Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

Keep on searching now

Got to look up

Don’t look down

Keep the faith

—Little Richard

As baseball’s Winter Meetings approached in 1974, the Mets’ new general manager, Joe McDonald, drew some attention when he told reporters that he’d be aggressive in the trade market and that the only players he would consider “untouchable” were his big three starting pitchers: Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman and Jon Matlack. I guess it was a newsworthy enough statement that my sixth-grade teacher incorporated the anecdote into an upcoming vocabulary lesson.

“The Mets said they have only three ‘untouchable’ players,” Mr. Schneider told us. “Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman and Tug McGraw.”

On one hand, I was delighted that the Mets had broken through the elementary school wall and had become part of our curriculum. On the other, Mr. Schneider’s inaccuracy played like fingernails on our blackboard to my ears. Clearly Mr. Schneider had read the same article I had. Mr. Schneider was a prototypical cool teacher; a year later, Gabe Kaplan would play a version of him on television. But c’mon, Mr. S., get your facts straight.

In our casual open classroom atmosphere, I didn’t bother raising my hand. I just called out, “Jon Matlack, not Tug McGraw.” I did that a couple of times. Mr. Schneider ignored me. His point was his point, whatever it was. The implication, however, is what stays with me to this day. Tug McGraw seemed untouchable because the idea of the Mets trading Tug McGraw seemed unimaginable.

Yet on December 3, 1974, Tug McGraw proved touchable. McDonald and the Mets traded him.

It’s still unimaginable.

Three years after the Original Mets made their unique impression, along came a man who could only be termed the Met original. Within the realm of “there’s nobody like him,” there was nobody like Tug McGraw — not playing for this franchise in the 1960s and 1970s, not doing anything for anybody anywhere, probably. Amid a stream of characters who’ve defined what’s it meant to be Mets, Tug stands out as one of a kind.

He was a goof.

He was a wit.

He had a soul which often came to the fore

He had a heart which he inevitably wore on his sleeve.

He mastered a pitch few threw.

He coined a phrase everybody knew.

He was Tug McGraw.

Of the Mets.

And the Mets traded him.

In December of 1974, if you could pull yourself back from remembering who he was, you could imagine it. Except you couldn’t pull yourself back from remembering who he was. You couldn’t imagine doing that. Why would you? A thirty-year-old reliever coming off a dismal season after having been not so hot most (but not all) of the previous season, especially if you could fill a couple of holes by trading him…him you’d trade.

But if his name was Tug McGraw, and he’d been Tug McGraw of the Mets for nearly a decade and you understood what that had meant on the field, off the field and to the fans?

What the hell? They traded Tug McGraw?

I graduated sixth grade more than 45 years ago. I still haven’t solved the emotional equation that allowed for the trade of the pitcher who wore No. 45.

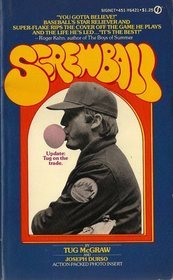

I didn’t read Screwball until it was out in paperback, which wasn’t released until the co-author (McGraw wrote it with Joe Durso) was no longer wearing the outfit he modeled on the cover. The cover, in fact, promised that in this edition we’d get “Tug on the trade.” That covered just a couple of pages up front. The rest was what was published following the 1973 season, when it was concluded that people would want to read what some lefty relief pitcher had to say about his life and everything around him. Following the 1973 season and postseason, Tug was a figure of immense public interest.

We’d been into Tug one way or another since a 20-year-old southpaw from somewhere in California showed up in St. Petersburg and introduced himself to Casey Stengel. The Mets were making room for myriad young arms in New York. None of them was lifting the 1965 Mets from the cellar. One of them, however, beat Sandy Koufax. Tug took his lumps plenty before August 26, before doing his first version of the unbelievable. Koufax, the premier pitcher of his generation and perhaps his century, had defeated the Mets thirteen times since 1962. The Mets had defeated him never. Given that one entity was at his peak and the other was permanently in the pits, who could possibly reverse the pattern?

Frank Edwin McGraw, Jr., that’s who. Not that anybody ever called Tug that except to let you know he wasn’t technically a born Tug. Almost born that way, but not quite. According to Screwball, Frank became Tug based on his behavior when “my mother used to nurse me when I was a baby and it was chow time. I guess she began calling me her little Tugger, and as time went by, everybody began using that name. While I was growing up, that’s what I thought my name really was.”

Tug followed his older brother Hank (Frank, Hank; it could get very confusing among the McGraws) into sports, then into baseball, then to the Mets. Hank never made it out of the minor leagues. Tug got his big break in 1965 when the Mets attempted to portray their Youth of America as in full bloom, regardless of their individual states of readiness. Sixteen of 43 players used that year were 23 or younger when the calendar flipped to ’65; ten of them were making their major league debut that year. One of them, Greg Goossen, was destined to go down in baseball history as the crux of one of Stengel’s best and last lines, said to have gone something like this:

“And we’ve got this kid who’s twenty who in ten years has a chance to be thirty.”

Except Greg wasn’t even twenty yet. Goossen made his MLB debut at 19. Jim Bethke and Kevin Collins commenced playing in the big leagues in 1965 at 18. Tug, a little more than two months the senior of veritable veteran Ed Kranepool, was an old man of 20 when Casey handed him the ball in the eighth inning at still-spanking new Shea Stadium on April 18. Relieving Jack Fisher, who had relieved Al Jackson, Tug McGraw entered his name in the Met annals by striking out Orlando Cepeda with the bases full of San Francisco Giants. “I jumped up in the air and started walking around like we’d just won the World Series or something,” he’d recall. Except that was only the second out of the inning. After retiring opposing pitcher Bob Shaw to fully escape the jam, Tug was literally shaking. Trainer Gus Mauch handed him a couple of tranquilizers.

The real excitement came four months later, McGraw vs. Koufax, Tug having been assigned to the starting rotation by Stengel’s successor Wes Westrum only recently. When that one went final in favor of the Mets, “I started jumping up and down when it ended, going crazy as usual, but this time the rest of the guys didn’t shake their heads or anything, and nobody went around the locker room saying McGraw’s some strange cat.”

He was, though, in the best sense possible. When I read Screwball, I realized conformity was overrated and that sedation wasn’t necessarily advisable. McGraw didn’t turn 21 until a few days after beating Koufax, though he didn’t have a straight line to success in front of him directly thereafter. Tug’s rookie year yielded a 2-7 record. Beating Sandy Koufax came four days prior to his 21st birthday and four days after his first win. The decisions would pile up in September in the wrong direction. Then came a detour into the Marine Corps to fulfill his service obligations. The USMC wasn’t exactly Tug’s bag.

Tug’s baseball career didn’t march in formation for the next three seasons. He experienced injuries. He experienced setbacks. Besting Koufax made for a great trivia question, but by 1968, there wasn’t a whole lot else to his CV. The lefty was studying barbering in case baseball wasn’t a long-term bet. The new manager, a Marine vet named Gil Hodges, sent him to Triple-A Jacksonville in hopes the now 23-year-old — married to a lady named Phyllis, taking care of a pooch named Pucci, and honing a pitch he referred to as a screwjie — would come down with a case of latent maturity.

In 1969, Hodges found room in his bullpen for an older and reasonably wiser McGraw, and McGraw contributed substantially to what was about to become known as a Miracle. It was the dawn of an era when a good relief pitcher was understood to be something more than a failed starter. Tug thrived in the later innings, or whenever Hodges decided he needed Tug. In 1969, when the likes of Seaver, Koosman and Gentry weren’t finishing everything they started, McGraw relieved 38 times, posting eight wins from the pen along with a dozen saves. Tug didn’t get into any of the games versus Atlanta or Baltimore in the postseason, but as lefty partner to righty Ron Taylor (9 W, 13 S), he provided an extra measure of certainty that the Mets would get there.

Plus his teammates appreciated him. Consider Art Shamsky in 2020 reflecting on what he remembered from playing behind and being around Tug McGraw some 50 years earlier (I asked Art about Tug when I spoke to him last week):

“Tug might’ve been the greatest character I’ve ever met in the game, and there were a lot of characters I’ve met over the years. Tug was the kind of person who, any time, any situation, any place, any circumstance, would say what’s on his mind. He was such an outgoing, gregarious, full-of-life person. He was just very, very special. A fun teammate, a great guy to be around, always seemed to be in a good mood. Just made everybody around him laugh. Along with Koosman on that team, just two of the best teammates you could want. He loved life. A special friend. A special guy.”

The early ’70s should have been Tug’s time. In many ways, they were. He was established reliever with a World Series ring to his credit. The screwjie, or scroogie, however he chose to spell it, got better and better. In 1971 and 1972, he unfurled ERAs of 1.70 in consecutive years, and before you kick that relief pitcher earned run averages don’t tell us much, understand that in those two seasons, Tug threw a combined 217 innings, or precisely as many as Jacob deGrom threw in 2018, when he posted his mind-boggling 1.70 ERA. In ’72, Tug saved 27 games, by far a Mets record (it would go unsurpassed at Shea until Jesse Orosco topped it in 1984) and made the All-Star team, the first Mets reliever to do so.

But Tug wasn’t necessarily the type to feed off success without a struggle. He’d been that way since he was earning his nickname in infancy. One of the most affecting chapters in Screwball revolves around a Mets road trip that took Tug to California in 1970. His parents, already divorced, were around, and he could feel the tension. The shootings of student protesters at Kent State by members of the Ohio National Guard had happened, and Tug couldn’t quickly or quietly tune them out. “I never could believe that the country had reached the point where National Guard guys would have to shoot other people,” he wrote. And the pitcher’s mound didn’t necessarily offer refuge. Even after rescuing the team from a jam at Candlestick Park, Tug found himself “wobbl[ing] into the clubhouse. I got the hell out of sight somewhere in a corner and started sobbing again.”

Tug tried to sum up his feelings in his diary: “I really don’t know in which direction to head or what to do. Why? Because I’m a people and I’m screwed up.”

When things appeared their bleakest, Tug encountered the power of positive thinking in the person of Joe Badamo. As Tug put it in Screwball, “He sells insurance. Insurance and motivation.” Tug knew Joe through Duffy Dyer, who, along with some other Mets, was introduced to him by Hodges. Badamo may not have been a guru, but Tug was willing to follow what he had to say.

“We rapped a while,” Tug wrote, eventually coming around to the twinned subjects of confidence and concentration, and the only way the motivator said the pitcher could ensure having both was “to believe in yourself. Realize that you haven’t lost your ability. Start thinking positively. Damn the torpedoes, and all that jazz.”

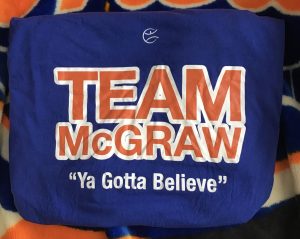

Tug took it to heart. “I said, ‘You gotta believe. That’s it, I guess, you gotta believe.’”

From one conversation with one person, a movement was born. Tug threw “You Gotta Believe” to a few fans and they threw it back to him as if in a game of catch. He brought it into the clubhouse, and it caught on. Without thinking, he blurted it in the middle of a pep talk delivered by chairman of the board M. Donald Grant (and later had to convince the stodgy executive he wasn’t mocking him). “You Gotta Believe” took root in July, when the injury-riddled Mets were still in last place, when Tug was still in his epic 1973 slump.

The spirit that captured New York and conquered the National League was alive and well at Shea Stadium in 1973.

It took on a life of its own in September, as the Mets made their move from last place to first place in the space of less than a month. Tug’s year was reborn. Tug on, if you will, this statistical beauty: From September 5 to September 25, as the Mets took 15 of 19, McGraw made a dozen appearances. Every one of them was a personal and team success: he saved nine games and won three more. Eight of the outings were at least two innings long.

The Mets were on their way to the division title, the pennant and a seven-game World Series duel that fell just a touch short of dethroning the Oakland A’s mid-dynasty. Tug was more than a beloved teammate and character by the time it was over. He was a folk hero, a legend, the personification of Belief. By shouting and leaping and pounding his glove to his thigh (and getting batters out by the bushel), he was the Met who made 1973 a miracle of its own. The Mets have never retired “You Gotta Believe” as a catchphrase since then. When things get dark enough to allow in only the slightest glint of light, it’s the light that takes precedence in our collective inner Tug. We gotta believe, we keep telling one another, because in 1973, that’s what Tug told us. Those words would live with us forever.

Yet somehow, Tug McGraw would stay in our immediate company only one year longer.

“If I got traded,” he said in Steve Jacobson’s book, The Pitching Staff, “I wouldn’t even know how to put another uniform on.”

He’d get practice.

Joe McDonald touched him and traded him. Tug McGraw, Don Hahn and Dave Schneck to the Philadelphia Phillies for Mac Scarce, Del Unser and John Stearns, not necessarily in that order. Scarce, to be 26 on Opening Day 1975, projected as the direct replacement for McGraw, at least in theory. He was a lefty the Mets had seen plenty over the years. Scarce’s ERA versus New York between 1972 and 1974, covering 13 appearances, was a scant 1.37. If Mac could do something like that against everybody else, you couldn’t say he wouldn’t represent something approximating an upgrade over an older pitcher who’d mostly flailed for two years (save, of course, for a memorable September and October).

Unser, turning 30 himself, was a pro’s pro type. Got to balls in center, made contact at the plate. Hahn wasn’t the answer in New York. Schneck, my own fixation on his name when he came up from the minors in 1972 notwithstanding (I loved that we had a guy named Dave Schneck), never made much of multiple auditions on the major league level. Combined with another fall 1974 acquisition, Gene Clines from Pittsburgh, Del Unser meant the Mets were upgrading their outfield for ’75 for sure.

John Stearns was the real prize if you had a telescope. That was the sell from McDonald. The Phillies had drafted Stearns out of the University of Colorado second in the nation in 1973. He was a football star, but was channeling that aggressiveness into baseball, specifically at catcher, a position where the Mets couldn’t rely on Jerry Grote into eternity. Stearns was 23 at the time of the trade. In ten years, he had a chance to be star.

This was a wise trade on paper. Center field was improved immediately. Catcher was taken care of for the future, at least as much as one could see ahead. The new bullpen lefty certainly hadn’t put up numbers that would make you believe they would be any worse than what you were replacing.

This was a horrible trade in the heart and soul. The Mets traded their heart and soul and threw in a spirit to be missed later. Tug McGraw told us we had to believe. Forgive us if we couldn’t believe this was happening.

The trade from December 3, 1974, proved to be the most frustrating kind. There were no winners. Or, more specifically, there were no losers. Trades where you can gloat that you stole somebody and gave up nobody are the ones you take pleasure in citing for eternity. We cite the Keith Hernandez trade that way. Angels fans cite the Nolan Ryan trade that way, presumably. I wouldn’t blame Phillies fans for feeling perpetually good about getting Tug McGraw as they did. They had a catcher, Bob Boone. They had, after another trade, Garry Maddox in center. They weren’t missing Unser or Stearns. In fact they’d get Unser back down the line.

We wouldn’t miss Hahn or Schneck. Unser was very good in 1975. Batted .294. Gave us defense the likes of which we hadn’t enjoyed since the height of Tommie Agee. Should have made the All-Star team, I will always insist. Then the Mets traded him to Montreal in 1976, sending Del and Wayne Garrett north for Pepe Mangual, Jim Dwyer and a dose of incredulity. Maybe he’d never have another 1975, but Unser’s value as a bench player would endure into the next decade. He’d be part of a certain Phillies team that won a certain world championship.

The Phils didn’t miss Scarce. Neither would we after his exactly one appearance as a Met. It didn’t go well, losing a game as it did. Then Mac was knifed from the Mets’ plans, traded to the Reds for Tom “The Blade” Hall. I honestly thought Scarce wouldn’t be bad. I at least thought he wouldn’t be scarce.

The idea of Stearns taking over behind the plate for the Mets was a great one. It wasn’t only a great idea, it proved a fine reality. After backing up Grote in ’75 and volunteering to get better at Tidewater most of ’76, Stearns became the No. 1 catcher Flushing in ’77. He also became an All-Star for the first time — the first of four times as a Met. Granted, John’s All-Star selections generally fell in that “we have to take a Met” category, somewhere behind the Benches, Simmonses and Carters of the National League, but an All-Star is an All-Star. Bad Dude, as he was called, was solid behind the plate. Took no guff. Didn’t care for losing, which, unfortunately, the Mets of his era did a lot. That wasn’t John’s fault. When he was healthy (which wasn’t always), John led those Mets as far as they could be led. He hung on long enough to see the Mets turn the corner into contention in 1984. He deserved to be part of the kind of team they were becoming. He was one of my favorites of his time.

Any trade that brought us John Stearns and left him with us for a stretch of ten seasons could not be considered terrible. It wasn’t Ryan-for-Fregosi or Otis-for-Foy or any others you care to rue. But it’s hard to say it was a win for New York. New York sent Tug McGraw to another city. That it was a nearby city whose team competed in the same division, and that team was already getting better, and that they’d be in the playoffs perennially, and in the World Series in 1980, and winning the championship that year, and that the man on the mound for the first last out in Philadelphia World Series history would be Tug McGraw…

That’s not a win for us. That’s a win for them. That’s a win for Tug, who had his shoulder fixed once he got down to Philadelphia and pitched very well for essentially the same period that Stearns caught very well. They both lasted until 1984. McGraw, by the time he was done, had passed forty. He lasted a long time. Casey Stengel would have been impressed.

Of course, we won’t take the perceptual loss without filing a protest here. We had Tug first. We had Tug plenty. Tug gave us his all before the Phillies were anything to him but another opponent. Tug said, “You Gotta Believe” to us and we never stopped believing. When Tug was diagnosed with brain cancer in 2003, in Clearwater, we felt it in our bones. When Tug died in January 2004, too soon, at the age of 59, it was our loss. It was the Phillies fans’ loss, too. It was a blow to anybody who ever connected heart, soul and baseball.

He was ours, but I guess we could share him.

Screwball, coming into my paperback possession as it did in 1975, made those Phillies years better because as long as I could read about Tug being a Met, it was as if he never totally left. Hell, the first time he came back to pitch at Shea, he instinctively headed into the home dugout following the third out of his first visiting inning. Maybe he never fully believed he wasn’t with us. I read Screwball and offered a book report on it in sixth grade. Then in eighth grade. Then in tenth grade. Then it fell off the back of my bike, and I was probably more heartbroken than I was when Tug was traded. In adulthood, I eventually stumbled into a hardcover copy in a used bookstore down the block from Wrigley Field and cherish its words if not its format to this day.

The paperback was as prized a possession as I ever had baseballwise. I prize, too, that I got to tell Tug McGraw about it. By some great turn of fortune, I was given a ticket to a baseball alumni dinner in 1999. One of the old-timers on hand was Tug, then 55. He was gregarious as ever. I went up to him with a baseball for an autograph, as was encouraged by the organizers. I’m sorry I didn’t have a copy of the book on me, any copy. But I did tell him about it. I told him I read Screwball over and over and over, and I did three book reports on it, and that I probably would have kept doing book reports on it had it not gone missing.

Tug McGraw stared into my eyes and told me, “You’re scarin’ me, man!” and laughed uproariously as he handed me back the baseball. You believe that?

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1965: Ron Swoboda

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1967: Al Schmelz

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1971: Tom Seaver

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1986: Keith Hernandez

1988: Gary Carter

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2007: Jose Reyes

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2010: Ike Davis

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2019: Dom Smith

Yes, I definitely believe that. And of all the guys who have worn the blue and orange, regardless of whatever other colors they may have worn at other times, what a great one to have met. I was crushed when they traded him, but of course it was just a warmup for what happened about 3 years later.

Well, you just scared me. I read that headline and was terrified that the dying Met ownership had just taken its revenge on New York

by trading deGrom for whatever is left of Oliver Perez. Then a) I remembered that the trade deadline is mercifully past, and b) I read a little past the headline and saw the Met For All Seasons tagline. Whew.

So to me as a kid, Tug McGraw was the guy whose appearance always meant that we were about to lose another game to the damn Phillies. Kind of Philadelphia’s version of Bruce Sutter. I kind of knew that Tug used to be a Met, but he was traded three years before I started following baseball (a.k.a. the Stone Age). And of course John Stearns was one of the favorite Mets of my childhood. So I don’t have the same perspective as you, although I guess I caught an inkling of it every time I saw Roger McDowell pitch a save against us from those same damn Phillies. (Now there was a trade beyond belief for sure.)

That’s an Olympic-level stretch. Kudos.

Hope this essay provided a taste of what Tug meant to Mets fans.

My best friend did the drawings for a daily Tugger cartoon trip called “Scroogy” that ran in many papers (I believe) for a good run. If anyone wants to buy an original he will sell I’m sure….In fact he told me last week that the one time he met Seaver he was taken into the clubhouse by Tugger.

Michael Witte is credited as the artist in the HOF piece I linked to before seeing your comment. Congratulate him on being enshrined.

I go with Scroogie as the spelling, if only because of the provenance of the comic strip that briefly ran in Newsday after the trade, and immortalized in the Hall.

Of Fame. Not Tom.

I guess the theme this week should be “Ya Gotta Bereave”

What a great piece, Greg.

Tug was the heart and soul of the 1973 Mets. He started out at 0-6 until he started believing, and he took us all with him.

I rooted for KC to win it in 1980 because I didn’t like the Phils, but in retrospect, I am glad they won it, because Tug was on that team, and it made him happy.

I was there at the 30th reunion of the 1973 team, and it was heartbreaking when they drove him to the mound in the bullpen car, as ill as he was.

Someone said, and maybe it was Tug, that when they won that WS, and he started jumping around, he was wondering where everybody was. That’s the kind of dullards who were on the Phillies at the time. You could see Boone walking slowly towards the mound after the final out.

And I DON’T like that he appears to be known more as a Phillie than as a Met, but they embraced him after his career, and the Mets did not.

[…] right and scintillate in encouraging proportions so that we find us believing in us, which is what we chronically do in September if given any reason at all. If you can remember as far back to last September (it was the one that […]

[…] Schmelz 1969: Donn Clendenon 1970: Tommie Agee 1971: Tom Seaver 1972: Gary Gentry 1973: Willie Mays 1974: Tug McGraw 1977: Lenny Randle 1978: Craig Swan 1981: Mookie Wilson 1982: Rusty Staub 1983: Darryl […]

A tale worthy of Tug, Greg. Tug was traded mere months before I became a Mets fan, and yet he is still one of my favorite all-time Mets. I read Screwball and Ya Gotta Believe–a great story in that book is how the Mets thought they’d taken the Phillies in the deal because they felt Tug was damaged goods. I owned his latter autobiography, but I took out the hardcover copy of Screwball from the Hudson Valley Library system so often it feels like mine. I wrote the SABR bio of Tug and sponsored the Tug page on baseball-reference for several years before and after Swinging ’73 came out. He is the one person I wished I’d been able to interview for that book, but fate intervened. (I’ll bet I would have scared him, too.) If there is a ballclub on another plane, I think Seaver would let Gil Hodges take the ball from him and hand it to Tug.

[…] Schmelz 1969: Donn Clendenon 1970: Tommie Agee 1971: Tom Seaver 1972: Gary Gentry 1973: Willie Mays 1974: Tug McGraw 1977: Lenny Randle 1978: Craig Swan 1981: Mookie Wilson 1982: Rusty Staub 1983: Darryl […]