The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 25 May 2021 8:32 am It’s presumptuous to project thoughts onto the deceased. The deceased can’t speak for themselves, yet we the living haughtily decide what they might be thinking if they were still with us. I do anyway. For a decade now, I’ve done it with Dana Brand.

Though it’s presumptuous as hell, I do it because I miss Dana. Dana was a wonderful Mets writer and a wonderful Mets companion and a wonderful Mets fan. We actively knew each other for only a few years before he passed away out of nowhere at the age of 56 ten years ago today. We spiritually knew each other as Mets fans all our lives.

So forgive my presumptuousness when now and then since May 25, 2011, I find myself thinking, “Dana would love this,” even if I am confident that when he crosses my mind in this regard I’m hardly reaching to match projected emotion to absent emotee. When Johan Santana gave us our first no-hitter, there is no chance Dana wouldn’t have loved that. When the Mets rampaged to a National League pennant on the backs of Cespedes, Murphy and all that young pitching, there is no chance Dana wouldn’t have reveled in the result, let alone the process. Kirk Nieuwenhuis? Juan Uribe? This kid Conforto, the fresh prince of Binghamton? Lunky Lucas Duda? Wilmer Flores in tears? Grumpy, soulful Terry Collins? Those were Dana’s kinds of characters.

Dana never got to describe a Harvey Day or deGrom’s unforeseen ascent or the mythology of Thor. He would have been all over those guys. Same for Matz’s debut in front of Grandpa Bert and Bartolo’s world tour of the bases in San Diego and Cabrera’s bat flip that Tugged at our miracle instincts and Pete the powerful Polar Bear. Those were all Dana Brand essays waiting to happen. He’d have ruminated on the ‘F’ that infiltrated LGM. He’d have embraced from a safe social distance Dom Smith when Dom felt all alone on Zoom. He’d have said a proper goodbye to David Wright and Jose Reyes, the last of the Mets still on the Mets from when Dana and I went to games at Shea together.

I mean I think he would have. I can’t say for sure. But I do, because it makes me feel better to have his voice in my head. That goes for great Met moments and blah Met moments. The blah has outweighed the great for much of the past ten years. Dana, I believe, wouldn’t have had a problem coping with that. He understood the Mets weren’t designed to secrete success on a nightly basis. When they were good, they gave us something special. When they weren’t, they gave us themselves, and if it wasn’t always special, it was life. The right man picked the right team to interpret.

I’ll tiptoe a little further out onto the limb of presumptuousness and tell you I think Dana would have gotten Monday night’s 3-2 loss to the visiting Rockies, an evening when the blah (as engineered by Colorado starter Austin Gomber) was in full effect. Wouldn’t have loved it, but he would’ve gotten it. The absurd wave of injuries — learning Conforto and Jeff McNeil will be out far longer than initially suspected, seeing Johneshwy Fargas crash frighteningly into the same wall that took the measure of Albert Almora — would have left him grasping for answers, whether scientific or supernatural. The repositioning of heretofore hapless James McCann at first base and McCann responding to the challenge with a diving stop in the field and a home run at bat would have tickled his karmic fancy. Tomás Nido retrieving a passed ball/wild pitch before it became either because it bounced off the backstop bricks and into his bare hand, allowing the catcher who supplanted McCann to cut down a Rockie runner who’d naturally assumed third base was his would have provided the basis for a morality play. David Peterson’s intermittent struggles would have elicited Dana’s empathy. Francisco Lindor’s continuing struggles would have strained it.

And then, the bottom of the ninth. I can feel Dana next to me at Citi Field in the bottom of the ninth. Never mind that I wasn’t there and he wasn’t there. In my mind, we were both there. Rising and cheering as Brandon Drury pinch-hit and pinch-homered to lead off. Staring at each other with the same wisfhul thoughts in our eyes as Patrick Mazeika (with a beard totally unlike Dana’s, but nevertheless bearded like Dana) delivered a single off the bench. This was where Shea in 2007 and 2008 and Citi from 2009 to earliest 2011 would get loud around us and we’d begin to gameplan the possibilities of a stirring Mets comeback drawn to its giddiest conclusion.

It’s also where it would sink in just as quickly for each of us that, no, they’re doing it to us again. They’re raising our hopes only to inadvertently pinprick them before they rose too high. The Mets weren’t being malevolent, Dana and I would communicate either garrulously or wordlessly. They were just being the Mets. Losing 3-1 entering the ninth. Catching up to 3-2 two batters into the ninth, but with the pinch-homer coming before the pinch-single and the complement of unlikely “pinch me!” heroes used up and the disappointing regulars all who were left, ultimately left to disappoint us.

Unless they didn’t! We’d allow for that possibility, no matter that we deep down knew different…and we didn’t have to plunge that deep to know it. Jonathan Villar strikes out looking (but that’s OK, it’s only one out). Lindor just gets under one but predictably flies out (still, that was a pretty good swing, maybe he’s coming around). McCann, the focal point and lightning rod of our night, is up to push the point clear up to our face. He’s anxious. He’s aware we expect him to be the hero. He has to forget that. Still, the resolution we desire is so close we can taste it. A wild pitch moves Mazeika to second. James the Met so clearly from somewhere else has a chance to become a true New York icon here, to elevate Drury and Mazeika alongside him into legend, to turn around his season and our season, as if our season has ever stopped spinning topsy-turvy since it commenced. If only the count weren’t one-and-two.

Dana and I knew McCann would strike out to end the game. I mean we just knew it. I mean I think I know that we both just knew it.

Technically, I knew it, and I’m otherwise projecting on behalf of the deceased again. I’m presumptuously projecting that ten years since he died Dana Brand and I are still in touch, still talking Mets, still going to Mets games in one another’s company, still telling one another that once Mazeika singled after Drury homered that they’d depleted their reserves of ninth-inning mojo and we knew it, but we kept rooting and kept believing because we’re Mets fans.

I can’t prove it. But I do it anyway. I like having those moments with my late friend.

by Greg Prince on 23 May 2021 5:24 pm Six hits. Five for singles. Only two — the lone double, followed by one of the singles — were grouped in helpful proximity to one another, generating an entire run to cut the scoreboard deficit from gaping to yawning, but either way insurmountable most of the afternoon.

Sit indoors on a sunny Sunday in New York and watch the Mets play indoors on a sunny Sunday in Miami, and that’s what you get. One run produced by a bunch of batters not performing as hitters, few of whom you’d more than barely heard of or thought about weeks ago. Plus a pitcher who seems like a really nice guy, which wouldn’t be the first thing you’d say about him if he seemed like a really good pitcher. Or fielder.

Nobody’s really good among those who don uniforms indicating their affiliation with the New York Mets right now, including the few who’ve been here since the season began. We keep up with them anyway. It’s not hard. They’re only six hits better than us.

I kid. I kid because I love. Of course they could beat me and eight people off the street at a game of baseball. Implicit in that appraisal is the Mets come across as nine people off the street, but baseball is their profession. They’ve got that on we who note their shortcomings for free. They get paid for 5-1 losses to the Marlins. Theirs is not a performance-based compensation system from series to series. Thank goodness, for their sake.

Jordan Yamamoto (who seems like a really nice guy) had a rough second inning, featuring a couple of misplays he had a hand in, and five runs crossed the plate against him. He also has a sore shoulder. All of the above is enough to make a pitcher at least the No. 4 starter on the New York Mets this week. The Marlins let him go. I can see why, if only because between Pablo Lopez on Saturday and Cody Poteet on Sunday, they wouldn’t have room for a righty who can provide three pretty good innings and one sorta unlucky frame in between. Lopez and Poteen pitched very well versus the Mets this weekend. I guess they did.

It was the Mets, after all.

Ouch! Again, I kid. Not really, but the Mets remain in first place, which is the preferred destination for any baseball team in any division, even this one. It is the National League East, after all. I doubt we can count on the prevailing mediocrity of our semi-circuit as a mitigating factor much longer, however. We also can’t point to the daily presence of the “C” team as a Met-igating factor much longer if we choose to take the Mets seriously as a contender in 2021. Games remain scheduled whether or not you come prepared with an optimal assortment of players. It’s not the fault of the journeymen who are populating the roster currently that they were nobody’s first or second choice to be “the Mets” of the moment. They arrived in the organization as depth. They hoped they’d avoid alternate sites and get a call individually, but they didn’t expect to ascend to the majors en masse. I doubt they rallied one another in St. Lucie or Syracuse or wherever they crossed paths and said, “Wouldn’t it be great if all of us among the overlooked, undernoticed and generally dismissed got our chance together?”

But they have. Sometimes, as on Friday, it works. Sometimes, as on Saturday, it almost works. Sometimes it’s Sunday, when Johneshwy Fargas doubles, Wilfredo Tovar singles him in and Yennsy Diaz looks good for an inning…and that’s it, basically. Throw in perennial holdover Robert Gsellman pitching some decent relief and that’s really it. The Mets couldn’t withstand the Marlins defensively and they could barely bother the Marlins offensively and, geez, it’s the Marlins, though at this point who are we to overlook, undernotice or dismiss any opponent?

by Greg Prince on 22 May 2021 9:30 pm Did ya see how the bottom of the eighth between the Mets and Marlins ended on Saturday? Dom Smith made a hellacious dive with two out to corral a grounder from Miguel Rojas, rolled over on his rear end and rid himself of the ball before retrieving his bearings, guiding it to Miguel Castro at first base for the third out of the inning and preserving a tense 1-1 tie in Miami.

It was the best play you were gonna see all day…until one Met defensive out later.

Did ya see how the bottom of the ninth between the Mets and Marlins began on Saturday? Jesus Aguilar lined a ball into the gap between center and right. It would take two kinds of Tommie Agee efforts to reel it in: the kind where Agee dove to rob Paul Blair and the kind where Agee hung on in his webbing to rob Elrod Hendricks. Those were two of the most stupendous catches in World Series history. Amid stakes admittedly a few hundred notches lower, Johneshwy Fargas incorporated the most breathtaking aspects of each to nab from Aguilar a leadoff double and, as Smith did minutes earlier, keep the score knotted at one. Running and diving and gaining proximity to the ball would have been impressive as hell. The ball ticking off the top of Johneshwy’s glove would have been reluctantly understandable. But, nope, Fargas was gonna have his scoop and lick it, too. As so-called ice cream cone catches go, this one melted in your mouth and made your eyes water with joy.

What was it late-’70s mid-tempo duo England Dan and Sean Reid-Foley said in their final hit of the decade? Ah yes, “(G)love is the Answer.” What’s that? Sorry, that was John Ford Coley sharing billing on Billboard with England Dan, later known simply as Dan Seals, who went on to enjoy a successful country music career, highlighted by the crossover hit “Bop”.

Bop. Hit. Neither came up much for the Mets on Saturday. Smith generated an RBI single to drive home bruised pinch-hitter Jose Peraza in the top of the eighth, just when you thought the visitors were afraid to track mud all over home plate, but that was about it for Mets doing anything noteworthy with their bats. To be fair, little bopping or hitting or scoring was happening for the Marlins, either, not with defense like that delivered by Dom and Johneshwy and not with pitching like that delivered by almost every Met arm, particularly st/opener Joey Lucchesi.

If Lucchesi can throw a churve, I can call him a st/opener. Luis Rojas and whoever confers with Luis Rojas to make organizational decisions opted to treat Lucchesi as neither a traditional starter nor a contemporary opener, so let’s say a new category was invented, one in which the pitcher who begins the game throws lights out for four innings — too long to be an opener — yet is removed sans injury because somehow asking a well-rested fella who’s shutting down the opposition on no runs, one hit, no walks and eight K’s to hang around for more than four innings or 43 pitches doesn’t jibe with whatever the plan of the day was.

So goodbye Joey, after the best start (or st/open) of your life, hello Sean, who on most occasions we’d really love to see tonight. The reliable Reid-Foley gave up just one run, and even that was nearly prevented by tremendous defense. Cameron Maybin unleashed a sensational throw from left and Tomás Nido attempted to lay down a timely tag on sliding Brian Anderson in the seventh, but the ball refused to nestle in Nido’s mitt. Only so many Met fielders can cue up for ice cream.

That sac fly from Corey Dickerson and the aforementioned Dom Smith ribbie were the extent of the collective scoring for eight-and-a-half innings and then some. Fargas’s catch, made in support of Drew Smith, seemed to augur we’d get to extra innings, unearned runners on second and another chance at the havoc that won us Friday night’s game. Except Drew drew only one more out of the Marlin lineup. Anderson got annoying again with two out by singling through the right side and Garrett Cooper bopped like a bastard, launching the two-run homer that ended the late-afternoon affair in the Marlins’ favor, 3-1.

Should you see Smith’s fling from the dirt and Fargas’s streak through center within a highlight montage at any point in the future, forget the greater context of the Met loss. They were game-winning plays. They just weren’t enough by themselves to win a game.

by Greg Prince on 22 May 2021 1:30 pm Never mind the cliché about a team beset by injuries resembling a M*A*S*H unit. The Mets of the moment — with 16 players on their injured list — are closer to a M*A*S*H episode. A specific M*A*S*H episode in my mind, the one titled “Carry On, Hawkeye,” from the second season of the series. In it, a flu epidemic sweeps through the 4077th, flooring every surgeon but Hawkeye. Henry can’t operate. Trapper can’t operate. Frank can’t operate (Frank never could operate). Thus, it’s basically up to Hawkeye and Margaret to hold the OR together as wave after wave of wounded are choppered in because war waits for no epidemic.

I thought of this episode Friday night, after Pete Alonso and Tommy Hunter went on the IL, after Jose Peraza got hit with a pitch and had to leave the game, before the Mets put surgical scrubs on Father Mulcahy and Radar O’Reilly because when you’re down doctors, nurses and corpsmen, everybody’s gotta lend a hand. Who, I wondered, was going to be the Mets’ Hawkeye Pierce, the wisecracking healer who almost never loses his composure and almost never loses a patient while all around him are either terribly sick or potentially dying?

Not that I take baseball games seriously as death.

The answer became nobody, even if enough Mets cobbled themselves together to save the day and night. The primary heroes, if we may use such a word for a baseball game, wound up being the approximate Igor, Zale and Rizzo of the roster. No, wait, not even that’s an apt M*A*S*H analogy for the roles played by Jake Hager, Khalil Lee and Johneshwy Fargas in the twelfth inning at Terrible Corporate Name for Marlins Park Friday night. Peraza was a supporting player. Kevin Pillar was a supporting player. If we’d been simply down to the Met supporting player equivalents of Igor, Zale and Rizzo, our chances wouldn’t have looked scant. But our supporting players were confined to their metaphorical beds.

So it was down to the background players — the extras — to come to the forefront and carry the story to its pleasing conclusion. Hager, who had pinch-run in the tenth for unearned runner Tomás Nido, leading off and delivering his very first base hit in the majors and singling Dom Smith, unearned runner in the twelfth, to third. One Wilfredo Tovar out later (to reiterate, Wilfredo Tovar is back from seven years ago), it was Khalil Lee pinch-hitting for Drew Smith. Khali Lee had the distinction of being both the last guy you’d think of to pinch-hit, considering he was 0-for-8 with eight strikeouts in his brief career, and the last guy you had who roughly answered to the description of “hitter” left on the bench. Lee therefore was distinct enough to get the chance to break his ohfer.

And he did, doubling like he’d done it before, driving in Dom to give the Mets a 4-3 lead. After two first major league base hits had been strung together, veritable veteran Johneshwy Fargas, who got his “get him the ball!” moment out of the way four nights and three career hits earlier, tripled to score Hager and Lee and provide whoever would be the next of Luis Rojas’s non-Lucchesi relievers some breathing room. Johneshwy could have used some, too, as he nervily attempted to turn his triple into an inside-the-park home run. What the hell, he’s young, he’s fast…he was out. Nevertheless, the guys in the background of the guys in support roles had put the Mets up, 6-3, in the twelfth inning, as if twelfth innings happen anymore.

Ah, but they do. For all of MLB’s attempts to make everybody go home no more than one inning after regulation (lest they have to pay their cockeyed umpires overtime), this tie squirmed away from the immediate resolution the placement of unearned runners on second base is designed to induce. The game itself got away from the Mets in the seventh, when Luis ordered Marcus Stroman to stop pitching at the first sign of trouble. The Mets were ahead, 3-1, Stroman was basically cruising, but then he made the mistake of walking Brian Anderson on a full count. It was only a mistake in the sense that his manager pulled him at 89 pitches, replacing him with Miguel Castro, who wasn’t necessarily going to give up a two-run homer to Garrett Cooper, but did. There went the 3-1 lead, built aggressively in the first by recognizable cast members Jonathan Villar, Francisco Lindor and Dom Smith, and bolstered in the third by breakout character actor Nido. Stroman was well-positioned to be the Hawkeye of this production, giving us the heroic, nearly deGrommish performance we craved, but his commanding officer dismissed him a tad too soon for the script’s taste.

The Mets, as we note nightly, are amazingly undermanned. The Marlins, we don’t care, operate in a perpetual state of blank space. Do they even have 26 men on their roster? We asked the same last year and they rode their anonymity to the jury-rigged playoffs. Like us, the retrofitted Sugar Kings found guys and put them on the field. Like us, the red-clad opposition didn’t go away. They seemed poised to take one of those aggravating trademark Marlin leads in the eighth when Tim Timmons helped Trevor May walk a pair of batters. Timmons is not some Donnie Stevenson-style figment of South Florida imagination. He was the home plate ump with a strike zone as loopy as the Clevelander night club that used to throb beyond the outfield fence. Somehow May escaped a bases-loaded jam not entirely of his own making. Jeurys Familia put on two baserunners in the ninth as well, but also managed to stretch a velvet rope in front of home plate.

Despite Rob Manfred’s dumbest efforts, the tenth came and went. Same for the eleventh. The scoring column had become as difficult to get into as Studio 54 in its heyday. Whatever purpose there was to slotting a runner on second to start every extra half-inning was coming to naught. Both sides were running out of players. The Marlins in particular essentially ran out of pitchers. Don Mattingly had tried to engineer a bullpen game from the start, because what are the odds you’ll need your bullpen to do a bunch of bullpen things much later? True, the Mets hadn’t played an eleventh inning since Closing Day of 2019, with the dopey new runner-on-second rule having prevented periodic detours to Sudolvania, but eventually you were going to approach the outskirts of a marathon. In 2021, a twelfth inning looms as the 26th mile.

Finally, against Adam Cimber, working a (GASP!!!) second inning of relief, we had Hager come through and Lee come through and Fargas come through. Maybe the Mets would just keep ripping heaters all night long. Then, however, James McCann came up, reminding us that if hitting is contagious, James McCann is fully vaccinated. The catcher who nowadays caddies for Nido grounded out and sent us to the bottom of the twelfth.

Aaron Loup and those pesky Marlins disguised as regal Sugar Kings wouldn’t let the game go gentle into that good night. Jazz Chisolm, which is something your great grandfather warned your grandmother against, singled Miami’s unearned runner Magneuris Sierra to third. Miguel Rojas singled Sierra home to make it 6-4. Chisolm zipped to third. Corey Dickerson then shot a ball up the middle, guaranteeing speedy Jazz would improvise his way across the dish and…and nothing else, somehow. That’s because Lindor, who’s been almost as disappointing as McCann, pivoted sharply to grab Dickerson’s hot grounder; secure a forceout at second; and fire the ball to Smith at first. Smith, who’s quietly been almost as disappointing as Lindor and McCann, did some nice digging in the dirt to prevent catastrophe on the relay. It became a double play that averted disaster.

Smith is a first baseman by trade.

Alonso is the first baseman unless Alonso is hurt.

Alonso is hurt.

Smith started in left field.

Brandon Drury started at first base.

Brandon Drury is on the Mets.

Go figure.

Maybe Lindor was our Hawkeye at the end. That was some sweet shortstop orchestration of a twin-killing to reduce the threat of our own demise. And you know that buried somewhere beneath his infinitesimal production is a megastar leader struggling to emerge. Francisco actually embraced Dom at the mound while the infield gathered for the ritual shooing away of Aaron Loup while Rojas summoned Jacob Barnes. That is not the sign of someone stuck in own head until he starts hitting for real. Lindor may not have earned his Captain’s bars in New York yet, but he’s still conducting himself as chief surgeon of the infield. As with McCann when stationed behind the plate and Smith when transferred temporarily to first, Lindor’s ability to contribute through defense shouldn’t be overlooked just because of his glaring lack of offense.

Lindor did get two hits Friday night, or as many as Fargas did. Lindor did make a keen extra-inning, game-saving play, or as many as Cameron Maybin had. In the eleventh, Cimber, Mattingly’s tenth pitcher, lined a ball to right field with runners on second and third. It was May 21, 2021, the sixteenth anniversary of Dae-Sung Koo’s double and subsequent trip around the bases off Randy Johnson. Don’t doubt what can happen when relief pitchers swing a bat on May 21. Maybin (0-for-5) snagged Cimber’s liner and kept us going until we could stagger to the twelfth and revel in the exploits of Hager, Lee and Fargas in the top of the inning and Lindor and Smith in the bottom of the inning. Oh, Barnes, too. Jacob flied out Adam Duvall to say goodbye, farewell and amen to the Marlins in a mere four hours and thirty-eight minutes (or the approximate running time of the egregiously padded M*A*S*H finale “Goodbye, Farewell and Amen”).

Commendations all around. Drinks in the swamp are on Lindor.

by Greg Prince on 20 May 2021 11:15 am “Please cover your left eye and tell me what you saw Wednesday night from Atlanta.”

“David Peterson carrying a no-hitter into the fifth inning, showing the promise that gets us so excited about him … defensive prodigy Khalil Lee making his second sensational catch in two nights … Cameron Maybin using his wheels and wits to race from home to third without a base hit to set up the potential go-ahead run … James McCann’s bullet of a throw nailing Dansby Swanson and snuffing out the biggest threat within a burgeoning Braves rally … a huge hit from one of the Mets’ three catchers, which strikes me as the ideal number for a club to carry … Jacob Barnes courageously rescuing the Mets in relief .. .Mets pitchers continuing to neutralize the ever dangerous Ronald Acuña, Jr. … and the plucky Mets going to the ninth with every chance to sweep a series despite having almost no business winning this game. God, I can’t get enough of this team!”

“All right, now please cover your right eye and tell me what you saw Wednesday night from Atlanta.”

“David Peterson imploding in the fifth inning, showing the limitations that gets us so frustrated with him … offensive naïf Khalil Lee doing literally nothing but striking out … Cameron Maybin having no bat whatsoever, either … James McCann not so much as lifting a lousy sacrifice fly that would have scored Maybin after Maybin converted a strikeout into first base via wild pitch, second base via a steal and third base via another wild pitch … Tomás Nido sitting on the bench after he delivered his big pinch-hit earlier instead of having been in the game the whole time, which seemed ridiculous considering how hot he’s been and how useless McCann has been, so how about managing your three catchers properly? … Jacob Barnes giving up the walkoff homer in a tie game on the first pitch of the ninth after somehow wriggling out of the mess Aaron Loup left him in the eighth … Ronald Acuña, Jr., breaking his serieslong schneid by torching Barnes to beat the Mets, 5-4 … and the stupid Mets blowing multiple chances to win a game they had absolutely no business losing. God, I’ve had enough of this team!”

“OK, I’d say your vision is 2021.”

“Huh? I’ve heard of 20/20, but not 20/21.”

“Your vision is a condition specific to Mets fans this season. It’s ‘2021 Mets’.”

“Is it rare?”

“Actually, there seems to be an epidemic of it among certain segments of the baseball-watching population.”

“Is it serious?”

“I’d call it seasonal. I see a variant of it most years.”

“How does a person know if he has it?”

“The defining symptom of ‘2021 Mets’ is an unreasonable view that these particular Mets, despite all of their injuries and the dizzying turnover of their roster, shouldn’t lose any game they seem to have a reasonable chance of winning.”

“What do you mean ‘unreasonable’? They were ahead, 1-0, on Villar’s homer! They were ahead, 4-3, on Peraza’s double and Nido’s two-ribbie single! They had Maybin on third in a tie game and all they needed was a frigging fly ball! Luis had outsmarted Snitker to get Morton out of the game! They had Acuña contained! Lee already deserves the Gold Glove! Dom played first like a real first baseman! And Peterson had a no-hitter going before anybody gave a second thought to Corey Kluber!”

“You didn’t let me finish my diagnosis. When your vision is ‘2021 Mets,’ it is unreasonable to see the Mets as a team that’s going to win every game they’re in, but it won’t seem unreasonable as long as the Mets remain doggedly competitive.”

“They’re a major league team! They’re supposed to compete!”

“Try these lenses. Tell me what you see.”

“I see … I see minor leaguers and other teams’ castoffs. Maybin really looks cooked. Lee looks totally overmatched at the plate. Loup looks like he’s the one who should’ve retired instead of Blevins. Peterson looks more inexperienced than I think of him as. Through these lenses, I see a team that does nothing but let me down.”

“What don’t you see?”

“Um, no Conforto. No Nimmo. No McNeil. Wow, now, I don’t even see Alonso. Jesus, they don’t look like they can possibly compete!”

“Uh-huh. Now try these lenses.”

“Hey, that’s much better!”

“What do you see?”

“I see … I see bench guys coming through and callups surprising me occasionally and pretty clutch defense and relievers providing relief despite being used so much and, hey, Maybin’s speed really stands out. Through these lenses, I see a team that’s managed to withstand crazy adversity and remain in first place.”

“Different lenses, different visions.”

“What can you give me so I can see the 2021 Mets for what they really are?”

“I’m writing you a prescription for 125 more games. Take them one at a time.”

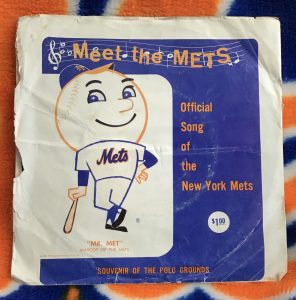

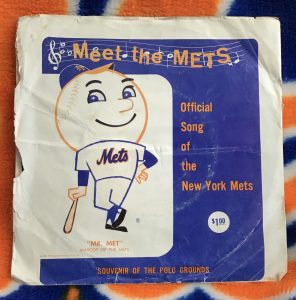

by Greg Prince on 19 May 2021 11:44 am (Presented with eternal affection for the timeless creation of Ruth Roberts and Bill Katz)

Meet this Met

Meet that Met

Every day we meet more Mets

There’s Tommy Hunter

And his first hit

There’s Khalil Lee

Who can field quite a bit

Johneshwy Fargas

Roaming in center

Starting relievers

So new arms must enter

Toe!

Más!

Knee!

Doe!

Suddenly’s a power bat

His clutch home run

Just beat the Braves

Get a load of that!

Oh Pillar’s somehow jokin’

Though his nose is sadly broken

Shallow in depth —

We cheer these Mets!

Oh Villar in the lineup

Means a dinger’s comin’ right up

Long as they win —

We’ll dig these Mets!

Wilfredo Tovar

From Twenty Fourteen

Hurry south

If you please

Otherwise

We’ll have no ballclub

For lack

Of warm bodies

Give us some help!

Give us a hand!

We might be signing players

From the stand!

Come on and…

Meet these Mets

First-place Mets

Cameron Maybin’s

Next a Met

The Fish who caught

The last out at Shea

Whom I’ve resented

Since that dreary day

Because the Mets will take

Whoever can breathe

Save Trev Hildenberger —

They asked him to leave

Thiiiis Met…

Thaaaat Met…

Keepin’ track’s a constant choooore…

When Mets go down with injuries

Don’t fret —

There’s more!

Can’t beat the original, but that doesn’t mean we can’t try to keep up with the times.

by Greg Prince on 18 May 2021 12:23 pm Kvetching about the mounting mountain of injuries to Met players is darkly amusing until somebody gets hurt.

I mean really hurt.

Monday night in Atlanta, Kevin Pillar was smacked in the face by a rising 95 MPH fastball thrown with no purpose other than getting him out by the Braves’ Jacob Webb. It happened literally in a matter of seconds.

One second, Pillar was standing in at the plate, behind on a one-and-two count, concentrating on how best to drive in his teammates who have loaded the bases with two out in the top of the seventh inning. Tomás Nido had doubled to lead off, James McCann pinch-doubled him in to break a scoreless tie, and a pair of walks (unintentional to Francisco Lindor, intentional to Dom Smith) followed, intertwined with a pair of outs. This was what we consider a game situation. It’s what we focus on. It’s what the batter and the pitcher focus on.

The next second, the batter is on the ground, blood gushing from his nose, and it’s all we can focus on, if we can bear to look. It’s a hit by pitch and a run batted in, yet the scorekeeping is irrelevant. It’s a person down in the dirt bleeding badly, requiring medical attention and in no condition to rise and do something as presumably effortless as jog to first base.

Watching on television, also in about a second, your priorities switch from let’s get at least another run here, it’s only 1-0, we need all the help we can get, c’mon Pillar to yikes! or interjections to that effect. You just want the blood to stop and the person on the ground to get up and, if you can find it in your heart to worry about the mental well-being of the pitcher whose fastball got away, the person on the mound to grab a seat and get ahold of himself, whatever form that takes.

Webb throws hard. Everybody throws hard. As Tom Verducci wrote in Sports Illustrated mere hours before Webb hit Pillar, pitchers are hitting batters at all-time rates, with almost one HBP per game. Among fastballers, the high four-seam variety like the one Webb threw is particularly in vogue as “the antidote to the launch angle generation.” Only minutes before the incident that left Ron Darling practically speechless, our prized pitching analyst was speaking on SNY about velocity’s adverse effects on offense — so many more strikeouts, so much less scoring. The same game whose pace so often seems glacial sometimes moves too quickly for its participants’ own good.

At Truist Park, it all led to a brutal scene that felt interminable during the minutes it unfolded. Nevertheless, Pillar indeed got up. Still bleeding, but standing and walking toward the dugout and clubhouse. That was a bigger victory than the 3-1 win the Mets eventually secured. Webb went to his bench, clearly shaken. No wonder. The grounds crew had to wipe away blood from the batter’s box.

But the game went on. The game always goes on. After a respectful pause, McCann stepped on the plate, representing the run Pillar drove home. Khalil Lee went to first and made his major league debut as a pinch-runner. Sean Newcomb came in to pitch in relief of Webb. Jonathan Villar grounded out to end the inning. On to the bottom of the seventh and so forth.

Pillar’s injury was the second and most severe of the evening. Earlier, Taijuan Walker was cruising for a couple of innings until he started showing signs of discomfort. It didn’t affect the score (3 IP, 0 R), but he had to leave with tightness on his left side. Everybody on the Mets was getting tight on one side of his anatomy or another. The day before, it was the hamstrings of Jeff McNeil and Michael Conforto. That game went on. Patrick Mazeika and Jake Hager took their place in the lineup Sunday. Lee and Johneshwy Fargas took their place on the roster Monday.

Folks like us counted up the injuries and kinda rolled our eyes at the misfortune we perceived as our own We wish our Metsies well always, and we want them back soonest, but unless one of our guys gets injured in plain view and the agony he seems to be experiencing is clearly unavoidable, the overall effect is abstract.

Will ya look at this injured list?

Can ya believe how many Mets we’re missing?

Geez, this is really putting a crimp in our season!

Yeah, ours and theirs, I think we understand conceptually, but in the abstract it’s inevitably out of sight, out of mind, other than “when is he gonna come back already?” The players know this on some level. My guess is they don’t exactly mind, at least not in the short-term. When Albert Almora, Jr., ran into a wall in pursuit of a ball last week, he was sure to tweet shortly thereafter that he’d made the catch (before the wall took it away). The game went on and Almora preferred to be thought of as a contributor rather than a victim. Monday night, Pillar’s first words to us, via Twitter, were that he was fine and, oh by the way, he drove in what turned out to be the winning run. The game went on and Pillar prefer red we remember that he genuinely took one for the team.

https://twitter.com/kpillar4/status/1394494840851812352

We want results. They want results. They need to recover from whatever’s happened to them so they can continue to yield results and extend their careers and, I suppose, get paid at a major league rate. Which is fine with us. We’re fans. We want results.

After Pillar went down, Noah Syndergaard, one of the many injured Mets — and definitely in the “out of sight” category since March of 2020 — elbowed us extra hard to be aware of what a fraught endeavor baseball can be for those whose bodies are square in the middle of it. You have the high, middle and low heaters “off faces, hands, wrists, everywhere else daily,” Thor tweeted, to say nothing of blown-out “UCLs, ACLs, shoulders, knees, hamstrings,” all endured across “162 games [over] 180+ days, plus Spring Training, and HOPEFULLY an extra month of playoffs,” only for a player who’s hurt to hear “HE’S ALWAYS HURT!”

I can’t argue with Syndergaard’s assessment. And I can’t necessarily promise that after the shock of seeing Pillar in pain wears off — he’s been diagnosed as having suffered “multiple nasal fractures” — my first instinct still won’t be to think first “when is this guy coming back?” rather than “is this guy fully OK?”

And the game goes on. It did after Walker departed (he said he doesn’t think he’ll have to miss time) and it did after Sean Reid-Foley took his place for another three scoreless innings. It did in the eighth, too, when Fargas flared a run-scoring double to right to provide the bullpen breathing room and make his maiden major league voyage one that would look lovely in the box score. Same as the combined three-hitter achieved by Walker, Reid-Foley, Jeurys Familia, Trevor May and Edwin Diaz. Same as the three hits collected by Nido. Same as that go-ahead RBI credited to Pillar.

Not that gazing at the box score was a person’s primary priority after Kevin Pillar went down, but as noted, the game goes on. Sometimes we are reminded it is just a game.

by Greg Prince on 17 May 2021 11:50 am The most delightful aspect of the 2021 Mets to date that hasn’t involved Jacob deGrom pitching and hitting has been the emergence of the self-anointed Bench Mob, the aggregation of heretofore part-timers who’ve produced plentifully when called on, which has also plentifully. Riding to our injury-riddled rescue in the grand tradition of Bambi’s Bandits, Hondo’s Commandoes and Randolph’s Randos have been brothers from an off-brand rhyming dictionary Jonathan Villar and Kevin Pillar; Jose Peraza, who almost rhymes with Mike Piazza; perennial backup catcher Tomás Nido; and backup to the backup catcher Patrick Mazeika, who has yet to catch anything but the recurring congratulations of grateful teammates. That they’ve filled in admirably as they have with their sticks, mitts and moxie has made them collectively embraceable. That they have a nickname for themselves makes them collectively adorable.

That they have to play as much as they do is probably a problem.

We get goosed when we see Pillar coming alive in center, Villar working wonders at third, Peraza taking care of second, Nido putting down fingers behind the plate with strikes to follow and Mazeika being Mazeika, which is definitely a thing. Throw in a hearty if virtual pat on the back for Jake Hager, who’s suddenly a two-game major league veteran after ten years of beating the bushes. It’s not an OT goal in the first game of the first round of Stanley Cup playoffs (Go Isles!) or Kevin Durant completing an Endy Chavez-style sequence of events with an off-the-glass dunk you can’t believe you just witnessed (Go Nets!), but it’s something that rewards your constant fandom. Your bench guys forging an identity as they contribute defensively and offensively to victory or at least viability is part of what makes a baseball season worth living.

Seeing too much of them is what makes a baseball fan nervous. Because once the Bench Mob drifts from its natural habitat, that bench they kept heated grows cold, icy and empty.

On Sunday from St. Pete, we saw the bench of the Mets stripped nearly to its splinters. Almost everybody we think of as a reserve had a reservation in the field. Those who weren’t shown to their positions to start the game were ushered into the lineup moments after pitches began being served. Hager was upgraded from just happy to be here to right fielder. Mazeika, late-innings secret weapon deluxe, was now the leadoff hitter. Good for them. No, great for them, individually. Nobody raised a kid with ballplaying aspirations to set his sights on sitting and watching.

But somebody on a roster of 26 does need to sit and watch, and by the bottom of the first at Tropicana Field, Nido, who’s sat and watched more than his share of games from the bench since September of 2017, was the only Met available to fill that crucial for the role for the next eight innings. Hager was in right because Michael Conforto couldn’t be, having had his right hamstring tighten as he ran to first in the top of the inning. This was two batters after Jeff McNeil, who left a game earlier in the week due to “body cramps,” had his left hamstring tighten after beating out an infield hit. Together, Conforto and McNeil couldn’t have competed effectively in a three-legged race.

And the Mets, it turned out, couldn’t compete effectively against the Rays. The regulars whose hammies are presumed sound — James McCann, Pete Alonso, Francisco Lindor, Dom Smith — didn’t hit at all. Neither did the Bench Mobsters who have been upgraded to semi-regular status. The only Met who joined McNeil in the hit column was his replacement, Mazeika. McNeil is usually a second baseman and we hear Mazeika is a catcher, so what kind of versatility was at work?

The devil’s own — the designated hitter. Luis Rojas thought he’d ease McNeil, whose recent crampiness and sundry achiness kept him sidelined Saturday, back into action by using him as a DH, same as he’d done Friday. Until this series and its concomitant sweep, the DH had reverted to bad Met dream status, as if 2020 hadn’t really happened. “It was so weird. There were cardboard cutouts in the stands, we never played the Central or West, Rick Porcello and Michael Wacha constituted two-fifths of the rotation, and they wouldn’t let deGrom come to bat.”

Sunday the nightmare returned for one of its sadly scheduled Interleague cameos. The Mets have been coerced into using a DH in American League parks since 1997, lacking the intestinal fortitude to withstand the peer pressure of their hosts deploying an extra hitter. The Rays always have a DH. The Mets kinda had to, too, so they used McNeil. They got a base hit and a tight hamstring for their troubles. Once Jeff gingerly stepped away, Patrick stepped into his one-dimensional shoes. He made the best of it, swatting a bases-empty home run for his first big league hit of any kind. Being Patrick Mazeika, it was his fourth RBI because, as we’ve learned, Patrick Mazeika doesn’t need any stinking base hits in order to drive runs in.

It was mentioned during the telecast that Mazeika became the first Met to notch a four-bagger for his initial safety since current pitching coach and erstwhile Matt Harvey staffmate Jeremy Hefner did it nine years ago. I was at Citi Field for Hefner’s homer. I practically dropped my fork in amazement and appreciation (there was a buffet). There’s nothing on Mrs. Payson’s green earth as invigorating as a pitcher homering. For Mazeika, I applauded, too, even if he prospered powerfully in a role I rue. Not counting 2020’s assault on National League sensibilities, 22 Mets have hit 43 home runs while serving as designated hitters. Among that crew, nobody else used a partial vacation day to register his first major league hit with a DH HR, though Chris Carter did connect for his first career dinger that way at OP@CY in 2010. Chris, in fact, blasted two Camden Yards goners while a designated sop to AL nonsense in that Mets-Orioles series, but the Animal (speaking of endearing nicknames) already had a dozen MLB hits on his ledger by then.

Newest newcomer Hager didn’t homer, but he did record an assist from right field as Manuel Margot got greedy in the eighth after singling home the Rays’ fifth run. Not satisfied with merely affixing window dressing to the ultimate result, Margot — who has never made an out against the Mets otherwise — tried to stretch his latest hit into a double. Hager’s throw and Lindor’s tag were ruled to have beaten him to the bag. Replay was inconclusive, but we’ll take it. Same for Mazeika’s home run in a role a lifetime of lineup ebb and flow has conditioned us to eschew (yet one we’ll probably get omnipresent evil of the universal DH).

We’ve pretty much run out of Met highlights from the Spring Training lineup Rojas wound up fielding down the road from good old Al Lang. Marcus Stroman’s sinker wasn’t working, three Rays homers flew toward Tampa, and a 5-1 defeat was all she wrote. With the Mets landing in Atlanta to attempt to defend their shaky first-place perch, we’re left to ponder a) the hamstrings of Conforto and McNeil and b) who is going to sit up and be counted behind those who’ve mobbed up the batting order on a daily basis. As if we don’t have enough injuries to ponder. For those who’ve lost count, the Mets injured list already encompasses:

• starting center fielder Brandon Nimmo;

• starting third baseman J.D. Davis;

• charter Bench Mobster Albert Almora, Jr., who donated his face to a wall against Baltimore last week;

• handiest among Met handymen (yet he’s missed all the Bench Mob spotlight) Luis Guillorme;

• sunshine of our life deGrom;

• heretofore crucial reliever Seth Lugo;

• markedly less crucial reliever (but we wish him no discomfort as he takes all the time he needs to heal) Dellin Betances;

• starting pitcher Noah Syndergaard, who we weren’t counting on right away considering he’s been out since what seems like the Obama administration;

• starting pitcher Carlos Carrasco, who we were counting on right away but got hurt in Spring Training;

• and spare outfielder Jose Martinez, who was also hurt in Spring Training and we weren’t really counting on, yet we can’t spare an outfielder at the moment, thus a Jose Martinez shoutout feels merited.

McNeil and Conforto are in MRI limbo. Dr. Rojas’s initial diagnosis was “hamstring issues are no joke,” and indeed, nobody’s as much tittering. Elsewhere in the land of the medical report, Lugo’s supposed to test his repaired right arm in Syracuse, where Davis will do the same with his bruised left hand. Nimmo had to halt his comeback trail because his finger wasn’t ready to point toward the sky without pain. DeGrom could be back as soon as Friday, which would either be not soon enough…or too soon if you maintain a creeping sense of doom regarding rushing the best pitcher in the world to the mound, even if Jake can’t go about being the best pitcher in the world when not in the mound. DeGrom not pitching leaves a void. DeGrom pitching immediately after a minimal IL stint raises anxieties. Can he be activated just to pinch-hit and maybe play short?

Playing short, alas, is what the Mets are doing too much. The Bench Mob has been splendid. The injured mob threatens to overwhelm them. What is an organization with more players on the IL than run the past two days to do? DFA a few of the 137 marginal relievers absorbing space on the 40-man roster? Scan the waiver wires for untapped potential? Call Syracuse information and ask the operator to check for listings under “utility”? These weren’t questions we thought we’d be asking. We thought we had depth by the mobful, yet it appears our depth is going to need even more depth, lest our season be prematurely deep-sixed.

UPDATE: McNeil and Conforto are both headed for the IL. The Mets will be bringing back Khalil Lee and promoting Johneshwy Fargas.

by Greg Prince on 15 May 2021 7:53 pm Less than 24 hours after the Mets lost to the Rays by one run on Friday night, the Mets were losing by one run to the Rays on Saturday afternoon, yet whereas Friday’s defeat grated deeply as a one-run loss will, the one-run deficit the Mets were alternately trying to overcome and maintain Saturday didn’t feel anything like a one-run deficit.

Which is why it burgeoning in a veritable blink into a seven-run blowout felt quite natural.

Unnatural, however, is “the bullpen game,” a clever concept until it crumbles, at which point it becomes an impediment to competing effectively…unless you’re the Rays, who brought this pox on baseball’s house in the first place. That you can’t beat the Rays with their own cudgel seemed karmically obvious all along.

If the Mets had five starters handy, one supposes they would be using five starters. At the moment, with Jacob deGrom calmly and quietly healing from whatever’s not wrong with him (please, please, please), they’re down to three. With deGrom, they have four. Whenever mythic Thor character Noah Syndergaard and mythical erstwhile Clevelander Carlos Carrasco materialize, the Mets will have a surplus.

That day is not close. So we have a day with a barrage of relief pitchers and a hope that they live up to their name, especially relieving the residual stress from Friday.

Not so much on Saturday. “The opener” — all this stuff belongs in quotes — Drew Smith raised the curtain adequately, giving up only one run in two innings. “The bulk guy” Joey Lucchesi, however, wasn’t able to ride his signature churve to a successful outing. On one hand, that’s bad, because we needed quality or at least bulk from Lucchesi. On the other hand, I don’t ever want to hear the word “churve” again, so the sooner Lucchesi is chased from the mound, the sooner “churve” hits the showers. Nothing against the pitcher. Nothing against the pitch, even. Everything against a word that sets my nerves on edge every instant it’s spoken. “Churve” sounds like a preppie pronunciation for what is commonly mixed with sour cream atop a baked potato.

Muffy, whatever have you done with Joey’s churve?

The combination changeup and curve NEEDS A BETTER NAME. And it needs to be thrown better. Thus ends the analytical portion of this program.

I wasn’t that crazy about the rest of the bullpen from the bullpen game and whatever they rest of the bullpen threw. When it was 6-5, with Tommy Hunter (the only player whose identity suggests he should regularly wear the otherwise hideous Armed Forces Day camo cap) squirming out of jams and the Mets’ dormant power bats — specifically those belonging to bench mobster Jose Peraza, homecoming king Pete Alonso and celery stalk-coiffed Francisco Lindor — briefly stirring from their naps, it was close, but it never felt like a one-run game. The defending American League champions have had us right where they wanted us ever since David Peterson gave way a little too late the branch of the Mets bullpen that sees consistent deployment. On Friday night, I couldn’t in all good conscience fume at Trevor May, Miguel Castro or Aaron Loup. I could fume at the loss they left their fingerprints all over, but that game seemed destined to get away the second Gary Cohen told us Luis Rojas had nobody warming to start the eighth. We were up, 2-0, and it felt like we were playing catchup. The individuals within the bullpen didn’t feel culpable. Or bulpable.

“Bulpable” may not be recognized as a word by spellcheck, but neither is “churve”.

Saturday I wasn’t in the mood to cut the bullpen slack in light of it having been dubbed their game. Luis, presumably at the front office braintrust’s behest, emptied out the less depended-upon section of the relief corps and kept it warm all afternoon. This is why you don’t make the entire pitching staff out of the bullpen. Hunter may have blended into the offensive onslaught Tampa Bay was unleashing, but Sean Reid-Foley, Jacob Barnes and former All-Star closer Jeurys Familia couldn’t camouflage themselves from what the Rays were firing at them and therefore became sitting ducks. Mets fielders also failed to mount an adequate defense against what became a 15-hit attack, though the Tropicana Field carpet and positioning by shift certainly didn’t help Lindor on two balls that looked grabbable or smotherable or something that shouldn’t have gotten by him in the bottom of the eighth.

Then again, lose by one, lose by seven, what’s the difference? The difference is six runs, for those of you scoring at home, which is what the Rays did a lot.

With two out in the top of the ninth and the Mets trailing, 12-5, former Rays farmhand Jake Hager pinch-hit. Having been a “farmhand” for a team that plays in a facility named for a leading brand of orange juice suggests that Jake, 28, patiently worked his way through the groves of Central Florida, but he was mostly playing baseball this last decade. The first-round draft pick from 2011 carries a metaphorical suitcase that includes stickers from four different Triple-A stops, Syracuse the most recent of them. There’s been a lot of close, but no cigar on Jake’s journey. No OJ, either, not until Saturday when Hager replaced Khalil Lee on the Mets roster and was instructed to bat for Kevin Pillar. Khalil was here for a couple of days with no opportunity to play, but Lee is only 22. Give Jake a break, kid.

It was the first major league at-bat of Hager’s ten-year professional career and the first time any Met player wore 86, a pair of digits — like the city of St. Petersburg itself — that contains some Amazin’ championship cachet. New No. 86 Jake Hager finally getting this kind of chance was a reason to stay tuned, a reason to remain engaged, a reason to feel good.

Hager proceeded to fly out, thus ending the positive evocation portion of our program.

by Jason Fry on 15 May 2021 2:08 am One of my more searing minor Mets memories — to use a very Mets-fan turn of phrase — is from May 3, 1996.

That was Paul Wilson‘s sixth career start, against the Cubs at Wrigley Field. Wilson, one-third of the vaunted Generation K, hadn’t exactly streaked out of the gate: As the second month of his big-league career began, he was 1-1 with a 6.92 ERA. Yet as Mets fans we knew — or at least devoutly hoped, with an intensity that felt like knowing — that he was far better than that. He’d been unlucky and hurt by some bad bullpen work, but he’d also shown flashes of being the shove-you-around power pitcher prophesied by so many breathless scouting reports.

Against the Cubs on May 3, Wilson took a 2-1 lead into the ninth, having struck out eight and scattered three hits. After a leadoff bunt single, Wilson struck out Brian McRae and Ryne Sandberg and stood an out away from his first career complete game — and, I was certain, the first steps along his path to glory.

I was at my old high school that day for some reason; I vaguely recall it had something to do with advice for the kids who ran the student newspaper, which now seems like a terrible thing to let me offer. That was before cellphones, but I had a Motorola Sports Trax beeper that kept me abreast of Mets games through little LCD runners, changing numerals and bleeps and bloops. I waited and waited and then recoiled in disbelief as my little beeper emitted a disconsolate bloop and then a dreadful, from out-of-nowhere verdict.

CHC 4 NYM 2 (F).

The details had to wait, but that made them no less dreadful. Despite having John Franco in the pen, the Mets had left Wilson in north of 100 pitches, opted to walk the dangerous Mark Grace, and pitched to Sammy Sosa — who Wilson had retired three times, twice via strikeouts. Wilson’s first pitch to Sosa was his 107th, a slider that hung in the strike zone. Sosa hit it onto Waveland Avenue. From a complete-game victory to a sour defeat in a few lousy seconds.

(If you want more there’s video, but why do you want more?)

Somehow that was a quarter-century ago. I’ve now watched dozens and probably hundreds of sequels to that moment of decision: young Mets pitcher, glittering performance, a lot of pitches thrown, a tight game. What do you do? Take him out with the proverbial good taste in his mouth and trust the bullpen to handle the rest? I’ve seen that fail more often than I’d like to recall. Leave him to persevere and finish matters himself? I’ve seen that one go badly awry too. The only lesson I’ve ever drawn is the right course of action is obvious afterwards but not so much in the moment.

So, anyway: The Mets played the Rays in St. Petersburg Friday night, with both teams wearing camo caps and stirrups that looked like puttees — a new wrinkle in baseball military salutes though not necessarily a sartorially wise one. David Peterson was terrific. So was Tyler Glasnow. They dueled through a taut, interesting little game in which nothing much happened except for a couple of brief flurries in which everything happened all at once.

Glasnow looks like an action figure come to life: six-foot-eight, barbarian-hero hair, blandly handsome face. And he’s got superhero stuff: a fastball that can hit 100 and a curve best described as deadly. His arsenal would have been unimaginable when I was a kid, the kind of thing that would make you accuse your little brother of messing with the videogame settings, but it elicits little notice today, which is just one of the many extraordinary things about the modern game we take for granted. For Glasnow, the flurry of unwelcome activity came in the fifth: After retiring the first 14 Mets, he gave up an infield single to Kevin Pillar and a homer to Jonathan Villar. Villar was the only one involved who’d thought his ball was going out, and posed beneath its arc in admiration; he was also correct. Just like that, Glasnow’s excellent day had seemingly crumbled.

Peterson’s flurry came in the eighth, with a 2-0 lead and a pitch count in the 80s — up there but not necessarily alarming. With no one out and the Mets’ bullpen quiet, he threw a fastball to Mike Zunino that caught too much of the plate and crashed into the upper deck, which was fortunate because otherwise it might have broken a car window in Orlando. The next hitter, Kevin Padlo, doubled for his first big-league hit, a milestone I can normally celebrate but that left me muttering and swearing given the circumstances. Peterson got Brett Phillips on a strikeout and yielded the mound to Trevor May, who recorded a lineout on a nifty grab by Villar but then surrendered a game-tying double to Manuel Margot, who somehow has a career average of 1.100 against the Mets with 526 RBIs and whom I do not wish to discuss further in this post or preferably ever.

Should Luis Rojas have let Peterson start the eighth? Should he at least have had someone hot so Peterson didn’t face anyone after Zunino? Should he have done what he did and then joined us to shake our fists and moan at the heavens? Beats me. I didn’t know in the moment, having seen every strategy go wrong at one juncture or another, so I won’t pretend to know now.

What I do know is that the rest of the game felt like a depressing variant of Clue — some Ray was going to kill us and I wasn’t particularly motivated to find out exactly who and in what room and with which implement.

Still, the coup de grace was creatively cruel. With one out in the ninth and the bases loaded, Aaron Loup was brought in to face pinch-hitter Joey Wendle. In that situation, so many things can be your undoing that if you lose you shrug and say, Well, of course. But Loup struck out Wendle looking. One more lousy out and the Mets would have a free runner on second and various ridiculousness would ensue, possibly involving victory.

Phillips was up, and he served Loup’s first pitch over the infield. It didn’t land on Waveland Avenue or anything, but it went far enough and now I was annoyed where 30 seconds earlier I would have shrugged.

That’s another scenario I’ve lived through before, and will live through again. Baseball will kill you if you let it; my only advice is not to let it.

|

|