The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

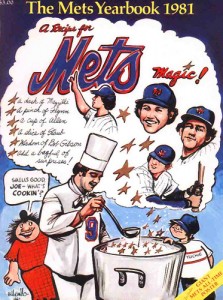

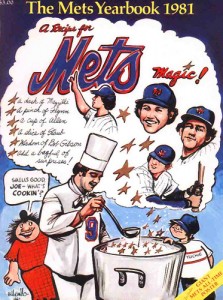

by Greg Prince on 25 August 2011 9:10 am  SNY presents Mets Yearbook: 1981 tonight at 6:30. Don’t know if it will be presented in two distinct halves with the middle third missing. SNY presents Mets Yearbook: 1981 tonight at 6:30. Don’t know if it will be presented in two distinct halves with the middle third missing.

And if you get that, you don’t have to read this. Or this. But I encourage you to, anyway. It’s an off day. You’ve got the time.

Image courtesy of “Mario Mendoza…HOF lock” at Baseball-Fever.

by Greg Prince on 25 August 2011 6:18 am What a welcome sight Wednesday. Dan Norman, getting another of his intermittent shots at starting, hit a big home run in the first and went 3-for-4. Lee Mazzilli went deep, too, while Joel Youngblood scored a couple of runs. Pete Falcone struggled with his command but hung in there better than we’ve seen in quite a while. Mario Ramirez and Bill Almon saved the day for Ed Glynn with a clutch double play — and that Jeff Reardon showed he might work out in the bullpen after all.

Afterwards, Mets manager Joe Torre, who worked so hard to raise his team’s level of play earlier in the season, was relieved to see their latest losing streak end.

All right, so that’s only who the 2011 Mets appear to me to be as this once promising campaign limps through its denouement. For even when they win one against a club the caliber of the Phillies (who are pretty good even without Mike Schmidt in the lineup), I feel I’ve been here before.

As FAFIF reader Guy Kipp has suggested on a couple of occasions (and I’ve found myself thinking), the current Mets squad is riding a trajectory eerily similar to that of the 1980 Mets — which is no random comparison to anyone who was around and coming of age at the dawn of the Fred Wilpon era.

Quick review of the statistical similarities:

1980 — dismal 9-18 start

2011 — dismal 5-13 start

1980 — energizing 47-39 surge

2011 — energizing 50-38 surge

1980 — crushing 11-38 finish

2011 — crushing 6-17 beginning of the end

Close, right? And those are just the wins and losses. How they got where they got is strikingly similar, too.

The 1980/2011 Mets were coming off a string of demoralizing seasons and entered their schedule with no hope. They offered no evidence there should be any hope as they stumbled from the gate. Then, with no notice and to little fanfare, they began to emerge from their miasma. They played with generous dollops of verve and panache. They kept after allegedly superior opponents and refused to take line scores seriously until they took their last licks.

Their most inspirational stretches were never as lengthy as they felt and they never stayed hot long enough or drew close enough to the top to lure nonbelievers into believing alongside us, but whatever it was they gave us just kept giving, and we accepted it graciously as we did hungrily.

Then one day, it all stopped. We looked up and the team of whom we’d grown so enamored was no longer capable of giving us much at all. Injuries got them. Depth got them. Talent or the lack thereof got them. Youth got them. The 162-game schedule had its way with them.

Thing is, when Mets fans of my vintage talk about 1980 decades later — and I’m confident no Mets fan talks about 1980 decades later as much as I do — it’s not to dwell on the crash of August and September. It’s to romanticize May and June and July, certainly the parts of it that made us feel like world-beaters. I was 17 that spring and summer, so I was susceptible to seeing the Mets only at their best. I saw the 47-39 and clung to it through the 11-38, through the 17-34 pre-strike portion of 1981, well into 1982 even as 1982 was disintegrating. It took me ages to discern I wasn’t seeing what I could have sworn I had seen so clearly.

When I finally figured out that the 47-39 Mets of mid-1980…

• the Mets of the Steve Henderson home run that beat the Giants;

• and the Mike Jorgensen grand slam that beat the Dodgers;

• and the sincerely thrilling quest to reach and maybe surpass .500;

• and the sense that we were never out of a game;

• and the conviction that we had finally turned a corner…

…were not, in fact, representative of who the Mets were at the major league level for the long-term — and was overcome by disgust that I had been taken in by mediocrity disguised as eternal rebuilding — the Mets at the minor league level were coming together and preparing to rescue all of us from the stubborn stagnation that had been choking our baseball-loving lives almost without pause since 1977.

But there was that pause, and it was beautiful, even if it only spanned 86 games. Eighty-six games I still romanticize thirty-one summers after they happened.

The comparisons between 1980 and 2011 aren’t perfect. The 1980 Mets never traded a Carlos Beltran. They didn’t have a Carlos Beltran (though they did trade for Claudell Washington). They didn’t have a high-end payroll. They had their ownership-related turmoil settled by Opening Day. If anybody tried to sell us “The Magic Is Back” today, we’d snarkily Tweet them to bits. And though there are plenty of Met pitchers in 2011 who can give up distant home runs in the best tradition of Mark “Boom Boom” Bomback, nobody’s cap seems to fall off as frequently as John Pacella’s.

But they, in 1980, did have a new regime that couldn’t do much with the hand it was dealt so it worked on the next hand and the hand after that. They did have a slew of spunky overachievers whose lovable pluck compensated for their limited abilities. And they did have too many Mets on the disabled list after a while — too many for reinforcements from Tidewater to do anything about.

John Stearns and Doug Flynn, meet Jose Reyes and Daniel Murphy.

They fell apart in August 1980 just as they’ve fallen apart in August 2011. It was very unpretty then as it is ugly now. But I was 17 then and considered myself so blessed to have been graced by 47-39 that I didn’t let 11-38 get me down completely. Oh, I knew it was a terrible way to bring the curtain down on a show whose second act soared (first big breaks that September for chorus members Mookie Wilson, Hubie Brooks and Wally Backman notwithstanding), but I was willing to hum the scenery when it was over at 67-95. It was the best Met production in four years and I was an easy audience.

Now, not as much. I’ve ridden far too many ups and downs across my fan life to buy into 2011’s 50-38 for any more than what it was. And when 50-38 dwindles into 6-17 and wherever it goes from here, I need a lot more than advance notices on behalf of the potentially promising understudies to rev me up for the next set of previews.

But I sure hope there are Mets fans younger than me and less cynical than me who see in 50-38 what I saw in 47-39. I hope those Mets fans, whatever their age and level of susceptibility, remember 2011 as the year those fill-ins came up from Buffalo and kept the Mets afloat; the year the Mets turned a 7-0 deficit against the Pirates into a 9-8 triumph; the year Lucas Duda won a game that seemed hopelessly lost against the Padres; the year Jason Bay wouldn’t give in to Mariano Rivera; the year Scott Hairston stunned Brian Wilson; the year the Mets defied the odds for several months and rose above .500 and, for a minute or two, appeared to be legitimate contenders.

I hope those Mets fans remember 2011 not for how badly it began and how miserably it might have ended but for being, at its heart, the kind of season they will always romanticize no matter its final record.

Every Mets fan deserves a 1980. The good part, I mean.

by Greg Prince on 24 August 2011 7:50 am I’ve seen Mets teams in free fall. What’s going on these days isn’t that. They’re not falling. They fell and are incapable of getting up. I can’t even say this is the worst I’ve seen them play in years, and not just because I can go back two years and say I saw much worse.

It’s not the playing and failing to generate positive results that’s distressing. It’s that it doesn’t feel like the Mets are playing at all. It doesn’t feel like the Mets are participating in the games where ancillary evidence suggests they represent half of the participants. They are almost literally not in any game they play lately. It’s as if the Mets, to borrow from Sheryl Crow, are strangers in their own lives. Watching their games and reading their reactions night after night this August brings on a sad, helpless feeling — or would if I could summon any feeling at all for what’s become of the 2011 Mets.

As the Mets proved incapable of pushing across any of their myriad baserunners in the first two innings at Philadelphia Tuesday night…and then receded into their offensive shell…and then stepped helpfully out of the Phillies’ way so they could rack up yet another high score on the Citizens Bank pinball machine…as they were doing that, they almost ceased to exist. They got tinier and tinier until there was nobody on the field in the bottoms of innings, certainly nobody at bat in the top of them. There was no Mets catcher, no Mets first baseman, no Mets right fielder — there was nothing and nobody holding down their portion of the game.

Thus, it was tough to get upset with nobody. Howie Rose for a while — somewhere between 5-0 and 9-0 — spoke with great concern about the Mets not losing what they had when they were pretty good during this season. Terry Collins had their heads in the game and their tails busting down the line and their fans — us — trusting them again. Howie was really worried all that heartening progress would evaporate over the final month and Collins’s hard-won cultural changes would be for naught if current trends persisted.

I wasn’t. Everything that was good about 2011 has already disappeared. I feel no connection to whatever it was that kindled my affection for the Mets for swaths of the schedule. When I listen and when I watch, I don’t see the Mets who exceeded my meager expectations. I mean I literally don’t see the Mets who were at the forefront of their moments of revival: no Beltran, no Reyes, no Murphy (no Rodriguez, even). Beyond naming names, though, I saw no team. I saw no cohesiveness. I saw no ability. I saw no talent. I won’t say I saw no heart because that’s a damning indictment of anybody, but I didn’t see any of that, either. Yet I can’t say I was looking for it.

The Mets have heart? Good for them. Most of them show such limited ability or talent at this juncture that heart isn’t going to do them much good.

Listen, you can come at me with individual cases of young players who are showing a little something here or there and bullet-point how this one or that one might fit into a developing big picture down the road once you stir in those prospects whom you haven’t seen but count on nonetheless, and I won’t argue. But I also can’t see any of it materializing in the present, and the present is what we have 34 more games of. The present is the summer, and the summer is the quarter of the year it’s all about. The summer is the only quarter of the year where baseball shows up every day. I hate to see it go, even when it’s this bad. But I also hate to see it so bad that it feels like it’s not there.

The summer’s slipping away as summers tend to do. There’s only fall and winter ahead. Fall and winter and their detestable baseball-less void. There’s nothingness. It happens every year at this time, though in some years at this time I don’t notice because the Mets engage me with the reasonable hope that they will keep playing, keep competing, keep winning, keep the fall vibrant and keep the winter away as long as they can.

The Mets don’t engage these days. None of them They are not vital. They are pulseless. On paper, it’s sad. In substance, it’s empty. Their Augusts have been stunning white canvasses of nothingness three years in a row. We’ve been told or choose to convince ourselves that the blankness is wonderful right now because we have a front office of Picassos and Rembrandts who, given the opportunity, will begin to fill in our blank canvas with vibrant color and texture and won’t 2013 or 2014 be something?

Maybe. I’m still here in 2011. The canvas just stares back at me. Angel Pagan just overthrows everybody. Jason Bay just pops out. David Wright requests meetings. Johan Santana never returns. Jon Niese never progresses, and then goes on the DL. The bases remain loaded and then the bases never come close to being filled.

And Nick Evans just kind of wanders by from time to time, year after year.

During one of the Phillies’ many rallies Tuesday night I tried to spark some righteous anger within my soul, but couldn’t. I wanted to say “blow the whole thing up,” but there’s nothing left to blow up. What are you going to blow up? Justin Turner? Josh Thole? Umpteen relievers, none of whom you trust to get you out of a paper bag let alone a tense situation of second and third and nobody out? This thing can’t be blown up. This thing is hollow. Blow it up and there’ll be air.

I’ve tried to piece together a 2012 from here. I can’t do it yet. There’s a well-meaning, capable third baseman, a dynamite shortstop whose open-market value overrides everything (even his hamstrings), a left fielder who should be Fortune magazine’s man of the decade and a bunch of guys in whom I have no particular faith. A few might turn into something. A bunch more probably won’t. Ike Davis still isn’t running, so I can’t even pencil him onto my imaginary lineup card. The prospects I haven’t seen are exactly that. Call me when they’re close.

So, no, Howie, I’m not worried about these guys not building on whatever foundation Terry convinced them to construct in May and June and July. These guys probably won’t be the ones charged with the responsibility of laying in a first floor. For the Mets to provide the kinds of Augusts that excite us about Septembers and Octobers and the Aprils that follow, we’ll need mostly new Mets. Mets that don’t fade into 5-17 oblivion. Mets that don’t take four of seven from the Padres and lose 14 of 15 to everybody else.

These Mets are a holding action. And they’ve lost their grip completely.

by Greg Prince on 23 August 2011 4:08 pm Welcome to The Happiest Recap, a solid gold slate of New York Mets games culled from every schedule the Mets have ever played en route to this, their fiftieth year in baseball. We’ve created a dream season that includes the “best” 121st game in any Mets season, the “best” 122nd game in any Mets season, the “best” 123rd game in any Mets season…and we keep going from there until we have a completed schedule worthy of Bob Murphy coming back with the Happy Recap after this word from our sponsor on the WFAN Mets Radio Network.

GAME 121: August 21, 2004 — Mets 11 GIANTS 9 (12)

(Mets All-Time Game 121 Record: 22-26; Mets 2004 Record: 59-62)

When this Saturday afternoon contest at then SBC Park was waged and waged and waged some more, the Mets had only recently tumbled out of a surprise pennant race. In mid-July, they were one out of first. In a matter of weeks, they fluttered gently from second to fourth, double-digits away from the lead. The residual good vibes from having been pluckily competitive vanished pretty quickly. Players were going down up the middle and on the mound. Piazza, Matsui, Reyes (again) and Zambrano (new guy) all punched in on the DL. The natives of Metsopotamia were restless because of recent trades of top prospects (mainly Scott Kazmir for the injured Zambrano). Ownership seemed more clueless than usual. As the series in San Francisco proceeded to its middle — a Fox game — the Mets were a limping, losing, lame legion.

Yet on this particular Saturday, they lit a candle and averted the darkness.

Games like this one deserve a name. The Buckner Game: we know what that is. The Grand Slam Single Game. This wasn’t as momentous as those, or even the more colloquial Matt Franco or Ten-Run Inning Games. This was, though, perhaps the brightest 1/162nd of a sagging schedule. It’s best recognized for its singularity, perhaps, with multiple names.

The Sunshine Game. An appropriate Met-aphor, actually, as it is grim and wet in New York (the Yankees endure a 3+ hour rain delay in the Bronx), but brilliantly sunny in San Fran. You really notice that sort of thing. Hmmm…

The Tooth Or Consequences Game. When he was a Brave, Mets fans fantasized about the Mets knocking out their disturbingly stoic nemesis, T#m Gl@vine. It took his becoming a Met for that to become reality. Only a Met, probably only this miscast version of one, could make the approximately 10-second journey from LaGuardia to Shea into a mouthful of woe. His cab stopped short and Gl@v!ne lost teeth and gained stitches. He missed two starts. San Francisco was his attempt to see if his mouth could keep up with his left arm.

The Conflicted Loyalties Game. Ex-Met nemesis turned Met vs. beloved Met icon turned opponent. What an odd matchup for any Mets fan with even modest long-term memory. The Giant is Edgardo Alfonzo, who comes up with two on and one out in the bottom of the first and rips a ground rule double that makes the score 2-0 for his team…the Giants. 2004 Mets All-Star T#m trails. Fonzie, for the moment, rules.

The Clifford Cove Game. Cliff Floyd swings mightily. Maybe not as irresponsibly as Dave Kingman, but he does seem to approach pitches at one speed: overdrive. It’s not necessarily a terribly successful approach. But in the top of the fifth, with the game tied at three and two on, Cliff Floyd swings mightily and launches one into the bright California sky and into McCovey Cove. He becomes the seventh visiting player to get wet. Mets up 6-3. Gl@v!ne to give up two more runs, but gets through five with a lead.

The Diamond Dave Game. Fourth place is just another word for nothing left to lose. Hence, with nothing left to lose, the Mets called up David Wright, their best position player prospect, in July. They did so despite their stated resistance to touching 21-year-old diamonds in the rough until a long stretch at Triple-A and even though they already employed the relentlessly adequate Ty Wigginton to play third. But Dave’s more diamond than rough, so Wright is installed at the hot corner immediately, triggering Wiggy’s goodbye and beginning what Mets fans could only hope would become an eternity. One month into his big league career, Diamond Dave sparkles in San Francisco. He collects four hits, three of them doubles, all of them leading off an inning.

The Goodness Gracious Game. When Barry Bonds pulled into third on one his visits to various bases, Diamond Dave tells him, “I’m not trying to jump on the bandwagon, but you’re as good as advertised. What you do is amazing.” Bonds, surprisingly, does not grunt. He smiles and replies, “Thank you. Keep swinging it.” David Wright extracts a moment of graciousness from Barry Bonds. For Diamond Dave, this must be just like living in Paradise.

The Kept Swinging It Game. The Mets and Giants combine for 20 runs and 32 hits.

The Kept Grounding Out Game. The Mets grounded into six double plays. The Giants grounded into three. Too many DP records were set or tied to happily enumerate.

The First Hit Game. Jeff Keppinger is in the process of trying to make a name for himself, and maybe put a statistic or two next to it. He came over with Kris Benson in the Ty Wigginton trade — or Ty Wigginton was sent away in the Kris Benson trade. How about they were both incidental in the Jeff Keppinger trade? Keppie comes on in a seventh-inning double-switch and smacks his first big league hit in the eighth. His first at-bat was the night before. He is now a lifetime .500 hitter.

The Wilson Delgado Game. With Kaz Matsui and Jose Reyes literally falling all over themselves until they could no longer play, the Mets recalled Wilson Delgado from Norfolk. Good thing somebody recalled him because it was easy enough to completely forgot who he was. Delgado’s a journeyman infielder — the Mets are his sixth team in a nine-year career that had generated fewer than 500 at-bats and left him with a face that resembles a frequently folded road map. He became New York’s in exchange for Roger Cedeño 2.0 at the end of spring training 2004. The Mets would have taken the proverbial bag of balls for Roger Cedeño…or a utility infielder who’d been everywhere, man. Ol’ Roger is filling in for St. Louis, hitting around .300 as the Cardinals are frolicking through the N.L. Central, natch. The fourth-place Mets have Wilson Delgado playing shortstop every day. And forgettable Wilson Delgado gets three hits against the Giants.

The Cursed Resilience Game. The Mets are up 7-5 in the top of the sixth; the Giants tie it at 7 in the bottom of the sixth. The Mets are up 8-7 in the eighth; the Giants tie it at 8 in the bottom of the eighth. The Mets are up 9-8 in the tenth; the Giants tie it at 9 in the bottom in the tenth. Playing in San Francisco, it is only logical to assume this game would get tied well into infinity, proving everything George Carlin ever said about baseball true.

The Busy Bullpen Game. Neither Gl@v!ne nor San Fran starter Brett Tomko make it past five. The Mets use six relievers, the Giants six, too. There is some nifty bullpen work, including an unheard of three innings from Mets closer Braden Looper (he even bats) and an honorable frame from the justifiably reviled Mike Stanton. Twenty-year veteran John Franco is the only Met reliever not to pitch, presumably because Art Howe thought anybody who’s been pitching for 20 years must have already come into this game.

The Unlikely Source Game. Jason Phillips came out of nowhere (technically Norfolk) in 2003 and hit .300 most of the year. He was a catcher who wound up playing a credible first. He was viewed as part of a Piazza-Phillips, C-1B platoon for ’04. Thus entrusted, Phillips promptly went into the tank. He drove in a run in the Mets’ romp over the Phillies on July 7 (the game that initially, tantalizingly snuck us one out of first) and did no such thing again until August 21. Now, suddenly, Jason singles home Wright in the sixth and the tenth. Two ribbies, no waiting.

The Everybody Plays Game. The Mets use their entire bench, which with Wilson Delgado starting at short, is no great shakes to begin with. The Giants still have J.T. Snow lurking, but otherwise are already all hands on deck. Howe says later Steve Trachsel might have pinch-hit (per Carlin, baseball has no time limit: we don’t know when it’s gonna end).

The Barry Bonds Game. Oh yeah, Barry Bonds. What does arguably the greatest hitter in baseball history, however he got to be that way, do? Only just about everything. He comes to bat six times. He singles. He doubles. He doubles again. He triples. He walks. And walks again. He is on base six times. That’s an OPS of astronomical. One of his doubles just misses going out, so he doesn’t homer to add to his lifetime total of 692 of those. Actually, he drives in only one run, testament to his not coming up with men on base all that often (he does score three runs). The other thing he doesn’t get is a free pass. How is it possible that in a game that sees his team gather 15 hits and 9 walks (6 from Gl@v!ne), that Art Howe doesn’t just put arguably the greatest hitter who ever touched wood on like everybody else does? Either Howe is brave or crazy…or no open base presents itself. Still, it is breathtaking to see Barry Bonds come up six times, see Barry Bonds be pitched to six times and live to tell about it.

The Sunshine Game. Remember Ol’ Sol? He is still front and center in the 12th inning when the Mets came up and the score was tied at 9. The Fox cameras focus on the shadows around home plate. The Mets radio announcers (this is too good a game to trust to the TV yammerers) note how difficult it is to see out there. It is against this atmospheric backdrop that the Mets step into face Kevin Correia, who entered in the tenth with no discernible backup. Wright unloads a double that bounces over the centerfield wall. Vance Wilson, who had run for Jason Phillips, is hit. Trusty Wilson Delgado sacrifices them over and is safe at first. Bases loaded, nobody out, the hot Jeff Keppinger coming up. All we need is fly ball or even a well-placed grounder to take the lead. Keppie, of course, bounces one to Pedro Feliz at first, who steps on the bag and throws home in time to get Wright. The sixth double play, the deadliest twin-killing. Two outs. Now what? The last guy on the bench, Gerald Williams, another emergency Met, walks, loading the bases. Todd Zeile steps in and lifts a lazy fly ball to deep right, for the thir…HE DROPPED IT! Dustan Mohr, squinting and groping, gets to Zeile’s ball but if flicks off his glove. Wilson (Vance) and Wilson (Delgado) scamper home. Zeile, not content to be an accidental hero, gets tagged out between first and second.

The Good Fortunato Game. With Franco in post-DL mothballs, Howe brings in Bartolome Fortunato. Another throw-in. He came from Tampa Bay with Victor Zambrano. Nobody expected to see him on the big club, let alone in a save situation so soon. Due up are Ray Durham, Deivi Cruz and Marquis Grissom. If any of them gets on — and Cruz already has three hits — Barry Bonds will come up, one homer short of a cycle. Who doubts that Barry Bonds would end it or extend it? Bartolome Fortunato does, that’s who. He strikes out Durham. Cruz singles for his fourth hit, but Grissom grounds to Delgado who tosses the ball to Keppinger at second who fires it to Zeile at first. Six-four-three. GAME OVER (eat your heart out, Eric Gagne). Mets 11. Giants 9. Bonds permanently on deck.

The Sic Transit Game. Barry Bonds is pitched to in the first inning the next afternoon. He swats No. 35 on the year, No. 693 on the career. The Mets lose. They come home and get swept four by the Padres. They win one against the Dodgers, then lose their next eleven. Splashdown Cliff, Diamond Dave, Ancient Delgado, Battling Braden, Toothless T#m, Lucky Fortunato, Keppie the Keeper…who knows what the future holds for them as 2004 winds down? But they all know they played one to remember in August — even if no one much remembers it enough by September to readily identify it for the classic it was.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On August 17, 1975, what Mets fans recognized as the longtime top of their rotation slotted snugly into one single box score. Tom Seaver went 7⅓ innings this Sunday at Shea, allowing only three hits but four walks. It — and maybe his singling and scoring in the fifth — took enough of a toll on Tom Terrific that he knew he’d be best off not attempting to rack up his 14th complete game of the season despite holding a 3-0 lead five outs short of his 17th win. When manager Roy McMillan came to the mound after two Giants reached base in the eighth, “I told Roy I was just too tired,” Seaver said. “I’d rather be a smart pitcher, leaving with a 3-0 lead, than give up a couple of hits and only be leading 3-2 or something. I was honest with Gil Hodges. I was honest with Yogi Berra and I’m honest with Roy McMillan.”

McMillan, having taken over for Berra less than two weeks earlier, honestly knew he didn’t have a surefire fireman to whom to turn to protect a somewhat tenuous lead, so he went to another starter instead. Well, not just any starter, but the second-best starter in Mets history behind Seaver. He called on Jerry Koosman, lately struggling in his traditional role. “I’d lost my confidence,” Kooz admitted. “You have to be cocky to show it on the pitcher’s mound. But my mental attitude is good now, although I’ve had some bad games.” McMillan saw the reassignment as an opportunity for his tenured lefty to “get his stuff back”.

So he did. Koosman got groundouts from Von Joshua and Derrel Thomas to pull the Mets from their eighth-inning jam and then pitched a scoreless ninth to preserve the 3-0 victory that brought the team within 3½ games of first, the closest they’d been to top of the N.L. East in two months. Seaver got the win, Koosman the save — the second of his career (the first came in extra innings, in 1972) and the only one he ever recorded as a Seaver reliever. After nailing down the final out for Jon Matlack in Houston two nights later, McMillan returned Jerry to the rotation. Whatever was bothering him before wouldn’t bother him the rest of the year. Koosman went 4-2 with a 2.50 ERA over his final eight starts. But by stopping by the bullpen to close, Kooz became the third pitcher of four in Mets history to save a game and steal a base in the same season.

GAME 122: August 19, 2006 — METS 7 Rockies 4

(Mets All-Time Game 122 Record: 23-25; Mets 2006 Record: 74-48)

The ghosts of 1986 were in perfect alignment with the ongoing runaway of 2006 as Mets management saw fit to bring arguably its two most dominant teams together at Shea for one Saturday night.

It wasn’t some kind of computerized showdown played out on DiamondVision or a Fantasy Camp preunion of Mets legends and legends to be. Rather, the Mets were celebrating the 20th anniversary of their most recent world championship — and the current team honored its predecessors by going out and playing a lot like them.

Were Mets fans in 2006 absolutely aching for another 1986? The attendance of better than 55,000 indicated the enduring affection they held for their last best team, though their fervor was probably just as stoked by a chance to watch the contemporary Mets try to match the ’86ers’ ultimate destination. At a juncture when two decades earlier the Mets had built a lead of almost 20 games over the rest of the National League East, the ’06 edition was maintaining a damn fine facsimile of that bulging margin, sitting out in front of the division by 14 games. It may have been standard commemorative arithmetic that initially linked the 2006 schedule to a series of 1986-themed promotions, but the success of the 2006 team made this veritable Old Timers Night a spectacularly appropriate and festive event.

Talk about synergy like it oughta be.

Ray Knight claimed another engagement. Lee Mazzilli and Roger McDowell were coaching Met rivals. Doc Gooden was most unfortunately otherwise detained. But every other Met player who was part of the 1986 postseason showed up. They didn’t just materialize; per their pedigree, they made an entrance, high-fiving lucky fans in their midst and cementing their connection to eternity in retirement just as they had via 108 wins, a National League pennant and a World Series back when they routinely entered the field through the first base dugout.

Their throwback parade started as a trickle. Then, one by one, through sporadic raindrops and Field Level boxes, they began to pour on the nostalgia in earnest. The damp August night lit up like a Christmas tree. On Niemann! On Elster! On Teufel and HoJo and Hearn! On Wally and Lenny and Danny and Aggie! Make room for Ronnie and Bobby and El Sid, too! The affection expressed in both directions — players to fans and fans to players — was enduring and palpable.

And then out came the 2006 Mets wearing 1986-style racing stripe uniforms. They were, tailoring aside, an excellent fit.

Journeyman callup Dave Williams channeled the fill-in yeomanry of Rick Anderson on the mound. Lastings Milledge played the role of cocky rookie outfielder Kevin Mitchell to a tee. And as the Mets did 39 times in 1986, the 2006 Mets stormed from behind to capture a lead they wouldn’t surrender. Colorado, an opponent not yet born twenty summers earlier, saw a 4-0 edge dissipate in the sixth inning when the Mets took advantage of two Rockie errors and three consecutive walks to plate a half-dozen runs. In the middle of that rally, Carlos Beltran recorded his 100th RBI of 2006 — or more than any Met but one (Gary Carter) put on the board in 1986.

Milledge, who took a little grief now and then for displaying the kind of freshman flashiness that you figure would have blended right into the ’86 Met milieu, added a homer in the eighth to give himself a 3-for-3 night and create a 7-4 final. Earlier in the season, Lastings high-fived fans down the right field line after hitting his first major league home run. His spontaneous, exuberant interaction was tut-tutted to within an inch of its life, yet given the way Met alumni streamed through the stands en route to taking their bows, he might have been more comfortable as an old-timer than he was trying to shake off the modern showboat label that had been stuck on him ever since the overblown incident overwhelmed talk radio in June.

Differences in uptightness notwithstanding, no Met year after 1986 felt more like 1986 than the Met year of 2006. It may have veered off that charmed course later, but the timing of the Mets fully acknowledging, at last, their spicy and successful past seemed like more than a coincidence of the calendar. The ’86 Mets enjoyed a seven-month roll. The ’06 Mets were in the fifth month of theirs. One edition taking bows as the other was taking names was as appropriate as it gets.

Mookie. Delgado. Mex. Wright. Kid. Reyes. Straw. Lo Duca. The Rockies never stood a chance.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On August 19, 1989, as it did so often when things were going well for the club, Met pitching dictated the terms of engagement. And things were definitely going well in Metland. Bobby Ojeda, Don Aase and Randy Myers combined on a five-hitter as the Mets defeated the Dodgers at Shea, 4-1. The Saturday night special capped a stretch in which the Mets won 15 of 19 and allowed three or fewer runs in 13 of the 15 victories. Ojeda himself was 4-0 over this span, posting a stingy 1.74 ERA.

Surprisingly, the Mets were dominating from the mound while Dwight Gooden sat on the DL with a sore shoulder and with losses in three of the four games started by Gooden’s high-profile replacement, Frank Viola. Despite Viola’s Sweet Music eliciting little run support from his new teammates (the Mets totaled three runs in those three defeats), the pride of East Meadow, L.I., helped stabilize a rotation that, in turn, spun the Mets in a positive direction. They were seven games out when Viola arrived from Minnesota at the July 31 trade deadline in exchange for five presumably lesser pitchers; after Ojeda’s strong outing against L.A., they trailed first-place Chicago by only 2½ games. (Aase, alas, would blow a ninth-inning lead the next day, giving up Willie Randolph’s first home run of the year, and the Mets’ 1989 momentum stalled, sputtered and slipped away from there.)

GAME 123: September 2, 1972 — Mets 11 ASTROS 8

(Mets All-Time Game 123 Record: 25-23; Mets 1972 Record: 64-59)

If there’s a statistically verifiable outer limit for not giving up on the Mets in a single game, this Saturday night in the Astrodome proved it was eight runs. If the Mets are down nine, there is no evidence they can come back. But if they’re down eight, have faith.

It worked once.

To best understand the game that encompassed the largest comeback in New York Mets history, it may be best to consider it as two games: less a doubleheader than one game with a split personality.

The first was unappealing, unattractive and unwatchable from a Met perspective. It featured the efforts of two pitchers with little Met past and essentially no Met future. Brent Strom, 24, was making his fourth major league start, attempting to earn his first major league win. The 24-year-old lefty wasn’t getting it here. A Lee May two-run homer put him in a hole in the first and a Cesar Cedeño two-run double knocked him out in the third.

Strom was replaced by veteran southpaw Ray Sadecki who gave up only an unearned run to keep the Mets within shouting distance of the ’Stros at 5-0, but their chances were reduced to a whisper when Bob Rauch entered. Rauch was a 23-year-old rookie righty appearing in his eleventh big league game. His previous ten outings came in Met losses, and this one didn’t appear destined to be anything different — certainly not once young Bob got his hands on it. Tommy Helms doubled home a run off Rauch in the sixth and Bob Watson singled in two more in the seventh. The Mets trailed 8-0.

So much for Bob Rauch’s chance of pitching in a Met win.

On the flip side, Don Wilson was enjoying an easy night’s work for the Astros. He had scattered four hits in seven innings and erased two of those on double plays. The Mets, who had lost to the same team by the same score the night before, were a feeble-hitting bunch as the grind of injury-wracked 1972 took its toll on their once-promising season. They would finish the year with a collective league-worst .225 batting average — and it didn’t appear they had chosen the notoriously stingy Astrodome as the place to make an offensive stand.

At least not until the eighth they didn’t. That’s when the first Mets-Astros game ended and the second, more appealing one began.

To say it began innocently enough would be obvious. When you’re down 0-8, anything that isn’t a nine-run homer is fairly innocent. Thus, Duffy Dyer’s leadoff single didn’t seem likely to hurt any fly that could survive the Dome’s hermetically sealed environs. Buddy Harrelson followed with another single, the first time all night the Mets had put two baserunners on in the same inning. Still very innocent.

Rauch was due to bat next, but that wasn’t happening. Yogi Berra tabbed Dave Marshall as his pinch-hitter, and Marshall walked to load the bases with nobody out. It was technically a jam for Wilson, but how tight could it be if he was pitching with an eight-run lead?

Tommie Agee came up and lifted a fly to right, caught by Jimmy Wynn but traveling deep enough for Dyer to tag up and score and for Harrelson to move to third. Astro skipper Leo Durocher (in his post-Cubs managerial twilight) would gladly trade an out for a run at that point.

But he probably wasn’t too gladdened when the next Met, Ken Boswell, whacked Wilson’s next — and last — pitch over the fence for a three-run homer. That pulled the Mets to within 8-4 with one out. Out went Wilson and in for the ungladdened Durocher came Fred Gladding. Gladding’s mission wasn’t all that complicated: Control the Mets’ burgeoning ambitions by getting five outs without giving up another four runs.

But now the Mets had a taste for scoring and they seemed to like it enough to want more. John Milner singled. Ed Kranepool singled. Cleon Jones doubled in Milner to make it 8-5, as lead-footed Eddie hoofed it to third.

Durocher: Not gladdened. Not at all. Out went Gladding, in came Jim Ray to face Wayne Garrett, the ninth batter of the top of the eighth. Garrett singled in the two baserunners and don’t look now, but the Mets, behind 8-0 a few minutes earlier, were trailing 8-7.

This second game was pretty darn good.

Dyer batted for the second time in the inning and singled for the second time. Ray, however, straightened out at last, retiring Harrelson on a foul pop and Marshall — still technically pinch-hitting for Rauch — on a foul to right.

While the Mets take the field to try and hold the Astros at eight runs, ponder Dave Marshall’s role for a moment. He pinch-hit for the pitcher and batted once more in the same inning. It was as if the Mets right then and there invented the designated hitter rule and some American League scout saw it, liked it and reported it back to the home office. One year later, the DH was junior circuit law.

Yet before you take out your purist-loving hostilities on Mr. Marshall, a Met bench staple with the rotten timing to have arrived just after 1969 and depart just before 1973, know that what he did it in the eighth wasn’t unprecedented in Met annals — though it was and remains pretty rare.

According to Baseball Reference’s Play Index tool, Marshall was one of seven Met pinch-hitters to bat for the pitcher and come up twice in the same inning without remaining in the game thereafter for defense. The first time it happened was exactly one week earlier when the pinch-hitter was Jim Fregosi and the pitcher was human rabbit’s foot Bob Rauch. The Mets scored five against Atlanta in that inning to take the lead but lost when Sadecki gave up a three-run homer to Mike Lum.

After it happened twice in a one-week span, it wouldn’t happen again for another nine years. On May 5, 1981, Mike Cubbage joined a hopeless mission already in progress: the bottom of the ninth at Shea with the Mets trailing the Giants 9-0. Future interim manager Mike walked as the offensive replacement for Jeff Reardon with one on and one out, and nine batters later found himself up again as the potential winning run, the Mets having narrowed the gap to 9-7. Cubbage, however, flied out to end the inning and the game.

Others who were de facto designated hitters for the Mets in National League competition: Howard Johnson versus the Astros in 1985, Gregg Jefferies against the Pirates in 1991, Vance Wilson in a game with the Cardinals in 2003 and Daniel Murphy this past April in Philadelphia. HoJo and Jefferies were the only DF DHs in this bunch to help their team to victory. None of them reached base twice. Wilson made two outs but reached once on a strikeout that got away. Fregosi made two outs and didn’t reach at all. Everybody else walked once, except for Murph, whose single accounted for the only hit (and RBI) in the fourteen plate appearances in question.

Some DHs.

Special mention is merited for Boswell in this context. He batted for Dyer leading off a ninth inning at Candlestick on May 29, 1973, and walked. Harrelson followed him with a single. Since the Mets trailed only 2-1, Berra stuck with his pitcher, Tom Seaver, to bunt. Being Tom Seaver, he not only successfully sacrificed the runners but beat out the play at first. The Mets went on to score four runs, with Ken batting in Duffy’s place a second time in the same inning. Then Seaver went out and retired the Giants 1-2-3 to win the game 5-2. So the pitcher didn’t have a designated hitter but the catcher did.

Now back to Houston, where the Mets just scored seven runs to turn an 8-0 Astro laugher into a potential Durocherian nightmare — a 1969 Cubs in miniature, you might say.

Yogi went with Jerry Koosman to keep the Mets close in the bottom of the eighth. Kooz yielded mixed results. He hit Helms to lead off the bottom of the eighth, got two outs but then allowed an infield single to Roger Metzger. With two on and so steep a mountain already scaled, Yogi didn’t want to tumble back down, so he replaced Koosman with relief ace Tug McGraw (his fourth lefty of the game). The switch worked as Tug struck out the dynamo Cedeño, a .340 batter, looking to get the Mets to the ninth still just one run down.

The Mets’ last chance began with Agee facing Jim Ray. Tommie prevailed by walking. Boswell singled, signaling the end of Ray’s night. Tom Griffin was Durocher’s choice to take on Milner. The Hammer bunted to the third baseman Doug Rader, soon to be awarded the third of an eventual five Gold Gloves for fielding prowess. But because it was just one of those evenings, Rader turned a sacrifice into an E-5. When the Dome dust settled, Agee scampered home with the tying run as Boswell raced for third and Milner for second.

Yes, tie game. 8-8. Not long ago it was 8-0. Funny game — or games — this baseball.

While Durocher’s legendary good humor was tested, he saw fit to order Griffin to walk Kranepool to load the bases. It was a desperation move that didn’t work all too well. Jones singled in Boswell and Milner and the Mets led 10-8. The only Astro solace was provided by Kranepool’s attempt to lumber into third. Eddie’s ambition backfired when Cedeño threw him out. But Jones took second, and Griffin’s wild pitch sent him to third. From there it was an easy ninety feet to trot when Garrett singled.

The Mets led 11-8. They overcame an eight-run lead and scored eleven unanswered runs. There’d be nothing else of note to put on the board from there — the Mets would leave the bases loaded after one more Durocher pitching change and Tug would mow down the Astros in the bottom of the ninth.

But what else did there have to be?

It was an anomaly, an aberration, an Amazin’ Astrodome ascent from the dead. It still is. It’s a comeback unmatched across a half-century of Met baseball, its phenomenal nature undiminished by its relative obscurity as a Met landmark. Except for a line in the media guide that is dug up when the Mets once in a great while delete a six- or seven-run deficit, it’s never discussed in detail by even knowledgeable Met broadcasters.

Why? Who knows? Maybe it’s because there was nothing otherwise heroic about the 1972 season once the continually achy Mets filmed their pilot for M*A*S*H. Maybe because there was no thundering climax in the vein of Mike Piazza’s three-run homer that capped a more concentrated comeback of proportions almost as epic in 2000. Maybe it’s because the heroes of the game all sparked more memorable drama in ’69 or ’73 or both. Marshall didn’t, but his participation here was mostly trivial (and then only because somebody bothered to detect it was anything at all).

The only other names you could attach exclusively to this particular, one-of-a-kind victory were really from the first part of it when it was a defeat.

Brent Strom and Bob Rauch never appeared in another Mets game as sensational as this one…unless you count the last Mets game in which both men appeared. They, like all the Mets, showed up on the wrong end of Expo Bill Stoneman’s 7-0 no-hitter at Jarry Park on October 2. Soon enough, Strom would be shipped to Cleveland for reliever Phil Hennigan. Brent enjoyed a couple of decent seasons in San Diego down the line before an elbow injury curtailed his major league status for good in 1977. He’d hang on in the minors until 1981, quitting pitching when he was 33. He’d transition into coaching at the minor league level, still instructing kid Cardinals to this day — and you, too, can benefit from his knowledge via the Strom Baseball Institute.

Rauch? Sent to Cleveland in the same deal. Never saw “The Show” again. Never even got a baseball card: not as a Met, not as an Indian, not as a Tucson Toro, the last uniform he wore as a player, in 1975. His professional career was over at 26.

The Mets were a 3-8 club in games Brent Strom pitched for them in 1972. When Bob Rauch took the mound, they went 3-16. Yet they were, perversely, part of the largest comeback in Mets history…an integral part.

As their manager might have said, it was their pitching made that night necessary.

ALSO QUITE HAPPY: On August 21, 1979, the Mets and Astros played a game that wouldn’t quite end, but not in the way the 16-inning pennant clincher in 1986 or the 24-inning 1-0 marathon at the Astrodome wouldn’t end. This Tuesday night at Shea had no problem arriving at the finish line.

It just had a dickens of a time figuring out how to cross it.

First attempt: Mets lead 5-0 in the ninth. There are two outs. Pete Falcone flies Jeffrey Leonard to center to end it. But this seemingly innocuous result is invalidated when it is realized shortstop Frank Taveras had called time to allow right fielder Dan Norman to pick up a stray ball in foul territory and third base ump Doug Harvey had granted it.

Falcone would have to pitch again.

Second attempt: Leonard uses his new life to single to left to keep Houston’s faint hopes alive. Except the Mets didn’t have nine men in the field. First baseman Ed Kranepool, having taken Lee Mazzilli’s putout from just after Taveras called time as gospel, made like a banana and split for the Mets’ clubhouse on the presumed third out. The Mets were thus playing without a first baseman. Manager Joe Torre contended Leonard’s hit shouldn’t count because the Mets weren’t fully represented between the lines. The umps agree and tell Leonard to get back to the plate and Falcone to throw again…once Krane rushes to his position from wherever it is Ed couldn’t wait to get to a minute before. Leonard flies to Joel Youngblood in left to again seal the 5-0 win for Falcone.

Not so fast there, Mets.

The Astros filed a protest, insisting it wasn’t their fault the Mets hadn’t heard about having nine men on the field at one time, therefore the swing that produced Leonard’s hit — the one he got between flying out twice — is the swing that should take precedence. N.L. President Chub Feeney agreed and declared the game was still in progress. Only hitch was by the time he ruled, everybody had pulled a Kranepool, so to speak, and had left the field. This was an hour after the game seemed to be over, so Feeney told the Mets and Astros their contest had been suspended at 5-0, top of the ninth, two outs, Leonard on first. They could pick it up Wednesday afternoon prior to the regularly scheduled series finale.

And so they did. The third attempt to end the unendable ninth was left to Wednesday starter Kevin Kobel (so much for Falcone’s complete game shutout), who grounded out the next Astro batter, Jose Cruz. Nobody called time. Nobody left the field prematurely. Despite Torre filing his own protest — “It’s a shame that the sacred rules of baseball apply to everyone but a last-place club like us” —nobody kvetched too strenuously once resolution was reached. Doug Flynn tossed to Kranepool, Cruz was called out and the Mets finally won Tuesday night’s game on Wednesday afternoon, 5-0, before succumbing, 3-1, in the actual Wednesday matinee.

Lost in the confusion among the multiple last outs was that Tuesday night marked Jane Jarvis’s final turn as Shea Stadium organist after serving sixteen seasons as Flushing’s resident Queen of Melody. Hard to believe she wasn’t brought back Wednesday for an encore performance. The only thing this singularly bizarre game was missing was a coda of Schubert’s “Unfinished Symphony”.

by Jason Fry on 22 August 2011 11:31 pm Contrary to what you may glean from accounts of tonight’s game, some good things did happen in Philadelphia:

1. Ruben Tejada went two for three and crashed into the tarp to make a terrific running catch. Yes, this is the same Ruben Tejada who deserved half of an ugly error yesterday against the Brewers. I think he’ll be a good one, and you’ve got to be patient with the young guys.

2. Lucas Duda collected two hits and did not actually miss every ball smashed his way at first base by Phillie after Phillie after Phillie. Just most of them. I think he’ll be a good one, and you’ve got to be patient with the young guys.

3. Dillon Gee didn’t jerk his neck around hard enough to fracture a vertebra as balls were hit out of Citizens Bandbox during the worst outing of his career. I think he’ll be a good one, and you’ve got to be patient with the young guys.

4. Cliff Lee didn’t actually kill a Met with his deadly touch, icy stare or magical breath. Though he probably could have if he’d wanted to.

5. Angel Pagan didn’t have much of an at-bat after appearing late for his final at-bat, but he also neither barfed on the field nor soiled himself. Which is best — we’re dealing with enough jokes here.

6. Ryota Igarashi is a day closer to no longer being a Met.

7. Keith Hernandez was in one of his manic, merry moods, which was amusing at first and a desperately needed distraction later.

8. Terry Collins hasn’t freaked out at a player, reporter, trainer, the Phanatic, or anything else during this horrid stretch. Turning over buffet tables right now won’t help. Everybody’s trying, the team is just outclassed and hurt and tired.

9. Binghamton will soon get a Jose Reyes cameo. Which presumably means we get to return him to active duty soon after that.

10. The game eventually ended. The Mets lost the damn thing by a score of 10-0, but at least it was finally over.

by Jason Fry on 22 August 2011 1:45 am What’s happening to the Mets now is cruel, and hard to watch. But perhaps it’s not really unexpected.

Perhaps what was unexpected was the part we liked more — the walking on water, the withstanding injury after injury after injury, the playing scrappy, winning ball for so long. The recent run of misfortune feels like proof that the team finally took one blow too many. Maybe it was being stripped of Carlos Beltran, or Jose Reyes being hurt again, or the unexpected end of Daniel Murphy’s year. Or maybe it was just August, when good teams step on the gas and bad teams expire, and all those things are coincidental. Whatever the case, the Mets are frustrated and Terry Collins is frustrated and we’re frustrated too.

It hardly seems worth going over today’s game, but I’ll paint it with a few strokes for posterity: R.A. Dickey was very good, Yovani Gallardo was just as good, and then the Mets’ bullpen and defense caved in again. Manny Acosta had a tough Saturday, coming in to clean up Jason Isringhausen’s mess and being victimized by a couple of ground balls with eyes. Today was more of the same, with Ryan Braun hitting a pitch through the infield that he practically needed a shovel to get to. One would feel worse for Acosta except he’d walked the leadoff hitter just prior to that. Tim Byrdak came in, and got Prince Fielder to hit a grounder to Justin Turner — who made a not good but not terrible throw that Ruben Tejada let sail on by. Then Jason Isringhausen was horrible, his location way off for a second straight day, and an inning later Pedro Beato was horrible too, and the Mets were dead meat.

Oh, and now we go play the Phillies.

As Collins remarked afterwards, the shame of this descent is that it’s unraveling the Mets’ good work from earlier in the summer, threatening the good feeling surrounding the team. That’s certainly true. But maybe it, like a lot of other things, is more a lesson in being realistic.

There are Mets who have made strides this year, just as there are Mets who can prove something over the last month and change. Murphy, Tejada, Turner, Jonathon Niese, Dillon Gee and Beato can all claim to have raised their profile significantly. Angel Pagan, Dickey, Lucas Duda and Josh Thole can show us something by finishing strong. The Mets have some minor-league help on the way. The team’s financial picture could be clarified by spring. Even the much-derided dimensions of Citi Field will most likely be different. This is a different team than it was in 2010, and I think a better one. I think there’s reason to believe it will be different and better still in 2012. That’s not a failure; come November and December, I think we’ll see it and be hopeful.

But there’s still six weeks of baseball to play — and six weeks can be a long time for a demoralized, battered team. They, and we, risk losing our focus before this season is in the books.

by Greg Prince on 21 August 2011 4:37 am Stephanie and I spent Saturday with the Mets and with the Stems. The Mets are the Mets. The Stems are the opposite of the Mets, and they were embodied not by the victorious visiting Milwaukee Brewers but by two people who are the opposite of fans of the Mets.

Let’s call them Mr. and Mrs. Stem.

That doesn’t mean they’re Brewers fans or Phillies fans or, god forbid, something worse. They’re not Mets fans is the most accurate way to put it. It’s not a matter of preferring another team or rooting against the Mets. There’s just an antithetical relationship between them and the Mets as a concept. Thus, only one who is truly mad would endeavor to place the two parties in the same 42,000-seat room.

It so happens Stephanie and I are related to Mr. and Mrs. Stem. Mrs. Stem I’ve known since right around when I was born. She’s my sister. She married Mr. Stem almost thirty years ago. He’s my brother-in-law. They’re family…but they’re the Stems. I long ago understood and mostly accepted those facts. I don’t need my family to embrace the Mets. I have lots of people who will do that with me.

Still, there’s something strange to me that I’m so closely related to the Stems, yet they’re not particularly partial to the Mets. And the Stems are far too cognizant of my enmeshment with the Mets to steer fully clear of it. For example, take Mrs. Stem and her recurring comment and question since Citi Field opened in April 2009:

The comment: “I have to see the brick.”

The Stems gave us the brick — technically, a gift certificate for one — almost as soon as the Mets announced fans could commemorate themselves on the grounds outside the new ballpark. That’s the kind of thoughtful gesture the Stems have always made despite their antithetical positioning vis-à-vis the Mets. As the gesture reached fruition, I reported to Mrs. Stem what was etched onto the brick. I sent her pictures. I pointed out the replica I have at home. I described its positioning outside Citi Field as best I could. I didn’t really want a brick when Shea closed. I was grateful to have it when Citi opened.

Mrs. Stem was glad it worked out. “I have to see the brick,” she continued to mention in that way people have of really meaning to check out that new show that was cancelled three months ago.

The question: “How’s the food?”

As long as I can remember, no matter the occasion, the venue, the emotional overtones (business, pleasure, tragedy), Mrs. Stem wanted to know about the food.

What’d they give you? What’d they put out? They didn’t put out anything? That’s terrible! They should at least have given you a little something.

Mrs. Stem was vaguely aware that the Mets’ new ballpark was renowned for its food or its “food court”. She didn’t care about the seating angles that kept me from seeing left field. She wasn’t interested that there was no Mets memorabilia on display for a solid year. She never requested an evaluation of Pat Misch’s velocity. “How’s the food?” was the only question that ever came up.

Mr. Stem didn’t ask about the food. He tried it on his one visit, with his father and brother two years ago. He volunteered to wait out the line for Shake Shack (“overhyped”) for as many innings as he could on their behalf. For Mr. Stem, such a dreary assignment was better than watching baseball.

Whereas Mrs. Stem’s Mets-obliviousness is perfectly benign, Mr. Stem can’t help but leak hostility when the topic of the Mets floats by. Mr. Stem is fiercely opposed to them on a level that transcends what the rest of think of us as sports allegiances. It’s got nothing to do with liking this team and not liking that team.

Long ago if not so far away, Mr. Stem, who grew up in Flushing, was a Shea Stadium vendor. The experience did not endear him to baseball or, by natural extension, the Mets. By Mr. Stem’s reckoning, every game he ever worked meandered into endless extra innings; included a giveaway item with which menacing children attacked him; took place as part of an inevitable doubleheader; and dragged on before and/or after an infinite parade of banners.

Mr. Stem, despite his bedrock good nature and generally great humor, thoroughly and righteously detests baseball, yet in his own way he understands it keenly. He understands the Mets have woven into them a capacity to build you up, let you down and break your heart. He’s immune to its effects ever since he assumed his Shea post, but he recognizes what they will do to others.

Which he doesn’t particularly mind, but is thoughtful enough to occasionally warn me against. I can still hear his parting words as I dropped the Stems off at JFK before Game One of the 2000 World Series and they were leaving New York for Las Vegas the morning of the first Subway World Series in 44 years: “Don’t be too upset if they lose.” Then, without my asking, he put ten bucks on the Mets to win for me.

So those are the Stems. And I’m apparently one who is truly mad because I got it in me that it would be a fine thing to do to bring them to Citi Field as something of a belated anniversary/birthday outing (their anniversary is in May, his birthday is in June; I am methodical in my madness). They could witness the brick. They could sample the food. And — this was key — they didn’t have to pay a whit of attention or respect to that thing which obsesses me every night and day of my existence.

This was a brainstorm for me, or what qualifies as one in my brain. I picked a game in August that figured to have no resounding impact on a presumably disintegrated Met season. Mets-Brewers? Would I really mind not having all my attention fixed on the Mets and Brewers? There were no giveaways scheduled, so there’d be no flashbacks to Willie Mays Night or Bat Day or whatever promotions still haunt Mr. Stem decades after the fact (Mr. Stem has combined them into one hellacious evening of his souvenir stand barely withstanding a full-on projectile assault.) All in all, I thought this was something the Stems could enjoy without actually having to consider the baseball going on around them.

I was pleased with the idea, also, because it allowed me to test my theory that Citi Field was designed for people who aren’t baseball fans. And, in a dangerous nod to sentiment, I’d been wanting to share just a little bit of my obsession with those close to me who had otherwise rejected it. Well, not so much with Mr. Stem because he’d just as soon take a Louisville Slugger to the head than take in a ballgame, but more with Mrs. Stem. Mrs. Stem took me to my first two Mets wins. Never liked baseball but she took me anyway. She was in college then. What college kid wants to waste a Saturday with a little brother amid acres of obliviousness? I don’t know, but this one did it anyway.

There was a moment or two in the mid-2000s when Mrs. Stem proudly peppered a telephone conversation between us with words like “Pedro,” “Gl@v!ne” and “Omar”. This was when I was intermittently involved with Mets Weekly and I guess seeing your relative on TV is kind of cool. But there’s never been any retention of any Mets data for Mrs. Stem, or any noticeable residual affection for those Saturdays in 1974 and 1975 at Shea. But I remembered the act of her taking me there and I always wanted to touch it again. Never mind that the last game we took in at Shea, Fireworks Night 1998, was an epic, aesthetic disaster. Mrs. Stem is a fireworks freak, but was so overwhelmed by nine innings of public address system blare and whatever 50,000 souls were screaming about that she begged off from what was to her the main event. We bolted before the fireworks show ever started. (Plus John Franco blew a lead in the ninth, which sucked for everybody else in attendance.)

In September of 2008 I gave serious thought to inviting Mrs. Stem to one final Shea game — to the second-to-final Shea game. It would have been perfect to my thinking: a Saturday, just like those Saturdays when I was a kid. I counted up all the reasons it would be beautiful…then I counted the myriad counterreasons why she would have found it hellish: more noise, more crowds, more headaches and backaches, never mind the commute and never mind that there was zero chance either the significance of Shea’s closing or the Mets’ fighting for a playoff spot would mean anything at all to her. I never brought it up.

No, that was a stupid idea. This — August 2011, Milwaukee, an insistence that Mr. Stem could rail at whatever and whomever he liked and I wouldn’t mind, and that Mrs. Stem didn’t have to keep a scorecard, and it would feature a nice dinner in the Acela Club along with a veritable guided tour of the ballpark I don’t really love but I sure seem to know, starting with that brick…this was brilliant. Or so I decided.

They went for it, which kind of surprised me. I said you don’t have to, that we could take you to the movies or something else, but we captured their fancy just enough with the offer. It was almost as if they were touched we wanted to share this.

Almost.

Mr. Stem helpfully saved us a step and not a few bucks, peeling off his brother’s season tickets and parking pass for the day. I was thinking Excelsior because it more than any other section strikes me as detached from the game in progress, but Promenade Club Box would do nicely, and I wasn’t going to argue with us getting a ride from them. From there, though, it was our production.

We parked in Lot D, which I learned (because I’ve never driven to Citi Field) is the name of the lot where the Shea markers sit. I hustled over to third base to begin the tour. Stephanie — more of a Met maven than I’d ever dreamed she’d be — explained the significance: Shea Stadium, the bases, the field, the whole thing, right where we stand.

Mrs. Stem: That’s very nice.

Mr. Stem mock-kicks invisible dirt on third. “I earned that,” he said.

I led us to home plate. “Uh, you don’t have to show us every base,” I was told.

Next up, the brick. After 44 months, dating back to the presentation of the gift certificate, it was a little anticlimactic to show it off in its natural habitat. I’d already reported to Mrs. Stem what was etched onto the brick. I’d already sent her pictures. I’d already pointed out the replica I have at home. I’d already described its positioning outside Citi Field as best I could.

So there’s the brick.

Mrs. Stem: That’s very nice.

Mr. Stem: How many of these bricks say “Let’s Go Mets” on them anyway?

We went inside. There’d be stops in the museum (where I rediscovered Mrs. Stem had no idea who or what “Bill Buckner” was); peeks at various concessions (“What’s Mama’s of Corona?”); recountings of architectural details as I interpret them (Mrs. Stem wanted to know what the Shea Bridge did — “It gets you from here to there,” I said); and after pausing for the national anthem, we were up the escalator to our seats in 417 for baseball.

Which I wasn’t counting on. The last thing I intended to expose the Stems to was baseball. Seriously. I could watch baseball anytime with baseball fans. That wasn’t the mission here, not for nine innings it wasn’t. Mr. Stem’s wishful-thinking accelerated countdown of every out indicated the baseball at the baseball game — this Very Special Episode of a baseball game, that is — needed to be limited.

Luckily, I was on top of this. Two innings in, I got up and said OK, time for dinner. I had made reservations at the Acela Club for five o’clock, which was fast approaching. That would be the heart of our outing.

And it worked. Mr. and Mrs. Stem LOVED the Acela Club. They loved the food. They loved the air conditioning. They loved that it was situated above a baseball game yet required not even the feigning of acknowledgement that a baseball game was underway.

From the glimpses I took from our window seat (for which the Mets graciously apply a surcharge), it didn’t appear Chris Capuano was all that aware the game counted. So I wasn’t missing anything on the field. The Market Table awaited, the entrees were delivered, everybody was relaxed. There were many declarations from the Stems that this was the best baseball game they’d ever attended now that they could easily ignore the baseball game they were attending. Out in the stands, that would have gotten on my nerves. In the climate-controlled, plentifully portioned Acela Club…whatever.

We were good from the top of the third to the bottom of the seventh. If this was how the food was at Citi Field, there were no complaints from this crowd. We turned various shades of mellow (even as we wondered what the deal was with that fire they were showing on the monitor). A little well-meaning baseball talk filtered in and out. Mrs. Stem, grasping to put it all in perspective with one of those abrupt non-sequitur summations she tends to issue without warning, concluded, “This is a business of miracles.” l stared at her quizzically ’cause I didn’t know what the hell she was talking about. She said she was referring to the Mets…you know, the Miracle Mets. Yeah, sure, but at the time, the Mets were losing 7-1.

“If they come back to win, I’m using that as my headline,” I promised.

But I assumed they weren’t coming back to win, even as they finally began to assemble some baserunners as we left the Acela, even as they’d narrowed the gap to 7-3, then 7-4. I hoped for more but I wouldn’t get my hopes up. It was too distracting from my overall plan and, let’s face it, the Mets were still losing by several runs. But then, as we stood on the Excelsior level, Lucas Duda doubled in two more and suddenly we were down only one and I mentally returned to the baseball game.

Except I noticed Mrs. Stem held her hands over ears at the first legitimate explosion of noise all day. Ohmigod, I thought, it’s Fireworks Night 1998 all over again. So, calmly, I said let’s go — there’s a place over there called the Caesars Club where the noise won’t bother you.

No, I was assured, we could wait and see the conclusion of the bottom of the seventh as Jason Bay prepared to bat with the tying run on second. Besides, Mr. Stem predicted with not even a twinge of taunt or doubt — and without knowing Jason Bay from Thunder Bay — the Mets wouldn’t score anymore here.

And of course he was right. They build you up, they let you down, they break your heart. At least we got it out of the way.

I would have been satisfied with leaving after showing the Stems the Caesars Club (they were theoretically attracted to its comfort without quite understanding why something like it took up so much space at a ballpark) but Mr. Stem was trying his best to play ball, as it were. Let’s go back to our seats and watch the last two innings, he suggested.

But I had one more highlight on the tour as long as they were up for it: the Pepsi Porch. I figured it would give them a sweeping vista effect…and maybe we’d be able to see if that fire was still smoldering. We arrived up there in the top of the eighth just as Francisco Rodriguez was being announced into the game for the Brewers. I wasn’t surprised but a little put off by how heavily booed he was. I got that he was in the other uniform, but the guy held up his end of the bargain for the duration of his Met 2011. I applauded him, maybe out of habit, maybe out of sympathy.

Not that I particularly wanted him to succeed as I found a railing to lean against. What I wanted didn’t matter, however. K-Rod retired Paulino and Pridie and went to oh-and-two on Tejada. This is too bad, I said to Stephanie when she joined me. Mr. and Mrs. Stem were milling about somewhere, so as long as we were up there, we might as well watch Frankie throw ball one to Ruben. Then balls two, three and four. We had a baserunner.

Josh Thole was announced as the pinch-hitter and I allowed hope to take root again. “He caught Rodriguez,” I told Stephanie. “How can he not know exactly what he throws?” My (and Terry Collins’s) theory was right on the money. Josh ripped one to deep center and from the Porch it was clear Jerry Hairston, Jr., might catch it but probably wouldn’t.

He didn’t. We were tied.

I had no sympathy any longer for Francisco Rodriguez. He was just another Brewer now and all I wanted was for Angel Pagan to grill him the way the Acela chef grilled my salmon — exquisitely.

K-Rod had two quick strikes on Pagan, but Angel knew something. I could feel it. He was fouling them off, just missing. Frankie would melt. Frankie would too often melt. Why should he stop melting now just because he was no longer a Met?

And just like that, he melted. Pagan launched a fly ball that was coming right at us — not close enough for us to catch, mind you, but right at the Porch, just like he did last month in that Gary, Keith & Ron game.

It was…a homer! Angel Pagan homered! I literally jumped in the air. “I’ve never been happier” would be going a bit too far, but one doesn’t get as happy routinely as I got from Angel Pagan’s home run off Frankie Rodriguez and into the Pepsi Porch. It probably helped that Stephanie and I were standing on the Porch when its ascent and destination became thrillingly clear. It definitely helped that I had discounted the Mets in this game — that I had discounted the game altogether in deference to the good time I wanted to show the Stems, but now I had it all. We had our lovely dinner, we had our relaxation, we had our improbable comeback (just as Stephanie and I did after dining at the Acela last year) and I even had my headline, courtesy of Mrs. Stem.

“This is a business of miracles.”

I could see it, I could feel it, I was even reshuffling the standings for Game 125 of The Happiest Recap. How could this not be the best Game 125 the Mets had ever played? We were down 7-1 against a first-place club, we were dead again in 2011 and we sprung back to life as we had over and over in 2011. How was this not great?

Mr. Stem came over and mentioned the sun was bothering Mrs. Stem, can we go back to our seats soon?

Oh, right…them. Them and baseball. Them and the Steve Henderson home run 31 years ago when they were still dating and I was bouncing off the walls when the Mets converted a 6-0 deficit into a 7-6 victory and Mr. Stem throwing “who cares?” cold water on my teenage euphoria. Them and not being the least bit invested in the Mets’ 9-7 lead I was just jumping in the air about. The sun was a bit harsh. That was what they noticed.

Well, yeah. They’re the Stems.

On another day, this would have annoyed the spit out of me, stepping on my big Mets moment like that, but this wasn’t another day. It was the day I dedicated to showing them that good time, and I was surprisingly concerned with keeping that going to an unbitter end. I didn’t even wait for the final out of the eighth to say let’s go downstairs and watch the last three outs from behind some Field Level seats.

Though I was mentally kicking myself for assuming there’d be a last three outs accomplished so easily.

Mr. Stem knew better. Mr. Stem expressed a desire at day’s beginning for a quick 1-0 game but knew we’d get something like this because every game he ever had to be at went this way: the Mets would fall behind, the Mets would roar back, the Mets would give it all up, the Mets would not roar back again. Build you up, let you down, break your heart. He told me it was coming.

As if I couldn’t have calculated that for myself.

The first pitch Jason Isringhausen threw to Jonathan Lucroy to lead off the ninth was a ball. By no later than the fourth pitch, which raised the count to three-and-one, I knew he didn’t have it. Izzy looked so tired, so out of sorts. I tried to tell myself that he could find it, but I didn’t for a second believe it. Certainty that there’d be three quick outs crumbled into hope there’d be three outs without two runs. And hope didn’t stand a chance.

And if I wasn’t sure, Mr. Stem kept circling around to me to remind me that this is what they do. I have to stress he wasn’t taunting me personally and wasn’t taking any pleasure that I was presumably absorbing some pain. It was just that antithetical relationship to the Mets flaring up. He couldn’t help himself: the Stems and the Mets are natural adversaries. Mr. Stem knew who they were. He hadn’t voluntarily watched a pitch in decades, probably, but he knew. He knew and he was compelled to communicate it.

I am certain I didn’t need to hear it at that very moment, not with Izzy allergic to the strike zone, not with the bases getting loaded, not with Mark Kotsay walking to force in Lucroy to make it 9-8, not with nobody out, not with Collins coming out to bring in I had no idea who, not with Izzy being booed and me feeling like chiming in.

Still showing remarkable control, I calmly informed the Stems that we could go now, I’ve seen enough, I’m just running into the bathroom, I have my radio, I’ll listen to the end on the way to the car. It probably came as more melodramatic than I intended, but I meant it.

This was the inverse of the glorious Victor Diaz game of 2004, the one Diaz tied with a two-out, three-run homer in the ninth against LaTroy Hawkins of the Cubs, who were in a desperate playoff race with a week to go in the season. I was watching that one with a really wonderful, older Cubs fan who was still stinging from the Bartman incident a year earlier, and I had to leave as soon as that inning ended, even though extras were ahead. I had to go because I promised Stephanie I’d meet her in the city but really there was nothing left for me to do in that particular game. If the Cubs won in extra innings, I’d be miserable. If the Mets won in extra innings, I’d be jubilant, of course, but I’d feel really bad for the guy I was with. The circumstances were different against the Brewers, but the sense of “there’s nothing more I can do here” held, not with me trying to keep to my original intent of what the day was supposed to be.

It was supposed to be a pleasant day with family. It was supposed to be 7-1 Brewers. It was supposed to be the brick and the Acela. It wasn’t supposed to be me suppressing my instinct to be disgusted and dismayed, and not just from Jason Isringhausen. I didn’t want the lingering good vibes from dinner and from Pagan to be obliterated by whatever was about to happen. So I said let’s go, I’ll be right out of the bathroom.

Sixty seconds later, nobody had moved from where we were watching. Mr. Stem promised to put a cork in his Stemian impulses for the duration and implored us to stay through wherever the full nine innings took us (what a bizarro chain of events: I want to leave the Mets game and he wants to stay). Fine, I said.

Now it was in the hands of Manny Acosta — as if that was about to solve all our problems.

For a second, I believed. That second spanned Manny’s flying of Ryan Braun to right to Jason Pridie’s effective throw home. Maybe, just maybe Manny Acosta could…

No. He couldn’t. Prince Fielder tied the game on a ball Justin Turner couldn’t corral and Casey McGehee shot another one by him and it was 11-9 and there was no turning back from where this was going.