The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 22 February 2021 10:06 pm Welcome to the fourth chapter of Faith and Fear’s historical countdown of the The Top 100 Mets of the 2000s. A full introduction to what we’re doing is available here. These are the more or less best Mets we rooted for as Mets fans during the decade FAFIF came to be. In honor of the 16th anniversary of our February 16, 2005, founding, we thought it would be fun (or at least not too painful) to revisit these guys and recall a little something about them.

70. VANCE WILSON, 2000-2004

Also a Met in 1999

69. JASON PHILLIPS, 2001-2004

Break glass in case of emergency, but pray the glass stays pristine. For the Mets of the early 2000s, any day when Mike Piazza wasn’t available could constitute a crisis, as three months without their superstar catcher could pretty much shut their offensive world down. From the middle of May until the middle of August in 2003, Piazza was out with a nastily torn right groin. The result could’ve been enough broken glass at Shea to keep Annie Lennox walking from here to Astoria. Sweeping in to sweep up the debris were two catchers intent on keeping Art Howe’s Mikeless ship from altogether capsizing. Vance Wilson was a defensive catcher who normally couldn’t catch enough reps behind the plate to establish himself as a fulltime receiver because, well, Piazza. But Piazza’s bad ’03 break was a decent one for Vance, netting the future Hall of Famer’s caddy a career-high 72 starts and a personal-best eight homers. Jason Phillips stood up from squatting behind both Mike and Vance that same season to take the first base starts Mo Vaughn left behind when chronic knee pain absented the slugger altogether. In more than 400 at-bats, the goggled one proved nearly a .300 hitter in 2003, good enough to earn him de facto starting catcher status in 2004 when Piazza toted his mitt over to first base. Mind you, there was no substantive substitute for the greatest-hitting catcher of all time, but when you had Wilson/Phillips, you could hold on for one more day.

68. KAZ MATSUI, 2004-2006

Something was lost in translation. Kaz Matsui was a highly regarded shortstop in Japan. The Mets decided they absolutely had to have him in 2004, never mind that the one budding star they’d introduced in 2003 was shortstop Jose Reyes. The Mets signed Matsui, shifted Reyes to second, and waited for middle-infield magic to happen. It never did, mostly because Kaz wasn’t the cause for excitement in America that he’d been back home. Diving for balls simply wasn’t something he’d done a Seibu Lion, and it showed in the National League. He also couldn’t stay healthy consistently, and that, too, tried patience within the not-always-reasonable precincts of the Mets fan community. By 2005, Matsui was assigned second, which improved shortstop at once (becoming Jose’s dominion again), but Kaz continued to be plagued by injuries, slumps and a general level of discomfort he could never shake. Still, he did display speed; could get hot; and had the strangest knack for whacking the very first pitch he saw in every season he was a Met for a home run, one of them an inside-the-parker. If only he’d led off and left town for twelve months, Kaz Matsui would go down as a legend rather than a cautionary tale.

67. DAMION EASLEY, 2007-2008

No Mets fan would argue that every Met in 2007 and 2008 didn’t deserve a trip to the postseason, but if you were willing to look past the uniform, there was one Met you had to root hardest for to reach October. After fifteen seasons of service in other outposts, Easley found himself a 37-year-old veteran missing one appearance in an otherwise honorable career: not one single second in postseason play. Damion joined the Mets following their 2006 playoff run, ready to back up at almost any position and ride the Flushing wave into autumn. The former AL All-Star did his part well enough, knocking in the occasional big run and filling in steadily, particularly at second base. But the team he joined was not the team it became, and after near-misses (to put it kindly) in September 2007 and September 2008, Damion Easley finished his career with 1,706 regular-season games played and zero in the postseason, at the time the most for any player whose career included the Wild Card era.

66. GARY SHEFFIELD, 2009

Sooner or later, it had to happen. When your uncle is Dwight Gooden, when your profession is baseball and when your talent is undeniable, your destiny says you will land on the New York Mets. Mostly it was the Doc connection that always made Gary Sheffield loom as a hypothetical Met trade target. He had played for seven other franchises over 21 seasons until the storyline got its inevitable final paragraph, with Sheff signing as a Met on the eve of the opening of Citi Field in 2009. The Mets were a little short in the outfield, so the 40-year-old found a temporary home in left. Almost as soon as he got to Queens, Gary hit the 500th home run of his illustrious career, making him the first to reach that high a milestone in a Met uniform. It also meant he’d joined Doc’s old teammate Rusty Staub in the palmful of players who’d homered before turning 20 and after turning twice that. He’d keep up his powerful ways for a few months before aging into retirement.

65. BRUCE CHEN, 2001-2002

The eyes of a city were upon a newcomer the night of September 21, 2001. The Mets were facing the Braves in the first baseball game New York was hosting since the terrorist attacks of ten days before. Was it too soon? It couldn’t be for Bruce Chen, whose job it was to throw that Friday’s first pitch and resume the path to municipal normality. The ex-Brave, acquired from the Phillies in July, did his part splendidly, giving up no earned runs over seven tense innings, setting the stage for Mike Piazza’s bat to take care of the drama and catharsis in the eighth.

64. LASTINGS MILLEDGE, 2006-2007

Reach out and touch Lastings Milledge. If you sat in the first row of the right field stands on the Sunday afternoon the Mets’ first-round draft pick from 2003 hit his first major league home run, you had an excellent chance of personally making contact. In the bottom of the tenth inning on June 4, 2006, with a runner on and the Mets trailing by two runs, Lastings went deep to tie the Giants and extend the action. Jogging back to his position, he exchanged casual high-fives with any fan who wanted them. A baseball generation or so later, he’d likely be marketed as the kind of player the sport desperately needed. Back then, before anybody thought to celebrate let alone retweet a bat flip, the old guard (manager Willie Randolph especially) tut-tutted. Perhaps if Milledge had hit and hustled more consistently, he would have been welcomed more heartily into the fraternity. Later in 2006, Lastings would be greeted by a sign at his locker that warned him to “KNOW YOUR PLACE, ROOK.” When his place was in the starting lineup, he could demonstrate why he was drafted so high, but any chance Lastings would put all of his tools together in New York was short-circuited following the 2007 campaign when he was traded to Washington for Ryan Church and Brian Schneider.

63. RAMON CASTRO, 2005-2009

The easing out of a legend is never easy, though the process that edged Mike Piazza toward the Shea Stadium exit in the final year of Mike’s long-term contract seemed a little less upsetting that it could have been on those days Piazza’s position was in the capable hands of Ramon Castro. Putting down targets to the approval of new Met ace Pedro Martinez, Castro made himself indispensable to the hopes of the 2005 Mets, getting into almost a hundred games and blasting off Ugueth Urbina the season’s most important home run, a three-run job that vaulted the Mets over the Phillies on August 30, moving New York to within a half-game of the NL Wild Card. September contender aspirations at Shea soon disintegrated, but Castro cemented his role as the Mets’ main backup catcher for the next several seasons of wire-to-wire contention.

62. PAT MAHOMES, 2000

Also a Met in 1999

Pat Mahomes was a long-relief revelation during his first season as a Met in 1999. Come 2000, his role would expand to see the veteran start five times, including a brilliant 5⅔-inning outing in which he gave up only two singles and no runs to the Dodgers en route to a 1-0 victory that became the Mets’ eighth straight win. But maybe what Mahomes should most be admired for from 2000 was his prescience in bringing his namesake son to Shea to shag flies during the postseason. Young Patrick, then five, was photographed warming up alongside Mahomes’s staffmate Mike Hampton in the leadup to World Series action. It’s a picture that would circulate widely and give Mets fans pride some twenty years later as Patrick grew up to lead the Kansas City Chiefs to an NFL championship in Super Bowl LIV.

61. DARREN OLIVER, 2006

If the Mets’ collective back wasn’t against the wall, it wasn’t too many inches from cold concrete when one Met stepped up to, as the saying goes, take one for the team. In Game Three of the 2006 NLCS, the club had fallen disturbingly behind the Cardinals in the third inning. Darren Oliver, who’d been the long man for Willie Randolph all year, entered in the second inning. He’d stay on the mound through the seventh, allowing no earned runs in his six innings of work, preserving the rest of the Mets’ pen so they could rest and be ready for the must-win games that lay ahead.

by Greg Prince on 20 February 2021 6:11 pm Welcome to the third chapter of Faith and Fear’s historical countdown of the The Top 100 Mets of the 2000s. A full introduction to what we’re doing is available here. These are the more or less best Mets we rooted for as Mets fans during the decade FAFIF came to be. In honor of the 16th anniversary of our February 16, 2005, founding, we thought it would be fun (or at least not too painful) to revisit these guys and recall a little something about them.

80. JEFF FRANCOEUR, 2009

Also a Met in 2010

79. RYAN CHURCH, 2008-2009

The decade of the 2000s was not one for consistency in right field. Just about every year somebody else was penciled in as the prevailing “9” in Met scorecards. Nor was this a new trend; the position had gone no more than temporarily occupied since the 1990 departure of Darryl Strawberry. As the void approached its 20th anniversary, the Mets attempted to fill it with a couple of very different personalities and skill sets. In 2008, the club welcomed Ryan Church aboard. Low-key in demeanor, Ryan was capable of getting into a good groove, but is mostly remembered for a bad break, sustaining a particularly debilitating concussion compounded when the Mets were slow to add him to the disabled list, choosing instead to have him fly many hours with the team. (Some protocol.) Midway through 2009, the Mets said “amen” to trading Church to Atlanta, swapping him straight up for Jeff Francoeur, erstwhile Braves phenom. He could still throw well, sometimes hit and make the occasional big play, never failing to smile in the bargain. Vivaciousness wasn’t Francoeur’s problem. Frenchy, however, rarely met four balls he liked, tamping his on-base percentage down somewhere in the neighborhood of his batting average. The Mets would trade him before 2010 ended.

78. BUBBA TRAMMELL, 2000

There is a parenthetical nature to Bubba Trammell’s achievements during his brief time as a Met. In his very first at-bat after coming over in a midseason trade from Tampa Bay, Trammell launched a three-run homer. In his final game, which happened to be Game Five of the 2000 World Series, he scored the tying run in the inning the Mets took a 2-1 lead off Andy Pettitte. In between? Bubba was not asked to do all that much. Bobby Valentine started him only seven times after his powerful late-July debut, and his insertion in the World Series lineup — Trammell’s only postseason start — was something of a desperate measure given that the Mets were down three games to one. The Mets traded him to San Diego the following December, and Trammell would give New York a cause for regret. As a Padre in 2001, Bubba drove in 92 runs, 36 more than any Met outfielder delivered.

77. ANGEL PAGAN, 2008-2009

Also a Met from 2010-2011; No. 30 Met of the 2010s

For four seasons, the top of the Mets’ order flashed a NO VACANCY sign to any player with leadoff aspirations. Jose Reyes had moved in to stay in 2005 and was beyond budging until an injury took him out for the bulk of 2009. Something similar could have been said of center field, which was the exclusive province of Carlos Beltran over the same time period until the ’09 DL decided it needed another high-profile denizen. Enter Angel Pagan, whose own first Met season of 2008 was shortened by a mishap with a side wall. As Jerry Manuel’s contingency center fielder and first batter of practically every game across the second half of the season, Pagan showed what he could do. Angel batted .306 for the year, piled up eleven triples and made a breathtaking trip around the bases via a leadoff inside-the-park home run in the bottom of the first inning off Phillies starter Pedro Martinez in the former Met ace’s first Citi Field appearance (it was the same game Jeff Francoeur ended by lining into an unassisted triple play, so maybe it wasn’t the most breathtaking moment of the day).

76. DAE-SUNG KOO, 2005

Let’s be straight: nobody cares what kind of relief pitcher Dae-Sung Koo was in the one season the southpaw was a Met, so we’ll dispense with a reading of the statistical minutes and get right to the main course of why Mr. Koo’s tenure will forever resonate in Subway Series lore. On May 21, 2005, Dae-Sung made his second plate appearance. His first, earlier in the week, involved the reliever from Korea getting his at-bat over with as harmlessly as possible by standing far back in the box and watching four pitches (three of them strikes) zip by. Koo hadn’t ever batted professionally in Asia, and he wasn’t going to start now. Yet facing no-doubt Hall of Famer Randy Johnson, in a lefty-vs.-lefty matchup that prohibitively favored the lefty on the mound, the heretofore reluctant batter swung and proved that if you make contact, you never know. You would have never known that Mr. Koo could double off the Big Unit, but he did it. Mr. Koo’s wild ride continued two pitches later. Jose Reyes bunted. The play went to first. The runner went to third and kept going. In the oddest sacrifice bunt of the decade, Mr. Koo slid home safely under Jorge Posada’s tag. Shea Stadium figuratively exploded in rapture. Maybe literally, too. Dae-Sung Koo never batted in the major leagues again. He didn’t have to.

75. SHAWN GREEN, 2006-2007

Dominoes tumbled in 2006. A reliever got hurt. The Mets thus needed another reliever, so they traded their right fielder. They thus needed another right fielder, so they traded for Shawn Green, a player a little more famous than he was productive by the time he arrived in Flushing. The best-hitting Jewish big leaguer since the legendary Hank Greenberg made matzo meal out of American League pitching in the 1930s, Shawn and New York might have been a match made in heaven (or at least at a Seder) had the Mets traded for him a few years earlier. Between 1998 and 2002, Green averaged 112 RBIs annually. Though Shawn wasn’t quite that kind of slugger anymore, he did man right field well enough to help his new team nail down their first division title in 18 — lucky chai — years and unleashed the throw that set off the two-men-out double play at the plate that defined Game One of the NLDS versus the Dodgers, one of Shawn’s old teams.

74. JAE SEO, 2002-2005

Jae Seo’s reward for doing what was asked of him was a pat on the back and a ticket out of town. After 52 starts in 2003 and 2004, Seo began 2005 as the odd arm out of Willie Randolph’s rotation. Once back in, Jae gave the new manager as good an outing as could have been desired, going seven innings, striking out eight and giving up only one run against the Phillies in an eventual 3-2 Mets win. His reward? A planned numbers-driven demotion to Norfolk. Seo wouldn’t be back in New York until August, continuing on to an 8-2 record with an ERA of 2.59. The Mets were so grateful for his service that they traded him in January 2006 to Los Angeles.

73. RICHARD HIDALGO, 2004

When the Beach Boys sang about having fun all summer long in 1964, they could have dedicated those sentiments to Richard Hidalgo. Make it a long-distance dedication, because it wouldn’t have made any sense until they saw what Hidalgo did as a Met in July of 2004, a couple of weeks after the Mets picked the veteran outfielder up from the Astros in exchange for David Weathers. Did somebody say weather? Hidalgo must’ve really enjoyed the way the temperatures rose in New York in July, for that was the month Richard began by ripping a baseball a day over a fence for five consecutive days. No Met had executed that kind of home run streak before, no Met has matched it since. From June 20 through September 16, roughly following the contours of the summer solstice, Richard went deep 21 times (including five much-appreciated bombs off Yankee pitching). The Summer of ’04 was Hidalgo’s season within a season and it was a sweet season, indeed.

72. VICTOR DIAZ, 2004-2006

Nothing raises the spirits of a dejected fan base like thinking a gem is being uncovered right before their eyes. Victor Diaz may have come to professional baseball as a 37th-round Dodger draft choice, but by the time the Mets promoted him in September of 2004, fresh off a 24-home run campaign at Norfolk, the outfielder appeared ready to shine. His first homer came on a Saturday at a Shea swarming with Cubs fans who found themselves suddenly silenced when rookie Diaz went deep in the ninth off LaTroy Hawkins to tie the score and effectively quash the visitors’ playoff hopes (the Mets would win in eleven on Craig Brazell’s only big league bomb). That Victor had grown up in Chicago made it a great story. That he bore a passing resemblance to Manny Ramirez vaulted him to the top of the Mets prospect list, at least in the minds of fans who could only imagine their fourth-place club harboring that kind of elite slugger. Omar Minaya, who took over as GM soon after, was similarly sanguine toward the new kid in town. “I see Victor as one of the three players who are at the core of our future,” he said, lumping Diaz in with Jose Reyes and David Wright. The mini-Manny framing wore off as projections for Victor Diaz’s status as the next great Met power bat proved overly optimistic. Still, there exists within the Met annals something recognized as The Victor Diaz Game, and not every callup produces that kind of gem.

71. MIKE JACOBS, 2005

Also a Met in 2010

From filling a roster spot to tearing the retractable roof off Bank One Ballpark, Mike Jacobs enjoyed the ride of his life all in the span of about a week. Slated to be sent back to Triple-A after not playing a lick for several days, the seven-season farmhand was granted a pinch-hit at-bat on the wrong end of a Shea Stadium blowout. He turned it into a three-run homer and a major league reprieve. Kept on the team as the Mets flew to Arizona, Mike practically flew southwest without a plane. At the end of a thudding four-game series sweep versus the Diamondbacks (the Mets plated 39 runs), Mike’s career stat line included four homers, nine ribbies and a .500 batting average. Norfolk was clearly in his rearview mirror. Staying in the lineup for the rest of the season, Jacobs ended his abbreviated 2005 with eleven home runs in all and a presumed reservation to play first base for the 2006 Mets. He was indeed a starting first baseman in the NL East that next season, but it was for the Marlins, who gladly accepted Mike in the trade package that sent Carlos Delgado to Queens.

by Greg Prince on 19 February 2021 5:08 pm The Friday bulletin that the Mets were signing Taijuan Walker brought me back to something Roger Angell wrote forty years ago. Anybody who puts me in mind of something Roger Angell wrote anytime is all right by me.

This particular Angell observation came from the summer of 1981, during the baseball strike, and lives on in the book Late Innings. Roger and his wife were sitting in the back of a Manhattan cab, being driven uptown after a night out in the Village. The driver had the radio on as the clock ticked midnight. The station to which the taxi was tuned was running the news, during which the story that was missing grabbed the writer’s attention.

[T]here was no baseball in it. I had been waiting for those other particular sounds, for that other part of the summer night, but it was missing, of course — no line scores, no winning and losing pitchers, no homers and highlights, no records approached or streaks cut short, no “Meanwhile, over in the National League,” no double-zip early innings from Anaheim or Chavez Ravine, no Valenzuela and no Rose, no Goose and no Tom, no Yaz, no Mazz, no nothing.

Programming along the lines of a top-of-the-hour update just ahead of the Milkman’s Matinee on WNEW-AM may be practically impossible to stream on today’s devices (and what’s a night out?), but I can hear echoes of what Roger couldn’t hear during the strike, and I can hear them because Taijuan Walker has existed to me mostly, until this free agent bargaining season, as a name that would float across my baseball subconscious. Maybe not delivered in an authoritative newscast of yore, but likely to pop in and out of whatever one of our announcers was telling us was going on elsewhere. Something as simple as “Taijuan Walker going for the Diamondbacks…” The righty pitched twice, seven and four years ago, against the Mets. In 2014, he was on the other end of Bartolo Colon’s perfect game bid at Seattle. Yet I remember him better as a quickly cited data point.

Now Taijuan shall fling among us, his identity not part of between-pitches patter but embroidered within the mood-determining balls and strikes, serving as the difference between our frustration and elation. We know you now, Chef Walker. We can be judgmental, but we’re happy to have you. Maybe a couple of those homemade tacos, too.

Likewise, we’re enthusiastic to step right up and greet from six feet of distance every prospective starting pitcher loosening up in Mets garb these February weeks, the fellas creating the content that fills the mundane days that follow the evanescent adrenaline rush of report date. Marcus Stroman has returned from Optoutopolis, ready to assume full occupancy of the rotation’s Long Island seat. Carlos Carrasco is bringing his Cookie sweetness and inspiration to our cause. Joey Lucceshi is applying his semi-familiar first name to our historical record. Jordan Yamamoto is no longer carrying the scent of a Marlin. David Peterson is lowering his number from 77 to 23, perhaps in tribute to Doug Flynn, but probably not. Aaron Loup’s ready to open, then unwind. Sean Reid-Foley offers potentially deeper depth than Corey Oswalt, but both offer a right hand if needed.

If starting pitchers come, it must mean starting pitchers go; it’s the way of the Grapefruit League. Steven Matz is in Dunedin, claiming to be thrilled to be a Jay. Michael Wacha’s in Port Charlotte, making us think he’s got something in the tank if Tampa Bay has made him a Ray. Rick Porcello’s in limbo but could be en route to Lakeland to roar as a Tiger once more. Noah Syndergaard remains native to Port St. Lucie, but he’s several months from donning his shirt in anger. Reaching back a little further in retro Met pitching lore, Zack Wheeler’s in Clearwater with the Realmuto-impaired Phils, Matt Harvey’s landed in Sarasota attempting to impress a flock of desperate Birds, and the aforementioned Colon, 47, is giving it another go in the Mexican League…which is only slightly less unsurprising than Oliver Perez, 39, taking a left turn back to Cleveland by way of Goodyear, Ariz.

And speaking of good years, Jacob deGrom, the best pitcher in baseball Right Now, says he wishes to remain a Met for the rest of his life. That’s pitching news that’ll make a Mets fan ask the driver to turn up the volume, please.

by Greg Prince on 18 February 2021 12:45 pm Welcome to the second chapter of Faith and Fear’s historical countdown of the The Top 100 Mets of the 2000s. A full introduction to what we’re doing is available here. These are the more or less best Mets we rooted for as Mets fans during the decade FAFIF came to be…and the decade future former Mets farmhand Tim Tebow won the Heisman Trophy. In honor of the 16th anniversary of our February 16, 2005, founding, we thought it would be fun (or at least not too painful) to revisit these guys and recall a little something about them.

90. CARLOS GOMEZ, 2007

Also a Met in 2019

He had youth, not much more than 21 years of it upon his May 2007 promotion from New Orleans. He had speed, as evidenced by the 12 bases he stole in limited action and the plays he made in left and right. He had the potential of a Baseball America and Baseball Prospectus Top 100 prospect. It was enough to make Mets fans salivate over what Carlos Gomez might do in the years ahead. It was also enough to make the Minnesota Twins want him as the biggest name in a package of promising players before they would send Johan Santana to New York. Go-Go would go on to a fairly stellar career that a dozen years after beginning at Shea Stadium would end, poetically enough, at Citi Field.

89. NICK EVANS, 2008-2009

Also a Met from 2010-2011

That rare Double-A callup, Nick Evans burst to first-day prominence in May of 2008, debuting by doubling not once, not twice, but thrice within the expansive confines of Coors Field. Starting a big league slate with a 1.500 slugging percentage will raise expectations, and while Nick couldn’t keep up the pace (who could?), his bat became reliable enough for Jerry Manuel to depend upon down the stretch of Evans’s rookie season. The manager trusted him as his starting left fielder the final day of Shea Stadium, with a playoff spot not to mention history on the line.

88. BRIAN STOKES, 2008-2009

87. LUIS AYALA, 2008

How do you replace one of the top closers of his generation? When Billy Wagner was lost to an injury in early August 2008, not to return to the mound for more than a year, Omar Minaya stitched a bullpen’s back end out of two relievers heretofore off the Metsopotamian radar: Luis Ayala, traded over from the Nats ,and erstwhile Devil Ray Brian Stokes, most recently a Triple-A Zephyr. Together Ayala (a win and seven saves in the course of 11 appearances) and Stokes (an ERA under 1.00 over 13 straight outings) Plan B’d the Mets through their first Wagsless month, fort largely intact. Come the latter half of September, all Mets relief bets were off, but the duo did keep the Mets’ pursuit of the postseason a little more alive that might have been anticipated when Wagner went down.

86. MARK GUTHRIE, 2002

Bad lefthanded relieving can really kill an otherwise good season. Good lefthanded relieving can only do so much for an otherwise bad season, but during 2002, when all about him crumbled, Mark Guthrie held up his share of the Shea bullpen infrastructure. Lefty batters couldn’t touch the veteran (.187) and righty batters homered off him only once in 94 at-bats. A mere six of 37 runners Mark inherited scored. His 68 appearances yielded a nifty ERA of 2.44. The 2002 Mets failed as a unit, but in his only year in the orange and blue, Guthrie was well within his individual rights to declare, “I got my men.”

85. KRIS BENSON, 2004-2005

Although Kris Benson was the No. 1 pick in the nation when the Pirates drafted him in 1996, over time he might have grown used to being overshadowed. That will happen when you pitch for a while on a staff anchored by eventual Hall of Famers Pedro Martinez and T#m Gl@v!ne, but most of that was a symptom of being married to the former Anna Adams, a woman who had no problem attracting attention on her own. Though Kris was a name pitcher when the Mets swung a deadline trade for him in 2004, the acquisition that brought him to New York became a footnote to the other deal the Mets made the same day, the one that sent their own No. 1 draft pick, Scott Kazmir (chosen 15th overall in 2002) to Tampa Bay for Victor Zambrano. While Mets fans bemoaned the surrender of a highly touted left arm for one that was wild and, ultimately, irreparable, the reception for righty Benson was applauded politely and welcomed without much fanfare. Getting Anna seemed the bigger story during most of Kris’s competent two-season Shea stay, especially when she dressed as Santa’s slinky helper for the team’s holiday party for kids. Kris was Santa; nobody noticed. The getup may not have been deemed family-appropriate outside the Benson household. Ho-ho-no, said the Mets, trading Kris to Baltimore less than a month after Christmas. The Bensons are no longer a couple, even if they now and again show up in the media as an item.

84. MO VAUGHN, 2002-2003

83. ESIX SNEAD, 2002; 2004

82. OMIR SANTOS, 2009

A home run can travel far and, in the mind’s eye, it can keep going into legend. Mo Vaughn hit more than a few as a Met, if not nearly as many as were hoped for when Bobby Valentine campaigned to acquire him from Anaheim after Vaughn was inactive for a year. The former American League MVP socked 29 homers for New York before his arthritic knee sidelined him for good. The most vividly memorable of them was one that soared an estimated 505 feet and glanced off the massive Budweiser sign that dominated the Shea scoreboard, the consensus choice for most powerful home run any Met ever hit, at least among those preserved on video. Vaughn’s bomb of June 2002 came in a losing cause, which can’t be said of Esix Snead’s lone homer, whacked the same season, well after the Mets had dropped out of contention. But on the September Saturday night when Snead stepped forward, the recently promoted Esix put his bat and a win on the Met map, launching a three-run eleventh-inning job that beat the Expos and briefly cheered Flushing toward the end of an otherwise disconsolate year. Fast-forward to the Citi Field era and turn north toward Boston, where unsung catcher Omir Santos poked a Jonathan Papelbon pitch just above Fenway Park’s Green Monster to engineer a dramatic 3-2 victory that happened in May 2009 but is probably airing again right this very minute as a Mets Classic on SNY.

81. FERNANDO TATIS, 2008-2009

Also a Met in 2010

The last time the baseball world had given a ton of thought to Fernando Tatis, he was hitting two grand slams in the same inning off the same pitcher, future Met Chan Ho Park. This was 1999, when Tatis was a Cardinal en route to a bang-up season that featured 34 home runs and 107 runs batted in along with a newborn son he named after himself. It was a great way to usher out a century, but Tatis the elder would fade from baseball consciousness as the 2000s progressed. He didn’t play professionally in 2004 and 2005 and was marooned in the minors for the entirety of 2007. In 2008, at the age of 33, Fernando made a comeback with the Mets, and the Mets couldn’t have been happier. Looking to keep playing so he could help fund the building of a church in his Dominican Republic hometown of San Pedro de Macoris, his return proved a blessing in Flushing. The veteran hopped off the scrapheap to pile up valuable hits, none more sorely needed than the walkoff double he delivered in the bottom of the twelfth on May 28 to defeat the Marlins and push the scuffling Mets in the general direction of contention. By season’s end, Tatis had garnered Comeback Player of the Year honors. In the 2020s, Fernando is better known as father to his lavishly compensated namesake son, who currently stars for the Padres in a city appropriately nicknamed Slam Diego. Power apparently runs in the Tatis blood.

by Greg Prince on 17 February 2021 2:38 pm Welcome to the first chapter of Faith and Fear’s historical countdown of the The Top 100 Mets of the 2000s. A full introduction to what we’re doing is available here. These are the more or less best Mets we rooted for as Mets fans during the decade FAFIF came to be. In honor of the 16th anniversary of our February 16, 2005, founding, we thought it would be fun (or at least not too painful) to revisit these guys and recall a little something about them.

100. LUIS CASTILLO, 2007-2009

Also a Met in 2010

Luis Castillo was a .302 hitter across 142 games in 2009, and if you gloss over Luis’s 51st game of that year, June 12 at Yankee Stadium…specifically that game’s bottom of the ninth, when the three-time Gold Glove second baseman never quite settled under a two-out pop fly with runners on first and second who took the job description of “runners” literally…and if you forget that Luis attempted to grasp that pop fly with one hand, dropped it, and allowed those two runners to score, turning a nervous 8-7 Mets lead into a grisly 9-8 Mets loss…well, you might remember Luis Castillo hit .302 across 142 games in 2009. But that’s not what you remember when you think of Luis Castillo, is it?

99. FERNANDO NIEVE, 2009

Also a Met in 2010

The afternoon after Luis Castillo failed to use two hands to secure a third out in perhaps the most embarrassing Subway Series humiliation since the Mets began playing the Yankees for real in 1997, Fernando Nieve emerged from the bullpen to make his first start of the season and rescue Metsopotamia’s self-esteem from the abyss. Six-and-two-thirds innings of two-run ball steered the Mets toward a much-needed 6-2 win in the Bronx, and furnished an even more-needed reminder that tomorrow is inevitably another day.

98. CORY SULLIVAN, 2009

Citi Field was ushered into existence as a great park for triples, therefore a perfect park for perennial leadoff hitter Jose Reyes. Yet nobody presented more compelling evidence that the dimensions could create a little old-time basepaths excitement than Cory Sullivan, an erstwhile Rockies outfielder who joined the injury-riddled Mets in July and ran relatively wild, posting five three-baggers in a 32-game span. With Reyes confined to the DL, Citi Field seemed to have been built specifically for Sullivan, who finished second on the club in triples in less than half-a-season on the roster. Sullivan, however, ran to Houston as a free agent in the offseason following 2009 and never played at Citi Field again.

97. ROBERTO ALOMAR, 2002-2003

The phrase “won the offseason” never resonated more strongly than in December of 2001 when the Mets pulled off what appeared to be a heist, trading for surefire future first-ballot Hall of Famer Robbie Alomar. Alomar was a huge part of winning teams in Toronto, Baltimore and most recently Cleveland. Though he was heading into his age 34 season, he’d shown no signs of slowing when he was 33, having hit .336 in ’01 with 20 homers, 30 steals and well over 100 runs scored. None of the players given up to get him — including megahyped outfield prospect Alex Escobar— would come back to substantively haunt the Mets. For good measure, Alomar had fond childhood memories of Shea Stadium, with his dad Sandy having played for the Yankees there the two seasons Yankee Stadium was being refurbished (after playing briefly for the Mets before Robbie was born). We’re talking about the perfect offseason trade here, except for one stubborn detail: Roberto Alomar was a bust as a Met. Perhaps no high-profile Met acquisition was more disappointing. His range disappeared. His hitting evaporated. He fought for what appeared to be a silly reason with one of his teammates (Roger Cedeño, who reportedly teased him over what young Alomar looked like on his rookie card). After a dozen consecutive All-Star seasons, not even Alomar’s AL reputation could win him election to the NL squad. He fell far and fast and was traded by the middle of 2003, the second consecutive season when Alomar’s Mets had inverted from promising in winter to unwatchable by summer. Robbie did play almost every day, did collect his 2,500th hit in a Mets uniform, and “NEW YORK, N.L.” does appear on his Hall of Fame plaque, but the sour aftertaste of his term in Flushing doubtlessly contributed to pushing his election off to a second ballot. Elaborated no-voter Marty Noble in 2010, “During his 222-game tour with the Mets, Alomar repeatedly spit in the face of the game by playing with conspicuous apathy.”

96. ANDERSON HERNANDEZ, 2005-2007; 2009

Man, could this kid play defense. Enough so that after his widely craved late-season 2005 promotion from Norfolk revealed his second base skills, his slow-to-connect bat (0-for-17 before a single in the ninth inning on Closing Day) was overlooked or at least forgiven. Penciled into lineups alongside David Wright (22), Jose Reyes (22) and Mike Jacobs (24), Anderson Hernandez, a month shy of 23 upon his arrival, was going to be part of a tantalizingly youthful infield that would catapult the Mets to full contention in 2006. Anderson proceeded to play his role as directed, flying through the air with the greatest of ease as the ’06 Mets elevated themselves above the NL East pack by mid-April. Unfortunately, Hernandez’s glove, as well as the rest of him, was put on the shelf by a bulging disc in back, something you wouldn’t intuit would sideline an athlete so young. Anderson wound up missing the bulk of that Eastern Division championship season and was never the Mets’ everyday second baseman again. Oh, but how he could field when he was.

95. NELSON FIGUEROA, 2008-2009

With the eighteenth pick of the thirtieth round of the 1995 amateur draft — the 833rd pick overall — the New York Mets selected Nelson Figueroa, righthanded pitcher from Brandeis University. Born and raised in Brooklyn as a Mets fan, this draft pick was a story set to write itself. Nobody, however, would have guessed it would be a longform story, as Figgie would pass through five other major league organizations, endure labrum and rotator cuff surgery, miss an entire professional season, tour Mexico and Taiwan in an effort to regain notice, and require thirteen years before making his Mets debut. Was it worth the wait? Considering it took place at Shea Stadium in front of at least a hundred friends and family members, involved a perfect game bid of 4⅔ innings, and resulted in a win for the 33-year-old journeyman, one would have to say it was. Nelson was certainly satisfied. “It was everything I dreamed it would be,” he said that April night in 2008. “To come back in baseball and pitch for my hometown team, this journey has been incredible. It’s storybook-like.” Though the rest of Figueroa’s story in Flushing lacked plot development nearly as compelling (he went 6-11, starting 16 games over two seasons), his final Mets chapter put a bold period on his stay, as he shut out the Astros on a four-hitter in Game 162 of 2009.

94. DAVID CONE, 2003

Also a Met from 1987-1992

David’s 21st-century Mets stint was pure anaConeism. He’d been gone from the Mets for more than a decade and had embedded himself in New York baseball lore more for his world champion American League exploits when he was convinced by a couple of similarly venerable pitchers, John Franco and Al Leiter, to come out of one-year retirement and come to Port St. Lucie to give baseball one more throw. Lo and behold, the 20-game-winner from 1988 had enough left to make Art Howe’s rotation and start the season’s fourth game. Anachronistic or not, 40-year-old Cone turned back the clock that frosty Friday night, blanking the Expos for five innings, ending his Mets return with a flourish out of a storied Flushing past, striking out Vladimir Guerrero with two runners on to put a Conehead on his return engagement. By May, David would re-retire, assigning his Mets presence once and for all to the past.

93. SHAWN ESTES, 2002

On June 15, 2002, Shawn Estes threw seven dominating innings, shutting out the hated Yankees at Shea Stadium while striking out eleven of them and, for good measure, whacked a two-run homer off despised visiting starter Roger Clemens. All of it culminated in an 8-0 thrashing that under 99 of 100 circumstances would have totally delighted every Mets fans in existence, especially considering Clemens also gave up a home run to his personal nemesis (and vice versa) Mike Piazza. But this was the hundredth circumstance, the one that had the Rocket showing his ample ass at the plate against the Mets for the first time since he threw a bat handle at Piazza in the 2000 World Series. Mets fans had been yearning for revenge against Clemens ever since. The chance to get even fell into the left hand of Estes, a starter in good standing for the 2000 San Francisco Giants and, as such, completely detached from the furies of two Octobers earlier. Estes threw in the general direction of Clemens’s backside anyway. He missed. Nobody of a Met stripe was happy. The 8-0 win was thus viewed as consolation rather than conquest. Moral? No good deed goes unpunished (and vice versa).

92. ERIC VALENT, 2004-2005

Eric Valent had singled in the second inning at Olympic Stadium on July 29, 2004. He doubled in the third and homered in the fifth. One particular type of base hit shy of the cycle, Valent unwittingly channeled the spirit of Alexander Hamilton as eventually channeled by Lin-Manuel Miranda. Eric Valent was not throwin’ away his shot. Sure enough, when he lined a Roy Corcoran pitch down the right field line at the Big O, Eric took his shot, and it was as big as the one Billy Joel had written about a quarter-century earlier. First base? Not big enough. Second base. Still not big enough. Third base? That’s the shot Valent was taking. He ran and ran and never stopped until third base was in sight…and he made it, collecting the eighth cycle in Mets history. Sure as shootin’, it was worth a shot.

91. ROBINSON CANCEL, 2008-2009

Talk about keeping your powder dry. Robinson Cancel played in fifteen games for the Milwaukee Brewers in 1999 and then spent the next eight seasons in the minors, affiliated and otherwise. He re-emerged a major leaguer in June of 2008 with the Mets, who at the time groped for anybody who could give them a quality at-bat. In the nightcap of an Father’s Day makeup Interleague doubleheader, Robinson pinch-hit for Pedro Martinez and introduced himself as the Texas Rangers’ daddy, stroking a tiebreaking two-run, sixth-inning single to center that proved the difference in a critical 4-2 Mets win. It didn’t save Willie Randolph’s job — he was fired as manager late the next night in Anaheim — but it did serve to keep Cancel’s number handy should the Mets need another big AB later in the season. On September 25, Randolph’s successor Jerry Manuel started Robinson behind the plate as the Mets pursued a playoff spot. Once again, Cancel culture prevailed, this time in the eighth when Robinson singled home another Met reclamation project, Ramon Martinez, with the run that knotted the Cubs at six. The Mets would win an inning later, forging their final Shea Stadium walkoff triumph. For someone who showed up in big league box scores approximately every decade, Robinson Cancel certainly knew how to make his appearances count.

by Greg Prince on 16 February 2021 4:44 pm Today is the sixteenth anniversary of the founding of Faith and Fear in Flushing, which puts our start date at February 16, 2005, which isn’t exactly news. It was news to Jason and me sixteen years ago today, but the outer world of Mets fans who liked to read wouldn’t instantaneously discover us. That took at least a week. Of course when you write something called a blog, you’re always being discovered by somebody for the first time…which is a nice way of saying most people out there who might enjoy what you’re doing have likely never heard of you, but you keep doing it for sixteen years and then some because you really enjoy doing it.

When the Mets fancied themselves as New and our brand of media did, too. Like I said, no news there via a sixteen-year-old scoop, but I did recently notice something specific about the Metsian moment when we launched. It was right in the baseball-middle of the decade known popularly as the Aughts, though I never went for “the Aughts” as a name. I called them “the Ohs,” though I don’t think anybody else did. I’m willing to go with the 2000s, the caveat being that for Mets baseball purposes, they commenced at the beginning of the 2000 season and ended at the conclusion of the 2009 season. If you’re one of those “but there was no year zero” pedants who revels in pointing out decades and centuries can’t possibly begin in a year ending with an oh or an aught, please save that hardy decennial nitpick for January 1, 2030, when we’ll briefly entertain and reject it again.

February 16, 2005, meant five Met seasons of the 2000s had been played and five Met seasons of the 2000s had yet to occur. We were apparently taken enough by what we had experienced in the first five — 2000 through 2004 — to want to share with an audience larger than just us what we thought as the beginning of the next five crept into view. Not that the previous five seasons represented the best five-season span in Mets history. No five-season span in the past thirty years can be said to have constituted the best five-season span in Mets history. But for five seasons, those five seasons were ours. Jason and I went to a load of games together from 2000 to 2004, listened to or watched on radio or TV just about all the rest of them, and wrote to each other not a few words based on what we’d seen.

For the record, the 2000 Mets won a pennant and their next four successors did no such thing. Relatively few bursts of Met competence sustained themselves from 2001 to 2004, though there were some good days and nights in there, enough to keep us coming back long enough land here on 2/16/2005 and take it from there. In the latter half of the 2000s — 2005 through 2009 — there was some semblance of lasting Met success, certainly enough to make us want to keep going to games, listening to them, watching them and, without pause, writing about them. The Mets would fall apart as late as possible in a few of those years before dropping the pretense altogether and coming completely apart several dreadful months before the baseball decade ended.

Win or lose, it was all blogworthy for a couple of Mets fans who like to write, and so we have continued on, currently blogging inside of a third calendar decade. The 2020s have yet to really take shape (let’s hope). The 2010s we covered with due hindsight when the 2020s loomed as the immediate if incredibly unknowable future. That leaves us the 2000s.

Leaves the 2000s for what? Why, for a full-fledged Faith and Fear in Flushing retrospective of its birth decade: The Top 100 Mets of the 2000s, considering the 275 players who played as Mets between March 29, 2000, and October 4, 2009, and ordering what we shall refer to the “best” of them from 100 to 1, countdown (or countup) style.

The parameters follow what we did at the tail end of 2019. Rankings will be based on recollections and research, leaning on impressions and accomplishments more than stone statistical rigor. We’ll take into account what a player did and if it made us as Mets fans sit up and take notice for at least a spell, maybe no longer than a given day or night during the 2000s. Worth noting in this process: thirty Mets from that decade began their Met tenures prior to 2000, while 29 others continued as Mets after 2009, but we’re not allotting points based on anything anybody did before the decade in question kicked in or after the last of it was put in the books; apologies to my fellow 1999 aficionados.

Also, we’re not actually “allotting points”. Plenty of thought’s gone into this exercise, but there is no discernible formula at work. Take the rankings as seriously or as frivolously as you like. Just try to not be one of those sour sorts who insists everybody sucked then, sucks now and will suck forevermore. That sort of response is truly a bummer.

Happily, I can tell you with conviction that the 2000s crew brought more depth to the historical table than the Gang of 247 we reviewed from the 2010s. When I put together the 2010s series, I was continually disturbed at how high waves of mediocre Mets rated, gaining their given spot mainly because there was hardly anybody of substance to stick them behind. So while I can’t promise you a complete escape from obscurity nor immunity from unintended repressed-memory chills in the lower rungs of the forthcoming countdown, I do believe we have generally stronger Mets to look back on in something less than anger. They’re strong enough to have survived the test of time and wind up getting talked about in the preseason portion of 2021.

We’ll make space as well to talk about the state of the contemporary Mets; the Pitchers & Catchers scheduled to report imminently; the blur of Villars, Pillars and ILs; and who’s gonna make the however-many man roster in advance of Opening Day of the 60th (!) season of New York Mets baseball. Our heads remain, for a seventeenth consecutive Spring Training, mostly in the year at hand, even if our hearts steer us back to the many, many Mets who’ve driven us to the cusp of what’s next.

For FAFIF, the decade of the 2000s is what got us here and got us going. Starting tomorrow, we’ll visit with a hundred of the Mets from then and maybe recall what all the fuss was about.

by Greg Prince on 14 February 2021 12:54 pm When Joey Lucchesi, acquired from the Padres on January 19, Inauguration Eve, makes his first appearance as a Met, he will become the first Met to go by Joey. That’s a legitimate choice. Just ask Joey Votto, Joey Bishop or David Geddes, who took “Run Joey Run” to No. 4 in 1975. Just ask Joe Biden, whose folks, per the 46th president’s recurring recollections, tended to address their eldest son as Joey. Biden took “Run Joey Run” to heart, running for office so long and so often he was elected president after the most recent of those runs. Let that be a lesson for all you kids out there.

Pending acting GM Zack Scott’s tinkering, Joey Lucchesi enters 2021 with a solid chance to be No. 5 in his new club’s rotation. And on the day a fifth starter pitches, he might as well be No. 1. Yet eighteen Mets before Joseph George Lucchesi decided to go with Joe. Just Joe. Simple in its elegance. Elegant in its simplicity. And since January 20, Inauguration Day, unimpeachably presidential. Joseph Robinette Biden, Jr., you might have heard, is our first of 46 chief executives to go by Joe.

Joe Biden wearing No. 46 at a Congressional baseball game proved prescient. The Phillies part is a symptom of where he’s from. With Presidents Day weekend in progress, our Metsian instinct is to tip our caps to the likes of Claudell Washington, Gary Carter, Stanley Jefferson, several Jacksons and a few other Mets who share presidential last names. This February, however, we decided to go in a different direction. Thus, while we’re (ahem) bidin’ our time ahead of Spring Training, settle in for some nonpartisan fun with a few Met presidential first names of note.

We — the USA — started with a George as president, Mr. Washington in 1789. The other we — the Mets — had our first George in 1964: outfielder George Altman, a certified One-Year Wonder at Shea. He’d twice been an All-Star for the Cubs, who traded him to the Cardinals, who traded him to the Mets (with Bill Wakefield for Roger Craig). After batting .230 with nine homers, the Mets circled him back to the North Side of Chicago (for Billy Cowan). The Father of Our Georges would give way to three other Met Georges: George Stone, George Theodore and George Foster. Four others if you count George Thomas Seaver…and why wouldn’t you?

The Mets came to be under the presidency of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, popularly referred to, as Johns will be, as Jack. The first Met Jack came along the same season as the first Met George: Jack Fisher, who threw the very first pitch at Shea Stadium, April 17, 1964, with Altman around in right. Like JFK, Jack Fisher was born a John: John Howard Fisher. I don’t recall his being referred to as JHF, though he did pitch at a jauntily high frequency, starting 133 games between 1964 and 1967. Jack Fisher set the record for most starts in a single season by a Mets pitcher, with 36 in 1965. His mark has been matched since only by GTS.

The subsequent Jacks dealt onto Mets rosters were, in chronological order, Hamilton, Lamabe, DiLauro, Aker, Heidemann, Egbert, Leathersich and Reinheimer. I find it curious that three dozen years passed Heidemann’s last Met game in 1976 and Egbert’s sole Mets game in 2012. Among them, however, the Jacks of relatively contemporary vintage — relievers Egbert and Leathersich and utilityman Reinheimer — didn’t start as many games for the Mets as Fisher started in his least busy campaign.

Jacks may breeze into and flit out of style, but our Met Joes have always known how to spread themselves out. From the 1960s to the 2010s, there’s been at least one Joe to play for the Mets in each decade. Why, we began 1962 with a Joe among the Original Mets, Joe Ginsberg. The veteran catcher earned a spot on the Mets’ first active roster, which enabled him to become the very first ex-Met. His last game, for us or anybody, was our fourth as a franchise.

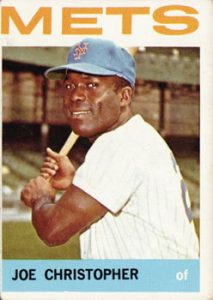

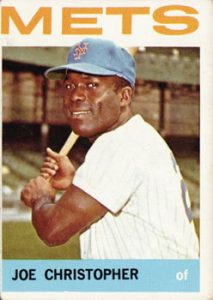

Easy come, easy Joe. The Mets had another Joe almost from the word go, Joe Christopher. His 1962 may not have been much (.244/.338/.362), but Christopher blossomed as the eventual everyday right fielder and fan favorite in 1964 (.300/.360/.466). Before 1962 was over, the Mets added their third Joe and second so-named catcher, Joe Pignatano. Later generations became intimately familiar with Piggy from his tending relievers and tomatoes as bullpen coach. His most memorable Met at-bat was the last of his career, a 4-6-3 triple play in the 120th loss of that first Joe-laden year.

Joe Christopher posed well in Manhattan but got hot in Queens. The Sixties would give us six Joes in all, with Joe Hicks, Joe Grzenda and Joe Moock rounding out the sextet. The Seventies dawned with the third baseman projected to slam shut the Mets’ infamous hot corner revolving door, Joe Foy. Ah, but did you ever try to slam a revolving door? Foy, like Hicks, Grzenda —à la Biden, a Joe born in Scranton — and Moock, only played in one Met season. His 1970 contained one amazing game: a 5-for-5 explosion at Candlestick Park that encompassed two homers, a double, five ribbies and the tenth-inning dinger that made the Mets victorious. This left 98 other games less shall we say explosive except for the trade that brought him to Shea blowing up in the Mets’ face. Foy was obtained from Kansas City in exchange for Amos Otis, who went to five All-Star Games as a Royal and gathered nearly 2,000 hits for KC across fourteen seasons.

The Mets haven’t tried their luck with either an Amos or an Otis since.

Joe Nolan caught in three games for the Mets in September and October of 1972 and pinch-hit in another. While he wasn’t garnering much support for playing time from Yogi Berra, another Joe was proving more appealing to his intended audience down in Delaware. Joe Biden and Joe Nolan showed up in the big leagues right around the same time. Biden would be elected to the Senate that November. Nolan would spend 1973 and 1974 in the minors before resurfacing with Atlanta and commencing one of those stalwart backup catcher careers that used to seem common, playing in eleven seasons, only once starting more than half of his team’s games. He’d earn a World Series ring with the Orioles in 1983, about the time savvy political types began sizing up Biden, then in his early forties, as potential presidential timber. He considered a run for 1984 before demurring and deciding to stay in the Senate, where he’d soon begin serving a third term.

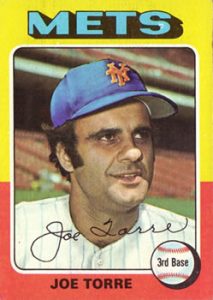

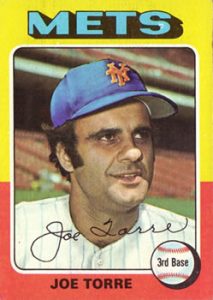

Joe Torre would need more time to airbrush himself into a World Seies. Joe Torre had been in baseball since before there were Mets — he debuted as a Milwaukee Brave in September of 1960, during Joe Biden’s senior year of high school — and would wait forever to get what Joe Nolan earned as an O and what Joe Pignatano received as a coach in 1969. When the former MVP came to the Mets in 1975, a half-dozen revolving door spins since Foy at third base, it was reasonable to imagine the Brooklynite would play a role on a world champion in New York. Indeed he would…but in the Bronx as a manager more than twenty years later.

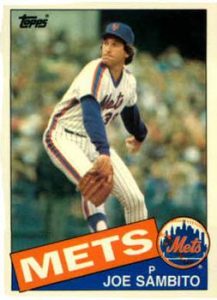

In the mid-1980s, a few years after Torre was asked to stop managing in Flushing, the Mets had grown a lot closer to reaching one of those tantalizing World Series. To perhaps put them over the top, they brought in another local Joe, lefty Joe Sambito. Like Torre, Foy, Pignatano and Ginsberg, he was born within the five boroughs. From 1979 to 1981, he was one of the best closers in the National League, playing a key role in the Astros’ rise to prominence. Then he got hurt, winding up on the Mets for a spell in 1985. His brief tenure is recalled mainly for his having pitched in the infamous 26-7 Mets loss at Veterans Stadium when he gave up eight earned runs in three innings.

Sambito didn’t pitch for the Mets again. Whence next they saw him, it was during the 1986 World Series. Joe was a reliever for the Red Sox. In a third-of-an-inning, he posted an ERA of 27.00. Unlike that night in Philadelphia, Mets fans weren’t complaining.

Joe Sambito’s pitching was more popular at Shea once it was no longer for the Mets. One (or one who wasn’t Joe Sambito) wishes time could have stood still as the 1986 World Series concluded. But time does what time will do, and time was flying. Joe Biden had run briefly for president in the late 1980s. He chaired the Clarence Thomas hearings in the early 1990s. Neither event went great for him. In 1992, as a different youthful political star born in the 1940s was winning the White House, the first Met born in the 1970s was taking the field, righthanded pitcher Joe Vitko. A native of nearby Somerville, N.J., Joe broke the decade barrier by throwing a scoreless ninth inning versus the Expos at Shea on September 18. He also gave up his first hit to a future Hall of Famer, Larry Walker. Yet there was no reason Vitko, 22 and the only Met Joe to come along while George H.W. Bush was president, couldn’t have dreamed Cooperstown dreams of his own.

Alas, Vitko’s threw his final big league inning on September 28, 1992, five weeks before Bill Clinton, 46, was elected our 43rd president, three months before Joe himself turned 23 years old. So Joe Vitko from New Jersey would be gone from Shea in the season that followed his debut, but Joe Orsulak from New Jersey would arrive. The Parsippany Kid, if you will, proved a valuable lefty bat for a Met club that had little else worthwhile in 1993 and stuck around as the Mets began to refind their footing before and after the 1994-95 strike. My fondness for Joe Orsulak has been duly noted.

(Also worth duly noting: the second Met born in the 1970s was Bobby J. Jones, who had a far longer run than Joe Vitko…and whose middle name is Joseph, and whose middle name can’t be spelled without J-o-e. It’s worth duly noting because Friend of FAFIF Mark Simon just published a splendid SABR Biography of the only Met to throw a post-season one-hitter, a profile you can access here. I really like the part about why Jones strove to remain calm when the cameras were on him.)

I’m mostly agnostic on Joe Crawford, lefty pitcher for the 1997 Mets, but I’m perpetually gaga for the 1997 Mets, so even the slightest of 1997 Met achievements warms my cockles no end. On August 21, Joe took a spot start, opening a twi-night doubleheader by defeating the Dodgers with six innings of three-hit ball. Consider my cockles warmed.

Joeficionados refer to the 2000s as the Joenaissance, starting with the 2000 season. BUT, before we get to the turning point, let us pay homage to a pair of throwbacks, the two most recent Met catchers named Joe.

When he came up as a 29-year-old newbie for two pinch-hitting appearances and two half-innings of catching over two nights in Houston (August 5-6, 2003) before completely disappearing from the MLB radar, you might have confidently said Joe DePastino couldn’t have had a shorter big league or Met career. Yet you would have been wrong. True, DePastino’s stay was brief and hard-earned — he’d been in pro ball without a sniff since before Joe Vitko was a Met more than a decade earlier — but seeing this Joe make it for a minute meant you hadn’t seen all such a story had to offer.

A year later, at the very end of the 2004 season, Art Howe — the same manager who gave DePastino his break — granted a line in a box score to Joe Hietpas. In the top of the ninth inning of Game 162, with the Mets well in front, Howe sent Hietpas into catch Bartolome Fortunato for five batters. Hietpas himself never had the pleasure of standing at the plate at Shea or any other stadium above Triple-A. By 2005, he was in the minors again. By 2006, he was a pitcher. In 2020, he was A Met for All Seasons, if only a player for a moment.

If a discreet gentleman were to choose a nom de plume to write on an HOURLY RATES motel guest register, “Joe Smith” might be the first generic entry to spring to mind. Ah, but Joe Smith, a sidearming righty reliever proved a long-term renter, if not on the Mets, then in the majors. Smith surprised by making the Mets staff out of Spring Training in 2007 at age 23. While six-term senator Joe Biden was planning a second presidential run, Joe Smith was becoming a primary option out of the pen for Willie Randolph, pitching in 54 games as a rookie. A year later, Biden was out of the race for his party’s nomination, but Smith made the Mets’ ballot 82 times. Young and possessing an unorthodox delivery, Joe was that rare Met reliever whose reputation wasn’t destroyed by the general bullpen implosion that helped close down Shea. Come December of ’08, Joe Smith was traded to Cleveland. That was one month after Joe Biden was elected vice president of the United States and one month before Biden took the oath of office alongside Barack Obama

Quite the interregnum for both Joes. Smith would stick around getting outs everywhere through the fall of 2019, when he’d pitch in his first World Series, as an Astro. Five years earlier, another Joe played in the Fall Classic, but as a rookie. Joe Panik, a product of the nearby Hudson Valley, made himself essential to the essential to the even-year San Francisco Giants dynasty of the first half of the 2010s. While Smith was preparing for the final postseason during which nobody’d ever heard of COVID-19, Panik was trying to help the Mets make a late playoff push by becoming the eighteenth Met Joe ever and the only Met Joe of the decade. Panik played well in a limited role, but the Mets didn’t roll into October. In 2020, Joe Panik was a Blue Jay and has signed with Toronto to be one again. During the same pandemic-shortened season, Smith sat out due to family health concerns, but looks forward to returning to pitching for the ’Stros in 2021. As of this cusp-of-Spring Training writing, he is the only Shea Met still signed to a big league contract, though Ollie Perez’s left arm remains eternally available.

Shea Stadium is no longer around. Joe Smith is. Oh, and Joe Biden is president, a few weeks after his inauguration, having spent his first Presidents Day weekend ensconced at Camp David (named in honor of David Wright, of course) and running the executive branch in the aftermath of the virtual Queens Baseball Convention, whose special online guest was the chronologically fourteenth Joe to play for the Mets, Joe McEwing.

As noted above, McEwing was the Joe to usher in the Met Joenaissance. Upon his trade to the Mets in 2000, you might say he symbolically ushered out the previous century. To get this Joe, the Mets had to give up the only active major leaguer who had been a Met in the 1970s, never mind the only active major leaguer who had literally saved the Mets’ most recent world championship.

On December 10, 1999, the Mets swapped lefty specialists with the Baltimore Orioles, sending Chuck McElroy down Biden’s beloved Amtrak corridor for Orosco. Orosco at that point had been on the MLB scene for some twenty years. He pitched for the Mets when the Mets still had Ed Kranepool, who came up to the Mets before The Jetsons forecasted life in the 21st century. Jesse was going to pitch for the Mets in that very same suddenly arrived future. We wouldn’t have flying cars in the year 2000, but we would have the same lefty who tossed his glove in the air on October 27, 1986, maybe giving us cause to celebrate anew.

Except the Mets traded the dream of Jesse Orosco in the 21st century to St. Louis for bench depth. At the time, I was disappointed from a storyline standpoint. Over the next five years, I’d come to value Joe McEwing’s versatility. No Joe made it into more games as a Met than McEwing. He played in 502 of them from 2000 to 2004. Few Mets played more positions as a Met. Super Joe didn’t pitch and catch. He did everything else. He played every infield position, every outfield position, pinch-hit and — this is the part I love — pinch-ran. I mean he really pinch-ran.

Joe McEwing was ready to run, Joey, run, regardless of the time of year. Just as no Joe has played more games as a Met than McEwing, no player has pinch-run as a Met more than the Bristol, Pa., native. Sure, you probably recall him for his turning into a slugger at the sight of Randy Johnson, but did you know how often Super Joe insinuated himself into games for speed’s sake?

I’ll be happy to tell you. Joe McEwing pinch-ran 56 times in regular-season play between 2000 and 2004, topping the longtime previous franchise recordholder, Rod Kanehl by four. Super Joe. Hot Rod. Third place, incidentally, belongs to a pitcher, Little Al Jackson. You can’t say serious pinch-runners defy descriptions. In the postseason, McEwing was doing his thing as well, taking somebody else’s base eight times; no other Met has pinch-run in the playoffs/World Series more than twice.

During baseball’s hiatus last May, the Irish American Baseball Society hosted a Zoom call with Joe McEwing, who would have been coaching White Sox players at that time of year most years. For a few well-worth-it bucks, you could sit in, listen, ask a question, maybe learn something you didn’t know about playing baseball. With no game to watch, I signed up, raised my virtual hand and asked Joe to explain how a player sitting on the bench gets the most out of going into the game to run for somebody else.

Joe answered me in detail.

That’s what I took a lot of pride in. That started at 12:30 in the afternoon, with my pregame preparation.

If I wasn’t in the lineup. I was preparing mentally and physically for whatever was possibly gonna happen during that game.

Whether it was pinch-running, defensive replacement, pinch-hitting. I was an individual who hated missing outs during a game, but I had to be prepared for every situation, ’cause I never knew when I was gonna be called upon.

It could be the first inning, could be the seventh inning, could be the fifth inning, could be the ninth inning.

So in between innings, as soon as the third out was made, if I wasn’t playing that day, I’d go run sprints in the hallway. And then I would take a few swings off the tee under beautiful Shea Stadium — trying to miss rats that were coming out — then throw a few balls into the net, then head back to the dugout, then watch the next half inning.

Go back up, run sprints, take a couple swings again, just so I was mentally and physically prepared for any situation that was gonna happen during the game.

The thing about it was I observed so much throughout a game that I didn’t want to miss an out, I didn’t want to miss a pitch. Those two-and-a-half, three minutes between, I maximized every second of it.

It’s more mentally and physically exhausting not playing than it is playing.

Followup for Coach McEwing (and not about the rats of Shea): Was it different being a pinch-runner versus getting on base as, shall we say, your own hitter?

That all starts at 12:30. You’re breaking down video of every single guy on the mound: the starter, every guy in the bullpen. His times to the plate. His moves. Does he have quick feet? Is he hard coming over? Does he have any tells? Does he tip when he’s going to the plate? Or with head movements? Or whatever when he’s coming over. And you try to take advantage of every single situation because 90 feet mean a ballgame.

If you’re reading that ball in the dirt, you’re taking that base, now you’re in scoring position. You’re stealing that base, now you’re in scoring position to put your team in a better position to be successful.

As for the challenge of coming in cold rather than having been in the game the entire time, Super Joe explained, “That was my life. That was my career. That was my job. I took extreme pride in that, being prepared for every situation.” The preparation, he concluded, earned him a substantial career in the big leagues.

One could choose to say something similar about another Joe born in Pennsylvania who was (ahem again) bidin’ his time preparing for his next chance and was eventually called on in a pinch to do a job, but I aimed to be nonpartisan with this feature.

Happy Presidents Day, everybody!

by Greg Prince on 13 February 2021 6:46 pm Recently, as in a day or two before a revised Spring Training schedule embedded with a pod of Marlins, Nationals, Cardinals and Astros was issued and my mood instinctively if temporarily brightened, I was feeling pretty nihilistic about the whole Mets baseball thing. “Can you imagine them trading…?” I asked myself about pretty much every player, and I decided I could. Tacitly approving the trading or letting walk as a free agent just about any Met I’d normally throw the bulk of my sentiment in front of so as to prevent his wrenching departure was a new emotional sensation for me, though I honestly wasn’t feeling much emotion. I’m told we nihilists rarely do.

Yeah, sure, hypothetically trade whoever if you think so. Make the team better. Don’t make the team better. What’s the point? Not endorsing anybody’s expulsion from Met ranks, not advocating immediate action, just deciding I could live without most any given current Met if I absolutely had to (not that various GMs ever seek my blessing). My lone, unmovable exception was Jacob deGrom…“and maybe Seth Lugo”.

Twenty-four hours into tentatively shaking off the crust of winter with the realization that camp is about to open, I had my “maybe” snatched away, at least in the short term. Seth Lugo, the sole fully dependable Met reliever of the latest pennus horribilis period, is out for a while with an inflamed elbow whose bone spur “broke off,” which sounds terrible, if not as bad as the official diagnosis that he has a “loose body” in there. For Seth’s sake, let’s hope the body is no larger than Freddie Patek’s.

Well, next thing ya know, ol’ Seth is David Altchek-bound, getting that pesky body surgically removed, which means six weeks until Lugo sees his curveball’s shadow. That brings us to the cusp of Opening Day, indicating Seth will have his very own extended Spring Training before we see him when we see him. One could project a timetable for competitive pitching, but as one who was silly enough to decide “maybe” I couldn’t do without him, I shall decline that option. Recover safely and speedily, No. 67.

We don’t get any Lugo, but we get loads of Marlins real soon. The Mets’ bullpen without Lugo — which was what the Mets had the latter portion of last year when Seth talked his way into the mostly vacant starting rotation — now becomes something less than a confidence-inspiring destination. Granted, except for approximately two weeks in 2006 when Wagner, Sanchez, Heilman, Bradford, Feliciano and Oliver had it goin’ on in sync, that’s been the standard 21st-century state of affairs. Seth Lugo’s right arm has been a veritable security blanket to which our angst would cling; we were all Linus contentedly sucking our thumbs when he entered to pitch. Without Seth, the depth we might have been thinking upon counting is mostly numerical and reputational.

Lotta guys. Lingering doubts. Edwin Diaz is again slated to tease us with his talent and subsequently destroy our faith in a ninth inning coming to a ballpark near us (unless it’s the seventh inning of a Manfred-rigged doubleheader). Brad Brach was squeezed out for 40-man reasons, though the same basic subtraction could have been accomplished by excluding any among several other holdover relievers who’ve not lived up to our middling hopes. Newcomers Trevor May and Sam McWilliams I’m relatively high on mostly because I’ve never seen either blow a Mets lead.

The fact that I’m fretting how we’re gonna fill Lugo’s innings is a perversely good sign. It means I’m looking forward to 2021, albeit in a sleep with one eye open, gripping my pillow tight fashion. Wintry mix in New York notwithstanding, Spring is practically in the air.

by Greg Prince on 9 February 2021 4:38 pm Boys, gather round. I’ve got something important to say. For those of you who haven’t met me yet, I’m here to show you how to win. Don’t feel bad that you’ve got to hear it from me. Nobody you know was going to tell you. They’re too polite.

You haven’t won because of your surroundings. You haven’t won because of New York. New York hasn’t built a winner in nearly a decade. It doesn’t have to be that way, but it’s become that way. It ain’t nature. It’s nurture. And from what I can tell, we’re nurturing a generation of overly humble kids in these parts. Of course they’re humble. They’re growing up without a championship team. This is dangerous to our future.

Me? I came here from Chicago. We won in Chicago. I won in Chicago. I could call it “the Chicago way,” but this isn’t necessarily about Chicago. But I did play in a World Series there. I played in a World Series and I won a World Series. Scored the tiebreaking run in the tenth inning of Game Seven. I’ll pass my ring around later so you can get a good look since I guess none of you have ever seen a real recent one up close.

Yeah, I see you Frankie Lindor. You and the Tribe played good in that World Series. We played better. We won. But at least you’ve been around winners. You were in Cleveland. Cleveland’s had a champion. Just like we did in Chicago.

My name? I’m Albert. Albert Almora. Albert Almora, Jr., to be precise. You think I’m here to give you defensive help, but I’m really here to deliver a much-needed psychological assist. My name may say “junior,” yet vis-à-vis all of you, you might say I’ve got seniority. I’ve won a World Series. Anybody else here who can say that?

You? J.D. Davis, right? You’re flashing your ring at me? Put it away, son. You weren’t on the World Series roster in Houston, were you? No, I didn’t think so. Still, you were around winners. You’ve been in Houston. However they did it there, they won.

The rest of you, you’re from New York. You guys never win anything. It’s sad.

What’s that? 1969? 1986? How old do you think I am? Never mind ancient history. I did my homework. I know nobody in New York has won anything since Super Bowl XLVI. That’s right, I speak Roman. You know how long ago Super Bowl XLVI was? That’s IX years ago. New York has been nowhere since then.

Chicago — my Cubs, in particular, but also the Blackhawks — has been a champion. Cleveland — the Cavs — has been a champion. Houston — the Astros, trash cans and all — has been a champion. You know Tampa Bay, which is technically a body of water, has won two since last summer. And Los Angeles, which you guys in New York like to make fun of for subpar pizza. They won two, too.

You got the pizza, but you can’t get even a taste of the pie you know you crave. Damn, guys.

Since New York last won anything, Philadelphia won a Super Bowl. They’re right down the Turnpike. Seattle won a Super Bowl. They did it across the river, in the Meadowlands. New England won a bunch and New England isn’t even a city. Neither is Golden State, but they won multiple NBA titles. Just ask Kevin Durant. Like I’ve come here to help Flushing figure out how to win, he went to Flatbush to help them figure out how to win.

That’s right, me and Kevin Durant and, for that matter, Kyrie Irving are champions, spreading the gospel, each of us in our own way You’re not. Not yet. Aw, little old New York, however many million stories in the Naked City and not a single one about winning a championship since Barack Obama’s first term. Five boroughs, no dice.

All kinds of cities and markets have gotten trophies and hosted parades. We had a great one in Chicago. You want me to tell you about it? No, you don’t. You want to have one for yourselves.

Guys, seriously, almost everybody somewhere else has a ring since February 5, 2012. You got, what, nine teams around here, counting the ones in Jersey not near Philly? Hell yes, count the ones in Jersey. The Hudson ain’t that wide.

Giants: 2011 season.

Yankees — and I know we don’t like them: 2009 season.

Devils: 2002-2003 season.

Rangers: 1993-1994 season.

Us, the Mets: 1986 season.

Islanders: 1982-1983 season.

Nets: 1975-1976 ABA season.

Knicks: 1972-1973 NBA season.

Jets: Oh my god, you have to go back to the AFL and the 1968 season.

Whatever happened to braggin’ rights? More like humility rights. “After you, Philadelphia. After you, Foxboro.” Good lord.