The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

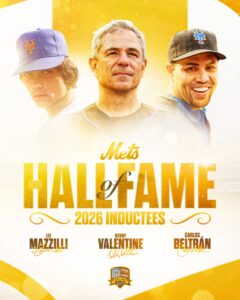

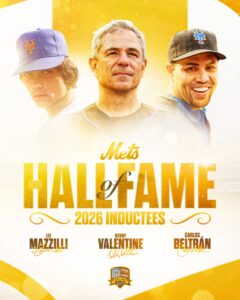

by Greg Prince on 20 November 2025 6:16 pm A more consistently robust, perhaps less finicky team Hall of Fame — the kind of institution that steps to the forefront with some regularity before mysteriously fading from view between releasing its intermittent puffs of orange and blue smoke — would have already included the three members the Mets recently announced as their 2026 inductees. Lee Mazzilli last played for the club in 1989, Bobby Valentine managed it in 2002, and Carlos Beltran most recently took the field for the home folks in Flushing in 2011. There was probably a stray Saturday on a random homestand that could have been dedicated to honoring any one or all three prior to whichever date is circled for next season, but as a fan who will always toast this franchise celebrating every nook and cranny of its history usually winds up concluding, when it comes to the New York Mets Hall of Fame, the important thing is they’re in now.

Per usual, the reveal for this Mets Hall class fell out of the sky without warning, hewing to no established pattern. Still when it showed up in the second week of November, it landed as pleasingly as it did surprisingly. Bobby V was the most accomplished Met manager not already in the Hall. Beltran, who may be kept busy at more than one such ceremony this summer, is cited every Hot Stove season as the most impactful long-term player the Mets ever engaged through free agency, maybe the most all-around talented in-his-prime position player they’ve ever had. (That description might have fit Vladimir Guerrero, but that’s a different story I’d recommend reading.) And Mazzilli? If you were in love with the Mets when they were at their least, Mazz was simply the most.

My heart is most warmed by the selection of Bobby Valentine, who elevated a moribund on-field product shortly after he took over as skipper and kept it aloft via a dizzying juggling act for a half-decade. My head is totally on board with Carlos Beltran, who did it all when healthy and did as much as he could when something short of 100%. My extremities tingle at the notion that Lee Mazzilli is a part of all this, because Lee Mazzilli, in his first term, was close to all we had, with his second term serving as a rare Recidivist victory lap, not just for him, but the greater Met good. My heart is most warmed by the selection of Bobby Valentine, who elevated a moribund on-field product shortly after he took over as skipper and kept it aloft via a dizzying juggling act for a half-decade. My head is totally on board with Carlos Beltran, who did it all when healthy and did as much as he could when something short of 100%. My extremities tingle at the notion that Lee Mazzilli is a part of all this, because Lee Mazzilli, in his first term, was close to all we had, with his second term serving as a rare Recidivist victory lap, not just for him, but the greater Met good.

I like that there are connections to be divined inside this triangle. Valentine and Mazzilli were Met teammates (the 1977 Mets, who lost 98 games, can now claim eight Mets Hall of Famers among their forty players used). Mazzilli and Beltran were All-Star Met center fielders three decades apart. Beltran and Valentine were Met managers, though Carlos B’s counting stats never got a chance to match Bobby V’s. Mazzilli won a World Series as a Met. Valentine managed the Mets into the World Series. Beltran…so close, but Game Seven of the NLCS is no also-ran destination. Carlos was the top player on arguably the top team the Mets have fielded since the era Mazzilli came home. Bobby V steered the ship as close to the shores of the promised land as anybody since Davey Johnson brought us into port, and according to proprietary Personality Above Replacement analytics, he never failed to fascinate.

When these three Mets become Mets Hall of Famers, membership within the Mets Hall of Fame — which in September passed its 44th anniversary — will rise to 38. Collecting ballots from my heart, head, and extremities, I’m confident I could increase that total legitimately by half without clicking once on Baseball-Reference. It’s a team Hall of Fame. It’s our team Hall of Fame. We understand what our team is and what has made it our team for going on 65 seasons. A Hall of Fame representing our team oughta be fulsomely populated with individuals who have left indelible marks in our hearts and heads and along our extremities. I truly believe that between 1962 and the present, we’ve had far more than 38 of those. There’s a bar to be set that stays true to studied selectivity, yet recognizes even implied exclusivity can benefit from occasional touches of generosity and malleability.

A little less pickiness to the process isn’t going to devalue any of the plaques currently hung at the top of the Rotunda stairs, and I doubt “Lazy Mary” will be sat out in mass protest if it’s decided “a great Met” encompasses multiple meanings. For this class, the picking worked quite well. Welcome to the certifiably upper echelon, Bobby, Carlos, and Lee.

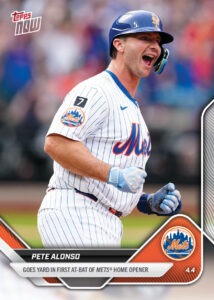

by Greg Prince on 17 November 2025 5:42 pm Pete Alonso didn’t hesitate after the final frustrating game of a frustrating season ultimately torpedoed by frustrating losses. He was asked if he planned to exercise the opt-out clause in his contract in order to test the open market, and he said yes. Edwin Diaz wasn’t quite so quick on the withdraw; he’d have to discuss it with his family, he said, but he sure as hell didn’t immediately rule out becoming a free agent. Eventually, Edwin joined Pete in declaring his availability. Three days after the World Series, both men filed.

Back on September 28, following the defeat to the Marlins that ensured the Mets would have nothing to do with the 2025 World Series, neither Met evinced any hard feelings toward the club they’ve helped define since 2019, let alone an overwhelming desire to bolt. Pete affirmed he’s “loved being a Met,” while Edwin insisted, “I love this organization.” Their sincere affection notwithstanding, they are professionals who have business decisions to make. If business brings them back, that will be swell. If business takes them away, that will be a shame. “They’ve been great representatives of the organization,” David Stearns said at November’s General Manager Meetings, the precursor to December’s winter meetings. “We’d love to have them both back.” Implicit in our POBO’s benign endorsement was having them back could happen if the price, encompassing length and dollars, is right from a Met perspective. If front office executives didn’t have to worry about such matters, there wouldn’t be much need for them to meet multiple times per offseason.

It’s not easy to detect overwhelming individual value following a season when no single Met produced quite what was required to transcend a massive accumulation of frustration and shove this team as a whole where it seemed so close to getting. Yet when the Faith and Fear in Flushing Awards Committee (FAFIFAC) convenes to select a Richie Ashburn Most Valuable Met, we always find somebody — even in the stone downer seasons that were far less competitive than 2025 and encompassed no player with numbers up to the standard of some we saw posted in 2025. In 2023, for example, when the Mets lost 26 more games than they had the year before and were never a factor in the postseason race, we were sorely tempted to name Nobody as our MVM. We resisted the temptation because, honestly, FAFIFAC doesn’t find opting into Nobody much fun.

We will not deny that…

• Nobody in 2025 lifted the Mets onto his shoulders;

• Nobody in 2025 elevated the Mets into the playoffs they were mathematically on target to make from April deep into September;

• and Nobody in 2025 proved particularly valuable when it came to preventing the gradual decline and emphatic fall that plopped the Mets one tiebreaker shy of the third and final National League Wild Card.

But despite our pervasive frustration, we’re not going there. Offseason reflection and perhaps rationalization perennially yields an MVM, maybe more than one. Even in the lousiest of Met years, of which we’ve experienced a few. Even in the frustratingest of Met years, of which few were more frustrating than this one — for even within the spelling of frustration there can be found fun.

And within what fun there was to experiencing the 2025 Mets, you inevitably found Pete Alonso and Edwin Diaz. We opt to honor them as Faith and Fear in Flushing’s co-choice for the Richie Ashburn Most Valuable Met award. Alonso and Diaz do have business to attend to, as does the ballclub that they’ve called theirs for seven seasons, but we don’t mind copping to a touch of sentimentality in making this selection.

Pete? We’ve grown accustomed to his bat.

Edwin? We’ve grown accustomed to his saves.

They’ve been here longer than almost any of their teammates. They’ve filled critical roles from the moment they settled in. They’ve starred and starred again. We know who they are. We know who they’ve been. They’ve filled us with anticipation more than dread, 80/20, at least. They’ve come through when needed more often than not.

There is some lifetime achievement factored into this decision, as well as some of what wasn’t as present in 2025 as it had been in 2024: vibes. Flawed as they could reveal themselves at a given moment, you welcomed Pete and Edwin into the spotlight when they strutted into it. Those good vibes we felt at the sight of them weren’t only about personality and familiarity. They were performance-derived.

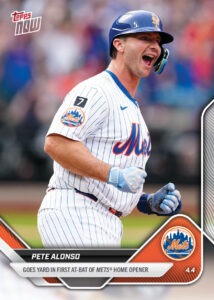

Pete Alonso crashed into 2025 with a certified Player of the Month entrance. Twenty-eight runs batted in before May. A .343 batting average. Eleven doubles to go with seven homers, indicative of not just a slugger but a hitter in a groove. When he re-signed in early February, he sat 26 home runs shy of the franchise record. April ensured beyond any doubt that he’d make it there by summer. On August 10, in the weeks following his fifth All-Star selection, Pete passed Darryl Strawberry, belting the 253rd longball of his major league and Met careers, epochs that had been one and the same since their very beginning. The power show that earned him his first Silver Slugger continued clear to the 161st game of the season, when Pete was as Pete could be, not only delivering the first two runs of a necessary 5-0 victory in Miami (on his league-leading 41st double, then his 38th homer, bringing his RBI total to 126), but summing up his pregame prep afterward for Steve Gelbs: Pete Alonso crashed into 2025 with a certified Player of the Month entrance. Twenty-eight runs batted in before May. A .343 batting average. Eleven doubles to go with seven homers, indicative of not just a slugger but a hitter in a groove. When he re-signed in early February, he sat 26 home runs shy of the franchise record. April ensured beyond any doubt that he’d make it there by summer. On August 10, in the weeks following his fifth All-Star selection, Pete passed Darryl Strawberry, belting the 253rd longball of his major league and Met careers, epochs that had been one and the same since their very beginning. The power show that earned him his first Silver Slugger continued clear to the 161st game of the season, when Pete was as Pete could be, not only delivering the first two runs of a necessary 5-0 victory in Miami (on his league-leading 41st double, then his 38th homer, bringing his RBI total to 126), but summing up his pregame prep afterward for Steve Gelbs:

“I’m wearin’ Juan Soto’s socks, I put on Francisco Lindor’s eyeblack, and then I used Brandon Nimmo’s lotion. So, all my teammates, I’m just thankful for the good vibes.”

Gelbs asked Alonso when he decided to borrow his peers’ gear. Pete responded with his why:

“Anything for a win.”

By late in the season, anything for a win implied Edwin Diaz would be coming in. To save a game. To save a chance to win a game. To save what was left of the season. His two scoreless innings in Game 162 spoke to either Carlos Mendoza’s desperation or sound judgment. In the fifth inning, on the heels of stints from Sean Manaea, Huascar Brazoban, Brooks Raley, Ryne Stanek, and Tyler Rogers, Mendy called on Edwin. The Mets were down, 4-0. The Mets’ closer couldn’t get the Mets closer, but he was the best and perhaps only bet to keep the damn thing from getting away. Sure enough, Diaz faced six batters and retired them in order. It didn’t help prevent the 4-0 loss that ended 2025, but it was all Edwin could give, and he gave it when needed most.

That was usually in the ninth inning. None of the righty’s ninth innings stands out more in recent memory than the one that arose when Diaz was wearing only one good shoe. The two-time 2025 Reliever of the Month — he’d made the All-Star team in July and be named the NL’s Reliever of the Year in November — unleashed the entire Edwin experience in an early-September outing in Cincinnati that, by itself, could be reaired as a Mets Classic.

It’s 5-4, Mets.

He gives up a leadoff single to Ke’Bryan Hayes

He walks Matt McLain on a full count.

He walks TJ Friedl on four pitches.

The bases are loaded.

He strikes out Noelvi Marte on a full count.

He goes to one-and-two on Elly De La Cruz.

He changes his shoes on the mound.

He finishes striking out De La Cruz.

He elicits a grounder from Gavin Lux.

He scampers to first base while Luisangel Acuña tracks down the ball a sizable distance from his position at second base.

He receives Acuña’s toss from the outfield grass ahead of Lux reaching the bag.

It’s still 5-4, Mets.

The game is over.

Letting a ninth-inning lead slip away is out of no closer’s purview. Loading the bases usually foreshadows such a shift in momentum. But Diaz is as capable of striking out batters in a tense situation as he is of letting runners score. Previously, he hadn’t shown an automatic instinct to cover first, but he worked on that in 2025. As for the shoes…well, a spike broke off, and he did something about it. Edwin changed his shoes and perhaps perceptions that a ninth inning on the precipice of going monumentally wrong automatically plunges from a cliff.

The escape in Cincy yielded Diaz his 26th save of the season. That he didn’t have a whole lot more than his final sum of 28 at season’s end reflects more that went wrong with the Mets as a whole than many Edwin’s innings going awry. His teammates seemed to studiously avoid presenting him with save opportunities in August and September, yet when the trumpets sounded for Diaz, he was as close to his 2022, pre-injury incarnation as could be reasonably hoped. Edwin threw more innings than he did in his signature season and compiled an ERA+ (248) nearly as staggering as he did three years before (297).

Imperfections resonate in the course of a season, especially one as frustrating as 2025. Diaz isn’t great at holding runners on. Alonso occasionally makes his pitchers lunge uncomfortably for throws to first. But, boy, imagine the Mets since 2019 without their contributions. Hell, just their presence is Amazin’. Pete has played in every Mets game since June 18, 2023, a franchise-record 416 in a row. In a year when Mendoza tapped 43 different Mets to pitch in relief (including three position players), Diaz remained ostensibly available day after day, on the active roster for every single game, joined by only Stanek in the durability department.

Nobody is irreplaceable, but good luck slotting in somebody else in their respective niches. We as a people could be forgiven for forgetting there was life before Sugar and the Polar Bear. If you’re crafting an all-time Mets team or two, Edwin has earned prime consideration to be designated Metropolitan history’s top righthanded reliever, outpointing Jeurys Familia by now (without being quite the mixed bag Armando Benitez was). Keith Hernandez is a longtime Mets fan’s instinctive choice for first base into eternity, but Pete has slugged his way into at least undeniable second-team status. Before there was OMG, Pete was the acronym activator who changed how we hashtag (#LFGM). And, due respect to even the legendary lefties like Tug and Jesse and Johnny from Bensonhurst, before there was Timmy Trumpet, there was nothing like it.

Quietly, the Mets have maintained a recognizable core to their cast, a feat that seems remarkable in light of how common turnover has become at the big league level. We know Alonso and Diaz like we know Nimmo, McNeil, Lindor, Marte, Peterson, and Megill; younger or more recently arrived Mets like Alvarez, Vientos, Baty, Senga, Manaea, and Soto all feel like part of our extended family, too. Family can warm you all over. They can also drive you crazy. These members of our Mets family together have produced successes as well as frustrations. You live with that as a fan. Maybe you have no choice. Honestly, it’s refreshing in this day and age to know who’s on the team year after year.

When I became a fan, I knew who was going to comprise the heart of the Mets most every year. There were successes and frustrations then. We welcomed some new guys along the way, we got to know them, and we rooted for the reconfigured version of our Mets family. We believed in them. The belief wasn’t always cashed in, but we had our guys. This core, fronted as much by Pete and Edwin as any of their long-term teammates, has given us enough to believe in. It doesn’t mean you don’t reckon with the breaking up of portions of the band, especially when sticking with the same players is deemed a detriment to moving forward, but I think it does mean you ought to proceed with extreme caution before deciding to swap out some of your most proven and impactful instrumentalists.

I have no idea who would play first base and hit more than 30 home runs annually if Pete Alonso isn’t a Met. I have no idea who would reliably secure ninth-inning leads if Edwin Diaz isn’t a Met. These have been the guys we’ve wanted to see, the guys we’ve conditioned ourselves to crave in that mythic big spot, the guys who planted in us confidence that we knew what we’d be getting and we’d be glad we got it. Sometimes we didn’t get the desired outcome, and that sucked. But usually we got what we anticipated, and that rocked.

Maybe it still will. Yet if one or both among Pete Alonso and Edwin Diaz should sail, this seems as good a moment as any to say out loud that not only have they been wonderful Mets, but having them here has been incredibly fun.

FAITH AND FEAR’S PREVIOUS RICHIE ASHBURN MOST VALUABLE METS

2005: Pedro Martinez (original recording)

2005: Pedro Martinez (deluxe reissue)

2006: Carlos Beltran

2007: David Wright

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Pedro Feliciano

2010: R.A. Dickey

2011: Jose Reyes

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Daniel Murphy, Dillon Gee and LaTroy Hawkins

2014: Jacob deGrom

2015: Yoenis Cespedes

2016: Asdrubal Cabrera

2017: Jacob deGrom

2018: Jacob deGrom

2019: Pete Alonso

2020: Michael Conforto and Dom Smith (the RichAshes)

2021: Aaron Loup and the One-Third Troupe

2022: Starling Marte

2023: Francisco Lindor and Kodai Senga

2024: Francisco Lindor

Still to come: The Nikon Camera Player of the Year for 2025.

by Greg Prince on 8 November 2025 3:58 pm The Mets didn’t play ball in October, and I learned to be OK with that, despite dedicating my waking hours from late March through late September to their ultimately insufficient quest to play ball in October. Maturity being what it is, I grew distant enough from the grating, granular shortfalls of the 2025 season to allow that losing out on a playoff spot by a tiebreaker is sometimes just how the ball bounces (or gets lodged at the base of an outfield wall). Hence, I could go about my October not hung up on who was not playing ball, and enjoy a helluva lot who was, and, when there were no games in progress, just think and talk about other things.

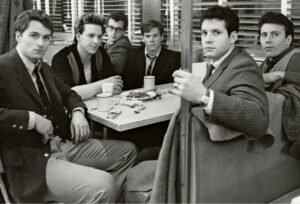

During a lull in the postseason, somewhere between the end of the ALCS and the beginning of the World Series, I got together at a nearby diner, as Long Islanders do, with the two friends I’ve known longer than anybody, not counting those with whom I share bloodlines. It would be simpler to say they’re my two oldest friends, but I’m a little older than each of them, and it would be just like me to point that out to them, not as a badge of personal longevity, but because of my fondness for exactitude. Had I mentioned that, it likely would have earned me a pair of stares before the conversation quickly pivoted somewhere else, probably toward that episode of Welcome Back, Kotter we watched together in afternoon reruns when we were high school seniors, the one in which Vinnie Barbarino murmurs, “gimme drugs, gimme drugs,” over and over to howls from the studio audience. However one sorted the technicalities of longest and oldest, it was an overdue meetup, as they all are at this stage in life, and like all our too-rare get-togethers, I couldn’t tell you what we talked about, exactly. Except John Travolta pretending to be a stoner (for Freddie “Boom Boom” Washington’s sake) on Kotter.

“When a woman asks a man — back from golf, the bar, a game — what he and his buddies talked about for the last four hours, the mumbled reply of ‘Nothing’ isn’t designed to drive her insane,” S.L. Price reasoned in his 2012 Vanity Fair retrospective on the enduring influence of Barry Levinson’s 1982 classic period piece Diner. “It was, indeed, four hours of ‘nothing’ which, for guys is…everything. It’s in what’s not said — the tone, the pauses.”

There was one pause I noticed when I groped to capture the contents of the afternoon for my wife, but mostly came up devoid of details, other than I ordered a Reuben with potato salad, and it came with fries, but the fries looked good, so I didn’t say anything to the waiter. I had paused my instinctual inclination to veer off into baseball and the Mets. One of the two guys at the table with me is a lifelong Mets fan, currently geographically displaced. His Amazin’ simpatico was my sports salvation through junior high and high school. The other isn’t into sports, but has been sympathetic to our cause these past many decades. Neither of them brought up the Mets, and I wasn’t tempted to, either. Other than a stray reference to a clip of some uniquely Canadian pennant fever I’d glimpsed after the Blue Jays clinching the American League flag the other night (fans ran into the street, but dispersed when the traffic light changed, which was apparently from a 2015 ALDS celebration but got reposted), and my recollection that the last time we were together was at Citi Field seven years ago, baseball didn’t as much as flicker within our rolling dialogue. My overriding obsession took a back seat to, well, nothing.

Just like in Diner, I suppose, except in real life, which, incidentally, is where I first saw the fictional Diner, with a group of friends that included at least one of these guys from lunch in October, maybe both; forgive the inexactitude forty-three years later. In a lovely cosmic coincidence, I’d had Diner sitting on the DVR from the last time TCM aired it. One night shortly after that late lunch with my friends, an evening when the 2025 World Series wasn’t showing, I rewatched Diner for the first time in ages.

“It still holds up” is an understatement. I wasn’t old enough upon Diner’s initial release to fully appreciate it, and I appreciated it plenty when I was nineteen. Most movies I’ve loved forever are like this, me not noticing that line wasn’t just a good line, it had something to do with something else from earlier in the movie, and it will come back around later to reveal something else. Or it’s an even better line than I realized the last time I rewatched this. Diner is as rewatchable as a rewatchable gets.

One thing, however, bugged me during this Diner rewatch. The throughline of this film set in Baltimore between Christmas Night and New Year’s Eve 1959 is the Colts. One of the guys at the diner, Eddie (Steve Guttenberg), is nuttier about the Colts than the rest of his pals. Eddie is so nutty about the Colts that he is going to make football knowledge a prerequisite of his upcoming nuptials — he’s finalized a comprehensive quiz for his fiancée to ensure she is indeed the right girl for him…or give himself an out in case he’s overcome by cold feet. The color scheme for the wedding, including the bridesmaids’ dresses, is blue and white. Most importantly, the gang will be getting together Sunday to go to the NFL championship game at Memorial Stadium. Everybody else agrees meeting at noon will suffice. Eddie insists on a quarter to twelve, because, you know, it’s the championship game. One thing, however, bugged me during this Diner rewatch. The throughline of this film set in Baltimore between Christmas Night and New Year’s Eve 1959 is the Colts. One of the guys at the diner, Eddie (Steve Guttenberg), is nuttier about the Colts than the rest of his pals. Eddie is so nutty about the Colts that he is going to make football knowledge a prerequisite of his upcoming nuptials — he’s finalized a comprehensive quiz for his fiancée to ensure she is indeed the right girl for him…or give himself an out in case he’s overcome by cold feet. The color scheme for the wedding, including the bridesmaids’ dresses, is blue and white. Most importantly, the gang will be getting together Sunday to go to the NFL championship game at Memorial Stadium. Everybody else agrees meeting at noon will suffice. Eddie insists on a quarter to twelve, because, you know, it’s the championship game.

Exactly! Of course that’s how Eddie would think, because that’s exactly how I would think if the team I was craziest about in the world was about to play for the championship. You can’t take any chances, right? Except that scene from Diner came after many scenes in Diner when Eddie was doing other things besides concentrating on his beloved Baltimore Colts preparing to play for the National Football League championship. Barry Levinson may know his milieu like few directors have known theirs, but I’m sorry, there’s no way that if the Mets were in the World Series, I’d be calmly hanging out at the diner talking about sandwiches or Sinatra or anything but the Mets being in the World Series. If no one else wished to go over lineups with me, I’d be off in a room by myself pondering potential matchups. That would have been the case in October of 1982, just as it would have been the case in October of 2025. In fact, when our little group left the movie theater in the summer of ’82 — to head to a diner, naturally — the most quick-witted among us nodded in my direction and suggested, “Hey, let’s go to the Mets game!”

At the time, the Mets making a World Series was the stuff of cinematic fantasy, but yeah, “the game” is where my head would have been had the Mets of that era been the powerhouse that the Baltimore Colts had been in Diner’s. That’s where you indeed would have found my head in October of 1986, and October of 2000, and October of 2015. Priorities are priorities when a championship sits within your team’s grasp. Everything is different when your team is in it.

Just as it’s different when your team isn’t in it. You can go to the movies. You can go to the diner. You can think and talk about other things as well as nothing. You can also watch the ballgames your team isn’t in. Those can be classics, too.

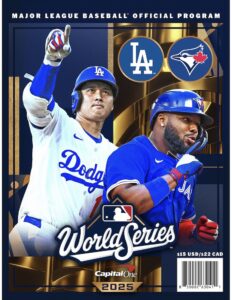

***“I think if we play tomorrow, we beat them,” Blue Jays pitcher Kevin Gausman assessed to reporters following Game Seven of the World Series, per Mitch Bannon of The Athletic. “But we’re not playing them tomorrow.”

No, Kevin, you were not. No Game Eight versus the Dodgers. No Game Nine. No games at all following Game Seven, the final satisfying course of a veritable Fall Classic feast, itself the last stage of an almost endless postseason bacchanalia of excitement and emotion blissfully free of ghost runners, even for those of us on the outside looking in. We should be filled up, yet we are never truly full when it comes to baseball. As the first utterly empty week of our lives in nearly three-quarters of a year has wound down, I’m not surprised I find myself continuing my emotional alliance with the likes of Gausman and, more widely, Blue Jays fans, regardless that I don’t know any. At my most directly invested, I’ve been Linus sitting on the curb beside Charlie Brown as Charlie Brown cries into the void, “Why couldn’t Kiner-Falefa have taken a secondary lead just two feet further?” I don’t know, Ontario version of Charlie Brown, but I feel ya and I hope, despite the outcome, that what transpired for Toronto across October of 2025 stays with you more as fun than torture.

I could have mentally aligned with the come-from-behind winners, but none of my internal affinity developed in the Dodgers’ direction. Respect and grudging admiration? Sure, why not? Of course the Dodgers are the world champions again. They’re the Dodgers. It’s been their world for a while. They might as well keep the title to confirm ownership. Preordainment didn’t demand they win it all, but the element of surprise has only so many tricks up its sleeve. The Dodgers embody abundance. There’s just so much of them. You get past the megastars, there are superstars. You get past the superstars, there are stars. You get past the stars, there are studs and stalwarts and substitutes who inevitably find a way to come through. You rarely get past all that, though if you do, you might bump into a living legend who is now consigned to the status of museum piece, except when he enters in the top of the twelfth to extricate his team from a bases-loaded jam. The instinct when the Dodgers come to work will always be to bet the over, even if it only seems like they always win.

Thirteen consecutive postseason appearances.

Gotta be more.

Five pennants in nine years.

Seems light.

Three of the past six world championships.

That’s it?

The most vital counting stat is the Los Angeles Dodgers of 2024 and 2025 are the most recent team to have won consecutive World Series, ensuring reflexive references to the team that repeated as world champion in 2000 will be reduced dramatically during future postseasons.

October is crammed with contemporary components that can shake out in any direction. Or they can just pour straight from of the sack in predictable fashion. Twelve teams go into the mix at September’s end. Eight have to play off to become four, with those four playing the four who sit and wait. From there, we have four, then two, then, at last, one. Anything can happen. It is designed so anything can happen, or so that fans can believe anything will happen. Two years ago, though it seems far more ancient now, the postseason process yielded the five-seed Texas Rangers defeating the six-seed Arizona Diamondbacks in baseball’s final round, concrete evidence that randomness can occasionally rule October.

This year, like last year, these Dodgers happened. When these Dodgers happen, apparently nothing can stand in their way.

Los Angeles, as if to present itself a challenge, accepted as roundabout a route as a 93-win team could receive. A Wild Card Series, in which they flicked the Reds — briefly occupying the presumed Met slot — aside in two games. Ceding all-important home field advantage for the rest of their run, L.A. strung along the Phillies until eliminating them in four during the National League Division Series (with Philadelphia assisting by essentially eliminating themselves at the conclusion of the final game), then whooshed by the senior circuit’s nominal top team, the Milwaukee Brewers, in a sweep. Each of those NLCS contests left behind a close score, but in the mind’s eye, it was a big blue stampede.

The series that decided the pennant was when I gave up on hating the Dodgers. I still don’t particularly care for them, mind you, but I had my Utley-stemmed animosity reduced to a shrug emoji. I liked the way the Dodgers pitched their way past the Brewers, which was with starters staying in as if that’s what their job description entailed. It was refreshing to experience, regardless of who was doing it.

The effort that pushed the Dodgers over the top, a predictable destination for a franchise whose logo could be a cornucopia, was that of Shohei Ohtani as pitcher and hitter in Game Four, the Friday night he struck out ten and homered thrice. When he accomplished all that, it was immediately and universally proclaimed the greatest game any individual had ever put forth. Truthfully, you couldn’t compare Ohtani’s crowning glory to anybody else’s, because what he did was incredibly incomparable. The only downside to it is any game when he doesn’t strike out ten while homering thrice — like that eighteen-inning night he got on base nine times (four times via intentional walk) but didn’t bother to pitch — is bound to come off as a mild disappointment. The Dodgers, when they peak, have all the starting pitchers, most of the hitters, momentum as a default setting, and drip relevant history. In Ohtani, they’ve combined the lot of it.

The shock-surprise quotient, in which one is shocked but not surprised, barely applies to Shohei. That he does everything he does is neither shocking nor surprising, never mind that nobody else does what he does. The Dodgers returning to the World Series was about as unsurprising as a postseason step could be. Yet when you delved into the details…nope, it was pretty much what you might have figured.

Would have one figured on the Blue Jays alighting to meet them? At the outset of the postseason, not necessarily. Who the hell knows what goes on over in the other league? Yet after the Jays did humanity a solid and dispatched the Yankees, they deserved closer consideration. As they clashed with Seattle, their possibilities were undeniable. For a spell, however, it was the Mariners’ year, much as it was the Brewers’ year when the year was no further along than August. Baseball years can be hot potatoes as they progress. The M’s had the Big Dumper and J-Rod and intoxicating charisma you hang a temporary hat on. The M’s had that cheek that had never been kissed by a date in the World Series. The M’s withstood a fifteen-inning breathholding contest versus Detroit just to advance to the ALCS, back when fifteen innings seemed like a lot. The wind was at the back of the Mariners clear to the nights it reversed course inside Rogers Centre, and suddenly, it was the streets of downtown Toronto, rather than the streets of Seattle, filled with revelers. Would have one figured on the Blue Jays alighting to meet them? At the outset of the postseason, not necessarily. Who the hell knows what goes on over in the other league? Yet after the Jays did humanity a solid and dispatched the Yankees, they deserved closer consideration. As they clashed with Seattle, their possibilities were undeniable. For a spell, however, it was the Mariners’ year, much as it was the Brewers’ year when the year was no further along than August. Baseball years can be hot potatoes as they progress. The M’s had the Big Dumper and J-Rod and intoxicating charisma you hang a temporary hat on. The M’s had that cheek that had never been kissed by a date in the World Series. The M’s withstood a fifteen-inning breathholding contest versus Detroit just to advance to the ALCS, back when fifteen innings seemed like a lot. The wind was at the back of the Mariners clear to the nights it reversed course inside Rogers Centre, and suddenly, it was the streets of downtown Toronto, rather than the streets of Seattle, filled with revelers.

So we who dutifully tune into every World Series, even the Metless iterations, acquainted ourselves with the gamers, grinders, and second-generation Guerrero of the Jays, and we attempted to tease new storylines from their presence. The intensity of their extended moment in the postseason spotlight was so great that it took until Game Six, specifically the closeups of the outfield wall in Toronto when that ball got stuck at its base and morphed into a ground rule double, for me to recall where I knew that smoky blue with the powder blue trimming fence from. That was the fence Francisco Lindor homered beyond in September of 2024, that matinee when he broke up Bowden Francis’s no-hit bid in the top of the ninth of a game we absolutely had to have. From repeated viewings of Mets Classics, I’d recognize its distinct color scheme anywhere, yet I was so immersed in the Jays for the Jays’ sake, that the Mets of recent vintage had barely infiltrated my thoughts.

Flushing expats currently nesting north of the border needed to be processed on their newly Canadian terms. Chris Bassitt was now a gritty middle reliever rather than the starter who anchored our rotation for the bulk of 2022 until his shortcomings against Atlanta and San Diego weighed us down and helped sink us. Max Scherzer was back to being a citizen of October, not the ferocious fussbudget who engineered an escape from Queens in 2023. Andrés Giménez had long gotten used to hitting with runners in scoring position and with people in the stands, the latter of which he didn’t have the opportunity to do when he debuted with us amid the mandatory emptiness of 2020. I knew they’d been Mets once (just as I vaguely remembered backup catcher Tyler Heineman spending two months as a Paper Met in a the offseason spanning ’23 and ’24), but I didn’t see Metsiness in this World Series…save for a couple of AARRGGHH!!-inducing baserunning mishaps.

The Mets were a distant memory by the time this Series got going. Fine. I didn’t need to hear about them, not even in national-broadcast asides regarding our stars. Walks were worked out on full counts, and nobody invoked Juan Soto. Home runs went for long rides, and they weren’t deemed like something off the bat of Pete Alonso. By Game Three — the overnighter at Dodger Stadium that could have as easily played out in a clockless casino — the chat was limited to the actual participants. The Mets didn’t matter any less than the Mariners and the Brewers. Nothing mattered but the Dodgers and the Blue Jays. Give me a World Series that’s a World Series like this World Series, and eventually nothing else exists, just the two combatants and the prize for which they are vying down to the last heartbreaking swing. My first seven-game World Series was Pirates-Orioles in 1971. I was eight years old. I understood it transcended my standard parochial concerns. I rooted for the Pirates for a week like I’d usually rooted for the Mets. It helps to pick a side. The Orioles, like the Dodgers of now, were a little too familiar. I didn’t know the line about familiarity breeding contempt when I was eight, but I intrinsically got it.

The Dodgers were always going to represent the team we knew in this World Series. The Jays took on the role of the fresh face. Not as fresh as the Mariners would have been to the biggest stage, but fresh enough. Their World Series experience from 1992 and 1993 wasn’t salient to their modern-day endeavors except that the image of Joe Carter touching ’em all (he’d never hit a bigger home run in his life) remained accessible in our collective subconscious. Understanding Toronto had captured a pair of Big Ones in living memory — and noticing that Toronto is a large city and the Blue Jays have a large payroll — reduced the temptation to cast the AL champs as the scruffy upstarts in all this…even if against the Dodgers, almost anybody would be.

At the core of the World Series, we had the team that took out the Phillies versus the team that eliminated the Yankees. We were already blessed, regardless of outcome.

If you engaged with it, especially if you stayed awake for the marathon portions of it, this World Series evaded easy narratives. Once a handle was had on it, the handle grew slippery. When the Jays took a three-two lead, I read an article positing that if not for Yoshinobu Yamamoto throwing a complete game in Game Two and Ohtani producing so much offense in Game Three, the Series might be over. Uh-huh. And had the Jays kept missing their team bus, the Dodgers would have swept. There was no need to rush to conclusions. At various points, this World Series clearly belonged to the Dodgers, the Blue Jays, the Dodgers, the Blue Jays, and back and forth several times per night. I’d like to think the World Series belonged to everybody.

The Commissioner’s Trophy wound up in the Dodgers’ hands, once they prevented Games Six and Seven from landing in the Blue Jays’ mitts, with the Jays doing just enough to not wrap it within. The end result left me in mind of the 1975 World Series, when I rooted hard for the Red Sox, who fell to the Reds, and I couldn’t argue that the Reds hadn’t earned it, but I swore both teams not only could have won it, but should have won it. The 1982 World Series between the Brewers and Cardinals returned to my consciousness, too, probably because it followed the same trajectory of one team winning Games One, Four, and Five, and the other team (the one I was rooting against) winning Games Two, Three, Six, and Seven. Nobody in the 2025 World Series ever trailed by two games. No stubborn the home/road team has won every game pattern emerged. It always felt up for grabs. It felt, in some intangible manner, like a real World Series, the way snowstorms when you were a kid remain the snowstorms you still remember deeply. I don’t need two feet piling up outside in the months ahead. I’ll always take seven games to decide the world championship. In the wake of what we just experienced, all those World Series that went four, five (except for 1969, of course), or six games suddenly seem inauthentic. After seven games, particularly seven games like 2025’s, my inclination would be to give everybody a parade, sanction everybody to hoist nothing less than a WE WERE PART OF SOMETHING SPECIAL banner. One winner coronated, perhaps, but no losers detected. Hosannas all around.

My pro-Jays lean wasn’t as anti-Dodgers as I would have suspected. Maybe for the first time I truly understood why impressionable youngsters through the ages have gravitated to the overbearingly dynastic. The team you attach yourself to is relentlessly impressive, and rolling in their retinue becomes as rewarding as it is easy. Unwillingly witnessing what the Yankees were doing under Joe Torre in 1998 made me think this must be what it was like when Joe McCarthy was pushing buttons in 1938, or when Casey Stengel’s doublespeak c. 1958 was merely a sideshow rather than his main event. The Dodgers of Dave Roberts are in that territory. I can totally understand if soulless children, presuming baseball is on that demographic’s radar, gravitate to this franchise. The Dodgers have the biggest names. The Dodgers win a lot. If you came along within the past two years, the Dodgers win all the time. If you watched only this World Series, they never lost a razor-close game.

Like the 1960 Pirates, the 2025 Dodgers were outscored overall across seven games. Like the 1960 Pirates (Hal Smith and Bill Mazeroski), the 2025 Dodgers made hay out of a pair of home runs (Max Muncy and Miguel Rojas) hit in the eighth and ninth innings of the seventh game…then topped all that with an eleventh-inning home run (Will Smith) to capture the lead they never surrendered. The 1960 Pirates were a historic underdog, to Stengel’s last Yankees team. The 2025 Dodgers were the personification of an overcat, but didn’t scat when they were compelled to make comebacks. It helps to have resources. It’s even better when you can put them to good use.

The Dodgers always seem to know what they’re doing and how to do it. Then they do it. No wonder Steve Cohen five years ago mentioned wanting the Mets to grow up to be just like them within what were then the next five years. Hasn’t happened yet. Next year, perhaps. Always next year. Always perhaps. You can’t ask for more in November.

by Jason Fry on 4 November 2025 7:48 pm Offseason’s greetings everyone!

Hope you enjoyed the World Series, and aren’t too anxious yet about who will be next to employ Pete Alonso, Edwin Diaz or both. There’ll be time for that, promise.

For now, something to fill an hour very pleasantly: Welcome, Josh Levin, to the Wilbur Huckle Appreciation Society! For now, something to fill an hour very pleasantly: Welcome, Josh Levin, to the Wilbur Huckle Appreciation Society!

Twelve years ago — the night Dom Smith got drafted, as it happened — I wrote a little post about early Mets farmhand Wilbur Huckle, a pair of strange campaign buttons I’d run across, and the unlikely story of a cult hero who never quite got the call.

Levin found a Huckle button in a Kensington, Md., antique store, and had a lot of the same questions I did. But unlike me, he answered them — and those answers add up to a fascinating tour through American pop culture, political theater, and of course Mets history. Before you come out of the Huckle rabbit hole, you’ll have heard from Ron Swoboda, Rod Gaspar and from Huckle himself — who may never have been an official big-league ballplayer but sounds like he’s lived a pretty wonderful life.

This is the inaugural episode of Levin’s new podcast series Replay Booth, and if the premiere is any indication, we’re all in for a treat. To which I’ll add my own little afterword: A while back, using an old Topps photo unearthed and shared by Keith Olbermann, I made a custom ’65 Huckle. (Which of course recognizes his Metropolitan Party candidacy in the back bio.)

It’s not a card that ever existed, just one that should have.

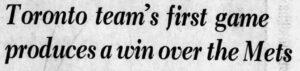

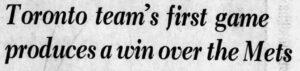

by Greg Prince on 9 October 2025 10:03 am Symptomatic of the proliferation of Interleague scheduling, the Mets opened their home season against the Toronto Blue Jays this past April, winning three straight. It was fun in the moment, even if the moment didn’t portend anything special for the 2025 Mets in the long run. It also didn’t indicate there were any obstacles the Blue Jays couldn’t overcome as necessary in New York. Slightly more than six months later, the Jays returned to the city needing to win at least one game to close out somebody else’s postseason, and that they did.

As a result, Elimination Day is in full effect…as if the bright sunshine casting a glow about the New York Metropolitan Area this lovely morning didn’t reveal that a festive annual occasion was underway. The Jays ousted the Yankees, 5-2, in the fourth and final game of their ALDS Wednesday night, and with that joyous piece of business taken care of, the playoffs can continue glorious and free without threat of a municipal nuisance parade. The current autumn included, New York has now avoided MNPs for 24 of the past 25 falls, so on this one very specific count, you’d have to say it’s been a pretty decent quarter-century.

Whatever we contributed to the Blue Jays’ cause by preparing them in April to return to town better equipped in October we were happy to provide. For that matter, we can be proud that we helped the Jays take flight on March 11, 1977, visiting Dunedin for Toronto’s very first Spring Training game. The Mets were thoughtful opponents that Friday afternoon, bowing to their new Florida Suncoast neighbors, 3-1. As you can imagine, the exhibition counted a lot more in the minds of the upstart expansioneers than it did for the blasé veteran assemblage that had bused over from St. Pete. For that one day, the head start on life the Mets enjoyed over the Blue Jays didn’t count at all.

Toronto GM Peter Bavasi: “How can a club two-and-a-half hours old beat an established club sixteen years old?”

Rookie Blue Jays first baseman Doug Ault: “We came out here today to win. We have a lot of young players here who are really hungry.”

Mets starting pitcher Jerry Koosman: “I’ve only heard of three guys on their team.”

The largely unknown Jays migrated to their regular season pretty much as expected, going 54-107 and finishing last. But they were on the major league map, even if they remained stuck in the AL East basement for a half-dozen seasons. They didn’t begin to peek out from down below until 1983, a year before Koosman’s old club — which had descended down the stairs itself in ’77 — emerged from a lengthy hibernation. By the mid-1980s, the forlorn Jays and Mets of yore had evolved into baseball powerhouses, and nobody asked to see their birth certificates. The Mets won a World Series in 1986. The Blue Jays won two, in 1992 and 1993. In between, we loaned them Mookie Wilson and Lee Mazzilli. After both franchises had sunk from contention, the Jays reciprocated by sending us John Olerud.

How it started. We’ve shared more than a little cross-pollination across the decades. Perhaps my favorite repository of Immaculate Grid arcana resides within the composition of the 1981 Toronto Blue Jays pitching staff. The Jays used fourteen pitchers in that strike-shortened season, and nearly half of them had been Mets:

Juan Berenguer

Mark Bomback

Nino Espinosa

Roy Lee Jackson

Dale Murray

Jackson Todd

Toronto’s decision to scoop up arms the Mets had given up on during this era might explain why the Jays took a while to become competitive, but the link between the franchises went back even further. Coaching Blue Jays pitchers during their very first Spring was none other than Original Met Bob L. Miller, the same Bob L. Miller who went 1-12 for us in 1962. “This has brought back old memories,” the Bob Miller who wasn’t the other Bob Miller told Joe Donnelly of Newsday. “Just walking around and seeing guys introduce themselves to each other reminds you what it was like.” Miller correctly predicted his 1977 Jays, despite their youth and relative anonymity, would exceed the victory total posted by the initial 40-120 Met edition, which boasted its share of recognizable names from seasons gone by, if not a lot left in their collective tank. “There are so many more ballclubs now,” Bob assessed. “The talent has to have thinned out.”

How it’s going. Forty-eight years later, there are four more ballclubs, and eight more teams make the playoffs than was the case in 1977. The Jays were one of them in 2025. They are the only one thus far to have guaranteed themselves a spot in the League Championship Series round. One of their positional mainstays is a former Met, Andrés Giménez, and two former Met pitchers, Max Scherzer and Chris Bassitt, helped them pluck a division title. A few other recent Mets wore Toronto garb in the course of the season, none of whom it’s likely Jerry Koosman has heard of, even if he’s paying close attention these days. The Jays have enough famous stars at the top of their game, and their next game will be the first of those that will determine whether they will appear in the upcoming World Series.

That’s a World Series that won’t take place in New York, which would have sounded like a bummer to us in early April, but today seems just fine.

by Greg Prince on 6 October 2025 5:56 pm The first week without Mets was predictably bumpy. The first week usually is, because life’s essential rhythm has been massively disrupted. There goes early evening’s certainty. There goes first pitch at 7:10. This year, there went the playoffs. Playoff time is already disruptive vis-à-vis established rhythms, because games start whenever TV says they start, and they’re not aired where you’re used to finding them, but you’ll accept the little differences in exchange for the gratification they bring. It’s the playoffs. It’s all about the little differences. October is the Royale with Cheese of baseball.

But these 2025 playoffs commenced sans Mets. Some Octobers that’s not even an adjustment. This didn’t start as one of those Octobers, not after the Mets hovered in a playoff spot for months on end, yet landed adjacent to the playoffs as afterthoughts rather than squarely in them as participants. All things being equal, you’d rather grind down to the 162nd game with a chance to go further than peter out well ahead of the end of the season — yet when you know for a while you’re not going anywhere, you can skip the part where you can’t believe you don’t have playoff baseball of your own on which to obsess, and just focus on not having any baseball of your own on which to obsess.

I’d see the brackets MLB and its broadcast partners posted on social media, and the Reds logo glared out at me from its little 6-seed corner. That’s where a Mets logo had been tacked to the virtual posterboard most of September. Why didn’t we use stickier tape to keep it attached? Honestly, being officially informed the Reds would be playing the Dodgers was a little insulting. You’re going to hold your party without us? Don’t you remember us being the life of your party last year?

Seasons change. Feelings change. Last year’s party was so much of a blast, I barely needed to be coaxed out the door when it was time for us to go. It did occur to me that it’s never good form to leave before making the most out of a postseason appearance, and maybe I should have more deeply regretted our expulsion following the NLCS, but who expected us to appear in the first place? We’d be back the next time they held one of these shindigs, we could tell ourselves by December of 2024, and we’d appear from first place.

Well, none of that happened. First place got away, and that last Wild Card got away, and I found myself peeking in on the Reds and Dodgers, the Dodgers immediately going about the kicking of the Reds’ asses, which made me feel both a little worse (“tell me we’d any less worthy an 83-win representative”) and a little better (“yeah, we probably weren’t going to beat L.A., anyway”). Soon enough, the playoff round the Mets weren’t quite unmediocre enough to qualify for was over, and the team that qualified ahead of them was out, too.

The League Division Series round — the one that still needs a better name — was on, and it still bugged me we weren’t involved. At least during Cincinnati’s short stay, ESPN’s announcers were obliged to mention the Reds were there because the Mets weren’t. One set later, we had faded further into the background. The Dodgers were still the Dodgers, and the Phillies were still the team that zipped past us by August. Anticipating Philadelphia’s first postseason game, I thought maybe seeing them still playing wouldn’t disgust me, for all the reasons I usually conceive for thinking I don’t innately hate the Phillies as much as I innately hate some other teams. Then I actually saw the Phillies, and I wondered what the hell I was thinking, because I really innately hate the sight of the Phlllies. I disdain the Dodgers, too, but they’re 3,000 miles away. The Phillies sit too close for rationalization.

Honestly, I don’t care for either of them (or very much for any National League team that gets to keep playing when we don’t), but on Saturday, when the Dodgers rallied from behind to stun Citizens Bank Park into delicious silence, I clapped not a little. Whatever happens the rest of the way, my anti-rooting interests in this quadrant of the postseason, the one the Mets would be in had they won one more stupid game, are clear.

Saturday evening was probably when the disappearance of the Mets resonated the deepest. I was preparing a turkey and avocado panini as I do virtually every Saturday evening, which from April through September usually means the Mets are on while I’m getting down to panini-ing. A lot of 4:10 starts at home, so the game is winding down by the time I’m messing around in the kitchen. Or maybe the Mets are on the road and just getting down to their own business. If they’re out west, I’m looking forward to whatever it is they’re about to do. This past Saturday evening, no Mets. The panini was satisfying, but it was missing something. I was missing something.

Sunday morning was different. I was out running a few errands and noticed somebody in a Mets shirt. I was wearing a Mets shirt, too. That other Mets fan was on a bike while I was driving my car, so he probably couldn’t see what I had on, and it didn’t seem worth the trouble of exchanging Let’s Go Metses, given that he needed to concentrate on his side of the road like I had to on mine. But I was thinking it was nice that although our shared team had gone down in fairly embarrassing fashion one week earlier, here we were, unashamed and unabashed in our clothing selection. There’ve been Octobers when I asked myself why the bleep I’m out repping this team of mine. Often it feels like courting grief, especially when another local team is still active. Three years ago, sometime after we were eliminated by San Diego, I had my Mets hoodie on and someone with whom I crossed paths offered me his LGM simpatico. I think my reaction was a polite version of “yeah, but they suck.”

That was 2022, which granted us postseason baseball, which was a blessing that morphed into a curse. When it was over, it wasn’t like 2024. I was one big walking recrimination that autumn, incapable of imagining I was going to dive soulfirst into another Mets season when Spring rolled around. Guess what happened: Spring rolled around and I rolled with it. Sometimes it defies belief you’re going to ramp up anew, but there you are, ramped and believing, having compartmentalized whatever made you miserable last fall.

Nice guys finish seventh on a tiebreaker. Pressure may be a privilege, but on the morning after the first games of the LDS round, out on those errands, I realized that if the Mets were in playoff mode, I totally would have tooted my horn at that bicyclist, and we’d have given each other the thumbs up rather than some other finger. Yet before I could begin to miss the Mets and miss the Mets being in the playoffs, I thought about that churning I get in my stomach when the Mets are immersed in postseason play, and I realized, to my surprise, that I didn’t miss that part of an orange-and-blue October at all. I’d gladly give my postseason acids over to a Mets team that deserved them. This one didn’t.

I continue on as a Mets fan, as we all do, even if they are irrevocably idle. I like being reminded I am a Mets fan. I put on that shirt voluntarily Sunday rather than stuffing it back in the drawer from whence it emerged. When I thought I was done unpacking my groceries a bit past noon, the trunk wasn’t slammed shut a second when I said, “I think I left one soda in there.” My wife responded, “Did you just say you left Juan Soto in there?”

“What would Juan Soto being doing in our trunk?”

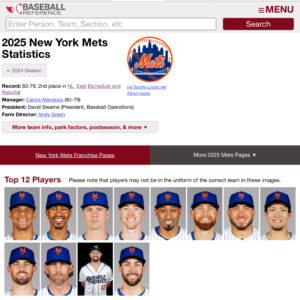

That exchange made me smile on contact. Being reminded the Mets still exist makes me smile in October when the only evidence we have of them are euphemistic personnel announcements and quick explainers from national voices who wish to clarify why exactly it’s the Reds who are getting stomped by the Dodgers. No game yesterday and no game today? Not ideal, but no antacids required. Sunday afternoon, I had the Giants losing to the Saints, with glimpses of the Jets losing to the Cowboys, and I was sports-sated if not particularly jubilant. Sunday night, I settled in with the Mariners and Tigers in the one ALDS I can bear to watch (I know the other one is going swimmingly, but my tuning into it strikes me as a no-win situation) and, for whatever reason, I looked something up on the 2025 Mets’ Baseball-Reference page. There they were again, in all their statistical glory or lack thereof, all of those 2025 Mets whose cause had been my cause for six months, right up to one week earlier. Not only the name-brand Mets who’ve bubbled up in my head during the past week, like One Soda, but the ones who had ceased occurring to me on a daily or hourly basis the way they do when I know there’s gonna be a 7:10 first pitch, or some final pitches as the panini hour beckons.

I skimmed their names, remembered how they performed, and I didn’t smile, not until I realized I was quite content to no longer be watching them or considering them in any kind of depth. I still love the institution, the entity, the overall progress I believe the franchise has made from where they were prior to current ownership, the genuine sense that things will sooner or later end in a less disappointing manner. But the 2025 Mets I had lately spent so much time dwelling on were now the 2025 Mets I was delighted to have moved on from. I didn’t hate any of the players whose names I skimmed, merely how they played as a unit. I will hope that can be corrected in 2026. The playoffs of the moment can be the playoffs in the Mets’ absence. Next year can be next year when the Mets are present, and I plan to be right there with them. This October, I can live just fine Metslessly.

Not that I have a choice on the Metslessness. It’s the coping that’s optional.

by Greg Prince on 4 October 2025 2:20 pm To paraphrase Henry Blake attempting to console Hawkeye Pierce in “Sometimes You Hear the Bullet,” the early episode of M*A*S*H in which Hawkeye grapples with the combat death of an old friend, there are certain rules about a baseball season that doesn’t meet its high expectations.

Rule number one is coaches get tossed aside.

Rule number two is you probably have no real idea whether those coaches deserve to get tossed aside.

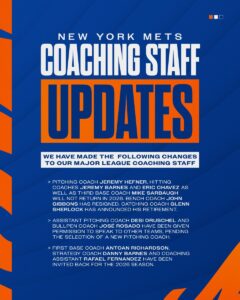

But aside they are tossed, nonetheless. Having concluded that a third year of Carlos Mendoza managing remains more promising than his second year of managing could be determined culpable for not meeting high expectations, David Stearns and whoever David Stearns takes counsel from decided something had to be done. Or somebody had to be done in.

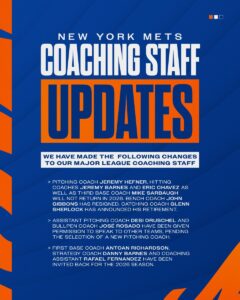

As postseason prepared to resume in eight MLB outposts, euphemism season was underway on Friday in Flushing, from whence it was communicated that four coaches “will not return in 2026”; one “has resigned”; one “has announced his retirement”; two “have been given permission to speak to other teams”; and three “have been invited back for the 2026 season”.

Euphemism season gets underway. My first reaction to so much staff deletion was, “The 2025 Mets, who repeatedly appeared to play as if they had not been coached on how to respond to myriad game situations, had eleven coaches?”

My second was, “I’m sorry for however many of those guys who were just doing what they’ve always done, and it worked in the past, but now it didn’t, and they likely didn’t get any less capable in the season that did not meet high expectations, but trying to make work anew what didn’t work just now probably wasn’t gonna work next year, so, y’know…good luck, fellas.”

A season like that which the entire Mets organization just executed until it had no life left in it calls into question whether anyone in or out of uniform who was tasked with helping the Mets win baseball games knew what they’re doing, and if they did, why didn’t they do it? Being a fan rather than a person for a moment, fine, get rid of pretty much everybody. Reasonable exceptions immediately start being made within such thinking, of course, but being reasonable is hardly a fan’s primary impulse when a fan is still mildly shocked (which is not to say at all surprised) that he is not looking forward to watching Game One of the NLDS with a tangible rooting interest.

The best argument for Mendoza — and maybe Stearns — to return is turnover fatigue. I know I’m tired of looking for new and brilliant leadership every two years. Also, they were the guys who guided us up the mountaintop a year ago. Did they suddenly get less capable? Could be. How do we know it wasn’t Mendy and Stearnsie who weren’t holding back the genius of Jeremy Hefner, Eric Chavez, Jeremy Barnes, and Mike Sarbaugh, the four coaches who were tagged with the “will not return” label? Maybe Glenn Sherlock needed to be talked out of retirement, and John Gibbons’s resignation should not have been accepted, and instead of providing permission to Desi Druschel and Jose Rosado to speak to other teams, they should be the ones to build the next brain trust around.

As is, three Met coaches — Antoan Richardson, Danny Barnes, and Rafael Fernandez — have been asked to maintain their positions. Thanks to the Mets’ lopsided base-stealing to caught-stealing ratio, particularly that of lethally efficient Juan Soto, we can safely infer Richardson is a baserunning instructor savant. If he wishes to fashion himself a Tom Emanski sideline and record a video in which he shares his secrets for getting from first to second, I don’t doubt Soto would endorse it at a discount. I have no idea what the other two guys do, but I’m willing to believe they’re filling their respective euphemistic roles (strategy coach and coaching assistant) professionally.

Most of Met pitching went down the tubes in 2025, so there went pitching coach Hefner, hailed perennially as really good at what he did until the results weren’t there. Chavez and J. Barnes had been deemed keepers before the collective lack of hitting when the Mets really needed some overwhelmed their accumulated goodwill and credentials. Sarbaugh waved many runners home successfully, stopped some others too soon. Sherlock’s catching wisdom got through to Francisco Alvarez and Luis Torrens often, if not always, assuming the catchers took their cues from their coach. Gibby was up on his feet and calling the video replay coordinator after every close play. The Mets won a lot of those challenges.

This is all very round and round. I watched games that got lost and went to bed implicitly unimpressed with the coaching, but not really pinning the losses on faulty instruction. Games that got won? Well, the Mets were supposed to win those games and more games besides. When the Ws flashed from the Citi Field light towers, I knew who got the big hit or strikeout. I didn’t dwell on what might have been suggested by who to get the most out of that critical swing or pitch. Coaches in baseball exist as our idealized umpires do. When you don’t think about them, they’re probably doing a decent job.

Next year, balls and strikes will be confirmed via computerization. Coaches, however, will continue to be nothing but people until further notice. I’ll usually feel bad for people who no longer have their jobs if I don’t have any solid reason to be happy they’ve been dismissed. I’d be happiest of all if Met coaching was still going on this month, whoever was doing it.

by Greg Prince on 29 September 2025 2:43 pm “This summer, the Mets suffered so many difficult, late defeats in close games that no one on the team, surely, could have escaped the chilling interior doubt — the doubt that kills — whispering that their courage and brilliance last summer had been an illusion all the time, had been nothing but luck.”

—Roger Angell, in the wake of the 1970 season

The New York Mets have achieved baseball’s state of intermediate grace, a slot within MLB’s postseason matrix, eleven times in their 64-year history. In every one of the seasons that followed, their subsequent won-lost record paled in comparison to that which merited celebration. On average, Mets teams in those years after won twelve fewer games than they did during the preceding years when champagne flowed at least once.

1969: 100-62

1970: 83-79

1973: 82-79

1974: 71-91

1986: 108-54

1987: 92-70

1988: 100-60

1989: 87-75

1999: 97-66

2000: 94-68

2000: 94-68

2001: 82-80

2006: 97-65

2007: 88-74

2015: 90-72

2016: 87-75

2016: 87-75

2017: 70-92

2022: 101-61

2023: 75-87

2024: 89-73

2025: 83-79

As you can see, not all falls from graces are created equal. A couple of times, the tumbles were modest and hardly mattered — twice the Mets returned to the playoffs in those years after; once they advanced further in those playoffs than they had the year before. This was when playoff spots were more accessible than they had been when the Mets first earned one, if not as accessible as they would become in the most recent season in which the Mets failed to grab one, the season that ended Sunday in Miami with a 4-0 loss to the Marlins.

In 2025, the Mets’ record was 83-79, six games off the pace of the 2024 Mets of increasingly sainted memory. Unlike 2000 and 2016, despite the availability of more postseason berths than ever, this presented a problem. Had the Mets gone 89-73 as they did a year earlier, they would have cruised into the 2025 playoffs. Had they won a single game more, they would have eked in, but that would have been fine, at least until an 84-78 Mets squad was eliminated in due order, because very few teams with so few wins get very far in a postseason. Yet it’s been known to happen, and we were willing to find out if it could again.

Had 83-79 qualified us, we would have taken that, too. It came damn close to doing so. The 83-79 record with which the Mets completed their business was the same as that which will be carried into the postseason by the Cincinnati Reds, a feisty bunch that backed into clinching, pushed giddily into their bubbly by the feistless Mets, ass over teakettle, despite their own last-day 4-2 loss at Milwaukee. The Reds, a couple of hot weeks in September notwithstanding, were no great shakes in 2025. Actually, they were the same shakes as the Mets, except along the way to shaking out with an identical 79 losses, they won the season series between them and us, and that represented the difference between getting to go on or having to go home. There was a time when a tiebreaking game would have been played to determine postseason entry, but that’s simply not done anymore. And, honestly, if we’re determining which 83-79 team deserves to not be a league’s sixth postseason entrant, maybe baseball’s powers that be shouldn’t sanction spending one more minute on it than necessary.

I seem to be obsessing on the won-lost record rather than the game that sealed it. Yes, the Mets played nine more futile innings on Sunday. Yes, it boiled down to one panicked inning of middle relief and one scorching bases-loaded line drive that landed in a glove. Yes, it was the Marlins, official doer-in of last-ditch Met playoff hopes, who did in last-ditch Met playoff hopes once again. Yes, it was the Marlins’ World Series, except unlike in 2003, I wasn’t pulling for them to beat New York.

Give the Marlins credit for coming to play the role of spoiler with zest. Give the Mets another demerit for barely showing up when everything was on the line. Or maybe the Mets played to the best of their 2025 ability, which is a frightening thought. Then again, we were just presented 162 games’ worth of evidence that the Mets weren’t able to get done the minimum that needed doing to get where it once seemed there was no way they weren’t going. Their ability as a unit apparently topped out at 83 wins and 79 losses.

If I may be Dana Carvey’s Grumpy Old Man character for a moment, in my day, our team didn’t play mediocre baseball for the vast majority of six months and still have a chance on the final day to be eligible to win the World Series unless somebody shouted in our face that we had to believe. If we were going to finish barely over .500, we’d simply give up before the last week of September and we liked it — we loved it!

Maybe we didn’t love it, but we lived with it. Flibbity-floo, I grew up rooting for Mets clubs that fell short of falling just short. The 1970 Mets, the first team I ever followed from the beginning of a season to its end, went 83-79. They made the bulk of September painful by discovering ways to lose to the eventual division champion Pirates and almost everybody else down the stretch, a stretch in which their chances expired four days before the season did. When their world title defense got them no higher than third place, I processed third place, even at seven years of age, as where they belonged. Finish first, keep playing. Finish third, keep walking.

Eighty-Three and Seventy-Nine locked in as the Mets trademark record in my mind a year later, 1971. At the last home game of this season, while my friend Ken was still ruing how September 1970 got away (gently ask him about Willie Montañez when he was a callup on the Phillies, I dare ya), I drifted to the next July. The 2025 Mets, as every schoolchild by now knows, started 45-24. Only the AP History classes probably mention that in 1971, the Mets sat in first place with a record of 45-29 on June 30. The next thing I remember — and I really do remember this — was the Mets went out and lost 20 of their next 27 games, exiting the NL East race as they spiraled. At 83-79, they finished tied for third, no tiebreaker of any kind applied to decide whether theirs was the best 83-79 record extant.

The Mets won 83 games in a 156-game strike-shortened season in 1972. It made for a better winning percentage than the previous two years, but proved irrelevant to the pennant race’s conclusion. The Mets won 82 games in 1973, the aberration of all aberrations in the four-division era. In 1975, the Mets won 82 games again, and they had a chance when September started, but by losing significantly more than they won after September 1, they transmitted to their loyalists that 82 wouldn’t be enough. The 86 wins of 1976 were stitched mainly from window dressing that materialized when the lone playoff spot on the table was too many seats up from where we’d positioned ourselves to stay by Memorial Day.

A slightly OK record, shorn of any given season’s context, was always a slightly OK record. You could be disappointed. You could be a rationalist. You could tell yourself next year would be the year we’d get back to where we were in 1969. You would be absolutely wrong about that last one throughout the 1970s, especially the late 1970s, but you recognized that a team that posted a record of or something like 83-79 was probably not going to be a playoff team, and if a team with a record like that did make the playoffs, you were entitled to use the word miracle like it was used in ’69.

That was all before Wild Cards existed. Wild Cards, from the mid-1990s on, have served roughly the same purpose the Mets did in 1962, per what the old Dodger Billy Loes said then upon his brief springtime dalliance with the expansion club:

“The Mets is a very good thing. They give everybody a job. Just like the WPA.”

In the modern baseball sense, the Wild Card makes every half-decent also-ran a potential contender while in the course of also-running. In the Wild Card era, prior to this season, the Mets had one 83-79 finisher, in 2005. That was the first year of this blog. We got our hopes up as August was becoming September, and we had our hopes quashed as the Wild Card we were seeking slipped from even theoretical reach. Still, it was a mostly fun year. The arrow was pointing up from the seasons before, and our next stop was first place in 2006. We didn’t necessarily know it was coming, but we could settle for finishing a little out of the race if we could be convinced better times were directly ahead. The 83-79 Mets of 2005 added Delgado, Wagner, and Lo Duca to Wright, Reyes, Beltran, and Martinez en route to becoming the 97-65 Mets of 2006. It was a very convincing transformation.

The 2025 Mets had something their 1970, 1971, and 2005 predecessors in 83-79 finishes didn’t. They had four shots to make the playoffs. They could win the division, or they could win one of three Wild Cards. Three! They drew none.

None!

Roger Angell wrote of the 1970 club, “Why the Mets failed to survive even this flabby test, falling seventeen games below their record of last year, is easy to explain, but hard to understand.”

Leonard Koppett wrote of the 1971 club, “You couldn’t fairly pinpoint any one fact, or one person” that would help explain or understand why a team that was once sixteen games over .500 landed only four above the break-even point, but he did lament, a couple of seasons later, “Everything considered, 1971 was probably the least satisfying year the Mets had ever experienced.”

Adam Rubin quoted Fred Wilpon on the subject of the 2005 club, “We had times where we were in similar positions in years past, and you didn’t see the same vibrancy on the field I think you do now. I think it’s progress. I’m not sure it’s success unless you are in the playoffs, and we’re not in the playoffs. So that part is a disappointment.”

These were all pretty measured, realistic responses to Met seasons whose records were slightly OK. Conversely, I’m not sure how to respond to this Met season with the very same record, this Met season that echoed the audible post-1969 sighs of 1970 and the post-June swoon of 1971. Despite maintaining the services of several extremely able players for the season and seasons ahead, I don’t sense palpable progress outside of the stuff flashed by a few very inexperienced pitchers, and after the way 2025 didn’t build off 2024, I’m not about to, at this instant, elevate my hopes for 2026. Although there is no more 2025 for the New York Mets, it’s too soon to tell myself next year will be the year we get back to where we were in any of those eleven years that extended into postseason. If I thought about it, I’d think they could, but I thought about it this year and thought they would, and I was dead wrong.

When the Mets won on Saturday via a 5-0 shutout and kept themselves alive for one more day, I did tell myself that no matter what happened Sunday, I’d be at peace with however it ended. I stopped telling myself that by Sunday morning, but it really was gratifying to watch the 2025 Mets one more time — for the 83rd and, as it turned out, final time — be the Mets we thought they’d be. The Mets who did have that Amazin’ start; the Mets who did fill their ballpark and elicit honest enthusiasm; the Mets who intermittently quelled our doubts. Those Mets didn’t show up for Game 162. It was fairly predictable, based on what the Mets had become, but it was still baseball season then, and during baseball season, we do like to imagine somebody is shouting in our face that we have to believe, even if it’s only an irrepressible inner voice we’re straining to hear.