The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 2 September 2025 8:15 am Before the Labor Day matinee against the Tigers, a friend asked me an alarming question: Who are the Mets’ starters for a playoff series?

Kodai Senga? He’s been awful since returning from injury and Carlos Mendoza didn’t exactly offer a ringing, unambiguous vote of confidence about him remaining in the rotation. David Peterson? Bad start has followed bad start has followed bad start. Clay Holmes? Better of late but in uncharted territory as far as innings pitched, which we saw catch up to multiple Mets pitchers against the Dodgers in October. Sean Manaea? He hasn’t looked right all year, and has gone from “good early but ran out of gas” to “not good at all,” as was demonstrated against the Tigers.

Imagine a wild-card rotation of, say, Nolan McLean, Jonah Tong and Holmes. Or McLean, Holmes and the endless possibilities of Tylor Megill. Hell, call up Brandon Sproat and go all raw rookies.

Seriously, what are the Mets going to do?

One answer would be to outhit their mistakes, which is what they did Monday against the Tigers on a gorgeous day at Comerica Park. Juan Soto led the way, blasting a grand slam that ended Charlie Morton‘s day (and saved Brett Baty and Francisco Lindor from fannish tut-tutting about not delivering gimme runs) and then adding a two-run triple. The Mets got enough to overcome Manaea and not so great bullpen work from Gregory Soto, Ryne Stanek and walking disaster Ryan Helsley (who was at least yanked quickly this time).

Fortunately Edwin Diaz was up to the task, and the Mets didn’t so much win as survive. Not the most elegant strategy, but hey, whatever works. I have my doubts it will work when there’s bunting and clueless national TV crews on hand … but I also have my doubts it will work for the rest of September. Let’s worry about the problem at hand, shall we?

by Greg Prince on 1 September 2025 2:25 am The trumpeter who scores the postgame scurry to the 7 on Mets Plaza made an interesting musical choice in the minutes following the fresh 5-1 loss the Marlins had inflicted upon the Mets inside Citi Field. He played “Auld Lang Syne,” a number usually reserved for December 31 rather than August 31. I wondered if the wistful tune struck him as appropriate as we were bidding goodbye to summer on this late Sunday afternoon, or because the Mets have been dropping the ball with such force that they might be called on to re-enact their core incompetency in Times Square come New Year’s Eve.

Or maybe the trumpeter knows only so many songs and this was one of them. What the hell, the Mets played four games versus Miami as August ended, and they won only one of them. Not Sunday’s certainly. They took on Sandy Alcantara, and Sandy Alcantara reminded us he is still Sandy Alcantara, even if Kodai Senga resembled nothing remotely akin to Kodai Senga. We have our images of previously successful starting pitchers. Senga of the second half of 2025 is not to be mistaken for the Senga of yore…and his yore wasn’t that long ago.

The Met of the game was clearly Brandon Waddell. He’s been a Met multiple times this year but wasn’t the day before. He was called up to replace Chris Devenski, who could have said the exact same thing about his perpetually slippery job status 24 hours prior. Chris did a heckuva job in reclamation relief on Saturday, just as Brandon did on Sunday. One assumes that even with roster expansion Monday, Waddell will be optioned to cool his heels and rest his arm alongside Devenski in Syracuse. One wonders why it’s inevitably the relievers who “rescue” the bullpen who are sent down rather than the imploded starters they relieve. One wonders a lot with this club and should probably assume nothing.

Despite encompassing a couple of massive milestone moments — Alonso slugging his way past Strawberry; McLean and Tong emerging in our midst— the month that just ended cannot be considered splendid. Au revoir, then, to the last wisps of summer in Flushing, and welcome to September and the clean slate it promises. Don’t muck it up with too much Augustitude, if you don’t mind, Mets. All the months of this season have blurred into a kind of high-functioning futility that somehow still has this team in pretty decent position to make the playoffs. They’re trying to fall out before fall officially hits, but they’re really not that bad. They’re really not that good, either.

They are, on a record-to-record basis through 137 games, exactly what the Mets of a year ago were: 73-64. That would be neither here nor there, except for knowing that this marks the first interval of the schedule since the 2025 Mets were 0-1 that they’ve posted exactly as many wins and losses as their immediate predecessors. And that would be no big whoop, except the 2024 Mets molded themselves into spunky upstarts who captured a playoff berth and all of our hearts, while the 2025 Mets were supposed to skip the spunk and act as juggernauts from March onward. The last edition famously started 22-33 before turning it around. It’s “famous” rather than infamous because of what happened after 22-33. The contemporary bunch infamously started 45-24 before seeking new depths. Infamy can still be chased from the 2025 narrative, but suddenly it’s September and the rewrite desk is working on a tight deadline.

At this precise juncture of 2024, the Mets had won four consecutive games and were about to win five more. If the current squad doesn’t go undefeated from today through Saturday, the 2024 Mets will pass them. I understand that’s not who the 2025 Mets are competing with in the actual standings, but it indicates something’s historically awry — perhaps that ever since our juggernaut got towed in the middle of June, we haven’t been able to free it from the impound lot for more than a spin.

I make it my business to track things like Mets’ records after 137 games of every season they’ve ever played, which made me the ideal companion Sunday for Mark Simon, with whom I take in a game annually. Mark’s something of a baseball renaissance man, with his latest credit being the profiling of the broadcasting McCarthys, Tom and Pat, for a Tri-State Area college alumni magazine. But if you want to know my super-seamhead friend for anything, know him as the reigning SABR trivia champion, a title he wrested in Texas this summer. He didn’t wear the belt to Citi Field. He didn’t have to.

Our Mets-Marlins game was different from the one with which the other 43,300 on hand were burdened. In the top of the third inning, we dug into our quizzing satchels and pulled out the questions that we would deploy to preoccupy each other until shortly before the seventh-inning stretch. The first question could have been, “What baseball game, already in progress, will require a lengthy distraction?” We would have accepted, “this one”; “the Mets-Marlins game of August 31, 2025”; or “what Mets game lately doesn’t?” That gimme aside, the object of our trivia challenge isn’t to stump one another, but tease out answers nobody should know by dropping hints that nobody should grasp.

But we do.

Here’s a highly selective partial honor roll of past Mets who came up in the course of our questioning and answering:

Dave Mlicki — but not for the first thing you think of when you think of Dave Mlicki.

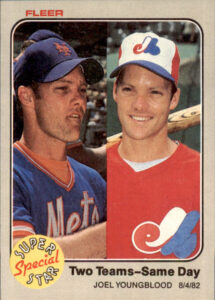

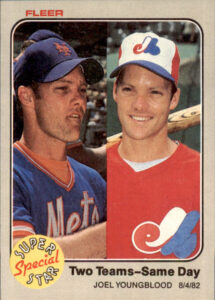

Joel Youngblood — but not for the “one thing” everybody associates with Joel Youngblood.

No, not that. Doc Medich — the pitcher identified via the clue that was essentially “he was a Met for no reason”.

Rick Cerone — the catcher identified via the clue that was essentially “he hit a dramatic home run once,” though the question had nothing to do with his being a catcher or hitting a home run.

Kevin Bass — the outfielder identified via the clue that was specifically “mimicry”.

Jim Hickman — who was answered by our seat neighbor who drifted into enjoying our game more than he was the one the Mets were losing to the Marlins. Maybe they should have lent us one of Alec Bohm’s parabolic mics and let more of the stadium eavesdrop.

Batista — this is a trick answer, derived from each of us having seen, in different parts of the ballpark before we met up, a guy wearing a jersey that read BATISTA 14 on the back, and as each of us knows, Miguel Batista sure as hell didn’t wear 14 when he pitched for the Mets in 2011 and 2012. We made a pact to stop Mr. BATISTA 14 if we ran into him on the way out and ask what’s up with that? (Alas, neither of us saw him again.)

Jay Bruce —my “how soon they forget” Met.

Bobby Parnell — Mark’s “how soon they forget” Met, though to be fair, Parnell isn’t quite as recent as Bruce.

Robinson Chirinos — not technically a correct answer, but his inclusion as an addendum to a series of correct answers seemed to tickle Mark more than any other name that came up all day.

We do some version of this every year, and it always tickles both of us no end. Between dealing questions, hints, and answers, we do manage to intermittently look up at the game in front of us. Its ability to tickle varies. The non-quizzing portion of Sunday’s game didn’t inspire much tickle on the current Met front. Moral of the story? Always pack your quizzing satchel, whatever the month.

by Greg Prince on 31 August 2025 11:10 am My whole life as a sports fan, I’ve seen teams seek “Wild Card” spots in playoffs and understood Wild Card to mean “not a division winner,” without ever really stopping to think of the term’s implication away from sports. To be certain I had it straight, I went to the dictionary (well, a dictionary site) so I could cite the definition of wild card accurately. It is “an unknown or unpredictable factor”.

Based on what the good folks at merriam-webster.com have to say about the matter, the New York Mets loom as the ideal wild card for the forthcoming postseason, because I can’t think of another contender whose actions from one game to the next answer so precisely to their dictionary definition. You never know what the Mets will do in the course of nine innings — even when you acknowledge that you never know what any team will do in the course of nine innings — and you’d be courting frustration if you attempted to predict it. Inning to inning, there’s no telling who the Mets will be or what the Mets will do. Within an individual inning, the outcome is beyond anyone’s educated guess.

If MLB were to give out Wild Card spots based on capriciousness, the Mets would be a lock. They give out Wild Card spots based on best records among non-division leaders. The Mets aren’t a lock, but even after losing the kind of game on Saturday it appeared they’d come back to win after appearing certain to lose, they appear to be in solid shape, five games up on the Reds for the final playoff berth. The Reds — who have three with us next weekend and a tough schedule in general — have been their own kind of meh lately and therefore haven’t been able to close in on the Met brand of meh. At the rate Cincy is going, they might fall behind any of three National League clubs that sold at the trade deadline. If you can’t beat out towel-throwers, you might not have what it takes to stay in the ring.

Appearances are in the eye of the beholder, however, for the Mets always appear to be something different. Saturday’s comedown followed romping on Friday; falling flat on Thursday; emphatically shutting out the team they’re chasing and effecting a series sweep on Wednesday; a thriller of a win on Tuesday; a romp on Monday; epitomizing not quite enough Sunday, a break-it-open-late thumping the night before; an all-around stomping that would have been more fully enjoyable had the bullpen not given away a bunch of runs toward the end the night before that; and failing to be competitive versus a last-place team the afternoon before that. Go back a little further, through splitting the first two in Washington and taking the last two from Seattle, and you have losing 14 of 16, which came after winning seven in a row, which came after a 7-6 stretch that surrounded the All-Star break, which seemed to lift them from a 3-14 descent, which negated a 15-3 surge, which we thought erased a 2-6 stumble, which took the edge off going 5-1, which made us think going 2-5 in the seven games prior was an aberration.

The aberration may have been the 19-6 spurt the Mets ran off on the heels of their sluggish 2-3 start to the season. At that point, on April 29, they were 21-9. Playing .700 ball figured to be unsustainable, but they looked good enough to do great things. Their few losses in that period seemed accidental, as if only they would focus just a little harder, they could go mostly undefeated from there to eternity.

Baseball seasons last longer than that when the winning isn’t reliable, and the Mets, despite sitting five clear of a playoff spot and ten above break-even, can’t be counted on to ride any form of consistency. Banking those wins early provided the foundation for the indecisiveness they’ve chosen since. Win a few? Lose a few? Lose a few more? No, wait, we like winning…we think… It may not be as conscious as all that, but it might as well be. It would at least explain why from April 30 through August 30, they’ve gone 52-54.

There are reasons within results, of course. There are reasons they lost, 11-8, to the Marlins on Saturday. The first reason was their most reliable starting pitcher over the course of 2025, All-Star David Peterson, couldn’t get outs when he needed them in the first and third innings, the latter a frame he didn’t escape. The second reason was the fixation Met defense has developed with fumbling. Perhaps they watched too much NFL preseason, but Mets with gloves the last few nights proceed as if those items on their hands are merely fashion accessories. The third reason, if we fast-forward toward the final third of the game, centered on an inability to hit with runners in scoring position, a discipline at which the Mets were suddenly excelling until they weren’t.

In between the bad parts — the falling behind, 5-0; the falling behind again, 8-2; the not completing the storming from behind once it got to 8-8 — there was swell stuff. There was Juan Soto giving off bargain vibes. Homered twice. Stole twice. Walked twice. Also ran the bases not brilliantly early, but you don’t necessarily wish to ding a 35/25 man for his imperfections. Mark Vietnos remained on fire, going deep for the sixth time in his last eight games. Francisco Lindor led off the home first with one of his keynote specialties as well. The Mets have been a home run juggernaut in August. They’ve never hit more in a calendar month, a span in which they are 11-16 with one game to go.

After Peterson all but took them out of Saturday’s game, yeoman reliever Chris Devenski and ageless lefty Brooks Raley combined with a mighty offense to get them back in it. Then Tyler Rogers made life a little more difficult, but Gregory Soto held firm. Except by then, the offense had gone back into sleep mode at the absolute worst time (runner on third, nobody out in the seventh) and never woke up. Edwin Diaz couldn’t keep it razor-close in the top of the ninth, and Cedric Mullins couldn’t extend a potential tying rally in the bottom of the ninth.

The Mets transcend streakiness. They’re not riding a rollercoaster as much as getting on and off it at every turn. One inning they’ve got their problems licked, the next inning they’re getting licked by the likes of the Marlins. This is a team that can scare and defeat any team it sees on its way to or in October, just as it can lose a series at any moment to any also-ran and not have it feel like a fluke or “just one of those things” that happens when you play 162 games. They’ve played 136 games to date. They have yet to offer a coherent vision of who they are.

But they have gone 9-5 in their last 14, which indicates they are capable of not giving up their five-game lead for the last playoff spot, and suggests that should they land in the playoffs, they can go 13-9 should they earn the opportunity to play every possible game presented to them. A curated 13-9 wins them a championship, but they can’t mount flash-mob losing streaks, because there will be no coming back from them. Two out of three in the NLWCS. Three out of five in the NLDS. Four out of seven in the NLCS and WS. It’s too soon to ladle out all that alphabet soup, but this is, somehow, a championship contender.

First, go 1-0 today and start fresh tomorrow. They’re always starting fresh the next day, as if they have no idea how they did what they did yesterday. I certainly don’t.

by Jason Fry on 30 August 2025 12:43 pm On the day Jonah Tong was born — Thursday, June 19, 2003 — the Mets lost 5-1 to the Marlins at Soilmaster Stadium. Mike Bacsik gave up an early three-run homer to Mike Lowell, things got worse in the fifth, and a dreary game eventually expired. I’m sure I was watching and also glad I don’t remember wasting that particular two and a half hours of my life.

The win let the Marlins leap-frog the Mets, leaving them last in the NL East. The Marlins would keep leap-frogging, finish with 91 wins and a wild-card slot, and eventually defeat the Yankees in the World Series, for which I’m grudgingly grateful. I still have a Yankees’ 2003 World Series champs shirt, intercepted between some warehouse and a no doubt now-shuttered foreign-aid program, and wear it proudly when invited to Yankee Stadium.

The 2003 Mets? Yeesh. That was the club of Roberto Alomar, of Vance Wilson and Jason Phillips and the Mets’ A/V staff assembling their highlights to “Hold On” by Wilson Phillips (getit?), of getting swept by the Yankees in humiliating fashion, of nepo baby brother Mike Glavine getting his first and last big-league hit the day the season mercifully came to an end. Faith and Fear in Flushing didn’t exist yet and that’s for the best, because I’m not sure we would have made it through chronicling 2003.

Tong grew up in Ontario, learned his craft under the tutelage of his father — complete with mechanics that look Xeroxed from Tim Lincecum‘s — and was drafted by the Mets in 2022. In 2023 he struck out seemingly half the world in the low minors but walked the other half of the world. But things improved in 2024 after he added a Tyler Glasnow-esque slider to his repertoire, and accelerated this year thanks to a much-refined changeup. That brought Tong from Binghamton to a toe touch with Syracuse and then on Friday night to Citi Field.

After we watched Nolan McLean decimate the Phillies on Wednesday, Jordan realized Tong’s debut was imminent and reasonably inexpensive seats were available on StubHub … hey, why not? (By the way, my kid is somehow eight months older than Jonah Tong … how the hell do these things happen?) So we abandoned a trio of Brooklyn Cyclones tickets to see a recent-vintage Brooklyn Cyclone instead.

What we got was a circus, and — if you looked closely — a promising MLB debut at the center of all the nutty stuff spinning around it.

As is often the case when you’ve attended a game in-person, I can’t tell you anything about Tong’s stuff, mechanics, or location that you couldn’t describe far better if you were watching on TV: He was a little figure in black from our vantage point down the left-field line deep in the 100s. What I can tell you is that the crowd was a friendly force behind him, greeting his arrival rapturously, exploding for his first strikeout, and standing in delight when he navigated a fifth inning made harder by his own stone-gloved teammates. (What is up with that, and could it please stop?)

The crowd knew Tong was only going five, they knew his escalating pitch count was putting even that goal in jeopardy despite the score, and they became a many-voiced rugby scrum fighting to keep Carlos Mendoza in the dugout and push Tong through the last few pitches he needed. It was Mets fandom at its informed, passionate bordering on mildly crazy best, and it was fun to be a part of it.

The circus part? That was more than mildly crazy.

The Mets jumped Eury Perez — a pretty capable young pitcher in his own right — for five in the first, courtesy of homers from Juan Soto and Brandon Nimmo. The outburst, while welcome, meant Tong sat in the dugout for nearly half an hour, not easy given any pitcher making his debut already has to contend with the sag in adrenaline after a first frame. The Mets then mauled recent-vintage teammate Tyler Zuber for seven in the second, another welcome explosion of run support that was necessarily paired with another half-hour of idleness for Tong. Somewhere Mike Pelfrey was smiling, while Jacob deGrom perhaps frowned and allowed himself a brief shake of the head. Asked about the up-downs later, a Gatorade-drenched Tong showed a precocious knack for postgame-interview diplomacy over candor, saying with a smile that he’ll never complain about run support.

(A personal aside: An oddity of my recent Mets viewing has been that I’d never seen Pete Alonso go deep. That came with an asterisk, however; Greg — who’d know — says he was with me when the Polar Bear homered, though he allowed that said round-tripper required replay review. It was nice to finally witness an unambiguous Alonso homer, complete with Marlins right fielder Joey Wiemer caroming off the Cadillac Club’s chain-link fence for some reason.)

With Tong departed and the Mets up 12-4, the game got truly weird.

I got an in-person look at Ryan Helsley‘s “Hells Bells” intro, an orgy of high camp that would be tut-tutted at as too on the nose if it were part of an Eastbound & Down bit. How has it not occurred to someone with the Mets — starting with Helsley — that the A/V team might want to cool it for the foreseeable future? Helsley put up a clean inning, but don’t be fooled: He left too many pitches in the middle of the plate and was bailed out by Marlins missing pitches and some solid defense.

Come the eighth inning and things got truly ridiculous: The Marlins sent second baseman Javier Sanoja to the mound to get hammered, with Luis Torrens‘ three-run drive just inside the left-field pole giving every member of the starting lineup a hit. The Mets countered by sending Torrens out there for the ninth with a 19-5 lead; after Torrens gave up back-to-back homers, a single and an RBI triple, Mendoza popped out of the dugout, perhaps wiping some egg off his face, to summon Ryne Stanek.

(Would you like to be the reliever called upon after a position player? No, you would not.)

At this point, we all had the equivalent of an ice-cream headache: The game had gone on far too long and degenerated from joyous to mildly diverting to embarrassing. Because baseball is endlessly perverse, Stanek looked better than he had in weeks, needing just eight pitches to fan Eric Wagaman and Wiemer and send the Mets into the dugout with a 19-9 win while baseball brains (led by Greg, whom I emailed as soon as I got to the subway) pored over the first-times and assorted oddities.

Such as the most runs the Mets had ever scored in a home game. Such as a unicorn score — the Mets had never won by a 19-9 margin. (The 17-3 final line for Pelfrey’s debut was also a unicorn score, BTW.) Such as Torrens becoming the first Mets position player to toe the rubber in a win.

Years from now, it’ll be interesting to see what we remember from Tong’s debut. Maybe it will be that ungodly curve and riding fastball, now familiar qualities that we were then seeing for the first time. Maybe it will be the weird cameos from guys we think of as wearing other uniforms. (“Oof, Ryan Helsley — boy did that not work out.”) Maybe it will be the zaniness of everything else that transpired on a lovely summer night at Citi Field.

For now, though, I think it will be a bit of a relief to see what David Peterson and Edward Cabrera get up to in a few hours. Let’s play a normal one, OK fellas?

by Greg Prince on 29 August 2025 8:17 am The carnival left town and the circus arrived hot on its heels. From fun and festive and knocking down the Phillies to win valuable prizes, to foolish and floundering and getting spritzed by the Marlins, your New York Mets stumbled to a 7-4 loss Thursday night.

Three-run defeat? Seemed like more.

Three errors committed? Seemed like a lot more.

Multiple chances to get back to a lead or tie? Couldn’t have done less with them.

Only one night after the rotation’s cool older brother (in demeanor if not age) Nolan McLean served as ringmaster for a Met jamboree of momentum and vibes, capping off a three-game sweep and picking up three games on first place? Everything going great couldn’t have seemed less recent once the Mets opted to play their version of kickball rather than baseball, kicking the ball hither and yon, allowing five unearned runs. But it really was only a difference of 24 hours between all going right and fundamentals going to hell. Every night is a new story. Recurring similarities are incidental and perhaps accidental.

Already a coming attraction. Just one game? Yes. It’s always just one game. This team defies trends and trajectories. Best to buckle up for the next just one game. It will feature the major league debut of Jonah Tong. Tong, 22, wasn’t expected in New York this quickly. Based on performance and need, it appears he won’t take the mound a moment too soon.

Throw a tent over the last one. Clear the field for the next one. Back to fun. Back to festive. Back to baseball rather than kickball.

by Jason Fry on 28 August 2025 3:26 am “My Girl” you know about — the singalong that accompanies Francisco Lindor‘s ABs is a new tradition that’s all the sweeter for its organic origins and the Mets having sense enough to stay out of the way.

But the crowd at Citi Field wasn’t satisfied with augmenting the Temptations. They did the honors on “Take Me Out to the Ballgame,” accompanied by Muppets as it was Sesame Street Night. They sang rapturously along with “Dancing Queen,” the winner of the karaoke contest. They even burst detectably into song when a bit of the Killers’ “Mr. Brightside” popped up between innings.

And they sang the praises of Nolan McLean — toward the end of his eye-opening performance, of course, but also from the very beginning of his labors. They clapped in a rising cadence when McLean got to two strikes. They cried out in disappointment when a close call didn’t go his way. And they roared when he dispatched yet another Phillie batter, either via strikeout (six of them) or a sharp play made behind him.

I’ll spare you a scouting report from the 300 level beyond what I saw as part of the boisterous crowd: McLean filling up the strike zone and changing speeds with a maturity far beyond what his decidedly short resume would suggest. It was remarkable to see hitters of the caliber of Trea Turner, Kyle Schwarber and Bryce Harper rearing up in the batter’s box, frustrated by their inability to figure McLean out — Turner and Harper were both sufficiently befuddled that their bats wound up helicoptering away from the plate, perhaps in wooden surrender. And McLean’s pitch count kept us doing double takes — only in the last couple of innings did it climb to expected levels, as he tired and lost a little precision and zip.

Only a little, though — McLean’s eighth had the crowd in a frenzy, trying to will him through the frame after crybaby Alec Bohm singled with nobody out and Max Kepler moved him to third with a single of his own. They roared when Juan Soto caught a Nick Castellanos fly and uncorked a missile to the plate, keeping Bohm at third tete-a-teteing with Dusty Wathan. They roared again when Bryson Stott flied out to left and Brandon Nimmo let fly with a Thou Shalt Not throw of his own. And they exploded when Harrison Bader hit a little tapper to McLean, who tossed it to Pete Alonso at first to complete eight innings of stellar work.

(BTW, Stott’s walkup music in Philly is the earworm “AOK” by Tai Verdes, and you could hear Phillies fans singing it for him during his ABs. Like I said, a musical night!)

By the eighth the anxiety had left the stadium, letting us cheer McLean for his own sake. The Mets put together three runs in the third with five straight hits off old friend Taijuan Walker, added another in the fifth on a Mark Vientos RBI single, and made things academic in the seventh when Vientos hit a bolt of a home run off Tanner Banks.

Citi Field has been a house of horrors for the Phils — they’ve now lost their last 10 here — and the Mets did them no favors by playing one of their better games of the season: The defense was crisp, with Alonso starting a nifty 3-6-3 double play in the second and Jeff McNeil making a leaping grab above the fence in center, and the hitters looked loose and aggressive all night.

A three-game sweep, a rookie on top of the world, and one of the best crowds I’ve even been a part of at Citi Field. Kind of makes you want to burst into song all over again.

by Jason Fry on 27 August 2025 8:17 am “Show a little faith! There’s magic in the night!”

That’s one of Bruce Springsteen’s best-known exhortations, a commandment for wavering lovers, teetering dreamers and yes, fans of oddly underwhelming baseball fans. But until Tuesday night, it had largely fallen flat where the 2025 Mets were concerned.

Until Tuesday night, but not forever.

Game two of the seven-game, two-city Ragnarok starring this year’s Mets and the Phillies started off borrowing narrative pieces of recent vintage.

For openers (a tactic the Mets have tried, mostly to little effect), there was a Met starter looking good early and then winding up on the side of the road awaiting a tow: In this case it was Sean Manaea, who looked better than he had all year pitching aggressively and mixing in his mostly absent change to excellent effect, only to falter in the fifth, chased from the game by a two-out Trea Turner single. Enter Gregory Soto, whom one may damn with faint praise as the best of the Mets’ deadline acquisitions so far; Soto threw a wild pitch, walked Kyle Schwarber and then watched helplessly as Bryce Harper served a sinker over the infield for a 2-0 Phillies lead.

The Mets then borrowed a page from Monday night’s book. Jesus Luzardo had bent a little in the early innings but not broken, holding the Mets at bay while making no secret of his pique at perceived enemies including Juan Soto and young home-plate umpire Willie Traynor. The bottom of the fifth, though, started off in a way that demanded the pique be self-directed: Ahead 0-2 on Luis Torrens, Luzardo gave the Mets a gift by hitting their catcher in the foot.

Luzardo then imploded, surrendering a single to Francisco Lindor, an RBI single to Soto (with Lindor scampering to third and Soto to second on an ill-advised throw in the vague vicinity of home by old friend Harrison Bader), and walking Starling Marte — or, as Luzardo saw it, striking out Marte on two consecutive four-seamers that ticked the strike zone to the satisfaction of everyone except Traynor.

Exit Luzardo, with some parting words that earned him a post-removal ejection from Traynor and a mildly hilarious double unavailability for the rest of the game, enter Orion Kerkering, AKA the Ryan Helsley of the Phillies. When the Mets first saw Kerkering a couple of years ago, I appraised his fearsome fastball and evil slider and thought, “My God, this guy is going to torture us for years.” But something has gone amiss with Kerkering since then, or at least it has when he faces the Mets. He had no feel for the sweeper, and was undone by a ringing double from Pete Alonso, an RBI single following a long AB from Mark Vientos, and a sac fly from Brandon Nimmo.

Just like that it was 5-2 Mets, and the only problem was the Mets had to figure out how to secure 12 outs.

Maybe they’d keep following Monday night’s script, getting perfect relief while pouring on the runs? Nope, guess again: Huascar Brazoban couldn’t command any of his pitches and surrendered a run to bring the Phillies within two; meanwhile, the Mets offense browned out. Tyler Rogers worked a fuss-free seventh (a good sign) but when the eighth rolled around Carlos Mendoza turned, to my horror, to Helsley.

What, exactly, is wrong with Helsley? The Mets think he’s tipping his pitches; amateur observers who watch closely have noted that his fastball, while intimidating, is pretty much wrinkle-free. All I know is that he’s arrived and looked like the bastard child of Rich Rodriguez and Mike Maddux, and that Mendoza continues to stubbornly follow David Stearns’ blueprint by insisting Helsley is the bridge to Edwin Diaz and not a collapsed span lying in a river full of upside-down cars. Helsley actually fanned Alec Bohm, to the delight of Mets fans who tormented Monday night’s crybaby with signs about parabolic mikes and even some ingenious ginned-up lookalikes. (Bohm was 2 for 4, though, so doesn’t seem to have been particularly bothered.) But Helsley then walked Nick Castellanos (mysteriously replaced with an annoying clone who could actually play defense) and offered Bader a middle-middle four-seamer which the former Met lashed into the left-field stands to tie the game.

Helsley was left in to walk Bryson Stott before Mendoza finally decided the experiment had failed again and removed him in favor of Edwin Diaz. Such situations haven’t always showcased Diaz’s strengths, to put it diplomatically, but this time out he turned in his best performance of the year. He studiously ignored Stott as he stole second and then third (yikes), but fanned Brandon Marsh and Turner to keep the game tied, then kept Schwarber, Harper and J.T. Realmuto at bay in an electric ninth.

That led to the Mets digging in against Jhoan Duran, he of the 100+ MPH heater and deadly 98 MPH splitter. But it wasn’t a night for hulking relievers with intimidating arsenals, apparently: The bottom of the ninth was fast and furious, thoroughly unexpected and utterly wonderful.

Marte spanked Duran’s second pitch to center for a single. Alonso hooked his third pitch past Turner for another single. Up came Brett Baty, with Duran putting aside the splitter and trying to get Baty out on 100+ at the top of the strike zone. In his postgame interview, Nimmo showed both a discerning eye and admirable leadership by reminding the jubilant crowd how that’s a spot where a young guy can try to do too much and praising Baty for resisting the urge and just trying to make contact.

Which Baty did … barely. He dropped a little parachute over the infield, a nightmare for both the Philadelphia defenders and New York base runners. Marte and Alonso arrived safely at the next bases, Baty took first, and Nimmo rifled a 2-0 fastball through the infield for a Mets win. As it turned out, Duran never so much as recorded an out.

Show a little faith indeed — but remember that magic follows its own stubborn timetable.

by Greg Prince on 26 August 2025 12:17 pm Some nights, you just know. On Monday night, I just knew the Mets were headed to defeat as they fell behind almost immediately, which is to say some nights, you just think you know.

I thought and knew it didn’t look good as Kodai Senga endured his customary first-inning struggles, and not even the redoubtable glove of Tyrone Taylor, installed in center a day after it might have done the most good, could catch up to Trea Turner’s sinking liner that became a triple. Kyle Schwarber, with a well-placed grounder rather than a characteristic out-of-sight homer, turned that into a 1-0 lead, and in the top of the third at Citi Field, the Phillies were finding more ways to nettle the scuffling Senga. With two out, Alec Bohm singled home two runs. The next batter, Brandon Marsh, doubled into the right field corner. Juan Soto didn’t handle it cleanly, and in the scoreboard of my mind, I’d already revised the tally to Philadelphia 4 New York 0, the Mets drifting into divisional oblivion and holding on for dear Wild Card life.

Except Bohm, who could have easily scored, was held up at third by his coach, Dusty Wathan. Did I have any idea who the third base coach of the Philadelphia Phillies was before his hand went up? Absolutely not, because as we established a few weeks ago, you don’t notice most coaches, not even your own, until they do something that results in an out or a missed opportunity. It was only the third inning, but Wathan and the Phillies had just done Kodai a massive favor. They refrained from taking a run that was right there in front of them. Such gentlemen!

At that moment, or maybe the moment Senga flied out Max Kepler to end the inning and strand Bohm where Wathan halted his progress, I just knew (or perhaps thought hard) that the Phillies would regret it. Sure enough — and there isn’t a lot of “sure enough” to the 2025 Mets — the Mets rose from down 0-3 to, bit by bit, tie, lead, and squash the Phils, rendering Cristopher Sanchez’s early dominance into a footnote. The final score wound up New York 13 Philadelphia 3. I didn’t know the Mets would win by a ton. I didn’t know the Phillies’ lumber would fall into slumber, not at all touching five Met relievers over five innings. I sure as hell didn’t know that in the visitors’ fifth, Bohm would have problems with a parabolic microphone’s positioning, tucked as it was in the lower right corner of the center field batter’s eye…or, to be honest, that the thing that looks like a miniature satellite dish is called a parabolic microphone. The umps ordered the item moved, a process that required fourteen minutes, all so the next batter, Marsh, could have an unobstructed line of sight to ground out on the very next pitch Jose Castillo was finally permitted to throw. Castillo became the pitcher of record once the Mets took a 4-3 lead in the bottom of the fifth. The pouring on of Met runs assured he’d be credited with his first major league win in seven years, a wait that I suppose made fourteen minutes of standing around and staying warm tolerable.

Oh, you could tolerate these Mets every night if you could get them on a regular basis. Mark Vientos and Jeff McNeil are still steaming at the plate. Luis Torrens knocked in five runs. Taylor didn’t catch that Turner triple, but he did collect three hits, walk once, and never make you think, “Gee, I’m glad the Mets went out and traded for Cedric Mullins.” While Reed Garrett went on the IL, thus explaining Castillo’s sudden presence, all the more or less regulars who’d been nursing aches and pains were back in the lineup, and even Francisco Alvarez took some BP. Not that Alvy’s availability was a press concerning after Torrens went deep to hoist the Mets’ run total into double-digit territory.

All problems were not solved Monday night, but the Mets who win ballgames proved preferable to the Mets who lose ballgames. They’re the same team, but we so want to believe the version that scores thirteen unanswered runs isn’t the same version whose starting pitcher couldn’t make it out of the fifth, nor the same version whose Biggest Three — Lindor, Soto, Alonso — goes 2-for-14 amid an offensive onslaught. More than enough cylinders were firing in Flushing. We may not get many nights when the engine purrs exactly as we wish. We’ll certainly take the games when more goes right than wrong.

After Sunday’s grumbly affair, I stumbled into something of a state of Met Zen. Win ballgames and make the playoffs was my new mantra. And if the Mets don’t win the ballgames it will take to make the playoffs, then it won’t happen, can’t worry about what I can’t control. It’s probably as healthy an attitude as a Mets fan can take given how this team has played, never mind that much of the fun of being a fan is thinking you or your actions possess a wisp of control over the actions of others that you decided long ago would define your mood on a going basis. Then they roused to life Monday, overcame their shortcomings, and blew away the team in front of them in the NL East standings. Win ballgames and make the playoffs still made sense to me, but now I was less at peace about letting it be should the alternative come to pass. If you can win a ballgame like that, why can’t you win ballgames more often than you do? Huh? HUH?

So much for Met Zen.

by Jason Fry on 25 August 2025 7:43 am It’s a basic rule that you cannot, in fact, win ’em all.

It’s also a common error as a baseball fan to forget this bedrock truth.

It sure felt like the Mets would win ’em all, or at least this next quantum in the set, when Mark Vientos blasted an early two-run homer off Bryce Elder to give David Peterson and the Mets a lead Sunday afternoon.

Surely the Mets would pour it on as they had the last two days, tormenting various Atlanta relievers and leaving us to wonder where, exactly, this exceptional play had been for much of the summer.

Surely Vientos — the most essential Met for the rest of the season — would stay on his recent heater for the rest of the year, lengthening the lineup as he did in 2024.

Surely Peterson would keep being the rock of the rotation, taking pressure off a still-evolving bullpen and maybe even inspiring his fellow starters.

Which delivered us to the doorstep of another common fan error: mistaking a short distance for a clear view.

This topsy-turvy, stop-start Mets season has been bad for not only our mental health but also our predictive powers, as the Mets have been reliable only when it comes to being confounding.

And so it was again: A ninth-inning flurry notwithstanding, the Mets stopped hitting. Peterson got into the sixth but found the last out elusive, departing having lost the lead. The relief faltered, with Gregory Soto hitting Vidal Brujan and giving up a two-run single to Jurickson Profar, long ago the subject of near-constant Mets trade gossip and now one of those guys who’s quietly been around forever and turns up each season on a new team. The defense didn’t get it done, as Profar’s single plopped down in front of Cedric Mullins and spurred questions about why, exactly, he was playing center instead of Tyrone Taylor.

Would Taylor have made the catch? That’s a three-in-the-morning question in a season that’s been full of them, no doubt with more to come. He didn’t, in answer to the larger question the Mets didn’t, and rather than make ourselves crazier perhaps we should draw a curtain on this one with a shrug and remind each other that you cannot, in fact, win ’em all.

by Greg Prince on 24 August 2025 11:25 am Clay Holmes pitched into the seventh inning Saturday night and pitched well. Just three hits and two walks allowed. If Clay wasn’t showing the transcendent stuff of Nolan McLean from Friday night, he came close enough; going deep and being effective must be contagious. Relievers Gregory Soto, Tyler Rogers, and Edwin Diaz stoked no tension in their two-and-two thirds. It’s only fair to shout out the bullpen when the bullpen isn’t making us scream.

Many a Met defended well Saturday night. Tyrone Taylor, whose presence in center field could be described as sorely missed once you were reminded what presence he has, did to Michael Harris what Ron Swoboda did to Brooks Robinson in diving, backhand, you gotta be kidding me, he actually caught it? fashion. Lesser stakes than 1969, similar degree of difficulty. Brett Baty was Brooks-ish with the glove on a couple of potentially tricky plays in the vicinity of third base. And Starling Marte, not your everyday left fielder, made the kind of throw home to gobble up Nacho Alvarez that you’ll take every day of the week and twice on a Saturday night.

Marte was one of several Mets who smacked the stitches off of baseballs during this same festival of Met capability. Starling homered. Pete Alonso homered. Jeff McNeil and Mark Vientos homered twice apiece. That’s a lot of homers, which explains why the Mets scored a lot of runs in their resounding 9-2 victory at Truist Park.

So there’s no doubt, that’s their resounding 9-2 victory at Truist Park over the Braves, which made the entire effort a spectacular Saturday night, for though we are huffing and puffing to keep up with the Phillies (who we trail by six) and attempting to fend off the Reds (who we lead by two-and-a-half), it is the Braves among all National League opponents I most enjoy watching flail. Until Rob Manfred gets his grubby hands on realignment, this is my default all-things-being-equal selection, and it’s possible I’ll stick with it should Atlanta move to some mythical Selig Conference South. The Braves aren’t anywhere near a playoff race as August grows late, yet I still instinctively prefer their losses to those of anybody else in our realm, as long as those losses a) aren’t against the Yankees — hey, I never asked for Interleague play — and b) don’t screw anything up for us…and even in the latter case, specifically as regards their upcoming series against the Phillies, I will have to overcome my hard-earned, deeply ingrained antipathetic instincts toward Atlanta to remember I should want them to win.

When this season began, it seemed essential that the Mets beat out the Braves. As this season has proceeded, the Mets leading the Braves has proven incidental to our larger ambitions. But after the bulk of these past three decades, don’t think it’s not also a delicious bonus.

In the Seventies, I would have said the Cubs were the intramural rival I always wanted to see lose, regardless of won-lost column reverberations. In the Eighties, my NL East wrath transferred to the Cardinals. For too long since, my active — sometimes simmering, sometimes boiling — animus has been directed at the Braves. The Phillies have risen and fallen and risen again to the top of our five-team ranks. The Nationals held divisional sway somewhere in between. I’ve mostly wanted those teams to lose when I’ve needed those teams to lose. It was situational. But I always want the Braves to lose, need hardly being a necessity. It’s been personal.

Envious, spiteful, bitter resentment got my goat and kept tight hold of it? Sure! I don’t believe I must gin up a healthier reason for disdain in a sports sense. They won more than we did over and over again, often in our faces and at our direct expense. That’s plenty reason for grudge maintenance in my book. Everything else is details.

Having established themselves as Beasts of the West in the early 1990s, the Atlanta Braves entered the National League East in 1994 and were solidly in second place the night the lights went out on baseball. They probably weren’t going to catch the Montreal Expos of questionably sainted memory to win the division (they trailed them by six games as of the strike), but you wouldn’t have put it past them. They were certainly in pretty good shape for the brand new Wild Card. The Braves were the Braves even then, which has meant one thing to Mets fans ever since: we were compelled to look up at them.

When the strike was settled in 1995, the Braves went about winning the East. They did the same thing in 1996. Rinse and repeat clear through to 2005. By definition, they finished ahead of everybody in the division for eleven consecutive years, “everybody” encompassing the Mets. Going back to ’94, they’d finished ahead of us all dozen seasons we’d been jumbled together in company with them, Philly, Florida, and Montreal/Washington. A few of those years we finished close enough to them that not finishing ahead of them produced pain that still resounds in the soul. So, yeah, I like when the Braves lose.

Over the three years following 2005, we finished ahead of them, hallelujah. Once it came with tangible reward, the 2006 NL East title, won in a one-team race. The Braves were not a factor. In 2007 and 2008, we infamously did not win the division, falling short late, but at least we didn’t fall short to the Braves. Not that falling short to whom we fell short was much of a consolation prize in the moment, but for our purposes at this moment, it was something. It was the last time for another seven years that the Mets finished ahead of the Braves.

From 2009 through 2014, the retooled Braves — capturing one division title and two Wild Cards — had their moments. The Mets had few, none that included finishing ahead of the Braves. Our crowning standings-related achievement came at the end of that final season, in ’14, when we tied the Braves for second place. They weren’t close to first, which is to say we weren’t close to first, but at least we didn’t have to look up at them. Perhaps looking across at them, with our identical 79-83 records impressing nobody who wasn’t paying close attention, set the stage for our accomplishments in 2015 and 2016. We went to the playoffs twice and they disappeared from the contending map. The Mets came in ahead of the Braves in each of those years. Those are what are known in Met circles as good years. Rare years, but good years.

And that’s been it since we’ve shared a sector. The Mets have finished in front of the Braves exactly five times between 1994 and 2024. There was that self-esteem tie in 2014, plus two other knottings with actual implications, in 2022 and 2024. In 2022, we each won 101 games, but they won the division (their fifth of six straight) on a newly invoked tiebreaker. That rather sucked. In 2024, we each won 89 games and they were rewarded with a higher seed in the same postseason to which we both gained entry. It will be recalled we stunned the Braves in Game 161 to get what we needed, so we convinced ourselves to not much care if they beat us in Game 162 to get what they needed, which they did. But then they disappeared without a Wild Card Series trace and we enjoyed one of those rides of a lifetime runs (we’ve had several) for a couple of weeks. That rather ruled.

I don’t know if our experientially different doubleheader on September 30, 2024, set the stage for what lay ahead, but while we’ve been up and down and are hopefully on our way back up in 2025, they’ve been nothing but down. You wouldn’t necessarily know it from the previous three series the Mets have played versus the Braves this year, but the Braves have been down as hell, and I am so there for it. After Saturday night’s 9-2 romp north of Atlanta, which came on the heels of Friday’s 12-7 thumping, we have built an eleven-game lead over them. The Miami Marlins are a buffer between us and them. It’s a beautiful thing not actively worrying about what the Braves are doing or seethingly resenting what the Braves are doing. I’ve been absolutely loving what the Braves are doing. The Braves are losing like they haven’t lost in ages. They are losing so much that, barring a catastrophe of epic proportions on our side (we’ve had several) and a 33-game resurrection for which scriptures would require rewriting on their side, we will finish ahead of them. At the close of 2025, we will look down on the Braves the way we did in 2006, 2007, 2008, 2015, and 2016 and no other time in modern National League East history.

As manager of the defending league champion New York Giants, Bill Terry needled the downtrodden Dodgers by asking reporters if Brooklyn was still in the league, and lived to regret it when the Dodgers pulled together enough gumption to become spoilers of the Giants’ pennant chances at the end of 1934. Bums skipper Chuck Dressen declared in the summer of 1951, “the Giants is dead,” yet it was his Dodgers who died at the hand of those Giants come the afternoon of October 3. It’s always dangerous for rivals to cackle too soon over the fate of rivals. We have one game left versus Atlanta. It is today. It would be handy to win. It won’t make or break us either way. We’ve lost in dumb and inexplicable fashion to too many other teams to attribute any pending Met demise to the last National League team we traditionally wish to rile up.

For once, I’m throwing caution to the winds of Windy Hill, risking overcharging the Battery, and choosing to conveniently forget that during the sixth game of the 1999 National League Championship Series I spent innings in my Long Island living room singing hosannas to Joneses named Andruw and Larry so they would let their guard down some 900 miles away (because in addition to their top-tier baseball skills, they apparently possessed excellent hearing). The 2025 Braves are headed to their competitive grave, and I’ll be damned if I don’t take at least one moment to figuratively dance on it. Come on, baby, let’s do the Twist, do the Hustle, do whatever dances young people do in the twenty-first century. Just be sure to do it wherever the Braves are buried, which is currently a very distant fourth place in the NL East.

|

|