The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 3 August 2022 10:58 am Juan Soto, now of the San Diego Padres, has been hailed as a generational talent, the type who comes along alone approximately once per metaphorical blue moon. His numbers, expressed by slashes and birthdays, support that assertion. Juan Soto is a .291/.427/.538 slasher through nearly 2,500 plate appearances and he’s not even 24 years old. No wonder the Washington Nationals offered him a yachtload of money to stick around for the balance of his career. No wonder Soto turned it down, considering he could look forward to attracting an armada of dollars when he hits free agency like he hits major league pitching. No wonder he’s suddenly in San Diego. His past is already pretty good. His future looks bright. I’m glad the Mets don’t have to face him as often as they used to. I wouldn’t mind his future eventually finding its way to Flushing.

Generational, though? It’s hard to be certain unless you’ve had generations to prove it. You know who was a generational talent, who remains a generational talent and who will always stand as the generational talent of his craft?

The voice that spanned baseball generations.

Longevity is a heckuva badge to pin on somebody who lasted seemingly forever, but it’s not enough of an award for the memory of Vin Scully, who died Tuesday at 94. It’s not so much that Vin Scully was the Dodgers announcer in 1950, a year during which he was 22, and was the Dodgers announcer in 2016, signing off for good when he was 88. The length of his career, in and of itself, transcends impressive. Hardly any ballparks still standing have lasted as long on the job as Vin Scully did, and the ones that have each underwent significant renovations. Vin Scully was Vin Scully in 1950 and remained Vin Scully in 2016. He didn’t much change. He just kept being the best.

That’s more than longevity. It has to be. Implicit in manning a microphone from coast to coast, from Truman to Obama, is that nobody maintains the same high-profile role of a lifetime for 67 baseball seasons without vaulting to the top of his game and gripping that peak without pause. Loyalty and endurance can buy you some extra years in the right circumstance. The only circumstance that mattered where Vin Scully was concerned was he broadcast baseball games like Vin Scully. It was a singular skill set. If you couldn’t find another Vin Scully — and by definition you couldn’t — you couldn’t, shouldn’t, wouldn’t seek an alternative.

Ken Burns explained the thinking behind his choice of announcer talking heads for his Baseball project thusly: he wanted the grandfather, the father and the son. For him, that meant Red Barber, under whom Scully apprenticed in Brooklyn; Scully, who’d grown into an institution locally in Los Angeles and nationally whenever he moonlighted; and Bob Costas, who did the backup Game of the Week on NBC every Saturday while Scully took care of the main attraction. Barber called his first big league game in 1934. Costas is still calling them in 2022. Like Scully, they are ensconced in the mythical broadcasters’ wing of the Baseball Hall of Fame. Burns’s intuition was right on, and his landmark documentary series benefited from encompassing the observations of both Red Barber and Bob Costas. Yet, honestly, the filmmaker could have gone with just Vin Scully and it would have served essentially the same purpose.

Vin was every generation. His status as the elder statesman who broadly bridged the millennia notwithstanding, whenever he was asked about what drew him to broadcasting, he was a kid again, inevitably describing (and always managing to relay it as if nobody had ever before inquired) parking himself under the radio speaker in his family’s living room, wishing to be bathed in the roar of the crowd. He followed the crowd to the source of that sound, out to the park and up to the booth, intent on telling the crowd what he and, soon enough with television, they were seeing. There were differences to calling a ballgame on radio and accompanying one on television. Nobody better understood that sometimes you’re the eyes for your audience and sometimes you’re chaperoning pictures, and that the pictures themselves can be left to tell key portions of the story best. Vin was every generation. His status as the elder statesman who broadly bridged the millennia notwithstanding, whenever he was asked about what drew him to broadcasting, he was a kid again, inevitably describing (and always managing to relay it as if nobody had ever before inquired) parking himself under the radio speaker in his family’s living room, wishing to be bathed in the roar of the crowd. He followed the crowd to the source of that sound, out to the park and up to the booth, intent on telling the crowd what he and, soon enough with television, they were seeing. There were differences to calling a ballgame on radio and accompanying one on television. Nobody better understood that sometimes you’re the eyes for your audience and sometimes you’re chaperoning pictures, and that the pictures themselves can be left to tell key portions of the story best.

More than anything, the warmth in Vin Scully’s voice will stay with me. Every announcer invites you to stay tuned. Vin really welcomed you. Vin wanted you at the game, understanding that he was your conduit and it was up to him to provide you the most comfortable seat, the most accurate view, the most thorough and thoughtful experience possible. Vin also knew, even as he was the most accomplished, most experienced, most revered and most famous broadcaster in baseball history, that he himself wasn’t the game. He — along with Schaefer, Lucky Strike, Farmer John or whoever was footing the bill — was simply bringing it to you. And wasn’t he fortunate for the privilege?

Weren’t we?

by Jason Fry on 2 August 2022 11:10 pm Jacob deGrom returned, as promised, and was more or less as we remembered — he hit 102 on the D.C. gun, looked like his old lanky and deadly self, and befuddled various Nationals with most of his arsenal. The lone blemish came in the fourth, when deGrom’s location eluded him and Victor Robles and Luis Garcia turned a single, stolen base and double into a Washington run.

The Mets, perhaps, overdid it in honoring deGrom by offering him the kind of run support they too often gave him in recent years, which was to say nothing. They had Cory Abbott on the ropes in the first, driving up his pitch count with grinding, relentless at-bats, but got nothing with the bases loaded and did little against Abbott after that.

Francisco Lindor got deGrom off the hook with a leadoff homer in the sixth against Victor Arano, but by then deGrom was out of the game as well, and the Met bullpen wasn’t up to his standard. Stephen Nogosek surrendered homers on consecutive pitches to Garcia and Yadiel Hernandez, while Yoan Lopez allowed a homer/first hit to 30-year-old MLB debutant Joey Meneses, who got the ball back thanks to his bullpen and their trade with a kindly Nats fan (wearing a Washington SCHERZER 31 jersey, no less).

That was a nice moment on what turned out to be the Nats’ night — an unexpected story that even those of us rooting for a different outcome had to admit was a bit heartening, seeing how the Nats had been stripped of not just superstar Juan Soto but also Josh Bell, Soto’s only reliable lieutenant in the lineup. Both were shipped off to the Padres, hyperactive as always come deadline day, in return for a haul of young players and prospects. A pretty good haul, to my eyes, but is any return worth giving away Juan Soto before his agent tells you that you have to?

The Mets were active at the deadline too, though not particularly in the way their fans — or at least those loudest on Twitter — had hoped. Willson Contreras stayed in Chicago, while David Robertson joined the Phillies’ bullpen. J.D. Martinez remained in Boston, but another J.D. — Jonathan Gregory Davis — left the Mets for San Francisco, along with Thomas Szapucki and a couple of prospects. The return for them was Darin Ruf, who should slot in as the other half of a capable designated-hitter platoon with Daniel Vogelbach.

Just before the deadline, Ruf was joined in the Met ranks by reliever Mychal Givens, a Showalter stalwart from Baltimore. But the pined-for lefty reliever — the commodity the Mets arguably most needed — never arrived.

Fan reaction ranged from disappointed to betrayed, with no one seeming particularly interested in GM Billy Eppler’s explanation that the cost for a lefty out of the pen had been too high, or his warning that “undisciplined thinking” — i.e. giving away too many prospects now — “can lead to years of mediocrity.” It didn’t exactly help Eppler’s case that the lesser lights of his existing bullpen got walloped by fill-in Nats a couple of hours later.

Was I disappointed? A little, sure. Like everybody else, I wanted a lefty other than Joely Rodriguez out there — and I’d daydreamed of catcher being something other than a black hole. But I’ll withhold judgment for now, having no idea what the dynamics of those GM-to-GM phone calls were, or how high various teams’ asking prices might have been.

(One thing I suspect might have been at play: Steve Cohen’s offseason showed he wasn’t afraid to spend, and he’d spoken of being aggressive regardless of payroll penalties. I wonder if other clubs, armed with relatively little information with which to judge Cohen and Eppler, figured the Mets would blink in their determination to make another splash, handing over blue-chip prospects in return for a rental or two.)

I was saddest about the departure of J.D. Davis, who probably needed another home but was a reliably entertaining Met, from his weirdo back-formation nickname and his inept heckling of opponents to his gonzo postgame speeches and buddy-cop friendship with Pete Alonso. Davis often seemed completely insane, or at least a little touched, but he had a sense of the ridiculous that I always appreciated, and I wish him well.

His replacement, Ruf, should arrive soonest, as should Givens and old friend Trevor May; they’ll displace Kramer Robertson (whose likely lone day on the roster without playing will make him the fourth Met ghost of 2022, joining Gosuke Katoh, R.J. Alvarez and Sam Clay) and two relievers, probably the recently luckless Nogosek and Lopez.

None of those gentlemen is left-handed, so that rather obviously remains an issue. Maybe Rodriguez will find the form he’s shown at times and fumbled for at others. Maybe the job falls to David Peterson, superfluous as a starter through no particular fault of his own. Maybe Clay escapes ectoplasm and becomes a flesh-and-blood hero when we need one the most. Perhaps Joey Lucchesi reports for late-summer duty with a repaired elbow and something to offer. Or maybe that’s a hole that goes unfilled and we rue what didn’t happen at the beginning of August.

I have no idea. No one does. For now, deGrom’s back. That’s the kind of good thing other teams dream of having happen to them. Let’s not lose sight of that.

by Jason Fry on 1 August 2022 11:43 pm Back in the second game of the season, the Mets faced the Nats in D.C. behind Max Scherzer, who was making his debut in orange and blue. (Scherzer followed Tylor Megill, the obvious pick for Opening Day starter.) It didn’t go well for Nats starter Josiah Gray, who was driven from the mound in the fifth and relieved by Steve Cishek — whom I’ll always think of as a Marlin, but that’s another post.

With the Mets up 4-3, Cishek faced Francisco Lindor, who tried to bunt and took a ball to the helmet. Benches emptied, with an irate Buck Showalter front and center. Lindor was shaken but unhurt, Cishek shaken but ejected, and an inning later the Mets got loose in the Nats’ bullpen, turning a 4-3 squeaker into a some-muss, some-fuss 7-3 win.

What a relatively little difference four months makes. (OK, three months and three weeks. Basically four months, Steve.) This time it was Patrick Corbin facing Scherzer, but once again the Nats starter got racked up early, Scherzer proved an odd mix of dominant and ragged, and the game reached the point where the Mets had a 4-3 lead and Lindor was facing Cishek.

(No really, it did. I mean, of course it did. Because baseball.)

This time, Lindor didn’t get hit by Cishek– that honor went to Starling Marte, with the accompanying Showalter glower. But Cishek’s first fastball to Lindor was head high and in — a moment Lindor admitted after the game scared him, rejecting the usual dopey oorah omerta of athletes for something more true, raw and honestly brave.

And then, two pitches later, Lindor got a fastball at the knees that had way too much plate and clubbed it into the Mets’ bullpen — the best kind of revenge. That made the game 7-3 — the final score Monday as it was on April 8, because baseball.

A lot has happened to the Mets since that second game, most of it so good that you may have pinched yourself a time or two. And it’s fitting that Monday’s game should have been an odd bookend to that April one, because a lot figures to happen to the Mets on Tuesday, as the regular season begins its finishing kick.

Jacob deGrom will start at long last, of course, more than a year after last striding a mound in anger, finally going back to back with his co-ace in the rotation. DeGrom may have new teammates wearing unaccustomed uniforms, or possibly ones still elsewhere settling their affairs with the trade deadline just an hour in the rearview mirror. Or perhaps deGrom himself will be the most-ballyhooed addition — he’d be a pretty good one, you’d have to admit.

One way or another, Tuesday’s Mets will be different. But they’ll be building on what’s come before, on the successes of Scherzer and Showalter and Lindor and Marte and Pete Alonso and a happily long list of others. That story … well, it would be too pat to reduce it to getting knocked down and not putting up with it and getting up and hitting the next one out of sight. But it wouldn’t be entirely wrong, would it?

It’s been a fun story, but we’re in the middle. We can talk about what it all means later, when the book is closed. For now, well, I can’t wait for the next chapter.

by Jason Fry on 31 July 2022 11:02 pm A funny thing happened midway through the Mets’ laugher of a victory over the Marlins.

The Mets were leading 7-1 at the halfway point of the game, having undressed poor Pablo Lopez in Soilmaster Stadium, and every hitter was on point, from Francisco Lindor continuing to beat all available Marlins like a drum to Patrick Mazeika slug-bunting singles around the shift.

And then Taijuan Walker lost a little focus, or a little steam, or maybe a bit of both. It was 7-1 after five, and Walker went back out for the sixth, and after a double and an RBI groundout and a home run (the first for the Marlins in the last 567 home games, if I heard correctly) it was 7-3 Mets, and so Tommy Hunter came on and his third pitch became a double and the Marlins were a hit away from being within three and all of sudden it sure seemed like there were a lot of outs yet to get.

The laughs, in other words, came with some pauses and then stopped.

And then Hunter struck out Joey Wendle and the Mets came to bat again and almost before you blinked they had two more runs. The first came when the Marlins somehow turned Luis Guillorme straying too far past second into an opportunity for Mark Canha to hurry home. The second came when Lindor smacked a bad-hop grounder that left Wendle starring in his own Jar Jar Binks deleted scene, with the ball caroming far enough away from the luckless second baseman that Brandon Nimmo was able to score all the way from first.

Just like that, the Marlins’ sixth-inning gains had been erased. The air came out of the teal and pink and black and white balloon, and from that point on the Miami hitters were no more than an occasional bother as the back of the Mets’ bullpen cleaned up the mess. It ended with the Mets winners by six runs, having pounded out 19 hits. Every member of the starting lineup ended the day with a hit. All but Mazeika scored a run. As for July, it goes in the books with the Mets having posted a 17-8 record and sitting 27 games over .500.

I don’t know how this season ends for the Mets. I don’t know if the statistical and spiritual antecedents being celebrated are heralds of something special or will become cruel pointers to what might have been. All of that will play out and we’ll chronicle it and it will make sense when it’s over, or at least when it’s over we’ll start telling the stories that we think feel the closest to summing it up.

That will be fun and exciting and anxious and lots of other good baseball things — and I was thinking of them on Sunday afternoon as the Mets rolled over the Marlins and beamed and slapped hands and said the right things in the clubhouse before catching a plane to D.C.

But I was also thinking of the other team. Not with pity or even particularly with charity, because the Marlins have bedeviled both me and baseball too often to deserve either.

But empathy? I could muster a little of that.

I’ve rooted for Mets teams that are on the wrong end of a laugher and start clawing and biting and somehow manage to make you believe again, or at least start trying on the idea that you might believe. And I’ve seen those same teams quash that flickering hope by returning tragically and instantly to themselves, turning spunk into slapstick and making you hate yourself for getting suckered again.

The AP recap linked to above notes that the Marlins entered this series on the periphery of the wild-card hunt, but that says a lot more about how watered down the playoffs are about to become than it does about Miami. Because the Marlins are bad — one of those teams that goes into battle with the rifle aimed at its own feet, so that every martial maneuver makes you cringe until the inevitable happens.

(And though it’s a borderline sin to point it out, what with Don Mattingly all but canonized as a mid-80s New York baseball saint, the Marlins also look badly led. They make mental mistakes and drag themselves around the field and fail to tamp down clubhouse dramas and the only apparent reaction from leadership is a slightly more steely look from above the dugout rail.)

I’ve rooted for those teams. Stubbornly and foolishly because I had no choice. I’ve done so while grimly aware my only reward would be that eventually the season would end and the bad team would get reconstituted into a different form. Heads would roll, justly and perhaps not, and I’d get a new team to assess.

The 2022 Mets promise rather different rewards. But in daydreaming of what those might be, I can’t shake entirely the shadow of those other seasons, the ones that became object lessons in patience. This year I’m lucky enough to root for a very good team — one that might be considered great before all is said and done. But I know I’ll find myself rooting for one of those other teams again. And I know it will be sooner than I’d like to think.

by Greg Prince on 31 July 2022 3:48 am Heartiest congratulations go out to Carlos Carrasco, who used the occasion of the Mets’ 100th game of the season to notch the 100th regular-season win of his career. He was supported in his effort Saturday night at Miami by solo home runs from Jeff McNeil, Francisco Lindor and J.D. Davis and backed up by another solid relief stint from Seth Lugo, all chipping in to make the Mets’ fifth consecutive triumph possible, but this was Cookie’s party, and he pitched well enough to earn both the milestone W and a celebratory Cookie Puss if he so desires one. He went 7⅔, scattered four hits, walked only two, struck out seven, induced a parade of lazy flyouts and easy grounders, and allowed no runs to any Marlins. Neither did Lugo, making Carrasco’s hundredth, a 4-0 shutout, that much more festive.

Gonna need a couple so every one of Cookie’s teammates gets some Puss. In this age of de-emphasis on pitcher wins, any given hurler’s entry into triple-digits seems that much more noteworthy. Why, in my day, the fan who’s been around can’t help but contribute to the conversation, you didn’t even look up from your box scores until a pitcher won 300. Of course if you’re the pitcher reaching 100, it’s a big deal. If you’re a fan of the team for whom the pitcher is employed, it’s a nice bonus. Should we come to remember Cookie Carrasco as part of that championship staff from 2022, his milestone might become our milestone.

Proprietary Faith and Fear research (that would be me messing around on Baseball-Reference rather than going to sleep) indicates Carrasco is the eleventh pitcher to earn his 100th career win as a New York Met. That’s not the same as winning 100 games as a New York Met. Only three Met pitchers, each of them homegrown, can say they did that, and their identities should come as no surprise to the Mets fan who’s been following the team for more than five minutes: Tom Seaver (winning the hundredth of his career on May 11, 1972), Jerry Koosman (June 24, 1975) and Dwight Gooden (June 19, 1989). Just missing the 100 wins as a Met boat were 99-game winner Ron Darling, Sid Fernandez (98) and Al Leiter (95). Darling’s and Fernandez’s cases are a little heartbreaking given that, like Tom, Kooz and Doc, they started counting at 1 in a Mets uniform. So freaking close! Darling noted during Saturday’s telecast that his 100th came for Montreal while he waited for the Expos to trade him to Oakland. El Sid was an Oriole when he dug into his juicy round number.

Leiter, as a veteran, showed up at Shea with 60 wins in his pocket, and he stayed in Flushing as never less than a co-ace seven seasons The math suggests he must have won his 100th career game as a Met even if he fell five short of winning 100 games for the Mets. And the math is correct; Leiter claimed his 100th W on July 1, 2000, shutting down Atlanta the afternoon after Mike Piazza capped the ten-run inning that doesn’t require much elaboration even 22 years later. At that point, Al was 10-1 on the season and headed to his only All-Star Game as a Met. Presumably, he got to dress in the corner of the clubhouse reserved for pitchers who knew from the century mark.

Another long-timer who didn’t begin as a Met but put up significant numbers — and not just in the time of game column, wise guy — was Steve Trachsel. Given that he joined the Mets with 68 wins behind him and he’d stick around for six seasons, earning his 100th win while wearing a Mets uniform was only a matter of…yeah, time. In Trachsel’s case, the milestone became his on August 7, 2003, in Houston. Trachsel went five innings and the game took less than three hours. Steve would be a career 134-game winner before moving on from Queens. (And, no, it didn’t take him until last week.)

You know Johan Santana had a penchant for doing big things on June 1. Did you know that Johan’s 100th career win a) came as a Met; and b) came on June 1, 2008, four years before his slightly more famous June 1 outing? Santana broke through as his fellow Venezuelan Carrasco did, with 7⅔ innings of sound starting, defeating the Dodgers at Shea on a Sunday night. If you don’t remember the details, the Mets scored five in the third inning; Carlos Beltran, David Wright and Ryan Church each drove in a pair; and most every Mets fan was sure the ESPN booth got everything completely wrong (that last one is an educated guess).

For those who remember Ray Sadecki as our affable early-’70s swingman, it might surprise you to know good ol’ Ray racked up 135 wins in a career that stretched back to 1960 and encompassed a 20-win season for the 1964 world champion Cardinals. When the Mets brought the reliable lefty in to fortify their own title defense in 1970, Sadecki arrived with 99 wins in tow. No. 100 for Ray was his first as a Met, a six-inning start that was good enough to beat the Expos on May 12 at Shea. Serving as the bridge between Sadecki and Tug McGraw that Tuesday night was the previous season’s fourth starter, now assigned to bullpen duty: Don Cardwell, who took a different route to his 100th career win. Whereas Sadecki nailed his down with his first Met victory, Cardwell socked away his 100th with his final Met win, a 6-1 complete game conquest of the Pirates on September 21, 1969. Don not only knocked off the Bucs, he reduced the Mets’ magic number over the Cubs to 4. In the context of the day, the 4 was bigger than the 100.

Cardwell had two wins ahead of him after No. 100, both as a Brave after the Mets sent his contract south in July 1970. A similar trajectory awaited a Met pitcher who likely isn’t much remembered as a Met. Then again, the man pitched for eleven different teams, so he may not be remembered as specifically affiliated with anybody. On September 1, 2011, Miguel Batista alighted at Citi Field on a mission: pass 99 wins. The rosters expanded, the Mets were wallowing in the depths of the NL East (a division Miguel knew well) and, well, what the hell? Let’s give the 40-year-old journeyman a shot. Batista’s journey led him to what he sought: a 7-5 win over the Marlins, his personal hundredth. Miguel endured for the rest of September, wrapping up his latest major league detour with a distance-going blanking of the Reds on the season’s final day (perhaps you know it better as the afternoon Jose Reyes removed himself after one batting crown-clinching AB). The Mets dug Batista enough to invite him back for 2012. He’d win one more game and, like Cardwell, finish as a Brave…where he’d win no games, serving him right for committing such treachery.

Assuming Carrasco earns at least one more win as a Met, we can say one Met finished his career on exactly 100 wins as a result of winning his 100th as a Met. That would be Randy Jones, who also won the 1976 National League Cy Young Award that Jerry Koosman couldn’t quite pick off via a late surge. Jones the San Diego Padre was sensational. Jones the New York Met was at the end of the line — literally. On August 6, 1982, Randy threw six effective innings at Three Rivers Stadium, good enough for a 2-2 tie when George Bamberger lifted his starter for pinch-hitter Mookie Wilson. With Hubie Brooks on second and one out, Mookie grounded to second baseman Johnny Ray. Ray erred, letting Mookie reach and Hubie go to third. Mike Howard would walk, Bob Bailor would strike out, and Ellis Valentine? Ellis would single to center, bringing home Brooks and Wilson and ensuring Jones could enter the clubhouse as the pitcher on the long side. Neil Allen, money in those days, took care of the final three innings, meaning Randy Jones could enjoy the distinction of being a 100-game winner in the major leagues.

Which was fortuitous timing, given that Randy would make one more start, at Shea, and be knocked out in the first (I was there). Bamberger relegated him to relief, where things weren’t very good, either. Jones never pitched in the bigs after September 7, 1982. But he’s got that round number and, like Mets from Tom Seaver, who got there first, to Carlos Carrasco, who got there most recently, they can’t take that away from him.

FYI, Max Scherzer is four wins shy of 200. Maybe we’ll have a chance to revisit the next strata of this topic in the near future. Cripes, I’ve already done the research, so you can in-game bet we’re gonna revisit this stuff.

by Greg Prince on 30 July 2022 11:25 am Through seven innings Friday night, the Mets-Marlins contest could have gone either way. It’s not unusual that the identities of a given game’s winner and loser are yet to be determined with two regulation innings to go, but this brand of uncertainty gnawed a bit deeper. Lose this game to the Marlins, and it’s a kick in the gills. Win this game from the Marlins, and we are swimming speedily toward our goals.

We won. The water is fine.

Crappy losses to the Marlins in Miami are as much a part of trips to the Sunshine State as tolls on the Florida Turnpike. Sooner or later, legend and precedent have it, you’re gonna pay. In our last visit to Whatever It’s Called Park, we couldn’t escape until a walkoff home run was given up. It’s the cost of doing business where visible sacks of Soilmaster and episodes of last-pitch heartbreak each amount to coin of the realm. We’d been charged once already in 2022. It leaves you thinking gates will be down and hands will be out every time you show up.

A couple of things, though. One, this is 2022. It may not be easy to admit against all mental defense mechanisms you’ve erected for your perceived well-being that 2022 is a season different from the stacks that preceded it in a positive sense. It is. Check the record. Check the standings. Check the highlights. Woe is Mets is some other year’s suitable refrain. Two, the Marlins aren’t as singular in their terror-striking ability as we insist on believing. Early in Friday night’s telecast, and not for the first time in recent weeks, Keith Hernandez said the Marlins always give the Mets fits. Define “fits,” Keith. The Marlins take the field competing to win and sometimes do is about all I can come up with. The Brewers do that. The Dodgers do that. This applies to everybody on the schedule from what I can deduce. When the Marlins do pull one out, it does tend to annoy, probably because it’s usually somebody we never heard of doing something we didn’t expect, possibly because we inherently believe that unlike the Brewers or Dodgers or every other National League opponent, they are unworthy of ever winning a baseball game, let alone a baseball game against the Mets. How dare a franchise whose ownership and operations are in a perpetual state of shambles somehow assemble nine to ten players capable of occasionally prevailing?

The Marlins are in their thirtieth season. If you’re not used to them by now, I don’t know what to tell you. If you think they have some specific black-magical hold over the Mets, I do know I can tell you the Mets are 39-31 since the onset of summer 2014 (a.k.a. the dawn of deGrom) when playing in Miami and 88-61 overall versus the Fish in that span. The fits are aberrations. The wins are the norm. Tell your “but they always find a way to lose to the Marlins” old wives’ tales to shut up.

Admittedly, I didn’t comfort myself with such sharp statistical confirmation after seven innings, for I’m as susceptible to Dark Ages thinking as any Mets fan when the Marlins are biting. I certainly didn’t tell myself that it was likely everything was going to turn out swell after one inning, the bottom of which was soiled by Marlin runs — three, to be precise. Met starters rarely give up three runs at all. To have them piled on in introductory fashion, with the none of the hits leading to them particularly resounding, was unnerving. Goodness knows Chris Bassitt appeared unnerved in the dugout following that first inning, apparently barking about infield shifts that did not work to his advantage.

Chris never quite looked himself over six innings — if this were an Afterschool Special, we’d discover some shady kid slipped a suspicious substance into his sack lunch — or perhaps the essence of Chris Bassitt slips out now and then. Sometimes it’s to betray impatience with his catcher. Sometimes it’s a case of starting-pitcheritis wherein if everything around him isn’t perfect, then nothing is remotely adequate. Each artist is permitted his idiosyncrasies, especially when he’s holding the ball in the center of the action. Chris admitted afterward that pitching with too much rest following the All-Star break and assorted other off days contributed to his feeling “too good,” something noted pitching coach Fernando, as portrayed by Billy Crystal, warned against when he advised, “It’s better to look good than to feel good.”

Bassitt didn’t look too good in the early going, and it wasn’t mahvelous. Fortunately, he is surrounded by Mets capable of picking their starting pitcher up. Usually it’s the starters who do the heavy lifting, but talented rosters can be versatile. The top of the second saw the Mets even matters against a quality starter — Sandy Alcantara — for whom three runs usually provides a brick wall. Alcantara could be the NL’s Cy Young, but a certain team is prone to giving him fits in his own backyard. The Mets nicked him for four runs in seven innings at Miami in June, and they didn’t wait long to overcome his budding résumé Friday. With one out in the second, Mark Canha belted a big double; with two out, Tomás Nido walked; Brandon Nimmo belted a bigger double (Canha scored; Nido should have but spectated a little between first and second); and Starling Marte belted the biggest of triples (everybody on base scored). In this Friday night fight, the belt was very much up for grabs.

Alcantara wasn’t impenetrable and Bassitt wasn’t in a hole. Well, Chris did stumble one more time, in the bottom of the second, on a walk and a single, but a run-scoring double play more or less rescued him. The Marlins were ahead again, 4-3, but they would be halted in their tracks immediately thereafter. Bassitt wasn’t smooth (four walks), but he was doggedly efficient, grinding six and putting up only zeroes through his final four.

Marte maintained his initial pace, and that was for the best. The triple from the second, which followed a single in the first, was complemented by a solo homer in the fourth. All of it was off Alcantara. All of it was on the heels of game-winner from Wednesday night. The entirety of 2022 has shown Marte’s forte for production. As right fielders imported by Mets teams aspiring to seriously improve, Starling Marte this year is the veritable reincarnation of Rusty Staub fifty years ago.

If you’ve looked at Marte this season and then try to reckon it with your image of Staub the last time he played, don’t stop at the 1985 pinch-hitter deluxe version. Rewind in your mind to 1972 if you can, or find yourself some footage. Le Grand Orange was a full-fledged, all-around ballplayer in his prime, and we got to enjoy two fruitful months of vintage Rusty, right up until Atlanta reliever George Stone — yeah, that George Stone — hit him in the hand on June 3. The first quarter of Staub’s season had his OPS over .900 and the Mets lapping the East. Then Rusty gets hit, he tries to play through the pain; he slumps; he sits; he comes back too soon; and 1972 goes to hell.

Rusty would eventually return in good shape and do great Rusty things over the remainder of his first Met tenure, but the Staub we got in 1972 was a template for what we’re getting from Starling in 2022. Impact. Dynamism. Intelligence. Rusty lacked speed, but he knew how to run the bases. Starling is blessed with every tool and uses them wisely and regularly. He’s also gotten a break in that his two bouts with leg problems came and went without obvious long-term implications. He’s out there every night, he’s slashing .305/.353/.482, and he’s a primary reason 2022 is heading in the opposite direction of where 1972 went.

Help is all around him. Though he didn’t figure into the scoring, Daniel Vogelbach continued to show he might have been worth the price of Colin Holderman (currently a Triple-A reliever in the Pirate system), reaching base once via walk and twice via doubles. On one of his two-base hits, he swung so hard that it loosened the chain around his neck. Imagine how much faster he’d be if not weighed down by jewelry.

Attaining jewelry is the main goal of this organization, whether through drawing new cards — welcome, Tyler Naquin (trade from the Reds); see ya, Travis Jankowski (DFA’d to clear space) — or by relying on the cards you’ve been nursing the whole time. Until merry prankster Jacob deGrom comes back Tuesday, Brandon Nimmo can claim Met seniority on the active roster. Old Man Brandon goes back to June 26, 2016. It only felt as if he hadn’t gotten a hit since then entering Friday night. The Nimmo who was on-basing so effectively that the last time he was in Miami wags were retrofitting classic pop lyrics to meet his moment had been in an offensive funk. Had been. We noticed a double in the first. We were overwhelmed by a homer in the eighth. Brandon, you’re still a fine Met.

As indicated, the score had been 4-4 as of the fourth and it stayed 4-4 until the eighth. Also as indicated, there was a Leon Russell “Tight Rope” sense to the evening. One side’s hate and one is hope. It’s always glorious to win, but it would really rule to reel this Marlin battle safely aboard the boat. It always sucks to lose, but it would really suck to lose this game, considering their three-run first, their nosing ahead anew in the second and the settling down Bassitt did to hold them at bay. We’d overcome so much tsuris yet we were never more than tied. We’d gotten, too, an inning of professional relief from Adam Ottavino in the bottom of the seventh, which led a viewer to wonder who’d pitch the bottom of the eighth, though first the viewer wondered what the picture would be by then.

There’d be garlands of glory and a paucity of gloom. Eduardo Escobar, pinch-hitting for Luis Guillorme, beat out an infield single (note to Don Mattingly: quit challenging calls). Nido bunted Escobar to second, which is something Buck Showalter seems to enjoy asking Tomás to do lately. And then came Nimmo. He came prepared for whatever Steven Okert would offer him. He’d make short work and a long flight out of it.

The Mets were up, 6-4, on Brandon’s bolt from the blue. We were definitely on the sunny side of the tight rope. Could eighth-inning specialist du nuit Trevor Williams keep us leaning toward life rather than the funeral pyre? Drew Smith was on the IL. Seth Lugo gave more than inning of himself in the last Subway Series thriller. Ottavino gave his all in the seventh. Holderman’s in Indianapolis. Williams? Why not?

Eleven pitches. Three outs. Good call.

All that was left to determine was how clean Edwin Diaz’s 23rd save would be in the ninth. I mean, yeah, there always the possibility of a bloop and a blast, or balls squirting past infielders, or some combination of error, balk and wild pitch adding up to disaster. Any of it would neatly echo the teal-tinged black Marlin magic that lingers in our heads. But, nah, not this time. Not with this closer.

Ten pitches. All strikes. Three outs. All strikeouts. Not immaculate. Close enough.

Diaz had his save. The Mets had their desired result. The game was in the win column, where it belonged. As fits go, it was perfect.

by Greg Prince on 28 July 2022 12:12 pm Max Scherzer pitched seven innings of shutout ball on his 38th birthday. Of course he did. He was born to put up zeroes on the night of July 27 in the borough of Queens before a sold-out house in attendance to cheer on a first-place team. It was foretold when he first drew breath and presumably glared a pea-sized hole through the forehead of his mother’s obstetrician.

July 27, 1984, wasn’t just any date in New York Mets history. It was a double-dip. We’d someday dip into Steve Cohen’s discretionary funds and sign the best pitcher ever born on said date, but that was a bunch of decades off. In the moment, as the Scherzers were mulling what to name their newborn in St. Louis (likely paying scant attention to the fifth-place Cardinals pulling out a tenth-inning victory over the sixth-place Pirates in Pittsburgh), Met fortunes were situated in the right palm of a pitcher roughly half the age of what Max would turn on July 27, 2022.

Dwight Gooden was pitching at Shea Stadium on a Friday night. That alone says so much, but on July 27, 1984, Dwight Gooden was pitching at Shea Stadium on a Friday night against the Chicago Cubs. That says even more. The New York Mets were in first place for the first time at such a late juncture in a season since 1973. Dwight was eight then. He was 19 now. The Mets had been nowhere as the kid from Tampa finished elementary school, junior high and high school. The Mets were so nowhere that they were able to draft Dwight Gooden, then 17, with the fifth overall pick in 1982. The Mets stayed nowhere until 1984, which not coincidentally is when we met young Dwight.

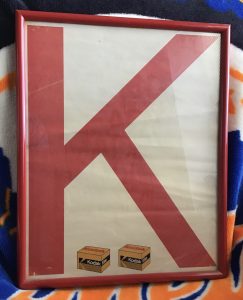

We called him Doc, as in Doctor K. You remember the unofficial last name. If you needed a reminder, you could glance up above left field at Shea. All the strikeouts Doctor K recorded were dutifully documented by fans who couldn’t wait until the next morning’s box score to know the total.

“In the left field upper deck, ‘the K Korner’ is open for business,” Joey Johnston wrote in Gooden’s hometown Tampa Tribune when the local product was tabbed to pitch in the All-Star Game. “Dennis Scalzitti and Leo Avolio, lifelong Mets fans from New Jersey, hang ‘K’ posters on the railing each time Gooden whiffs an opponent.” At two strikes, Johnston elaborated, “They wave the ‘K’ above their heads, inspiring the crowd to stand and cheer, urging Gooden to finish the strikeout.”

He did that a lot as a rookie. The rookie professed no great concern with his strikeout volume, which would add up to 276 by season’s end. I don’t worry about the ‘K,’” he said in early July after inspiring Scalzitti and Avolio to hang a dozen of them. “My purpose is to win games and help the team.” The Mets benefited from that attitude and that talent. Gooden lit up the All-Star Game on July 10 and kept electrifying the National League en route to the July 27 showdown versus the Cubs. It’s no wonder attendance spiked every time Gooden pitched at Shea. It’s no wonder that every seat was spoken for this time Gooden was pitching at Shea. The Mets were 3½ games up on the Cubs after a midweek sweep of the Cardinals, presumably to the dismay of Brad Scherzer, an expectant dad whose home team had fallen precipitously since trading Keith Hernandez the year before. Keith thought he was going to baseball Siberia on June 15, 1983. He wouldn’t have guessed baseball Paradise would be under construction thirteen months later.

On July 27, 1984, Doctor K kept the K Korner engaged, if not overwhelmed. More importantly, he kept the Shea scoreboard operator on a consistent keel. Doc allowed 1 run in the top of the first inning to the Cubs. The Mets answered back with 1 in the bottom of the first. And then, starting with the second, the top line looked like this:

00 000 00Those were Doc’s zeroes. It wasn’t achieved as neatly as one might have forecast — Doc had a little trouble controlling his fastball and walked seven; “I was pumped before the game and had to calm myself down,” he admitted — but Gooden’s sense of purpose spoke for itself. He gave up only four hits while striking out “only” eight. The Mets didn’t dent opposing starter Dick Ruthven decisively until the bottom of the seventh. Doc’s bat was in the middle of that rally, delivering a bunt that moved Rafael Santana to second and set up Wally Backman to drive him in. Doc protected the 2-1 lead he helped build before turning it over to Jesse Orosco. Orosco took care of the ninth for Gooden. Other teammates took care of his superlatives.

“That was the hardest I have seen him throw all year from start to finish,” said Hernandez, whose St. Louis affiliation belonged to a very distant past by July 27, 1984. “He didn’t have a curve at first and then it came to him. When it did, it was a hard curve. He had trouble keeping his fastball down at the start, but then he got it. That’s not a fastball he throws. Looking at it from first base, it’s a blazer. He’s like Sandy Koufax and Bob Gibson,” the latter the all-time favorite pitcher of Brad Scherzer. “He gets better as the game goes along.”

Backman agreed. “He keeps us in the game,” the second baseman said. “Dwight had a little trouble at the beginning but he started to go through them like so many high school players later on with his fastball and curve.”

Gooden won the game and helped his team. The Mets were 59-37, the most they’d been above .500 all year, the most they’d been above .500 since the end of 1969. They were 4½ ahead of the Cubs, another high water mark through 96 games. The National League East might as well have been made up of Hillsborough High School’s opponents back in Tampa. Doc indeed made everybody look like an amateur by comparison.

July 27, 1984. The date has stayed with me for 38 years. It would never get any better for the 1984 Mets after that night. They’d never be as many as 22 games above .500 the rest of the way. They wouldn’t lead the Cubs by as many as 4½ again. Soon they wouldn’t lead them at all. Yet 1984 gets a pass in the mind’s eye. It was the year the club came into its own, the year Doc burst on the scene (Rookie of the Year winner, Cy Young runner-up), the year Keith settled in (second in MVP voting). Keith remembered it well on July 9, 2022, when the Mets retired his number at Citi Field. The flag that flies over the right field porch says 1986. The great leap forward was 1985. But 1984…you never forget when the chronic losing stops and winning becomes habit-forming and hope is a legitimate instinct.

“When I went to Spring Training in ’84,” Keith recounted, “and I saw the group of talented athletes, all young, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, lookin’ up at me, I knew we had something special. And we did. […] All these young guys — Darryl, Doc, Ron, Walt, Ed, Mookie, Roger, Fitzy and Jesse — they rejuvenated my career.” They rejuvenated us, too. No, you don’t forget that.

***When the Mets acquire a player, I look up his birthdate. If he was born in baseball season, I look up what the Mets did the day he was born. When the Mets signed Max Scherzer, and I saw when he was born, I didn’t have to cross-reference the Mets’ result from July 27, 1984. He was born the day Doc beat the Cubs. Doc beat the Cubs like a drum virtually every chance he got, actually — 27-4 as a Met — but I didn’t require delineation. So when July 27, 2022, came into view and it appeared Max Scherzer would start against the Yankees on that particular Wednesday, his 38th birthday, I knew in advance what would happen.

Max Scherzer would live up to his purpose and help the Mets win the game. It was the game he was born to wrap his mitts around. At least until his next start.

Max threw six pitches in the first inning at a sold-out Citi Field. He registered three flyouts, retiring DJ LeMahieu, Aaron Judge and Anthony Rizzo in order. You look at those names and a run has already crossed the plate most nights. But then you look at Max Scherzer’s name.

On the day that Max was born, the K cards came together… Pete Alonso’s name and swing were good for a leadoff homer against Domingo Germán in the second. Francisco Lindor, who plays as if he circles the Subway Series in his day planner every January 1, provided a second run by driving in Tomás Nido from second in the third. Nido’s purpose was catching Scherzer. Anything he does with a bat is a bonus. A second run is a bonus sometimes when the Mets decide their ace pitcher can do it all. Two translated as twenty the way Max was going. He wasn’t dominant along the lines of 19-year-old Gooden. He was dominant along the lines of 38-year-old Scherzer. Two walks, five hits, a “mere” six strikeouts in the eyes of whoever will never be able to watch an all-time strikeout artist and not think of the K Korner, especially when the pitcher is Scherzer and the whiffer is Judge (indeed, three of those Ks were foist upon Hammerin’ Yank Aaron). Most importantly:

000 000 0Seven innings for Max, seven zeroes. One run fewer than Doc allowed over eight the night Max was born. Also one fewer inning pitched. Even when Doc was 19, men were men and all that. Gooden was from what was left of that breed that expected to go nine. It was well after Koufax and Gibson, but not far removed from Seaver and Carlton. “Hold on, big boy,” Davey Johnson said he had to tell his phenom when he reached the decision to pull him in favor of Orosco once Cubs manager Jim Frey sent up lefty pinch-hitter Thad Bosley to lead off the ninth. “You’re coming with me.” Gooden batted. Gooden strode to the mound nine times. I don’t know if men were men, but my goodness, pitchers like Gooden were everything.

I was pretty certain Max Scherzer wasn’t going to get anywhere near the mound in the ninth inning on July 27, 2022, because that hardly ever happens anymore, no matter that your name is Max Scherzer and your credentials are Max Scherzer’s. But after revisiting the events of July 27, 1984, in advance of Scherzer’s start, and as I considered the more than one inning apiece pitched by Adam Ottavino and Edwin Diaz on July 26, 2022, I sorely wished Buck Showalter would give Max the slightest nod toward the field after the Mets batted in the seventh. Scherzer wouldn’t need more than a hint. Hell, Buck wouldn’t have to finish his nod before Max would be throwing to Nido.

Again, however, that’s not how it works. Nor are two runs that look so mighty when Max is on the mound, even against the Yankees, look like much when it’s anybody who isn’t Ottavino or Diaz facing them in relief. Sure enough, the so-crazy-it-might-work experiment of handing David Peterson the eighth inning imploded on contact, first figuratively via a four-pitch walk to Anthony Rizzo, then on the fifth pitch of the inning, a two-run gopher ball to Gleyber Torres. All that Gooden-Scherzer symmetry was suddenly relegated to footnote status unless Showalter was hiding somewhere within his windbreaker a rested reliever who could avoid any further mess.

Son of a Buck, the manager had an answer. After Peterson recovered just enough to strike out Matt Carpenter, Showalter called on Seth Lugo, who used to inspire all the bullpen confidence circa 2019, when the question wasn’t why Seth Lugo? but why Seth Lugo for only one inning? Vintage Six-Out Seth Lugo returned to form of yore by getting Josh Donaldson looking and Aaron Hicks swinging. Then, after the Mets continued to honor their pact of non-aggression where scoring was concerned in the bottom of the eighth, Lugo continued to pitch, bringing his returned form with him. Two outs at the bottom of the order, a single to LeMahieu and, oh joy, Judge up as the potential destroyer of worlds.

Except Lugo grounded Judge to short, forcing LeMaiheu, and if the Yankees couldn’t take advantage of a ninth inning in which Diaz’s trumpets didn’t blare, maybe we wouldn’t have to see extra innings. Maybe, instead, we’d watch Eduardo Escobar see his offensive shadow for a change and belt a double to deep left; Nido unearth the ancient art of the sacrifice bunt to put Eduardo on third with less than two out; Brandon Nimmo not do exactly what we wanted but not do anything detrimental (he reached on a comebacker that Wandy Peralta couldn’t quite tame); and Starling Marte do exactly what we wanted.

It took two pitches for Marte to send a single into left and Escobar home from third. A tense Wednesday night tie became a jubilant Subway Series sweep. Just like that, the Mets were 3-2 winners and possessors of a record of 61-37, the second time in 2022 they’ve been as many as 24 games above .500. Coming into the two-game intracity set, they were 59-37, the exact same mark the 1984 Mets had on July 27, 1984. As noted, the Mets fell from 59-37, taking our division championship dreams with them, at least until that December when Walt was traded to Detroit for Howard Johnson, and Fitzy was part of a package going to Montreal for Gary Carter, and we got back to dreaming suitably big mid-1980s dreams.

These first-place New York Mets keep building on what they’ve accomplished. They’ve been doing it from Day One of this season. They’re still doing it. They have to keep doing it, not only because the second-place Atlanta Braves, currently three games behind us, are as formidable an opponent as the 1984 Cubs or 2022 Yankees, but because there’s little chance somebody will stand before a throng of Mets fans 38 years from now and wax rhapsodically about the 2022 Mets who showed what a group of talented athletes — some if not all young, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed — they were unless there’s a payoff in October.

We don’t need to wait until 2060 for history’s judgment. To be remembered as something special, this team can’t peak in late July. This year hasn’t emerged as the start of something big. It is something big. A helluva spring and summer isn’t gonna cut it without a fall to match. Not after last year’s transitory occupancy of first place diminished for many among us the meaningfulness of leading the NL East prior to the completion of 162 games. Not after so many years since 1984, 1985 and 1986 when, honestly, there haven’t been many years like 1984, 1985 and 1986. A few good ones here and there. None presented in quite so satisfying a sequence. Maybe you can catch the rising stars only once in a lifetime.

Right now, you’ll never forget what it was like for Max Scherzer, Pete Alonso, Francisco Lindor, Seth Lugo, Eduardo Escobar, Tomás Nido and Starling Marte to have gathered their forces and beaten the Yankees in dramatic fashion. Whether you’ll more than dimly remember it a year or ten from now depends mostly on the next series in Miami; the series after that in Washington; what happens by next week’s trade deadline; the respective recoveries of James McCann, Trevor May and, oh yeah, Jacob deGrom; the five-game series at home against Atlanta; and then everything after that. It’s 38 years since 1984, light years beyond taking sentimental solace in the nicest of tries.

In a way, that’s too bad. In another way, that’s baseball like it oughta be.

A new episode of National League Town, pretending it knew all along the Mets would sweep the Yankees, is out now. Listen to it. It’s fun.

by Jason Fry on 26 July 2022 11:49 pm Look, I’d be happier never playing the Yankees.

First off, I don’t like interleague play and wish they’d do away with it. But there’s having to play, say, the Angels and there’s having to play the Yankees. And with the latter, there’s just too much stress. One’s living room feels like a psychiatrist’s office; being at the stadium feels like being cooked in a cauldron.

I know baseball games can be stressful. Hell, that’s part of the fun. But the Subway Series is like dropping a chunk of the playoffs into July — and I like my October anxieties to stay in October. Even a barn-burner of a regular-season game against the Braves or Phillies has some fun involved in it, but playing the Yankees is no fun at all. The losses make you want to go outside and lie in the road. The wins feel less like victories than surviving. A lopsided defeat feels like a hanging; a laugher feels like a karmic IOU that will come due at the most devastating time.

(I’m aware all of the above is peak Old Man Yelling at Cloud. I know interleague play is here to stay and about to get supercharged and Mets-Yankees games will be red-letter events on the regular-season calendar forevermore. I know, but I don’t care. I’m 53, which isn’t quite old-man territory but sure isn’t the first flush of youth. And have you looked closely at the clouds? Because some of them are real assholes and could use a good talking to.)

Joe Torre, of all people, came the closest to how I feel about the Subway Series. It was Torre who famously remarked that “when we lose I can’t sleep at night. When we win I can’t sleep at night. But when we win I wake up feeling better.”

(I’m pretty sure he said that while managing the Yankees, but since he did manage both New York clubs, let’s claim it for his tenure with us.)

The beginning of Tuesday night’s game found Emily, Joshua and me in a loud, crowded pub in Portland, Maine. There were no Mets or Yankees on the TV — this is Red Sox country, after all — so we fired up MLB.tv on my phone and propped it on the table, only to watch Aaron Judge take Taijuan Walker over the fence for a first-inning homer, followed by Anthony Rizzo sending the very next pitch to the same fate.

Not exactly ideal — it looked to me like Walker was (understandably) overamped, which caused him to overthrow and deliver pitches that flattened out. But a baseball truism is that you never know how the other guy is going to look coming out of the gate, and Jordan Montgomery had immediate problems.

Those problems started with Brandon Nimmo, who harried Montgomery through a pesky nine-pitch at-bat — one that ended with an out, but forced Montgomery to dip into his reserves and show most of his arsenal to the Mets hitters. Starling Marte hit a line-drive homer to cut the deficit in half. Francisco Lindor doubled and Pete Alonso slapped a changeup at the bottom of the zone up the gap for another double, tying the game. Two batters later, Eduardo Escobar connected and the Mets were up — improbably and marvelously — were up 4-2.

They were up 5-2 after some Yankee misadventures in the field, with Walker in constant trouble but somehow surviving, while the Mets failed to break through against a parade of apparently untouchable Yankee relievers I’d never heard of. (Probably not news, but that’s a really good team over there.) We left the pub and got in our rental car as Rizzo batted with the bases loaded and the Yankees within two. Wayne Randazzo’s radio call sounded like doom until the second the ball nestled safely into Nimmo’s glove at the fence — and when I finally saw the replay, I held my breath all over again.

Walker settled in to give the Mets some length, and then Adam Ottavino got through the seventh in large part thanks to Tomas Nido throwing out Rizzo on the back half of a double steal. (Rizzo was somehow in pretty much every pivotal moment of the game.) Ottavino yielded to Edwin Diaz with two outs in the eighth and the tying run at the plate — feast-or-famine pinch-hitter Joey Gallo, whose presence had the Yankee fans at Citi Field muttering even before Diaz struck him out. Jeff McNeil chipped in a desperately needed insurance run to bring Diaz back on stage with a three-run lead; Diaz survived an infield hit and his own error before blowing away potential tying runs Rizzo and Gleyber Torres for the win.

The Mets won. I survived. And tomorrow we … have to do this all over again? I won’t sleep, but at least I’ll wake up feeling better.

by Greg Prince on 25 July 2022 2:24 pm It’s Sunday night. The Mets haven’t won in more than a week. As if that’s not enough of a shame, our greatest miracle has been celebrated anew, and this is how our team responds in the present? What we could really use is a nice offensive explosion while everything is looking listless and limp, maybe a five-run inning leading to an 8-5 slumpbusting win.

Eerie how history can rhyme sometime.

The parameters of the lede paragraph were all in place on this most recent Sunday night, but it was also the situation a little over three years ago. On June 30, 2019, the day after the Mets celebrated the 50th anniversary of the 1969 world championship, they were aching for a win following a loss in Chicago; four in Philadelphia; and two more at home to Atlanta. (They’d also inadvertently killed off two members of their first champions in a flub-flecked In Memoriam reel and had to walk back Jason Vargas’s threat of physical harm to a reporter.) The abyss-tumbling even started at Wrigley, just as it had this summer, though then there wasn’t an All-Star break to consume the middle portions of those 2019 doldrums. ESPN came calling, anyway, somehow thinking that those Mets were national-audienceworthy. The Mets, as if to make it up to their inconvenienced fans, handed out replica 1969 World Series rings to their earliest arrivers.

No chance loomed that the 2019 Mets would be enlisting jewelers to manufacture real things based on how the club kept playing through the middle of the eighth, trailing the dreaded Braves, 5-3. Yet there the Mets were, on the field, unaware their season was essentially over. And in the bottom of the eighth, there was a home run, a couple of other big hits, a three-run lead and, in the ninth, Edwin Diaz on to record three necessary outs.

On July 24, 2022, history chuckled at its rhyme. Well, I did. I was at that game three years ago, when, with the Mets mired in a seven-game losing streak and courting embarrassment everywhere they stepped, they snapped out of it. Todd Frazier led off that eighth with the precedent-setting homer and newly minted All-Stars Jeff McNeil and Pete Alonso delivered impactful blows themselves, each driving in a pair of runs. It was cathartic — because I could swear the Mets were never going to win again — and it was respectful. You don’t get swept by the Braves when you’re remembering 1969.

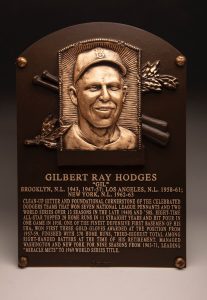

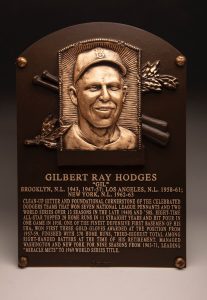

We couldn’t help but remember 1969 this Sunday three years later, not with Gil Hodges’s induction going final on the road in Cooperstown. You didn’t need to follow the out-of-town scoreboard to know it had happened. Thanks to ESPN’s machinations, the Mets’ first pitch was pushed to 7:08 PM, plenty of time to watch the immortality festivities. Usually I’d gripe at being subject to the indignities of Sunday Night Baseball. On this occasion, I was grateful for the lack of channel-changing. I could focus on Gil and every other honoree in the afternoon. I could worry about the Mets later.

Finally. When Gil was elected in December, I literally shed tears of joy. Then, when it was announced Buck O’Neil would be joining him, the parade of precipitation from my eyes intensified. No tarp was necessary. Let it rain. Baseball had waited too long to make things right. The wrongful drought was over. The eternity those who cared for Hodges, O’Neil and, for that matter, Minnie Miñoso, ended. Winter after winter, their families and fans searched for any clue that some committee would sign off on what so many baseball-lovers knew in their hearts, that these men were as worthy of recognition as any with whom they’d crossed paths or were denied access to competing against. The waits for Gil and Buck and Minnie made the Mets’ three-game losing streak versus the Cubs and Padres appear mighty inconsequential.

Not that losing three in a row (five, if you wish to punish yourself with the results of the Home Run Derby and All-Star Game) is a breeze. Nobody likes having to endure a staggering eight days between Met victories while the Mets sit mired in first place. Oh, the humanity. It was cause for dismay, perhaps discomfort, maybe a cue to press the silent alarm that sets off the panic button, but did you really think 2022 was all but over with more than two months remaining in the Triple Wild Card Era?

Don’t answer that question. I doubt I want to know.

Thank goodness that long, Metropolitan nightmare ended Sunday evening, mostly when the Mets poured five runs on the board in the sixth after doing nothing for the first five. Carlos Carrasco pitched credibly (he gave up nothing before exiting in favor of loosening Drew Smith’s arm) and Brandon Nimmo fielded wonderfully (he saved at least one run after Eric Hosmer unleashed his trademark awfulness on Smith in the form of an RBI double), but Met batting was merely for show. Not much of a show, either.

In the sixth, when I was ready to join the hordes believing the Mets would neither score nor win ever again, the 2022 team reminded us that they’re not too bad. Versus Joe Musgrove, Starling Marte walked, Francisco Lindor singled and that Alonso kid from three years ago blasted a home run that could have given Juan Soto a run for his Derby money, or any money awaiting Soto. Suddenly, the Mets had a 3-1 lead. Suddenly, a Met had gotten a big hit with runners on base. To quote Ben Fong-Torres in Almost Famous, “Crazy.”

Crazier, still, hustling Daniel Vogelbach crossed the plate for the first time as New York’s own, when a two-out Luis Guillorme fly ball to shallow left fell in front of a tentative Jurickson Profar. Vogelbach had walked, advanced to second on a friendly Mark Canha (possibly pronounced CAHN-ya) grounder and rumbled 180 feet as fast as he possibly could, presumably as fast as he grabbed the first flight out of spiritually eliminated Pittsburgh to join a pennant race. Then, as long as miracles were in the air, Tomás Nido, he of the perfectly reasonable “whaddaya mean Buck didn’t pinch-hit for Nido?” carping roughly 24 hours earlier, doubled home Guillorme.

It was 5-1 en route to 8-1 en route to 8-5 after the Mets had spent the week either trailing or idling. It was enough to allow for a bead of sweat to be dabbed from the forehead, even as the relievers meant to mop up spilled their soapy-water buckets. Newly assigned David Peterson gave up a run in the eighth and Joely Rodriguez…well, let’s just say he hasn’t been a Joely good fellow of late. In the ninth, the lefty less-than-specialist allowed four Padres to reach base and two of them to score without recording an out. Rodriguez wouldn’t see a fifth Padre. Instead, we’d see Diaz, and Diaz would see to the end of things, no discernible harm done.

Dab your forehead again. The Mets not only didn’t lose, but they increased their lead on the Braves back to a game-and-a-half, although you’re already sure the team that’s led the division without pause since the second week of April courts doom every instance it swings and misses. I’m susceptible to Last Thing I Saw Syndrome, too, and as I hadn’t seen a Mets win in two Saturdays by Sunday night, I was ready to surrender to my bleaker instincts when it was Padres 1 Mets 0 in the middle of the sixth, never believing it could be Mets More, Padres Less by the end of the ninth.

I wonder how I would have handled July heading into August of 1969 with that kind of attitude. I’d like to think my manager wouldn’t have allowed me to start thinking the worst.

The Mets of 53 summers ago actually sagged in the middle. Their dip amidst miraculous doings is usually handled in a lone anecdote. They were getting their posteriors whupped by the Houston Astros in a doubleheader at Shea on July 30; Cleon Jones looked slower than Daniel Vogelbach going after a ball; and Gil Hodges sternly walked to left field to simultaneously remove Cleon and send a message to his teammates. Soon after that, the Mets more or less took off toward their destiny. With their manager guiding them to a better attitude, nothing could stop them from reaching highest altitude.

Which sounds great, though from the doubleheader of July 30 up to Woodstock weekend, there came no sun for the Mets. It took the expansion Padres coming into town while Richie Havens and everybody else got playing in Bethel to lift the Mets from the mud. We were 9½ out as late as August 14; we concluded regular-season proceedings 8 up on October 2. And that was just the Miraculous appetizer.

But let’s not forget that sag. As my late friend Dana Brand put it in Mets Fan, following his reliving and reveling in the second-place Mets’ unlikely July triumphs over Leo Durocher’s first-place Cubs, “Then it all collapsed. It had to. How could it possibly have happened? How could we have dared to hope for this? By mid-August, after a rough month [… t]hey were in third place, as the Cardinals had finally woken up. And the Pirates were gaining. We would probably finish fourth. It was okay. This season had been more fun than any Mets season had ever been. I was crushed. I was only 14, but I knew something about how the world worked.”

I didn’t. I was 6. I was only waking up to the Mets that summer. I place the opening of my eyes as somewhere between Woodstock overwhelming the New York State Thruway and the LOOK WHO’S NO. 1 shoulder-tap on Shea’s massive scoreboard. I don’t remember anything specific before the Mets chasing down and passing the Cubs as first grade was starting. I didn’t know that the Mets had never won many games let alone any pennants before 1969. I just knew they were winning a bunch now; and everybody said it was “Amazin’” without irony; and I wanted to be a part of it; and that I never stopped being a part of it.

Somewhere in those first weeks of awareness, I came to know the name of the man who was steering the ship. It was Gil Hodges. I didn’t know about his platooning or his quiet leadership or his willingness to tell his best hitter, in so many words, maybe you ought not be out in the field if you can’t chase after a ball properly without making more of a scene out of it than he had to. I certainly didn’t know about the playing career that preceded his becoming manager of the Mets, or that it took place in Brooklyn, where my family lived before I was born, and that he and his team in that borough were glorious and that everybody revered Gil Hodges. The reverence I’d figure out by 1970. I was only 7, but I knew something about how the world worked.

Fast-forward, as one will, to the present, and there was Gil Hodges being inducted into the Hall of Fame. It had been talked about since he was still alive, which was a mighty long time ago. Gil began appearing on Hall of Fame ballots in the winter of 1969, before the season that would define him and the Mets and this Mets fan here. He didn’t make it the first time he appeared. Or the second time. Or the third time. There was enough time then for his young daughter Irene to ask her dad if he thought he’d ever go into the Hall of Fame.

“No. Never,” was Irene’s father’s emphatic reply. She asked why. “Those are all great players in there. I’m not even close,” was his humble explanation.

Forgive the heresy, but Gil Hodges was wrong. A lot of people continued to think he was wrong, and now there’s a plaque definitively refuting his self-assessment. Irene and her siblings were in Cooperstown Sunday to shepherd the plaque to its final station, in the Hall of Fame gallery. The daughter gave such a wonderful speech in honor of her father. As the son of a Brooklyn schoolgirl, I could hear the Brooklyn schoolgirl in Ms. Hodges throughout her presentation. She’d been assigned this report months ago by the Golden Era Committee’s vote, in her heart most of a lifetime ago, it is safe to infer. Just before she spoke, Tom Verducci on MLB Network explained how it came to be that Irene rather than brother Gil Jr. or sister Cindy gave the official address. Gil Jr. told Tom that Irene said, “Mine,” and that settled it.

Good a call as any if you saw it, and because the Mets didn’t play until Sunday night, you could see it live without conflicting interests. “Today,” Irene said as she wrapped up a review of her father’s career, life and the impact it had on others, “I am especially happy for my mother,” Joan Hodges, who was watching back home in Brooklyn because traveling is too much of a burden at her age. “When the call came from the Hall of Fame, and I heard, ‘this is Jane Forbes Clark, and it is my honor…’ I began sobbing probably as much as I did when I lost my father. I was so beyond happy for him, and even thrilled that my mom, at 95, and would be able to hear this news.” Irene was too much of a class act to note that had this decision been certified in a timelier fashion that her mom could have been in Cooperstown speaking herself. One assumes Irene had the value of grace instilled into her at an early age by both or her parents. Her father, after all, “would only do what he thought was the right thing. That was my dad.”

I thought it was telling that the four living 1969 Mets who made the not easy trip upstate to watch Irene Hodges accept on behalf of her dad were four Mets who could have spent the last fifty-plus years nursing grudges. Ed Kranepool lost playing time to Donn Clendenon after having been spotlighted as the Mets’ first homegrown star. Art Shamsky wasn’t the regular he looked forward to being when he was traded from Cincinnati. Ron Swoboda was prone to chafe at authority. And Cleon Jones was taken out of a game against Houston after not going hard after a batted ball, maybe because the Mets were getting blown out and it didn’t seem worth it or maybe, because Cleon says, his leg was bothering him and his manager recognized that. Yet each man won a championship by overcoming their initial differences with Gil Hodges and accepting the leadership Gil Hodges offered them and, literally to this day, each man will tell you the main reason they earned a ring that could be replicated as a promotional giveaway was mainly because of Gil Hodges. They have nothing to gain in 2022 by continuing to revere Gil Hodges. They do it because they think it’s the right thing.

In Flushing, in the aftermath of the Hall of Fame induction of the late Gil Hodges and six other worthy honorees (the late O’Neil, the late Miñoso, the late Bud Fowler, the advanced-aged Jim Kaat and Tony Oliva and the robust David Ortiz), the Mets gave out Gil Hodges bobbleheads to the first 25,000 through the gates at Citi Field. I imagine it complements the 1969 replica ring nicely for those who attended on both that Sunday night three years and this past Sunday night. In 1969, Gil called the likes of us who buy tickets and cheer our heads off “beautiful fans” for our support, given to his team that year all year, even in the middle of summer when they sagged.

I don’t know how beautiful we are on a given day in the midst of a given losing streak. I do know it’s beautiful that Gil is enshrined where he is enshrined.

by Jason Fry on 23 July 2022 11:31 pm The quickest way a team can demoralize its fanbase? OK, actually it’s to have an arsonist bullpen that routinely sets fire to victories so that they burn down into defeats.

But the second quickest way? It’s to routinely get great starting pitching and have it undone by an absolute lack of hitting. Which is something the Mets have offered us way too often of late.

Chris Bassitt was the latest victim, undone by a single bad pitch that led to a 2-0 Padres lead and a 2-1 Padres victory. Manny Machado‘s home run erased the fact that Bassitt struck out 11; ultimately, it also erased the Mets’ 1.5 game lead over the Terminator-like Atlanta Braves, now just half a game back after spanking the hapless Angels.

Half a game back as in could be half a game ahead tomorrow, but we’ll leave that bit of angst for a future post.

OK, I know what you’re wondering why I haven’t addressed yet. Yes, home-plate umpire Jim Wolf missed an 0-2 pitch on Machado that was clearly inside the strike zone. Instead of being out, Machado got another pitch — one he turned into a souvenir.

But these things happen. Bassitt missed his target by more than a foot, crossing up the umpire, and was philosophical about what had happened in postgame interviews: “It’s part of the game. It’s OK that he missed it, I just gotta make a much better pitch the pitch after that. That was a terrible pitch.”

The accountability is welcome, but more to the point, a guy who makes one bad pitch while fanning 11 shouldn’t be on the losing side of the equation. If that happens, the raised eyebrow shouldn’t be directed at the home-plate ump, or God, or anyone except his teammates — the ones apparently going to the plate holding their bats upside down.

The Mets put the leadoff runner aboard in six of nine innings, but said table-setting led to a run exactly once — a ninth-inning flurry that was more impotent pique than righteous uprising. It was a quietly infuriating night, emphasis on both qualifiers.

There have been too many of those double barrels — quiet bats, infuriating lack of results, great starting pitching gone by the boards.

All is not lost, of course. The Mets are still in first place, however tenuous their hold on said perch may have become. The team will almost certainly look different by Aug. 2, and in ways that involve more than importing various Pittsburgh Pirates. The players who remain after Aug. 2 will (presumably) revert to the mean and start putting up numbers more in keeping with what adorns the backs of their baseball cards.

But it would be nice if these things happened soonest. Because what’s happening now isn’t cutting it. It’s … well, quietly infuriating pretty much sums it up, doesn’t it?

|

|

Vin was every generation. His status as the elder statesman who broadly bridged the millennia notwithstanding, whenever he was asked about what drew him to broadcasting, he was a kid again, inevitably describing (and always managing to relay it as if nobody had ever before inquired) parking himself under the radio speaker in his family’s living room, wishing to be bathed in the roar of the crowd. He followed the crowd to the source of that sound, out to the park and up to the booth, intent on telling the crowd what he and, soon enough with television, they were seeing. There were differences to calling a ballgame on radio and accompanying one on television. Nobody better understood that sometimes you’re the eyes for your audience and sometimes you’re chaperoning pictures, and that the pictures themselves can be left to tell key portions of the story best.

Vin was every generation. His status as the elder statesman who broadly bridged the millennia notwithstanding, whenever he was asked about what drew him to broadcasting, he was a kid again, inevitably describing (and always managing to relay it as if nobody had ever before inquired) parking himself under the radio speaker in his family’s living room, wishing to be bathed in the roar of the crowd. He followed the crowd to the source of that sound, out to the park and up to the booth, intent on telling the crowd what he and, soon enough with television, they were seeing. There were differences to calling a ballgame on radio and accompanying one on television. Nobody better understood that sometimes you’re the eyes for your audience and sometimes you’re chaperoning pictures, and that the pictures themselves can be left to tell key portions of the story best.