The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

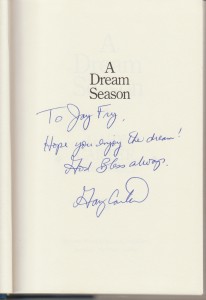

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 28 August 2020 10:30 am Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

“People like to see human error when it’s honest. When people see you swing and miss, they start to root for you.”

— Paul Westerberg

I became a Mets fan in 1976, when the team had perfected an imperfect formula: combine superb pitching and defense with no offense and finish third. Miracle Met stalwarts Tom Seaver and Jerry Koosman were still around, as were Jerry Grote, Wayne Garrett, Buddy Harrelson and Ed Kranepool, who’d always been around and one assumed always would be. Joining them were representatives of the Little Miracle — guys like Jon Matlack and John Milner and Rusty Staub.

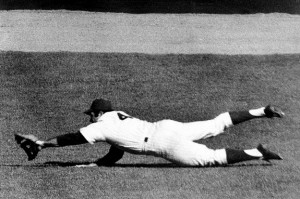

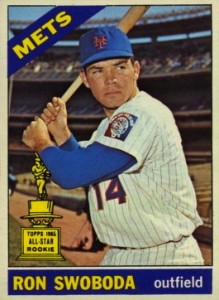

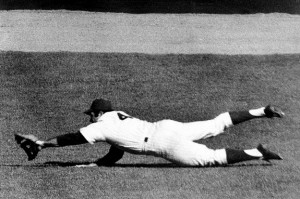

Staub was my favorite player, though of course I loved Seaver, rooted for Harrelson and appreciated Kranepool. But as a newly minted Mets fan with a dorky, proto-blogger’s bent, I hungered for history. Desperate to know what I’d missed, I inhaled books about my team — if the Emma S. Clark Memorial Library had a quickie book about the ’69 or ’73 team (or any other year), I read it and then immediately wanted to read it again. With DVDs and online video yet to arrive, I got most of my postseason lore from the written word and static pictures, from descriptions and reminiscences and snapshots and sportswriters’ flights of fancy. Tommie Agee in awkward mid-stride, a plume of white at the end of his arm. The unhurried way Gil Hodges strolled from the dugout to visit Lou DiMuro with a baseball in one big hand. Tug McGraw dodging and diving and weaving and bulling his way to the dugout. Willie Mays on his knees in vain supplication. Koosman jackknifed in Grote’s arms, with Ed Charles in the early stages of liftoff nearby. And, of course, Ron Swoboda — fully outstretched and parallel to the right-field grass, approaching an uncertain intersection with the ground and a baseball.

Swoboda was gone by 1976, but in every account of the ’69 Mets he loomed large. Not just because of The Catch, but because he was smart and funny and reflective and complicated. Which, though I didn’t know it yet, made him my prototype for what I wanted every baseball player to be.

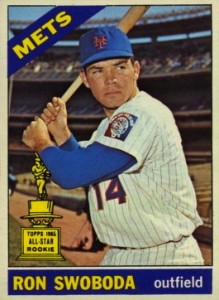

The lore was pretty thick around Swoboda even before 1969. He signed with the Mets for $35,000 in 1963 as a 19-year-old from the University of Maryland. (Ironically, given what came later, Swoboda was born and raised in Baltimore and had played high-school exhibitions in Memorial Stadium.) His last name is Ukrainian for “freedom.” In 1964, he caught Casey Stengel’s eye — the young slugger reminded Casey of Mickey Mantle — and was hyped as part of the Mets’ about-to-arrive Youth of America.

Casey pronounced his name Suh-boda, which stuck with fans. Teammates called him Rocky, a reference to his mental lapses in the field and his ability to say the wrong thing at the wrong time off of it. He came to the Mets to stay in 1965 — a callup he would come to regret — and became a fan favorite. Writers loved the fact that he had a Chinese grandfather, which wasn’t really true — his grandmother had married the owner of a Baltimore Chinese restaurant. Fans loved his ability to hit long home runs and sympathized with his outfield misadventures — you were never quite sure what Swoboda might do out there, but you were pretty sure it would be memorable. In his first big-league at-bat, a terrified Swoboda fell into an 0-2 hole against Don Drysdale, and considered it a triumph that he lined out to second. (“I felt like a fish that had been dragged into the boat and somehow managed to flop back out,” he’d remember.) Two days later, his second big-league at-bat produced a home run. RON SWOBODA IS STRONGER THAN DIRT, fans proclaimed at Banner Day.

In one game, Swoboda forgot his sunglasses, misplayed a Dal Maxvill fly ball into a triple, returned to the dugout in a fury, and stomped on a batting helmet. The helmet got stuck on his cleats and left Swoboda hopping around trying to dislodge it while Stengel turned the color of a ripe tomato. Casey pulled Swoboda from the game, asking, “Do I go around breaking up his property?” Another time, Casey groused that Swoboda “thinks he’s being unlucky, but he’ll be unlucky his whole life if he don’t change,” a bit of baseball wisdom I recycled later in life for Come to Jesus conversations with wayward journalists. Yet for all his misadventures, Swoboda hit 19 home runs in 1965 — a Met rookie record that stood until Darryl Strawberry eclipsed it 18 years later.

Swoboda managed the difficult and dubious feat of hurting his development as a ballplayer by alternately thinking too much and not at all. (Years after he retired, he admitted he still had nightmares about facing one of the great hurlers of the ’60s and not being able to get set in the batter’s box.) He wasn’t always popular with teammates, who were annoyed by his on-field mistakes and his off-field gift of gab. When reporters entered the clubhouse after a Met win, it wasn’t uncommon to hear someone yell out “Tell them about it, Rocky!” It should come as no surprise that one of his best friends on the team was the irrepressible, quotable McGraw. (The other was Kranepool.) But Swoboda was pretty quotable himself: In ’69, he was booed after striking out five times in one game, and opined that “if we lost, I’d be eating my heart out. But since we won, I’ll only eat one ventricle.”

1965, the year Swoboda represents in A Met For All Seasons, was a template for everything that followed — heroic moments mixed with ignoble ones. Four years later, it was still true: On Sept. 15, Steve Carlton struck out 19 Mets, with Swoboda accounting for two of the Ks … as well as the two home runs that beat Carlton. And, of course, there was The Catch. It wasn’t a particularly smart play — obviously he should have played it on a hop — except for the fact that hey, he actually caught it. “I had no time for conscious thought or judgment,” he’d recall. “The ball was out there too fast. I took off with the crack of the bat and dove. My body was stretched full out, and I felt as if I was disappearing into another world. … Somehow it happened. Somehow I got it. A miracle? Wasn’t the entire season a miracle?” In that one play the ignoble and the heroic did battle, the heroic came out on top, and because of that Ron Swoboda was a baseball immortal. As Tigers manager Mayo Smith put it, “Swoboda is what happens when a team wins a pennant.”

Two years after the Mets’ champagne celebration (“they’ve sprayed all the imported and now we have to drink the domestic,” he griped cheerfully, which became one of my go-to lines as a child even though I had no idea what it meant), Swoboda was traded to Montreal after one complaint too many about playing time. He hung around for a bit with the Yankees, failed to catch on with the Braves and was out of baseball by 29. He then began a long career as a broadcaster, one that would take him to New York and Milwaukee and Phoenix and New Orleans.

He was a sportscaster in New Orleans when I arrived there in 1989 as a pathetically green Times-Picayune intern, and a lot of people I came to know at the newspaper knew him. This finally registered with me when the woman I was dating mentioned in passing some bantering exchange she’d had with him. She had no idea that I was a Mets fan, and must have wondered why I stared at her in amazement. She knows Ron Swoboda. Which means I could meet Ron Swoboda.

The idea terrified me — I was a kid, and incapable of thinking of him as a fellow journalist. I’d read about him and looked at pictures of him since I was seven years old. He was a Met, a World Series hero, the man who made the Catch. He was Ron Swoboda. Meet him? And then what? It would have been like chatting with Zeus. (I did meet him a couple of years ago, after a ’69 Mets panel in midtown, and while he was perfectly nice, it was brief and dopey. In an uncharacteristically wise move, I didn’t mention having avoided him in New Orleans.)

When we grouse that ballplayers don’t seem smart, most of the time what we’re really lamenting is that they aren’t much for self-reflection. There’s an entertaining W.P. Kinsella story called “How I Got My Nickname” in which the ’51 Giants are all hyperliterate gents given to pondering the cosmos, a story that works because it’s immediately and obviously a fantasy. Back in ’92, Kelly Candaele (Casey’s sister) penned a great piece in the Times in which, among other things, she wondered about the fact that her brother and his teammates didn’t lie awake thinking about their purpose in life. When she asked Astros shortstop Rafael Ramirez about that, his answer was, “When I wake up in the middle of the night, it’s because I want a sandwich.”

I don’t assume baseball players are dumb — I’m amazed at how many of them can analyze pitch sequences and find little tells during the game, and how they remember at-bats in vivid detail years later. Beyond their superhuman physical talents, many of them have an extraordinary ability to focus that most of us don’t know enough to understand we lack. But self-reflection? I suspect most of them are like Ramirez, and probably better for it. When you make a living playing a supremely difficult, maddeningly unfair game, self-reflection isn’t necessarily an asset — better to let the moment go and start fresh.

There are exceptions. Players like Seaver or Darling or Keith Hernandez can dissect baseball like generals or prize-winning academics and focus that same lens on themselves. The 2000 Mets had three such players in Al Leiter, Mike Piazza and Todd Zeile — all smart, complicated guys who weren’t afraid of being interesting. But those players are exceptions that prove the disappointing rule.

The first Met I knew of who was exceptional like that? It was Swoboda.

It’s clear that he spent his share of middle of the nights lying awake, and not because he wanted a sandwich. He isn’t just a good quote, but also bracingly honest about himself. (You’ll find great interviews with him — the sources of many of this post’s quotes — in Stanley Cohen’s A Magic Summer and Maury Allen’s After the Miracle.) He’s talked wistfully about he never got along with Seaver, admitting that he was the one who sabotaged any chance at friendship. “I wanted to be the best in the game at my position; I wasn’t,” he said. “He just made it look so easy, was so good — and it just frustrated me so much.” And he’s told the story of confronting Hodges in the clubhouse bathroom over his use of Kranepool — after which, feeling his manager’s glower on his back, “I was standing against the urinal and I couldn’t pee.”

Of course, Swoboda will always be bound up with 1969 and the Miracle Mets — a bit of typecasting he has accepted cheerfully. (“How long am I going to make a living off of one catch? How long have I got left?”) That’s no surprise, but Swoboda’s reflections on ’69 have almost invariably been interesting, too. “We were ingenues,” he recalled once. “We had that wonderful, clear-minded innocence of not having the responsibility of winning it, of not having to doubt ourselves if we stumbled, and that’s a marvelous state to achieve.” Another time, he said that 1969 “wasn’t destiny. I don’t believe in destiny. What I believe is you can get to a state where you are not interfering with the possibilities.” That’s a long way from taking them one game at a time, pulling together as a team and all the other rote nonsense players have been taught to say so that reporters go away as quickly as possible.

And Swoboda has always understood what that summer meant to the fans, and refused to see what he did and what we did as disconnected. He has always been willing to bridge that gap, and make us feel like it doesn’t have to exist, even though he and we know better. “I never felt above anyone who bought a ticket — I just had a different role than they did,” he’s said. “We were part of the same phenomenon.”

The ’69 team was heralded at Citi Field during its first summer, and I of course cheered for all of them. I applauded the McAndrews and Gaspars and Dyers, cheered for the departed Tug and Gil and Donn and Don and Cal and Tommie and Rube, and gave Seaver and Koosman and Ryan their due, as one must. But the player I cheered longest and loudest for from that team?

It was Ron Swoboda. It always has been.

If you’re a veteran reader with a sense of deja vu, no, you’re not going crazy — this post appeared in much the same form back in 2010. Hey, I got it right the first time.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1986: Keith Hernandez

1988: Gary Carter

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2007: Jose Reyes

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

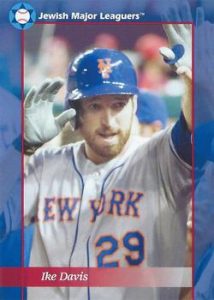

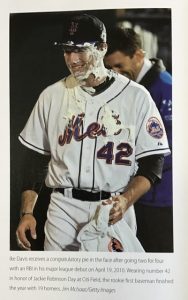

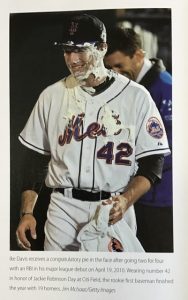

2010: Ike Davis

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2019: Dom Smith

by Jason Fry on 27 August 2020 11:45 pm The Mets and Marlins didn’t play Thursday night.

After some milling around in front of both dugouts, the Mets ran out to their positions, led by Dominic Smith and Billy Hamilton. Miami’s Lewis Brinson stepped to the plate. Caps came off. The other players on both teams came out of the dugouts to stand in a line. After 42 seconds of silence, both teams left the field, leaving behind a Black Lives Matter shirt on home plate.

It was a powerful moment, covered with care and, yes, grace by SNY. Afterwards, Michael Conforto, Smith, Robinson Cano and Dellin Betances addressed the media, masks on as per COVID necessity. SNY threw it to Gary Apple and Todd Zeile, who spoke from the heart. Brodie Van Wagenen talked to the media — more on that in a moment — and then Steve Gelbs conducted a poignant, sometimes raw interview with Smith. It was surreal and confusing and moving all at the same time.

The Mets being the Mets, there had to be a sideshow. Last night, people started sniping at each other on Twitter over Smith’s decision to take a knee Wednesday night and the Mets’ having tweeted the message UNITED FOR CHANGE. That’s the tagline that’s been handed down by Major League Baseball, but it made for an awkward show of support: How united could the Mets be if Smith had acted alone?

Then, a couple of hours before the game that wasn’t, video somehow went out to the world of Van Wagenen having a private conversation with two people off-camera in which he said Rob Manfred, citing scheduling concerns, was pushing Jeff Wilpon to have the teams to walk off the field at 7:10 but return at 8:10. Van Wagenen reacted with a mix of incredulity and exasperation, saying that Manfred doesn’t get it “at that leadership level.” I was simultaneously embarrassed that someone with Van Wagenen’s CV would get tripped up by a hot-mic moment and struck that it was most honest and genuine that the Mets’ general manager had ever sounded. After the game was postponed, Van Wagenen issued a statement saying the idea for an hour’s delay was Wilpon’s and not Manfred’s, and apologizing to the commissioner. I don’t believe for a second that’s what actually happened (though Wilpon-Manfred isn’t exactly the Thrilla in Manila of credibility bouts), but I also thought it was an adept way to save face.

As for the Mets, they seem to have been caught off guard by Smith’s gesture on Wednesday, but more than made up for it a day later, supporting him and his efforts to call attention to the racial injustices he’s spoken about with candor and vulnerability and passion. Wednesday’s tweet may not have matched what we saw before the game, but a day later it was a perfect fit. The Mets also reached out to the Marlins to create a shared moment, with the 42-second hold an idea that came from Miguel Rojas. And all involved — from the players in the press conference to Van Wagenen — spoke eloquently about the need for change in ways I wouldn’t have dreamed possible from baseball just a couple of years ago. The execution might have been both messy and Metsy, but in the end I was proud of my team.

After the game, because I can’t stop myself from touching hot stoves, I waded into the dumpster fire of replies on Twitter. While cathartically blocking people I wish weren’t Mets fans, I kept seeing the same complaint — that the teams had created a spectacle.

Well, that was the point. Not a tweet or a press release that you might wave away, but a moment where you had to pay attention because you were expecting a first pitch and instead got something you had to engage with. That’s how protest works — it disrupts routines so the gesture can’t be ignored. This is what those still complaining about Colin Kaepernick and those he’s inspired either don’t see or refuse to see — that a protest is ineffective and frankly means a lot less if it’s done when no one’s watching. The goal isn’t disrespect — Kaepernick started taking a knee after talking with a former Green Beret who’d objected to his initial decision to sit during the anthem — but discomfort, as a means of generating awareness, sparking conversation and driving change. However strangely the Mets and Marlins arrived there, they certainly reached that goal.

I was also reminded that while there’s a segment of fans who reliably bray for athletes to stick to sports, sports have always been arenas in which we’re forced to confront questions about race relations, fair labor practices, freedom of association, safety standards, gender attitudes and a whole lot else besides. Sure, part of sports’ lure is that they let us put aside the cares of the day and watch a simple morality play — I want this team of obvious gentlemen to beat that team of thorough evildoers. But to treat sports only as that morality play is to be willfully blind to so much around us, and to denigrate the athletes we just got done exalting. Telling athletes to “shut up and dribble” or to “stick to sports” is to dismiss them as hired help. (For the last couple of generations they’ve been extravagantly well-paid hired help, which adds a queasy note to the proceedings without changing the underlying issue.)

Whether we like it or not, the larger world is always present — and sometimes it comes smashing through the frame. The biggest story of baseball’s 20th century was Jackie Robinson‘s bravery in breaking racial barriers that had impoverished the game, and what that lonely effort cost him. The second biggest story of the century was the players’ long battle to be treated as something other than chattel and paid accordingly, a struggle that cost Curt Flood dearly as its pioneer. And we haven’t seen the last such story — there are gay players on big-league rosters today, but you don’t know who any of them are, because they know stepping forward would cost them dearly. One of these days one of those players will decide they’ve had enough and speak up while still in uniform, and you better believe it will be intensely political. One of these days a female amateur athlete will show off a hellacious knuckleball or some other monetizable talent and get signed, and the furor will be both exhilarating and exhausting.

The Mets have been a part of this, because how couldn’t they be? There’s a plausible case to be made that Reggie Jackson was never a Met because he dated outside his race, which was most certainly and shamefully political in the mid-1960s. In 1968, the Mets refused to play after the deaths of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, with the latter decision causing a showdown with Giants owner Horace Stoneham, who wanted the big gate that came with Bat Day. Tom Seaver caught hell for having an opinion about Vietnam, and I guarantee someone told him to shut up and pitch. Rusty Staub and Seaver were traded away for being union activists, with M. Donald Grant demanding to know where Seaver got the temerity to think he could join the Greenwich Country Club. That’s a small sample — hot-button political issues, charged assumptions, unfortunate prejudices and societal fears have shaped our team’s history just like it has every other team’s.

This morning, before so much happened, I read the terrific SABR biography of Donn Clendenon. (Whose A Met For All Seasons entry is here — and will be joined by a salute to a teammate on Friday.) If you don’t know much about Clendenon besides his having been a Pirate and homering after the shoe-polish play, you should read it. A few of many highlights:

- Clendenon’s mentor at Morehouse College was Martin Luther King Jr.

- He was tutored as a ballplayer by the likes of Satchel Paige, Nish Williams (his stepfather), Roy Campanella, Robinson and Joe Black

- Clendenon was interested in playing football for the Cleveland Browns, but steered back to baseball by his stepfather, who arranged to seat him between Robinson and Branch Rickey at an Atlanta awards banquet.

- The general manager for Pittsburgh’s Grand Forks, N.D., affiliate set Clendenon up with the daughter of the only black family within miles so he’d stay away from white women; Clendenon turned the tables when he agreed to take on the clubhouse duty of shining shoes and doing laundry, tasks he promptly subcontracted to high-school kids for a profit.

- The next season, Clendenon was demoted from the Pirates’ Wilson, N.C., affiliate because it was their second year as an integrated team and they were seen as having too many Black stars. He quit, threatened to jump to a Canadian league, and had to be coaxed into returning.

- Determined to have a career after baseball, Clendenon attended Duquesne University’s law school while playing for the Pirates, winning a senatorial scholarship and clerking for a judge. He recalled that there were two other Blacks at the law school: his con-law professor and the janitor.

- One offseason, Clendenon worked for the Scripto Pen Company, where he led a union drive and brought in Dr. King and Stokely Carmichael to stiffen the workers’ resolve.

- Clendenon has two 1969 baseball cards — one as an Expo, the other with “Houston.” That happened because he was traded to the Astros but refused to be reunited with his old manager Harry “The Hat” Walker, viewed by many Black players as an incorrigible racist. Clendenon insisted he’d retire, and the teams worked out a deal to keep him an Expo — at least until he was traded to the Mets.

- One I’d never heard before — according to his SABR biography, Clendenon was given 22 as a Met (he’d worn 17 for his two earlier teams) because the equipment manager told him he was a “double deuce,” derived from “number two” being slang for a Black person. With the Mets Tommie Agee wore 20 while Cleon Jones wore 21. Hmm.

Clendenon played before free agency and taking a knee, but his baseball career and his life were shaped by both racial attitudes and hot-button politics. And you don’t have to be a fiery progressive to guess how many indignities and injustices his capsule biography must leave out. He died of leukemia in 2005, when Dom Smith was just 10 years old. I wish they could have had a conversation about the issues of both their careers — and that we might have been allowed to listen in. I think we would have been illuminated and challenged and inspired, as Mets fans and as people. Even if that conversation didn’t stick to sports.

by Jason Fry on 27 August 2020 12:56 am You know the thing about moral victories in baseball, right? Namely, that they don’t exist. You were down 8-1 and gallantly came back and showed fight and lost 8-7? Here’s a pat on the head, because that’s called a loss.

Well, Wednesday night’s game against the Marlins, because of course it had to be the Marlins, was an immoral victory. The Mets won, but it felt like they’d lost and I was thoroughly mad at them despite the final score.

Jacob deGrom started, because of course this disaster had to involve poor Jacob deGrom, to whom pretty much the exact same thing happened last start. And he was … I don’t know, we’re running out of superlatives for deGrom by now. I could wax lyrical about the power and the command, I could strain myself invoking Seaver and Gooden and Santana, and your eyes would glaze over because you’ve heard it and read it before. Yeah yeah, you’d think, I get it. He was Jacob deGrom. And there it is: He was Jacob deGrom, which in this case meant 14 Ks in seven innings and nary a sweat broken. By now the man is his own superlative.

The Mets followed one of their more embarrassing twin bills in team history by actually scoring runs — first one, then another, then somehow two more, and I actually made the mistake of feeling like the game was safe. Oh ho ho. Ah ha ha. Justin Wilson, normally one of the reliable relievers, came in and promptly gave up three straight singles while getting one out. The last single was a bit unlucky, a little parachute just over Jeff McNeil‘s glove, but the other two came on balls that were supposed to be down and stayed up. Wilson was excused further duty and on came Edwin Diaz, who once upon a time was an elite closer.

“Diaz is gonna fuck this up, isn’t he?” I tweeted, and told myself that was a clever reverse jinx, and in a minute I’d be able to retweet myself mockingly but happily. But my heart wasn’t in it. I figured he really was going to fuck it up, and he did. Diaz fanned Jesus Sanchez, yielded a scorching infield single to Jesus Aguilar that nearly put a baseball-sized hole in J.D. Davis and made the score 4-2, then walked Corey Dickerson to force in a run and make it 4-3.

By now the cardboard cutouts had come to life and were booing — even the dogs were howling for blood in a corrugated way — and Luis Rojas was growing more gray and stooped by the second where he stood morosely in the dugout. It was 4-3, Diaz had already fucked this up, and one skinny bit of further fuckuppery was all that separated deGrom from looking a little stern yet philosophical in his postgame Zoom and being deprived of another win by his teammates’ chronic ineptitude.

INTERIOR — COURTROOM

Judge: All rise.

[hubbub, rising and what-not]

Judge: Mr. deGrom, you are accused of taking a two-by-four to your co-workers in a disturbing workplace incident. How do you plead?

Lawyer: Your Honor, Mr. deGrom is a New York Met, and we have a short video montage we’d like introduced into evidence.

[said evidence is displayed]

Judge: Case dismissed.

With a 1-1 count on Brian Anderson, Diaz spiked a slider into the dirt and came off the mound a little gimpily. The trainer and Rojas came out, Diaz argued to stay in the game, trainer and Rojas correctly noted that he’d done enough, and he departed with some injury for which I haven’t yet seen a diagnosis, and the nature of which I honestly couldn’t give a shit about.

In 40-odd years as a baseball fan I have (mostly) learned to be reasonable and understand that everyone is trying, injuries and simple buzzard’s luck can affect outcomes, and one should never reach moral conclusions based on the outcome of anything so maddingly fickle as hurled balls and swung bats and lunging gloves. But eventually even the most rational fan has had enough, and I have had enough of Edwin Diaz. The ground is salted. He should become someone else’s problem to fix, or no one’s problem, and I do not particularly care which. Diagnose him with inability to pitch and put him on the 45,000-day IL. Edwino delenda est.

Poor Brad Brach inherited Diaz’s 2-1 count and threw two more balls, walking in yet another run. The walk and the blown save go on Diaz’s ledger, and in this one case baseball’s quirky rules are inarguably fair. Another deGrom masterpiece had been covered in fingerpaint and crayon, and I huffily folded my arms and waited for the rest of the disaster.

Which somehow didn’t come. Robinson Cano singled, Billy Hamilton replaced him, Wilson Ramos singled Hamilton in, Brach went back out there and got three outs, though one of them came when Jonathan Villar — who’s an excellent player except when the Mets are involved — slid head-first into McNeil’s foot instead of second base. He was called safe, but a crew-chief review showed he was out, since opponents’ shoes only count as bases on alternate Sundays under 2020’s let’s-all-shrug-and-do-shit COVID rules. It was kind of bullshit, the sort of injustice that one would have just grumbled mildly about in the pre-replay era, but I was willing to take it, and a couple of minutes later Miguel Rojas hit an initially scarily trajectoried but ultimately harmless fly ball and the Mets had somehow won.

The Mets had somehow won, but it sure didn’t feel like they had. Certainly they hadn’t deserved to. I still felt like booing.

The best thing to do, probably, is draw a curtain across this one and never think of it again. It didn’t make any sense, and your insisting it should have won’t make any difference. It’s just baseball, it’ll drive you crazy if you let it, and 2020’s already got that more than covered.

by Greg Prince on 26 August 2020 9:40 am If it had been at all delightful, Tuesday’s twi-night doubleheader at Citi Field could have been billed a Berra’s Delight. Anybody who could make sense of the nonsense at hand would have been admitted free. Or admitted at all.

Nobody is admitted to baseball games in 2020, of course. After fourteen innings of futility, nobody who somehow still continues to like the Mets should mind the stringent admission standards. If anything, security should be more careful about letting people who claim to be major league ballplayers enter the facility.

The ones dressed as Miami Marlins would have made it in based on this rigorous standard, never mind how unfamiliar or inexperienced they chronically strike us as. They played like big leaguers for the two seven-inning games that for this season constitute a doubleheader. They’re the ones who were worth the price of non-existent admission. They shut out the Mets not once, but twice. Not that any of us would have knowingly paid for such a result, but they looked pretty good.

The Mets looked the opposite. The Mets looked like not big leaguers. The Mets didn’t even look like the home team, not in the sense of a team that automatically gets last licks, though by the last of the second game, they sure looked licked.

We understand why the Mets batted first in the second game of the sweeping shutout the Marlins inflicted on them. It was the makeup for last week’s postponement in Miami. Was it last week? Maybe it was last year. The Mets were on a three-game winning streak. Yeah, that can’t be this year or this team. Either way, the Mets batted in the top halves of innings and wore their home pinstripes, yet otherwise looked unsuited to any professional baseball field. To be fair, when they batted last in the first game, they also didn’t look like they had the slightest clue regarding what to do while their runners stood on or near bases.

Also, it rained, just in case you wished you were there.

Game One was the one that got soaked and interrupted. Rick Porcello gave up four runs in three innings before the heavens tired of his efforts. When the skies cleared, Corey Oswalt was nearly flawless for four innings of relief, but it was for naught in the context of winning the opener. The Mets attempted to hit with runners in scoring position ten times. They were successful in none of those attempts.

Without ever leaving town, the Mets became the visitors in the second game, but we could recognize them easily. They were the guys still not hitting with runners in scoring position. This time they had fewer opportunities, but they made exactly as much of them. Just as Oswalt, a nominal starter, displayed hypercompetence in relief in the first game, Seth Lugo, the Mets’ most essential reliever for a couple of years, emerged as a top-flight starter. Or re-emerged, for those who can remember Seth keeping the Mets afloat in their last successful charge toward October, way back in 2016. Seth looked like he never left the rotation, setting down the Marlins in order three times over three innings.

Then, because it’s 2020, Seth was done for the night. There was some outstanding newspeak explanation for why Lugo, at 39 pitches and on more than a week of rest, couldn’t go out for the fourth. Too many “ups and downs,” Luis Rojas said. The phrase didn’t likely apply to the Mets as a whole, for they were noticeably lacking ascent Tuesday night.

Downs, however, they displayed in abundance. Recently reliable Jared Hughes allowed two runs in the fourth, which was like allowing four runs in the sixth-and-a-half, I guess, considering we had only seven innings to forge a tie. In the top of the sixthish, the lone semi-convincing Met threat of the nightcap went awry when pinch-runner Juan Lagares — oh, Juan Lagares is back (and wearing No. 87) — was doubled off first base; Luis Guillorme’s sizzling liner was caught by Miami first baseman Lewin Diaz with Juan on his way to second. Diaz was much closer to first base by then, so, yeah, double play.

After Rojas deployed multiple defensive machinations entering the bottom of the sixth — Lagares to center after running for Cano, who had pinch-hit for Rosario; Nimmo from center to left; McNeil from left to second; Guillorme from second to short — inept defense cost the Mets another run. To be fair, the ineptitude was a product of those Mets who hadn’t changed positions during the inning and it was revealed via the hyperaggressive offensive tactics of a single Marlin.

First, with Jeurys Familia pitching, Jon Berti walked. Then Berti stole second, as Ali Sanchez, starting his first major league game, couldn’t get a handle on the pitch Berti ran on. After an out was recorded (when Lagares neatly reminding us his glove is still golden), Berti sensed an opening at third base and took it. J.D. Davis was not playing close to the bag, thus, the Marlin reasoned, why not steal it? It wasn’t just that he stole it. He hopped a couple of times as Familia threw to Sanchez then dashed to his destination. A delayed steal. If you didn’t have a rooting interest, you would have admired the ingenuity of it all.

But you hadn’t admired nothin’ yet, for Berti soon took off on his third base-stealing romp of the sixth inning. Once more, Davis was nowhere within range of the baserunner, who by now had traipsed down the line toward home. When Sanchez, a 29th man on a 28-man roster in a makeup doubleheader necessitated by positive tests for a pathogen if ever there was one, took his sweet time lobbing a return throw to Familia, Berti had his cue. He took off for home. Then he stumbled. Then he barely kept his feet. Then he clumsily maintained his forward motion.

Then he scored, because that was the kind of night it was for the Mets. The Marlins didn’t hit with this particular runner in scoring position, yet he crossed the plate unimpeded, and did so damn entertainingly. Empty stands notwithstanding, the last segment of Berti’s journey cried out for the swelling strings of “The Gathering Crowds” and inclusion in the closing credits of This Week in Baseball.

Berti’s posterizee Sanchez was in the picture because Tomás Nido was on the nebulous injured list used for COVID-19. Though nothing specific was announced, it is easily inferred that either Nido or Andrés Giménez tested positive while the other player was determined to have been in close contact. Same equation for coaches Gary DiSarcina and Hensley Meulens, neither of whom is currently with the club. The collective absence of these four individuals reminded us of the serious undertones of the 2020 season. The bottom of the sixth reminded us how farcical baseball can appear these days when you’re on the wrong end of three stolen bases by one opponent.

No offense to Sanchez, who was transferred over from the Alternate Site for a day. That’s another 2020 thing. Nobody is called up to the majors, exactly. You’re sent over from shipping to help out in receiving. Well, Sanchez didn’t much help with receiving, but perhaps he’ll have better days. Or half-days. If it wasn’t him and his three innings of previous big league experience pulling caddy duty for Wilson Ramos in the nightcap, it would have been Patrick Mazeika, also called in from the branch office in Brooklyn to stand by and be ready in Queens. In a public health crisis, your usual backup catcher suddenly becomes the indispensable man.

Perhaps had this been a doubleheader of what we used to call normal proportions — nine innings apiece; team at home serving as the home team; it not getting late early (even with the second game starting at 9:40) — the Mets might have shaken off their dampness and stormed from behind in dramatic fashion. We might now be praising their eighth-inning thunder, their ninth-inning lightning, their indefatigable gumption no matter the weather. But this doubleheader, like all 2020 doubleheaders, was brought to you by 7 and 7, the official cocktail of improvised contingency planning. In these two seven-inning games, the Mets were downed twice, 4-0 and 3-0.

Whatever the Mets did Tuesday would have qualified as history, given that this was the first Met doubleheader of its kind, but it was also a throwback to a shade of darker franchise lore, for it was the first doubleheader in which the Mets were swept while zipped in 45 years. Because institutional memory is nowadays like a starting pitcher pitching into the fourth inning — something you don’t see much anymore — this fact was repeated robotically without context once it was shared by Elias or whoever provided it to the media. Here’s your context if you’re curious: when it last happened, on August 5, 1975, the Mets’ manager was Yogi Berra. When next the Mets played, the Mets’ manager was Roy McMillan, which is to say getting shut out twice in the same day (by the Montreal Expos, each time by a score of 7-0; also in a Tuesday twi-nighter, also in Flushing) used to get a manager fired. Well, that and his team stumbling along aimlessly…as opposed to stumbling along purposefully, which is what Berti did in the bottom of the sixth.

Berra’s Met legacy is not getting canned on top of getting swept while getting blanked. He’s Yogi Berra. He’s the manager who pronounced the Mets’ season not over in 1973 when it appeared to be and then presided over a startling rebirth. But that was 1973, which, it turned out, didn’t cut endless amounts of ice. The Mets weren’t good in 1974 and, though they were better in 1975, they weren’t what you’d objectively term splendid (56-53), and they weren’t remotely close to where they needed to be in August to compete for the division title, which was the only ticket a league punched for postseason in those simpler times. Despite how well Yogi’s best-loved lines hold up (“this is the part of our homestand where we go on the road,” you can imagine him explaining as the “visiting” manager Tuesday night), there isn’t always an adorably repeatable phrase to guide a skipper of a sinking ship around icebergs of mounting frustration and stubborn underachievement.

When Berra was fired, the Mets trailed first-place Pittsburgh by 9½ games with 53 games to go. McMillan was exactly the man to turn the ship around for a few weeks (his first win, on August 6, was shortened by rain). Then he wasn’t; the 1975 Mets finished 10½ behind first-place Pittsburgh. The 2020 Mets trail San Francisco for the final NL final playoff spot by 1½ games with 32 games to go, as all it takes to advance this year is claiming the second-best non-first/non-second place record…and completing the season with non-infected players. The Giants are the target today. Last week it was the Reds, I think. The playoff race is more fluid than a 7 and 7 whose rocks have turned to water. It not being over until it’s over still applies to Met seasons that aren’t over.

But if even the sainted Yogi Berra can be called out at home, I’d suggest Luis Rojas do whatever a manager can do with a compromised coaching staff and drill into his lads a few things about how to compete in every baseball game they play and how to win a bunch more than they have. At the very least, Luis, maybe let Lugo get up to set down more batters when he’s proving himself unhittable. What was it your predecessor from 1972 to 1975 said again? “When ya got one thing goin’ right when everything is goin’ wrong, ya don’t want everything to go wrong, especially when the top of the seventh is already the bottom of the ninth, and if you’re playin’ the ninth, there’s already a runner on second, and then ya know you’re never gonna get the hit ya need.”

Something like that.

by Greg Prince on 25 August 2020 6:23 am Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

One must wait until the evening

To see how splendid the day has been

—Sophocles

In the film Defending Your Life, Albert Brooks stars as Daniel Miller, a Californian who dies in a car accident and is sent to an odd place called Judgment City, a town that, if nothing else, lives up to its name. While in Judgment City, Daniel will be judged for how he used his lifetime on Earth, with a tribunal examining ‘x’ number of the days he lived, before determining whether he moves forward in his existence or goes back to start over as another person. In Daniel’s case, he will have nine of his days critiqued.

Having just laid out the premise, I realize that if you haven’t seen Defending Your Life, you might not get a sense of how funny this movie is. Spooky, thought-provoking and suspenseful, too, but it was written and directed by Brooks, so there’s no issue classifying it as a comedy if you need to apply a label.

If I need to apply a label to Jose Reyes, I have no issue going with “my favorite player,” certainly during the bulk of his playing career, including today’s spotlight year of 2007 (speaking of spooky). From 2003 through 2018, in a Mets uniform and to varying extents when he donned other, more transitory garb, he carried the banner and I carried a torch, sans pitchfork. I adopted him as My Guy when he was barely out of his teens and I stuck with him in that role until he approached the age I was when I first heard of him. There’s roughly a twenty-year difference between Jose and me. Had I stopped to consider the incongruity of someone around 40 getting proprietary about the fortunes of someone around 20 — someone I’d never met and someone, at least to date, I never would meet — maybe I never would have grown so attached. But sports doesn’t have to add up. It just has to offer the promise of happiness

Deciding Jose Reyes was My Guy usually did that. This was a kid who I can’t imagine as anything but a favorite player, if not mine, then that of those innately delighted to get excited. Jose came to us, on the last day that he was 19, with a set of wheels we were told would steal our breath as he stole us bases. If I could keep up with him, I could get on board with that.

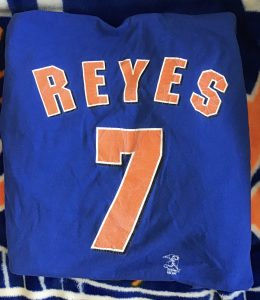

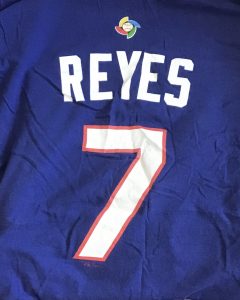

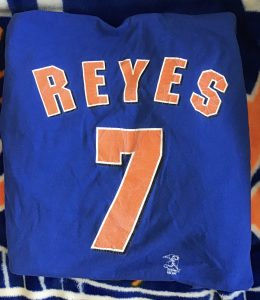

I did. I cheered his arrival on June 10, 2003, in about as cheerless a year as the Mets have managed in this century. Not too many weeks into his career, I swung by the Mets Clubhouse Shop on 42nd Street in search of a pick-me-up, which for me meant a player-number t-shirt. Those are my speed. Jerseys have always struck me as extravagances, even in their natural habitat, the ballpark. Perhaps it’s because I didn’t grow up at a time when regular people wore them. It was a big deal to see the drummer in some rock band wearing one. Otherwise, they were for players. By the late ’90s, however, they became popular to the point of de rigueur. Yet they didn’t connect with me. No pockets in this, the cell phone age, seemed impractical. If it’s cold, the jersey’s gonna be under my coat and nobody will see it. If it’s hot, I’m gonna take it off and stuff it in my bag. Others may enjoy their jerseys, and, as my mother might have said, wear them in good health.

The player-number t-shirt (don’t call it a “shirsey”) is of greater utility to me. I don’t need a game to wear it. I like when one comes up in rotation. A good, random wearing can create a conversation out of nowhere in most any situation. And should the player in whom I invested a fraction of the cost of a jersey be traded, leave as a free agent or somehow lose my favor, I simply take it out of rotation. Or not. Some t-shirts have been in my rotation three times longer than Jacob deGrom has been in the Mets’. (I’ve had a deGROM 48 since 2016.)

That afternoon in late July of 2003, expanding my lunch hour as long as seemed feasible, I made my way toward the back of the Clubhouse Shop. Past the discounted stacks of ALOMAR 12s and VAUGHN 42s and other detritus of an era that never did take off. I needed to publicly affiliate myself with a fresh Met. VENTURA 4 I discarded in 2002 when he showed up at Shea wearing steel gray with “NEW YORK” across the chest and beat us a game. I did the same to HUNDLEY 9 in a 1999 show of loyalty to PIAZZA 31. PIAZZA 31 remained a stalwart in my t-shirt drawers as of ’03, but it needed contemporary company. REED 35, BAERGA 8, ORDOÑEZ 10, OLERUD 5 had all been retired to the folded piles where I direct all shirts I deem no longer operative…and yes, I liked Carlos Baerga enough to wear him for a while. ALFONZO 13 was, of course, timeless (and is still in rotation to this day), but Fonzie was masquerading as a San Francisco Giant in 2003. That afternoon in late July of 2003, expanding my lunch hour as long as seemed feasible, I made my way toward the back of the Clubhouse Shop. Past the discounted stacks of ALOMAR 12s and VAUGHN 42s and other detritus of an era that never did take off. I needed to publicly affiliate myself with a fresh Met. VENTURA 4 I discarded in 2002 when he showed up at Shea wearing steel gray with “NEW YORK” across the chest and beat us a game. I did the same to HUNDLEY 9 in a 1999 show of loyalty to PIAZZA 31. PIAZZA 31 remained a stalwart in my t-shirt drawers as of ’03, but it needed contemporary company. REED 35, BAERGA 8, ORDOÑEZ 10, OLERUD 5 had all been retired to the folded piles where I direct all shirts I deem no longer operative…and yes, I liked Carlos Baerga enough to wear him for a while. ALFONZO 13 was, of course, timeless (and is still in rotation to this day), but Fonzie was masquerading as a San Francisco Giant in 2003.

“Excuse me,” I asked the clerk, “do you have any Jason Phillips t-shirts?”

My nascent affection was up for grabs a little. Phillips had been a Met a little longer than Reyes to that point and had earned my admiration in a season when I mostly grumbled at every other Met. Jason Phillips had played a competent first base. He was hitting over .300. He modeled the Goggles Paisano specs. I thought PHILLIPS 23 deserved first shot at my wallet.

There was no PHILLIPS 23 in stock. I can’t say if much was ever manufactured. Ah, but REYES 7, the latest shirt for the latest thing, that they had.

Sold.

***By the dawn of 2007, my judgment concerning Jose Reyes was a) he was the most wonderful player in baseball, and b) I really liked wearing REYES 7 on my back. My Guy. My shirt. My, my, how he could hit and field and run, especially run. No Met had ever put together the speed game as Jose had, especially once he shook off the injuries that conspired to slow his departure from the starting gate in 2003 and 2004. When not assigned to the DL (usually with a hamstring problem, the burden of a fast player, I figured), he was out there doing when they said he’d be doing when word surfaced from Binghamton in 2002 that he was gonna come up and blow everybody away. The natural shortstop even overcame an unnecessary shift to second base amid the misguided Kazuo Matsui experiment and retained his potential. Not every Met of promise overcame the obstacles the Mets inevitably placed in his path.

Come 2005, Jose Reyes broke through in earnest. After shaking off a case of acute unfamiliarity with the strike zone (his first walk came in his 120th plate appearance), he began rounding into the offensive threat the Mets had in mind when they signed him at age 16 out of the Dominican Republic. Jose turned 22 in 2005, a year when he played in all but one game, leading the National League in stolen bases and the majors in triples. These are the most fun things a baseball player can lead a league or two in. It means you’re fast, which is far more fun than slow (my affection for the plodding Jason Phillips, who’d since been traded, had mostly faded). It mean you’ve gotten on base regardless of your comfort with taking four balls. It means you certainly got to first base and you didn’t feel confined to it. Quite possibly first base was merely the first third of our your immediate journey, in which case you were three-quarters home after hitting the ball.

Steals and triples. It’s impossible to not smile at those. It’s impossible to not smile when creating them. Jose Reyes smiled a lot in 2005. He smiled way more in 2006. We all did, as the Mets raced to a divisional lead in April and put the field behind them for good. As June arrived, Jose was on the cusp of stardom. Before June was over, he lit up the galaxy.

June 2006 was the month of The Road Trip. There’ve been many Met road trips since 1962. This, however, was The Road Trip, the 9-1 romp through L.A., Phoenix and Philadelphia that eliminated all Phillies, Braves and doubt. What made The Road Trip singular above all road trips in Mets history was the way the Mets went to town on all these teams they visited. In their nine wins, the Mets scored in the top of the first every day and/or night; perhaps both.

Say, do you recall who was the Mets’ leadoff hitter in 2006? The Met who would have gotten just about every first inning off to a rollicking start? Why, yes, it was prototypical 1970s/1980s leadoff hitter Jose Reyes, the switch-hitter who could steal and triple better than anybody, relatively modest accumulation of walks notwithstanding. In every game Jose played on The Road Trip, he scored. In every game Jose played on that trip, his team won. By the end of the week The Road Trip concluded, Jose shared National League Player of the Week honors with David Wright.

Then Reyes went right out and had an even better week. It was the week when Jose tucked a cycle into a massive hitting and scoring streak, and the cycle was almost beside the point. I mean, sure, a leadoff homer, a double, a triple that became a run on a wild pitch and a single is a big effing deal. But it was what happened after the single, in the bottom of the seventh against Cincinnati at Shea on June 21, that was bigger.

What happened was…

JOSE!

JOSE-JOSE-JOSE!

JOSE!

JOSE!

It caught on that Wednesday night, the soccer-style singing in honor of our striker, the player whose job it is to score. Fútbol and béisbol may operate quite differently, but this beautiful player playing as beautiful a game as any Met ever had over a stretch of weeks had Mets fans spanning the globe in search of the most appropriate way to say, ¡Gracias, José! What a kick.

The National League named Jose Reyes its player of the week for a second consecutive week. All the weeks seemed to be his. Before the Mets embarked on The Road Trip, on June 4, Jose was batting .248. By the time they were traveling men again, specifically after they took their second of three in Toronto on June 25, Jose was batting .302. In 18 games, he recorded 37 hits and crossed the plate 25 times. The slash line was .468/.512/.785. The Mets went 13-5. Jose was going to the All-Star Game for the first time.

The joie de Reyes of it all transcended the numbers and the honors. The energy. The excitement. The idea that if Jose got up, Jose could get on, and that if Jose got on, Jose could get us where we wanted to go and give us a joyride the whole way around the bases and up the standings.

Of course Jose Reyes was my favorite player. I was stunned he wasn’t everybody’s favorite player.

***Before 2006 was over, Jose Reyes would homer thrice in one game, produce an inside-the-park homer in another game, and rack up all the Jose Reyes numbers a person would expect after prolonged exposure to the most wonderful player in baseball. Tops in triples again, with 17. The most steals, with 64. Way more than 100 runs. A little shy of 200 hits. Significant MVP support. And, oh yes, the acknowledged catalyst for the National League East Champions. The Mets hadn’t won a division title since 1988. Jose Reyes was five then. It had been a while.

With Jose leading off, Paul Lo Duca batting second and the demolition firm of Carlos, Carlos and David up behind them, it seemed impossible to imagine a pitching staff capable of stopping the 2006 Mets from capturing their first World Series since 1986. Jose Reyes was three then. It had been a while. The Dodgers couldn’t stop the Mets. We swept them in the NLDS. Next, Fox hyped, it would be “Albert Pujols and the Cardinals” versus “Jose Reyes and the Mets”. Those other guys we had were solid. A fistful of them were stars. I had a name/number shirt for three of them. But Jose Reyes was our headliner as we became national prime time programming, the Met above the marquee. I’d had his shirt since 2003, when we lost 95 games. Three long years had streaked from home to third in almost no time at all. Four more wins, and we’d be in the World Series. “Jose Reyes and the Mets” versus whoever was leading whoever from the American League. Bring ’em on. It seemed almost academic that Jose Reyes and the Mets would be there and win all of it.

It’s still been a while since we won the World Series, as you know. Still since 1986. There needed to be more to the Mets in October of 2006 than a hellacious first five hitters — and there was…but not enough, as it turned out. The last time the Mets won in ’06, in Game Six of the NLCS, it was Jose Reyes who put them on top ASAP with a leadoff homer versus Chris Carpenter. That win kept us alive. Jose went 3-for-4 in the Game Six that rarely gets mentioned in the annals of glorious Met Game Sixes. As clutch performances go, it was pantheon-worthy as anything Jose’s Met predecessors posted in the must-wins of 1986, 1988 or 1999.

We fell short in Game Seven, but that was, to my Jose-ish optimistic outlook of the moment, almost OK. To clarify, it wasn’t OK in and of itself, and it still isn’t OK. I really wanted the Mets to go that World Series and win that World Series. It’s still the one in my heart of hearts that got away more than any of our now seven cigarless postseason appearances. Yet it was OK in the sense that, clearly, we were too good to not be back in 2007. We had won 97 games. We had all that power in Beltran, Delgado and Wright. We would have our starting pitching healthy again, which we didn’t in the playoffs. And, of course, we would have Jose Reyes leading off. With ESPN choosing our Opener at St. Louis as its Sunday Night showcase, Jose would be the very first batter of the entire next baseball season. Talk about having a leg up on the competition. No, two legs. The two fastest, most dynamic legs anywhere. We fell short in Game Seven, but that was, to my Jose-ish optimistic outlook of the moment, almost OK. To clarify, it wasn’t OK in and of itself, and it still isn’t OK. I really wanted the Mets to go that World Series and win that World Series. It’s still the one in my heart of hearts that got away more than any of our now seven cigarless postseason appearances. Yet it was OK in the sense that, clearly, we were too good to not be back in 2007. We had won 97 games. We had all that power in Beltran, Delgado and Wright. We would have our starting pitching healthy again, which we didn’t in the playoffs. And, of course, we would have Jose Reyes leading off. With ESPN choosing our Opener at St. Louis as its Sunday Night showcase, Jose would be the very first batter of the entire next baseball season. Talk about having a leg up on the competition. No, two legs. The two fastest, most dynamic legs anywhere.

I was gonna need another shirt. The first REYES 7 was kinda worn by now and the thick name-on-back lettering from 2003 never bothered mimicking the Mets’ font. In 2003, the Mets and high quality didn’t really mesh. My next REYES 7, for 2007, would be orange fabric, thin blue printing. Sleek, just like Jose.

***Until 2007, there is no need for judgment beyond routine approval and extraordinary serenading. Jose Reyes has been a big leaguer for four seasons, two when he was just getting going and two when he was all go. Why would 2007 not be a continuation, an acceleration of the Jose Reyes who had overtaken the baseball imagination, the Jose Reyes who was every bit as fantastic as I decided he was going to be?

Yet this is where I am compelled to detour to Judgment City. It’s The Road Trip I’d rather not take. I’d rather continue to list Jose Reyes accomplishments and punctuate them with grand anecdotes. Here’s all Jose Reyes did in all the years to come, here’s how marvelous it felt, try not to trip over the trophies.

That’s not quite what happened. I’m not sure I understand what happened. He still compiled some pretty shiny numbers and I can still point to some pretty impressive accomplishments and, if you cover one eye and read the chart with as generous an interpretation as you can muster, you’ll notice the Mets of the seasons directly following 2006 were quite the contender, pursuing their collective goal clear to the very end of their schedule, and who doesn’t relish a smashing pennant race?

Both eyes open, it wasn’t nearly such an unfettered success story, not for the Mets and, despite my never wanting to give an inch, not for Jose Reyes. As clear-eyed a fan as I believe I’ve always been, I’m reflexively blinded my loyalty to my inner-circle absolute favorite players. There’ve been only a handful of those in my more than half-century of rooting for the Mets. Jose Reyes is one of those.

In 2007, I finally accepted that my favorite player could do wrong. And it grudgingly occurred to me, as Jose Reyes neared the quarter-century mark himself, he might not always get better. There might be a ceiling for Jose Reyes. In fact, I might have already experienced it.

What a drag it is getting old.

***In the spirit of Albert Brooks’s conception of Judgment City, I will now examine seven days from Jose Reyes’s 2007 season — seven for No. 7 from ’07. It is not up to me to pass judgment, exactly, but maybe I can get a better grip on where things began to go at least a little awry.

DAY 1: APRIL 6

Jose leads off the Mets’ series opener at Turner Field by tripling. He scores on a Lo Duca fly ball. It’s what we call a Reyes Run. The Mets are on a run already, having swept the Cardinals for a measure of revenge and now they’re sticking it to the Braves. Jose triples twice, scores twice, collects three hits and drives in four. The Mets win, 11-1. They’re 4-0. See, not quite going all the way in 2006 really was sort of OK because these Mets are too good to not be back; let’s call Game Seven a teachable moment. Jose is too good to not be back. When April ends, Reyes is batting .356. The leadoff hitter none other than Bobby Cox terms the best since Rickey Henderson has 18 RBIs to go with his 17 steals, 9 doubles and 5 triples. Sextuple that to reflect an entire season…well, let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Let’s just revel in April. For this first 2007 month of production, Jose Reyes is named National League Player of the Month. It’s the award he wasn’t given the previous June. He lost that one to David Wright, so we’ll allow it.

DAY 2: MAY 29

The Mets are actually a little choppy as April becomes May. Their solution is to chop off their hair. As a team-building exercise, they almost all opt for crewcuts. (Guys, huh?) Jose is a little late to the barber party. He has such nice curls, but eventually he gets in on the noggin-shaving, and whether one thing has anything to do with another, being shorn at Shea seems to do the trick. By late May, the 2007 Mets are rolling like their 2006 predecessors. The Giants find out how hairy it can be facing off against Jose when he has nothing extra up top weighing him down. In a game that enters the bottom of the twelfth, with San Francisco ahead, 4-3, Reyes leads off against the closer of blown leads past, Armando Benitez. Seven years since J.T. Snow and Paul O’Neill convinced us to cringe, it is surprising to realize somebody is still trusting Armando Benitez with save situations, but at this point in his managerial career, Bruce Bochy is not yet a certified genius. Armando is his man. Fortunately, Jose is ours. Benitez walks the shortstop with whom he briefly shared a clubhouse four years earlier. The count had gone to three-and-two and…yeah, we recognize Armando Benitez. We also recognize Reyes on first. First? Make that second, for Jose has goaded Armando into a balk. Endy Chavez then bunts Jose to third. Carlos Beltran grounds out, and Jose has to stay put, but since when does Jose Reyes stay put? He dances off third. He is Lola from “Copacabana”. She would merengue/and do the cha-cha… And while Armando Benitez tried to concentrate on getting a third out, Jose Reyes has teased from Benitez’s ever-tender psyche a second balk. Jose can dance home. The game is tied. Moments later, Carlos Delgado homers, and the Mets have won, 5-4. Jose Reyes and the Mets are 33-17, five games up on the Braves, eight ahead of the Phillies. Who the hell is going to stop Jose Reyes and the Mets?

DAY 3: JUNE 15

As temporally dissonant as it is to grasp Armando Benitez is still around in 2007, how about getting a load of that load Roger Clemens? Clemens’s major league career dates back to Jose Reyes’s infancy. His infamy needs little introduction to Mets fans. We might have thought we were done with him when he stopped pitching for Houston after 2006. But the Rocket was always retiring and reneging. Little wonder that Suzyn Waldman bleated on an otherwise lovely Sunday afternoon that Clemens was returning from Texas to pitch in the Bronx (“of all the dramatic things I’ve ever seen!” she shrieked upon spotting the heretofore inactive 44-year-old in “George’s box”). It was too late in the season for Joe Torre to steer his delicate ace away from Shea Stadium; we’d already taken two of three in the civilized portion of the Subway Series. We were getting him on the other side of the Triborough. Perhaps, having been out of New York since 2003, Roger was looking forward to coming up and in on Mike Piazza again. Alas, Mike was in Oakland and the Mets he was encountering had already given themselves their own close shave. Leading off the first game of the second part of the 2007 intracity six-pack, Jose Reyes informs Roger Clemens much of the Metropolitan Area isn’t nearly as worked up over his presence as Waldman was. Jose singles. He doesn’t score, but neither do any Yankees taking on Oliver Perez, who demonstrates an uncanny knack for confounding the Braves and Yankees (where were you in 1999 and 2000, Ollie?). It’s nothing-nothing until the third when speed kills and thrills. The more the better for the Mets. Jose now has a running mate, Carlos Gomez. The rookie’s not as skilled as Jose with the bat — Jose received a Silver Slugger the year before — but he can bunt, which does to get on, and he can run, which he does to steal second. Jose then singles home this third Carlos in our arsenal to break up the Rocket’s shutout. In the fifth, Jose homers. Ollie goes eight. The Mets win, 2-0. In case there’s one more Series between these teams four months hence, Roger can take note that the Mets have a couple of players who can run rings around him.

DAY 4: JULY 6

The first-place Mets are a little sluggish. It happens to the best of first-place teams. Maybe the Mets haven’t been playing like the best of first-place teams, but they are in first place. The All-Star break is almost here. A Friday night in Houston may not be the best spot to keep one’s energy up, not even for the player who’s usually the most vibrant in the land. It’s the eighth inning. There are two out. Jose Reyes is up, with the Mets trailing by four. He grounds to third baseman Mike Lamb. Jose runs toward first not exactly like a lion. It’s too hard to not notice. A fan might choose to look the other way. A manager does not. Willie Randolph removes Jose Reyes for not hustling. The hustle is a dance we are sure Jose knows better than Lola knows the merengue or cha-cha. No, no runner should take a ground ball for granted (Lamb bobbled it but had an easy play), yet, a fan could rationalize, perhaps Jose has to take his breaks where he can get them. He’s not going to have the All-Star game off.

DAY 5: JULY 10 DAY 5: JULY 10

Jose Reyes is indeed back at the All-Star Game. It’s cause enough for me to order a black REYES 7 tee from the event, replicating the NL’s batting practice jerseys (it never really fits). For a second consecutive year, he is voted the starting shortstop. For the first time, however, he will play. In 2006, ex-Met Mike Jacobs had stepped on Jose’s foot in the series before the break and, out of an abundance of caution, Reyes’s services were withheld from the Midsummer Classic in Pittsburgh. Not this time in San Francisco. If Jose is not front and center, he is appropriately adjacent. The star of the pregame proceedings is the player for whom it is said All-Star games were made, Willie Mays. Willie was a Giant in San Francisco, you know. After he was a Giant in New York, before he was a Met in New York. He was an All-Star the whole time. Willie, naturally, had the honor of throwing out the first ball. Actually, the honor belonged to the ball. Anything Willie Mays touched was elevated. And to whom did Willie decide to deliver that first pitch? Who of all the All-Stars available to him did the once-upon-a-time speedster/slugger from the National League team in New York choose as his personal catcher? Why, Jose Reyes, of course. Who else? In the middle of 2007, with Jose Reyes presumably in the midst of a career path that could conceivably land him on a plane with some of the greatest all-around shortstops to have ever played the game, it doesn’t seem incidental to see the 24-year-old paired with the No. 24. Not only does Jose catch the ball from Willie, Willie signs the ball for Jose. “I’ll save that ball all my life,” Jose says. I’ll save the image from that night comparably long.

DAY 6: AUGUST 22

In the fifth inning against the Padres at Shea Stadium, Jose Reyes singles with one out. He takes second when recent acquisition Luis Castillo grounds to first. David Wright walks. Then, with Carlos Beltran at bat, they execute a double steal. Wright can run, you know. Reyes can run, we definitely know. The swipe of third is Jose’s third steal of the night — and his 67th of the season. “JOSE! JOSE! JOSE!” and then some resonate in the Flushing night. We are giddy to be present for the setting of a new one-season record. Roger Cedeño had stolen 66 bases in 1999. It was the most by any Met until now. Now, it’s Jose establishing a new mark with 37 games to go. Who knows how high the record will sit by year’s end? When Carlos drives in both Jose and David, we’re more concerned that the Mets have closed the gap on the Padres to 4-2. It’s a shame we’re losing this game and will lose it, 7-5, despite Jose’s exploits. The Mets still haven’t fully broken free of their competition. The Phillies are in second place, five games out. Atlanta’s right behind them, six out. Still, we’re in pretty good shape. And with Jose batting over .300, keeping his OPS over .800 and piling up those bags, any glitch detected in the program to repeat as division champs and exceed 2006’s accomplishments certainly isn’t his fault.

DAY 7: SEPTEMBER 15

This thing is in the bag. Basically. There was a scare in late August, when the Mets went down to Philly and Jimmy Rollins made like the Devil in a Charlie Daniels song to instigate a four-game sweep, but we’d recovered since then. We’d gotten Pedro Martinez back from a five-month DL stint and at Shea on a beautiful Saturday afternoon, Pedro’s nursed a 3-1 lead through six. We beat the Phillies today and everything will be fine. We should have beaten them last night, but there was a bad call, and the bullpen didn’t do us any favors, and, well, c’mon, get over it. We came into Saturday 5½ up on the Turnpike interlopers. Just take care of business every day. Most days that means Jose doing Jose things. I wonder, though, if Jose is pressing. Fouled out in the first. Popped out in the second. Singled in the fourth, but got himself thrown out trying to steal. The average is below .300. Seemed impossible in April to fathom that it would take that kind of dip, but it’s a long season. Just relax. Jose is Jose. The Mets are the Mets. We have a Magic Number. In the bottom of the sixth, Jose walks. He can do that, pitchers are discovering. Then Jose steals. That’s something pitchers discovered back in 2003, with ex-Met Kane Davis, now of the Phillies, the latest to be reminded. Jose has well over 200 steals in his career. He’s second to Mookie Wilson all-time among Mets, and it’s only a matter of time before Jose passes Mookie for a career like he passed Cedeño for a season. Anyway, we have a 2-1 lead, we have Reyes on second, after which we have Castillo walking, which paves the way for Wright to bat in this inning. David’s been hot as a pistol. This is a terrific situation to build the lead, to get a little insurance. The great thing about Jose being on second is he doesn’t need to be on third to score when a superb RBI man like David is batting. I love watching them ply their respective crafts together, whether on the left side of the infield or from various stations on the basepaths. David at third, Jose at short. David at the plate, Jose on second. The two of them doing their thing in sync. This is as optimal as it gets.

***And that’s where I wish Day 7 goes blank, but it doesn’t. I know what happens next. Jose Reyes, a five-year veteran, a two-time All-Star, the best in the game at what he does, takes off for third base on the first pitch David Wright sees. Chris Coste grabs it and fires it to Greg Dobbs. Reyes is out easily. Threat over. Inning over. Pedro Martinez gives way to the bullpen.

The simple invocation of the Mets’ bullpen in September underscores that if one is anxious to parcel out blame for what was about to happen to the rest of the 2007 Mets’ season, one would have to bring plenty of postage. Wright was awesome in September. So was Beltran. Moises Alou defied time and crafted a thirty-game hitting streak. They’re absolved. Nobody else is. The Greatest (or Worst) Collapse in Baseball History was underway. We didn’t know it on Friday night when we lost to the Phillies, but we began to sense it on Saturday when the 3-1 lead became a 5-3 loss. It was followed by a 10-6 defeat on Sunday, and the hinges were clearly coming loose on the Mets being a prohibitive favorite to return to the postseason because all bets were off.

From seven games ahead with seventeen to play on September 12, the Mets finished one behind on September 30. It would be convenient to say it all turned on Jose Reyes’s misguided attempt to steal third base in the sixth inning on September 15, but it would also be a stretch. Jose Reyes and the Mets spent most of 2007 in first place as team; Jose Reyes and the Mets fell out of first place at the end of 2007 as a team.

Jose’s September was April’s inverse. He would steal again on September 15, in the ninth. It was his 78th bag of the season. It was also his last. The speed game went into hibernation. Then again, it’s impossible to steal second (or third) when you don’t reach first, and Jose basically stopped doing that. His September 2007 numbers were dreadful: a .205 batting average; a .279 on-base percentage; one triple; five steals after five months when he never stole fewer than ten bases. Jose’s September was April’s inverse. He would steal again on September 15, in the ninth. It was his 78th bag of the season. It was also his last. The speed game went into hibernation. Then again, it’s impossible to steal second (or third) when you don’t reach first, and Jose basically stopped doing that. His September 2007 numbers were dreadful: a .205 batting average; a .279 on-base percentage; one triple; five steals after five months when he never stole fewer than ten bases.

Yet, for me, it wasn’t his contribution to the descent from first place to second, his personification of the collapse itself, that bugged me. It was that when he took off for third in the sixth on the Fifteenth, I was livid with him for the first time in his career. What kinda stupid…? He was no longer Jose Reyes above reproach. He wasn’t running from pedestal to pedestal, inevitably safe in my mind. He had become, incrementally, just another Met letting me down. Mind you, I didn’t drop him from his slot as my current favorite. I didn’t even care that he danced too enthusiastically for the Marlins’ taste in Game 161 that year, allegedly firing up the opposition during a Met blowout, first inciting a weird-ass brawl (with coach Sandy Alomar getting involved), then stoking the Marlins to jump ugly on T#m Gl@v!ne in Game 162 because motivation is so effortlessly easily converted into runs. I didn’t even notice the dancing from my seat in Mezzanine. Lastings Milledge had just homered and Jose was happy for him and, as I understand it, the two of them tangoed in front of the home dugout instead of inside it; something like that. They’d be scolded for their violation of unwritten rules, for waking up the somnambulant Fish, for noticeably enjoying an uplifting moment amid what had been a crisis atmosphere.

Today that sounds even more ridiculous than it struck me in 2007. It may have been the first instance of Jose Reyes having been born too soon.

***September’s dive notwithstanding, Jose Reyes’s overall numbers for 2007 were outstanding, as they were again in 2008. One of those Met injuries that doesn’t get solved in the span you think it will sidelined him most of 2009, but he was back in 2010, making his third All-Star team. In 2011, when his hamstrings didn’t nag, he was otherworldly, winning the first batting title any Met had ever won. The Jose Reyes of June 2011 was what you would have expected to see had you been asked to project five years forward from June 2006. Sadly, the Mets weren’t anywhere near as good as they’d been in 2006 and, sadder to me, Jose wouldn’t be around Citi Field, except as a visitor, for nearly a half-decade after 2011. He and I were older, maybe wiser. He was definitely richer. The Marlins got over that fight with him and signed him for a ton of money. Every time he came back to Flushing in 2012, I applauded him heartily and only sort of hoped the Mets would get him out.

The only thing Miami didn’t give him was a no-trade clause (they’re notorious for that), and after a year, Jose was a Toronto Blue Jay, which he didn’t seem to mind. We saw him in Interleague play in June of 2015, then as a Colorado Rockie that August. He seemed to mind that next identity, but by then, with the Mets in first place for the first time since 2008, I’d mostly moved on from thinking about Jose Reyes. I still had my REYES 7 t-shirts, five in all, but none of them was as go-to as any used to be. I had two HARVEY 33s and still sported WRIGHT 5. I even threw a TEJADA 11 into the mix as part of my shortstop separation process post-Reyes. (It also never fit.) The only thing Miami didn’t give him was a no-trade clause (they’re notorious for that), and after a year, Jose was a Toronto Blue Jay, which he didn’t seem to mind. We saw him in Interleague play in June of 2015, then as a Colorado Rockie that August. He seemed to mind that next identity, but by then, with the Mets in first place for the first time since 2008, I’d mostly moved on from thinking about Jose Reyes. I still had my REYES 7 t-shirts, five in all, but none of them was as go-to as any used to be. I had two HARVEY 33s and still sported WRIGHT 5. I even threw a TEJADA 11 into the mix as part of my shortstop separation process post-Reyes. (It also never fit.)

In October of 2015, while we were ensconced in a World Series state of mind, Jose Reyes allegedly threw his wife into a shower door at a resort in Hawaii. I say “allegedly” because a criminal case was dismissed, but it was widely acknowledged what happened. Maybe not why it happened, but what difference did that make? Who does that?

Who clings to a favorite player after that? “Not me,” I’d like to say, though I do have a talent for compartmentalization. I still loved the Jose Reyes who hit and ran and made sizzling, on-target throws from deep in the hole. I still loved the Jose Reyes who made me want to buy those shirts and keep wearing them. The Jose Reyes who absorbed a domestic violence rap from Major League Baseball I wasn’t crazy about. I certainly wasn’t processing his release from the Rockies and suspension from baseball as an ideal avenue to a reunion with the Mets.

But David Wright’s back gave out and the Mets needed a left-side infielder. Surprisingly if somehow not shockingly, here we were again in the summer of 2016, the Mets and Jose, me and Jose. And it was weird. For some Mets fans, it was repulsive. I respect that. If someone who threw his wife into a shower door is who you never stopped seeing when Jose Reyes came to bat, I’m not gonna suggest covering one eye. I mostly saw that character for a while myself.