pedro, loved to devour fish.)

Joe Robbie Stadium is where the Mets took a break from collapsing and stood upright on the second-to-last weekend of 2007, when Moises Alou set the Met hitting streak record, Oliver Perez tossed a gem and Aaron Sele didn’t blow up in extra innings. They were still plainly doomed, but three wins down the stretch are three wins down the stretch.

Joe Robbie Stadium is where the Mets were down to their final out and trailing by a run when Carlos Beltran absolutely blasted a grand slam off Kevin Gregg as August 2008 wound down. Two days later, Nick Evans chipped in his first major league homer and the Mets reached September in first place.

Joe Robbie Stadium is where Johan Santana and Josh Johnson offered lovers of pitching an early-season festival of strikes in 2009. It was a sight to behold, even if a fly to left wasn’t something Daniel Murphy could hold.

Joe Robbie Stadium is where Francisco Rodriguez blew his first save in the Mets’ second game of 2011, but Jose Reyes, Angel Pagan, David Wright and Willie Harris all decided to give us a taste of team that wouldn’t fold up at the first flash of adversity. They effected a tenth-inning rally, and some dude named Blaine Boyer saved it from there.

They weren’t all happy days down Florida way, so no need to take a cab ride in search of bad memories, Dominican food or the inevitable passel of walkoff losses. The overall vibe from the permanently temporary home of the Marlins wasn’t great and I won’t miss seeing it. But we did witness a few pretty decent things there across two decades, and I just wanted to note it in one place. If not for Joe Robbie Stadium’s sake, then for ours.

Now let’s go out and kick the Soilmaster out of those bastards.

by Greg Prince on 4 September 2011 9:53 pm With his no-doubt, game-tying sixth-inning homer Sunday afternoon in Washington, Lucas Duda moved himself into serious contention for quite possibly, maybe, just maybe leading the 2011 Mets in home runs.

Duda is fourth on the team right now with nine. He’s one behind Jason Bay for third. Bay has ten, or two fewer than David Wright, who has twelve.

They all trail a Met who hasn’t been a Met for more than a month.

Carlos Beltran is a San Francisco Giant, which isn’t as great a thing to be as one might have thought on July 27 when our then right fielder and erstwhile center fielder was shipped west to solidify San Fran’s pennant drive. The Jints proceeded to turn the cable car around and drive in the wrong direction from there — or maybe the Diamondbacks flat out flattened them. However their tête-à-tête is resolved (and it appears to be going vastly in Arizona’s favor), the one place where one Giant is surely still in first place is the Mets’ home run list.

Carlos still has the home field advantage here. Never mind that he hasn’t gone deep in our uniform since July 20, when he took the Cardinals’ Kyle McLellean over the SNY crew’s heads and onto the Pepsi Porch. His fifteenth homer of the season would leave him with a lead of eight over Wright, nine over Bay and fourteen over dark horse Duda when it came time for him to leave.

Beltran’s final game as a Met was July 26, the Mets 103rd of the season. The team has since played 35 contests without him, yet still their sluggers chase him…sort of. I doubt “Let’s get Beltran!” has been a clubhouse rallying cry, though now that Lucas is loosening the lid on his power and David’s back isn’t giving him any reported trouble and Bay is, uh….anyway, is anyone gonna catch No. 15 and his 15 big ones?

I really don’t know. There was a time when if you gave David Wright 24 games to hit three home runs, there was no doubt he’d do it. That was before they moved his home games from Shea Stadium to within prison exercise yard-high walls. Bay also used to be quite capable of slugging his way out of a paper bag, and Saturday night in Washington indicated he can still get ahold of one now and then. As for Duda, the kid may be just comfortable enough to blast another half-dozen homers in two-dozen more games.

Working against any Met catching the ex-Met for team leadership when this season goes into the books? Fifteen of our 24 games remaining will be played at Citi Field, where no Met hit a home run during the last homestand. Think about it: six games, zero home runs. The Met total for the year thus far is 43 roundtrippers in 66 Citi dates. Not that home runs are necessary to manufacture wins. Bay and Nick Evans went deep on Saturday and the Mets lost anyway. Willie Harris produced a clutch pinch-single and Mike Nickeas squeezed, of all things, on Sunday, and the Mets won. But Duda’s monumental Washington shot proves how helpful it is to get one run with one swing.

And somebody besides a guy who hasn’t been on the team since July leading the team in home runs would just be better for morale.

Besides, isn’t it enough that Beltran’s 66 RBIs still lead all Mets by fifteen…and that Daniel Murphy, out since August 7, has played in more games than any Met in 2011?

by Greg Prince on 4 September 2011 2:16 am Your USF Bulls had just seen their hard-earned lead trimmed to three points in the final minute of the fourth quarter when Notre Dame attempted an onside kick. It was still a longshot, but if they recovered, then the Irish would have the ball around their own 45 and if everything were to go spookily right for them — and wrong for us — in the ensuing 21 seconds, they could have attempted to kick a tying field goal, and everything that had been good, green and gold about my alma mater’s first trip to South Bend for football would have gone instead to hell.

But Lindsey Lamar, junior wide receiver in on coverage as part of the hands team, expertly snatched Notre Dame’s last prayer out of the air on its luckiest bounce and Your USF Bulls held on to win a most gratifying season-opener, 23-20.

You might even say metaphorical lightning struck, considering this was hallowed Notre Dame, wake up the echoes and all that tripe (my cognitively dissonant love for Rudy notwithstanding), while we are USF, a school whose pigskin tradition dates back a solid fifteen seasons now. Actually, you’d definitely have to say lightning struck. It struck so much that officials halted the game twice, delaying it in progress for nearly three combined hours, necessitating the shifting of its conclusion from NBC to Versus. But that’s OK. Your USF Bulls hail from Tampa, where we would get lightning like the British took tea: every afternoon by four.

I began attending the University of South Florida thirty years ago this week. We had no football then. We had intramural softball. I went out for it, and then came back from it, realizing how overmatched I was by the proliferation of athletic specimens populating my dorm. But I was always willing to lend out my glove to one guy or another on whatever floor I lived for four years. And I went to a few basketball games, so don’t say I didn’t — or don’t — have school spirit.

Yes indeed, I’d been looking forward to this game ever since I discovered it on the USF schedule. I mean little old USF (not so little, with more than 45,000 students, and not so old, with its charter dating to 1956 and its football team kicking off in 1997) versus vaunted Notre Dame! Vaunted despite producing Aaron Heilman! Best of all, it was penciled in perfectly for optimal Saturday viewing. Watch the Bulls stampede the Irish at 3:30, engage in a triumphant round of “The Bull” when it was over, and then mentally change out of my gridiron gear for my usual psychological ensemble of blue and orange at seven.

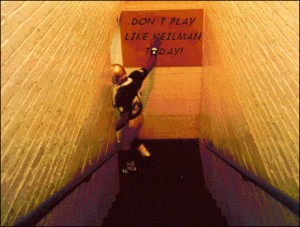

Timeless 2008 advice from Metstradamus, offered here to Bobby Parnell in 2011. But then, like I said, lightning struck, and football bled into baseball, and the Bulls and Mets kind of morphed into one big home team for me, with B.J. Daniels directing the offense and Manny Acosta heading up special teams and Jason Bay finding himself in the unfamiliar position of being untouched in the end zone for a tying score.

It was all going to work, too, Indiana weather or not. The Bulls took care of business by not blowing a lead and the Mets were on the verge of the same by overcoming a harrowing deficit. All I needed for a perfect Saturday was one inning — three outs — from Bobby Parnell.

I still need a couple of those outs.

And I still need the Nationals stopped on their final desperation drive.

And I still need Coach Collins to not employ the prevent defense because, as the habitually quoted Warner Wolf made clear, all it does is prevent you from winning.

The blur crystallized clearly in the bottom of the ninth. The Bulls’ marvelous Saturday was not transferable to the Mets. The Nationals read Collins’s intentional bases-loading scheme expertly. Lucas Duda could not snatch the Nats’ last prayer out of the air. And Parnell proved once more that his are not yet the hands in which you wish to place a tenuous lead late in a game.

We win, 23-20. We lose, 8-7. At least one of my teams knows how to close out an opponent.

The above image, concocted in Heilemanesque times, was borrowed from the mighty, mighty Metstradamus. Always treat yourself to his game stories, particularly after bullpen meltdowns like Saturday’s.

by Greg Prince on 3 September 2011 9:13 am I’m very happy David Wright launched a three-run homer to give the Mets an immediate lead in Washington. I’m very happy David can now say he’s homered at Nationals Park, the last N.L. holdout where his slugging was concerned (he’s homered in all the other Senior Circuit ballparks — even Citi Field).

I’m very happy Nick Evans and Lucas Duda joined him as partners in power. It was too long since a Met hit a home run (it hadn’t happened since they were last on the road; what a coincidence), so having it come in threes was welcome.

I’m very happy that despite R.A. Dickey deeming his knuckler “putrid,” it was pitch enough to baffle the battlin’ Nats.

I’m very happy that our bullpen was uncommonly leakproof, with two new fellows, Josh Stinson and Daniel Herrera, providing eighth- and ninth-inning sealant.

I’m very happy Stinson drew a walk his first time up in the majors, and that somebody packing uncommon curiosity thought to look up how many other Mets pitchers did that (two homegrown hurlers of varied renown and one DH-league refugee, per literally the most curious Mets fan I know).

Such happiness for such a solid win when the Mets are playing generally solid ball again. The last time they won on a Friday night in Washington, I was ever so close to considering them contenders. Then they went out and lost 17 of 22, and I reverted to considering them roadkill. Now they’ve taken seven of eight and I’m happy to consider them at all this late in a generally lost season.

Happy, happy…but not so much joy where the one thing for which I’m really rooting this September is concerned.

When is Jose Reyes going to start hitting again? I mean really hitting? I mean hitting enough to put distance between himself, the leading batter in the National League by average, and his closest competitor, Ryan Braun of the Milwaukee Brewers?

What’s happening now is the opposite of that. Back in the halcyon days of June and earliest July, it was Jose who was setting the pace, pulling away, altering our perception of what a “good” season was.

Then…hamstrings. Stupid hamstrings. Saboteur hamstrings. They’re Jose’s, but it’s like they’re conspiring with Braun.

When Reyes went out the first time, on July 2, his league-leading batting average was .354. Second to him, for all intents and purposes, was nobody. He had this thing cold. I wasn’t worried about Ryan Braun or anybody on any other team in 2011. I was focused on Jose and looking forward to him necessitating new lines in the 2012 media guide.

He could top John Olerud’s .354 from 1998.

He could top Lance Johnson’s 227 from 1996.

And, if all concerned parties came to their senses, he could continue to be listed in the current players’ section next year, not just as a set of fabulous notations where they list the Met records.

The first injury made One Dog tough to catch, but for a while the DL stay didn’t put Jose out of Lance’s hit range. The second one, on August 7, took care of that. And Olerud’s average didn’t seem so out of the question, either, not as late as July 27, when Jose was at .347. Two weeks later, Jose was down to .336 and out for three more weeks.

So the King of All Met-ia wasn’t available to Jose Reyes at this time. Still, there was the National League batting crown. His lead wasn’t as robust as it was before the first DL trip, but when the second one lapsed, he remained out in front of the field. Thus, all Jose Cubed had to do was line some balls into some gaps on a fairly regular basis and the batting title — a Met first after fifty years — would take care of itself.

As of this morning, Jose Reyes is batting .333 and Ryan Braun is batting .332, making him the first Met to hold a batting average lead in September. Nevertheless, it’s close. It’s too close for proverbial comfort or daylight. It’s extend-the-decimals-rightward close. If you do that, it’s Jose at .333333 and Braun at .331924.

Jose Reyes leads Ryan Braun by one point. This feels a bit like it felt when the Mets led the Phillies by one game in another September after they had their division cold.

Strangely enough, Braun went out for several games in early July at the exact same time Jose did. He trailed Jose by 34 points (or .034, if you want to be mathematical about it). But he came back right after the All-Star break and began finding his groove just as Jose was rehabbing. Then, while Jose cooled his hammies most of August, Braun heated up. On the day of Reyes’s return, August 29, Braun greeted him with a .334 average, hot on the heels of Jose’s .336.

Jose has an adorable, little hitting streak of five games going since his re-emergence, yet his average has dipped three points. What’s more, I’m almost certain that just about all of his hits have been lucky ones this week (or, put more fancily, beneficiaries of defensive misplays). You need some luck to win a batting title, but where’s the Jose who made his own luck? There’s not always going to be an Emilio Bonifacio fumbling around an infield near you. Sooner or later, if you want to be the best batter in your league, you have to bat like it.

Batting titles have been devalued in the advanced statistical onslaught of the 21st century. By itself, a high average doesn’t prove that much, except that you’ve succeeded in a higher proportion of your at-bats than anybody else, and that maybe you had a friendly official scorer giving you a hand. It doesn’t speak to production or situations or full base-reaching ability or all-around value. It is almost a vestige from another time, when nobody stopped to think about what else there was to baseball than wins for pitchers and averages for hitters.

But y’know what? Now that one of these is within our grasp, I’m interested in batting average on its own merits, exclusive of revelatory implications or sophisticated conclusions. I’m interested that one of the oldest, most revered measurements of a player can be earned by one of ours. No Met has done it. It’s right there with no Met has won an MVP award and no Met has pitched a no-hitter.

Only once has a Met seriously contended for a batting title — Cleon Jones, in 1969. He led the league much of the year, topping everybody as late as August 12. He was surpassed late in the season by Roberto Clemente whom, in turn, was passed by Pete Rose. Not bad company to keep in a Top Three, but how nice it would have been had Cleon beaten them out instead of falling .008 short of Rose and .005 shy of Clemente.

Injury did in Jones’s quest. A cracked rib sidelined our left fielder for the better part of three weeks as September dawned. He was batting .351 when August ended, .346 entering the N.L. East clincher, and .340 when the season was over. That was a phenomenal mark — the best any Met achieved until Olerud in 1998 — but it wasn’t enough. Rose was at .343 on August 31 and surged, while Clemente, who had ridden as high as .362 on August 18, slumped.

Of course while Pete and Roberto sat idle after October 2, 1969, Cleon was still playing baseball clear to October 16. He caught a fly ball from 2011 Washington Nationals manager Davey Johnson to end that day’s game and engrave his image into the collective Mets consciousness for eternity. Placing third (behind two all-timers, no less) in a batting race was just a detail compared to winning the World Series.

We don’t have that kind of consolation on the table presently. Jose Reyes’s Mets of today won’t be doing what Cleon Jones’s Mets of 42 years ago were doing across September and October. The Jose Reyes Mets pale next to the John Olerud Mets of 1998 and, for that matter, the Dave Magadan Mets of 1990 in terms of presenting broader team-oriented goals at this time of year. Oly finished second to Larry Walker (.363) in ’98, but was never really close to wearing the crown despite briefly nosing ahead of the pack at the turn of September. Mags, at .328, finished two points behind Eddie Murray in ’90, but seven points in back of a statistical apparition: Willie McGee, shipped to the American League at August’s conclusion but with still enough plate appearances to qualify for the National League lead. When Magadan’s average was at its peak (.369 on July 4), he was — having started the season on Davey’s bench — still trying to gather enough PA’s to be eligible for the title.

Notice the nomenclature attached to all this. The title. The crown. So much regality and dignity attached to having the best batting average in a given year. You can be overrated if you win a batting title, but you can’t be underrated if you’re wearing a crown…and wouldn’t one of those validating headpieces look absolutely nifty atop Jose’s dreadlocks? The only thing that would look better would be a New York Mets cap on his noggin in 2012 and beyond.

We don’t know if he’ll deign to wear one or if the Mets will deign to (or be able to) compensate him satisfactorily for the privilege. You might figure yet another credential, like “batting champ,” on Jose’s CV might make him that much more expensive as a free agent, but at this point, a few points isn’t going to make or break his next contract.

So give us this much, Jose. You couldn’t sustain enough of an average to beat Olerud. You couldn’t collect enough hits to beat Johnson. You couldn’t stay healthy enough to start in front of Tulowitzki in Phoenix in July even though you had the votes to do so. You’re way off the pace in categories you seemed destined to own. Others lead in runs, doubles, hits and steals, and Shane Bloody Victorino and Dexter Fowler are breathing down your neck in your signature segment, triples.

Leading the National League in batting average is all that’s left for you and us now. You take that and no matter where you are next year, we’ll always have it. We’ll always be able to literally point to Reyes N.Y. and tell the doubters and the legions of uninformed, “Look — we had a Met who was better at anybody at this big thing. We had Jose Reyes, the best hitter by this revered measurement in 2011. He held the title. He wore the crown. We could show you video or go into detail, but we don’t have to. He’s got the average that was farther above average than anybody’s.”

I’d like to be able to do that, Jose, so fend off Ryan Braun and the rest of those pretenders to your throne, would you?

by Greg Prince on 2 September 2011 12:11 pm Welcome to The Happiest Recap, a solid gold slate of New York Mets games culled from every schedule the Mets have ever played en route to this, their fiftieth year in baseball. We’ve created a dream season that includes the “best” 130th game in any Mets season, the “best” 131st game in any Mets season, the “best” 132nd game in any Mets season…and we keep going from there until we have a completed schedule worthy of Bob Murphy coming back with the Happy Recap after this word from our sponsor on the WFAN Mets Radio Network.

GAME 130: August 29, 1988 — METS 6 Padres 0

(Mets All-Time Game 130 Record: 21-27; Mets 1988 Record: 77-53)

One star was just beginning to burn incandescently. Another appeared suddenly on the horizon. All things considered, Shea Stadium seemed to be evolving into quite the stellar galaxy.

After struggling to gather momentum across the summer, the first-place Mets kicked their pennant drive into highest gear while on the West Coast. They swept the Dodgers a three-game series before coming home to take a pair of games from the Giants. They lost the finale of the San Francisco set — but found an startling new weapon.

Gregg Jefferies made his 1988 Met debut in that Sunday loss. The two time Baseball America Minor League Player of the Year (who’d pinch-hit in a half-dozen games the previous September) was the most hyped prospect the Mets had ever nurtured this side of Darryl Strawberry, and now that he was in Queens, he was intent on making an immediate impact. Davey Johnson started him at third, batted him second and was rewarded right away for his faith. Jefferies lined a single in the first and produced a double to deep right (and scored) in his second at-bat.

The next night, a rainy Monday against the Padres, Gregg showed he was no one-game wonder. Starting at second and again batting second, Jefferies once more stoked Mets fans’ imaginations when they saw him double and score in the first, homer to lead off the third and triple home a run in the sixth.

Other than wind up his second game as a starting infielder on a divisional leader with a .556 batting average (and 1.333 slugging percentage), what else had he done for us lately?

Jefferies was a line drive machine practically from the womb. Soon enough, the papers would be filled with stories of his father/hitting coach, his intense underwater training sessions, his carefully tended bats, his idolization of Ty Cobb and everything else that makes a legend come to life ten minutes after he arrives on the scene to stay. Gregg’s batting average after fifteen games was .400. He was no defensive prodigy, having come up as an unnatural shortstop, but Davey didn’t hesitate to write him in at second or third base almost every game for the rest of the season. By November, on the strength of 109 at-bats in 29 games, Gregg Jefferies — with 6 home runs, 17 runs batted in and a batting average of .321 — placed sixth in National League Rookie of the Year voting.

Gregg was the budding star against the Padres that Monday night, but a player who hadn’t been around the Mets all that much longer was one who truly glittered — as had become his happy habit.

David Cone entered 1988 as a middle reliever just waiting to explode into a starter. Despite the Mets’ talented rotation, it was just a matter of time before Coney made himself a regular in its ranks, and once Rick Aguilera went down with an injury, his chance materialized.

The righty didn’t waste it. His first start, in early May, yielded a shutout of Atlanta. By July, he was 9-2 and a member of the National League All-Star team. Then, in mid-August, just at the moment the Mets commenced putting space between themselves and the rest of the N.L. East, David took off into orbit.

In the second of what would eventually become eight consecutive wins in eight consecutive starts, Cone dominated the Padres. A Tony Gwynn one-out double in the fourth was the extent of the San Diego attack. Cone walked two but gave up no other hits and, despite two errors (one on a foul ball, one a stolen base attempt), let nobody else on base. When the night was over, David Cone had pitched himself a one-hitter, striking out eight and teaming with Jefferies to lead the Mets to a 6-0 win that allowed them to maintain a 6½-game margin over the fading Pirates..

Cone’s record rose to 14-3 en route to a final mark of 20-3. In any season that didn’t include Orel Hershiser stringing together 59 consecutive scoreless innings, David would have been a near-lock for the Cy Young. For now, the second-year pitcher, the rookie infielder and the other jelling Mets would have to sate themselves with a magic number that had just been reduced to 25.

Same age as Coney in 1988, come to think of it.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On September 1, 1990, it may have been a little late in the season for a new episode of Extreme Shea Makeover, yet the ratings were gangbusters as the Mets redid their look in the middle of a boiling pennant race.

With the August 31 waiver trade deadline looming, the one by which GMs have to abide if they want to add players who can join their postseason roster, and the once-hot Mets in danger of wearing down from injury and late-summer doldrums, Frank Cashen acted boldly. He obtained a deluxe defensive catcher, Charlie O’Brien, from Milwaukee. He sent two minor leaguers to Philadelphia for experienced middle infield help in Tommy Herr. He enhanced his bench by adding bases-loaded hitting wizard Pat Tabler. And he dipped down to Tidewater to shake up his veteran rotation by promoting and inserting Julio Valera, a righty coming off a decent season in the International League, into Ron Darling’s recently soft spot in the rotation.

With young Valera on the mound, Herr stationed at second and O’Brien putting down fingers behind the plate, the refurbished Mets starred on CBS’s Saturday Game of the Week, and all the changes seemed to work. Against the Giants, Herr led off the Mets’ first with a walk and came around to score, along with Dave Magadan, on Darryl Strawberry’s 30th home run of the year. Herr would lead off the fifth with a homer of his own to extend the Mets’ edge over San Francisco to 5-3, earning applause from a crowd of 40,000+ who had known him mainly as their nemesis from his Cardinals heyday in the late ’80s.

But now Herr was a new Met favorite, as was O’Brien, who guided yet another instant Flushing sensation, Valera, through six innings of three-run pitching. With holdovers Darling and Bobby Ojeda coming out of the pen, and John Franco finishing up for his 31st save (tying Jesse Orosco’s team record), the revamped Mets prevailed, 6-5, and took a half-game lead over the same old Pirates with a little over a month to go in what promised to be a divisional battle royal.

GAME 131: September 1, 1974 — METS 3 Braves 0

(Mets All-Time Game 131 Record: 22-26; Mets 1974 Record: 60-71)

A beloved Met icon and a revered Met opponent faced each other under circumstances that had been imagined as dramatic but, just as the season that was limping into its final month, were fairly underwhelming. Still, in retrospect, there was a poignancy to it that might not have been appreciated in the fleeting present of its day.

The opponent was Hank Aaron, crowned at the beginning of 1974 as the major leagues’ home run king. Really, he crowned himself, homering off Jack Billingham on Opening Day in Cincinnati to tie Babe Ruth’s allegedly unbreakable mark of 714 and taking Al Downing of the Dodgers deep four nights later in Atlanta for No. 715. Given the way things worked in those days, it was pretty much fait accompli that Aaron’s most historic home runs would come against N.L. West rivals. The schedule used to tick like clockwork — in April, you played the teams in your division. While the Braves were taking on the Reds, the Mets were preparing to begin defense of their 1973 pennant at Philadelphia before coming home to raise their flag against St. Louis.

That simple fact took off the hook any National League East pitcher who might have winkingly said, when asked the previous summer, that they wouldn’t necessarily mind being the pitcher who gave up Aaron’s 715th. Not that anybody would groove one to Bad Henry or disturb the integrity of the game…but if somebody was going to give it up and become famous for it, well…

These sentiments caught the attention of the underwhelming commissioner of baseball, Bowie Kuhn. Kuhn, who couldn’t be bothered to stick close enough to Aaron’s historic quest as it reached it climax (he missed No. 715, claiming another, more pressing engagement), let it be known with characteristic rectitude that this — the idea that a pitcher would be anything but stone-faced about being potentially part of the biggest story in baseball — was not a joking matter, even if one of the pitchers to joke about it was that beloved Met icon, Tug McGraw.

“I’d throw my best pitch,” McGraw asserted in the summer of 1973, “and hope like hell he hits it. I’d be a commodity. I’d always be in demand on the banquet circuit.”

If not exactly incendiary, Tug’s remarks struck the commissioner as borderline, so the screwballing lefthander clarified his thoughts for the press: “I didn’t feel I was misquoted. I still say that I would give Aaron my best stuff and hope like hell he hits it out. I’m not going to lay it in there. I’m not going to give it to him. But if he gets it off me, more power to him.”

Aaron finished 1973 with 713 homers, one shy of Ruth, and whatever hot water McGraw got himself in turned tepid over the winter. As he wrote in Screwball, published before Aaron would take his first swings of the following season, “Henry figured to break the record long before he played against the Mets in 1974. But if I were to end up giving him a home run this year, I suppose the commissioner would end up giving me a big investigation. The important thing, though, is that Henry Aaron will know I didn’t do it intentionally.”

For the record, McGraw — who identified a pitch he threw to the eventual home run champ in the 1969 NLCS as “one of the best screwballs I ever threw or imagined throwing” — gave up four home runs to Aaron before Hammerin’ Hank got to 714: the first he ever allowed to any big league batter, as a rookie 1965; one in 1966; one in 1969; and one in 1973. The last of those was the 698th of Aaron’s career and delivered while Tug was cast in the strange role of starter on July 17. That was the game in which Yogi Berra took a shot in the dark at fixing Tug, whose relief efforts had gone to seed all year long. McGraw was roughed up by Brave hitting, but the Mets roared back from a 7-1 deficit to win 8-7, foreshadowing what the rest of 1973 held in store for them.

While it was easy enough to figure out what 1974 had in store for Aaron when he began it sitting on 713, it would have been tough to forecast what kind of year awaited Tug. The thrill of ’73 wore off for all of the Mets, whose late-season magic did not carry over to the following April, but for McGraw, it was as if his redemption had never occurred. 1974 picked up where the doldrums of 1973 left off, with his “You Gotta Believe” heroics serving as some kind of evanescent aberration. The tone was set in the Philly opener when, attempting to protect a 4-3 lead for Tom Seaver, McGraw gave up a two-run, walkoff homer to third baseman Mike Schmidt.

And the tone never varied much from there

By late August, McGraw and Berra were back where they’d been a little more than a year earlier, each trying to figure out what was wrong with the man who had been one of the National League’s most reliable relief aces over the previous half-decade. And as Yogi did in July of ’73, he decided to give Tug a fresh start — literally. He handed Tug the ball to begin a game in Houston and the Mets won. So he did it again a few days later at Shea. This time the Braves were the opponent — and it would almost certainly be Henry Aaron’s last game against the Mets, a team he had tagged for 45 regular-season home runs since they’d entered the National League in 1962.

The first of them was off Roger Craig at County Stadium when Aaron’s team was still known as the Milwaukee Braves. The second was in New York, against Jay Hook, and it landed in the center field bleachers of the Polo Grounds, where only a couple of sluggers had ever landed a ball. He would hit one in each game against the Mets in their playoff encounter in 1969, reaching each Met starter — Seaver, Jerry Koosman and Gary Gentry — while batting .357 in Atlanta’s losing cause. The last home run he’d hit off a Met pitcher at Shea was against his former teammate, George Stone, off whom he belted two on July 8, 1973. And his last home run against a Met anywhere was the one he hit off McGraw the starter nine days later in Atlanta.

Unless he took advantage of his last opportunity against McGraw on the Sunday that began September 1974. Aaron, with 730 roundtrippers on his ledger by now, was presumed gone from the Braves, and maybe retired, after the season. Thus, 33,879 Mets fans took advantage of their last chance to see the home run king possibly do his thing against their team. Though things had calmed down between Tug and the commissioner, it wasn’t altogether without poetic justice that it would be McGraw taking on Aaron on this last trip in for Hammerin’ Hank.

With Aaron’s future unknown, it wasn’t out of the question that any homer he hit would be his last. The pitcher who gave it up would derive some measure of reflected fame for being on the wrong end of it. Thus, McGraw was asked how he felt now about perhaps giving up this historic home run to Aaron.

“I didn’t even think about Aaron until you just reminded me,” Steve Jacobson quoted Tug in his book, The Pitching Staff. “Damn you, now I’m thinking.” With thought devoted to the subject — and with his ERA hovering above 4 — the lefty declared, “I hope I strike him out four times.”

There’d be no strikeouts. But there’d be no home runs, either. McGraw faced Aaron, starting in left field for Atlanta, four times that day. Tug grounded Hank into a 6-4-3 double play to end the first. He gave up a single to him in the fourth. He got him to line to third baseman Wayne Garrett to end the sixth. And, with one out and one on in the top of the ninth — on the heels of a thirty-second standing ovation tribute from the Shea crowd — Tug McGraw threw the last pitch Hank Aaron would ever see from a New York Met.

He popped it to Felix Millan, a longtime Brave, at second base, and Millan gloved it for the second out. Tug then flied Dusty Baker to Teddy Martinez in center to give the Mets a 3-0 win and raise his own record to 6-7.

It may have represented an uneventful goodbye to New York National League baseball for Aaron, but the complete game, five-hit shutout — the first shutout of his career — would turn into an unforeseen milestone for McGraw. It became his final win as a New York Met. The next several weeks were lackluster for both the pitcher and the team. The Mets would finish up at 71-91, McGraw at 6-11. In the offseason, a new general manager, Joe McDonald, would announce there were only three “untouchables” on his roster: Seaver, Koosman and Jon Matlack. McGraw, a Met since 1965, was theoretically available, But that’s all it could be to Tug: a theory, and not a very appealing one.

“If I got traded,” he said in The Pitching Staff, “I wouldn’t even know how to put another uniform on.”

But — just as Hank Aaron would when the Braves sent him and his 733 home runs to the Milwaukee Brewers so he could finish out his career as a DH in the city where he began — Tug would learn different shades of fabric can fit just fine. On December 3, McDonald swapped Tug, Don Hahn and Dave Schneck to Philadelphia for catching prospect John Stearns, starting center fielder Del Unser and a presumed lefty bullpen replacement, Mac Scarce.

Aaron’s American League two-season goodwill tour ended in 1976, with 755 homers as his final tally. Tug’s Philadelphia tenure, however, was just getting started. After having his left shoulder repaired (the one that, it turned out, was giving him undiagnosed trouble those last two seasons with the Mets), he’d wind up pitching ten seasons less than a hundred miles from New York, with one of them, 1980, ending with McGraw on the Veterans Stadium mound, nailing down the final out of the Phillies’ first world championship.

Tug’s final game in the majors would come September 25, 1984 — at Shea Stadium. He was asked to save a 4-2 lead for Kevin Gross, but gave up a leadoff double to Hubie Brooks and a run-scoring triple to Mookie Wilson. He was removed for Larry Andersen, who, three batters later, gave up a pinch-hit, walkoff home run to Tug’s old Mets teammate, Rusty Staub. It put Staub in the record book as only the second player (alongside Ty Cobb) to hit a home run before his 20th birthday and after his 40th.

All of which somehow calls to mind the cake Tug was presented with for his 30th birthday, which fell just before that final start against Henry Aaron and that last win as a Met. It was inscribed, “Youth is like Irish whiskey. It doesn’t last long.”

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On September 3, 1985, an unprecedented Met power display was underway on the West Coast, and the sparks it threw off were deeply appreciated across the continent. Gary Carter belted three home runs off San Diego Padre pitching that Tuesday night at Jack Murphy Stadium, leading the Mets to an 8-3 victory. Three homers in one game wasn’t the unprecedented part — Darryl Strawberry had done in only a month earlier in Chicago — but the Kid adding two more homers the next night at the Murph allowed Carter to claim a Met first: five homers in two games. It was a rarity for any player on any team; Gary became the eleventh player in major league history to produce a quintet of roundtrippers in a pair of games. The last had been Dave Kingman in 1979, as a Cub, against the Mets.

There was definitely more to come for Carter as that searing September pushed forward and the Mets dueled the Cardinals toward a bitter end. Before it was over, the perennial All-Star catcher won National League Player of the Month honors for clubbing 13 home runs and driving in 34 runs, just about each of them crucial. Carter also had an indisputable hand in determining the National League Pitcher of the Month winner for September 1985. That one went to Dwight Gooden, who threw 44 innings and gave up no earned runs. Doc’s catcher in four of his five pennant-pressure starts? Gary Carter, of course.

GAME 132: August 30, 1999 — Mets 17 ASTROS 1

(Mets All-Time Game 132 Record: 22-26; Mets 1999 Record: 80-52)

The ultimate second-place hitter established himself as No. 1 in the Met record books when it comes to best game any Met hitter has ever had.

Edgardo Alfonzo was never quite the focus of the Met clubs on which he was such an essential element, and maybe that was for the best. He worked quite well just off to the side of the spotlight. Let Mike Piazza take on the glare. Fonzie seemed to have no problems operating in a bit of a superstar shadow. At his peak, Alfonzo was tabbed in a Baseball Digest cover story as “the game’s most underrated player,” with one manager testifying, “Piazza gets all the attention in New York, but Alfonzo’s the one who makes the Mets successful.”

He played Gold Glove defense at third for a couple of years before proving even better at second. He had a knack for clutch hits. He showed surprising pop for a relatively small player. He did all those little things scouts drool over right. He was as mistake-free as they came. But, no, Edgardo Alfonzo never garnered the lion’s share of Met attention…except for not getting enough attention.

Yet there was nowhere to hide this Monday night under the Astrodome roof. The quiet infielder carried far too big a stick for metaphorical soft speaking.

Edgardo cleared his throat in the top of the first with a solo home run. Perhaps reticent to stand out so ostentatiously, he gladly contributed one of six Met hits (a single) and scored one of six Met runs in the second to help build a 7-0 lead over the Astros. Perhaps feeling looser by the fourth, he treated himself to another big swing, one that resulted in a two-run homer for a 9-0 lead.

Fonzie was 3-for-3 with two home runs and three runs scored in less than half a game. Masato Yoshii was in full command from the mound and the Mets’ sure gloves, per usual in 1999, were making no errors. Everything was pretty much perfect.

So Edgardo Alfonzo improved it.

In the sixth, leading off against Sean Bergman, Fonzie blasted his third solo home run of the night, putting the Mets ahead 11-0.

In the eighth, his leadoff single set the stage for another pair of Mets runs that made the game 14-1; the first of those runs crossed the plate under the name ALFONZO and the number 13.

And in the ninth, the luck and the skill just kept coming. A one-out double that drove Todd Pratt to make it Mets 15 Astros 1 gave the Fonz six hits — a cool, new Met record. And when Shawon Dunston singled to score, in alphabetical order, Benny Agbayani and Edgardo Alfonzo, it not only provided the final score of 17-1 for the Mets, it mean Fonzie had set yet another record — six runs, one game, most ever.

AAAAAAYYYYYY!!!!!!

No other Met has ever matched Edgardo Alfonzo’s six runs or six hits, and the second baseman’s three home runs put him in limited company, as only seven other Mets (from Jim Hickman in 1965 to Carlos Beltran in 2011) have that many. And as almost a footnote, Fonzie drove in five runs in his six at-bats.

It bears repeating:

AAAAAAYYYYYY!!!!!!

The same week Fonzie was making Met history, he shared the cover of Sports Illustrated with his three infieldmates, John Olerud, Rey Ordoñez and Robin Ventura. They were featured for their fielding. In the article, Alfonzo was referred to as “heady” and was noted for having committed only four errors through five months of 1999. But that was it in a piece that was devoted mostly to Ventura. It would take a more specialized publication, like Baseball Digest, to dwell on Edgardo and proclivity for not being overly appreciated.