The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

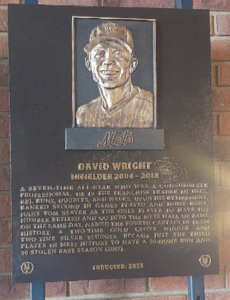

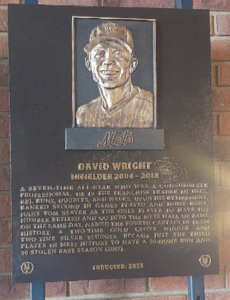

by Greg Prince on 20 July 2025 12:25 pm That it was inevitable didn’t make it any less irresistible. The number 5 could have been retired as soon as David Wright took off his jersey in 2018. Many of us mentally reserved a spot for it at Citi Field before Citi Field was announced as the successor facility to Shea Stadium at the outset of 2006. No more than a season-and-a-half’s worth of exposure to the prospect who lived up to his notices, and we could have guessed a day like Saturday was coming. I don’t know what they’re building over there in the parking lot, but they need to make sure we can see 5 and take heart from it forevermore.

Done! David Wright’s number was elevated to Citi Field’s highest rung on Saturday afternoon, a delightful formality whose “i” was dotted and “t” was crossed when his New York Mets Hall of Fame plaque was simultaneously unveiled upstairs from the Rotunda. The Mets, who used to do not much to remember let alone honor the players who built the best of their legacy, proceeded on the Wright track with all deliberate speed. Got him to the bigs at age 21. Got him to the rafters at age 42. Waited just long enough so his three kids can maintain tangible memories of their dad’s day in the overcast sun. Didn’t wait so long that his parents weren’t around to soak it in. Done! David Wright’s number was elevated to Citi Field’s highest rung on Saturday afternoon, a delightful formality whose “i” was dotted and “t” was crossed when his New York Mets Hall of Fame plaque was simultaneously unveiled upstairs from the Rotunda. The Mets, who used to do not much to remember let alone honor the players who built the best of their legacy, proceeded on the Wright track with all deliberate speed. Got him to the bigs at age 21. Got him to the rafters at age 42. Waited just long enough so his three kids can maintain tangible memories of their dad’s day in the overcast sun. Didn’t wait so long that his parents weren’t around to soak it in.

The presence of Rhon and Elisa Wright may have made me happiest Saturday — in stark contrast to the 5-2 loss the Reds pinned on the Mets following the conclusion of the day’s far more pleasurable ceremonial aspects. Not only is David in his prime as a person, but those who raised him appear in the finest of fettle. I kind of fell in love with them watching the SNY documentary about their son. They wanted the best for him. They cleared a path for him. They’re proud of not just his accomplishments, but his whole being. It was all I could do to not hug them when I saw them in the press conference room prior to Saturday’s game.

I don’t think David Wright’s parents are wholly unique in getting behind their child and pushing him forward, it’s just that we have evidence of how it worked out for us, and how much it meant and continues to mean to them. I don’t know what it was like inside the Wright household when our boy was a kid, but it certainly seems they understood what he wanted to do and are happy he did it (I’m not sure I fully grasp what it’s like to have been in a parent-child relationship where the emotional transactions were that clear-cut). David didn’t have to wish Rhon and Elisa were here to see this day. The long view of history is a marvelous thing, but some heels don’t have to cool until they’re ice cold. I don’t think David Wright’s parents are wholly unique in getting behind their child and pushing him forward, it’s just that we have evidence of how it worked out for us, and how much it meant and continues to mean to them. I don’t know what it was like inside the Wright household when our boy was a kid, but it certainly seems they understood what he wanted to do and are happy he did it (I’m not sure I fully grasp what it’s like to have been in a parent-child relationship where the emotional transactions were that clear-cut). David didn’t have to wish Rhon and Elisa were here to see this day. The long view of history is a marvelous thing, but some heels don’t have to cool until they’re ice cold.

I also adored what could have been taken as the random assortment of teammates who traveled to Flushing on David’s behalf. I knew they weren’t random because I’ve been following David’s story for the half of his life that he’s been an all-time Met, yet when I glanced over my shoulder and saw Joe McEwing, Josh Satin, Cliff Floyd, and Michael Cuddyer sitting in a row waiting to hear from their friend before the ballpark as a whole would wrap its arms around him, I wanted to grab each of them and slip them into a binder. David’s story inevitably mentions them as influences and compatriots, not just guys he used to work with. Jose Reyes was there, of course, as was Daniel Murphy. Two managers, Terry Collins and Willie Randolph, plus coach Howard Johnson joined in the assemblage. HoJo’s old pal Keith Miller was David’s agent, and he was on hand, too. In 1988, I went out of my way to purchase a Keith Miller baseball card. When was the last time any Mets fan stopped to think about most of these guys? David is probably more thoughtful than most of us. A passel of columnists, reporters, and broadcasters who don’t necessarily come around that often also made sure to be back for The Captain. It was old home weekend at a home that’s not that old and a returnee who hadn’t been gone too incredibly long. I also adored what could have been taken as the random assortment of teammates who traveled to Flushing on David’s behalf. I knew they weren’t random because I’ve been following David’s story for the half of his life that he’s been an all-time Met, yet when I glanced over my shoulder and saw Joe McEwing, Josh Satin, Cliff Floyd, and Michael Cuddyer sitting in a row waiting to hear from their friend before the ballpark as a whole would wrap its arms around him, I wanted to grab each of them and slip them into a binder. David’s story inevitably mentions them as influences and compatriots, not just guys he used to work with. Jose Reyes was there, of course, as was Daniel Murphy. Two managers, Terry Collins and Willie Randolph, plus coach Howard Johnson joined in the assemblage. HoJo’s old pal Keith Miller was David’s agent, and he was on hand, too. In 1988, I went out of my way to purchase a Keith Miller baseball card. When was the last time any Mets fan stopped to think about most of these guys? David is probably more thoughtful than most of us. A passel of columnists, reporters, and broadcasters who don’t necessarily come around that often also made sure to be back for The Captain. It was old home weekend at a home that’s not that old and a returnee who hadn’t been gone too incredibly long.

Citi Field isn’t the House that Wright Built. If it was, the dimensions would have been constructed in deference to his opposite-field power. But it was immediately the House of David when it opened in 2009, and Saturday proved it always will be. He was so comfortable being who he was, which is to say always a touch uncomfortable that 42,000 people arrived en masse to see him, and many among them wore his name and number on their backs. But he gets that they did, and nobody could have been more appreciative that others thought he deserved such attention. Reverence he’d avoid if he could, but it was too late. Leave it to David, and he’d simply romanticize being a kid who got his picture taken in Norfolk with Tides like Clint Hurdle and D.J. Dozier…which he did, because what else is a kid who went to Tides games gonna romanticize? Citi Field isn’t the House that Wright Built. If it was, the dimensions would have been constructed in deference to his opposite-field power. But it was immediately the House of David when it opened in 2009, and Saturday proved it always will be. He was so comfortable being who he was, which is to say always a touch uncomfortable that 42,000 people arrived en masse to see him, and many among them wore his name and number on their backs. But he gets that they did, and nobody could have been more appreciative that others thought he deserved such attention. Reverence he’d avoid if he could, but it was too late. Leave it to David, and he’d simply romanticize being a kid who got his picture taken in Norfolk with Tides like Clint Hurdle and D.J. Dozier…which he did, because what else is a kid who went to Tides games gonna romanticize?

David was always one of us, geographically displaced on the surface, but with a running start. He didn’t have to subscribe to Baseball America to get a handle on Mets Triple-A prospects. He just had to get a ride with his dad, who worked security at Harbor Park in his off hours from the police force. Maybe that appreciation of how baseball comes together, from the inside out and not just on the field, explains why David maintains so many friendships with players who didn’t approach his performance level, and why more than any player I can think of was enmeshed with so much of the Mets personnel who make the Citi Field operation run. It was no accident he could offer up warm and textured memories when asked in his press conference about the late public relations specialist Shannon Forde and the late team photographer Marc Levine. It was no accident that practically the first words out of his mouth when he stepped to the mic during his ceremonies were to acknowledge Tony Carullo, the longtime visiting clubhouse manager who was receiving the Mets’ Hall of Fame Achievement Award. David was always one of us, geographically displaced on the surface, but with a running start. He didn’t have to subscribe to Baseball America to get a handle on Mets Triple-A prospects. He just had to get a ride with his dad, who worked security at Harbor Park in his off hours from the police force. Maybe that appreciation of how baseball comes together, from the inside out and not just on the field, explains why David maintains so many friendships with players who didn’t approach his performance level, and why more than any player I can think of was enmeshed with so much of the Mets personnel who make the Citi Field operation run. It was no accident he could offer up warm and textured memories when asked in his press conference about the late public relations specialist Shannon Forde and the late team photographer Marc Levine. It was no accident that practically the first words out of his mouth when he stepped to the mic during his ceremonies were to acknowledge Tony Carullo, the longtime visiting clubhouse manager who was receiving the Mets’ Hall of Fame Achievement Award.

It was never an accident that David was everybody’s captain from just about the moment he showed up at Shea. The old saying suggests you should treat people the way you wish to be treated. I suspect David Wright didn’t dwell on how he’d be treated. He put those around him first, including however many tens of thousands paid their way into Shea or Citi on a given night. It came through when he addressed his fellow Mets fans in the crowd on Saturday. David Wright forever came across as our hometown kid. It doesn’t matter that he’s from Norfolk, Va. He grew up in Metsopotamia. Everything about him can seem a little corny, a little hokey, a little less than big-time. That’s because he’s one of us — the corny, the hokey, life-size at our biggest. He’s never put on pretensions that he was any more than that, except he played ball. Sometimes we forget what a bleeping star he was. It was never an accident that David was everybody’s captain from just about the moment he showed up at Shea. The old saying suggests you should treat people the way you wish to be treated. I suspect David Wright didn’t dwell on how he’d be treated. He put those around him first, including however many tens of thousands paid their way into Shea or Citi on a given night. It came through when he addressed his fellow Mets fans in the crowd on Saturday. David Wright forever came across as our hometown kid. It doesn’t matter that he’s from Norfolk, Va. He grew up in Metsopotamia. Everything about him can seem a little corny, a little hokey, a little less than big-time. That’s because he’s one of us — the corny, the hokey, life-size at our biggest. He’s never put on pretensions that he was any more than that, except he played ball. Sometimes we forget what a bleeping star he was.

Good thing we are able to gaze up at 5 to remind us. Good thing we are able to gaze up at 5 to remind us.

by Greg Prince on 19 July 2025 11:32 am Twenty-one years ago tomorrow, the surprisingly contending Mets did not look ready for what was hitting them at Shea Stadium, giving up six runs in the first inning. They’d do plenty of hitting themselves before the game was over, and Armando Benitez would come on to get the save, but the Mets didn’t do enough hitting, and Benitez by then was the closer for the Florida Marlins. Strange time capsule the box score of July 20, 2004, left us. Steve Trachsel started and kept starting despite a disastrous first inning, staying on through five. Future Mets Luis Castillo, Jeff Conine, and Damion Easley joined forces with former Mets Benitez and Josias Manzanillo in the 9-7 victory for the defending world champions. The Marlins, between fire sales, rose to 47-46, one game better than the Mets, each club part of a four-team scramble for first place in the NL East. The scramble would end within a couple of weeks, the Mets — and the Marlins, for that matter — altogether unscrambled from any October aspirations.

On the Met side, John Franco was sent out to pitch the sixth and gave up what would prove to be the winning runs. By the time Johnny was deployed (earlier than had been his custom in his long reign as hometown closer), the Mets had tied the Marlins at seven. Trachsel had settled down and the bats had come alive. Three runs were driven in by Richard Hidalgo, an acquisition in June who was on an all-time Met heater in July, homering ten times. Richard’s three-run bomb in the bottom of the third inning this Tuesday night is what evened the game at 7-7. Two batters earlier, first baseman Eric Valent had pulled the Mets to within 7-4. Valent wasn’t in the starting lineup. He subbed in the top of the second for Mike Piazza. Piazza had to exit after a collision on defense with Juan Pierre. Mike, an All-Star catcher trying his best to become a passable first baseman, was the victim of the baserunner and a throw from his third baseman arriving all at once in an awkward position. His left wrist took the worst of it. He’d be out for a week.

By the time he came back, there’d be a new third baseman for the New York Mets.

On July 21, as Piazza healed, the future arrived in the person of 21-year-old David Wright, hot stuff from Norfolk and at Norfolk, as big a part of the Mets’ plans as their current second baseman Jose Reyes loomed a year earlier. Reyes, 20, was the shortstop when he came up from Binghamton in 2003, but was moved to second in deference to the allegedly wondrous abilities of Kaz Matsui. The third baseman who threw the ball that resulted in the injury to the Mets’ marquee player was Ty Wigginton. Wiggy, as he was known, was only 25, and had attracted Rookie of the Year support in ’03, but his greatest asset as of July 21, 2004, was not youth or promise but versatility. With Mike out, Ty would be the first baseman.

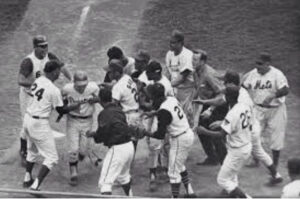

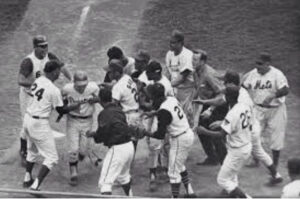

Nobody else would be the third baseman for a very long time now that David Wright was here. The box score of July 20, therefore, tells a story of less a lost world than one poised to change dramatically. Wigginton would be traded before the month was done. Franco and Todd Zeile (who took over for Valent on defense) would wave goodbye to an appreciative crowd on the last day of the season. Reyes would get shortstop back, a move that would compel the less than wondrous Matsui to learn second, a transition that never really took. Hidalgo would leave as a free agent. Piazza, already a legend in these parts, returned to catching and played out his contract before his own emotional goodbye at the end of 2005. Trachsel would keep getting starts through 2006. So would left fielder Cliff Floyd. Veterans Steve and Cliff would be in the lineup on September 18, 2006, about two years and two months hence, the night the Mets clinched their first division title since 1988. In the middle of the celebratory scene that unfolded that night were the young shortstop Reyes and the young third baseman Wright. Other than Trachsel and Floyd, nobody else from either July 20 or July 21 in 2004 was on hand. Nobody else would be the third baseman for a very long time now that David Wright was here. The box score of July 20, therefore, tells a story of less a lost world than one poised to change dramatically. Wigginton would be traded before the month was done. Franco and Todd Zeile (who took over for Valent on defense) would wave goodbye to an appreciative crowd on the last day of the season. Reyes would get shortstop back, a move that would compel the less than wondrous Matsui to learn second, a transition that never really took. Hidalgo would leave as a free agent. Piazza, already a legend in these parts, returned to catching and played out his contract before his own emotional goodbye at the end of 2005. Trachsel would keep getting starts through 2006. So would left fielder Cliff Floyd. Veterans Steve and Cliff would be in the lineup on September 18, 2006, about two years and two months hence, the night the Mets clinched their first division title since 1988. In the middle of the celebratory scene that unfolded that night were the young shortstop Reyes and the young third baseman Wright. Other than Trachsel and Floyd, nobody else from either July 20 or July 21 in 2004 was on hand.

The Mets’ world accelerated its evolution the minute Wright showed up. But there was a Mets world the night before. The tomorrow in that equation was better because it formally introduced us to the player who would, in short order, embody the Mets for the next fourteen years. David Wright started fielding, started swinging, started doing everything that became instantly and indelibly familiar. David Wright started giving us seasons like 2006 and did his best to keep giving us seasons like 2006, even if we wouldn’t see another year substantively like it until 2015. That was a totally if not tonally different Met season, but the one thing it had in common with its predecessor in champagne showers was David Wright played a lead role. Not the same kind of lead role — he wasn’t so young anymore and he wasn’t healthy enough to play that much — but the superstar had become The Captain, and The Captain led the Mets, in his way, to the World Series. That was supposed to happen in 2006. It took a while. Fortunately, David had a while after 2006, if not a whole lot of while remaining after 2015.

All of David’s career, which was Mets and nothing but Mets, gets honored at Citi Field this afternoon. No. 5 rises to the rafters. The club Hall of Fame, conveniently located on pillars at the top of the Rotunda staircase, adds a plaque with his likeness. Mets from 2004 and Mets from well beyond will be in attendance, as will a ballpark full of fans who watched him debut, watched him blossom, watched him endure. “Every generation throws a hero up the pop charts,” Paul Simon said. A generation of Mets fans came of age with David Wright as its frontman. He is the first Met who came along in this century to be honored as Seaver, Piazza, Koosman, Hernandez, Mays, Gooden, and Strawberry have. He is the first Met to have a single digit retired. He is singular in our history. He rose from our farm system and never sought greener pastures. Our pastures were green enough for him. His considerable talents and endless efforts richly enhanced their periodic lushness. All of David’s career, which was Mets and nothing but Mets, gets honored at Citi Field this afternoon. No. 5 rises to the rafters. The club Hall of Fame, conveniently located on pillars at the top of the Rotunda staircase, adds a plaque with his likeness. Mets from 2004 and Mets from well beyond will be in attendance, as will a ballpark full of fans who watched him debut, watched him blossom, watched him endure. “Every generation throws a hero up the pop charts,” Paul Simon said. A generation of Mets fans came of age with David Wright as its frontman. He is the first Met who came along in this century to be honored as Seaver, Piazza, Koosman, Hernandez, Mays, Gooden, and Strawberry have. He is the first Met to have a single digit retired. He is singular in our history. He rose from our farm system and never sought greener pastures. Our pastures were green enough for him. His considerable talents and endless efforts richly enhanced their periodic lushness.

It was fortuitous that the Mets won the first game of the David Wright Era, on July 21, 2004. The night before, they’re a mess. The next day, they’re winners. One can ride that thread only so far. David played in 1,585 games as a Met. Their record in them was 792-793. All the ups. All the downs. So many of both in terms of what surrounded him. Throw in the postseason games in which he played, however, and his Mets went 805-804. That looks a little more Wright, doesn’t it?

As if to presage David Wright’s arrival in official Met immortality, the Mets of July 18, 2025, used the game before his number-raising and plaque-installing to remind us of what it was like in Flushing on July 20, 2004, which is to say they lost. It’s a very different club here than it was twenty-one years ago. Our contention in the NL East is no surprise. We are in a division race that, unlike 2004’s, figures to last. We have Juan Soto, and he homered in the first. We have Brandon Nimmo and Jeff McNeil, the only two Mets remaining from the back end of Wright’s tenure, and McNeil drove in Nimmo in the second. And we have the gumption to manufacture a Fireworks Night rally in the ninth that evoked memories of the one Piazza capped in the eighth on June 30, 2000, when David was a year away from getting drafted by the Mets. On that night, Mike Hampton started versus the Braves. It didn’t go well, and we trailed, 8-1, before prevailing, 11-8. Hampton straightened himself out from that off outing and pitched the Mets to a pennant. When Mike chose free agency and signed with the Rockies, the Mets received a supplemental first-round pick. They used it to draft David Wright. You might say they won even more.

The ninth-inning rally from this Fireworks Night in the present, however, fizzled. The Mets fell Friday to the Reds, 8-4. Sean Manaea pitched far better than Steve Trachsel did on Wright’s Eve then, but for not as long. In his second post-IL start, Manaea worked four sharp innings before being pulled. The 2-1 lead he bequeathed to Alex Carrillo transformed into a 3-2 deficit in the fifth. It was 6-2 when Carrillo gave way to Brandon Waddell. It became 8-2 as Carlos Mendoza resolutely rested the remainder of his bullpen in this first game after the four-day All-Star break. Had Mendy had John Franco, Dan Wheeler, Ricky Bottalico, and Mike DeJean at his disposal as Art Howe did on July 20, 2004, he probably wouldn’t have used them, either. I never thought I’d say this, but score one for Art Howe.

The Mets’ comeback in the ninth showed promise — two runners in, bases loaded, Francisco Lindor coming to bat as the tying run — but no payoff, as Lindor popped out to clear the field for fireworks. The Reds played like they had something to prove. The Mets for too many innings seemed disengaged. Maybe the All-Star break needed to be five days.

Or maybe they just need to get a look at David Wright today and start turning things around for good.

by Greg Prince on 16 July 2025 2:57 pm It’s a Tuesday night in July of 1970. It is the twelfth inning of a 4-4 contest. Pete Rose is on second. Jim Hickman singles into center field. Rose motors around third base. Amos Otis fires to the plate. Rose keeps coming home, regardless that Ray Fosse is blocking his path. The on-deck batter Dick Dietz gesticulates toward the baserunner that he needs to get down and slide. The baserunner has his own idea of what that means. Pete Rose is a bull in Riverfront Stadium’s china shop. Fosse is a cape to be rushed through. All the metaphors collide. Rose bowls over Fosse. The runner is safe, and the National League has won the All-Star Game, 5-4.

It was the Tuesday night that hooked me on the All-Star Game for the next 55 years. It was to be played hard, played by the best, played all night if necessary, played without regard to consequences for opponents who got in the National League’s way. The National League was the league the Mets were in — the Mets’ manager, Gil Hodges, ran the show; the Mets’ ace, Tom Seaver, started the show; the Mets’ shortstop, Bud Harrelson, would trot back to his position for the thirteenth had Otis and Fosse combined to nail Rose — therefore on this Tuesday night and in every primetime showcase like it over the next 55 years, the National League would be my team. Every National Leaguer, even those I rooted against as a matter of course, were was my guy. Every American Leaguer, whatever degree of unawareness I held for most of them as the seasons went by, was a guy who had to be bowled over or at least defeated. For all the pageantry and provincialism that’s informed my fluctuating year-by-year interest since, that’s the equation that’s kept me coming back midsummer after midsummer.

It’s a Tuesday night in July of 2025. It is not the tenth inning. It could be, but there is no tenth inning, despite the score sitting at National League 6 American League 6 after nine. I have tuned in and stayed tuned in. I have always tuned in. I will probably always tune in. I have been rooting on this Tuesday night for the National League to beat the American League. When I was a kid, when I was a teen, and as I was entering adulthood, the National League almost always beat the American League. The National League had been beating the American League in All-Star Games since I was born. National League victories were my birthright. In my twenties, an NL victory was no longer a sure thing. By the time I turned thirty, the American League had been winning dependably for several summers. Except for a few oases of what I considered normality, my life since then has been pocked annually by the AL finding a way to win the All-Star Game…or the NL finding a way to lose.

At the end of the sixth inning this Tuesday night in July of 2025, the National League has this thing in the bag. Or so I almost think. Three of the four Mets who are on hand have seen to it that we — my team, my league — will win have already played. There’s a moment, in the fourth, when David Peterson grounds Aaron Judge to Francisco Lindor, who throws to Pete Alonso for the out. I couldn’t have adored it any more had that been, say, Bobby Murcer grounding out to Buddy on a pitch thrown by Tom. The All-Star Game was a throughline for me. Mets besting Yankees. National Leaguers topping American Leaguers. Little moments within bigger moments on nights when this was the only baseball anywhere. It didn’t count. It counted as much as I wanted it to. At the end of the sixth inning this Tuesday night in July of 2025, the National League has this thing in the bag. Or so I almost think. Three of the four Mets who are on hand have seen to it that we — my team, my league — will win have already played. There’s a moment, in the fourth, when David Peterson grounds Aaron Judge to Francisco Lindor, who throws to Pete Alonso for the out. I couldn’t have adored it any more had that been, say, Bobby Murcer grounding out to Buddy on a pitch thrown by Tom. The All-Star Game was a throughline for me. Mets besting Yankees. National Leaguers topping American Leaguers. Little moments within bigger moments on nights when this was the only baseball anywhere. It didn’t count. It counted as much as I wanted it to.

In the bottom of the sixth at Truist Park, my team’s home stadium for one night and one night only, Pete comes to bat with two runners on base and the NL ahead, 2-0. Kris Bubic is pitching for the American League. Kris Bubic is from the Kansas City Royals. I didn’t notice Kris Bubic over the weekend when the Mets were in Kansas City. Truth be told, I’d never heard of Kris Bubic. It’s not the summer of 1970 when I considered it my duty as a seven-year-old to know every star in baseball. I follow the Mets mostly. The stars I need to know I know. The stars I don’t know tend to be evanescent. Every year at these affairs there’s a slew of names that are new to me. Maybe they’ll be back next year. Probably not. but I will.

Still, Bubic is the pitcher, and Alonso is the slugger. Pete’s a big deal on the All-Star stage usually because he takes swings in the Home Run Derby. The Home Run Derby can be quite entertaining if Pete Alonso is in it. He’s the only reason I’ve watched it in recent years. It didn’t exist in 1970, so I’ve never developed an automatic affinity for it. Pete won it in 2019 and 2021. I was pumped. He didn’t enter it in 2024. I barely noticed it. Nonetheless, it’s given Pete a certain midsummer cachet, thus when Pete Alonso connects off Kris Bubic for a three-run opposite-field homer, it’s a big Polar deal. That’s Pete Alonso! That’s the guy who shines in the Derby! To me, that’s the first baseman for the New York Mets! A Met has put the NL up, 5-0! Two batters later, Corbin Carroll, one of those stars I know and one of those guys who’s one of my guys for a night, homers with nobody on and the NL is up, 6-0, and I’d say I’m a kid again, except I’m always a kid watching the All-Star Game. But this time I’m a happy kid, because for only the eighth time in the past thirty-seven editions of this thing, we are going to win.

And just when I’ve decided the National League has this thing in the bag, I shudder, because you just can’t allow yourself to think that way about a game you take seriously. I’m taking this All-Star Game seriously. I take every All-Star Game seriously. The rest of the kids from 1970 or whenever grew up and grew realistic. The All-Star Game is about everything but winning, about everything but upholding the honor of the senior circuit, about everything but associating yourself with the league you consider innately better and purer and whatever other qualities you deign to ascribe to one entity over another. Logically, I understand the All-Star Game has been continually watered down as a test of wills. The rival leagues have blobbed into one shapeless entity where everybody shakes hands or hugs. The Mets just played Kansas City in the regular season, for goodness sake. Every team uses a DH. Two of the Met players in whose designation as National League All-Stars I reveled, Lindor and Edwin Diaz, were American League All-Stars not that long ago. This is all branding and marketing. Nothing is sacred anymore, certainly not the Major League Baseball All-Star Game. And just when I’ve decided the National League has this thing in the bag, I shudder, because you just can’t allow yourself to think that way about a game you take seriously. I’m taking this All-Star Game seriously. I take every All-Star Game seriously. The rest of the kids from 1970 or whenever grew up and grew realistic. The All-Star Game is about everything but winning, about everything but upholding the honor of the senior circuit, about everything but associating yourself with the league you consider innately better and purer and whatever other qualities you deign to ascribe to one entity over another. Logically, I understand the All-Star Game has been continually watered down as a test of wills. The rival leagues have blobbed into one shapeless entity where everybody shakes hands or hugs. The Mets just played Kansas City in the regular season, for goodness sake. Every team uses a DH. Two of the Met players in whose designation as National League All-Stars I reveled, Lindor and Edwin Diaz, were American League All-Stars not that long ago. This is all branding and marketing. Nothing is sacred anymore, certainly not the Major League Baseball All-Star Game.

But I want to believe it is, and I want to believe the National League can maintain the 6-0 lead it has built as the seventh inning approaches. Everybody is wearing his team’s actual uniform, which is a welcome throwback. We have just seen a multimedia tribute to Henry Aaron, beamed live from the outskirts of Atlanta, so maybe that, too, is a sign that we’re going to have a 1970-style result if not 1970-style climax. Hammerin’ Hank started in Cincinnati 55 years ago. Charlie Hustle replaced him in the NL lineup.

Henry Aaron is gone. Pete Rose is gone. Fifty-five years is a long time. It’s 2025. Despite a couple of touches that tap you on the shoulder to remind you of what All-Star Games used to be — is that Joe Torre, who played alongside Hank and Pete at Riverfront that night in 1970, hanging out in the AL dugout? — it’s a far different game these nights. Gil Hodges used five pitchers over twelve innings. Dave Roberts in the seventh is up to his eighth, Adrian Morejon. Adrian Morejon is on the Padres. The Mets haven’t played the Padres yet in 2025, so whatever awareness I’d built up of his existence previously has faded. He could be Kris Bubic for all I know.

Morejon, I learn, isn’t the National Leaguer I want protecting a 6-0 lead. He walks two American Leaguers and gets replaced by Roberts’s ninth hurler, Randy Rodriguez. Rodriguez, of the Giants, gives up a three-run home run to Brent Rooker, of the Athletics. From 1968 to 2024, that would have had special resonance for fans in the Bay Area, except now, while the Giants are still San Francisco, the Athletics aren’t Oakland. Technically, they aren’t anywhere. This is the sort of thing that happens in baseball in 2025. Another thing that happens is the American League dragging this thing halfway out of the bag I thought it was in. The NL leads only 6-3.

Didn’t Trevor Hoffman blow one of these back in the “this one counts” era, when the All-Star Game was supposed to determine home-field advantage for the World Series? They came up with that doozy because one year, in 2002, the All-Star Game limped to a tie in the ninth, and the mangers — one of them Joe Torre — ran out of pitchers. Players had taken to bowing out of going, and players who played had taken to bolting the premises once removed, so something had to be done. In 2006, when the Mets appeared a marvelous possibility to represent the NL in the World Series three months hence, I cared even more that the NL win the All-Star Game. Hoffman blew it for us. That we didn’t make the World Series in 2006 remains immaterial in my grudgeholding.

Didn’t Billy Wagner blow one of these, too? That was in 2008, at Yankee Stadium. We couldn’t have a Met blowing an NL win at Yankee Stadium, but there he was, being every bit the big game bet Trevor Hoffman was two years earlier. In a couple of weeks, Billy Wagner will join Trevor Hoffman in the Hall of Fame. They were both great relievers, except on midsummer nights when many were watching. I was gonna say “when everybody was watching,” but fewer and fewer watch the All-Star Game every year since 1970. Me, I keep watching, because I watched when I was seven, when Pete Rose bulled Ray Fosse out of his way, and the NL won in twelve. I never had to be marketed to again. My brand loyalty was set.

Randy Rodriguez remained on the mound long enough to give up another American League run. Now it was 6-4, NL. Tylor Megill’s brother Trevor, our tenth pitcher, got us out of it. Managers no longer manage to win the All-Star Game. Managers manage to ensure everybody gets into the All-Star Game. David Peterson could have gone another inning, but the each out any one pitcher records is one less somebody else can’t. I wish my day camp counselors in the summer of 1970 ran our games with such attention to individual feelings. I’m glad Gil Hodges ran the All-Star Game as he did.

Two more pitchers got the NL through the eighth intact. Two more pitchers did no such thing in the ninth. The second of them was Diaz, who didn’t pitch badly, but he came in with a runner on second and one out, our league’s lead whittled down to 6-5. Matt Olson made a helluva play on a hot Jazz Chisholm grounder, much as Pete Alonso made a helluva play on a hot Jarred Kelenic grounder last September. Then, Diaz didn’t cover first and the entire Met season nearly came tumbling down as a result. Now, Diaz covered first, and a second out was ensured. Progress. But Bobby Witt, the runner Edwin inherited, crossed over to third, setting him up to come home on Steven Kwan’s ensuing dribbler, no bowling into the catcher necessary. We were all tied up at six. Kwan proceeded to steal second because everybody proceeds to steal second when Diaz is pitching (unless he has Luis Torrens, Francisco Lindor and replay review working in his favor). Randy Arozarena was up. Edwin struck him out by first throwing a borderline ball on oh-and-two and then patting his head while rubbing his tummy, the signal for the robot ump to change the call of the human ump. This All-Star Game tested that same system we saw in Spring Training. It got Edwin out of trouble, so I’d say it worked.

The National League didn’t score in the bottom of the ninth. While the half-inning was in progress, the telecast showed Pete Alonso taking swings in a batting cage. My first instinct (and, I’m pretty sure, those of the uninformed announcers) was to admire Pete’s work ethic. He was out of the game, but he was using his time in a ballpark to stay sharp for the second half of the regular season. What dedication! Then, in a flash, I remembered that I didn’t have to worry about whether Diaz was going to have to pitch the tenth — Roberts had used every pitcher — because if the NL didn’t score right here and now, there’d be no tenth inning. Alonso was warming up for what loomed just over the horizon.

There would be no 2002-type tie. This time what would count would be a mini-Home Run Derby. They even had a cutesy name for it: the swing-off, like the page-off in 30 Rock, except no young lady in a blazer and a skirt would run through the halls ringing a bell. Or maybe she would. We’d never had a swing-off to conclude an All-Star Game, but after Brendan Donovan fouled out to end the ninth, we would.

Apparently, Roberts and his counterpart, Aaron Boone, had been instructed before the game to choose three sluggers to come out and take three swings versus their own league’s batting practice pitcher. But not just any three sluggers. If certain sluggers had already dressed and boarded private jets, they wouldn’t be summoned to return. No Ohtani. No Judge. No kidding. Nonetheless, it was all very festive the way it was presented. Each manager revealed to Kevin Burkhardt who his sluggers were gonna be. One of Roberts’s, batting third, was gonna be “the Polar Bear”. Pete Alonso is so famous in these circles that there’s no need for elaboration.

The swing-off immediately occupied a space between “ohmigod, they’re really doing this!” and “what the [bleep] is going on here?!?!” It was better than a tie. It was better, maybe, than a ghost runner on second, especially since there was nobody left to pitch. In 2008, at Yankee Stadium, hours after Billy Wagner couldn’t retire the AL without a ruckus, the leagues pushed the envelope of availability for fifteen innings until the NL was ready to put David Wright on the mound for the sixteenth. It strained credulity that position players were going to pitch in an All-Star Game then. Now? When it’s mildly surprising that pitchers are allowed to pitch at all ever? No chance anybody takes a chance with anybody’s arm.

Goodbye, All-Star extra innings. Goodbye, win at all costs. Goodbye, this particular legacy of Pete Rose. Like almost everything about Pete Rose, this legacy required parsing. No player burned more to win. You had to love that, especially if you were seven and he was on your team for one night. But was the All-Star win something worth wrecking Ray Fosse’s season over? Fosse’s shoulder was separated and he was never the same player again. That, however, was how the game was played in those days, the All-Star Game included. Catchers don’t block plates sans ball anymore. It’s been legislated from existence. It’s not necessarily a bad idea if you think about it. Or maybe you don’t wanna think about it. Maybe you just want everybody to be hellbent to win every night, All-Star Games included.

Hello, swing-off. Hello again, Brent Rooker of the Athletics from nowhere. Rooker got the AL back in the game, then he got the AL off to a 2-0 swing-off lead. The NL countered with Kyle Stowers of the Miami Marlins. The Mets last played the Marlins in April; forgive me for a lack of Kyle Stowers consciousness. He got one for the NL. Up for the AL came Arozarena. Only one of his swings was for a homer (with no outfielders tracking balls, it was hard to tell at first what was or wasn’t going out), so the AL now led, 3-1. The NL’s second slugger was gonna be Kyle Schwarber. I’m not in the habit of rooting for Phillies, but on Tuesday nights like these, there are no Phillies, no Marlins, no Braves. We are one big National League family.

Cousin Kyle bombed his BP pitcher, a fellow from the Dodgers named Dino Ebel — I swear I thought Joe Davis kept saying “see no evil” — with each swing he took. On Schwarber’s final lunge at glory, when he went down on one knee to get ALL of it, my instinct was to worry that he could get into bad habits swinging like that. Then I remembered swinging like that is what was encouraged in a home run derby, and, besides, what do I care about Kyle Schwarber’s habits being good? All I cared about in the moment was the NL led the AL in the swing-off, 4-3.

Which meant I cared about two things next:

1) What the AL’s final batter, Jonathan Aranda of the Rays, was going to do in his three swings.

2) The fate of the NL’s final scheduled swinger, the Polar Bear.

My NL instincts demanded Aranda — never mind that he’d played in the preceding game; I’d already forgotten who he was — must be foiled completely by his own BP pitcher, some dude Boone brought from the Yankees. My Met instincts kind of wanted to see Alonso come up and win the damn thing for us. For all of us. A little of me worried Pete would pick this moment to go into a home run drought, but more of me hoped he would ice it for the NL, and lay claim to the MVP trophy.

Alonso hit that three-run homer in the sixth. That was the biggest hit of the night, at least until Rooker hit one of his own. But if the National League won, they’d have to give the prize to Pete, wouldn’t they? And if Pete didn’t get to hit in the swing-off? There was no precedent on which to rely here. This was all new, all very postmodern.

Jonathan Aranda almost hit one ball into the seats. Had Truist Park not been designed with a brick wall over its right field fence, he would have, but the architects probably weren’t thinking about a swing-off someday deciding an All-Star Game. Or perhaps they were incredibly prescient. Either way, Aranda went 0-for-3, which meant the NL won the swing-off, 4-3, and the game itself, 6-6, not a typo. Kyle Schwarber, it occurred to me, was evoking the spirit of his Phillies’ predecessor Johnny Callison, who won the 1964 All-Star Game for the National League with a ninth-inning three-run blast, what we would come to call a walkoff homer. That game was at Shea Stadium. Callison grabbed a Mets batting helmet to do his swinging, because the powers that be weren’t fanatics (or Fanatics) about who wore what way back when. The players, however, were fanatics about competing. Callison hit his game-winner off Dick Radatz of the Boston Red Sox. Radatz was known as the Monster. Radatz was trying to get him out. Ebel was attempting no such thing versus Schwarber.

So, no, this wasn’t anything like Johnny Callison, but they gave Kyle Schwarber the MVP trophy, anyway. He didn’t do anything of note in the actual All-Star Game, but we all just saw what he did to decide the All-Star Game. My Polar bias notwithstanding, I couldn’t argue with Schwarber being declared Most Valuable. I also couldn’t quite get behind it, same as I guess I’m glad the National League won its eighth All-Star Game in the past thirty-seven, but did they? They won on a swing-off. There had no been such thing as a swing-off a half-hour earlier. Now we were determining league supremacy by it. So, no, this wasn’t anything like Johnny Callison, but they gave Kyle Schwarber the MVP trophy, anyway. He didn’t do anything of note in the actual All-Star Game, but we all just saw what he did to decide the All-Star Game. My Polar bias notwithstanding, I couldn’t argue with Schwarber being declared Most Valuable. I also couldn’t quite get behind it, same as I guess I’m glad the National League won its eighth All-Star Game in the past thirty-seven, but did they? They won on a swing-off. There had no been such thing as a swing-off a half-hour earlier. Now we were determining league supremacy by it.

Huzzah?

Not quite. After fifty-five years, I’m out. Not out of baseball, and not out of the All-Star Game as something I tune into or something I obsess on for a few minutes at a time every July in terms of what Mets are named and what Mets aren’t (think Juan Soto couldn’t have done what Schwarber did?). I mean I’m out on taking its result seriously. I may have been the last adult in America to get the memo that it didn’t matter, the last to sit through all the pregame folderol — “they could have played three innings by now,” I told Stephanie during the extended introductions — because I was still anticipant that the NL was going to beat the AL. Even in the years when the AL seemed designed to beat the NL with its fewer teams and deep well of offense, I still looked at the Midsummer Classic the way I did when I was seven. On some level within me, this mattered. The National League mattered. The American League, as much as I disdained it, mattered. A game between the best of each league mattered. Interleague didn’t ruin that. Uniting the umpires and everything else under the MLB umbrella didn’t ruin that. The swift movement of players from team to team regardless of league didn’t ruin that.

The swing-off ruined that. The swing-off could rightly be viewed as “fun,” within the context of what is and what has always been an exhibition, but as someone rooting the way I have for so many midsummers, I heard myself ask myself, as I watched every visible National Leaguer jumping up and down for joy, “What the hell does fun have to do with the Major League Baseball All-Star Game?” To this curmudgeon, the swing-off proved nothing, other than Kyle Schwarber is really good at hitting the pitches Dino Ebel tees up for him. Mazel tov to both gentlemen. Had Pete Alonso been the batter to take those swings and send them beyond the fence, I would have loved him doing so, but I don’t think it would have changed how it all landed on me.

From cheering Pete Rose scoring in 1970 to awaiting Pete Alonso swinging in 2025, I was into it. It was a good run, but at last it’s barreled into a sense of dismay I find immovable.

by Jason Fry on 14 July 2025 10:40 am And on the last day of the first half,* the Mets presented us with a fan’s oldest philosophical conundrum: Is it better to come back and lose, or not to come back at all?

The philosophy lesson came at the very end: Before that, the Mets followed one of their more frustrating 2025 scripts, in which ducks on the pond are some sort of ASMR thing that puts the rest of the lineup into a blissful doze. A one-out Mark Vientos first-inning triple yielded nothing. Ditto for Ronny Mauricio‘s single leading off the second. First and second with one out in the fourth? Nada. I could list all the souffles that fell, but you get the idea.

Alternate narrative, because sometimes it’s not always about us: Young Kansas City hurler Noah Cameron was electric, fanning eight Mets and stepping up when needed, and he got superb infield defense behind him. (The Royals’ outfield? Not so much. In fact, yikes.)

Meanwhile, Clay Holmes was fine for the Mets and Sean Manaea was better making his season debut in a piggyback role: Manaea gave up a single to the first batter he faced, Bobby Witt Jr., but then fanned five of the next six.

In the ninth the Mets dug in against Carlos Estevez, who by now must be seeing Mets in his nightmares, and rose up in self-indignation — assisted by whatever it was the Royals were doing out there in the outfield. Mauricio doubled to left over the head of Nick Loftin, whose Cedeno-esque route around the ball made you want to cover your eyes, Jeff McNeil tripled just past the glove of Kyle Isbel in center, and Jared Young brought McNeil home on a sacrifice fly that was just long enough.

Just like that the Mets had tied the game, and all they needed was for Manaea to keep the Royals in check for another half-inning. Francisco Lindor would be the Manfred man in the top of the 10th, with Vientos, Juan Soto and Pete Alonso behind him, and…

…and not so fast. Manaea got the first out of the ninth on another strikeout, but modern-day Herb Washington Tyler Tolbert served a pretty good pitch to right and then stole second. Loftin then hit a well-placed slider at the bottom of the zone just over the infield, and just like that the Mets had gone into the break with a loss.

Manaea pitched well for a club that could really use what he brings to the starting rotation. Neither of the pitches that undid the Mets were ones he’d want back. The Mets pulled off another late-inning comeback. All of these are good things.

And yet they lost. So what do you think? Better to have watched Royals outfielders do what they don’t do enough and go down 2-0? Or better to have fought back and still been dispatched? The scribes have argued this one ever since town ball took shape on some long-forgotten English village green; they’ll be arguing about it when baseball is played on Mars and aboard space stations. Sunday was just another stitch in the tapestry of what-ifs and OK-buts, with so much left to weave.

* They’ve actually played 97 games, which is 60% of a season, but nobody needs to hear from That Guy.

by Greg Prince on 13 July 2025 12:53 pm The Mets are a half-game in first place as the final action before the All-Star break approaches. That seems appropriate, given that so much of the Mets’ good fortune seems to depend on opposing baserunners being the equivalent of no more than a half-step off a base while a Met fielder’s tag is touching him. Actually, a half-step would be a generous measurement. Try a half-inch, if that much.

The latest example came Saturday afternoon in the bottom of the eighth at Kauffman Stadium. The baserunner was the Royals’ Bobby Witt, who had walked with one out. Edwin Diaz is having a glorious season, but he still walks guys, and the guys he walks tend to run. Luis Torrens knows that. Francisco Lindor knows that. Harrison Friedland knows that. You probably know several of those Met names intimately and one in passing. The name Harrison Friedland passes through our consciousness every time there’s a close play on the basepaths, usually at second.

Witt was heading there in the eighth, where Lindor was waiting for Torrens’s throw. Friedland, the Mets’ analyst of video replays, was the most interested of observers, at least as interested as second base umpire Alan Porter. Porter thought Witt was safe. Couldn’t blame the ump. The Royals’ superstar looked supersafe.

Hey VR, we’ve got your Sportsperson of the Year. But our replay supervisor has super vision. Witt, he divined, might have breathed just enough to have removed some scintilla of his body from the bag in the process of sliding onto it. Challenge the call, Friedland advised bench coach John Gibbons over the replay hotline. Gibby passed the word to Carlos Mendoza. Mendy made with the earmuffs motion. Say what you will about the replay rule, but it has given us a wonderfully silly gesture that carries within it the power to alter the course of innings, games, and seasons.

Our favorite gesture, however, is the fist pump we make when an opponent’s stolen base is microscopically examined and eventually overturned. We may feel a little less than clean if he’s ruled out on the tickiest-tackiest video judgment call, but is it our fault MLB hasn’t instituted some kind of force field mechanism that proclaims, He was on the bag for 99.99% of that slide, don’t be swayed by the 00.01% that’s clearly incidental to the play? They wanna call runners out for the teensiest bit of daylight, provided a ball gets to the base and a tag stays on the guy, we’ll take it.

Good execution as always from Luis and Francisco. Outstanding microscope peering yet again from Harrison. Witt gets erased. Royals have two outs. Diaz gets the third, and then comes back for the ninth. By then, the 2-1 lead he was protecting is 3-1, and his two-inning save he’s attempting is en route to completion.

Great second game of a three-game set in Kansas City. Juan Soto blasted a home run that turned their fountain into a wading pool. Frankie Montas was Montastic for five innings. Middle relief in the sixth and seventh, from Reed Garrett and Chris Devenski, respectively, warded off Royal spirits. Tight defense from Tyrone Taylor and Luisangel Acuña prevented leaks. Jeff McNeil, when he knocked in Pete Alonso with a ninth-inning run insurance run, could have bumped Flor Cawley as State Farm Agent of the Day. And, perhaps most helpful of all, we had our video guy working marvelously within a system that allows for a video guy to do a thing we wouldn’t have guessed would exist when we fell in love with baseball.

Yet there he is and there it is. The Mets are first-place team by a half-game because sometimes a half-inch makes all the difference.

by Greg Prince on 12 July 2025 1:15 pm Surely you’ve been told at some point in your life, “Get some rest and you’ll feel better.” I felt fine in the bottom of the sixth Friday night, though I’d felt better before the Royals tied the Mets at one apiece. The part of the rain-delayed game in which Kodai Senga pitched four scoreless innings in his return from the IL made me feel superfine, actually. The lone Met run coming across on a bases-loaded walk issued by Old Friend™ Michael Wacha to Pete Alonso in the third felt OK, though just OK. Pete belting one would have felt fantastic. So would have Juan Soto doing something of that nature, except he struck out prior to Pete’s at-bat. A Mets fan always feels the heart of the order should beat more loudly.

Mostly in the bottom of the sixth, I felt sleepy, thus I closed my eyes and missed the seventh inning, the top of the eighth, and however the bottom of the eighth started. Not that I knew the bottom of the eighth was in progress as I stirred. All I knew when I roused to consciousness was a commercial was on TV. I didn’t know what time it was, because the clock I rely on to tell me that at a glance after I nod off — the clock that has centered three separate living rooms of ours over the past almost 34 years — recently stopped operating. Changing batteries hasn’t worked. Tapping it purposefully hasn’t worked. Sweet-talking it back to ticking and/or tocking hasn’t worked. The clock was a wedding gift from a relative on my father’s side of the family. Its sentimental value is a product of its longevity. It’s our clock. Other methods of accessing the time are easily available to us, but we like our clock. Now it’s an ornament, perched atop a standard-definition television whose purpose these past two baseball seasons is to sit quietly behind the high-definition model we installed so we can consume media like modern folks do. The SDTV, acquired in June 2004, still worked as of January 2024, but it didn’t do enough, so we finally moved on to the kind of thing most people look at. Ol’ Boxy behind it is too heavy to move without calling a coupla guys. That dependable television of yore has therefore become a shelf for a clock that no longer tells time.

And maybe Vientos got fixed. The commercial I woke to was for a car. I don’t know what kind of car (I can’t stress how not up to date I am when it come to cars), but it was high-end enough to hint that I wasn’t watching in the middle of the night. If it was the middle of the night, an infomercial would be on. More likely there’d be a message on my HDTV to PRESS ANY KEY, because energy-saving mode would have shut off active programming. It couldn’t be terribly late, I figured. Maybe the game is still going. Or we might be in the postgame show. The car commercial would drive off into the sunset, and then Gary Apple would speak in the past tense. I’d hate to think I’d slept through the conclusion of the game. Or maybe I’d hate to find out how the game turned out.

Rewinding the DVR struck me as an option. Or just grabbing my phone. Welcome to the second quarter of the 21st century, pal. It’s all right there on your device. You’re staring at clocks that aren’t running before figuring out how the Mets should make you feel. Get with the times.

Royals 3 Mets 1. Bottom of the eighth. Like Mr. Magoo in A Christmas Carol, I learned it wasn’t too late. But I did learn the Mets were losing, and that didn’t feel great. Bobby Witt had homered while I napped. Ouch.

Commercial break ends. Eyes open a little more. Steve Gelbs speaks. Carlos Estevez is on for the Royals with the bases loaded. Hey, Steve nudges Ron Darling, remember Carlos Estevez from last October? Carlos Estevez…I’m still sleepy, Steve…just tell me. He gave up that grand slam to Francisco Lindor. Good sign, maybe.

Alonso strikes out. So much for signs. Mark Vientos is up with one out. Mark Vientos up hasn’t been a good sign at all this year. Earlier in the game, when I was fully awake, Mark struck out and took it out on his bat at home plate. They showed that replay multiple times. It was dramatic video. But not as dramatic as what Vientos did against Estevez, doubling into the right-center gap. All three Mets on base, including dashing when he wants to be Soto, score. We go from down, 3-1, to up, 4-3. I go from wanting to turn the TV off and fall back asleep to determined to stay up.

The Mets were determined to make awake the way to be. In the ninth, against Taylor Clarke, Lindor launched a fly ball that just cleared the fence between center and right. It counted as a three-run homer. And as I debated whether this was a secure enough lead that would allow me to snooze in peace, Soto did something very similar. His fly ball was to the left of center, but it also went out. Now it’s 8-3. Now I don’t want to sleep quite so soon. I hang in there with Chris Devenski getting the final three outs and stick around for Vientos smiling with headphones on (Gelbs has to interview him from the booth since SNY didn’t spring to station an auxiliary Gelbs in KC), then treat my drowsy self to Apple’s postgame show. My favorite part is when Other Gary goes to commercial by saying, “More to come,” and I reflexively respond, “Mordecai.” I doubt it’s anybody else’s favorite part. The more that came, Mordecai, was Carlos Mendoza agreeing with reporters that it was a big game for Mark, then Kodai Senga and his interpreter assuring the same scrum that all is good on the ghostforker’s end. Plus the Phillies lost and the Mets are only a half-game out, and at least for a night, all is well. Either all is well or not at all well when it comes to these Mets. Take the good night’s rest when the Mets provide it.

by Greg Prince on 11 July 2025 12:59 pm I would like the Mets to be loaded with nothing but stars who win every game by lots of runs, pitched daily and/or nightly to victory solely by stalwarts of the starting rotation. Sounds ideal enough.

Now for reality.

The Mets don’t win every game. Nor does anybody else, but the Mets have gotten out of the habit of winning most of their games. Four Fridays ago, they entered their weekend series 21 games above .500. On this Friday right here, they are twelve games above .500. In nearly a month’s time, they’ve gone 8-17, including Thursday’s afternoon and evening losses at Camden Yards. That’s roughly a sixth of the season played at a pace that would win you 52 games out of 162. Good thing the part where they went 45-24 counts just as much (more, actually) toward their overall record of 53-41, but this is not a positive trend. The Mets are not only a game-and-a-half out of first place in a division they once led by five-and-a-half, they are no longer the National League’s top Wild Card, and their edge over the nearest provisional non-Wild Card contender is a mere two-and-a-half games.

Keep losing as often as they have for the past month, and 162 games may be all the Mets play in 2025.

This is despite the Mets being relatively star-spangled. Before getting swept by the Orioles, they were going to be represented in Atlanta next week by three All-Stars. After losing the daytime portion of the split-admission doubleheader, they learned they’d send four. In addition to Pete Alonso, Edwin Diaz, and Francisco Lindor, we’ll see David Peterson make the Midsummer Classic scene, a surprise in that he was overlooked in the initial knighting phase, yet very reasonable given how he’s pitched. Congratulations are in order for the fifth Met to earn a first-time nod in his sixth season as a Met. (To find out who the others were, check out this comprehensive rundown.)

Peterson gave the Mets one of his better performances of the year in Thursday’s opener, taking a shutout into the eighth inning, nursing a 1-0 lead. The one run was provided when Tyrone Taylor doubled home Brett Baty from second in the fifth. Taylor had helped make certain the Orioles would still be carrying a zero at that point when he gunned down Jordan Westburg attempting to go from first to third on a Ramon Laureano single in the fourth. Taylor’s no star, but he is capable of playing like one a hit or a throw at a time. That’s the kind of contribution you need when your stars disdain clutchness for an entire game. The recently branded Fab Four of Lindor, Alonso, Brandon Nimmo, and Juan Soto combined to go 2-for-14.

It was a little surprising to see Peterson start the eighth. Not unwarranted, just surprising. David had thrown 87 pitches through seven. For some pitchers, this would be enough. For some managers, this would be cause for a handshake and an ass slap. For Carlos Mendoza, it was gray area. He wanted Peterson to keep pitching in the eighth, but he didn’t want to fully trust him. When Petey gave up a well-placed single to start the eighth, Mendy’s trust dissipated. Could the man who scattered five singles and walked nobody get out of a one-on, no-out situation? The manager decided to not find out.

Ryne Stanek was the new pitcher. Gunnar Henderson was the pinch-hitter. Orioles 2 Mets 1 was the score after Henderson, in for the Orioles because Mendoza had gone to a righty, swung and connected for a two-run homer. A splendid day of All-Star work had flown practically into a vat of Boog’s BBQ sauce. Fortunately, Stanek didn’t give up any more hits. Unfortunately, he walked four, which, with a sac fly mixed in, led to another run.

Baltimore carried a two-run lead to the ninth and kept it, winning, 3-1. The Mets are a pretty good 18-12 in one-run games in 2025. I forget whether that’s supposed to mean the Mets are gritty or lucky. There’s a school of thought that says teams that win more one-run games than they lose show the intestinal fortitude and superior talent to be champions. There’s another school of thought that suggests every close result speaks to the random nature of baseball and perhaps life. Whichever it is this week, I’ve come to lumping together one- and two-run games as pretty much the same thing. Each kind is close. Each kind feels as if it can turn on one swing or pitch or bounce or judgment call or managerial decision. This kind of two-run loss felt like it turned on just enough going wrong to stick the Mets with the L.

In two-run games this season, the Mets are now 8-10. In one- and two-run games this season, the Mets are now 26-22. You’re welcome to Rorschach that data as you wish. Me, I see too many potential wins that have wound up losses. A few more swings or pitches or bounces or calls or decisions that go the Mets way — some within the Mets’ conceivable control, some the product of this or that going here or there — and the Mets are still in first place, still comfortably planning with an eye toward October.

The second game Thursday did not have a close final score. It went Orioles 7 Mets 3. Not a blowout loss, but not so competitive that one or two pivot points gnaw at you. Perhaps the game was decided when the Mets opted to start Brandon Waddell. I’ve just cast an aspersion Waddell’s way, but didn’t mean to. Brandon Waddell has been useful in middle and long relief this season when given the chance. I applaud anybody who is useful in middle and long relief. I applaud anybody given the chance to flourish in that role being given more of a chance. Brandon Waddell has been optioned three times this season. It’s tough to build up momentum when you don’t know how long you’ll be around.

After four relief stints totaling 9.2 innings spread out over 11 games between June 25 and July 6, the Mets handed Brandon the ball to start the nightcap on July 10. By my count, this marked the eighth time in 2025 that the Mets have gone with what I’ll call an unplanned starter. You have your rotation. You have what you consider your rotation depth. Then you have instances when pitchers fall out of your rotation, usually from injury, and pitchers you thought would provide you depth get hurt or prove too ineffective to try again. That’s when you roll the dice that one of your steadier relievers (Huascar Brazoban thrice) can be as effective in the first and maybe second inning as he usually is later. That’s when you tap a less than fully ripe prospect (Blade Tidwell twice) to get here ASAP and try his luck. That’s when you all but shrug and hope you can get a handful or more of outs from a Justin Hagenman or a Chris Devenski or a Brandon Waddell, and by then, there’ll be fewer outs to get, and maybe somebody else can get the bulk of those. If the lineup is hitting, you’ll make it through the day. If the lineup isn’t hitting, the day will be over eventually.

The Mets are 2-6 in games when they’ve turned to unplanned starters, including Waddell’s attempt to plow through innings at Camden Yards. Brandon notched three of them, giving up three runs in the process. If the Mets were producing, the shrug would have paid off. The Mets weren’t much hitting. In the first inning, they were. Nimmo singled, and Lindor doubled to put Nimmo on third. What a perfect setup to get things going. True, in the first game, the first inning began very similarly. Nimmo had singled, Lindor had walked, and a passed ball advanced them each a base. In that first inning, 41-year-old Charlie Morton sipped from the fountain of youth prior to striking out Soto and Alonso and popping up Jesse Winker. And that, except for Taylor doubling in Baty, was that for the Met offense.

But that was the first game. Doubleheaders, like baseball seasons, are packed with opportunities for redemption. Second games need not follow the trajectory of first games. And in the second game, the Mets did not leave the first inning emptyhanded. Versus Tomoyuki Sugano, Juan Soto and Pete Alonso each drove in a run. Huzzah? Well, a run is a run, and the Mets had two of them. But to killjoy the buzz, Soto’s RBI came about via a groundout and Alonso’s arose from a flyout. Jeff McNeil made the third out. The rally was over. The threat evaporated. Its likes would be seldom seen again.

Waddell left after three, trailing, 3-2. In the fourth, the Mets pieced together a tying run. A walk. A steal. Another walk. An honest-to-goodness two-out single with a runner in scoring position, from Baty. That was something.

That was all. Another dribble of activity, in the top of the fifth, culminated in Alonso leaving runners on first and second. Hagenman, in his second inning of work, gave up two runs. In the sixth, Justin, Dicky Lovelady, and Rico Garcia — unplanned relievers are a given with this team — combined to allow two more. The Mets stopped bothering Sugano by the sixth, and the rest of the Oriole bullpen didn’t have to sweat a whole lot en route to Baltimore’s 7-3 win.

It’s tempting to pin Met shortfalls on those paid the most to come through the most. In the first inning, the Fab Four functioned adequately. Later, maybe not so much. Overall, however, it takes a village to drop a doubleheader, whether day-night or traditional. The Mets went 2-for-19 with runners in scoring position across eighteen innings of futile baseball. No, not enough production from Nimmo, Lindor, Soto, and Alonso. But also not enough anything on a consistent basis from anybody else. The Mets are not solely a starshow. What’s been nagging at me is there’s a hollowness to the supporting cast this year. When everybody’s healthy, which isn’t now (Winker seems destined to join Starling Marte on the IL), the Mets offense appears plenty bolstered by above-the-marquee bona fides. The NL didn’t say so this year, but Soto is a star. The NL has never said so, but Nimmo qualifies in our eyes as a star. Alonso and Lindor have those stellar credentials. McNeil and Marte have had them in reasonably recent memory.

That leaves three other categories of Met position player: those who are working their way up to whatever their level will be; those who have found their level somewhere south of stardom but north of disposable; and those who are clearly reserve types. A fourth category is fringe player, but the fringe player (à la the DFA’d Travis Jankowski) isn’t really intended to be here any more than Brandon Waddell is intended to start games let alone salvage nightcaps.

As they continue to work their way up to whatever their level will be, patience will be required to shake out the fates of Baty, Ronny Mauricio, the lately returned Luisangel Acuña, and the mostly flailing Mark Vientos. You can throw starting Syracuse catcher Francisco Alvarez into that stew, too. Baty was the most promising and productive of the kids — yes, they’re still kids — on Thursday. Mauricio has looked the liveliest in all facets of the game, though that shipment of polish he desperately needs must be tangled up by supply chain issues. Acuña is tantalizing, but his role is murky in the present. Alvarez’s Broadway revival is TBD. Vientos is the true enigma of the bunch. So good when it mattered most in 2024. So invisible in 2025. When Winker had to sit with a tight back in the opener, Vientos was thrust into sudden DH duty, and all at once, he was stinging the ball. Maybe this was the push he needed to get back to where he once belonged. In the second game, he was a nowhere man.

But let’s leave the kids be for a moment, and think about the roster’s hollow middle. You have Taylor, who’s the best defensive center fielder the Mets have brandished since Juan Lagares. His RBI double in the first game was especially encouraging because it felt practically unprecedented. Even following his spiffy Thursday afternoon, none of the components of Tyrone’s slash line are flattering; his OPS of .575 reflects that he’s very much in there for his glove. His bat is why McNeil is so frequently a center fielder.

Anybody else in the middle? Winker (2019 All-Star selection notwithstanding) comes to mind when healthy. He hasn’t been. Jose Siri comes to mind when healthy, but when was the last time he was healthy? Luis Torrens does wonderful defensive things behind the plate, but in the best-laid Mets-hatched plans, he’s clearly a reserve type. Given the job full-time, or as full-time as any catcher can be, you’d get used to his Tayloresque .583 OPS in exchange for all those runners he throws out and tags, especially if most among the eight other guys in the lineup were responding to runners on base consistently.

They’re not. So Torrens’s and Hayden Senger’s shortfalls when batting can’t be easily dismissed. Or Taylor’s. And that’s the extent of the Met middle class on the current roster, assuming Winker will be out a while. Like America, the Mets’ middle class is shrinking, and there’s not a lot the elites are doing to raise tides and lift all boats.

My attempt at analysis is a response mostly to getting swept by an underachieving Orioles team on a Thursday, and partly the other realities cited. The Mets haven’t been awesome at winning close games since the season commenced. The Mets haven’t been awesome at deploying confidence-inspiring starting pitchers from the get-go, but enough of them won us over to let us forget the depth wasn’t that deep. The healing of Kodai Senga and Sean Manaea might change attitudes fast on that count. They, with All-Star Peterson, mostly consistent Clay Holmes (pending his innings ceiling), and semi-dependable Frankie Montas reads like an actual rotation. Still, the Mets haven’t been and still aren’t awesome at driving in baserunners, whatever the caliber of the batter not coming through. And bullpens are bullpens. Some days you’re thrilled that a Ryne Stanek pitched. Some days you’re satisfied that a Brandon Waddell got a chance. Other days you’re left to rationalize that bullpens are bullpens, especially days when your All-Star closer is not asked to further burnish his reputation. Falling behind by two in the eighth in the first game. Losing by four heading to the ninth in the second game. No rising to meet the moment in either game. Diaz will be well-rested for Kansas City.

Of late, it’s been a bit of a mess. On the whole, it’s a team that’s done very well sometimes, can be doing better other times. In the long term of 2025, we wait to find out for sure who the Mets really are. It’s like that as most seasons creep toward the break. Promotions percolate. Trades loom. Unknowables get known. We know that, yet we also kind of want to know in advance how everything is going to turn out.

by Jason Fry on 9 July 2025 12:18 am So you want to be a big-league pitcher?

Baltimore’s Brandon Young entered the game sporting an ERA north of seven — hmm, come to think of it that’s less “sporting” than “lugging” or “enduring.” But there’s a reason they actually play the games: Young looked terrific against the Mets, allowing just a pair of hits in the first four innings and posting an immaculate inning in the fifth — nine pitches, three strikeouts, no fuss.

So of course Young came out in the sixth and gave up a Ronny Mauricio home run, a Brett Baty double and a Brandon Nimmo double, which is pretty much the opposite of an immaculate inning. Before Young had quite figured out what had happened, he’d been undone over the course of seven pitches and was out of the game on the short side of a 2-1 score.

That 2-1 score was also on the ledger of Clay Holmes, who’d looked solid through five though pitch counts in the 80s are still relatively new terrain for him. Holmes’s sixth wasn’t exactly immaculate either: hit batsman, single, single, two-run double, two-run single. He departed the game having turned a one-run lead into a three-run deficit, with the dreaded line “pitched to 5 batters in the 6th” appended to the box score.

The air looked like it had come out of the Mets’ balloon, with newcomer Alex Carrillo surrendering a Jackson Holliday lead that made the gap a little wider. Carrillo’s journey is a bizarre one, particularly in today’s digital- and scout-heavy game: Before this season, his experience in organized baseball consisted of 4 1/3 innings of rookie ball in the Rangers’ organization back in 2019. After sitting out the Covid year, Carrillo sandwiched stints in indy ball around two seasons in the Mexican League. None of those tours of duty were particularly successful, but he worked with a pitching lab and got in shape, and was throwing triple digits in Venezuelan winter ball when someone tipped off the Mets. They signed him, like what they saw in Binghamton and during a toe touch at Syracuse, and now here he is.

(For those of you worried about which baseball card represents Carrillo in The Holy Books … well, I’d like to put your mind at ease, but it turns out Carrillo has never had one.)

Carrillo got a little scorched in his big-league debut, but Bryan Baker got burned. Facing the Mets in the eighth, he gave up a single to Nimmo, a two-run homer to Francisco Lindor, a single to Juan Soto and a game-tying two-run homer to Pete Alonso — the most impressive showing from the Mets’ Big Four this season, and a reminder of the damage this lineup was constructed to do.

With the game tied, Reed Garrett escaped a heavily trafficked inning with help from a nifty double play started by Mauricio. Edwin Diaz navigated the ninth on just 10 pitches and the Mets immediately cashed in Lindor as the Manfred man, as Soto hit Yennier Cano‘s first pitch through the infield to bring him home. Alonso singled and Travis Jankowski (pinch-hitting for Mark Vientos, hmmm) bunted the runners over to second and third, but the Mets stubbornly refused to add to their one-run lead — and Carlos Mendoza then opted not to send Diaz back out, instead opting for Huascar Brazoban with the speedy Holliday as Baltimore’s ghost runner and the middle of the Orioles’ order coming up — pretty much the same setup Cano had inherited.

Hmm, I said from my seat next to my mom in her apartment. Hmm, you probably said from wherever you were sitting — or perhaps it was a more emphatic expression of doubt. After all, Brazoban has elite stuff but replacement-level confidence in that stuff, and a whole parade of the night’s pitchers were on hand to remind him of the perils faced from the mound.

So of course, baseball being baseball, Brazoban fanned Jordan Westburg on a mean changeup, coaxed a foul pop from Gunnar Henderson, and got Ryan O’Hearn to hit a room-service grounder to Jeff McNeil at second. Holliday only moved from his post near second to trot disconsolately into the dugout with the game over while the Mets did their circle kick line and grinned and took pride in a solid night’s work. Pitchin’ ain’t easy; it ain’t predictable either.