The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 16 December 2021 1:06 pm It’s been the year of Jacob deGrom so often for most of the past decade that you’d think it would be hard to discern when it isn’t the year of Jacob deGrom. Jacob deGrom was named by this blog as the Richie Ashburn Most Valuable Met of 2014, 2017 and 2018. Jacob deGrom wasn’t named the Richie Ashburn Most Valuable Met of 2015, 2019 and 2020, but had he been, it wouldn’t have been a strenuous stretch. Considering his body of work from 2014, when deGrom snagged the National League Rookie of the Year award, through 2020, when deGrom vied valiantly right up to the end of the truncated season for his third consecutive National League Cy Young award, co-naming the MVM for Ashburn and deGrom wouldn’t have lunged beyond the limits of appropriate designation had we gone in that direction. Jacob deGrom had been that good for that long.

This year, though, 2021…this was really the year of Jacob deGrom.

It was the year Jacob deGrom was not only better than every other player on the Mets and every other pitcher on any team and perhaps every other player in the majors, it was the year Jacob deGrom immersed himself in the process of redefining “best” Metwise. Jacob deGrom in 2021 might have ascended to the status of the best Met there ever was. Gathering steam in the April cold and continuing past Independence Day, I was close to convinced that no Met — none — had ever been better. Consider deGrom’s second, third and fourth starts of the season, which are as emblematic of his pitching as his erstwhile flowing locks used to be of his silhouette.

• April 10: 8 innings at home versus the Marlins; 5 hits, 0 walks, 1 earned run allowed; 14 strikeouts.

• April 17: 6 innings in a Coors Field doubleheader of 7 innings apiece in the Rocky Mountain cold; 3 hits, 1 walk, 0 earned runs allowed; 14 strikeouts.

• April 23: 9 innings back at Citi Field against the Nationals; 2 hits, 0 walks, 0 earned runs allowed; 15 strikeouts, after which his ERA measured 0.31…and his batting average was .545.

The only thing that kept deGrom’s 2021 from donning a red cape and leaping tall buildings in a single bound thereafter was uneasiness about allowing it to take flight unencumbered. Jacob pitched as many as seven innings only three times following his trilogy of aforementioned masterpieces and topped 90 pitches only once in the process. Abundances of caution rather than opposition batsmen were the main obstacles deGrom faced from April until July. There was a brief detour to the IL in May and a couple of starts that definitely would have gone longer had the most precious natural resource in Flushing not been thought at stake. Fine, fine — you don’t mess around with Jake, we all agreed.

Had Jacob deGrom traveled to Denver for the All-Star Game to which he had been sanely selected, I had ready to go, at least in my head, an essay daring to assert that the Met we were about to watch step forward from a foul line and tip a cap to represent us at the Midsummer Classic might as well also be acknowledging that he was a Met practically without peer. A “today I am the greatest of all time” Rickey Henderson-style greeting is not Jacob deGrom’s tempo, yet by the middle of 2021, there was Jacob deGrom and, I swear, there was nobody else keeping him ethereal Metsian company a figurative mile above sea level.

Except for Tom Seaver, of course, whose transcendence as a Met is and always will be peerless, yet whose peak performance over an extended period of time in a Met uniform might very well have been on the verge of a teeny bit of eclipse.

For consistent episodic brilliance, maybe it had already been overshadowed.

Caveats like crazy should be applied in deference to the differences in the sport a half-century apart, particularly how pitching is managed, but consider that entering 1970, Tom Seaver was well-established as the ace of his staff and, across the next two seasons, ’70 and ’71, went out and threw 577 innings, yielding an earned run average of 2.29; and from 2018 through his final start of 2021, Jacob deGrom, well-established ace of his staff, threw 581 innings and yielded an earned run average of 1.94.

Caveats! Two seasons for Seaver versus four for deGrom; 40 complete games from Seaver versus two from deGrom; strikeout incidence in general way up fifty years later (774 for deGrom, 572 for Seaver); shifts; velocities; bullpens…

Even still.

I grew up idolizing Tom Seaver, but even as a starry-eyed kid, I understood it was possible that Tom Seaver might now and then have a slightly subpar start, was capable of giving up a couple of runs at the wrong time, could once in a great while be outpitched. At a much more advanced stage of my life, I couldn’t think the same of Jacob deGrom. I knew he didn’t win as often as Tom Seaver, I knew he rarely stayed in games for as many innings as Tom Seaver routinely did, and I knew there was only one Tom Seaver. But I also knew there was only one Jacob deGrom, and in my fifty-plus years of hanging on every pitch every Met throws, I never felt as continually confident that a Met was going to throw strikes and get outs as I had come to feel about Jacob deGrom.

That’s how good Jacob deGrom had been almost without pause since he came to the big leagues in 2014, since he had elevated himself above the crowd in 2018, since he somehow soared even higher in 2021. The numbers would have to take care of themselves over time, but in the moment, in the midst of an individual’s career arc and season like none other I’d experienced as a Mets fan, I was ready to admit to myself and out loud that even if no Met could ever be greater than Tom Seaver, maybe no Met had ever been better than Jacob deGrom.

***But then it was no longer the year of Jacob deGrom.

His last start was on July 7. He wouldn’t be going to the All-Star Game on July 13. Despite our desire to display our jewel and remind the baseball world we had something nobody else could claim, his demurral made sense. Why waste energy on an exhibition? Rest up, Jakey. Be strong for the second half. With his recusal, my impetus to evaluate his stature diminished, so I held off.

After the All-Star break, Jacob deGrom’s next start was to be determined. His status was to be announced. His condition, inevitably, was to be confounding.

July 17: Jacob deGrom is experiencing tightness in his right forearm and has been shut down. An MRI didn’t show any structural damage.

July 18: Jacob deGrom goes on the 10-day injured list.

July 25: Jacob deGrom throws off a mound and is feeling good.

July 30: Jacob deGrom is shut down after additional inflammation is detected in his right elbow.

August 3: Jacob deGrom tells reporters his elbow inflammation is unrelated to his forearm tightness, adding he doesn’t believe he’ll miss the remainder of the season.

August 13: Jacob deGrom’s shutdown will continue at least two more weeks, according to Luis Rojas.

August 20: Jacob deGrom is transferred to the 60-day IL, retroactive to the middle of July, making room for the newly acquired Heath Hembree and implicitly acknowledging deGrom won’t be ready to come back until mid-September.

September 4: Jacob deGrom is reportedly 10 days away from beginning bullpen sessions after having played catch at a distance of 75 feet.

September 8: Jacob deGrom’s right UCL had the lowest-grade partial tear, according to Sandy Alderson, but the team now considers it “perfectly intact” after two months of not pitching.

September 9: Jacob deGrom releases a statement that pronounces his UCL “perfectly fine,” and indicates he will “continue to throw and build up and see where we end up,” even as it’s reported only “an outside chance” exists he will pitch again in 2021.

September 12: Jacob deGrom is scheduled to throw off a mound “maybe this week,” Rojas says.

September 26: Jacob deGrom reportedly might make one appearance before the season ends, given that a recent bullpen session went well.

***The season ended on October 3 without Jacob deGrom returning to the mound. His first half would stand as his whole: a 7-2 won-lost record (among the league leaders in winning percentage for a change); 146 strikeouts recorded in 92 innings; an ERA of 1.08, a legitimate challenge to Bob Gibson’s modern mark of 1.12 from 1968; and an ERA+ of 373, or 165 points better than his league-leading, relative-to-the-pack metric was during his phenomenal 2018. In 2021, deGrom faced batters 324 times. He concluded those opposition plate appearances 272 times by recording an out.

Yet Jacob deGrom couldn’t properly end his season.

Nor could the 2021 Mets, I suppose, but they did have to keep grinding. Somebody had to keep pitching, and somebody did. Several bodies in particular. In more than one of every three games, five pitchers each kept showing up, kept taking the ball and kept the Mets as competitive as they could have possibly been. Collectively, they were in our faces nearly daily and nightly, but their successes were easy to look past. It’s their less frequent failures that more readily grab our attention.

Hence, with deGrom sidelined through the second half, Faith and Fear in Flushing makes a call to the bullpen and chooses as its Richie Ashburn Most Valuable Met of 2021, Aaron Loup and the Oft-Used Troupe. Our winners are advised (as Corbin Burnes upon capturing the Cy Young should have been), to take a page from the winter 1976 night a self-aware Paul Simon won the Grammy for Best Album — “I’d like to thank Stevie Wonder, who didn’t make an album this year” — and send a note of gratitude to Jake for having ceased pitching on July 7.

To clarify, this year’s Ashburn goes primarily to Aaron Loup, who appeared on a Mets mound 65 times and recorded an ERA lower than deGrom’s, but with ample space on the plaque for his band of bullpen brothers who, like him, pitched in well over one-third of all Mets games in the past year: Miguel Castro (69 appearances), Trevor May (68), Jeurys Familia (65) and Edwin Diaz (63). Loup is the headliner here, but his comrades are also worthy of commendation. They worked through adversity, they persevered often against popular opinion, they handled multiple roles as asked and they did quite a bit of coming through.

In a day and age when every relief pitcher is considered by management a fungible token, ready to be exchanged at a moment’s notice for whoever else has options or happens to be spotted on a waiver wire, these five were relied upon as individuals from season’s start to the season’s end. Only Familia served a standard IL stint, and he returned within two weeks. Castro spent a couple of days in COVID protocol and then was back. Diaz took a couple of days to celebrate the birth of his second son. Loup and May were the only two Mets to never leave the active roster.

The Mets played 162 games. In 143 games, one to five of these relievers who pitched between 63 and 69 times were part of the box score. Sly Stone would have dubbed them everyday people. The Mets were a winning team when we saw one or members of the Troupe in action, going 73-70. In only 19 games did none among Loup, Castro, May, Familia or Diaz appear. When all five members of the quintet cooled their limbs, the Mets’ record was 4-15.

On May 18, all five pitched (Castro opened). The Mets won.

On May 21, all five pitched (the game went 12 innings). The Mets won.

So why not just make the whole team out of these five? The 73-70 Mets with them involved were statistically better than the 77-85 Mets in toto. It’s understood team wins don’t exactly work that way; a clean seventh inning does not a victory make. Even from a bullpen perspective, more factors than “give the ball to one of these five” enter play. Days of rest inevitably come due. The threat of overuse — a symptom of the prevalence of the dreaded “up-down” in modern baseball parlance — becomes lodged in the organizational brain. Sometimes you’re not going to bring in a specific reliever or five if the game doesn’t fit their skill sets. That night in April when deGrom so thoroughly went the distance over the Nationals that the Nationals tweeted their admiration, you’d have incited a riot had you removed Jacob.

Your own starting pitcher’s excellence, however, isn’t usually the reason you don’t unleash your most trusted relief pitchers in this era. On August 15, the Mets trailed excellent starting pitcher Max Scherzer and the Dodgers, 9-4, in the eighth inning at Citi Field. Geoff Hartlieb was on in relief of, in order, Carlos Carrasco, Jake Reed and Yennsy Diaz. It was conceivable that if Hartlieb or somebody could hold the fort, maybe the Mets could mount a comeback on the Dodger pen, with Max having left after six. It may have been barely conceivable that these Mets could make up five runs on these Dodgers, but the game was not over.

It was getting close to over, however. In the top of the eighth off Hartlieb, there had been an infield single; a flyout; a walk; another flyout, which moved the first runner to third; a wild pitch, which moved the second runner to second; and…

“Now the three-oh — outside for ball four, and that loads ’em up for Will Smith, who has homered in every game of this series,” Howie Rose informed those of us who turned the sound down on ESPN that Sunday night. “Jeremy Hefner is gonna stroll out to the mound. Nobody throwing in the Mets’ bullpen, and I wonder if that’s an indication that if Hartlieb can’t finish…”

Howie checked his scorecard: “The only remaining pitchers out there are Loup, Diaz, Lugo, May, Familia and Castro…”

Only? As I heard that list of the Mets’ six most reliable relievers, any of whom figured as a better bet than Hartlieb at that moment, I also heard Principal Seymour Skinner reliving the trauma he brought home with him from Vietnam for Bart Simpson:

“I spent the next three years in a POW camp, forced to subsist on a thin stew made of fish, vegetables, prawns, coconut milk and four kinds of rice. I came close to madness trying to find it here in the States, but they just can’t get the spices right.”

Rojas, Hefner and whoever contributed to Met decisionmaking decided that rest for your best relievers outpointed the chance to stifle the Dodgers and give the Mets a chance to win a game they badly needed (they badly needed every game by mid-August). Thus, no fish, no vegetables, no prawns, because, as Howie explained after the briefest pause — when he, too, must’ve thought how strange it sounded to imply the Mets had no more relievers available to them despite having a half-dozen relievers who hadn’t been used that night — who it wouldn’t be ideal to “use in a game that’s right now nine to four, which could get even bigger in disparity, with the Dodgers having the bases loaded here and one out in the eighth inning. So could we be looking at a position player taking the mound for the Mets in the ninth inning? I wouldn’t rule it out.”

Hartlieb stayed on. He gave up a two-run single to Smith and an RBI double to Chris Taylor. In the ninth, trailing by eight runs, Brandon Drury came in, gave up two more runs, reloaded the bases and handed the ball to Kevin Pillar. The second position player got the Mets out of the inning. They’d lose, 14-4, and drop 2½ games behind Atlanta.

The Mets never did get the spices right, but at least the ingredients remained fairly fresh. That Sunday night game was a bracing reminder of how bewildered the Mets could get when they rested their best bets. No doubt it was tempting to ride Loup & Co. for all they were worth, but the Mets exercised restraint. None of their pitchers landed in the Top Ten in appearances in the NL, a far cry from the days of Perpetual Pedro Feliciano, Ubiquitous Aaron Heilman or Tick Tock Turk Wendell, three relievers who their managers didn’t mind going to like clockwork. None of the 2021 stalwarts posted a season that ranks within the Top Forty of most appearances in a season by a Mets reliever.

Although it seemed the Oft-Used Troupe — or OUT — was up and throwing all season long, their deployment was staggered so they didn’t stagger, even as the Mets’ rotation lost deGrom in the second half, Taijuan Walker lost his way in the second half and Marcus Stroman was the only starter who maintained his spot competently and consistently all year long. There were surely downs enmeshed with the ups, but each of those who composed OUT kept getting outs from early April until early October. It didn’t keep the Mets in first place and it didn’t get the Mets back to first place, but their composite presence in those 143 games seemed to make the Mets viable most middle and late innings, especially after Met starters couldn’t last as anticipated, frequently as Met hitters didn’t produce as desired.

***Loup, the only lefty in the Troupe, didn’t have the luxury of facing one batter and hitting the showers as his LOOGY predecessors did before rules were altered to speed up games (how did that work out?). If he started an inning, he needed to face at least three opponents. Not working as a specialist, Loup held righthanded batters to a .211 batting average in 109 ABs and lefthanded batters to a .167 batting average in 93 ABs. Mastery of this nature helps explain Aaron’s signature stat, his 0.95 ERA. That’s lower than deGrom’s in the year deGrom’s was lower than Gibson’s, never mind that deGrom threw about 35 innings more than Loup (and Gibson threw more than three times as many than deGrom). Reliever ERA only tells you so much, as does a stellar won-lost record — Loup’s was 6-0 — but it certainly tells you somebody was having a historic year if after 56.2 innings is that somebody wasn’t giving up as many as one earned run every nine innings.

A few Loup days and nights stand out in particular.

There was the Sunday afternoon in Pittsburgh in mid-July when Walker and Rojas melted down in tandem in the first inning, as the Pirates took a 6-0 lead after winning from way behind Saturday night. Suddenly it was a bullpen game and nobody penned a more satisfying pair of stanzas than Loup, as the Louisianan lefty retired the Buccos with a double play in the fifth and three consecutive Ks in the sixth, the latter coming with the bases loaded. The 0-6 hole eventually became a 7-6 victory.

There was the Saturday night as July ended when Loup entered with runners on first and third, two out and the Mets trailing the Reds by one. Loup didn’t retire a single batter in traditional fashion. Instead, he picked the runner off first, instigating a 1-3-5-2 out at the plate that cleaned up the mess Seth Lugo left him. It went into the books as one-third of an inning pitched, which one guesses it was, even if Loup’s only pitch of consequence was fired to Pete Alonso.

And there was the weeknight in late August that stands as something of an exception to the rule that Aaron Loup’s assortment of sinkers and cutters was infallible because, well, there’s always an exception to the rule and nobody’s infallible. Walker was having perhaps his best game of the second half, a half when he had few good games. Tai arrived in the seventh up 2-1 over the Giants. He’d allowed only one hit, a home run to Kris Bryant, over the first six, and one walk, to Alex Dickerson with two outs in the fourth, which he made moot by striking out Brandon Crawford immediately after. In the seventh, however, Bryant reached on an error, and Dickerson singled very softly. Crawford was up next. Walker had thrown 74 pitches. It was more Walker’s night than any night all season, and that includes the first half when he earned the right to replace deGrom on the All-Star roster.

Yet Rojas couldn’t resist taking him out and putting Loup in. Loup had reached favorite toy status with his manager. Every manager has one at some point in a season. And who wouldn’t want to play with a toy that works so well and brings so much joy? Aaron was uncommonly well-rested, having last pitched four days earlier. In the seven appearances leading up to this Giants game, he faced 18 batters and gave up only one hit. None of the seven runners he inherited scored. It wasn’t crazy to trust Aaron Loup in this situation more than Taijuan Walker or maybe anybody amid a first-and-second, nobody-out scenario.

Except somehow you knew it was the wrong call. And it was. Crawford, the lefty, lined a double to right, scoring both runners and giving the Giants a lead they would not relinquish. Fallibility, thy name was Loup’s. But not for long. The next night, Loup bailed out Lugo. Three nights later, he shook off a leadoff homer to Juan Soto (no shame in that) and mowed down the rest of the Nats in his inning. And when he pitched again, a couple of days later, he extricated Trevor Williams from a jam by stranding two of the starter’s runners and one of his own.

***

Just a beer before he goes. If we received the pleasure of Loup’s company in a postgame media session, we learned one thing that was as indisputable as his sub-1 ERA and his 1.000 winning percentage. The man liked his beer. Specifically, he liked Busch Light. Give him a chance to open, he said in Spring Training, and he’d take it because, “Who wouldn’t want to be the guy to start the game and then get to sit in the clubhouse and drink a few brews on the back end and watch the rest of it?” Loup successfully opened games twice, coming through with the necessary 10 Minute Head start the Mets ordered both times.

Most of his opening was of cans of Busch Light after pitching in a more customary role, evidenced by his usually bringing one with him to the Zoom room and giving it prominent product placement. The lefty developed a taste for it in 2019 when he called San Diego his professional home. It was a clubhouse thing, Loup explained to Justin Toscano in September. Keith Hernandez was known to have a bucket of Michelobs waiting at his feet postgame in his Met heyday, but that was the 1980s. A beer after the game didn’t elicit much notice in those days. These days we see what social media shows us and respond as if we’ve never seen it before. Loup and his Light became a bit of a thing.

So did Aaron’s honesty, which could be as bracing or refreshing as any cold one. Just before the direction Met players’ thumbs took drew everybody’s attention, Loup was asked about the booing that no Met was immune from — including him the night he gave up that momentum-turning double to Crawford. His ERA was still in the low 1s, yet that didn’t cut ice with the crowd after his aberrational bad outing. “It’s tough,” he admitted. “We definitely hear it. You try to drown it out and not pay attention to it the best you can, but we definitely hear it and it makes it tough. We’ve been struggling and not playing well and then when you come home and you kinda get booed off the field, it definitely doesn’t make it any easier.”

As for leadership in the contention-receding period when the Mets could have used a pair of broad shoulders on which everybody else could have figuratively jumped atop, Loup told Devin Gordon in September, “I think that’s probably the one guy we might’ve been missing this year,” somebody with the seriousness and stature to step up and say, “‘OK, that’s enough, it’s time to get down to business.’ Because we all know everybody’s trying, and you always get the rah-rah, ‘next game, you got this’ stuff. But at some point you need, ‘OK, enough. It’s time to go, now.’”

Lefty relievers — unless they’re carrying within the clubhouse the cachet of a McGraw, a Franco or a Wagner — probably don’t have the gravitas to be that guy. Too bad. But in light of being a journeyman on a one-year contract, it was enough that Loup cut his figure as he did, responded as best he could to the challenge at hand when his entrance music blared (“Unapologetically Country As Hell,” which my wife thought sounded a lot like the Li’l Sebastian song from Parks & Rec) and shared his beer and thoughts with us as he saw fit.

***If you partook of the 2021 postseason, you know that it wasn’t only the Mets who leaned on their bullpen to the point where starting began to feel somewhat irrelevant. With the exception of scattered gems, you’d be forgiven for thinking every game was a bullpen game, which was almost shocking seeing as how these were the best teams in baseball competing for a championship. Yet if you partook of the 2021 regular season, the sensation of managers scrambling to string together three outs en route to collecting twenty-seven of them actually felt pretty damn familiar.

In 57 games, or more than one-third, the Mets’ starting pitcher failed to go at least five innings. In 40 others, the starter went no more than five. Loup and Castro each opened two games on purpose, and rainy skies had their impact now and then, but most of the nearly 100 starts that didn’t reach a sixth inning were not by design or circumstance. It was because there wasn’t enough solid starting pitching to get the Mets through what you’d call a traditional rotation. Just get us some outs seemed to be the marching orders to whoever wasn’t deGrom or Stroman.

That’s what you usually tell your relievers. The Oft-Used Troupe listened closely and fulfilled their mission. Not flawlessly, but regularly. Enough to be trusted. Occasionally the trust felt misplaced, because who wants to pat a reliever on the back after a bad inning when all we needed was a good inning, but they kind of earned the trust. We as fans maintain the right to reserve our trust and disburse it in miserly fashion; we’ve earned it and aren’t shy about pointing to the mental scars that prove it. There’s a legitimate push-pull of compassion and derision when it comes to reacting to relief pitching. We are entitled to get annoyed when outs aren’t recorded, even preemptively annoyed that outs might not be recorded. Booing, actually or virtually, is definitely an option.

Yet fair is fair, and I have to tip a cap to one of Loup’s Oft-Used Troupemates, Trevor May — in whom I refrained from investing my trust more than once — for tweeting truth to fandom as the lockout set in and the topic of thumbs-down resurfaced:

“I owe you my very best version every time I take the field. My most prepared, competitive version. All the effort I have in my body. I give that, every damn day.

“I’m not a monkey that dances in proportion to the amount of nachos you buy at a game.”

Asking somebody new to do what Loup did for us, lefty or righty, is an enormous request. You’d settle for a Feliciano type to pick up the slack Aaron left in his free agency wake. We will need the toughness of May, the resilience of Diaz and the electric stuff of Castro to generate continually in 2022. They, like Familia and unlike Loup, rode a rollercoaster in 2021, but they all had spurts when they were only lightly hittable — and none of them fully imploded into a state of uselessness. If bullpen management under new dugout management reflects baseball broadly, we’ll need a cast of dozens filtering in and out of the pen. The Yennsy Diazes, Jake Reeds and Geoff Hartliebs, by their or somebody else’s names, will likely be getting up in a fourth inning near you.

DeGrom, we who are known for our faith have been led to believe, will be healthy and ready to go whenever the gates to Spring Training are unlocked. Scherzer, we’re pretty sure, is going to be Scherzer. That still leaves a day of hoping hard that first-half Walker vanquishes second-half Walker and two other days in the zone of uncertainty (Carrasco, Peterson, Megill, Williams, Lucchesi, whoever) where praying for rain will only get you so far. That’s three days when you’ll be glad to have a bullpen that functions as well as the Oft-Used Troupe of 2021 did. And, if we’re being honest, deGrom’s and Scherzer’s starts may project as brilliant, but they’re probably not gonna go nine.

No, we won’t have Aaron Loup around being as country and effective as hell, given that he converted his 0.95 ERA to two-year deal with the Angels. And we won’t have Jeurys Familia, whose modest renaissance — there were times his sinkers sunk batters like it was still most days in 2015 and 2016 — will win him a free agent shot somewhere. Jeurys already said his goodbyes through Instagram on the final weekend of the season. “[E]very day that I get out of bed, one of the first things [to] cross my mind is what to do to be better and give the best to the best fans in the world of baseball,” Familia posted. “For the fans, despite all the boos, bad words and everything bad that they may think of me or wish me, I put myself in their chair and I understand it perfectly. They have been waiting for a championship for many years.”

It is not to jab at how Jeurys pitched in 2021 to say this might been his most effective delivery in ages. The least we can do is return his pitch in kind and tell Familia, Castro, May, Diaz and MVM avatar Loup, hey, thanks for giving us your best, which is often pretty damn good. And when your best doesn’t always translate as great once the ball leaves your hand…well, we’ll do our best to trust you to try it again.

FAITH AND FEAR’S PREVIOUS RICHIE ASHBURN MOST VALUABLE METS

2005: Pedro Martinez (original recording)

2005: Pedro Martinez (deluxe reissue)

2006: Carlos Beltran

2007: David Wright

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Pedro Feliciano

2010: R.A. Dickey

2011: Jose Reyes

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Daniel Murphy, Dillon Gee and LaTroy Hawkins

2014: Jacob deGrom

2015: Yoenis Cespedes

2016: Asdrubal Cabrera

2017: Jacob deGrom

2018: Jacob deGrom

2019: Pete Alonso

2020: Michael Conforto and Dom Smith (the RichAshes)

Still to come: The Nikon Camera Player of the Year for 2021.

Thanks to Baseball-Reference and MLB Trade Rumors for their assistance in compiling data for this article.

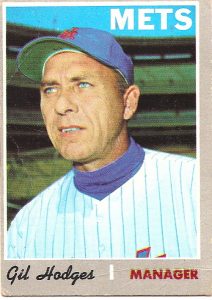

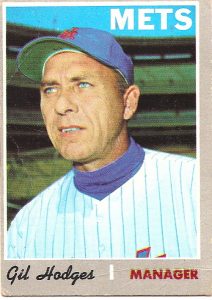

by Greg Prince on 5 December 2021 9:24 pm I no longer have to tell you why Gil Hodges belongs in the Hall of Fame, and you no longer have to tell me why Gil Hodges belongs in the Hall of Fame, and we no longer have to tell anybody why Gil Hodges belongs in the Hall of Fame.

That’s because Gil Hodges is in the Hall of Fame.

Gil Hodges is in the Hall of Fame. There are no better eight words a New York Mets fan could utter, no better eight words a Los Angeles or Brooklyn Dodgers fan could utter, no better eight words a Washington Senators fan could utter. Nobody who loves what baseball feels like when baseball is at its best could utter eight better words than Gil Hodges is in the Hall of Fame.

Gil Hodges is in the Hall of Fame. My, that feels good to write, to say, to think, to know. For Joan Hodges, widowed nearly fifty years, living for this moment. For Gil Hodges, Jr., who has carried the responsibility of speaking for his father through so many disappointing selection processes. For everybody in the Hodges family. For everybody who feels like a not-so-distant relation to the Hodges family because of who Gil Hodges was, what Gil Hodges did and how Gil Hodges carried himself.

For the Mets who played under and with Gil and have sworn by his example and influence. For the Senators of the ’60s who got the first taste of Gil as a manager. For those Dodgers who’ve remained to tell their true-life tales of a peer they revered. For those wrote about him while he created a Hall of Fame candidacy via his actions and deeds. For those who continued to amplify and elaborate his bona fides after he was gone. For those with whom he served overseas. For those who understood first-hand his generational legacy, whether they learned it in Petersburg, Indiana, or within (or proximate to) any of the five boroughs of New York City.

Baseball Hall of Famer Gil Hodges. This is a great moment in the life of the National Pastime. This is what happens when the words keep flowing and the passion bubbles over and we don’t stop talking about why a man who transcended a specific honor deserved the honor nonetheless. We kept it up because it meant the world to so many in this world that he got it. And, at last, he did.

Gil Hodges is in the Hall of Fame.

As are, not incidentally, Buck O’Neil, Bud Fowler, Jim Kaat, Minnie Miñoso and Tony Oliva. Six new plaques representing six people and six sets of stories whose impact on baseball was immeasurable in their day and for the years, decades and centuries that followed. O’Neil many of us met through Ken Burns. Once we met him, we would never forget him. We can never forget Fowler, who, like O’Neil, withstood the curse of institutional racism to play the game he loved. Miñoso came along much later than Fowler (1858-1913) and a little later than O’Neil (1911-2006), but not so late so that segregation didn’t unfairly separate his talents from what were considered the major leagues. Miñoso was a major player for the New York Cubans before having the opportunity to join the Cleveland Indians. His career coincided with that of Hodges and overlapped with those of Oliva — a preeminent hitter — an Kaat — a pitcher who succeeded at his craft for a quarter-century.

Every one among those six makes the Hall of Fame look good for hanging markers in their honor. The Hall would look even better with a few more from those its committees considered this year, but, as the 1969 Mets led to the promised land by Gil Hodges taught me when I was young, one miracle at a time.

It shouldn’t have taken what felt like a miracle for Gil to get in. He earned election through a big league playing career that extended from 1943 (before it detoured into World War II) to 1963 and was burnished by a managerial career that lasted from the moment he retired as a player until a heart attack felled him in 1972. He was the indispensable power-hitting cog of the Brooklyn Dodgers’ pennant factory, a plant whose production reached its peak on October 4, 1955. Hodges drove in the winning runs and cradled the last out on the afternoon the Dodgers became world champs. Hodges was already Brooklyn’s favorite son, never mind that he was born and raised several states to the west. It was no accident he was in the first Opening Day lineup the Mets ever fielded. George Weiss and Casey Stengel knew that no matter who else they put on display at the Polo Grounds, fans from this National League town would come out to cheer for Gil.

Few hit more home runs or drove in more runs or better handled chances at first base when he played. Nobody inspired more loyalty when he managed. Think that’s hyperbole? His players are still loyal to him. Ballot after ballot, his name would appear for consideration, and ballot after ballot, the Swobodas and Shamskys and Seavers vouched for him. Vin Scully, who called Gil’s games in Brooklyn and Los Angeles, took the time as he approached his 94th birthday to author an essay asserting that Gil needed to be selected this time. Mind you, Gil was selected in all but name almost thirty years ago. He got the support of the necessary number of votes in the 1993 Veterans Committee balloting, but one of those votes belonged to Roy Campanella, who phoned it in from a hospital bed. Ted Williams, the manager who had to follow in Hodges’s immensely popular footsteps in Washington, chaired that committee and, for reasons best known to him in those pre-virtual communications days, wouldn’t accept Campy’s call, or at least his vote.

That’s the sort of detail that had vexed us every winter Gil Hodges was eligible for selection. That and all those hundred-ribbie seasons that went disregarded; the 370 home runs that stood, when he belted his last, as the most by any righthanded National League slugger, yet had never impressed enough writers from 1969 to 1983; the three Gold Gloves that would have been more except they didn’t invent the award until Gil’s tenure as a player was more than half over; and the unforeseen, overwhelming success of the 1969 Mets, who didn’t show up in Gil’s statlines but reflected his contributions to the baseball landscape as well as any home run record reflects anybody’s achievements. All that plus the torrent of admiration for the man and the absolute lack of criticism beyond analytical esoterica. His Wins Above Replacement could be debated if that was your bag. His character was unimpeachable.

As noted, we don’t have to do this part any longer. We don’t have to state Gil’s qualifications for Cooperstown. They are about to be etched on a plaque for everybody to see. We can travel upstate if we choose and read it for ourselves. We can simply know it’s there and feel good that the right thing sometimes eventually happens.

Gil Hodges is in the Hall of Fame. I know you know that, but I really do enjoy typing it.

The literary subgenre devoted to articulating Gil’s credentials for Cooperstown now goes out of business, but if it had to take more than a half-century to finally elect this worthiest of candidates, I’m glad that the wait lasted just long enough to include this marvelous piece of research, reporting and writing rendered by Friend of FAFIF James Schapiro. Treat yourself to what amounts to the closing argument on behalf of Gil Hodges for the Hall of Fame.

by Greg Prince on 3 December 2021 10:47 am When your team picks up a player or three at the trade deadline, you bank on capturing lightning in a bottle. Maybe three bottles. An arm or two to get you over. A quick bat attached to some quicker legs and surer hands. Come on over and lift us up. Yesterday we were strangers. Today we are comrades. Tomorrow…who knows?

The current version of tomorrow has arrived with resounding silence. That invigorating spate of Hot Stove arrivals and corresponding departures suddenly halted, a cacophonous crescendo transforming instantly into a locked out void. In the hours before Major League Baseball latched the door on the Major League Baseball Players Association, we were so busy virtually embracing our four fresh potential impact players that we barely had a breath to spare to note the au revoirs of those who had gained our devotion briefly, maybe longer.

Rich Hill, acquired (a great baseball word) from the Rays on July 23, signed with the Red Sox — one year, $5 million. He’s signed with the Red Sox seven times in a professional career that’s spanned nearly two decades. It’s as if Hill and Boston have one of those sitcom marriages that leads inevitably to a compulsory episode of “let’s renew our vows,” and the network keeps rerunning it. Hill has pitched for more than one out of every three major league teams. We were his eleventh. He made twelve starts for us. Most of them were competent. None was lengthy. One was a win for him, his last. I felt good that Rich got on the board for us. I wouldn’t have minded having him back so we could receive one of his five-inning specials every five days, but didn’t expect it. Hill will turn 42 when Spring Training is supposed to be in progress. Even our youthless movement has its limits.

Javy Baez, acquired from the Cubs on July 30, signed with the Tigers. I saw a picture of Baez trying on his Detroit cap. The look on his face suggested a thought bubble of “oh, so that’s what that D stands for.” Upon making the acquaintance of ye olde English logo, Javy said, “I’m really excited to be a Tiger now,” which probably syncs up with his excitement to accept six years for $140 million. I found myself excited when Javy hit, ran and fielded as a Met. I’d hoped he’d stick around, especially since getting him acquired required the trading of the previous season’s first-round draft pick. A couple of months with Baez flashing his ability in the middle infield turned the thought of second base without him rather drab. The striking out that he’s done most of his career? The bit with the thumbs down? I defer to Carly Simon’s approach regarding her bad news boyfriend Jesse: “I can easily change my mind about you.” That’s what happened with Javy. Like good ol’ Rich, he didn’t lead us to the playoffs after the deadline, but it was, in its way, a fun fling.

Marcus Stroman, acquired from the Blue Jays on July 28, 2019, signed with the Cubs. Marcus did stick around, long enough so that you forgot he was brought in as a difference-maker for a playoff push that didn’t push all the way through. Stroman was tantalizing in talent in ’19, and if he didn’t pitch the Mets to the Wild Card, he surely wasn’t the reason they fell short. Then came a COVID opt-out, which could have ended his stay at Citi, given that his contract was expiring in 2020, but the Mets made him a qualifying offer and Marcus smartly accepted. After a year of inactivity, he was the most active of Mets starters: 33 games, 179 innings and an ERA that ticked barely above 3. While deGrom went down and Walker blew up, Stroman stood sturdy. I found myself convinced as 2021 proceeded that Marcus was mostly using the Mets as a marketing platform for his brand, but once you realize franchises use players as a marketing platform for their brand, well, touché. A rotation that included deGrom, Scherzer, Stroman and others would have been more promising than whatever 2022 holds without him, but I never had the sense Marcus wasn’t going to test his worth (three years, $71 million) and discover it elsewhere — and I didn’t get the inkling that the hometown kid and the hometown team were meant to last. He was from Long Island and he succeeded in New York, but attachments are lately becoming more and more detachable.

Syndergaard, Loup, these three, all outta here! in a matter of weeks. Yet life, if not further offseason activity, is scheduled to go on. Compelling evidence of such a transitory existence could definitely make you pause to mull the comings and goings of people set against the mysterious backdrops of time and place had we not acquired those swell new Mets who will magically slide into our affections and replace the departed five in our concerns. We have Scherzer and Marte and Escobar and Canha. Chances are strong we’ll grow attached to these four, at least for a while, as soon as MLB reopens its doors and allows us the chance to legitimately latch on.

by Greg Prince on 29 November 2021 3:55 pm So far, the highlight of Max Scherzer’s career as a New York Met is he has agreed to a contract of $130 million over three years to be a New York Met. It won’t show up in the main statistical body of Scherzer’s Baseball-Reference entry, but it’s more than a lot of recent Mets have done to elevate our mood.

It’s November. Scherzer can’t pitch for us yet. But he can goose our outlook, and oh boy, has he. Yes, the multiple Cy Young winner will take Steve Cohen’s generous offer and join our other multiple Cy Young winner Jacob deGrom and form a one-two punch that should have visions of being on the right side of knockout after knockout dancing in our heads.

DeGrom and Scherz’

Before the bullpen stirs

DeGrom and Scherz’

As the K board whirs

DeGrom and Scherz’

Poke the other teams’ nerves

DeGrom and Scherz’

The high holy duo a Mets fan observes

DeGrom and Scherz’

Here’s hoping Steve keeps funds in reserves

Twenty-four other players will fill out the roster most days. We know who a lot of them are. A few holes remain. Maybe more than a few. Y’know what? They’ll be taken care of. Steve’s got this. He got us three legitimate players on Friday and a future Hall of Famer still riding his extended prime on Monday. I’m not interested at the moment in what hasn’t gone right in the past or what might go wrong in the future. I’m interested in rooting for a team that added Max Scherzer as co-ace to Jacob deGrom on the other end of a weekend that began with adding Starling Marte, Eduardo Escobar and Mark Canha to our lineup and general depth of being.

This is better than wondering what, if anything, the Wilpons can or might do.

Scherzer’s leanings were first reported in earnest Sunday night. He kept getting closer, we were told, without the deal being closed. I wondered what else he needed beyond the $40+ million a year for pitching a baseball. I was reminded of Joseph Hewes, delegate to the Continental Congress from North Carolina in 1776, who, upon hearing the first reading of the Declaration of Independence, expresses grave concern to Thomas Jefferson that “nowhere do you mention deep sea fishing rights.”

For $40+ million a year, Max Scherzer can buy himself an ocean. Or lease whichever one Steve Cohen owns.

Max landing on the shores of Flushing Bay felt too close to not reel in as Sunday night became Monday morning. Average annual value, the reporters said, had hit $42 million. If this was an elaborate prank, it was an expensive one, at least as measured in the toll it would take on our collective sanity had fruition proved elusive. No, this couldn’t be a tease. Scherzer didn’t have to be a Met when Sunday began. He had to be one before Monday grew dark.

And so he became one. He hasn’t pitched. He hasn’t tried on a jersey and smiled for the Zoom screenshots. If he’s taken the physical that makes everything official, word hasn’t leaked. But he’s here in all but physical presence ahead of the expected lockout (in a sport where megacontracts are being issued from coast to coast). He’s here because the Mets go after big names with big track records with big money and, lo and behold, such an approach works.

It will work even better when Max Scherzer pitches for the New York Mets. Soon enough he will.

by Greg Prince on 27 November 2021 12:31 pm When you accept the post of Steve Cohen’s personal shopper the week before Black Friday, you can expect to work the holiday weekend. Billy Eppler didn’t let the specter of ”unprofessional” agents sliding down the chimney deter him from his appointed cart-filling rounds. Somewhere between five and midnight on Friday evening, news oozed that the Mets had signed not one, not two, but three free agents, or three more than were projected by those who were convinced that because the Mets had seemed idle or been foiled before Thanksgiving, they were never gonna bring in any new players.

With the table cleared of Noah Syndergaard, Aaron Loup and the aborted homecoming of Long Island’s Own Steven Matz, Eppler has set a trio of places for…

• Eduardo Escobar, infielder!

• Mark Canha, outfielder!

• Starling Marte, outfielder!

The exclamation points are courtesy punctuation, extended from a desire to greet the new fellas with enthusiasm. In reality, one of them I’m pretty familiar with; one I kind of nodded and thought, “oh yeah, I know who that is”; and one I had to convince myself I’d heard of. Only Marte, a former All-Star for the Pirates, has made more than a cursory impression on me — definitely a good impression, though. Canha’s been busy in the American League, so we’ve basically missed each other to date. Escobar I remembered from the Diamondbacks, though his last stop was with the National League Central champion Brewers.

Last offseason, when I was paying nominal attention to the moves whichever GM the Mets had in office at the moment was making, the Mets ushered in Loup, Jonathan Villar and Kevin Pillar, to name three solid veterans. They all fell in that vast expanse of me knowing who they were yet not having informed opinions about. They came here and indeed acted as solid veterans, each contributing, none generating quite enough oomph to single-handedly transform the franchise. But we got to know them some and like them some. One we’ve already officially said goodbye to. The other two probably won’t be back.

I invoke last year’s pickups because this is how roster construction happens. Guys come, guys go, and in between we find out if it was fairly worthwhile for us. If it was, we will warmly applaud when the guys who left come back in the visitors’ uniform. If it wasn’t, we likely won’t throw up our hands in disgust and browse for a new team. Give us some Mets, we’ll cheer them unless motivated to scowl like hell in their general direction.

These boys of late autumn 2021 will probably stick around a touch longer than last winter’s one-year wonders. Marte’s deal is reportedly four years and $78 million. He’s a centerpiece center fielder in the reimagining of the Mets. That’s something we could use. Escobar signed for two years and $20 million and should see serious third base or perhaps second base action, Javy Baez’s whereabouts pending. Canha’s a corner outfield type who’s also in for two years, in the mid-$20 millions.

Steve Cohen does not send his personal shopper into the marketplace lightly.

How will the new acquisitions mesh with the holdovers? Who will the holdovers be? What can we project for Marte, Escobar and Canha collectively and individually in 2022? What do their career arcs imply for the length of their respective contracts? What do the peripheral numbers say? Were these good signings?

Shoot, I don’t know. I never know. I can guess, but I choose not to. Instead, I choose a little of that elusive happiness we didn’t think we’d be receiving for a while when Steve and Billy didn’t come out of the gate with fountain pens blazing. The Mets have signed big league players with track records and presumed upside. That’s how free agency functions. The rest will be left to the near future to figure out. Also, it’s still November and other players (including pitchers) remain to be sought.

If the right guys come at the right time, as happened in Atlanta at the end of July, the deals go down as brilliant. Three guys are coming to Flushing at the end of November. It will take a little while to discern what it all means and will have meant before they’re gone. Escobar and Canha have two years to tell their story, Marte four. Until their contracts expire or are transferred and I have reason to rue the shortcomings their game revealed over time, I welcome their arrival with legitimate brio. A pre-lockout Black Friday extravaganza of this nature surely beats scouring the picked-over aisles at the dollar store.

by Greg Prince on 25 November 2021 8:49 am We have it from a reliable source that Steve Cohen was not happy yesterday morning. He had never seen such unprofessional behavior exhibited by a player’s agent. He guessed words and promises didn’t matter.

That was yesterday, Wednesday. Today is a new day, not only Thursday, but Thanksgiving Day. I hope Steve Cohen is happy this morning. I hope he sees professional behavior exhibited by players’ agents. I hope he revises his estimation on the mattering of words and promises. At the very least, I hope he and his family have a happy Thanksgiving.

If Steve Cohen can’t be happy, perhaps it proves the old bromide that money can’t buy happiness. Or maybe that happiness, like so many commodities these days, is bound to get held up in the supply chain. You’d think Steve Cohen would perambulate elated 24/7. You’d think we as Mets fans would be happy at least 23/6 that Steve Cohen lists the Mets among his assets. We sure as hell were a year ago. Perhaps our tendency to see Steve Cohen primarily as a walking billfold irked karma. Now that we’ve got an owner with sky-high resources, we’ll…

We’ll what? I’d contend we don’t know yet. We certainly haven’t contended nor poised ourselves to in the fairly near future. Early returns. Incomplete grades. Not much of a shakedown cruise in Season One of the Cohen Era, and Season Two can be termed only as in development. Steve tried to buy a little happiness by way of Steven Matz’s left arm. I don’t remember Long Island’s Own Steven Matz being a harbinger of happiness all that often as the kid from Suffolk County settled into his inconsistent period (2017-2020), but he was always a nice guy, he had a good free agent year for Toronto and did we mention he was from Long Island?

East Setauket Steve opted to go to St. Louis, prime destination for all our nightmare one-that-got-away scenarios. When we hypothesize worst cases, “just watch — he’ll go to the Cardinals and flourish” is our default mode. Should Matz indeed take to heart the unyielding embrace of the Best Fans in Baseball™, lap up the last ounces of nurturing Yadier Molina has on tap and evolve once and for all from a less aggravating Jon Niese to the second coming of Jon Matlack, well, happy Thanksgiving to him. And if he doesn’t, his agent still worked a pretty good deal for him: four years, $44 million. It’s gauche to count other people’s money, even if it comes with the offseason territory.

It’s gaucher, I would think, to throw a snit fit on Twitter, but maybe I don’t understand the particulars of super big business today. If the guy who could buy the Mets for $2.4 billion and not sweat the groceries prefers to call out Rob Martin — whose name I didn’t know until Steve Cohen made him a November 2021 character in our perennial twelve-month saga — rather than pick up a phone or send a message through channels, who am I to say that’s not the way it’s done? So we don’t have Matz. We didn’t have him anymore, anyway.

We also don’t have Aaron Loup anymore. We did have him. He was very good. His market was bound to blow up like a Macy’s Thanksgiving Day balloon after his ERA deflated so noticeably, all caveats about relief pitchers and earned run averages understood. Aaron might have pitched close to the tune of 0.95 again for us had the Mets matched or exceeded the length and width of what the Thorified Angels presented him (two years, $17 million). Or he and we might have come to learn why career years are termed as such. Good lefty relievers are by no means a dime a dozen, but arm barns are factory-installed with revolving doors.

Cohen tweeting his displeasure with Matz’s agent was a personal choice. The ballclub he owns opted for staid press releases (how quaint) to let us know three other tidbits Wednesday.

• The Mets signed Nick Plummer, a lefty-swinging minor league outfielder from the Cardinals organization (take that, Matz thieves).

• The Mets claimed waived Rockies righty reliever Antonio Santos, who used to be a starter and has mostly pitched in the minors.

• The Mets noted the removal from the roster of the Estrellas Orientales one Robinson Cano, whose lower back discomfort will be served better by physical therapy than continuing to play winter ball in the Dominican.

Plummer and Santos are each 25 years old. Coming to the Mets might do for them what coming to the Mets apparently did for Loup (or going to the Cardinals we dread will do for Matz). New GM Billy Eppler’s background is in scouting. Maybe he or somebody whose words and promises he trusts saw something particularly intriguing in them. Cano is 39, inactive for more than a year except for winter league stints and shaking off a second PED suspension. Unlike Plummer and Santos, Cano is owed an extraordinary sum. Extraordinary to everyday eyes. Cohen could probably write him a severance check between passings of the cranberry sauce this afternoon and still maintain a hankering for green bean casserole.

If our mouths aren’t exactly watering in the weeks since the hot stove began to flicker, let’s take solace in the knowledge that these days are just the appetizers. Even if everybody is instructed to leave the table and play a spirited game of lockdown touch football soon, a proper offseason dinner will eventually be served. Steve Cohen and we will find some semblance of happiness or at least more ballplayers, some of whom we’ll be delighted to have join us, a few more renowned than Nick Plummer and Antonio Santos, one or two likely fresher than Robinson Cano. There’s probably a manager plus a cornucopia of coaches being prepared for our consumption as well.

In the interim, a happy, bountiful and warm Thanksgiving to all. May it be filled with professional behavior.

by Greg Prince on 19 November 2021 6:50 pm It took Lily Tomlin’s character Debbie Fiderer two tries to win the favor of President Bartlet when she interviewed for the executive secretary position on The West Wing, though there was a good excuse for missing on the first try (“I was high”) and, honestly, Fiderer wasn’t really about winning anybody’s favor.

“All right,” Martin Sheen as Bartlet said, exasperated as their second meeting seemed to go as badly as the first. “I think the interview’s over.”

“Yeah,” Tomlin as Fiderer agreed sardonically. “But let’s do this every once in a while.”

Debbie gets the job in the end, as the viewer knew she would, because — c’mon, you’re gonna bring Lily Tomlin on the show twice merely for fleeting comic relief? And somebody got the job as Mets general manager after it seemed nobody would because, c’mon, somebody had to.

The Mets made the hiring of Billy Eppler official Thursday night and set him up with his ritual Zoom presser Friday afternoon. The ritual isn’t Eppler’s personally, but it is what everybody the Mets install for a prominent role in the offseason submits to. I know this because the Mets install a lot of new people for prominent roles in the offseason. This offseason. Last offseason. The one before it. The one before that. We indeed do this once in a while.

This franchise hasn’t bridged the gap between seasons without at least one dog/pony show of a New Sheriff In Town nature since the winter of 2016-17. Making their media debuts live or virtually to varying degrees of fanfare since the relative period of stability that reigned during the Sandy Alderson/Terry Collins epoch have been Mickey Callaway, Brodie Van Wagenen, Carlos Beltran, Luis Rojas, Steve Cohen (he bought his way in), Alderson 2.0, Jared Porter and now Eppler. I don’t think Zack Scott got an introductory Zoom, settling instead for a vote of confidence in a prepared statement, befitting his “acting” designation. A manager to be named later will fairly soon sit in his parlor or maybe in front of the wall of dancing logos at Citi Field and keep the introductions coming.

That’s a lot of getting to know people from scratch or, in Alderson’s case, with a fresh perspective. Sooner or later, the tidbits and nuances that seem telling at first blend into a blur. Whose priority was making the players feel loved? Who pledged to build a new culture? Who forecast a world championship in three to five years? Some of them? All of them? Presented in the best light possible when they couldn’t have been more enthused to take on their challenge, they seemed like excellent individuals well-suited for running whichever portion of the Mets was supposed to be their bailiwick and we, therefore, were set to benefit.

Most of those named above are no longer with us in the Metsian sense. Nobody who isn’t here left in a blaze of glory.

Eppler is among us for now, though, and that’s swell, I suppose. With Cohen and Alderson hovering in the adjacent, larger Zoom window, he seemed quite happy to have signed a four-year contract and was sincerely glad to tell every reporter over Zoom that it was good to see them and that they’d each asked a great question. He complimented the passion of Mets fans, which was worth one brownie point, and tied it to experiencing our “rabid” ways first-hand when he sat at Shea Stadium in 2005, which was worth another. He preached the importance of depth for a franchise that deployed 64 players in 2021. He mentioned something about hitters needing to make better “swing decisions,” which sounds an awful lot like knowing when to swing, except in jargon. Also, “probabilistic” is apparently the new “analytic,” which replaced “advanced metric” a few years ago, which itself replaced “sabermetric” in baseballspeak.

I don’t want to be too cynical about what the former Angels GM brings to the Mets, but I also don’t want to read too much into Day One. After so many of these fellows have zoomed into and out of our immediate consciousness, it doesn’t seem worth getting attached let alone excited. If I’m overcorrecting to the point of blasé, I’ll happily recant when the champagne is flowing in two to four years and swear I saw something special there all along, I’m an Eppler, we’re an Eppler, wouldn’t you like to be an Eppler, too?

Good luck, Billy. Good luck to all of us.

by Greg Prince on 17 November 2021 5:55 pm On November 8, the Monday before last, Edgardo Alfonzo turned 48. On November 16, this past Tuesday, Dwight Gooden turned 57. On November 17, today, Tom Seaver would have turned 77. Being a diehard fan means knowing when your favorite players — Tom, Doc and Fonzie are my Top Three — began to live. Being a diehard fan also demands your fandom and your appreciation of what and who you’re a fan of be taken seriously. Not everybody takes your demand or your fandom seriously, so when you come across those who do, you appreciate it. Given that this is the birth month of so much Met greatness (even the Met skyline logo was unveiled in November of 1961), November seems as good a time as any to appreciate those who’ve appreciated what it means to appreciate.

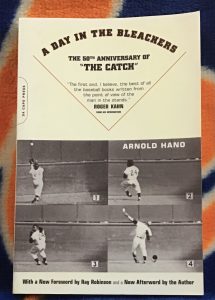

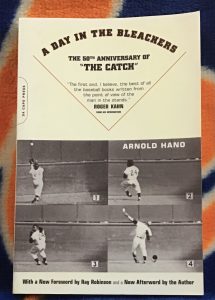

***It’s 1954 and nobody’s written at length about the act of going to a baseball game. Well, somebody somewhere probably did, but if they did, it hasn’t become part of the public consciousness. Nonetheless, Arnold Hano goes to a baseball game and decides to write about it. He makes an article out of his experience, submits it to The New Yorker, future home of Roger Angell’s fan/journalist essays, and has it rejected. So he takes his article and expands it into a book. It isn’t an easy sell — who wants to read about somebody going to a baseball game? — but Hano finds a publisher and, as a result, we can all find ourselves spending A Day in the Bleachers.

Arnold Hano, a book editor himself in 1954, inadvertently invented the literary form you read here and any number of places on a regular basis in the 21st century. It wasn’t called fan blogging, but he wrote seriously about being a fan: about wondering whether he should try to get a ticket for the game; about how best to travel to the game (opting for the short walk and long ride of the D train uptown from 59th St.); about the line that was already formed as he attempted to get into the game; about staking out his seat; about the fans sitting around him; about the view; about the food (“I had subsisted on two hot dogs, one beer and two cigars”); about the weather; and about the game itself in a very subjective manner.

The game was only the game in which Willie Mays made what is now known as The Catch. Nice game to pick, especially since what Mays was going to do couldn’t be known in advance. The World Series was in town. Arnold Hano was a Manhattanite and a Giants fan. The Giants were in the World Series. How could Hano resist? There were reasons, actually, mostly centered on supply and demand. But Hano threw himself into his quest, picking a subway, queuing up at the Polo Grounds, waiting out a low hum of anxiety over how many bleacher spots would be available as he berated himself over not arriving earlier, and eventually parting with the two dollars and ten cents it would take to gain admission.

This fella walks into a ballpark and invents a literary form. Hano got in and basically birthed the blog. He wrote about what we would write about five, six, going on seven decades later. He wrote about having to fork over fifty cents for a fancy souvenir program when all he wanted was “the old-fashioned everyday kind of program with a scorecard, the kind that sells for a dime”. He expressed dismay that some people feel it necessary to watch a live baseball game right in front of their eyes with the aid of a newfangled portable radio. He’s disdainful of the nearby lady Brooklyn Dodgers fan who has converted for the day to the cause of the American League champion Cleveland Indians (his takes on Dodgers and Yankees fans in general are what we’d today call hot). He hasn’t much use for many of the bleacherites around him. Hano came to see the game, but he sees all and reports back.

And he does it without an enormous video screen replaying every play, never mind the cues of Russ Hodges’s play-by-play. Hano sits hundreds and hundreds of feet from home plate yet discerns fastballs from curveballs because that’s how you had to roll at a baseball game in 1954. That’s what he’d been doing since discovering baseball in the 1920s. Young Arnold had been sent to while away summer afternoons at the Polo Grounds the way other kids were sent to day camp. He’d lived practically upstairs from the field, on Edgecombe Avenue, and his cop grandfather had a season pass to seats in the grandstand. Over time, Arnold decided he liked it better in the bleachers, where fans could eschew decorum and just be fans, even the ones he kind of rolled his eyes at as Game One of the World Series got underway.

The percentage of the population that can claim to know what it was like to go to a World Series game in 1954, to see the New York Giants, to see the Polo Grounds, to see 23-year-old Willie Mays running down the longest fly ball imaginable off the bat of Vic Wertz and then turn and throw it into the infield pronto is forever dwindling. Hano’s book, published in 1955, preserves all of that. The morning chill. The afternoon sun. The weirdo parading through the bleachers between during the seventh-inning stretch soliciting donations to buy each and every Giant a wristwatch or a Cadillac or some expensive token of appreciation…or so the weirdo swore. The game. Of course the game. The game that locked in at 2-2 and stayed that way into the tenth inning. Hano is all over The Catch Mays made on Wertz’s drive, but he’s all over everything.

“In the Giant tenth,” Hano notes after Cleveland manager Al Lopez has pulled out all the stops only to remain in a tie, “the Indians were down to a substitute first baseman, a substitute shortstop, a substitute right fielder, and a substitute catcher,” which is about as trenchant an observation as I’ve ever read about going to your bench and coming up empty. Bob Lemon — “a tired, very courageous gentleman” — is still at it on the mound for the visitors. Starting pitchers didn’t necessarily stop at nine innings (or nine pitches) in 1954, and partisans weren’t shy in their admiration for the enemy.

The game ends when pinch-hitter Dusty Rhodes takes advantage of the generous right field dimensions, “smiting the ball just as far as was needed” for a 5-2 Giants win that set the stage for a Giants four-game sweep over the heavily favored Indians. The other underdog turned hero from the story is Hano, who publishes the book, continues his career as a writer and advocate for more than sixty years beyond publication, and lives until the eve of the 2021 World Series. When word of his passing at 99 spread last month, I took A Day in the Bleachers off my bookshelf and reread it during the first two games of this year’s Fall Classic. Hano on the Giants and Indians made the Astros and Braves on Fox far more palatable than I could have fathomed.

***It’s 1987 and nobody’s routinely stayed up all night every night listening to somebody talk sports on the radio, him there, you there under the covers. Sports talk radio has been popularized in small bursts, but not around the clock, not to the point where “all-sports radio” doesn’t sound a little absurd in theory. WFAN, however, isn’t a theory. It introduces itself at 1050 AM at 3:00 PM on July 1, 1987, and announces it will be staying on with nothing but sports the rest of the day, into the night, into the wee hours every day and every night.

It’s kind of crazy, but it’s definitely happening. Jim Lampley, a familiar national sportscaster comes on after the first sports update at 3 PM, which itself is delivered by New England-accented Suzyn Waldman. Howie Rose, whom we know as the lone holdover from WHN, thanks to his new show Mets Extra, follows, bringing us to Mets baseball, rain delay and all. Because the Mets’ flagship is now an all-sports station, we aren’t sent back to the studio for the best of Merle Haggard and Loretta Lynn, their considerable talents notwithstanding. Howie stays on and keeps talking sports until the tarp is pulled. Bob Murphy and Gary Thorne take it from there, painting the word picture of the critical Mets’ 9-6 victory over the Cardinals, the otherwise frustrating Mets pulling to within 5½ games of first place.

Then, after the postgame edition of Mets Extra, to carry us through after midnight and before dawn is a warm, throaty voice that is more fan-friendly than radio-typical for 1987. He is not smooth like Lampley or the promised morning man Greg Gumbel, who we recognize from television. This guy we don’t recognize at all. He is a lot of shtick at first listen, yet the shtick sticks. It stuck on me instantly and it stuck around for the next 34 years.

Steve Somers was one of the original voices of the FAN and the last to stay in a regular time slot from the station’s inauguration until just this week. He was Captain Midnight in the late 1980s until the mid-1990s. Then he moved around the schedule some, landing for keeps in the evening/late evening. Steve who came from San Francisco fashioned himself into a native New Yorker around his 40th birthday. He belonged here all along. He fit most comfortably overnight talking sports — a lot of Mets, in particular, as the Metropolitans became his baseball team — and talking life from somewhere in Astoria. Other hosts wanted to let you know how much they knew. Steve insisted over and over again there was no such thing as an expert. Other hosts lost patience with callers. Steve let them go on because it was the middle of the night and he was grateful anybody was on the other side of the phone let alone the other side of the glass. As his nudged if not forced retirement moved into focus this fall, he and those who valued working with him and talking to him came on to schmooze with him, mostly about what it was like all those years ago first hearing him.

WFAN, ensconced at 660 AM since October 1988 and simulcast over 101.9 FM in November 2012 (plus whatever name the app goes by presently) can wear on the modern ear quickly, perhaps because we’ve all trained ourselves to conduct a sports radio show in our head, but no radio station has ever been better about mythologizing itself. When a WFAN voice with ties to the station’s beginnings commences a dialogue with another voice with ties to the station’s beginnings — turning the clock back to July 1, 1987, and the dial up to 1050 AM — it reminds us that we as fans who were tuned in the second WHN signed off from playing country music were about to be taken seriously like we’d never been taken seriously before. Any time, day or night, somebody was likely to weigh in on Darryl Strawberry. Whether they made any sense or not didn’t matter. I kept reading in the papers back then that an all-sports format would never work. Suddenly superserved by one, I wondered how an all-sports format hadn’t already existed. There were a lot of us out here. We were up at all hours. I was in my night owl mode when Steve Somers landed in New York. I never called him, but I was sure he was schmoozing in my direction, certainly in my wheelhouse.

He did this one bit for a while that has stayed with me. Every night (or morning) at 3 A.M., he would play “Night Moves” by Bob Seger, using it to soundtrack the essence of his autobiography, hailing the night as the time when you could sit in your solitude and contemplate your future and where it might take you. There’s a line Seger has in there about a girl he knew when he was young. You know: a black-haired beauty with big dark eyes, and points all her own, sitting way up high…“way up firm and high.”

Without fail with “firm and high,” Steve would interject, “she went to a good school.” Every night I knew it was coming and every night it cracked me up.

***Until 1898, the Long Island towns of Hempstead, North Hempstead and Oyster Bay were part of Queens County. In 1898, you might say, Queens took the qualifying offer Greater New Yorker put on the table and joined the new five-borough jurisdiction that is now known as New York City. Its eastern towns, however, were left dangling. For the first few weeks of municipal consolidation, they remained part of Queens without being included in the new NYC. Talk about unwieldy. The solution, reached on January, 22, 1898, was for the superfluous trio to give up their Queens identity and form their own county: Nassau.

This is all according to the official Nassau County website and it’s a little relevant to our conversation because nearly 124 years later, the Queens Baseball Convention gaveled into operation not in Queens, but in neighboring Nassau. Actually, I don’t think a gavel was involved. Nevertheless, jurisdictional niceties may have seemed slightly confusing to those looking at QBC last weekend and wondering what it was doing convening outside the home borough of Mets baseball.

It was making for an Amazin’ time, of course. QBC always does that, no matter where it is. But if the geographic thought did enter the intersection of one’s thoughts, it should have scurried along quicker than the traffic on Sunrise Highway. Metsopotamia, after all, is a state of mind, and Mets fans don’t have to be in Queens to congregate with other Mets fans. QBC proved that in Wantagh on Saturday. I, for one, was delighted by the latest location of the only For Mets Fans By Mets Fans fanfest in operation because, quite frankly, it was a helluva lot closer to where I live than it used to be.

Convenience! It’s not to be underrated nor overlooked. Because QBC paid homage to Queens’s former borders, I didn’t have to schlep on various Long Island Rail Road and subway trains to meet it more than halfway. Instead, I hopped in my sturdy Toyota (it predates Nassau County’s centennial) and zipped across side roads to Mulcahy’s of Wantagh. It was so convenient, I did it twice. Stephanie, you see, was very much up for QBC, maybe not so up for the full seven or eight hours it goes on. No problem, honey, I gallantly said to my wife. After the first couple of hours, I can take you home and head right back. (She offered to take the LIRR, which was also convenient to Mulcahy’s as well as thoughtful on her part, but I wished to revel in my rare alignment with the defining feature of suburbia.)

Location, location, location, as they say in real estate. Affinity, substance, bonhomie, as we say in fandom. Put them together, and you had the keys to what made this QBC as wonderful a QBC as any of those where the Queens aspect was literal. It was worth reaching by any conveyance, wherever you were coming from. It was so nice it was worth reaching twice. It contained such a storm of Metscentric activity that you barely noticed the tornado flying through nearby if not frightfully nearby portions of Nassau County. At one point an announcement was made about a tornado warning — we don’t get many of those around here — and things grew a little eerie for a few minutes, but nature looked kindly on our gathering at Mulcahy’s Pub and Concert Hall and conveniently left Wantagh alone.

My primary reason for attending QBC was to play a role in handing out the Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award. It doesn’t usually take more than one set of hands, but this was a very special presentation, to the family of the late Shannon Forde. If you asked everybody who treasured their relationship with Shannon to help hand out this award, we’d still be there.

I was honored to represent the blogging community. Mets fan blogging began in earnest in the 2000s. Shannon, whose job with the Mets was in media relations, was one who took notice and took action. She invited a bunch of us bloggers to Citi Field as media. She saw the likes of us as a legitimate vehicle that delivered information and perspective to Mets fans. Probably not everybody in her job would have reached out. Shannon went extra miles to make sure we were communicated to by the Mets so we could communicate a little better to the Mets fans for whom we wrote. The “mother’s basement” stereotype was still rattling around then. If you dismissed bloggers’ existence, you didn’t have to pay attention to what they blogged.

That wasn’t Shannon’s style. She treated us like she treated everybody within her professional purview: with nothing but good humor and implicit respect. Shannon took our little cohort seriously, maybe more seriously than some of us took ourselves. It wasn’t just that she invited us out to the ballpark. She waved us inside spaces where most of us would never have otherwise set foot. It was as if she ran around to a side entrance, held a door open for us, and told us, “It’s OK, come on in, you belong.” She understood we who weren’t card-carrying members of the BBWAA may have required a little TLC at first, yet she never approached us as anything less than professionals.

Shannon believed we had a place there as people who were simply trying to tell the Mets’ story in our own individual ways to readers who simply wanted to understand the Mets from every angle possible. We the fans who blogged represented the fans who read. Shannon got that. She provided us a runway to hone our insights and present our team in ways we couldn’t have otherwise. It’s hardly the only reason QBC wanted to acknowledge her, but a lifetime of kindnesses of that nature add up. When she died at 44, everybody who’d come in contact with her praised her for her skills, her professionalism, her trailblazing and, most importantly, her humanity. Gil Hodges left us in 1972, Shannon Forde in 2016. It’s never too late to say a good word on those who made their world better.

The rest of my non-commuting QBC day, given that the organizers didn’t burden me with any other official responsibilities, was dedicated to listening to other folks on stage and hanging out with Mets fans all over Mulcahy’s. There was a lot of hanging out. There were a lot of Mets fans. Mets fans I’ve known for years. Mets fans I was just meeting in person. Mets fans I hadn’t seen since the last QBC in 2019, who I mostly see at QBCs. It was as if my social media feeds had sprung to life, but only the pleasant threads.