The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 28 January 2020 3:17 am Outside it’s cold, misty, and it’s raining. We’ve got a FanFest; who right here’s complaining? Not anybody who thinks it’s sexy that the Mets opened Citi Field on the last Saturday in January for as much baseball as they could possibly produce without benefit of a baseball game.

It was the first hopefully annual FanFest in Mets history. Mets history goes back a ways, yet they never before did this. They ran modest caravans and arranged diffuse appearances, half-heartedly and intermittently currying winter goodwill if it wasn’t too much trouble. A full-fledged FanFest, however, was some other sucker’s parade. Cubs Convention. Cardinals Winter Warm-Up. Red Sox Weekend. And whoever heard of those teams? The Mets were content to maintain a low hot stove profile. It’s not like folks wouldn’t turn out on Opening Day.

For much of the 2010s, if you wanted a Mets FanFest, you did it yourself. Queens Baseball Convention, or QBC, was as DIY as it got. We, the fans, did that, though I use “we” broadly. In recent years, these original LGM Meetings were largely the work of two dedicated Mets fans, Keith Blacknick and Dan Twohig, with dozens of volunteers and contributors (I was among the latter) pitching in to put on a show, and hundreds of Mets fans investing in tickets just so we could all be in one place for a few hours between seasons. It was a great time wherever it was held, which was usually in a spot where the seams all but burst out into the frigid streets. QBC was an Off Broadway production, but it had heart.

Thing is, QBC, its miles and miles of heart notwithstanding, shouldn’t have had to have existed. Fans shouldn’t have to put on their own FanFest. Fans want to rally around the flag, even when the flag never got higher than fourth place the previous year and wasn’t projected to fly much higher the next year. We want to revel in our thing. The Mets have been our thing collectively since 1962. We don’t go on hiatus after Game 162. We embrace the Mets 365 days most years, 366 days this year. But ya got meet us halfway one day. We’ll come to you, but ya gotta open the door and let us in. Do that, and the reveling and embracing will flow.

And so it did on Saturday. The first hopefully annual Mets FanFest clicked. At least I think it did. I was there, but I was officially in media mode, kindly credentialed by the club’s communications department, which meant tamping down my natural inclination toward the first-person plural and foregoing the myriad selfie lines that gripped and grinned with most every Met in creation.

That was fine. I didn’t have to queue up and pose with Michael Wacha. It did my heart good that so many others were able to.

The vibe, at least as observed from the distance of a dangling press credential, was warm, sunny and excited inside Citi Field. Some of it, I believe, was the simple thrill that this was actually happening, like when we got our no-hitter. We’d spent our lives imagining what it would be like and couldn’t imagine it as having happened.

FanFest? It has happened.

***

My first stop, at 10 AM, was a room I’d never seen on the third base side of the suite level. I haven’t seen all that much of the suite level, so no surprise that it contains nooks and crannies that have gone underexplored since 2009. They sent the media up there. All the familiar nooks and crannies were otherwise occupied for FanFest.

Our first player availability was with Jacob deGrom. They got him started a few ticks early, meaning by the time I took my place on the fringes of the scrum of microphones and cameras, my main takeaway from whatever he said was that in January in New York, Jake wears a knit hat. Good thinking. We don’t need Jake catching a chill.

Jake was ushered away and Pete Alonso was ushered in. Up close, I can report with confidence that he’s Pete Alonso. I mean totally Pete Alonso. He seemed thrilled to be Pete Alonso in something close to his natural habitat. The questions he fielded had mostly to do with Luis Rojas and Carlos Beltran. Luis as manager was thrilling to him, albeit in a mellow vein. “Dude never loses his cool,” Pete said. “I’m so pumped. I’m so pumped for him.” Good, I thought, let Pete handle the pumping. Let the skipper be the mellow one if that works. I heard variations throughout the day on how super it was that Rojas is low-key. It’s a good reminder that these guys, the Mets, have a long grind ahead of them and don’t believe they need a lot of unnecessary chatter harshing their buzz. They’ve got the clusters of microphones and cameras for that.

Pete is pumped. Carlos Beltran was a ghost at these proceedings (as opposed to Mickey Callaway, who seemed to have simply vanished from contemporary dialogue). “The stuff that happened with Carlos was unfortunate,” Pete said somewhat somberly, but mostly he wanted us to know Luis is gonna be awesome and that “I’m so damn excited” to get going, improve and win.

All active ballplayers, I’m convinced, are variations on Don Draper. Their business may exploit our predilection for nostalgia, but all they want to do is look ahead and move forward. Shame about Beltran, but he’s not here. Rojas is. Spring Training almost is. We should all be pumped.

(There I go, slipping into first-person plural.)

Our next Met was Amed Rosario, accompanied by Alan Suriel, familiar to anybody who stays tuned for the postgame shows on SNY. Suriel translates questions and answers between the English-language reporters and the Spanish-language players. I’m continually amazed at how well this works, at least for topline communication regarding what went right or wrong out there tonight. All I really gleaned from Rosario’s session was that Amed, too, thought what happened with Beltran was “an unfortunate situation,” and that Spanish as a language is as fast as Amed as a baserunner.

***

There was a bit of a gap between Rosario and the next scheduled availability, so I visited the Foxwoods Club, home of the main stage for the duration. The season-ticket holder session was in progress, featuring Brodie Van Wagenen and Luis Rojas, as moderated by the eternally classy Gary Cohen. Luis indeed seemed relaxed. The day before, after his introduction, Steve Gelbs did a standup with the new manager, and something about the interplay — just the “Hi, Steve” of it — put me in mind of Jerry Ford shortly after assuming the presidency from Richard Nixon, specifically the photographs of Ford toasting his own English muffin. Our long national nightmare was over. We had a regular guy in office.

Brodie said something about Jeurys Familia having lost 30 pounds, presumably most of it ERA.

The manager and the general manager gave way to the award-winning duo of deGrom and Alonso. The season ticket-holders applauded Pete and Jake, Pete more than Jake at first, if only for the novelty, I hunched. We’ve had Jake for six years. In this atmosphere, deGrom was briefly Rod Tidwell at the NFL draft, “five years late for the prom.” The moment belongs to Pete Alonso.

But the age belongs to Jacob deGrom, and Mets fans appreciate him just as much after his second Cy Young. Jake got his applause, too. It might have been for clearing his throat. Everything is an applause line when you’ve got the best pitcher and the best slugger in your midst. Pete, clearly paying attention this past year, announced, “There’s no casual Mets fan.”

More applause.

***

Steven Matz was our next media availability. We learned that he knows Rojas well; that he considers Luis “even-keeled”; that after one interaction, “I’ve already learned a lot” from pitching coach Jeremy Hefner; that “I’ve never put much thought into” whether opposing dugouts are stealing his signs. It was all spoken like a true Mets veteran. Calmly holding a cup of coffee while everybody wanted to know about the chaos that had been floating around the Mets, Steven could have been Dave Foley on Newsradio.

***

At 11:42 AM, we gentlemen and ladies of the press were shepherded into yet another room I’d never seen, somewhere down the first base line on the Plaza level. It’s painted mostly blue with streaks of orange. There’s an outline of New York State on one wall with “Mets” scrawled from Albany to Buffalo, à la the Erie Canal song we learned in fifth grade. Something silly is about to happen, a photo op involving a mostly packed truck full of baseball gear. It’s the truck that will soon be rolling south to St. Lucie. They’ve saved a few bags of equipment so they can be loaded on by two mascots, three players and one alumnus.

I told you it was silly. But if I weren’t there in a semi-professional capacity, I’d be consuming it on my phone or tablet later, probably thinking it was incredibly cool. As we waited on our celebrity baggage-handlers, I listened in on a debate as to whether Luis Rojas is the 22nd or 23rd manager the Mets have ever had. It’s not the first of these I’d overheard. The Mets specified Beltran as the 22nd in November and have stuck to that script, calling Rojas the 23rd. Yet as someone said earlier in the Foxwoods Club, Wally Backman was named Diamondbacks manager one offseason, but never actually managed a game and isn’t listed among Arizona’s skippers.

Beltran, I decided, is our John Hanson. John Hanson’s title was “President of the United States in Congress Assembled” in 1781 and 1782, the Articles of Confederation days. I used to work with a guy who loved to invoke John Hanson, not to any grand philosophical end on how government should be organized, just to let it be known he knew we had a president who wasn’t really a president, but he was kind of the president before we had a president.

Sort of like Beltran.

Down in Washington, DC, this Saturday morning, impeachment proceedings were continuing. Now and then I’d scroll Twitter for an update. These are serious times for our democratic republic, and I’m standing here waiting on two figures with enormous baseballs for heads to finish packing a truck. What a country.

Ah, finally, here come Mr. Met and Mrs. Met. And here come the contingent of Mets with more naturally proportioned noggins: Robinson Cano, Jeff McNeil, Edwin Diaz and, from the past, Turk Wendell. Maybe it’s my imagination, but Diaz and Wendell seem to have an organic simpatico, reliever to reliever. For the occasion, though, everybody’s an assembly line worker, passing those bags up a ramp and onto a truck. I told you it was silly, but the cameras go crazy. These images will whet whistles all over the Metropolitan Area and perhaps throughout the state illustrated on the wall. A small crowd connected with the truck’s sponsor gathers and cheers.

I write down the license plate number of the truck in case the gloves and bats therein meet with foul play.

Once the hubbub simmers down, we get our next wave of availabilities, though it’s still kind of loud, so mostly what I divine from listening to Diaz/Suriel is he’s working on his mechanics. Edwin will be fixed. Jeurys will lose weight. The sun will come out by March 26. I’m sold.

Also, McNeil’s wrist is fine; Cano played for Luis’s father Felipe Alou on the Dominican WBC team; and “the fans mean everything to us,” according to Robbie. I could swear he means it.

***

In the Rotunda a few minutes later, I am introduced to Art Shamsky. This is the fourth time I’ve been introduced to Art Shamsky over the past eight years. I consider Art Shamsky my personal alumnus. We should all have one. Art doesn’t remember me from 2012, 2014 or 2017. To be fair, Art meets a lot of media and fans, and I’m one or the other as Saturday morning has morphed into Saturday afternoon.

First, I’m media and ask him about the last year, which he perhaps more than any Miracle Met devoted to proudly carrying the 1969 banner. There were a bunch of those champion Mets among us in 2019, but rare was the instant when Art wasn’t among them. Makes sense. He’s local, he’s written two books about it and, as Sports Illustrated’s Michael Bamberger put it on the occasion of their fortieth anniversary, Shamsky’s “the unofficial class secretary of the ’69 Mets”.

As such, Art dutifully reads me the minutes of the last meeting, with the caveat that he “can’t put into words” what it all meant, in light of everybody getting on in years and too many of his teammates missing. The reunion in June and all the attendant fuss “brought back a lot of memories” for “a great year”. There were young fans, their parents and their grandparents testifying to how much 1969 meant to them, and that imbued the seasonlong celebration with even greater currency.

I guess I knew that, so I asked him something specific. At the reunion in June, Art accompanied Buddy Harrelson when the carts brought the Miracle Mets onto the field. Given Buddy’s difficulties from Alzheimer’s, I told him I thought that was the most touching moment from an afternoon loaded with them. Shamsky said he didn’t know they’d be riding in together, but once they were on board, he mostly wanted to make sure his teammate didn’t fall.

I was back to being a fan.

“It was a special team,” Art said, and after fifty-plus years, I wasn’t about to question his assertion. I also wasn’t about to turn down his request that I tell our readers to go to artshamsky.com to find out more about his most recent book, After the Miracle (the climax, wherein Shamsky, Harrelson, Ron Swoboda and Jerry Koosman visit Tom Seaver in California, is a love story unto itself), and maybe follow @ArtShamsky on Twitter.

One question to me from Art: Is this really the first FanFest the Mets have held? Yup, I confirmed. “That’s hard to believe,” he said. I agreed, and wished him and his 1969 teammates a happy fifty-first anniversary.

***

I had been told that if I hit the Delta Club at one o’clock, I could catch up with Turk Wendell, who escaped the microphones and cameras in the New York State room once he played his role in loading the truck. The Delta Club was where much of the action was, with games and pictures and general commotion of the delighted variety. Sure enough, I found No. 99 greeting fans and joining them for a few rounds of cornhole, a game tailored for a man expert at slamming rosin bags to the ground. My only agenda in meeting Turk was asking about Diaz. I didn’t know if they’d ever met before gathering up the bags for the truck but I wondered if they had some sort of innate reliever bond.

“Never mind, Sugar, we can watch video of your release point.” Not so much, Turk said, but he watched Diaz struggle last season, “and I struggled with him.” Something about his release point was off, according to Turk. Or maybe it was what Edwin told Turk. It was pretty loud in the Delta Club, but he left me feeling modestly more optimistic about the closer for whom Jarred Kelenic was judged fair trade.

***

Back on the suite level, there is an auditorium. It’s a room I was aware of but had never seen until Saturday. All day it was open to anybody who wanted to rest a pair of aching dogs and watch old highlight films. As the clock was pushing toward two, that sounded ideal. I found an outlet, plugged my phone in, grabbed a seat and lost myself in the feature presentation, 1986: A Year to Remember. Lord knows I’d seen it before, but never on a big screen and never in the company of dozens of Mets fans.

We’d all seen it before, but it was still impressive (even with the color being off for more than half the video, or did I forget the Astros wearing blue striped shirts?). When Keith Hernandez fields that bunt in Cincinnati and throws to Gary Carter at third, I heard “wow” and “jeez,” because even if you know what’s coming, you’re still blown away by that team. As swell as the proximity to Mets of today and yesterday was on Saturday, looking up at the 1986 Mets as literal matinee idols felt fitting. This is how I knew this larger-than-life team. They were too big for a mere TV. The narration casually mentions the Mets’ lead building to 18 games in August, 19 games in September, and I’m thinking this must sound like a fairy tale for any Mets fan who wasn’t of age in ’86.

Given that our last world championship is one month from turning a third-of-a-century old, there wasn’t much suspense regarding the outcome, but still, I couldn’t believe some lady two rows behind me obliviously took a phone call during the World Series portion. Well, almost obliviously. “Ray Knight just won the Series,” she told her caller before hanging up.

***

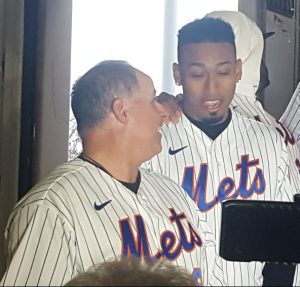

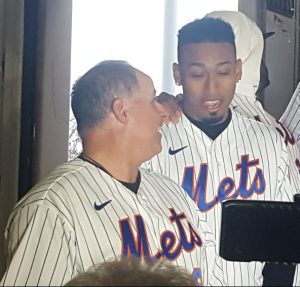

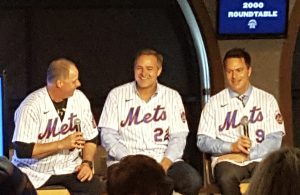

My final mission for the day awaited me in Foxwoods, the 3 PM session billed as the 2000 Roundtable, about as much attention as the Mets have showered upon their fourth of five pennant-winners. As I waited for it to commence, I took in the last minutes of Pictionary with Seth Lugo and Paul Sewald. During the season, I watch them, critique them, rank them, yet there they are being accessible and fun and we’re all happy they’re here, never mind that Lugo is generally terrific and Sewald is less so. Today, everybody’s terrific.

And everybody’s accessible. In about a ten-minute span, Tim Teufel materialized over my left shoulder and posed for anybody who wanted evidence they’d been in his presence; Ed Kranepool sat for photos over my right shoulder; and the guy directly behind me in a McDOWELL 42 jersey was, in fact, Roger McDowell, and he would shake your hand as willingly as he’d give Bill Robinson a hotfoot.

The 2000 Mets appeared as scheduled: Turk, Todd Zeile and Al Leiter. Especially Al Leiter. Al Leiter hasn’t been around all that often since leaving as a free agent after the 2004 season. He showed up for Shea Goodbye. He was on hand when Mike Piazza’s number was retired. Otherwise, he was engaged elsewhere. I had no idea how much I missed Al Leiter, who was the Mets pitcher most worth listening to between Tom Seaver and R.A. Dickey. At one point, Leiter mentioned Casey Stengel. Since I was still wearing my media credential, I resisted the impulse to applaud, but I’m pretty sure I pumped a fist or two (just as I had in the dark theater when we beat Boston).

Al in the middle of things in Flushing like it oughta be. Al, Turk and Todd spoke to the closeness and chemistry of the 2000 Mets — that and the fans. They sounded like Alonso and Cano in the morning, Shamsky in the afternoon. “There’s a grit between us and the fans,” Al said. Zeile concurred: “Plenty of times I sucked and I heard about it,” but that, he said, only made him get better. Turk reiterated what he told me down by the cornhole, that being traded to New York was the best thing that ever happened to him. I didn’t applaud, but plenty did.

I realized here that the point of a FanFest is as much the Mets festing us as it is us festing the Mets. Luckily, we were all on the same page. I also realized, as the 2000 session broke up and I was passed in quick procession by J.D. Davis, Dom Smith and Kranepool — two walkoff heroes from 2019 and one all-time icon forever — that a Mets fan couldn’t get much more out of a January day. It was still cold, misty and raining when I left the ballpark, but on my way home, I saw a rainbow.

That truck must be in Florida by now.

by Greg Prince on 25 January 2020 1:14 pm  Jay Hook is happy to be here.

by Greg Prince on 23 January 2020 3:01 am “I promoted from within. Promoting from within is very big in my family.”

—C.J. Cregg, The West Wing

Once upon a time, some team that wasn’t the Mets did something that got the commissioner’s attention, and ultimately the Mets benefited. Maybe it’s déjà vu all over again 54 years later.

Summoning the greatest fortune-laden precedent in Mets lore — William Eckert spiking the Braves’ contract with USC pitcher Tom Seaver in 1966, leading to a hat and the word “Mets” being picked out of it — may be a glass overflowing interpretation of what’s going on now, but let’s dream big. Let’s dream that the dark cloud out of Houston that deprived us of Carlos Beltran’s managerial services encompasses a silver lining that was under the Mets’ nose the whole time. Let’s dream that we’ve scratched off a lottery ticket that reveals three Alous and wins us the kind of jackpot Tom Hallion’s ass would envy.

Let’s dream that Luis Rojas, the second 22nd manager in New York Mets history, is the best-case scenario to emerge from a bad scene. Rojas, we learned Wednesday, is a dotted “j” from being announced as next man to take the reins in the Met dugout, reins that had been barely gripped by his designated predecessor.

Step right up and meet Luis Rojas, 38 years old and sporting the same major league managerial record held by Beltran and, for that matter, every major league manager entrusted with his first top job. I know of him more or less what you know of him. He’s part of the Alou family (Moises’s brother; Felipe’s son; Jesus’s and Matty’s nephew; and, because genetics ain’t always kind, Mel Rojas’s cousin). He was a Mets minor league manager for a lot of years. He was their quality control coach last year. Based on the archival footage SNY has been airing in a loop, Luis’s responsibilities seemed to include taking part in Opening Day introductions, having two conversations in the dugout, wearing his jersey in a school library, and heading back to the clubhouse after a game.

Rojas has been hiding in plain sight, doing whatever the Mets told him to do and doing it well enough to keep doing it from 2007 forward. He did it promisingly enough to earn an interview for Mickey Callaway’s vacated chair last fall. The consensus from those who likely didn’t think about devoting his candidacy incisive analysis was he’s young and probably required more experience before he would be taken seriously. Three months have passed, one more manager has exited and, suddenly, young Luis Rojas seems to have gained a world of wisdom.

It helps to have been around the organization, to have gotten to know everybody’s name and face, to have been liked by those he’s managed and coached. The wheel was already invented by Brodie Van Wagenen and Jeff Wilpon when they staged the nationwide talent search that yielded Beltran. There was little time for anything but bolting on a sturdy spare good and tight and heading down I-95. The Mets weren’t expecting to start skipper-seeking again so soon. Hell, they’re still paying Mickey Callaway.

Serendipity is an appealing outcome here. I’m reminded of an early episode of The West Wing in which the White House was ecstatic that it got its ideal Supreme Court nominee lined up. Yet before the hour was over, they dumped Peyton Cabot Harrison III in favor of dark horse Roberto Mendoza, with the clear message that Harrison was flawed and Mendoza was the real gem all along. That’s a plot twist we can all get behind.

The second chance the Mets didn’t particularly want theoretically gave them an opportunity to reach out to a name-brand manager they didn’t pursue in October. Whatever philosophical or budgetary issues deterred them from embracing the possibility of Buck Showalter or Dusty Baker in the first place didn’t evolve come January. They wanted their collaborative manager, and if we knew anything about Rojas as a quality control coach, it was that he was regularly described as a “liaison” between the front office and the clubhouse. That’s a pretty new-agey concept for baseball, but for nearly twenty years we’ve been hearing that analytically inclined decisionmakers don’t necessarily think an independently operating field manager is an asset. Even World Series rings aren’t quite the currency they used to be. Other than Davey Martinez in Washington, no team is currently helmed by a manager that won it a world championship, a first for MLB since 1966 and a rarity dating back over a century. No Cora in Boston or Hinch in Houston, obviously, but also no Maddon in Chicago, no Yost in Kansas City, no Bochy in San Francisco. Francona and Girardi are, like Maddon, managing somewhere, but not where they did their gaudiest work. Either the industry is experiencing a brain drain at the managerial level or it doesn’t matter who’s nominally calling the shots because the shots are being determined by committee upstairs.

Still, you need somebody downstairs before, during and after games, especially in front of a microphone twice a day. If Luis can explain why two plus two equals four without wandering off on a tangent that knowing arithmetic isn’t really that important, he’ll already be nimbler than Callaway at dealing with the media. It’s a low bar. The overall learning curve may prove steep, but Rojas will have plenty of support from the organization, albeit the Mets organization. The dugout is crammed with coaches, which may be why we rarely picked Rojas out of the crowd in 2019. I get the feeling that if the sports impostor Barry Bremen, who used to sneak into All-Star team photos and such, were still with us, he could have grabbed a blue windbreaker in March and lasted as a presumed component of Mickey’s staff until June without anybody asking any questions.

Two years ago, Luis Rojas was a name in the media guide, manager of Double-A Binghamton. Two years ago, Brodie Van Wagenen was Jacob deGrom’s agent, sticking his two cents into our consciousness just to let us know his client needed to get paid. Now they’re the successors to Hodges & Murphy, Berra & Scheffing, Johnson & Cashen, Valentine & Phillips, Randolph & Minaya and Collins & Alderson. Those are the manager & GM combos that gave us playoff berths. Let’s stick with dreaming big.

by Greg Prince on 21 January 2020 1:27 pm “I just can’t wait to rewrite our story.”

—Carlos Beltran, November 4, 2019

Baseball is stories as much as it’s statistics; it’s equal parts narrative and numbers; it’s four cups of emotion for every quart of analytics. Baseball is also rules, exceptions and the narrowest of hallways between those two opposing walls.

The rules, written and otherwise, have a real problem with stealing signs. The exceptions are to be kept as quiet as Kevin McReynolds, never expressed with any gesture less subtle than an imperceptible nod. If a center field camera can pick up the slightest movement of a head raising and lowering in a vertical motion, then you’re just asking for trouble. And what are you doing looking at the feed from the center field camera anyway?

After living a week and change with the fallout from the commissioner’s report on a very specific sort of wrongdoing in baseball by a very specific, very successful baseball team, I have come to the conclusion that it all boils down to you can’t steal signs; and if you steal signs, you can’t be elaborate about it — and you simply can’t get caught. It’s not about conceptual good of the game or philosophical issues of integrity. It’s the sign-stealing itself. You don’t do that. You surely don’t do that with anything greater than your eyes or your wits. Eyes and wits are the exception. We’ll romanticize your low-tech cleverness after you’re properly dusted for your sins.

The first time I remember a specific mention of stealing signs was sometime after August of 1984, the month the Mets went into Wrigley Field and were swept four games, basically settling the National League East for the year. Sometime later I read an assertion by a Met that the Cubs had stolen the Mets’ signs, something that fell in the darkest gray area of baseball’s do’s and don’ts. Letting your signs be stolen implies a breach of security on your part, but the stealing of your signs is a breach of etiquette on your opponents’ part, and that, somehow, is worse. However it is viewed, the Cubs, those bastards, had purloined what didn’t belong to them and there was to be no honor bestowed on thieves.

Unless you’re on our side stealing signs, and then you’re a pretty cagey SOB. Steal (or borrow) a glance here, pick up a pattern there, all’s fair in love and gamesmanship if you didn’t get caught. And if you got caught, you’d catch one in your ribs and get the message. Now and then, somebody would allude to somebody blinking a light or poking a head at a furtive degree, but mostly baseball was the great American game, played by the rules, spiced by the exceptions.

Crashing the harmless folklore at the speed of light came the Houston Astros. They did that a lot in the 2010s, losing by grand design, crunching numbers as if on an all-analytics diet and angling for edges nobody else had the nerve to nab. When they added a dash of humanity in the form of past-their-prime veteran leadership, it made them a much warmer story. They’d calculated into their formula for winning the previously incalculable and recently out-of-fashion — that there was something tangible to the intangibles of clubhouse chemistry.

There was something to signing Carlos Beltran, even though Carlos was passing 40 in 2017. He wised up the talented youngsters. He calmed the intensity surrounding daily battle. He consented to a burial service for his own glove. Whatever residual thunder remained in the designated hitter’s bat was a bonus at that point. Beltran was turning a talented team into a legitimate winner. What narrative strand could fill the heart more?

We now know that Carlos’s wisdom included making use of every possible avenue into knowing what pitch was coming next, and with his former Met teammate and now bench coach Alex Cora, they got something cooking with cameras, monitors and a garbage can that was just minding its own business. When it simmered mostly unnoticed in the background, the stew it produced was to be celebrated. The Astros won a world championship. Beltran had his ring at last and could retire on top. Cora, acknowledged far and wide as a certified smart baseball man who aided A.J. Hinch all the way through Game Seven, had the credentials to earn a manager’s spot of his own, in Boston. And within a year of Alex’s arrival at Fenway, the Red Sox were world champions, too. He posted pictures from every win in his office. He rallied his team for breakfast after an eighteen-inning loss. He cared about his battered homeland.

Those were great stories. I got caught up in them. When the Mets aren’t in the postseason, I am prone to whirlwind romances with whoever makes October most intriguing. In ’17, it was the Astros. In ’18, it was the Red Sox. Beltran was a significant part of it for Houston. Cora was the center of it for Boston. Carlos was an old friend, Alex a familiar face. You gotta love stuff like that.

I did. Now I feel a little used, and I’m neither an Astros nor Red Sox fan. I just liked how it all felt for a week or two across a couple of autumns. It was the sort of sensation I’d voluntarily summon for the rest of my Metsless Octobers, that time that team elevated baseball at its highest level to even greater heights. Stuff like that is why I take the World Series seriously.

So that’s more than a little ruined now, and that’s too bad. The reputations of several pillars of the baseball community are in ashes. Hinch was a Leader of Men we could all admire in the wake of those Astros victories that served as a balm for a storm-tossed city, and Houston GM Jeff Luhnow could at the very least be described as rabidly innovative and highly successful. Hinch and Luhnow were suspended by MLB, then fired literally an hour later. Cora was fired by Boston before MLB could get around to fully investigating what he did for the Red Sox. Beltran’s name came up in the commissioner’s report. No other Astro’s did, but it’s understood that didn’t shed a halo of innocent bystanding over the unnamed. In the quickly emerged popular mindset, the 2017 world champs and 2019 league champs formed a suspect lot, especially when you got a load of the squinty evidence of vibrating buzzers underneath jerseys that clearly…or not so clearly…but there was something there…there had to be, because look — he’s not letting them tear his shirt off in a wild celebration because surely he had something to hide.

Allegedly.

In the aftershock atmosphere of disbelief and mistrust, Carlos Beltran, 22nd manager of the New York Mets, never stood a chance. When the commissioner’s report broke on Monday, January 13, it didn’t seem to have anything to do with the 2020 Mets. By Thursday the 16th, it swallowed whole the cerebral cortex of their prospective brain trust — Beltran and what everybody had referred to approvingly as his high baseball IQ.

There’s a scenario in which the Mets stood firm behind the manager they chose when there was little more than whispering regarding the Astros and signs. The Mets were home for the winter in the fall of 2017, figuratively a million miles from that World Series. Beltran may have been named once the garbage can-banging came to light, but he wasn’t suspended. He was just a player then. A decorated player, a sagelike player, a Hall of Fame-bound player, but not a coach, manager or general manager. He was free to go about his business, the business of managing the New York Mets two-plus years removed from whatever he was doing cracking other teams’ codes in Houston.

But is that how you want the Mets to go about their business, with the guy acknowledged as one of the masterminds of a scheme to steal signs that involved cameras and monitors? Maybe it is, and, well, OK, fine. Scandals don’t necessarily take down the scandalizers like they used to do in this society, and the scandalized grow numb to the idea that anything is ever particularly wrong. Plus forgiveness and big pictures. In the big picture, Carlos Beltran’s career and character still came off as a net positive. You could forgive a transgression birthed in murky territory and branched out of control. We forgive, we forget, we compartmentalize.

Last week, though, was no season for equivocation. Mutual parting of the ways was the de rigueur catchphrase of the inelegantly exiting. Alex Cora and the Red Sox mutually agreed to part ways on Tuesday, one day after the Astros, Luhnow and Hinch didn’t overly antagonize amid their respective relationships’ dissolution. As the spotlight shifted to Queens, defiantly powering through prospective criticism as if we were in for a one-, two- or four-day story receded as an option. Mutually assured distraction was the least of it. The Mets would have become the poster children for shady postseason behavior without the benefit of postseason participation.

There was no definitively wrong or definitively right way for them to proceed (except definitively less Metsishly). In some quarters, they’re damned for having done away with Carlos Beltran. In others, they’d be damned had they not. Usually this is all just fiber for a tiresome straw man argument, the part of the plot in which those who don’t care for a point of view say that criticism is inevitable, so why are you even bothering me with an alternative perspective? You know: “if they did sign free agents, they’d be attacked for spending too much”; or “if he’d brought in his closer in the eighth, then he’d just have to answer questions about not having his closer available for the ninth,” as if averting arguments is a higher priority than winning ballgames.

Here it was something to think about, because it was about sign-stealing — about tacitly coming out in favor of sign-stealing by reconfirming that your first-year manager will be the guy fresh off a featured role in a bona fide baseball scandal. There was going to be a ton lip service paid to putting that behind us, especially the scene when Beltran was all “what camera?” when asked about it by Joel Sherman in November. Not everything can be damage-controlled as quickly as its principals would prefer, and damage control is no way to commence a whole new phase of one’s heretofore brilliant professional life.

Given time, I would assume Carlos Beltran will be back in baseball if he so chooses. He’s got decades in the sport, he was one of the best and best-respected players of his time, and I doubt anybody thinks his understanding of the game stops at dissecting ill-gotten video. It’s not permanent condemnation to suggest this isn’t the appropriate moment to have Beltran manage the Mets, yet what he did with the Astros doesn’t and shouldn’t define him for the long-term. I have a magnet with his face on my fridge, a cup with his swing in my office and a t-shirt with his name and number in my closet. I’m not getting rid of any of it.

Meanwhile, here in the short-term, as we verge on the fourth week of January, the Mets sail on sans skipper. Preparation fetishization notwithstanding, it doesn’t matter much that we don’t have a manager when no baseball games are scheduled to be managed. Probably soon they will have someone at their helm. Come Saturday morning, the Mets will open the gates of Citi Field for their their first full-blown FanFest, which seems pretty late for a first FanFest when a franchise is entering its 59th season — later than late January seems late for not having a manager. It would be nice if the fans who are showing up to fest were to be greeted by a freshly selected manager who will spout inspiring platitudes before gathering his charts and graphs and hopping the next flight to West Palm. Then again, we treasure the Mets’ knack for putting on late charges to capture playoff berths and better. Perhaps not having a manager in place three weeks shy of Pitchers & Catchers is a fortuitous omen.

Sooner rather than later, somebody will be appointed, camp will percolate, Opening Day will approach, and it will be like Carlos Beltran’s tenure as the 22nd manager of the New York Mets never happened.

by Greg Prince on 16 January 2020 2:45 am The Mets should definitely keep Carlos Beltran as their manager for the coming season.

The Mets should definitely replace Carlos Beltran as their manager for the coming season.

Major League Baseball did not suspend any of the Astros players for electronic sign-stealing.

Major League Baseball singled out Beltran among all players as part of its report on electronic sign-stealing.

The steps the Astros and Red Sox took to dismiss their managers have no impact on what the Mets do.

After A.J. Hinch and Alex Cora took a hit, the Mets can’t ignore Carlos Beltran’s rather obvious role in this episode.

“We believed in Carlos when we went through a rigorous interview process, and he is still that same person we hired,” the Mets said in an official statement

”More information has come to light making our initial choice untenable,” the Mets said in an official statement.

“Certainly we will face questions as Spring Training begins and the season follows,” one Met source said, “but the near-term distraction will fade as Carlos settles in and the team benefits from his leadership.”

“This is something we don’t need,” one Met source said. “Beltran was already something of an unknown quantity, given his lack of experience, and the questions he’ll face will only add pressure.”

Beltran made a mistake, has owned up to it, and we should all simply move on.

You can’t put a guy at the center of a cheating scandal out front as the representative of your franchise.

Beltran’s career shouldn’t be defined by this episode. He has a long and distinguished record in baseball, and it’s not fair to derail his future as a manager before it even starts.

Beltran can’t be handed this kind of responsibility under this kind of cloud.

Overall, it hasn’t been easy coming to these conclusions. You could just as easily look at it an entirely different way.

Overall, it hasn’t been easy coming to these conclusions. You could just as easily look at it an entirely different way.

UPDATE: We now know Carlos Beltran is out.

by Jason Fry on 9 January 2020 3:15 pm Another year in the books! Another decade in the books! And another class of matriculating Mets to welcome to The Holy Books!

Background: I have a trio of binders, long ago dubbed The Holy Books (THB) by Greg, that contain a baseball card for every Met on the all-time roster. They’re in order of arrival in a big-league game: Tom Seaver is Class of ’67, Mike Piazza is Class of ’98, Noah Syndergaard is Class of ’15, etc. There are extra pages for the rosters of the two World Series winners, the managers, ghosts, and one for the 1961 Expansion Draft. That page begins with Hobie Landrith and ends with the infamous Lee Walls, the only THB resident who neither played for the Mets, managed the Mets, or got stuck with the dubious status of Met ghost.

If a player gets a Topps card as a Met, I use it unless it’s a truly horrible — Topps was here a decade before there were Mets, so they get to be the card of record. No Mets card by Topps? Then I look for a minor-league card, a non-Topps Mets card, a Topps non-Mets card, or anything else. That means I spend the season scrutinizing new card sets in hopes of finding a) better cards of established Mets; b) cards to stockpile for prospects who might make the Show; and most importantly c) a card for each new big-league Met. At the end of the year I go through the stockpile and subtract the maybe somedays who became nopes. (I now have several stacks of nopes — tough business, baseball.) Eventually that yields this column, previous versions of which can be found here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here and here.) If a player gets a Topps card as a Met, I use it unless it’s a truly horrible — Topps was here a decade before there were Mets, so they get to be the card of record. No Mets card by Topps? Then I look for a minor-league card, a non-Topps Mets card, a Topps non-Mets card, or anything else. That means I spend the season scrutinizing new card sets in hopes of finding a) better cards of established Mets; b) cards to stockpile for prospects who might make the Show; and most importantly c) a card for each new big-league Met. At the end of the year I go through the stockpile and subtract the maybe somedays who became nopes. (I now have several stacks of nopes — tough business, baseball.) Eventually that yields this column, previous versions of which can be found here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here and here.)

Enough preamble, let’s get to the amble:

Pete Alonso: Because of the way this feature works, guys get assessed for what they did in their first Mets season, even if that season is relatively brief. Which can leave their THB welcome bios a little scanty, compared with their later biographies. (Though, perspective: If you manage to be a merely interesting Met we’ll devote ~20,000 words to you in a given season. It’s what we do.) Go through previous iterations of this column and you’ll find entries for Dom Smith, Amed Rosario and even Matt Harvey that don’t give much of a hint about what’s to come. Alonso probably deserved a cameo in 2018, and at the time I was bummed that he didn’t get one — and I’m still a little bit bummed, because that meant his career never overlapped with David Wright’s. But the silver lining is we get to give him a full accounting now, instead of a couple of lines about how he’s big and smiley and well, we’ll see. By waiting another calendar year, Alonso became the first to Metriculate in ’19; by doing what he did, he stormed his way to first in our hearts. He collected his first hit in Washington on Opening Day, his first homer in Miami in Game 4, and was off and slugging after that. He smashed the club home-run record by a cool 12 (53 to the seemingly impregnable 41 that had belonged to Carlos Beltran and Todd Hundley), won the All-Star Game Home Run Derby (though Vlad Guerrero Jr. prevailed in its equivalent of the popular vote), won the MLB homer crown (no asterisk required), garnered Rookie of the Year honors, proved far more able in the field than we’d been warned to expect, and was the clear club leader in fan relations, down to stripped-off uniforms, shirt-worthy acronyms, and so much besides. But you know all this already. And that’s the greatest thing of all — a rookie we hoped might hit a few long balls and contribute more runs on offense than he took away on defense put together a pinch-me-I’m-dreaming rocket ride of a season that ended with me saying of his many accomplishments, “But you know all this already.” 2019 Topps Series 2 card in which he’s wearing a dumb blue top. Not to worry; he’ll get a lot more.

Robinson Cano: Hall of Famer as a Yankee, solid player turned PED suspect as a Mariner, Cano came back to New York along with Edwin Diaz (about whom a whole lot more in a bit) in exchange for a mega-prospect (Jarred Kelenic), a useful prospect (Justin Dunn), a lottery ticket (Gerson Bautista), a misfit toy (Jay Bruce) and a guy we never wanted to see again (Anthony Swarzak). It was an odd trade, given the years and dollars left on Cano’s contract and the fact that it pushed Jeff McNeil out of a position he’d more than earned, but there we were. Cano then had an interesting year. He was hurt, he loafed and was kinda sorta not really called out for it in one of Mickey Callaway’s many instances of stepping on his own dick while doing something not particularly complicated, he got raging hot… it was a lot, let’s leave it at that. Cano did get credit for mentoring Amed Rosario during what turned out to be his breakout season, an unquantifiable thing that’s been a storyline in a couple of recent Mets seasons and ought to be thought about more. Still, Cano will be around for four more years at $24 million per, and not one of those seasons is likely to be anything close to a bargain. 2019 Topps team set card in which he’s wearing a Photoshopped Mets jersey. (He got a 2019 Update card, but it was a horizontal, and by now I don’t need to tell you that horizontal cards lead to devil worship, blindness and death.)

Wilson Ramos: We knew about Ramos already, based on him being built like a brick shithouse (I think Noel Coward coined that term) and beating said house’s usual contents out of us far too often as a National. But seeing him every day gave me a new appreciation for him. No, he’s not a great catcher — there were raise-an-eyebrow ERA stats and mild battery controversies and lectures about pitch-framing — but he was such a potent hitter that we usually forgave all that. Plus there was an additional something about Ramos — a glimmer in the eye and an angle at the corners of the mouth that suggested a sense of irony and wise detachment from the ebb and flow of a pitiless, punishing sport. Ramos put together an astonishing 26-game hitting streak during the summer, tying for the second-longest in club history. Twenty-six games! For a 32-year-old catcher! Who has to run at top speed to have a tectonic plate not outdrift him! In the summer! And he didn’t even start in four of those games! And in his last AB he saw nine pitches and was only out because Howie Kendrick made a gorgeous diving stop! 2019 Series 2 card.

Keon Broxton: His floor was “lithe, defense-first fourth outfielder,” while his ceiling was “breakout star.” Alas, the Mets haven’t had luck with this particular player profile for a very long time. Broxton got irregular playing time and didn’t do much with it, which is a familiar Rorschach pattern of failure for players with his profile, and in early May the Mets let him go. He didn’t stick with the Orioles either (ouch), wound up in Seattle and in December came back to the Brewers. And you think you had a complicated year. 2019 Series 2 card, issued after he was already gone.

Edwin Diaz: OK, actually Edwin Diaz had a really complicated year. Arriving after serving as the Mariners’ lights-out closer, the man they call “Sugar” had a pretty good first month as a Met — arriving for work at Citi Field on April 29, he had eight saves to his credit, an ERA of 0.84, and had fanned 20 in 10 2/3 innings. That afternoon, Diaz was brought into a tie game in the 9th and gave up a game-killing homer to Jesse Winkler. Two days later, he was beaten in the same situation by Jose Iglesias. There was a meltdown out in Los Angeles, a gag job against the Cardinals, a disaster in Philadelphia … on and on it went, capped by Kurt Suzuki’s walkoff in D.C. in early September. The Mets had been 806-0 in their less-than-storied history when entering the ninth with a lead of at least six runs; after that one, they were 806-1 and you were entitled to never believe anything again. Calling Diaz’s season a disaster profoundly understates the case; it was a disaster that simultaneously spat in the face of a mathematician’s cool logic, an emo poet’s talent for mordant reflection, and an innocent child’s yearning for reassurance that the universe is not ice-cold and murderous. Every time Edwin Diaz threw a slider in an important spot, it was not just hit but hit out of a ballpark. And yet … he continued to strike out hitters at an elite rate. The ball may be different in 2020, which might help. Or Diaz could simply see his luck regress to the mean, which might help a lot more. Do you feel lucky, Mets fan punk? Well do ya? 2019 Update card in which he’s pumping his fist. Guess it was shot in April.

J.D. Davis: He can’t play third base. Despite working his butt off, he can only kind of play left, and that’s if you squint a lot and have rosary beads close at hand. What he can definitely do is hit. Jonathan Gregory Davis — the “J.D.” is a back-formation from his initials — was an odd man out with the Astros, picked up by Brodie van Wagenen in the best trade of his tenure so far. Davis slugged 22 homers, was money at home and in the second half, and became Pete Alonso’s sidekick in everyone’s favorite buddy comedy of the year. The Polar Bear dubbed Davis “the Sun Bear” (as Greg noted, “the Solar Bear” was just sitting there), and Davis was the Met I was most likely to confuse with an adorably insane cartoon character. There was his sleeveless, drenched WWE-style postgame interview after beating the Indians, but my favorite moment was his heckle of the Cubs after another Alonso homer. Davis has a lot of talents, but heckling isn’t one of them: He has a voice that doesn’t travel, coming out pinched and reedy instead of deep and booming. “Whaddya gonna throw ‘im?” Davis screeched at the Cubs from the dugout as Alonso circled the bases. “WHAT NOW?!” Four months later, it’s still making me laugh. Given their glut of outfielders and Davis’s limitations, the Mets might be better off trading Davis for much-needed parts, but I hope they don’t, because it really might break my heart. 2019 Series 2 card in a stupid blue top.

Justin Wilson: The unassuming-looking Wilson arrived as a 31-year-old pitching for his fifth organization and had a 4.82 ERA in early May when he went on the IL with a stubbornly sore elbow. Nearly two months later, I was sitting a couple of rows from the bullpen mound in the Staten Island stands and noticed the Cyclone warming up about eight feet away had fancy personalized cleats. The answer to this mystery: It was Wilson, whom I not just hadn’t recognized but also hadn’t thought of since he vanished. A couple of days later, Wilson was back with the Mets and was one of their most dependable relievers for the rest of the year. Middle relievers, man. Go figure. 2019 card from the resurrected Topps Total brand.

Luis Avilan: A lefty specialist, Avilan was sent out against righties early in the season, which didn’t go well. Imagine that! He then got hurt and was out from early May through early July with elbow tightness. (No, I didn’t copy and paste this from Justin Wilson’s entry.) When he returned, he faced mostly lefties, and things got much better. Imagine that! For the year, Avilan held lefties to a .102 average, but was battered by righties at a .373 clip. The three-batter minimum may play havoc with his career next year, but then the same was true about working for Mickey Callaway. It’s true Carlos Beltran has no record as a manager, but his lifetime NBMC percentage — that’s a new stat called “Not Being Mickey Callaway” — is 1.000. 2016 Topps card from back when he was a Dodger.

Ryan O’Rourke: Appeared twice in early May, pitched 1.1 innings, was sent down, recalled again at the end of the month, but optioned before appearing in another game because the Mets needed a spot for Aaron Altherr. Did they really, though? 2019 Syracuse Mets card. It’s very orange.

Adeiny Hechavarria: I already disliked Hechavarria for being an annoying, sporadically good Marlin, and huffed and puffed when the Mets signed him as infield depth for 2019. But hey, maybe he wouldn’t be called up? The Mets called him up at the beginning of May to avoid losing him because of an opt-out clause in his contract, a move I excoriated at length, decrying Hechavarria as the kind of Proven Veteran™ who only gets a roster spot from teams that have no strategy except avoiding criticism from crusty old baseball lifers who also have no strategy. Which wasn’t incorrect, really, except Hechavarria played pretty well for a brief stretch. In such situations I always say I’m glad to be wrong, but I was glad with a big seething asterisk. With Robinson Cano back on the active roster, Hechavarria rode the bench and was ineffective in a part-time role. The Mets designated him for assignment shortly before a $1 million option would have kicked in, which was simultaneously a sound baseball move and typically cheapjack Wilponian shit. Hechavarria wound up as a Brave, hit .328 for them, and thanked God for delivering him from the Mets. Oh but wait: He then singlehandedly tried to ruin Closing Day, connecting for a home run in the ninth off Paul Sewald to tie the game at 4-4 and then hitting another one in the 11th off Walker Lockett to give the bad guys a 5-4 lead. Dom Smith saved us from the Adeinypocalypse, thank God, and my last look at Hechavarria was while his team was being destroyed by the Cardinals in one of baseball’s all-time postseason beatdowns. He didn’t play, but I made sure I caught a glimpse of him, because I am in fact that petty. He’s now a free agent, hopefully bound for a league in Korea, Antarctica or on Mars. Go away, Adeiny Hechavarria. Go away forever. 2019 Topps Total card as a Met, which I wish didn’t exist.

Wilmer Font: Baseball wouldn’t work without ham-and-eggers like Font, guys who eat innings and keep getting looks because a) there’s talent there and someone always thinks they’ll be the one to unlock it and b) somebody’s got to take the ball. But while baseball needs a steady supply of Wilmer Fonts, something’s gone wrong if one of them is on your roster for more than a couple of weeks. The Mets acquired Font from the Rays in May and sold him to the Blue Jays in July; a couple of years from now he’ll show up in another uniform during the fourth inning of some snoozy game and you’ll cock your head, say “oh yeah, him” and the person next to you won’t remember. 2019 Topps card as a Ray.

Rajai Davis: On Nov. 2, 2016, the Cubs were up 6-4 on the Indians in the eighth inning of Game 7 of the World Series, with two outs and a runner on second. The Cubs hadn’t won the Series since 1908; the Indians hadn’t won since 1948. Facing Chicago’s Aroldis Chapman was Cleveland journeyman Rajai Davis, with 55 homers to his name over an 11-year career. Davis hit Chapman’s seventh pitch over the left-field wall, tying the game and unleashing bedlam at Progressive Field. Unfortunately, the Cubs won in the 10th, which always make me wonder how Clevelanders view Rajai Davis. He’s a hero, obviously, but how much of a hero? Will he never have to buy a drink in that town? You’d think … except the Indians didn’t win. So, I dunno, maybe he’ll never have to buy a first drink in that town? Anyway, Davis became a Met on May 22, arriving when the team finally figured out Brandon Nimmo was actually hurt. In his first Mets AB, Davis clubbed a three-run homer in the eighth inning off the Nationals’ Sean Doolittle, the exclamation point on a four-game sweep. (To get in uniform, he had to take a $243 Uber ride from Pennsylvania.) Then, in September, Davis hit a bases-clearing double off the Dodgers’ Hyun-Jin Ryu to break a scoreless eighth-inning tie, keeping the Mets’ season alive. He didn’t do much in between, but with moments like those two, he didn’t have to. 2019 Topps Total card.

Aaron Altherr: Two days after Rajai Davis homered in his first at-bat as a Met, Aaron Altherr did the same thing, launching a sixth-inning homer to give New York a brief-lived 7-6 lead over the Tigers. He did almost nothing else of note, so any expensive Uber rides he took weren’t deemed newsworthy, and he wound up with an .082 batting average for the year. 2018 Topps Heritage card as a Phillie.

Hector Santiago: He spent nearly a month as a Met, most of it during June when everyone paid to pitch baseballs for a living was hurt. You’d think I’d remember a guy who was on our roster for a month, but I didn’t. Googling revealed he was the winning pitcher in the Tomas Nido game. Ah. That I remember — I was in a Thai restaurant with friends, peeking down at Gameday on my phone, which was tucked between my knees. That made me remember that Santiago did his best to lose the game he won, throwing about a billion balls and perilously few strikes and somehow escaping getting eaten (figuratively) by Tigers. Honestly, I was better off not remembering him. 2019 Syracuse card.

Brooks Pounders: Baseball is reliably hilarious, in ways both unexpected and thoroughly expected. If I told you there was a pitcher named Brooks Pounders and asked you to come up with a capsule biography, you’d probably decide he was a hefty middle reliever with a dog’s breakfast career spread over multiple organizations. And you’d be right! The joke within a joke is while Pounders appeared in seven games with the Mets and racked up a 6.14 ERA, he only gave up a run in one of those appearances, a 13-7 disaster against the Phillies where no pitcher covered himself in glory. Still pretty funny. 2017 Topps Update card.

Stephen Nogosek: As the 2017 season crumbled into wreckage, the Mets traded away pretty much every player someone wanted, which was understandable. What was less understandable was that in every deal, the Mets got the same underwhelming thing back — a right-handed minor-league reliever considered a lottery ticket by scouts. Exit Lucas Duda, Addison Reed, Jay Bruce, Neil Walker and Curtis Granderson; enter Drew Smith, Gerson Bautista, Jamie Callahan, Stephen Nogosek, Ryder Ryan, Eric Hanhold and Jacob Rhame. It’s only a mild oversimplification to say the Mets acquired the same pitcher with seven different names, like they’d been dropped into a straight-to-video knockoff of Highlander in which the immortal hero’s bad at swordfighting. Nogosek pitched effectively in the minors last year, so maybe he’ll be the wheat amid the chaff, but I’m not holding my breath. I’m also not looking forward to seeing Ryder Ryan come up this July and surrender four earned runs in 1 1/3 on a getaway day in Cincinnati. 2018 St. Lucie card in which Nogosek’s sporting an ill-advised mustache. That card probably cost me $5 on eBay. Stupid Mets.

Walker Lockett: I hated Tommy Milone. Actively detested him and would writhe around on the couch in torment when he was on my TV. I just felt sorry for Walker Lockett … and for myself, and for all the rest of us. Why does God allow such things to happen? 2017 El Paso Chihuahuas card. Yes, that is an actual professional baseball team. Why does God allow such things to happen?

Chris Mazza: We make fun of interchangeable middle relievers and one-and-done spot starters, and it’s an acceptable coping mechanism for staying sane as fans — so long as we remember that even the least of these guys is a world-class athlete who’s spent years and years working his ass off doing something incredibly hard for a lot less money than we think. Mazza turned 29 about two months before the Mets made him a minor-league Rule V draftee in December 2018. He’d been released by the Twins in 2015, by the Marlins in 2018, and if you thought his future looked bright, you were either a family member or a truly incurable optimist. But Mazza proved useful in Binghamton, got the call to Syracuse and did OK, and in late June he found himself in the big leagues, wearing blue and orange striped stirrups he bought himself on Amazon. So how’d it go? He was in line for his first big-league win during a grim Verdun of a game against the Giants in July — 1-2-3 15th inning, on long side after a Pete Alonso homer — but imploded in the 16th, facing five batters and retiring none of them in one of the season’s more frustrating losses. But the story isn’t done yet! Did you know Chris Mazza threw the last pitch for the Mets in the 2010s? He relieved Walker Lockett on Closing Day, got Francisco Cervelli to ground into a double play with the only pitch he threw, and was the pitcher of record when Dom Smith sent us all home happy. That’s a big-league victory, in so many ways. He’s now 30 years old and Red Sox property; Godspeed, Chris Mazza. An old Jacksonville Suns card. Their unis were better in the days of Amos Otis and Gary Gentry, trust me.

Marcus Stroman: If you want to understand the depths of Mets-fan trauma, the team’s acquisition of Marcus Stroman in July could be Exhibit A. At first glance, Stroman’s surprise acquisition should have been great news, bolstering an already-strong starting corps with the team fighting for a wild-card berth. Except it was widely assumed Stroman’s acquisition was the prelude to the team dealing away Zack Wheeler or Noah Syndergaard with an eye on future salary obligations, which would not have been great news. And that scenario only seemed more likely after the Mets trumpeted Stroman’s Long Island roots and high-school rivalry with Steven Matz — among their other fine qualities, the Wilpons are deeply parochial, the kind of people who think a feel-good local story will mesmerize fans and keep them from asking pesky questions about payroll. As it turned out, the Mets traded neither Wheeler nor Syndergaard, fell short of the wild card, but then let Wheeler become a Phillie without stirring from their slumber, so you tell me what the plan was, assuming there ever was one. The silver lining at the center of all that was Stroman himself, an undersized, overamped bulldog of a pitcher, demonstrative on the mound and in the dugout. It was a pleasure to watch him in 2019; it’s a pleasure to think that there’s more to come. 2019 Topps Heritage card, as a Blue Jay.

Donnie Hart: Threw nine pitches in one inning for the Mets, recording three groundouts near the tail end of a blowout win over the Pirates. That was in August, on a night I had duties at a sci-fi con in Tampa, Fla. I missed that part of the game and so in all likelihood missed Donnie Hart’s entire Mets career. First Met I’ve completely missed since I moved to New York in 1995? It’s possible. Thanks to the magic of the MLB.tv archives I could go relive the Donnie Hart era in all its glory, but I think it’s more poignant and poetic to leave things the way they are. 2017 Topps Chrome card as an Oriole — autographed, no less.

Joe Panik: A San Francisco Giant legend, Panik was born in Yonkers and went to St. John’s, playing in the exhibition game against Georgetown that christened Citi Field back in 2009. (Panik went 2-for-4; I was there but won’t pretend I remember him.) Given all that, a homecoming was inevitable once it became clear that Panik no longer had a place with the Giants. With Robinson Cano on the shelf, Adeiny Hechavarria and his impending $1 million option were subtracted, Panik was added, and on we went. Panik started out with a hot couple of weeks, cooled off after that, and all in all was perfectly serviceable before becoming a free agent at season’s end. Honestly, Joe Panik not being Adeiny Hechavarria would have been enough for me. I hate that guy. 2019 Topps Heritage card, as a Giant.

Brad Brach: The Cubs signed Brach before 2019, and it looked like a good move — Brach had proven reliable with the Padres, Orioles and Braves. But it all went to hell in Chicago, and the Cubs released Brach and his 6.43 ERA at the beginning of August. The Mets figured out he’d been tipping his change-up and fixed the problem; even before then, Brach endeared himself to us by revealing that he’d attended a 2015 World Series game, not as a laminated-thing-around-the-neck MLB guy but because he’d grown up in Freehold as a huge Mets fan. (I will not be taking questions about parochialism and/or hypocrisy at this time, thank you.) Emily noted that neither “Brad” nor “Brach” exactly rolled off the tongue while cheering from the couch, so she invoked him by his full name, which turned into “Breadbox” within a homestead or two. Worked for me. Breadbox will be back in 2020, hopefully remaining rubber-armed and useful. Yet another 2019 Heritage card, as a Cub.

Sam Haggerty: Looking for a path to the big leagues when you’re not considered a front-line prospect? Your best bet is to be a good defensive catcher; if you’re not, raw speed is a good Plan B. Haggerty got the call in September after spending most of the season at Double-A, with a video of Syracuse manager Tony DeFrancesco delivering the news going mildly viral. Used mostly as a pinch-runner, he scored two runs and was hitless in four ABs. The first of them was a nice September moment, with the entire team paying avid attention from the dugout and the Citi Field crowd cheering him on. The Mets released Haggerty this week, but whatever else he does in life, he’ll always be a major leaguer and that’s awesome. 2019 Rumble Ponies card.

Jed Lowrie: He lives! A truly star-crossed acquisition, Lowrie came aboard as a useful veteran expected to log time at multiple infield positions, but came down with a sore knee in February and then shit got weird. There was talk of him returning in May, but there was a hamstring problem, Brodie Van Wagenen poked his head up momentarily to babble about kinetic chains, other body parts malfunctioned in ways no one seemed inclined to explain, and eventually we all shrugged and forgot about Jed Lowrie. I wonder, idly, if 2020 spring training will bring an article that recounts his odd lost season, and if that article will reveal that there was something wrong nobody wanted to talk about, or merely detail a perfect storm of physical woes. Whatever the case, Lowrie came to the plate as a Brooklyn Cyclone in the New York-Penn League playoffs and I reacted like I’d seen a UFO. He then made a miraculous return to the big-league roster in September … and went hitless in eight thoroughly unmemorable plate appearances. 2019 Topps Heritage card in which he’s a Met but looks like he’s holding very still out of fright. Honestly, it’s perfect; perhaps it’s even the moment when whatever happened to him happened.

by Greg Prince on 4 January 2020 10:49 pm I admittedly know nothing about ranching, but if ranches are prone to wild boar attacks, then I can’t really blame Yoenis Cespedes for taking steps to prevent a wild boar from attacking him on his ranch. And if a wild boar winds up breaking free of the trap set by the proprietor of stately La Potencia Ranch of Vero Beach, Fla., I also can’t blame Cespedes for trying to avoid the wild boar, as he apparently attempted…and if Yoenis’s defensive action here was less effective than the kind that won him a Gold Glove for his work in Detroit, and it resulted in him fracturing an ankle by falling into a hole…well, I’m sorry he got hurt more than he already was from double heel surgery — and I’m glad he didn’t get hurt worse.

All that said, geez, what an (ahem) unusual story the Post reported Friday night. It was already out of leftfield that the left fielder’s insanely large-in-hindsight contract was slashed to merely ludicrously large-in-hindsight. That basically never happens in baseball, but the Mets got back many of the millions upon millions they were supposed to be paying Cespedes, since Cespedes was supposed to be not letting wild boars get in the way of him trying to play baseball again relatively soon. Or something like that. When we heard that Cespedes’s deal was reduced like Cespedes’s gear was in the Mets’ team store once “La Potencia” definitively rhymed with “in absentia,” we more or less figured it had something to do with the what-else-is-new? news that Yo took a spill into a hole on his ranch. But we didn’t know exactly what that bit of business was about when it was revealed last May.

Now we do. It was about Yoenis Cespedes trying to stay on peaceful terms with a heretofore trapped wild boar who wasn’t crazy about having been trapped. It could happen to anybody.

Anybody on the Mets, especially.

by Greg Prince on 3 January 2020 3:35 am I learned two things from watching Brodie Van Wagenen’s official introduction of Dellin Betances on Thursday, as streamed by SNY:

1) Brodie Van Wagenen believes we are more interested in negotiation protocols and processes than we actually are. Stop telling us what miracles you and your compatriots have worked by hammering out a contract offer to a player who you’re convincing us out the other side of your mouth wanted nothing more than to play for us or at least our geography. I don’t expect Betances to pull an Andre Dawson c. 1987 and let the Mets fill in however small a collusive number they feel can masquerade as fair, but why is the GM describing for us the horrible stress there was in getting a New York-based pitcher into a New York-based uniform? Just cut straight to, “It’s great that Dellin’s a Met.”

2) It’s great that Dellin’s a Met.

The second part of my BVW-generated education is a best-case scenario. Everything about the Mets’ bullpen — which was mostly a living, breathing, cringe-inducing worst-case scenario in 2019 — asks that we see the best in all involved. Edwin Diaz will get his head and slider together and revert to 2018 greatness. Jeurys Familia, lighter physically, will be solid mentally and throw sinkers with requisite heaviness. Seth Lugo won’t be unhappy to be in relief and remain just as good as he was when he was the exception to the drool. Michael Wacha will be delighted with his role once he discovers he’s the sixth starter in a five-man rotation.

And Dellin Betances will overcome a year of injury-laden inactivity and return to being the monster that made him a four-time All-Star and an anchor within the bullpen on the other side of the Triborough. It’s a big if (he’s a big pitcher), but if we get that, and we get all the other ifs to break our way…well, let’s just say the Mets bullpen hasn’t blown a lead yet in 2020.

___

Don Larsen was the best that he could be on October 8, 1956. Throw a perfect game in the World Series and you’ll never have to pick a day when you’re any better. Of course that was Larsen’s calling card for the rest of his life, and naturally it’s what we all recalled about the former major league pitcher who died on New Year’s Day at the age of 90.

Thing is, Larsen didn’t just touch down from thin air in Yankee Stadium that Monday afternoon more than 63 years ago. He’d been pitching in the bigs since 1953 — commencing with the St. Louis Browns of all things — and he’d keep pitching professionally until 1968. His last MLB action came in 1967 with the Cubs, but he stayed at his craft another season beyond that in the minors.

Few think of Larsen as anything but the Yankee starter and winner in Game Five of the 1956 Fall Classic, throwing 97 pitches that never resulted in a baserunner and catching a jubilant Yogi Berra after the last of them was called strike three on Brooklyn Dodgers pinch-hitter Dale Mitchell. Twenty-seven up, twenty-seven down. Why would you think of Don Larsen in any other context?

Except I have. When Larsen died, I thought of how I ran across his name repeatedly during some research I was doing of Met box scores from their early years. It felt anachronistic seeing Larsen appear in anything but World Series kinescopes, but he didn’t ascend to the heavens after the last out. There were other games for him to pitch, none of them perfect; and other hitters for him to challenge, not all of them helpless against his stuff.

Take the Mets of 1964, for example. The Mets of 1964 were helpless a lot, but against Don Larsen, they found their groove, defeating him four times, once when he was with the Giants, three times after he’d been sold to the Colt 45s. The Mets had never before beaten any pitcher as many as four times in a single season, and they’ve done it only thirteen times since — and never while en route to a tenth-place finish. Larsen lost to the 1964 Mets twice as a starter, twice as a reliever. One of the starts was a classic hard-luck defeat, as Don scattered eight hits over seven innings but was outdueled by Frank Lary, who tossed a two-hit shutout for the Mets. The game could also be termed a Ron Hunt special, as the National League’s starting All-Star second baseman gladly accepted a Larsen pitch to his person with the bases loaded to push the first run of the game across the plate. (Larsen’s catcher at that moment? None other than Houston’s 21-year-old rookie receiver Jerry Grote.)

Losses were more prevalent than wins in Larsen’s career. Not that we take Ws and Ls all that seriously anymore in this age of deGrominant enlightenment, but Don was an 81-91 pitcher overall — yet a 4-2 pitcher in five World Series, and 1-0 with zeros across the board on 10/8/56. How can you not love baseball knowing that the imperfect man who threw a perfect game at the perfect instant was also the first pitcher to lose four games in a season to any Mets team, especially a Mets team that went 53-109 overall? Nevertheless, we shall remember the man at his best.

___

Andy Hassler at his best was pretty decent. That was mostly in the American League, where the lefty began pitching out of view of Mets fans in 1971. His won-lost mark didn’t exactly shine, but he kept finding his way to teams aspiring to postseason. Hassler helped the Royals make the playoffs in 1976 and 1977 and then joined the Red Sox as they attempted to not let a large AL East lead get away in 1978. That didn’t go as well, but it should be noted that in the eighth inning on October 2, 1978, directly after Bob Stanley gave up a leadoff home run to Reggie Jackson that allowed the Yankees open a three-run lead at Fenway Park, Hassler entered the one-game playoff to decide the division and shut the door, retiring Nettles, Chambliss and White in order, and then coming back for two more outs in the top of the ninth, by which time the Red Sox had closed the gap to 5-4. The Bucky Dent Game ultimately wound up one run out of Boston’s grasp, but it wasn’t Andy Hassler’s fault.

In the middle of the following season, at the June 15 trading deadline, the Red Sox sold Hassler to the Mets, the same day the Mets traded Mike Bruhert and Bob Myrick to Texas for Dock Ellis. If you didn’t know any better, you’d assume the Mets were making a big move in their division, bringing in a pair of veteran starters with October pedigrees. But, no, this was 1979, and the Mets were just trying to get through the season.

Still, Hassler — who died on Christmas Day in Arizona at 68 — gave the Mets some quality pitching during the balance of that benighted year. Like Larsen against Lary in 1964, Andy unfortunately saved his 1979 best for somebody else’s even better. On the Fourth of July in Philadelphia, Hassler pitched a complete game: eight innings, five hits, one lousy third-inning earned run allowed on back-to-back doubles to two lefthanded batters: Steve Carlton and Bake McBride. Carlton, who is one of those thirteen pitchers after Larsen to lose at least four times in a season to the Mets (amid his 27-10 1972 campaign, no less), chose this Independence Night to flirt with his own brand of perfection. The bid for regular-season Larseny, so to speak, was foiled when Elliott Maddox reached Silent Steve for a one-out double in the seventh. Carlton would create a little more trouble for himself by committing an error on a grounder hit to him by Richie Hebner. But he’d escape the mini-jam, and that would be the extent of Met baserunning for the evening. The game wound up Phillies 1 Mets 0, with a one-hitter going in Carlton’s column and another among 71 career losses (versus 44 wins) the best Hassler could collect.

Andy may not have thrown any more gems of that caliber in 1979, but he did give Joe Torre a touch of flexibility, racking up four saves, three of them in September. The combination of eight starts and four saves is unusual in Metsian annals. Hassler’s season in Flushing — a partial season, at that — is one of only seven meeting those versatile parameters in Mets history. In fact, something like it has been achieved only twice since Hassler did it. Anthony Young started 13 times in 1992 while saving 15 games, and Hisanori Takahashi saved eight in 2010 on top of making twelve starts.

Hassler, who would leave as a free agent, couldn’t prevent the Mets from settling deep into the basement in 1979. Nor could Ellis, who New York would sell to Pittsburgh down the stretch of their spurt toward the World Series. Wayne Twitchell was another veteran pitcher the Mets hoped could eat up some innings that season. Twitchell did for a while, until he was sold to Seattle. Only a Mets fan of a certain vintage and intensity would think of this trio as Mets rather than members of the teams where they made their more indelible (or Dellinable) marks. Yet at least one Mets fan moved to linger over the 1979 Mets’ game log page on Baseball-Reference can’t help but notice that the pitchers of record on the losing side three consecutive nights in early July in foul, fetid, fuming, foggy filthy Philadelphia were Dock Ellis, Wayne Twitchell and Andy Hassler. They were all Mets in passing, yet this Mets fan looks at those names; remembers them as Mets; and is certain each man did his best while a Met.

They weren’t perfect, but hardly anybody is while on a major league mound.