The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 20 April 2010 3:14 pm It’s great to be young and a Met, Ike Davis could tell you after his most successful major league debut Monday night. The 23-year-old first baseman was the toast of Citi Field from the moment he showed up wearing No. 42. If ever anybody stood out in a mononumeric crowd, it was this kid who came up from Buffalo and raised Mets fans’ hopes and won Mets fans’ hearts with an easy swing, a power stroke and two hits quickly stashed in his pocket.

He was too amped to wait for more. Hence, he arrived at the ballpark early Tuesday. First one in the clubhouse, first one dressed. Ah, that rookie spirit combined with tangible talent. What a pleasure to have around. We’re gonna like this Ike Davis. We’re gonna like him for a long time.

Naturally, being the first one to report to the clubhouse means you’re all alone there. So when the phone rings, and you realize it’s only you in there, you answer it. You’re a rookie — you want to do everything.

“Hello.”

“Hi,” says the voice on the other end. “Is this the Mets clubhouse?”

“Yeah.”

“Oh wow! I can’t believe I got through! Can I talk to that awesome Met they just called up? The one who we’ve been dying to see, the one who’s singlehandedly pulling us out of this horrific teamwide slump?”

“Speaking.”

“Ohmigod, I can’t believe it’s you!”

“It’s me. Who is this?”

“Are you kidding, I’m your biggest fan?”

“I have a biggest fan already?”

“Of course you do. I’d been reading about you at Triple-A, and now you’re off to this great start, and I just know you’re gonna be the one to lead us to the promised land.”

“That’s a lot to ask of one rookie.”

“Don’t be so modest. If anyone is the harbinger of great Mets things to come and is going to be an eternal favorite of Mets fans, it’s you, Alex Ochoa.”

“Who?”

“Alex, stop kidding around.”

“I’m not Alex O…whoever you said.”

“Seriously, who is this, really? Is this Mark Clark pretending to be Alex Ochoa? If it is, stop screwing around, Mark, and put Alex on.”

“I don’t know who that is either. I think you have the wrong number.”

“You said this is the Mets clubhouse.”

“It is.”

“You said you’re that awesome Met they called up who we’ve been dying to see.”

“I am.”

“But then you say you’re not Alex Ochoa. That can’t be! We all worship and adore Alex Ochoa here.”

“Here? Where’s here? Where are you calling from?

“1996.”

“Huh?”

“This is a call from 1996. We all love Alex Ochoa here, we’re all convinced he’s going to be a five-tool superstar and that Mets fans will always love him the way we do now. I mean, we called WFAN and everything. We demanded Alex Ochoa come up. He was hitting .339 in Triple-A and he had to be better than what we running out there. So when he came up to stay, we were elated. We gave him standing ovations every time we saw him.”

“Sorry, I never heard of him.”

“Yeah, right. Everybody here knows Alex Ochoa. Alex Ochoa was batting .400 after seven games. Then a few days later he hit for the cycle in Philadelphia. New York magazine ran a feature on him calling him ‘The Cuban Missile’.”

“Sorry, dude, I never heard of Alex Ochoa.”

“That’s a good one, Chris. You’re Chris Jones playing a joke on me, right?”

“Seriously, I have no idea who these people are.”

“Fine. Just tell Alex Ochoa that 1996 called and that we’re all behind him here.”

Weird, Ike Davis thinks. Weird the calls they get in big league clubhouses. Yet just as he finishes the thought, the phone rings again. He looks around, sees no one else has come in, so he figures he’ll take his chances and answer it again.

“Hello.”

“Hi, I’d like to speak to the first baseman.”

“You’ve got him.”

“Awesome! You’re doing an awesome job!”

“That’s nice of you to say, but I only just got here.”

“Small sample size or not, I can tell you’re the real thing. You’re just what this team needs.”

“Well, I’m trying. That’s all I can do.”

“‘Trying…’ You’re succeeding is what you’re doing. You come up, and first thing you do — POW!”

“It wasn’t that big a hit.”

“Not a big hit? C’mon, it was huge, Mike!”

“That’s Ike.”

“What?”

“You got my name wrong. It’s Ike.”

“If I’ve got it wrong, so do the announcers and everybody else. They’ve been calling you Mike all week.”

“They have?”

“My apologies, Mr. Jacobs. I thought your first name was Mike.”

“Jacobs? I’m not Jacobs. Jacobs doesn’t work here anymore.”

“Huh? That’s doesn’t make any sense.”

“I don’t know what to tell you.”

“Wow, this is certainly news to everybody here. He’s not on the DL already, is he?”

“DL? No…hey listen, I know I’m just a rookie first baseman, but I thought everybody knew. I heard it on the radio in the cab when I got into town that Jacobs was gone.”

“On WFAN?”

“Yeah, I guess that’s the station.”

“But I was just listening to WFAN the other night after Mike Jacobs was tearing it up in Arizona, and everybody was so excited. Steve Somers was playing this really catchy song, ‘I Like Mike‘…”

“You mean Ike.”

“No, not ‘I Like Ike’. That’s the bit. The song is called ‘I Like Mike,’ by somebody named Jay Spears. It’s a real song, and Steve was playing it because we’re all so hyped up about Mike Jacobs hitting all these home runs.”

“Home runs? When?”

“When? Now?”

“Sure, now. When else?”

“Hey buddy, where you calling from?”

“I’m calling from 2005. Everybody here is totally into Mike Jacobs. Four home runs and 9 RBI in his first four games! We’ve got him penciled in at first for the next five years. I can only imagine where he’ll be by 2010.”

“Uh, yeah. You’ve got the wrong number.”

“Hey, if you see Mike, could you tell him we’re going to start a fan club for him? And a Web site?”

“I gotta go. Bye.”

Enough, Ike thought. Enough with these strange phone calls he didn’t understand. He was just happy to be here, in the big leagues, with the Mets. He’d deal with the media and the fans out there, on the field.

But then the clubhouse phone rang again. Ike, still all by his lonesome, felt obligated to pick it up again.

“Hello.”

“Uh, hi, I was wondering if anybody there remembered Daniel Murphy.”

“Oh geez, let me guess. You’re calling from 2008, you’re going to point out the hot start Daniel Murphy got off to when he came up, how he was hitting .467 after 30 at-bats, how Mets fans swooned over him as if he was a lock to be a superstar here, how Shea Stadium sold out of MURPHY 28 t-shirts as soon as they went on sale and how this should be a cautionary tale for me as well as Mets fans because I’m a big deal right now, yet you never know what kinds of detours a baseball career will take. Is that it?”

“Uh, no.”

“Oh, sorry. Can I help you?”

“Um, this is Daniel Murphy, down in Florida rehabbing. I was just wondering if anybody remembered me. But yeah, now that you mention it…”

Ike hung up and trotted outside for early BP.

by Jason Fry on 20 April 2010 12:45 am Ike Davis: I am NOT the Messiah!

Mets Fans: We say you are, Ike, and we should know — we’ve followed a few.

Apologies to Life of Brian, but that what’s it’s been like over the last 24 hours: Ike Davis was hastily recalled from some hazy, happier future to the troubled present, and after thinking about the prospects of halfheartedly cheering for Gary Matthews Jr. to not strike out or John Maine to reach the sixth inning, we decided that yes, we do like Ike and would like him front and center as soon as possible. Ike is up, having spent just long enough enjoying Buffalo to ensure he’ll enjoy whatever city we tell him to enjoy through 2016, and life is better.

I’ve always had a weakness for the possibilities of rookies and the ceremony of their debuts.

When I was living in Washington D.C. in the summer of 1993 I drove to Philadelphia to see Bobby Jones’s debut, which now strikes me as a preposterous thing to do. Jones was victimized by typical 1993 Met defense, but won because Tim Bogar went 4-for-5 with two home runs. The second was an inside-the-park job keyed by Lenny Dykstra diving for the ball and missing. Bogar slid safely into home, but tore a ligament in his hand, was out for the year and never the same player. I spent the game in front of Veterans Stadium’s gigantic videoscreen. It made unpleasant, vaguely organic wheezing noises while it operated, like a failing organ, and I could feel a pulse of heat when pixels behind me lit up.

On Opening Day of 1996 my new friend Greg Prince and I sat in the right-field mezzanine (I paid $13 to sit in section 33, row G, seat 5) to watch shortstop Rey Ordonez ply his trade against the Cardinals on a misty day. The Mets fell behind 6-0, but cut the deficit in half thanks to home runs from Todd Hundley and Bernard Gilkey. In the seventh, with two outs and Royce Clayton on first, Ray Lankford hit a double to left off Jerry DiPoto. Ordonez took the throw behind third base and hurled it home from his knees with an oddly fluid motion, somehow simultaneously collapsing, rolling over his shoulder and imputing all the energy of his body into the throw. Clayton was out at the plate, and I heard a sound I’d never heard before at a ballpark — the sound 21,000 people make turning to the person next to them and asking if they saw that. The Mets won, 7-6. I assume Tony LaRussa overmanaged.

In the summer of 2004 I dragged my friend Tim to Shea for a meaningless game against the Expos, because young David Wright was making his major-league debut. I paid $23 to sit in section 3 of the upper deck, the 711B box, seat 2. Wright, hitting seventh, was retired by Montreal’s Brian Schneider on a deft catch over the dugout rail in the second inning and went hitless on the day. But the Mets won, 5-4, on an error by Nick Johnson, overcoming a three-run homer by Montreal’s Endy Chavez.

My presence at Ike’s debut was sheer luck — I had a ticket thanks to the kindness of Sharon Chapman, runner extraordinaire and all-around Good People. I came to the game from a meeting in midtown with a backpack full of layers and Mets gear; when the V train dipped below the East River I stripped off my Responsible Adult button-down and blazer, leaving a t-shirt foundation, then donned a long-sleeved shirt, hoodie, Mets replica jersey with the wrong Tug McGraw number and Cyclones cap. By the time we emerged in Queens my transformation into Met Man was complete.

At Citi Field the night held a foreboding chill but the crowd was cheerful enough, politely applauding Rachel Robinson and various college students wearing 42 jerseys with can-do qualities stitched in the place of names while trying to figure out which Met wearing 42 was the new guy. Rachel Robinson is a treasure, but I’m willing to stick my chin out and say that having home-and-away Jackie Robinson Nights is a mistake that threatens to cheapen a moving gesture.

But soon enough it was game time, and so Greg, Sharon, David and I settled in to see if Ike Davis could indeed save us from all that has gone so depressingly wrong of late. The fans cheered Ike’s every move, with a good third of the crowd rising to its feet for his first at-bat. (That struck Greg and I as a bit much; we cheered with behinds firmly affixed to our seats.)

Ike did the job, reaching out his long arms to muscle a Randy Wells changeup into right in the second and adding an RBI single under second baseman Jeff Baker’s glove in the seventh. At home in the land of Wi-Fi (an amenity that would make a great addition to Citi Field), I watched the replay avidly, loving that you could see the moment when Ike realized the ball he’d struck was ticketed for the outfield grass, and treasuring the first-hit pageantry: the rookie trying and failing to look like it’s business as usual, followed by the momentary worry that someone might forget to ask the opposing team to surrender the ball or that it might accidentally get tossed into the stands. (An hour or so ago, you can bet, some teammate handed Davis a battered decoy ball with all the information scribbled down wrong and something crossed out, just to see if he’d panic or blow his stack. Though since his father was a big-leaguer himself, maybe he knew this initiation was coming.)

The rest of the game was pretty good too: Jon Niese pitched gamely, though his inefficiency made you remember the Maine, Angel Pagan clubbed a two-run homer into the left-field seats to break a tie, and Jenrry Mejia closed things out. Between them and Ike, you could consider it a preview of a brighter Mets future. And who knows? Maybe it’s not as far off as we fear.

by Greg Prince on 19 April 2010 2:08 am Pirates manager Jim Leyland took issue with the team’s We Play Hardball promo. “We can’t say we play hardball, I’m tired of that bleep,” he said.

—Peter Gammons, Sports Illustrated, June 9, 1986

Adam Wainwright gave the Cardinals everything they could have asked for Sunday night: a 107-pitch complete game victory. John Maine gave the Mets everything they could have asked for: five innings, 115 pitches, not putting victory hopelessly out of reach too early.

The Mets don’t ask for much — and they don’t receive it very often. But this time they got exactly what they were looking for. An experienced baseball man in the team’s employ eagerly anticipated the Mets losing two of three this weekend, and he got what he said he wanted.

I unleashed a steady stream of expletives in the latter half of the Saturday marathon as well as all kinds of incorrect predictions (of the “oh god, we’re gonna lose right here” nature) and certain declarations that never had a chance of holding up in any fan court of law. During whichever extra inning it was when we couldn’t seem to do anything right before we actually did, I declared, “IF WE LOSE, I GIVE UP!”

Which, of course, was silly. I knew it was silly so quickly that I immediately recanted it. C’mon, I thought, if I haven’t given up over these past few years, why would I give up now?

The Mets didn’t give up on Saturday, which was truly to their credit, considering the man who ostensibly makes the decisions that affect them most kinda, sorta gave up on them Friday.

One of the underlying drags on my fandom since 2007 has been the tendency of the Mets organization — though we probably shouldn’t assume they’re organized — to overstate their competitive excellence. While they were proving unprepared for all comers, their brochures insisted prematurely that Our Season Had Come. When the Collapse of 2007 was resonating clear to the Echo Collapse of 2008, Mets management treated both colossal catastrophes as aberrations in deference to the partial success of 2006. And when all unraveled on the field in 2009, the bad play wasn’t the thing; it was just bad injured luck.

The Mets’ losing is unfortunate, but the Mets institutionally preening while in the act of losing has been the grating part. Even allowing for marketing campaigns that will, by necessity, play up a product’s attributes over its drawbacks, the face put on Mets baseball was surely akin to the one Nero wore while furiously working his Charlie Danielsesque fiddle. Flushing is burning? We’re having Ash Day! (First 25,000 fans only.)

Have the Mets overhyped their ability in the past? Does Charlie Daniels play a mean fiddle? I once worked with an advertising salesman whose credo was, “Underpromise and overdeliver.” Do the opposite, he said, and you’ve got grumpy customers. When the Daveotronic 5000 robotically insists the Mets are World Series-bound, it’s a bit of a turnoff, no manner how kindly the Daveotronic’s sound chips are programmed. When pamphlets hawking season tickets suggest a Belief in Comebacks and nothing more, that’s easier to digest. From a 70-92 mudhole, the most nominal of comebacks would require only 71 wins and your minor league honcho keeping his shirt on. Leave the “postseason option” bait for the fine print until such an enticement proves operative.

Better yet, just hang out that GAME TO-NITE sign and we’ll figure it out from there.

If you’re gonna sell us fertilizer, I’ve been thinking since the Mets went to seed, don’t grin and tell us its top-grade Soilmaster, y’know? If you’re not gonna play baseball like it oughta be, don’t pretend that’s what you’re gonna do. I’m not talking about advertising campaigns per se. I’m talking about your general portrayal of what you’re putting out there. If you can’t legitimately say you’ve got a great team playing great, then, really, just say we’ll sure try to win. Failing that, say nothing at al.

“This is an era of limits and we all had better get used to it.”

—California Governor Jerry Brown, 1975

The same advice would hold true when reality and despair merge into a year like this to date. For example, if the team for whose performance you are responsible is not on a roll, but is at least on a one-game winning streak as it was following Thursday’s feelgood finale in Colorado, don’t bring everybody down by telling a widely read national baseball writer the following:

“St. Louis is always tough. If we can win two out of three, that will be outstanding. If we win one, I’ll take it.”

For the love of Mike Birkbeck, don’t do that. Don’t, if you are Omar Minaya, tell Jon Heyman of Sports Illustrated that sweeping a three-game series in April is off the board and that simply not being swept is an acceptable outcome.

It was too late, as Ray Stevens might have put it. We’d already been incensed…and still have yet to experience a streak that involves anything but losing.

Think it all you want, but don’t tell Jon Heyman, because Heyman’s gonna tell us, and boy is it gonna bring us down to new depths we had yet to contemplate nine games into this rapidly hollowing season. We may think it, too, but we don’t know it for sure, and we sure as hell don’t wanna hear it from you.

We don’t really wanna hear much from you, Omar, beyond, “I want to spend more time with my family” at your reluctant resignation press conference. As much as I don’t want you to BS me, as you did via Heyman, about how awesome your 3-6 (soon to be 4-8) Mets will be as soon as Murphy and Beltran and the ghost of Iron Man McGinnity come off the DL, I don’t need you to think out loud that the Mets seemed capable of no more than one win in three against the Cardinals this weekend.

They’re the Cardinals. They’re not the Popes. They’re not supposed to be infallible. And in baseball, no one is so sinfully terrible that they can’t conceivably win a series from a team with a better record. Not even the 2010 Mets, who are being positioned internally less like the best-compensated roster in the National League and more like a 49th-year expansion team.

We’ll take it if we can win one out of three in St. Louis, Omar said. Jerry Manuel, meanwhile, told Brian Costa of the Star-Ledger before Friday’s series opener that if the Mets are still “in the game” when Ollie leaves, he’d consider it a good outing. Nice to read such confidence emanating from the manager. FYI, Iron Man McGinnity completed 44 of 48 starts for the 1903 Giants, and I’m guessing John McGraw expected nothing less…and I’ll bet Tony LaRussa was looking for nine from Wainwright Sunday the way Davey Johnson counted on Rick Aguilera to do the same — which he did — on July 5, 1985, the game after that famous 19-inning marathon in Atlanta.

The Mets seem to be about cutting slack, so I’ll attempt to do the same, a bit, for the general manager and manager by acknowledging it’s a long season, and there are a clutch of reporters following Omar and Jerry around at all times with notebooks and tape recorders for just about every day of it. It’s an unnatural situation, but it exists in baseball. Over the course of Spring Training, 162 games and Hot Stove gatherings, people will say things (such as “how do you get a job in baseball?” per Adam Rubin). Not all of it should be taken literally. It gets tiring out there on the road, I imagine. You must think out loud a lot, sometimes before you think to yourself. You just find yourself saying what wouldn’t make sense to you if it was placed before you in script form. I’ll bet Omar Minaya would question a cue card that instructed him to tell a high-profile media member that he’d be satisfied by his team losing two of its next three games.

Omar can’t possibly be as clueless as he comes off. But he does tend to repeatedly come off that way, and he did again. He admitted winning one of three this weekend would be all right by him. You can take that as an inadvertently articulated realistic assessment of having to face Chris Carpenter and Adam Wainwright in two of three games, or you can be aghast that the general manager of a sports team is writing off two of three games before they’re played.

Most things in this life aren’t measured in terms so simplistic that they can be chalked up as either wins or losses. Yet in baseball, that’s exactly how things are measured. You win or you lose. There’s room for nuance and big pictures and all that, but eventually, there are wins and there are losses. That’s all that gets measured in the standings, and the standings are all that determine your success. Omar Minaya said, whether he meant to be so forthcoming or not, that he would take losing two of three games in St. Louis.

And I’m sure he took it well.

As for Jerry, I don’t know. Last Saturday, after the ninth inning during which few cheered without electronic tickler, I told my friend Joe that the good thing about this upcoming road trip was if the Mets do badly, it will help get Jerry fired. Then I thought for a moment (albeit with no recording devices to take down my clarification) and amended that sentiment:

“Or they could win some games and it would mean Jerry is a good manager.”

If we follow the McCarver memorandum that no team’s as good/as bad as it looks when it’s winning/it’s losing, we have to apply that lesson to managers. When Jerry Manuel blew in as a breath of fresh air in June 2008, and the Mets started to reel off victories a few weeks later, man, could Jerry Manuel manage. Everything he said was deep or funny or both. He was gangsta and we were his happy homies.

Now and again, there’s a flash of whatever it was that made Jerry Manuel appealing beyond his not being Willie Randolph. During Friday’s PIXcast, Gary Cohen explained how Jeff Francoeur’s batting eye became his taking eye. Manuel asked him what pitch he’d want if the seventh game of the World Series was on the line and he was at the plate. Jeff showed him. OK, Jerry said, and proceeded to throw him BP with the caveat that he only swing when he gets his dream pitch. Next thing you know, Jeff Francoeur’s on-base percentage, before Saturday’s baseless game, is .535. I’d like to believe the same man who can get through to baseball’s most notorious free swinger has more on the ball than threatening to bat Jose Reyes third and actually batting Frank Catalanotto fourth.

Omar’s greatest attribute is sometimes he hasn’t been wrong about a player. Jerry’s greatest attribute may be a future in sports psychology. But neither is burning it up in his present position and neither is helping his cause by saying whatever pops into his head. “First, do no harm,” Hippocrates wrote in Epidemics, and there’s been a rampant epidemic of harmful Met stupidity already this season.

“It’s the classic Washington scandal. We screwed up by telling the truth.”

—C.J. Cregg, “Dead Irish Writers,” The West Wing

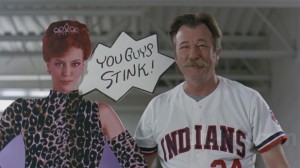

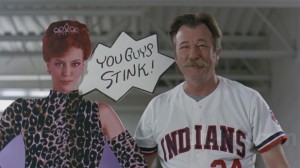

Omar's remake: One down, none to go. Win one of three? What did that mean once 20 ridiculous innings had been put in the books Saturday? That the Mets could follow Keith Hernandez’s example and hop the early plane back to New York Sunday morning? Fellas, Omar said we can take a personal day! Whatever happened to the fine example set by Cleveland skipper Lou Brown in Major League wherein he’s calculated it’s going to take 32 wins to clinch the division and with each Tribe triumph and pledges they’ll peel off 32 dress segments to stick it to their doubting hussy of an owner? In the Omar-directed remake of the movie, the Mets would remove one swatch of fabric and return numbly to their slumps.

“No,” Omar might tell Jennifer Aniston if he filled in for Mike Judge as her Tchotchkes supervisor in Office Space. “Fifteen pieces of flare, the bare minimum, is adequate. Just serve one of the next three meals and you can knock off early.” Too bad the Marlins didn’t alight at Shea the final weekends of ’07 and ’08 with the Omar attitude. We’d probably have two more banners in our museum right now.

Fifteen pieces of flare or one win in three games...either way, the bare minimum will do. The general manager said one of three would be fine. I sure hope that means tickets at Citi Field will be two-thirds off next week. And that Omar Minaya has to buy one if he wants to see the Mets.

Brent Gaff is what happened to the 1982 Mets. The other kind of “gaffe,” Michael Kinsley once wrote, “is what happens when spin breaks down,” but it’s not simply semantics at stake here. It’s the leitmotif of the current Mets to act as if just enough is enough. I couldn’t help but remember, as he circled the bases after his grand slam off Raul Valdes, that Felipe Lopez sat on the open market forever before the Cardinals snapped him up. You gonna tell me the Mets couldn’t have used a middle infielder/relief pitcher with some pop? Re-signing Alex Cora, heretofore hidden first base talents notwithstanding, was just enough. Felipe Lopez was more than enough. But just enough is apparently enough.

Just juggling the same question mark pitchers is just enough, so that’s enough. Just handing pre-designation Mike Jacobs a couple of dozen at-bats and Fernando Tatis a couple of dozen more is just enough, so that’s enough. For all we know, Tobi Stoner replacing Jacobs on the roster is just enough, and Ike Davis will continue to refine his home run swing in Buffalo.

Oliver Perez reaches the seventh and allows a baserunner his shortstop could have thrown out? That’s enough, Ollie. You’re working on a shutout (at last), but make way for relief. Mets lose by one run for the second time in three days? That’s close enough, seems to be the feeling. I keep hearing Jerry Manuel asked about the Mets having been in the game right to the end and Manuel doesn’t reflexively remind Ed Coleman that you play to win the game. He doesn’t dispute the moral victory theory at all; he brought it up again Saturday with Tim McCarver and Kenny Albert, deluding himself that one-run losses represent progress. Hours later, he’s instructing Luis Castillo to sacrifice-bunt against Joe Mather. It’s not a far descent from there into Art Howe “we battled” territory.

A balance can be struck between overblown hype and diminished expectations. The Mets haven’t found it. They’ve gone from chest-puffing to poor-mouthing. It’s no more comfortable a place than this start has been. Then again, living in last place is rarely an easy fit.

by Greg Prince on 18 April 2010 6:05 pm Winning in 20 innings by using 24 Mets who accumulated 9 hits despite batting against 2 Cardinal position players for the last 3 of those innings has generated some truly deep thinking among our readers, as evidenced by our unusually busy (for a Sunday) comments section and in-box. It’s great stuff, particularly the following, an e-mail to Faith and Fear from one Ben Nathan.

Surely there can be only one.

***

Dear Greg and Jason:

I’m a 16 year old diehard reader whom you’ve never met, but I want to share with you a couple of connections I made with last night’s game:

The first is that the game bore a striking resemblance to World War I. Both were epic monstrosities that robbed every witness and participant of his livelihood.

Both ended on account of utter fatigue.

Both began with promises of glory (Johan Santana vs. “The War to End All Wars”) and ended with shattered illusions (Mets’ failure to score vs. Felipe Lopez/Trench Warfare).

Both affairs were finally mitigated by a young, goofy upstart arriving upon the scene to bail out his misbegotten elders (Big Pelf/U.S.A.).

And finally, Jerry Manuel is Woodrow Wilson, a well-meaning intellectual who is nonetheless completely aloof and ineffectual.

My second connection comes in the form of a paraphrased quote from Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea:

But The Mets are not made for defeat.

The Mets can be destroyed but not defeated.

Thanks, and here’s to nine (nine!) innings of peace at 8 PM.

Faithfully yours,

Benjamin Joshua Nathan

***

Lost here in the, uh, excitement of the multiple innings Saturday night was the no-hitter thrown versus the Braves by Ubaldo Jimenez of the Rockies. Colorado has a no-hitter. We don’t. If you had told me on April 5, 1993, as their ragtag ballclub took the field for the very first time at Shea Stadium that they’d have a no-hitter before we did, I wouldn’t have believed you.

If you told me they’d have a no-hitter before we would play another 20-inning game, I might not have believed you either.

Never mind that they’d be in the playoffs (1995) before we would return to them (1999).

Last night, incidentally, was the first time the Braves were no-hit since Randy Johnson pitched a perfect game against them in 2004. On that very night, at virtually the precise moment Johnson was striking out Eddie Perez for his 27th consecutive out, Cliff Floyd was driving home Karim Garcia in a 5-4 walkoff win against Jason Isringhausen of the — who else? — the Cardinals. Nice symmetry, I’d say.

***

Prior to last night, the longest game the Mets had won was 19 innings, which happened twice. The most famous of them was the second one, clearly the most insane game the Mets ever played, Mets 16 Braves 13, July 4 and 5, 1985, which we memorialized here for all its rain-soaked and endless glory on its 20th anniversary.

Less instantly recalled is the first Met 19-inning win, played at Los Angeles on May 24 and 25, 1973. The Mets trailed 3-1 before a run-scoring Buddy Harrelson double in the 7th and a George Theodore RBI single in the eighth off 1969 Orioles reliever Pete Richert, the guy who gave up J.C. Martin’s extraordinarily well-placed bunt that won Game Four. That made it 3-3 for quite a while.

Much as the 19-inning game of 1985 was started by ace Doc Gooden and the 20-inning game of 2010 was started by ace Johan Santana, the 19-inning game of 1973 was started by ace Tom Seaver, proving it always helps to have your ace going in the literally big games. Tom pitched 6 so-so innings, however — don’t tell him 3 earned runs in 6 innings pitched is a “quality start” — and it was the Mets bullpen that ensured history that night and morning (game over at 4:47 AM EDT) by delivering 13 scoreless frames. George Stone’s first Met decision came that night, from having pitched innings 13 through 18, scattering 4 hits and 2 walks, twice inducing L.A. into stranding the potential winning Dodger run at third.

If only George Stone had been the subject of a much-needed managerial decision in the same state later that same year, but never mind that right now.

In the middle of the cascade of bullpen heroes registering bullpen zeroes stood Tug McGraw, who pitched from the 8th through the 12th. He walked 5 and surrendered 4 hits, but he allowed no runs and kept the game going into the wee small hours. Tug even managed a 10th-inning, two-out single off fellow screwballer Jim Brewer and advanced to second on an error by shortstop Bill Russell. With three Dodger runners cut down at home, his night wasn’t neat — Tug’s 1973 wouldn’t be for several more months — but, along with Phil Hennigan in the 7th and Stone during his six innings, it kept the Mets in the game long enough to score 4 runs in the top of the 19th, Rusty Staub, Ken Boswell and Ed Kranepool driving them in. Jim McAndrew picked up the save with a scoreless bottom of the 19th.

As with last night in St. Louis, that night (and morning) in Los Angeles was a full team effort, but I wanted to underscore Tug’s role since today, April 18, was the date in 1965 when Tug McGraw first pitched for the New York Mets. Manager Casey Stengel inserted him in the eighth inning of the fifth game of the season, the Mets trailing the Giants at Shea 4-1. Relieving Jack Fisher (who had just relieved Al Jackson), Tug came on with the bases loaded and one out to face pinch-hitter and future Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda.

Tug got Cepeda looking on strikes and then opposing pitcher (and future Met teammate) Bob Shaw to ground out to second baseman Bobby Klaus. With that, Frank Edwin McGraw was a big leaguer…a big leaguer who had gotten the Mets out of a bases-loaded jam. Stengel pinch-hit Billy Cowan for him in the bottom of the eighth, and the Mets wound up losing 4-1, but McGraw had officially made the first of the many marks he would make as a Met.

Finishing exactly 45 years after No. 45 started. It’s exactly 45 years since No. 45 first took the mound for the Mets. And on the day after the Mets secured their first marathon win that ever ran longer than the 19-inning victory of 1973, our friend Sharon Chapman — who is diligently raising funds for the Tug McGraw Foundation to help fight brain cancer and other terrible diseases — ran the Rutgers Half Marathon in just over two hours and thirty minutes (or 6 innings in modern baseball terms).

Congratulations to Sharon, whose wrist was banded appropriately for the occasion. If you’d like to contribute to the outstanding cause of the Tug McGraw Foundation, please visit Sharon’s fundraising site here.

by Greg Prince on 18 April 2010 1:08 am Tim McCarver called it a classic. The Baseball Tonight crawl called it a classic. Yet don’t mistake long for excellent. That was not a classic. It was certifiably long, the final result was immensely preferable to the alternative, and there were certainly aspects of it to like and even treasure, but that 20-inning Mets win we just witnessed was no classic.

It was something, though. It was futile for the longest time and then it was astoundingly absurd. I suppose, too, that it was survival of somewhere between the fittest and the dimmest, though I’m not sure that either unit was fit for battle by the end. I do know they were both kind of dim.

How do the Cardinals attempt to sacrifice a baseball game that counts? And how do the Mets almost not let them?

Gosh, this feels like wet blanket patrol. I mean let’s have some whooping and hollering to celebrate the only game the Mets have ever won past the 19th inning. Let’s hear it for all kinds of folks, starting with the starting pitcher Johan Santana (9 K’s in 7 shutout innings…duh, of course they were shutout innings) and flowing through every reliever except the really well-compensated one. You gotta give it up to Mike Pelfrey for coming out of the bullpen as well having the nerve to rock the world’s worst rally cap (inside out, Big Pelf, not sideways — don’t let Mex see the video). You gotta give it up to Alex Cora, almost never a first baseman but making a dynamite foul ball dive as a first baseman. Luis Castillo either executed the best tag or the best fake tag in the history of 19th innings. Jeff Francoeur and Jose Reyes could not have been more productive as 0-for-7 hitters.

And yet I feel dirty from the final three innings. I feel dirty because Tony LaRussa, know-it-all Artie Ziff to our squad of befuddled Ralph Wiggums, stopped using pitchers and started using fielders. Well, to be technically correct about it, he used a pitcher in left, but a shortstop and then a center fielder to pitch. That’s what you do when you’re losing 13-2 or it’s the last day of the season and you promised Jose Oquendo he could play all nine positions. But no, Tony LaRussa was serious as death. He sent out Felipe Lopez to pitch the 18th and Joe Mather to pitch the 19th and, when one materialized, the 20th.

It didn’t work, it wasn’t going to work, but it almost worked. And that’s why I feel dirty, because WHAT THE HELL WERE THE METS DOING SWINGING AT ANYTHING FELIPE LOPEZ AND JOE MATHER THREW AT THEM? They turned the farcical into the nearly tragicomic. It wasn’t surreal because nobody could have dreamed up the scenario of Lopez, the grand slam hitter from Friday, pitching to Raul Valdes, the grand slam pitcher from Friday. Valdes gets on and then gets thrown out trying to stretch an infield single that was thrown away into a double. I’m sitting on the couch yelling at Valdes for getting caught. It doesn’t even occur to me that this is Raul Valdes who probably hasn’t touched first base since he was six, and the whole irony of Lopez as the guy who slammed Valdes the night before is lost on me.

This isn’t supposed to happen quite this way. Marathon games are supposed to be wild, but they’re not supposed to be this…let’s say bogus. Forty-third inning? OK, pitch infielders when you have nobody left. Score is 28-28? Pitch the batboy. But it was nothing-nothing and LaRussa had pitchers left. He had Kyle Lohse (unless he pulled an Ankiel and changed his line of work when I wasn’t looking). He had Brad Penny. Are the Mets so not worth his time that he was just throwing whoever had a minimum of one arm out there?

And like I said, it nearly worked. The Mets couldn’t score off Felipe Bleeping Lopez and were lucky to scratch out a run with a sac fly in the 19th off Joe Bleeping Mather. Then, finally, the real deal, Frankie Rodriguez, fresh from warming up every inning since the 10th, probably, in to put the damn thing to bed. But this game was too cranky to be put down that easily. Ryan Ludwick tried his best to help the Mets by attempting to steal with nobody out while Pujols was batting (he also tried — and succeeded at — getting thrown out at home in the 16th), but Rodriguez couldn’t stand a hint of prosperity, and next thing ya know, Pujols (walked so often earlier that I could swear he had morphed into Barry Bonds) does what Pujols does, and he’s on second, and then, thanks to Lohse (natch), he’s on third. And then Yadier Molina drives him home.

Of course he does. Yadier Molina’s waiting in the weeds for us since October 19, 2006. “GET THE FUCK OFF THE COVER OF MY BOOK,” I told him, but at last look, he’s still there (and available in paperback with an all new epilogue, FYI).

Does any of this sound like a classic? Does it sound like a classic that we got to the 20th inning and Joe Mather was still pitching (I loved how Stephanie, who has very selective retention of baseball detail, recognized him immediately as Joe Mather from the inning before, as if Joe Mather was now literally a household name). Once again, the Mets couldn’t just stand around with their bats on their shoulders and dare Joe Bleeping Mather to throw strikes. They got it in their heads that the Cardinals had just reactivated Bruce Sutter from the Hall of Fame. Whatever; they manufactured one more run, turned their fate over to Mike Pelfrey and made a winning pitcher of Frankie Rodriguez — the only Met who gave up anything all day and night.

Omar Minaya can rest easy. The Mets have taken one of three.

Listen, I’m thrilled we get to update the Metsian annals where incredibly long regular-season games are concerned. Move over, Ed Sudol, C.B. Bucknor is now a marathon man behind home plate just like you were three unbelievable times. Move over, Ron Darling, Pelfrey is now the most recent starter to close when nobody else possibly could have. All the ghosts of Hank Webb and Les Rohr and Galen Cisco can go back to sleep. You pitchers who lost the 25th, 24th and 23rd inning affairs can doff your caps to K-Rod, somehow. He won what you guys couldn’t. Tom Gorman, someday you can bump into Messrs. Lopez and Mather and ask how they didn’t manage to give up a home run to Rick Camp. The 20-inning Mets-Cardinals game of April 17, 2010 will now be deservedly woven into the kind of legend and myth the Mets used to weave for hours on end every few years.

It will be legend. It will be myth. But it wasn’t a classic.

More epic coverage here from ESPN New York’s Mark Simon. Mr. Simon also queries Jason, me and a few other Metheads on less happy outcomes here.

by Jason Fry on 17 April 2010 12:33 am I suppose what I’ll remember from this game is the look of anguish on Raul Valdes’s face as he watched his curveball not curve.

Or, rather, it did curve — very gently, so as to offer itself politely to Felipe Lopez’s bat and thereby begin its long trip to a final destination beyond the left-field fence. Grand slam, Cards up by three, Oliver Perez’s singularly unlikely masterpiece ruined. The Mets held Albert Pujols in check, but boy did his supporting cast do a number on them.

Maybe if Ollie can repeat that surprising performance consistently we’ll see this as the beginning of hope instead of as a doubly cruel tease — a duel evaporated and a comeback turned aside. (From the Cardinals’ side, justice was served for Chris Carpenter, gone after a scintillating performance but still the pitcher of record when Lopez struck his blow.) More likely, we’ll remember this one as yet another reason to question Jerry’s use of the bullpen. Pedro Feliciano was laid low with a stomach bug, but wouldn’t it have been better to see Ryota Igarashi — who’s had a long record of success in Japan — than the iffy Fernando Nieve and Valdes, a 32-year-old rookie recently the property of Tabasco? The game was on the line right there, and Nieve and Valdes failed in spectacular fashion.

And before we get too excited about the bullpen, most of its early success has come during garbage time. The relievers have made four appearances in games where the Mets were up by a run or tied, and the only successful outing has been Hisanori Takahasi’s second appearance. The other three appearances saw Takahashi, Jenrry Mejia and now Valdes give up fatal home runs.

I could unearth positives. Yes, there was Ollie — what an odd turnabout to be hoping the Mets live up to Ollie’s fine work — and some nifty plays by David Wright, and contributions from the so-far underwhelming Frank Catalanotto, Gary Matthews Jr. and Mike Jacobs. But the Mets blew the lead in excruciating fashion and then failed to regain it in excruciating fashion. I have trouble extracting any kind of moral victory from that.

by Greg Prince on 16 April 2010 4:46 pm Welcome to Flashback Friday: Take Me Out to 34 Ballparks, a celebration, critique and countdown of every major league ballpark one baseball fan has been fortunate enough to visit in a lifetime of going to ballgames.

BALLPARK: Minute Maid Park

HOME TEAM: Houston Astros

VISITS: 1

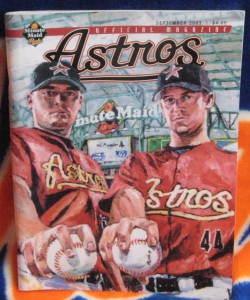

VISITED: September 22, 2003

CHRONOLOGY: 27th of 34

RANKING: 28th of 34

Call me Madonna circa “This Used To Be My Playground,” because Minute Maid Park was sort of my place to play.

Once, anyway. For a few hours. And I had to share.

It certainly provided a different perspective on ballpark matters. Everywhere else I’d gone, I was clearly a spectator. Not at Minute Maid. I was a participant. I was a player — a player for a moment.

Not an Astro, mind you, but I was on the home team. I worked for a diversified company owned by the same guy who owned (and continues to own) the Astros. I was editor of a new magazine that was holding an industry conference in Houston. Our draw was less the conference than the venue. Wrapped around the rather routine business sessions would be two events at Minute Maid Park. The second, on a Monday night, would be the Astros playing the Giants. The first, the night before, would be us playing on the field.

Membership in Team Drayton McLane would seem to have had its advantages.

To be fair, if you and your friends had the scratch, you could have rented out Minute Maid Park for an evening of hospitality and batting practice. When calling one of our sister subsidiaries, if I was put on hold, a recording let me know Minute Maid Park was available for affairs, for groups from four to 40,000. We had somewhere over a hundred at our conclave and, as I learned, we were charged like anybody else. I don’t even think we got a family discount.

Whatever the price of admission, I remember running around the field of Minute Maid Park, and that was pretty effing awesome.

I mostly roamed the outfield, particularly that dopey Tal’s Hill which is just as dopey (if not more so) in person as it is on TV. I took one round of BP, which I did with unathletic reticence, quickly forgetting everything I ever learned in gym class about standing in against pitching, even mechanized pitching. I inspected the out-of-town scoreboard from behind its slats. I sat in the visitors’ dugout trying to reload my camera in the dying days of film as a first option. I used the visitors’ dugout bathroom (just inside the runway to the visitors’ clubhouse), same place Mike Piazza might have relieved himself. I was well past my playing days in 2003, but I loved the idea that I could play. I loved the access to a major league field.

What I didn’t love, ultimately, was Minute Maid Park when I came back the next night as a mere spectator. Perhaps it was the being brought down to earth through the open roof effect. Not 24 hours earlier, this had been my playground; now I had to go find my seat like a schnook. But I don’t think that was it. Minute Maid Park just struck a wrong chord for me from the moment I approached it, even when I was going in with my glove on.

It’s in a part of Houston that, at least back then, contained nothing else with a pulse. Maybe a bar or two, but it felt plopped in as if to develop or redevelop downtown. I liked the idea of a converted train station, but it didn’t give off a ballpark feel from the outside. Nobody who worked there seemed particularly friendly (come to think of it, there were a lot of unfriendly people who worked for Mr. McLane). It was kitschy without being fun. Maybe it was an improvement on the Astrodome, which I never visited, but it was the first retro park I saw that I really didn’t much enjoy.

A few mitigating factors may have worked against me besides not being allowed to run around on Tal’s Hill during Monday’s game. Our seats, on a party deck to accommodate our conference group, were close to dead center. As I would learn years later at Citi Field, center field is not an ideal vantage point to take in a ballgame. Also, I was technically working. It wasn’t a tough assignment, schmoozing with our guests and such, but it wasn’t just an evening at the ol’ ballyard. Finally, I had a nagging headache that had been simmering since late afternoon. What I couldn’t have realized was the headache was the first symptom of what would explode into full-blown acute bronchitis by week’s end, a condition that may as well have been walking pneumonia.

The professional aspect of the trip — I gave a well-received presentation Monday afternoon — was also the unforeseen high point of my tenure with the magazine. McLane’s apparatchiks began to pick apart our personnel and screw with our structure, and within seven months, I was no longer part of the family. But I couldn’t have known that, either. I just knew I had a headache as I entered the ballpark and being there made it worse.

Perhaps out of corporate loyalty or my desire to really like the place where I romped the night before, I walked the perimeter pregame in a newly purchased Astros cap. I got a kick out of the ideas informing Minute Maid. I liked the Conoco Home Run Pump set up there in “awl” country to keep track of Astro home runs. I saw the rail car full of oranges and liked that they made the best of the shotgun marriage between Union Station heritage and Minute Maid sponsorship (after it could no longer be Enron Field). The touches and flourishes were good ideas, but the mélange of them resulted in a bit too much of a mélange. Here’s everything, Minute Maid seemed to shout. Isn’t it great?

Shortly after the game began, during one of the early between-inning breaks, our attention was directed to the big screen above us in center to show us the best of the games Friday night…high school football games. The Astros were in a race for the N.L. Central title with the Cubs — a Scotch-taped sign touting playoff tickets was affixed to a window outside (with no lines) — but this was the real action in Texas. That’s when it occurred to me what Minute Maid Park was at heart:

A baseball stadium for people who like football more than baseball.

At some point after the seventh-inning stretch (when we sang along to “Deep In The Heart Of Texas”), I slipped away from the conference group, and explored some more. Unlike at Shea, I was able to walk freely on the Field Level and positioned myself on the first concourse directly behind home plate. I could see mere rows away the back of Drayton McLane’s head. Quickly I called my wife and told her to find the Astros and Giants on Extra Innings. She couldn’t see me, but she could see him. She was looking at his front, I was looking at his back. It was almost like being at the game together with the owner.

Oh yes, the game. The Astros really needed it, clinging to a half-game lead over Chicago. They almost had it, too, having gone ahead in the fourth inning when Marquis Grissom couldn’t handle Tal’s Stupid Hill and Richard Hidalgo’s ball went for a triple (we had a fine view of that from center). San Francisco tied it in the seventh off Octavio Dotel. In the ninth, Astro closer Billy Wagner gave up a single to son of Astro legend Jose Cruz and then consecutive home runs to Pedro Feliz and Ray Durham. The Giants led by a field goal and fell successfully on the ball in the bottom of the ninth. Final: Giants 6 Astros 3, a flat-footed tie with the Cubs for the division.

I’d been at Shea in sickening situations like this but had never been at an alien ballpark when a non-Mets pennant race scenario unraveled. At Shea, we would have let out a terrible schrei, Yiddish for yell. At Minute Maid, they didn’t know from schrei (or, I’m guessing, Yiddish). Oh, there was some booing of Wagner, but when it was all over, everybody filed out peaceably. I couldn’t fathom it. Boy, was this an alien ballpark. Or maybe it was just that there was still time to catch the Broncos and Raiders on Monday Night Football.

The next day, as the conference ended, my throat beginning to trouble me. By Thursday, the Astros were out of sight, out of mind and I was back home at Schrei Stadium, my health be damned, to say goodbye to Bob Murphy. By Saturday, however, I watched with a bit of sadness as the Astros were officially eliminated from contention. The Fox cameras found Drayton McLane and he looked more glum than his customers. In that family sense, I felt bad for him — like grimacing in sympathy for your very rich uncle.

During the offseason, Roger Clemens resurfaced from his brief retirement to announce he’d pitch for Houston. Just after the 2004 season started, six years ago this very week, I was let go by McLane’s people; we had poor advertising sales, which wasn’t my department, but whaddaya gonna do? Having been invited out of the family, I couldn’t have been happier the following October when the Red Sox and Cardinals saved me from having to endure a Yankees-Astros World Series.

I had been a player — a player for a moment. That moment’s long over now, though, and that place in Houston is no longer my playground. It’s Minute Maid Park.

Rusty Staub used to be an Astro as well as a Met. Read about a Grand sighting of everybody’s favorite Orange on Loge 13.

by Jason Fry on 15 April 2010 10:40 pm It’s often this way when you’re furious with someone you love: Irritation boils up into anger and anger explodes into rage, but then the rage consumes its fuel and you’re left feeling tired and vaguely sick and wish you could just fast-forward to whatever point will allow you to start over.

So it was with the hapless, badly led, star-crossed 2010 Mets as they brought their 2-6 season into their third game in Denver: I hadn’t changed my mind about any of the things that are wrong, but I couldn’t stand to spend any more time dwelling on them. The Mets would play and I would watch and listen and we’d see how things went.

Luckily, a couple of things were stacked in their favor even before the game began.

There’s always a brief lift from the day game that caps a series and sees your team off to another city and another opponent — they’re moving on, for better or worse, and so are you. Similarly, there’s something about a midweek matinee with spring still stretching its legs: The physical season and the baseball season are both new enough that you’re not yet used to the idea of either, and so they feel like gifts. And for me, personally, there was the added wrinkle of the first game that I’d have to keep up with catch-as-catch-can, with the second half followed through quick glances and surreptitious Gameday watching during errands and the FAN in one ear while walking home with the kid.

Whoa, we're about to plow into Miguel Olivo. I love that aspect of weekday matinees, too: From beneath my headphones I watch other people scurrying around on their errands and see how few of them have a game to keep them company, and I thank my parents and good fortune for having brought me to the Church of Baseball. I don’t think I’ve ever felt truly lonely with a game in my ear — I’ve been sad and irritated and enraged and anxious and hopeful and very occasionally smug and triumphant, but never lonely. How could you be, with the announcers and the players and the fans right there with you?

Not that any of this would have been much help if the Mets had been awful and/or lunkheaded once again. And, hey, they did have their moments: The top of the third was a particular farce, with an incredulous David Wright watching baserunners disappear in front of him until he was alone and the logical thing to do was wave at a rare Jorge De La Rosa strike and disappear himself. But this time the dopey moments were comic relief, thanks to Mike Pelfrey.

Big Pelf was horrible in spring training, like every other starter handed a rotation spot just for showing up in St. Lucie, but he’s been awfully good so far. There’s the new splitter, a renewed dedication to pitching inside, a certain measure of meanness that’s been lacking, and so far a lack of, well, Big Pelf moments. Pelfrey isn’t a flake in the Tug/Turk tradition, but he’s certifiably eccentric — this is a guy, let’s remember, who last year tipped his pitches by wandering around on the mound muttering the name of the pitch he was about to throw. I sometimes wonder what it would be like to take a few minutes and see the world through Mike Pelfrey’s eyes. Would it be revelatory? Amusing? Terrifying? I don’t know, but I bet it would be interesting. (For one thing, most people would look a lot smaller.)

At least for today, things looked pretty good from that perspective. And so for the next 21 hours, some is forgiven.

by Greg Prince on 15 April 2010 10:33 am “This is Country Time lemonade mix. There’s never been anything close to a lemon in it, I swear!”

—Kid from Shelbyville, “Lemon of Troy,” The Simpsons

Upset that the Mets don’t have a plan? Please. The Mets have never had anything close to a plan in them.

I swear.

It would be too easy to say “plan” is a four-letter word to the Mets. I’d say it’s a no-letter word, given that the Mets plan nothing where baseball is concerned. Nothing from nothing, as Billy Preston advised us in 1974, leaves nothing. And you gotta have something if you plan to win again in our lifetimes.

By win again, I mean a title, though at this point I’d settle for a game.

Wednesday night, the Mets seemed close to snapping their losing streak that has now reached four but feels like forty. When the brainlessness of Mike Jacobs and the carelessness of Jose Reyes combined to let pitcher Aaron Cook score from third with two out and give the Rockies a 5-3 lead in the fourth, I braced for the worst. I braced for 2009 because that was a play straight out of last year.

What had kept my spirits from sinking through the wan homestand was that even though the Mets were losing, it was standard-issue losing. It wasn’t the fall down in left, don’t touch third, I GOT IT! I GOT IT! I don’t got it ineptitude that defined the previous season. It was a teamwide LOB slump that was bound to turn and mediocre starting pitching that could be attributed to arms still loosening (if you believe in the arm fairy). They didn’t look great, but they didn’t appear irretrievably irredeemable.

Then came the third inning Tuesday night, the Rockies leading 3-0, Maine struggling but surviving. Clint Barmes bounces one hard to the pitcher. The pitcher knocks it down. Alas, the bouncer knocks the pitcher down at the same time. The pitcher crawls, lunges, grabs and throws the ball somewhere toward Fort Collins. Two runs score to make it 5-0 and, six pitches/two Smiths later, it’s 8-0.

Seven games into 2010, and the Mets recalled 2009 from their Hades farm club. To make room on the roster, they designated immediate hope for assignment.

Of course the Mets would go on to lose 11-3 and look every bit the 2-5 team they were becoming. There was even a Dodger Stadium-style outfield interlude in the eighth. Last year it was Beltran and Pagan so successfully calling each other off Xavier Paul’s fly ball to deep left center that Paul wound up on second. Tuesday night, with Pagan in center and Bay in left, there was a replay of sorts, with the Jason the kind Canadian and Angel the polite Puerto Rican each practicing international diplomacy on Miguel Olivo’s similarly placed fly.

Sir, I would not deny you the pleasure of catching…

No, my good man, I cannot possibly allow myself to overstep…

Forgive my interruption, but truly that ball belongs to…

Now I will risk terrible uncouthness and interrupt you to say, really, I want you to have…

Olivo wound up on second. He didn’t score, but the point was made. The Mets sucked this year as they sucked last year. And the point was underscored again last night when Jacobs didn’t think to look Cook back to third and Reyes didn’t think to look up from not quite tagging out Dexter Fowler (who wasn’t too bright, either, but he’s Colorado’s problem) at second. While Mike and Jose weren’t thinking, Aaron was crossing the plate with the fifth Rockie run. It was 5-3 and I fully expected the floodgates to not so much open as come unhinged.

When they didn’t — when it remained 5-3 under the auspices of the Mets’ suspiciously effective bullpen — I began to have a feeling we weren’t quite dead. This was a game the 2009 Mets would have thrown away by the sixth or so inning. But Valdes bailed out Niese, Nieve bailed out himself, and two non-’09 Mets, Bay and Barajas, built themselves a run in the seventh. Feliciano was felicitous in the eighth, setting the stage for the top of the ninth when the Mets were the beneficiaries, not the instigators, of some shoddy defense. Gary Matthews was hilariously credited with an infield hit; he took off for second and wound up on third when Chris Ianetta’s throw just kept going. Luis Castillo brought Matthews home with a fly ball.

Igarashi kept things tied through nine, the fifth consecutive scoreless inning posted by Met pitching dating back to Niese’s last. When Jacobs launched a deep fly to right through that thin Coors Field air, it seemed the tables had finally and definitively turned in the 2010 Mets’ favor. Except the ball hit the high scoreboard, which was fine, and Jacobs had broken into a home run trot, which wasn’t. He stood on second with one out when he could have been standing on third.

Advantage Rockies — and 2009 Mets.

Everything after that was fairly predictable. Our best hitter, Francoeur, would be walked to set up a double play. In the midst of Barajas batting, Tatis was sent in to pinch-run for Jacobs. Tatis’s talents are limited, but I’d take his bat over his feet. Barajas grounds out, Tatis is on third, Francouer is on second and Cora comes up. Cora could have pinch-run and Tatis could have hit. Instead, Jerry Manuel went the characteristically unorthodox route.

It didn’t work. Nothing ever works. Cora hit a soft liner to second to end the threat. Ianetta made up for his lousy throw against Matthews by ending the game by taking Jenrry Mejia to school. As we learned long ago from ex-Rockie ace Mike Hampton, Denver has awesome schools.

So it’s 2009 again. Or maybe it’s 1992, the last time the Mets lurched to a 2-6 start. That season turned out so well that it was immortalized in its very own book, The Worst Team Money Could Buy, co-authored by John Harper, who continues to write for the Daily News and has, in today’s paper, a story on how Joel Piñeiro — 1 ER in 7 IP against the Yankees yesterday — sure would have liked to have been a Met, but said the Mets’ approach toward obtaining his services was “just weird”. Joel would have liked a million dollars more than the Mets were offering (an annual sum less than that currently being deposited in Kelvim Escobar’s account) but they never really got their act together. Like the man said, weird.

Was Piñeiro the answer? Were any of the free agent pitchers the Mets passed on answers? I don’t know, since I’m just a fan, but it’s obvious Omar Minaya and his merry band of talent evaluators didn’t know, either. They didn’t have an idea, and from a distance, it appears they didn’t have a plan.

Because they never have a plan. The Mets never have anything close to a plan. The Mets just take shots at players and hope some of them work out. This isn’t hyperbole. This is how the Mets have operated for more than a decade. Sometimes the pants-seat method pays off — fire sale Marlins, Quadruple-A journeymen finding themselves, high-priced free agents whose first year as Mets are their last years as topline stars. It’s great when the dice are rolled and come up sevens and elevens. It’s not so great when the Mets throw whatever at the wall and nothing sticks.

Not much is sticking at the moment. Jeff Francoeur wasn’t a plan, he was a division rival’s project, yet thus far the project has developed into something sturdy. Rod Barajas wasn’t a plan. He was approximately the third catcher, after Bengie Molina and Yorvit Torrealba, the Mets tried to convince to come aboard, and they seem to have found the charm. The various relievers who’ve not made us regret their innings weren’t a plan. They were inventory, to use of one of those charming Mets front office words for when they’re stockpiling and hoping to not run out of arms.

When things work out, nobody really questions how they came to be. Nobody cared in the late ’90s that Al Leiter and Dennis Cook weren’t the result of charts, graphs and scouting; we were just happy to scoop them up when Wayne Huizenga was going out of business. Nobody except hard asses with Players Association cards in their fat wallets cared that Rick Reed came out of nowhere in 1997. We were just thrilled that he chose to arrive as a Met. When Pedro Martinez in 2005 and Billy Wagner in 2006 did their best work immediately, not a lot of us wondered and worried about the years that remained on their pacts.

But when things don’t work, everything is up for grabs and under the microscope. That’s reasonable. We don’t have wins, so we want answers. If we have answers but not wins, we’ll want heads. That’s also reasonable. We’re not in this to be or fully satisfied by process or more than temporarily distracted by potential. We want to be 6-2, not 2-6. If we’re 2-6, we want a hint that we won’t be 4-12 before long. When we’re 2-6, we can’t believe we won’t be 2-160.

Ideally we’d like some long-range telescope that can see past whatever morass has semi-conditioned us to accept 2010 as a regrettable holding action against the promise of 2011, but in the Age of Minaya, there is no next year, just more of last year. And the year before that.

How the Mets nearly won the National League East or a Wild Card spot in 2008 continues to defy understanding. We had five great players — Reyes, Wright, Beltran, Delgado and Santana — playing great, and a cast of thousands slipping through Shea’s last set of revolving doors. I bring this up not just for hits and giggles but because I noticed something recently among one of the many Met lists I keep.

Every year there are players who make their major league debut as Mets. They are what an online acquaintance calls Born A Met. Conversely, every year there are players who play their last major league games as Mets. They are what this same gentleman calls Died A Met (died in the Jim Bouton sense of the word from the April 14, 1969 entry in Ball Four: “I died tonight. I got sent to Vancouver.”). This happens on every team every year, nothing unusual in that. Every player is going to debut somewhere, every player is going to stop playing somewhere, though that’s usually a trickier proposition. Few players take Ripkenesque farewell tours. They play until nobody wants them.

The thing I noticed in retrospect about the 2008 Mets is — pending any unforeseen comebacks — twelve different players played their last major league games in our uniform (not counting two youngsters, Eddie Kunz and Carlos Muniz, who were up in ’08 and are still in our system but haven’t been on the Mets since). None of them, from what I could tell, was bowing out gracefully. They were hanging on and, if somebody else would have had them, they’d still be hanging. Some are still doing so in minor, independent and foreign leagues. But two years later, twelve of them have been out of the major leagues for more than a full season and don’t show tangible signs of making it back

That’s a lot of players taking their last halting lap on the same team, a lot of players nobody wanted after we had them. As many players Died A Met in 2008 as Died A Met in 1963. That indicates the Mets of two years ago grasped at a lot of spare parts to fill in when they got desperate. They got desperate a lot in 2008, which is what they’ve been fairly often in the Minaya Era. (We can’t determine for sure yet all who Died A Met in 2009 as some not presently active aren’t technically prohibitively done.) It implies this is the way they’ve been doing business and it’s the way they still think.

In case you’re wondering, these were the 2008 Mets (besides Kunz and Muñiz, who still have a conceivable shot at returning) who haven’t been major leaguers since they were 2008 Mets:

• Brady Clark

• Gustavo Molina*

• Matt Wise

• Abraham Nuñez

• Raul Casanova

• Moises Alou

• Trot Nixon

• Tony Armas, Jr.

• Chris Aguila

• Brandon Knight

• Ricardo Rincon

• Damion Easley

Individually, Alou was supposed to be the starting left fielder, but age and injury took him out. Easley inherited second base for a spell, but age and injury took him out. The rest were essentially a series of stopgap moves. Collectively, the dozen Mets who nobody else has placed on a major league roster since totaled a 2008 WAR (Wins Above Replacement) rating of -1.0. That’s roughly a quarter of your players — the Mets used 50 in 2008 — who were statistically disposable at best.

That’s not a plan. That’s the scrap heap come to life. That’s bad luck as the residue of lack of design. That’s hoping for the best and expecting nothing in particular. That’s not even accounting for journeymen like Argenis Reyes and Ramon Martinez and Robinson Cancel whose journeys would continue with the 2009 Mets. Even as we understand injuries take a toll and spit happens and all of that, the Mets under Minaya have constructed the planet’s busiest space shuttle. They shuttle used players in and out, and a lot of space is taken up in the process.

That’s the background. The foreground is the annual splashy winter signing: Santana prior to ’08, Rodriguez in advance of ’09, Jason Bay for 2010. They and the “core” pieces in the Metropolitan collection give us reason to believe the Mets can be pretty good. Most of the background players — truly “extras” in the Ricky Gervais sense — ensure we probably won’t be.

Is it early? Is it not early? It almost doesn’t matter, ’cause it’s almost always like this.

*Molina returned to the majors in 2010 with the injury-plagued, catching-strapped Red Sox.

by Jason Fry on 14 April 2010 1:09 am The Mets are 2-5, and Gary Cohen’s advice is not to jump off bridges. It’s early, after all.

I agree nobody should be jumping off bridges. (Ever.) But when you think about the problems afflicting the Mets, they’ve been obvious a lot longer than seven games.

* Gary Matthews Jr. and Mike Jacobs have shown themselves as clearly inferior players to (respectively) Angel Pagan and, well, anybody over the small sample size of seven games. But Mets fans didn’t start saying that — or questioning how the Mets construct rosters — in the last seven games. Fans have been saying it since approximately midwinter. Judging by the cherry blossoms and the daffodils up and down my street, midwinter was a while ago. These are not early concerns.

* Concerns about the starting pitching haven’t exactly been limited to the first seven games of the season. John Maine was horrible tonight, but then he was horrible all spring and not so good the last two seasons. Oliver Perez was bad in his first start, awful all spring and mind-bogglingly terrible last year — the first year of the three-year, $36 million contract Omar Minaya gave him in the face of determined counteroffers from … somebody. These concerns existed this winter, when Joel Pineiro seemed to want to pitch for the Mets and the Mets reportedly couldn’t simultaneously manage signing Jason Bay and picking up the phone to express interest in him. These concerns existed last month, when Nelson Figueroa — a useful swing starter who’d had a good spring and was out of options — was let go in favor of guys who’d had bad springs, weren’t suited to duty as swing starters, and had options remaining. These concerns existed last month, when Jenrry Mejia was anointed a short man despite no record of success above the Florida State League, sidetracking his development as a starter. These aren’t early concerns either.

* Surveying tonight’s wreckage, Keith Hernandez talked about Plan B. But the epitaph of the Minaya regime should be the stubborn absence of a Plan B. Plan B for the shaky starting rotation? It’s in Anaheim, Philadelphia, and miscast in the bullpen. (At least Pat Misch is still around. Oh my God, I actually just typed that.) Plan B for backing up the varsity? That’s been a concern since Jose Valentin failed to bottle lightning twice in a row and Moises Alou was first felled by the impact of an errant raindrop. Plan Bs are apparently false hustle, a category that also covers remembering your ace had elbow problems in spring training, correctly judging the market for gregarious but useless middle infielders and taking steps to avoid looking like a fool by publicly spouting bizarre conspiracy theories about the motives of beat writers. No, concerns about Omar Minaya’s ability to do his job have been around a lot longer than seven games.

* The job security of Minaya and Jerry Manuel is a hot topic seven games into the season — every fan who called Gary and Keith tonight asked some variant of “When do they get fired?” But calls for their heads from fed-up fans are not new, and neither is the obvious lack of enthusiasm for them in the owners’ suite. The Wilpons, one hopes, are not having early concerns about whether it’s finally time to clean house. Because we’re far beyond that point.

Did I just say it’s time for Omar and Jerry to get pink-slipped? Yes I did. Are we just seven games into the 2010 season? Yes we are. But I would not say I have early concerns. I’ve been concerned since last summer, when the Mets turned a season of bad luck into a pitiful farce. My concerns intensified in the offseason, when Minaya and his lieutenants operated without the slightest evidence that they were following a coherent plan. My concerns became impossible to ignore in spring training amid bizarre roster decisions and apparently willful ignorance that the starting pitching was a disaster in the making. The first seven games of the season have been just the latest bead on a depressingly long string.

It’s just seven games into the season, but it’s not too early for someone with the last name Wilpon to say enough’s enough.

If anything, one wonders if it’s too late.

|

|