The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 31 March 2023 2:29 am Baseball’s nothing without poetic license, whether or not Rob Manfred wishes to notarize said document. The Commissioner is intent on engineering a game built for speed. Get it over with already yet seemed the Manfred mandate for Opening Day. Start the pitch timer, throw the ball, quit yer lollygagging. It sounds reasonable in concept. It felt forced in practice. So I don’t know if the elapsed time of the Opening Day contest in Miami between the Mets and Marlins of 2:42 would meet with the heartiest of official approval, considering Time of Game in various other venues Thursday measured 2:38, 2:33, 2:32, 2:30, 2:21 and 2:14, but when you step back and realize 2:42 adds up to 162 minutes accumulated in service to the resolution of the first of 162 games, well, how can you not get a numerical chill?

It helps when your team wins. Our team won: 5-3 to be exact. And, at the risk of having my poetic license revoked, what’s the diff how long a Mets win takes as long as it’s a Mets win? As long as it’s a Mets Opening Day win? The Mets, you might reflexively note, ALWAYS win on Opening Day regardless of length or site. Having soaked in a fourteen-inning Opening Day triumph on this very date 25 years ago, I’m tempted to believe the former, but my fealty to accuracy at the expense of burnishing Metropolitan mythology compels me to report that until 2023, the Mets were more futile than not when beginning a year in Florida. The Mets thrice previously visited the Marlins to lead off their campaign, in 1999, 2008 and 2011, and won only the middle game, Johan Santana’s debut. One-hundred sixty-two minutes devoted to defeating these Fish in their own pond to go 1-0 should be treasured…as if we’d take anything about beating the Marlins in any facility on any day for granted.

If you listened closely to the ambient noise on Thursday, you could hear the pitch clock tick. Things moved so swiftly for the first five innings that I was convinced the entire aim of a baseball game is to complete it as quickly as possible. You’d think a matchup pitting Max Scherzer and Sandy Alcantara would be ripe for savoring, yet you can’t gripe when two such polished pitchers are brisk in their approach, no matter that their pace is nudged along by an obtrusive digital countdown. It only felt like the goal of the game was to end it so people who find baseball a drag will be less bothered that it lasts as long as it does. Over those five innings, though, despite the dual mound presence of reigning Cy Young awardee Alcantara and three-time recipient Scherzer, the personages were overshadowed by the pace. Wasn’t it great how fast the thing for which waited all winter to finally get here was escaping into the ether with uncommon alacrity?

Yeah, we guess.

The only run registered across those first five frames was generated by foot. In the best tradition of the Reyes Run and the Rickey Run, we were treated to the Vogelrun. Daniel Vogelbach turned a walk into a score by darting from first to third on Omar Narvaez’s single to right, and third to home on Brandon Nimmo’s sufficiently deep fly to left. I don’t know if the slightly large bases abetted Vogey’s deceptive nimble nature. Perhaps every little inch helps.

Alcantara vs. Scherzer would have loomed as fascinating without somebody constantly resetting a counter and demanding something happen in 20 seconds or not happen at all. The last time before 2023 that the Mets faced a starter on the Opening Day directly after that starter collected a Cy was forty years before, at Shea Stadium in 1983. The opponent on that occasion was Steve Carlton, bested by a Met team led by prodigal immortal Tom Seaver. Plenty of Cys and sighs in evidence that afternoon.

Scherzer had an intriguing precedent going for him as well. Max was the “enemy” on Opening Day 2015, and now he was our guy. Had that ever happened before? Why, yes, once. In 2001, the Mets played their first game of the year at Atlanta. The starter for the Braves was T#m Gl@v!ne. In two years’ time, said lefty would switch sides for a fee and be the Mets’ Opening Day starter, an assignment he’d assume three of the next four Openers.

Excuse me while I wash my fingers out with soap for typing up any link between the mostly revered Scherzer and the mostly reviled Gl@v!ne. Then again, I have to confess that when I first saw Scherzer loosening up in St. Lucie following the lockout the Spring before this one, I involuntarily formulated an unpleasant thought:

“I hope this guy isn’t another Gl@v!ne.”

I wasn’t thinking a surefire Hall of Famer who will help the Mets to a postseason and polish his lifetime totals in the process, or, for that matter, someone who might implode at the absolute worst moment after gaining our trust, but a professional who, for all his credentials and maturity, emits the impression that his affiliation with this thing we love is strictly business.

Say, it appears I’m violating the spirit of the pitch clock by stepping off and pursuing a tangent. If that’s the case I might as well use my one timeout and backtrack to an admittedly ancient grudge…

At first I couldn’t stand T#m Gl@v!ne being on my team because he had been such a goddamn Brave for so long, and nobody who was a Brave a little before or a little after the turn of the millennium was someone a Mets fan was prepared to embrace unconditionally. In retrospect, what I really couldn’t stand about Gl@v!ne being on my team was the way he deigned to be a Met. Never just was a Met. Wore the uniform for five seasons, threw the ball for a thousand innings, took a hike the second it was contractually permissible, didn’t let the door hit him in the ass on the way out. It’s been twenty years since his arrival, more than fifteen since his departure. In between, once I got over my aversion to his innate Atlantaness but before the whole “disappointed, not devastated” debacle, I decided to accept him as one of ours. He wore the uniform. He threw the ball. That’s usually all it takes.

I still regret disregarding my Bravedar.

Scherzer, as ’22 progressed, did not put me in mind of Gl@v!ne whatsoever. Scherzer’s Nationals were never the blood rival Gl@v!ne’s Braves were; Max even had the decency to wait until after we clinched a division title to no-hit us in 2015. He came over to our side after a detour to Los Angeles and provided no reason for regret. Yet as ’23 commenced, I looked at Scherzer anew and still didn’t see “a Met” by instinct. Wears the uniform. Throws the ball. But in the sense of being “ours,” I just don’t feel it. You might dismiss this emphasis on feelings versus data, but I’ve already renewed my poetic license where baseball is concerned. I can only care about what I feel. On Thursday, I began my 55th season as a Mets fan. You don’t last 55 seasons without of lot of caring and a lot of feeling.

My feeling on Scherzer isn’t that he’s a mercenary in the Gl@v!nian mode but something more akin to a visiting scholar. Has his tenure. Opted for a change of scenery (and more than a little pocket change). Likes our campus well enough. Visited the school book store. Bought a couple of sweatshirts. Figures to someday look back on his years in Flushing with a degree of fondness. But we’ll never be his alma mater. As best as I can frame it, Max Scherzer is the Professor Kingsfield of our pennant chase. Our younger and less-accomplished hurlers teach themselves the strike zone, but Scherzer, à la John Houseman’s indelible crusty mentor, trains their minds. They join the staff with a skull full of mush, they enter the rotation thinking like a pitcher.

That’s pretty valuable if not wholly warm and fuzzy. Max is great to have on the Mets. I’m just not convinced he is a Met. Or maybe he’s going to help redefine what it means to be a Met despite me never shaking the notion that he’s almost an alien presence in our midst. I should add that I’m coming to terms with the idea that I’m dealing with abandonment issues where the previous Met ace is concerned, thus I imagine I’m a little wary about getting attached to any Met ace.

Oh, the last guy. I was convinced the last guy was a Met in the Seaver mold, except unlike Tom, the last guy was never going to wear anything but a Mets uniform. That ship sailed for absolute certain on Thursday while Scherzer and Alcantara were busy zipping along for five innings. That ship docked deep in the heart of Texas in December. Its passenger disembarked and put on his Rangers uniform for competitive purposes. I tried not to pay mind to who was pitching against the Phillies in Arlington, for the first time not pitching for the Mets after never pitching for anybody but the Mets.

But I noticed.

Let the record show I now live in a world where Alec Bohm takes Jacob deGrom deep and I greet the news with the sort of fiendish snicker that canine sidekick Muttley would generate when ill fate overtook the most aptly named of drivers on Wacky Races, Dick Dastardly. I also live in a world where if microwaving something for approximately 45 or 50 seconds doesn’t require exactitude, I still set the timer to :48 because the last nine seasons made me adore the sight of that number. There are a lot of unresolved pitching feelings I’m sorting these days, and we’ve played only one game.

The game! That’s right! I’m supposed to be writing about the game. So where was I?

Right, Scherzer vs. Alcantara in the accelerated present, Major League Baseball ushering in the pitch clock era as if we’ve been doing it wrong for the prior 54 or however many seasons we’ve been caring and feeling. We wanted a less schleppy game. Less stepping off. Less stepping out. Fewer commercials (cue Muttley). We hoped it would occur organically, just as we hoped more clever hitters might confound stultifying shifts.

Preaching the taking of the season one game at a time has been a personal mission for a majority of my now 55 seasons on the beat. So maybe I need to take my own advice and take this 55th season one game at a time. The clocked pitching hasn’t had three Mets game’s worth of hours to settle in. Give it, you know, time. If Manfred’s OK with that.

The sixth inning was Opening Day’s artistic salvation, which is to say I tuned into a pitch clock and a baseball game broke out. The bats were broken out just enough to get things percolating. I love a pitchers’ duel. I also love when the hitters duel back. In the top of the sixth, action found its footing. With one out, Alcantara walked Nimmo (the third of four bases on balls Sandy would issue). Starling Marte singled to converted center fielder Jazz Chisholm. Nimmo took a cue from Vogelbach and headed for third. Chisholm’s throw to third was unsuccessful enough to allow Marte to take second. The runners’ placement came in very handy when Francisco Lindor’s fly to Chisholm drove in Brandon and moved up Starling.

One more not exactly intentional walk, to Pete Alonso, followed. The corners were occupied for champion of batting Jeff McNeil. On a foul ball, Pete ran to second, then didn’t exactly hustle back to first in advance of Alcantara’s next pitch. A little game within the game tactic, the runner giving the batter an extra instant to hone his edge. Nothing unusual there.

Until 2023, that is. This year, what Alonso did elicits a penalty, because if Pete gets in the way of the clock being the star of the game, then the game isn’t moving fast enough to be over with so it can be over with, an ethos that would have fried the brain and shattered the zen of former Mets manager Lawrence Peter Berra; it’s not like William Nathaniel Showalter accepted the ruling in good humor. A strike was assessed on McNeil. Buck demanded a cogent explanation. Yogi, a classic bad ball hitter in his playing days, never had to take a strike because the runner on first’s less than zesty motion in the wake of a foul ball dissatisfied a home plate umpire probably just trying to keep up with the sport’s prevailing zeitgeist.

“Most of the strikes I had called on me,” Berra never said but probably would have, “were pitched.”

What a mess…is what one might have said had Squirrel not harnessed the bad vibes and turned them glorious with a single to the first base side of the middle that even a 2022-style shift might not have corralled. Marte trotted home rapidly enough to not irk Larry Vanover, and it was 3-0. Sandy the Cy was done for the day and Max the Sage had a cushion.

Funny thing about some cushions, especially the ones stuffed with down. They can lose their fluff in a hurry, and all you’re left with is a bunch of feathers on the floor. Scherzer, fairly untouchable for five innings, felt the slimy gills of the Marlins all over his stuff in the bottom of the sixth. Jacob Stallings doubled — you’d figure a player with “STALL” stitched on his back would be banned from an enterprise that fancies itself souped up. One out later, Luis Arraez doubled him home to cut Max’s advantage to 3-1. One out after that, a fastball to Garrett Cooper became a home run for Garrett Cooper. The battle of hardware holders morphed into a draw, with Scherzer and Alcantara each having given up three runs.

The combined storylines of the Cy corps and the clock cops faded in the seventh as the relatively familiar mechanics of bullpen vs. bullpen took shape. The Marlins brought out Tanner Scott. Scott’s appearance was to the liking of the following fellows:

• Eduardo Escobar, who singled with one out.

• Narvaez, who walked.

• Nimmo, who sloughed off barely playing during Spring Training, by connecting for a double past miscast center fielder Chisholm.

Jazz used to be a second baseman. Every Marlin used to be a second baseman, yet for all the rule-tinkering, you can still use only one Marlin at second base. While Chisholm chased Brandon’s ball toward the outer reaches of whatever Marlins Park insists on calling itself now, Escobar had no problem scoring and Narvaez modeled no hesitation despite personifying the slow-footed catcher archetype. Omar brought home Brandon’s third RBI all the way from first, and the Mets were up, 5-3.

The bottoms of the seventh, eighth and ninth belonged to, respectively, Drew Smith, Brooks Raley and David Robertson. I don’t mean they pitched those innings for the Mets. I mean they owned those innings and the Marlin batters who attempted to rally. The trio with brio gave up among them one hit while striking out six. The save went to Robertson. The doubts allayed were a credit to all of them. Drew was strong early last year, then injured, then not quite reliable. Raley’s a newcomer, but in emerging as the pen’s resident lefty, indicated he’s a worthy heir to a role previously inhabited by the likes of Feliciano, Byrdak and Loup. The southpaw didn’t pitch in a single exhibition game and couldn’t have looked sharper when the real thing rolled around; remind me of that next Spring when I’m tempted to put stock in a single slice of Grapefruit League scouting. As for Robertson, it was a save situation and his name wasn’t Edwin Diaz, yet that didn’t stop the veteran from doing what he’s done plenty in his own past.

The game didn’t get away toward or at the end.

Some game will.

But we’ll take it one game at a time.

The game moved along agreeably enough.

Some game won’t.

But we’ll take it one game at a time.

The game saw nobody get hurt

Alas, somebody was already hurt before the game started.

Still, we’ll take it one game at a time.

Justin Verlander, speaking of visiting scholar types whose ultimate Metsiness is TBD, pivoted from probable pitcher for both Saturday and next week’s Home Opener (there’s a reason they’re termed “probable”) to a spot on the injured list alongside Diaz, Jose Quintana and four other Met pitchers nobody was necessarily counting on in advance of the season and I won’t list them because, damn, seven pitchers on the injured list? That’ll teach us to count on anybody in advance of anything. Verlander’s situation is, we’re told, less serious than those that have beset Edwin and Jose, pitchers — like Justin — we were definitely counting on. Verlander’s issue is a teres major strain.

“Teres” means “what makes you think I have a degree in anatomy?” “Major” shouldn’t be construed as literal, given that Justin insists he could pitch with it if the playoffs were at hand. “Strain” is never good, but this one is apparently not the worst. Tylor Megill will sub in for Verlander as he subbed in for deGrom last year on Opening Night, pending any further body parts crossing our lips.

by Greg Prince on 29 March 2023 12:34 pm The doubt’s benefit will not be getting its projected workout, as Darin Ruf is no longer part of the Mets’ plans at the outset of the 2023 season. Ruf was designated for assignment on Monday. His assignment prior to that decision was to overcome universal skepticism wrought by contributing next to nothing in his two months as a Met last year and providing even less indication that anything better was in the cards this year. Ruf did not complete the assignment. He wasn’t hitting a lick in exhibition games. Buck Showalter swore Ruf was really socking that ball, hitting those home runs over the wall on some unspecified back field of St. Lucie. Somewhere, Casey Stengel winked.

I was prepared to give Ruf the benefit of the doubt based mostly on it being a new year and Darin not seeming like a bad sort from a distance (also on thinking nobody expected a damn thing out of Ray Knight in 1986 after his own Ruf as hell 1985), but goodwill born of a clean slate needs to be filled in with stats before long. Until he started to produce, if he ever did, Ruf was mostly in line to be our scapegoat. Every team has one, merited or otherwise. Even the good teams have one. At no juncture does a roster of 26 individuals have everybody accomplishing at peak efficiency. If we had 25 Mets going to the All-Star Game and Ruf was the one who wasn’t, Ruf would hear about how he was dragging us down. Fans need a target, best of times, worst of times, baseball times. Somebody else will carry the burden after the first pitch is thrown Thursday. Somebody will go 0-for-4 or 0-for-8 or suddenly be saddled with a fielding percentage below 1.000 at the worst possible instant. Somebody’s ERA will be U-G-L-Y after an outing or two. Stuck in DFA limbo, Darin Ruf will be considering his future, perhaps convinced he should have been given the benefit of the doubt in reality rather than theory. Maybe he’ll be thinking, “I really got hold of that one pitch in that ‘B’ game.” Maybe he’ll keep up on his old team, notice who screwed up, and think, “I’m glad that’s not me.”

Congratulations 1969 Cardinals, it’s in the bag. I’m glad the Mets are not a whole bunch of other teams. I detest season’s eve projections and predictions as nonsensical exercises in faux prescience — eleven of thirteen Daily News sportswriters were sure the Cardinals would repeat as NL champs in 1969; all of them agreed the 1969 Mets would not finish first — but a general sense is fine to harbor. My general sense is we have a good team that can win a lot of games and therefore win a championship. Can, not necessarily will. None of this is meant to come across as a revelation. Of course the Mets are supposed to be good in 2023. That’s what the Mets are designed to be every year in the Steve Cohen Era. In the Steve Cohen Era, the Mets don’t cling to their scapegoats and wait for the benefit of the doubt to kick in. The scapegoats are DFA’d, their contracts are paid off, and their space is taken by someone deemed more likely to contribute. In the Mets’ case, it will be Tim Locastro, a different kind of player — here to run on the bases and in the outfield rather than be expected to hit — but that jibes with the ethos of the Buck Showalter Era (so many Eras!). Buck looks for every little edge. He and the front office brain trust have deemed Locastro edgy enough to make enough of a difference in a given inning or game. One inning can add up to a win, one game can add up to a title.

I’m not looking that far ahead. I try real hard not to. In 2022, I was convinced by June the division title was in the bag and spent the next four months straining to avoid entertaining contrary possibilities. No division title appeared in October and the Mets didn’t make the most out of their fallback position. The long offseason after the short postseason seemed devoted to making the most out of the next 162 games (not every team operates that way). We, which is to say Cohen, made certain that almost every Met considered essential to winning 101 games last year stuck around unless one really, really wanted to leave, then additions were made. Maybe not every addition that was desired, but there was one that looms as enormous and a few that can be seen as potentially very helpful.

New Mets for Opening Day 2023 unless lightning strikes before 4:10 PM Thursday: Justin Verlander (he’s the enormous addition); David Robertson (bigger than we realized); Kodai Senga; Brooks Raley; John Curtiss; Omar Narvaez; Tommy Pham; the aforementioned Locastro; and Spring acquisition Dennis Santana. Santana is a pitcher we got from the Twins. The last time we got a pitcher named Santana from the Twins, it was an enormous deal. It worked out well.

That other Santana, you might recall, pitched the Mets’ first no-hitter eleven years ago. On Tuesday night, SNY showed the Mets’ second no-hitter, thrown last April by, in order, Tylor Megill; Drew Smith; Joely Rodriguez; Seth Lugo; and Edwin Diaz. Rodriguez and Lugo have moved on. Diaz is infamously on the IL. Megill, last year’s surprise Opening Night starter, is ticketed for Syracuse. Just like that, only one-fifth of our very recent no-hit corps is not around as the succeeding season opens. Neither is that no-hitter’s catcher James McCann (who absorbed some of the scapegoating that managed to elude Ruf). Ten years ago, the season after the first Mets no-hitter opened with neither Johan Santana nor Josh Thole — one injured, one traded — anywhere in sight, save for Mets Classics.

I’m not sure if this indicates pitchers and catchers who want to stick around in Flushing should avoid making the best kind of regular-season batterymate history, or it’s another example of time circling the bases at its own pace. Last week I noticed another recent pickup, Dylan Bundy, warming up wearing No. 67. Seth Lugo was No. 67 forever. He made No. 67 more than a Spring Training number. Now it belongs to Dylan Bundy. That is baseball. I also just saw that Daniel Murphy, an authentic Mets Old-Timer in 2022, has opted to traverse the comeback trail in Central Islip with the Long Island Ducks. He’ll be a teammate of Ruben Tejada, a couple of 2015 National League champions trying to keep going in the Atlantic League in 2023. Murphy turns 38 on Saturday. He thinks there’s a chance he can still hit like he did eight Octobers ago. That, too, is baseball.

Looking forward to further realignment above right field, but not taking it for granted. The Mets, meanwhile, are Rufless and ready for the new season, a season slated to start truly on time for the first time since 2019. May the start adhere to its schedule and the season encompass one Amazin’ Days after another en route to an indisputably Amazin’ Year à la those that have occurred periodically in our past. The Mets have updated the postseason banner procession above Citi Field’s right field promenade so it acknowledges first the franchise’s two world championships (the first of them from 1969, as later editions of the Daily News would confirm), then its three National League pennants (the last of them clinched when Daniel Murphy was 30 and on a roll), then all six division championships listed on one placard, then the four Wild Cards listed on another, with 2022 receiving its due therein. Seven banners covering ten Amazin’ appearances in October, not all equal in stature, but varying degrees of achievement fairly noted. Even in the Steve Cohen Era, landing in the postseason six months hence is the most you can ask hope for before April.

• First place would be swellest.

• A playoff berth might have to suffice.

• Just get there and then do something with it.

Pete Alonso has mentioned how the heightened stakes of the WBC will have him ready for this October. I’m glad he’s confident. I’m confident. But worry about March 30 versus the Marlins in Miami first and take it from there, Pete…and everybody else. Never take for granted a seventh month will be affixed to a baseball season, no matter what you’re projecting or predicting on the eve of the first month.

For the season about to be in progress, an enormous scoreboard has been installed at Citi Field to post all the zeros imported ace Verlander and incumbent ace Max Scherzer will post, along with the hits and runs that will be registered by the home team as balls fly over the right field fence that’s been pulled in to create space for that fancy “speakeasy” with the fancier price tag. If you can’t afford the membership fee to the Cadillac Club at Payson’s, there is now an eatery/drinkery called the K Korner setting up shop as the in-house saloon where all are welcome to invest and imbibe. Old-timers among the fans recognize the K Korner as a Shea homage. Old-enough timers may reflexively refer to the K Korner’s spot as McFadden’s, which hasn’t operated in several years, except as an injection point for vaccines. Citi Field is entering its fifteenth season. It’s old enough to have old-timers. Remember those impossible to reach black fences? Remember the Ebbets Club? Remember when the Wilpons owned the team and probably wouldn’t pay a Darin Ruf to simply go away?

Time just slid into home and is coming up to bat again.

It’s daybreak on a new baseball season at National League Town.

by Greg Prince on 21 March 2023 8:39 pm The Mets are opening a “speakeasy” out in right field. I think Prohibition has been over roughly 90 years, so I’m not sure why one would need to know a secret password to get in, but why quibble with a concept, especially when the name of this high rollers club is intended as an homage to someone who has long merited an homage at Citi Field?

Welcome to The Cadillac Club at Payson’s. Or welcome to the news that it exists unless you are one of its “25-30 members” and get to fill one of its “only 100 seats,” per the press release announcing its debut. I assume I’ll have a great chance to see it when Steve Gelbs leads SNY viewers on a guided tour. Otherwise, I’ll just have to be happy that Joan Payson’s name graces something that sounds pretty sweet. Joan Payson bought us a National League franchise that’s still here. The least the Mets could do is acknowledge her more strongly than they have. If an automotive sponsor has to be involved, so be it. I’m guessing Mrs. Payson rode to Shea in something more than a compact.

Getting to see and think about Mrs. Payson inevitably takes a historically minded Mets fan back to the beginning of the ballclub, when the principal owner gave her blessing to George Weiss’s plan to bring in familiar figures with whom fans were likely to identify in “I know who that is!” sense. Experience wasn’t lacking. Consider the very first lineup the Mets sported in St. Louis, 61 years ago this April 11:

Ashburn CF (first MLB game 1948)

Mantilla SS (1956)

Neal 2B (1956)

Thomas LF (1951)

Bell RF (1950)

Hodges 1B (1943)

Zimmer 3B (1954)

Landrith C (1950)

Craig P (1955)

Pretty seasoned for a first season. Not a single career among the starting nine began later than 1956. The Original Mets had been around. Wear and tear was implied when players were made available by the other NL enterprises for drafting, signing or trading purposes. Two of the Mets who got the team going, Ashburn and Hodges, are in the Hall of Fame today. But by 1962, many of those guys were already playing like museum pieces.

Another living, breathing icon in uniform, Casey Stengel, understood the veteran lineup would get him only so far. Casey didn’t wish to be underestimated because he was managing in his seventies back when that was considered irrefutably ancient, but he also understood the value of new blood pumping through the Metropolitan veins. Thus Ol’ Case devoted much of his March every March he managed the Mets touting the future in the figures he dubbed the Youth of America. If it was Spring, it was time to look ahead to the prospects who were going to make the Mets sooner or later and make the Mets’ prospects better as soon as possible.

It’s Spring. Sussing out and talking up the Youth of America is still what we do. Granted, we’re coming off a better season than Casey ever helmed in orange and blue, but we can’t be blamed for peeking around the corner of what we’ve already experienced, especially if we have up-and-comers coming up. It’s been a pretty promising month for getting a taste of those who’ve been ripening on the farm.

Mark Vientos has notched eleven RBIs. Ronny Mauricio, before being sent down, bopped four highlight-quality homers. Brett Baty, getting lots of time at third, is batting .342. Francisco Alvarez, not quite healthy when camp started, has slighter numbers, but we can then say, as we say when the veterans are stuck on the Interstate at this juncture of the calendar, it’s only Spring Training. He’s still Francisco Alvarez. He’s still highly touted. The Mets have catchers and at least half a designated hitter. Alvarez can wait.

They can all wait beyond March 30, 2023, in my instinctive judgment. Get really good at fielding or not striking out or whatever it is ya gotta work on. The kids have time. We have time. I think we do. We certainly have experience, if not far too much of it à la 1962.

Let’s write out a pretend but not altogether hypothetical lineup that we might actually see on Opening Day if Brandon Nimmo’s heart of hearts and knee and ankle are all on the same page…

Nimmo CF (first MLB game 2016)

Marte RF (2012)

Lindor SS (2015)

Alonso 1B (2019)

McNeil 2B (2018)

Canha LF (2015)

Vogelbach DH (2016)

Escobar 3B (2011)

Nido C (2017)

That’s the lineup from the last time the Mets played a non-exhibition game — the quiet denouement of last season’s Wild Card Series — and it didn’t generate much offense (one hit), but it was only the playoffs. The sample size from the rest of 2022 was a little bigger, and I’m willing to ride with the guys who hit most (if not all) of last year.

To a point. The kids are coming with the idea that they’ll budge their way into not-so-hypothetical lineups. They’ll alight when the moment is right. New blood. Budding careers. Sooner, later, eventually.

***

In the realm of experience, if you were sentient and a New Yorker on May 8, 1970, you were able to experience a sports moment you will never forget. Willis Reed was hurt. Really hurt. Basketball tends to require the use of two legs. Willis could depend on maybe one. He played Game Seven of the NBA Finals anyway. Got cortisone injected and went for it when nobody was certain he would. I was seven years old. I couldn’t believe Willis wouldn’t play. I’d just spent my first full season of engagement in any team’s fortunes believing in Willis Reed — the center, the Captain — and not believing any opponent could stop him.

Not that I thought in terms of just Willis Reed. Red Holzman didn’t align his Knicks around a single player. We had Frazier and Barnett, DeBusschere and Bradley, the Minutemen (Russell, Stallworth, Riordan) and, in stray minutes, Bowman, Hosket, May and Warren. But Willis was in the middle of it. He was the MVP of everything. He was the leader on the floor and in the locker room. From October of 1969 (after the ticker tape had been swept from Lower Broadway) to May, I was obsessed with Those Knicks like I’d never be obsessed with the Knicks or any non-Mets team again. My parents had season tickets. Some my father used for business. Some I guess he sold. Some games they went to and cheered wildly. They took my sister and me to a few games at the Garden, including one in the playoffs. What a place to be when you’re seven! They had taken us to the circus there as well. I preferred the Knicks. We listened to the home games we didn’t attend on the radio with dinner, my introduction to the velvet vocals of Brooklyn’s own Marv Albert. Road games were on Channel 9. I watched those, even the late night ones on the West Coast, even if it was a school night. Did my mother mind my staying up past midnight for basketball? Who do you think I was watching with? I didn’t get enough sleep, but I got through first grade all right.

Willis Reed, who I kept reading wasn’t really as tall as the 6’ 10” at which he was listed, was revered in our house as a giant. A friendly giant. A fierce center and a good man. The whole crew, straight through to Red’s trusty sidekick trainer Danny Whelan, felt like mishpacha — extended family, but more interesting than our cousins. Sixty wins in an 82-game schedule. The Bullets series, with Willis withstanding Wes Unseld in seven, was a lesson in confident tension. The Bullets were good, but they were from Baltimore, and I’d already seen the Orioles get taken down by the Mets and was up to speed on what happened between the Jets and the Colts. The Bucks series, which we won in five amounted to a coming out party postponed (sorry, Alcindor, not yet). Here came the glamorous Lakers of Wilt Chamberlain and Jerry West and Elgin Baylor with everything on the line. That trio was as imposing as anything. But we were led by Willis Reed, at least until Game Five and an injury that should have made handling Wilt impossible. Holzman had other notions. He wouldn’t have been the coach he was if he didn’t know how to adjust. He deployed DeBusschere, the prototype of a power forward, to stay on the Stilt, and it worked. The Knicks took a 3-2 lead. The next game, the Knicks missed Willis like crazy. Thus, Game Seven.

We hung on bulletins indicating whether Willis was going to be well enough to take the court that fateful Friday night. My mother had to talk me down from my high anxiety that this wonderful team we had watched race to a 23-1 start in the fall might somehow not be the champions. If the Lakers win, she suggested, they’ll have deserved it. They’re a good team, too. All the advice my mother tried to impart to me in the next twenty years of her life, and those are the words of wisdom that I return to most often. When the Mets or any team I root hard for faces a big game, I try to remind myself that there’s another team on the other side, and they are not to be disregarded. It doesn’t always soothe me.

Mostly, I believed Willis was going to play, because Willis seemed incapable of letting us down. Sure enough, Marv told us as we started dinner (home game, therefore blacked out locally, and my father chose not to invest in finals tickets), “Here comes Willis Reed!” Willis would play, Willis would start, Willis would sink two jumpers — on one good leg — and the Knicks were about to revert to form, which is to say the Knicks who won eighteen in a row in October and November. With Clyde turning in the most low-key immortal performance in any Game Seven ever (just 36 points and 19 assists), the Knicks quashed the Lakers. Willis didn’t have to do much more than show up. The game felt won the instant his presence was announced. He and that team were destiny personified.

Those Knicks would just miss making the finals the next spring; go the championship round and lose to the Lakers the spring after that; and then take one more trophy the next spring, in 1973. My parents dropped the season tickets in 1970-71 and 1971-72, but signed up all over again for 1972-73. I got to go to a bunch of games during the regular season and a game in every round that year, including the finals. I was at the Garden for the legendary double-OT Easter Sunday win over the Celtics. It was legend before it was over. My father pounded a tile out of the ceiling over our seats. I’d be telling that story forever after.

There was one more go-round for Those Knicks, but it was obvious to all — including this by now experienced eleven-year-old — that they didn’t have much left. The Celtics took care of them pretty easily in the conference finals. Willis, who had trouble staying in one piece after the first championship, retired. So did DeBusschere and Jerry Lucas, who, like Earl Monroe, brought shimmering individual credentials to Holzman’s Knicks and blended in beautifully. I remained a Knicks fan in the sense that I didn’t become a fan of any other NBA team — the Nets were still in the ABA — but I never cared as much as I did when Willis stood tall in the middle of everything, gradually reducing my rooting interest to sporadic, then non-existent. Something in my heart of hearts told me accept no substitutes.

But, boy, did I love Those Knicks and did I love Willis Reed and did I love sharing him and them with my mom and dad. I read the statistics in the paper, and got that Willis was great. But Dad filled me in on what made Willis great beyond points scored and how Willis made everybody around him better. So did Clyde. So did DeBusschere and Bradley and Barnett and everybody else. That’s the kind of basketball Holzman preached. That’s the kind of team it was. When I learned on Tuesday that Willis Reed died at the age of 80, I at the age of 60 understood it. The seven-year-old version of me only believes that Willis is there when we need him.

by Greg Prince on 20 March 2023 5:17 pm Brandon Nimmo is “week to week” with whatever he did to his right knee and ankle this past Friday night in yet another game that counted only as much you wish it to. The Mets termed it a low-grade sprain. Nimmo, newly signed for eight years, isn’t interested in timetables or diagnoses that indicate anything less than “leading off and playing center field, number nine, Brandon Nimmo” will echo throughout formerly Marlins Park on Thursday March 30 and everywhere else clear to the end of 2030. He’s got “a best-case scenario” going for him, he’s convinced, despite the slide into second that had him limping off the field and all of us dragging a hand down our collective face following the second OMG/WTF moment in about 48 hours. He’s respectfully dismissing the company line Billy Eppler delivered and is instead taking it “day to day,” insisting he felt better Sunday than he did Saturday. He’s consulting with his “heart of hearts” and believing he’ll be “ready for Opening Day,” or at least is “not ruling anything out right now”.

Grin and bear another injury. For such conditional silver lining mining of the clouds over Port St. Lucie, pending, of course, what the doctors have to say on the matter, Brandon Nimmo is my co-player of the year before it begins, sharing never-too-soon honors with Edwin Diaz, who told Eppler in the dark hour the Mets weren’t expecting to arrive on March 15, “Don’t worry. This is going to be fine.” Once the year begins, we’ll start fresh, but that type of attitude registers as a welcome antidote to whatever the rest of us are thinking every time anything befalls a Met…or any time anything might possibly befall a Met. When it was reported in passing on social media over the weekend that Max Scherzer would be hosting a “crawfish boil” for his teammates (I put the event in quotes lest you think I have any idea what a crawfish boil is), I’d say approximately every third Mets fan comment posted in response veered to wondering how many starts Scherzer would miss from burning his tongue on main dish.

Is March a little too early for Pessimism, Skepticism, Cynicism and Fatalism — the Four Horsemen of the Metspocalyspe — to be out and about? With Steve Cohen sending a veritable TLC staff to Diaz’s house to make sure his recovery proceeds apace and, more to the point, capable of doing and willing to do whatever it takes to not let a couple of injuries to a couple of crucial players derail the projected Mets Express? With shreds of evidence suggesting maybe Edwin won’t necessarily be out all of 2023? Perhaps it’s just the painkillers talking when “a person close to Diaz” tells The Athletic, “There is some optimism” on behalf of Edwin’s surgically repaired patellar tendon (and the rest of Sugar) returning to action while there’s still some championship baseball to be contested. I wouldn’t take that to whichever gambling consortium will be carpetbombing its commercials all over Mets telecasts, but it’s a pleasant enough thought. You lose Diaz for the foreseeable future, and Nimmo for an unspecified number of weeks, and Quintana to a tough break that will have him out several months, and whoever else has already been sidelined or will be sidelined in the course of Metsian events, you welcome coming up with whatever it takes to fend off Pessimism, Skepticism, Cynicism and Fatalism. It’s probably the last two that had Scherzer getting too close to the boiling crawfish.

Nimmo, it should be noted, sustained his injury in a Spring Training game. There was no celebrating, just kind of a crummy slide. Yet he and Diaz are both out for a spell or more. Quintana had a lesion on his rib. Sorry it was there. Glad they found it. Thrilled it was benign. All kinds of hell will appear at every turn for a baseball player and a baseball team preparing for the season ahead. Sometimes you’re luckier than hell. Pete Alonso had a serious car accident on his way to camp last March. “A close experience with death,” he called it then. He walked away physically unscathed. Sometimes you catch a break despite another driver running a red light. Sometimes you tear a patellar tendon because somebody’s happy you won what you consider a big game. Sometimes you’re just trying to get from first to second. Never mind bubble wrap. Let’s ask Cohen to get us the best possible players and simply put them on display in the Jackie Robinson Rotunda for us to admire, relatively certain nothing terrible will happen to them if they promise to not budge. The second anybody begins to move a muscle is when we brace for the worst.

That strain of anxiety stems from a shall we say checkered past that ran, then limped through last week. This week we go on. Next week the season starts, without Diaz, without Quintana, probably without Nimmo, Brandon’s heart of hearts notwithstanding. All the Mets won’t be ready to go, though there will be a full complement of Mets, a few unexpected when we began shaping expectations about this year, but that will happen (which is why preseason expectations are best formed out of the most malleable clay available). I hope to unconditionally release those Four Horsemen of the Metspocalypse from of our system by Opening Day, or at least reassign them to crawfish cleanup duty at Max’s place.

by Jason Fry on 17 March 2023 1:00 pm Three thoughts on the Mets being unexpectedly and horrifically shorn of Edwin Diaz for the 2023 season:

1) Joe Sheehan got some grief on Twitter for saying that the loss of a “one-inning reliever” was “a bee sting, not an axe blow,” and while I wouldn’t have put it that way — losing Diaz is being stung by the whole goddamn nest at minimum — I do see his point. The Mets arguably have six stars/superstars: Pete Alonso, Francisco Lindor, Jeff McNeil, Max Scherzer, Justin Verlander and Diaz. If I told you that you had to lose one of those six for the entirety of 2023, whom would you choose? You’d hem and haw and look for a loophole of course, what with being a good person and all, but I bet once you were convinced there wasn’t another way out you’d pick Diaz, which is what Sheehan was pointing out. The Mets have added a lot of depth to their bullpen in the offseason and the gap between a good closer and a great one doesn’t strike me as that big when measured over a full season. The Mets will be a lot less fun without the lights going down and the strains of Timmy Trumpet starting up, but I’m not convinced they’ll be an order of magnitude worse.

2) I hate the WBC, OK? I hate it because I can barely tolerate spring training even without shipping off most of the players I know and forcing them to wear uniforms that look like interns designed them, and that was true before anyone important to me got hurt. I think ballplayers who are Mets ought to be Mets all the way (cue the Leonard Bernstein score), and when they’re not actively being Mets they should sit quietly and think about how to be better Mets. But I’m also aware that this is insane. Diaz didn’t blow out an elbow because he was overamped pitching for Puerto Rico in March; he blew out a knee because he’s human and the world is imperfect and shit happened. Gavin Lux just tore his ACL and is out for the season, an injury suffered in the kind of meaningless spring-training game our current situation tempts us to proclaim as invariably harmless. To bring the topic back to closers, in 2012 Mariano Rivera blew out a knee and missed the bulk of a season while shagging flies in the outfield during batting practice. (Believe it or not, bad shit also happens to that local team from that jumped-up beer league.) Ballplayers get hurt, sometimes badly, because they iron shirts while wearing them and stick forks in their eyes and get hungry at night in Miami and have nightmares about spiders and decide early October is an excellent time to trim the hedges. Shit happens, and I’m sorry if that’s not a cogent philosophy, but it’s a lot more accurate guide to life than most anything cogent philosophers have offered us in 3,000-odd years of trying.

3) Imagine for a moment that Diaz had been injured in March 2020, before [all that] happened. Good people would have immediately expressed that it was a terrible shame; people who needed to be reminded that they’re good would have snarked about addition by subtraction before the better angels of their nature tapped them, perhaps a little demonstratively, on the shoulder; and bad people would have said the things that bad people always say. Suffice it to say the reaction would have been different. Instead, the curtailed, artificial 2020 season was the start of Diaz’s rebirth in New York. It was the tentative, fanless start that led to a better 2021 and then the yearlong celebration that was 2022. Back in 2020 we were all ready to drive Diaz to the airport ourselves in exchange for a warm body and a bunch of sunflower seeds; now we’re in sackcloth and ashes over his impending absence. That’s a reminder, when we desperately need one, that being a Mets fan does not actually mean trudging along with a hissing and spitting black rain cloud over one’s head 24-7-. Good things do happen to us, redemption stories are sometimes written, and there really are second acts in Metsian lives. Let’s remember that as we’re mourning this blow.

Let’s remember that, and reflect that we have a lot deeper bullpen than in a year when we won 100 games, and think about how even a bunch of bee stings aren’t fun but usually aren’t fatal.

And if we can hold all that in our heads, why not go a step further?

Fuck it, let’s win it all anyway.

by Greg Prince on 16 March 2023 6:28 pm Prescience wasn’t required to sense it might happen and obliviousness didn’t necessarily obscure your senses if you were reveling in what was going on before it happened. I was between the top and the bottom of the ninth inning of the final game contested within Pool D of the World Baseball Classic, Puerto Rico playing the Dominican Republic Wednesday night. Puerto Rico had Edwin Diaz coming into pitch to preserve a three-run lead for the team representing his homeland. My affinity for Edwin Diaz has nothing to do with the fact that he’s a Puerto Rican and everything to do with the fact that he’s a New York Met. Since 2019, I have hoped Edwin Diaz would nail down saves. Since 2021, I have believed Edwin Diaz would nail down saves. In 2022, confidence morphed into certainty, with his entrance into any given game accompanied by scintillating ceremony underscoring just what a lock he had become. Diaz’s saves weren’t merely competitive necessities. They were events. They were reasons to almost not mind being ahead by three runs rather than four.

It’s outstanding that Diaz is about to pitch an inning even if it isn’t for the Mets, I decided Wednesday night, as long as he doesn’t get hurt. I thought this the way I might instinctively plan my journey on the edge of a crosswalk if no cars are coming in either direction, looking left, looking right, keeping alert to the possibility that a vehicle might appear from almost out of nowhere, and being ready to act accordingly in case it does. I’ve made it safely across every crosswalk I’ve ever encountered by routinely preparing for the worst.

Diaz came into the game for Team Puerto Rico, making me a Team Puerto Rico fan. The PA system at the ballpark in Miami blared his music during commercial break, but the producers of the broadcast airing the game understood they wouldn’t be getting the most out of an Edwin Diaz appearance if they didn’t indulge a version of the hubbub that exalts his entrance at Citi Field. Returned from the commercial, they showed him trotting in to “Narco,” and how excited it gets his fans, in this case those waving flags for Puerto Rico, but also any stray Mets fans who happened to be on hand, or, I suppose, fans of ritual and excellence.

No ritual is better in the contemporary game than Sugar coming in as Timmy Trumpet blows his horn. No reliever is better than Edwin Diaz, home or away. The announcers said as much. They talked about Diaz the way non-Mets announcers not long ago trumpeted Jacob deGrom or non-Nets announcers went on about Kevin Durant or, decades earlier, network voices describing NFL games emphasized no defensive player on the field was better, perhaps in the history of professional football, than Lawrence Taylor of the New York Giants. The Nets of the ABA weren’t on national television all that much, but when they were, such singular praise was heaped on Dr. J, Julius Erving, the way it was on TV and magazine covers and every kind of media extant when Dr. K, Dwight Gooden, and Tom Terrific, Tom Seaver, reigned supreme. When you root for a team and the consensus out there that one of your guys is the best at what he does, it delivers a chill straight up your spine. The good kind.

Seaver died in 2020; I’m still getting over it. Gooden tested positive for cocaine in 1987; I’m still getting over that, too. Erving had to be sold to Philadelphia to allow the Nets to finance their way into the NBA 47 years ago; I’ll let you know when I’m over that. LT’s long since retired. KD’s in Phoenix. DeGrom is a Texas Ranger. Wednesday night, I could still count Diaz in the realm of greatness I could call my own. His impact might not have been the same as those others, his presence in games limited to very specific innings on very specific occasions, but he has shot into their sphere. After 2022, he wasn’t part of the debate of who was best at his position. There was no serious debate. When it came to closers, there was Edwin Diaz and there was everybody else.

I was hyped up on “Narco”. I was hyped up on Team Puerto Rico vanquishing its regional rival, never mind that I had nothing against Team Dominican Republic. PR had Diaz, DR didn’t. I was hyped up on Diaz laying down a 1-2-3 ninth. Just don’t get hurt, and this will be a kick. Not a Mets kick, exactly, and not a game in the standings that mean anything to me, but a pretty good kick for the middle of March. But, needless to day, just don’t get hurt. That kind of kick we can do without.

Edwin and his unhittable slider recorded two quick strikeouts, needing only four pitches to retire Ketel Marte, seven to take care of Jean Segura. The third batter, Teoscar Hernandez, hung in there a little longer. Coaxed three balls out of Diaz, though one implied the home plate umpire could use an eye exam. Fouled off three in a row at one point. I was growing just a touch antsy, less from support of my momentary favorite WBC team and more wondering if everything was all right with Diaz. He doesn’t usually need this many pitches. Is he laboring? Then I reminded myself this was one at-bat in a non-Mets game, he was pitching with a lead, he had two outs and stop worrying, nothing unusual is going on here as long as he doesn’t get hurt.

On the tenth pitch of the at-bat, the twenty-first of the half-inning, Diaz froze Hernandez. Strike three. Out three. Reflexively I clapped the resounding clap of satisfaction. Edwin Diaz just sealed a win. I always clap for that. That it wasn’t for the Mets and that it wasn’t in a game that I’m conditioned to consider one that counts was irrelevant to my surge of adrenaline. It’s like the man himself said in the Super Bowl commercial when he confirmed that order for New York Mets tickets: Yes! The closer!

There won’t be any Sugar answering on the bullpen phone, but somebody will pitch ninth innings. That was fun while it lasted, which is to say until I blinked. I and nobody else had any idea that if you didn’t clap for Edwin Diaz nailing down a save on Wednesday night, you weren’t going to clap for Edwin Diaz nailing down a save for a mighty long time. Because as soon as I unblinked, the announcers were saying something about Diaz being down on the ground amid the Team Puerto Rico celebration and something about him not getting up, and all I could hear after that was myself repeating one word over and over:

“WHAT? WHAT? WHAT?”

Entering Spring Training of 2023, I couldn’t imagine Edwin Diaz not nailing down saves for the New York Mets. My imagination is about to get a workout, and the chill up my spine isn’t pleasant whatsoever.

If you don’t know by now — and if you don’t, I envy you — Edwin Diaz tore his right patellar tendon in the aftermath of Puerto Rico’s victory over the Dominican Republic. Or is that Pyrrhic victory? If what happened to Diaz could have happened to anybody in that situation, the situation could have only happened in baseball in the middle of March if it happens in the WBC, because baseball success doesn’t usually spur celebration this time of year. One supposes an injury from which a player drops to the ground and can’t rise on his own power could happen turning this way or that, or crossing the street, or finishing stretching, or standing up awkwardly in his rented condo. But it happened in the WBC.

The sublime Tom Verducci wrote a column for Sports Illustrated Thursday morning, after Diaz’s injury became apparent but before his prognosis was announced, declaring, “The people who don’t like the World Baseball Classic generally fall into two buckets: general managers, who are paid to worry, and those who don’t truly love baseball” before lecturing his readers that, despite the mishap that we were about to learn had knocked Diaz out of regulation play for the season ahead, the WBC is great and fun and beneficial for baseball. Had Verducci been on assignment in Dallas on November 22, 1963, perhaps he would have filed copy the next day dismissing the concerns of a shocked nation and instructing us we shouldn’t be down on the beauty and majesty inherent in open-air presidential motorcades just because one was rudely interrupted.

The WBC, right until Team Puerto Rico’s celebration commenced, bordered on delightful when consumed in a vacuum. I was watching on and off. I was interested on and off. If Diaz (or Lindor or Escobar) wasn’t playing, I was more off than on, but I kept tabs. It surely wasn’t essential viewing. Not to me, not to Mets fans with no emotional skin in the game. The WBC is here every few Springs. You can curse its existence, but you can’t curse it out of existence. If nobody showed up to play in it or tuned in to watch it or paid their respective currency to wave a flag at it, maybe it would go away. But it’s here.

Diaz isn’t. There won’t be any trumpets blowing come this Opening Day or any day with Mets baseball in 2023. The torn patellar tendon timeline suggests eight months of recovery await. Unless the World Series is rained out a whole bunch, that means “get well, Edwin,” is all the cheering we can do for him. As for the fate of our potential presence deep into the next postseason, the realistic goal of the Mets who signed Diaz as soon as they could once last season ended, the Mets will still play nine-inning games, will still have leads of between one and three runs in some of those games’ ninth innings and will still need a pitcher to pitch those ninth innings. Somebody among the professionals employed by the New York Mets, currently or eventually, will emerge. He may not be “the closer,” but that will be the job at hand. Somebody’s music will play, some iteration of ceremony will materialize, some saves will be put in the books, some save opportunities will go awry. The Mets’ particular superpower of making their fans as sure as fans can be that we’re absolutely gonna hold on to win a close game will not be activated. Outs, however, will happen.

Uncertainty, too, but that’s baseball.

Take your mind off Edwin Diaz’s torn right patellar tendon with a new episode of National League Town. It’s about some good things that have come along in baseball through the years. I don’t believe the WBC is mentioned.

by Greg Prince on 14 March 2023 7:03 pm It’s mid-March. Spring Training is entrenched until it’s not. Games that don’t matter are the norm until they’re not. If a game is accessible on TV, great. If it’s not, well, it’d be cooler if it was, but, really, no biggie. Players of whom you’d barely heard a month ago are your constants until they fall off your radar for a while or perhaps for good. Something called the World Baseball Classic temporarily enchants or irritates you until it disappears from your consciousness for at least a quadrennium. Back in the Grapefruit League, if a game is tied after nine innings, there won’t be a runner automatically placed on second. Everybody will simply go home or go to dinner. It’s enough to make you shrug.

Spring Training hums along, give or take a finger or forearm or something else that suddenly feels off. If nobody gets hurt, nobody will complain too volubly. During the six months that commence in a couple of weeks, baseball is everything. During the month that follows, postseason baseball, if we’re lucky, is everything and more. Then come the months of preparatory activity for the next six-, ideally seven-month period of everythingness, even if those months when we’re waiting for that — November, December and January — we define mostly by baseball’s void. Those are the months when we shuffle through departures and arrivals and hang our tongues out in anticipation of mid-February, which we convince ourselves will certify baseball’s return. Baseball indeed comes back then, but more as a hint than a fact. It’s just more preparatory activity, except sporadically televised and with uniforms. By the time we get to mid-March, where we are currently, it’s been a month of that and the low hum has set in as if it’s here to stay. The low hum is not enough if you want more, and of course you want more. You start to think about such-and-such date in a couple of weeks and realize there’ll be a game that day that matters without qualification, and it better be on TV. Of course you want that.

But the low hum is enough for now, if not much longer. We have hit the spot when we can sense the actual return materializing beyond the horizon. The WBC will be over and forgotten. The transitory figures will resume their journeys peripheral to our view. A few innings for the starters will become most of the innings. The pitchers’ pitch counts will rise, as will the stakes for those still trying to impress. The injuries will be healed or, like Jose Quintana’s, registered on the injured list, a chronicling we’ll have to take seriously because Opening Day and its Opening Day roster will cease to be theoretical. Then again, the Opening Day roster is the roster for just one day.

In 1975, the Mets conducted an entire Spring Training and exhibition schedule in service to carefully inking rather than penciling in every player who would fill every conceivable role in advance of their Opener, at home, on April 8. Yet the club flew from Florida to New York and discovered that one of the injuries they hoped would heal, that pertaining to Cleon Jones’s right knee and affecting his calf, wasn’t all the way recovered. Cleon, a Met since 1963, would be retroactively placed on what was then known as the DL, meaning the Mets would start the season one brick shy of a full 25-player load. They’d thus need an extra Met ASAP, ideally an outfielder who could swing from the right side. It shouldn’t have taken a nationwide talent search to fill the role. They just conducted that entire Spring Training and exhibition schedule. What’s the point of the Grapefruit League if you can’t pluck one of those players who was about to plummet from your radar and place him on your roster?

As if everything is always that simple. After a month of diligent Florida maneuvering, the Mets considered what they’d seen at or proximate to Al Lang Field and turned their attention west to what had recently occurred in the foreign land known the Cactus League, hiring a player who excelled in Arizona; a player who had been playing against them as long as Cleon Jones had been playing for them; a player who just the other year was part of a successful effort to prevent a world championship from becoming theirs.

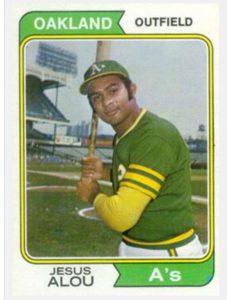

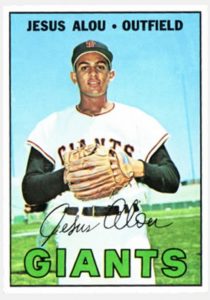

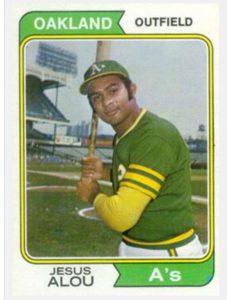

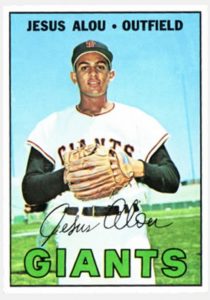

He helped the A’s over the Mets, but Alou would be forgiven. Before the 1975 baseball season was one week old, the Mets welcomed onto their roster Jesus Alou, most recently of the Oakland A’s. We saw him as an A in 1973, during the World Series we almost won, Alou having delivered a couple of key hits in the ALCS to help vault the Kelly Green, Wedding Gown White and Fort Knox Gold (Charlie Finley’s phrasing) into that Fall Classic. We’d seen Alou throughout his career in the National League, dating back to his debut on September 10, 1963, at the Polo Grounds, four days before Cleon himself broke in. Alous were not uncommon sights in the NL, as the Giants had corned the market on all three of them. Felipe had been up with San Francisco since 1958, Matty since 1960. If you became a baseball fan in the seasons that followed Jesus joining his brothers, you were acutely aware that in the sport you chose, there were inevitably three strikes, three outs and three Alous.

Once they were all ensconced within his realm, manager Alvin Dark couldn’t resist introducing them as a trio, pinch-hitting Jesus and Matty directly ahead of Felipe’s spot in the batting order in the eighth inning of their loss to the Mets — “it was like an old vaudeville telephone gag,” observed Harry Jupiter in the San Francisco Examiner — and later inserting each of them as one-third of his outfield for spells in three September blowout wins. This meant sitting Willie Mays, an act Giant skippers habitually resisted if a game’s outcome was in doubt. The last time Alou-Alou-Alou constituted the SF outfield was September 22, with the Mets visiting Candlestick and losing by eleven. Alou ended the game by catching Chico Fernandez’s fly to right.

To be specific, that was Jesus Alou, playing right, while Matty manned left and Felipe patrolled center. For a few weeks, you had to specify your Alous and their positions. In the ensuing offseason, Felipe would be traded to Milwaukee, and two winters later, Matty would be sent to Pittsburgh. Jesus, however, established himself as the Giants’ right fielder in 1964. According to the back of the 1967 Topps card where I made his acquaintance, “the San Francisco brass feels that Jesus has even more potential than his two brothers now in the majors,” though unlike Felipe (three times) and Matty (twice), Jesus never made an All-Star team. He did hit as high as .298 over a full season for the Giants, not bad for a) a converted pitcher and b) “the baby” of the family, which is how I saw him identified in an article when I was a kid and found it kind of curious that a grown man was referred to as a baby. I was also pretty taken by the youngest Alou’s first name. The first Jesus, any pronunciation, I ever knew of was Alou.

Baby Jesus? The Giants may have harbored all three Alous, but they also eventually let go of all three Alous. Jesus was exposed in the 1968 expansion draft and selected by Montreal. Montreal opted to include Jesus in a trade they had no idea would be the most consequential of 1969, the one that shipped Donn Clendenon to Houston for Rusty Staub. The consequence rippled from Clendenon’s refusal to go to Texas, which meant Donn was still hanging around in Quebec in June, perfect timing for the Mets to take off the Expos’ hands the veteran slugger who’d become their World Series MVP four months thereafter — and let us not overlook the foreshadowing inherent in mentioning Rusty Staub. None of that was of consequence to the youngest Alou, who would top .300 twice as an Astro and appeal to Oakland as a veteran pickup in 1973. Those A’s were always adding experience on the fly en route to crafting their surprisingly sturdy dynasty, chronically antsy owner Charlie Finley happy to make short-term deals and not have to pay anybody too much for too long. (Ex-Met Art Shamsky was a briefly a cog on the World Series-bound A’s of 1972.) Alou would play a pivotal role in ’73, stepping in to take over right field late in the season when Reggie Jackson encountered a hamstring injury and allowing Jackson to shift to center when Bill North got hurt shortly before the postseason. His contribution kept him with the A’s as they achieved their threepeat in 1974.

Come the spring of ’75, Jesus possessed two World Series rings but no guarantee he’d continue with the defending world champions despite hitting .586 against Cactus League pitching. Finley’s A’s relished speed in the form of pinch-running specialists. They already famously retained the services of Herb Washington, who literally did nothing but run for Oakland. They were now intent on adding the ultimately less-celebrated Don Hopkins to replicate Washington’s core competency. More speed off the bench meant less space for existing lumber. In other words, goodbye Jesus.

That amounted to a welcome development on the other side of the country, because the Mets had been keeping an eye on Alou. Bob Scheffing, who had been replaced as GM in the offseason, was scouting Arizona and believed in Jesus. Scheffing had a disciple in his successor as general manager, Joe McDonald, and Joe made Jesus an offer. Alou had thought about playing in Japan, where middle brother Matty had alighted with the intent of hitting for average and being compensated well for it, but this Dominican native decided he preferred playing ball in North America.

“We’ve made no promises,” McDonald said upon announcing the acquisition of Alou. “He knows he can be released again. We want him to pinch-hit.” Alou, in turn, was motivated: “I do not want to lose two jobs in a month-and-a-half. All I need is a batting practice or two, and I’m ready.” Jesus, the 32-year-old baby brother in baseball’s most famous troika of siblings since the DiMaggios, had been around, and didn’t require extensive preparation beyond knowing when the bus left for the ballpark. The veteran noted with pride to Daily News reporter Augie Borgi, “I have not missed a bus in seventeen years.”

Despite no Mets fan who diligently tracked Spring Training 1975 making out prospective rosters with the name “Alou” included, the career .279 hitter was suddenly one of ours as of the new season’s second series, in Pittsburgh, and he made his Met debut in the club’s seventh game, at St. Louis. He was a known quantity from a distance, if no more than a contingency ‘x’ factor plopped atop our meticulously considered personnel scheming and dreaming. Maybe we’d get a kick out of finally having an Alou on our side after taking on one or the other let alone all three at once for so long. As fans, we could make no promises, either.

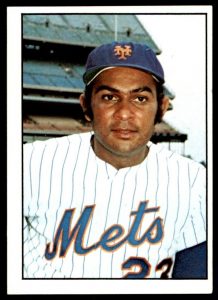

Pretty special as our pinch-hitting specialist. At some point, whatever thoughts McDonald might have maintained about Jesus’s tenuous grip on permanence dissolved. Ours, too. Alou, the first Met World Series opponent determined to make it up to us by joining our side, lasted the entire year and did exactly what the Mets signed him to do. They needed a pinch-hitter? They got someone who established himself as a true specialist. The righty came through time and again, going 14-for-40 for a .350 average as a pinch-hitter. With Ed Kranepool starting more than anticipated, Alou emerged as manager Yogi Berra’s primary pinch-hitter — Roy McMillan’s, too, once the first base coach replaced Berra. Not only did Alou outlast his first Met manager, he endured longer that season than Cleon Jones, who didn’t return from his springtime injury until late May, only to be released ignominiously in July. Alou’s solid ’75 in a niche capacity, not to mention amid a whirlwind of organizational turmoil, earned Jesus a Spring Training spot in 1976. Alas, a visa problem delayed his reporting to St. Petersburg (if only he could have hopped a bus from the DR) and the Grapefruit League success of another, younger pinch-hitting candidate — lefty Bruce Boisclair — resulted in the veteran’s release.

“Jesus is a nice fellow,” said new manager Joe Frazier, echoing what people throughout baseball thought of Alou, “But when [injured] Mike Vail comes back, we need the spot. We have kids with options. You can understand our position.” Alou had been around and got it. He pulled back from playing for a couple of years, but wasn’t done. Jesus returned to action with the Astros in 1978 and 1979. Baseball’s quintessential kid brother played until he was 37 and stayed in the game long after, most notably as Dominican Republic scouting director in this century for the Red Sox, to say nothing of his uncle-ing Mets reliever Mel Rojas (1997-1998), Mets outfielder Moises Alou (2007-2008) and Mets manager Luis Rojas (2020-2021). Jesus Alou, who died last week a little shy of his 81st birthday, lived a long and distinguished baseball life, a year of it as a Met, the entirety of it as one-third of an even more exclusive club.

Unless you were in the outfield for San Francisco on September 15, 17 or 22 of 1963. In that case, everybody you saw was just another Alou.

by Greg Prince on 12 March 2023 11:49 pm As we dim the lights and illuminate our memories, we ask you to direct your attention to the video board for a very special presentation as we unspool our annual montage saluting the Mets who have left us — in the baseball sense — since last Spring.

___

CARLOS JAVIER CORREA

Prospective Third Baseman

Pending Physical

Your team’s owner goes out and secures who he’s secured — let’s continue to pencil in Carlos Correa until notified something’s really wrong with his leg or his negotiations — to go with keeping who he’s kept and you owe it to yourself to look forward to Spring Training. You can’t buy a pennant, but you can certainly shop aggressively for one.

—December 27, 2022

(Reportedly signed with Mets, 12/21/2022; reportedly signed with Twins, 1/10/2023)

___

DEVEN SOMER MARRERO

Infielder

August 15, 2022 – September 10, 2022

A glimpse at the in-progress box score while fast-forwarding past commercials revealed a plot twist I hadn’t seen coming in Atlanta. Not the tally itself, now 13-1, but the participants. There was a catcher making his Met debut, Michael Perez. There was a shortstop making his Met debut, Deven Marrero. And, not altogether unpredictably yet still good for a WHA???, there was a pitcher making his Met debut, Darin Ruf. I missed the three up and three down Ruf recorded in the bottom of the seventh, which means I also missed the first instance of Perez (catching ball one) and Marrero (picking up a grounder en route to the second out) etching themselves into the annals as Mets No. 1,171 and 1,172, respectively. Ruf was already inscribed as Met No. 1,170 from his standard-issue hitting duties, but now he was the fifteenth position player in Mets history to pitch, marking the eighteenth instance in all of a Met position player toeing the rubber. Better Call Saul got paused.

—August 16, 2022

(Free agent, 10/9/2022; currently unsigned)

___

ALEXANDER “Alex” CLAUDIO

Relief Pitcher

September 7, 2022 – September 14, 2022

By the time he handed matters over to a cobweb-gathering Adam Ottavino and the fresh, violent left arm of Alex Claudio, the old wives’ tale of the Mets never scoring for Jake had gone upstairs to bed, at least for another five or six days. The Mets notched 17 hits, six of them doubles, none of them homers.

—September 8, 2022

(Free agent, 10/9/2022; signed with Brewers, 1/3/2023)

___

THOMAS MATHEW SZAPUCKI

Pitcher

June 30, 2021 – May 25, 2022

You couldn’t do much worse for Met pitching in any year than what the Mets got Wednesday from Peterson, Reid-Foley and, sad to say, Szapucki. Thomas neither pitched particularly well nor fielded his position with aplomb. The first Brave to score on the rookie’s watch came home when a potential rundown imploded because Szapucki didn’t think to pursue the dead-to-rights Dansby Swanson between third and home. That runner was inherited from Reid-Foley. The rest that scored between the time Szapucki escaped the fourth down, 11-2, and before succeeding pitcher Albert Almora, Jr. (you read that right) surrendered a three-run bomb to Ozzie Albies, which was posted to Thomas’s ledger. Luis Rojas had hoped to ride his spanking new southpaw clear to the end of the horror show. As a minor league starter, Szapucki was positioned to give the Mets length. But in the ninth, it was fair to infer he was feeling kinda seasick as the crowd called out for more.

—July 1, 2021

(Traded to Giants, 8/2/2022)

___

JOHNESHWY ALI FARGAS

Outfielder

May 17, 2021 – May 24, 2021

Did ya see how the bottom of the ninth between the Mets and Marlins began on Saturday? Jesus Aguilar lined a ball into the gap between center and right. It would take two kinds of Tommie Agee efforts to reel it in: the kind where Agee dove to rob Paul Blair and the kind where Agee hung on in his webbing to rob Elrod Hendricks. Those were two of the most stupendous catches in World Series history. Amid stakes admittedly a few hundred notches lower, Johneshwy Fargas incorporated the most breathtaking aspects of each to nab from Aguilar a leadoff double and, as Smith did minutes earlier, keep the score knotted at one. Running and diving and gaining proximity to the ball would have been impressive as hell. The ball ticking off the top of Johneshwy’s glove would have been reluctantly understandable. But, nope, Fargas was gonna have his scoop and lick it, too. As so-called ice cream cone catches go, this one melted in your mouth and made your eyes water with joy.

—May 22, 2021

(Released by Mets, 8/14/2022; currently unsigned)

___

YOLMER CARLOS SANCHEZ

Infielder

August 20, 2022 – August 25, 2022

It gets instinctively edgy in South Philadelphia when the ninth inning rolls around. The most elite of relievers wasn’t about to simply shoo away the dephlated Phillies. You could take all the precautions — gloveman Sanchez was in for Baty as the 183rd third baseman in Mets history — but you couldn’t avoid trouble. You just had to contain it.

—August 22, 2022

(Free agent, 10/11/2022; signed with Braves, 1/24/2023)

___

ROY EMILIO “R.J.” ALVAREZ

Relief Pitcher

August 16, 2022

Not R.A. Dickey and not Francisco Alvarez and not Robert Gsellman, though he kind of looked like him.

—January 29, 2023

(Free agent, 10/9/2022; currently unsigned)

___

ENDER DAVID INCIARTE

Outfielder

June 28, 2022 – July 13, 2022

As if Met defense could use the help — we’ll never turn down assistance — the club signed Ender Inciarte to a minor league contract. Inciarte now has a chance to become the Willie Harris of his day. Willie Harris, you’ll recall, took extra-base hits of all variety away from Met batters in the 2000s. Then he became a Met in 2011, not having the same impact for the Mets that he had against the Mets, but he was a pleasant enough veteran presence for a non-contending team. Inciarte used to rob us blind in the 2010s. Here’s Ender’s chance to make it up to us.

—June 20, 2022

(Free agent, 7/18/2022; currently unsigned)

___

YENNSY MANUEL DIAZ

Relief Pitcher

May 23, 2021 – September 13, 2021

Lugo sat for good after his one inning. Luis Rojas via Dave Jauss went to Yennsy Diaz to start the tenth of a 1-1 must-win game versus the Los Angeles Dodgers, with a runner automatically on second because that’s how Rob Manfred likes it. This Diaz hasn’t pitched enough in tight situations to make us nervous. This Diaz not having pitched all that much in tight situations is what made us nervous. No offense, Yennsy, but we know Seth Lugo. He’s not infallible, but we carry forth images of Six-Out Seth Lugo having gotten us through second innings with aplomb. We only knew in the tenth that Diaz wasn’t Lugo, and that it wouldn’t take much to score the Manfred on second. It didn’t.

—August 15, 2021

(Released, 08/08/2022; signed with Sultanes de Monterrey (Mexican League), 2/20/2023)

___

SAMUEL THOMAS HUNTER “Sam” CLAY

Relief Pitcher

August 20, 2022

Saturday brought three Met debuts […] with Clay joining R.J. Alvarez as a recent escapee from Met ghost status.

—August 21, 2022

(Free agent, 11/10/2022; signed with Diamondbacks, 12/12/2022)

___

MATTHEW WILLIAM “Matt” REYNOLDS

Infielder

May 27, 2016 – October 1, 2017

April 16, 2022