The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 14 August 2020 11:15 pm The Phillies played the first half of Friday night’s game like they were recreating a Benny Hill skit. The Mets once again showed resilience, losing a lead and promptly regaining it on back-to-back homers. Luis Guillorme continued to reward the Mets for finally giving him playing time. Walker Lockett — summoned when Jacob deGrom was scratched with neck stiffness — pitched pretty well all concerned, with the glaring exception of one pitch to J.T. Realmuto, the wrong guy to make a mistake to in 2020.

It all went for naught, thanks to two moments where events were poised on a knife’s edge and then came down against the Mets.

In the sixth, with two outs and runners on first and second, Pete Alonso slammed a first-pitch fastball from Blake Parker. The ball sailed on an arc towards center, the deepest part of a not particularly deep park. Gone, I thought. So did Pete. It wasn’t gone. Roman Quinn snagged it just short of the fence. The Phillie fan cutouts kept smiling their cardboard smiles. Inning over.

In the ninth, Seth Lugo got into immediate trouble, surrendering singles to Quinn and Andrew McCutchen. But he fanned Rhys Hoskins and battled Bryce Harper, saddling him with an 0-2 count. His fourth pitch was a slider, low and on the inside edge of the plate. Harper smacked it into right field just in front of Michael Conforto, who fired a perfect strike to Wilson Ramos. Ramos caught it ahead of the plate, slung his hand back, and tagged Quinn’s fingers — about a second and a half after those fingers touched the plate. Ballgame.

There was more than that, of course. There was Billy Hamilton stealing second, then being far too aggressive in trying to advance to third, getting gunned down by an alert Didi Gregorius. There was the parade of Mets leadoff hitters who never came home, despite the Mets being loose in the Phillies’ normally less than dominating bullpen.

It stinks. But then, if you didn’t know baseball was an unfair game by now, I’m not sure what to tell you. It’s cruel and unfair and sometimes darkly comical, with virtue often going unrewarded and sloppiness often going unpunished.

It’s not much comfort, but I suspect this is the type of game that bothers fans more than players. By the time they’re big leaguers, players have been on the short end of such games dozens of times, if not hundreds. They get good at having short memories, at cultivating the ability to wash games like this one away and start anew.

We’re not so good at that. We look back at Alonso’s drive coming up short and Hamilton being too aggressive and Ramos being a touch too slow and we mutter and grumble — and then we look ahead to homer-prone Steven Matz vs. Aaron Nola in a teeny ballpark, and we mutter and grumble some more.

Wash it away. Start anew. If you can. Good luck.

by Jason Fry on 14 August 2020 10:35 am Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

The 1986 Mets laid waste to the National League, closed bars, got arrested, wrecked planes, raised a prodigious amount of hell and opponents’ ire, got into fights, won most of those fights, defeated the Houston Astros in a harrowing six-game series, then defeated the Boston Red Sox in an even more harrowing seven-game set.

It’s annoyingly hard to remember, now that New York is infested by hedge-fund bros with corporate-logo vests and Yankee hats, but in 1986 this was a Mets town. And few teams ever fit their towns better than the ’86 Mets fit New York City. Everyone from everywhere else hated the New York Mets, but the Mets didn’t give a fuck what you thought of them, because what was the point of being from anywhere else?

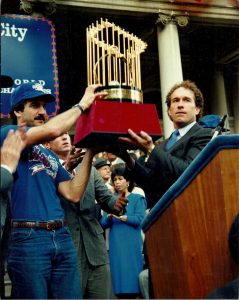

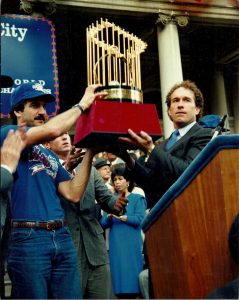

With the Red Sox done and no one left to vanquish, the Mets were given a ticker-tape parade and a ceremony on the steps of City Hall. Photos of the ceremony capture two ’86 Mets — the unquestioned leaders of the club — standing on either side of the World Series trophy they’ve hoisted into the air.

The man on the right is Gary Carter, the Mets’ tough-as-nails catcher and No. 4 hitter, a man with a sunny personality and a deep reservoir of faith. He looks like a kid at a church service — he’s wearing a jacket and tie and is shaven and scrubbed.

The man on the left is Keith Hernandez, the Mets’ tough-as-nails first baseman and No. 3 hitter, a man with a personality full of shadows and a deep reservoir of complications. He looks like shit — he’s unshaven and dressed in a cap, t-shirt and jeans. The surprise is that he somehow managed to find a belt. The man on the left is Keith Hernandez, the Mets’ tough-as-nails first baseman and No. 3 hitter, a man with a personality full of shadows and a deep reservoir of complications. He looks like shit — he’s unshaven and dressed in a cap, t-shirt and jeans. The surprise is that he somehow managed to find a belt.

Both men, as it happened, celebrated the night before. But Carter went home at a reasonable hour (or at least one assumes he did, and it’s a safe assumption), got up, got dressed, and got himself to Shea Stadium in plenty of time for the 10 a.m. police escort to Lower Manhattan and the parade down the Canyon of Heroes. Hernandez stayed up all night boozing it with Bob Ojeda, went home at 7 a.m., woke up at noon, and only made the ceremony because Met fans recognized him and Ojeda and lifted them over a fence. Odds are he’s exuding a radioactive cloud of hangover sweat, and that Carter has looked over at least once and thought, “C’mon, really?”

It’s like Goofus and Gallant from the old Highlights feature, except for one thing: Goofus is there where he’s supposed to be. Gallant did a whole bunch of things that Goofus should have done and maybe now wishes he had done, but they both made the ceremony. They’re both holding up that trophy. And if you know the ’86 Mets, Gallant doing the right thing wouldn’t have meant a damn thing without Goofus as his bookend, doing what had to be done.

That was the Keith Hernandez I knew, the Keith Hernandez I adored, and the Keith Hernandez I wanted to be.

Look, I loved Gary Carter — he was simultaneously a truly decent human being and a ruthless competitor, which gave his successes against the likes of Charlie Kerfeld the moral clarity of a good parable. But I couldn’t imagine being him, or wanting to be him. Carter was straightforward and sunny and religious, and even at 17 I knew I wasn’t any of those things.

Meanwhile, some writer — most likely it was Chris Smith of New York, who wrote a string of wonderful Hernandez features back in the day — called Hernandez the hero of every guy who’s out until 3 a.m. but still gets the job done at work the next day. Keith’s reaction: “I thought that was well put.” That I could understand and take to heart. And I did: When I was younger there were most definitely office days after long nights when I’d bull my way to bleary-eyed success and think, Seinfeld-style, “I’m Keith Hernandez!”

That’s not to diminish Carter. But fundamentally, there are Gary people and Keith people, just like there are Mick people and Keith people and Chuck D. people and Flavor Flav people and Luke people and Han people. And I realized pretty early on that I was a Keith person.

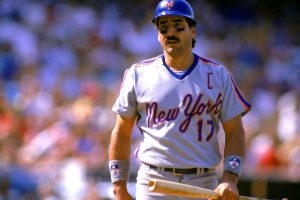

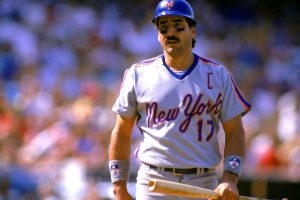

The C is for “complicated.” Next time they show Game 7 of the ’86 Series, stop and watch Hernandez’s crucial at-bat, the one in the sixth inning.

There he is staring out at Bruce Hurst with a combination of a surgeon’s concentration and a gangster’s impatient menace. He looks impossibly small and lithe compared with today’s players — today he’d be a fourth outfielder, maybe. When he was out of uniform his signature mustache struck me as distinguished, but that’s not the impression you got seeing it paired with an 80s mullet and unshaven face — staring out at Hurst, he looks like a pirate, or maybe a rock star.

The first pitch is called a strike; Hernandez reacts with indignant disbelief. Second pitch, bang! He pounces, that oddly long-armed swing uncoiling, and here come Lee Mazzilli and Mookie Wilson to cut Boston’s lead to 3-2. The camera jumps back to Keith on first base. He’s cool for a moment, standing there with Bill Robinson, and then the emotion overflows and he’s not so cool.

A first pump.

A yell.

That’s not enough, so one more of each.

“Yeah!” FUCK YEAH!”

That’s more like it.

We’re not done, though. The next batter is Carter, who hits a little flare that Dwight Evans rolls over in right field, leaving Hernandez caught in no-man’s land. He’s tagged out at second as Wally Backman scores the tying run. Being Keith, he starts hollering at umpire Dale Ford, as if Ford should have developed X-ray vision in anticipation of being blocked out. Ray Knight — Rusty Staub‘s successor as bodyguard/counselor to Hernandez — has to calm him down on his way into the dugout.

In a couple of minutes, you’ve been given a portrait of Keith Hernandez. Cool focus sharing space with fuming impatience, emotions boiling over, a bad idea not suppressed in time. That was Keith. But remember the context: all of that was the window dressing for a huge clutch hit. That was Keith too.

(And the rest? The blitzing through God knows how many watering holes in an all-night celebration? That was most definitely Keith. And so was getting to the parade on time, despite it all.)

All this seems preordained now that Hernandez is a fixture in the Mets booth and a New York icon. But it wasn’t — rather than arrive like a conquering hero, Keith Hernandez crept into town a stunned exile.

In 1986, William Nack penned an essential profile of Hernandez for Sports Illustrated, exploring the demons that drove him, denied him solace and also — cruelly — made him great. The story begins, as such complicated tales often do, with the father. John Hernandez was a first baseman who hit .650 his senior year in high school, good enough to be signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers. Playing under lousy minor-league lights in Georgia, he lost sight of a pitch, which hit him in the head.

His eyesight never recovered, dooming his career. So he taught his sons — Gary and his younger brother Keith — to play baseball. To call the elder Hernandez domineering would be to put it mildly: He’d berate his children for a single poor at-bat and give them written exams about defensive positioning.

Keith was the more promising athlete and tightly wound instead of happy-go-lucky like Gary, so he bore the worst of it. But his father was also an excellent teacher, and the best coach his son would ever have. Which he never let Keith forget — Nack chronicles boom-and-bust cycles of recrimination and rapprochement, with Keith complaining that he can’t stand the thought of his father watching his at-bats via a satellite-TV rig (which Keith bought), then needing him to diagnose a bad habit that’s crept into his swing.

(The story has a melancholy epilogue: John Hernandez died not long after his son’s playing career ended, with their issues largely unresolved.)

Hernandez battled insecurity and loneliness as a Cardinals rookie, overcame it with the help of veterans (Lou Brock and Bob Gibson were vital mentors, the first sympathetic and the second famously not), shared an MVP award, got married, got divorced, developed an infatuation with cocaine, kicked it, wound up in Whitey Herzog‘s doghouse, and was exiled to the hapless Mets in the summer of 1983.

His first reaction was to ask his agent if he had enough money to retire. Fortunately — for the Mets, for all of us, and for Hernandez himself — he didn’t.

Hernandez’s brother told him about the minor-league talent the Mets had in the pipeline. Staub took the new first baseman under his wing and told him that as a single guy he had to live in the city. And something wonderful happened to Keith Hernandez: Forced to become the on-field leader of a team that needed him, he found he relished the role and thrived in it, just as he found he loved New York and all it had to offer.

Instead of exile, he found a place for his best self to blossom. Three years later, he was a World Champion and a Gotham icon. In 1987, the recently departed Pete Hamill wrote that “New Yorkers don’t easily accept ballplayers. They almost always come from somewhere else, itinerants and mercenaries, and most of them are rejected. … Those who are accepted seem to have been part of New York forever. Hernandez is one of them.”

He was then and he is now. Has there ever been a more successful post-career second act in a Met life? One day, the Mets will retire No. 17 for him — and if they’re honest about it, they’ll retire it as much for his career in the booth and his simple existence as they will for the relevant lines in his Baseball Reference entry. Keith’s Mets career, while glorious, was a little too curtailed to merit a retired number in this fan’s opinion, but throw in everything he’s meant to the ballclub and its fanbase since then and he’s in a shoo-in.

In his role as a color guy on SNY, I confess that Hernandez can drive me batty. He’s often caught not paying attention, repeating something Gary Cohen or Ron Darling just said. And he can be disappointingly reactionary about anything new, whether it’s women in on-field roles (hopefully he’s grown out of that one), the shift, or a seemingly innocuous thing such as players carrying scouting reports in their pockets. Would a 15th-century Keith have hated the printing press? Do you have to even ask? It makes me crazy because it’s a tragedy for someone so ferociously smart to be habitually close-minded.

But there’s so much more to Hernandez than that. He’ll also break down a defensive play with a jeweler’s eye, or explain what a hitter should be looking for at the plate with stunning clarity. When he finds a defender’s positioning or a hitter’s approach lacking, you can hear the indignation in his voice, fueled by a certainty that he would have done it properly. You can hear Bob Gibson in there, and John Hernandez, and all the complications one senses Keith Hernandez has yet to untangle. And I never have the slightest doubt that he’s right. He would have done it better. Didn’t I see him demonstrate that hundreds of times? But there’s so much more to Hernandez than that. He’ll also break down a defensive play with a jeweler’s eye, or explain what a hitter should be looking for at the plate with stunning clarity. When he finds a defender’s positioning or a hitter’s approach lacking, you can hear the indignation in his voice, fueled by a certainty that he would have done it properly. You can hear Bob Gibson in there, and John Hernandez, and all the complications one senses Keith Hernandez has yet to untangle. And I never have the slightest doubt that he’s right. He would have done it better. Didn’t I see him demonstrate that hundreds of times?

At some point in any broadcast, I’ll grumble at Keith being snide, dismissive or indignant. But I’m also guaranteed a moment where he’s being enormously entertaining — it might be lamenting the need to put a tent on this particular circus, exasperation at how long this is taking, or some random tale from his endlessly interesting life. And I’ll almost always turn off the TV with a greater appreciation for some fine point of the game. He was smart and impatient and complicated and sometimes his own worst enemy then. He’s the same today. I wouldn’t have him any other way.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2019: Dom Smith

by Jason Fry on 13 August 2020 9:49 pm The Mets face challenges in this 60-game improv season: iffy defense, shredded starting pitching, an uncertain bullpen. An added challenge, for those of us watching from the socially distanced cheap seats, is how quickly it’s all going by.

I don’t buy the each game is equal to four and change thing, because it has nothing to do with how baseball is actually played. But it is more than a little startling to just be getting used to a roster and realize that a third of the season is complete. Baseball isn’t being played on fast-forward, but my baseball emotions feel like someone has that button mashed down. Each little tailspin feels like the team just got eliminated on some soggy matinee in September, and I have to remind myself it isn’t that way at all.

What helps with feelings like these? The same thing that helps with all baseball maladies — having your team win a game and look competent doing it. Funny how that cures all ills.

Thursday afternoon’s game was an entertaining one — some heart-in-the-throat moments, a scary storyline to follow, an unlikely hero, more good things from young players — that went in the win column. It didn’t exactly start well: David Peterson walked Trea Turner, was hurt by a throwing error by Tomas Nido that put the loathsome Adam Eaton on base, and then walked Starlin Castro. Bases loaded, nobody out, and up to the plate came Juan Soto, who may as well be called That Man Again in these parts.

Peterson got Soto to foul off a sinker, got a strike on a changeup, and then erased the most dangerous man in the Washington lineup — and maybe the N.L. East — on a nifty slider. The next hitter, the annoyingly capable Howie Kendrick, grounded out but brought Turner home. Up came Asdrubal Cabrera, who smashed a ball on a line up the left-field gap. Jeff McNeil got there, reached above his head, plowed into the fence, and held up the ball.

It was a great play — shades of Mike Baxter damaging his career to preserve Johan Santana‘s no-hitter — with McNeil so prioritizing hanging onto the ball that while he lay on the warning track I was a little worried he’d concussed himself so thoroughly that the ball would have to be pried out of his glove. (The diagnosis, after he was carted off the field, was a bone contusion, which isn’t great but is about the best medical update one can get in a sentence that also includes “carted off the field.”)

The Mets had avoided disaster — and as they did Wednesday night, they went to work on the Nats. Peterson settled in, ultimately allowing just one hit over five innings. Meanwhile, Dom Smith smashed a solo homer to tie the game, Nido hit a two-run shot to grab the lead, and then Nido sealed the game with a grand slam off Seth Romero, making his big-league debut wearing 96 and the slightly glassy-eyed look you’d expect to find on the face of a young man called into a big-league game after never pitching above the Sally League. Romero spent 2018 with the Hagerstown Suns, whose stadium I’ve been to several times. The difference between coming in for relief there and arriving at Citi Field (even without fans) must be comparable to the difference between singing along to a playlist in your car when no one’s watching and stepping onstage at the Apollo and peering out into the blinding lights.

Romero will have better days; Nido may not. That’s no insult — two homers and six runs batted in is hard to equal when your role is to play day games after night games. Even if he never reaches these heights again, Nido may prove useful in a way a big-league team could use: He’s looked better this year, perhaps aware that most every backup catcher is regarded as a suspect by his ballclub, perhaps annoyed that no one seems to remember he won a batting title in the minors, perhaps a little of both.

Nido’s defense is already good enough for any big-league team; if he can hit even a little, he can retire sometime in the 2030s as a wealthy man. On Thursday he hit a lot more than a little, and it was beautiful to see.

by Greg Prince on 13 August 2020 5:44 am In doing my nightly postgame statistical rounds, I noticed that the score by which the Mets beat the Washington Nationals on Wednesday, 11-6, had been gathering dust for quite some time. Until Wednesday, when the Mets exploded with practically unimaginable amounts of offense and it still seemed barely enough to fend off one particular precocious Nat, the Mets hadn’t won, 11-6, against anybody in slightly more than sixteen years, making it the 22nd-least recent winning score on the Met books. Now it’s the most recent.

Perhaps it appeared the Mets would require sixteen years or at least that many pitchers to get out of the top of the first inning at Citi Field when Robert Gsellman, starting for the first time since the Mets’ final home game three years ago, put two runners on and then discovered one more competitive innovation baseball has introduced since September 27, 2017: the advent of Juan Soto. True, he’d faced the kid in relief a few times, but this had to feel different. This was his whole night set out in front of him, a night Gsellman’d been craving in his starting pitcher heart all those nights he found himself reluctantly warming up in the middle innings. Sixty feet, six inches away was Soto, 21 and regularly evoking mentions of Mel Ott slugging — and not just because they both bear nifty crossword puzzle solutions as last names.

In case Gsellman forgot what it was like to be planted in the bullpen, Soto reminded him, as the home run he swatted flew well over it…and everything else at Citi Field. I’m sure the ball got a decent view of everything below its own stitches, though binoculars were probably required. When the 466-foot journey of Soto’s three-run welcome-back-Bob bomb completed its statistical rounds, the ball could be seen bouncing way in the back of the soft drink-sponsored pavilion far above right field. I think it knocked on the men’s room door to the left of the stand where they usually sell cola.

I’m sure Gsellman contemplated a quick trip to the facilities himself. The only thing that got him out of the first was Soto wasn’t due up again right away. And then, contrary to recent home team custom, he was presented with a lead by his friends in the Mets batting order. If they weren’t his friends already, they should be by now. The Mets’ batters, reputed for their courtesy in not disturbing Met runners in scoring position, learned the benefits of rudeness. Brandon Nimmo skipped the whole “runners on” thing when he led off with a homer against ancient Anibal Sanchez. Sanchez, 36, threw a no-hitter in 2006. It was so long ago that it had been only two years since the Mets had last won an 11-6 game; Soto was 7.

Nimmo, who’s too nice to come off as rude, nonetheless set a useful example for the batters who followed him to the plate, most of them turning impolite toward the opposing pitcher.

After Sanchez hit Michael Conforto, Pete Alonso hit Sanchez, doubling in Conforto. Dom Smith, listed as playing some alien position that has no business in National League baseball, doubled in Alonso. Wunderkind Andrés Giménez, who is somehow six weeks older than Juan Soto, singled in Smith. The Mets and Gsellman were out in front. Gsellman didn’t last but two innings as he reacclimated himself to his old role (“Man, I was so nervous,” he said afterward. “I felt like a little kid.”), but the Mets were generous to his myriad successors, adding a run in the third — which was countered by another Juan-ton act of slugging — and five in the sixth. Michael doubled with two on. Pete homered with Michael on. Dom homered immediately thereafter. The Mets hit with runners in scoring position and hit deep with bases clear of occupants. They collected thirteen hits and put them to excellent use to create eleven runs. Soto could produce only four on his own, with his teammates chipping in just two.

That’s how we got to 11-6 in one game. Why it took sixteen years to get to 11-6 since the last 11-6 Mets win is one of those little mysteries that make doing one’s nightly statistical rounds such an enigmatic delight. Historically, 11-6 hasn’t been a wholly uncommon score for the Mets to win by. From 1962 through 2004, the Mets had beaten an opponent, 11-6, eleven times in regular-season play. Maybe not a “normal” baseball score, but not so crazy that you think you’d need a decade-and-a-half and then some to see it again. Hell, Game Two of the 1969 National League Championship Series, wound up 11-6 for the Mets over the Braves on a day Jerry Koosman didn’t quite have his best stuff, but Messrs. Agee, Garrett, Jones and Shamsky blessedly did. It was the second postseason game the Mets ever played and 11-6 already represented half their postseason wins.

I don’t know why some scores simply fall out of fashion, as if there are tastemakers who determine how much a team wins or loses by and whether the combination can be considered chic enough to gain a measure of mass-market popularity. When the Mets beat the Red Sox, 8-3, a couple of weeks ago, it was their first 8-3 regular-season win since the last day of the 2014 season. There’s nothing remotely Unicorn-ish about an 8-3 score — the Mets had won a regular-season game by an 8-3 score 46 times over the first 53 seasons of the franchise’s history, but then more than five years passed before another 8-3 regular-season win. The Mets did beat the Cubs, 8-3, on October 21, 2015, but that was the clinching game of the NLCS (just the pennant, that’s all), so it doesn’t quite count under this exacting statistical umbrella I’m brandishing. And even if it does, that means it still took more than four years, until July 28, 2020, to produce another 8-3 win. An 8-3 win is a lot closer to “normal” than 11-6, yet it was wholly elusive for quite a spell there.

I’d say, “go figure,” but you can’t. All you can do, if you’re so inclined, is record that it happened.

The previous game the Mets won, 11-6, took place on August 5, 2004. I remember it clearly specifically for having not seen it or heard it. I had business in Washington that Thursday afternoon and was on an Acela back to New York when I was able to tune in on my trusty tiny radio the staticky news of what the Mets had done in their matinee in Milwaukee. Victor Zambrano made his Met debut a victorious one (four earned runs in a five-and-a-third innings, but he left with a large lead); David Wright drove in six runs to raise his career RBI total to ten; and the city I was putting behind me probably couldn’t have cared less that the Mets were romping in Wisconsin. In August of 2004, the Washington Nationals were still the Montreal Expos.

That was the last game I missed altogether in 2004, a fact that sticks with me because when the next season began, I wasn’t just watching or listening for me, but for whoever was reading this blog. I wouldn’t miss another Mets game until August of 2006 and have rarely missed one since. Yet at no time until August of 2020 did an 11-6 Mets win enter the current-affairs segment of our ongoing conversation here. Now it has.

I’ll say it: go figure.

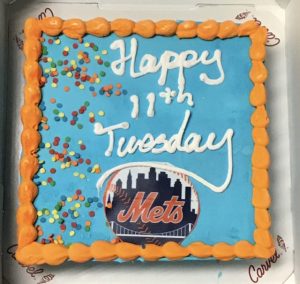

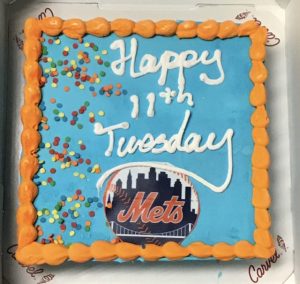

***In the realm of rituals related to keeping track, I’ve been part of a foursome that has attended the first mutually available and amenable Tuesday night game at Citi Field for ten years. This tradition dates back to August 10, 2010, when my wife Stephanie and I met up with Ryder Chasin and his father Rob to see the Mets take on the Rockies. It was our first game together if not our first time together at Citi Field. About a year earlier, the Chasins had gotten in touch with us and invited us to Ryder’s forthcoming Bar Mitzvah, November 14, 2009. Ryder, 12 going on 13, was a Mets Fan Who Liked to Read; his coming-of-age celebration would be at the Acela Club (now known as the Porsche Grill despite Acela rating two product placements in today’s column); and, well, would we like to join them?

Would we? It was too intriguing to pass up, and that was with only knowing Ryder and Rob from one letter apiece. Long, oft-told story short, Stephanie and I attended, we all stayed pals, and we consecrated our Metsian bond with a Tuesday night game the following August. Why Tuesday night? I don’t remember, but it became our thing. Ten Augusts, ten Tuesday nights, the four of us. Ryder, a couple of years the senior of Juan Soto and Andrés Giménez, graduated everything there was to graduate and is now a professional writer himself, 23 going on 24. Like that pitch Gsellman threw to Soto, time really flew.

Who’s gonna argue technicalities with a cake? It landed in August of 2020, when there’d be no going to Citi Field for any of us or anybody else. No going anywhere, for the most part. Our Tuesday night tradition could have been pardoned for pausing in deference to These Challenging Times, but Rob and Ryder thought better of it and did the best they could to make it eleven in a row. Thus, on Tuesday night, August 11, 2020, our friends the Chasins arranged to Zoom Stephanie and me shortly before 7:10 first pitch. Rob even had a specially decorated Carvel cake simultaneously delivered to our address to mark the continuation of our indefatigable occasion. As that element was intended as a surprise, I at first opted not to answer when a gentleman bearing frozen gifts rang, because, geez, I’m on a Zoom here, who the hell is suddenly bothering us? Good thing I was clued in so I could run to the door and accept the incredible gesture. Ice cream cakes in August don’t lend themselves to contact-free delivery.

Stephanie and I spent about two hours on our respective screens with Ryder and Rob, catching up about baseball and whatever else infiltrated our collective consciousness. (I resisted the temptation to blurt to Ryder, “My god, you’re like TOTALLY an adult now!”) Our eyes naturally darted to nearby televisions to keep up with the Mets and Nats, though the game wasn’t much more than an unobtrusive backdrop after a while. Still, it was the reason we’d virtually gathered, which led to a perplexing philosophical quandary.

Did this count?

Everything about baseball is about counting. It’s why we’re watching this short season that in so many ways feels like it shouldn’t be taking place in a pandemic. It counts. The games count. The scores count. Every run. Every run given up. We who can’t miss a game that counts unless we have to be on a train before the advent of apps adhere closely to counting what counts. The 11-6 win on August 12, 2020, counts like the 11-6 win from August 5, 2004 counts. The 11-6 win from October 5, 1969, counts, too, but like the 8-3 win from October 21, 2015, it counts differently. Counting what counts is what separates from the animals who don’t keep count.

I held up to the camera for Ryder’s and Rob’s edification the notebook in which I write down the result of each game I go to. I call it The Log II. The Log was filled with my Shea Stadium games. The Log II covers Citi Field. Every one of our August Tuesday night games are in there. The six wins. The four losses. The starting pitchers. The opponents. It’s all inked in. Despite the spirit of the Zoom and the affection baked into the cake, could I, in all good counting consciousness, pick up my pen and write down the spare but essential details of our eleventh consecutive Tuesday night in August if it wasn’t exactly our eleventh consecutive Tuesday night in August at Citi Field? I don’t count in The Log II games I don’t physically attend.

But The Log II doesn’t track everything about the games I go to. It certainly hasn’t recorded the heart of those ten August Tuesday nights with the Chasins.

Not written down in my spiral-bound steno pad is that we greeted each other heartily outside Citi Field ten times.

That we embraced as people who were close to one another did until 2020.

That we grumbled our way through security; me, mostly.

That once safely within the circular walls of the Jackie Robinson Rotunda, Ryder and I immediately wandered deep into “what’s wrong with the Mets?” (or a couple of times the inverse) territory while Stephanie and Rob presumably talked about other, less pressing matters.

That we decided what we were gonna get to eat and, if it differed, where we were gonna meet so we could eat it together and talk some more between bites.

That one time Rob amazingly managed to get us on the field for batting practice and Ryder snagged autographs from Jordany Valdespin and Justin Turner.

That another time we wound up sitting behind some thin blonde woman who never once looked up at the game because she was too busy tweeting literal Fox News talking points at all who dared argue with the positions she steadily tapped out, spectacularly oblivious to the big league baseball unfolding not too many rows in front of her. Shocked that somebody could care that little for the Mets or their foes, I squinted over her shoulder at her phone and deduced the disinterested filler of this perfectly good ballpark seat was Fox News talking head Kayleigh McEnany. I had never heard of Fox News talking head Kayleigh McEnany until then, but I looked her up when I got home and learned she was dating or maybe already engaged to Met reliever Sean Gilmartin, which I guess explained why she was there. They later married despite her apparent lack of emotional investment in his profession (I understand she holds a government job these days).

That last year Rob furnished a tenth-anniversary scoreboard message for the Mets to include among their various midgame Happy Birthday greetings.

That I’d keep score for a stray half-inning if Ryder was racing to and racing back from the concessions.

That Rob, Ryder, Stephanie and I would conduct a version of musical chairs a couple of times per game so everybody could talk some to everybody else.

That even when the score fell in the Mets’ favor, we were a little sad the game was over because we did this only once a year and now it was done, but we were inevitably cheered that we knew we’d be back out here same time next year, more or less.

Much less, it turned out this year, but the Zoom was the next best thing. As we wound down our video meeting, we discussed whether it counted, if it could in fact enter The Log II. The provisional decision reached was maybe in pencil. It’s not ink, but it’s not nothing.

That was Tuesday. I haven’t written it down yet. I don’t know if I will. Really, I don’t think I have to. We know we kept our thing going. Eleven in a row, just like it says on the cake.

Next year? Twelve in Flushing. I won’t count on it, but I will hope.

by Jason Fry on 12 August 2020 10:30 am Perhaps I should put a SPOILER WARNING on this one, but I received a special media preview of the Mets’ 2020 highlights video, and it’s 23 minutes of Jeff McNeil screaming “FUCK!” after making an out and five minutes of Andres Gimenez smoothly fielding hard grounders.

And you know what? I’m strangely OK with it.

The Mets lost Tuesday night, 2-1, with Max Scherzer outdueling Rick Porcello. The Mets turned in some nifty defensive plays, with Gimenez and possible Wednesday starter Luis Guillorme front and center in the infield, but (shockingly) couldn’t find the big hit in the clutch they desperately needed, and so it goes.

Maybe this is just me bargaining, but I’m in a better place than I would have guessed.

Part of that is having baseball back at all, something I figured wouldn’t happen, and that you could argue shouldn’t happen given the current problems with the Cardinals, not to mention the Marlins having to essentially come up with an entire B-team to keep going. The Mets have been hale if not hearty so far, and even though the results haven’t been there, their presence has made summer feel a bit more normal.

Tonight we sat in a backyard and drank with old friends (socially distanced of course), during which the Nats jumped out to a 1-0 lead and a 2-0 lead. We returned to our rented beach house and saw the Mets draw within 2-1, then turned up the TV so the Mets could be our company during dinner on the deck. Everything was pleasant except the score — this was one of those games that didn’t feel anywhere near as close as it was — and I was happier to have the Mets present but on the short side of the outcome than I would have been to have a night with no baseball at all.

There’s Gimenez, of course, whose fluid fielding and superlative baseball instincts are a reminder of baseball’s balletic perfection. There’s the steady parade of new Mets — the Mets were pummeled mercilessly Monday night, but I still smiled to see Ali Sanchez escape becoming the 10th Mets ghost. Sanchez had the greatest night of his baseball career despite seeing one pitch which became a double play, which makes sense when you consider the alternative. Similarly, it was fun watching Guillorme retire three straight Nats with 63 MPH non-gas, going so far as to ask for the ball from the first batter retired.

Even Marcus Stroman is a part of my unexpected equanimity, somehow. I don’t blame Stroman for opting out — I don’t presume to know anything about what’s going on in someone’s family — any more than I blame him for possibly manipulating his way to free agency through service time, given how routinely baseball teams manipulate service time for their own advantage.

When Stroman arrived last summer, I was happy to see him while dreading what his arrival might mean — I assumed the Mets had imported him as precursor for trading Noah Syndergaard or Zack Wheeler. They kept both Syndergaard and Wheeler for the season, but then let Wheeler become a free agent in the offseason, with nary a hint of interest or a peep of protest, making my prediction ultimately accurate if not timely.

In late July of 2019 the Mets’ rotation was Jacob deGrom, Syndergaard, Wheeler, Steven Matz and Stroman. A little over a year later, it’s been reduced to deGrom and Matz, and the latter has been giving up home runs with frightening frequency. When Stroman opted out, I could all but hear the Mets’ playoff window slamming shut — yes, they have a corps of young and effective hitters, but if Matz has lost his way, where do the arms come from? But rather than blame Stroman for a decision I couldn’t be privy to, I blamed the Mets for letting a potentially great rotation become hollowed out and vulnerable to injury and mischance.

It doesn’t make me happy to contemplate such things. But the ebb and flow of team fortunes are nothing new. And in this weirdo improv season, I’d rather obsess about that ebb and flow than stare at a year of nothing.

Once again, is that bargaining? Maybe it is. But we’re all bargaining this year, constantly reassessing what scares us and how much and what plans we should and shouldn’t make. Baseball has been my faithful companion in years both fruitful and barren; I’m glad to have it again for a year where uncertainty colors each and every day.

by Greg Prince on 11 August 2020 3:38 pm Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

On the telephone, Andy Pafko said that it would be nice to get together, but that he didn’t belong in a book about the team. “I wasn’t in Brooklyn long enough,” he said. “I don’t rate being with Snider and Furillo. I wasn’t in that class.”

—Roger Kahn, “The Sandwich Man,” The Boys of Summer

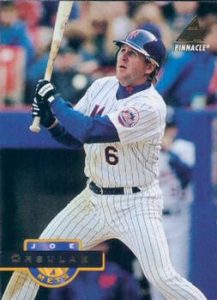

If I didn’t know what Joe Orsulak was doing here, I wouldn’t know what Joe Orsulak is doing here. Every other Met whom we’ve spotlighted as A Met For All Seasons to date makes a certain kind of contextual sense. Either they were around for a very long time or an ostentatiously short time; they achieved great feats or were known for slighter but indelible achievements; they’re somebody who inevitably gets talked about if the conversation is headed in the direction of an era with which they are instinctively identified; there is a story around them begging to be told; there is a statistic attached to their career that deserves enhanced awareness; there is something relentlessly Metsian about them.

I don’t believe any of the above apply to Joe Orsulak, yet I chose him as A Met for All Seasons. And of all seasons, I chose him for 1993, inarguably among the worst of all Met seasons. Mind you, I don’t associate Joe Orsulak with “the worst”. Honestly, although I’ve tended to very closely match players with seasons throughout this series, I don’t really associate Joe Orsulak all that much with 1993. I associate 1993 with Met misery. I don’t hold Joe Orsulak the least bit responsible for any of it.

Trust me, though, this isn’t some kind of thought exercise, or an effort to be contrary to the spirit of whatever it is we’re doing here, or ironic about picking a player who doesn’t quite fit the ur-Met mold in some category or another. I suppose I could have made a case for Joe Orsulak as the avatar of ordinary players who’ve played for the Mets after playing for a couple of other teams and before playing for a couple of other teams besides, the way I think of Harold Baines as a Hall of Fame player bearing the standard for all players who weren’t judged quite good enough to make the Hall of Fame yet maybe we oughta have one from their ranks in the Hall. I like that angle for Joe Orsulak now that I’ve thought about it (“The Master of the Middling”; “The Sultan of So-So”; “The King of Basically Just OK”), but I’d be retrofitting it inauthentically.

No, Joe Orsulak is my choice to profile here because at any point over the past quarter-century, if you were to ask me to name my all-time favorite Mets and you gave me the leeway to work my way down into a second tier, I would absolutely name Joe Orsulak ahead of many other bigger-deal Mets. And, indeed, nestled within that fistful of Mets I’ve really, really liked, just beneath the handful of Mets I’ve really, really loved, Joe Orsulak is right there. He is one of my favorite Mets ever.

When a fan loves a player yet has little idea why. Which leads me to wondering about something else: why did I decide, somewhere toward the end of his perfectly representative but objectively unremarkable three-year tenure in our midst, that Joe Orsulak is one of my favorite Mets ever?

Honest to god, I really don’t know. But just as honestly, he really is.

***In the 2001-02 Judd Apatow sitcom Undeclared, essentially the college-set sequel to his previous series Freaks and Geeks (both shows lived utterly brilliant if unfathomably brief prime-time lives), Seth Rogen as dorm denizen Ron Garner bonds with his Australian roommate by, among other things, discussing favorite movies. To maintain a properly badass facade, Ron reveals, “I tell people it’s Red Dawn. But in actuality, my favorite movie is You’ve Got Mail.”

I can’t determine whether Orsulak is my Red Dawn or my You’ve Got Mail in this allegory, but I think of the scene when I think of Joe. It’s not like I’m hiding my sentiment on his behalf, but I also have the feeling it says something about me that I must want to be known, or otherwise I wouldn’t put him out there as one of my favorite Mets.

Who, me? Why I’m a Seaver man! A Gooden man! An Orsulak man!

How’s that again?

Uh, never mind. I really like Keith Hernandez, too.

During Orsulak’s first year as a Met, I don’t think he made more than the most perfunctory of dents in my consciousness. I wasn’t at all excited to see him on Opening Day 1993, which, for our purposes today, raised the curtain on the Joe Orsulak Era. For the Mets’ purposes, Opening Day 1993 was supposed to bring down the curtain on two astonishingly embarrassing years. In 1991, our veritable Empire of the Eighties — finishing first or a reasonably strong second for seven consecutive seasons — crumbled suddenly and thoroughly, as the Mets without Darryl Strawberry proved lightweights in a division where everybody but the Expos was better than them (and the Expos had to play their last few weeks on the road when Olympic Stadium’s infrastructure collapsed nearly as badly as the Mets’). In 1992, remade to contend for a title with the additions of Eddie Murray, Bret Saberhagen and Bobby Bonilla, the Mets somehow got even worse, not to mention exponentially less pleasant.

Ah, but this was a new year. Opening Day is always a new year. In 1993, you could forget the plunge from 91-71 to 77-84 to 72-90. You could forget Jeff Torborg turned from the American League Manager of the Year you couldn’t believe the Mets snagged out of Chicago to the hapless steward of the S.S. Disaster in New York. You could forget how Bonilla had been no Strawberry, how Saberhagen was no workhorse, how the Vince Coleman-catalyzed chemistry was all wrong. This was a bright, brisk day at Shea Stadium. Everybody was getting a mulligan.

And we were getting Joe Orsulak starting in center field instead of Ryan Thompson, because Thompson was nursing a sore hamstring, which amid all the promise and pageantry of Opening Day (the first I’d ever attended and the first anywhere ever involving the Colorado Rockies) disappointed me. Thompson had been obtained the previous August with Jeff Kent for David Cone. If that trade was going to work out in the slightest, it would take Thompson living up to all the five-tool hype he toted with him from Toronto. C’mon, let’s see Ryan Thompson do his thing. Instead of the biggish-deal prospect potentially putting on a show, we got Joe Orsulak.

Yup, that’s what we got ever since bringing him aboard to little notice late in 1992. As the Times reported this earth-stilling event in December, “The Mets yesterday effectively completed their 1993 roster with the signing of Joe Orsulak, a versatile, free-agent outfielder who came cheap and who could wind up playing a lot.”

The Mets’ advertising slogan entering 1992 was “Hardball is Back.” Now it was “Orsulak is here and it didn’t cost much”? As for Joe, he expressed his excitement succinctly: “We didn’t have any other serious offers. No one came up with serious dollars.” Al Harazin extended the sense of suppressed jubilation when he added, “We’ve added interesting people. They may not be headline people. But they help you win.”

Yippee?

Perhaps I should have learned my lesson from headline people not helping us win in 1992 (the book The Worst Team Money Could Buy had already been excerpted and was being released right after Opening Day), but I found it hard to get particularly excited that the Mets had Joe Orsulak batting behind Murray, Bonilla and Howard Johnson versus the Rockies. Nevertheless, Joe did register a base hit and, after shifting to right once Dave Gallagher came in for defense, he did catch the final out of Dwight Gooden’s Opening Day shutout of expansion Colorado. A “9” on the scorecard in a fairly stealthy debut for the latest to wear No. 6. I’d just seen Doc! I’d just seen an franchise born! I’d just seen a season start! As I left Shea Stadium, I didn’t find myself thinking or saying, “That was great, except for the presence of Joe Orsulak.”

***I went to sixteen games in 1993, the most I’d ever been to in a single year to that point. After none of them did I leave Shea Stadium and find myself thinking or saying, “That was terrible, except for the presence of Joe Orsulak.” The Mets were, in fact, terrible across the frozen tundra of 1993. Whatever was spent on “interesting players,” on top of whatever was owed to the “headline people,” did not produce a champion, except in the ranks of even worse teams money could buy. Everybody you thought you were paying to see imploded. Everybody to whom you paid attention made you regret your focus. From 91-71 to 77-84 to 72-90, now to 59-103…and they had to win their final six to make it even that respectable.

None of it was the fault of the versatile, free-agent outfielder who came cheap and, in fact, wound up playing a lot. Maybe anybody who plays a lot in a season that inarguably stands (or cringes) among the worst of any Met campaigns shouldn’t be considered blameless, but Joe Orsulak didn’t bother anybody. No firecrackers out a car window in a stadium parking lot filled with fans. No bleach pumped toward reporters doing their job in the clubhouse. No tours of the Bronx generously offered to one media member in particular. Joe was not the reason you covered your eyes that summer. In 134 games, Orsulak batted .284 while starting 95 times. Not that a person really put a lot of 1993’s sins on Ryan Thompson when Vince Coleman, Bret Saberhagen and Bobby Bonilla were leading the high jinks out in Flushing, but Thomspon and his tools didn’t exactly explode onto the scene, either (though perhaps that’s a less than ideal phrase to invoke when discussing the year of Coleman’s penchant for making things go boom).

Whatever glamour was attached to the image of the New York Mets entering 1993 had dissipated completely exiting 1993. House was cleaned and disinfected as best as could be arranged under the auspices of GM Joe McIlvaine and manager Dallas Green. Their predecessors Harazin and Torborg, much like the Mets’ dignity, didn’t survive 1993.

***Joe Orsulak survived. Joe had been in professional baseball since 1981, selected in the sixth round from New Jersey’s Parsippany Hills High School the prior June by Pittsburgh. It was the same draft in which the Mets took Darryl Strawberry first in the nation. Straw and Joe made it to the majors in the same year, 1983. Straw was the object of everybody’s attention and won the Rookie of the Year Award. Joe saw seven games of action in September and was back in the minors most of 1984. His official rookie season was 1985. He hit exactly .300 for the last-place Pirates and finished tied for a distant sixth with Roger McDowell in ROY voting; Vince Coleman won. Orsulak grabbed little of my attention until September when, with the Mets engaged in a death struggle with Coleman’s Cardinals for the NL East crown, he pretty much killed us.

The Pirates lost 104 games in 1985, yet went 8-10 against the Mets. Three times in September, they took games that to my biased 22-year-old mind belonged to the Mets. In each of those games, this Joe Orsulak whom I’d basically never heard of or at least never noticed from previous Mets-Bucs encounters delivered a key hit in a decisive inning. In the last of those games, the Friday night when much of Long Island was without electricity after Hurricane Gloria, Joe Orsulak produced four hits, drove in two runs and scored twice. The Mets blew a lead and lost, 8-7. The lights appeared out on them, too. They’d rally to win Saturday and Sunday to set up their last stand in St. Louis the next week, but we finished three games behind the Cardinals — same quantity as the three games we lost to the stupid Pirates and Joe Orsulak.

Then, except for the occasional late-night ruminating on how did we not win in ’85?, I pretty much forgot about Joe Orsulak. In 1988, he joined the Orioles, who proceeded to lose their first twenty-one games with him on the premises. But he survived the worst start in baseball history and hit .288. The next year the Orioles shocked the portion of the baseball world that wasn’t preoccupied shaking its head at the Mets’ having traded McDowell and Lenny Dykstra for Juan Samuel and very nearly won the AL East. Orsulak was a big part of that monumental turnaround, too, batting .285. Maybe he wasn’t a power hitter, but he could sure rip his share of base hits. He rarely struck out and he had a knack for gunning down runners from whichever corner of the outfield he was stationed. In 1991, he led the American League in assists from left field. In 1992, he landed in the AL Top Five for assists from right field.

This is mostly stuff I’m looking up now. I didn’t know any of this soaring into 1993 and wasn’t conscious of it limping toward 1994. I knew Joe Orsulak killed us in 1985 and then disappeared from my consciousness until the Mets acquired him. Then I knew he was perfectly all right and that it was perfectly fine he’d survived the worst Met year imaginable, give or take one that includes a mule named Mettle.

***“Fans, the Mets are going nowhere but up!”

That rosy forecast emanated from a letter Joe McIlvaine sent to season ticket holders in November of 1993 (somebody posted it to Facebook a while back). If the hardiest among us were tempted to desert our sunken ship, it was Joe Mac’s job to suggest our feint toward the life boats might be a little on the hasty side. “We will work to improve our Major League club for 1993 and beyond,” McIlvaine pledged, “and feel strongly that our farm system will have a mother lode of talent ready to harvest shortly.” The GM didn’t name names of those who weren’t already in the bigs, but he did spotlight the members of the Mets’ suddenly burgeoning youth movement whom we’d seen a bit in ’93. There was Jeff Kent, “who led National League second basemen in RBI’s”; there was “starting pitcher Bobby Jones”; and there were not one but two “promising outfielders in Jeromy Burnitz and Ryan Thompson”.

Thompson was still a selling point. Orsulak went without mention, but come Opening Day 1994, Joe was out there in right at Wrigley Field. He hadn’t started, but he did finish. Just as at Shea versus the Rockies, he caught the final out, this time tumbling to the ground as he fought off the winds of the Near North Side. He was in the lineup the next day, and the day after. Nobody was selling season tickets off the glove, arm, bat or amiably unkempt hair of Joe Orsulak, but the Mets were going nowhere but up, albeit without an exclamation point, and Joe was surely part and parcel of the rebound. Granted, it would have been close to impossible to have gone down after 1993, but this was a legitimate turnaround. Maybe not Oriolesque c. 1989, but close enough for my tastes.

The 59-103 Mets of 1993 had morphed into the 55-58 Mets of 1994. Orsulak played in 96 of the 113 games they got in before the strike lopped off the back end of the schedule. Joe’s average dipped to .260, but there were a couple of big hits in there. On May 17, he led off the sixth inning at Shea against the Marlins with a game-tying homer. In the ninth, with the Mets down by one, he stroked a single into right to drive in two and win the damn thing. No Gatorade buckets were emptied and no jerseys were torn, but Joe kept the Mets above .500 at a juncture of the season and maybe the Mets’ overall journey when it seemed imperative to win more than lose for a change.

Ryan Thompson socked eighteen homers, but batted .225 and struck out nearly a hundred times in fewer than a hundred games. Jeromy Burnitz inspired Dallas Green’s enmity and was earmarked for an offseason trade. Joe Orsulak finished fifth among National League right fielders in assists.

He survived some more.

***It took a while to get the Mets and baseball back on the field for 1995. The strike called for August 12 lasted into April. MLB tried to substitute replacement players for the ones with whom it couldn’t reach bargaining accord. In parlance as yet unfamiliar to us, Joe Orsulak had been statistically what would eventually be termed a “replacement level player” in 1993 and 1994. Yet once they cleared out the shall we say real replacement players and brought back the real Mets, Joe Orsulak proved relatively irreplaceable.

Still there. He was still here, at any rate, and that wasn’t the easiest thing for him for reasons that had little to do with his offensive production or defensive skill set. Just as actual Spring Training was getting underway that April, Jennifer Frey wrote in the Times about the extra burden Orsulak was operating under. His wife Adrianna had been diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor the previous summer, just before the strike. While the rest of us missed baseball, Joe was glad to have the extra time with Adrianna and their kids. Once in a while as the season approached, he would figure to have to miss a game now and then. Life could be bigger than baseball that way.

“Part of the reason we feel special about him is the way he is handling it,” Dallas Green told Frey. “He’s being typical Joe. He appreciates the thoughts, but I think he just wants to approach the work like he always has and contribute where he can.”

“She’s doing so well right now, she wanted me to come and play,” Orsulak said. “If things were different, health-wise, I wouldn’t be here.”

For maybe the first time since he’d joined the Mets, I really took notice of Joe Orsulak.

***Joe beat the Cardinals with an eleventh-inning single on the first weekend of the 1995 season to raise the Mets’ record to 2-2. It would never again be .500. By the time he beat the Marlins with a tenth-inning single on June 15, we were ten under and miles from either first place or the recently instituted Wild Card. The mid-June box score reflected the churn that the Mets had undergone since 1993 — it was dotted by names like Brett Butler, Chris Jones, Jose Vizcaino, Rico Brogna and Edgardo Alfonzo — but Orsulak was still a Met and the Mets were still seeking respectability. Knowing the grace with which Joe was handling the balance between baseball and family was plenty respectable, but it was one of those things that didn’t exactly show up in the box score or inform the standings. This era of his and everybody else’s in the Mets’ various uniforms (which kept changing yearly) may have had nowhere to go but up, but it was certainly taking its sweet time getting there.

Somewhere along the way, without warning, the time to rise was at hand. It was too late to do anything about a playoff race in 1995, but the Mets transitioned when almost nobody but we hardy souls who survived the competitive wreckage of 1993 and the labor strife of 1994 with our interest intact was looking. The Mets were 35-57 on August 5. The next day, the Mets won. They won six in a row. They had traded Bonilla to Baltimore and Saberhagen to Colorado. They would trade Butler, a quick fix in center, back to Los Angeles. The young Mets were finally taking hold. Young Mets who win are the best Mets who win when you’ve gone years without winning. These were indeed the young Mets of Kent and Thompson, of Alfonzo and Brogna, of Carl Everett and Butch Huskey, of Todd Hundley finally coming of age behind the plate, of that “mother lode” of pitching, featuring Bill Pulsipher and Jason Isringhausen. Damon Buford, who’d come over from the Orioles in the Bonilla trade, was seeing a lot of playing time. The main piece from that swap with Baltimore, Alex Ochoa, was going to be up soon as well.

Continuing to survive in the mix, unobtrusively serving as de facto clubhouse elder among the position players, was Joe Orsulak. Joe was 33 that summer. I was 32. As I was getting to know my online friend Jason, I recall telling him I was born “the same year as Joe Orsulak”. He was a touchstone now. I also remember something else about those nascent AOL “you’ve got mail” days, when it became habitual for me to go on a Mets message board the weeknight after the previous night’s game (it was the only time I had access to the one computer that was properly wired at work). I remember somebody on the board took a shot at Joe Orsulak. I don’t know what, if anything, Joe did to merit it or if it was just one of those inventories of the current roster a fan conducts to remedy what must be done to achieve a championship ASAP.

“Joe Orsulak,” this person wrote, “is deadwood.”

Damned if I know why, but I was moved to immediately respond, “JOE ORSULAK IS NOT DEADWOOD.”

I didn’t care that capitalizing was tantamount to shouting. I was angry in that way I get when somebody insults one of my favorite players. Except I don’t recall concluding at any point prior to that one that Joe Orsulak was one of my favorite players.

Yet there I was, defending him as if he was. So, yeah, I guess he was.

Maybe I was being a little ironic at first. “Orsulak” tripped off the tongue a bit like “Shlabotnik,” Charlie Brown’s perpetually futile Joe of choice, but though I probably lightly made the comparison to my AOL pals, Orsulak was no Shlabotnik, no schmendrick, no readily replaceable cog. From 1993 to 1995, only Jeff Kent played in more games and for the Mets than Joe Orsulak. Constancy wasn’t as exciting as youth but it wasn’t nothing. Keeping it together while your spouse is enduring an incurable disease surely wasn’t nothing. Grace under pressure, survival instincts, a .283 average with a few more outfield assists thrown in…blended with whatever makes a fan a fan and, gosh, maybe that’s how you arrive at an all-time favorite.

***The Mets’ August tide kept rising through September. They finished the year on a 34-18 roll. I couldn’t stay away from Closing Day, an event I hadn’t attended since 1988. I sat, by myself, as the Mets battled the Braves one scoreless inning after another. The Mets were doing the battling. The Braves were due in the postseason in a couple of days and were probably just fulfilling their obligations. However it happened, it was zero-zero in the eighth and Joe Orsulak led off against ex-Met and non-personal favorite Alejandro Peña. Earlier in the game when Joe batted, I overheard a guy sitting nearby tell his girlfriend, “this guy is no good.” I resisted the inclination to turn to him and shout, “JOE ORSULAK IS NOT DEADWOOD,” but kept it to myself.

Orsulak tripled. I thought about saying something. I think I just smiled.

The Mets stranded Orsulak on third and played past the ninth. Green double-switched Joe out of the game in the top of the eleventh. Tim Bogar walked with the bases loaded in the bottom of the eleventh to win it for us, 1-0. We finished the season 69-75, tied for second place. It was nowhere near first place except on paper, but we had just picked up a half-game on 1996, a season none of us who stood and cheered at the end of 1995 could wait another second let alone six months for.

***Joe Orsulak would not survive the wait. That sounds a bit on the morbid side, so let me rephrase that. Joe Orsulak left the Mets as a free agent after the 1995 season and signed with the Marlins. On May 8, 1996, he came back to Shea and instigated a come-from-behind rally to beat his old team, which had regressed without him. In 1997, the still-youthful Mets recaptured the spirit of ’95 and built on it, emerging at last as a contender for a playoff spot. Orsulak was in his final MLB season by then, playing for the Expos. As he’d been doing when he wasn’t helping us, he was still killing us. There was a game at the Big O in late May, just as the Mets were demanding to be taken seriously, in which Orsulak doubled off Mark Clark with the Mets ahead by a run in the fifth. Before the inning was over, Joe scored what proved to be the winning run for Montreal.

In 129 career at-bats as a Pirate, a Marlin and an Expo, Joe Orsulak recorded 35 base hits versus the New York Mets. I’m convinced at least 32 of them were lethal to our fortunes.

Orsulak wouldn’t play in the majors after 1997. He tried to make a team in the Spring of 1998, however. That team was the Mets. I was quietly ecstatic that he was coming home to me. It was just a matter of winning a bench role. How hard could that be for good ol’ Joe? We had a different manager and a different general manager from the end of Joe’s first tenure, but Steve Phillips and Bobby Valentine had to see what Joe’s lefty bat and dependable arm could bring to our team as it rose. In one exhibition game televised on Channel 9, Joe homered. Gary Thorne practically fainted from surprise. Joe Orsulak, he said, was only with the Mets this Spring as a favor to Cal Ripken, Jr.

HUH? I hadn’t read that anywhere before Thorne opened his mouth and I didn’t read it anywhere afterwards. It seemed rather uncouth to mention it if it were true. Joe’s wife was still battling cancer, he’d given the Mets three solid years, he’d given professional baseball close to twenty, and now you’re telling a television audience he’s not good enough to get a look except that somebody asked somebody else for a favor? And since when were in the Mets in the business of doing favors for Cal Ripken, Jr.?

Joe Orsulak hit .213 in Spring Training of 1998 and was released. The Mets were plagued by injuries a few weeks into their season and I hoped Phillips had saved Orsulak’s phone number (or could ask Ripken for it), but no dice. As far as I can recall, Joe Orsulak was never heard from again where the Mets were concerned. He was certainly never mentioned prominently in Queens or St. Lucie.

***A tad of Internet research on my part uncovered a “where are they now?” article in the Baltimore Sun from 2008 that found Joe Orsulak was living in Maryland and doing all right. He’d done some assistant high school baseball coaching as a favor to a friend — not Ripken — but had given it up after a few years. Adrianna had died in 2003, and by 2008, Joe was remarried and mostly taking care of his growing kids. “I’m not doing anything in baseball,” he said, “and frankly, I don’t miss it.”

Nevertheless, he looked happy to be back in his element at Camden Yards in 2019. The occasion was a reunion of those 1989 Orioles who almost won their division. It was a big enough part of Baltimore lore (and Baltimore hadn’t had much else to get amped up over lately) that the Orioles chose to commemorate their thirtieth anniversary the way I wish all teams would commemorate all their delightfully surprising squads who don’t necessarily go all the way. Joe’s amiably unkempt hair was mostly a memory, and he did not appear ready to take a few fly balls, but you could tell he was still Joe Orsulak. He told the Oriole pregame hosts about how much he loved throwing out runners — more than hitting home runs, he swore — and what it meant for the survivors of the 1988 last-place club to have come together and make their run in 1989; it bonded them forever, he said. In my mind, I substituted 1993 for 1988, last two months of 1995 for 1989, and Mets for Orioles

It was obvious that Orsulak, by dint of the bird on his polo shirt and his inclusion in this reunion, likely considers himself an old Oriole when he considers himself an old ballplayer. Yet that won’t stop me from considering him an old Met, or at least a veteran Met from when he and I were at an age that wasn’t quite indicative of a youth movement. And it won’t stop me from continuing to consider him one of my favorite Mets ever, whatever the reason I do.

I still really don’t know why. But he remains right there.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2019: Dom Smith

by Greg Prince on 11 August 2020 2:08 am Monday wasn’t a good day for Mets pitchers hailing from Long Island. Long Island’s own Marcus Stroman (LIOMS), heretofore rehabbing his torn calf and presumed to be returning to the Mets’ disturbingly depleted rotation soon, announced in the afternoon he was opting out of 2020 due to his family’s COVID-19 concerns. Come nightfall, Long Island’s own Steven Matz (LIOSM) opted out of competitive pitching versus the Washington Nationals, giving up eight earned runs in four-and-a-third innings, a harrowing echo of last week when he was strafed for five earned runs in three innings in D.C.

Maybe somebody should check on Frank Viola from East Meadow, Pete Harnisch from Commack, Hank Webb from Farmingdale, Ray Searage from Freeport, John Lannan from Long Beach, Paul Gibson from Southampton and John Pacella, who was born in Brooklyn but graduated from Connetquot High School in Bohemia (no word whether his mortarboard fell off as he accepted his diploma). Like Stroman, none will be pitching the rest of this season. Like Matz, all would be advised not to.

I can’t blame Stroman of Medford for taking a good, long look around Major League Baseball not to mention the country it’s played in and taking a pandemic pass. If he calculated the declaration of his decision for it to coincide with the accrual of enough service time for him to qualify for free agency, well, gosh, whoever heard of a baseball team manipulating a player’s calendar to gain a financial advantage? I liked Stroman fine when he pitched for the Mets, which was eleven starts last year and none at all since. I don’t know in retrospect that I loved giving two pitching prospects to the Blue Jays for what turned out to be a grand total of eleven starts, but that slight sum couldn’t have been foreseen entering 2020. Nothing much could have been foreseen entering 2020.

Matz of Stony Brook is a sympathetic figure, too. Always comes across as polite and sincere. His Tru32 foundation admirably supports first responders. He has a sandwich named after him at a deli in East Setauket and we all remember his grandpa going nuts at his smash debut. Once upon a time, Steven could hit as well as he could pitch. Now he doesn’t get to hit at all and his ERA should only be somebody’s slugging percentage. Based on his last two starts, it might be the Nats’ versus Matz.

The most dynamic pitcher the Mets offered up versus the defending world champs, albeit as a ninth-inning human sacrifice, was Luis Guillorme. He’s not from Long Island and he’s not a pitcher. Well, he is now. One bullpen-preserving frame hurled (because a ten-man relief corps apparently isn’t enormous enough to survive a blowout), one earned run average of 0.00. Andrés Giménez may have Luis’s path to playing time blocked in the infield, but no way Guillorme doesn’t rate the call over Paul Sewald the next night we’re en route to a 16-4 rout.

This, therefore, is what 2020 has come to. Seventeen games in, we’ve had a position player pitch, yet our National League franchise hasn’t had a pitcher hit.

Guillorme’s catcher was Ali Sanchez, who came in to relieve subdued birthday celebrant Wilson Ramos when the score was a million to nothing or whatever it was by then. Sanchez became the fifteenth new Met of the year, which is almost as many runs as the Washingtonians walloped. We doff our mask to Met No. 1,106 for coming into our world under the bleakest of circumstances and presumably coming back for more.

And, hey, since it wasn’t close anyway, why not a hat tip amid the offensive onslaught from the other side to modestly beloved alumnus Asdrubal Cabrera, who went 4-for-4 with two homers, two doubles and five runs batted in? Asdrubal was a Met longer than Marcus, not as long as Steven. For a spell he was one of my favorites, thus I can’t get utterly sore that he has apparently taken the ex-Met Met-killer baton from Adeiny Hechavarria, who took it from Daniel Murphy, who took it from Justin Turner. All of them in recent years have come back to Citi Field to rake against the Mets and each of them has socked balls into Long Island Sound. The splash was loud enough to wake the Stromans and the Matzes all the way out in Suffolk County.

by Greg Prince on 9 August 2020 9:50 pm This season, however it turns out, whether it turns out, will probably be remembered for other storylines, but churning beneath the surface of Mets Baseball 2020 is the churn itself. Have you noticed just how many players we’re going through a mere sixteen games in? When last season ended, the all-time Met count was up to 1,091. Barely two weeks into this one, we’re up to 1,105, or practically a new Met every day. So many Mets to have met, and we seem to have plumb forgotten to make formal introductions. Allow us, then, if you please, to stand on ceremony and present the new guys.

Outfielder Billy Hamilton is a Met. We’re his fifth club in three years, counting San Francisco, with whom he signed but never played.

Infielder Brian Dozier is a Met. We’re his fifth club in three years, counting San Diego, with whom he signed but never played, should you find yourself detecting a pattern

Reliever Hunter Strickland was a Met (fourth club in three years) and, for all we know, might be again. His ERA in three appearances ballooned to 11.57, which will make you an ex-anything awfully quick. Strickland is currently off the 40-man roster but at the Alternate Site in Brooklyn. That’s where relievers with 11.57 ERAs are sent to consider the error of the their ways.

Chasen Shreve is thus far a pretty good Met reliever, which we are conditioned to believe is a species no more actual the Loch Ness Monster, but lately has, in fact, existed and thrived in a land called The Bullpen.

Speaking of imposing pen presences, Dellin Betances is also a Met reliever, sometimes pretty good. Likewise Jared Hughes. He’s been uniformly very good.

Let’s remember that Ryan Cordell was here; he’s an outfielder currently joining Strickland in Coney Island exile.

Michael Wacha became an important enough component of the starting rotation that he’ll be missed now that he’s on the injured list, though that’s as much because for all the Mets we’ve had, we don’t seem to have a genuine sixth starter (that was gonna be Wacha) as it is that Wacha has been wowing batters. Getting many of them out while dealing with shoulder inflammation is plenty admirable in 2020.

Franklyn Kilome got twelve batters out in his one outing, yet was optioned to Elba, but that transaction was primarily a function of churn. Go four innings as a reliever one night and you can’t be used for a couple of days, so go ice your arm by the beach, kid. Kilome might be back by Wednesday in time to take what had been Wacha’s turn, which comes after that of Rick Porcello.

Rick Porcello is not only a Met, but he grew up a Mets fan in New Frazier, also known as New Jersey. Mets fan Rick Porcello had to like what he saw from Mets starter Rick Porcello in his last start, whereas Mets fan Rick Porcello might have been on the phone to the FAN to complain about Mets pitcher Rick Porcello after his first two starts. Surely Porcello the pitcher would understand.

Jake Marisnick and Eduardo Nuñez have been on the injured list for a spell now, even though the season hasn’t been going on all that long. Time is mostly untrackable in 2020. The season is sixteen games old yet more than a quarter over, and we’re supposed to keep track of Jake Marisnick and Eduardo Nuñez? Next thing you’re going to want to know is whatever happened to Jed Lowrie.

Jed Lowrie’s on the IL. But you either already knew that or didn’t really want to.

Yes, lots of coming and going beyond the most noisy of noiseless disappearances. Ali Sanchez has been called up twice and hasn’t played at all. Daniel Zamora was called up; was witnessed warming at least once; and was sent down. Tyler Bashlor had a similar story, except he was sent away, to Pittsburgh. Nobody’s much mentioned the status of Corey Oswalt since he imploded, but then again, nobody’s really asked. You may have missed the end of the Jacob Rhame era; like Ed Wynn as Lou Bookman, he was last heard to be making a pitch for the Angels. It’s all something of a blur.

Yet a pair of debuts have truly stood out here in bumper-to-bumper 2020, like a news chopper hovering above rush hour traffic. One is that of former No. 1 draft choice and current No. 4 starter David Peterson. As if his first-round credentials and three promising starts to date somehow don’t impress, Peterson, upon his July 28 debut, became the 1,100th Met ever, or the eleventh Milestone Met. How impressive is that? It must be very impressive, or there’d be more than eleven.

In honor of Peterson being the eleventh Milestone Met, let’s take a moment and re-meet the previous ten.

100. Jimmie Schaffer

The catcher from Pennsylvania pushed us into all-time triple-digits on July 28, 1965, in the midst of Ron Hunt’s reign as the Mets’ first star, or precisely 55 years before Peterson arrived at Fenway Park. Schaffer played in only 24 games as a Met, but surely made a mark in baseball history as minor league mentor to future Hall of Famer (and Met No. 455) Eddie Murray. You know how Murray is considered one of the greatest switch-hitters ever? It was Schaffer who helped convert him to hitting from both sides. That was at Double-A in 1976. The two of them have remained close.

200. Bill Sudakis

Sudakis, previously a Dodger, gave us eighteen games after joining our ranks on July 11, 1972, five of them as a catcher the year Jerry Grote missed close to a hundred.

300. Phil Mankowski

Mankowski, whose Met debut came April 11, 1980, honestly didn’t play a very good third base (three errors in seven chances), but he was, at least on paper, the replacement for 1979 incumbent Richie Hebner, who couldn’t wait to get out of Flushing. Hebner was traded to Detroit for Mankowski and Jerry Morales. For helping to show Richie the Shea exit he so visibly craved, Mankowski received a forty-year grace period. I’m officially renewing it.

400. Randy Milligan