The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 12 February 2025 6:15 pm The distance from No. 11 to No. 10 on any list is both incremental and immense. Top Ten implies a level above all others. Therefore, with all due respect to all others, welcome to the Top Ten portion of MY FAVORITE SEASONS, FROM LEAST FAVORITE TO MOST FAVORITE, 1969-‘PRESENT’ (with 2024’s slotting TBD), where things are getting more serious, which is to say more favorite.

Or does it say something else? I’ll stand by “Favorite” as the unifying adjective of this series, as the idea when I kicked it off on the final day of 2023 — when 2023 encompassed all the present we knew about — was to work my way up from Met seasons I didn’t enjoy a ton (but I was determined to say something nice to say about each of them), through Met seasons that struck me as evocative blends of fun and futility, straight up to those seasons I clearly love more than any others. You know: the Top Ten.

Except maybe favorite isn’t the most operative word as we rise to the upper tier of this extended exercise in Met reflection. The seasons about to be entered here were, for me…what? Meaningful? Influential? Formative? Each of the above — but without the anger and regret and that informed other meaningful, influential and formative seasons further down the chart. With happiness the prevalent mode in each season remaining to be counted down, I guess ‘favorite’ still works, but it seems worth noting, as we eventually visit certain years that weren’t conventionally successful and find them ranking higher in my very personal esteem than years that earned banners, that favorite encompasses so much more than wins, losses and flags.

It’s the Mets. It’s never obvious.

That said, it is indeed Top Ten Time. On with the countdown, and an authentic banner year.

***

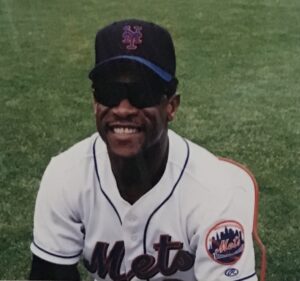

10. 2000

It is now slightly over a quarter-century since we heard the word “century” used more than any of us will likely ever hear it again. And forget about a future surge in “millennium” — it crested for the duration of our lifetimes and the lifetimes of dozens of generations ahead of us back then. Occasionally I see a business that carries the name “Millennium” in its title, and I think it must have served as a better short-term attention-getter than long.

Yet the century and millennium whose border we drifted across in 2000 (“but there was no Year Zero” protestations notwithstanding) are still here. Just as are the Mets, who were as much the focus of my existence 25 years ago as they’ve ever been.

You don’t essentially build your life around a team you don’t love, and you don’t do it in a season you don’t love. I loved the Mets in 2000, and I loved the 2000 Mets. Those might read as identical statements, but I believe there’s a delineation to be divined. Truly loving the Mets at any given moment indicates your fandom is turned up high, no matter who’s on the Mets. My fandom for this enterprise, this going concern, this (as Tony Soprano regularly referenced Sunday nights at nine) thing of ours was already ratcheted skyward as the previous century closed its books. I saw no reason to diminish my fervor when the chronological odometer flipped over. You don’t essentially build your life around a team you don’t love, and you don’t do it in a season you don’t love. I loved the Mets in 2000, and I loved the 2000 Mets. Those might read as identical statements, but I believe there’s a delineation to be divined. Truly loving the Mets at any given moment indicates your fandom is turned up high, no matter who’s on the Mets. My fandom for this enterprise, this going concern, this (as Tony Soprano regularly referenced Sunday nights at nine) thing of ours was already ratcheted skyward as the previous century closed its books. I saw no reason to diminish my fervor when the chronological odometer flipped over.

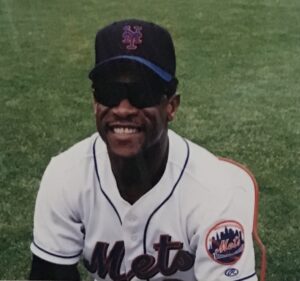

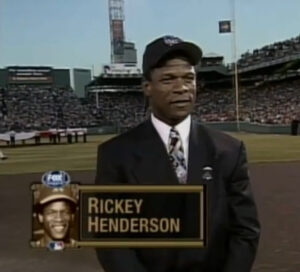

The 2000 Mets as individuals coalescing into a unit was a slightly different story. Years After, as recently discussed in this space, can be a hard internal sell, because Years After are inherently Not The Same. The Year Before 2000 was a banner year in its own right, one that couldn’t help but end. Kenny Rogers made sure of that. So did John Olerud and Masato Yoshii and Orel Hershiser and Octavio Dotel and Roger Cedeño and Pat Mahomes (and Bobby Bonilla, when he said “sure” to a sweet deferral deal). A few players take off your uniform and put another on every year, even years you cherished. It takes a minute or more to embrace their replacements.

So hi, Todd Zeile; and hi, Mike Hampton, and hi, Derek Bell, and hi, whoever else wasn’t here last year. You will wear orange and blue and an uncomfortable quantity of black, and you will mesh in your own way with Mike and Robin and Fonzie and Al and Reeder and so on, but you’ll be a different group. You might be welcome as you join us, but you can’t blame us if we consider you to be strangers before you emotionally become some of our own.

Eventually, the 2000 Mets become a group to have and to hold and to root as hard for as we did the 1999 cast. They maintain the general standards that have been established here in recent seasons. They are quality players and quality people, from what we can tell, and drama can’t help but swirl about them. Bobby Valentine is still managing, so, yeah, it’s never dull. That’s mostly good.

Somewhere past the middle of the season, something quietly happens. The 2000 Mets grab hold of a playoff spot in the standings on July 27 and they never let go. That’s what the 2000 Mets do. They win more than they lose and, given the experience enough of them garnered in the late 1990s (whether as Mets or whatever they were before becoming Mets), you mostly trust them to keep on keeping on.

Given who I am, I do the same. “Act like you’ve been there before” is usually brandished as a cudgel toward any player who flips a bat and pumps a fist too excessively after whacking a ball clean out of sight. One of the pleasures of 2000 for me was having “been there” in 1999. The Mets were a playoff team working toward being a playoff team again. They legitimately worked at it. They were mature that way. Part of their innate likability was that they were a solid citizen of baseball. They weren’t leading the Wild Card pack and staying on the Braves’ divisional heels by luck or accident. Even if the soul of the team came off a little more muted than the ’99 version’s, they still had that Amazin’ something about them. It was just a year older. Given who I am, I do the same. “Act like you’ve been there before” is usually brandished as a cudgel toward any player who flips a bat and pumps a fist too excessively after whacking a ball clean out of sight. One of the pleasures of 2000 for me was having “been there” in 1999. The Mets were a playoff team working toward being a playoff team again. They legitimately worked at it. They were mature that way. Part of their innate likability was that they were a solid citizen of baseball. They weren’t leading the Wild Card pack and staying on the Braves’ divisional heels by luck or accident. Even if the soul of the team came off a little more muted than the ’99 version’s, they still had that Amazin’ something about them. It was just a year older.

Me, too. I’d lived and died (and resurrected repeatedly) as Mets fan in 1999. Now I’d landed in this new year/decade/century/millennium with an enhanced sense of knowing what I was doing as a fan. A fan in full. I’d ascended to a certain Peak Mets state of being. It wasn’t only that I went to a lot of games — though I did — and it wasn’t only that I hardly missed an inning — though I didn’t. The agency I nurtured and the commitment I forged were born of an incandescent passion. My Met light was never off. My Met heart never stopped beating. I can honestly say I didn’t go a waking hour without organically thinking about the Mets. Maybe that’s still the case, but it felt deeper then.

If everything was 162 games of smooth sailing, the mind might have wandered. Dissecting what it was really like to live then, no, nothing was a sure thing. There were losing streaks and there was frustration and there was doubt. There were the Mets being the Mets, which even in the best of times eludes serenity. But there really was an inner confidence to rooting for the 2000 Mets. It could go off the rails, but I’m gonna stay on board and trust whoever’s driving this train. I think it’s gonna be OK. At least that’s how I opt to remember it.

It was pointed out amid the 1950s nostalgia infiltrating 1970s pop culture that, once you factored in segregation, McCarthyism, societal conformity and so many other issues that defined daily living way back when…well, they weren’t all happy days. Yet twenty years later, you could roll out select signifiers of a time gone by and convince yourself that back then was the time to be alive. I think that might be what 2000 has become for me Metwise. I fretted with every third out or fourth ball or whatever didn’t go in our favor, but those were the days, huh? Mike and Robin and, yes, Fonzie — plus Hampton and Zeile and this kid Timo Perez who joined the lineup in September and hit an inside-the-park homer in Philly. Look at him run! Timo Perez takes nothing for granted on the basepaths!

Those happy days were yours and mine. Certainly mine. We were a plucky powerhouse from March in Tokyo to October in Flushing. We did make the playoffs. We did win an NLDS while holding our breath for four games. We did win the pennant while roaring aloud for five games. We came back on the Braves one night with ten runs in the eighth inning. We — the team, the fans — made Shea shake. We did some incredible things. We did a slew of hypercompetent things. It added up to almost everything we wanted. I was there for almost all of it. I didn’t go to the World Series, and the Mets didn’t show up for quite as much of that intracity affair as we wished, but I know I saw them line up for it on TV. Those happy days were yours and mine. Certainly mine. We were a plucky powerhouse from March in Tokyo to October in Flushing. We did make the playoffs. We did win an NLDS while holding our breath for four games. We did win the pennant while roaring aloud for five games. We came back on the Braves one night with ten runs in the eighth inning. We — the team, the fans — made Shea shake. We did some incredible things. We did a slew of hypercompetent things. It added up to almost everything we wanted. I was there for almost all of it. I didn’t go to the World Series, and the Mets didn’t show up for quite as much of that intracity affair as we wished, but I know I saw them line up for it on TV.

With the exception of securing a world championship, we scaled the Apex Mountain of Metsdom. I use first-person plural when maybe I should use the singular here. Fine, I was on my version of Apex Mountain. Losing the Fall Classic to whom we lost it understandably dims the glow of the collective Metropolitan memory of 2000. I dig. But I dug too much of what preceded our Subway Series shortfall to toss it all into a hole in the ground. New York, New York? We were a helluva team having a helluva year.

One other, rarely mentioned upside to immersion in the Mets in the fall of 2000 that we couldn’t have realized in 2000: it wasn’t yet the fall of 2001. From a gut-level perspective, baseball — or anything — in New York would never feel the same after what happened downtown that following September. Knowing that makes me treasure the September and October before 2001 that much more.

As this list of Favorite Seasons stands (which is to say pending what I choose to do with 2024), you will not find any year above 2000’s slot that begins with the number ‘2’ in the Top Ten; it’s all Nineteen Something Something from here on out. I’m suddenly reminded of an early-ish email meme that went around on November 19, 1999, or 11/19/1999. None of us, it was advised, would ever again see “today’s date” expressed in all odd numbers, unless we lived to make 1/1/3111. It’s an intriguing triviality, though probably not one worth hanging around for. As this list of Favorite Seasons stands (which is to say pending what I choose to do with 2024), you will not find any year above 2000’s slot that begins with the number ‘2’ in the Top Ten; it’s all Nineteen Something Something from here on out. I’m suddenly reminded of an early-ish email meme that went around on November 19, 1999, or 11/19/1999. None of us, it was advised, would ever again see “today’s date” expressed in all odd numbers, unless we lived to make 1/1/3111. It’s an intriguing triviality, though probably not one worth hanging around for.

The “failure” of any year after 2000 to crack my Top Ten likely reflects the way a lifetime fan — OK, this lifetime fan — has processed further maturity. In 2000, I was 37 years old. I’d experienced the Mets in the last year of the 1960s, all of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, and now the first year of this new millennium. It might have been a coincidence of the calendar or a matter of the Mets declining in sync with me nearing my forties, that after 2000, nothing about my baseball team was going to impact me the way everything about my baseball team had impacted me already. “Everything I needed to know about being a Mets fan I learned from 1969 to 2000,” doesn’t quite sum it up, but maybe everything I was ever going to feel was never going to seem so revelatory again. Things can still be meaningful. They may not be as influential or formative.

I’m still rooting for the Mets. I’m still writing about the Mets. I’m still relishing the coming of another Mets season. I’m still capable of being uncommonly levitated by the Mets, as demonstrated by the events of not too many months ago. I don’t think everything I’ve been up to with my Mets has been an extended time-killing exercise from 2001 forward. Yet perhaps the belief that everything you’re experiencing has never transpired quite like this before can happen only in the first century you’re alive, and it takes a hearty sampling of your second century on the scene to confirm it.

Given its immediate era, its hallmark events, and my specific experience, what we used to anticipate as The Year 2000 turned out, in way-of-life terms, to be Peak Mets for me. Implicit in having reached a peak is that it’s inevitably and necessarily — but hopefully gently — downhill from there. Given its immediate era, its hallmark events, and my specific experience, what we used to anticipate as The Year 2000 turned out, in way-of-life terms, to be Peak Mets for me. Implicit in having reached a peak is that it’s inevitably and necessarily — but hopefully gently — downhill from there.

PREVIOUS ‘MY FAVORITE SEASONS’ INSTALLMENTS

Nos. 55-44: Lousy Seasons, Redeeming Features

Nos. 43-34: Lookin’ for the Lights (That Silver Lining)

Nos. 33-23: In the Middling Years

Nos. 22-21: Affection in Anonymity

No. 20: No Shirt, Sherlock

No. 19: Not So Heavy Next Time

No. 18: Honorably Discharged

No. 17: Taken Down in Paradise City

No. 16: Thin Degree of Separation

No. 15: We Good?

No. 14: This Thing Is On

No. 13: One of Those Teams

No. 12: (Weird) Dream Season

No. 11: Hold On for One More Year

by Greg Prince on 8 February 2025 6:28 pm The Mets’ How We Spent Our Winter Vacation essay can be produced in succinct fashion: “We did some signing. We did some trading. We did some retaining.” Given who they signed in December and who they retained in February, that’s a dozen words worthy of a pretty high grade.

Free agents and player swaps are what get the Hot Stove blood flowing, but as we’ve felt in our veins since learning Pete Alonso won’t leave, you can’t sleep on retaining your own when your own have been part of something special.

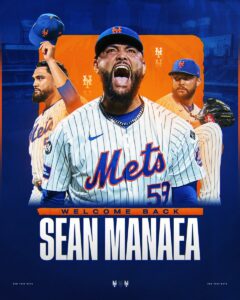

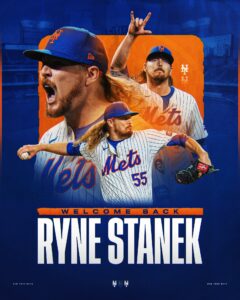

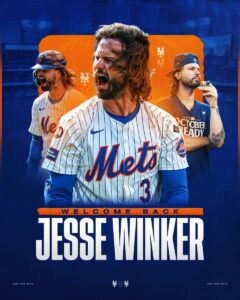

The Retained Polar Bear needs no further reintroduction, but let’s take a moment and appreciate the re-signings of three Mets who wove themselves into 2024’s narrative as the year went on. On the edge of the most recent season, Sean Manaea qualified as a reclamation project; Ryne Stanek was another box on somebody else’s Journeyman Reliever bingo card; and Jesse Winker? We despised that dude!

Now? We recall Manaea as our 2024 rotation ace, Stanek as our 2024 bullpen lifesaver, and Winker? We adore that dude! Still do — all of them. When the Mets re-signed each of them, the images the club posted on social media didn’t just illustrate them in on-field action, but reaction. These guys shouted to the high heavens when they and their teammates succeeded, leading us to our own episodes of frenzy. We don’t want to lose what winning feels like. They were part of one of the most lovable teams of our lifetime, so besides keeping three Mets who we consider good at what they do, we don’t have to let go of too much of that 2024 feeling. Now? We recall Manaea as our 2024 rotation ace, Stanek as our 2024 bullpen lifesaver, and Winker? We adore that dude! Still do — all of them. When the Mets re-signed each of them, the images the club posted on social media didn’t just illustrate them in on-field action, but reaction. These guys shouted to the high heavens when they and their teammates succeeded, leading us to our own episodes of frenzy. We don’t want to lose what winning feels like. They were part of one of the most lovable teams of our lifetime, so besides keeping three Mets who we consider good at what they do, we don’t have to let go of too much of that 2024 feeling.

Had agreement not been reached with Alonso, there would have been many practical reasons to baseball-mourn, but the kick to the emotional gut might have left the deepest mark. A lack of Alonso would have massively changed our connection to what we just did. To a lesser extent, bringing back Manaea, Stanek, and Winker prevents a case of the orange-and-blues. You could take a shot at replicating their statistics through other acquisitions, but were the next starting pitcher, the next setup man, and the next DH-OF going to bring that certain something to Citi? Had agreement not been reached with Alonso, there would have been many practical reasons to baseball-mourn, but the kick to the emotional gut might have left the deepest mark. A lack of Alonso would have massively changed our connection to what we just did. To a lesser extent, bringing back Manaea, Stanek, and Winker prevents a case of the orange-and-blues. You could take a shot at replicating their statistics through other acquisitions, but were the next starting pitcher, the next setup man, and the next DH-OF going to bring that certain something to Citi?

Maybe. But you just don’t know. Really, you just don’t know how personalities and performance will blend from campaign to campaign. In the history of the New York Mets, the years after years that have yielded postseason play have yielded, uniformly, fewer regular-season wins. The second time around is inevitably a challenge. Still, it’s tough to erase the immediate past and write nearly as satisfying a next chapter from scratch. Maybe. But you just don’t know. Really, you just don’t know how personalities and performance will blend from campaign to campaign. In the history of the New York Mets, the years after years that have yielded postseason play have yielded, uniformly, fewer regular-season wins. The second time around is inevitably a challenge. Still, it’s tough to erase the immediate past and write nearly as satisfying a next chapter from scratch.

The Mets didn’t retain Ed Charles for 1970. Try repeating without the poet laureate of 1969. Gil Hodges liked Joe Foy at third base, and Wayne Garrett earned further reps there, too. But it wasn’t the same.

The Mets didn’t retain Kevin Mitchell or Ray Knight for 1987. There was decent rationale within both decisions. Kevin McReynolds was an absolute get when he was got, and Knight’s position, third base, was crowded with potential in the persons of Howard Johnson and Dave Magadan. I understood both transitions. The Mets loomed as stronger on paper going into 1987 than they might have had they tried to run it back with Mitchell and Knight from 1986. But it wasn’t the same.

Not The Same is a tough barrier to overcome from the Mezzanine or Promenade or wherever you’re consuming Mets baseball. Willie Mays retires. Wally Backman is squeezed out to create space for Gregg Jefferies. Todd Zeile isn’t quite John Olerud. Kevin Appier and Steve Trachsel combined aren’t quite Mike Hampton. Moises Alou replaces Cliff Floyd. Neil Walker replaces Daniel Murphy. Bartolo Colon is born to wander to other destinations. Jacob deGrom takes the money and pitches somewhere else (for a few innings, anyway).

The Mets were already tempting fate by unveiling alternate road jerseys that feature the same script they modeled in 1987, the ultimate Not The Same season in franchise lore. You want to send nine players onto the field in shirts that less read as New York than Nope, Not Again. If enough of the players are the guys who did it in the first place — and they’re augmented by a newly signed stud like Soto and assorted other acquisitions (no offense, likes of Griffin Canning and Jose Siri, but everybody’s bound to be “all other” compared to Juan Soto) — you don’t worry so much about Not The Same, because you believe things will be even better. Never mind that only twice has a Met playoff years been succeeded by a different Met playoff year. Spring Training approaches. We’ve got enough of the band back together. We’re here for the enhanced continuity. We’re here for the believing. The Mets were already tempting fate by unveiling alternate road jerseys that feature the same script they modeled in 1987, the ultimate Not The Same season in franchise lore. You want to send nine players onto the field in shirts that less read as New York than Nope, Not Again. If enough of the players are the guys who did it in the first place — and they’re augmented by a newly signed stud like Soto and assorted other acquisitions (no offense, likes of Griffin Canning and Jose Siri, but everybody’s bound to be “all other” compared to Juan Soto) — you don’t worry so much about Not The Same, because you believe things will be even better. Never mind that only twice has a Met playoff years been succeeded by a different Met playoff year. Spring Training approaches. We’ve got enough of the band back together. We’re here for the enhanced continuity. We’re here for the believing.

A fistful of non-incidental 2024 Mets linger on the free agent market. None among J.D. Martinez, Adam Ottavino, my personal favorite Jose Quintana, or the sidelined-early duo of Brooks Raley and Drew Smith has been mentioned as a possibility to return. I wouldn’t dismiss any of them with “good riddance,” but I get it. Teams move on from players and players move on from teams. I shrugged similarly at the news that Luis Severino landed in Sacramento, Harrison Bader in Minneapolis, and DJ Stewart at the confluence where the Allegheny and the Monongahela form the mighty Ohio. Thank you for your service, fellas. Phil Maton might have been referenced once or twice in mid-winter “should we…?” chatter, but the bullpen appears packed if not stacked (that’s an assessment that’s always up for grabs). Besides, it took me a few weeks after their respective arrivals to remember which one was Stanek and which was Maton. Maton was the one I couldn’t picture shouting like Stanek, Winker, Manaea, or most Mets.

The one überMet of 2024 who’s currently unsigned and carries with him the most appealing Sameness is Jose Iglesias. Jose hit .337 against major league pitching and No. 1 on a couple of Latin music charts. Both were pluses in creating the vibe of the 2024 Mets. I don’t have to spell out what OMG meant to us. I also don’t have to list all the second base candidates this team already maintains under contract, but will: an ascendant Luisangel Acuña; a recovering Ronny Mauricio; a possibly versatile Brett Baty; and a previous champion of batting named Jeff McNeil. Iglesias, 36, is older than the lot of them, just like Knight was senior by a far sight to HoJo and Mags coming off his showstopping 1986.

Beyond the hitting that won him Comeback Player of the Year honors and the World Series MVP trophy, the chemistry of that Mets team pulsated through Knight. We kind of knew it when he was here. We definitely knew it when he was gone, regardless that Johnson blossomed into 30-30 territory and Magadan’s swung quite sweetly. Mitchell didn’t put up numbers on the level of McReynolds in 1987, but by 1989, Mitchell was the National League’s Most Valuable Player and, in terms of personality, there was never any confusing the two Kevins. Metrics count so much, but character counts as well. Had Knight and Mitchell remained Mets a year longer, maybe that old script New York on the new blue road togs wouldn’t give me shivers. Beyond the hitting that won him Comeback Player of the Year honors and the World Series MVP trophy, the chemistry of that Mets team pulsated through Knight. We kind of knew it when he was here. We definitely knew it when he was gone, regardless that Johnson blossomed into 30-30 territory and Magadan’s swung quite sweetly. Mitchell didn’t put up numbers on the level of McReynolds in 1987, but by 1989, Mitchell was the National League’s Most Valuable Player and, in terms of personality, there was never any confusing the two Kevins. Metrics count so much, but character counts as well. Had Knight and Mitchell remained Mets a year longer, maybe that old script New York on the new blue road togs wouldn’t give me shivers.

When it comes to ballplayers, you can only keep so much yesterday as you build tomorrow. Some of it you don’t have to think about. For example, the talent and character inhabiting Francisco Lindor figures to fit in any Met year or Met uniform, whereas some ballplayers stock only so much magic in addition to ability from year to year. The OMG secret sauce Jose Iglesias stirred — with pinches of so many Mets included — probably can’t be replicated for a second serving. But, man, don’t you sort of want another taste of what he brought? Or would you rather try some of those fresher ingredients in hope that something more delicious can be created? Days before Pitchers & Catchers, there are no wrong answers.

The idea going into 2025 isn’t to do another 2024, no matter how awesome 2024 was. It’s to come up with something that somehow tops it. You never know what exactly the recipe for what’s better will be.

by Greg Prince on 6 February 2025 12:47 am The long, cold winter brightened and warmed with the word Wednesday night that a Polar Bear will continue to prowl among us for the foreseeable future, which is to say one, maybe two years. Foreseeable may be a stretch. You live in the world today. You’ve ascertained that nobody can see very far into the future. The future is now. Now we know we have Pete Alonso for 2025.

Pete and the Mets are together again without ever having left one another, which is the way it should be. The contract that makes Alonso a Met for sure in ’25 and at his discretion in ’26 will give him lots of money, if not as much money as he would have liked when his free agency commenced. Not as many years, either, but he should consider the savings inherent in staying put. For example, he doesn’t have to invest in a new Hagstrom street atlas to cobble a route to a strange ballpark in a different town. Pete knows the way to Flushing Bay.

Does Pete know the way to Flushing Bay? Apparently so! It’s a great Met move in the short term. The club brought in Juan Soto, which looms as all upside (for this decade, at least), just not as sky high as it could have been until one big question mark was eliminated from the penciling in of lineups. We had Juan. We had Francisco. We had Mark and Brandon and…uh, back up. Weren’t we missing somebody? We were. We won’t miss him anymore.

The Mets’ first baseman remains the Mets’ first baseman. Pete Alonso has filled that position for so long, it might not be easily recalled who last started at first base for the home team before Pete showed up at Citi in 2019. It was Jay Bruce, Closing Day 2018. Jay’s been retired a while. Messing around with Alonso alternatives, even if they distilled down to a relocated Mark Vientos, was going to be a chore. Vientos at first meant “who?” at third. Abbott & Costello didn’t have an obvious answer there, either.

The A&S Boys can start shopping for RBIs ASAP. Instead, we have the A&S Boys, Alonso & Soto, filling the middle of the lineup and their shopping bags with RBIs. We have Lindor and Nimmo, as ever, along with young yet continually maturing Vientos and Alvarez. An array of other bats and gloves will be sorted. Pitchers will pitch. There’s never enough pitching, but that’s what the President of Baseball Operations is for. David Stearns is always seeking and finding help. He helped himself, with the support of Steve Cohen, to slugging first baseman Pete Alonso, he of the 226 Met homers and the ability to hit at least 27 more before he has the opportunity to opt out. That would give the Polar Bear 253 and the franchise record. Of course I won’t want him to take his record and tour the open market anew next winter, but that’s next winter. There’s a Spring directly ahead. There’s a last winter detail taken care of. Are we sure the weather’s that frigid in New York today?

by Jason Fry on 1 February 2025 5:26 pm Oh, it was a fun year. Such a fun year! The fuel light came on and the engine quit a little ways short of the Promised Land, but what a joyride until then! We got 34 new Mets, five of them making their MLB debuts. Some look like pieces of the future, others remind us that the 2024 team took a while to come into focus, and a few you may not remember at all. But isn’t it always that way?

(Background: I have three binders, long ago dubbed The Holy Books by Greg, that contain a baseball card for every Met on the all-time roster. They’re in order of arrival in a big-league game: Tom Seaver is Class of ’67, Mike Piazza is Class of ’98, Francisco Alvarez is Class of ’22, etc. There are extra pages for the rosters of the two World Series winners, the managers, ghosts, and one for the 1961 Expansion Draft. That page begins with Hobie Landrith and ends with the infamous Lee Walls, the only THB resident who didn’t play for the Mets, manage the Mets, or get stuck with the dubious status of Met ghost.)

Welcome lads! (If a player gets a Topps card as a Met, I use it unless it’s a truly horrible — Topps was here a decade before there were Mets, so they get to be the card of record. No Mets card by Topps? Then I look for a minor-league card, a non-Topps Mets card, a Topps non-Mets card, or anything else. That means I spend the season scrutinizing new card sets in hopes of finding a) better cards of established Mets; b) cards to stockpile for prospects who might make the Show; and most importantly c) a card for each new big-league Met. Eventually that yields this column, previous versions of which can be found here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here and here.)

Let’s get to it, shall we?

Harrison Bader: A superlative center-fielder with a question-mark bat, Bader’s shoulder-waggle strut — cocksure to the point of performative, and complemented by those lilac gloves — made me laugh regardless of scoreboard or standings. I loved doing the Bader Walk in our living room after Harrison did something notable and repurposed an old Simpsons bit in his honor, pretending to be the opposing manager: “Look at him strutting around like he’s cock of the walk! Well, let me tell you, HARRISON BADER IS COCK OF NOTHING!” (Not true: He was one of the merry ringleaders of the Zesty Mets.) Bader is a free agent and headed elsewhere; I hope his new city enjoys him as much as we did. 2024 Topps card in which he’s beardless, a giveaway that it’s a Photoshopped image of him as a Yankee. I’m not happy about it either.

Jorge Lopez: A gawky middle reliever, Lopez’s exit from the roster will go down in team lore as a turning point of the season and a key moment in learning about David Stearns and his regime. Which, to paraphrase Absence of Malice, isn’t true … but is accurate. If the details have grown hazy, Lopez pitched pretty well for the season’s first two months, then got shellacked by the Dodgers on May 29 and ejected. His reaction was to fling his glove over the netting, and a postgame interview made things worse: What Lopez meant to say came out a little mangled, but the gist was that the Mets were the worst team in the whole fucking MLB, or Lopez was the worst teammate in the whole fucking MLB, or some combination of the two. Rather than pounce, the beat reporters gave Lopez chances to clarify his remarks, none of which he took. He was DFA’ed the next day with Carlos Mendoza talking about standards. At that point the Mets had lost 15 of 19 and pretty much were the worst team in the WFMLB. But though we didn’t know it yet, the bad times were over and the dizzy, giddy rocket ride that was the rest of the season was about to begin. That’s the story, but if told fairly it’s not that simple. Lopez was clearly struggling with his emotions after the game, which he had a history of — he’d been put on the 15-day IL as a Twin to address mental health. That’s not a disparagement — baseball has evolved and so have we, and we’re all better for it. Lopez also has a son who suffers from a rare disease requiring regular hospital visits and multiple transplants; cruelly, the day of the implosion was his son’s 11th birthday. None of that was a reason for Lopez to keep his job, but it’s context to keep in mind and be kind about. Happily, Lopez was picked up by the Cubs and pitched well; he’ll be a National in 2025. 2022 Topps card as an Oriole.

Michael Tonkin: Greg and I are both fond of Recidivist Mets, players who return to our roster for another go-round. But Tonkin took earning that status to an extreme. The already much-traveled reliever — Twins, Nippon Ham Fighters, Rangers, Brewers, Long Island Ducks (twice), Diamondbacks, Toros de Tijuana, Braves — pitched in three early games, the second a disaster that was scoreless rolling into the 10th but became a 5-0 loss. Tonkin was excused further duty after one more outing, picked up by the Twins and pitched poorly, then returned to duty with the Mets and was last seen hosing out the stables during a 10-0 loss in LA. He became a Yankee, his third organization (fourth if you want to be pedantic) of a season whose calendar hadn’t turned to May. Tonkin pitched pretty well in the Bronx over the summer (though we hung a loss on him), got designated for assignment, and wound up … back with the Twins. I’m sure he found the whole thing as ridiculous as the rest of us did. An old card as a Ham Fighter. Everyone deserves a card as a Ham Fighter!

Luis Severino: I was not a fan of the Mets signing Severino, a Yankee phenom turned medical chart. That had nothing to do with Severino and everything to do with scar tissue from the Wilpon era. Because what was more Wilponian than happy talk that a broken-down pitcher could return to his glory years? And a former Yankee, no less! But Severino wisely didn’t try to return to what had worked in his youth, instead emphasizing his sinker and pairing it with a sweeper. He pitched somewhere between ably and quite well for the Mets, running out of steam in the postseason but with plenty of company in that regard. He then declined a qualifying offer and signed a hefty contract with the A’s. I personally wouldn’t sign up to pitch in a minor-league park for three years, but nobody’s ever offered me $67 million to do anything, so what do I know? 2024 Topps card as a Photoshopped Yankee. Did Topps have time to get an actual shot of Severino as a Met? Yes, but they’re now a monopoly and the quality has gone in the direction any econ professor would tell you to expect when monopolies are tolerated.

Zack Short: Mark Vientos was one of the best stories for the 2024 Mets, but they sure took their time finding their way to the right answer. Short was one of the false starts, a career .174 hitter who parlayed a solid spring training into a spot on the Opening Day roster over Vientos … then went 1 for 9 and was sold to the Red Sox once J.D. Martinez was ready. Short didn’t do anything in Boston and wound up as a Brave, so of course he hit .370 the rest of the way with a pair of walk-off homers against the Mets … oh wait, that’s the paranoia talking. He actually hit .148 for Atlanta, though he did face us in May and scored two runs off walks, but Brandon Nimmo walked off future Met A.J. Minter so all ended well. 2022 Topps card as a Tiger.

Tyrone Taylor: An import from Milwaukee, Taylor doubled with Bader in the defensive center-fielder/fourth outfielder role, which has been a revolving door for years. Taylor stopped the Mets’ season-opening losing streak by walking off the Tigers and his bat heated up down the stretch, making him a starter and Bader an afterthought. His AB in the Francisco Lindor Game was a critical turning point, a Dunstonesque 11-pitch epic that resulted in a double and sent Spencer Schwellenbach to the showers. He’s the first player in this year’s chronicle who’ll be a Met again in 2025. 2024 Topps Card as a Photoshopped Brewer.

Jake Diekman: A red-bearded itinerant reliever who walked too many guys, Diekman arrived having revived his career as a Tampa Bay Ray. That’s generally begging for trouble, as Rays pitcher whispering tends to stop working once exported, and so it was with Diekman, who caused no end of Met-fan agita before getting DFA’ed near the end of July. With one glorious exception: With the Mets clinging to a 3-2 lead over the Yankees, Diekman was entrusted to retire Trent Grisham, Juan Soto and Aaron Judge and secure the save in the Bronx. Which he somehow did, erasing Judge with a fastball on the hands. It was the best pitch of Diekman’s Mets tenure, and if you ever see him out in the wild, you owe him a beer. Topps Heritage card as an Oakland A.

Yohan Ramirez: A new Mets trend is having relievers earn their stripes with the team by exacting vengeance — see Yoan Lopez a couple of years ago against the Cardinals, and Ramirez in 2024 against old friend Rhys Hoskins. Ramirez’s pitch behind Hoskins’ back earned him an ejection and a suspension … and was probably the most effective pitch he delivered in New York. He was an Oriole by Tax Day, made a Tonkinesque return to New York in May and was terrible again, then was terrible for the Dodgers and Red Sox before signing on with the Pirates. Good luck everybody! Old Topps Heritage card as a Mariner.

Sean Manaea: A lefty hurler with Samoan ancestry and an all-West Coast track record, Manaea arrived in New York trying to rebuild his career after the Giants couldn’t decide what to do with him. Pitched pretty well for the Mets in the first half of the season (though he did cut off his fabulous mane), but really caught fire after he watched Chris Sale mowing hitters down with Atlanta and decided, “I could do that.” And indeed he could: Manaea changed his arm slot and his pitch mix and was electric the rest of the way. (Well, almost: Like lots of other Mets, he looked gassed in October against the Dodgers.) Let’s review: Manaea decided to reinvent himself as a pitcher in the middle of a season in which he’d already been successful … and it worked. That’s having balls the size of church bells. He was also a delight as a teammate, pirouetting with Bader in dugouts as part of his elaborate handshake routine, beaming in Instagram photos with Lindor’s kids, and generally spreading joy. He opted out of his contract at year’s end but will return on a new deal, and I’ll be overjoyed to see him. 2024 Topps card, Photoshopped. Oh well, now he’ll get another one.

Joey Wendle: Boy did that not work out. Wendle arrived with expectations that he’d be a perfectly cromulent utility guy but was jaw-droppingly wretched as a Met. First came a muffed play at second base that led to an implosion against the Tigers; then at the end of April he inexplicably tried to start a double play on a 49 MPH grounder to third with a speedster at bat and the tying run 50 feet from home plate. The former was a physical error and so forgivable; the latter was a mental one and so raised the question of what Wendle was doing on the roster. The Mets came to the same conclusion and Wendle was excused further duty two weeks later. 2024 Topps card, a souvenir of a brighter world that never came to be.

Adrian Houser: Arrived with Tyrone Taylor after looking serviceable as a member of the Brewers’ rotation, another move that didn’t work out. Houser was pretty good in his first start but horrible after that, becoming a Tommy Milone 2.0 metronome of suck. He lost his starting job at the beginning of May and was a bit better in the Mike Maddux role of banished long man, but anything short of “spontaneously combusted while signing autographs for orphans” would have counted as “a bit better.” Houser was DFA’ed in late July and last seen posting a 9+ ERA in Triple-A with the Orioles. Got a 2024 Topps Update card, which annoyed me despite being useful for THB purposes, as I never wanted to think about him again.

Julio Teheran: Here’s a difference between the new regime and the Wilpons. The Mets brought in Teheran, a former Braves star derailed by injuries, to pitch against Atlanta on April 8 and he got tattooed. (Though the Mets somehow won that particular barnburner.) The Wilpons would have kept Teheran around until midsummer, ignoring the can’s scratches and dents and the stack of ever-smaller price tags affixed to it and ignoring questions about whether that gross stuff leaking through a rusty seam was safe for human consumption. The Cohen-Stearns regime thanked Teheran for his lone evening of service and sent him off with what I presume was a thoughtful parting gift. Some old Topps Heritage card as an Angel, secured because I refused to admit him to THB as a Brave.

Cole Sulser: Don’t remember a thing about him. The record shows he put up a 9.64 ERA in four appearances, so that’s for the best. 2022 Topps card as a Marlin. It’s a horizontal; I should probably fix that.

Dedniel Nunez: We’ve already been through such familiar roster niches as the late-inning defensive center fielder and the middle relievers with early-spring sell-by dates. Now for a happier one: the unheralded guy who becomes essential. That was Nunez, a lifelong Met farmhand (not counting a season as a Giants Rule 5 pick that he lost entirely to Tommy John) who’d flunked his initial go-round at Triple-A but got the call after looking a lot better in 2024. Nunez quickly became a reliable arm out of the bullpen, which was badly needed given injuries and ineffectiveness. Unfortunately, he was felled by a strained forearm tendon that limited him to one appearance after late July. Imagine if we’d had a healthy, non-gassed Nunez against the Dodgers! But this is missing the point: Imagine bemoaning this what-if back in spring training when only veteran roster hounds had any idea who Nunez was! Anyway, the last update about Nunez was that he’d thrown some bullpens and BP in the Dominican Republic academy, which … doesn’t sound particularly promising. Got a ridiculous two-person 2024 Topps card in which he shares space with Tyler Jay; I scorned it and used an old Syracuse Mets card instead.

Tyler Jay: Jay made his big-league debut a couple of weeks before his 30th birthday, completing an unlikely journey that included being out of baseball due to what was eventually diagnosed as eosinophilic esophagitis, a scary sounding inflammation of the throat. That made for a nice story, complete with Jay’s refreshingly jockspeak-free interview after his debut. His three-letter name looked mildly ridiculous due to Nike fucking up the 2024 uniforms — years from now we’ll see a 2024 highlight and go, “What the fuck is wrong with … oh yeah, that’s right.” Anyway, Jay only pitched twice for the Mets in April and once in July before winding up as a Brewer, but don’t tell him 2024 wasn’t a helluva year. Chattanooga Lookouts card due to the Topps shenanigans decried above.

J.D. Martinez: Have bat, will travel — think of J.D. as a bubble-gum-card Shane. Martinez signed on with the Mets shortly before Opening Day, taking the DH job away from Vientos, and made his debut in late April. His season was a strange one: a superb May and June (including his first-ever walkoff homer, which seems impossible), a meh July and August, a disastrous September and a not bad postseason. That adds up to a rather wan statistical record but misses his other contributions: Martinez was like another hitting coach, praised as a hitting savant by Alonso and others and serving as a key mentor for Vientos. That last part may soon be viewed as having been worth $12 million all by itself. 2024 Topps Update card, the first in THB to show a Met wearing City Connect togs.

Danny Young: Proved at least a marginally useful lefty reliever after Brooks Raley was lost for the season, despite often looking vaguely frightened about the assignment. Young was good at times and not so good at other times, which is to say he was a middle reliever; I never really trusted him but also didn’t recoil in horror when he’d arrive. Not Alex Young, another black-bearded lefty reliever. I wonder if the Mets had them room them together, a la the two Bob Millers … oh who am I kidding, MLB players haven’t had to double up for a generation. 2024 Syracuse Mets card.

Christian Scott: Hailed as the future, Scott pitched reasonably well but was frequently snakebit and never recorded his first big-league win in an abbreviated season that frankly struck me as a little underwhelming. Maybe this is unfair — and if so I’ll gladly admit it when Scott is our ace — but every time I watched Scott pitch, it felt like GKR talked him up like a trio of nervous matchmaking aunts trying to market a basement-dwelling nephew with weird online interests. Scott will have to wait a while to try again for that first win, as his UCL blew out in July and he had Tommy John surgery. He should return in 2026; who knows what he’ll be when he does? 2024 Topps Update card.

Jose Iglesias: OMG! No player better personified the the Mets’ giddy transformation from car wreck to Lamborghini. (I see you with your hand up; for the last time, Grimace doesn’t count as a player.) Iglesias had a dream season, one even more remarkable because it almost didn’t happen. Always known for good hands and superb instincts, Iglesias had spent years as a starter in waiting, signed by clubs as a utility guy and a stabilizing presence and then ascending to a starting role to fill the kind of need that always arises. But by 2023 it looked like that had stopped working: He became a minor-league free agent in June and this time the phone didn’t ring. Iglesias thought about retiring but gave it one more shot with the Mets, where things also didn’t seem to work: He was passed over for a roster spot and convinced not to opt out by Stearns, who promised he’d be the first callup from Syracuse. That came on Memorial Day, with the Mets 10 games under .500; after Iglesias’ arrival the Mets went on a 26-13 tear, reviving their moribund season. Iglesias was a Baez-esque fielding partner for Lindor (witness this late August sprawl-and-kick force against the Padres) and a terror at the plate, particularly in clutch situations. (The highlight: driving in the go-ahead run in the Edwin Diaz restoration game in Arizona, which provided the one-win margin that put us into the playoffs and not them.) Oh, and as Candelita he became a legit pop star, with the bouncy, infectious “OMG” going from clubhouse soundtrack to home-run celebration to the top of the Latin charts and a staple of national-TV Mets footage. Next time an aging slugger continues to erode or a pitching reclamation project doesn’t work out, remember that a utility infielder called up at the end of May once saved our season, ascended to pop stardom and gave us a You Had to Be There on-field concert with his teammates grooving along the first-base line. (Is the best part Pete Alonso’s endearingly awkward vibing, Harrison Bader’s cutoff Mets tee, or both?) Topps gave Iglesias a card in its Living Set, complete with the OMG sign, and this outweighs so many of my other complaints.

Luis Torrens: A wandering backup catcher (honestly that’s redundant), Torrens arrived after the Mets decided they’d seen enough of Omar Narvaez and paid immediate dividends, providing surprisingly potent offense and taming enemy basestealing. The offense didn’t last but the defense did, and Torrens crafted a season highlight by initiating a game-ending 2-3 double play against the Phillies in London. It’s a play I still marvel at months later, one that required baseball instincts and situational awareness and cool under fire: Nick Castellanos dribbled a Drew Smith pitch out in front of home plate, Torrens grabbed it, whirled to find home plate with his foot, whirled back, found a lane connecting himself with Alonso’s glove at first, and made the throw. It’s a play for the top of any catcher’s CV. Topps Heritage card as a Mariner.

Joe Hudson: A backup catcher, Hudson went to London as part of the taxi squad but didn’t get into a game until a couple of weeks later in Chicago, where he caught the 9th inning of a 11-1 Mets win without getting an plate appearance. (The final Cub batter of that game, if you’re curious? Tomas Nido.) The lack of an AB sounds cruel, but it’s a hazard for third catchers, as is never getting into a game at all and becoming a ghost. BTW the Mets had two 2024 ghosts — Matt Gage and postseason phantom Max Kranick — and their all-time ectoplasmic roster now numbers 15. 2024 Syracuse Mets card.

Ben Gamel: A journeyman outfielder known to Stearns from a stint as a Brewer, Gamel spent a month and a half on the roster, mostly as a defensive replacement late in games, and did nothing particularly praiseworthy or blameworthy. 2024 Syracuse Mets card; he has not one but two unique cards from Topps team sets, which were expensive and annoying to track down. This isn’t Gamel’s fault but I’m still a little ticked.

Ty Adcock: Former Mariner pitched well in his first appearance as Met, less well in his second appearance, then got bombed in his third. There wasn’t a fourth appearance. Some old card as an Arkansas Traveler.

Matt Festa: Made his Mets debut in the 11th inning of a 5-5 tie against the Astros; when he left it was 10-5 Astros. Thus did Festa’s Mets tenure begin and end. Ouch. An old Topps Total card as a Mariner.

Eric Orze: A hulking righty (is there any other kind of righty reliever these days?), Orze had spent the last couple of years at Syracuse, often discussed for a callup but never getting one. He finally got his chance in July against the Pirates and it didn’t go well: a walk and two singles, followed by watching glumly from the dugout as Adrian Houser got obliterated and put more runs onto Orze’s ledger. Orze reduced his ERA from infinity a couple of weeks later mopping up against the Braves, but that was it. He was sent to Tampa Bay in the trade for Jose Siri and will now undoubtedly become a highly useful reliever. (Speaking of which, did you know Edwin Uceta and Tyson Miller emerged as reliable bullpen arms elsewhere this year?) Syracuse Mets card.

Phil Maton: Arrived from Tampa Bay at the trade deadline and stabilized the relief corps, though his needle looked like it was on E come the postseason. Maton’s utter lack of affect went from amusing to mildly worrying over time; in the early days I thought “Phil Maton sure is admirably stoic” but later that became “I hope digging under Phil Maton’s porch wouldn’t lead to a horrifying discovery.” Has never had a Topps card, which feels like a mild injustice; in THB he’s an El Paso Chihuahua. I did the best I could, Phil, so please don’t put me under the porch.

Alex Young: Not Danny Young! Pitched pretty effectively down the stretch, but mostly in low-leverage situations, was left off the postseason roster and non-tendered after the season, and will return to the Reds in 2025. Here’s where I put the annual reminder that there are 1,450+ innings in a big-league season and it takes a lot of arms to get through them. (In last year’s THB this reminder was basically the entirety of Reed Garrett’s entry, so you never know what the future holds.) Old Topps Heritage card as a Diamondback.

Ryne Stanek: Looked terrible after arriving at the trade deadline, but righted the ship and was invaluable down the stretch and in the postseason, and will return in 2025. In addition to pitching well, Stanek taught me a valuable baseball lesson; I can’t find it, but somewhere he talked about the things he’d been working on as a pitcher with help from the coaching staff, and how poor results didn’t necessarily mean progress wasn’t being made. That was a point about patience and process that resonated with me; so was this Stanek line about the hazards of long ABs, from the perspective of the guy on the mound: “You only have so many tricks. It makes the at-bat substantially harder when you’ve exposed everything you’ve got.” Topps Heritage card as an Astro.

Jesse Winker: Before he became a Met at the trade deadline, I would have said — albeit with no particular heat — that Jesse Winker was an asshole. Which is not wrong, from a blinkered perspective that misses the point entirely. In fact Jesse Winker is a kayfabe asshole, who understands that there’s a home team and an opposing team and being on the opposing team means you’re the enemy, so you may as well embrace that role and play to the crowd. And why not? Baseball may be humanity’s highest art form but it’s also goofy theater, and far better when all involved have fun with it. I found it interesting that the Mets were delighted beyond the usual collective-endeavor sentiments to add Winker as a teammate, and that the Citi Field crowd quickly embraced him as well, recategorizing his antics as a long-ago Reds villain according to the philosophy sketched out above. Winker’s season highlight was walking off the Orioles and kicking off one of the more epic home-run celebrations in recent memory, complete with an awesome opening spike of the batting helmet. Brian McCann probably had an embolism watching the clip from the sidelines of some tedious golf course, but too bad: Baseball’s way more fun without all the grim frowny gatekeeping. Topps Now card celebrating the above.

Huascar Brazoban: Another trade-deadline acquisition, Brazoban was 34 but seemed a lot younger, his butterflies forming a visible cloud when he was on the mound. (Think of him as the antimatter Phil Maton.) He was the center of a notable moment in San Diego, saucer-eyed and clearly out of sorts as a decent-sized Met lead became smaller and smaller. Which led to Francisco Lindor clapping madly and exhorting Brazoban to bear down and Francisco Alvarez removing his helmet to bark at him from behind the plate. (By the way, when Alvarez came into this world Brazoban was 12 years old.) Brazoban somehow got the last out and his teammates surrounded him on the mound like they’d all won the World Series; while it wasn’t a moment to make me want to invest in Huascar Brazoban futures, it was also kind of sweet. Some card in which he’s a Jacksonville Jumbo Shrimp.

Paul Blackburn: A cromulent fifth-starter type, Blackburn was rescued from the A’s at the trade deadline and made five starts — three good, two bad — before taking a line drive off the hand. While rehabbing he developed back woes, which turned out to be a leak of cerebrospinal fluid. That sounds terrifying but apparently isn’t as severe as … no, fuck it, that sounds terrifying. Mysteriously got a 2024 Topps Chrome Update card as a Met.

Pablo Reyes: A club’s last few season debuts usually reflect tinkering at the margins of the roster: subbing out a gassed middle reliever, adding a third catcher, or upgrading a utility infielder/fourth outfielder. The Mets needed to fill the dual role of utility guy/speedy pinch-runner and couldn’t seem to decide how best to do that. Their first choice was Reyes, who entered Sept. 1’s game against the White Sox as a pinch-runner, scored five pitches later on a Starling Marte double, and so concluded his Mets career. Somewhere Dave Liddell is smiling. 2024 Topps card as a Red Sock.

Eddy Alvarez: Plan B in Operation Find a September Utility Guy was Alvarez, so far the most notable winner of an Olympic silver medal for speed skating to suit up for the New York Mets. Alvarez played capable defense though he never recorded a hit, ending the year 0 for 9. Strange but true: He wound up with more strikeouts as a Mets pitcher than hits as a Mets batter, somehow fanning poor Weston Wilson during a scoreless ninth that ended a horrific loss against the Phillies. That’s worth a Faith & Fear bronze at least. Old Topps Heritage card as a Marlin.

Luisangel Acuna: “Baby Acuna” (at least that was his name in our house) was summoned when Lindor’s back acted up and he turned out to be a godsend: solid in the field, more pop than we’d anticipated, and a certain unquantifiable electricity that was a welcome September jolt. Beware small sample sizes (that performance came after an up-and-down year with Syracuse) and keep in mind that Acuna is just 22, but the future looks bright. Impress your friends with the factoid that the Acunas’ father, Ronald Sr., was a Mets farmhand and a teammate of David Wright’s. A terrible Syracuse Mets card; Acuna will get something better soon.

by Greg Prince on 28 January 2025 7:21 pm Seven players have stolen exactly 17 bases in the course of their New York Mets tenure. Only one within that highly specific cohort has been exceedingly efficient as a basestealer. In fact, that player can claim the third-highest stolen base percentage of any Met who has stolen at least 17 bases as a Met. Yet that very same player, who has been caught stealing only TWICE amid six seasons of daily play, can be judged as leaning a little too far toward second these days and may very well be setting himself to get picked off first. One is tempted to ask, where’s the first base coach? Why isn’t he telling this runner to not stray more than a couple of steps from the bag we instinctively think of as his?

Because it is January, there is no blaming Antoan Richardson. His kind of coaching isn’t in effect prior to Spring Training. Still, somebody should be going over the signs with our baserunner and giving him the advice that will ensure he stays where he oughta. Regardless of the rule changes of a couple of years ago, somebody’s gonna throw over and somebody’s going to nudge him from the base that’s became his long ago.

The Mets held an event called Amazin’ Day on Saturday. Long ago, its existence would have been considered amazing. Other teams held fanfests. Other ownerships saw the benefits. The folks who used to own the Mets didn’t until the very end of their tenure. Then came a pandemic and a sale. Momentum must have been slow to put the pieces of a winter confab together again, because after 2020, there was no sign of one at Citi Field. This year, five years since the previous iteration, the Mets held one. The present ownership not only signed off on it but planted itself at the center of the story on the minds of Mets fans in attendance and following along via social media.

Steve Cohen was on a panel…let’s just pause and reflect on that alone. The people who owned the Mets before Steve and Alex Cohen kept as low a profile as possible when they sensed people who love the Mets were nearby. Not Steve. Not Alex. They show up. They pose for pictures. They open up about pressing issues when asked.

Steve was asked, by panel emcee Gary Cohen, about the “elephant in the room,” the pending contractual status of free agent Pete Alonso. “The Polar Bear in the room” would have been the preferred framing, but you can’t script everything. Whatever species was invoked, the question had to be posed. The fans were chanting “We Want Pete” at Steve, David Stearns and Carlos Mendoza. The fans who paid to get into a ballpark two-plus months before any ballgames wanted Pete’s power and Pete’s presence. Pete’s 17 steals in 19 lifetime regular season attempts (along with two of two in the 2024 postseason) might not have been on anybody’s mind, though value added is value added. A Polar Bear who picks his spots on the basepaths is unusual, never mind the spot — on the outside looking in — where this Polar Bear has found himself this winter.

October basestealer casts a shadow as February nears. If Steve Cohen were more of a showman, a curtain would have parted and revealed the object of the crowd’s affections. Maybe he’d even be wearing a Polar Bear costume, shedding it along with the uncertainty regarding his future professional residence. Pen would be put to paper and Pete Alonso, Met for life (or at least a few more years), would have elevated the vibes from immaculate to unimpeachable. There’d be nothing Steve Cohen could do wrong.

Instead, Steve was the Steve we’ve sort of come to know since he and Alex replaced Fred and Jeff Wilpon in the fall of 2020. He was candid, telling Mets fans not exactly all they wanted to hear, but telling it in a fashion that could be interpreted as like it is. It was Steve’s version.

The offer the Mets made to bring Pete back?

“Significant.”

The response from Team Alonso, which is to say Scott Boras, an agent the name of whom we only sometimes wish we knew?

“I don’t like the structures that are being presented back to us. It’s highly asymmetric against us.”

Chances for resolution?

“I will never say no. There’s always the possibility. but the reality is, we’re moving forward. As we continue to bring in players, the reality is it becomes harder to fit Pete into what is a very expensive group of players that we already have.”

Steve’s version, whether it was a snapshot of the drying-Polaroid ilk or something more permanent — beat hearsay and speculation. It’s wild the owner spoke so openly. Neither Wilpon would have done it in such circumstances. Nor would have a Doubleday, de Roulet or Payson. Still, Steve’s version won’t be Scott’s version, and Pete’s version will be Pete’s. Ultimately, he’s the holder of the pen, the person who will have to consent to what’s on the paper, whatever its contents, wherever it’s offered for his signature.

Our version is wanting a first baseman who makes some plays that don’t seem makeable on grounders in the hole and throws in the dirt, a slugger who delivers 34 home runs in what’s viewed as an off year, a clutch performer who verified his status in the most do-or-die baseball situation imaginable, a literal lineup constant, a homegrown star who burrowed into our collective heart as a rookie and never left, and a certifiable sports icon in a town where becoming and remaining one ain’t that easy. Dude also steals a few bases a year and almost never gets caught; I’d be shocked if Boras hasn’t worked his client’s 89.5% success rate into his contract pitch.

Still, nobody’s irreplaceable on a roster. Get a guy with those credentials, and maybe we won’t miss Pete Alonso on the New York Mets. Got another of him handy?

Amazin’ Day also featured a slew of current and past Mets on hand to bring January joy to the shivering faithful. No free agents still out there for the taking were on the program. Thus, while fans could line up for autographs of and photographs with those inked in as 2025 Mets, Alonso wasn’t in the building, except as conversation odder. Someday he’ll be eligible to be feted under the heading of Met Alumni, but it’s too soon for that designation. We’d rather none among MLB’s array of Met opponents scoop him up, either. February’s knocking. Negotiations really need to resolve. Pete’s been nabbed stealing second twice, but he’s never been picked off first. I can’t bear to think about what that would look like, even if we’ve been braced for the idea that it might happen.

Oh, in case you’re wondering, the other players with exactly 17 career stolen bases as Mets are Rod Kanehl, Claudell Washington, Keith Hernandez (so fond of his uniform number, he was also caught stealing 17 times), Butch Huskey, Timo Perez, and current free agent nobody’s talking about bringing back Harrison Bader. The only two Mets who stole at least 17 bases and yielded a better rate than 17 safe! and 2 out! were Chico Walker (21 SB, 1 CS, 95.5 SB%) and Jason Bay (26 SB, 2 CS, 92.9 SB%). What each of these gentlemen of otherwise diverse skill sets has in common is that none of them will be 2025 Mets. Here’s hoping the same won’t have to be said of Pete Alonso.

by Greg Prince on 22 January 2025 6:25 pm Let’s head into the backyard of our childhood and dream. Let’s take a ball and go into our windup. Let’s pretend that we are registering the out that wins our team something of substance. We are the champions…of the world! We win the pennant! The division! We’ll accept a postseason berth or a playoff series, because those inspire dogpiles on the mound and champagne showers in the clubhouse. It’s the stuff that baseball fans’ dreams are made of from the time it occurs to us to mimic what we see the big leaguers do.

Twenty-four times the Mets have won something of surpassing substance: eleven playoff spots (six of them NL East titles); one Wild Card Series; five Division Series; five National League championships; two World Championships. Once, one of these — the 1999 NLDS — was earned on a Met home run, an ending a kid in a backyard likely dreamed up as well. The other twenty-three times, a pitcher threw the ball that, whether taken, swung past or hit to a fielder, became that glorious last out. The second it is secured in a mitt, the Mets are transformed, and so are we. We are in. We have moved on. We have won what there is to be won and we are in the best mood we can inhabit. We have definitely reached a level not reached every day.

Every day? The New York Mets have played 10,077 games since April 11, 1962, regular season and postseason combined. Twenty-four have been cause for sustained teamwide celebration. So if you’ve thrown a pitch to uncork one or more of those joyous jamborees, you deserve a little something for your efforts.

For Billy Wagner, a Hall of Fame plaque will do nicely.

Billy isn’t going to Cooperstown only because he flied the Marlins’ Josh Willingham to Cliff Floyd in left at Shea Stadium on September 18, 2006, and he induced L.A. pinch-hitter Ramon Martinez to foul out to right fielder Shawn Green at Dodger Stadium on October 7, 2006. But when his plaque is unveiled this July and the “NEW YORK, N.L., 2006–2009” line jumps out at us, those two pitches ought to fill our consciousness and inspire us to clap or whoop or whatever we did when Floyd and Green cradled what Wagner threw.

Takin’ care of business. As noted, we don’t get those situations every day, let alone every year. When Billy was called upon to pitch the ninth in the prospective division clincher in 2006, it was the first time in six years a Met was tasked with putting the Mets in the playoffs. The same time span stood in terms of the Mets advancing within a postseason when he got the ball to finish off the Division Series. In neither case was Wagner credited with a save, as the leads he protected were four runs apiece. Yet the manager, Willie Randolph, had Billy Wagner in his bullpen and high-end sparkling wine on ice. Who else was he going to call?

When Billy, lately of the Phillies, hit the open market after the 2005 season, he made all the sense in the world as a Met target. The 2005 Mets were pretty darn good. Flushing eyes focused on approaching greatness. As dominant a closer as the National League had experienced for the previous decade was available. The Mets needed somebody in that role. They went for the best they could get their hands on.

Oh, those 2006 Mets. They were beautiful for many reasons. One of them was surely Billy Wagner, he of 38 saves built on a strikeout rate of 11.7 per nine innings. Any nine Wagner innings would be accumulated over approximately nine games, but they were almost always critical and they were mostly completed successfully. A few stand out as having gone awry. Just a few. They stand out because that’s how we’ve conditioned ourselves to process closers.

Wagner closed out the division and the Division Series. It was a small sample size compared to all the sizzling Hall credentials he established as an Astro between 1995 and 2003 before he split for Philadelphia, and they were merely two appearances in the scheme of 189, regular and post, as a Met. An injury stopped him cold just as the 2008 playoff chase was heating up in earnest. That was his second consecutive All-Star season as a Met, his third as a top-of-mind presence in our thinking. When your team is competing for real and you have a closer you depend on, you think about that man and his operative arm a lot. Billy Wagner was our guy and his left wing was our weapon of choice in those do-or-die spots in 2006, 2007 and 2008. A lot of coming through. A little of shall we say not so much, but only a little. “No regrets” won’t appear on his plaque regarding NEW YORK, N.L., 2006–2009, but we can read between the lines.

Billy’s comeback from injury didn’t return him to the Mets until the summer of 2009 was already a lost cause. He got loose long enough to make himself attractive in trade to Boston, where it was thought he might help push the Red Sox to October (he didn’t). He then found a landing spot in Atlanta, where it was thought he could help the Braves return to October in 2010 (he did). Sixteen seasons finishing games in lights-out fashion, then turning out the lights on his own career before he could appreciably decline. Four-hundred twenty-two saves, still a Top Ten ranking for all of baseball history. Ninth innings upon ninth innings when it appeared he couldn’t be touched and wasn’t. Implosions on occasion, but they were the exception. Fella who wanted the ball and wanted to win in ways that transcended the notion that all pitchers want to pitch and want to win. You can feel it more with some closers than others. You felt it like crazy with this closer.

Now Billy Wagner’s the sixteenth player who played for the Mets who goes into the Hall of Fame as a player, the sixth such pitcher, the first recognized as a reliever. We recognized him coming in twice to get us a couple of the final outs we allow ourselves to dream of. He got them for us. Good for him getting this.

by Greg Prince on 3 January 2025 1:57 pm If you’re harboring a dormant grudge against the Astros for whatever reason — and there are plenty of reasons…

• The Colt .45s getting out to a much better start in life than the Original Mets

• The infliction of carpeted indoor baseball upon the Grand Old Game

• 1969’s inexplicable yearlong flogging (the garden-variety Astros took ten of twelve from the Miracle Mets)

• Cooter’s

• Mike Scott’s sandpaper fetish

• Roger Clemens’s hero’s homecoming

• Abandonment of the National League, a poor-taste maneuver that also stuck us with Interleague baseball on a daily basis

• “What’s that sound? I think it’s coming from somewhere off the home team dugout. It’s like somebody’s beating on a trash can.”

• Not disposing of the Braves in the 2021 World Series

…there’s a reason to activate it.

The new year has arrived and the Houston Astros STILL have “TBD” listed as the start time for all their home games. Normally, I wouldn’t care. I wouldn’t even check. Except the Mets will be commencing their upcoming season at Houston’s renamed Daikin Park on March 27, and I need to know the first-pitch time so I can calculate with dead-on balls accuracy the coming of the Baseball Equinox.

The Baseball Equinox, revealed in this space every offseason since 2005 was becoming 2006, is that moment in time when we as Mets fans are equidistant between the final out of the previous Met season and the first pitch of the next Met season. It is the dot in our existence that tells us last year is last year and next year is a veritable heartbeat away.

I do know that the 2024 Mets ceased being a going concern at exactly 11:23 PM Eastern Daylight Time on October 20, 2024, when Francisco Alvarez was retired on a 4-3 groundout to end the National League Championship Series. But I don’t know what the Astros have in mind for a first pitch on March 27, 2025. Almost every other team in the major leagues has set its start time. But not the White Sox (who presumably continue to dig out from their 2024 debris, so they can be forgiven) and not the Astros. I realize there are a lot of “Minute Maid Park” signs to replace, and that onerous task must be preoccupying a slew of busy Houstonians, but you’d figure these people would be practiced at renaming their facility, having had to rip “Enron” off the walls early in this century and get that juice caboose up and running above left field.

No, I don’t know why the Astros are not on the ball schedulewise, but the Equinox clock ticks away sans proper coordinates louder than any bat can thwack a wastebasket, so a decision must be made, one I am reluctant to go with, but I feel I have no choice.

I must approximate.

In weather forecasting, there are Astronomical seasons and Meteorological seasons. They don’t seem to be named for Astros and Mets, as they are the opposite of what’s going on right now. Astronomical is the exact season, involving those solstices you hear so much about on or around the 21st of December or June. Meteorological is probably more practical. Meteorological Winter, for example, starts December 1, which sounds about right, as there’s nothing autumnal about December. Meteorological Summer starts June 1, which doesn’t sound right if your elementary school didn’t let out until the third Friday of June, but we get it. June is summer. December is winter.

The Baseball Equinox is exact, except this year. We’re going to be Meteorological about it and go with what makes the most sense.

Fellow Mets fans of all ages, we may observe with confidence the Baseball Equinox at 7:10 PM Eastern Standard Time on January 7, 2025. It could be off by a few minutes or a couple of hours when we factor in the most likely actual first-pitch times based on precedent and best guesses, but the important thing is a) it’s close enough; and b) it’s 7:10 PM. You’ve likely already begun to feel a twitch in your remote-operating thumb every night at 7:10. You might as well indulge it this coming Tuesday night.

Welcome to almost next year. It’s still too cold out and we still don’t have all the information we need, but we’ve waited long enough for a real hint of Mets baseball.

by Greg Prince on 31 December 2024 2:47 pm  Author’s baby picture, before author discovered shirts and pants. So I’m born on the last day of 1962, the same year the Mets came into this world, and now it’s 62 years later, and I’ve turned 62. This feels a bit like a Mets fan’s Logan’s Run endgame.

Yet I will go out on a limb and predict there’s more to come in the year the Mets reach their 63rd birthday and that I’ll keep rooting for them and writing about them, if never quite enough for my satisfaction. I end every year with stories not yet fully pursued and wonder why the hell I didn’t pick up the pace and take up the chase.

But that’s what next year is for, right?

Thank you for 2024 at Faith and Fear. The Mets part turned out something close to great on the field, but it wouldn’t have been the same without you here.

by Greg Prince on 30 December 2024 3:23 pm I have two favorite stealth statistics from the 2024 season.

1) When the Mets bottomed out at 22-33 on May 29, everybody in the National League, save for the Rockies and Marlins, had a better record than them: the three division leaders, the three Wild Card holders of the moment, and six teams with what appeared to be more reasonable playoff aspirations. A glance at those standings could have easily persuaded a Mets fan to find something better to do with his time in the summer ahead. But a slightly closer examination would have indicated that, despite the pileup atop his favorite club’s head, the Mets were a mere six games behind whoever tentatively claimed the third Wild Card with 107 games to go. Certainly there was a lot of traffic to navigate, but six games in practically two-thirds of a season could be made up, couldn’t it?

2) When Edwin Diaz gave up his second death-blow home run in three games on August 28, the 69-64 Mets sat four games from the third and final Wild Card spot, which represented a tough but doable climb toward October; six games from the second Wild Card spot, by definition a little harder go; and seven games from the team then possessing the top Wild Card spot, which was really asking for trouble — a seven-game deficit with 29 contests remaining. For comparison’s sake, the 1973 Mets, surely our most frequently cited example of a bunch that wasn’t out of it until they were out of it, lagged 6½ games from where they hoped to land when they still had 29 games to play. Yet when all was said and done divisionally in ’73, the Mets — who’d been in sixth/last place on August 30 — made up eight games on the first-place Cardinals in just over a month and qualified for the postseason as the NL East champions on October 1. They were never out of it.