The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

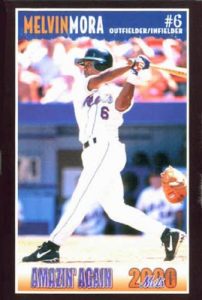

by Greg Prince on 19 May 2020 4:17 pm Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

I am determined to take our best traditions into the future. But with all respect, we do not need to build a bridge to the past. We need to build a bridge to the future, and that is what I commit to you to do. So tonight let us resolve to build that bridge to the 21st century…

—President Bill Clinton, 1996

There was a time when the 20th century was the only one any of us knew, when the concept of the 21st loomed as too outrageous to realistically contemplate. Even as “the year 2000,” as we reflexively called it, beckoned just up the road, it still struck us collectively as unknowable. Perhaps to prepare us for the mysteries of Y2K and the impending millennium it would usher in, we were granted a transition tool known as the 1999 Mets. They were a team that stretched the bounds of reality late in the last century for as long as they could.

With 73 days to go in the 1900s, the Mets played a baseball game they have yet to equal for sheer insanity in the 2000s. It wasn’t over until there were 72 days to go in the 1900s, and it came directly on the heels of one at least as lunatic, which they played when there were 75 days to go.

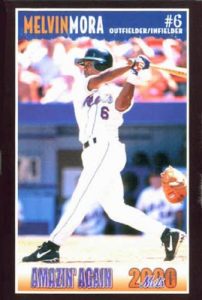

Time was flying just as we were having the most fun of our pre-millennium lives. Also flying everywhere he needed to be was Melvin Mora, one of the ornaments of the inimitable 1999 stretch drive and playoff spurt. Mora was one of those players who made 1999 what it was, even if he didn’t arrive to stay until it neared its conclusion. But then he made it better. He made it his own.

The Mora era began in earnest in the bottom of the ninth inning of October 3, 1999, the Mets knotted with the Pirates, 1-1, in Game 162, the game the Mets needed to win to guarantee they’d have a Game 163 and a chance at the jewels that waited beyond. After two topsy-turvy weeks that topped off a topsy-turvy year (that hadn’t seen anything yet), the Mets and Reds were tied for the National League’s sole Wild Card. The Mets were well-equipped to grab it. It was the year of Piazza, the year of Ventura, the year of Alfonzo, the year of so many 1999 Mets.

But when it mattered most, it was the moment of Mora.

Melvin — we were instantly on a first-name basis — came up with one out, following Bobby Bonilla not coming through as a pinch-hitter, and lined a single to right field off Greg Hansell to imbue Shea Stadium with the fierce urgency of hope. So many stars twinkled in our sky in 1999, yet here was this distant light coming into focus to show us the way.

The autumnal festival of Mora had commenced. In what flickers through the frames of the mind’s screening room as quick succession, Edgardo Alfonzo singled; Mora flew to third; John Olerud was intentionally walked; Gene Lamont replaced Hansell with Brad Clontz; Clontz warmed up; Mike Piazza stepped up with the bases loaded; Clontz went into his delivery; Clontz’s delivery skittered past catcher Joe Oliver; and Melvin Mora…

Well, Melvin Mora was now at the heart of the Melvin Mora Game. We’d call it that forever because, as Oliver chased the pitch that got away and Piazza stood appropriately dazed in a state of inoperativeness, Melvin — who spent two-thirds of the day on the bench, then worked the box score as PR-LF-RF-LF the rest of the way — dashed from third to home. There was no doubt he was going to cross it safely. The last few steps, almost for show, turned into a duckwalk. Quack, quack, quack; the secret word is “playoffs”.

A one-game playoff, anyway. At the end of Game 162, with Robin Ventura leading the charge of the hug brigade and the Mets beating the Pirates, 2-1, we celebrated as if we knew there’d be more playoffs. If it didn’t read as a foregone conclusion in the standings, you could guess confidently that we were going places.

Mora is partially obscured by a hugging Ventura, but after scoring the winning run of his namesake game, he’d never be obscure again. First, to Cincinnati, to break the Wild Card tie. The Mets gave miracles a rest and opted for excellence. It was one of their underlying conditions in 1999. They didn’t win 96 games for nothin’. In fact, thanks mainly to Rickey Henderson leading off with a single, Edgardo Alfonzo following Rickey with a two-run homer, and Al Leiter giving up only two hits over nine innings, they won a 97th, 5-0, which punched their ticket to their next stop: the NLDS in Phoenix.

It didn’t really matter where the Mets’ next game was going to be. The important thing was that there were going to be next games. There hadn’t been since 1988. It would be too simplistic to say “no wonder — there hadn’t been Melvin Mora, either,” but, actually, yeah. One gets the feeling that Melvin Mora, had he been insightful enough to arrive in some other season, would have pushed the Mets an extra step. He would have kept Mike Scioscia in the park in 1988; would have neutralized the Bonilla & Bonds Bucs of 1990; would have convinced Vince Coleman to roll up his window in 1993; would have held together 1998 when it was falling apart.

But you can only ask Melvin Mora in retrospect to do what Melvin Mora actually did. The lithe Venezuelan product wasn’t born until 1972, didn’t sign a professional contract until 1991, and needed to play a little in Taipei in ’98 to draw attention to talents that went undetected during his looong tenure in Houston’s minor league system. The Mets noticed, signed him, invited him to Spring Training in ’99. He tore up the Grapefruit League. Howie Rose referred to him as the mayor of Port St. Lucie. It wasn’t enough to get him elected to the Opening Day roster. Melvin Mora didn’t appear in a major league game — for the Mets or anybody — until May 30, 1999.

Mora started that day. And on July 17. And July 25. Otherwise, he served as a spare part for an engine that was revving on most cylinders most of the time. Defensive replacement. Pinch-hitter. Pinch-runner. Then, after the trade deadline yielded Veteran Experience, back to Norfolk, see you in September. Which we did, mostly in late innings.

Mora’s magic at the end of games (one in particular) was the reason the Mets had somewhere to be in October for the first time in eleven years besides on their way home. Mora helped bring them to Phoenix to take on Randy Johnson and the fancy 100-win Diamondbacks. The Diamondbacks had more wins than the best Mets team of its generation, and nobody’d ever heard of them until a couple of years before. Then again, none of us had ever heard of Melvin Mora until the previous spring, so it was a fair fight.

Melvin’s first postseason appearance came in the sixth inning of Game One, a little earlier than usual, but this was the playoffs, and Bobby Valentine’s state bird was the double-switch. Masato Yoshii was coming out. Dennis Cook was coming in. “BUT,” as the announcer on the commercials would say, “THAT’S NOT ALL! YOU ALSO GET MELVIN MORA IN FOR SHAWON DUNSTON!” It was always Melvin Mora in for somebody, with somebody else going out so a reliever’s spot in the batting order would take its time coming around again. Melvin Mora was the perfect cog for Bobby V’s constantly cranking game-management mechanism.

In the ninth inning, the Big Unit was Buck Showalter’s irreplaceable cog. He’d thrown what amounted to two starts in the Diamondbacks’ first-ever postseason game. In the first one, the Mets nailed the perennial Cy Young winner good. Fonzie homered. Oly (a lefty!) homered. Even Rey Ordoñez bunted a run home. The imposing Johnson was apparently no bother to these Mets.

Then, in the fifth, Randy Johnson got back to being serious, and the Mets could no longer touch him. Around the same time, Yoshii remembered he was no match for Randy Johnson and, before Valentine could pull his double-switch, the game was tied at four, which is where it was in the ninth. Robin Ventura singled to lead off. Roger Cedeño bunted unsuccessfully. Ordoñez, practically having the offensive game of his life (1-for-3, plus that sacrifice), singled to left. Rey batted eighth. Pitchers usually bat ninth in the real league here, but because Bobby V played as many dimensions of chess as was necessary to outpoint his opponent, he had Melvin Mora up in this crucial spot in this crucial juncture of this crucial game.

Crucially, Melvin walked. Not only did it load the bases, it forced Showalter’s hand. Out went Johnson. In came Bobby Chouinard. Two batters later, Chouinard gave up a grand slam to Alfonzo to give the Mets an 8-4 lead that became an 8-4 win. Mora’s run made it 7-4. Mora’s walk off the Unit, just like Mora’s hit against Hansell, made all good things possible.

Melvin just kept it coming as the series proceeded. Valentine didn’t use him in the Game Two loss and didn’t need him to more than caddy in the Game Three win, but in Game Four at Shea, with the Mets poised to advance in a postseason for the first time since 1986, Melvin’s presence became crucial once more. In for defense in the eighth, the utilityman’s utility explained itself in a hurry. A 2-1 lead carefully nurtured by Leiter dissolved into a 3-2 deficit that resulted from Jay Bell’s two-run double off Armando Benitez (gosh, usually he’s so reliable). The game threatened to get away once Matt Williams singled and Bell steamed toward home, but the left fielder — Mora — fired in to Todd Pratt to nail Bell and keep the Mets down by only one run.

Pratt’s name will be attached to this game after he homers in the tenth, but who knows if there’s a tenth without Mora in the top of the eighth? Not only does Melvin imbue the concept of “defensive replacement” with game-changing impact, but we saw in the bottom of the eighth that moving fielders around doesn’t come without risk. Tony Womack had started at short for Arizona. Showalter shifted him to right and, two batters in to his new station, Womack muffs a fly ball that sets up the tying run.

Too bad for Buck that he didn’t have Melvin. Much better for us that we did.

In the NLCS that Mora and Pratt (among others) facilitated, Melvin’s defense, particularly his arm, was on full display. In Game Three, Melvin throws out Bret Boone at the plate from center in the first. In Game Five, Melvin throws out Keith Lockhart at the plate from right in the thirteenth. The Braves were given extra innings to scout Mora’s skills — he’d been playing the whole day and changed positions twice — but they chose to attempt to run on him, anyway.

By the thirteenth inning of Game Five — the Grand Slam Single Game, as it’s known for eternity — Melvin Mora has played 41 innings of postseason baseball and has recorded an assist from each outfield position. Plus he’s hit the first home run of his major league career in NLCS Game Two. Oh, and in Game Four, with the Mets as backed against the wall as can be imagined (though the imagination would be given a strenuous workout in the games ahead), he walks in his first plate appearance, in the eighth inning, concentrating on getting on base while Cedeño is busy stealing second base. Then, as the trail runner, he engineers a double-steal with Roger, placing them on second and third for Olerud. Then he scores the winning run on Olerud’s single, something he was situated to do because of that double-steal.

In Game Six, the third must-win contest the Mets have contested in a 72-hour span, word is getting around on New York’s erstwhile secret weapon. When Mora comes up in the top of the eighth as a pinch-hitter for Orel Hershiser, score tied at seven, Benny Agbayani on second, Bob Costas and Joe Morgan spotlight over NBC the “27-year-old rookie” most nobody had heard of when October began.

Melvin “has a chance to be a star,” according to Costas. “At least the Mets think so. He’s shown his stuff down the stretch and in the playoffs.”

“He’s going to be a valuable asset to the Mets in the next few years,” affirms Morgan, who lists the “lot of little things to help you win” that Mora does, which he ticks off as “plays good defense”; “has a good arm”; and “swings the bat pretty well.” Those little things sound mighty big. Mora is mighty big in the scope of this game, as he’s been in so many games since he got on base versus the Pirates a little over two weeks before. He singles to center and brings home Agbayani.

“Melvin Mora, who only a few years ago was playing in the Chinese professional league in Taiwan,” Costas marvels, “gives the Mets the lead in Game Six.”

How good was this guy? Darn good. Yes, indeed, the rookie who “does not have any fear,” according to Morgan, has put the Mets up, 8-7, in a game that seven innings earlier they trailed, 5-0. It’s been crazy, it’s been a team effort, and now it’s Mora more than anybody else levitating the Mets until they can outlast the enemy Braves. Hold onto this lead, go to Game Seven. Win Game Seven (like they’d lose it after getting there), go to the World Series. Go to the World Series, and the world will know the legend of Melvin Mora as it continues to unfold before its eyes.

Except Bobby Valentine doesn’t move Mora to the mound, which is a mistake in retrospect, because Mora, who’s played three infield and three outfield positions in 1999, can do it all, and Franco, Mr. 400+ saves, gives up the tying run. The game will go to the tenth, Mora will come up, having stayed in as the right fielder, and again, Mora does it all, or at least all he can do. Agbayani is on second again. Mora singles again. Benny goes to third before scoring on Pratt’s fly to Andruw Jones, of all people. The Mets are ahead, 9-8, in the tenth inning of the sixth game of the National League Championship Series, an NLCS whose first three games they lost, and an NLCS from which they’ve courted elimination so steadily that you’d think somebody would have put a ring on it.

But Melvin Mora keeps the Mets and their chances going together.

MORGAN: “How good is this guy?”

COSTAS: “Darn good.”

Mora doesn’t pitch the bottom of the tenth, which dawns after midnight. Benitez does and gives up the tying run. Mora doesn’t bat in the top of the eleventh. It’s not his turn and the Mets don’t score. Mora doesn’t pitch the bottom of the eleventh, either. Kenny Rogers does. He’s not darn good. The Mets and the 1999 season break up. Their dissolution was as inevitable as their romance was beautiful.

But this, ostensibly, isn’t about 1999. It’s about 2000. That other wildly successful Mets year. The one that felt different. The one that was different. The one that had Melvin Mora at its beginning rather than its end.

***The good news is there was going to be 2000. We’d get through the 20th century and cross the bridge into the next one. The computers and lights would stay on, and life would resume pretty much as it functioned in 1999. Parochially speaking, this meant we could look forward to Melvin Mora on the New York Mets. True, the element of surprise wouldn’t burst from every swing he took or every throw he gunned, but we had him. World, you’ve been warned.

Melvin makes the team out of Spring Training. Melvin goes to Japan as a bona fide component of the defending Wild Card champs/NLDS winners (the banner has never been succinct). Melvin is on base when Benny Agbayani slams grand to win the Tokyo finale in the eleventh inning, an early-morning outcome that feels like something the 1999 Mets would have concocted.

Except it’s not 1999 anymore, which by default is the bad news. Where’s John Olerud? Where’s Orel Hershiser? What are Derek Bell and Todd Zeile doing here — and in Japan? If Jerry Seinfeld had awakened pre-dawn to watch the Mets and Cubs (he was in the stands at Turner Field for Game Six, so maybe he was at the Tokyo Dome, too), he might very well have asked, “Who are these people?”

These people were the 2000 Mets. They’re not exactly the 1999 Mets, but they’re plenty good. What they lack in that certain something, they make up for with comparable competitive capabilities, which isn’t nearly as romantic as that certain something. No, it never is 1999 again, but the millennium odometer had made that explicitly clear.

Melvin Mora is still pretty much Melvin Mora, which is a very 1999 sign for 2000. On April 20 at Shea, in the tenth (the bottom of an inning when he’s been double-switched into the game), Mora steps up and homers off Curtis Leskanic to give the Mets a 5-4 win over Milwaukee. It’s his first major league home run, not counting the one he launched off Kevin Millwood in the playoffs…though why wouldn’t you count a home run you hit in the playoffs?

The Mets’ sights were aimed directly at a return to the playoffs from the moment they took flight for Tokyo. It wasn’t going to be easy. In the Bobby Valentine era, no matter how much talent the players provided the manager, and no matter how much wizardry the manager provided the players, it never was. They wouldn’t have been the Mets of just before and just after the millennial divide had it been. Their road got bumpy as hell in Los Angeles on May 29 when Ordoñez, who bold-typed the “Best” in “The Best Infield Ever?” (and definitively deleted its question mark), went out for the year with a broken forearm. Even Rey-Rey, who introduced himself to MLB by throwing out a runner at home from his knees, needed a forearm to play short. Ordoñez’s defense was irreplaceable. His offense, however, was always ripe for an upgrade.

Enter Melvin Mora, fresh from a brief DL assignment himself, as the starting shortstop of the 2000 Mets. His status as a supersub had followed him into the new century, but the Mets now had Super Joe McEwing to fill that role (with at least as much as versatility, if not as much flair), along with Kurt Abbott, who had played the position in previous seasons (and whose continued presence in 2000 was yet another reminder that 1999 was a once-in-a-lifetime year). Melvin had hit another home run since beating the Brewers, which gave him two on the season, or two more than Rey-O had produced. Melvin’s postseason defense had drawn rave reviews from the outfield, but he was billed as a shortstop when he came to St. Lucie prominence two Marches before. It would be a tradeoff, but the Mets didn’t have much of a choice

Sadly, they didn’t have much of a shortstop in Melvin Mora. It was jarring to watch him not pick up ground balls after four-plus seasons of Rey Ordoñez erecting and patrolling a veritable force field between second and third. Rey played 154 games at shortstop in 1999 and made four errors. Melvin Mora made seven errors in a 26-game span that covered late June to late July of 2000. Ordoñez was a high bar. Even Ordoñez wasn’t clearing it before his injury (six errors in 44 games), but between Mora in for Ordoñez and Zeile in for Olerud, nobody was asking any longer whether this was The Best Infield Ever.

Instead, they asked if there was something more the Mets could do about shortstop. Mora was contributing offensively as an everyday player, adding four homers to his ledger and coolly and calmly accepting ball four on a three-two count to build the legendary ten-run rally of the eighth inning of June 30. It’s most famous for Mike Piazza’s three-run laser of a homer. Usually unnoted is that it was Mora who scored the run to tie things up at eight. Melvin hadn’t lost his knack for making the Braves sweat late in games that were cluttered with runs.

What Melvin would lose before July was over was his role as starting shortstop for the New York Mets. His parking space, too. He was traded to the Orioles on July 28 for Mike Bordick, one of those guys talked up as a “surehanded” or “two-out” shortstop. Hit a grounder to Bordick with two outs, he was sure to pick it up and throw it cleanly to first. Mora did so much well, yet he didn’t necessarily inspire that kind of confidence at that precise position, and a sense of security is what the Mets craved at this stage of 2000.

“Melvin Mora has a chance to be a star,” Bob Costas had said, but it was no longer the Mets who thought so.

***Did this trade have to be made? Did any trade have to be made? The Mets were determined to make one. They thought they had one done for Barry Larkin, but veteran Larkin had the right to decline to leave the Reds, and he exercised his veto. Mora wasn’t rumored to be a part of that swap. Had Barry embraced New York, Melvin could have returned to his supersub ways, perhaps been available in October when Bell went down with an injury in right, and given the Mets the same spark they benefited from in 1999. Instead, they turned to Timo Perez as their emergency right fielder. Perez was all spark until his flame burned out on a trip from first to not quite home in the World Series. It’s impossible to imagine Melvin Mora not running hard on a fly ball.

Did the Mets need surehanded shortstop Bordick to reach October again? It couldn’t have been known on July 28, but after the Mets took leadership of the Wild Card standings on July 27 — Mora’s last day as a Met — they’d never let it go. They’d have their September hiccups (they always did), but they were never headed on their path to the playoffs despite their disturbing habit of losing too many games with not too many weeks to go. The 2000 Mets were particularly sizzling in August, and Bordick was a part of that. He might have been part of a World Series win had he not gotten hit in the hand by a pitch during the NLCS. As it was, Bordick ached and, by Game Five, Abbott was the Mets’ starting shortstop with everything on the line and, well, you know.

Do trades have to take place? Philosophically, the exchange of human beings strikes a sour note. Purely from a baseball perspective, there is something that seems a little untoward about trades. Why not stick with who you have? Why not depend on your Mets to get better together? It, like the 1999 Mets, is a romantic notion. The 1999 Mets wouldn’t have been the 1999 Mets without a trade for Piazza. Or Leiter. Or several other beloved members. So maybe let’s not question trades too deeply.

Melvin Mora was a beloved 1999 Met, despite rattling around the All Other section of the roster for 161 games. The last dozen, though — the Melvin Mora Game; the One-Game Playoff; the NLDS which we won in four; the NLCS which we gave all of ourselves for for six — he was a star attraction. We couldn’t take our eyes off him. We didn’t want to.

In 2000, we moved on without him. That’ll happen in baseball. The Mora-less Mets went to the World Series. It proved risky business. They could’ve used a guy like Melvin. Same for the rest of the first decade of the 21st century, a time when Melvin Mora cashed in on the opportunity to become a star. It was as an Oriole, not as a Met. It was as a third baseman, not as a shortstop. He won a Silver Slugger in Baltimore and made two All-Star teams. True, the Mets were promoting David Wright in the first half of the first decade of the 2000s, but they probably could have found something for Melvin Mora to do at another position. Or gotten more for Mora than two-and-a-half months of Mike Bordick.

Then again, Bordick did help the Mets win a Wild Card and two postseason series. It’s easy to slag trades that don’t work in the long-term, but in the short-term, the Mets made the World Series with Mike Bordick. It’s a reality the Mets chose to pursue.

The fantasy that they’d hung onto Melvin Mora and that Melvin Mora would have kept doing Melvin Mora things — 1999 things — remains tantalizing in hindsight. In hindsight, Melvin Mora makes a wonderful Met in any century.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

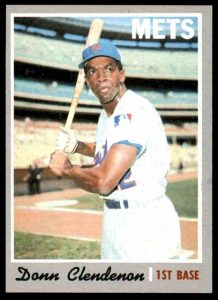

1969: Donn Clendenon

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

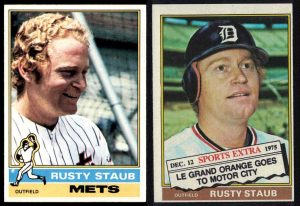

1982: Rusty Staub

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

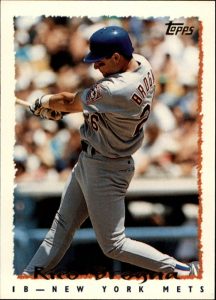

1994: Rico Brogna

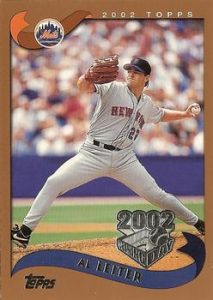

2002: Al Leiter

by Greg Prince on 15 May 2020 1:36 am Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

Under a big ol’ sky

Out in a field of green

There’s gotta be something

Left for us to believe

—Tom Petty, “Kings Highway”

It’s Opening Day 2002 at sunny Shea Stadium. The Mets have been reconfigured to dominate after they deteriorated in 2001. It won’t work out that way, but we don’t know that yet. Besides, it doesn’t much matter that the cast has been so thoroughly shuffled from the year before. On Opening Day, your team is YOUR team. Just let somebody try to steal your sunshine.

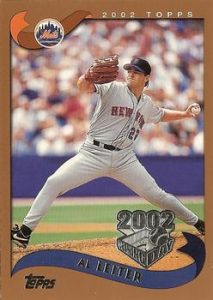

On sunny Opening Day 2002, Al Leiter is OUR starting pitcher. On many days between the beginning of 1998 and the end of 2004, Al Leiter was our starting pitcher. The only thing Al Leiter ever did as a Met (other than triple) was starting-pitch: 213 games, 213 starts. That’s more starts as a Met pitcher without a single pitch thrown in relief than anybody else. Jacob deGrom is second by more than a conceivable season’s worth of starts — a real season, not whatever 2020 is shaping up as on corporate drawing boards.

We didn’t coordinate with one another, but Al Leiter is also the career leader in starting games I’ve attended, and I’ve been attending games since 1973. Al and I were by no means a bad pairing, no matter how intuitively unlikely it seems in retrospect that we’d get together as frequently as we did. We all believe that when we buy a ticket to a ballgame, the fine print subjects us to a steady uninspiring stream of Trachsels and Nieses. I’ve had my share of those, too. Plenty of Kevin Appier the one year he was here. A load of Bobby Jones, a dash of Randy Jones, a pinch of Pete Smith for mediocre measure. I’m not convinced I won’t see Mike Pelfrey slog through six innings the next game I go to, and he hasn’t been on the Mets since 2012. Go to enough games, you’ll see just about everybody take a start or ten. Go to more than enough games, though, specifically between 1998 and 2004, and you’ll get your Leiter on repeatedly.

It was the right time and the right place. The lefty’s face was charming. It was the right face. There was little hint of phenomenon to it, no boasting within your social circles that you hit the Al Leiter game last week, no future posting for posterity on Facebook that you were a part of Leitermania, here’s a picture of my ticket stub! But if Al Leiter was a notch below the perceived glamour of acedom, he hovered discernible cuts above the middle of the pack. Sometimes an ace is an inherently imposing mound presence. Sometimes he’s just the best guy you’ve got handy. When somebody whose credentials glittered a little more brightly than his was acquired in some ambitious offseason, Al Leiter would be courteously consigned to 1A status — still conferred the organizational respect he’d earned, yet no longer automatically tabbed as the first choice to start a season or a series, assuming there was ample opportunity to line your pitching up according to preference.

When nobody better was around, or you simply had to win the next game in front of you, you could do a lot worse than Al Leiter. In contemplating the Metsian legacy of the lefty who was never exactly “my guy” despite my seeing him so regularly, I’m reminded of a tribute to Tom Petty that I read in the wake of the singer’s death in 2017. It referred to Petty’s music as good for the middle of a weekday afternoon, or something to that effect. I don’t recall the exact phrase or precisely what the author meant, but I liked the description and I think I got it. I was by no means the biggest Tom Petty fan, but I admired how he used his repertoire, how he threw himself into his game, and how he left me feeling better for having experienced him doing what he did anytime I’d hear him do it.

Thirty-seven regular-season games at Shea Stadium Al Leiter was my starting pitcher, plus twice in the playoffs and, to be rotationally retentive about it, once as an opponent. I don’t ever remember thinking in advance, “Leiter? Not again.” Nor, probably, did I think, “Oh boy, Leiter!” It was more like, “Al Leiter…all right, let’s go…” The games could get edgy when Bobby Valentine was managing, but a bit of the edge was taken off knowing Al Leiter was starting. His near-constant presence was comforting. That was where my head was at on Opening Day 2002, just as it was more than two-dozen times before. Standing and applauding in the right field boxes, it was exciting to welcome Alomar and Vaughn, welcome back Burnitz and Cedeño, value as ever Piazza and Alfonzo. But when we got to “pitching and batting ninth, warming up in the bullpen…”

Al Leiter. All right. Let’s go.

In transactional terms, Al Leiter became a Met because the Florida Marlins were dumping their champion players left and right following their 1997 world conquest. But really, Al Leiter became a Met because Al Leiter was always supposed to be a Met. Before Todd Frazier invented being from New Jersey, Al Leiter was from New Jersey — the same town as Todd — and he grew up a Mets fan, old enough to tell us that as a lad he witnessed the Mets’ 1969 flag run up the center field pole on Opening Day 1970. Depending on the interview he was giving, he also seemed to grow up not immune to the charms of other teams within driving distance of Toms River, but fealty to the Metropolitan cause fit his story and personality most snugly.

Two starts into his Met tenure, he looked the part of prominent Met pitcher. Not that he was as graceful as Seaver or as overpowering as Gooden, but he was as preoccupied with the Mets winning as any of us. Leiter probably wanted to win for Leiter, as starting pitchers are prone to do, but you couldn’t wipe the familiar concern off his face. He grimaced. He grunted. He gritted. He looked like us. His look certainly got the attention of my wife, who had the game on before I came home on April 7, 1998. The Mets were at Wrigley that afternoon and Stephanie, usually a passive consumer of baseball telecasts, wanted to know what the deal was with this guy with the face.

That face was the deal. He was the cat of a thousand expressions. That’s what we call our kitty Avery. The concept originated with our watching eternally expressive Al Leiter. He was always doing something that fascinated us, not the least of which was pitching effectively. Leiter steadily put the “1” in “1A” as 1998 got rolling, emerging as first among a staff of approximate equals, missing the All-Star team only because of an ill-timed knee injury in late June. While the Mets mostly melted down around him, Leiter stayed strong in September. Al finished his first Flushing year 17-6 with an ERA of 2.47 and garnered token Cy Young support, the first Met to be so acknowledged in four years. You couldn’t run it up the center field pole, but it was surely worth saluting.

Once Leiter opened a World Series and tried desperately to keep the same World Series going. Leiter never again had quite as brilliant a campaign for the Mets as he did in his initial one, but he never had a genuinely bad season over his remaining six. Three times he opened the season. Once he opened a World Series — and tried desperately to keep the same World Series going. Al Leiter being entrusted with the ninth inning and all its inherent implications in Game Five of 2000 and not getting all the way out of it versus I forget who never hung around his or Bobby Valentine’s neck quite the way a close facsimile from 2015 sticks to the respective shoes of Matt Harvey and Terry Collins. Al is remembered better for coming through than coming apart. He stopped a potentially lethal losing streak down the stretch in ’99; clinched a playoff spot via masterful two-hitter less than a week later; and held the Mets aloft for much of what was to become known as the Todd Pratt game less than a week after that.

Leiter’s one truly godawful postseason outing, when, on short rest, he didn’t retire a single Brave in the first inning of ultimately decisive Game Six of the 1999 NLCS, is relatively obscure in the scheme of Al’s career. In the annals of abysmal first innings proffered by titular Met southpaw aces at the worst imaginable juncture, it doesn’t hold a candle in the realm of public perception to T#m Gl@v!ne’s least finest hour, which took place somewhere between 1:10 and 1:30, September 30, 2007. For that matter, Leiter’s horrifying first inning from the night of October 19, 1999, at Turner Field (0 IP, 2 H, 1 BB, 2 HBP, 5 ER) is obscured in common memory by the work of another veteran lefty, Kenny Rogers, ten innings later.

Maybe it was because locally sourced Leiter put his heart into every start he took as a Met. And his face, which you couldn’t miss. Plus he was always good for a detailed explanation of why he may not have won on a given evening and what he (along with his teammates) could have done more ably. Al’s starts could feel like struggles even when he was shutting down opponents, which is why his victories registered as triumphs of the Mets fan soul. He seemed properly bothered by everything that went wrong when anything went wrong.

Fortunately, plenty went right for seven seasons, so even with the occasional rough patches on the mound, Al Leiter remained OUR starter in generally good standing pretty much to the end of his time as a Met. His last start for us — and for me — came at Shea on October 2, 2004, a Saturday night against the Expos, the last game that franchise won under its original name. Omar Minaya, Montreal’s former GM, had just been hired to do the same job for the Mets. It was obvious Minaya’s Mets were going to have to put the current futile era behind them ASAP.

That meant the imminent end of Al Leiter, pending free agent, who had two Met eras under his belt (three counting his childhood allegiance to Seaver and Koosman). Before Opening Day 2002, Al was right in the middle of every big series the Mets had contested for four mostly successful, uniformly scintillating years. Those Mets of 1998-2001 were kind of a 1A operation themselves. When somebody better-credentialed was on hand, the Mets took a back seat. When nobody better was around, you could do worse.

The Mets did worse in 2002, 2003 and 2004, lacking for big series altogether after dismal reality set in, but on Opening Day 2002, we didn’t know that further deterioration rather than a surge toward dominance was in store. We just knew Al Leiter would be starting. We just knew, as of April 1, 2002, that Al Leiter was always starting…OK, often starting. But he was on the mound a lot, giving us his all, and it most always gave us a reason to be reasonably confident that we might win this game. Like on Opening Day 2002, a 6-2 middle-of-a-weekday afternoon Mets win in which Leiter pitched six innings and gave up no runs. Like so many other days. Leiter won 95 games as a Met, sixth-most in club history. That implosion in Atlanta notwithstanding, he was usually money in the postseason for us, even if he never pulled down a W. It was telling that we were in the postseason enough during Leiter’s first era that he could mount an October sample size worthy of measurement. He made seven starts, six of them undeniably quality.

In 2005, the next Met era, Al Leiter was essentially replaced by Pedro Martinez. That was an ace you didn’t need to append an “A” to. He was an undisputed No. 1 pitcher, starting games that were destined to be billed as bona fide events all summer long. Time to move on. Time to get going. The first time Pedro started at Shea as a Met, on April 16 versus the Marlins, the joint jumped with anticipation. His mound opponent was his predecessor, now a Recidivist Fish, marking the fortieth and final time I saw him pitch in person. Martinez vs. Leiter. Giddily promising present vs. suddenly distant past. Pedro cheered wildly by a sellout crowd. Leiter booed obligatorily for what he wasn’t: for not being Pedro; for not being ours.

Al’s expression told me he got it.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1969: Donn Clendenon

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1982: Rusty Staub

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1994: Rico Brogna

by Jason Fry on 12 May 2020 8:42 pm Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

Some political raconteur (no one agrees exactly who) tattooed George H.W. Bush with the line that he reminded every woman of her first husband. It’s a good line — a put-down, but one delivered with an undertone of affection, however grudging. And it stuck with me as I thought about how to sum up Todd Hundley, our Met for All Seasons representative of the less-than-lamented 1992 Mets.

Hundley first arrived in the spring of 1990, seemingly destined to be a curious footnote in team history. He was not yet 21, a catcher who could be charitably described as slight and less charitably called undersized — his first Topps card records his weight as all of 170 pounds. His pedigree also made historically minded Mets fans scratch their heads: Todd was the son of Randy Hundley, a key player for the 1969 Cubs. Maybe you recall or read about Hundley Sr. jumping in the air during the Bill Hands–Jerry Koosman duel on Sept. 8 at Shea, protesting Satch Davidson having called Tommie Agee safe at home. (Indeed, Agee sure looks out to me — sorry, Randy.)

In his first campaigns with the Mets, Hundley fils did little to dispel that first impression. He hit .209 in limited time in 1990, then .133 the next year, with the kind of power you’d expect from a reedy shortstop. But his defense was considered big-league quality, and the Mets were certain the bat would come around. A decent campaign at the plate for Tidewater in 1991 made Hundley a regular in 1992, even amid doubts that he was ready. It didn’t go particularly well — nothing went well for the Mets that star-crossed season — but he earned respect from teammates and the beat writers as both tough and likable. Despite his modest success, he was a stand-up player in a clubhouse with far too many pointed fingers.

Possibly the most embarrassing baseball card of the modern era. Who at Topps hated Hundley and why? From there, he turned into a useful player, hitting 42 homers over the next three seasons. And then, in 1996, Todd Hundley hit 41 home runs. Drove in 112. Those 41 dingers set a Met single-season mark, eclipsing the 39 hit twice by Darryl Strawberry, and set a new N.L. record for homers by a catcher, beating the record that belonged to Roy Campanella. What had changed?

For once thing, Hundley had, well, grown. The little bantamweight catcher from 1990 looked like an action figure, with huge shoulders and biceps and forearms. Eleven years later, the Mitchell report portrayed Kirk Radomski, once a Mets clubhouse attendant, as a Johnny Appleseed for the steroid era. Radomski, the report said, had told Hundley before the 1996 season that steroids would let him hit 40 home runs, then sold Hundley Deca-Durabolin. The report named Hundley and teammate David Segui as important links in Radomski’s steroid chain, with Hundley connecting Paul Lo Duca with Radomski after Hundley moved on to the Dodgers. Lo Duca, in turn, would tell more friends. It was like that old shampoo ad, albeit with very different stuff in the bottles.

Hundley was retired by the time the Mitchell report came out in 2007, but finding his name in there was about as surprising as waking up in the morning to discover the sun had risen again. Todd Hundley’s power surge might not have been entirely natural? Hell, I was surprised he hadn’t glowed in the dark during night games.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Back in the mid-1990s, steroids was still a fringe concern among the media and fans. Yes, astute Met fans remembered the anecdote about Lenny Dykstra showing up way back in 1987 looking like an inflated steer and blithely telling a shocked Wally Backman that he’d been taking “those good vitamins.” But we were years away from questions about the bottle in Mark McGwire‘s locker, from the furor around McGwire and Sosa and Bonds and Clemens, from a shrunken McGwire telling Congress he wasn’t there to talk about the past, from suspicions and suspensions and testing, and from the first of about a billion Hall of Fame debates that convinced absolutely no one of anything.

And you know what? I loved Todd Hundley.

I loved that he hit home runs, of course. But I also loved that he had swagger and that he actually said interesting things to the newspapers. Despite the media glare of New York and his pedigree as a big-leaguer’s kid, he gave answers that weren’t carefully sanded down to meaninglessness, and you always had the sense that he was in on the cosmic joke of it all. His scraps with Bobby Valentine were particularly eventful, variously exhausting and entertaining. Valentine was a Billy Martin for a more psychological, media-saturated age — a genius whose greatness was fueled by paranoia about not only enemy managers but also his own clubhouse and organization. That paranoia extended to his catcher, the team’s most popular player, who didn’t fear the spotlight that his manager also craved. At least they had that in common; otherwise they were polar opposites. Hundley struck the fanbase as almost comically straightforward, while we all knew Valentine was maniacally at work behind the curtain at all times, leaking and jabbing and spinning clubhouse webs.

Hundley’s 41st home run came on Sept. 14, 1996, a day game at Shea. It was a three-run shot off future Met Greg McMichael, turning a 5-2 lead into a tie. Hundley took a curtain call and the Mets beat the Braves on a walkoff in the 12th. I recall that I was there, though perhaps that’s wishful thinking — I don’t have a ticket stub from the game, which I probably would have held onto. But let’s say I was. Whatever my location, I recall cheering madly for Hundley as he stomped around the bases, and hoping that blow had made Bobby Cox — who always wore the expression of a man who’d just sat in a puddle — even grumpier than usual. At the same time, that cheering felt like spitting in the eye of a bully who’d finally taken a breather because he was tired of pummeling you. The Braves were comfortably in first place and operated like a sleek machine; the Mets were 14 games under .500.

But better times were ahead. In ’97 the Mets won 88 games and Hundley hit a more modest but still glamorous 30 homers. He might well have hit more, except his right elbow had betrayed him. He’d wind up needing Tommy John surgery, which claimed the first three months of his 1998 campaign — and helped pave the way for the Mets’ acquisition of Mike Piazza.

Somehow that acquisition was 22 years ago, meaning I could easily revise how I reacted at the time. But I won’t. I hated the trade. Piazza was a catcher, I fumed, and we already had a perfectly good catcher.

Except a) we didn’t, as Hundley was still rehabbing; and b) even a fully armed and operational Todd Hundley was not Mike Piazza.

The Mets, to their credit, didn’t think the way I did. (Less to their credit, they assured Hundley no such deal was in the works.) They grabbed one of the game’s marquee players and reasoned that the problem of too many catchers would work itself out. Which it did — as an oh-so-Metsian tragicomedy.

Hundley returned in July, but as a left fielder. He even mostly said the right things about this hasty recasting, vowing that if it worked out he’d burn his catcher’s gear.

It didn’t work out. Oh man did it not work out. If you weren’t there, it was a disaster wrapped in a farce. Daniel Murphy staggering around in left in Miami? He was great compared with Hundley. J.D. Davis and Dom Smith? Gold glovers and UZR gods next to Hundley.

It was brutal and unfair and thoroughly unsuccessful. But Hundley somehow rose above it, or at least didn’t let it drown him. He took responsibility for the misplays, he waved at the fans when they gave him a standing ovation for a routine catch, and he shook off the usual anonymous Met sources who pilloried him for everything from his nocturnal habits to how he’d handled rehabbing the elbow. He even took an odd stab at perspective, noting he’d flipped away from highlights of one of his misplays and wound up watching an Anne Frank documentary. His conclusion was that “the bad night I had doesn’t even come close.” Somehow the idea of a supersized Hundley squinting at grainy pictures of Bergen-Belsen and deriving life lessons from it strikes me as iconically late-90s.

Hundley got better in left field, which isn’t to say that he got good at it, just that he stopped butchering every routine fly ball. But his surgically repaired elbow wasn’t up to throwing, leading to a carousel of runners. He also wasn’t hitting, accumulating strikeouts by the bushel. The Mets mercifully ended the left-field experiment in late August; Hundley said he was burning his outfielder’s glove. When he returned from a DL stint, it was as a backup catcher and pinch hitter.

Which led to the one great moment of the surreal, misbegotten Hundley/Piazza era. On Sept. 16, with the Mets battling for a wild card, they trailed the Astros 2-0 in the top of the 9th. With two out and two on, Piazza connected off Billy Wagner for a three-run shot, the 200th of his career. The Astros retied the game in the bottom of the 9th, but Hundley won it with a pinch-hit homer in the 11th.

I tried to convince myself that this was the start of something grand, when everything suggested otherwise. After the game, Hundley and Piazza stood side by side, but their body language clearly communicated that both really wanted to be somewhere else. Which was only natural, given that they were sharing a position to which each had good reason to feel entitled. As for the something grand, the Mets went 2-6 the rest of the way, with the Braves administering the coup de grace with a final-weekend sweep. That winter, the Mets signed Piazza to a seven-year deal and traded Hundley to the Dodgers. Hundley’s time in L.A. was reasonably productive, but a homecoming to Chicago and the Cubs was a disaster, one made more painful by how beloved his dad had been wearing the same uniform. Hundley feuded with his manager, flipped off fans, and worst of all he didn’t hit. The Cubs sent him back to L.A. and he retired at 34.

Hindsight is like looking through the wrong end of a telescope, which gets us back to that first-husband crack. Looking through our wrong-way telescope, Hundley was the catcher subtracted to make room for Piazza. He was a lone bright spot in a dim and dismal period followed by a Piazza-led Mets resurgence. Which isn’t incorrect, exactly. But it is incomplete. It ignores the pretty good ’97 campaign and the agonizing near-miss of ’98, for one thing. And it’s colored by what we now know about that era of the game.

Yes, Hundley was transformed into a ridiculously brawny action figure and hit 41 home runs. And yes, we have a pretty good guess about how that happened. But he was surrounded by ridiculously brawny action-figure ballplayers. You could go from 1995 to 2005 (to pick a possibly arbitrary range) and I don’t think there’s a baseball player I’d be shocked to learn used PEDs. Disappointed? Sure, at least in one case. But shocked? Uh-uh. If you’re still capable of being shocked by such a revelation, you weren’t paying attention.

It was a mildly ridiculous era, both for baseball in general and for New York in particular. But I loved Hundley anyway — for the now-suspect feats of strength, but also for surviving innumerable swims with sharks and emerging with both his sense of humor and his sense of self intact. And there’s no asterisk on the latter.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1969: Donn Clendenon

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1982: Rusty Staub

1991: Rich Sauveur

1994: Rico Brogna

by Jason Fry on 8 May 2020 2:48 pm I was five months old when the Mets completed their ascent from doormats to destiny’s darlings, and by the time I started collecting cards in 1976, the miracle makers had been largely dispersed. Just six were still Mets. The rest had become Pirates and Astros and Phillies and other questionable things, or started doing whatever people did when they no longer played baseball. Two were no longer with us at all.

In an era before videotapes, let alone YouTube, I learned the saga of ’69 through books, snapping up every quickie paperback I could find about the Miracle Mets. Which turned out to be a terrific education, as a lot of those books were genuinely great reads, thanks to a deep bench of talented New York sportswriters. George Vecsey’s Joy in Mudville, Paul Zimmerman and Dick Schaap’s The Year the Mets Lost Last Place and Maury Allen’s The Incredible Mets were particular favorites, with a special place in my heart reserved for Screwball, written by Tug McGraw with X amount of help from Joe Durso. And there was the peerless Roger Angell, whose meditations on baseball convinced me that other teams were sometimes worth pondering too. But I wasn’t discriminating — I’d read anything about the Mets, or that might be about the Mets.

That was how I learned the gospel. About Tom Seaver refusing to celebrate .500, and Gil Hodges taking the long walk out to speak with Cleon Jones. About the black cat and Leo Durocher and Ron Santo clicking his heels. About Frank Robinson calling Rod Gaspar “Ron Stupid” and the Met wives unfurling a banner in the stands in Baltimore. About the scoreboard saying LOOK WHO’S NUMBER 1 and the shoe-polish ball being brought to Lou DiMuro. I read about Tommie Agee and Ron Swoboda catching balls dozens of times before I ever got to see them do it, and could tell you in great detail how J.C. Martin should have been out but I was glad he wasn’t, despite no visual reference. I’d studied the picture of Jerry Koosman jackknifed in Jerry Grote‘s arms while Ed Charles danced happily nearby so many times that I could draw it from memory.

There was stuff I didn’t understand yet, like the controversy around Seaver and the Vietnam war and a flag that absolutely should or shouldn’t have been at half-mast, or why anyone thought it was significant that the Mets’ black and white players all seemed to get along. And there were random pieces of the adult world that those books lodged in my brain because of their Mets connection. I was foggy on who John Lindsay, Nelson Rockefeller, Jackie Onassis, Ed Sullivan or Pearl Bailey were, but I knew they were part of the tale and that was good enough for me. (I still don’t really know who Pearl Bailey was.) I knew it was funny that Swoboda had yelled, “they’ve sprayed all the imported and now we have to drink the domestic,” and repeated that endlessly despite not knowing why it was funny. Oh, and for some reason I could tell you that Nancy Seaver wore a tam o’shanter. (There it was atop her head in last night’s SNY airing of Game 4, just like the books taught me.)

But there were discordant notes in the saga, things that seemed strange to me but not to adults. Some of the Miracle Mets had retired because they were old, at least for baseball, but others had disappeared before their time — what had become of Gaspar, or Jack DiLauro? As I kept reading and learning, I figured out that Gaspar and DiLauro had been the last guys on the roster, the kind of guys who had to keep fighting for big-league jobs. But that still left one mystery: What had happened to Gary Gentry?

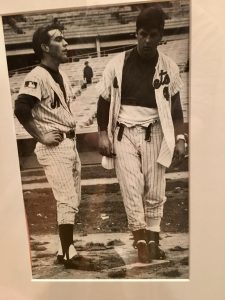

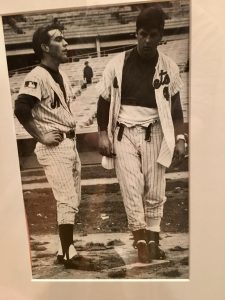

From Jace’s front hall to this post. He’d been a rookie in 1969, and even I knew he was young for a ballplayer then. Heck, he even looked young to me, for whom everybody was old. One of my favorite Mets photos is of Gentry and Seaver standing on the mound after the Mets clinched the division and security guards wrested the field back from the sod-pillaging mob. Their uniforms are in disarray, as is the field. The photographer caught Gentry while trying to get his bearings in this strange new world, but the first thing you notice is he looks about 12.

I knew Gentry had been a good pitcher — a really good one, in fact, part of the Mets’ front line with Seaver and Koosman. But Seaver and Koosman were still Mets, and Gentry wasn’t. He’d become an Atlanta Brave, grown a mustache that made him look vaguely dissolute, and then vanished. The explanation given by Mets books and the occasional Baseball Digest mention was that he’d hurt his arm, which was both annoyingly vague and raised more questions than it answered. Was hurting your arm really that common? Could it happen to any pitcher?

The answers turned out to be yes, and yes.

I’d learn that eventually — a brutal baseball truth that in my mind will always be bound up with Gary Gentry.

As I got older, I realized that not all of the Mets had actually been baseball gods, and the ’69 championship had been less about destiny than superlative pitching, smart platooning and some good old-fashioned luck. (OK, so maybe there was a little destiny involved.) But Gentry really had been that good. He was a position player in high school, attending the wonderfully named Camelback High in Phoenix, before taking the mound for Phoenix Junior College and Arizona State. As a junior at Arizona State, Gentry went 17-1, fanning 229 in 174 innings; in the College World Series semifinal he went 14 innings against Stanford, striking out 15 and scoring the winning run. He was drafted by the Orioles, Astros and Giants, but his dad — a former World War II and Korean War pilot — refused to let him sign. The offers kept getting better, and after the College World Series Ed Gentry left the decision up to his son. Gary signed with the Mets for $50,000, blitzed through Williamsport and Jacksonville, and made the Mets out of spring training in 1969, when he was all of 22.

Gentry was two years younger than Seaver, but there were a lot of similarities between them. Gentry was smart, a student of the game eager to learn how to carve up enemy hitters. (The Mets put his locker between Seaver’s and Koosman’s, an excellent place to learn this craft.) He was ornery, though sometimes he directed his fire at teammates or management instead of the opposition. And, like Seaver, he had no patience for the dysfunctional romance around the Mets as lovable losers. Gentry’s juco team had won a national championship and just missed another one, he’d won a College World Series with the Sun Devils, and both his minor-league teams had been league champions. He wasn’t overawed by being a big leaguer, and he expected to win.

And he did. Gentry won 13 games as a rookie in ’69 and could have won 20 with better run support and less bum luck. (And, perhaps, with more ability to shake off misfortune — but, again, he was 22.) He won the division clincher, then started the NLCS capper against Atlanta (Shea Stadium’s first postseason game) and Game 3 of the Series, best known for Agee’s two sparkling catches. His performance against Baltimore came as a surprise to both Earl Weaver and Frank Cashen, who knew about Seaver and Koosman but whose scouting reports had badly underestimated Gentry. Years later, Cashen would still grow visibly irritated about the rookie who’d beaten his Birds — and Gentry, when asked, would still be irritated about Cashen being surprised.

(Oh, and he’s one of the most enthusiastic Mets belting out “You Gotta Have Heart” on the Ed Sullivan Show — behind McGraw, of course, and maybe Gaspar. Though nothing in that video will ever be funnier than Nolan Ryan, who can’t be bothered and doesn’t care that it’s obvious.)

After 1969 things went sideways for Gentry — sideways and then south. In ’71 Gentry groused about getting second-class treatment in the rotation and struggled with his emotions on the mound, repeatedly showing up teammates who didn’t make plays. He was still a prized commodity, though — the Angels settled for Ryan as the price for Jim Fregosi after being refused Gentry. In ’72 arm problems that had plagued him since 1970 became worse, and after the season the Mets traded him and Danny Frisella to the Braves for Felix Millan and George Stone.

As it turned out, Gentry had been pitching with a bone chip in his elbow, which the Braves’ doctors found after arm woes derailed his 1973 season. The operation to fix the chip would have been simple in 1970, but now it put him on the shelf for the rest of the year. He came back in ’74, but the highlight of his campaign was standing in the bullpen hoping to catch Hank Aaron‘s 715th homer. (Tom House caught it instead.) After another operation and lost year, Gentry returned for a third try in ’75, but feuded with Atlanta about a pay cut and wound up exiled to the bullpen. After getting shelled in a mop-up assignment despite being given minimal time to warm up, the Braves told Gentry he was being released to make room for younger pitchers. He was 28 and his arm felt fine, but he was done.

Done except for a tantalizing what-if. The Mets’ pitching staff was in tatters and they signed Gentry a month after Atlanta sent him home. He reported to Double-A Jackson with a promise that he’d be called up as soon as he showed the club all was well. Unfortunately, Gentry hadn’t picked up a ball in a month. He was in a hurry when he should have taken it slow. He warmed up for his first game, threw two pitches and heard something rip. Another pitch, another rip. He never so much as recorded an out for Jackson and went home to Phoenix to learn the real-estate business.

Remember when Jason Isringhausen and Bill Pulsipher were about to lead the Mets back to the top of the mountain, with Paul Wilson waiting in the wings? The debate was who was Seaver and who was Koosman and should we maybe be talking about Jon Matlack. But there was another possibility, a disquieting one that nobody wanted to mention. What if they all turn out to be Gary Gentry?

That wasn’t a knock on Gentry, but a knock on wood against the cruelties of baseball — a knock on wood that didn’t work. Only Isringhausen survived to have a notable career, and his top similarity score over on Baseball Reference isn’t Tom Seaver but Bob Wickman. As for Pulsipher and Wilson, they did indeed turn out to be Gary Gentry. Which might also be the fate of Noah Syndergaard. Or David Peterson. Or the next Met phenom you haven’t heard of yet.

What went wrong? You could blame Mets coaches, or Mets doctors, or their counterparts with the Braves, or any of a host of targets. But when it comes to injured pitchers, decades of advances in baseball science and sports surgery have brought us all the way from groping in the dark to groping in the dim. You wait for the pop, the shake of the arm, the visit from the trainer, the uncertainty and rehab and further uncertainty that follows, and it all still boils down to a simple, cosmically unfair truth about the game. Learning that truth was the solution to the mystery of Gary Gentry’s disappearance, a cruel lesson that generation after generation of Met pitchers has reinforced and will reinforce.

He hurt his arm. Pitchers break.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1969: Donn Clendenon

1973: Willie Mays

1982: Rusty Staub

1991: Rich Sauveur

1994: Rico Brogna

by Greg Prince on 5 May 2020 3:24 pm Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

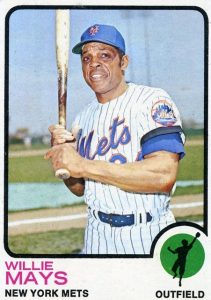

When Willie Mays returned to New York, many saw it — may God forgive them — as a trade to be debated on the merits of statistics. Could the forty-one-year-old center fielder with ascending temperament and waning batting average help the Mets? To those of us who spent our boyhood, our teens, and our beer-swilling days debating who was the first person of the Holy Trinity — Mantle, Snider, or Mays? — it was a lover’s reprieve from limbo. No matter how Amazin’ the Mets were, a part of our hearts was in San Francisco.

—Joe Flaherty, “Love Song to Willie Mays,” 1972

Maybe it was when I opened to the baseball chapter of the New York Times-branded book of sports records I was given for a seventh birthday present, examined the all-time home run list, and realized the player listed as second was still playing. Maybe it was the cumulative effect of hearing repeated endorsements by announcers — ours as well as the ones who spoke glowingly of him on national telecasts. I could’ve picked it up in the papers during my early, precocious infatuation with sports sections. However the notion embedded itself within my head and heart, by the time the first All-Star Game I tuned into rolled around on July 14, 1970, there was no doubt in my mind.

Willie Mays was the best player in baseball. Maybe not the best at the moment (Johnny Bench seemed to have that title well in hand). Maybe not the best ever (Babe Ruth did have the most home runs). But, nearly twenty years before Tina Turner would make bank off the phrase, and three years before his emotional 1973 retirement choked up the portion of the nation whose pastime would always be baseball, Willie Mays reigned as simply the best. It’s no surprise that leading off in that All-Star Game for the best of leagues, the National, was simply the best player there was.

Of course Willie Mays came first.

Thanks to NBC, I was exposed to a passel of future Hall of Famers that Tuesday night. Twenty players introduced at brand new Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati fifty summers ago now have plaques in Cooperstown. I lapped up all those gallons of greatness swirling through the portable Sony black & white set stationed in my sister’s room that she rarely watched. At seven years old, my July nights were already about baseball. My days, too. The names — Aaron, Clemente, two Robinsons, Seaver obviously, Bench and Perez from the home team, Carew, McCovey, Palmer and on and on — were already familiar to me. I’d seen them everywhere I’d looked. Baseball cards. Baseball lists. Baseball stories. Now they were all together in one baseball place.

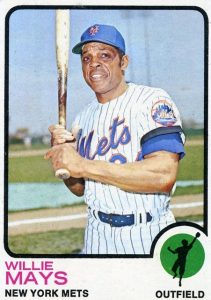

But first and foremost among them was Willie Mays, center fielder for the San Francisco Giants with now more than 600 home runs and the irresistible nickname the Say Hey Kid. He was the best, and as the best, I really wanted his card. Couldn’t get one in 1970, not even in that “Super Series” where the cards were absurdly oversized and incredibly thick. Couldn’t get one in 1971, either. Come 1972, however, my interminable dry spell came to an end (interminable being a relative matter when you’re nine and you’ve been wanting something since you were seven). The very first pack of spring in third grade, purchased at the Cozy Nook on the walk home from East School, revealed his name in a serif font above his smiling face which was framed under a yellow banner from which his team name fairly exploded: GIANTS. I couldn’t believe I had Willie Mays in my hand. I sat in the kitchen, cradled it, marveled at my fortune, and smiled at his smile.

Make me smile. Then I flipped him over. Even at nine…even at seven, I was always more taken by words, numbers and facts than I was images.

Will ya look at that set of statistics? They start in 1950 in the minors (those don’t really count). A year later, he’s in the majors, where he’s stayed ever since. There’s one year that’s blank when he’s “In Military Service,” but otherwise Willie Mays is always playing and always posting titanic totals. As many as 52 homers in one year. As many as 127 RBIs. Batting averages regularly over .300. Those are the main numbers if you’re a baseball fan of any vintage, though the Topps people are kind enough to list ancillary stats like runs and hits and doubles and triples and believe you me (whatever that means; it’s something people said on TV), Willie Mays has a ton of those, too. The yearly accumulations grew a little lighter as the 1960s were ending and the 1970s were beginning, but that, I infer in the spring of 1972, is to be expected. Willie Mays’s birthdate is listed as 5-6-31, which makes him 40 going on 41. He’s almost as old as my father. Eighteen home runs, sixty-one runs batted in and a .271 average — his totals from 1971 — are pretty good for someone over forty. In 1971, Willie Mays helped lead the Giants to a division title. In 1971, Willie Mays had more home runs and more RBIs than anybody on the Mets.

Funny thing about the back of the 1972 Willie Mays card, No. 49 in the first series from Topps (No. 50 was Willie Mays In Action). Where they list “TEAM” and “LEA” for his first bunch of years in the big leagues, Mays isn’t with San Francisco, which is where I know him from. Instead, from 1951 through 1957, including his military service year of 1953, the card says he played for “New York N.L.” I do a double-take. At the age of nine, I know better than to think there was some sort of secret Willie Mays past nobody’s mentioned regarding a long-ago tenure with the only “New York N.L.” I’ve ever experienced. I know my New York Mets of the National League have, like me, been around only since 1962.

I also know, albeit vaguely, that the San Francisco Giants used to be the New York Giants, the way the Los Angeles Dodgers used to be the Brooklyn Dodgers. It doesn’t come up very often in conversation, but it’s one of those myriad ancient, as in before I was born, baseball lessons I’ve absorbed since entering the game’s thrall as a lad of six. I’m nine now. I’ve been around. I pay attention on Old-Timers Day, I’ll have you know. I even remember getting Hoyt Wilhelm’s card in 1970 (it said he was on the Braves but his cap was disturbingly blank), and on the back he got the “New York N.L.” treatment. It was hard to fathom that anybody who played in the 1950s was still playing baseball in the 1970s, but at least a few of those guys were. A couple played for “New York N.L.” before it meant what I know it means now.

Yet here in the spring of 1972, when one has achieved what may have been his first longstanding lifetime goal, a person can dream. I’m looking at this Willie Mays card I finally have. I’m looking at these credentials of his. I’m looking at “New York N.L.” and how it’s attached to him despite the orange SF insignia on his black cap in his picture on the front, the cap the announcers like to mention flies off his head a lot when he’s running. The theoretical juxtaposition lingers for a moment. Willie Mays. New York. Mets.

Then, within two months, the punctuation changes. Willie Mays, New York Mets.

Willie Mays, New York Mets!

The mind boggled. It remains boggled. I’ve since lived numerous times through the happy shock of learning that big Met trades had been made and that big names were suddenly Met names: George Foster; Keith Hernandez; Gary Carter; Mike Piazza; Roberto Alomar; Johan Santana; Yoenis Cespedes. And regardless of the for-better-or-for-worse impact that rippled out of those respective big frigging deals, nothing — nothing — measures up in my formerly nine-year-old mind to learning that Willie Mays was suddenly of the New York Mets.

Willie Mays, New York Mets!

There was a backstory that made sense as to how and why this could have happened and had to happen, and it was connected to the lines below Trenton and Minneapolis and above San Francisco on 1972 Topps Card No. 49. “New York N.L.” wasn’t just dusty ledgerkeeping. “New York N.L.” was where Willie Mays became Willie Mays. It was about more than a Rookie of the Year award in 1951 or an MVP in 1954. It was about an impression made and an impression left and a heart that couldn’t be transported lock, stock and barrel to San Francisco. Willie Mays hadn’t been a home team player in New York for fifteen years, but when the orange NY, which was now embroidered onto royal blue caps, was provided for him anew, he put it on and it fit perfectly. The trade became official as of May 11, 1972: pitcher Charlie Williams and cash that Horace Stoneham needed, for Willie Mays and a return to the loving arms of Joan Payson and the city that never forgot him. Jim Beauchamp, acquired from St. Louis in the offseason for Art Shamsky, graciously gave up the 24 he’d inherited from Art and handed it over to Willie, because Willie Mays, 24 for the New York Giants, was now going to be 24 for the New York Mets.

The mind boggled some more.

Willie Mays, you likely know, played in his first game as a Met versus the Giants, at Shea Stadium on Mother’s Day, in the Mets’ 24th game of the year. You’d think that would be too much symbolism for one ballgame to hold. In the bottom of the first inning, Willie, starting as first baseman rather than center fielder in deference to his being 41, led off the Sunday affair of May 14 by walking and then scoring on Rusty Staub’s grand slam in the first (getting Rusty Staub from the Expos in April was also pretty mind-boggling). In the fifth, with the score tied at four, Willie led off again. This time he homered for the 647th time in his career. The heavens wept. Technically, it was a little rainy, but c’mon. You didn’t need to go back to 1951 with Willie Mays and the New York Giants to understand that this was transcendent. You didn’t need to know the word “transcendent,” even. You could be nine, a fan since you were six, and soak in the wonder of it all. This was a Foxwoods commercial before there was a Foxwoods.

Willie’s homer won the Mets that game over the Giants, and Willie’s play continued to help the Mets win for weeks to come. They were the best team in baseball with the best baseball player there was, and all it took to get him was a Quadruple-A pitcher, Mrs. Payson’s discretionary funds and unabashed sentimentality. The Mets reeled off eleven wins in a row at one point and were 30-11 as June dawned. Willie reached base in the first twenty games in which he came to the plate. Baseball cards didn’t include on-base percentage in 1972, but had Topps had the capability and foresight to rush a modern rendition out to reflect the first not quite seven weeks of Willie Mays’s second “New York N.L.” tenure, it would have noted his OBP between May 14 and June 27 was .463 and his OPS was .914.

Coming home and going, going, gone! (Photo by Life magazine) Better from my perspective than a new Willie Mays card was the gander I got at the May 26 issue of Life magazine. It, like me, was sitting in the waiting room of my sister’s orthodontist, a fellow soon to become my orthodontist, lucky me. I’d be bracing myself for life with braces long after Life ceased weekly publication. George Wallace was on the cover. Him I wasn’t too concerned with. Inside, on pages 38 and 39, was a spread that made me say, in so many words, “HEY!” It contained — along with an appropriate headline (“Willie Forever!”); a brief explanation of Mays’s May 14 exploits; and a picture of the Mets first baseman’s glorious swing off Giants reliever Don Carrithers as San Francisco catcher Fran Healy watches helplessly — a reproduction of every Willie Mays Topps baseball card from 1952 through 1972. There was the one I got in that first pack. And there were the 1971 and 1970 ones I opened pack after pack in unanswered hopes of getting. And there were what Willie Mays cards looked like in the years before, not just the years from when I’d had cards, but back to the early ’60s and the ’50s, which was the first time I’d ever seen what a baseball card manufactured prior to 1966 looked like.

Most breathtakingly, there was Willie Mays wearing a black cap with an orange NY over and over, representing the New York Giants, which floored me. It wasn’t the first time I’d seen that cap, but it was the first time it truly hit me what this homecoming was all about — and from whence the Mets sprung in terms of lineage. I knew we were an expansion team. I knew something about Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants. But here, in living color, was current New York Met Willie Mays — the best of baseball players — being then-current New York Giant Willie Mays. This array of baseball cards said a million words.

There was something familiar about that NY. It was then and there that I pledged retroactive fealty to the New York Giants and their orange NY. And it was then and there that I became intractable in my belief that there was nowhere Willie Mays was supposed to be in 1972 and 1973 other than in a uniform that allowed to him to finish his career wearing that orange NY.

Mays didn’t keep up his blistering on-base pace and the Mets didn’t keep up theirs in the winning percentage column. Staub got hurt. Everybody got hurt. The Mets fell from first to a not especially compelling third. Willie was a legend who apparently required a bit of care and feeding regular players didn’t rate. Yogi Berra, the legend who never sought to manage the Mets but had the job thrust on him after the death of Gil Hodges, was put in an awkward position of calculating when he could play him and when he could sit him. After the initial burst of euphoria, Willie Mays in his superstar emeritus phase and the Mets just trying to finish the season didn’t necessarily constitute an ideal marriage.

I didn’t grasp any of that at age nine. I spent the rest of 1972 in a haze of ecstasy that Willie Mays the New York Giant was a New York Met who had hit a home run to win a game versus the San Francisco Giants and that he was — past tense notwithstanding — the best player in baseball. It didn’t matter to me that Hank Aaron passed him on the all-time home run list. I rooted for Aaron to catch Ruth. I liked Aaron from a distance, but there wasn’t nothing particularly New York about him. Mays, as Life made clear, was meant to be ours. Mays was meant to be on my team. Mays was meant to be a Met. It wasn’t that he was the best. It was that he was the best here, for us — for the version of us that preceded us. That orange NY spoke volumes to me.

So he’d stay into 1973 when, save for the occasional reminder of what had made him famous more than twenty years before, he played like a 42-year-old. He was still Willie Mays. He was still named to the All-Star team because he was Willie Mays. He still drew ovations at Shea because he was Willie Mays. He didn’t play like the Willie Mays everybody who’d seen him in 1951 and 1954 swore by. He didn’t play like the Willie Mays I saw for myself in May and June of 1972. He was said to be about as done as the last-place Mets were in the summer of 1973.

But I wouldn’t have traded those two years of Willie Mays for anything or anybody. I wouldn’t have traded him for Hank Aaron, Johnny Bench or any of the in-their-prime future Hall of Famers from the All-Star Game three years earlier. I wouldn’t have asked to have Charlie Williams back had Charlie Williams gone to California and turned into Nolan Ryan rather than remaining Charlie Williams. I had Willie Mays as a New York Met when I was nine and ten. Maybe Willie was too old to play like he did when he was a kid, but I was old enough to get why it didn’t matter. I got the New York Giants connection. I got the meaning behind the ovations. I got why baseball made people not just happy but weepy. It all came together on the night of September 25, when Willie Mays and his 660 home runs — same number Topps would put into its base set of cards over the next few years — said “goodbye to America” in a New York Mets uniform at a packed Shea Stadium. The Mets had improbably scratched and clawed their way into first place. Willie, who’d been hurting and sitting the previous few weeks, gave them his blessing. You gotta believe you me that they won the division and, with Willie pinch-hitting at a critical juncture in Game Five of the playoffs versus the Reds, the pennant.

Perfect ending…except there was that little matter of the Say Hey Kid being pressed into center field action in the literal glare of the Oakland Coliseum in the second game of the World Series and the image of old man Mays being overmatched by fly balls and gravity. By not being as ageless as he had to be (in a game that, oh by the way, the Mets would win in extras on Willie’s RBI single), the best player in baseball became a metaphor for athletes who hang on too long, and Willie Mays’s presence in a Mets uniform would embody something that it was generally decided never looked right. “Mets legend Willie Mays” is supposed to be a guaranteed chuckle-generator on social media, as if coming home to play before appreciative fans who never forgot you somehow factors out to a net negative. Even the stupendous Joe Posnanski, in recently declaring Willie Mays the No. 1 baseball player who’s ever lived — better than Ruth, better than everybody — fell down the well of Willie falling down in center.

Tom Seaver, you may recall, tried to make a comeback with the Mets in June of 1987. The pitching staff was riddled by injuries and Tom was sitting home in Greenwich without a contract. He was 42, but had been solid enough for the Red Sox when he was 41 and, technically, he had never retired. Apparently, though, 41 was the upper limit for 41, because Tom’s comeback attempt lasted only a few weeks and never resulted in his actually coming back. After Barry Lyons roughed him up in a simulated game, Tom definitively announced his retirement at a press conference, admitting his fabled right arm contained no more competitive pitches.

But what if Tom had hung in there a little longer and convinced himself as well as Frank Cashen and Davey Johnson that he had something left? The Mets were sorting through Don Schulze and John Mitchell and whoever that summer. It’s not inconceivable that Tom Seaver could have reached down a little deeper and given the Mets the quality innings they needed to bridge the gap from June to October. So let’s say that happened. Let’s say Tom Seaver helps pitch the Mets to the 1987 division title, then the 1987 National League pennant and, finally, the 1987 World Series. And then, because this is all hypothetical, let’s say Tom Seaver takes the mound at the Metrodome and, figuratively if not literally, falls down on baseball’s biggest stage and that’s how his career ends, forty-two-year-old Tom Seaver, who didn’t know when to quit, implodes with everybody watching.