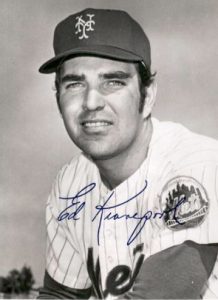

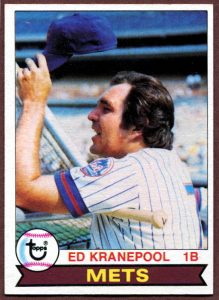

Ed Kranepool has passed away at the age of 79, though I don’t see how that’s possible. I’ve always considered Eddie Kranepool the closest thing there was to immortal our world. He was with us from just about the very beginning, and, as far as I was concerned, he was going to be around forever. I guess he will be, in our Met hearts and Met minds. I brought up his name on a podcast last week. I brought him up to my companion at the game yesterday. This is par for the Krane course. Nobody who rooted for the Mets from 1962 to 1979 will forget the high school phenom; the bonus baby; the young comer; the struggling major leaguer; the world champion platoon first baseman; the personification of professional renaissance; or the pinch-hitter deluxe. Every ring around the Mets’ tree had his signature carved within. Stopping playing didn’t erase the spot he held in our consciousness. I have a feeling it will grow only stronger.

From our 2020 series “A Met for All Seasons,” it is my privilege to share with you the last article we posted. Fittingly, Ed was our finale (representing 1979), because when it comes to a Met and all seasons, who the hell could possibly have followed Eddie Kranepool?

***

I’ve been alive forever

And I wrote the very first song

—Barry Manilow

Jeurys Familia (2012-2018, 2019- ) won’t still be relieving for the Mets in 2029. Jacob deGrom (2014- ) won’t still be starting for the Mets in 2031. Michael Conforto (2015- ) won’t still be driving in runs for the Mets in 2032. Brandon Nimmo (2016- ) won’t still be getting on base by any means necessary for the Mets in 2033. Dom Smith (2017- ) won’t still be pounding out doubles for the Mets in 2034. Jeff McNeil (2018- ) won’t still be pinging from position to position for the Mets in 2035. Pete Alonso (2019- ) won’t still be blasting homers for the Mets in 2036. Andrés Giménez (2020- ) won’t still be making plays in the hole for the Mets in 2037.

And if they are, they won’t be doing whatever they’re still doing for another year besides.

Steadiest Eddie.

So let’s salute as unbreakable a Mets record as exists: Ed Kranepool’s 18 seasons as a Met, spanning 1962 to 1979. Nobody else has come close to playing so long for us, let alone playing so long for us and nobody else. It is highly unlikely anybody else will ever play more. Longevity. Continuity. Exclusivity. The combination is not to be underestimated, because the combination crafted by Kranepool has never been equaled.

• Cure David Wright (2004-2016, 2018) of his spinal stenosis and let him play his entire contract, through 2020, without pause. He might make the Hall of Fame, but he comes up a year short of Ed Kranepool as a Met.

• Fix the left elbow of John Franco (1990-2001, 2003-2004) without time away for Tommy John surgery and then keep him around instead of letting him slip off to Houston for his final innings. He comes up two years short of Ed Kranepool as a Met.

• Same for fantasy-version, never-leaves, therefore in theory never-gets-in-trouble so we never have reason to stop loving him Jose Reyes (2003-2011, 2016-2018). Uninterrupted Reyes comes up two years short of Ed Kranepool as a Met.

• What if Buddy Harrelson (1965-1977) never left instead of spending two years with Philly and one in Texas? Still not enough. When Buddy was coaching in 1982 and the Mets were suddenly short of infielders, there was some chatter that the 38-year-old former Gold Glover might have to be activated. Add that hypothetical to the other hypothetical and still nope. Harrelson comes up two years short of Ed Kranepool as a Met.

• Straighter and narrower paths for Darryl Strawberry (1983-1990) and Doc Gooden (1984-1994) that carry them respectively to the ends of their careers (1999 and 2000, respectively) in Flushing? Like Wright, each man still winds up a year short of Ed Kranepool as a Met.

• Maybe if Tom Seaver’s restoration in 1983, intended to eradicate that he was forced to abdicate following his initial 1967-1977 reign, isn’t botched in 1984, and he stays at Shea all the way to 1987, which was when he officially retired…that’s sixteen seasons as a Met and it’s also STILL not enough to measure up to Ed Kranepool as a Met.

And if you’re a New York Met who’s beyond the reach of even Tom Freakin’ Seaver, then, brother, you must be doin’ somethin’ Amazin’.

You can attempt to delete ifs and buts from the story of every Met who isn’t Eddie Kranepool, but they’ve all got ifs and buts. For example, if the Mets never traded Jerry Koosman, he conceivably could have played all nineteen of his seasons with the Mets (and maybe been A Met for All Seasons), but then we don’t get Jesse Orosco and we can’t say for sure who would’ve gotten the second last out of a World Series in Mets history.

No, no buts about Eddie Kranepool. No ifs, either. Ed Kranepool showed up early and stayed as late as he possibly could. He put in 18 seasons; 18 seasons in a row; and 18 seasons in a row as a Met only.

Edward Emil Kranepool in a taxi, honey.

Nobody’s had a Met career like Kranepool’s, except Kranepool. Nobody’s been a Met like Kranepool, except Kranepool. Nobody’s been the Mets like Kranepool, except Kranepool. That was the case in 1962, in 1979, in all the seasons in between and, as the four-plus decades since he played have illustrated, forever after. Projections are dangerous to make without the data to back it up, but I feel comfortable declaring nobody else ever will be a Met like Kranepool, except Kranepool.

That’s the beauty. That he’s still Ed Kranepool and there’s still no catching him or matching him let alone the possibility of hatching him, or a reasonable facsimile thereof. There’s exactly one Ed Kranepool. Nobody else has one of him because there is only one of him. Baseball-Reference lists “similarity scores” for every player with decently measurable major league tenure (100 IP; 500 AB), so while you can certainly find statistical comps for Ed Kranepool if so inclined, I don’t believe any other baseball franchise has so deeply embroidered within the fabric of their story any figure quite like him.

Ed Kranepool is of the New York Mets.

The New York Mets are of Ed Kranepool.

He’s ours, dammit.

***Ed Kranepool, we have determined, has the Most Seasons record cold. Most games played, too, with 1,858, topping Wright by more than a full season-and-a-half’s worth. According to

Baseball Musings, nobody’s played in more Met losses than Eddie: 1,102, which will come with the territory of anybody whose 18 Met seasons, partial and full, encompassed eight last-place finishes. Krane is second in wins, however, with 746 (with five ties thrown in for middling measure). Befitting a man of his experience, he dots Top Fives and Top Tens all over the Met charts.

He earned his spots in the upper levels of Mets compilation categories by hanging in there. It is no insult to say Ed Kranepool’s best quality as a player was sticking around and sticking around some more. That and arriving in the big leagues sooner than any Met ever had or ever will. The latter is technically unknowable, but give us a shout when you come across another Met not yet old enough to vote.

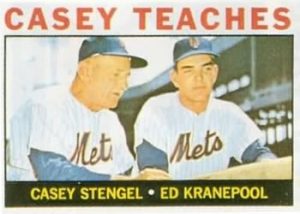

The Youth of America gets some private tutoring.

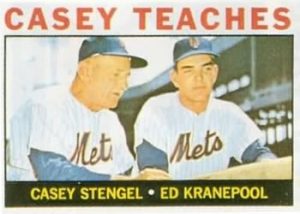

Eddie was only 17, no older than ABBA’s Dancing Queen, when he made his major league debut, which makes sense only when you realize the Mets weren’t yet six months old themselves and how is an infant franchise supposed to know you don’t put a 17-year-old in the big leagues unless it’s World War II or you’re nurturing the next Mel Ott? They signed Ed in late June shortly after his high school graduation and ten days after Marv Throneberry failed to touch two-thirds of the necessary bases to secure what he thought was a triple. So yeah, the baby Mets were in the market for a first baseman of the future practically right away. At James Monroe High School in the Bronx, Ed broke records established generations before by a fella named Hank Greenberg. He was a heavily scouted, hot enough property in those pre-draft days to elicit a bonus of $85,000, a lofty figure for 1962.

Ed chose the Mets because he deduced advancement on a ballclub in dire need of help would come quickly. Yet the Mets didn’t rush him to the majors right away. No, they waited until September. Then they give him just a taste. The fans, too. They needed something to savor en route to 40-120, something that would tell them the future had some promise in it. Kranepool relieved Gil Hodges on defense on September 22. He got his first base hit a day later in what was supposed to be the final game the Mets would ever play in the Polo Grounds. The following April, Shea Stadium wasn’t ready, so the Mets were back in Manhattan. So was Eddie, though he probably wasn’t ready, either. How could he be? He was only 18. A productive Spring Training had lured Casey Stengel into insisting on Krane’s inclusion on 1963’s Opening Day roster, but the minors beckoned by July.

In 1964, at 19, Eddie was an established big leaguer, though one seemingly final detour to Triple-A at least provided him a story to tell again and again (as if being schooled by Stengel while wet behind the ears wasn’t enough of a conversation piece). After slumping during Shea’s first weeks, he tore up Buffalo, earning a promotion in late May. He played in a doubleheader for the Bisons on a Saturday in Syracuse and schlepped to Queens for a doubleheader the next afternoon. That one, against the Giants, went 32 innings in toto, and Eddie played all of it. Had the May 31 nightcap lasted just a little longer, Krane likes to mention, he would have been playing in another month.

“When are we gonna be ready?”

The Mets’ youth movement was planting its seeds during Kranepool’s first years, and it was reasonable to assume he was on the verge of sprouting. In recent times, when prodigy Bryce Harper was breaking in to rave reviews, and later when Juan Soto was doing the same but even more spectacularly, their ascent up the ranks of the all-time teenager home run list was duly noted. You know whose name continued to show up prominently in such historical accountings? Yeah, Ed Kranepool’s. His 12 home runs before the age of 20 slot him eighth among all teens in baseball history. Admittedly, there’s not a ton of competition, given that relatively few players see the majors before their twenties, but among those who did, Eddie showed more power than most of them. Krane is one behind his boyhood idol Mickey Mantle, one ahead of Robin Yount. Mantle and Yount are in the Hall of Fame. (It only seems like Soto already is, too.)

Eddie was at least, after turning twenty the previous November, an All-Star in 1965. The Mets were on their way to losing more than a hundred games for the fourth consecutive season, so this was one of those situations in which there was a Met All-Star because the rules said there had to be, but Eddie was posting very respectable numbers, batting over .300 through mid-June and hitting .287 once he joined the likes of Mays, Aaron and Clemente at Metropolitan Stadium in Bloomington. Ed didn’t play, as the NL won without his contributions, but they certainly didn’t ask him to vacate the premises.

It would be misleading to play the AMFAS Young Player Peaked™ card here, because it’s hard to say a good first half in ’65 and a little pop while still getting proofed if he requested a Rheingold amounted to a peak. There were some good signs for Kranepool, but what Ol’ Case had said in the first part of his famous “in ten years…” line wasn’t quite coming to fruition. You know the bit. Stengel, in what turned out to be his final Spring Training as skipper, was telling reporters about two representatives of his Youth of America. This young feller, he more or less said of Ed Kranepool, is twenty, and in ten years has a chance to be a star. This other young feller, he said of Greg Goossen, is twenty, and in ten years has a chance to be thirty.

The joke is usually on Goossen, and perhaps Stengel, but Kranepool, at twenty, was done being an All-Star. His final 1965 numbers sagged. Once he stopped being a teenager, his home run totals ceased to appear impressive. Once he turned 21, he’d never again play in as many as 150 games in a season. Once he turned 23, he’d never again play in as many as 130 games in a season. It was somewhere around this time that the realization set in that the first amateur the Mets ever signed to much fanfare was never going to set the world on fire as a professional the way scouts thought he might when he was in high school just a few years earlier.

Or as the banner a not particularly satisfied customer brandished not very deep into the young man’s career asked, “IS ED KRANEPOOL OVER THE HILL?”

Ed Kranepool got old before his time, but only in context. When the Mets traded Jim Hickman to the Dodgers following the 1966 season, that left Ed as the only player from 1962 on the club. Those who weren’t particular about specifics would, for the rest of his Met days, refer to him as the last of the Original Mets. It was a misnomer. The Original Mets were the 28 men who broke camp in April. They included Hickman, Hodges and the first/righty Bob Miller. Legend notwithstanding, Marvelous Marv was not an Original Met. Nor were Choo Choo Coleman, the second/lefty Bob Miller or Harry Chiti, who was traded for himself. Eddie was the 45th of 45 men to play as a 1962 Met. In the popular imagination, they’re all lumped together as the lovable losers of legend. Ed played in two defeats and just three games overall that first year. There’d be plenty of losses to which he’d serve as accomplice in ’63 (starting with Opening Day, when Stengel assigned him to right field), but pinning the L of the first year on Kranepool’s forehead isn’t wholly accurate or remotely fair.

But, like with the doubleheader for Buffalo the day before the doubleheader at Shea before May turned to June, it made for a better story to point to Eddie as someone who’d been around forever. Hence, the 1967 yearbook referred to the 22-year-old as “The Dean”. It was funny because it was true. Ed was the only Met who’d been around since at least the end of the beginning. By ’67, with Ron Hunt having departed in the same trade that dispatched Hickman, he was also the only Met left from when Shea was brand, spanking new. Kranepool was only nine days older than Seaver, yet had a five-season and better than a 500-game head start on the good-looking rookie righty who would turn heads like no Met before him. Casey had given way to Wes Westrum. Stengel’s Youth of America had only taken hold in fits and starts. Seaver was the harbinger of the next era. It wasn’t quite in Queens in ’67, but if Seaver was here, it couldn’t be far off.

Kranepool was here, too. He kind of came with the place.

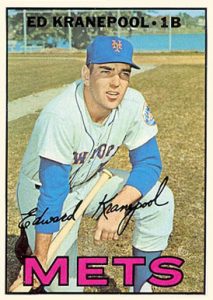

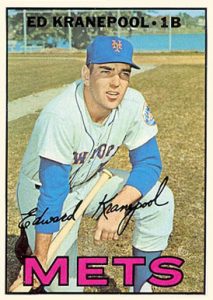

***Growing up, I never thought of Ed Kranepool as a bad player. I never thought of Ed Kranepool as a good player. I just thought Ed Kranepool was a Met. I had never known the Mets without him. Unless you latched onto the Mets when they debuted on April 11, 1962, and then walked away in disgust before June was over

(“how could Throneberry miss first AND

second?”), nobody had ever experienced the Mets without Ed on their radar if not in their box score. My first exposure to Eddie was on a Topps 1967 baseball card, one of the I don’t know how many dozens that fell into my possession once my sister tired of accumulating them. He’s kneeling in what’s supposed to be an on-deck circle, except it doesn’t appear to be marked as such. He’s just kneeling, somewhere on grass in St. Petersburg. Not that I understood the niceties of baseball card photography when I first got a look at

ED KRANEPOOL • 1B or had any conception how long he had been around relative to his teammates or his franchise when I first got my hands on it. I just knew the

METS, as the pink-purple lettering identified his employer, were my local team, so I probably wanted to mark this card as special.

This is the version without the beard.

At four, maybe five years old, I took a blue Bic pen and drew a beard on Ed Kranepool’s face. I didn’t do that to anybody on any other card from any other team or, come to think of it, any other Met. Maybe I felt an instinctive connection to the Met who’d outlasted all of his previous peers to date. Maybe I was just in the mood to draw a beard on a face. Either way, I can’t recall further evidence of personal affinity for Ed Kranepool. Like I said, he kind of came with the place, simply a fact of Met life, like Shea Stadium, or Kiner’s Korner, or rallies that fell a run short in the ninth.

Gil Hodges must have thought something similar. The kid he said goodbye to in May of 1963 when he retired from playing to take up managing in Washington was still a Met five years later when Gil returned to take the Flushing reins. Lord knows the reins needed him. The Mets had never lost fewer than 95 games, never finished higher than ninth out of ten, and they only reached that height once. By the time Gil came back, Ed “had been around long enough,” Leonard Koppett wrote, “to be seen as disappointing, not the pure promise [he] had been.”

Did Gil Hodges need Ed Kranepool? He didn’t lean on The Dean nearly as much as Stengel and Westrum had, starting him less in 1968 than his predecessors had every year since 1964. It’s no coincidence that Hodges elevated the Mets to a point where they won more often and didn’t fret about losing their lovability. Their standing didn’t exceed ninth, but all contemporary observations agree that this ninth was light years removed from the tenths of yore. The losses (89) continued to outweigh the wins (73), but the chronic ineptitude that took root in ’62 was being professionally removed. Some of that lingering Youth of America was indeed in bloom, but it’s also universally agreed that it was the tending Hodges did that accelerated the growth.

It’s probably a coincidence that the reduction in Kranepool’s playing time occurred in the first season that suggested the Mets were capable of truly getting their act together. Ed’s production tumbled in 1968, even taking into consideration that this was The Year of the Pitcher. Under Hodges, playing time would have to be earned by all Mets, with bonus-baby pedigree serving as no kind of determining factor.

***Ed Kranepool was batting .227 entering play on July 8, 1969, and was mired in a 5-for-53 slump. Nonetheless, Gil Hodges started him and batted him sixth that afternoon against one of the best righthanders in the National League, Ferguson Jenkins. It was, to that moment, the biggest game the Mets were ever scheduled to play in their eight-season existence, really the first big game they’d ever played. The first three months of the season had been a revelation. Instead of falling through the floor, they rose in the standings and, with the halfway mark at hand, they were in second place, seriously challenging the NL East-leading Chicago Cubs for first. The difference between the two teams was five games, unless you counted perceptions. The Cubs were star-laden successors to the Cardinals as smart-money favorites to breeze away with the pennant.

The Mets, no matter that they were well over .500 and actually looking down on multiple teams rather than peering up at everybody, were still the Mets. C’mon, let’s get serious.

That was a challenge the Mets were up for. Their fans, too, 55,096 of whom came to play on a day like no other at Shea. They were stoked to root the Mets over the Cubs as loud as they could. They loved these guys who were blowing by mere respectability and indeed getting serious about first place.

One guy, though, would have to earn it a little more than the others.

At 1:58 PM, according to the tick-tock chronicled in The Year the Mets Lost Last Place, “Jack Lightcap, the Met announcer delivers the starting lineups over the public address system. The crowd greets every Met name with wild cheers, every name except that of the starting first baseman, Ed Kranepool.”

Ed was the Met around whom the Mets as a whole had been chronologically built. His growing pains ensued in full view of those who loved their team but hated that they were so terribly lousy. The sour residue of those years had centered itself on one of 25 Mets in a year when every Met name should have been greeted with wild cheers. “Kranepool,” Dick Schaap and Paul Zimmerman posited, “was young only in chronology, not in manner. He ran like an eighty-year-old man catching a commuter train. His modest ability to hit became even more modest with men on base.”

Krane’s start in ’69 had been good for a while, though this, too, was to form, according to the authors. “[E]very now and then,” they wrote, “Kranepool showed flashes of the brilliance that had been expected of him. For a few weeks, usually at the start of the season, he would hit over .300, and Met fans, starved for a hero, would rally to him. But then Kranepool would start slipping toward his own level […] and the fans would abandon him.” On June 15, with Eddie’s latest seemingly inevitable slump beginning to gather downhill steam, GM Johnny Murphy traded for another first baseman, veteran Donn Clendenon. Clendenon, a righty, settled into a platoon with Kranepool, a lefty. In the week prior to the Cub series, Donn had driven in eleven runs. Donn was linked only to these good new days. Ed went back to what he himself referred to as “a seven-year losing streak”.

Prepare to dine like a champ.

No wonder, then, that if Mets fans had to not respond positively to any Met, perhaps as an exercise in figuratively pinching themselves that everything couldn’t possibly going so well, they had their object of derision all picked out. Eight Mets in July 8’s starting lineup are celebrated as soon as Lightcap announces them. “Kranepool’s name,” Schaap and Zimmerman noted, “inspires a chorus of boos.”

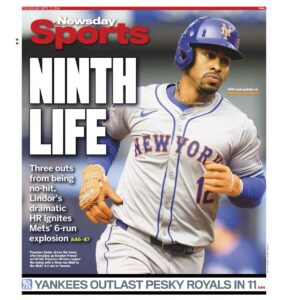

But that was before the game, before the fifth, when, with no runs on the board, Kranepool swung and sent a Jenkins slider over the right field wall. Nobody was booing now. And by the ninth, when the Mets were rallying from a 3-1 deficit, there was no time for ancient recriminations. Everything is happening in the now. Ken Boswell leads off with a fly ball Cubs center fielder Don Young can’t find. It lands as a double. With one out, Clendenon comes off the bench to pinch-hit, the beauty of having two capable first basemen on the roster. He hits one very deep to left-center. Young tracks it down but can’t hold it. It’s another double, though because it took its time not being caught, Boswell has to advance with caution, and he runs only to third.

That’s OK, because Cleon Jones, way up in the batting race, hits one to deep left to score both Ken and Donn. Cleon, a .352 hitter, lands at second. It’s the Mets’ third double of the inning. It’s 1969, and in 1969, managers like Leo Durocher stick with aces like Ferguson Jenkins. Durocher instructs Jenkins to intentionally walk Art Shamsky. The strategy works provisionally as Wayne Garrett grounds to second, leaving runners on second and third for the next batter.

The next batter is Ed Kranepool. Durocher can have him walked, too, so Jenkins can face J.C. Martin. But, are you kidding? Leo’s not worried about any Ed Kranepool.

Maybe he should’ve been, because Eddie makes contact with a one-and-two pitch and bloops it into left field. It falls in for a single. Jones dashes home. The Mets have won, 4-3. The Mets have picked up ground on the Cubs. The Mets are serious contenders. The fans are jubilant, and Eddie has made them so. Ed Kranepool is now batting .232, and he’s going to wind up 1969 batting only .238, but he’s quite clearly having the best season of his life. “I used to get so tired of losing,” he said. “It made the days so long and the nights so unpleasant.”

These were better days. The best two, from a Krane’s perspective, came on October 14, when the Met who’d seen it all since 1962 hit a home run in the World Series, and October 16, when the team he’d played for since 1962 won the World Series. Clendenon, Series MVP, and Kranepool combined for four dingers in the five games.

***For the rest of Ed Kranepool’s life, he was a 1969 Met, with a 1969 World Series ring, hard-earned and hard-won. In every public reunion of the world champs, Ed would be as front and center as any of them. The “…since 1962” part was trivia now. The trials and tribulations of a bonus baby who didn’t live up to the hype, who was labeled intermittently as “bitter” or “lazy” was dusty backstory. Eddie beat the Cubs. Eddie beat the Orioles. Eddie, along with his teammates who sung about it on

The Ed Sullivan Show, had heart.

Ed Kranepool was now a world champion — a 1969 World Champion New York Met. Nobody could take that away from him. The journey from the basement to the penthouse was complete. With the possible exception of Ed Charles, whose professional baseball career commenced in 1952; was stymied for a decade by institutional racism; and then got bogged down by colorless losing in Kansas City, nobody in a Mets uniform could have appreciated this new reality more than the Krane.

Except the Glider really could call his journey complete. His career ended with Game Five of the World Series (whether he wanted it to or not was another matter). Charles was 36. Kranepool was 24. Though he’d worked as a stockbroker in the offseason and might have thrived in business had he followed that path, he was a ballplayer first and foremost. He had a lot more ball to play.

After 1969, it couldn’t help but be kind of a downer to have to live up to what he’d just been a part of. It showed, not only in his performance but his demeanor. For all the youth he’d embodied, Ed never evinced a sense of ebullience. Maybe he didn’t feel a reason to. He never knew his father, who’d been killed in World War II. He’d been pushed to compete in the top tier of baseball before he was ready. The fans were preternaturally impatient. The reporters always had questions (and occasionally had digs). The manager expected improvement, championship ring or not.

For a spell in 1970, Ed Kranepool went to a place he’d rightfully assumed he was done with, save for annual exhibitions. He was sent to the minors. The erstwhile All-Star, the man who belted a home run in the previous October’s World Series, was batting .118. He was also 25. Not old. Not baseball old, even. It wouldn’t have seemed all that strange if all you knew was age and average and didn’t know the name and what he’d done last summer and fall.

But this was Ed Kranepool, who’d been a Met since 1962 and hadn’t been a minor leaguer since 1964. It was a shock to the system, both that of Mets fans and The Dean. Ed went to Tidewater, hit .310 and returned. The Mets hadn’t thrived in his absence, failing to defend their championship, but Ed was better in the long haul for his visit to Triple-A. Starting in 1971, Ed wasn’t just a young veteran ballplayer, but a reliable young veteran ballplayer. The average soared to .280. The OPS+, for the first time in his career, rose above 100, indicating he was more than a replacement-level player. Not that anybody had that stat handy in ’71, but he’d transitioned to the latter half of his career in style. Gil Hodges’s expectations were being met.

Ed’s speed demanded In Action cards portray him standing his ground.

Alas, Gil would be gone before Opening Day 1972, a victim of a fatal heart attack. It was a blow to the entire organization. Nobody likely felt it any more than his fellow first baseman from 1962, the youngster the manager had pushed to mature. “He learned to respect me,” Ed reflected to his SABR biographer Tara Krieger in 2008, “and I learned to respect him.”

The Mets’ next manager, Yogi Berra, who also had played briefly with Kranepool, was a mellower figure. He inherited a club whose offense was bolstered heading into ’72, with trades for Jim Fregosi and Rusty Staub. One of those swaps worked out better than the others — and they were supplemented by another deal for Ed’s former All-Star teammate Willie Mays — but the season, like the two seasons preceding it, were no better than 83-win wonders. They were good enough for third place, which after 1969 wasn’t very good at all.

Then came 1973, and a division captured on 82 wins (maybe that had been the problem from ’70 through ’72 — the Mets were winning one game too many). Eddie was a decidedly part-time player as he reached his late twenties. Clendenon had moved on, but John Milner’s power eventually made him the first baseman more days than not. With the Hammer supplanting the Krane, Ed took more reps in the outfield than he had at any time in a decade. It paid off in the fifth and final game of the NLCS. Staub was out with a sore shoulder, so Berra had to improvise. Eddie started in left, with Cleon in right. Kranepool drove in the Mets’ first two runs in the first, then took a seat so Mays could pinch-hit and drive in another in the fifth. Four innings after that, the Mets had their and Eddie’s second pennant.

***The Mets didn’t win the World Series in 1973, and Ed Kranepool never got close to another postseason once Oakland beat New York in seven games. His legacy, however, was about to be embellished. For Mets fans coming of rooting age in the middle and late ’70s, stories of Kranepool’s shortcomings sounded as if they’d been excavated from the ruins of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It may have happened, but we didn’t really understand. Eddie Kranepool, to us, wasn’t a bonus baby who never delivered on his promise. He was ED-DEE Kranepool who delivered big-time when called upon, two syllables at a time.

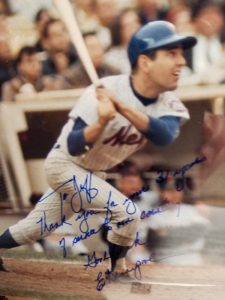

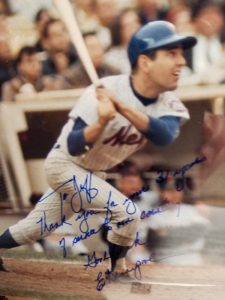

A Mets fan’s view of Ed Kranepool really depended on when one tuned into his long-running show. Getting hooked on the Mets by 1974 got you the Eddie you couldn’t fathom was once considered unpopular. To those of us who were too young to have grasped the 1960s in real time, this Eddie Kranepool, who arose in the wake of his roommate Tug McGraw’s cry of YOU GOTTA BELIEVE, even overshadows the Eddie Kranepool who shows off his 1969 World Series ring. In the 1960s, I was drawing beards on his baseball card. In the 1970s, I was wrapping rubber bands around my Ed Kranepools and storing them safely in a shoe box. I even had him on my closet door — not a card, but an autographed photo. Ed had come to my sixth-grade class one day when I was absent to hand them out. I don’t know how I always managed to be absent for the cool shit, but I was. The story I was told the next day was our teacher was friends with him, so why wouldn’t Ed Kranepool visit Lindell School without notice? Miss Goldstein was kind enough to put aside a picture for me, writing “Greg” on the border. It was almost like it was personalized.

How was I absent for this?

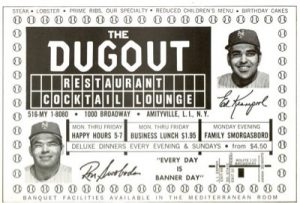

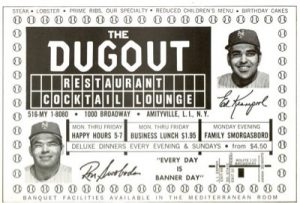

While this was an out-of-the-ordinary occurrence, somehow I wasn’t that surprised that Ed Kranepool would visit a random classroom on a random weekday sans warning. Ed and Ron Swoboda had run a restaurant on Long Island. He lived here year-round. Getting the opportunity to meet Ed Kranepool (unless you were dumb enough to be out with a cold or something) seemed to come with the territory, like what Wayne Campbell said on Wayne’s World about Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours. A copy of the album was issued to every kid in the suburbs.

Eddie, I’m sure, got a nice hand from a roomful of kids. How nice, I couldn’t say. He was beloved without exactly being lovable, though one must concede love is a matter of taste. Drop by Kranepool’s Ultimate Mets Database fan memories page and you’ll be overwhelmed by how many of the Metsian persuasion pledge eternal allegiance to Eddie — and be more than a little taken aback by those who would be fine if a sinkhole opened up and swallowed him.

Ah, Mets fans.

Generally, familiarity bred affection. Getting really good at something didn’t hurt, either. Ed Kranepool’s 18 seasons yielded 4.3 wins above replacement, per Baseball-Reference. That’s negligible, marginal, insignificant if you didn’t put the number to the name. But the name was Ed Kranepool, and had we known about WAR then, we wouldn’t have cared, because there was one thing Ed Kranepool was, in fact, really good at. Besides sticking around, I mean.

Ed Kranepool became the world’s greatest pinch-hitter this side of Manny Mota. From 1974 to 1977, he batted .447 (42-for-94) in the role that suited him to a tee. In his first pinch-hitting appearance of 1978, he homered off Stan Bahnsen of the Expos to win the game, the first and only walkoff home run of his career. Sometimes he was so good at pinch-hitting, his managers got carried away and pushed him off the bench and into the starting lineup. It was the bench’s loss. For a couple of years, he was pretty close to a regular again and better than ever at it. In his early thirties, he was an approximation of what he was supposed to have been all along. In 1976, he pinch-hit only ten times because Joe Frazier started him more than 100 games, the most votes of confidence Ed had received since Hodges began to fully “respect” him in 1971. In 1975, Ed hit .323 after making Metsopotamia rub its eyes in disbelief by lifting his average above .400 in early June. There was talk of a write-in campaign to make him an All-Star for a second time (it didn’t get anywhere). Poet Bob McKenty was so inspired by the Krane’s surge that he channeled his amazement in verse for the Times:

Although his bat knows no fatigue,

Eddie Kranepool is unique:

The only man in either league

To bat .400 twice a week.

Throughout this second or third phase of his renaissance, Ed Kranepool wore an expression of a man just getting comfortable with being accepted for who he is. The residual gawkiness of the teen and preternatural grumpiness of the dismissed was still in evidence, but this was the Krane. The bird with whom he was homophonically linked is described as large, long-legged and an opportunistic feeder. Some are said to not migrate at all and keep to themselves.

The Krane was indeed a rare bird, native to the meadows of Flushing.

Sounds about right. As Leonard Koppett reflected as the flight of the Krane entered what turned out to be its loftiest elevation in 1974, “He didn’t appreciate being the butt of all those jokes in the early days, felt that he hadn’t been given as many opportunities to play regularly as he had earned. He didn’t hold grudges, and he appreciated his responsibilities in a public relations sense, but he was not what one would call a warm personality.”

Nevertheless, Ed Kranepool is who we got as Mets fans, and who we as Mets fans got, even if Ed Kranepool didn’t always seemed thrilled to be Ed Kranepool. He’d smile for the camera if the situation demanded it, but otherwise seemed a little shall we say circumspect about the whole thing — Joe Pesci’s description of the white-haired gent in his mother’s painting in Goodfellas comes to mind: “And this guy’s saying, ‘whaddaya want from me?’”

It’s worth remembering that when a pennant wasn’t being chased, Eddie was essentially just another guy going to work in the same job he had for a long time back when most ballplayers weren’t compensated lavishly and weren’t above replacement. He often seemed unhappy with his situation, maybe with his co-workers, surely with his employers. You stay in the same job for 18 years and not sound surly now and then. Except nobody with a notepad or microphone is likely to ask you what you’re thinking at the end of a bad day or unsatisfying year.

Yet he seemed to smile for the cameras a little more as the years went by. He starred in his very own Gillette Foamy commercial, implicitly attributing the upturn in his fortunes since 1971 not to extra swings in the cage but the shaving cream he was enthusiastically apportioning across his face. When Newsday carriers were encouraged, in the summer of 1977, to convince more of their neighbors to sign up as subscribers, the bait the paper offered us to hustle and sell was a ticket to see the Mets one night real soon, specifically “Mets stars Henderson and Kranepool”. Henderson was the new kid, Steve, from Cincinnati. We all knew Kranepool. We might not have thought of him as a star, but with Seaver and Kingman traded, and Koosman and Matlack struggling, we got it.

I never did sign up any new subscribers (other than my parents), but I would have taken a ticket to Newsday Night at Shea Stadium to see Ed Kranepool. Starting, pinch-hitting, shaving…didn’t matter. ED-DEE could do it all.

***On December 8, 1978, the Mets traded Jerry Koosman to Minnesota for minor league pitcher Greg Field and a player to be named later, leaving only one 1969 Met to be a 1979 Met. Ed Kranepool got to Shea before every one of his world champion teammates and he outlasted them, too. The Dean had extended his tenure to a record-breaking 18th season. He was

The Fantasticks, running Off-Broadway since the early ’60s, with no closing date in sight. His peers had been Throneberry and Coleman and the two Bob Millers at the beginning, then the men who made a couple of miracles. Now he was part of a unit whose headliners were named Mazzilli, Stearns, Swan and the darling of the

Newsday carrier set, Henderson. Every Met who’d been on an active roster from late September 1962 to late September 1979 had something in common: they had all been Ed Kranepool’s workplace proximity acquaintances. There were close to 300 men who qualified, almost everybody who’d ever been a Met.

That didn’t include Harry Chiti. He’d been traded for himself before Ed got called up.

One of the best ever in a pinch.

The late-career magic Kranepool’s bat packed began to wear off in ’78, by which time the long days and unpleasant nights of losing were again entrenched at Shea. The newest iteration of the Youth of America was given the bulk of the playing time by Joe Torre. First baseman Willie Montañez was an RBI machine, so starting the Krane to to keep him sharp became impractical. Ed’s pinch-hitting could still be lethal (15-for-50) but his rare opportunities in the lineup went for naught (2-for-30). Keeping a 33-year-old part-timer fresh was hardly Torre’s priority. When Ed came up in 1962, there was nobody as young as Kranepool. When he headed into 1979, there was nobody in the clubhouse who could possibly relate to all of his baseball life experiences. The 18-year-veteran appeared to be, in the immortal customer-service advice of Rodney Dangerfield, all alone here.

Except on July 14, the highlight of the 63-99 1979 season in a campaign almost entirely devoid of them. It was Old Timers Day at Shea Stadium. The festivities centered on the tenth anniversary of the 1969 Mets. The bulk of them were retired from baseball already. The handful who weren’t were playing for other teams. Seaver was a Red, Koosman a Twin, Nolan Ryan still an Angel long after the Fregosi trade proved less than optimal. Most of those who no longer had a ballgame to play every Saturday showed up at Shea.

One 1969 Met didn’t have to make a special trip. For one afternoon, during pregame ceremonies, Ed Kranepool didn’t have to be a 1979 Met. He could line up with the Mets with whom he identified most closely. He could even break out into a grin when joined in the introductions by perhaps the most famous ’69er of the moment, Chico Escuela, a.k.a. Garrett Morris. Morris had broken through with his “baseball been berry, berry good to me” catchphrase on Saturday Night Live months before. It was uncommonly hip of the 1979 Mets to invite him to reprise his role — that of a 1969 Mets utility infielder — among the authentic alumni. Ed had already gone along with the joke enough to appear in a filmed bit on Weekend Update in which Kranepool had to express dismay with Chico’s new tell-all book, Bad Stuff ’Bout the Mets. Ed was a natural at expressing dismay.

Tom Seaver: “Always take up two parking places.”

Yogi Berra: “Berry, berry bad card player.”

Ed Kranepool: “Borrow Chico’s soap and never give it back.”

Ed stayed in character and shook his head that Chico was stabbing the guys in the back with his revelations. What the hell, it wasn’t like the 1979 Mets were doing any kind of a 1969 impression.

***When the old champs scattered to their post-baseball lives and Ed Kranepool was left to continue in his long-running role, it had to be acknowledged that Eddie hadn’t only been the last of the Met-hicans from 1969 to stay at Shea, he was having a pretty damn long major league career. Those guys who tipped their mesh caps as old-timers in July (the Mets were so cheap in those days) were more or less the same age as Ed. Yet most of them were done. Ed got better at baseball as he went along. True, he was in the denouement phase of his ED-DEE peak by 1979, destined to bat only .232 in his final season, but you didn’t see Jones or Agee or Swoboda or Shamsky still being asked to pinch-hit at a ballpark near you. We’ll say it again: Eddie knew how to stick around.

Except for one night in August when, against the Astros, he left the field before the game was over. To be fair, he thought the game was over. See, the Mets were leading the Astros, 5-0, and starter Pete Falcone had induced Jeffrey Leonard to fly to center with two out in the ninth, so that seemed to end it. Except Frank Taveras had called time at short, which meant Leonard got to swing again, and he used it to single…except this time it was noticed the Mets didn’t have their full complement of nine at their positions because Kranepool, figuring the game was already in the books, had vamoosed to the clubhouse, and…well, let’s just say you don’t come up with the 1962 Mets without somewhere in your soul still being a 1962 Met. The bottom line was an Astro protest was upheld and they had to finish the game the next afternoon (no harm done, except to Falcone’s complete game).

In 1979, an 18-year feast of base hits and dependability was about to end.

It would be too much to read into one confusing episode and infer Eddie was trying to tell us, “Hello, I must be going.” Nevertheless, on September 30, 1979, anybody who was watching or listening to the Mets and Cards from St. Louis was about to witness something that seemed unimaginable across the history of the Metropolitan Baseball Club of New York.

It was Ed Kranepool’s last game. Torre sent him up to pinch-hit for John Pacella in the seventh. Eddie produced a double, his 1,418th base hit, which remained the Met standard until David Wright passed him in 2012, and his 90th career pinch-hit, still a franchise record (and 31st all-time in the major leagues). The manager just as quickly removed him for pinch-runner Gil Flores.

That was it. The Ed Kranepool Era was over.

Well, the part where he played for the Mets, that is. When you’re talking Mets, I don’t think the Ed Kranepool Era ever ends.

***Ed Kranepool’s three-year contract expired after the 1979 season. Management was not interested in negotiating a new one. Maybe Ed could have shopped his services to the American League, where the designated hitter was embraced rather than scorned. A man over 35 could get regular swings over there without having to worry about playing the sport the way it’s designed. But the Krane was definitely not a migratory bird. He’d lived all his life in New York, whether it was the Bronx or on Long Island. Free agency opportunities notwithstanding, he wasn’t about to take flight.

Kranepool knew, as everybody did, that the Mets were going to be sold. They were scraping bottom in the standings and drawing ants (flies couldn’t be bothered), but they were still, on paper, a National League jewel in the largest market baseball had. Maybe a new GM would be interested in Kranepool. Better yet, maybe Kranepool could be in on hiring the new GM. Eddie, whose business acumen was a bigger part of skill set than foot speed, tried to put a group together. He was serious. It made the papers. But, ultimately, the group led by Nelson Doubleday and Fred Wilpon bought the Mets. Ed Kranepool didn’t. In 1980, for the first time since there’d been Mets, a Mets season would proceed without Ed Kranepool in uniform.

When the 2020 season was on hold and I had no new games to watch, I checked YouTube to see if anybody had uploaded episodes of my favorite TV drama from when Ed Kranepool was winding down as a player. To my delight, somebody had. The entire series of Lou Grant, which initially ran from 1977 to 1982, was available for my viewing, and I viewed the hell out of it, all 120 episodes. I mention this because a recurring baseball player character was introduced as a love interest for reporter Billie Newman during Season Three, a backup catcher named Ted McCovey, no relation to Willie. Ted isn’t old for a regular person, but he’s not a regular person. He’s a ballplayer and he’s just been placed on irrevocable waivers. Ted tries to explain to Billie what this all means:

You know what baseball’s done for me? Treated me like a kid for the past fourteen years, and now, suddenly, they’re telling me I’m an old man.

I don’t get the sense that’s something Ed Kranepool would have said when the Mets told him his services were no longer required, but I have to imagine he thought some unscripted unsentimental version of it. Ed was their golden boy. He grew up with them. He’d literally spent half his life answering to chants of ED-DEE, maybe tuning out the less flattering remarks that came with it. When Ed Kranepool played his last game, he was fewer than six weeks shy of 35. Not old for a regular person. Not close to old. Not even the oldest Met of his final season (Jose Cardenal was almost 36).

But too old to play for the Mets anymore, which must have been very strange.

***About as great an Internet find as

Lou Grant for me was a reprint of a magazine article from the defunct

New York Sports, which lives on in pixels thanks to our friends at Metsmerized Online. It’s an article from 1984, breathed back to life by MMO in 2012, written by Len Albin. It’s called “

Ed Kranepool Never Got a Day”. At the time, Ed was feeling underappreciated by Mets management not so many years after he hung up his spikes. His 1,858 games, his 1,418 hits, his 18 seasons cut little ice with an ownership more concerned with trying to make people forget the recent past than celebrating more distant glories. These Mets were just getting good at being in the present. It might have been too much to demand their executives pay proper homage to the past.

Yeah, but this was Ed Kranepool, No. 7 from 1965 forward (and No. 21 for a couple of years before that). This was Ed Kranepool when David Wright was a toddler, Eddie’s records not close to being threatened. They hadn’t given him anything approaching what he — or anybody who’d been a Mets fan more than five minutes — considered his due. No ceremony, no acknowledgement, no nothin’.

“I don’t feel an allegiance to the Mets anymore,” Kranepool told Albin, even as he dressed up in his c. 1978 uniform top and posed Lou Gehrig-style in an empty Shea, addressing the fans who weren’t there for the day he had yet to get. “Loyalty went out the window the day they didn’t sign me.”

Did Eddie mean it? Probably. And probably not. And were the Mets that blithe toward the man who as much as anybody epitomized who they’d been for almost their first two decades? Probably. But probably not. The Mets still had enough of a rearview mirror to gather Old Timers annually in the ’80s. Under Frank Cashen, they inaugurated a Hall of Fame in 1981. True, they hid the commemorative busts in the lobby to the Diamond Club where few were bound to bump into them, and they tended to not announce the ceremonies with sufficient advance notice to draw a large crowd, but they were, in their own less than fantastic way, trying to remember the kinds of Septembers like 1969 and 1973…even a little 1962 sometimes, if not any 1979.

On September 1, 1990, before the Mets took on the Giants in front of more than 40,000 fans, Ed Kranepool got his day. He became the fifth player inducted into the Mets Hall of Fame, the fourteenth member overall. Now he was a world champion, a two-time pennant-winner and recognized by the only organization with which he’d ever been associated as immortal.

The Ed Kranepool story was, at last, complete.

***Only kidding. The Ed Kranepool story was not complete. How could it be? His era is eternal, and the people who owned the Mets were who they were.

In the winter of 2017-18, despite Eddie’s many trips back to Shea Stadium and Citi Field for commemorative occasions, we learned Kranepool was sore at Jeff Wilpon. (Why should he have been any different from the rest of us?) An article, which ran in the New York Times, described Eddie on the outs with the entity that coronated him as a Hall of Famer. Not only that, but Eddie needed a kidney. He was selling much of his baseball memorabilia, not because he needed to, he said, but because it was time.

Amends were made in the summer of 2018, with the then-COO of the Mets reaching out and bringing back Eddie for a first pitch. Of greater import, the Krane got word in the spring of 2019 that a kidney donor with a match for his needs had been found. He was in greatly improved health and spirits by late June, when the 50th anniversary of the 1969 Mets was being toasted by a full house at Citi Field. Tom Seaver couldn’t be there because dementia had sidelined him from public appearances. Too many teammates were no longer with us, but whoever could be there came. Still, without Tom, somebody would have to speak for the group after they were all introduced. That was Seaver’s role at the 40th anniversary. It was always Seaver’s role.

Who better to speak for the 1969 Mets?

At the 50th, it was Kranepool’s. Of course it was. Steadiest Eddie was always around. That was worth more than WAR. The most memorable snippet of his brief speech was an admonition to the 2019 team to not give up despite being buried in the standings. “They can do it like we did,” he said to great cheers. The modern Mets eventually listened and inserted themselves into a playoff race you would have thought they’d have needed to pay admission to see.

I’d pay admission to attend a reunion of 1979 Mets. Or 1966 Mets. Or any Mets. With Steve Cohen taking over, anything is possible. That Ed Kranepool would be eligible to speak at eighteen of them would make the proposition only more attractive. Nobody ever earned the title A Met for ALL Seasons as much as he did from 1962 through 1979. Before 1980, you couldn’t imagine a season without Kranepool. The slice of 1970 he’d spent at Tidewater was surreal enough.

In Spring Training of ’79, prior to his 18th season, the player to be named later from the Jerry Koosman deal, a minor league reliever named Jesse Orosco, impressed enough to make the ballclub. Or maybe Orosco was chosen a couple of weeks shy of his 22nd birthday because the Mets could pay him the minimum (they’d cut Nelson Briles in camp so they wouldn’t have to pay him a veteran’s salary despite Briles taking part in the Chico Escuela bit). As every baseball fan knows, Jesse Orosco would do so much sticking around in the major leagues that the Mets would be able to trade for him a second time, a dozen years after trading him away, more than twenty years after trading for him the first time, fourteen days before the turn of the next millennium. The Mets wouldn’t hold onto him when they did — they’d trade Orosco for Joe McEwing in Spring Training of 2000 — but that’s some serious sticking around. Jesse was still pitching in 2003, when Jose Reyes was a rookie. You’d figure Kranepool would feel a bond with Orosco based on longevity alone.

Of course the Koosman-Orosco connection is a staple of all Mets historical discussion. The happy kind, anyway. Two pitchers have been on the mound for the last out certifying the Mets world champions, and they were traded for each other: Koosman from 1969 for Orosco from 1986. Not that we knew the back half of that equation in 1979. Yet in 2012, at the Hofstra Mets 50th anniversary conference, I heard Ed Kranepool, in the midst of excoriating the Mets for too swiftly disassembling the 1969 club, rail against the Jerry Koosman trade, even dismissing the Orosco portion of the transaction and the eventual great news that came from it when a friend of mine brought it up to him.

“I don’t care about any Jerry Orosco,” Kranepool fumed.

I’m sure he knew the pitcher’s name was Jesse, but as they said in Animal House, forget it, he’s rolling. And besides, he’s Ed Kranepool. He was being loyal to Jerry Koosman; to 1969; to the Mets he knew best, the Mets with whom he most closely identified, the Mets for whom he’d stand and speak in 2019. Koosman for Orosco turned out to be not a stone steal for the Mets the way we wish all our trades to be (Kooz pitched seven seasons after leaving the Mets and won twenty games as a 37-year-old as soon as he did), but you can’t say it wasn’t a plus trade for the Mets. Orosco grew into an All-Star closer. It was not incidental that he was on the mound for that second world championship. And he did pitch several seasons into the next century.

And we tip our cap right back to ya, Ed.

Yet at that moment in 2012, when Eddie was hopping mad all over again that the Mets had traded away his last friend from 1969, leaving him to carry the banner into miserable 1979 all by himself, a fan who’d predated 1986 could feel himself empathizing with the Krane. Yeah, how could they do that to you, Eddie?

Eight years later, that same fan would saddle Kranepool with carrying the 1979 banner, but forget it, I’m rolling.

Ed Kranepool became a Met in 1962. Seventeen years later, he was still a Met. It was miserable 1979. I became a Mets fan in 1969. Seventeen years later, I was still a Mets fan. It was glorious 1986. Meaning? I dunno. Stick at something long enough and you’ll be punished or rewarded, perhaps. But it doesn’t matter that in my eighteenth year of Mets fandom, I received the gaudiest, most overpowering and dominant season of Mets baseball ever, and that in Ed’s eighteenth year of playing for the Mets, he was part of the most depressing, least encouraging season of Mets baseball ever. It wasn’t like either one of us was going to do or be something different.

I’m certain I’m more sentimental about it than he is, but we’re both as loyal as can be to our Mets.