The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 23 July 2022 9:46 am In 1969, 1973, 2000 and 2015, the Mets qualified for the postseason without the benefit of capturing their first game after the All-Star break, thus if you need a little precedent to take the edge off the first game the 2022 Mets played in five days leaving you wondering if they thought Friday night was actually an optional workout, there you have it. Even the uppermost of top-notch Mets teams don’t automatically bolt from the second gate of the season.

Most first games of the alleged second half suffer from a touch of sluggishness. A retrospective glance at wins by eventual Met playoff teams indicates units that weren’t quite ready to get back to work.

• After six innings on July 17, 1986, the Mets had rustled up nothing against Old Friend Nolan Ryan in the Astrodome and trailed, 1-0. Then Nolie had flashbacks to his younger self, got wild and walked the bases loaded with two out in the top of the seventh. A two-run single, some shoddy defense and relief pitching that wasn’t the caliber of 1969 Nolan Ryan followed, blowing both the doors and drawers off Houston’s attempt at a fast second-half start. By the ninth, Craig Reynolds was on the mound for the home team. Reynolds was usually a shortstop. The Mets bunched all their runs in the final three frames for a 13-2 victory. Three losses would follow that weekend, not to mention four arrests after a trip to Cooter’s.

• An 8-3 lead in the middle of the fourth at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium on July 14, 1988, became an 8-8 tie after eight. These were the days when the Braves could be found in the National League West, specifically its basement. Yet the Mets let the bane of their future existence ooze into extra innings alongside them (Old Friend Charlie Puleo threw four innings of shutout relief). In the eleventh, the Mets remembered they were a ton better than the Braves and pushed the winning run across to prevail, 9-8.

• Armondologists point to the second-half opener of 1999 as the first hint that not every lead would be safe in the hands of the new New York closer. The Mets were in St. Petersburg, which could have been considered akin to continuing their break. Visiting the Devil Rays of 1999, as was the case versus the Braves of 1988, was tantamount to a soft relaunch. No sweat, right? They were the Devil Rays. Sure enough, the Mets carried a 7-3 lead into the bottom of the eighth. Tampa Bay scratched out a run off Turk Wendell and Dennis Cook, but no worries. A three-run lead was about to be handed off to Armando Benitez, who’d been so good as John Franco’s setup man prior to Franco’s finger injury that it seemed inevitable he’d take over closing duties. Early results had confirmed that sense. What could possibly go wrong with Armando finishing off the Devil Rays? Only a one-out walk to future Met Miguel Cairo that preceded a double to Old Friend Aaron Ledesma and a rally that culminated in a game-tying single to Bubba Trammell, the next year’s playoff-berth insurance. Benitez got his three swinging strikeouts; he was good for a rate of nearly 15 Ks per nine innings. But it was the in-betweens that could kill him. In between striking out the side in the ninth inning on July 15, 1999, Benitez allowed three runs and the scored to be tied, 7-7. The preternaturally resilient Mets of that year grabbed the lead back in the top of the tenth, and Armando, with Bobby Valentine’s confidence unshaken, stuck around to quash the Devil Rays in order, “earning” his first win as a Met, 8-7. You were grateful for the W, but you started to wonder, just a little bit, if this hard thrower from Baltimore could be trusted in all tight situations. Cripes, he nearly blew a game to the Devil Rays.

• The 2006 Mets overcame a rare first-inning deficit and the opposition of a surefire Hall of Famer to keep their first-half ball rolling. Trailing the godawful Cubs, 2-1, and sitting Jose Reyes out of an abundance of caution, the Mets put four on the board in the top of the fourth versus forty-year-old Greg Maddux at Wrigley Field. Reyes’s substitute in the leadoff slot, Jose Valentin, produced three hits. Reyes’s substitute at shortstop, Chris Woodward, tripled. It became a 6-3 win on July 14, a Friday back when most teams returned to action on Thursday. Perhaps the extra day of rest did the first-place Mets good.

• The 2016 Mets restarted their engines with a familiar leadoff hitter at Citizens Bank Park. Familiar for 2006. Jose Reyes, off the Flushing grid since 2011, was back in a Mets uniform, though not back at shortstop. Jose was the Mets’ new third baseman in the July of his second coming. It was a long story, but the summation of it on July 15 was with Jose Reyes playing third and batting first, the Mets downed the Phillies, 5-3. They were up, 4-0, in the sixth until the Phillies — yet another marshmallow the baseball gods gave them to find their footing — chased Bartolo Colon. Reyes drove in an insurance run in the seventh, and Jeurys Familia, fresh from Terry Collins not using him nor any other Met in the All-Star Game (gads, that still irks me), made the ninth inning a non-event, notching his 32nd save of a season when he’d go on to total a team record 51.

The Mets are 5-4 coming out of the All-Star break in years when they’ve been on their way to the postseason. One is tempted to pencil that record in, with the dull-pointed writing implemented they’ll include with your overpriced program, as 5-5 after Friday night’s second-half opening loss to the Padres. Except no matter how secure the Mets’ positioning as a playoff club appears — yes, only a game-and-a-half up on the Braves, but also 8½ in the clear for a Wild Card should it come to that — nothing’s over until in it’s ink. The team that began the second half at Citi Field looked not enough like the team stormed through the first half. Maybe it was symbolic that the storm that was predicted to pass over the ballpark, despite necessitating a 31-minute rain delay before first pitch, never showed up.

Yu Darvish, unfortunately, was right on time. Yu Darvish has been stymieing the Mets in too many places on too many nights for too long. Darvish is 5-0 in eight career starts against us. He had recent precedent going for him, having shut out the Mets on two hits for seven innings in early June, but on this Friday night at Citi Field, he put me in mind of another Friday night at Citi Field. On August 4, 2017, Darvish had just become a Dodger and was making his L.A. debut versus the Mets. It amounted to a tuneup two months ahead of the playoffs. The righty went seven innings, scattered three singles and won one of the most uncompetitive games to which I ever listened on a southbound Metro-North train (or any conveyance), 6-0. This was 2017. The Mets were the 1988 Braves, the 1999 Devil Rays of their day. I was used to the idea that they weren’t gonna hit good pitching. I wasn’t prepared for just how much they weren’t gonna hit Darvish.

Five years later, the Mets are generally awesome, except when they’re not hitting, which isn’t confined to games started by five-time All-Stars. The Mets, first-place residence notwithstanding, can not hit with the best of them. Or the worst of them. On Friday night, they turned in a typical for them performance against this particular nemesis: in seven innings, they managed three singles, a double and a walk, amounting to an entire run off Darvish. That alone was a victory. It was the only victory, however, as the Padres otherwise pinned a 4-1 loss on them. This pitcher and this opponent might be bad news in the postseason.

The implicit good news in that statement is the Mets are still plenty on track for the tenth postseason appearance of their lives. Yet stepping it up is advised. On Friday night, a number of principals did their job not quite well enough. Max Scherzer was only slightly touchable — a two-run homer to Eternal Enemy Eric Hosmer in the fourth served as the differencemaker — but his eight strikeouts over six innings were destined to serve as footnote. Tomás Nido received credit for catching all eight Ks (including the ones that catapulted Max past Curt Schilling and Bob Gibson on the all-time strikeout chart), but he also caught a contusion on the wrist when he and his pitcher got caught in a crossup in the second. Nido wasn’t expecting the fastball that that ultimately left him unable to swing a bat, necessitating his sixth-inning departure in favor of Patrick Mazeika.

Mazeika’s presence came into play on what could have been a sweet double play to escape the seventh. With one out and the bases loaded, Nomar Mazara grounded to Pete Alonso. Alonso made a nice grab and throw to effect a force at home. Mazeika proceeded to relay back to first en route to a potential 3-2-3 DP, and he definitely threw in the direction of Alonso’s mitt. But Pete was set up at first in such a way that the batter, Nomar Mazara, presented a baserunning obstacle. Mazeika’s throw hit the runner, and not even Buck Showalter could argue Mazara was out of the baseline. The ball skittered away and instead of getting out of the inning, another run scored to make it Padres Too Many, Mets Not Enough.

At least J.C. Martin was still safe.

The one Met figure who did his job Friday without the results of his efforts being evident was GM Billy Eppler, who traded Colin Holderman to Pittsburgh for Daniel Vogelbach. Not too many months ago I couldn’t have told you who Colin Holderman was. He came up in May and, before and after a stint on the injured list, was dependable enough out of the bullpen to tantalize us with visions of increased responsibility. In a season when nobody among the Mays, Lugos and Smiths has really put a stranglehold on non-Ottavino/pre-Diaz setup duty, you could imagine Holderman taking care of business. He’d inherited eight runners as a Met. None of them scored — and those were the innings somebody else started.

Every few years the Mets let some promising young reliever go and you gulp a little at the repercussions. Usually it winds up inconsequential to the big Met picture. In previously referenced miserable 2017, for example, I thought Chasen Bradford looked pretty good. The Mets put him through waivers and the Mariners grabbed him. On Friday, hours before Eppler traded Holderman, Bradford tweeted his retirement from professional baseball, not having pitched in the majors since 2019. He leaves the pros with a 7-0 lifetime MLB record. Holderman is currently 4-0. As with Bradford, I don’t explicitly wish him any defeats. I also wish to avoid reliever regret.

Having buried the lede this long, let us finally excavate it: the Mets went out and got themselves a hitter, specifically a lefty bopper who might have come in handy Friday night had the trade been consummated Friday morning rather than Friday afternoon. Vogelbach mashes righthanded pitching. No Met mashes Yu Darvish, but recalling and starting Travis Blankenorn as DH, as the Mets did Friday, was a little too transparent admission of it. Vogelbach might make enough of an impact that, if there’s enough relief on the market to replace the surprising Holderman (Eppler says he thinks there is), will make this trade a job well done. The Mets have scads of accomplished hitters in their lineup. They’re just not accomplishing much of late. Something had to be done. This was one step. The production out of the designated hitter position, shared primarily by currently IL’d Dom Smith and J.D. Davis, has a person yearning for the return of pitchers hitting. This person has never stopped yearning for the return of pitchers hitting, but that’s another story. The story right now is Vogelbach will be here and others, whoever they are, should follow.

One might be Jacob deGrom, which seems worth mentioning, if not for how good a hitting pitcher he is/was. Ah, Jake. In the grand sweep of Mets acedom, dating back at least to the not always grand days of Swan and Zachry, we’re always waiting for somebody to come back from injury or worse. In Doc Gooden’s case, it was from “worse” once (though also from injury later). We checked our watches for the imminent return of Martinez, of Santana, of Harvey, of Syndergaard, of Scherzer for a while. DeGrom has been off our clock, and our innings have been filled so ably in his absence, that it was easy to almost forget the second-best pitcher in franchise history is still under contract and working his scapula off to get back to competition. During the All-Star Game, another National League loss you’ve already forgotten, the Mets casually announced Jake’s simulated game would be pushed back a couple of days due to mild muscle soreness in his right shoulder. Fan consensus had it that deGrom was missing at least one arm and would a) never be heard from again and b) opt out of lucrative contract and sign a more lucrative contract with some Georgia-based entity despite his career obviously being over. You can’t keep fans of a team in first place from a scenario that’s worst case.

It could be my sentimental side showing, but I believe Jacob deGrom will be with us again soon. Buck says he’ll have one more rehab start (he did do his simulated rounds on Thursday, without any incident reported) and then they’ll figure out what’s next. Buck doesn’t reveal what he doesn’t have to. Maybe that’s why he wears a windbreaker all the time. I’m assuming Jake isn’t giving it his all in Syracuse and St. Lucie and wherever just to let us down. I’ve missed him without being cognizant of it. With four days to mull the state of the Mets over the break, I was thinking how much I really, really like this team yet am a little shy of feeling passionate about them. I was passionate in 1999. I was passionate in 2006. I grew passionate in 2015. Ninety-four games into 2022, these Mets strike me as a beautiful band of brothers succeeding almost to my heart’s content, yet I don’t feel 100% connected. I’m pretty sure it’s the lack of No. 48 in my life. I’m grateful for Scherzer and all the other pitchers, but we had Jacob deGrom being Jacob deGrom for so long. Then we didn’t. Last year his absence was more of a Met-killer than Yu Darvish. This year it hasn’t been, except deep in my ace-loving soul. Of course Scherzer is an ace. Of course Scherzer is a Met. He’s been as Met as he can be. But I’m also cognizant he’s a Met because Steve Cohen paid him handsomely to assume the identity. There’s no cosplay at work with Max. He’s assumed his Metsian persona sincerely and professionally without a drop of Gl@v!nesque reluctance to take the money and stay. If Showalter always covers up with a windbreaker, Gl@v!ne never didn’t think you were watching a frigging Brave on undercover assignment.

Mind you, every professional baseball player is where he is because money is involved, and good for them. Yet it’s different when it’s the guy who you’ve known as yours his entire career. Scherzer is the greatest. But so is deGrom. And deGrom has always been ours, regardless that ultimately he will be his own man at opt-out time. That critical juncture, however, is a half-season plus (we remain confident) a postseason away. There’s a whole second half to go. There’s a veritable lifetime to come in these approaching games, weeks and months. There’s a torrent of passion bubbling so close to the surface that I can almost feel it.

So let’s get it on, let’s get going and Let’s Go Mets.

Maybe you’d remember the All-Star Game better had it been part of a cohesive All-Star Week, the kind proposed on the current episode of National League Town.

by Greg Prince on 18 July 2022 1:26 am 3 out of 4

2 out of 3

2 out of 3

3 out of 4

2 out of 3

2 out of 3

2 out of 3

My muscle memory still works. I still remember, even from the lofty heights of first place, how to be disgusted with my team as if it hasn’t been living in first place practically every night of this season. It didn’t matter to me at the close of business Sunday that my team was 23 games over .500 or 2½ games ahead of its closest competitor (a game better than it had been a week earlier) or as secure as could be in putting a deposit down on a playoff position well before postseason berths are officially issued.

My mostly wonderful team lost to the Cubs, 3-2, in one of those games that was there for the taking for nine innings but got given away or left on the table in most of them. Bleh! Bleah! Bleech! Whichever sound you choose, I was making it between 5:30 and 6:00. It was a game that shouldn’t have been lost, yet it was lost. There were approximately a hundred and twenty-three (rough estimate) flyouts into the wind. There was a dumb decision to attempt to score from second on a single into short left field made by the same runner who cleverly evaded a tag that led to a run hours earlier. There was an error of commission by the third baseman who must have invested in pork belly futures Saturday because he’d saved his club’s bacon twice. There was relief that wasn’t on the heels of so much relief that was. And there was the other team figuring out how to accomplish the feat I enjoy least in a matchup against my team: beating them.

The manager of my team is always reminding me, through the media, that the other team, whoever it happens to be on a given day, is capable of winning a baseball game. That message has been absorbed by his players who repeat its essence after infrequent instances of non-wins on their part. The worst element of this alibi is it is largely true. Nobody should ever beat the first-place Mets, but occasionally somebody does.

It happens because not even the 2022 Mets can win them all.

2 out of 4

2 out of 3

2 out of 3

1 out of 3

3 out of 4

2 out of 3

1 out of 3

3 out of 3

3 out of 3

I needed a half-hour to decompress from Cubs 3 Mets 2; to rationalize that bad days happen to good teams and vice-versa; to remember that although my worldview is often susceptible to the last thing it saw — Lindor getting thrown out at home; Escobar fumbling a double play grounder; Smith’s arsenal being turned back on him in the form of sharp grounders finding holes — overwhelming the larger or more significant sample sizes of the things that preceded it. This is not just a day-to-day instinct. These Mets have four All-Star selectees among them. Three were Mets in recent years. When recent years did not go swimmingly, I was willing to toss each of these recently certified stellar Mets overboard.

Not that I have that authority, nor do I have the attention span to construct hypothetical trades (not even for Juan Soto). But these past two winters, I swear I wasn’t attached with epoxy to anybody who couldn’t help the mopey Mets of 2020 and 2021 turn the corner of Roosevelt Avenue and Seaver Way in 2022. If I could have been convinced a transformation could have been achieved without the contributions of Messrs. Alonso, McNeil and Diaz, let’s just say it wouldn’t have taken a whole lot of convincing. And I wasn’t holding onto budding star starter David Peterson (5 IP, 0 ER Sunday) with both hands, either.

Glad nobody listened to what I was thinking. Glad somebody thought to hire a manager who knows what he’s doing, even when we’re left to wonder (Saturday night’s one-bullet bullpen roulette) what the hell he’s doing. Buck Showalter comes along after his tactics work, as they somehow did when he stuck with Yoan Lopez, or after they don’t, explains himself, moves on, and I nod. He tells us maybe not what we want to hear, but what we need to hear. I imagine he addresses his charges similarly. A bigger wonder than “why didn’t you have anybody warming up to replace the 27th man who allowed the tying run and put additional runners on base?” is why we were left to sift through deviants and amateurs as managers when this guy was out there just waiting for another dugout to fill.

I don’t have faith in Buck Showalter’s Mets. I have confidence. It’s a world of difference.

2 out of 4

1 out of 3

2 out of 3

2 out of 3

3 out of 4

0 out of 2

2 out of 3

0 out of 2

Crummy game Sunday. Aesthetically displeasing weekend. Where was that beautiful Wrigley Field to which we only get one exposure per season? Covered in clouds. It rained, it murked, it blew in. Whatever became of “a real Wrigley Field game,” one of those 12-10 jobs we’re conditioned to crave at the sight of Waveland Avenue? We got the other kind: 2-1; 4-3; 3-2. Yawn. I was hoping to depart the non-statistical first half on a high, not only sweeping the Cubs, but reveling in Wrigley for something beyond its cup-snake charmers. The Friendly Confines ain’t what they used to be. Then again, neither are the Cubs. I guess the latter is for the better.

We left behind the ivy taking three of four. We do a lot of that wherever we go, wherever we play. That’s how confidence is cultivated. The Mets won this series. They won the series before it, against a much more relevant rival in Atlanta. The Mets have played 29 series. They’ve lost five of them. They’ve tied three of them. They’ve won all the others. Rarely have they swept series, but they’ve methodically done all the taking they’ve needed to. Being methodical adds up. Boy, does it add up. The Mets’ record of 58-35 is their second-best ever after 93 games. It’s probably their second-best at the All-Star break, too, but since “the first half” is a malleable concept annually (the 1986 Mets played 84 games before the break; the 1999 Mets played 88 games; the 1980 Mets played 78 games), I’m not bothering to look it up.

2 out of 3

2 out of 3

2 out of 4

2 out of 3

3 out of 4

By six o’clock, I wasn’t any longer bothering to stress the Sunday loss to the Cubs. Susceptibility to the last thing I saw notwithstanding, it was easy enough to brush off. Rest up, fellas, I’d tell the players if they hadn’t already jetted to their vacation destinations. Tune up, I’d tell the front office (bullpen roulette can be chancy and another bat would be swell). Overall, everybody in orange and blue, keep doing what you’re doing in this year of years that thus far pales historically only in comparison to 1986. You’ve got my confidence. And my faith, in case you need it.

by Jason Fry on 17 July 2022 11:28 am None of that should have worked.

Presented to you is a short sentence in which “that” is carrying a heavy load, referring to two games played over more than nine hours, the first of them featuring an emphatically run-suppressing wind, and the Mets spending both games not so much stumbling as failing to deliver a knockout blow. And meanwhile the Cubs … well, let’s proceed delicately for now out of respect for a fellow fanbase’s bruised feelings.

The Mets should have lost the first game. Let’s start there.

In the bottom of the 10th, Nelson Velazquez was the Chicago ghost runner, substituting for Frank Schwindel. Velazquez promptly stole third against Adam Ottavino. Observing from first base was J.D. Davis, not anyone’s first choice to play that position (or honestly any position). Davis had entered the game in favor of Dom Smith, who’d rolled an ankle as the Mets’ ghost runner. (Seriously? Seriously.)

So there we were: The Cubs were 90 feet from victory with nobody out, Ottavino working a second inning and a Plan C or Plan D first baseman in the fray.

Ottavino started off Patrick Wisdom with a 2-0 count (ominous music intensifies) but struck him out on an evil slider just off the plate. He then fanned P.J. Higgins (seriously, who are these Cubs?) on three pitches that never prompted a bat to leave a shoulder. That brought speedy, capable rookie Christopher Morel to the plate. Ottavino left an 0-1 slider in the middle of the plate and Morel spanked it to the left of Eduardo Escobar at third.

Escobar speared it, but did so while stumbling in the dirt (oh my), scrambling on all fours for a moment (oh no) before finding his feet and firing the ball in the direction of Davis (oh God). The ball hit the dirt a few feet in front of Davis (oh Jeez) for a classic in-between hop. Davis lunged for it, glove coming up, and fell over like one of those parking-lot inflatables being removed from service. Fell over with the ball in his glove and Morel still short of first on his belly.

Somehow.

The Mets had survived, and then cashed a semi-deserved run behind a Francisco Lindor single and a Pete Alonso sacrifice fly, though they short-circuited their own inning when Lindor was thrown out trying to steal third with one out. With minimal margin for error, the Mets turned things over to Edwin Diaz just as your recapper and family drove deeper into a Maine peninsula where cell coverage is somewhere between spotty and a dream of the future.

We heard slices of events every 45 seconds or so, but they were the exact slices we would have picked: new hitter and ghost runner still on second, strikeout, grounder up the middle (another tough chance, as replay showed later), game over.

The Mets had no business winning that game, but they somehow did. Which was pretty much the capsule description of the nightcap, too — another extra-inning contest in which everything teetered on the avalanche point of going wrong but somehow didn’t.

In that one, Max Scherzer was more doughty trench fighter than vanquisher of foes, striking out 11 but allowing eight hits, with former National Yan Gomes leading the Chicago charge. The Mets fought back behind Escobar, whose numbers against Cubs starter Drew Smyly look like a misprint, but couldn’t break through against him or a resilient Chicago pen.

At least until the 10th, when they scored two runs on what Friend of Faith and Fear Dan Lewis accurately described as “the stupidest inning I’ve seen in my life”: infield single, stolen base, intentional walk, RBI HBP, GIDP, walk, run on ball heaved into center field, groundout.

(Minor observation before the sands of time obscure all: Mark Canha‘s GIDP was a case of a hitter doing exactly what he should do and being punished for it. Mychal Givens had just let the Mets score by ticking a ball off an elbow that Alonso had conspicuously refused to move aside, and was understandably agitated. Canha zeroed in on his first pitch and spanked it up the middle — right to Givens. It’s an unfair game.)

The Mets led by two runs, and during the bottom of the 10th the SNY cameras gave us a montage of Cubs fans watching a downtrodden tire fire of a team that was about to lose its ninth in a row, with what’s suddenly too much season still ahead of it — a striking succession of miniature pietas framed amid the suddenly gloomy confines of Wrigley Field.

But this day of unlikely baseball had a couple of twists left. The Mets were basically out of relievers, and so left Yoan Lopez — literally the 27th man courtesy of doubleheader rules — out there for a second inning of work, with no one behind him. Lopez struck out Velazquez, but severed his own net by allowing an RBI single to the pesky Morel, who then advanced to third on a single by Seiya Suzuki, leaving the Cubs 90 feet away from tying the game with the Mets essentially waving a bullpen white flag.

When Lopez’s next pitch was wide, Showalter opted to intentionally walk Nico Hoerner to have bring up Schwindel. Schwindel broke through last year as a 29-year-old, but as is so often the case, his post-breakthrough campaign has seen him look more like the journeyman he’s been than the late-to-ignite star he briefly seemed like he might be.

Nonetheless, Schwindel battled a tiring Lopez hard, refusing to chase bait sliders and smacking the close ones foul, until Lopez’s eighth pitch was — shades of Ottavino in Game 1 — one in the middle of the plate that he could handle. As in Game 1, this potentially fatal pitch went to Escobar — though this time it was to his right, a moderately tricky hop between him and the bag.

Escobar may not be a defensive wizard on Luis Guillorme‘s level (who is?), but his instincts are unerringly sound. He was already orienting his body towards third as his foot came down on third, and Schwindel is a lot slower than Morel. He was out by a good 15 feet as the ball thudded into Alonso’s glove, giving the Mets a doubleheader sweep and leaving Cubs fans wondering how two games that had been right there in their team’s grasp turned to dust just hours apart.

Bad seasons are like that — heck, we know all about them. And on the flip side of that cruel equation, seasons to remember have their own hallmarks — such as games you’re clearly destined to lose somehow winding up in your column.

Sometimes it even happens twice on the same day.

by Jason Fry on 14 July 2022 11:58 pm As a Met fan of a certain age, few things are as simple and satisfying as beating the Cubs by a healthy margin in a summer game at Wrigley Field.

I have nothing against Chicago — hell, I was just there and had a grand time. I love Wrigley Field’s essential simplicity, which still shines through more than a century of additions and supposed refinements. I’ve enjoyed talking baseball with Cubs fans in Wrigley’s seats and away from them. I’m not sent into a frothing rage by the mere existence of the Cubs, which happens when I spend too long considering the Yankees or the Marlins.

But still, they’re the Cubs.

I grew up on tales of the Cubs as our antagonists in the summer of 1969 — the black cat, Ron Santo clicking his heels, Leo Durocher shooting his mouth off, Randy Hundley‘s disbelieving leap, and all the rest. I was a babe in arms that summer, but I consumed the stories so many times as a child that pretty soon I knew them by heart. As a kid the Cubs were the team I hated in the NL East — and oh, how it stung when the Mets emerged from their years as baseball’s North Korea in 1984 only to have the Cubs throw them off the mountaintop at summer’s end.

All that’s long gone now — when I explained to my kid that I hate the Cubs and Cardinals and have to reminded to get worked up about the Braves, he was understandably nonplussed. I suppose childhood trauma leaves a mark deeper than anything that Bobby Cox or Chipper Jones could inflict on tougher adult skin. (Let’s agree to ignore the fact that Atlanta being in the NL West while Chicago and St. Louis were in the NL East never made a lick of sense.)

The Cubs are now in the Central and have dwindled into a curiosity, but when I see the Mets in road grays at Wrigley, with the fans right on top of them like spectators at a gladiatorial exhibition, my heart starts thumping just like it did when I was seven. And on summer nights when the Mets start ripping line drives into the ivy and depositing them into that quaint-looking basket, my heart grows at least seven sizes bigger.

The Mets did all of that Thursday night in what had been muttered about as a trap series after taking two of three in Atlanta but sure didn’t start that way. They strafed poor Keegan Thompson and vague relation Mark Leiter Jr., while Carlos Carrasco baffled the Chicago hitters en route to winning his 10th game of the year. I admit most of this year’s Cubs could be winners of a fan contest for all I recognized them, but that doesn’t matter — they’re still Cubs and that’s enough to leave my teeth bared and make me bay for their speedy demise.

(Can we note, by the way, that Carrasco is 10-4? Or that the Mets are now a season-high 22 games over .500? For all our screaming that the sky is falling, it seems to be up there intact and in fact quite a bit higher above our heads than we might have guessed.)

Anyway, the Mets beat the Cubs in pretty much every aspect of a baseball game and I enjoyed it thoroughly, though we’ll give the home team a point for the cup-snake tradition, spied upon by a bemused Gary and Ron and explored in Steve Gelbs’s wonderful interview with a young man named Jake. Jake was pretty much a certain slice of Chicago transmuted into human form: sweetly mindful of his family, dogged in pursuit of a questionable goal, well-served in a beverage capacity, not entirely factually engaged, and somehow completely charming. (Jake thought it was the eighth inning; gently informed by Gelbs that it was the seventh, he smoothly issued this blithe non-correction: “Basically the eighth, Steve.”)

It’s a great town. Doesn’t mean I want to beat its National League team any less. It’s been that way since I was seven and it’ll be that way when I’m 77.

by Greg Prince on 13 July 2022 5:19 pm I’ll take two wins in three games, even if the price is one loss in the middle. Not that that’s how series of baseball games work, exactly, but that is how the Mets-Braves to-do went down. We won Monday. They won Tuesday. We won Wednesday. That’s math as good as it gets when you don’t sweep.

Such simplicity in viewing the world of the National League East through this prism…it’s very relaxing. The Mets were in first place when they arrived in Atlanta; they’re still in first place; they’re in first place by a little more than they were 48 hours earlier. It’s a good three days’ work. It’s not a definitive statement. It may not even be a statement. It may just be three games. Better to have captured more of them rather than drop a majority of an admittedly small sample size.

The strong starting pitching that has been the club’s trademark since at least last week continued on through the finale at Truist Park. Chris Bassitt was mostly impenetrable for six innings. By the time he gave up a solo home run to Chipper Olson, the Mets had five on the board. The rotation is five starters deep at the moment. It’s a good moment to be in.

Whereas Met power has mostly flickered of late, it returned all bulbs flashing Wednesday. If you couldn’t for one day embrace Luis Guillorme batting cleanup, you have no soul (besides, he hit the Mets’ previous home run, on Monday night). Luis’s slump seems to be closing up along with the cut on his hand that none of us knew about because the Mets are pretty good about minimizing excuses. He didn’t homer off Charlie Morton on Wednesday, but his presence in the four-hole seemed to inspire several of his teammates. That’s my story and I’m sticking to it.

Eduardo Escobar made like a groundhog and saw his power stroke’s shadow in the second. Francisco Lindor drove in runs the way the most productive RBI shortstop in the majors should (three-run shot). Mark Canha made like an orange and blue green giant and opened his own Canha taters. The power trio, accounting for the five runs that amply supported Bassitt, dined out on what Morton served up and nobody here protested. Later came Luis doubling home a sixth run and Lindor scoring on a balk, all of it in service to the eventual 7-3 victory.

Seven runs. Plenty for Bassitt plus Drew Smith (2 IP) and Tommy Hunter (1 IP). Granted, each reliever, like the starter, gave up a solo homer. The Braves are gonna go deep. They went deep off Scherzer and Peterson, too. Nice to see nobody on base when they did. Hunter was mopping up. As for Smith, I had a dream that he sent my wife and me a note of apology on a folded, horizontal, cream-colored card for having given up a two-run homer. He also included a drawing of some sort that I don’t remember. Isn’t it enough that I remember the color of the notecard?

Anyway, Smith giving up a solo home run with a large lead doesn’t concern me. The other Smith on the team, Dom, never homering is a more of an issue in my consciousness. I grew curious enough to search via Baseball-Reference’s Stathead tool to see where Dom Smith’s homerless drought ranks within franchise annals. Now that it’s reached 103 games (that’s games with one or more plate appearance(s) and no home runs hit), it is the 45th-longest in the 61-season history of the New York Mets; Luis Guillorme’s longest homerless streak was 89 games…broken on the day in 2021 that Smith last sent a baseball over a fence. Mind you, almost everybody ahead of Dom on this list is either a middle infielder who was in there every day for his glove — Buddy Harrelson holds the record, with 299 consecutive homerless games, and has six streaks of more than 100 homerless games — or an aging pinch-hitter or a backup catcher who played once or twice a week or a then-youngster still developing into an occasional home threat or a singles hitter you forgot didn’t hit many home runs.

There’s one genuine outlier. John Stearns went nearly 200 games without homering between 1979 and 1981, making his third All-Star team in between regardless. Stearns hit 46 home runs as a Met. His drought ended with a bang (he beat Steve Carlton on a night when Carlton struck out 15, an echo of Ron Swoboda a dozen years earlier). Dom Smith has hit 46 home runs as a Met. He wasn’t exactly a classic slugger when going yard wasn’t a novelty for him, but you didn’t find yourself counting games between his home runs. Dom nowadays usually plays a position that contains “hitter” in the title, so it’s more than a little concerning he’s neither hitting (.198) nor slugging (.294). On Wednesday, he came to bat four times. He walked once (.280 OBP). He didn’t homer (and hasn’t since July 21 of last year). Let’s hope Wrigley Field shakes the clout out of him.

Or, if it doesn’t, maybe somebody else will pick him up (and I don’t mean on waivers, wise guy). Twenty-six players compose the active roster. The Mets have won two out of three and 55 of 89 by getting something out of just about all of them when they really needed it. Keep that math going.

With the All-Star Game fast approaching, it’s time to remember how to root for players representing teams we usually can’t stand, because for one night those players will be teammates of Mets players we really do like. This week, then, join National League Town in a spasm of National League Solidarity. Warning: nice things will be said about opponents.

by Jason Fry on 12 July 2022 10:58 pm Well, if you want to view the glass as an eighth full, I suppose Seth Lugo solved the Mets’ bullpen-availability problem.

A night after watching Max Scherzer do maximum damage to the Braves, the Mets turned to David Peterson, who wasn’t nearly as flashy as his ace counterpart but was pretty damn good, ping-ponging between his fastball and his slider and leaving Atlanta off-balance and out of kilter. But Peterson’s pitch count was climbing, as it so often does, and a hard-earned 1-0 lead was looking even skinnier than that skinny vertical number would indicate as he tried to get through the fifth with a pitch count that neared 100 and then went over it.

Peterson was out there because the Mets had a bullpen problem looming ahead of them: no Edwin Diaz after being used three days in a row, and if sartorial clues count most likely no Adam Ottavino either. Which left … well, who, exactly? Drew Smith, whose early successes have been followed by too many failures? Seth Lugo, who’s become serially unreliable? Colin Holderman, who’s been good but one fears is living on borrowed time? Tommy Hunter, a likeable stalwart but one whose mileage and track record don’t inspire confidence?

No, Buck Showalter counted up the outs left to get and gambled that a tired Peterson was a better bet to reduce that number than turning to someone else and setting those tired-reliever dominoes falling.

Peterson didn’t get a lot of help when home-plate ump Andy Fletcher ruled strike three on Dansby Swanson was somehow a ball. (Before you rush to the barricades, Fletcher was at least consistently inconsistent, ringing up various other Braves on balls that didn’t look like strikes.) It looked like Peterson had escaped when Matt Olson clubbed a ball down the right-field line that somehow went just foul, but in fact the inevitable had merely been delayed. Olson got a pitch as much to his liking if not more so and smashed this one into a tree behind center field, its flight measured from the ground by a forlorn Brandon Nimmo.

Y’know what? I enjoyed that trick far more when Cliff Floyd was the one performing it.

That was Peterson’s last pitch; he departed down 2-1 and handed the ball off to Lugo, who was good for one inning and bad for another and so let the game get out of reach.

One game blah blah blah blah etc. etc. etc., but the Mets have a bullpen problem. There are exactly two reliable guys out there, with a bunch of journeymen who make you flinch and youngsters you fear are overdue to turn back into pumpkins. And somehow the thought of Trevor May riding to the rescue doesn’t make me feel like everything will be OK.

The Mets have a bullpen problem. I sure hope they solve it, because this team’s been a lot of fun to watch and I’d like to watch them for a chunk of the fall that in recent years has been open for other forms of entertainment.

But hey, while it may not be a solution, at least the two trustworthy guys should be rested for Wednesday afternoon.

by Greg Prince on 12 July 2022 11:31 am The story before Monday night’s game in Atlanta was discerning what the hell Robinson Cano was doing in a Braves uniform, in the Braves lineup, in the Braves infield. Wasn’t Robinson Cano, having washed out with the San Diego Padres, an El Paso Chihuahua literally the day before? Did the surging Atlanta Braves really need Robinson Cano of all people? They may have had a void at second base with the injury to Ozzie Albies, but that wasn’t new. Suddenly they needed Cano?

Would it have anything to do with the presence in Atlanta of the Braves’ rival for first place, the New York Mets? The same New York Mets who released Robinson Cano months ago? The same New York Mets who were paying the bulk of Cano’s massive salary regardless of who he played for, and now it would be the Braves? Was this supposed to be a psyche-out à la Felix Unger donning a second, albeit rubber, head and Oscar Madison draping himself in a Billie Jean King poster when they played Bobby Riggs in table tennis? The meticulously planned ping-pong mind game didn’t work on The Odd Couple, as Riggs was at the peak of his hustling. Would waving erstwhile Met mentor and MLB suspendee Robinson Cano in front of the team they were scheming to catch make a difference in the Met-Brave dynamic?

“And then we’ll bring Robinson Cano in to REALLY psyche them out!” Well, Cano played second base very well and garnered a couple of hits in his Brave debut. But it couldn’t be said he made much of a difference in the course of Monday night’s game, because the Mets are also paying Max Scherzer’s salary, and Max Scherzer is still a Met.

Boy is he ever. Forgive the surprise. When Scherzer was fit as a future Hall of Fame fiddle in April and the first half of May, he was top of rotation and top of mind. Then he had the oblique issue that eased him out of direct view, and I kind of forgot we had him. Kind of. I knew he was working his way back — devouring his way back, I imagined, because “working” is probably an understatement — but we were focused on the games at hand. Max would understand. When he focuses on the game at hand, he burns a hole through it.

No chance I’m gonna forget Max Scherzer’s a Met for the rest of this season. I’ll pinch myself now and then, but I won’t forget. A game like Monday’s, with the starting pitcher at the heart of the matter, is the kind you plan to remember, especially in the course of a year with which you plan to do the same. Cano? Curious sidebar. Scherzer?

He was the story. He was the reason whatever odds whichever gambling sponsor flashed on the screen had to favor the Mets, regardless that the Braves have been hotter than Georgia in July, regardless that the Mets appeared prepared to support their co-ace like they supported him last week in Cincinnati and like they’ve supported their other co-ace too often in his brilliant career. Ya think Max Scherzer texted Jacob deGrom after the Mets didn’t score for him in his return start (6 IP, 2 H, 0 BB, 11 SO, 0 R) and ask how to handle such offensive indifference? Or ya think Scherzer sucked it up and figured out how to will the Mets toward a win as much as he could against the Braves?

Ya know what I think or can least infer it from the tone of awe in this essay. I know the pitcher can only do so much, especially since he can no longer grab a bat and drive in a few runs the way deGrom would. But, oh man, Max Scherzer on the mound for your team in what you’re trying to keep from being a battle for first place…that’s a psyche-out. Not that the Braves didn’t bring a formidable Max of their own to bear. Max Fried ain’t easy pickins. We’ve seen that enough through the years. The Mets did pick at Fried’s offerings. Got a guy on base in the first. No runs. Got two guys on base in the second. No runs. Put a run on the board in the third — then another! Two runs! Oh wow! Bust this thing open, boys!

Nah, the Mets weren’t gonna do that. Even if Fried didn’t have the sharpest command, he wriggled out of the fourth and the fifth before departing with an accelerated pitch count. The Mets, minus Jeff McNeil on paternity leave and Starling Marte in day-to-day groin purgatory, left ten runners on base in all and went only 2-for-10 with runners in scoring position. It was better than what they produced in the 1-0 loss to the lowly Reds, but you wouldn’t presume to find it sufficient to beat the defending world champion Braves.

Except once they gave Scherzer the two runs, it was plenty. The only Brave to barely bother Max until the seventh was Cano, with a single Luis Guillorme couldn’t smother (maybe, per Felix Unger’s scheming, he was seeing double). In the seventh, with two out, we were reminded that the Braves are the Braves, as Austin Riley, one of several überBraves, lined a ball high over the left field fence. The only thing that hit harder than Riley’s bat was the disgust on Scherzer’s face. After giving up a two-bagger to the next batter, Marcell Ozuna, I wondered if Max would call timeout, beat the concrete out of the dugout wall, and then come back feeling all better. Maybe in his head. On the mound, he simply struck out Eddie Rosario to end his night at 7 IP, 3 H, 0 BB, 9 SO, 1 R.

While Scherzer was dealing, I remembered Buck Showalter spinning Max’s and Jake’s absences through the bright-side prism, predicting that getting each of them back in the vicinity of the All-Star break would be akin to making a couple of really big trades before the deadline. We’ve all heard GMs resort to this last bastion of inactivity when no swaps were on the horizon. We’ve all invoked it sarcastically when we’ve seen nothing cooking on the transactional horizon. Dillon Gee coming off the DL will be like making a trade for another starter. Yet I took Showalter’s remarks in good faith. They occurred to me Monday night as having proven true, mostly because Max had been so off the immediate-concern radar for a month-and-a-half and now suddenly he was pitching for the Mets…Max Scherzer pitching for the Mets. This really was like picking up an ace before the deadline. Knock wood, it will be like picking up an ace every five days for the rest of the year.

DeGrom is still in rehab mode. Not that we’re exactly suffering starting pitching shorts, but you really wouldn’t mind enhancing your rotation with the pitcher we’ve considered the best in the business since 2018. I still consider Jacob the best in the business, even if his store has had a CLOSED sign hanging from the door for a year, though after these last two Max starts, I have to take this co-ace stuff seriously. No way anybody’s been better than Jake as he’s scaled his Apex Mountain, but no way anybody’s better than the Max we’ve had these two sumptuous spoonfuls of. They’re two of a kind, no matter how different in temperament, repertoire, approach, and anything else. Details, details. They’re both the best in the business. Scherzer’s fire sets off smoke alarms. DeGrom is an ice sculpture. Yet I have the sense that if Jacob deGrom were a vintage Warner Bros. cartoon, we’d have a few frames zooming in on his head or heart or guts, and we’d see a miniature Max Scherzer inside him, going wild.

Except around the plate, because neither of them walks many batters.

Say, for all the thrills over what Scherzer did by himself and what Scherzer and deGrom might do in tandem, we’re still talking about a slim 2-1 Met lead heading to the eighth. If Max was done after 93 pitches, getting an extra run would be ideal. And as that thought bubble formed over my head (as if it hasn’t been floating there for days), Luis Guillorme took Darren O’Day over the right field fence. Not O’Day himself, but one of his pitches. Same difference. A Luis Guillorme home run! It certainly made up for not smothering Cano’s single earlier. And it definitely allowed for easier breathing as the evening’s setup man du nuit, Adam Ottavino, came in for the bottom of the eighth. He couldn’t be Scherzer. He just had to not give up two runs. He gave up none.

In the ninth, the Mets cobbled together an extra insurance run and Edwin Diaz — the sidebar to the Robinson Cano story upon the trade of both former Mariners to New York — was more than cushioned. Sugar was pouring for the third straight day. Yet he’d been so efficient in his two previous games, even as he was striking out basically every Marlin in sight, he was fresh to go. In the least surprising development of the game, Edwin Diaz struck out the opposition in order, using all of eleven pitches to seal the 4-1 win. Doesn’t matter that it was the Braves rather than the Marlins. Edwin Diaz in 2022 blows away opposing hitters, not save opportunities.

After Sunday, the sky was palpably descending if not altogether falling. On Monday, we had Max Scherzer for seven innings, reliable relief for the eighth, Edwin Diaz for the ninth and four runs to back up our three pitchers. The sky, like our lead in the East, rose accordingly. I don’t know if it’s the limit. I do know the Braves can have Robinson Cano.

by Greg Prince on 11 July 2022 12:07 pm So maybe it won’t be a runaway, a rout, a ravaging of the National League East. Maybe things are about to get real. Real challenging. The Mets are in Atlanta for the next three games. The Mets are also on top of Atlanta by a game-and-a-half, which looks precarious from any angle, especially from the perspective of the dawn of June, when the Mets led the division by double-digits. One of those digits was a decent bet to fall away, though I’ll confess I was getting used to the idea of 10½ as a baseline. You don’t get too many summers like that. I was hoping this would be the third of my lifetime. Oh well.

I was also hoping for three out of four from the Marlins this past weekend, Sandy Alcantra notwithstanding. The Mets didn’t lose to Alcantra on Sunday, but they didn’t beat him, either. The same can be said of the Marlins’ relationship to Taijuan Walker, who’s pitched like an All-Star, regardless of National League selection machinations. It was a scoreless duel for seven, for eight, for nine. After that it was a crapshoot, especially with Don Mattingly being able to place his loaded die, Billy Hamilton, on second to start the tenth. Hamilton got to second the best way he knows how — by pinch-running for an unearned runner — and got home the best way he knows how — by running on Tómas Nido. If Hamilton were attempting to steal left field, Nido would’ve had him cold. Instead, Hamilton stole third and scampered in to score as the ball Nido flung wondered what it was doing amid all that green grass.

The Marlins built another run off Tommy Hunter, into whose hands a tenth inning wouldn’t ideally land, and it was 2-0 going to the Mets’ potential last licks. We got the same Manfred man on second but couldn’t do anything useful with him off Tanner Scott. Sometimes the Marlins provide the most generous of gifts (on Keith Hernandez Day, no less), sometimes the Marlins swipe a win when nobody’s looking. They wouldn’t be Marlins if they didn’t poach one now and then.

So much for the Miami Marlins. So much, to a point, for everything and everybody up ’til now. The 53-33 record counts. The lead that’s not as big as it used to be, though it’s still a lead, absolutely counts. The Mets haven’t played badly from June 2 forward (18-16). They just haven’t performed up to their previous standards (35-17 through June 1). But for now, it’s Atlanta Braves time and the beginning of a series in which we, like they, are 0-0. We’ve played ’em four times in 2022, but those games, in early May, are no more than vaguely recalled here in July. The Mets and Braves split at Citi Field that first week of May then diverged for the rest of the month. That’s how we got to June 1 with the enormous advantage that’s slowly if not fully evaporated. As I understand it, the Braves held a clubhouse meeting and more or less haven’t lost since. Who knew it was that simple? I listened to the last couple of innings of their game Sunday versus the hapless Nationals, also extras. Just as I knew the Mets wouldn’t lose to Washington the last series they played, I knew the Braves wouldn’t lose to them, either. And they didn’t. That’s how our lead receded to 1½. I realize tiebreakers will no longer be employed in case playoff spots and postseason seeds are deadlocked, but perhaps in the spirit of the free runner, the Mets and Braves should just settle the division by alternating innings against the Nationals. Whoever leaves the Nats looking more ragged is awarded the crown.

Instead, we get three games this week in Atlanta, five versus the Braves at Citi Field a few weeks later, three more in Atlanta in the middle of August, and the season’s penultimate series at Truist Park as September becomes October. Perhaps that last set will be an afterthought, though the context of how the afterthinking goes is to be determined. Will we have shaken off the Braves? Will the Braves have overcome us? Will the surfeit of Wild Cards — 3 Count ’Em 3!!! — be somebody’s salvation? Whither the not-dead Phillies?

This is why they play the games. This is why winning the games against the Marlins is always a better idea than the alternative.

***When the Mets take the field in Cobb County, their All-Star second baseman/third baseman/outfielder Jeff McNeil won’t be taking Brave aim alongside his fellow Met All-Stars first baseman Pete Alonso, right fielder Starling Marte and closer Edwin Diaz (of course Marte is day-to-day and it would be surprising if Diaz is available after pitching and excelling in two consecutive ninths). Jeff will be off on paternity leave, which will happen when families don’t plan around the baseball calendar. Buck Showalter gave the event his blessing on Saturday — not that he needed to. “I’m sure nine months ago they didn’t look at the schedule,” Buck said before Saturday’s game. “I hope not. This is something a lot bigger than baseball.”

When Buck addressed the question about McNeil’s pending absence while Keith Hernandez waited in the wings to address the media before his number was to be retired, it got me contemplating the life-goes-on of it all. Here we were reflecting en masse on the career of an era-defining Met, but there was still a game to play that day; there was a baby about to born to one of the players; and, a few minutes before Keith’s ceremonies were about to begin, I learned of a Met who had very recently passed away.

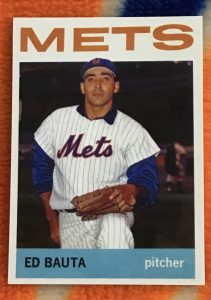

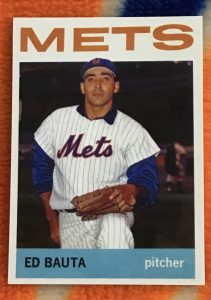

Ed Bauta pitched for the Mets in 1963 and 1964. You could say he was the quintessential transitional figure in New York baseball history. Only one man pitched in the final game at the Polo Grounds (1911-1963) and the first game at Shea Stadium (1964-2008). That’s Bauta’s claim to Met fame, and it’s a pretty good one. Only Brian Stokes and Pedro Feliciano could have identified with Bauta’s experience of what it was like to pitch consecutive genuine home games for the Mets in New York and do it in two completely different ballparks. Stokes and the late Feliciano helped finish off Shea in 2008 and open up Citi in 2009.

The pitcher who bridged ballparks. But only Bauta can say that in between his appearances in landmark games, he got a little extra action in one of the venues, for Ed also pitched in the last last game at the Polo Grounds, the cult classic Latino All-Star Game held October 12, 1963, matching National Leaguers and American Leaguers representing eight different nations and raising money for retired Latin players and the purchase of youth baseball equipment. Bauta threw the final pitch in the NL’s 5-2 win. Also participating that day were future Hall of Famers Roberto Clemente, Orlando Cepeda, Minnie Miñoso, Juan Marichal and Tony Oliva, with Tito Puente making a non-playing appearance.

Not bad company to keep.

In the years following the Polo Grounds’ demise, Bauta’s bridging was likely forgotten by all but the most hardcore of Mets fans of his day and, as the decades went by, went mostly unknown to future generations. I will admit that before Saturday, my awareness regarding Ed Bauta amounted to his having pitched in Shea’s debut (and knowing that it didn’t go well). I was also pretty sure that he wasn’t a big acolyte of Casey Stengel, but as I began to read up on him, I realized I was thinking of disgruntled first baseman Ed Bouchee.

No, Ed Bauta liked Casey plenty. According to Ed’s SABR biography, “I adored Casey Stengel,” who, by the Cuban-born righty’s reckoning, knew more about the game “than anyone else in baseball”. Ed was grateful for his manager’s attention, particularly on team flights. “Sometimes on the plane,” Bauta recalled for Thomas Van Hyning, “he was drinking vodka and spoke to me.” As cherished a memory as such an encounter might have been, one gets the feeling Bauta would have preferred consistent calls from the dugout to the bullpen. More than fifty years later, the reliever — who persevered despite not having many Spanish-speaking companions on the Mets — maintained he should have been used as a starter by Stengel and, if he was gonna be in the bullpen, he shouldn’t have been warmed up so frequently only to be used so infrequently. In some sense, the relief pitcher’s lot hasn’t changed much.

Bauta’s numbers as a Met may not have won him a ton of work out of the pen, but his seventeen-game tenure across two seasons was only a small part of his baseball story. He made his bones in the Cuban Winter League prior to the Fidel Castro regime, was pitching in the Pirates’ system as early as 1956 and was still plying his craft as late as 1974 in Mexico when he was closing in on 40. Though the ’64 Mets account for the final line of his major league ledger, the former Cardinal kept working to make it back, competing every winter in warmer climes and hurling in Buffalo, Williamsport and Jacksonville between 1964 and 1967. Examine some of those rosters and do a double-take: Gary Gentry, Jim McAndrew, Jon Matlack…and Ed Bauta. His career lasted long enough to cross minor and winter league paths with the likes of Bill Buckner, Mike Schmidt and a teenaged Gary Carter.

Baseball went on for a good, long while with Ed Bauta. Ed Bauta went on for a good, long while without baseball, save for kindly responding to mail from the occasional Mets fan seeking his autograph. Based on the interviews I’ve read with him since learning of his July 6 death, he gave the impression of somebody who lived to 87 happily enough ever after. There is indeed life without looking at the schedule.

by Greg Prince on 10 July 2022 11:18 am The temperature was in the 80s. The energy was out of the ’80s. I needed neither a weatherman nor a meter reader to know which way the wind was blowing or how much the juice was flowing. It didn’t take a meteorology degree to discern it was a warm summer day. You didn’t have to be Frank Cashen to understand the impact of putting together a winner.

The Mets of the middle of the 1980s never leave us. I don’t mean the players themselves, though it’s great so many occasionally come around and a couple have stayed around. I mean the feeling of what it meant to root for this team when we shook off failure and stepped right up to greet success. It explains why so many had descended on Citi Field on Saturday afternoon. Keith Hernandez and the Mets of the 1980s instilled an inextinguishable fire in Mets fans. It’s not always blazing, but it’s really something when you can feel it rekindling.

We often invoke 1969 and 1973 for purposes of never giving up when the going gets tough, and we certainly value the later peaks we scaled after wandering aimlessly through competitive valleys. But only the mid- and late-1980s — 1986 at the heart of that era — live on as aspirational to us. Situationally we might cross our fingers and hope real hard for another Grand Slam Single or Tears of Joy homer, but what we really want is the reincarnation of Baseball Like It Oughta Be. We want to be fans of the one team that we’re certain will get it done, that we’re certain will do in whoever dares to take the field in opposition to them. We want to go 108-54 in the regular season and 4-0 in brawls. We want to face impossible odds and live to repeat stories of how we overcame them because there was no way we weren’t going to. We want to conclude we are invincible.

That sensation has endured deep in the soul of the Mets fan who experienced the Mets as molded on high by Cashen and on the ground, where the leather and the lumber met the road, by Keith Hernandez. For all the woe-is-usness that pervades the Metsopotamian psyche in the 21st century, there resides in a deeper recess the sense that we’re the biggest, we’re the baddest and just you try to fuck with us. It’s alive and it’s dying to come out and play. I could feel it rise up from the throng that was trundling down the LIRR boardwalk around 1:15 Saturday, preparing to merge with the mass of humanity queued up partly to secure a bobblehead, mostly to reclaim the birthright issued unto us on June 15, 1983, and notarized for all time on October 27, 1986.

I wasn’t there for a bobblehead, though I wouldn’t have turned one down. I was on my way to the media will call window, having arranged for press credentials in order to cover a historical milestone, the retirement of No. 17. So on one level, I had the distance to act as dispassionate anthropological observer of the Met phenomenon. Yet I’m never not a Mets fan, even when I waive my Stengel-given rights to yell like an idiot by taking a seat in the press box. That walk from the train through the plaza took me back. I’ve been in loads of Met crowds since 1986. This one was a crowd from 1986. Not just for the retro threads (some of those World Champion t-shirts were vintage) but for the prevailing attitude. We only came here to do two things: kick some ass and grab some bobbleheads. Looks like they’re almost outta bobbleheads.

There’s something in my eye, you know it happens every time. This was the gathering crowd that congregated to usher Keith’s No. 17 into official Met immortality, as if a ceremony were required to confirm everything Hernandez did and represents. As with the bobblehead, you’ll take it. The Mets sold every ticket they had because Keith Hernandez was the center of attention Saturday. The 1980s showed us Mets games with Keith in the middle of everything inevitably attracts waves of attendance and enthusiasm. Keith was very much there and very much into it. Keith was on point, as Keith likes to say, from the moment he entered the Shannon Forde Press Conference Room. Keith was as passionate about being honored as he was when he went about earning the honor. He didn’t take a drag from a Winston or a swig from a Michelob as he might have when he addressed reporters in the clubhouse between 1983 and 1989. He spoke to us through teary eyes (a symptom of having trouble sleeping the night before, he swore) and a full heart. A guy who displayed determination rather than a grin on his face while he was plotting ways to attain victory explained what made him smile in 1986:

“When you win 108 games, that’s a lot of fun coming to the ballpark.”

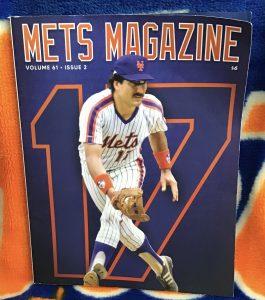

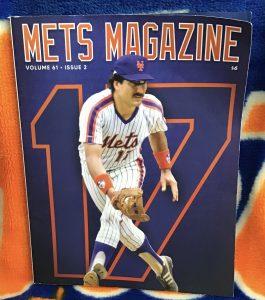

When you arrange to unveil 17 and invite a passel of Keith’s relatives and a sprinkling of his former teammates — Mookie Wilson, Tim Teufel, Ed Lynch, the ever-present Ron Darling — to the field to celebrate it alongside 43,336 who were on hand to thank Keith for making this day absolutely necessary, that’s fun, too. The Mets have upped their commemorative game the last couple of years. The people who choreograph these events understand the beauty is in the details. Hits of the ’80s played throughout the pregame for the man who recorded so many hits during the ’80s, though when the playlist departed its demographic foundation for one very specific track from 1999, “17 Again” by Eurythmics, it couldn’t have been more purposeful. There was a 17 tarp covering home plate. A 17 sculpture rising at second base. A 17 mowed into center field. A 17 emblazoned on The Apple. First base itself was dyed gold. A gorgeous mosaic of Keith’s face pieced together from Keith Hernandez baseball cards and (what a touch) 1986 Mets Strat-O-Matic cards was presented as the loveliest of tokens of appreciation. The owner of the club, who received an uproarious ovation, comprehends the resources devoted to something like Saturday are well worth the emotional payoff.

Wrong base, pretty boy. Keith came through, as if with the bases loaded and Hurst on the mound. “Little old me in St. Louis,” he reflected of his mindset in the middle of June 1983, “wasn’t very happy. What did I know? A life- and career-changing event, I cannot tell you.” But he did tell us, recounting his first debriefing by Cashen (“we have not squandered our draft picks and we feel we’re ready to turn the corner”) and his tempered reaction (“I was disbelieving”). But the last-place Mets Keith came to were about to find better places. Second, then second again, then first in the division, the league, the world. Then a few more years when the Keith Hernandez Mets didn’t repeat as world champions but they were still the Keith Hernandez Mets, and what an era it was to realize you rooted for this man and his team. And what a gift it was to hear Keith connect himself to all that came before him and came after him:

“I am absolutely humbled and proud that my number will be up in the rafters, for eternity, along with Casey, Gil, Tom, Mike and Jerry. Sixty years of New York Mets!”

And he reserved a few words for the first-place team representing the sixty-first year, already in progress:

“This current team I love to watch. You Mets fans, you’re on top of it, this teams comes out, it hustles, they play hard and comport themselves like professionals. It is a treat. You should give your support to this team like you gave us in the Eighties.”

We did. I use “we” in the Met-aphorical sense because I spent most of the game that followed in the Jay Horwitz Press Box (gosh, the Mets are getting good at naming things) and could only monitor rather than contribute to the din supporting the 2022 Mets. Except for one inning, the sixth, when I emerged from the air conditioning and embraced the heat of the day up in Promenade with my friend Kevin. There echoes of Shea’s Upper Deck resonated as Francisco Lindor wrapped a pitch around the left field pole to give the Mets a one-run lead of 3-2, regaining an edge that had been briefly yielded in the top of the inning when the Marlins — who weren’t even alive in 1986! — dared cobble a one-run lead of their own. We’d built the first one-run lead of the day, in the fourth, when Pete Alonso homered loudly to make it 1-0. Alonso, you’ll note, is a first baseman like Keith. Not as good defensively. Has more power. Also has a ways to go in growing a mustache, but he’s trying.

Back in Jay’s box, I watched the Mets not add to their three runs in the seventh, eighth or ninth, which was a pity because the Marlins sourced power from Jesus Aguilar’s leadoff at-bat versus Adam Ottavino and tied the game at three. We went to extras, though not exactly as we might have in 1986, because nobody was intentionally putting runners on second to start innings then. The Marlins pushed across their unearned runner ASAP to make it 4-3 and put Keith Hernandez Day in peril.

How about that Apple? Not many days featuring Keith Hernandez in Flushing ever stayed in peril. We got our own free runner on second, we got our chance to manufacture a run or, better yet, two, and, after two outs, we capitalized. Don Mattingly’s Marlins facilitated, as Don Mattingly’s Marlins will (Mattingly himself was ejected earlier — and he wants to be our latex salesman?). But what’s a first-place Mets team if it doesn’t accept a bobble like it’s a bobblehead? Tómas Nido, playing in place of a potentially injured James McCann (there was a bit of that going on, with Ender Inciarte having to replace Starling Marte), made contact. Never underestimate contact. I didn’t think the ball Nido sent to third with Mark Canha on second was going to result in a run, but it did. Miami third baseman Brian Anderson couldn’t lay a glove on it and, just like that — snaps fingers, conjures visions of Carter, Mitchell and Knight this other time it was tied in the bottom of the tenth — it was 4-4. Brandon Nimmo came up next with Nido, a slightly more earned runner, on second. Nimmo also made contact, less of it than Nido had, but he hadn’t struck out. Mookie once made contact after fouling off a whole lot of pitches. In Nimmo’s case, he hit a ball all the way back to closer Tanner Scott. Scott had already left the door ajar. He was about to blow it wide open. First he couldn’t handle the comebacker. Then he threw it in the dirt rather than within proximity of Aguilar’s mitt. Nido scampered home. The Mets won, 5-4.

Word from Jacob Resnick on Twitter was this was the first Met victory pulled from the jaws of defeat in more or less this manner — two outs, extra-inning, error, walkoff — since the sixth game of the 1986 World Series. Of course it was. Jake produced his Stathead receipt that showed it had happened twice before in Mets history. One was Buckner, but the other was also in 1986. It was a sloppy game from the end of May that stumbled into the tenth inning at Mets 6 Giants 6. Robby Thompson led off the visitors’ tenth with a home run off Jesse Orosco. If doom was in the air, the Mets didn’t inhale. In the bottom of the tenth, that Hernandez fellow singled to lead off. One out later, Kevin Mitchell, pinch-hitting for sore-thumbed Darryl Strawberry, singled. A wild pitch moved them both up a bag. Howard Johnson walked. Ray Knight lifted a sacrifice fly to score Keith. It was 7-7. The Mets were still alive. As would be the case in late October, and again in a far-off July, the Mets now knew they couldn’t lose in ten. They could very well win.

Light-hitting Rafael Santana — I’m sure that was his full legal name — batted next. He popped up over the infield. Second baseman Thompson moved underneath it to catch it. So did shortstop Jose Uribe. Instead, they caught each other, colliding while Santana’s ball dropped to the ground. “They both called for it,” Will Clark said afterward. “Heck, I was calling for it, too.” (Baseball Reference mysteriously lists the play as a ground ball, but as the 1986 Mets who lost 54 games in the regular season and five more in two postseason rounds could assure them, nobody’s perfect.) Mitchell crossed the plate. The Mets raised their record to 31-11 that night, the best a Met record had ever been after 42 games. There’d be a lot of “best ever” to come for those 1986 Mets, but that Friday night may have been the game that signaled the down/out quotient that would define that team would be its constant. Sometimes down. Never out.

The 2022 Mets seem to have a handle on such an equation. Fans of the 2022 Mets, with a heaping helping of Twisted Sister’s and Keith Hernandez’s shared credo of we’re not gonna take it inhabiting their subconscious, figured it out, too. People stuck around to the coulda-been bitter end. People raised the 17-laden rafters with their vocals when the bitterness of falling behind the Marlins went the way of the Marlins’ short-lived lead. As I rejoined the throng on the staircase, again an impassioned fan rather than a detached witness, “LET’S GO METS” bounced off the walls every bit as much as Scott’s throw bounced in the dirt. I did a little of that bouncing myself.

by Greg Prince on 9 July 2022 12:27 am 1. The Mets ran this ticket special in the 1980s that was incredibly successful. For the price of one admission, you could see the most fearsome competitor in the game, a peerless clutch hitter and first base play that was as revolutionary as it was nonpareil. They were also willing into throw in for that one ticket a consistent .300 hitter, a guy who ran the game like a point guard and a window into the mind of the most intelligent ballplayer you’d ever see or hear. Oh, and if that wasn’t enough to lure you in, you’d watch somebody who was looked up to by almost all his teammates, experience the hit that turned around Game Seven of the World Series and, if you requested it, the second-hand effects from a stream of Marlboros. Actually, you got the cigarettes whether you wanted them or not. Still and all, a really great deal. The Mets sold a lot of baseball with that package, especially in ’86. It was an incredible deal. So was the one they made in ’83 that made it possible.

2. The above paragraph was written, by me, in 2005. I believe it still holds up as testament to the abilities and impact of Keith Hernandez, first baseman for the New York Mets from 1983 to 1989. I wrote it an appropriate 17 years ago to introduce the new blog Faith and Fear in Flushing’s recall of Mets history, and who could recall Mets history without wishing to dwell on the presence of No. 17, Keith Hernandez?

3. No. 17 becomes officially retired this Saturday, July 9, 2022, one day after an aggravating Mets loss to the Marlins and 32 years since the man who wore it last played major league baseball. It’s fair to rhetorically ask, “What took so long?” though at this point the answer is irrelevant (we’ll say it was the Wilpons). Once a number or a plaque goes up, it’s tough to summon dissatisfaction with the flaws in the process that kept the ceremonies from happening all those years.

4. Yet 32 years is a very long time to have waited to bestow an honor on a figure so essential to this franchise’s identity. Then again, the Pittsburgh Pirates waited 32 years from Ralph Kiner’s final game — like Keith, Ralph finished up with Cleveland — until they decided No. 4 should be retired. From the vantage point of someone who’d spent a lifetime learning baseball from Ralph Kiner (and learning what Ralph Kiner did to a baseball in Pittsburgh), that seemed absurdly long, too.

5. Ralph and Keith, besides both theoretically filling out a blank Wordle row, proper noun prohibition notwithstanding, strike me as riding similar trajectories after their distinguished playing careers concluded. Their fame grew in so-called retirement, certainly in New York. The Pirates may not have been directly nudged into action by their erstwhile slugger and matinee idol having become a broadcasting institution for their rivals to the east, but by 1987, they could no longer dismiss all he’d meant to their history. His 4 was too big to ignore at the confluence of the Allegheny and the Monongahela. Ralph said it didn’t bother him that the club that traded him to the Cubs in 1953 waited 34 years to properly honor him, but others where the mighty Ohio River took shape saw it differently. “We’re talking here about one of the greatest players ever to put on a Pirate uniform,” his old roommate Frank Gustine vouched in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette as the Kinercentric ceremonies approached. “Why it took so long I really don’t know.”

6. Why it suddenly happened for No. 17 in 2022 when every opportunity existed through the 1990s, the 2000s and the 2010s perhaps speaks to the presence of a new team owner in Flushing (come to think of it, the Pirates were under fresh management in 1987). Maybe once the Mets got Mike Piazza’s 31 and Jerry Koosman’s 36 squared away, the prevailing vibe was “who’s next?” Keith’s been next for a while. The Mets were last when Keith showed up. They were first soon enough.

The only number that matters today. 7. Keith Hernandez ranks 13th among all Mets in base hits, 12th in runs scored, 12th in doubles, 10th in his beloved ribeye steaks, 15th in extra-base hits, 12th in total bases, 10th in times on base, 40th in home runs, 6th in walks, 4th in on-base percentage, 26th in slugging percentage and 15th in OPS. Only in batting average, something for which he won a crown in St. Louis, does Keith rank in the career Top Three of a discernible category for the franchise, with his .297 average third, a long way shy of John Olerud (.315) and currently five points behind a surging Jeff McNeil. Keith Hernandez doesn’t rank first in any given offensive grouping that Baseball-Reference bothers to track.

8. Yet if you needed a Met up to continue a rally, to bring a runner home, to tie the score, to win a game, who is the very first Met you’d want up at bat?

9. Defensively, I don’t have a number handy to explain No. 17. I don’t need a number to explain No. 17 in the field. If you didn’t live through the Gold Glove defense, you’ve seen the highlights. As with the hitting, the truth lives up to the legend. From the annals of real-time jaws dropping in disbelief, however, I think it useful to share a few quotes from a June afternoon in 1984 when Keith Hernandez’s positional expertise — first displayed in snagging a Tim Raines liner that appeared destined for extra bases, then by rescuing a double play relay that Jose Oquendo bounced in the dirt, both in the same inning — was making agape the standard formation for mouths all around Shea Stadium.

• “What can I tell you, he’s the greatest. We’ll see that all year, though, not just today.”

— Davey Johnson