The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 17 June 2022 11:54 am Everybody misplaces their Mojo from time to time. In the summer of 1999, Austin Powers had to chase his Mojo all the way back to 1969. A couple of months later, the 1999 Mets’ Mojo experienced dizzying spikes and frightening declines despite Jim Morrison’s advice that it should keep on risin’. For a night-and-a-half in the middle of June of 2022, the current edition of New York’s National League franchise played as if disturbingly Mojoless.

There’d been a sloppy loss on Wednesday to the Brewers. That was one bad night at Citi Field, no biggie, unless one became two in a row, not in and of itself a biggie, either, but who wants to give such vibes a chance to resonate? My god, we were only four games in front of Atlanta! Thursday’s game dawned properly Metsian in the sense we’ve come to appreciate it this season: leadoff hitter Mark Canha walks to rev up the bottom of the first; Brandon Nimmo is hit by a pitch; after two outs, McNeil singles Canha home. The only surprise was that the Mets hadn’t mounted a larger lead than 1-0. Tylor Megill, who’d retired the Brewers in order in the top of the first, faced the minimum through three. Everything appeared SN — Situation Normal.

Then came the AFU that transforms a normal situation into a SNAFU.

The top of the fourth commenced with a Christian Yelich leadoff homer, but OK, that’ll happen. Megill struck out Willy Adames, yet normality was about to take it in the teeth. Rowdy Tellez singled convincingly, Luis Urias more so. Tellez, who doesn’t come off as the racing kind, raced to third as if imbued by the spirit of Mo Donegal. Andrew McCutchen walked. Sticky jam we faced, but Megill could get out of this.

Correction: Megill was simply out. The trainer was on the mound and Tylor was leaving after his second start since returning from the IL. Ouch! Word would come down eventually that Megill was experiencing discomfort in his right shoulder. When they delivered the news, SNY’s booth groaned. Like the difference between a dead arm and a sore arm (sore being more concerning than dead), discomfort, which doesn’t sound so awful to civilian ears, speaks volumes to those who understand the language of baseball most intimately. A pitcher needs his throwing shoulder to be comfortable.

In the meantime, Chasen Shreve came on to relieve with every base occupied and was greeted by a pair of grounders sporting 20-20 vision. They certainly had eyes, each ball (one struck by Omar Naravez, the other by Hunter Renfroe) plating a run or two. The Brewers suddenly led 4-1. Our starting pitcher was gone. Our usual starting right fielder, Starling Marte, wasn’t available after being hit on the hand the night before. Our usual starting third baseman, Eduardo Escobar, wasn’t around, thanks to a “non-workplace event,” a euphemism grim mainly for its vagueness. In the bottom of the fourth, the Mets attempted to rally the way these Mets do. McNeil walked with one out. Luis Guillorme singled with two out. Tomás Nido, quietly clutch, took an Aaron Ashby pitch to right. It was enough to score McNeil. It wasn’t enough for the normally infallible Guillorme to stop at second. He tried to take third on Hunter Renfroe’s arm. McNeil could have told him from Wednesday not to run on that limb. Guillorme ended the inning making the final out at third, just after Jeff crossed the plate. There was a replay review to confirm Luis’s faux pas. The crew in Manhattan must have fainted when it realized Guillorme ran into a fundamental mistake.

Now it was up to Chasen Shreve and whoever followed him. Shreve has his moments but also isn’t the first Met you think of when you conjure notions of length. With the DH rule ensconced, whoever was pitching could stick around a while. Except the Mets used their designated long man, Trevor Williams, the night before and sometimes you wonder how baseball gets from one game to the next with its bloated pitching staffs and its short benches yet often nobody to inhabit whatever role is most in need of filling. Opportunities to score more had gone by the wayside. Depth was shallow. Chasen Shreve was our immediate best hope as the fifth inning beckoned.

Mojo was elusive. But Shreve didn’t care. He popped up Yelich and struck out Willy Adames, then Tellez. We were still down by two. It only felt like more. Ashby comes back to the mound in the bottom of the fifth and walks right fielder Nick Plummer, who hit a big home run in late May and hadn’t done much since a second home run in slightly later May. Plummer’s ability to trot remained fresh, though. He got to do it on Mark Canha’s ensuing home run to center. Just like that, the Mets had tied the game. It only felt like they trailed. Just one of those vibes on one of those nights. A normal 2022 Mets affair tells you it’s only a matter of grind before our team of choice is out in front. I was frankly surprised they were no longer behind.

The Mets stayed tied with Milwaukee in the sixth. And the seventh. And the eighth. Seth Lugo was good for two middle innings of shutout ball. Drew Smith worked around a pair of baserunners. The Mets couldn’t do anything to any Brewer relievers after Ashby’s exit in the fifth, but not losing was a provisional victory. Not the same as a W, but no two wins are built exactly alike.

I’m not fond of the concept of teams stealing victories. I don’t mean teams stealing bases en route to winning, but the idea that they didn’t deserve to win the game they won. A win is a win; you won, you won. The game didn’t belong to the other team. It was up for grabs. For Thursday night, however, I’ll make an exception. The Mets stole themselves a win.

J.D. Davis led off the bottom of the eighth versus Brent Suter with a well-guided single through the infield. Guillorme’s ability to do everything splendidly rematerialized via contact on the eighth pitch of what might have been an epic at-bat, but what for Luis is business as usual. He put the ball in play, sending it to Tellez at first. Tellez sent it to the outfield, missing a potential forceout on Davis at second. Now we had runners on first and third with nobody out.

The heretofore unavailable Marte materialized. Can’t bat. Can’t throw. But the man can run. With a sac fly a possibility, Starling’s legs could make the difference. He pinch-ran for DH Davis. A pretty decent percentage move, I thought, despite the bench now being down to Patrick Mazeika and splinters should the bottom of the ninth be a factor. But one half-inning at a time.

Nido didn’t come through, but Plummer — don’t you love how now and then the fortunes of this particular team are embedded in names like “Nido” and “Plummer” and the fortunes aren’t necessarily dismal? — hit the ball to the right side. Good thing Marte’s speed is in the game, because the Brewers’ infield is playing in. Except Marte didn’t break, which wasn’t a crisis because Tellez, who fielded Plummer’s grounder, opted to attempt to execute a double play. He got one out, Guillorme at second. But after his initial hesitation, Marte streaked home. There was no double play. There was a Mets run. There was a Mets lead. It wasn’t exactly classic Mets magic, but in the inverse of now you see it, now you don’t, the Mets were ahead, 5-4.

I swear I didn’t see it developing. But then I did.

The top of the ninth fell to Edwin Diaz, and unlike most ninths of late, it almost tumbled down on his Sugary head. Renfroe led off with a soft single to center. Jace Peterson struck out, which is what you expect versus Diaz these days, but Tyrone Taylor, pinch-hitting for 2015 World Series villain Lorenzo Cain, lined a ball past first base. It wasn’t a classic double into the corner, but it did have tricky written across it every bit as much as it did “Robert D. Manfred Jr.” A skilled outfielder like Marte would catch up with it and get it in, but on Buck Showalter’s lineup card, Marte was listed as the DH who literally couldn’t hit. Lesser-known quantity Plummer was still out there. The collective brainpower of the Brewers — Renfroe taking off from first, third base coach Jason Lane and, presumably, manager Craig Counsell — decided pushing Plummer and the Mets’ defense to its breaking point was the way to go. They weren’t expecting two hits off Edwin Diaz. Why wait to find out?

So Renfroe, who’d thrown out two runners in two nights, concluded he was immune to the kind of defensive punishment he’d been administering. He kept chugging toward home. I started rewinding to 1999, not for Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me (one of the more disappointing sequels I ever willingly watched), but for another Mets-Brewers encounter that came down to baserunning in the top of the ninth. It was that doubleheader when Robin Ventura grand-slammed in both games. I was thinking about the opener, the only 11-10 win in Mets history, a contest that got put into the books for us because another Brew Crew baserunner, old friend Alex Ochoa, was trying to score the tying run and was clearly gonna be out. Watching then from the third base side of Field Level at Shea, I wondered what the hell was Alex was doing. He was gonna be out by the proverbial twenty feet. And he was. A kooky slugfest was over in our favor. Thanks, old friend!

Twenty-three years later, Renfroe didn’t appear to be indisputably doomed, but Diaz or no Diaz, his mission came into focus as an enormous risk, to put it kindly. Plummer handled his task, picking up the ball and relaying it to Alonso. Alonso, not always the first baseman of our dreams, continued the process as best we could wish. Pete’s throw found Nido on the third base side of home. It was a little high, but it was in plenty of time to nail Renfroe. Hunter made a good slide, and it necessitated a review, but the dude was out. He was going to be out before he slid, he was out when he slid, he was out after he slid.

The Brewers had only one out left to play with. They did have Taylor on third, and they did have former National League MVP Yelich coming up, he who had homered off Megill way back in the fourth, but Diaz was still Diaz. Three strong pitches, three strong strikes; our lion tamed their Christian.

The Mets’ Mojo returned intact, bringing a 5-4 win in tow. I was surprised it went missing. I’m not surprised it was rediscovered, as I was confident it hadn’t hitched a ride out of town, but I thought it might be AWOL a little longer than it was. Maybe it was just in hiding for a few innings. Mojo can be mischievous that way.

National League Town is simply happy the Mets are home for a spell. Relive a little 2005, a chunk of 2012 and a dollop of 1955, as well as all that 2022 has to offer, here.

by Jason Fry on 16 June 2022 1:14 am 7:10 Finish talking to a friend about an art project. Tired from packing ahead of a flight to Charlottesville. Time to watch some Mets baseball!

7:17 Jeez, David Peterson has already hit two Brewers. In a cheap horror movie there’d be some dissonant strings warning of bad things to come.

7:19 Luis Urias slaps a two-run single just past Francisco Lindor. Ugh.

7:19 Have my alarm set to remind me to get a Lyft to the airport. This is going to be a busy night after a busy day. It’ll be nice to have baseball as my companion. Well, unless the Mets get slaughtered.

7:20 Peterson finally throws a slider. That’s good! He throws another one and nearly hits Keston Hiura with it. That seems less than good.

7:21 Oh, a generous strike three call. We’ll take it.

7:25 Oh shit I forgot we’re facing Corbin Burnes. He’s good. He’s really good.

7:30 Starling Marte singles and the Mets are pecking away at Burnes.

7:36 Pete Alonso drops an RBI single down the line … oh wait, no, it’s a foul ball. Oh cruel fate.

7:39 Hiura makes a nifty snag to deny Jeff McNeil and the Mets are turned aside in the first. But they forced Burnes to throw a lot of pitches. Maybe it’s not time for despair quite yet.

7:44 Peterson is somehow not killed by a Christian Yelich line drive. Both Yelich and Patrick Mazeika instinctively duck in sympathy. Oof.

8:01 And Peterson has lost the strike zone. Not momentarily misplaced it, but in a coal mine without a lamp on a moonless light lost it.

8:02 Mets turn a 5-4 double play. Nice! Could have been a triple play except the ball was hit too slowly. Don’t get greedy.

8:17 Peterson is nearly killed by a second line drive. Yikes!

8:19 McNeil can’t find the grip on a relay and throws the ball 10 feet wide of Pete. It’s 3-0 Milwaukee.

8:21 A 6-6-3 DP, as Lindor is covering second and in the absolute perfect spot to turn a single up the middle into a rally-killer. Yelich is like, “so that happened.” He’s veteran enough to have Seen Some Shit.

8:24 Remember I only heard Brandon Nimmo‘s catch last night, so cue up the video. Yep, pretty nifty.

8:30 Uh-oh, time to head to the airport. Wait, what am I forgetting? Oh yeah — you still have to actually a call a Lyft for one to show up. Do I have to do everything?

8:31 McNeil homer! Keep hope alive!

8:35 In the Lyft. We have lyftoff. That has to have been an ad campaign at some point, right?

8:36 Peterson has thrown his last pitch.

8:39 Hmm, have I seen Jake Reed pitch this year? No, I was yeehawing and boozing it at my high-school reunion when he made his season debut. Do I remember him from 2021? Vague impression is that he was hairy and a sidearmer.

8:41 Howie Rose confirms: sidearmer. Don’t know about the hairy part.

8:42 Howie talking schedule. Sixty-six games into the season is still too early to have to deal with the Marlins. I would prefer to play them never. Never would be ideal.

8:43 Was talking with my boss about the fact that the Mets could add two phenomenal midseason pickups without spending a penny or parting with a single prospect. It’s even true!

8:44 Jake Reed is doing things he’d prefer I didn’t remember.

8:46 That’s right, it’s the anniversary of the Tom Seaver trade. I hope some bat-winged spawn of Hell is giving Dick Young and M. Donald Grant an extra turn on the spit to mark the occasion.

8:47 Howie tells a funny story about Maury Allen and Young hating each other and someone asking Allen what he was doing at Young’s funeral. Allen said he was there to make sure Young was dead. I admire a good grudge.

8:49 Don’t fuck this up, Jake Reed.

8:52 Jake Reed fucks this up.

8:54 As it happens, I’m looking through the Lyft’s windshield right at Citi Field. Somehow still haven’t been this year. Need to fix that. But not brokenhearted I didn’t fix it tonight.

9:09 Through security and at my gate. There was a lot of fucking up over at Citi Field while I was on a lengthy journey through the new Terminal C. It’s nice.

9:10 I’m looking across the bay at Citi Field. I can see the scoreboard and discern that Mark Canha is up. That means the radio feed is behind, as the Mets still aren’t out of the inning from Hell in my ears. All my time codes will be slightly off. I can live with that.

9:11 I’ve lost track. I think it’s like 43-1?

9:16 Beginning to think we’re not going to win this one.

9:17 If I agree to watch “The Old Man,” will WCBS stop saturating Mets’ broadcasts with ads for it? Christ on a crutch. And I like Jeff Bridges!

9:26 Nimmo triple! This pig has some lipstick!

9:30 Boarding. Marte just got hit in the hand. Great. A question I hope isn’t relevant: Does the hamate bone have an evolutionary purpose, or does it exist solely to sideline baseball players for six to eight weeks?

9:36 McNeil drives in a run and is inexplicably thrown out at second to squelch a modest threat. Seriously? I can imagine Buck Showalter glowering at McNeil from the dugout.

9:37 Great catch by Nimmo at the fence. Well, none of this is his fault.

9:38 A couple of hours ago I was scheming about leaving my phone on during taxiing so I could hear as much of this game as possible. Think I can let go of that idea.

9:39 Good Christ it’s only the seventh. And of course the Braves are winning again. Less scared than annoyed about that last part. For now.

9:44 The boarding door is closed. I’m still listening to the game because I am a dangerous outlaw.

9:48 Huh, it was Canha who figured out Taijuan Walker was tipping his pitches. That was mildly worth waiting for.

9:50 And Luis Guillorme hits into a DP. I guess it’s a sign of a good season that I’m disappointed.

9:52 C’mon Nimmo, put a little more lipstick on this pig.

9:54 Nimmo Ks. Time to turn off my phone I guess.

10:06 Not going anywhere so cheating again. The game has not gotten better.

10:10 Pete flies out. My plane is moving. Bye again.

10:12 Wait we’re sitting around again. Weights and balances, whatever that means. The captain sounds disgusted.

10:14. Taxiing. Fuck it, will keep my phone on. If the plane crashes, rat me out to the FAA. Oh wait, if the plane crashes no one will ever read this.

10:16 They should have made the whole pen out of Joely Rodriguez. Whose only baseball card is from Topps Total and somehow basically unattainable. This annoys me.

10:17 Oh God another ad for “The Old Man.” I’m sorry, I’ve learned my lesson, I’ll turn off my phone.

11:09. Landed in Charlottesville. Did they win?

11:10 Shockingly enough, they did not.

by Greg Prince on 15 June 2022 12:28 pm As he reintroduced viewers to Citi Field, Gary Cohen channeled (not Dr.) Bob Harris by calling Tuesday in New York one of the Ten Best Days of the Year weatherwise. Of course nobody keeps track of the “best” days by weather nor might any two people agree on what precisely confers such status on a given day. Maybe Tuesday was too warm for your taste. Maybe it wasn’t hot enough. Maybe you prefer a little drizzle in your life.

When Tuesday night’s game was over, I found myself thinking I’d just seen one of the best Met wins of 2022, though, honestly, I’ve had that sensation after most every win this year, not just the certifiable Mets Classics-in-waiting. The previous homestand encompassed six wins that didn’t feel perfunctory. The long and winding West Coast road trip produced the best 5-5 mark any team has posted in recent memory. The losses hardly stung — not a nightmare blown save among them and every frightening injury mended before the flight east — and each win tangibly elevated the Met zeitgeist between yawns. Serve was held effectively and effusively, and now we’re done with trying to stay awake for nocturnal transmissions for quite a while.

This is not just a team that wins substantially more than it loses. This is a team that satisfies with practically every win. The most recent one-of-the-best wins of the year, the 4-0 blanking of the Brewers with which the Mets rechristened Citi Field after it appeared they’d abandoned New York for California, had a little something for every type of baseball aficionado.

Do you savor sound starting pitching? How could you not embrace Chris Bassitt’s eight frames of zeroes? Appreciate redemption stories? You got Bassitt shaking off the recent uncharacteristic difficulties that had dogged him for a few starts. A fan of personal growth, are you? Bassitt explained after the game that he had failed to connect with his catchers, so he spent the prior week really getting to know Tomás Nido. Their newfound simpatico was apparent in the bottom line: no runs, three hits, one walk and a locked-in Chris.

I’ve noticed Bassitt bounces off the mound after every strikeout or perceived third strike, whether it’s called or not. Like every time. I get the idea that Bassitt, even for a starting pitcher, likes his routine the way he likes his routine. Not everybody can be a Flexible Fred if he’s gonna be his best. Remember how Max Scherzer zoned in on his warmup process to such an extent that he left a Japanese diplomat standing off to the side of the mound, depriving the visitor of ceremonial first pitch honors? That’s starting pitchers for ya, sometimes. For Bassitt to take off his blinders and discern why everything wasn’t bouncing his way the way he himself bounces off the mound showed a pitcher getting the most out of his thoughts as well as his arm. Good for him. Good for Nido meeting him halfway or however much of the distance was necessary so they could constitute a team within a team. Mostly, good for us.

Defense helped Bassitt, and who doesn’t love sweet leather? Brandon Nimmo flew through the air with only a modicum of ease in the third to rob Hunter Renfroe. Luis Guillorme leapt to the shortstop side of second to touch off a balletic beauty of a 4-6-3 DP with Francisco Lindor and Pete Alonso in the sixth. If they still printed tickets rather than doing ducats electronically, they’d have to put Luis’s face on them, for he and his glove are truly worth the price of admission. The Mets made three double plays in all. Nido wasn’t the only one ready to bail Bassitt out of hot water.

Baserunning when done well is fun, right? How about Starling Marte, he of the heretofore day-to-day quad, tagging up from first and taking second on Lindor’s fly to deep left? Baserunning isn’t only in the legs. Marte used his eyes and sense of the situation and discerned he could advance ninety feet on the throw Christian Yelich was about to unleash. The Mets were up, 3-0, in the fifth, and the runner was now in scoring position with two out. That thing about “scoring position” is sometimes literal. Pete lined a rope into center that easily sent Starling home. That’s a run our right fielder’s entire body and mind brought with him.

The first three runs of the night were evidence of the Mets’ phrase of choice, the grind. Nimmo worked Adrian Houser for nine pitches right out of the gate and earned a ringing double. Marte got a little lucky on a grounder to the right side that couldn’t advance Brandon but also couldn’t be picked cleanly by any Brewer in the third-short neighborhood. Lindor couldn’t move either of them up a base, but it’s like what they say about the weather in some places: if you don’t like a Met making an out with runners on base, wait a minute and the forecast will change. Alonso was up next and he delivered a single to plate Nimmo and push Marte to third. After a wild pitch allowed Starling to ease on past the plate and Pete to land on second (scoring position), Jeff McNeil made exactly the contact he needed. It was an infield hit nobody from Milwaukee could effectively lay a mitt on, and by the time it was corralled, it went for a double. Pete could only get as far as third, but that was OK, because there was still only one out, and all it would take was a deep enough fly ball to score him. Oh, look — Eduardo Escobar just hit a deep enough fly ball to score Pete Alonso.

So that was the 3-0 lead after one that became 4-0 after five that became the sovereign protectorate of Chris Bassitt through eight until it was handed off to Drew Smith, who pitched more like the Drew Smith we adored in April this June night ninth. With little fuss but a whole lot fabulous, the Mets were again winners.

It was one of the best feelings of the year.

by Jason Fry on 13 June 2022 1:43 pm OK, so Sunday’s 4-1 victory over the Angels wasn’t the most memorable of ballgames — no crazed rollercoaster of lead changes, indelible highlights or controversies. But it was satisfying nonetheless: a trim, tidy baseball game, easy to admire if not necessarily one to commit to the top shelf of memory.

The Mets got a couple of big hits in long balls from J.D. Davis and Pete Alonso and a little help from the Angels’ defense in securing the win. The most interesting part for me, as the game unfolded, was the switch Taijuan Walker figured out how to throw. Walker barely survived a difficult first inning, surrendering four hits and not eliciting a single swing-and-a-miss from the Anaheim hitters. But before the second he made a mechanical adjustment that kept him from tipping his pitches, and holy cats did it ever work after that — the swings and misses came in bushels after that, with Walker recording 10 strikeouts in all.

The other moment that will stick in memory was an irresistible one: With one out in the eighth, Mike Trout came to the plate as the tying run. Buck Showalter excused Seth Lugo further duty and brought in Edwin Diaz. Now, terabytes of pixels have been spilled about the modern game since Tony La Russa made relief roles far more rigid* (and games far more turgid) as skipper of the A’s a couple of baseball generations ago. For a long stretch closers became cosseted creatures, used to working a lone inning under conditions that were the baseball equivalent of a semiconductor clean room. Should something go amiss, it wasn’t the fault of the closer but some violation of unwritten but deeply understood agreements about the closer’s working conditions — he was pitching in the wrong inning or had warmed up too much or warmed up not enough or had been spooked by inherited baserunners or one of 50,000 other things.

This bizarre orthodoxy has crumbled somewhat in recent years, and in the last week or so Showalter has been one of those chipping away at it, going back to the once not so strange idea that your closer should be facing the most dangerous enemy hitters at the game’s break point, rather than automatically being the ninth-inning caboose. Diaz arrived in the eighth against the Dodgers last week; on Sunday there he was in the eight to face Trout.

A closer who combines 100+ heat and a killer slider against the man who may be the best position player in history: How do you resist that confrontation? Even better, it turned out swimmingly for the Mets: Diaz alternated a slider and a fastball to get to 0-2, threw a slider low and outside to confound Trout’s approach, and then finished him with 99 MPH a bit upstairs. That’s been the way to get any hitter out for a century, and a reminder of just how hard baseball is, even for the likes of Mike Trout.

Diaz walked Anthony Rendon before fanning Jared Walsh to end the threat, then came back out for the ninth — which could have been flagged as a crime against closer rules. But he was unperturbed, striking out Matt Duffy, old friend Juan Lagares and ancient nemesis Kurt Suzuki to seal the victory. (If Trout was the marquee matchup, Diaz facing Suzuki was the one that made my soul curl up and blacken a little.)

Victory upon victory: The Mets are done with the West Coast, with their 5-5 record feeling like a grand accomplishment. They and we may now resume our more normal routines until September’s weirdo three-game set in Oakland, without baseball plodding into the post-midnight hours dragging us half-willingly along behind it.

* Shame on me if I ever miss a chance to blame something on Tony La Russa.

by Greg Prince on 12 June 2022 12:02 pm Hey old friends

How do we stay old friends

Who is to say, old friends

How an old friendship survives?

One day chums

Having a laugh a minute

One day comes

And they’re a part of your lives

New friends pour

Through the revolving door

Maybe there’s one, that’s more

If you find one

That’ll do

—Stephen Sondheim

1. Noah Syndergaard Juan Lagares

When we saw the schedule for 2022, we circled LAA because we knew it would represent a chance for us to say hello to dear Old Friend Noah Syndergaard Juan Lagares, a distinguished former Met of long standing who was a big part of our team through rough times and good times, including the best times of relatively recent times, the 2015 National League championship season. No doubt when we looked forward to playing the Angels this year, the first Old Friend we thought of was 2016 All-Star Noah Syndergaard 2014 Gold Glove recipient Juan Lagares, who absolutely meets the above description and has actually taken the field versus the Mets in the current series in Anaheim. Lagares may not have excelled for the Angels the way he once did for the Mets, but there he is, showing up like he’s supposed to. When the Angels won on Saturday night, 11-6, it may have been Mike Trout (two homers), Shohei Ohtani (a triple short of the cycle), Jared Walsh (an actual cycle) or Michael Lorenzen (six-and-a-third strong innings) who drew the attention of others, but for us, win or lose, this series was always going to be about catching up with Old Friend Noah Syndergaard Juan Lagares.

2. Zack Wheeler

Zack Wheeler is the embodiment of what I’ve come to think of as the Old Friends syndrome. I liked Zack Wheeler a lot when he was a Met. I don’t like Zack Wheeler very much as a Phillie. This is through no fault of Zack Wheeler’s, despite it having been his agency — and his free agency — at the root of his decision to sign with a team that plays our team a lot…a decision he reached once our team couldn’t be bothered to retain his services. The rooting process would necessarily turn on Zack, given that uniform he slipped on after leaving the Mets, though I’m surprised how fiercely I prefer he not do well. He’s no longer a Met. He’s a Phillie. He’s also still good at what he does. It seems more complicated than “he spurned us, we scorn him,” but basically that’s how Mettily we roll along. We fancy ourselves loyal to a fault. It’s not our fault Old Friends move on.

3. Travis d’Arnaud

There is a life cycle to Old Friends. It doesn’t always work exactly this way, but it goes more or less something like this:

• I’m sorry to see him leave.

• He’s signed somewhere else — he’ll always be a Met to me.

• He’s trying on his new jersey for the press — he looks so strange in that get-up, but good luck to him.

• When he faces the Mets, I’ll definitely give him a nice hand.

• He sure did well against us…well, I guess he was motivated.

• He seems to have gotten it together…we shouldn’t have let him go.

• He had another great game against us — cut it out already.

• He’s going to the All-Star Game/playing in the postseason/winning an award — eff this guy.

• BOO!

Later, much later, toward the end of his career as he’s barely hanging on, maybe we’ll see his name resurface when he signs a minor league contract and finagles an invitation to Spring Training somewhere and feel good for him. Even later, in retirement, perhaps he’ll drop by as part of a Mets Old Timers Day or similar event and he’ll slip the old jersey back on and we’ll feel all warm and fuzzy once more that this guy was one of ours when he was.

I look forward to that happening with Travis d’Arnaud, starting catcher for the 2015 National League champion Mets, because right now, he’s a fucking Brave. BOO!

4. Steven Matz

Steven, the ur-Long Island product, should have stayed a Met his whole career provided he’d pitched well enough to merit continuation in our ranks and hearts. Matz stopped pitching well as a Met and he was traded. Trades happen. Changes of scenery can help even kids who grew up in Stony Brook. Steven Matz the Blue Jay was wished well. Steven Matz the free agent nearly came home. Steven Matz instead went to St. Louis, the only non-division rival we still sort of believe in our bones is in the NL East, and praised Adam Wainwright and Yadier Molina and “the best fans in baseball” to the high heavens upon his arrival. He was still a great story in 2015 and an intermittently decent pitcher through 2020. But until further notice, he can go throw to Travis d’Arnaud.

5. Wilmer Flores

The exception that proves the rule. Wilmer Flores homered off Jacob deGrom as an Arizona Diamondback. Winked at Jake before doing it! Went to San Francisco and makes it his business to try to beat the Mets as a Giant because this is the business Wilmer Flores has chosen. But he’s Wilmer Flores. We love Wilmer Flores. We’ll always love Wilmer Flores. However, should an October outcome boil down to Max Scherzer facing Wilmer Flores this year, whatever Max throws this guy is to be called a strike. We won’t complain when it is.

6. Justin Turner

I’m beginning to think the cavalier non-tendering of the Mets’ Justin-of-all-trades in 2013, after the kid played everywhere and never complained, might have been a mistake.

7. Amed Rosario

It’s not that I miss Amed Rosario playing shortstop for the New York Mets. It’s that I invested four years of my rooting life in Amed Rosario developing into the superstar we were informed he was destined to be. It was coming, I was sure. Then, one January day, he (with other potential infield bright light Andrés Giménez) was sent away to obtain Francisco Lindor. I was now one of those FBI agents on The Sopranos taking down a picture of a suspected mobster from the bulletin board and tossing it into the trash after learning the member of such-and-such crime family was sleeping with the fishes and thus was no longer of use to us. There was no more point to hovering over Rosario’s progress. The only time I check Cleveland Guardian statistics now is when Lindor is in a slump.

8. Oliver Perez

The last member of the 2006 National League East champions still plying his craft in the major leagues as 2022 began, Ollie has recently been sighted pitching for Toros de Tijuana in the Mexican League. One win, one loss, one save, forty years of age. Dude got us through six innings of a Game Seven with a little help from his friend Endy. The long, appreciative memory soars over the messiness of 2010 and remembers Ollie just fondly enough to dig his continued life in baseball. Old Timers Day 2026, I am so there for this guy (assuming he’s retired by then).

9. Michael Conforto

When announcers or reporters invoke the phrase “old friend” to refer to a former member of your team who is now out to best your team, I think it’s one of those “bless his heart!” things. People who say “bless his heart!” don’t really want to bless the heart of whoever they’re talking about. In one segment of the country, that attitude is referred to as Minnesota Nice. It’s not as nice as it sounds. When lingering free agent Michael Conforto eventually signs with somebody who isn’t the Mets, I’d like to believe I’ll remember Michael Conforto the 2015 rookie sparkplug who grew into a dangerous hitter and all-around top-notch player and not find some reason to forget he was one of our main guys for a long time. If he puts on a particularly offensive uniform — or finds a way to not be on the field when the Mets come to his new town after talking a big game in advance of that visit — maybe the better angels of his Met past won’t be uppermost in my mind. If the Mets are going badly, maybe we’ll have room for nuance, because an ex-Met tends to look better than a current Met if the current Mets are the pits. If the Mets are going well, we’ll be so enchanted with our new friends that we’ll see everybody who’s not with us as thoroughly against us. We’ve been going well this year and that’s how we treat our Old Friends these days. The nerve of the Wheelers, Matzes and d’Arnauds getting on with their careers! Ah, we’re fans. We oughta make more sense than we do sometimes. In the meantime, amid the exploits of New Friends Mark Canha and Starling Marte, not to mention the first career homer launched late Saturday by fresh face Khalil Lee, when was the last time you considered our outfield and gave more than passing thought to Michael Conforto?

10. Aaron Loup

An Angel teammate of Noah Syndergaard Juan Lagares. When we looked forward to seeing Noah Syndergaard Juan Lagares in Anaheim, it occurred to us we’d reacquaint as well with 2021 MVM front man Aaron Loup. Sure enough, Loup got out a couple of Mets on Saturday night and then presumably retired to his mini-fridge of Busch Light. We won’t begrudge him his refreshment. It’s not like he’s Noah Syndergaard.

NOT RANKED: Jeurys Familia and Brad Hand of the Phillies; Guillermo Heredia, Darren O’Day and Collin McHugh of the Braves; Erasmo Ramirez of the Nationals; Kevin Pillar of the Dodgers; the aforementioned Giménez of the Guardians; Paul Sewald of the Mariners; Stephen Tarpley and Alejandro de Aza of the Long Island Ducks; Robinson Cano of the El Paso Chihuahuas; Matt Harvey of the Orioles (currently serving a sixty-day suspension from Major League Baseball); free agent COO Jeff Wilpon; Noah Syndergaard of the Angels.

FOR A FURTHER DISCUSSION OF OLD FRIENDS: Listen to the current episode of National League Town.

by Greg Prince on 11 June 2022 12:21 pm Following Friday night’s 7-3 victory over the Angels, the 2022 Mets are 39-21 after sixty games. Here is a comprehensive list of every Mets team that had as good a record or better than the current edition at the same juncture in its season:

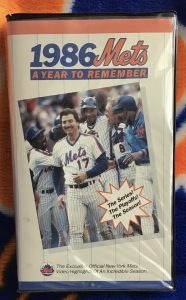

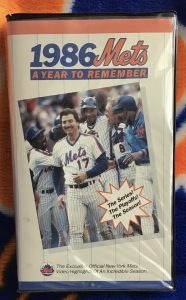

1. 1986: 44-16

That’s it. That’s the list.

It may not feel as if you’ve been watching the second-best Mets team ever through sixty games, whether on real TV or Apple TV+, because the late nights, the West Coast and the accumulated nicks, scrapes and bruises can take their toll on the psyche in a given week. It also bangs up momentum. The Mets have won four of eight in California with two to go. That also means they’ve lost four of eight. None of the four losses have felt straight out of 1986, let alone 2022. Yet here we are, 39-21, perhaps paused and refreshed to enjoy the surreal thing we’ve called this joyride most of this year.

Tylor Megill returned Friday night. He was gone a month. He’s back. He may not have been in ideal Friday night “Hey guys, let’s a bunch of us throw a no-hitter!” mode, but the Big Drip reinserted himself in the rotation and didn’t altogether droop. He was followed to the mound by David Peterson, who was more effective as a long reliever than he’s been lately as a starter. I’ll take my chances with these two finding their way, particularly if neither has to spend the rest of the year facing Brandon Marsh (who produced a homer off each of them and a beard that could eliminate Luis Guillorme’s in the hirsute semifinals).

Admit it: you figured Megill was out for the rest of the season. His return isn’t technically one of the 39 victories, but it all adds up.

We’ll overlook the encouraging reports on Scherzer and deGrom in the interest of seeing/believing and simply be happy Pete Alonso was among the Mets gripping a bat and participating in Buck Showalter’s lineup. Played the field, too. Got a base hit. Stole a base!

Admit it: you figured Alonso was out for the rest of the season.

Pete’s physically adequate. Starling Marte indicates he is, too, and when the Mets are on SNY again tonight, he should be playing. The team isn’t whole, but it’s close enough. On Friday night, it had Brandon Nimmo driving in three runs, Mark Canha driving in three runs, everybody getting on base at least once and Edwin Diaz closing out a non-save situation without incident. Last Sunday, it seemed paramount to preserve Diaz for his next save opportunity and not use him a second inning. Edwin hadn’t pitched since and the Mets still haven’t encountered a save situation since Sunday. Funny how that works.

Ups and downs. Ins and outs. Not much specific that can be predictable. Generally, though, you should have a handle on your team after sixty games. A lukewarm week shouldn’t preclude using a potholder when grabbing the 2022 Mets’ handle. On balance, they’re the second-hottest Met team ever.

A word on the 1986 Mets in this context. Their 44-16 mark remains burned in my memory. I couldn’t believe my team could play sixty games and lose only sixteen of them. When they won their 44th, they extended their lead over second-place Montreal (that night’s opponent) to 11½ games. The National League East race was over in the middle of June.

Then it wasn’t quite. The Expos won their next two games against the Mets at the Big O and their first two games against the Mets when they soon faced each other again. The Mets lost five of seven following the seven-game winning streak that catapulted them to 44-16. On June 25, the Expos carried a 2-0 lead over the Mets to the bottom of the fourth. Hold on in this series finale and they’d be seven out. Still a long swath of real estate between second place and first place, but noticeably shorter than what faced them in Quebec a little more than a week earlier. Those Expos refused to be pushed over. The mind conjured thoughts of a potentially stressful pennant race on the order of 1985. Wait a sec — baseball like it oughta be ought not be laced with this kind of angst.

Then the mind relaxed, because in the bottom of the fourth inning on June 25, 1986, Kevin Mitchell, Ray Knight, Sid Fernandez (!) and Lenny Dykstra each drove in a run; the Mets mounted a 4-2 lead; George Foster added a homer in the home sixth; Sid and Roger McDowell teamed to shut out the visitors to Shea the rest of the way; and following the Mets’ 5-2 win that put the Mets nine up over the Expos, two things happened.

• Hubie Brooks, by then with Montreal, said of his club’s falling short of a sweep, “Nine out is so damn close to ten. Seven out is so damn close to five. I think we did good, but it’s too bad we couldn’t be better than nine out.” Hubie’s veritable waving of the white flag when the Mets went to 47-21 reinforced my notion of 44-16: it’s over.

• The Mets lit out on an eight-game winning streak, by the conclusion of which they held a 12½-game lead and it was still over, only more so. To paraphrase Tim McCarver from the height of the high summer fireworks in Queens, they were spreading the news that they couldn’t be beat.

For the record, the Mets also lost five of seven after streaking to 20-4 in May. There’d be a pair of three-game losing streaks in July and a 1-6 rough patch in August. You might remember a four-game skein in the wrong direction in the middle of September. You might remember it because the Mets were on the verge of clinching their division and the sudden spate of losses amounted to a nuisance en route to a celebration. The tad of pent-up frustration simply made the champagne-spraying that much more raucous (and, even better, transported it from the Vet to Shea), yet things inside the year of years could indeed get frustrating for a few days here and a few days there. The Mets of 1986 didn’t compile a 1.000 winning percentage. It only feels as if they did.

Too soon? Comparing any subsequent Met year to 1986 with slightly more than 100 game to go may be akin to playing with karmic fire. There’s only one 1986. The Mets wound up winning two of every three games they played that regular season. Since 1986, the Mets have maintained a .667 pace no later than 57 games into a season. They did it when they reached 38-19 in 1988 and they did it again when they reached 38-19 this past Monday in San Diego. The 1988 Mets are a whole other story, but suffice it to say they fell off the two-of-every-three horse as the dog days nipped at their heels, yet they never fell apart. They won a hundred games and a division title.

Right now, these 2022 Mets are better than that team and every team that’s come before 2022, with the exception of one. Still a lot of real estate to cover. Still an opponent or two in the division that’s refused to definitively run into our brick wall. The Braves have been beyond hot, winning nine in a row. The Phillies, too, who shed themselves of Joe Girardi and gained eight consecutive wins as a result. Neither foe could be doing any better. Neither is within six games of the Mets. Those competitors will cool off from their current state of scalding. The Mets won’t be on the West Coast forever and are likely to heat up beyond this week’s lukewarm setting.

I’m a little grumpy from having to stay up late practically every night to watch my team. Wayne Randazzo’s welcome voice notwithstanding, I’d have preferred SNY to Apple TV+. The series split in L.A. and the loss of two of three in San Diego weren’t optimal and remain fresh in the current consciousness. Yet here we are in 2022 looking up only at 1986. Even in what passes for its doldrums, this team somehow manages to give us something unsurpassed to which to aspire.

The 2022 Mets are thus far super. So was the Mets’ premiere utility player of the 2000s. Listen to the current episode of National League Town to solve that Monday crossword of a puzzle.

by Greg Prince on 10 June 2022 3:21 pm A couple of weeks ago, I had the pleasure of sharing the story of how Nanette Fluhr’s painting “Lonny,” a portrait of her son in a Mets cap and Mets jersey, was going to be digitzed and travel to the Moon. Quick addendum: that piece that appeared on FAFIF will be getting the same treatment — hitching a ride on the Lunar Codex mission next year alongside an array of art and literature curated to encapsulate and illustrate humanity’s creative impulses…just in case there’s life up there that doesn’t already keep up with all matters Metsopotamian. (I hear the reception for Newsradio 880 can get fuzzy outside the Tri-State Area.) The details are in here in case you’re wondering, as I kind of am, “What?”

I guess the old saying must be true: “Something written about the Mets will land on the Moon before Noah Syndergaard faces his old team.”

by Jason Fry on 9 June 2022 3:23 am Pete Alonso and Starling Marte are not on the IL, not apparently out for weeks or months, but day to day. And that was the good news from MetsWorld for Wednesday night.

Seriously, if you got the injury update and then went to bed, you were the smart one. Because the game was a disaster. Chris Bassitt, who started the season looking like Max Scherzer‘s icy lieutenant, got mauled by the Padres, with Jurickson Profar a particular offender. Bassitt’s on a lousy run, the kind pitchers get stuck in now and then — lets assume it’s nothing more than that. The Mets lost by 11 runs, had five hits — compared with three errors — and the only suspense was whether J.D. Davis would wind up pitching. (He did not.) Oh, and Khalil Lee made his season debut, which I guess was something.

Anyway, it was a lousy night, and I hope for your sake it unfolded while you were asleep or elsewhere. Day off tomorrow. They could use it; so could we.

by Greg Prince on 8 June 2022 2:10 pm On August 8, 1963, the day after Jim Hickman hit for the first cycle in Mets history, the Mets won again, 3-2, with first baseman Duke Carmel (one of two Dukes to play for the Mets that day at the Polo Grounds) hitting the deciding home run in the eighth inning. Between Carmel’s big blow and Al Jackson’s five-hitter, we’re gonna call that Day After Cycle a good day, especially since the 1963 Mets won only 51 games — and really especially because on the day after the Day After Cycle, Hickman hit a walkoff grand slam to beat the Cubs and provide the margin necessary to break Roger Craig’s eighteen-game losing streak. Weeks didn’t get a whole lot better when the baby Metsies were learning to crawl.

On July 7, 1970, the day after Tommie Agee hit for the second cycle in Mets history, the Mets won again, 4-3, though it was a win that nearly got away. Up one in the top of the ninth, rookie reliever Rich Folkers gave up a game-tying single to Cardinal Jose Cardenal, but then got Joe Torre to ground into a double play to send things to the bottom of the ninth at Shea with no further damage. Sal Campisi, pitching in relief of Bob Gibson, was no Bob Gibson…not that anybody else besides Bob Gibson was. Campisi loaded the bases and Ron Swoboda unloaded them by drawing a walk. It may not have been monumental, but it was effective. It was also the fifth Met win in a row amid a streak that would reach seven. We’ll call that a good Day After Cycle.

On June 26, 1976, the day after Mike Phillips hit for the third cycle in Mets history, the Mets maintained their winning ways, laying six runs on the Cubs in the third inning at Wrigley Field and cruising to a 10-2 victory. Sluggers John Milner and Dave Kingman each homered. So did the guy who cycled the day before. Phillips now had two homers on the year (and the week) and the Mets had won three in a row. Seven games later, the skein would be up to ten. Yes, a very good Day After Cycle.

On July 5, 1985, the day after Keith Hernandez hit for the fourth cycle in Mets history, the Mets rubbed the sleep out of their eyes — Keith’s big night unfolded during the famous nineteen-inning affair at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium — and rolled over the Braves once more, 6-1 (the Braves were sleepy, too). Rick Aguilera, who was not among the seven pitchers Davey Johnson used the night/morning before, went the distance. Wally Backman whacked his lone home run of the year. The Mets extended their nascent winning streak to four games; not only would it go to nine, but the 1985 Mets were about to stir to life in a big way, racking up 30 wins in 37 games by mid-August. You couldn’t ask for a much better Day After Cycle or, really month-plus.

On August 2, 1989, the day after Kevin McReynolds hit for the fifth cycle in Mets history, the Mets showed off a gem even rarer than one player collecting a single, double, triple and home run. They started Long Island’s Own Frank Viola, the previous season’s American League Cy Young Award winner. The Mets acquired Viola at the trade deadline fewer than 48 hours earlier. In that two-day span, they clobbered he Cardinals in St. Louis on McReynolds’s cycle and Sid Fernandez’s shutout and unveiled Viola. Frankie from East Meadow gave the Mets eight strong innings before getting pinch-hit for in the ninth, trailing, 2-1. His new teammates did him a solid, scoring three times on his behalf, furnishing a 4-2 lead for closer Randy Myers. Myers gave up one run, but not two, so the Mets and Viola could claim a 4-3 victory, part of a 15-4 spurt that catapulted the Mets back into serious NL East contention (at least for a while). We’ll certainly call that a sweet Day After Cycle.

On July 4, 1996, the day after Alex Ochoa hit for the sixth cycle in Mets history, the Mets moved on from Philadelphia — where you’d think you’d want to spend Independence Day — and set down in Montreal. The change of countries did not change the Mets’ fortunes, as Ochoa’s team continued the competence they’d demonstrated at the Vet. Inside the Big O on this most American of holidays, Robert Person and Dave Mlicki combined on a six-hit, 4-0 blanking of Les ’Spos. Todd Hundley blasted his 21st homer of the season to help secure the second W in a four-game winning streak. Ochoa went hitless, but was still considered to have five tools. A fine, international Day After Cycle.

On September 12, 1997, the day after John Olerud hit for the seventh cycle in Mets history, Met historical luck ran out, if not without a fight. Barely hanging on in their unlikely Wild Card bid, the Mets bowed to Montreal at Shea, 3-2, in fifteen innings, the last miserable out registering on Luis Lopez’s grounder that stranded the potential tying and winning runs. Perhaps the shock of watching Olerud sprint to third base the night before took something out of the home team. We can’t label this a good Day After Cycle, but we’re happy to report it was only a hiccup. The day after the Day After Cycle was the Carl Everett Game, a.k.a. the Saturday the Mets were down, 6-0, in the ninth, yet pulled into a tie on Everett’s grand slam and won in the eleventh on Bernard Gilkey’s three-run shot. The day after the day after the Day After Cycle, Luis Lopez redeemed his weekend by launching his first Met homer for the only run of a Met win on Keith Hernandez Mets Hall of Fame Day, and did we mention Lopez, like Hernandez, wore 17, back when 17 wasn’t slated for retirement? So let’s nudge this one toward collective positive cycle aftermath.

On July 30, 2004, the day after Eric Valent hit for the eighth cycle in Mets history, the Mets thought they had a chance to win, both in the near and medium term. Valent added his name to the cyclical annals by daringly lighting out for third on a ball down the right field line at Olympic Stadium because he had a single, double and homer already and when is Eric Valent gonna have another opportunity to cycle? Valent was safe at third. The Mets, however, were stuck in fourth. They’d made a nice lunge at first earlier in July, but were now six games out. They could either take stock of their progress and position themselves to grow from their modicum of midsummer success down the road, or they could do try to do something even more dramatic than attempt to stretch a double into a triple. Their front office chose the latter on July 30, trading 2002 top draft pick Scott Kazmir to Tampa Bay for veteran starter Victor Zambrano, hoping Zambrano could be the missing piece to a challenger struggling to remain in contention. Short version: It didn’t work out. Also, the Mets lost their game at Turner Field on July 30 and proceeded to get swept in their series versus Atlanta, effectively ending their pennant race aspirations. Kazmir went on to a very solid career. Zambrano didn’t. Maybe not the best Day After Cycle.

On June 22, 2006, the day after Jose Reyes hit for the ninth cycle in Mets history, we can’t say the Mets won again, because the Mets actually lost the game in which Reyes cycled, which seemed unfathomable, given that the Mets were running away with the National League East and Reyes was running away with Shea’s hearts. When he singled to secure his cycle in the bottom of the eighth, the crowd broke into Jose!-Jose!-Jose! en masse, making it a serenade that would follow Jose for the rest of his Met days. Alas, Billy Wagner drowned out the enthusiasm and blew the Mets’ 5-4 lead over Cincinnati in the top of the ninth and turned it into a 6-5 loss, and let’s say the closer took some of the steam out of what had been an incandescent evening. But the Day After Cycle would have its day in the sun. I can confirm that it was a glorious matinee, with Pedro Martinez buckling down (three swinging strikeouts to end his gritty six innings), David Wright going deep (two two-run homers) and Jose!-Jose! still running the Redlegs ragged (two stolen bases). Someone other than Billy Wagner — Chad Bradford — came on to nail down the save in the 6-2 win. All told, a brilliant Day After Cycle.

On April 28, 2012, the day after Scott Hairston hit for the tenth cycle in Mets history, the Mets were again tasked with not losing a second game in a row. Hairston’s heroics were obscured in an 18-9 creaming at Colorado, yet the Mets had enough gumption to recover in their next game, 7-5, continuing to pound the ball at Coors Field (thirteen hits) yet not forgetting how to pitch just well enough to win at elevated heights. So not only was this a redemptive Day After Cycle, it put a nice bow on the Mets’ 50th Anniversary Conference, which concluded at Hofstra University the very same day. We can always use more Met history.

On June 7, 2022, the day after Eduardo Escobar hit for the eleventh cycle in Mets history, the first Mets cycle in ten years and the first Mets cycle in a winning cause in eighteen years, it occurred to me the last thing I wanted to do was write about the 7-0 loss at Petco Park that followed the 11-5 win in which Escobar starred. So instead of dwelling on worrisome injuries to Pete Alonso (hand) and Starling Marte (quad) or discerning if anything beyond a bad outing is to be gleaned from Taijuan Walker’s subpar start versus the Padres (though Walker did recover to go six after a rough first two) or moping over the measly two hits the Mets managed to collect off Yu Darvish and Adrian Morejon, I remembered we can always use more Met history, especially the day after a not so great Day After Cycle.

by Jason Fry on 7 June 2022 1:34 am “Grind you till you break” is Chris Bassitt‘s phrase, first uttered after his debut in blue and orange and the Mets having come back from being knocked down by sundry Nationals to win by doing terrible things to pitchers, spoken of earlier on this trip, and of course immortalized as part of that equal parts stirring and strange ad in which various Mets … hang around outside a bodega.

Here’s what he said back then:

There’s a lot of guys — a lot of teams — that it’s all or nothing. But this team is not that. We might hit some homers, but we’re just going to grind you until you break. That’s the mentality we’ve been preaching since Day One — we have the pitching staff to hold it down until that happens.

Monday night’s game against the Padres — not quite the Dodgers but a pretty good outfit — was a perfect encapsulation of that philosophy, with the Mets getting the program started early against Blake Snell. Brandon Nimmo saw eight pitches and grounded out. Starling Marte smacked Snell’s second pitch over the infield for a single. Francisco Lindor saw six pitches, fanning on a 3-2 slider in the dirt, and lingered by the on-deck circle to give Mark Canha a report on what he’d seen.

The Mets had a runner on second but two out — a spot of bother for Snell but nothing too ominous. But then Pete Alonso refused to be baited and walked on five pitches. Canha, in an 0-2 hole, stubbornly resisted expanding the strike zone and walked on six pitches. J.D. Davis — not renowned as the most patient of hitters — also fell into an 0-2 hole, with the second strike coming on the high fastball that is his kryptonite. But Davis reined in his aggression and worked out a nine-pitch walk, bringing in a run. Three pitches into his own at-bat, a rejuvenated-looking Eduardo Escobar slashed an outside changeup to right and the Mets had a 3-0 lead. When the first inning was finally over Snell had faced eight Met hitters and needed 43 pitches to do so.

There was the grinding — but there’s another part of the equation that’s easy to miss. In the fourth, with Snell tired and trying to squeeze more pitches out of his arm than might have been there, the Mets pounced early, starting with an Escobar double. (He’d add a bomb of a home run and a two-run triple later, hitting for the cycle and demonstrating reports of his professional demise were clearly exaggerated — Escobar’s mile-wide smile after his feat has to be in every season highlight film.)

That pouncing is the second part of the formula, the part where the opponents break. Make a starting pitcher show you his entire arsenal, pick it apart, drive up his pitch count, and then seize opportunities.

Carlos Carrasco, meanwhile, continues to have the kind of season that as Mets fans we’ve come to assume we don’t get to see. Carrasco’s maiden voyage in New York was a disaster, derailed by injuries to half his limbs, and he arrived in spring training with the usual talk about good health and starting over. But it was hard to hear it: If you’ll forgive some confirmation bias, that kind of thing never seems to work out for us, does it?

Except sometimes it does. Carrasco has been healthy and has started over, and he’s been wonderful — on Monday he befuddled the Padres with mid-90s gas that perfectly set up his slider and change, striking out 10 and even high-fiving a not particularly attentive baby in Mets garb. (Mom looked happy about it, though.)

It got messy late, as Joely Rodriguez and Drew Smith got knocked around before Escobar rode to … well, not the rescue exactly but the moment where you can put your phone away because it’s going to be OK. The Mets have work to do in the bullpen, absolutely. But every team has some work to do. As long as the Mets stay with the approach Bassitt’s made famous, they’ll be OK. And probably a lot better than that.

|

|