The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 30 September 2020 12:37 am Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

When I was a teenager, a lot of people assumed I’d be a sportswriter. Which made a lot of sense: I loved baseball and writing, so why not put the two together? But I was pretty sure I didn’t want to do that.

For one thing, I knew enough about sportswriting to understand that you couldn’t be in the press box and be a fan, and I didn’t want to stop being a fan. There were other ways to write, but you either were a Mets fan or you weren’t, and being a Mets fan was important to me.

For another thing, I’d read enough scoop-in-the-locker-room stories to learn that daily exposure to millionaire athletes was probably not going to lead to my liking them more, and almost certainly was going to lead to my liking them less — in some cases, a lot less. I didn’t want to know that my team’s veteran first baseman was a surly asshole, or that the ace of its starting rotation was a leering, juvenile dipshit. I was already beginning to sense that there was a huge gulf between my life and that of baseball players. In the vast majority of cases, we’d have nothing whatsoever in common, and the professional relationships I’d have to forge would only widen that gulf. Their paychecks would come with two or three extra zeroes, and there’d be many times — a bad game, a clubhouse controversy, a messy collision between on-field and off-field worlds — when they’d see me as an adversary.

Why in the world would I trade being a Mets fan for that?

Then there was a third thing, one I was nowhere close to understanding then and am still sorting out now that I’m north of 50. I didn’t want to cross that gulf. I had no particular interest in meeting ballplayers or knowing them as people.

Is that snobbery? I’m sure there’s more of that at work than I’d like to admit, some jocks vs. nerds residue that can never be cleaned out of the gears. But I don’t think it’s the real reason. For one thing, I don’t think of ballplayers as dumb — I’m floored by their ability to recall long-ago at-bats, their radar for picking up patterns and tells, and the superhuman discipline and focus possessed by even the most marginal big-leaguer. They outclass me as thoroughly in those respects as they do in hand-eye coordination and fast-twitch musculature, and those mental weapons are as important to their success as their physical gifts.

The gulf is more about the fact that the players determine the outcome of events on the field that mean everything to me, and I can have zero effect on those outcomes, no matter how hard I cheer or how eloquently I write or how diligently I follow whatever whammy seems to be working at the moment. I am not part of a shared endeavor, no matter how much I’d like to think otherwise and how many times I refer to the Mets as “we.” The players are doing a job for which they are uniquely suited, by genetics and lifelong training; I am living and dying on the outcome of their job performance. They may as well be superheroes, both in terms of ability and in terms of being participants in a drama I can only observe.

There’s no bridge long enough or strong enough to cross that gulf, and knowing ballplayers as people has always struck me as a doomed attempt to rivet one together. Still, I’ve done more metalwork than I might have guessed: In one of life’s ironies, technology and friendship and chance conspired to produce this blog and make me at least a quasi-sportswriter after all. During the Mets’ Prague Spring of outreach to bloggers, I found myself meeting players in occasional media-room and dugout sessions. It was fascinating hearing R.A. Dickey break down his approach to pitching, it was fun asking Dwight Gooden what he might have accomplished if he’d been allowed to hit left-handed, and it was a treat to interview Ron Darling at length for a Queens Baseball Convention panel. But those brief forays were about as far down that road as I wanted to go, and did nothing to make me think I’d chosen the wrong path years earlier.

All of which has brought me, at last, to Lenny Dykstra.

I was 16 when Dykstra made his debut for the Mets in 1985, and I loved him instantly. He was pint-sized in a game of giants, and he played baseball with ravenous joy, gorging on it like a kid in that two-hour grace period from nutrition and house rules that ends Halloween Night. Whether at the plate, on the basepaths or in the field, he was an agent of gleeful chaos, a player who seemed able to will himself to success.

And it didn’t hurt that he was ferocious bordering on crazy. I loved that the Mets of the mid-80s seemed more like a mob of banditti than a baseball team. I gloried in their bad behavior: the arrests in Houston, the plane they trashed so thoroughly that it’s a minor miracle it stayed airborne, their serial fistfights and dust-ups, and the fact that other teams and other fans hated them. They were brash and loud and crass and backed up every obnoxious thing they said. When you’re a teenager, that’s pretty appealing.

Dykstra fit in perfectly, paired at the top of the lineup with his partner in grime Wally Backman. I can close my eyes and bring him to life, blinking out at the pitcher with what looks like impatience, jaws worrying at the baseball-sized hunk of chewing tobacco in his cheek, fingers twitching and rearranging themselves on the barrel of the bat. In a minute he’ll have spanked a ball three-quarters of the way into the gap, certainly a single and just maybe a double, except it’s Dykstra and there’s no way he’s going to settle for a single, and he’s sliding into second face-first. Now he’s standing out there filthy and triumphant, with the enemy fans muttering and the pitcher stalking around in a little circle, and here’s Backman, his twin terror, staring out from the plate with his bat cocked like a trigger of a pistol, and if the pitcher doesn’t get Backman out the Mets are already up 1-0 and Keith Hernandez and Gary Carter are coming up and oh boy.

And if Dykstra doesn’t get that hit? If the ball hangs up long enough for the center fielder to glide over and pluck it out of the air? Then he’ll take himself back to the dugout, every step of the way marked by blinks of disbelief — Roger Angell described that Dykstra reaction as “his disbelieving, Rumpelstiltskin stamp of rage,” and as always it’s perfect. Dykstra succeeding made you laugh out loud for the sheer joy of what you’d seen; Dykstra failing made you laugh out loud for the cartoon fury he radiated. Years later, Dykstra told Larry King that after every game he’d take a minute to sit at his locker and ask himself a simple question: If he were a fan, would he have paid money to sit and watch him play? The answer was yes, most emphatically yes.

In October 1986 Dykstra struck a pair of critical blows for the Mets. He won Game 3 of the NLCS with a two-run walkoff homer off Dave Smith, averting what would have been a 5-4 Houston win and a 2-1 series lead. It’s another moment imprinted on my brain: Backman throwing his arms skyward, seeing the ball is gone; a few seconds later, Dykstra vanishes into a sea of blue jackets worn by larger teammates at home plate, nothing visible but his face. I was briefly worried his teammates would strangle him in their enthusiasm, but of course he was fine — wouldn’t you be, in the greatest moment of your life? Later, charmingly, he said the last time he’d hit a game-winning homer in the bottom of the ninth had been playing Strat-O-Matic against his brother.

Dykstra was at it again in Game 3 of the World Series, leading off at Fenway against Oil Can Boyd with the Mets down two games to none and panic in the streets of New York. Dykstra connected on a 1-1 pitch, the swing and trajectory reminiscent of the contact he’d made against Smith. The ball dropped beyond the Pesky Pole for a homer, leaving Boyd stalking around the mound and sending mutters through the Red Sox crowd. Dykstra all but strutted around the bases, walking into the dugout looking like a gunfighter who’d just cleared a street of outlaws. Though the ’86 Mets being who they were, maybe he looked more like an outlaw who’d just eliminated all the deputies.

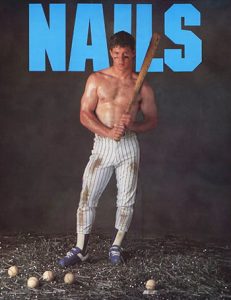

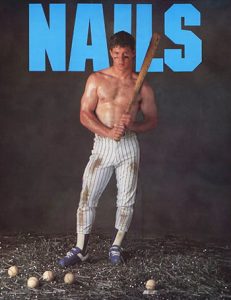

Of course he was a folk hero — how couldn’t he be? There was the poster — a shirtless Dykstra, looking about 12, surrounded by nails and baseballs. It was simultaneously awesome and deeply ridiculous. Or the video from 1986 Mets: A Year to Remember, which showed highlights of Dykstra and Backman, complete with extremely mid-80s effects, accompanied by Duran Duran’s “Wild Boys.” OK, that one was a lot more ridiculous than awesome — I remember realizing what was happening and trying, unsuccessfully, to sink through my couch and keep going until I hit the Earth’s core. Or how about his book, also called Nails? Dykstra wrote that one with Marty Noble, whom I imagined must have dined out on the stories of their collaboration for the rest of his life. After it came out in 1987, Dykstra proudly brought a copy into the spring-training clubhouse; a bemused Backman paged through it and said something like, “if you took all the ‘fucks’ out of this, it would be a 25-page book.” (Lenny’s verdict on Calvin Schiraldi, by the way: “Everybody gets the tight asshole sometimes.” Which might not be how I would have phrased it, but isn’t wrong.) Of course he was a folk hero — how couldn’t he be? There was the poster — a shirtless Dykstra, looking about 12, surrounded by nails and baseballs. It was simultaneously awesome and deeply ridiculous. Or the video from 1986 Mets: A Year to Remember, which showed highlights of Dykstra and Backman, complete with extremely mid-80s effects, accompanied by Duran Duran’s “Wild Boys.” OK, that one was a lot more ridiculous than awesome — I remember realizing what was happening and trying, unsuccessfully, to sink through my couch and keep going until I hit the Earth’s core. Or how about his book, also called Nails? Dykstra wrote that one with Marty Noble, whom I imagined must have dined out on the stories of their collaboration for the rest of his life. After it came out in 1987, Dykstra proudly brought a copy into the spring-training clubhouse; a bemused Backman paged through it and said something like, “if you took all the ‘fucks’ out of this, it would be a 25-page book.” (Lenny’s verdict on Calvin Schiraldi, by the way: “Everybody gets the tight asshole sometimes.” Which might not be how I would have phrased it, but isn’t wrong.)

1987 is the year Dykstra represents in A Met For All Seasons; it’s also, in retrospect, the year things started to go wrong. Besides his new, gloriously fuck-strewn book, Dykstra showed up encased in new muscle. “Lenny, what the fuck happened to you?” asked Backman. Dykstra’s response, delivered in front of teammates and reporters and everyone else: “Dude, been taking some of those good vitamins, you know?”

Dykstra hit 10 homers that year, a career high, but feuded with Davey Johnson about having to share center field with Mookie Wilson. Wilson didn’t like it either, and asked for a trade. The Mets eventually solved the problem in the worst of all possible ways, by trading both of them. In June 1989 Dykstra and Roger McDowell went to Philadelphia for Juan Samuel, who wasn’t a center fielder. Six weeks later, the Mets traded Wilson away too. Center field would be a tragicomic disaster in Flushing for years, and even as the Mets floundered and flailed to fill the position some small, mean little part of me would remember the day I’d heard Dykstra had been traded and think, Good, it’s exactly what you all deserve.

Meanwhile, Dykstra and Philadelphia proved a perfect match. In 1993 Dykstra — by now so inflated that he looked like a sidekick of Popeye’s — led the league in runs, hits and walks, finishing second to Barry Bonds in the MVP race and hitting .348 in the World Series with four homers. A town with a chip on its shoulder embraced a player with a boulder on his. Phillies fans adored Dykstra for his grit and hustle, for his belief that he was immortal, and for his refusal to be anything other than himself, regardless of the scorn that being himself brought his way. In ’93, after the World Series, Major League Baseball sent Dykstra on a goodwill tour of Europe (no seriously, they did), which you can read about here — is the best detail Dykstra buying a German shepherd in Dusseldorf because “this is where they come from” or the second bottle of Château d’Yquem he ordered to go after dining at Paris’s La Tour d’Argent? It’s a minor tragedy, at least, that this visit never produced a Get Him to the Greek-style comedy.

Phillies fans so loved Dykstra that they were willing to overlook the stuff that wasn’t so funny — such as the May 1991 car crash after a bachelor party that could easily have killed him and Darren Daulton, or someone else. (Dykstra blew a 0.179 on the Breathalyzer test, indicating a level of impairment somewhere between “you may fall and hurt yourself” and “standing and walking may require help, as balance and muscle control will have deteriorated significantly.”) They overlooked when Major League Baseball put him on probation for losing $78,000 playing illegal poker games with shady company in Mississippi. They laughed off stories like this one, from Philadelphia Magazine. But I read those stories too, and I gave him a pass of my own. Dykstra made mistakes, sure. He was obsessed with money, the trappings of wealth and the thrill of playing for high stakes — any Mets beat writer could have told you that. But he didn’t strike me as having a mean bone in his body — and there was an up-by-his-bootstraps honesty to his live-in-the-moment vulgarity that’s deeply American.

After 1993 injuries took their toll, particularly for a player incapable of pursuing baseball at anything less than dangerous speed. Dykstra retired after 1996, 33 years old and beloved in two very different cities. And since he retired, everything has gone horribly wrong. Or, perhaps, it’s gone pretty much as it went then, except there are no baseball heroics to make us want to hand-wave the rest away.

Sure, some of the stories were entertaining, such as Dykstra’s brief time in the spotlight as a stock-market guru, anointed by CNBC’s Jim Cramer as a homespun American genius. But others weren’t, at all. In 2011 he was charged with indecent exposure, allegedly for advertising for housekeepers on Craiglist, then announcing the job duties included massages and disrobing. (He served nine months.) In 2012 Dykstra pleaded guilty to bankruptcy fraud, concealment of assets, and money laundering and was sentenced to six and a half months in prison, the end point of an odyssey that began in 2009 with a bankruptcy filing connected to his purchase of Wayne Gretzky’s house. In 2018 he was charged with pulling a gun on an Uber driver who refused to let him change destinations, and for possession of cocaine and methamphetamines. (The drug charges were dropped and he pleaded guilty to disorderly conduct.) Dykstra launched a magazine, The Players Club, that he envisioned as the beginning of a concierge-cum-investment service for wealthy athletes. It crashed and burned, with one employee writing this scathing account of his time there. Among other things, he alleged that Dykstra had said that “nobody can call me a racist—I put three darkies and a bitch on my first four covers.”

Trying to untangle all this, I ran across this clip of Dykstra talking with Larry King in 2016. It was sad to watch Dykstra, still restless and fidgety but also now pudgy and gray, veer between defiance and remorse and never quite manage to land on either one. He almost makes it at one point, telling King that “that mentality that I had in baseball – do whatever I have to do, win at all costs – when you take that mentality out to the normal world…” But he never completes the thought. He’s off grabbing for the next thing.

Dykstra is a supporting character in Moneyball — Billy Beane told Michael Lewis about a day in the Mets’ dugout when the two were watching the opposing pitcher warm up and Dykstra asked who “that big dumb ass” was. An astonished Beane told Dykstra it was Steve Carlton, one of the greatest left-handers in the game. Dykstra took this in, sized up Carlton and announced, “Shit, I’ll stick him.”

“Lenny was so perfectly designed, emotionally, to play the game of baseball,” Beane said. “He was able to instantly forget any failure and draw strength from every success. He had no concept of failure. And he had no idea where he was.”

The same qualities that made Dykstra great on the baseball field made him a train wreck away from it. That’s what he almost finished telling King, and it seems like a grim but simple lesson. But then, last year, things got more complicated.

Darling wrote a book in which he revisited the Mets’ Game 3 World Series victory, and said something we hadn’t heard before. He said that while Boyd was warming up, Dykstra was in the on-deck circle “shouting every imaginable and unimaginable insult and expletive in his direction – foul, racist, hateful, hurtful stuff. I don’t want to be too specific here, because I don’t want to commemorate this dark, low moment in Mets history in that way, but I will say that it was the worst collection of taunts and insults I’d ever heard – worse, I’m betting, than anything Jackie Robinson might have heard, his first couple times around the league.”

By then, I was used to wincing whenever Dykstra’s name crossed my radar — because, as with Gooden, I assumed the news would be something sad and/or ugly. But this new allegation seemed hard to believe. It wasn’t that I was inclined to side with Dykstra over Darling — my inclination would be the reverse — but that I looked askance at the details and the setting. Fenway is tiny, with fans and players practically on top of each other, and Bad Stuff About the ’86 Mets has been a cottage industry since, well, 1986. Darling was clear that he heard what Dykstra said, and that Boyd did too. Which means dozens if not hundreds of other people must have heard it as well. And yet that story stayed under wraps for nearly a quarter-century? How was that possible?

Dykstra sued his former teammate for defamation and libel, which led to a rather extraordinary decision. The judge in the case reviewed Dykstra’s past missteps in excruciating detail, and wrote that “Dykstra’s reputation for unsportsmanlike conduct and bigotry is already so tarnished that it cannot be further injured by the reference. … In order to [assert a cause of action for defamation], Dykstra must have had a reputation capable of further injury when the reference was published.”

In other words, Dykstra’s reputation was already so wretched that it was impossible for him to be defamed — a hell of an addition to his other baggage.

Dykstra’s post-baseball life has been a drumbeat of stories that made you say, “Oh God, really?” — a few amusing, some merely tawdry and embarrassing, others frankly disturbing. And yet, even after all this, I find myself wanting to do mental gymnastics on his behalf — not to claim these things didn’t happen, but to somehow separate them from the exploits of a ballplayer who was always worth paying to see. I keep wanting a gulf between these two Lenny Dykstras. I think that’s why I don’t want to believe Darling’s story about Game 3 — it’s a bridge over that gulf, an insistence that no such separation is possible, and an assertion that there’s only ever been one Lenny Dykstra.

I keep fighting that idea, and I’m not sure why. Because isn’t it the same insight I had all those years ago, the one that steered me away from sportswriting? Appreciate the players for what they do, and be careful about delving too deeply into who they are. Because you might wind up liking them less. Even if that’s a verdict you want desperately to resist.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1965: Ron Swoboda

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1967: Al Schmelz

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1971: Tom Seaver

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1974: Tug McGraw

1975: Mike Vail

1976: Mike Phillips

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1986: Keith Hernandez

1988: Gary Carter

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1997: Edgardo Alfonzo

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2007: Jose Reyes

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2010: Ike Davis

2011: David Wright

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2017: Paul Sewald

2019: Dom Smith

by Greg Prince on 28 September 2020 3:03 pm But after all, it’s what we’ve done

That makes us what we are

—Jim Croce

On one hand, the Mets were defeated in embarrassing fashion on Sunday, losing to the Nationals, 15-5, leaving them at their low-water mark for 2020, eight games below .500 and tied for the worst record in the National League East.

On the other hand, the Mets played, which they won’t be doing tonight or tomorrow or any day again for real until April 1, 2021, and we cite that inadvertently ironic date only because it’s been printed somewhere, not because we any longer take schedules, or much, as certainties.

I prefer the Mets not lose by ten runs, not finish basically last, not show little gumption down what passed for a stretch and not demonstrate a disturbing lack of pitching depth. I prefer the Mets not play in front of essentially nobody except cutouts and camera operators.

But I did like that they played. It struck me as ridiculous, while Covid-19 first spread through America, that they and their counterparts would try, yet whatever I thought I put aside to watch and listen, because, as ever, that’s what I do where the Mets are concerned. I do it as willingly as I do semi-kvetchingly.

It wasn’t a season to cherish. Not at all. Not without you or me invited to pass through big league turnstiles and grab a ballpark seat and turn to somebody else who did the same and ask, whether from a source of pride or surfeit of disgust, “How about those Mets?”

Say, how about those Mets? They weren’t very good in 2020, were they?

In any given five-day stretch, you could count on an average of one-and-three-quarters starting pitchers to position us toward victory. There was deGrom and there was, now and then, somebody who looked pretty solid. For a few spins of the rotation, that was Seth Lugo. Sunday, it wasn’t. Seth got lit up by the Nats Sunday. So did just about every one of the umpteen relievers who followed him to the mound. Those who weren’t lit up set themselves on veritable fire via the base on balls. Some days we thought we had this bullpen thing licked. Other days were Sunday.

That lineup of ours, though. When it wasn’t submitting to attrition in the final days — Conforto went on the IL with a tight hamstring; Giménez went on the IL with a tight oblique; Smith sat after running facefirst into a wall — it was pretty impressive. No National League team compiled a higher batting average…although six teams scored more runs, so maybe the impressions were fleeting. Their most imposing player coming into the season, Pete Alonso, was also their most imposing player heading out, hitting five home runs over the club’s final eleven games, including two on Sunday. Pete finished 2020 with 16 homers. His disappointing sophomore campaign picked up steam just when it had nowhere left to go.

Dom Smith hit .316, slugged .616 and drove in 42 runs. Michael Conforto was a .322/.412/.515 slasher. Jeff McNeil heated up to rates of .311/.383/.454 after an icy start. Robinson Cano was the personification of “the old guy’s still got it,” batting .316, slugging .544 and mentoring his juniors. The youngest among them, Andrés Giménez, impressed everybody in the field and at the plate.

But collectively they still didn’t score enough. They didn’t run brilliantly and, Andrés to the contrary, they didn’t necessarily catch most of what they should have or could have. The hitting that came in waves dried up at inopportune junctures. The pitching was untrustworthy when it wasn’t Jacob deGrom’s turn to throw, only semi-reliable in the hands of Lugo, David Peterson and select relievers. Edwin Diaz’s talent sometimes seemed worth whatever was surrendered to secure it, if hardly always.

So, no, they weren’t very good. They let us down repeatedly, in numerous ways, but they were around to anchor us, at least a little, amid too many public infuriations and perhaps private heartbreaks to enumerate if we wish to resist turning around and going back to bed.

But we watched and listened. I watched and/or listened to all sixty games, rooting for the Mets, cheering for Gary Cohen, Howie Rose and Wayne Randazzo mostly. They were the show for me. Baseball in 2020 was improvised as a broadcast-only enterprise, and those fellas (with contributions from Keith Hernandez, Ron Darling and Steve Gelbs on the TV side) did the heavy lifting. Gary, Howie and Wayne hit it out of the park more consistently than Alonso, Smith and Conforto even though they had the advantage of being in the park where a game was being played only about half the season. Announcers and production crews didn’t go on the road. The game had to come to them via video, then through them, then to us. They brought it winningly. For me, WCBS-AM and SNY went 60-0. Say what you will about the Wilpons, but they never chased away Rose, Randazzo or Cohen and, as far as can be divined, none among Fred, Jeff and Saul ever meaningfully got in their way. The only thing that could ever impede my Mets fandom to the point of abandoning it would be if the next owner stuck one too many cents between himself and those golden microphones.

Putting aside my darkest Metsian fear, I can’t wait to see what the Mets under Steve Cohen, should he be approved (remember: nothing is a certainty), will be like as a going proposition in 2021 and beyond. When I first took up with the Mets in 1969, I didn’t know who the team owner was or what a team owner was. When I discovered it was Joan Payson, it didn’t matter to me. The Mets did what it took to win, from what I could tell. Then Mrs. Payson died and free agency was born. It’s a shame Mrs. Payson couldn’t have lived to have had the opportunity to sanction the pursuit of every desirable player on the open market — or to compensate existing Met players to their satisfaction and thereby convince them to not test the open market en route to leaving us behind.

Let’s not pretend the Mets have never pursued a player or paid him fairly since the advent of free agency in 1976. But have you ever had the prevailing sense, particularly dating back to August 23, 2002, that somebody who owned the Mets cared to the core of his soul about how the Mets were going to do and made it his priority to have a player in a Mets uniform to help the Mets do as well as they could? Not for business reasons, not because somebody decided the cut of somebody’s jib came across swimmingly over lunch at some country club, but because, dammit, I love the Mets, I own the Mets and I want this guy ON the Mets?

That’s my best-case conception of Steve Cohen, owner of the Mets. He doesn’t have to throw the bucks around willy-nilly (or at Willy Nilly, a strong-armed outfielder who spend most of 2020 at the Tigers’ alternate site in Toledo). He just doesn’t have to rule it out, and then he can act accordingly — act like a well-resourced, well-informed fan. With Sandy Alderson set to be among those informing him, I’m confident the stream of information he’ll be receiving will be valid. One dares to assume (even as making assumptions falls under the heading of there being no such thing as certainties) that Cohen has his systems for figuring things out and making the most of them.

That, MLB approval and good global health willing, is for 2021 and beyond. For 2020, there was 26-34, starting late and ending too soon. The eight-team playoffs in each league will commence with too many teams, yet one shy of the ideal assortment in the NL. It would have been nice for the Mets to have taken part. Then again, as my friend Kevin suggested of the ad hoc alignment when it was announced in July, if we sneak in and get knocked out, that’s a playoff banner I could do without seeing hanging off the Excelsior facade.

Like we wouldn’t have taken it and run with it, but we didn’t get it. But we did get the season. Or seasonette. There is no internal mechanism to deal with a sixty-game season as complete or substantial, yet we just had one and we engaged its substance as circumstances allowed. We didn’t wait around for four months to turn up our noses at something that, in immediate retrospect, now seems so disposable. Why wouldn’t we dispose of it? It barely happened, then it was over; it was blazingly unsuccessful and all we want to do is turn to the next chapter, the one that introduces the new owner to the official narrative.

The 2020 season may have been here and gone and acknowledged as authentic only grudgingly, but it happened. Because it happened, I got to tune into Gary on television, Howie and Wayne on radio and, best of all, the baseball frequencies in my head. For example, when Guillermo Heredia led off the top of the second inning Sunday afternoon at Nationals Park with a home run off Austin Voth, the center fielder’s second of the season, I made a mental note to take Heredia off a list I keep on my computer. The list encompasses every Met who has hit exactly one home run as a Met. Every player who hits a first home run for us enters the list, and every player who hits a second exits it. Those who stay stuck on one stick on the list, from Gus Bell on April 17, 1962, to Robinson Chirinos on September 24, 2020. There are 84 players listed in all. Until this morning, there were 85.

The modest act of highlighting Heredia and the details of his first homer (against the Rays’ John Curtiss at Citi Field last Tuesday) with my cursor and then pressing the delete key was made possible by the existence of the 2020 season. Hundreds of such notations I think over, jot down and type up — debuts, returns, milestones — were made possible because they happened. Because the 2020 baseball season happened. Every season those exercises constitute my baseball season as much as watching, listening, cheering, kvetching and blogging. All the minute details filling a borderless canvas. It’s numbers and actions and moments just occurred balanced lovingly atop moments ages ago enshrined.

I care about Heredia having more than only one Met home run because ten years ago I grew fascinated that Mike Hessman, a minor league bopper, joined the Mets, hit one home run and, when it appeared he’d hit a second, had it reversed via replay and ruled a triple, which was absurd because Mike Hessman had no speed and, had the ball he hit been considered in play in the first place, he would have stopped at second with a double.

But Mike Hessman had one home run and one home run only. Hessman would be gone soon after 2010 ended, but who else was like him? I looked it up.

Frank Taveras was like him — just one home run as a Met (though 12 triples between 1979 and 1981).

Alex Cora was like him, though not at all the same style of player. Cora the prototypical heady middle infielder with limited pop and Hessman the corner power guy who struck out too often to avoid Quadruple-A status overlapped on the same Met roster for precisely a week. In the interim, the lucky Louisville Slugger had been passed to a new generation.

Esix Snead was like him, except Snead hit his one homer to win a game in extra innings in September of 2002 and it was the most fulfilling moment of the waning days of a season that felt far worse in its time than this one feels in this, and not only because it was the year the Wilpons bought rather than sold majority interest in the franchise.

Tony Fernandez was like him, in arguably the worst of Met seasons, 1993. One-hundred three losses, countless embarrassments to the cause of humanity, but one home run for Tony Fernandez, same as Sid Fernandez who hit one in 1989, making El Sid one of 22 Met pitchers with exactly one home run hit as a Met. One of the other 21 was Matt Harvey, who hit his one Met home run, in 2015, off the same pitcher, Patrick Corbin, that Robinson Chirinos hit his one Met home run off last week. One of them was Seth Lugo, who started the last Met game of 2020, the one in which Guillermo Heredia doubled Lugo’s Met home run total by hitting his second for us. No matter how good Seth might be as a starter in 2021, it doesn’t appear he’ll ever hit another home run as a Met. But that’s another story (and a downright shame).

Somewhere post-Hessman, I made my list. There were lists begun before it. There’ve been lists begun since. Every Mets game is an excuse to update at least a couple of them. Some baseball fans referred to the 2020 regular season as a distraction from worrying about the effects of the pandemic or facing up to existential threats to representative democracy. Me, I had the opportunity to note, among myriad other occurrences, that on September 23 — one night after Heredia took Curtiss deep and one night before Chirinos took Corbin deep — the Mets’ record landed at 25-31.

And? And it was the FIRST time the Mets ever sported a record of 25-31 after 56 games…if one can be said to sport a record of 25-31. It’s more something an obsessive type types quickly, clicks close on and keeps mostly to himself.

But then I opened it just now and shared it with you here on the remote chance you might find it interesting. Or that you find finding so much about baseball interesting, which I’m gonna guess with great certainty that you do. Your interest, whatever shape it takes, got you into baseball, got you to stay with baseball, got you to 2020 and through 2020 and will take you to 2021, no matter the onslaught of uncertainties and imperfections surrounding us.

It got you to this space. Thanks, as always, for dropping by. We’ll be here all winter, however long it lasts this time around.

by Greg Prince on 27 September 2020 12:04 pm I applaud the Mets’ continual affirmations of confidence. You Gotta Believe should extend to belief in oneself. But after watching the Mets’ wisp-thin playoff eligibility expire in the first game of Saturday’s doubleheader in Washington — and having their status confirmed in a less competitive loss in the nightcap — I’m having trouble abiding by the idea that this is some juggernaut that was steaming toward the postseason until it took a wrong turn on the Beltway.

There has to be a center lane that merges the power of positive thinking with a grip on reality. Throughout this brief year, the Mets have been at a loss for explaining why they’re not living up to their perceived awesomeness. These attempts at explanations have taken place after losses, of course. Saturday, after the two latest, the song was essentially the same.

Dom Smith: “We fought hard, we fought until the last pitch, even tonight. Obviously, we weren’t able to overcome certain circumstances. It just shows the character of the group. We never gave up, we never gave away games, and we competed until the last out.”

Pete Alonso: “I feel like this team is built to win. We have just a ridiculous amount of talent. It’s unfortunate we couldn’t put it together within the sixty-game time span.”

What season were they watching? Because if it exists, I want to rewind it and luxuriate in it. Then I want to surf its momentum into next week when this awesome Met behemoth roars into the Wild Card round as the National League’s 1-seed.

The performance at some point has to measure up to the perception. Even in a season undeniably like no other, you have to win games before declaring victory. The 2020 Mets didn’t win nearly enough of them. Though it was fun to take their minuscule chance at advancement seriously for a few hours before first pitch Saturday, this was a team that, as a rule, performed dreadfully from late July to late September, which unfortunately encompassed all the months they had to get going. In 2019, Alonso, Smith and the rest of the Cookie Club had six months. They revved it up late in the fourth month and rode out the schedule on a well-earned high. It was chilling and thrilling and all those things we wish from an August and September.

That was last year. This year is nothing like last year in any capacity, but it did offer the Mets the same sixty opportunities it offered their competitors. Within the NL, making the most of thirty of those opportunities would have amounted to succeeding at baseball without really trying. These Mets couldn’t do that. That’s fine within the realm of balls bouncing and cookies crumbling. As Mets fan Matthew Broderick once belted out on Broadway, “Mediocrity is not a moral sin.” A hard-bitten fan can accept a 26-33 entity with fairly decent humor. I don’t mind a 26-33 team looking in the mirror and seeing a 33-26 (or better) team staring back at it. But to regularly slide in front of the Zoom camera and tell all interested onlookers that it’s a mystery we’re not 53-6 right now…guys, seriously, look in the mirror again. Watch the video from the doubleheader. Cue up more than half of your 2020 archives.

Build from this year. Learn from this year. Strive for next year. Forget about last year, which is about to be two years ago, at least in terms of apparently deciding you deserved to be wearing the same gold-trimmed uniforms the Nationals have been modeling in 2020 (like that helped them repeat). I loved the stretch run of 2019, no matter it was a coupla bucks short and at least a month too late. It reinvigorated my waning enthusiasm for the franchise. It made me eager for the future. I’m still eager for the future. It didn’t arrive as any of us wished this past March or July, but there’s always more future as long as somebody says you can play. I join you in your confidence that it can still take the shape we desire. Why not? No games have been played in 2021 yet.

All but one of ours have been played in 2020. There are more for a majority of major league teams, but not ours. There’s a reason for that. We weren’t good enough. We weren’t remotely good most of the time. I say “we” because I’d like to think we win together and we lose together, regardless that some of our uniforms have yet to be delivered from Stitches of Whitestone. If this was all second-person accusatory, you’d be on your own and we wouldn’t care. That’s not the case. We are with you, Dom. We are with you, Pete.

We are with Jacob deGrom who always provided rational hope if not, in his last start, requisite length. Jake went five pitch-laden innings. It felt like a crushing late-September outing from a grizzled ace who’s carried too much of his staff’s burden for too long. And he was still more than pretty good (3 ER, 10 SO) in his five endless innings. DeGrom left us a tie, with one of the runs scoring on a wild pitch — Wilson Ramos’s bat and mitt giveth and taketh in equal proportion — and another on an inside-the-park home run that flicked off of Dom’s glove in left before the padded fence beckoned his face. Dom, thankfully, was all right, but the ball Andrew Stevenson (who’d homered over the fence earlier) hit sat unattended for four bases. No wonder Dom’s in favor of the DH.

Once Jake threw his 113th pitch for the third out of the fifth inning, we knew he wasn’t coming back for the bottom of the sixth. And once the Mets didn’t do anything constructive with a first-and-third in their half of the sixth, we could guess playoff elimination was at hand. First clue: Miguel Castro walked leadoff batter Brock Holt. Everything else thereafter was details. The final of the opener was 4-3, Nats. The nightcap loomed as spectacularly futile.

And it was, scorewise, with Rick Porcello giving up five runs (three earned) in the third inning of the day’s second seven-inning game. The Mets would lose, 5-3, indicative of some of their fighting until the last pitch, in that the Mets stuck around Nationals Park for the remainder of their contest rather than retreat to their hotel. It is my instinct to dismiss what was almost certainly Porcello’s final start as a Met with “typical” because, quite frankly, it was. Rick finished 2020 1-7, with an ERA of 5.64. A decent outing or two notwithstanding, we got next to nothing from Rick Porcello this season, same as we got next to nothing from too many pitchers to recite in polite company.

Yet we are with Rick Porcello, or oughta be. Maybe not for 2021 — definitely not for 2021 — but in eternal spirit, yes, Rick from Jersey should be our guy. I’ll admit that despite his local breeding and Mets fan roots, he was never mine. One night this abbreviated season, I got in the car after my weekly grocery-shopping trip, turned on the game, discovered it was another Porcello start going quickly awry, and muttered some pretty nasty thoughts aloud in the direction of a fella who couldn’t hear me. But on Saturday night, after the sweep in D.C. was complete and the Mets dangled one game above finishing in a last-place tie, Rick Porcello took it upon himself to basically apologize for how crummy he and the rest of Mets played in 2020. It was enough to almost make me take back my previous grumblings.

“I’m sorry we couldn’t have done better for you, and given you something to watch during the postseason,” the righty said, noting that he was happy he could at least be a part of giving us folks at home a distraction from all that swirls about us. “I wish I could’ve done better for this ballclub. Unfortunately, we’re out of time. I gave it my all and it wasn’t good enough for us.”

Rick concluded by adding, “I love the Mets, I’ve always loved the Mets since I was a kid.” It would figure that someone who realized a lifelong dream of playing for “a team I grew up cheering for” would know exactly what to say to us, a cohort that surely includes him.

by Greg Prince on 26 September 2020 5:50 pm The 2020 New York Mets are not and were never a playoff contender. We regret any role we played in indicating anything otherwise. Thank you.

by Greg Prince on 26 September 2020 8:54 am When the Mets don’t play, the Mets don’t get eliminated. We may have found the 2020 formula for relative success.

On Friday night, the Mets were rained out in Washington. As the evening went along, the palest of suns shone on their fortunes. Philadelphia lost. San Francisco lost, despite the best efforts of heretofore lovable scamp Wilmer Flores. Milwaukee and St. Louis split, though I’d be hard-pressed to discern exactly how that was good, bad or indifferent to our cause. When I awoke this morning, I pored over the scores, the standings and the statistical possibilities for about an hour, or about hour more than I had in toto in this mini-season.

Here’s what they used to call on W. 4th St. the bottom line: the Mets are still alive for a playoff spot. Or they’re not dead yet. They remain one of the precious few MLB teams that doesn’t have a denotation next to their name indicating all the way in or please stay behind the velvet rope. Their chances are thinner than the diner patron who consistently orders the Slenderella, subsisting on no more than a naked hamburger patty, a cling peach slice, a scoop of low-fat cottage cheese, a single Melba toast and unlimited parsley. But if that’s all we’re getting for lunch, we’ll take it to go and savor it at one of the outdoor tables.

Here’s what we — us and our 26-31 team, who are one and the same when the situation suits us — have to do to keep going today, this penultimate Saturday of the irregular season:

1) Stop laughing that a team five games under .500 with three games remaining is somehow passing itself off as a playoff contender. It’s too late for judgments.

2) Win the first game of the doubleheader against Washington, scheduled to start at 3:05 PM.

3) Win the second game after winning that first game. The second game will start thirty to forty-five minutes after the completion of the first game. If the first game is a loss, you’re excused from the rest of this game plan.

4) Revoke every sympathetic sentiment we ever held for Zack Wheeler missing out on the Met playoff runs of 2015 and 2016. He pitches tonight for Philadelphia at Tampa Bay. Wheeler’s been waiting all his life for this moment. Let’s ask the Rays to make him wait a little longer. It’s the least they can do for us after we were such gracious hosts for their division-clinching.

5) Get the Brewers out of the way. I believe we need them to lose one of their final two games versus the Cardinals, so their fate isn’t immediately intertwined with ours where Saturday is concerned. But we do need them to lose one of two. If the Brewers start winning everything in sight, then maybe the Cardinals and their potential Monday makeups with the Tigers become our concern, which already sounds like six bridges too far.

6) Root the Padres on to another win over Wilmer’s Giants…if we haven’t lost the first game against the Nats and/or aren’t on our way to losing the second once the Padres and Giants get underway out west, which is where we’re striving to fly to days from now to face L.A., but sure, let’s get way the bleep ahead of ourselves; we’re still five under .500, still in nothing resembling playoff position, still needing to land coins on their edges rather than heads or tails and I’m that reporter asking Jim Mora about playoffs?. But if steps 1 through 5 come through, brew up that Bigelow and prepare to stay awake.

7) Remember the Maine! We were almost dead on the penultimate day of 2007, then John Maine went out and pitched the game of his and almost everybody else’s life by nearly no-hitting the stupid Marlins that Saturday and setting us up for Game 162’s devastation, but at least it was one more day of life.

8) Remember the Santana! We were almost dead on the penultimate day of 2008, then Johan Santana somehow outdid what Maine had done by shutting out the stupid Marlins that Saturday and setting us up for Game 162’s devastation vu, but at least it was one more day of life then, too.

9) Congratulate the stupid Marlins on breaking their seventeen-season postseason drought. Good manners suggest it. Good karma demands it. They’ve changed their address since 2007 and 2008 from “Florida” to “Miami,” though they’re still “stupid” and can still rot in “Hell” for those final weekends thirteen and twelve years ago, but let’s be sports about this. Besides, beating the Yankees anytime deserves at least a virtual elbow bump.

10) For cleaner precedent, remember we clinched a playoff spot on a penultimate day, in 2016. It was a Saturday. It was an unlikely haul to get there, rising from 60-62 on August 19 to 87-74 on October 1, but we got there. It didn’t get us more than one Wild Card game, but it was something to behold in its time.

Going 27-12 in a span of six weeks and surpassing several contenders to make the postseason was cake compared to the crumbs we have on our plate today. if everything goes right today, it doesn’t get us into the playoffs. It gets us to Sunday and another set of gymnastics. Still, a few months ago, I wouldn’t have bet on any baseball team getting to the end of September at all, but here we are, with baseball and the Mets playing dare I say something approaching a meaningful version of it. We’ve got our Cy Young winners going today, Rick Porcello and Jacob deGrom. No, Porcello didn’t win one for us, but neither did Santana. I’m grasping at straws and groping for possibilities, if only because if I don’t now, I won’t have this opportunity again for at least a year.

The pursuit of better than nothing continues until it doesn’t. When it ceases, we can return to retroactively mocking that we ever took it remotely seriously; entombing it for obscure posterity; and looking forward to maybe a real owner in a couple of months and maybe a real season a few more months beyond that. For now, there’s little we can say definitively, except this: Let’s Go Mets. One or two or perhaps three more times with feeling.

by Jason Fry on 25 September 2020 11:00 am Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

I kicked off my half of our Met for All Seasons posts with a remembrance of Rusty Staub, my first favorite player — and how he turned out to be an ideal choice. That’s no surprise — Staub was a legendary Met regular, an iconic Met role player, and a beloved alumnus, as well as one of those rare players who crossed the white lines to become a New York City presence as well.

My second favorite player, the one who replaced Rusty in my heart after his shameful exile to Detroit, was a less obvious choice — more “oh yeah that guy” than legend, and a man for whom New York was one in a series of addresses and not a home. But he did just as much to make me a Mets fan. And maybe more.

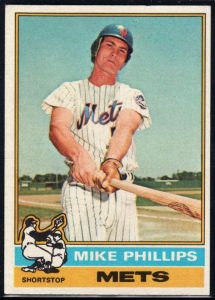

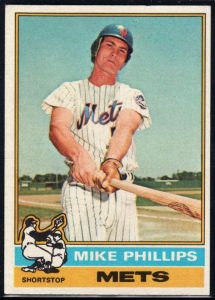

Why did I fall in love with Mike Phillips, utility infielder for the mid-Seventies Mets, and our Met for All Seasons for 1976? The simple answer is because I was a weird kid.

The pride of Irving, Texas. In 1976 I was already a Mets fan, thanks to Rusty Staub and my mom. (Getting to watch Tom Seaver helped too.) But the Mets weren’t an all-consuming passion. I also loved to draw and make up stories. Mostly these were about superheroes — Star Wars was still a year away from capturing my imagination, but I loved my Mego action figures, the ones that were basically dress-up dolls for boys, complete snaps in the back of their fuzzy tunics and weird clawlike mittens instead of gloves. (My friends and I would have been horrified by that description, but look at these things and tell me it isn’t true.) I didn’t care for the Marvel superheroes, which had an arriviste whiff, but I staged endless epics starring Batman and Robin, sometimes joined by Superman and even Aquaman, with his otherworldly shock of highlighter-yellow hair.

When I couldn’t cart around my collection of superheroes, I brought them to life on paper, which was in ready supply for the child of two academics. I primarily drew Batman and Robin, but eventually I tired of familiar caped crusaders and tried something new: superheroes of my own invention.

I don’t remember the name of the superhero I invented, but I do remember he had a secret identity, because every masked man needed one of those. And the secret identity I chose for my creation was “Mike Phillips.”

I know what you’re thinking, but I’m pretty sure you’re wrong. Yes, I was a Mets fan by the mid-Seventies. But I don’t think I was enough of a Mets fan to have cribbed that name from a utility player who’d arrived in 1975 on a waiver-wire deal. Nor do I recall my parents being conversant enough with the roster to bring up part-timers and fill-ins. I think it really was a coincidence.

But it would turn out to be a pretty important one. In 1976 I started collecting baseball cards, which supercharged my fandom by giving me biographies and stats and factoids I could pore over and memorize. And so I was stunned when I saw that there was a 1976 New York Met with the same name as the superhero I’d drawn on the backs of about a thousand no-longer-needed SUNY class handouts and memos. Clearly this was the hand of fate, stretched down from the baseball gods to a seven-year-old kid on Long Island and indicating, This is the path. Follow it to happiness. (Or, well, since you’re a Mets fan, at least something happiness-adjacent.)

Like I said, I was a weird kid. Maybe that’s why the hand of fate pointed at a journeyman infielder — Seaver would have been too easy. But maybe there was more to it than that.

Phillips was born in Beaumont, Texas, and attended MacArthur High in Irving, a school whose most famous sports alumnus is Brian Bosworth. He lettered in baseball, basketball and football, which caught the attention of the San Francisco Giants. They drafted him in 1969 and he reached the big leagues in ’73 as a backup to Chris Speier despite never having hit over .250 at any minor-league stop.

Phillips’ tenure with the Giants would form the blueprint for his career: He wanted to play and never really got the chance. As a rookie, he hit .240 and saw action at shortstop, third and second. The Giants liked his versatility, and he came to spring training in 1974 as the favorite for the third-base job. But the club opted for Steve Ontiveros instead. Phillips got into 100 games, but only hit .219 and made 19 errors. He wanted out, and the Giants granted him his wish in ’75, putting him on waivers.

Enter the Mets, who needed a replacement for Bud Harrelson and his increasingly gimpy knees. Phillips got the bulk of the time at shortstop, and while the results weren’t the stuff of statistical wows — a .256 average and a 0.5 WAR — both team and fans appreciated his gutty play and knack for clutch hits, rewarding him with more than 330,000 write-in votes to the All-Star Game. (He wasn’t selected.) But while Phillips’ positional versatility brought up the old “Jack of all trades” saw, his defensive stats were a reminder of the “master of none” thing — he led National League shortstops with an ugly 31 errors.

1975 wasn’t the springboard Phillips had hoped for. His defensive improved in ’76, but so did Harrelson’s knees, and Phillips was back to sharing time and moving around the infield. In ’77, the Midnight Massacre meant the end of his Met career, as Doug Flynn‘s arrival and a .209 average made him superfluous. The Mets shipped him to St. Louis for Joel Youngblood, making me probably the only Mets fan in the world who was more upset about June 15’s third-paragraph dog-for-cat trade than the departures of Seaver and Dave Kingman.

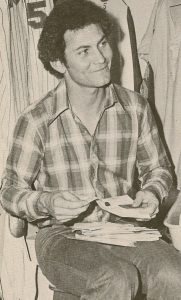

As with Staub, I continued to carry a torch for my lost hero. Phillips found himself in a familiar situation with the Cardinals: He wanted to be a starter and wasn’t given the chance. I knew this by following box scores and was even ticked about it than Phillips was — and when my parents took me to see a Mets-Cardinals game at Shea in 1978, I arrived bearing a declaration of war.

My message for Cardinals skipper Vern Rapp was as lengthy as it was angry:

HEY VERN IF YOU WANT A BENCH WARMER GET A HEATING PAD BUT DON’T USE MIKE PHILLIPS

A couple of points should be made here.

1) To be read by anyone in the Cardinals’ dugout, this message would have required multiple bedsheets and poles and the cooperation of at least a section’s worth of fans, assuming the wives of the 1969 Mets weren’t on hand, as they probably weren’t for a regular-season game nine years later. I didn’t use multiple bedsheets, however — I used a single sheet of letter-sized construction paper.

2) Said single sheet of letter-sized construction paper wasn’t white, but forest green. It was unreadable 20 inches away, to say nothing of 200 feet.

3) I have no idea what 1978 Mets-Cardinals game we attended, but the first one was May 29, and Rapp had been fired on April 25, replaced by Ken Boyer.

Did I make the least-effective banner in the history of spectator sports? It’s got to be at least a contender.

Little does he know every letter is from the same weird kid in East Setauket, N.Y. Phillips moved on from the Cardinals to the Padres and finally to the Expos, with his career less an arc than a flat line. It ended in 1983 much as it had begun, with him sticking around because he was useful but never really getting to play. Montreal was a strange and undoubtedly frustrating limbo in which he was equal parts player, coach, instructor and none of the above. The Expos released Phillips three times in 16 months: in May ’82, June ’83 and finally for keeps in September ’83. His final career totals: 412 hits over 11 years, a .958 fielding percentage, and one season with a WAR above 1. After his career, Phillips went into marketing, which eventually brought him back into baseball — he was director of corporate sponsorships for the Rangers and oversaw all corporate revenue for the Royals. That’s an interesting second life for a player — two high-ranking jobs that had little to do with the nuts-and-bolts experience of being a player.

But let’s go back to 1976, the best year of Phillips’ career — and the one in which he meant everything to me.

My one memory of Phillips as an actual Met is seeing him hit a leadoff homer, with his name immediately popping up in yellow capital letters on the screen, which was Channel 9’s way of noting round-trippers. That’s the entire memory — I have no context beyond it, and when I sat down to write this piece, I wouldn’t have sworn that what I recalled was accurate. Plenty of memories from when you’re seven years old turn out to be incomplete, distorted or fundamentally incorrect.

So I checked. In late June, the Mets rolled into Wrigley Field for a three-game series with the Cubs. The team was 34-37, far off the pace in the N.L. East, and Phillips was hitting .207. In the first game, Phillips played short and hit leadoff. He struck out looking against Ray Burris to begin the game, but doubled in the third, tripled in the fifth, homered in the seventh, and grounded a single in the eighth. That made Phillips the third Met to hit for the cycle, joining Jim Hickman and Tommie Agee. The Mets won, 7-4. The next day, they romped to a 10-2 win with Phillips scoring three runs and homering — but in the eighth. In the third game, the Mets completed the sweep with a 13-3 bludgeoning of the Cubs, moving to 37-37 on the year. Phillips led off again — and, as I discovered to my delight, he opened the game with a home run to deep right off Rick Reuschel.

That home run was part of the best week of Phillips’ career. He arrived at Wrigley with four home runs as a big-leaguer and left with seven. He hit for the cycle. And soon after that, he was named the National League’s Player of the Week.

So my memory was accurate: I’d seen him go deep off Reuschel on our Sony color TV, watching Channel 9 on a summer Sunday afternoon. Did that week, that game and that moment in particular make me the Mets fan I’ve been pretty much ever since? It might have.

I adopted a utility player as my favorite because of a coincidence involving names and tried to will him, with all the fervor a seven-year-old could muster, into becoming the star I’d imagined. That was too much to ask for a career, but not for a week. For a few days, Mike Phillips really was a superhero. And he donned his cape at the perfect time to transform a little kid’s curiosity and interest into a lifelong passion. The hand of fate may have been pointing somewhere unexpected, but it really was showing me the path.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1965: Ron Swoboda

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1967: Al Schmelz

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1971: Tom Seaver

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1974: Tug McGraw

1975: Mike Vail

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1986: Keith Hernandez

1988: Gary Carter

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1997: Edgardo Alfonzo

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2007: Jose Reyes

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2010: Ike Davis

2011: David Wright

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2017: Paul Sewald

2019: Dom Smith

by Jason Fry on 24 September 2020 11:35 pm The beginning of a baseball season is light and consequence-free — with six months of games ahead, you can relax a bit, allowing yourself to simply enjoy having baseball as a companion again. Starting in June, things begin to get serious — you’re conscious of the standings, of opportunities taken and missed and lost. This reaches a fever pitch in September. But then, if things go poorly? You wind up back to lighter-than-air games.

They feel different, of course — they’re consequence-free because you’re out of it* and just playing out the string. But sometimes there’s a strange relief to that. The needle has not been threaded. The dominoes have not all toppled in the precise configuration you needed. It’s disappointing, but it’s happened, and why would you stalk away from baseball in a snit with so little of it left? So you watch.

I watched — though an asterisk (or an asterich, as it turns out Keith Hernandez pronounces it, to the bafflement of Gary and Ron and everyone watching) wouldn’t be unfair, since I forgot the game started at 6, arrived in the third inning, and then Emily and I talked with our kid on the phone during two tense innings near the end. But that’s OK — consequence-free, remember?

Such September games also bring an awareness that you’re seeing some players for the last time — statistics harden into their final form as starting pitchers complete their yearly duties and position players exit the stage for a variety of reasons. Before the game the Mets put Michael Conforto on the IL, ending his wonderful breakout season. Then they gave the ball for the final time to rookie David Peterson, who looked as good as he has all year, stifling the Nationals to earn his sixth win and finish with an ERA below 3.50. Peterson is going to lead the club in wins; he arrived as an unknown quantity and departs as someone the Mets can write into their 2021 starting rotation in pen. After a year of erasures and crossouts and expletives written in the margins, that’s a welcome development.

It was also a Mad Lib game. What’s a Mad Lib game? It’s a game where the key moments are produced by guys who weren’t in the original plan — for instance, when Guillermo Heredia spanks a sharp single to right off Patrick Corbin and Robinson Chirinos follows him with a grinding at-bat that finally yields a sinker that doesn’t sink and a two-run homer. Heredia and Chirinos! Just like we imagined it in, um, July!

There were some good moments from better-known entities, too — such as Justin Wilson facing the deadly Juan Soto as the tying run in the bottom of the eighth and coaxing a foul pop that Todd Frazier‘s vaguely animate corpse managed to corral, then dueling the deplorable Kurt Suzuki through a 12-pitch at-bat that ended in a harmless grounder and a fielder’s choice. An inning later Edwin Diaz — who’s not back to trustworthy but is a lot closer than we would have imagined not so long ago — bent but didn’t break and the Mets had won.

The Mets had won. It doesn’t matter, except that there was a Mets game to be watched when soon that won’t be the case. And that certainly does matter.

* “But wait the Mets are not done because X and Y and Z and carry the 1 and flip this exponent!” Sure, Jan.

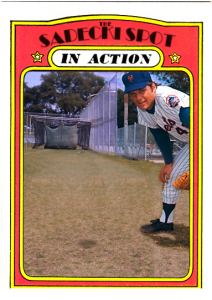

by Greg Prince on 24 September 2020 12:30 pm The online Mets fan world suffered a loss this month when Warren Fottrell passed away at the age of 62. Though the name might not ring a bell, his work would probably elicit a ripple of recognition from anybody who’s ever clicked around in search of Met images. Inevitably you’ll find pictures of baseball cards that were too wild to be something you ever pulled from a pack. If you could, you’d have never stopped collecting.

Life is just a Fantazy when you’ve made it onto one of Warren Fottrell’s cards. That was the work of Warren, who generally went by the screen name of Warren Zvon or variations thereof. I knew him a little personally (in a virtual way) from his time devoted to brightening up the Crane Pool Forum and a little more from brand-name social media. He was an upbeat, offbeat presence on every platform he inhabited. Spreading Metsian joy through an aggressively goofy illustrative prism was his implicit mission, and he fulfilled it continually.

I’ll share three quick examples of what made Warren Warren and what made us all better off for having crossed paths with him and his work.

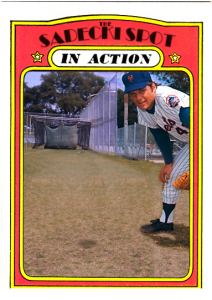

The pitcher is Tom, but the grass was all about Ray. 1) The Sadecki Spot This started as a Crane Pool conceit based on the fact that so many Spring Training pictures where the Mets trained in St. Pete were taken on this one particular patch of grass at Huggins-Stengel Field. It got nicknamed the Sadecki Spot for the Met who was noticed posing there frequently, southpaw hurler Ray Sadecki. It’s the sort of thing that’s fun to talk about on a board for a few posts until the next prospective team president is named by the next prospective team owner. But in the imagination of Zvon, it became a trip.

Zvon never missed a chance to spread Metsian joy. 2) Bob Murphy Does Pre-Game Interviews! One 1970 Topps N.L. Playoff Game 3 card would never be enough for Zvon because shallow dives were never deep enough for his uniquely Sheaded tastes. Warren regularly delved into the Mets fan subconscious and created “Fantazy” cards that we only dreamed of (and we’ve all had dreams like this). Perhaps my favorite within his many, many sets was Murph wielding a microphone, ostensibly on the day the Mets clinched their first pennant, because, of course, Bob Murphy talking to Henry Aaron and Tom Seaver is as much of a part of the 1969 playoff experience as anything. This one, by the way, was included on an SNY telecast last year, probably searched for and selected by a production person who had no idea they didn’t design cards like that in real life in 1970 — and still don’t.

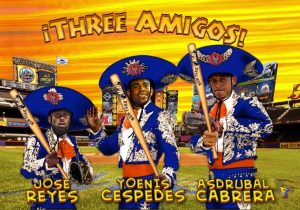

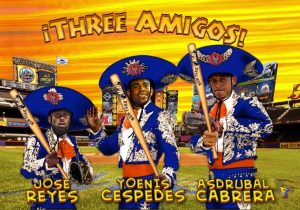

Warren could get pretty cinematic if you asked. 3) iThree Amigos! This wasn’t a card. It was a request, by me. In September of 2016, with the Mets driving hard toward a Wild Card berth, media coverage focused on the role Yoenis Cespedes, Jose Reyes and Asdrubal Cabrera had taken in leading the Mets’ charge, both in firing up their teammates and sparking the offense. It all came together on September 22, the night Reyes homered to tie the Phillies at 6 in the ninth and Cabrera homered to beat them, 9-8, in the eleventh. I reached out to Zvon and told him what this made me think of, did he think he could retrofit the characters from the movie Three Amigos to match the Met moment? He responded cheerfully and brilliantly, per usual.

This is iceberg-tip stuff. I urge you to visit Warren’s blog, Mets Fantasy Cards, and treat yourself to a long, luxurious traipse through his archives. Also, check out his Twitter feed, @zvon714, for examples of how he responded to Met events in the wake of their occurrence, right up through Opening Day this year. He was a chronicler of our team as much as any of us who write and he was an artist like no other.

I was an admirer. My partner here was his peer in the baseball card-conceiving realm. Jason adds his perspective on all Warren could do from a technical (and personal) standpoint:

Warren and I shared a mildly insane passion for making custom baseball cards, and he was my mentor and tutor from the beginning. He was an enormously capable designer and colorizer, and as I learned those crafts, i realized just how impressive his skills were. Colorizations are devilishly hard to make convincing, but Warren’s were always warm and lifelike, because he approached them with such great care and invested enormous hours of work to get them right. He had a bone-deep love of old Topps designs and practices, but he was never afraid to tweak a classic, giving those nostalgic designs jolts of life by breaking borders or turning World Series highlight cards into frames for mini-movies. Most of all, he was generous with not just tips and tricks but also with praise and kind words. He taught me so much, and my inbox is filled with conversations in which we happily geek out about new photo discoveries or puzzle over lost printing techniques. And of course he loved everything about the Mets, celebrating not only their brightest stars but also their three-quarters-forgotten 25th men from generations past. I miss him already.

Again, do yourself a favor and visit Mets Fantasy Cards now and often to dig all Warren Fottrell could do.

by Greg Prince on 24 September 2020 12:08 pm We want people to be able to watch sports, to the extent that people are still staying home. It gives people something to do. It’s a return to normalcy.

—Gov. Andrew Cuomo, May 24, 2020

On Sunday afternoon, August 7, 1994, the Mets lost to the Marlins, 2-0, at Shea Stadium. Had I known the outcome in advance, I wouldn’t have wanted to have been there to witness it. But bereft of inside dope, I sort of did want to be on hand because the deadline the Players Association set for a strike was later in the week, and absolutely nobody was optimistic that a work stoppage could be avoided. The Mets were going on the road the next day, so this Sunday game was, in all likelihood, the final opportunity to go see the Mets for quite a while. I mused out loud that morning that maybe I should get on a train and head out to Shea.

“Why don’t you?” my wife asked.

“I’m tired,” I said.

That’s my excuse for lots of things, though this particular invocation of my most reliable alibi came from a place of earned weariness. We had just three days earlier returned from a ballpark-laden jaunt to the Midwest: White Sox on Sunday; Brewers on Tuesday night; Cubs on Wednesday afternoon. It was a whirlwind. I couldn’t say I hadn’t had plenty of in-person baseball to see me through the upcoming void. Besides, the Mets were on TV. So, on August 7, 1994, I stayed home and watched what became the final home game of the season.

Last night, Wednesday, September 23, 2020, was the first time in 26 years I could say I did the same thing. In the interim, encompassing the final home games of the regular seasons from 1995 to 2019, I attended every single date at Shea Stadium and Citi Field that fit the description of final home game of the regular season. It became a point of pride with me; if there was one game I was gonna be at, it was that game. Then again, it was never the one game I was gonna be at because there had been plenty of games preceding it. That was the beauty of what I came to call Closing Day before anybody else did. The season was leading me there. We’d been through this thing together, the Mets and me. We were one in April, we were one all summer, and now, on the day or night it was time for us to split off, we’d be one one more time.

Then came 2020, when the Mets and I (and everybody else) kept our distance by necessity and public health mandate. I haven’t been out to Citi Field to see them. Nobody has. Not even the “788,905” version of nobody that counted as the official attendance in 1979. The Mets of 2020 have been, by design of contingency, a television show. Not a great one in substance, but a steady one since July 24 — and always presented entertainingly. Same for the radio rendition.

Thus, when Closing Night 2020 rolled around, it was just another game to watch at home. None of the emotions attendant to a final visit to the ballpark. None of that sense that this is the last time I’m getting on the LIRR to change at Jamaica for Woodside…this is the last time I’m getting on the 7 to Flushing…this is the last time I stop by my brick, the last time I get felt up by security, the last time somebody hands me a nick-nack, the last time… There were no last times like the last 25 times to be had.

There were the Mets and Rays, in living color, courtesy of SNY and me paying my cable bill. There was Michael Wacha looking kind of promising for a while until the promise broke. There were home runs from Andrés Giménez, who will keep getting better; and Dom Smith, who has gotten marvelous; and Todd Frazier, who’s from New Jersey. There were the Rays being far more able, as Met opponents have generally been, wherever the show is telecast from. The only twist to this episode is Tampa Bay got to pop a little confetti when it was over because by defeating the Mets, 8-5, they had clinched their division, which is in another league, but that’s the 2020 schedule for ya.

The 2020 schedule for the Mets has been brief and unhelpful from a confetti-popping standpoint. Others pop. We don’t. We’re not eliminated, but we will be. We won’t be playing any more home games, but what’s the difference? It’s not like we get to go to any of them.

by Jason Fry on 23 September 2020 12:09 pm So Seth Lugo faced the Phillies last week and let’s just say it didn’t go well.

Lugo got strafed. He started out the game fanning Andrew McCutchen, but then gave up back-to-back-to-back homers, also yielding a triple and a run-scoring single in the inning while fanning two more. Can you strike out the side and have a horrible inning? Yes you can. Things went no better in the second: flyout, lineout, home run (that landed on Mars), double, hit by pitch, single, early shower.

It was a stunning sequence of futility, and doubly stunning because it happened to Lugo, who has a terrific arsenal and the brainpower to know how to make the most use of it. But that night he looked essentially unarmed: He was missing several MPH off his fastball, his location was poor, and the Phillie hitters were on seemingly everything he threw. My fear, as he made his early departure, was that he was hurt — which wouldn’t have been a shock, given the elbow damage he’s pitched with for some time, but also would have been more bad starting-pitcher news for a team that can’t afford any more going into 2021.

So I sat down Tuesday night with some trepidation. Would Lugo continue to look like a guy who couldn’t wake up from a nightmare? Could he fix whatever was ailing him against the Rays, a thoroughly impressive team whose players make very few mistakes and always seem to have a plan?

Happily, Lugo looked like the Lugo we’ve foolishly come to take pretty much for granted. The oomph on the fastball was still mostly missing, which may simply be the cost of moving from the bullpen to the starting rotation, but everything else was working. Including, perhaps, a tweak that mostly was left out of conversations: The chatter in the SNY booth (on an entertainingly pointed and perky night for Gary, Keith and Ron) was that Lugo may have been tipping his pitches in Philadelphia.

Meanwhile, Tampa Bay’s Blake Snell got a little squeezed by the umpire (and complained about it a lot) and a little unlucky, which was enough to make him the loser. Robinson Cano — who’s had a wonderful year and done so much to wash away the murk and muck of his first campaign — started the Mets off with a solo homer, and then Pete Alonso got into the act with a fourth-inning homer of his own. Alonso brought in two more runs later in the game and looked like he was actually enjoying playing baseball for once. The batting average isn’t there and the fielding has slipped — in fact, the Polar Bear has looked a lot more like the feast-or-famine guy scouting reports warned we’d get in 2019 than the Rookie of the Year we so thoroughly enjoyed — but we should recall that Alonso’s still working on what would be a 37-homer season in a full campaign. That will play; throw in some more smiles from the BABIP gods and it will play very nicely.

(Oh, and the heretofore anonymous Guillermo Heredia — whose first name I still can’t remember without asking Google or my wife — went deep, proving that he not only really does exist but might actually be good for something.)

Then there was Todd Frazier. I’ve done a lot of grousing about Frazier’s return from the omniscient vantage point of my couch, which is a stance that’s far from controversial — he’s hitting a robust .212, though there is that 0.00 ERA — but admittedly has been amplified by my own prejudices. I’ve always been inclined to favor young players with theoretically bright futures over aging veterans with long, mostly complete tenures, and I’ve been an enormous fan of Luis Guillorme‘s throughout his time with the Mets, convinced he’d succeed if granted regular playing time. So I felt a little guilty when Frazier started a nifty double play in the sixth, short-circuiting a dangerous situation for the Mets. I started to grumble that Guillorme would have made the play too, then chided myself for crossing the line between prejudice and absurdity.

Shortly thereafter, Frazier had a chance for another DP and promptly muffed it. Sometimes baseball forces you to reexamine your own blind spots and biases, and sometimes, well, it shamelessly enables them. FREE LUIS GUILLORME!

|

|