Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

As August 1988 came to an end, the New York Mets were one full season removed from a championship and looked like a good bet to add more flags over Shea Stadium. The team’s formidable starting staff had been bolstered by the dynamic right arm of David Cone, who’d established himself as a star, and the powerful lineup had been given a boost by the recall of one of the minor league’s most exciting rookie hitters.

Gregg Jefferies had been able to buy a legal beer for less than a month, but he was already a phenomenon, at least semi-famous for the ferocious, exhausting practice regimen he’d honed with his father and the punishment he’d inflicted on minor-league pitching.

Certainly New York heard him coming. He’d had a cameo the previous September, going 3 for 6, and Davey Johnson had reluctantly left him off 1988’s Opening Day roster. Johnson had never had much use for “leather guys,” but others in the organization convinced him that Jefferies’ glove needed to catch up with his bat before he could be a starting player. Not to worry: Everyone connected to the team seemed confident that would happen soon enough. And if not, well, Mets GM Joe McIlvaine assured the world that “we’ll create a position for him.”

If that sounded cavalier, the bat spoke loudly enough to drown out any caveats. The Mets had drafted the 17-year-old Jefferies in the first round of the ’85 draft; he’d hit .353 in ’86, then .367 in ’87, with 20+ homers and steals. His 1988 season at Tidewater wasn’t as otherworldly — Jefferies hit .282 — but he was called up in August when a hamstring injury felled Wally Backman and a viral infection took down Dave Magadan.

The kid proved more than ready: two hits in his first game, three in his second, Player of the Week honors soon after that. His swing was gorgeous — a tight, lashing curl of wrists and hips that sent balls flying, and was identical whether he was hitting left-handed or right-handed. Jefferies hit .321 in 29 games as the Mets coasted to a division crown, started all seven games against the Dodgers in the postseason, and hit .333 with no strikeouts. The season ended with a thud, but the Mets would be back, with Jefferies front and center.

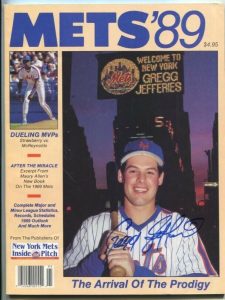

As the ’89 season approached, Jefferies was inescapable. He was the poster boy for most every baseball preview, with the Mets’ own magazine bearing the decidedly immodest headline THE ARRIVAL OF THE PRODIGY.

I was probably Gregg Jefferies’ biggest fan. I’d never seen the debut of such a heralded rookie. I salivated over what he’d done in his abbreviated time in ’88, and breathlessly imagined what that stat line might translate to over a full season. Not to mention — because why stop there? — what a career along those lines might look like.

There was something else, too. Jefferies was less than two years older than me, and the idea of a baseball player who was my contemporary was new and intoxicating. I’d become a fan when players were impossibly old, on the far side of the grown-up/child divide, but Jefferies could have been in school with me. My career, whatever it turned out to be, would unfold alongside his.

And there was a something else to go with the something else: Jefferies was really good at what he did, and I felt the same way about myself. I couldn’t wait to see what he did; I couldn’t wait to see what I would do. I worked through these sentiments in a poem, of all things, one that’s been lost to history and I devoutly hope will remain unfound. A little while later, when one of my college roommates cracked that I liked Jefferies because he was the Met most like me, I made a show of protest but was secretly pleased.

The Mets went north for the ’89 season with Jefferies at second base. And then it all went so, so, so wrong.

The prodigy didn’t hit at all for the first two months of the season. That got better, to a point — he wound up at .258 — but the fielding never did. Jefferies had been moved to second because he wasn’t good enough to play shortstop in the majors, but he looked miscast at his new position, with particular trouble hanging in on the pivot play. Johnson, a former second baseman himself, stubbornly insisted the kid could be taught to play the position; every game seemed to offer new evidence to the contrary.

And the conversation around Jefferies stayed loud, but this time it was for all the wrong reasons.

It was soon an open secret that Jefferies’ teammates hated him. They thought he was Davey’s pet, a baby, and a brat. That kind of thing usually wasn’t allowed to leak out of a clubhouse, but the late-80s Mets leaked like a dysfunctional White House, and sports-talk radio was starting to bloom into the poisonous flower it would become.

And Jefferies proved regular grist for this cynical mill. He made a fetish of his signature-model black bats, rubbing alcohol on them after games to spot the points of contact. He pouted after poor at-bats and misplays in the field. None of it would have mattered if the kid had outhit his personality, but he didn’t. And as the bad buzz got louder, the past came to look more like a warning that had gone unheard.

Sports Illustrated had profiled Jefferies in the spring of ’88, detailing his obsessive workouts with his dad, a former college infielder. It had all been a bit odd, but we were all too busy salivating about Jefferies’ arrival to care. Now, in hindsight, the SI portrait seemed a bit creepy.

There was the detail that the Jefferies family would gather around their big-screen TV (a rarity in those days) after hours-long workouts to watch video shot by Gregg’s mom and analyze his swing. Or the fact that Jefferies’ parents had stayed away for all of two days after their son started pro ball, then showed up and wound living in a trailer in his host family’s backyard. For 10 weeks. Or the fact that he’d asked them to do the same thing the next summer, and they’d agreed. Or the little detail that the license plates on Jefferies’ blue Camaro read 4 FOR 4 GJ.

Really? What kind of person had a license plate like that? Who became a pro ballplayer with his parents in permanent residence? Even Jefferies’ banter with his father during their marathon workouts sounded slightly artificial. We didn’t have this vocabulary at the time, but it was like the uncanny valley that plagues videogame recreations of people. Jefferies sounded like an AI pretending to be a person.

Again, he might have outhit all that — certainly he had the talent to do so. But he didn’t. And it crushed his career as a Met.

The sniping continued. Jefferies, no longer a rookie, was pranked and picked on by actual rookies. His beloved bats were dumped out of their special bag and left in the middle of the clubhouse. A teammate wrote ARE WE TRYING? by his name on the lineup card. Facing the Phillies’ Roger McDowell, who’d been his teammate just months earlier, Jefferies grounded out to end the Mets’ disappointing 1989 season. McDowell taunted him as he ran to first, prompting Jefferies to wheel after touching first and rush McDowell. The season was over, but there were two recent teammates scrapping on the bottom of a pile of Mets and Phillies — a pile in which Jefferies had more enemies than friends.

It never got better. The stories continued in 1990, the year of this profile. How Jefferies had been a handful in the minors, berating official scorers and cursing so loudly and vilely as he came off the field that fans complained. (His Tidewater manager, Mike Cubbage, tried to shame him by asking him how he’d feel if his mother heard that; Jefferies said she’d heard it all before.) Even the sympathetic profile pieces penned later felt off — Jefferies collected memorabilia of Elvis Presley, who’d died when he was 10, and idolized Ty Cobb, who’d died when his father was a teenager. In 1991 Jefferies penned an ill-advised open letter to Mets fans, which was read on WFAN, came off as more whining, and prompted an equally ill-advised open letter from Ron Darling, who was normally smarter than that. The joke in the Mets’ clubhouse that year was that Howard Johnson had been born again because his choice was to embrace Jesus or go to prison after murdering Jefferies.

Finally, as the smoking rubble of 1991 cooled, the Mets gave up on the future. They sent Jefferies to the Royals along with the surly Kevin McReynolds and utility man Keith Miller in return for Bret Saberhagen and Bill Pecota.

Jefferies would get to relax in Kansas City, though the Royals never found a position for him either. He put up a couple of stellar years for the Cardinals, who made him into a first baseman despite his being short of stature and right-handed, then played for the Phillies and the Tigers. A bad knee derailed his career; the kid who was going to break Pete Rose‘s hit record retired in 2000 at 32. He was 2,663 hits short of the record.

I registered all that vaguely. I’d been aghast at Jefferies’ failure to launch and the clubhouse miseries that had surrounded him; when he was finally sent off to Kansas City I couldn’t quite bring myself to admit I was relieved. After that, to be honest, I mostly wanted him to go away. He was a reminder of everything that should have worked and somehow hadn’t, of embarrassment masquerading as triumph.

What happened? Some of it, in hindsight, wasn’t Jefferies’ fault. He was dropped into a close-knit clubhouse of hard-nosed, old-school players. They didn’t like his awkward personality or his obsessive ways, but more than that they didn’t like that his being hailed as the future meant they’d soon be part of the past. They resented that Backman was traded away to make room for him, that the veteran Juan Samuel was pressed into service in center field, that accommodation after accommodation was made for him.

Jefferies was also a new breed of player — a forerunner of the travel-team kids who’d emerge from family cocoons, having been all but bred for stardom by helicopter parents as conversant with signing bonuses as they were with swing paths. Earlier this year, Joel Sherman spoke to Jefferies and some of his old Mets tormentors. He found many of Jefferies’ nemeses apologetic about their refusal to accommodate the new kid, and Jefferies magnanimous in response.

It’s an interesting piece, but I didn’t find it terribly convincing. It felt more like proof that Jefferies’ tormentors had mellowed over time and surrendered to the idea that schoolboy ballplayers come with entourages. “What was thought of as spoiled then is commonplace now,” Cone told Sherman, which was meant as a mea culpa but works equally well as an indictment. As for the relationship with his parents, Jefferies defends it as supportive and loving, and rejects the idea that he was stage-managed. I hope so, but I’m not sure how he would know differently. Stockholm syndrome is a helluva thing.

Jefferies really was a prodigy — that short, sharp, vicious swing is still a thing of beauty on YouTube — but being a prodigy isn’t enough. Blame his own self-absorption, and his teammates’ lack of generosity, and management’s callousness in putting him in an impossible situation. (And, as always, some plain old bad luck.) He was supposed to be a bridge between eras, but the bridge couldn’t handle the weight it was forced to carry. And the Mets wouldn’t go anywhere until the wreckage had been cleared away.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1964: Rod Kanehl

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1969: Donn Clendenon

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

2000: Melvin Mora

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

After Doc and Straw, I feel like the Mets organization at that time thought their player development was infallible. Yes, there were other good homegrown guys like Mitchell and Aguilera and Myers, but then they started hyping others way beyond their value. Loved Dwight Gooden? Well wait til you see David West!

But Jeffries was the pinnacle of the overhyped prospect, and everyone involved learned their lesson the hard way. I still wonder how many guys currently about 45-50 years old and still very reliant on a paycheck thought they’d be retired by now thanks to hoarding Gregg Jefferies rookie cards.

Ron Darling’s name always seems to come up when this type of immature and inappropriate behavior is involved.

Let’s not forget the brawl in a Houston bar when he and others were arrested, or his ‘tell-all’ book when he made up that story about Lenny Dykstra, who was much more valuable to the team, and more loveable and representative of those Mets than Darling ever was.

Jealousy, perhaps?

And let’s not forget the time he was publicly offended when he was getting shelled in the first inning, and he complained like a child, when Davey started warming up someone in the bullpen.

A final note: When Keith is not there, the games are virtually unlistenable due to the neverending boredom of the broadcasts, due to Darling having no personality whatsoever.

It’s unpopular to have this opinion, but I agree 100%. I’ve always felt Ron is the weak link in the three. He’s good at analyzing pitching but says the most head-scratching things, on a regular basis. In general he is not a good describer of the proceedings.

I’ve always had mixed feelings about young Gregg (I’ve always thought of him as young Gregg). On the one hand, he was a lamb thrown in among one of the scurviest crews ever to don the orange and blue (and I say that with love). On the other hand, he did come across as an immature brat – for example, the WFAN letter was one of the more cringy moments in Met history. He was, as I said of another Met last week, in the wrong place at the wrong time. But he unquestionably brought a good deal of his suffering on himself.

That cover, though. Once again I’m reminded of Jeff Francouer and his SI cover. “Can anybody be this good?” – Turns out that that’s a Nope.

How did KC not find a position for Jefferies? Not even the fake position??

Also, I am driving my finger nails into the desk in anguish over the lack of a link for David Cone’s name in the table at the bottom. It’s… not… blue. Selective OCD. – Okay, *I* would have understood Jefferies back then. -.-

Okay, upon closer inspection the ’92 Royals stored George Brett’s assorted memorabilia at DH while waiting for him to get shipped to Cooperstown. Bad timing then.

Coney isn’t blue because he already got mentioned higher in the piece. The little app thingy that links names to Baseball Reference files only hits the first mention.

I know this because it bothered me too.

Great minds think alike? Something like that? :-P

[…] I’ve Seen the Future and It Doesn’t Work » […]

[…] Gentry 1973: Willie Mays 1977: Lenny Randle 1978: Craig Swan 1981: Mookie Wilson 1982: Rusty Staub 1990: Gregg Jefferies 1991: Rich Sauveur 1992: Todd Hundley 1994: Rico Brogna 1995: Jason Isringhausen […]