The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 2 August 2025 2:16 pm They changed personnel. They changed locale. Their results didn’t much differ. The post-trade deadline New York Mets lost, 4-3, at Citi Field on Friday night to a San Francisco Giants team that looked familiar, and not just because they were who the Mets took on last weekend, the last time the Mets won a game. Wilmer Flores, who was a Met in the company of Dom Smith, who was a Met in the company of Joey Lucchesi, who was a Met in the company of Jose Butto, who was a Met until the other day, all represented the opposition. Perhaps it confused the players who were wearing Mets uniforms. The whole thing required ten innings to sort itself out. Smith drove in what proved the winning run. There was a time that would have been swell. There was a time the 2025 Mets were swell.

That time can return, you’d think. It’s still mostly the same guys who were in the midst of a seven-game winning streak a week ago. It’s still mostly the same guys who’ve occupied first place more than they haven’t. Not that they occupy first place at the moment, not after the Phillies won while the Mets were losing their fourth in a row. This is the Mets’ second four-game losing streak since they lost seven consecutive in the middle of June. There was also a three-game losing streak in there somewhere. These are not the trends one associates with a first-place team.

To regain the momentum that elevated them to/near the top of their division, the Mets got busy as the deadline approached. We’ve now seen two of the three relievers recently obtained in action, Gregory Soto twice on the West Coast (once for better, once not so much), Ryan Helsley Friday night at home. Helsley is accompanied by a hellacious entrance music and light show, though once you’ve enjoyed your incumbent closer’s entrance music and light show, all you really want to see are outs recorded without fanfare. Helsley rang those bells successfully, striking out three batters in the ninth to keep tied a game that the Mets had just evened, the same one Edwin Diaz would lose, despite all those trumpets. The new late-innings specialist gave up no runs, so that was a small victory within the larger defeat. Tyler Rogers has yet to pitch, so we’ll wait on appraising his first tiny sample size and whatever flourishes soundtrack his appearances.

We also traded for a center fielder at the deadline, Cedric Mulllns, late of the Baltimore Orioles. I want to call him Moon Mullins, because I’m pretty old, but his sanctioned nickname, per Baseball-Reference, is The Entertainer, which makes more modern sense. Cedric didn’t get much of an opportunity to entertain his new audience Friday. He pinch-hit with two out in the bottom of the ninth to no great effect, and was not moved along meaningfully by his new teammates when he returned to the basepaths as the Mets’ unearned runner in the bottom of the tenth. In between, he played an inning in center field, notable because, man, do the Mets need a center fielder, specifically one who can hit.

They didn’t need to find a new center fielder to play center field. They’ve had themselves a fine one all along. Center field has been well covered this year primarily by Tyrone Taylor. The 70% of the earth being covered by water equation disseminated by Ralph Kiner on behalf of Garry Maddox pretty much applies to how Tyrone gets around out there. If David Peterson is an ironman in this age when our mouths hang agape for solid six-inning starts, Taylor is a veritable Gold Glover for tracking almost everything down when he plays. Of course he doesn’t play as often as a regular might because somebody’s gotta hit. Taylor in 2025 has been a center fielder who has barely done a lick of that.

Listen, somebody’s gotta hit from every position within the Mets’ lineup. Friday night, we got a little hitting from Pete Alonso, including his twenty-third home run, which put the Mets on the board when they’d trailed, 3-0, and the deep fly ball that caught the Mets all the way up to 3-3; a little hitting from Juan Soto, when a ball he grounded up the middle caromed off the mound and became an essential eighth-inning RBI; and a little hitting from Francisco Lindor, who preceded Soto’s somewhat lucky shot (Juan’s hit into enough hard outs) with the single that helped build the Mets’ second run. A little hitting from the Mets’ Biggest Three is more than they’d been receiving in San Diego. A little hitting isn’t going to do it.

A little hitting would look fantastic from Taylor. A lineup featuring three slugging stars and a strong second line of support, should be able to carry a glove-first, bat-last fella. Tyrone, who might hit ninth if the pitchers still swung, has taken the defense dispensation to extremes. On June 21, Taylor contributed two hits to the Mets’ 11-4 romp in Philadelphia. Since then, across 28 games, he’s collected six hits in 67 at-bats. In the parlance of trying to get off the Interstate, Tyrone’s been stuck on a state road since summer kicked in.

That, along with the Mets’ effort to fit all their slight irregular square pegs into reconfigured round holes, helps explain why he’s shared much of the available center field playing time with Jeff McNeil, who’s not a center fielder but does get hits. Jeff’s played center well enough. Jeff’s played it like he plays it like he plays every position, by scowling it into submission. You’d rather have McNeil at second base, even if that means you won’t have Brett Baty at second, which you may or not want, anyway, but you would like to get Baty in there somewhere without having to sit Ronny Mauricio, who’s more or less the third baseman now, if it’s not Baty or Mark Vientos, who’s probably the DH, except when it’s Starling Marte.

In the literal middle of all this, welcome Mullins, the new lefty-swinging center fielder, complementing righty Taylor, if we’re being kind. Cedric had one truly excellent season as an Oriole, then one somewhat less excellent, then a couple that got progressively more unimpressive. I don’t want to say “worse,” because I’m trying to stay positive. He’d been hitting well before getting traded, and he can make the plays in center. Maybe that’s enough to make a significant difference for the Mets. Or maybe we’re gonna get lifted by the players we expect to do the heavy lifting, and anything we get out of Cedric will constitute a small but vital boost.

Acquiring Mullins got me to contemplating Met center fielders through time as a species and it occurred to me that almost never is a Met center fielder the player who is front and, well, center for this franchise. We’ve had some splendid ones, a couple who could do it all, more than a few who could some things wonderfully, but in a sport not to mention a city where center fielders have been eternally romanticized, have the Mets ever been “led” by theirs?

A little, maybe. Join me on a selectively crafted and not necessarily thorough 410-foot trip to center, from our beginnings to right now. If the apple of your eye or bane of your existence isn’t explicitly shouted out, you can trust that their names at least flitted through my consciousness amidst this exercise.

Richie Ashburn, a Hall of Fame center fielder, was our first All-Star and perhaps spiritual leader, but he played a lot of right in 1962 before retiring.

Jim Hickman has a claim on most accomplished player in the portion of Mets history that ended prior to 1969, however faint that praise lands, but he also got moved around quite a bit (and, in real time, wasn’t considered someone making the most of his potential).

Cleon Jones became a regular in the majors as the Mets’ primary center fielder in 1966. His marvelous Met future awaited in left.

Don Bosch was, in 1967, going to give the Mets the true center fielder they’d lacked from their inception. He didn’t.

Tommie Agee broke out for two seasons of sensational production from every angle of the game in 1969 and 1970, and that alone is worthy of his place in the Mets Hall of Fame. Honestly, Game Three of the 1969 World Series should have certified his induction. But the Tom who led the Mets in Agee’s day didn’t play center.

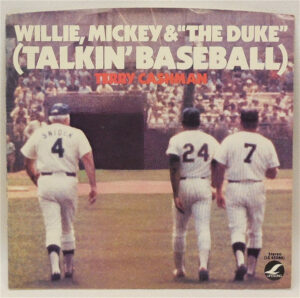

Willie Mays, perhaps the most romanticized of any center fielder anywhere ever — I can think of five songs of the top of my head that mention him prominently — is Willie Mays, and for 95 games, he was center fielder for the New York Mets. I never tire of peering up at No. 24 in the Citi Field rafters and warming all over. But he wasn’t brought back to town after fifteen years to play center field. He was brought back to be Willie Mays. Willie Mays, perhaps the most romanticized of any center fielder anywhere ever — I can think of five songs of the top of my head that mention him prominently — is Willie Mays, and for 95 games, he was center fielder for the New York Mets. I never tire of peering up at No. 24 in the Citi Field rafters and warming all over. But he wasn’t brought back to town after fifteen years to play center field. He was brought back to be Willie Mays.

Don Hahn: Nice defense. Pennant-winner. Didn’t hit. Got traded for Del Unser. Don Hahn: Nice defense. Pennant-winner. Didn’t hit. Got traded for Del Unser.

Del Unser, who benefits from his one full Met season coinciding with the year I was twelve, was an outstanding player for us in 1975. But even I who adored Del Unser as I stood wobbly on the precipice of adolescence didn’t look at a team that featured Seaver, Matlack, Koosman, Kingman, Staub, and Millan, and think, “here come Del Unser and the Mets!” (And there went Del Unser from the Mets in 1976.) Del Unser, who benefits from his one full Met season coinciding with the year I was twelve, was an outstanding player for us in 1975. But even I who adored Del Unser as I stood wobbly on the precipice of adolescence didn’t look at a team that featured Seaver, Matlack, Koosman, Kingman, Staub, and Millan, and think, “here come Del Unser and the Mets!” (And there went Del Unser from the Mets in 1976.)

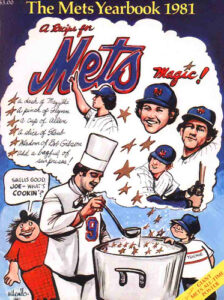

Lee Mazzilli…now we’re talking about a center fielder who led the Mets. In 1979 and 1980, he was the heir to Willie, Mickey & The Duke, not to mention Joe D. He was talented, he was glamorous, and he could do everything very well if you didn’t count throwing. He also got moved to first base before being moved out of Queens altogether. Still, there was a genuine period when if you we’re going to see the Mets, you were going to see Lee Mazzilli and the Mets. You were also probably going to see the Mets lose, but let’s not pin that on Lee. Lee Mazzilli…now we’re talking about a center fielder who led the Mets. In 1979 and 1980, he was the heir to Willie, Mickey & The Duke, not to mention Joe D. He was talented, he was glamorous, and he could do everything very well if you didn’t count throwing. He also got moved to first base before being moved out of Queens altogether. Still, there was a genuine period when if you we’re going to see the Mets, you were going to see Lee Mazzilli and the Mets. You were also probably going to see the Mets lose, but let’s not pin that on Lee.

Mookie Wilson wasn’t a natural leadoff hitter, but he did lead off the rebuilding of the Mets when he arrived in 1980. You could legitimately say the Mets built a championship club around him, promoting and adding piece after piece until it was 1986. Mookie may have been the heart of those teams. We know he was their feet when it mattered most. He wasn’t their face, regardless of how much you were ready to kiss it in the early hours of October 26, 1986. Mookie Wilson wasn’t a natural leadoff hitter, but he did lead off the rebuilding of the Mets when he arrived in 1980. You could legitimately say the Mets built a championship club around him, promoting and adding piece after piece until it was 1986. Mookie may have been the heart of those teams. We know he was their feet when it mattered most. He wasn’t their face, regardless of how much you were ready to kiss it in the early hours of October 26, 1986.

Lenny Dykstra gnawed into Mookie’s playing time, turning Wilson into a part-time left fielder. From 1985, though the platoon he forged with Mookie to win a World Series, to the Sunday afternoon in 1989 he was sent from the visitors’ to the home clubhouse at Veterans Stadium, Nails could be really nails. Never quite made the case to be a regular in New York, though. Philly was a different story, as have been as his post-playing let’s call them adventures.

Lance Johnson (doing some skipping over some short-term solutions and lesser ideas) was a dynamo in 1996. Led our league in hits (227) and triples (21). Still owns both single-season Met records. Probably always will. Stole fifty bases. With Todd Hundley and Bernard Gilkey, stood as the reason to keep watching a furshlugginer ballclub. Traded in 1997.

Brian McRae was who we got for Lance Johnson, and who we’d trade for Darryl Hamilton.

Darryl Hamilton delivered one huge base hit in the 2000 postseason. Sometimes one huge base hit is all you need.

Jay Payton had already usurped center field from Hamilton and the others who’d had their turn-of-the-millennium moments as 2000 grew successful. Big prospect. Long career. Didn’t really and truly click as a Met except in spots. Certainly didn’t last as a Met.

Mike Cameron put together a quietly gaudy season in 2004. Thirty home runs. Twenty-one steals. Exciting defense, which is to say he liked to play shallow but usually caught up to balls. With Cliff Floyd, installed “The Way You Move” by Outkast as that season’s “L.A. Woman,” not that that’s much remembered, because 2004 wasn’t 1999. And Cameron wasn’t long for center field.

Carlos Beltran…he’s Carlos Beltran. He meant a lot of things to the Mets as soon as he signed for seven years in 2005, beginning with ending Mike Cameron’s tenure in center field, and ending with beginning Zack Wheeler’s affiliation in Flushing. As good an everyday player as we’ve ever had. Our all-time center fielder by consensus. Faith and Fear’s Most Valuable Met for 2006, when he had a lot of competition. Gold Glove. Silver Slugger. Many-time All-Star. Got what we paid for. And yet, can’t be called THE Met of his time, not when David Wright and Jose Reyes were the marquee attractions at Shea Stadium and Citi Field. Not that Wright and Reyes would have starred on contending clubs without Beltran doing his share alongside them. The marquee between 2005 and 2011 no doubt implied “and featuring…” for Beltran. Definitely played a huge role in his his era, never quite the defining character of his era. That’s not a knock. It’s relevant only to the notion of the Mets rarely being unquestionably led by their center fielder, whoever their center fielder has been. If it didn’t happen when Carlos Beltran was their center fielder, maybe it’s not fair to expect it to have happened ever.

But it did happen on other teams in the prime of Mays and Mantle and DiMaggio and Trout and Griffey and Dale Murphy, to name a handful of immortals; we’ll omit Pete Crow-Armstrong for the sake of our sanity. It’s not like those center fielders are garden-variety, so perhaps the bar is raised too high. If the Mets could be getting Carlos Beltran-level production in center field today, boy would we take it. We’d take the best of Angel Pagan, which we had for approximately a year (he was here longer); or the best of Juan Lagares, which we had for approximately a year (he was here longer, too); or the best of Brandon Nimmo (who delivered it in center in more years than one, but age shifted him to left). In 2024, we got by with Tyrone Taylor and Harrison Bader, two guys who surely had their ups and downs hitting but caught what needed to be caught, and you almost didn’t notice that they didn’t necessarily hit what needed to be hit. This year, with a powerful enough cast to theoretically excuse a hole in the bottom of the lineup, the top of the lineup has become too hollow to excuse anything.

Center fielder Tyrone Taylor, meet center fielder Cedric Mullins. Neither of you has to be Willie Mays from when he was really the Say Hey Kid. Two or three months making like vintage Mookstra would suffice.

by Greg Prince on 31 July 2025 1:08 am In this emotionally transactional season, when we seem to exchange our adoration for victories and withhold our affection when dealt defeats, the Mets have gotten to transacting in earnest. With the Thursday 6 PM trade deadline approaching, they acquired two high-profile relievers before the sun set on Wednesday. Admittedly, at no time amid San Diego’s 5-0 whitewashing of the Mets late Wednesday afternoon did I think, “We’d really be in this game right now if we had a better bullpen.” But, boy, have I thought that a lot this year.

So now we have a better bullpen. Who knew that thinking about it would bring it forth? More likely, it has something to do with David Stearns and everybody whose input he values thinking we needed a better bullpen. Nobody watching the Mets hasn’t been thinking that. Plan A — try to get by with random relievers attempting to record crucial outs — didn’t work so well. Maybe acquiring guys with good arms and great reps will help.

It won’t help the offense. The offense was helpless against Yu Darvish & Co. at Petco Park, same as it was futile the night before against whoever threw confounding pitches past virtually every Mets batter. The defense hasn’t been so hot, either, and the starting pitchers are still grappling with issues of endurance or performance or both. The Mets were swept three in San Diego. Two of the games were not going to be reversed had the Mets already obtained the services of our newest setup saviors, Tyler Rogers and Ryan Helsley. Maybe one of the games would have had a better outcome with such accomplished relievers bridging starter to closer. Those very relievers will now be asked to accomplish wonders on behalf of the Mets. On this team, three stress-free outs can be a wonder. In this season, when the Phillies shadow us and we shadow the Phillies, one win can make a ton of difference.

Gone, to get Rogers from the Giants, are one guy we previously relied on, Jose Butto; one guy we got a glimpse of, Blade Tidwell; and one guy whose name caused modest stirrings in our prospect-anticipant souls, Drew Gilbert. Gilbert was part of the Steve Cohen Supplemental Draft haul of two trade deadlines ago. The Mets were in a different place with different priorities that July. Getting Gilbert seemed a coup then. The Mets are in another place this July, tenuously in first place, a position requiring the kind of securing Rogers has been brought in to provide.

Helsley from St. Louis cost one minor leaguer I had heard of, Jesus Baez, and two I hadn’t, Nate Dohm and Frank Elissant, which doesn’t mean they don’t have futures. The future is very much the present for these Mets. Recent appearances to the contrary notwithstanding, these Mets were built to win. Yet the present has been leaky of late. It had been solid as recently as the series in San Francisco that preceded the series in San Diego. Our bullpen was fortified by the arrival of Gregory Soto when we were in Northern California. The same Soto took the first loss in San Diego. Rogers and Helsley are probably going to have a bad inning or two, too, which will possibly translate to Met loss or two. The trick here is to trust that established relievers who’ve been having fine years will have many more good innings than bad, which will, in turn, lead to more Mets wins than losses. It all looks so logical before Jeremy Hefner picks up the phone and somebody starts getting loose.

The Mets could definitely use more wins. They’ve suddenly stopped accumulating them. They need more than a better bullpen, but it appears they have a better bullpen, at least. We’ve seen enough innings to tell us that ain’t nothin’.

by Jason Fry on 30 July 2025 12:41 am Back in March, I picked up a “flex book” for the Brooklyn Cyclones — vouchers for 10 discounted tickets, to be used for whatever games I wanted, tickets distributed among them as I saw fit. It was a good idea and thinking about baseball made me happy, so why not?

Then life got in the way: travel, heat waves, miscellaneous domesticity. Earlier this month I got an email reminding me that the season was ebbing away and I hadn’t used any of my vouchers. Which was kind of the Cyclones — after all, they already had my money and didn’t particularly need me.

Then, while I was in Atlanta at Comic-Con, my phone rang. I answered it reflexively and it was … King Henry. Yes, the indefatigably cheerful on-field ringleader of Cyclones between-inning skits. His Highness’s mission was the same as the sender of the earlier email’s: a cheerful reminder that there were fewer and fewer dates left.

(Now, I’m well aware that everyone who works for a team in the low minors does every job — years ago our kid was mystified that the Cyclones employee who wrangled their birthday party somehow vanished before Sandy the Seagull paid a visit and then returned afterwards — but still, there I was at a sci-fi convention chatting with King Henry. Hadn’t had that on my bingo card!)

Tuesday’s heat was miserable bordering on crushing, but I was determined: I was headed for Coney Island. I collected my pristine book of vouchers at the box office, traded one of them for a Cyclones cap in Miami Vice teal and pink, and secured a Brooklyn summer ale and a Nathan’s hot dog.

And you know what? I immediately felt happier. For one thing, it was a good 15 degrees cooler next to the Atlantic Ocean. There were Sandy and Peewee, King Henry and the surf squad, and the Cyclones themselves, wearing blue and pink for some reason. I settled into my (very good) seat, noted the scoreboard had been revamped, and got down to the business of watching Single-A baseball.

Which is so wonderfully different. Watching the Cyclones, I don’t live or die on every pitch. I clap for solid hits or nice plays, try not to groan at misplays (Emily and I used to remind each other that “anything can happen in the New York-Penn League,” and the same is the case in the South Atlantic League), and I smile at seeing only two umps and managers coaching third. I lose track of who’s at the plate, forget the score, and it’s fine. I’m free to simply enjoy the sounds and rhythms of baseball.

By the middle innings the sun had gone down, taking even more edge off the heat, and the neon rings that adorn the light poles at Maimonides Park had started to glow. Beyond the right field corner, the Parachute Jump coruscated merrily, its own vertical light show. I got a cup of ice cream (with sprinkles, of course), secured a 2025 Cyclones baseball card set, and watched the Cyclones and the Jersey Shore Blueclaws do battle.

Said battle didn’t go particularly well for the Cyclones, who fell behind, tied it but then fell behind again. (Unfortunately Brendan Girton, who’s had a nice year as a starter, came out of the game in the second with an apparent injury.) I didn’t see them lose, because by the eighth I’d had my fill and I knew the Mets and Padres were soon to commence hostilities.

So in the eighth inning I left the Cyclones to it — something I’ve almost never done at Citi Field, but which isn’t a sin in A-ball. Life got in the way earlier this summer, but the Cyclones were waiting once I was able to rearrange things, and I was happy to discover how much I’d missed them.

As for the actual Mets and whatever happened in San Diego … oh, let’s not ruin a nice night.

by Greg Prince on 29 July 2025 11:45 am Every time we come to Southern California, we are absolutely the Clampetts.

—President Jed Bartlet

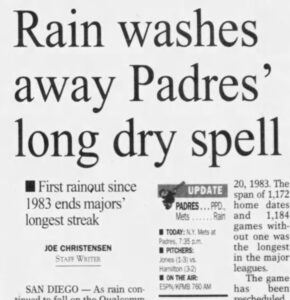

Albert Hammond offered a rather broad assertion in 1972 when he informed the nation’s pop radio listening audience that it never rains in Southern California. Seems it rarely rains in Southern California. On May 12, 1998, the Mets visited San Diego and were, in fact, rained out. The Padres had gone fifteen years between such postponements, but the Mets had been rained out seven times already that young season. Something had to give. When informed his club was the first since 1983 to have the tarp pulled over its plans at the recently rechristened, suddenly soaked Qualcomm Stadium — always the Murph to us — Mets manager Bobby Valentine dryly replied, “Well, I’m glad we’re here.”

More figuratively than literally. Back in New York, I’ve learned to dread Met trips to San Diego because I always expect disaster to unfold late. Maybe “always” should be avoided the way Hammond might have rethought “never” in the face of meteorological aberrations (his song’s No. 5 peak on Billboard notwithstanding), but I’ve seen enough.

• Thirty-two walkoff losses since 1970, the year after the inception of Mets @ Padres interactions.

• Seventeen walkoff losses in the past thirty years we’ve visited the southernmost of MLB’s Southern California outposts.

• Seven walkoff losses at Petco Park before the aesthetically pleasing facility turned eleven.

• And, after a decade of slipping out of town without Met reality meeting my perception, in August of 2024…wham-o!

Jackson Merrill took Edwin Diaz deep to break our hearts on a Sunday afternoon and push the Sisyphean Mets straight downhill, boulder tumbling alongside and perhaps over them. Of course the 2024 Mets, propelled in part by the musical stylings of the indefatigable Candelita, were a pick themselves up, dust themselves off, and start all over again enterprise. Jackson Merrill slaying Edwin Diaz didn’t kill the Mets. At the time, however, I didn’t suspect it would make them stronger.

It’s almost a year later. The Mets entered the East Village section of San Diego feeling strong. The Mets had won seven in a row, four at Citi Field, three at Oracle Park. Neither of those venues is Petco Park, so forgive a weary Mets fan who knew he wasn’t going to make it through nine innings Monday night for bracing groggily for the worst. The single walkoff loss the Mets had experienced in the shadow of the Western Metal Supply Co. building since 2014, the one last year, seemed destined to double.

It did. In the moment, it was a debacle. In the long term, it’s not necessarily a disaster, but they’re all disasters as they’re happening. The seven consecutive wins that served as prelude to this disaster of a debacle/debacle of a disaster figure to cushion the aftereffects of Monday night’s fall. We’re still in first place. We’re still a game-and-a-half up on the Phillies. We’re still in as good a shape as possible despite the Padres inflicting as acute a case of the Mondays on the Mets as one could imagine.

There are dry spells, there are debacles, and there are disasters. Somewhere in there, there are the Padres eventually defeating the Mets in their last at-bat. Mark Vientos hit a grand slam. That’s the good news. He hit a grand slam after an intentional walk was arranged so Vientos could bat with the bases loaded. That was the better news, harking back to the “I took it personal” homer he hit after the Dodgers chose to pitch to him rather than Francisco Lindor in 2024’s NLCS. The bad news is that for the third straight year — and the twentieth time in franchise history — a Met hit a grand slam in a losing cause. One of those hard-luck slammers, in 2009, was Fernando Tatis, Sr., then known as simply Fernando Tatis. The cause was winning when Mark unjuiced those sacks. He’d catapulted the Mets ahead, 5-1. This was after Fernando Tatis, Jr., had robbed Mark of an earlier home run (son of a Met!), and after Juan Soto was robbed of a legitimate ball-strike count by Emil Jimenez. Soto all but dared Jimenez to eject him. Carlos Mendoza stepped between his star right fielder and the judgment-impaired umpire and took the heave-ho bullet instead.

Going to the bottom of the fifth, Vientnos’s granny should have assured us everything was going to be just fine, that we could drift off to sleep without the Padres lurking under the bed coming out to haunt us. Silly me, however, remained awake. I saw the bottom of the fifth. Before the bottom of the fifth concluded, I thought I was seeing the bottom of the sixth from Opening Day 1997 at Qualcomm, just after San Diego forgot how to name its ballpark properly. That was the afternoon Pete Harnisch nursed a 4-0 lead until it died an agonizing death. Harnisch and three relievers combined to give up eleven runs before recording three outs. The season turned out OK and then some, but it didn’t start well.

The fifth inning Monday night disintegrated on contact. Before the game started, SNY’s cameras spotted Frankie Montas in something of a prayer circle with his family, our starter at the railing, his kin in the stands. It was a very touching tableau, and maybe the congregating with loved ones helped Frankie on the mound. He withstood trouble in the second and third pretty well and put down the Pads on seven pitches in the fourth. But in the fifth, “where’s your God now?” felt a reasonable question to wonder.

Tatis doubled off Brett Baty’s glove to lead off. Brett Baty was playing second base at the time. Balls of the second baseman’s glove (Brett dove) don’t usually become doubles, but Tatis had accomplished a bank shot, and the kind of inning the fifth was about to be was more than hinted at.

Luis Arraez, who would have punished Mets pitching before July 28 this year if only he’d batted against it, lofted one of the oddest home runs you’re ever going to see. It was basically a pop fly down the right field line that you never doubted was going to stay fair and go out. Luis Arraez has Luis Arraez power and it comes out in the funkiest ways. It also trims Met leads in half.

In the manager’s absence, Mendoza’s brain trust maintained its faith in Frankie for three more batters. Their faith was not rewarded. Merrill didn’t damage Montas, but Manny Machado (single) and Xander Bogaerts (double) sure did. John Gibbons and Jeremy Hefner said goodbye Frankie, hello Huascar. Mr. Brazoban was an instant faith-rewarder, getting Gavin Sheets to foul out, but the part where a pitcher covers first base flummoxed the reliever on duty. Jake Cronenworth lashed a ball up the first base line. Pete Alonso corralled it (Pete’s in there for his defense), but Huascar chose to watch the play develop before opting to participate in it. Cronenworth beat Brazoban to the bag, allowing Machado to score the run to make it Mets 5 Padres 4. Instead of there being three outs, two hits from the next two batters made it Padres 6 Mets 5. A wild pitch and a walk loaded the bases for Arraez. Yeah, this was going to be April 1, 1997, reincarnated, with Huascar Brazoban as Yorkis Perez, Toby Borland, and Barry Manuel all rolled into one, except Arraez, the Padre contact machine who regularly evokes comparisons to Tony Gwynn, somehow made the third out of the inning.

We were losing by only one run, but the vibe was unmistakably off. And my eyes were soon unmistakably closed, not to open again until I saw a graphic on the screen that announced a final of Padres 7 Mets 6. By then, I was trying to remember if that was the score when I nodded off. It was not. Apparently, Ronny Mauricio homered to tie the game in the top of the ninth, which would have been great to have seen live, then Gregory Soto received his full Met reliever initiation in the bottom of the ninth, which I have to say I didn’t mind missing. In the middle of the rally that permitted the Padres to walk off the Mets for the thirty-second time ever, our newest Soto practically threw a ball away in attempting a forceout at second. The hitter? Candelita himself, Jose Iglesias, last season’s master of the vibe. Jose was with us then. The spirit of OMG was with us then. Now, regardless of the words the Montas family might have shared pregame, forces were conspiring against us. Gregory got two outs, but gave up the game-winning single to Elias Diaz.

It may rarely rain in San Diego, but girl, don’t they warn ya, it pours. Man, it pours.

by Jason Fry on 28 July 2025 8:40 am The Mets fell behind in the fifth inning Sunday night, as Matt Chapman launched a second home run off Kodai Senga. That made the score 3-2 Giants with 12 outs left for making up the deficit.

Funny what a six-game winning streak will do for you. “We’ll get ’em,” I assured my mother, and to my mild surprise I realized that I meant it.

And then the Mets proceeded to go out and get ’em.

It wasn’t as simple as me walking in my mom’s door, uttering this declaration and the Mets making it so (I’m not that good), but it was pretty close.

Ronny Mauricio led off the top of the seventh against San Francisco’s Randy Rodriguez, whose 0.82 ERA didn’t necessarily suggest confidence, to say nothing of hubris. Rodriguez’s second pitch was a slider in on Mauricio’s hands — not a bad pitch by any stretch. Mauricio showed off his uncanny bat speed by getting around on it and his easy power carried it out over the wall and into McCovey Cove, where I was glad to see it was scooped up by a kayaker and not the hedge-fund guy zooming around on some kind of Jetsons mini-hydrofoil. (If said guy is actually a tinkerer who heads a non-profit for removing microplastic from the ocean, well, my apologies.)

Mauricio may be wearing another team’s uniform by the weekend, and that might turn out to be a good deal for the Mets. But it might also be one we rue as bitterly as, say, Javy Baez for Pete Crow-Armstrong. (Ouch!) Mauricio has turned heads this year, mine most definitely included. The bat speed and power are rare gifts, but he’s also shored up his defense and cut down on the chasing that many thought would keep him from being a front-line MLB player. He finished Sunday 4-for-4, with a pair of doubles and a single in addition to the homer, and if you’ll forgive a bit of sabermetrics jargon, that shit will work.

Mauricio’s transformation of a baseball into a submersible tied the game. An understandably piqued Rodriguez then used his deadly slider to erase Brandon Nimmo and Francisco Lindor, but left a fastball in the middle of the plate to Juan Soto, who clubbed it into the left-field stands to give the Mets the lead.

Newcomer Gregory Soto looked good in his Mets debut, showing no nerves as Carlos Mendoza started constructing the new bridge to Edwin Diaz. Reed Garrett and Brooks Raley got the Mets to the ninth, with back-to-back Mauricio-Nimmo doubles offering an insurance run.

Which turned out to be a good idea, as Diaz was shaky for a second straight day, loading the bases with one out on walks sandwiched around an HBP. The tying run was a single away, with a woeful walkoff too close for comfort, and Willy Adames and Chapman due up.

Diaz, as he often does, seemed to awaken to his peril and snap into focus. He retired Adames on three fastballs up in the zone, all looking and also all strikes. He then stayed with the fastball and the upper bounds of the strike zone against Chapman, putting the fourth pitch of the AB up on Chapman’s hands. Chapman committed, couldn’t get around on the pitch, and the Mets had won their seventh straight and completed a three-game sweep.*

Had it all the way, right? At least I’d thought so. It’s nice to be right on occasion.

* Tip of the cap to the woman in Mets garb spotted in the stands who’d brought along a full-size broom as a celebration accessory. Beyond the fear of waving a red flag in the faces of the baseball gods, I don’t think I’d want to be the guy lugging around a large broom after my team failed to sweep. Or even after they succeeded, come to think of it.

by Jason Fry on 27 July 2025 10:58 am On the surface, Pete Alonso and Rafael Devers aren’t that different: Huge dudes who can hit the ball a country mile and whose huge dude-ism means they aren’t particularly mobile. As has been the case since time immemorial, that means they play first base — which is where the similarities start to break down.

Alonso isn’t a great first baseman by any stretch, and it’s damning with faint praise to note that the Polar Bear has worked his furry white behind off to become at best an average one. But the hard work is real, Alonso takes enormous pride in playing the position, and he seems to genuinely enjoy it. Alonso’s range is suspect (though he has at least mostly stopped diving for balls better left to the second baseman) and his throws can go awry, but he’s become genuinely adept at saving his fellow infielders by scooping errand throws out of the dirt, a part of playing first base that’s always struck me as both difficult and potentially perilous. Saturday continued a two-game stretch in which Alonso made play after play when the Mets desperately needed him; on Friday night Clay Holmes was the beneficiary, while on Saturday it was David Peterson.

Devers, on the other hand, is at first base as the culmination of a series of dissatisfactions. He wants to play third, with the only problem being that he pretty much can’t. Which led to the Red Sox moving him to designated hitter in favor of Alex Bregman, then asking him to play first after an injury to Triston Casas.

Devers, understandably annoyed at being asked to play Position No. 3 after not wanting to play Position No. 2, refused and soon found himself getting paychecks from the San Francisco Giants … and now playing first base. As has also been the case since time immemorial, Devers’ attempts to elude fate have only accelerated its arrival.

Saturday night was Devers’ third-ever game at first, and it isn’t going well. To his credit, he did make a nifty scoop in the top of the fourth, which completed a double play and kept the Mets off the scoreboard. But mostly he looked like he was fielding grenades over there — blink your eyes and a ball was on the ground somewhere near Devers’ feet, with a whole bunch of large man in that ball’s general vicinity scrambling for a Plan B.

For a while it looked like the Giants might survive Devers’ misadventures: In the fourth they clawed a lone run out of Peterson, who didn’t look particularly sharp but offered a clinic in bending and not breaking. Unlike his counterpart Robbie Ray, Peterson was helped out by his fielders, with Brett Baty, Francisco Lindor and Alonso all making key defensive plays.

In the sixth inning the bill came due for Devers and the Giants: With one out and runners on first and second, Baty smacked a grounder to first. Devers made the start of a nifty play, turning to throw to second and start a double play. But the finish was less than nifty: The ball popped out of his hand before he could load up for the throw. Devers recovered and stepped on first to retire Baty, but that gave the Mets an extra out, and they capitalized.

They capitalized when Mark Vientos lashed a ball down the left-field line. Vientos had struck out with the bases loaded and nobody out in the fourth, the first fizzle of a fallen inning, and has had a miserable year so far, looking nothing like the breakout star who helped key the Mets’ playoff run last year and played so remarkably in the postseason. But hey, any day can be the first day of the rest of your life, right? Vientos delivered, turning a 1-0 Mets deficit into a 2-1 Mets lead and ending a trying day for Ray.

The teams trundled along scorelessly after that, with Reed Garrett and Ryne Stanek holding the Giants at bay and a bevy of Giants relievers including Old Friend Joey Lucchesi keeping the Mets on the leash. Edwin Diaz was handed the ball to secure the save, and this is the place where our friends in the Giants fanbase should say “well anyway” and go read something else.

Diaz didn’t have it. He threw got two strikes on Casey Schmitt via sliders off the plate, but left a third one in the middle of the strike zone, which Schmitt smashed on a line to left field — right into Baty’s glove.

Stubbornly throwing nothing but sliders, Diaz left another one in the middle of the plate for Jung Hoo Lee, who crushed it to right. It hit that multi-angled nightmare of a brick wall, two or three feet shy of being a game-tying homer, and Lee cruised into second looking faintly disappointed.

Diaz belatedly opted for the fastball, using it to set Mike Yastrzemski up for a bait slider and a strikeout. That left the Giants’ hopes up to Patrick Bailey, who ripped another errant slider over first base, ticketed for the corner. It would score Lee and send Bailey to second, with God only knows what else tacked onto the play given the uncertain geography of that right-field corner.

Except Alonso leapt into the air, various limbs flailing for purchase, and caught the ball. He came down, kissed the possibly still smoking ball, Diaz exhaled about 100 cubic feet of dismay, and the Mets had somehow secured their sixth straight win. Reviewing the key moments this morning I’m still not sure how they did it, but hey … you could look it up.

by Greg Prince on 26 July 2025 11:40 am Friday night’s was the kind of game you were glad to stay awake for and through. The Mets jumped out to an early lead in San Francisco, built a substantial lead as things reached their midpoint, and tacked on late. Late is pervasive where West Coast start times are concerned. The first inning was late. The ninth inning was technically morning. But all of the innings registered collectively as positive, as the Mets won their fifth consecutive game, routing the Giants, 8-1.

So, the big, bad Mets we recall from slices and chunks of April and May and the first half of June are back, right? Right?

Don’t all assent at once, just consider…

• They’re in the midst of a legitimate winning streak.

• They lead their division.

• Their leading man, Francisco Lindor, is acting as if his bat had never fallen into an abyss.

• Their long-running Dean, Brandon Nimmo, is spry as a sophomore.

• Their quintet of kids — Masters Acuña, Alvarez, Baty, Mauricio, and Vientos — are together on the roster for the first time ever, each lately contributing a little here, a little there, none making us wholly regretful of his presence.

• Pete Alonso is playing defense.

• Juan Soto is driving balls up the middle.

• Tyrone Taylor and Jeff McNeil are regularly tracking such orbs down.

• Clay Holmes is gutting out five effective if not efficient innings, which is OK, because we have Rapidly Recidivized Rico Garcia back, following the ten minutes when he’d inexplicably wandered away from the organization, and Rico will have help when lefty Gregory Soto arrives from Baltimore.

This Soto, poised to become the first Met ever to go by Gregory (my mother, who named her only son after Gregory Peck, would have appreciated that), figures to enhance a deepening bullpen, provided he doesn’t implode more than once or twice, as all bullpen acquirees do as a rite of passage…and all Met relievers do on occasion.

The Mets have occasionally looked lost. If you judge “lost” as their default mode, they’ve provided ample samples to support your conviction. But they’ve also, on multiple occasions, looked like they’re not going to be beaten in a given game or string of them. That’s the appearance they put forth in their sweep of the Angels and at the beginning of their series against the Giants. The Giants are a contender. They threw an ace at the Mets in Logan Webb. The Mets threw him right back, and stole his lunch money in the process (I’m assuming Logan Webb keeps his lunch money at second base). Just one game. Just five games. Just sixteen games over .500. Just a half-game ahead of the Phillies. It’s at least as compelling as the part of the season where they slipped and slid and unnerved us plenty.

In addition to an assortment of outfits like the Giants — 2025 strivers scrapping to emerge from a Wild Card fray and play another day or more come October — Major League Baseball features a top tier of teams that have eluded wire-to-wire perfection while intermittently making cases for themselves as genuine championship threats. Toronto. Detroit. Houston. Milwaukee. Chicago in the form of the Cubs. L.A., as in the Dodgers. Philadelphia, phooey. That other New York assemblage, the one implicitly represented by the giraffe that inevitably stumbles in Citi Field’s not choreographed in the slightest Borough Mascot Race. Ours is one of those top teams, too. Dragged by downs that detract from the ups. Elevated by ups that ought to overshadow the downs but don’t always. We’re all almost great. We’ve all got something preventing us from indisputable excellence. Time awaits to tell all our tales. Only one will be repeated warmly and widely for the ages.

Every really good team may be the equivalent of Mike Piazza when we first got him or Juan Soto now that we have him. Piazza and Soto were ALWAYS great in highlight packages, and, according to our clearheaded perspective, ALWAYS killed us. Then they became Mets and we saw double plays grounded into and pop flies that ended rallies and the stuff of mere mortals. Great? If he’s so great, why isn’t he batting a thousand like he did before he became a Met? THIS IS WHY WE CAN’T HAVE NICE THINGS!!! Conversely, we experienced the entirety of David Wright, which is to say the groundouts and strikeouts that didn’t make the montages last weekend, let alone the uninterrupted images of excellence that probably haunted fans of our opponents the way Piazza pre-1998 and Soto pre-2025 haunted us, except who the hell wanted to talk to fans of our opponents to find out what they thought about anything? We lived with David every day of his career, so we might have been skewed from believing he was predominantly phenomenal. No man is a hero to his valet, no idol doesn’t go 0-for-4 while leaving eight men on.

Few reasons to stew right now. There’s good in a season. There’s bad in a season. As many times as we’re repeatedly reminded “you’re never as good/bad as you look when you’re winning/losing,” the blend remains eternally perplexing. Yet when you’ve got as many ingredients for good as these Mets do, and they’re cooking together delectably, maybe try to enjoy a hearty spoonful before deciding in advance that the next taste will be a little off.

by Greg Prince on 23 July 2025 6:29 pm “Wanna watch the Mets play the Angels?”

“What’s gonna be in it?”

“Mike Trout.”

“Didn’t he used to be great?”

“A great is a great. Wanna watch?”

“What else is gonna be in it?”

“Travis d’Arnaud.”

“Doesn’t he always kill us?”

“Not necessarily. Wanna watch?”

“What else is gonna be in it?”

“A bullpen game.”

“One of those things with no starters? Don’t those suck?”

“They can, but sometimes they’re OK if there’s a real starter on the right side. Wanna watch?”

“What else is gonna be in it?”

“Balls being called strikes at a critical juncture.”

“Isn’t that terrible umpiring?”

“Probably, but perspective matters here. Wanna watch?”

“What else is gonna be in it?”

“A leadoff homer.”

“Won’t the Mets be behind if there’s a leadoff homer?”

“There are leadoff homers and then there are homers that lead off the home team’s first inning, hint, hint. Wanna watch?”

“What else is gonna be in it?”

“Francisco Lindor.”

“The guy who hasn’t had a base hit in ages?”

“Slumps end, hint, hint, hint. Wanna watch?”

“What else is gonna be in it?”

“Pete Alonso.”

“The slugger who hasn’t hit a home run in ages?”

“Like I said, slumps END, sometimes resoundingly. Wanna watch?

“Gee, I dunno. Can you promise me I’ll be happy if I do?”

“I can promise you you’ll be sorry if you don’t.”

“OK, let’s watch.”

“Too late. You missed it because you asked too many questions.”

“What happened?”

“Read between the lines.”

“What does that mean?”

“Again, with the questions.”

by Jason Fry on 23 July 2025 2:04 am I decided it was time to reintroduce myself to my baseball team.

The Mets entered the All-Star break by losing an annoying game to the Royals, which isn’t exactly a new occurrence in 2025. I didn’t bother with the ASG beyond shrugging at the swing-off, and was relieved to have a few days’ break from this maddening Mets squad, which is seemingly hell-bent on being less than the sum of its parts.

Then a few days turned into a few more. When the schedule resumed I was in Atlanta at a sci-fi convention; I registered that the Mets were losing to the Reds, not doing anything particularly well in the process, and hearing boos from the fans. I wasn’t sad to miss that either. (I did regret not seeing David Wright going into the team Hall of Fame, of course, but that’s something I can catch up with at my leisure.)

The Mets salvaged the final game against the Reds, to my mild surprise given what had come before; I was on a plane without Wi-Fi when they commenced hostilities against the Angels on Monday night. Once the plane landed, Howie Rose caught me up in a hurry: They’d gone down 4-0, clawed back to 4-2, but seemed determine to dig the hole deeper.

More of the same; I groused about their suckiness on Bluesky as I waited for a Lyft to take me home.

But I kept an earbud in, and by the time I got home the Mets had a genuine threat going — one they cashed in with a little help from the hapless Angels. (OK, maybe a lot of help from the hapless Angels.) Edwin Diaz started off the ninth by missing to his arm side, but quickly corrected the issue and punched out three Angels, ending the game by freezing Taylor Ward on a perfect slider a pitch after nearly decapitating him with a fastball, which was honestly kind of mean.

I was mollified, and maybe even felt a little bad — my team had been annoying me, I’d lashed out at them, and they’d righted the ship. So on Tuesday, when I saw it was a gorgeous summer day blissfully free of the humidity that’s gripped the city of late, I had an idea: Let’s go see the Mets.

I mean, why not? Isn’t that the whole point of living near the team you love? Why waste a picture-perfect night sitting on the couch?

Emily liked my thinking, so I secured two StubHub tickets and met her at the apple.

Tuesday’s game began strangely, with a flurry of odd plays. Juan Soto threw out Nolan Schanuel at the plate, taking an RBI away from Mike Trout. Frankie Montas ended the first by fielding a ball off his body. Yoan Moncada hit a screaming line drive that Pete Alonso leapt and speared; Alonso saw a long drive to center tracked down by Jo Adell. There were bleeders up the line and parachutes over the infield and plenty of frustration for Montas.

Kyle Hendricks, meanwhile, took a 2-0 lead into the fifth, having surrendered nothing except a Mark Vientos single that should have been caught. The Mets were being peaceable at the plate again, with Francisco Lindor‘s struggles particularly glaring, and the big boisterous crowd at Citi Field was getting restless.

And then everything changed. Brett Baty lashed a double to center, bringing up Francisco Alvarez, and I nudged Emily and made the circle in the air sign: Alvarez was going deep.

That didn’t look like the savviest prediction when Alvarez started off the AB by taking a huge swing through a change-up from Hendricks. But he hung in there, fouling away off-speed offerings and refusing to be lured by an inside fastball he wouldn’t have been able to get around on. Hendricks tried that pitch again, left it in the middle of the plate, and Alvarez tattooed it into the left-field stands, careening happily around the bases while I nodded sagely, as if my predictions always come true.

The game was tied; Ronny Mauricio then singled, stole second and came home on a single by Brandon Nimmo to give the Mets the lead. Which they then stubbornly refused to expand, leaning on relief efforts from newest Recidivist Met Rico Garcia and Reed Garrett, with Baty contributing a marvelous grab at third.

No, they just had to do it the hard way, summoning Ryne Stanek to protect a one-run lead. That looked tenuous after Stanek immediately allowed a single to West Islip’s own Logan O’Hoppe, who sounds like a 70s pitchman for Irish Spring. Stanek struck out Luis Rengifo, coaxed a fly ball from Zach Neto, but then gave up a single to Schanuel. That brought Trout up with a chance to tie the game on a single or possibly do far worse, what with being Mike Trout and all.

But of course Trout hasn’t been that Mike Trout in a while, his rocket-ride trajectory redirected earthward by years of injuries. On Monday night Diaz erased Trout on three fastballs that had a lot of plate; with the Angels threatening to expand their lead on Tuesday, Montas overpowered him with fastballs that were frankly middle-middle. Then Garcia got him with a slider that sat in the middle of the plate.

Stanek got Trout to pop up harmlessly to Alonso, ending the game. There’s a matinee left to play, but so far in this series Trout has looked like Just a Guy. And while I’m glad the Mets won, that part has been quietly heartbreaking.

by Greg Prince on 22 July 2025 11:58 am For weeks on end, the Mets have been given lemons and we made sour faces at the way they played, little lemonade in sight. On Monday night, the Mets were given Angels. They and we chowed down on Angel food cake. It wound up being a much sweeter experience.

Not at first. The Mets had to fall behind early. As proven Sunday, it’s not necessarily so bad to let the other team build a lead and a false sense of security. It’s probably bad that the Angels from Anaheim by way of Los Angeles built a large lead of 4-0 by the third inning and that it was constructed against Kodai Senga. Senga is one of the pillars of our rotation. When Kodai crumbles, it would figure we’re all in trouble.

But that’s why we’ve got Kevin Herget. I assume that’s why we’ve got Kevin Herget. FYI, Kevin Herget is back with the Mets. FYI, Kevin Herget was once with the Mets, for one game in late April. Then he was shuffled off the active roster so the Mets could add Brandon Waddell. Waddell would be optioned to add Genesis Cabrera. Cabrera would be DFA’d so Waddell could be recalled again, by which time Herget was pitching for the Braves (once).

Got all that? Don’t worry if you don’t. When it comes to relievers you’ve probably forgotten were ever here, the Mets will always make more…or bring a couple back.

On the same day the Mets re-signed Rico Garcia, who’s not yet on the active roster but might very well bump from it someone like Kevin Herget or perhaps Kevin Herget himself, Kevin Herget pitched for the Mets, therefore making Kevin Herget the 59th Recidivist Met overall. A Recidivist Met is a Met who played for us; left to play for somebody else; and returned to play for us anew. Emotional homecomings are a part of Recidivist Mets lore: Tom Seaver and Rusty Staub spring to mind immediately; Lee Mazzilli and Hubie Brooks trail right behind. A couple of weeks ago, Travis Jankowski was glad to be back. He’s gone again. It sometimes works that way. Amid 2024’s version of the bullpen shuffle, we brought in Michael Tonkin and Yohan Ramirez; got rid of Michael Tonkin and Yohan Ramirez; and brought back Michael Tonkin and Yohan Ramirez. Their respective interim absences weren’t much longer than their combined multiple tenures. We said hello, goodbye, hello again, and goodbye for good to both relievers before the middle of May.

The Kevin Herget Mets story may have very well peaked on Monday night. If so, nice apogee for the latest Mr. Prodigal. Herget righted the ship Senga steered astray, pitching scoreless ball in the fourth and the fifth, leaving with one out and one on in the sixth, no damage done. While Kevin was stabilizing the situation, Brett Baty was improving it, socking a two-run homer in the bottom of the fourth. Chris Devenski, who by dint of being recalled on July 4 and not being sent down since may be the second-longest tenured Met reliever of all time (I’ll have to check) gave up a run in the seventh, but the game was still within reach at 5-2.

The Angels’ conceivably reachable lead bolstered my confidence. The Mets staying within striking range after not falling hopelessly off a game’s competitive map when they very well could have may provide a more promising platform for victory than an early one- or two-run lead that isn’t added to ASAP. Urgency can be enigmatic. The Mets ahead tend to nod off. The Mets not dead are capable of livening up. And, if we allow ourselves a moment to not pin the Mets’ fate solely on the Mets, the Mets were playing the Angels. There was some “there for the taking” ripening in evidence. There is a reason the Los Angeles Angels rarely rise to heaven.

Senses of what might happen are swell, but an actual comeback is what you really want. From down 5-2 and at last eliminating Angel starter Tyler Anderson with two on with nobody out in the seventh, the Mets got to coming back in earnest. Brandon Nimmo stood in the right place, in the path of a Reid Detmers delivery, thus getting dinged and loading the bases. Francisco Lindor, whose last hit coincides with the last hit featuring the Temptations probably (I’ll have to check on that one, too) bounced to short but ran like he had ten fully intact toes to beat out a double play. The Mets had their third run, and they had runners on first and third. Then they had runners on second and third, because Lindor liked running so much, he took second uncontested while the Angels thought ethereal thoughts.

What a setup for Juan Soto, who’s hit harder balls, but few better placed. This one, in the seventh, zipped straight up an unoccupied middle, scoring two, including Lindor, who’d placed himself on second with that no-biggie steal. Nice planning. Nice tie.

At 5-5 heading to the eighth, it was time to consider the bullpen again. Every bullpen, certainly every Met bullpen, has its transients and it has its staples. This one has Brooks Raley, who belongs in the latter cohort, but you wouldn’t know it by his recent lack of game logs. While some of us devoted our ruminations to David Wright, Brooks (same name The Captain gave his son) suddenly appeared as if from out of nowhere on Saturday afternoon,. Yet Raley really hadn’t been nowhere. He’d been recovering from Tommy John surgery in 2024; on the free agent market a little; then — to the surprise of those who take attendance to confirm who’s no longer in the Mets classroom and mark them permanently graduated from the hallowed halls Payson Tech, pending Recidivism — back in the organization. We were told Raley, one of the few bright spots of relentlessly dim 2023, was working his way back from his operation. Whenever he was good to go was great. It seemed folly to count on Brooks Raley to pitch for the Mets this season.

Except we kept getting reports that his track was fast, his progress was apace, and would you look at that? Brooks Raley pitches for the Mets again. He’s not a Recidivist Met, because he never technically went anywhere else, but he sure appears to have returned from somewhere. A lefty arm we can count down is like something that falls out of the sky but not on our head. In the eighth on Monday night at Citi Field, Raley landed on the mound and threw a scoreless inning to keep things tied at five.

So now we’d witnessed the comeback of Kevin Herget and were reminded of the comeback from Brooks Raley. Yet for the Mets to come back not only in this game but to what we wish to believe they are, they needed Francisco Alvarez to come back. On Monday, the catcher we’ve been waiting to achieve his presumed destiny returned from a month in the minors. His presumed destiny was stardom in the majors. Had we not seen it in the distance, maybe we’d have signed JT Realmuto instead of James McCann in the first minutes of Steve Cohen’s ownership. No need for a star catcher, we’re raising one of our own. Alvy approached his projected heights when he homered like crazy to light up the less dark parts of 2023. He regressed offensively in 2024, but he was part of a playoff push, so we didn’t dwell on the youngster’s shortcomings. In 2025, we couldn’t ignore them. Nor could Mets management, thus the Summer in Syracuse program, in which the ballclub sponsors a deserving kid from the city and sends him to experience a taste of farm life whether he wanted it or not.

Francisco seemed to have made the most of it, judging by several facets of his game Monday night, one of which was his ability to work a walk to lead off the home seventh ahead of those vital Lindor and Soto contributions; another of which was a caught stealing he worked with his shortstop in the top of the seventh; and still another of which was the tag he placed on Mike Trout to limit an accumulation of Angel insurance runs. This was in the seventh as well, Baty throwing, Alvarez catching, Trout sliding nowhere near the plate, perhaps to protect his previously injured knee. About as bad a fundamental play as I’ve ever seen a surefire Hall of Famer make, but somebody had to tag him, and young Francisco took care of that detail.

Alvarez had more work to do in the eighth. Following Baty’s one-out walk, Alvy lined a ball to the right field wall. Chris Taylor didn’t defend it as much as attempt to withstand its presence in his midst. It may or may not have been a catchable ball. Taylor opted to not find out. It appeared catchable enough that Baty made it only as far as third. Alvarez, meanwhile, chugged to second, which one can assume he enjoyed a whole lot more than being in Syracuse.

What happened next continued to indicate good things can happen when a) you put the bat on the ball and b) you hit it toward the Angels. Ronny Mauricio produced a fielder’s choice grounder to third. Yoan Moncada choice was to throw it wide of home. Logan O’Hoppe choice was to drop it. Bret slid in safely and untouched to push the Mets in front. Nimmo then made contact of his own, a sac fly to right that paved a glide path for Alvarez to score. It was 7-5, Edwin Diaz was available, and Edwin Diaz was on, striking out the side for his twentieth save and the Mets’ second consecutive comeback victory.

Mets take their inspiration where they can get it. Afterwards, the players gathered around the clubhouse television to watch an episode of The Beverly Hillbillies just to get to the song that plays over the end credits, specifically the line where Jerry Scoggins invites everybody watching, “Y’all come back now, y’ hear?” (That’s one more detail I’ll have to check on, but based on these past two games, it sure seems true.)

|

|

Willie Mays, perhaps the most romanticized of any center fielder anywhere ever — I can think of five songs of the top of my head that mention him prominently — is Willie Mays, and for 95 games, he was center fielder for the New York Mets. I never tire of peering up at No. 24 in the Citi Field rafters and warming all over. But he wasn’t brought back to town after fifteen years to play center field. He was brought back to be Willie Mays.

Willie Mays, perhaps the most romanticized of any center fielder anywhere ever — I can think of five songs of the top of my head that mention him prominently — is Willie Mays, and for 95 games, he was center fielder for the New York Mets. I never tire of peering up at No. 24 in the Citi Field rafters and warming all over. But he wasn’t brought back to town after fifteen years to play center field. He was brought back to be Willie Mays. Don Hahn: Nice defense. Pennant-winner. Didn’t hit. Got traded for Del Unser.

Don Hahn: Nice defense. Pennant-winner. Didn’t hit. Got traded for Del Unser. Del Unser, who benefits from his one full Met season coinciding with the year I was twelve, was an outstanding player for us in 1975. But even I who adored Del Unser as I stood wobbly on the precipice of adolescence didn’t look at a team that featured Seaver, Matlack, Koosman, Kingman, Staub, and Millan, and think, “here come Del Unser and the Mets!” (And there went Del Unser from the Mets in 1976.)

Del Unser, who benefits from his one full Met season coinciding with the year I was twelve, was an outstanding player for us in 1975. But even I who adored Del Unser as I stood wobbly on the precipice of adolescence didn’t look at a team that featured Seaver, Matlack, Koosman, Kingman, Staub, and Millan, and think, “here come Del Unser and the Mets!” (And there went Del Unser from the Mets in 1976.) Lee Mazzilli…now we’re talking about a center fielder who led the Mets. In 1979 and 1980, he was the heir to Willie, Mickey & The Duke, not to mention Joe D. He was talented, he was glamorous, and he could do everything very well if you didn’t count throwing. He also got moved to first base before being moved out of Queens altogether. Still, there was a genuine period when if you we’re going to see the Mets, you were going to see Lee Mazzilli and the Mets. You were also probably going to see the Mets lose, but let’s not pin that on Lee.

Lee Mazzilli…now we’re talking about a center fielder who led the Mets. In 1979 and 1980, he was the heir to Willie, Mickey & The Duke, not to mention Joe D. He was talented, he was glamorous, and he could do everything very well if you didn’t count throwing. He also got moved to first base before being moved out of Queens altogether. Still, there was a genuine period when if you we’re going to see the Mets, you were going to see Lee Mazzilli and the Mets. You were also probably going to see the Mets lose, but let’s not pin that on Lee. Mookie Wilson wasn’t a natural leadoff hitter, but he did lead off the rebuilding of the Mets when he arrived in 1980. You could legitimately say the Mets built a championship club around him, promoting and adding piece after piece until it was 1986. Mookie may have been the heart of those teams. We know he was their feet when it mattered most. He wasn’t their face, regardless of how much you were ready to kiss it in the early hours of October 26, 1986.

Mookie Wilson wasn’t a natural leadoff hitter, but he did lead off the rebuilding of the Mets when he arrived in 1980. You could legitimately say the Mets built a championship club around him, promoting and adding piece after piece until it was 1986. Mookie may have been the heart of those teams. We know he was their feet when it mattered most. He wasn’t their face, regardless of how much you were ready to kiss it in the early hours of October 26, 1986.