The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 15 August 2022 9:35 am This is the stretch that will send the Mets down one of two postseason roads: a newfangled bye that advances them to the division series, or a dogfight in the scrum of the wild-card round. Three with the Phillies, four with the Braves, four more with the Phillies, two with the Yankees.

Well, so far so good.

Our good friends from Philadelphia came into Citi Field, scored a conventional run off Max Scherzer immediately on Friday night, sent a ghost runner home against the luckless Mychal Givens later that evening, and … oh wait, that was it.

Nothing against Jacob deGrom and three relievers on Saturday. And nothing against Chris Bassitt and four relievers on Sunday.

Bassitt doesn’t have the raw stuff of Scherzer and deGrom, which is no insult whatsoever, but he’s cut from a similar mental cloth: intense, furiously competitive, ornery. There are the long shake-off sessions with catchers, the chess games he likes to play with hitters, and the “grind you till you break” philosophy articulated in spring training and now immortalized in his heavy-rotation Mets profile ad. (Hapless customer: “Uh, sir, I just came to this weird deli to get a pack of smokes — please no grinding or breaking. Also, why is this place infested with ballplayers?”)

I’ve come to admire Bassitt’s gunfighter stare and that violent pitching motion — the knee coming high as the arm cocks low behind him, then whips overhead at a slightly odd angle. Not to mention the array of pitches that might emerge from that delivery: three varieties of fastball, with the sinker most prominent; a slider; and a curve.

Bassitt had all of those pitches working Sunday, and needed them for heavy lifting in the fourth and fifth innings, facing two on and no out in each frame. No matter: In the fourth he fanned J.T. Realmuto on three pitches, got Nick Castellanos to fly out, and elicited a comebacker from Darick Hall; in the fifth, facing second and third, he fanned Matt Vierling and Bryson Stott, walked Rhys Hoskins after a lengthy duel, and erased Alec Bohm on a liner to second.

Runs had been hard to come by for the Mets, too, but on Sunday they finally woke up and swung the lumber against old friend Zack Wheeler, with a four-run fourth putting the game effectively out of reach. That inning’s scoring ended with a bonus run, as Jeff McNeil scrambled home to punish a bit of lackadaisical defense from Brandon Marsh and Jean Segura.

(I’d say Keith Hernandez must have uttered a belated “told you so,” but between Keith’s being elsewhere this weekend and his living in a highly Keith-centric world at all times, I’d put decent money on him having no idea that he gave the Phils bulletin-board material or that they responded by playing essentially airtight defense until then.)

The lone blemish of the Mets’ series win, if you don’t count the Marlins’ pacifism in getting steamrolled by the Braves, was the sight of Luis Guillorme limping home in the Mets’ uprising against Wheeler.

It’s been a joy to watch Guillorme have the breakout season I’d stubbornly insisted he had in him, sometimes without much evidence. That was a long time ago. Now, with two outs, I’ll urge enemy batters who can’t hear me to “hit it to anybody,” but with games on the line my plea is more specific: for some opponent to hit it to Guillorme, because I know he’ll do exactly the right thing. And none of that admiration has touched on his emergence as a useful if not terribly powerful bat; his glorious beard worthy of a Babylonian bas-relief; or his vaguely ironic mien in going about his business.

Guillorme has also been a key to the Mets’ positional flexibility, able to move seamlessly between second, short and third in various infield alignments. Hopefully the Mets will be without him only for a few days as this critical stretch continues. And, hopefully, said critical stretch will continue to be a showcase for smothering starting pitching, hitting in whatever quantity necessary and that most vital currency of all, series wins.

by Greg Prince on 14 August 2022 11:01 am The sound of one hand clapping makes about as much noise as a batter facing Jacob deGrom. Yet at Citi Field when Jacob deGrom pitches, all the hands clap and the noise overwhelms. Not as much as Jake overwhelms. Little can outdo deGrom in that regard.

We bring the sound. Jake brings the fury. The Phillies, like every opponent, bring the best of intentions. Good luck, fellas, I’d tell them, albeit without sincerity. I wish you long, happy, healthy lives, yet in the spirit of full disclosure, nothing but ill will at the plate, in the field or on the mound. On the mound, you’ve been pretty good yourselves for two nights. In the field, you’ve appeared determined to make a certain color analyst recant all the sighs and groans and “throw a tent over that circus” he’s directed at your (until recently) ludicrous leatherwork. But at the plate, you’re still facing Jacob deGrom, and he intends to give you nothing. I doubt the Phillies wanted to see deGrom any more than Keith Hernandez wanted to see the Phillies.

Saturday night at Son of Shea — not only was Citi ramped up to a vintage volume, but my literal vantage point brought to the mind’s eye a way of seeing a game that hasn’t existed since Citi Field was under construction — everybody pitched as well as could be asked from a baseline perspective. Let’s put it this way: Edwin Diaz was, by default, the least impressive of the five arms throwing baseballs for either side, and he gave up neither a run nor a hit en route to notching another enormous save.

Diaz is saved for last. DeGrom throws the first pitch of any home game he works. He appears, we go wild. Not that we needed much of a cue, but once those of us who weren’t in the park last Sunday took in the ace’s warmup on TV, we recognized how special it is just to watch Jake throw the pitches that don’t count. Now we understand those as our portal to deGrominant immersion. Once he gets going for real, against professional victims, our impulse is to segue from Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Simple Man” to the Dovells’ “You Can’t Sit Down,” except you probably have to sit down, lest the people behind you shame you in a shower of DOWN IN FRONTs.

I mentioned my vantage point. As noted earlier Saturday, Stephanie and I had the honor and pleasure of joining our friends the Spectors at their 27th (25 + 2) anniversary party, thrown at the hottest joint in town, Citi Field. Specifically, we were in the Seaver Suite on the Empire Level. It’s down the right field line, befitting one of the greatest righthanders in baseball history. And what better spiritual post than the Seaver Suite from which to watch the greatest righthander in contemporary baseball?

If you could see the mound Saturday, you saw everything. The only issue with the suite life from a viewing standpoint, at least on this occasion in short right field, was if you didn’t elbow out other swell people from the allotted outdoor seating (which we didn’t), you needed to plant yourself at a proper angle to take in as much as you could, cognizant that you had to prioritize. Citi Field geometry almost always subtracts something from your line of sight wherever you sit or stand. Here, the shortfalls in geometry were leavened by magically refilling trays of sliders, franks and fries, free-flowing beverages and the delight of mingling among an array of fine folks in air-conditioned comfort (even Garry and Susan’s Phillies fan friends seemed swell), which is to say who’s complaining if you can’t see the scoreboards or certain swaths of grass? If anything, the experience took me back to those stolen glances from the old subway platform extension, the one demolished prior to the final year of the old ballpark to clear space for the coming new ballpark. You might retroactively refer to it as the original Shea bridge, leading down a spiral staircase to the token booth rotunda. You couldn’t see everything from up there, but you could see enough.

My spot in the suite got me in line with Jacob’s delivery. If you could watch deGrom form his motion and fire, you saw everything you needed to see. That and the plate, where Phillie after Phillie was phlummoxed. That was the fun and game there. My Log tells me this was the 24th time I’ve seen Jake pitch at Citi Field. I don’t know that I was ever quite so focused on him (between burger bites) or nearly as blown away. He must look like hell from the batter’s box.

My seat was a tall bar stool that I staked out a little corner for. It allowed me to rest between pitches, because during pitches, I was up on my feet. There was just enough space for me to pace anxiously without making too much of an obstacle of myself. “Can’t Sit Down” didn’t apply to the Phillies. For six innings — the moderate workload wasn’t surprising despite the sudden appearance of Seth Lugo in the top of the seventh jarring me off of my chair — Philadelphia batters returned to their seats with alacrity.

We roared, Jake released, and nothing happened except exquisite pitching brilliance. Rhys Hoskins singled in the first only to be erased on a forceout. Bryson Stott lined a single to center only to be stranded when Hoskins struck out to end the sixth. And that was the entirety of the Phililes’ offense. No extra-base hits. No walks. Nothing threatening. Ten strikeouts in all.

The third strikes were so much fun to watch. Wow, they really are helpless against him, just like on TV. The occasional fly ball I didn’t really feel the need to follow (which would have necessitated neck-craning and such). I could tell what he was throwing wasn’t traveling too far or in much danger of falling in. I was in sync with Jake. My pacing didn’t drive him off kilter. My frequent applause was just a fraction of the supportive din.

You almost didn’t notice Aaron Nola crafting a gem of his own. At first, you didn’t have to, because the Mets cobbled a run together in their first ups. Starling Marte, as if to make up for Friday night’s ill-advised dash for home, built three-quarters of a run himself by singling, stealing and taking third on a throw into center. Pete Alonso brought him in ASAP.

That was the extent of what Nola gave up. It was too much of a hole to dig against deGrom, but whereas Jake departed after six (it was still only his third start of the year after thirteen months of major league inactivity, you had to keep telling yourself), Nola hung in there. No reason to lift him and no pitcher is pinch-hit for anymore. The Mets’ output after the first was as meager as the Phillies’ through the sixth, leading to the only foreseen drama of the evening. Would we be able to span the gap from deGrom to Diaz?

Seth materialized in the seventh and simply by not being Jake, he was the best chance of the visitors’ night. There was indeed a base hit, via Nick Castellanos’s single, but it came with the bases empty and two out and it was followed immediately by a strikeout. Trevor May succeeded Lugo, resembling the May we heard so much about in his pre-Met incarnation (a little like Diaz the Mariner needing time to find a holistic comfort level in New York, perhaps). Trevor notched two Ks, then didn’t falter when Kyle Schwarber lifted a ball to center. It was caught by Brandon Nimmo, leaving the score Mets 1 Phillies 0. That’s also where Nola left it when he completed his eighth inning of almost spotless work. It occurred to me that if all went well, I’d just seen a complete game thrown by a pitcher on the losing side.

We just needed all to go well. We’ve reached a stage in our lives as fans that we expect all to go well when it’s Diaz time. It’s a 180 from where we sat in 2019 and probably a 135 from where our hearts stubbornly positioned themselves before the reality of 2022 fully kicked in. Edwin’s stats improved so much in 2021 and glittered in the right light in 2020, yet you never really stop mistrusting your closer unless your closer convinces you to do otherwise. Edwin Diaz has become the most convincing Met closer I’ve ever known. The only thing that could mess with the tableau unfolding ahead of the ninth — there’s no DOWN IN FRONT-ing for the raucous “Narco” entrance, because everybody’s up and everybody’s loud — was the looming inevitability of an eventual lesser outing from the master of the three-batter save, that vague but palpable sense of it has to happen sometime. As much as Citi Field throbbed for Jake, it pulsated for Sugar. Their noise’s common denominator was confidence. We turn up the volume because they’ve supplied the certainty, excitement born of trust. Still, you couldn’t completely bar from your head that one nagging question, especially with the thinnest of 1-0 leads, even after Lugo and May had quelled the initial wave of post-Jake doubt.

Would Saturday night be the night the trumpets hit a sour note?

I inserted myself into the suite’s official seating section to get the most expansive view available. Edwin Diaz was not immaculate. He did not flirt with perfection. He didn’t even strike out the first guy he faced, relying instead on Luis Guillorme to field a ground ball and fire it to Alonso for the first out. Then he walked Hoskins, whose pinch runner Edmundo Sosa stole second pretty easily. Alec Bohm flied out to right, which could have been a tag-up problem had Marte not made a strong throw into the infield. Then J.T. Realmuto walked on three-and-two, bringing up Castellanos. It would take seven pitches — during which there’d be a double steal that amounted to defensive indifference in a 1-0 nailbiter because Edwin would not be distracted by baserunning hijinks — but we never for a moment vocalized an iota of regret that we’re all in on Edwin. The closer was trusted to close a one-run lead with runners on second and third amid nary a boo. Our anxiety in the moment was empathetic rather than accusatory. That particular vibe in the ninth inning at a home Mets game has been rare since the Shea subway extension stood. It was by no means common then, either.

The end result was what we sought, and it was multifaceted:

Diaz struck out Castellanos.

Diaz saved the win for deGrom.

Diaz maintained our affection.

The Mets cooled the surging Phillies’ aspirations for one night.

The Let’s Go Metsing was as strong as ever on the short staircase trip from Empire Level to Field Level.

And on the LIRR home, east of Jamaica, no less, we heard “Narco” cranked up on somebody’s phone…and it wasn’t even mine.

The game was long over, but the melody lingered on. Timmy Trumpet blows. Edwin Diaz doesn’t.

Across nineteen innings, these two teams have pitched each other to a 2-2 tie. It doesn’t shake out that way in the standings, but maybe aesthetically should. One night, Ranger Suarez & Co. barely outpointed a Max Scherzer-led mound initiative that was effective enough to have prevailed most nights; and the next night Aaron Nola stayed within a shoelace tip of the deGrom-to-Diaz super express, one that made stops at Lugo and May without encountering delays. Tight games both. From our perspective, the second was the keeper. It looked great from where I stood. It sounded even better.

by Greg Prince on 13 August 2022 4:38 pm On July 22, 1995, the no-name, no-hope New York Mets were hot, having emerged from the All-Star break winning seven of nine. On the soundstage where they shot Star Trek: Voyager, Jeri Ryan presumably looked up, thinking her character was written into a new scene as SportsCenter blared in the background.

Seven of nine! The Mets had spent the first half of that strike-delayed season stashed in last place, as if on the lam, figuring no one would find them if they lodged themselves far enough down the cellar. But now, having shaken off those April-to-June doldrums, they were, reliable sources could have sworn, ready to start climbing in earnest. Instead, on July 22, a Saturday, they lost. Then they lost again on Sunday. They’d go on to lose every day clear through Wednesday.

Happy Swanniversary! Was this any way to start a marriage? Maybe not the marriage of the Mets and post-1993 respectability, but it worked for Susan Laney and Garry Spector, who were engaging in marriage to each other somewhere in Oklahoma, Susan’s home state as well as that of 1995 Mets Kelly Stinnett and Butch Huskey, along with Mets voice for all seasons Bob Murphy. I didn’t know either Garry or Susan then, but I’m gonna go out on a limb and imagine some time before the first pitch of that Saturday ceremony, Garry checked the box score of the Mets-Rockies game in Colorado from the night before.

I’ll also take the liberty of deciding their honeymoon was perfectly lovely despite the five-game losing streak that probably crossed Garry’s field of vision at some point in the first throes of wedded bliss. I made sure to get married in November so I wouldn’t have to sweat such details. But this isn’t about me. It’s about Garry and Susan getting married when they did and life continuing on for them back in the Northeast, she a world-class oboist (or have you not heard of the Metropolitan Opera?), he a top-flight chemist, if I have his science credentials correct. I’ve rarely seen better chemistry between two people than that which exists between Susan and Garry, so I’m gonna assume I do.

As implied above, Garry’s been a Mets fan for a long time, long before winning seven of nine ranked as an unparalleled achievement for the mid-1995 Mets. Garry’s been a Mets fan long enough to inspect a roster of early-1970s Mets and decide somewhere on there was a defending world champion who’d love to come to his Bar Mitzvah. The act of addressing invitations transcends whether any of them showed. I’m not sure how long Susan has loved the Mets. Perhaps it had something to do at first with loving Garry. She’s her own fan, however. Read her blog Perfect Pitch for confirmation.

They lived as Mets fans, they raised a Mets fan daughter and they invested in the Mets, holding prime season tickets since before Shea went away and after Citi Field opened. You might know them as “the Spectors” of Section 318 — directly in front of the radio booth — if you listen to the games over WCBS with any frequency. Howie knows Susan and Garry are there practically every night. When a foul ball is heading directly back into the crowd, Howie from time to time estimates, “That might reach our friends the Spectors in Section 318.” When your team’s play-by-play announcer has conferred ground rule status upon your presence, you indeed get to a lot of games.

I don’t know who’ll be sitting in those seats tonight for the Mets and Phillies. None among Susan, Garry or daughter Melanie (a Resident Artist with Detroit Opera herself) will be. They’ll be a level below, having taken a suite for the evening. It’s a big suite. It’s a big night. DeGrom is pitching against Nola, but it’s bigger even than that. The Spectors are celebrating an amalgam of their 25th, 26th and 27th anniversaries tonight at Citi Field. If the Mets are at home, where else would the Spectors be?

Your math skills don’t elude you. No. 25 — the Del Unser anniversary, to my thinking — was two years plus a few weeks ago. They planned their Unser down to the D-E-L, or the letter. The only thing the Spectors couldn’t plan on was what 2020 had in store for all of us. No, nobody was going to a ballpark in 2020. Nobody was going much of anywhere. Thus, Del Unser would be double-switched out of the anniversary game for…

That’s right, Dave Kingman, No. 26. They were gonna do in 2021 what they intended do in 2020. But you know how Sky King could be about striking out. The COVID situation was still capable of diving for fly balls and doing something unspeakable to its thumb. Alas, the Kingman anniversary had to take a seat next to the Unser.

It’s a new year, a better year where the Mets are concerned, which is nice. It has a new anniversary going for it: No. 27, Craig Swan. Perfect. Swannie led the league in ERA once. So has Jake. Officially, the Spectors have dubbed the evening “Twenty-Five Plus Two,” which encompasses Swan and Kingman and Unser as I see it. They’ve been kind enough to invite Stephanie and me to join them and their friends and family at Citi Field tonight. We carry the credentials of neither Art Shamsky nor Ron Swoboda nor anybody Garry sought for his Bar Mitzvah, but we are honored to attend.

The best thing I can think to give them is the game of April 28, 1976. It’s not really mine to give them, but it’s not like it’s doing anything else right now but gathering dust in the archives. On that Wednesday afternoon at Shea Stadium, Craig Swan — 27 in your scorecard, folks — took the start against the Atlanta Braves. The game began at 4:05. That was intentional. It’s also probably irrelevant, but the Mets experimenting with 4:05 weekday afternoon starts early in the 1976 seasons sticks with me (M. Donald Grant, what an innovator). Attendance spiked all the way to 7,602 from the day before, which also started at 4:05 PM. On Tuesday April 27, the Mets and Braves drew 4,002. Bruce Boisclair ended that game with a double that drove in Jerry Grote and John Milner with the tying and winning runs. Perhaps the residual Boisclair-generated excitement is what nearly doubled the gate. Maybe young Garry Spector dropped everything he was doing up in Albany, hopped a bus and joined in the fun (probably too long a commute for young Susan Laney out in Oklahoma).

So Swan started and threw a shutout inning. One zero on the board. Versus three-time All-Star Andy Messersmith, a celebrated acquisition for Ted Turner’s Braves (he was the first active pitcher specifically freed from the reserve clause, a remnant of baseball’s moldy past about to be completely consigned to the ash heap of history, and granted the agency to seek employment where he chose — in other words, the majors’ first true free agent), Boisclair led off the first by looking at strike three. I guess Bruce tired of heroics quickly. Felix Millan came up next, choked up on his bat and flied to the shortstop. Two outs, nobody on…but wait! Who’s that coming up to bat?

Why, it’s No. 25, Del Unser. No. 25 is what Susan and Garry set out to celebrate two years ago until COVID walked away with the party. Del retroactively makes it up to us here by walking against Messersmith. Unser’s on first. Batting cleanup for these 1976 Mets? It’s Ed Kranepool. He wears No. 7 and he’s perennial. You can put him in most any Met story between September 1962 and September 1979, and Eddie fits. Eddie singles. Del zips to third.

Which means the five-hole hitter will have a turn at bat in the bottom of the first, and batting fifth, at manager Joe Frazier’s behest, is the holder of the New York Mets’ single-season home run record, established one year earlier and already appearing in danger of extinction in the year ahead. It’s No. 26, Dave Kingman. Kingman has hit eight home runs in the Mets’ first seventeen games. He’s hit them out of Shea, out of Three Rivers, especially out of Wrigley, onto Waveland Avenue, a.k.a. the Cubs’ backyard. One of Kingman’s dingers was reported to have cleared “everything on Waveland Avenue but a treetop”. Another was said to have “hit the porch roof of the third house up the block on Kenmore Street”. Viewers in New York learned so much about Chicago geography from Dave Kingman batting.

Nothing much lurked directly beyond Shea Stadium’s left field fence except the parking lot. After a bunt attempt went for naught — Kingman was a slugger more infatuated with the element of surprise than he was his own raw power — Dave turned his focus to the general direction of the fans’ cars. BAM! (sound effect added), the score was 3-0, Mets. “It wasn’t a home run cut,” the reticent Kingman appraised. Some hitters don’t need to swing as hard as they can. Sky King left the Chryslers and Plymouths undented, reaching only the Braves bullpen, but it was a long enough shot. He now had nine homers in eighteen games, which could be extrapolated to 81 in 162 games. If you don’t think there was a kid on Long Island calculating the record-shattering pace Kingman was on, then you didn’t know me then and don’t me now.

But again, this isn’t about me. This is a celebration of No. 25, who scored the Mets’ first run, and No. 26, who drove in the Mets’ first and only three runs of April 28, and, mostly, No. 27. Craig Swan took his three-run lead and guarded it with his life. Swannie went nine innings, the distance. He struck out eleven Braves, allowing only five singles and one walk. No runs. It became the first complete game of Swannie’s career and, of course, his first shutout. Messersmith, whose free agent availability attracted interest in the offseason from owners who wished there was no such thing as free agency, tipped his cap to his mound opponent:

“I was running into Walter Johnson That kid pitched a hell of a game.”

Even if Swannie never quite lived up to that kind of hype (Walter Johnson won 417 games, Craig won 59), No. 27 seized the day, with a big boost from No. 26 and a little help at the outset from No. 25. I really don’t need much of an excuse to invoke the likes of Craig Swan, Dave Kingman and Del Unser. Nice of Garry and Susan Spector to provide one. Everything about them is nice, actually. They truly deserve the best tonight. It’s appropriate they’re getting Jacob deGrom.

by Jason Fry on 13 August 2022 12:49 am Let’s get this part out of the way: I was in the front of the Promenade a fair distance down the first-base line. So I can’t tell you jack about Max Scherzer‘s stuff or location or exactly what happened to various Met defenders or anything else that relies on the nuance of an up-close view. Being in the park isn’t about any of those things unless you’re in the really fancy seats; rather, it’s about what you can’t recreate in your living room, namely becoming a small part of a shared experience.

And hey, that part was fun, even as everything else proved frustrating. The high-water mark, of course and alas, came when Francisco Lindor drove a Seranthony Dominguez sinker to deep center with no one out in the ninth and Starling Marte on second. The ball was going to be gone for a walkoff homer, or off the wall for a walkoff single, or at least it was going to be a long fly that would move Marte to third and allow the Mets to win the game on a walkoff a batter later, and Citi Field was one gigantic jet-engine roar which you knew was only prelude to the bigger roar to come.

Well, except it never did.

Lindor’s drive was a long fly. Marte did indeed move to third. And so the ninth inning came down to Dominguez against Daniel Vogelbach, who hit the requisite fly ball to left, where someone named Matt Vierling was waiting. It wasn’t as deep as you’d like, but it would take a perfect throw to get Marte, whom Joey Cora properly sent homeward. Vierling’s throw came in hard and slightly up the first-base line, where J.T. Realmuto snapped it out of the air before flinging himself at Marte, catching him across the chest a moment before his hand slapped the plate. The Mets wouldn’t win in a walkoff, Vogelbach’s rocket ride as Citi Field cult hero wouldn’t reach new heights, and the Mets and Phillies would play on into extra innings.

Honestly, it was kind of a miracle that things got that far. Scherzer looked out of sorts in the early going, battling himself and a run of buzzard’s luck that saw plays not quite made, ducksnorts and parachutes drop onto the outfield grass, and two Met infielders exit — Eduardo Escobar with what’s billed as a side injury and Jeff McNeil with a lacerated finger suffered in an odd collision with Rhys Hoskins. But then other Mets looked out of sorts too — besides the defense being ever so slightly miscalibrated, the hitters did next to nothing against Ranger Suarez, who hung around far later than most enemy starters these days. The Phillies, meanwhile, were playing crisp defense, perhaps mindful of all the bulletin-board material Keith Hernandez recently gave them.

One team played crisp and clean and the other one looked a bit ragged, but that still meant a 1-1 tie going to the 10th.

And then, ah, the bedrock unfairness of baseball. Mychal Givens made a nifty play on a little tapper, then got a flyout and a strikeout — a blameless performance for which he was rewarded with a loss. That flyout unfolded almost as a mirror image of the play on Marte: Alec Bohm hit a fly to Marte, a bit deeper than Vogelbach’s, which Marte fired in to Tomas Nido on one hop, in plenty of time to get Bryson Stott at the plate — except that hop was a short hop, and the ball ticked off the tip of Nido’s mitt and bounded away. Could Nido have fielded it? Yes. Was it a tricky hop requiring a do-or-die snag? Also yes. Did the Mets make those kind of plays on Friday night? Not often enough.

The ball bounded away, allowing Stott to score and the Phillies to turn the ball over to David Robertson, so recently coveted as one of our bullpen additions. (That was perhaps a little extra cruel.) Robertson got Tyler Naquin looking at a cutter on the edge of the strike zone, elicting a big collective oof! from the crowd, and then coaxed a grounder from Luis Guillorme, and so the Phillies had won — a win they thoroughly earned, but one that will leave a mark anyway.

by Greg Prince on 10 August 2022 11:45 pm Some days this year as a Mets fan, if you’re lucky (which you are if you’re a Mets fan this year), you feel a little like Tommy Flanagan — pronounced fluh-NAIG-un — Jon Lovitz’s truth-stretching character whose Saturday Night Live catchphrase “that’s the ticket” had the country in stitches for about a year in the mid-’80s. As with many of the decades-old popular culture references I’m compelled to invoke in this space, maybe you had to be there.

Flanagan was referred to as The Pathological Liar in deference to everything coming out of his mouth stretching credulity. That sort of behavior used to be considered universally antithetical to trustworthiness, thus it was considered hilarious rather than admirable that somebody would do nothing but lie to a mass audience. Another case, perhaps, of having had to have been there. Here and now, it could be that the hardest part of being a Mets fan is when you offer a factual account of their daily exploits, it’s almost impossible to have it sound believable.

Honestly, it’s the only hard part of being a Mets fan here and now.

“Yeah, I went to the Mets game today. They scored six, no eight, no TEN runs! Francisco Lindor — he’s our shortstop — scored one, no two, no THREE runs himself. He’s scored at least one run in five, no nine, no THIRTEEN games in a row. That’s a team record! Almost everybody, no EVERYBODY in the starting lineup was on base. Two, no four, no SIX of them scored runs. One of them leads the ENTIRE LEAGUE in runs batted in. The Mets won their third, no fourth, no SIXTH game in a row and have nearly as good a record as they did at this point in 2006, no 1988, no 1986! And this weekend we’re gonna have Max Scherzer starting for us on Friday night and Jacob deGrom on Saturday night because Max Scherzer is on our team and Jacob deGrom is healthy. And if we’re ahead by only a little in the ninth inning, we’re not gonna be the least bit nervous. No, we’re gonna clap along while somebody plays trumpets. Oh, and at today’s game, I sat in plush seats practically behind home plate next to a real Broadway singing star. Yeah, that’s the ticket!”

Good bit. Except everything in the above paragraph is the emmis truth. It only sounds like a wild exaggeration if you’re not in the middle of it. It is our good fortune to be in the middle of all of it. The six in a row is our current roll, the last three of which came at the expense of the Reds, following three taken from the Braves, encompassing a 15-of-17 megaspurt that has taken down opponents of all competitive stripe. The Reds would be charitably described as middling. They weren’t too bad before playing us. A few innings versus the Mets seemed to have them checking to see if the jet whisking them to Iowa for the Field of Dreams game was fully fueled and ready to fly. They were in the midst of an afternoon nightmare Wednesday.

Lindor indeed continued to do Lindor things, which is the most convenient way to describe the tear he’s been on for more than a month. A couple hits, a couple ribbies, a walk, another three runs when just one was needed to tie David Wright’s consecutive games scoring mark. Francisco was hardly alone. National League RBI leader Pete Alonso — four shy of a hundred already — went three-for-five. Tyler Naquin, who’s probably happy to no longer be a Red and even happier to be a Met, homered and scored twice himself. Daniel Vogelbach brought his milkshake to the yard. And so on and so forth and what have you. Truly it was hard to keep up with the deluge of offense. Just ask Cincy, once you scrape them up from their 10-2 flattening.

The Mets’ pitching side, while not as spectacular (how could it be?) was sound, which itself was spectacular after last Friday when Taijuan Walker kinda blew up in the sole loss to date on this homestand. Plus there was something mumbled about a sore hip. Tai appeared ship shape and Bristol fashion over six innings, allowing only two runs to the Reds, and our modest anxiety to dissipate. Walker is a highly dependable No. 3 starter on this staff. So is Chris Bassitt. So is Carlos Carrasco. The Mets have five starters, all of whom I’d be OK with as Game One starters in a playoff series, all of whom I’d be comfortable with should they find themselves with the ball to start a decisive Game Five or Game Seven.

Yeah, I know we have deGrom and Scherzer. Yeah, I know we have two months to go. But I also know that at 73-39, the 2022 Mets are inhabiting rare air. How rare? Wrap your mind around this: should the Mets win three of their next five games, albeit against Philadelphia and Atlanta (who, conversely, have to play us), they will be 76-41 after 117 games.

The only Mets team that’s ever been 76-41 after 117 games is the 1986 edition, and they had to go into a slump to dip to 76-41. No Mets team that isn’t the 1986 Mets ever shows up in the “best record after ‘x’ games” conversation once the season passes the one-third mark. Yet the 2022 Mets are on the cusp of matching the 1986 Mets, even if it’s for one fleeting juncture.

Dude, that’s Amazin’.

Liz Callaway, surrounded by admirers. Also Amazin’: that kicker slipped in earlier about me taking in Wednesday’s game in the company of a real Broadway singing star. That’s no prevarication. Through the machinations of online Mets fandom, social media bonhomie and another kindred spirit with access to really fine (that’s the) tickets, I absolutely found myself sitting practically behind home plate next to Liz Callaway, star of stage and song and, especially, Sondheim. Stephen Sondheim is the nexus where we bonded virtually a few years ago. Sondheim and the Mets, of course. Liz is a serious fan with a voice serious enough to have tamed the national anthem on multiple occasions at Shea Stadium and Citi Field. She recently played a series of shows in Manhattan dedicated to her friend and inspiration Mr. Sondheim, or “Steve” as she honestly comes by calling him. She was acclaimed as sensational. I sure thought so. So did my pals Brian and Mitch, whose feel for vocal artistry is clearly as impeccable as their taste in baseball teams. Brian’s the one who had the bright idea to bring us all together for a game and made it happen.

The Mets, meanwhile, continue to make it happen every day. No lie.

The 1986/2022 comparison, with a touch of 1973, gets a longer look on this week’s National League Town. You oughta listen here.

by Jason Fry on 10 August 2022 1:03 am The Mets won a quiet, even slightly dull game against the Reds … with the lack of excitement counting as a good thing.

Carlos Carrasco was terrific until he found his tank on E. Francisco Lindor and Jeff McNeil homered. Darin Ruf collected two hits, one against a pitcher from the side he’s not supposed to see. A trio of bullpenners we don’t entirely trust — Mychal Givens, Trevor May and Seth Lugo — put up zeroes, though I’ll grant May’s wasn’t particularly elegant.

So what’s ho-hum about that? Nothing! It’s amazing to think that Carrasco is now tied for the N.L. lead in wins, given the horrific season he had last year. Just as it’s been remarkable to watch Lindor wash away the crud and dirt of a star-crossed first season and close in on various Met single-season shortstop marks. And how fun has it been watching McNeil get back to being McNeil, serial abuser of baseballs?

But this was one of those games that felt snoozy once it got started and came with warnings of danger in the middle innings. The Mets drove up Mike Minor‘s pitch count and cuffed him around, but Minor refused to break, stoically giving his team innings and keeping them within shouting distance if not quite striking distance. Carrasco tired in the seventh and before you could blink Jake Fraley had smashed a ball off the Citi Pavilion and the Reds had cut a steep four-run deficit into an all too scalable two.

Suddenly Tuesday’s game looked like one of those where the hare ends up blinking and amazed at the sight of the tortoise ambling across the finish line just out of reach — a forgivable letdown, but one to get the grumbling muscles exercised.

Instead, a couple of good things happened in rapid succession.

First, Buck Showalter called on Givens, the new recruit who’s shown bad body language and worse numbers so far. His assignment was to bail out Carrasco with two men on and Nick Senzel at the plate. Givens passed the test, fanning Senzel, and then Showalter wisely turned to another reliever despite Givens having thrown only four pitches — it was more important to send the former Oriole into the clubhouse on a psyche-restorative high note than it was to spread out the workload the way Showalter would probably have preferred.

Second, the Mets immediately pushed the Reds back down the hill they’d just climbed, with Ruf’s two-run single restoring the four-run lead. Good teams running at full hum do that, beating opponents without working up too much of a sweat. It’s a habit that’s comforting when you’re on the right side of the rooting equation and infuriating when you’re not.

Happily, we can take comfort in it, at least for however long this pinch-me stretch of baseball continues — which I say not out of superstition but out of the sad wisdom that even great teams hit ruts where they seem to have somehow forgotten how to play baseball. Should that happen, though, you get the feeling that Showalter will say the right things, one of the clubhouse’s wise old heads will offer helpful counsel, and then a determined starting pitcher — this year you can take your pick — will decide that it’s on him to change the narrative.

Or maybe there will be a lot more ho-hum wins until the calendar dictates that all spotlights are on full. That would be fine too.

by Greg Prince on 9 August 2022 12:32 pm “All right, Harold. Let’s do it.

“OK, everybody, Buck is available to answer questions. First, Steve.”

“Buck, great 5-1 win tonight over the Reds. In light of the passing of Olivia Newton-John earlier today, do we have to believe this Mets team is magic and that nothing can stand in their way?”

“Aw, is that right? Olivia Newton-John? She couldn’t have been that old. How old was she? Seventy-three? You’re kidding. My wife and I saw her perform one year at some winter meetings or postseason banquet. When I worked for the Diamondbacks, Jerry Colangelo introduced me. What a nice lady. She could really sing. I’m sorry, what was the question? Are the Mets magic? Well, we work hard to do what we do. So does the other team. It would be presumptuous to think nothing could stand in our way. I tell you, though, we got a really solid inning out of Otto tonight. I don’t know if it was magic, but we were happy to get it.”

“Tony, a question for Buck?”

“Yeah, Buck, the great pitching you got from Chris Bassitt tonight, after the kind of outings we saw from Scherzer on Saturday and deGrom on Sunday, do you think opponents look at your rotation, throw up their hands and beg, ‘please, mister, please’?”

“They beg? Nobody in this league begs. I hope they’d have a healthy respect for our pitching and all aspects of our game like we do for theirs. Chris certainly went a long way tonight. What did he go? Eight innings? That’s a big help to our bullpen, which has been so good lately. Did you see Joely on Sunday? Those two-and-a-third were a lifesaver. But, you know, I’ve always wondered about the line ‘please don’t play B-17.’ What do you suppose the song was on that jukebox the button-pushing cowboy had to hear? We try to play everybody who can help us win, but of course we can’t play 17 anymore. That’s hanging up there way above left field. I think Keith would express his displeasure if we were playing 17. He might wanna get a few swings in the cage first.”

“Tim, you’re up.”

“Buck, your team got off to a strong start tonight when Starling Marte muscled a home run for an immediate two-run lead over the Reds. Would you call that a matter of telling your players, ‘let’s get physical’?”

“If we’re doing anything physically outstanding out there, that’s a credit to the training staff. They come in early, they’re keeping the players ready and loose, drinking lots of liquids. This hot weather makes hydration essential. We have a whole lot of guys who can hit the ball far if they find their pitch. Where Starling really excels is the mental game. Francisco, too. What’s the saying about baseball being 90% half-mental? I once asked Yogi at a Yankee old-timers game if he really said that. He didn’t. But if you’re asking about good shape, Tyler Naquin is a specimen. Did you see him go to third on that triple? Of course the first winter Angela and I had cable, that video was all over MTV. There was nothing else on, so we had this crazy new channel on more than we should have, probably. Those guys, the ‘Physical’ guys? They were in great shape. No wonder that was such a big hit.”

“The other Tim.”

“Buck, speaking of great shape, you’re 32 games above .500 for the first time in sixteen years, you’re seven games ahead of the Braves after tonight. But you still have four in Atlanta next week plus a couple of series against a very hot Phillies team. Does that give you enough to tell your fans, ‘don’t stop believin’?”

“I saw that. That many over .500 for the first time since 2006. That was Willie’s team, right? Willie Randolph is a great guy. I’m surprised he never got another shot at managing. He won a division title his second year. I don’t know what happened after that. But let me tell you something. Everybody thinks those lyrics about not stopping believing belong to Journey. Their song got used at the end of that gangster show. What was it called, the one in New Jersey? I should know that, being a manager in New York again. Right, The Sopranos. Great song. You still hear it all the time. Olivia had a different song, a little more country, ‘Don’t Stop Believin,” when I was comin’ up in the Cape Cod League. That’s when I got the nickname Buck supposedly for how little I’d wear in the clubhouse. I’m not gonna tell you to not stop believin’ that story. It’s makes for a good story, whether it’s true or not. As far as the fans, we really appreciate their support. Did you hear how loud it got tonight when Vogie drove in Francisco? I know we didn’t have as many people here as we did over the weekend, but it sounded the same. We have a sponsor, but you could call the ballpark Xanadu if you want. It’s been that good for us. The key to that inning was Pete making their pitcher work. Pete didn’t get a hit tonight, but he saw a lot of pitches. But ‘Don’t Stop Believin’” is a great song. She had so many of them.”

When your team has won of 13 of 15 in July and August, it can be said they are Totally Hot. “Deesha.”

“Buck, your lineup, one to nine, when everybody is going well, could be said to be running deeper than the night. How do you prevent slumps from changing that dynamic?”

“Players don’t have slumps. I know it looks like they have slumps when they go a while without many hits, but there are ebbs and flows in this game and everybody is subject to them. I know I am. I take the same route to the ballpark every day, yet I missed my turn off the Grand Central this afternoon. Can you believe that? They were doing construction and I got distracted, and next thing I knew I think I was practically in Brooklyn. Glenn was gonna be promoted to manager if I hadn’t gotten turned around and I’d be scouting the Cyclones. Wouldn’t be a bad change of pace maybe. But our team prides itself on our consistency. The thing about ‘Deeper Than The Night,’ the song I think you’re referencing, is it was on that album that came out after the Grease soundtrack. My god, that album and that movie were huge. I think I saw it three times the summer it came out. It was the only one playing. You don’t have much of a choice in those minor league towns. Of course they didn’t have streaming then. You just hope too many teenagers didn’t start smoking because of Olivia as Sandy at the end in the leather jacket and all. The album after was called, oh…Totally Hot. That was a real image-changer for her, but she knew she could shift that way after those last scenes in Grease. But to that question earlier, the Phillies are totally hot right now, but we’re not looking past Cincinnati. We think we’re doing OK, too. Anybody else, Harold?”

“We’ll finish up with Mike.”

“Buck, the fan energy around the Mets has always been one that’s kind of a hopeless devotion. Yet you’re suddenly incredibly formidable. Is it some kind of twist of fate that you’re this good? Or are you still worried that the Braves will make a move on you? Can you yourself be mellow?”

“All right, y’all are just playing with me now. Listen, we’re gonna miss Olivia Newton-John. I’m just glad she left us so many great songs. We oughta do something for her here, shouldn’t we, Harold? I mean we had that slogan, the Magic is Back. I wasn’t here then, but I remember that. I thought it was clever, and she had that song at the same time. I’d love to hear her music during BP or between innings. The players might be too young to want to use it for their walkups or whatever. Maybe I’ll just listen on my drive home tonight. Maybe I won’t get lost. But I think our fans can all be hopeful. I don’t think our success to this point is sudden. The coaching staff and myself had a short spring, but we had a lot of willing players putting in a lot of effort and I think you’re seeing it pay off every night. I don’t believe in fate. Too much can go wrong. Atlanta is still capable of going wrong on us if we don’t keep doing what we have to do. Mellow is for after the season and, if we’re lucky, the postseason. We’ll have to keep grinding and make our own moves. Y’all should make a move on the clubhouse. Talk to the players who win these games. They’re the ones that you want.”

by Greg Prince on 8 August 2022 11:25 am The first step toward a decisive Mets victory over the Braves on Sunday came whenever a 1:40 PM start was rescheduled for 4:10. Billy Eppler and Buck Showalter looked ahead at Saturday’s day-night doubleheader and understood their team would be better off with an additional two-and-a-half hours after what loomed as a grueling day. Saturday had the Mets playing nearly seven hours of baseball over approximately nine hours of clock. The Met brain trust saw an opportunity for a little extra rest in the heat of August, in the heat of a pennant race, in the heat of the most crucial head-to-head series of the season. They saw an edge to be had and they grabbed at it. If it was going to provide a little extra rest to the Braves, too, so be it.

Had Sunday’s game started as originally slated, it would have been interrupted by a deluge. By 3 o’clock, Citi Field was withstanding a reported “monsoon”. Hyperbole or not, at best there would have been a holding pattern and uncertainty around first pitch. At worst, the Mets’ first pitcher might have been limited in his utility and a heartily worked bullpen would have been forced into action, throwing sooner than anticipated and maybe more than desired.

The Mets’ first pitcher, oh by the way, was Jacob deGrom. Do you really want one of his starts, let alone his first home start in thirteen months — against the Braves, of all teams — dampened, drenched or possibly set aside out an abundance of caution? Would you prefer a modified all hands on deck situation, the modification being only a few hands were available?

No. You want a 4:10 start that could be easily nudged to 4:30 once the rain passed and the tarp was rolled. You want Jacob deGrom to stride to the mound as if it had never rained, as if the previous thirteen months measured merely five days. You want to feel the complex ecstasy of witnessing the righthander who warms up to “Simple Man”. And then you want what you almost invariably get from a healthy, active Jacob deGrom.

Did Eppler and Showalter know weeks in advance that it was going to rain mid-afternoon in Flushing on August 7 and that deGrom, rehabbing so long, was going to be on track to start that Sunday? Probably not. But I swear I wouldn’t put it past them.

I didn’t know about the rain hours or even minutes in advance. I didn’t know about the rain at all until I glanced at Twitter. There was no rain whatsoever in my neck of the woods, which Google Maps claims is a mere 14 miles south and east of 41 Seaver Way. Seems longer, just as Jake’s absence suddenly seemed much, much shorter. Was he ever gone at all? If he was, why did I feel chills at the first strains of Skynyrd? Why was I so attuned to the ace’s reputation as a matinee idol, pitching even better in afternoons than he does at night, and he pitches wonderfully at night? Before and after the rain, I found a new deGrom anxiety that had nothing to do with injury. We know he’s Sunshine Superman when he starts games in the 1 o’clock hour. Would 4:10 or 4:30 have an impact on him?

Yes. It would make him completely unhittable, as if they invented a new daypart designed for Jacob’s benefit…and the discomfort of Braves batters.

Damn, Eppler and Showalter are clever.

Shadows, sunshine, Superman, Simple Man. Together they struck out practically every Atlantan in sight. Whatever else was going to go right (much) or wrong (vexing in the regulatory realm if not ultimately deleterious), Jacob deGrom held the whole world, certainly our portion of it, in his right hand. He palmed the Braves for five-and-two-thirds perfect innings and slam-dunked them. I normally shy away from non-baseball expressions to describe baseball events, but Jacob is too good to be contained by any one sport.

They didn’t hit him. They didn’t touch him. Until there were two out in the sixth, his predetermined final inning — he’s still building up stamina after his alleged layoff — they may as well not have been in the same ballpark as him. Eighteen straight sliders swung at slid by as strikes instead. Seventeen consecutive Braves made outs. Twelve of them went up on the K counter. If Braves management wanted to get its guys a little extra rest, nine bystanders could have been hired off the street to hold or wave bats while deGrom performed. Same effect.

By the time 4:30 Jake finally revealed a flaw (walking nine-hole hitter Ehire Adrianza) and committed a substantive imperfection (allowing a two-run homer to Dansby Swanson), hastening by one-third of an inning his planned exit, he had been staked to five runs of support. It’s easier to say the Mets never score for deGrom. It isn’t always true. It wasn’t Sunday. Most of the damage inflicted on Braves starter Spencer Strider and his psyche happened in the third inning, during which Met batters and baserunners did the sorts of things they’ve been doing all year long for every one of their pitchers. This bunch seems to like doing favors for Jake as much as they do his staffmates.

Four runs scored in the bottom of the third on two two-run doubles. One of the doubles was struck by Pete Alonso, which isn’t very newsworthy, given that Pete has spent two-thirds of the season driving in more runs than any National Leaguer. Still, watching Francisco Lindor tear around third to bring home the second run was a sight to behold. Not that Lindor being on base is news, either. The second double got a person’s attention, as it was produced by Mark Canha, formerly more or less the regular left fielder, lately a de facto platoon partner to Tyler Naquin. Canha is a righty. Naquin is a lefty. They’d been starting according to matchups. It wasn’t working for Canha, who for much of the first half was reverse-split on-base machine. Buck absorbed that reality and readjusted his plans. Canha the righty batted against Strider the righty and took him to the wall.

Daniel Vogelbach and Pete Alonso celebrate Mark Canha’s doubling in of Vogelbach from first base in the third inning Sunday. That brought Alonso home from second and then, perhaps not a matter of seconds later, Daniel Vogelbach home from first. Daniel Vogelbach is a player I can’t take my eyes off, and not just because he fills so much of my field of vision. You’ve probably seen silent movies in which the walking appears a little sped up, due to the technical limitations of the era. When Vogie takes a pitch (he takes a lot of them) and ambles away from the plate to collect himself, he may as well be Buster Keaton or Charlie Chaplin in motion. It’s not for comedic effect. He moves quickly if not exactly speedily. He knows everything he is doing out there. If he’s come to grips with his limitations, he’s just as determined to take advantage of his capabilities.

One of them is running the bases. From what we’ve seen, he can turn it on when he has to. To score from first on Canha’s double to left-center, he had to. A little flub in the outfield aided his cause, but Joey Cora had no compunction against sending him. Vogelbach was so certain he’d score, he didn’t slide. Daniel doesn’t strike me as the kind of fellow who’d slide just for kicks.

Those were the first four runs accumulated on Jake’s behalf. The fifth came in the fifth, primarily on Jeff McNeil’s moxie, turning a single to right into a double when he determined Robbie Grossman’s arm wasn’t the equal of Ronald Acuña, Jr.’s (Acuña didn’t start in deference to an amalgam of lower-body soreness, moist grass and Jacob deGrom). Jeff continued to factor throwing into his calculus on Canha’s ensuing fly to right. He tagged up and took off on Grossman, alighting on third. A wild pitch cued Squirrel to scurry home. The Mets had five runs with deGrom on the mound. They might as well have had fifty.

It should be noted they very well could have had something on the board prior to the third. In the first, Brandon Nimmo led off with a single. Starling Marte’s right-side grounder got Nimmo thinking. His conclusion was to duck Adrianza’s tag on second. Adrianza laid his glove on Nimmo. Except the ball was in the second baseman’s throwing hand. Second base umpire Jeff Nelson called Brandon out anyway, ahead of Marte beating the relay throw to first.

This would not stand, not within the walls of Buck Showalter’s Baseball Rules Academy, an institution ideally attended for two weeks every winter by every ump everywhere. Buck correctly challenged the out call, as Nimmo was never legally tagged. Matt Olson fired a dart to second after Marte made it to first because the first baseman seemed to grasp Nimmo had altogether avoided the ball. This was a budding reverse Utley situation minus the violence. Chase Utley never touched second in the 2015 NLDS but was somehow awarded it after breaking Ruben Tejada’s leg. Here, replay confirmed Nimmo wasn’t tagged and therefore shouldn’t have been called out. But, in whatever disregard for logic was invoked, Brandon wasn’t awarded second, as it was decided it didn’t matter that he was told he was out, implying Olson’s throw absolutely would have nailed him at second had he kept running to second, which he didn’t because Nelson told him he was out.

The twisted misinterpretation (the Mets work at not being tagged, and they were rewarded for their heady physical agility in Miami earlier this season) cost the Mets a baserunner and maybe short-circuited a rally. Telling the Mets their protest was righteous — they weren’t deducted their challenge — and then penalizing them with an out regardless did not bode well when you were relying on a pitcher for whom you traditionally don’t score enough.

But some traditions wither and die. Like the Mets not supporting deGrom. Like the first-place Mets not fending off the Braves. In late July 2021, after Jake was done for the season, the Mets lost three of five to Atlanta at Citi Field, leaving the door ajar enough so that the Braves figured they could make a bunch of moves and aim for the lead in the East. We know what happened then. We strongly suspect it’s not happening now. At Mets 5 Braves 0, after New York had already taken three of four, and with our ace dealing dejection to opposing hitters, we could feel absolutely sure everything was gonna work out for the best.

Then Swanson hit that homer and deGrom was done after 76 pitches, and the game was turned over to Joely Rodriguez.

Joely Rodriguez. The lone lefty in the bullpen. To the greater conventional wisdom, it was as if there were no lefties in the bullpen. Before the trade deadline, the major deficit the Mets were urged to address was the lack of a reliable lefty. After the trade deadline, the inability to acquire one instigated the rending of garments accompanied by wailing that we had no lefty in the bullpen.

Except for Joely Rodriguez, who was treated as a burden or a liability. If we were lucky, he’d be mostly invisible until David Peterson got the hang of relieving at Triple-A. We’d been luckiest for five-and-two-thirds, riding deGrom and five runs of offense. Now we’d see if what Eppler (he swore he tried to secure a southpaw) and Showalter (he knew he wouldn’t be deploying most every middle/setup reliever normally at his disposal after using them plenty in getting the Mets this far in this series) had designed could withstand the necessity of Joely Rodriguez.

It could. Joely had his moment, his biggest as a Met, even bigger than his contribution to the combined no-hitter, which was fun as hell, but not essential. Sustaining the Mets’ 5-2 lead between deGrom’s departure and the sounding of Edwin Diaz’s trumpets was critical. Not as critical as most everybody is toward Rodriguez’s continued endurance as a 2022 Met, but almost as critical.

What happened? Only good. Rodriguez ended the sixth with a groundout of Olson, a lefty taking care of a lefty. If that was it for Joely’s day, even Ice Cube would say Sunday was a good day. But Buck kept leaning on Rodriguez. Austin Riley’s leadoff single to start the seventh could have been a bad sign, but data from the next six batters indicate it represented a false positive. Joely got pinch-hitter Acuña to fly out. Then he struck out William Contreras and Robbie Grossman. In the eighth, the lefty remained on. Ozuna swung to no avail at Rodriguez’s changeups. Same for personification of a kick in the shins Michael Harris. Adrianza made contact, but only to ground to Luis Guillorme at third.

That’s two-and-a-third innings of scoreless relief from Joely Rodriguez, or the bullpen equivalent of Jacob deGrom going nine or Rob Gardner going fifteen. It was the middle relief stint of the year. It probably buys Rodriguez at least 24 hours of goodwill before the sight of him warming in the pen reflexively gives everybody hives. As with a number of developments this Amazin’ year, you’d have to filed Rodriguez’s heavy lift as one you didn’t see coming.

Conversely, you could feel pretty sure you’d see Edwin Diaz enter in the ninth to protect the three-run lead and once the gate flung open and “Narco” pulsated, you could relax. If you were on edge, you haven’t allowed yourself to experience the full Edwin over the past few months. Or you just enjoy worrying. Concern is always advisable. Worrying is for chumps when you have Edwin Diaz and a three-run lead these days. If Sugar wasn’t fully and completely rested, he’d thrown only seven pitches on Saturday afternoon after giving two innings of himself on Thursday night after not being used at all for nearly a week. Plus there was that start time being pushed back from 1:40 to 4:10 and the rain pushing it back twenty minutes more. That’s sufficient rest for your state-of-the-art closer. Showalter resolutely stayed away from Ottavino, Lugo, Givens, May and Williams. He didn’t need any convincing to go with Diaz for three outs.

Three strikeouts, to be precise. Down went Swanson. Down went Olson. Down went Riley. Down went the Braves swinging on or staring at strikes nineteen times in all, matching the futility of the 1970 Padres versus Seaver and the 1991 Phillies versus Cone. Down went the Braves four times in five games over four days. Up, with this 5-2 triumph, went the Mets’ divisional lead to 6½ lengths, a distance that looks larger and larger the more you stare at it. The Braves rampaged through June and July to reduce their deficit from 10½ a little over two months ago to a piddling half-game barely two weeks ago. Where did all that momentum go?

To meet the Mets and move in with them for the foreseeable future. The Braves will have other chances to pick up ground, but there’s so much more ground for them to traverse after this series than there was before it. Fortunately, Atlanta’s losing pitcher was ready to alibi it all away. Strider, according to Journal-Constitution beat writer Justin Toscano, blamed his subpar outing on the Mets getting good calls — did he see what happened at second base in the first inning? — and “a lot of weird hits”. Strider’s a rookie, but he’s already making excuses like a veteran.

The Mets don’t make excuses. They make plans. Under Showalter, they lead the league in planning. They planned to make the most of something as simple as a Sunday afternoon start time and they finished Sunday evening in characteristic winning style.

As if they’d let the rain, the umps or the Braves get in their way.

by Jason Fry on 6 August 2022 11:41 pm So far — which, I’ll admit right off the bat, is a necessary qualifier — this is one of the stranger successful Met seasons I can remember.

After sweeping a split doubleheader from the Braves — no burying the lead in this recap — the Mets are 30 games over .500 for the first time since 2006.

I remember 2006 as a cakewalk romp, with an impossibly young David Wright and Jose Reyes front and center. Maybe one day I’ll remember 2022 the same way. Maybe it’s simply that 16 years have sanded away all the agita and grumbling so that I just remember the good parts of ’06. Maybe in 2038 I’ll analyze some bit of Metsiana and reflexively reach back for 2022 as the year Pete Alonso and Francisco Lindor blitzed through the NL East and Edwin Diaz struck out everyone in the Mets’ way, and it won’t occur to me to mention the little black cloud that seemed to follow us everywhere.

Because it does, doesn’t it? I swear we’re the unhappiest 30-games-over-.500 first-place fanbase imaginable. And I won’t claim I’m immune. Saturday’s double-header was played with the usual sense of foreboding and klaxons of imminent doom, despite headlines that were very much to our liking, and looking back at it I find myself thinking that it was more than a little ridiculous.

First spot starter David Peterson filled in beautifully in Game 1, giving the Mets 5 1/3 innings of shutout ball while the hitters tormented Jake Odorizzi and a succession of Atlanta relievers with a parade of RBI singles. When Atlanta climbed back into the game with a two-run sixth, the Mets shrugged and added three more runs in the very next half-inning, making their margin even larger than it had been.

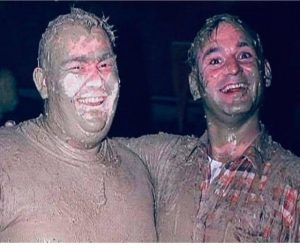

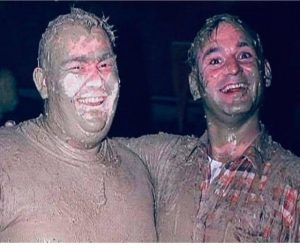

OK, sure, they’d need that margin, as Yoan Lopez was handed a six-run lead for the ninth and gave up a flurry of hits and three runs, with no end in sight. And yes, that forced Buck Showalter to call on Diaz. (Your recapper was at yet another Maine brewery — WHAT? — and decided this called for MLB.tv and not Gameday.)

But happily, Diaz quelled the uprising on just seven pitches, and the Mets won. If that’s what counts as bad news, please give me more of it.

The nightcap belonged to Max Scherzer, who knew the bullpen was on fumes and so made up his mind to be his own bullpen. He didn’t throw a complete game — that would have been malpractice on a sweltering night — but he did give the Mets 108 pitches over seven exquisite innings, the last one a downright savage evisceration of the Braves on unhittable sliders. Four hits, no walks and 11 Ks? That will do nicely, thanks Max.

The Braves looked frankly flat in that second game, though in fairness Scherzer will make a lot of good teams look like less than themselves. They were sloppy in the field, with Dansby Swanson having a particularly miserable game, they were out of kilter at the plate and they generally looked like a tired squad that wanted to be somewhere else. Meanwhile the Mets were on point, whether it was Luis Guillorme firing a ball home to nail Travis d’Arnaud or Tomas Nido executing a textbook suicide squeeze for an insurance run.

Sure, the bullpen wasn’t exactly water-tight once again, with Mychal Givens and Trevor May both giving up runs in their innings of work. Givens is the only newcomer not welcomed with open arms so far, as his command has been iffy at best in two games, but perhaps 41 pitches is too small a sample to consign a guy to oblivion, however much we resent his not being the southpaw we felt we were promised. The Mets won anyway, in a fashion anyone but a professional worrywart would call convincing.

(Oh by the way, my prediction is Peterson ends the year as the lefty we needed.)

The Mets won anyway, despite all the bumps in the night we’re convinced are the ghosts of Chipper Jones and Bobby Cox and Ryan Klesko and Eddie Perez waiting to shred our psyches. They’ve already taken the series, with Jacob deGrom looking to make it four of five on Sunday. They’ve thoroughly outplaying the Braves in their three victories and fought back doggedly in the one loss.

Saturday was a baseball day well spent, so for Pete Alonso’s sake don’t grouse about a glass that’s one-quarter empty. Good things have happened. Rank superstition is the only thing stopping us from thinking more good things will happen. You’re allowed to enjoy things! No, really, I give you permission!

I give you permission because baseball can be cruel and dark, as a fan of any duration can tell you. But it isn’t always like that. And there’s no reason to jump at shadows when it’s sunny.

by Greg Prince on 6 August 2022 2:16 am Every year my friend Kevin treats me to a game against the Braves at Citi Field. Not much of a treat, you might think, the Braves being the Braves, but we waited through the 2010s for the spirit of our mutual favorite Met year 1999 to come back around, and sure enough, it’s Mets-Braves all over again for a large sum of marbles like it was when one millennium morphed into another. Never mind that the Braves tended to take their marbles and go further than us most Octobers when Bobbys Valentine and Cox stared daggers into opposing dugouts. We cherished the rivalry. We’re glad it’s back in earnest in the era of Showalter and Snitker. We like the Mets’ chances to marble up before this season is over.

Theoretically, we might have liked it better had our annual Braves game been Thursday night, which I walked around for months thinking it was gonna be, rather than Friday night, which is what we actually decided on well in advance. Why I believed it was going to be Thursday, I’m not sure. Perhaps I was prescient that Friday would not offer sparkling scoreboard fortune.

Kevin has spent the past 24+ hours earnestly rationalizing that Friday was the better choice. Thursday’s victory turned so stressful toward the end, he said, he’d have had a hard time handling it. Friday worked better against the backdrop of some non-Mets plans of his. Plus we got to take part in the Friday Night Blackout, complete with a complimentary black Max Scherzer uniform number t-shirt (if you must refer to it as a “shirsey,” please have the decency to spell it Scherzey) for all in attendance, not merely the first 15,000 or 20,000 or 25,000. I don’t know that the one-size-fits-some garment would fit Max Scherzer. I know it wouldn’t fit newest Flushing folk hero Daniel Vogelbach — “Vogie!” we hath dubbed him volubly and repeatedly. I’m somewhere between those two fellas on the sizing chart. The shirt will make a lovely tea cozy for me.

I wore black at the Mets’ request. More prescience. I was dressed to mourn the end of a two-game winning streak. Cause of death was the top of the first inning, followed by the top of the second inning. Taijuan Walker started the first. He wasn’t around to finish the second. Bad sign that.

Yes, the Thursday result would have been tastier, but despite an 8-0 hole from which the Mets never fully climbed, Friday with Kevin was more fun than an eventual 9-6 loss (time of game: still going, I’m pretty sure) had a right to be. We never gave up. Not the two of us, not the 40,000 of us, many clad in black, others not caring to be nudged how to dress, even by their first-place team. Walker didn’t stride right, but the bullpen behind him stood tall. Every back bencher who pitched in relief performed well enough to keep the comeback we craved conceivable, and everybody who watched never ceased urging on a team down by eight, then seven, then six, then — as Buck Showalter pushed buttons and pulled levers — four and three. The transitory thrills were provided in the fifth by pinch-hitter Darin Ruf in his first Met plate appearance (two-run double to right) and pinch-hitter Eduardo Escobar (single to bring home Ruf). So much pinch-hitting produced so many pinch-ribbies that we were pinching ourselves, then convincing ourselves the tying run was coming to bat every inning. Maybe it was. Maybe we hallucinated. Wearing too much black in such hot weather can cause mirages.

No, our wishing and hoping and beseeching didn’t do a damn thing to alter the course of events, but fun was had. Can’t say it was the wrong night for that.

|

|