The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 5 September 2020 12:19 pm It’s a point that arrives in every season. The game where…

…your head and heart aren’t really in it.

…you have a feeling that comeback you’re dreaming of is going to remain just a dream.

…the loss, when it comes, feels both foreordained and like a herald of more to come.

Turns out that point arrives in shortened little improv seasons too.

The Mets lost to the Phillies on Friday night, 5-3. Rick Porcello, who’s pretty much been terrible all season, pitched quite well. Everything I just wrote about Porcello could also be written about his opponent, Jake Arrieta. If there was any novelty to this game, it was the sight of two former Cy Young Award winners reduced to whittling away at their sky-high ERAs, like finding a pair of rich-guy sports cars under the rotted-out, flapping remnants of tarps in the corner of some particularly motley junkyard.

Jared Hughes surrendered the go-ahead run on a sharp little grounder by Roman Quinn off the hand of a diving Andres Gimenez — not an error but one of those plays you’d like to see made that wasn’t. Another run came in on a throw Dom Smith couldn’t handle at first. Brad Brach hit a batter with the bases loaded. Michael Conforto hit a two-run homer, continuing his remarkable season, but the Mets’ chances evaporated in the eighth, when Rhys Hoskins dove to snag a line drive off the bat of Robinson Cano that was ticketed for the right-field corner. The Mets were down two with runners on first and second and one out when Hoskins made the play; instead of being down one with a gimme run on third, they were in the same situation with two out. That play, for all intents and purposes, was the ballgame.

Afterwards, Luis Rojas told the media via Zoom that “there’s some mistakes we have got to minimize in the amount of games we have left. We have 21 games left. We are not thinking time is running out or anything like that, but we do have to play clean baseball. We have to play good baseball.”

Managers are paid to say obvious, vaguely dopey things after losses like this one. Often, they don’t really believe those things and nobody who knows the game and the media rituals around it expects them to. But yes, time is running out. Yes, the Mets are definitely thinking that and some associated things like it. Yes, the Mets have to play clean/good baseball. But for most of this curtailed season they haven’t done that, and there’s nothing obvious to make you think that’s about to change.

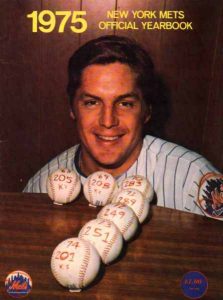

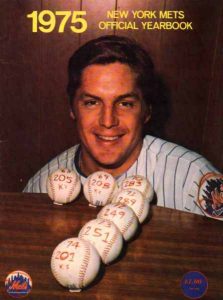

by Greg Prince on 4 September 2020 3:05 pm Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

For me, baseball provides constant challenge, a new mental and physical test every game.

For me, baseball also provides tremendous satisfaction, a realization that all the work and dedication and concentration I’ve put into the game since I was a youngster haven’t been wasted.

—Tom Seaver, with Dick Schaap

It was very important in the summer of 1971 that when I was assigned to a Long Beach Recreation Center Pee Wee League baseball team that I got to wear 41. I worried that because of my late registration (our family tended to be late for everything) that I’d miss out on the plum number because, c’mon, it was 1971 and didn’t every kid want to wear 41? Wasn’t every eight-year-old’s favorite player Tom Seaver?

My conception of organized baseball was formed from watching it on television. There were starters. There were bench players. There was a bullpen. There were uniforms. I did the calculations and assumed that each team would have a minimum of 18 players. One in the field for each position. One on the bench to back up at each position. One to be ready in the bullpen in case the starting pitcher faltered. I could see myself in my spiffy uniform, No. 41, warming up in the bullpen. I knew Pee Wee League wasn’t the big leagues, but I’d seen enough sitcoms to notice that little leaguers got to wear uniforms like just like the big leaguers. If Greg Brady was wearing a real baseball uniform, why wouldn’t Greg Prince?

Ah, but Greg Brady and all those Hollywood scriptwriters didn’t know from the operations of the Long Beach Recreation Center Pee Wee League. There was no bullpen. There weren’t as many as 18 players per team. There were however many as signed up and if a kid didn’t start one day, he’d have to start the next day. Nobody could be a “sub” more than one game in a row, at least according to the rules. As for uniforms, there were no pants. I mean, yeah, we wore pants, but nothing regulation. All we got to identify us as members of a particular team was a t-shirt and perhaps a cap. I say “perhaps,” because they were out of my team’s caps by the time I was registered and taken to Mister Sports. Mister Sports had the shirts. Mister Sports was the official t-shirt supplier of the Rec League. I don’t know who else would have been in Long Beach.

I was an Ace. I could have been a Comet, a Leopard, a Lion or one of two other things that were team names I forget, but they put me on the team with green t-shirts, which was fine as far as it went. I liked green. The A’s of Vida Blue wore green. Mister Sports — or the man I assume was the proprietor of Mister Sports but had a different last name — asked if I wanted a number on the back.

Yes, I said, bracing for potential disappointment that I couldn’t have the number I wanted. I wanted 41, I said. I doubt I had to explain its significance to a man known as Sport in 1971

Mister Sports handed my mother a white felt “4” and a white felt “1” and was instructed where to sew them on. Mister Sports wasn’t full-service. Numbers were extra to begin with. Two were more than one, but I had to be 41. Mom, who didn’t watch a lot of baseball and didn’t do a lot of sewing, nevertheless dipped into her bowl of needles and thread, and made it happen. I looked ready to play for the Aces. I would be representing an ace among Aces.

I was No. 41.

My No. 41 is no longer in stock. I hope Tom’s will do. In 1971, I was in my third season as a Mets fan, my second full season. Late summer 1969 was my entrée. What a way to begin. 1970 was the real thing, a full campaign, Spring Training to the World Series, the latter of which proceeded without the participation of the Mets, unlike 1969. I grasped my favorite team couldn’t win every year. I grasped less gracefully, by the time 1970 was over, that my favorite player, Tom Seaver, couldn’t win every start. Or he could but sometimes didn’t. Sometimes the Mets didn’t score enough for him. Sometimes, somehow, he’d give up a run or two too many. He had gone 25-7 in 1969 and seemed to be en route to something similar in 1970. But he stalled in August. Tom won only 18 games despite leading the National League in both strikeouts and earned run average. The Mets won only 83 games despite having Tom Seaver.

Two years, two sets of results, one that enthralled me, one that I accepted somewhat reluctantly. But by then, I was in for life. I didn’t know it, given that life wasn’t yet eight full years, but I could have guessed. Why would I stop loving the Mets or Tom Seaver?

The 1971 Mets were a lot more like the 1970 Mets than the 1969 Mets. They were OK. For a while they were more than that, dueling the Pirates for first place through June. Then they came down with a terrible case of the blahs. They lost 20 of 29 in July and slipped below .500 for a few days in August. When it came to competitiveness, the Mets of No. 41, Tom Seaver, weren’t doing quite as well as the Aces of No. 41, me.

At no point during the 1971 Pee Wee League season would have the Aces been described as being “of me,” but since I’m the only Ace telling this story, consider them my team. Now, because I’m trying to be a reliable narrator, I will tell you that this No. 41 of the Aces — there were at least a couple more, as nobody was really fussy about number assignments; some kids didn’t even bother with numbers — wasn’t a particularly good baseball player. Or Tee-ball player. That’s what we were playing. I’d never heard of it until I showed up for my first game, after that game had started, at least one game after that season had started. My only previous experience with slightly organized ball was an afterschool program in recently completed second grade. We played all kinds of sports. I was all kinds of not good, but I loved to play. In spring, we played baseball. My mother bought me a glove at TSS. Somebody decided I was a first baseman, probably due to decent height for an eight-year-old. But my glove wasn’t a first baseman’s mitt, so soon I was labeled a third baseman. Less chance to get me and my glove involved in the action.

Come summer and the Aces’ second or later game of the season, I show up with my glove and my No. 41 shirt and no cap and I’m asked what position I play. “Third base,” I say confidently. All right, I’m told, go play third base.

You know that phrase you’ve heard down the corridors of time with the Mets regarding “the third base experiment”? For all those converted first basemen or outfielders who were drafted for third base duty in those “79 men on third” days when nobody could fill the gaping hot corner hole for more than a week, maybe less? “The third base experiment didn’t last very long,” that sort of description?

The third base experiment didn’t last very long with me. I clearly remember a ball getting by me, bouncing past an open chain-link gate and me chasing it onto an adjacent street where men working some kind of road construction kindly pointed me toward my rolling object of desire. I got the ball back into the infield. The batter had rounded the bases by then. The batter might have rounded the bases twice. It took me a while to make the play.

That was the extent of the third base experiment for me on the Aces. Soon I was consigned to “sub” duty half the time and half the time directed to the pitcher’s mound. No. 41 on the mound! It was the stuff of my Channel 9 dreams. Or at least The Brady Bunch. Except in none of that programming did the batters bat off tees, rendering the “pitcher” utterly — and I mean utterly — pointless, save for an occasional grounder up the middle, and even then.

I was wearing 41, just like Tom Seaver. I was the pitcher, just like Tom Seaver. Except I was nothing like Tom Seaver. Tom Seaver looked in for the sign. Tom Seaver went to his windup, hands above his head, his body unfurling with fury, his right knee hitting the dirt, his right hand firing a pitch, probably a strike, to his catcher. Tom Seaver actually got to throw the ball. Tom Seaver wasn’t switched after a couple of games to catcher. In the league where Tom Seaver played, the catcher — Jerry Grote most starts, Duffy Dyer sometimes — kept busy catching. In Tee-ball, the catcher got to wear extra gear and stand (not crouch) behind the plate while the other team’s batter swung at a ball that was not pitched. So except for an inning of experimentation at third, my role as a 1971 Ace was pitcher/catcher/sub.

I was cursed with versatility.

Seaver, on the other hand, was blessed with the right arm that was the envy of his contemporaries. He did more than wear 41. He modeled it for the aspirational youth of the age. By the All-Star break of 1971, even with the Mets crumbling, Seaver stood out. He had ten wins, halfway to the twenty he didn’t get in 1970. He’d been stuck on ten for a couple of weeks. The Mets were no help. Still, you didn’t have an All-Star Game without Tom Seaver. Seaver had been a National Leaguer for five seasons and was making the All-Star team his fifth time. He started in 1970, and the NL won. He wasn’t used in 1971, and the NL lost. There’s a valuable lesson in there.

I loved All-Star teams and All-Star Games. The Rec Center put up a sign that they’d be having one. I saw that it would be Thursday. Hey, Mom, can we go? It meant cutting short her sitting at the beach, which she quite enjoyed, but she agreed. I looked forward to cheering on my teammates who made the All-Stars the way I cheered on Seaver and Bud Harrelson when they were introduced at Tiger Stadium. Except I had read the sign wrong. The game had been last Thursday. The Rec Center’s diamonds were quiet, except for somebody’s mother loudly pointing out her son was something of an idiot.

That interruption of a perfectly lovely beach day had not gone over big with my Pee Wee League mom, and I sure heard about it, but otherwise, she was surprisingly supportive of my venture. On sunny mornings she’d sit in the stands under an umbrella and voice encouragement. “Throw the hat, not the bat” was her chant, conceived to teach me to stop throwing the bat if I managed to hit the ball off a tee. You were called out for throwing the bat. The communal helmet they didn’t seem to think posed as much of a danger. (Also, we all shared one batting helmet, which I don’t want to think about too much.) She suggested to our best player that he could help his well-meaning teammate, No. 41 here, improve if he played a little catch with him, over there, where they’re building the skating rink, when the Aces weren’t in the field and neither of us was batting. To my surprise, the best player on the team became my warmup partner.

The Aces were actually pretty good, my sporadic contributions notwithstanding. Once karma smiled on me and allowed me the kind of trip around the bases some kid enjoyed at my expense when a ball with which I made contact mysteriously slipped away from another eight-year-old and then some. I didn’t have the perspective to appreciate just what unsure bets eight-year-old glovemen were. I counted it as one of the 35 home runs I hit in 1971. Thirty-four were in my backyard, alone.

I would’ve preferred to play more for the Aces — and not strap on a chest protector, a mask and purpose-free shin guards when I did — but I had some nice conversations on the bench. When not chatting, I tried to be a holler guy. One time I hollered at the coach when he attempted to convince me that “for the good of the team” I should allow him to waive the league rules and sit for a second consecutive game. Every kid had to play at least every other game. I wasn’t putting up with his illegal roster management. Neither was my mother. She got a big kick out of me pointing out to the coach that while other players, like myself, were rotated on and off the bench, his son always started, always played center and always batted leadoff. I think I wanted to add “…and your son isn’t really that great,” but I wanted to maintain my status as a good teammate.

My fellow substitutes appreciated my speaking up on behalf of the forgotten children. I wonder if the pitchers Gil Hodges reflexively skipped over so Tom Seaver could always pitch when his turn came up were any more understanding of their slights than I was of mine. I doubt any of them raised their voice to Gil. Then again, nobody on our team, whatever our level of success in 1971, was a budding Tom Seaver.

Four teams made the Pee Wee League playoffs, ours included. The Aces beat the Comets in the semis; somebody’s mom took the team to Jahn’s for ice cream. We earned the right to face the Lions in the finals. They had defeated the Leopards. I was a designated bench guy for the championship game. I didn’t argue. One of the other subs brought a bottle of lemon-lime soda from the nearby A&P. Green bottle, to match our t-shirts. We passed it back and forth and took swigs, just like we shared a batting helmet. I was hoping we were going to save some to douse each other in victory, same as Tom Seaver and his teammates did with champagne when they clinched every championship they won in 1969. It would be sticky, I figured, but it would be worth it.

Turned out we didn’t need to save any A&P Lemon-Lime Soda for a postgame celebration. We lost to the Lions. I don’t recall the score. I don’t recall terrible disappointment. I was a Mets fan. I knew you couldn’t emerge as champions every season. Being pretty good was good enough sometimes. I also knew my mother was inviting the team to Gino’s for consolation pizza, which was terrific.

***It was very important in the summer of 1971 that when my mother and I wandered into a bookstore at Roosevelt Field and I picked up a paperback book with my favorite player on the cover that I have it. The Perfect Game: Tom Seaver and the Mets it was called, “by Tom Seaver with Dick Schaap”. The Dick Schaap part was in smaller letters. I knew Schaap from doing the sports on Channel 4. I didn’t know he wrote, too. I didn’t know Seaver wrote at all, but how surprising could that be? To me, Tom Seaver could do it all.

The cover promised “The marvelous story of the team that couldn’t win, the pitcher who wouldn’t lose, and The Perfect Game”. Plus it was “Fully illustrated!” All that for 95 cents. I don’t think I had to ask Mom too hard.

Reading about Tom Seaver is fundamental. I owned a few sports books by the time I was eight, but this was the first one completely devoted to the Mets, or to a Met. It was about both Seaver and his team. A lot more about Seaver, given the authoring arrangement. As I dug in, I contemplated how the process worked. Did Schaap come over to Seaver’s house? Probably. Seaver’s house looked like my house in my mind because mine was the only house I knew well. They probably sat in the dining room, situated where our dining room was, Seaver talking, Schaap taking notes, Nancy — I already knew from Nancy Seaver — coming in courteously asking if anybody wanted coffee.

However Seaver and Schaap pulled it off, they told a story that mesmerized me. They told me about Tom being from Fresno. Tom going to USC. Tom joining the Marines. Tom pitching for the Alaska Goldpanners. Tom being drafted by the Atlanta Braves, then being told not so fast there, Tom because the college season had already started and USC’s own Tom Seaver was still on campus.

They told me about a hat and a lottery and a slip of paper that said New York Mets, which was where the chronology got really good, because it meant Seaver would pitch for us. First, a year in Jacksonville, rooming with Wilbur Huckle. Then 1967, his rookie season, his All-Star season, his Rookie of the Year season, followed by 1968, when making the All-Star team became a way of Tom’s life.

Then 1969, which was the whole reason there was a book by and about Tom Seaver. Up to the day I brought The Perfect Game home, I remembered a few highlights personally from when I was six and had picked up some more from studying baseball cards, listening to Ralph Kiner, Bob Murphy and Lindsey Nelson and watching (as the short preceding The Out of Towners at the Laurel Theater) Look Who’s No. 1 when I was seven. Now, at eight, I was getting the inside dope from the main man, from No. 41 himself. I got to learn about how he couldn’t get a decent breakfast before he started the first game of the World Series — the hotel coffee shop was crazy busy in Baltimore — so he had to grab a roast beef on white with mayo. It apparently wasn’t nourishing enough because he gave up a leadoff homer to Don Buford and lost Game One.

The Perfect Game was organized around Game Four. That was the title game. I thought it would be about that perfect game he didn’t quite get versus the Cubs on July 9, 1969, the one Jimmy Qualls broke up in the ninth inning. No, it was Game Four. It was more perfect to Seaver because he was trying to win a championship. The Mets were up two games to one in the Series. He was disappointed in that first start. He was going to make up for it, even if it took ten innings.

Which it did. Tom Seaver went the distance, beating the Orioles, 2-1. Gil didn’t take him out until his turn to bat came up in the tenth. J.C. Martin pinch-hit for him and bunted. Running fortuitously in a baseline of his own creation, Martin’s wrist deflected Pete Richert’s throw to first. Pinch-runner Rod Gaspar scored from second. Hodges didn’t make his subs sit very long.

That night, Tom Seaver celebrated his first World Series victory at Lum’s, a Chinese restaurant on Northern Boulevard, near where he and Nancy lived in Flushing. Mr. Lum (presumably no relation to Mr. Sport) told the Seavers he thought that by the time the Mets were in the World Series that his beard would be down to the floor.

Mr. Lum, Seaver and Schaap pointed out, didn’t have a beard at all.

I consumed what Tom ate, what Tom breathed, what Tom thought, what Tom did. I read The Perfect Game and then I read it again. I was so proprietary of its facts and figures (it was fully illustrated with statistics) that when my sister gave me a rubber stamp and ink pad with my name, I stamped GREG all over the back and side of the book.

TOM had already imprinted his name on my brain. For years, any book I saw that was “by” Seaver or about Seaver was one I had to have, even when the price rose above a dollar. Same for books about the rest of the Mets. All I wanted to do was read about my favorite player and my favorite team. Maybe someday I’d write about them.

***It was very important to me in the summer of 1971, especially as summer slid into fall, that when the Mets’ season was over, it end with Tom Seaver winning 20 games. The Mets’ season would be over on September 30, a Thursday night at Shea Stadium versus St. Louis. I knew their season wouldn’t extend into the playoffs. The Cardinals had surpassed the Mets for second place, and the Pirates had run away with the NL East. I’d be happy if the Mets could finish no lower than third. I’d be ecstatic if Seaver was a 20-game winner.

How could he not be? Something went awry last year, 1970. Tom was 16-5 at one point, 17-6 a little thereafter. Then he stopped winning games. It bothered me the whole offseason. The Cy Young voters didn’t care that his ERA was lowest in the league (even if it was kind of high for a league leader, at 2.82) or that his strikeouts were the most (283, more than any righty in NL history). They honored Bob Gibson instead. Tom finished seventh. Seventh! Pitchers with earned run averages over three (three!) finished higher. But most of them had won 20 or more games. That was the Cy Young standard. I knew Tom Seaver was the best pitcher going. But one number would speak loudest on his behalf.

Twenty wins in 1971 was both a badge of honor and not altogether inaccessible. Fourteen different pitchers were on their way to a record of 20 and something. Most dazzling in his pursuit of the dynamic digits was Vida Blue of the Oakland A’s. When I wasn’t focused on Seaver and the Mets, I was taken by Blue and the A’s. They wore green, just like the Aces. Blue piled up wins out of the gate in 1971 like Seaver had in 1970. Vida was 6-1 by the end of April, 10-2 at the close of May, 16-3 when June concluded. Even slowing down a little, he was fantastic, notching his 20th win on August 7. Vida Blue was a revelation.

Yet he didn’t lead the American League in wins. Vida finished 24-8. Mickey Lolich of the Tigers came on like gangbusters (you learn a lot of terms when you’re eight and paying attention to sports) and finished 25-14. Lolich, a lefty like Blue, pitched a lot. A lot. Vida started 39 games and completed 24. Mickey started 45 and completed 29. These would have been crazy totals to me had I had much context, but I was in my third season of watching baseball, my second full season. This is what aces when they went out to pitch.

The Orioles had four aces, or, more precisely, four 20-game winners. Nobody really thought of Pat Dobson as an ace, yet Baltimore’s fourth starter won 20 games, as many as Mike Cuellar and Jim Palmer, one fewer than Dave McNally. Cuellar and McNally had won a Cy Young previously. Palmer had a few in his future. Yet they were essentially footnotes behind Blue and Lolich — and Lolich only pulled himself into the Blue-tinged conversation by pitching what seemed like every third day.

Blue’s teammate Catfish Hunter won 21 games. Lolich’s teammate Joe Coleman won 20 games. A White Sox knuckleballer named Wilbur Wood won 22. Andy Messersmith won 20 for the California Angels. The American League was lousy with 20-game winners. For what it was worth, Hunter was a pretty good hitter as well.

I followed the AL leaders because they played baseball, too, but the NL is what really mattered to me. The NL — or senior circuit, as it was sometimes called in the papers — was a little more choosy. Al Downing, who’d been around a while with limited distinction, suddenly won 20 for the Dodgers. Steve Carlton, who I knew mostly from the story about him striking out 19 Mets yet losing that game when Ron Swoboda homered off him twice (the Mets had since traded Swoboda — comprehending that a 1969 Met hero could be traded was tough when I was eight), won 20 for the Cardinals. Gibson was absent from the list this year, but another perennial 20-game winner, Ferguson Jenkins of the Cubs, was accumulating a couple of dozen victories for a Chicago team no less so-so than ours in New York. Jenkins would wind up with 24 wins. He’d also lose 13 and complete 30. Leo Durocher was not shy about pushing his starters.

Gil Hodges was more careful with Tom Seaver. In 1970, he started his ace on three days’ rest a few too many times for comfort. It didn’t work. Back to the five-man rotation Gil and pitching coach Rube Walker had fashioned to bring the Mets to prominence. Tom would get four days of rest as a rule. Sometimes it rained and somebody would sit so Tom didn’t have to idle. Hopefully those non-Seaver Met pitchers were of good cheer rooting on Tom.

As of July 17, in his first start after the All-Star Game, Tom Seaver sported as good a non-Blue ERA as you could ask for from an ace pitcher in 1971 or, really, any year: 2.32. But his won-lost record, the first and sometimes only thing busy baseball writers examined when evaluating who was good, who was great and who was the best when deciding who’d win an award, was 10-7. The seventh loss came when Seaver pitched into the ninth at the Astrodome. He’d given up one run on four hits over eight innings, walking nobody and striking out ten. The score was 1-1 despite his best efforts. In the ninth, Roger Metzger led off by singling, Joe Morgan bunted him to second and Jim Wynn, a.k.a. the Toy Cannon, was issued an intentional walk. Gil told Tom to go after the promising Houston center fielder, Cesar Cedeño instead. Cedeño, all of 20 years old, beat savvy 26-year-old Tom with a single that scored Metzger.

Tom Seaver made it to his 1972 card a two-time 20-game winner. The card has survived with me 48 years. That was the kind of outing Tom Seaver would lose for the 1971 Mets. He’d go eight, strike out eight and lose, 3-1. Or he’d go nine, strike out ten and be no-decisioned despite giving up no runs. Pitching into the tenth inning didn’t necessarily get him a win. What would become identified down the line as “quality starts” didn’t by any means guarantee him a W.

In early August, with Seaver’s record at 11-8 and his ERA at 2.26, Jack Lang, one of the beat reporters who’d tracked Tom since Tom was a rookie, made the kind of pronouncement that made a certain kind of sense in the year of Blue and Lolich and Jenkins:

“One thing is clear. It is not Tom Seaver’s year.”

Perhaps Tom Seaver took inspiration from Lang’s appraisal, because when his next start came around, 1971 very much became Tom Seaver’s year. Even the Mets must’ve been reading, because they scored nine runs on his behalf; the Mets won, 9-1, with Seaver going all the way. He was now 12-8.

Tom followed up with another ten brilliant innings (0 R, 14 SO)…and a no-decision in San Diego. But it was too late to turn back now. The pitcher who crushed the 20-win mark in 1969 and fell short of it in 1970 was on a mission. A shutout over the Dodgers raised Tom’s mark to 13-8. Three consecutive complete-game triumphs in his next three starts boosted him to 16-8. Then, not just a complete game, but a shutout over the Expos. 17-8. Nine more innings, another win, this times versus the Philies. 18-8 on September 11.

Then, frustration. A 1-0 loss to the Cubs, with the only run scored when opposing starter Juan Pizarro homered in the eighth. Tom would be outpitched by a Cub again, this time rookie Burt Hooton. Seaver’s ERA was down to 1.81. His “record,” the only figure anybody referred to as a pitcher’s signature, was 18-10. Eight games remained in the season. Under usual circumstances, Seaver would have but one start left.

On September 26, Tom took on the division champion Pirates at Shea. Perhaps he was moonlighting with the grounds crew, because Seaver was mowing down every Buc batter he faced. Three up, three down in the first; three up, three down in the second; three up, three down in the third.

Tom Seaver was pitching a perfect game against the Pittsburgh Pirates. Roberto Clemente had the day off, but Danny Murtaugh had started several of his dangerous-hitting regulars: Willie Stargell, Al Oliver, Bob Robertson, Dave Cash. Seaver was setting down every Pirate he saw. The strikeouts were piling up. He had fanned ten in the first six innings. Win No. 19 was in sight, and it might come on the wings of the first no-hitter in Mets history…the first perfect game in Mets history.

This might call for another book!

Those particular literary wings were clipped as soon as the seventh got underway. Cash walked to end the bid for perfection. Then Vic Davalillo, playing in place of Clemente, stroked a clean single to center that chased Cash to third. There went the no-hitter. Oliver’s run-scoring fly ball to center spoiled the shutout, too. Now there was the matter of holding onto the lead. A runner was on, only one was out and Stargell, who already had 47 home runs (and had been clobbering the Mets literally since the day Shea opened), was up next.

Tom opted for a sinking fastball. His desire was to get Wilver to pound one into the ground and set up an inning-ending double play. True to the way Seaver planned and executed his pitching over the last two months of 1971, that’s precisely what happened: 1-6-3, Seaver to Harrelson to Donn Clendenon.

“That’s exactly what I was trying to do,” Seaver said after the game. “I know that sounds egocentric, but that’s damn good pitching.”

Tom and the Mets stayed ahead. And Seaver returned to flawlessness thereafter. He retired the final six batters to win his nineteenth, 3-1. His only blemishes were that walk to Cash and that single to Davalillo. Because of the DP, he wound up facing just one batter over the minimum.

But he was still one victory under the minimum for what was universally accepted as part and parcel of the definition of greatness…even though nobody was arguing Seaver wasn’t as great a pitcher as could be found. None of us who had grown to love him, though, would be fully satisfied if Tom didn’t get his greatness statistically certified. Tom certainly wouldn’t be. The Mets’ middling ways’ notwithstanding, Tom was not the type to accept pretty good as good enough. Not even very, very good would do it. Thus, three days of rest was not too few for Hodges to give him the ball one more time. It’s not like there were playoffs for which to save him. It’s hard to believe Seaver had to prove anything to anybody by the final game of 1971, but Tom Seaver was the toughest audience Tom Seaver had.

“The numbers come close to saying, yes, George Thomas Seaver is the best pitcher in baseball,” Vic Ziegel wrote as the Mets’ season otherwise limped to its conclusion. “There is, Seaver understands, only one more number he must add to the list.” No. 20 loomed large in the public imagination where No. 41 was concerned.

Unlike Game Four of the 1969 World Series, there was virtually nothing on the line for the Mets as a team in Game 162 of 1971. A piece of third place remained available, and nobody would mind the few extra bucks that would net each Met, but really, this was about Tom Seaver winning a game for Tom Seaver. And for me, at eight, or any age, that was all I needed to hear. You root for the whole team, you root just a little harder for your favorite player. Single-mindedness is what lifts a competitor above his peers, and Seaver’s drive elevated him to a plane where he had few, maybe no peers. (It also elevated the Mets to a World Championship two years earlier, when nobody outside of Baltimore seemed to mind how badly he wanted to win.) Of course Seaver wanted to pitch the final game of the year. Of course Gil Hodges would let him. And of course he’d win it, attaining No. 20 in a brilliant complete game stifling of the Cardinals, 6-1, striking out 13 Redbirds along the way.

I watched that game and I celebrated the last out. Not with anybody and not with lemon-lime soda, but savoring delicious confirmation that nobody could say Tom Seaver wasn’t a 20-game winner and nobody who looked at all of the other numbers — a 1.76 ERA that was lower than everybody’s in the majors, including Blue’s; 289 strikeouts, breaking his own senior circuit righty mark — could possibly say Seaver wasn’t the best at what he did. Make room in the man’s trophy case. A second Cy is surely on its way!

Ah, they gave it to Jenkins. Whatever. I knew Tom Seaver was the best in 1971. I knew it before 1971. I’ve known it ever since. That’s the very important thing.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1965: Ron Swoboda

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1967: Al Schmelz

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1986: Keith Hernandez

1988: Gary Carter

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2007: Jose Reyes

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2010: Ike Davis

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2019: Dom Smith

by Jason Fry on 4 September 2020 12:06 am The Mets were supposed to be off Thursday, which would have been fitting given the sad news Wednesday night that Tom Seaver — No. 41, the Franchise, the most essential and irreplaceable figure in team history — had died Monday at 75. Thursday would have been a day to mourn and reflect on the memory and legacy of player and man alike, a day appropriately empty of anything else.

But it was not to be — not with COVID forcing a makeup game against the Yankees — the same Yankees who, hollowed out by injuries as they are, yanked the Mets’ momentum to a halt last weekend and put a hole below the waterline of their season. Was this really necessary? Yes, it was, and so out they went to Citi Field, with Seaver’s retired No. 41 looking down on them from atop the stadium.

Before the hostilities commenced, the Mets remembered their ace with grace, holding a moment of silence, hanging a 41 uniform in the dugout, tipping their caps to his number and — in a truly inspired touch — adorning their right knees with dirt in imitation of Seaver’s drop-and-drive mechanics. (Seriously, I’d like to know who came up with that — it’s worthy of a genius grant.)

And then they went out to play the Yankees and for some time I was grimly certain that my post would be an elaboration on “they did everything right and then blew it by playing baseball.”

Robert Gsellman took the mound without his breaking stuff and got knocked around, departing before the second inning was done after surrendering four runs. The Mets clawed back, however, and against J.A. Happ, no less — he’d looked untouchable in their last meeting (also against Gsellman) but was decidedly mortal this time. Recidivist Met Todd Frazier started the comeback with a home run, with a Jake Marisnick double and singles from Amed Rosario and Jeff McNeil evening the score. Meanwhile, the bullpen held the line valiantly, at least until Miguel Castro proved shaky in the seventh, allowing a pair of two-out hits that created a two-run deficit. (On Wednesday afternoon I was in a kayak on the East River, so I heard Castro pitch but didn’t see him; my conclusion after actually viewing him is that someone should buy him a cheeseburger.)

The last hit against Castro could have just as easily been called an error on Pete Alonso, as he was in position to field it but watched it scoot under his glove and go down the right-field line. It’s been a miserable season for Alonso both at the plate and in the field — in fact, it’s pretty much been the season we were warned to expect in 2019, with homers punctuating stretches with far too many strikeouts and shaky defense at first. Frazier’s reacquisition, I’m half-convinced, was less about getting a bat to employ against lefties than about giving the Polar Bear a cheerful veteran voice that might lift him out of his sophomore doldrums.

Justin Wilson — so reliable last year, not so much now — gave up another run and things looked truly dire. But the Mets, once again, fought back. A Rosario single brought them within a run, they survived letting Edwin Diaz anywhere near the ninth, and then watched as McNeil led off the bottom of the inning with a walk off Aroldis Chapman.

Enter Billy Hamilton, who took second on a balk, promptly tried to steal third and was gunned down while J.D. Davis stood there glumly watching. Seriously? Hamilton seems like a good teammate, and it isn’t his fault he can’t hit — major-league baseball is full of at least marginally useful players who couldn’t hit. But he also seems to have no feel for the game — that was a moment for patience, for seeing if Davis could move the runner in any number of ways, or at least to size up Chapman and choose the ideal pitch to make a break on a soggy track. Instead, Hamilton removed himself from the equation.

So of course Davis hit the next pitch — an 0-2 pitch, nonetheless — over the center-field fence. I never recall being angry about a game-tying homer in the ninth before, but somehow I was this time, because it should have been yet another walkoff against Chapman, and administered by the guy he’d recently nailed in the hip, no less.

The Mets sent Diaz back out for the 10th, survived that with a little help from automatic runner Tyler Wade, who somehow thought a humpbacked liner to Michael Conforto would drop in, and sent Dom Smith to second as their own automatic runner. I prepared myself for a long and futile siege or some other imminent embarrassment, but Alonso hit Albert Abreu‘s second pitch over the left-field fence, one of those drives that’s immediately and obviously gone before the bat is dropped. Alonso floated around the bases to celebrate his first career walkoff homer (a leadoff two-run shot, because 2020), and despite fits and starts and their own missteps, the Mets had ended the day with their heads held high.

* * *

In remembering Tom Seaver, you should of course start with my blog partner, who was on the case yesterday. I’ll limit myself to a couple of words and links. First off, a tip of the cap to Mets owner-in-waiting Steve Cohen, whose tribute to Seaver was a welcome departure from the usual PR-massaged vagaries. This is a fan talking, with humorous rue and real feeling, and while none of us knows anything substantive about Cohen yet, it’s a pretty good first impression.

I also highly recommend this Tom Verducci article on Seaver in his twilight — it’s a wonderful story, shifting ably between his glorious youth and a visit to Calistoga, Calif., by his Miracle Met teammates late in his life. Beautiful, heartbreaking and awfully close to definitive. And don’t miss this tweet, from Keith Olbermann, about Seaver’s place in history. You may be speechless too.

One of my favorite Seaver stories gets to the heart of how competitive and cerebral he was: One day, the Mets were playing the Pirates in the rain, Manny Sanguillen was at the plate, and Seaver was taking an inordinate amount of time between pitches. A wet and puzzled Jerry Grote finally went out to the mound to ask his pitcher what was taking so long. Seaver’s response? He was watching the water pool on the bill of Sanguillen’s helmet, and waiting to start his delivery until the water was ready to form a droplet that would hang and quiver right in Sanguillen’s view. Who notices that in the first place? Who then decides to leverage it for an extra bit of advantage? Tom Seaver, of course.

But there are so many such stories — Seaver and Bob Gibson trading HBPs during a testy spring-training game, his contempt at the idea of celebrating a .500 record, the 1978 day where he reported for duty with his fastball MIA and so out-thought the Cardinals all the way to his lone career no-hitter. Seaver’s death wasn’t a surprise, exactly — we’d known of his retreat from public life, his mind cruelly plundered by dementia — and yet it still seems impossible. How can the New York Mets still exist without Tom Seaver in the world? No nickname was ever more perfect than The Franchise. He was that and still is and always will be.

by Greg Prince on 2 September 2020 9:56 pm Terrific only began to say it.

Tom Seaver was everything to the New York Mets. Everything. He was everything to me. Everything. And I know I’m not alone in that assessment.

Seaver’s death Monday at the age of 75 was announced tonight shortly after the current Mets’ win at Baltimore. I watched that game, as I watch practically every game, probably because I watched the Mets play their way to Baltimore and the World Series 51 years ago next month. The Mets played their way to Baltimore in October of 1969, taking on and taking down the mighty Orioles, in large part because they had the good sense to ask the commissioner of baseball to write their name on a slip of paper and stick it in a hat in the spring of 1966. The Mets’ name emerged. The perennially bottom-scraping Mets didn’t know it, but they were soon to follow.

Seaver made the Mets a year later. Then he made the Mets over.

Tom Terrific, 1944-2020. There are and have been many avenues into loving this team, a team hobbled by expansion when they were born and perversely celebrated as lovable losers as they barely learned to crawl let alone walk. We understand imperfection. We revel in humanity. We root for the underdog because we fancy ourselves the underdog.

But then we got somebody who shattered every paradigm about what it meant to be the New York Mets and to love the New York Mets. Somebody who was as far from losing as first place was from tenth. Somebody who not so much flirted with perfection but set up shop just down the block from it. Somebody who was human, yes, but performed in a superhuman manner, leaving behind an indelible image of a pitcher and a person who could not be beat.

That ethos and ability took Tom Seaver to the major leagues, then to its top, where he stayed for the balance of two decades as an active player and then forever after as an immortal. Find me a better pitcher than Tom Seaver. I’ve been a fan of this sport for 52 seasons. I haven’t found one, though to be fair, I stopped looking after I found No. 41.

Seaver played baseball for as long as he could, then checked in and out of the game as he chose. After his retirement, we saw him both reasonably often and not nearly enough. He held a few titles as an emeritus Met, but living legend amply covered his portfolio.

Half of that all-purpose descriptor is gone now, with Tom a victim of complications from Lyme disease, dementia and COVID-19. We knew about how the first one brought on the second. I hadn’t heard anything about the third, but this is 2020, and when more than 180,000 of our countrymen have died from a virus, one or more is bound to be somebody you can’t believe could be ended. We couldn’t believe Tom Seaver had to retire from public life in the first place, in 2019. He was too strong, too much the champion. Nobody filled out the spot atop a pitching rubber like Tom Seaver. I don’t know jack about wine, but I’m sure nobody filled out a vineyard like Tom Seaver, either.

I came to loving the Mets in 1969. Tom Seaver was instantly my favorite Met of all time. All time has yet to expire where my affection is concerned. He was the best when the Mets were the best, and perhaps as a six-year-old that was all I needed to know. Soon the Mets wouldn’t be so much the best, but Tom never ceased, not as far as I could reckon. He won twenty games for us four times and five times overall. He won the Cy Young three times. He pitched in two World Series. He lifted us to our first world championship, the world’s least probable, earned to an Amazin’ extent on the right arm of the man observed by anybody with any sense of the game as the most likely to succeed. When the time came for his ticket to be stamped for Cooperstown, the process couldn’t have been more of a formality: 311 wins; a 2.86 ERA over twenty seasons; and 3,640 strikeouts translated to a 98.8% Hall of Fame approval rating, the highest any starting pitcher has ever drawn.

I’m always citing numbers with Seaver. I can’t help myself. They were so astounding to me, so far beyond what anybody else was posting. You can wake me up on Christmas morning, as the saying goes, and I can rattle them off: 16-13; 16-12; 25-7; 18-12; 20-10; 21-12; 19-10; 11-11; 22-9; 14-11; 7-3. Then 6/15/77. Then 4/5/83. Some numbers in between and thereafter for three other teams. Then 41 on the wall, 425 out of 430 votes from the BBWAA and, honestly, I can swim in those numbers for hours.

But you can look those up on Baseball-Reference or anywhere. Tom Seaver transcended his statistics. The professionalism. The striving. The striding. The knee in the dirt as he drove the ball toward home plate, to whichever spot he judged optimal for the achievement of an out. The fastball that blew as many as ten batters in a row away. The reimagining of his arsenal as he grasped that his inherent physical talents were diminishing. The Franchise, obviously. A man who showed up at Shea in 1967, refusing to suffer losing gladly. A man who put away his gear in 1987, declining to compete at a level that wouldn’t permit him every chance to win and win again. For a generation, he was the personification of winning. I knew it. His teammates knew it. The opposing batters knew it. Magnificence cross-bred with consistency leavened with the intensely cerebral and the indefatigably competitive. Oh, brother, Tom was more than terrific.

Terrific only began to say it. Yet it says so much.

by Greg Prince on 2 September 2020 12:17 pm Perhaps someday I’ll find myself engaged in conversation with Ariel Jurado. We’ll likely talk about his baseball career; how it brought him to the Mets; and the challenges he endured, particularly that night in Baltimore in 2020 when, in the process of becoming the franchise’s 1,107th player overall and that season’s tenth Met starting pitcher 36 games into a 60-game campaign, he experienced what Wayne Randazzo termed a “bloodbath”: six hits allowed his first time through the Oriole order, punctuated by a three-run homer from Renato Nuñez. Or maybe we’ll gloss over that part and focus on his final two innings, for after giving up five runs in the first and second, Jurado gave up no runs in the third and fourth. True, it still calculated to an 11.25 ERA and the Mets were en route to a 9-5 defeat, their fifth consecutive loss, but I’d like to think that tact is the better part of discretion. Hopefully, in this hypothetical scenario, Ariel and I will find happier topics to talk about.

Honestly, chances are I’ll never chat with ex-Texas Ranger Ariel Jurado, who wound up no-decisioned because the Mets hit some for a while and tied the game after he left (Franklyn Kilome took the L), but you never know. For example, as I began my lifelong devotion to the New York Mets more than fifty years ago, I never would have imagined I’d someday spend forty minutes on the telephone with one of the players I spoke to then only through the television.

On April 10, 1968, Art Shamsky became the 160th player in Mets history. Like Jurado, Shamsky’s Met career commenced with a defeat, 5-4 at San Francisco. Better days were ahead. One of them included a 9-5 Mets win, in Atlanta, in the first game of the playoffs a year later. Art had three hits that day, three hits the next day and another the day after that. In the 1969 National League Championship Series, Shamsky batted .538 as the Mets swept the Braves. That performance spurred them to a pennant and earned them a trip to the same city where Ariel pitched last night.

Different Orioles. Different Mets. Different times. The games — five in the World Series; four of them won by the Mets — didn’t take nearly as long back then, but the memories they generated endure indefinitely. As has Art Shamsky, who fits my concept of too big a deal to give me the time of day, yet graciously gave me that and plenty more earlier this week.

We were talking because these days Art Shamsky, outfielder/first baseman for the Mets from 1968 through 1971, hosts an eponymous podcast and he wants to make sure Mets fans know it’s available for listening and enjoying. The Art Shamsky Podcast is indeed a very pleasant conversation. Art started the show a few months ago to bring a little light to dark days. Nothing earth-shattering, just good, solid talk with people you’re delighted to hear from. “I just want to try to make it as casual as possible,” Art told me. “We’re just having a conversation.”

Joe Namath’s joined Art’s conversation. So have Bob Costas and Al Roker. Phil Rosenthal, the sitcom creator who put Shamsky on Everybody Loves Raymond (and named the show’s bulldog after him), returned the favor and guested. “Not only sports people,” Art explained. “I’m interested in other professions.” Nevertheless, Ed Kranepool, Jay Horwitz and Howie Rose have also appeared, catering somewhat to those of us primarily interested in one particular line of work.

A podcast can hardly heal a world in pain, but listening to Art Shamsky’s might make a Mets fan feel a little better for a little while. Why does Art Shamsky host a podcast? Other than “why not?” If you’ve been a consumer of New York sports media going back a ways, you aren’t surprised to hear Shamsky conducting these interviews because you remember this is what Art has been doing on and off since retiring from baseball in 1972. His foot nudged through the broadcasting door on June 18, 1977, when he was hired by NBC for a last-minute call of a Reds-Expos game in Montreal. It wasn’t just any Game of the Week. It was Tom Seaver’s first start for Cincinnati. Art teamed with Marv Albert that Saturday afternoon, and things clicked pretty well for a first attempt at a new endeavor.

“I thought it was really easy,” Art admits. “In reality, it was not easy.”

The Art Shamsky name, accompanied as it was by a World Series ring, opened more doors, but he worked at improving his game, just as he did across eight seasons as a major leaguer. When Mets fans discovered an entity called SportsChannel was showing the games that had been confined previously to radio, they heard Art offering analysis alongside Bob Goldsholl. That was in 1979, when cable TV was a novelty through much of the Metropolitan Area, making Shamsky a pioneer — and, when you think about it, the first forebear of Keith Hernandez and Ron Darling. For three seasons, Art called games on cable; in the last of those years, 1981, he rotated among the Channel 9 and WMCA booths as well as SportsChannel’s, working with Steve Albert, not to mention a couple of Hall of Famers in Ralph Kiner and Bob Murphy. “Just a wonderful experience,” Art calls it to this day, even if the Mets teams he announced weren’t quite ready for prime time.

Art also channeled his budding talents into the groundbreaking Channel 5 show Sports Extra, serving as correspondent for a program that was about as must-see to a New York sports fan in its heyday as Kiner’s Korner. For a half-hour on Sunday nights, you received sports news, sports features, sports talk, all about New York, all much deeper than you got anywhere else. For the 10:30 touchstone, Art honed his conversational skills as he traversed the Tri-State, dealing with jubilant and desultory locker rooms alike. “You go into a clubhouse after a tough loss and try to interview somebody,” he says, “it’s a learning experience.” Recounting assignments that brought him into contact with everybody from the dynastic Islanders to tennis phenom Tracy Austin, Art considers the Sports Extra experience “wonderful years,” and is quick to credit producer Norman Ross and on-air colleagues Bill Mazer and John Dockery among the “wonderful, top-notch people I got to work with. I learned a lot.”

The veteran New York sports fan ear recognizes Art’s voice as well from the original WFAN, 1050 on your AM dial, where he hosted the station’s first midday show in 1987 from his restaurant. There were other stops along the way, including Channel 11 and ESPN. Though he may have started behind the microphone and in front of a camera with little journalism experience, being an athlete in the biggest media market in the nation couldn’t help but prepare him for this next chapters.

“When I played in Cincinnati, you had two writers and maybe one from Dayton,” Art recalls. “In New York, it was a different story: 10, 12, 15 writers from all the different papers, UPI, AP.” Art interacted with all of them, and his assessment remains “they were fair to me.” Maury Allen helped him ghostwrite a column for the Post that appeared on Saturdays, but that didn’t stop him from forging respectful working relationships with Allen’s competition. “Dick Young, Red Foley [of the Daily News], all of the great writers from the New York Times, Newsday, the Long Island Press, the New Jersey papers — they were all fair to me.”

Appreciating what goes into a reporter’s job allowed Art to develop the insights it took to take up the profession himself. His experience as a ballplayer in turbulent times gives him an inkling of an idea of what it’s like on the field in 2020. “There are some things that are similar,” he says of then and now. “The late ’60s and early ’70s were some awful times. The war in Vietnam, the city was down, in bad shape, morally and spiritually.” Against that backdrop, the 1969 Mets played ball so dazzlingly that a galvanized citizenry was grateful for the distraction. Today, with the world “upside down,” Shamsky acknowledges “there are a lot of problems” impossible to ignore, no matter how much one wishes to focus on fun and games. “In some ways, the world is still in a crazy situation.” Sportswise, “this year’s situation, with teams addressing social unrest and players taking stands is different in some ways, regarding what they’re trying to do in terms of making people’s lives better. Whether it works or not remains to be seen.”

In 1969, when New York had the Mets to lift its mood, those Mets had 162 games to pursue their elevation. The vault from ninth place to first place made it a season for the ages. Art hears regularly from people telling him, “you guys made me feel a lot better, if just for a brief period of time.” Nobody’s really asking for, let alone expecting, such miracles from the 2020 Mets, and it would be a bit much to believe any baseball team could mean as much to their times as the 1969 Mets meant to theirs. Conceding that he might be a bit subjective in his view, he asserts his team was no ordinary champion, not the kind of ballclub you have to look up in a list. “Most people,” Shamsky says, “will always remember the 1969 Mets won the World Series,” what with their legacy handed down to at least two generations. If last year’s fiftieth anniversary celebration is any indication, there are probably more to come.

“The fans treated us so wonderfully last year,” Art says, adding his gratitude for the serendipity that had the surviving ’69ers reuniting in a pre-pandemic atmosphere. “Kids not born yet know about that team from their parents and grandparents. They ask me about the black cat, Tom Seaver’s imperfect game, the Steve Carlton 19-strikeout game, the pair of games we won 1-0 in the doubleheader. They want to talk about it and they want to hear more about it.”

Many folks, he adds, will always remember being at Shea Stadium for the moment those Mets became world champions, on October 16, 1969, even if chances are they were physically elsewhere. “I think I’ve had 100,000 people tell me they were at the final game,” Shamsky estimates. “Now the ballpark held about 53,000, but if they were there in their mind or in some capacity, that’s fine with me.”

It would also be fine with Art if you accessed the Art Shamsky Podcast from any popular podcasting platform; follow Art on Twitter via @Art Shamsky; keep up with all he’s up to at artshamsky.com; and, if you want to give the gift of Art, arrange a video message from No. 24 for the special Mets fan in your life at cameo.com.

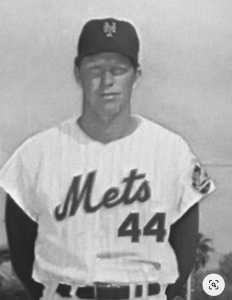

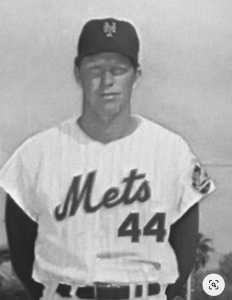

by Jason Fry on 1 September 2020 5:06 pm Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

Hark ye yet again—the little lower layer. All visible objects, man, are but as pasteboard masks. But in each event—in the living act, the undoubted deed—there, some unknown but still reasoning thing puts forth the mouldings of its features from behind the unreasoning mask. If man will strike, strike through the mask! How can the prisoner reach outside except by thrusting through the wall? To me, the white whale is that wall, shoved near to me. Sometimes I think there’s naught beyond. But ’tis enough. He tasks me; he heaps me; I see in him outrageous strength, with an inscrutable malice sinewing it.

1967 was a strange year for the New York Mets.

The 1966 club had achieved a pair of rather dubious high-water marks, losing fewer than 100 games for the first time in its history and escaping the National League cellar. (They lost 95 and finished 7.5 games ahead of the Cubs.) The end of that season marked a turning point, as original general manager George Weiss retired and handed over the reins to Cardinals import Bing Devine.

Devine immediately took a buzzsaw to the roster, cutting players and striking deals. Before spring training, Devine had traded away Ron Hunt, the team’s first non-ironic homegrown star; original Met Jim Hickman; and Dennis Ribant. And he kept tinkering throughout the season — 54 players appeared in a game for the ’67 Mets, including 27 pitchers, which tied a big-league record. Thirty-five of those players were making their Met debuts; 12 were making their big-league debuts. The constant turnover annoyed fans, who showed up at Shea in reduced numbers, and helped precipitate the early departure of manager Wes Westrum. He resigned before the club’s final road trip, telling the press that “I just don’t want to manage this club anymore.”

Devine’s tenure would only last a single season; he returned to St. Louis after Stan Musial stepped down as GM, replaced in New York by Johnny Murphy, a former Yankees star reliever who’d been Weiss’s top scout. Devine’s ’67 Mets landed back in the basement, managing 61 wins, or 1.13 per Met. Still, Devine did lay the groundwork for better days. He moved Whitey Herzog from the third-base coach’s box to the front office, where he’d build a phenomenal farm system (which should had been the precursor for his managing the ’72 club, but that’s another post). And Devine’s new Mets included ones who’d soon ascend to immortality: Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman, Don Cardwell, Ed Charles, Cal Koonce and Ron Taylor. (As well as one who got away, Amos Otis.)

They weren’t all gems, of course, as that 61-101 record might have told you. There was Don Bosch, a center fielder hyped as the second coming of Mickey Mantle who turned out to be about half the Commerce Comet’s size; Phil Linz, famous as a harmonica-wielding Yankee agent of chaos; and a host of answers to future trivia questions, such as Dennis Bennett, Bill Graham, Joe Grzenda, Joe Moock, Les Rohr, Bart Shirley and Billy Wynne.

One such trivia question might involve Al Schmelz. Schmelz was recalled from Jacksonville at the end of August and made his big-league debut at Shea on Sept. 7, relieving Jerry Hinsley in a game the Mets were losing 8-2. The first batter Schmelz faced was Tim McCarver, who flied to right. He gave up a double to Mike Shannon, who got thrown out at third, and then surrendered a long home run to Julian Javier. His final line was 2 IP 3H 1 R 1 ER 1 BB 2 K. Schmelz then sat in the bullpen for more than two weeks before being called upon to pitch the top of the ninth in Houston. He allowed a triple to Chuck Harrison but contributed a scoreless inning; the Mets lost, 4-2.

And that was Schmelz’s career.

Of course, a player’s stint in the big leagues isn’t the entirety of his career — it’s more like the part of the iceberg above the waterline, a bright spot that gives little hint of what might be underneath. I began my seriocomic, largely doomed exploration of that career because of baseball cards.

It started the summer before college, when I ill-advisedly traded a Rickey Henderson rookie card to a pair of neighborhood kids in return for “every Met card you have.” That made the kids go away, which is all I’d wanted, but also left me with a grab bag of mid-80s Mets cards. I’d collected from 1976 through 1981, and had the singularly terrible idea of bridging the gap between my childhood collection and the new cards that had fallen into my lap — one of those light-bulb-going-off moments, except the light bulb is a warning that you’re going to spend thousands and thousands of dollars on a hobby you’ll never be able to escape.

That bad idea sent me foraging in St. Petersburg, Fla.’s baseball-card shops, until I had every Met from ’76 on. And then the dominoes started falling in grim succession: Why not get every Mets card released by Topps back to 1962? Why not get every Met card released by Fleer, Donruss, Score and Upper Deck? Why not get Topps cards for guys who were on the Mets’ roster in a given year but never actually got a Mets card? Why not get the Topps cards for Mets from all their non-Met years? I didn’t know about high numbers, or what rookie cards cost, or that Al Weis shared a rookie card with Pete Rose. But I’d learn. Oh boy, would I learn.

One thing I learned was that 34 of 1967’s 35 new Mets had baseball cards in one form or another, even if they came with asterisks attached. Some appeared attired as members of other teams: Bennett (Red Sox), Shirley (Dodgers), Nick Willhite and Wynne (Angels). Hal Reniff, sad to say, is a Yankee. Rohr shared a 1968 rookie card with Ivan Murrell, a Houston outfielder wearing one of Topps’ blank black hats; future pitching coach Billy Connors shared a ’67 rookie card with fellow Cub Dave Dowling.

Graham and Moock never got Topps cards, and their careers ended before minor-league baseball cards became common. Enter a veteran card dealer named Larry Fritsch. Fritsch had connections at Topps and issued several series of cards he called One Year Winners, giving cardboard immortality to players who’d never had a card before, and using photos shot by Topps back in the day. His efforts saved Graham and Moock from anonymity — Graham as a Tiger, Moock as a Met.

But there was no card for Schmelz. Just as there was no card for Francisco Estrada, Lute Barnes, Bob Rauch, Greg Harts, or Rich Puig. Those unfortunate players became the core of what I called the Lost Mets — a grim fraternity filled out by Brian Ostrosser, Leon Brown and Tommy Moore. (Ostrosser and Brown got minor-league cards so dismal they would have been better off with nothing; Moore got a lone card during his tenure with Florida’s late-80s Senior League circuit. Greg still thinks that card should count, an obvious error of aesthetic judgment I have chosen to forgive. I have that card, of course — my hypocrisy is of the flexible variety.)

I cobbled together cards for the Lost Mets using a Xerox machine to copy taped-together assemblages of old black-and-white team photos, computer print-outs and a Xerox of the ruffled pages of a phone book, which I felt looked old-timey but actually just looked weird. That was another bad idea that opened a chasm beneath my feet. Inevitably, I decided those paper cards wouldn’t do — the Lost Mets needed cards that looked like actual baseball cards, at least to an untrained and/or mildly forgiving eye. And so I started hacking around on Photoshop — a complex program about which I knew absolutely nothing — to create them.

My original terrible Frankenschmelz, decolorized and haunting Pinterest. The problem, I soon discovered, was that it was easier to find Jimmy Hoffa than to locate a decent color photo of Al Schmelz in a baseball uniform. A couple of Mets yearbooks had pictures of him grouped with other guys invited to camp — but they were always small and in black and white. He’s in the team photos — in glorious color, no less — in the ’67 and ’68 yearbooks, but of course he’s in the back, almost completely blocked by his teammates.

So I did the best I could. I took apart the ’67 team photo to make Frankenschmelz — Schmelz’s face, upper chest and arms, combined with Cardwell’s stomach and belt, and the 4 from Ken Boyer‘s uniform number, used twice. As a Photoshop noob, I had no idea about image quality or how to bend and distort pixels so pasted bits of another photo don’t look like they’re floating atop the original. The result is horrible — and, to my shame, it’s still one of the top results if you Google Schmelz. (“Al Schmelz,” by the way, also seems to be German for “aluminum smelter,” which for years made Googling him even stranger.)

A decent Schmelz photo became my white whale, and I the grim Ahab hell-bent on finding it. I even wrote to the man himself — twice — with no luck.

At some point during this increasingly insane pursuit, I realized I’d lost sight of the man behind that maddeningly nonexistent photo, and so I tried to figure that out. Here too Schmelz proved elusive, with only the barest outlines of his college and minor-league career emerging from articles that interchangeably referred to him as Al and Alan.

A hulking California kid, he transferred from junior college to Arizona State, where he starred in both basketball and baseball before concentrating on the latter. 1965 was his breakthrough — he won a College World Series title as a Sun Devils, with his teammates including Sal Bando, Rick Monday and Duffy Dyer, then followed that by playing for the Sioux Falls Packers of the Basin League and the Alaska Goldpanners, where he was part of a formidable starting rotation: Schmelz, Seaver, Danny Frisella and Andy Messersmith.

At the time the Basin League and the Goldpanners were showcases for amateur players who were either honing their skills or trying to catch scouts’ eyes. It worked for Schmelz, who was signed by the Mets in 1966 and went 12-0 for Auburn, fanning 133 in 113 innings. A promotion to Williamsport didn’t go as well — Schmelz walked far too many hitters in both stops — but the talent was obviously there, and during 1967’s spring training Westrum talked up the big right-hander as a possible member of his relief corps.

Better than nothing? Not by much. Schmelz’s 1967 tenure with Williamsport was largely the same as his time in ’66, but up he came for his cup of coffee. It was after that that things get murky. In the offseason he was one of three players offered to the Senators for the right to make Gil Hodges the Mets’ manager, with Washington choosing Bill Denehy over Schmelz and Tug McGraw. Schmelz was cut in spring training in 1968 and then went 0-11 pitching for Jacksonville, Vancouver and Memphis. His season ended on Aug. 28, when the Mets sent him home with the vague but ominous diagnosis of “a sore arm.”

In 1969 Schmelz pitched for Memphis, Pompano Beach and York. The results were unimpressive and in December the Mets sold his contract to the Royals. He never appeared in a professional game again, his career over at 26. He became a commercial real-estate broker in the Phoenix area, showing up in occasional accounts of Sun Devils alumni events, baseball charity functions and fantasy camps. I’ve never seen a retrospective of his career or a quote from him in a newspaper.

I can figure out the basics well enough — Schmelz suffered an arm injury in an era where they couldn’t be repaired, like so many pitchers did. The Mets hoped he’d regain his form, or learn to pitch differently, and so they shuffled him between different minor-league outposts and lent him out to other organizations — Vancouver and York were affiliates of the A’s and Pirates at the time. But beyond that I know nothing — not what he threw, not what the Mets thought of him, and not how he views his career. Even his page for the wonderful SABR Bio Project turns out to be a frustrating tease. He’s a visible object that’s but a pasteboard mask.

And so I kept doggedly looking for that elusive photo. Schmelz popped up in shots taken at a baseball fantasy camp in Arizona, but beyond the fact that he was decades past his playing days, he was wearing a 1990s Met hat and what I interpreted as a faintly mocking smile. In 2010 a snapshot showed up on eBay showing Schmelz wearing 16 instead of his more familiar 44. Of course it was in black and white. Inevitably, Schmelz’s face was mottled by shadows, his expression suggesting he’d just had a gulp of expired milk. I bought it anyway, added color and turned it into a new Lost Mets card to replace the Frankenschmelz. It was an improvement. It still looked terrible.

Oh come on. I took some solace in discovering I wasn’t the only Schmelz hunter out there. There’s a thriving subculture of baseball hobbyists whose quest is to assemble photos of everyone who’s ever played big-league ball, in every uniform they wore, and Schmelz is one of the names that elicits sighs.

One of that subculture’s leading figures is Keith Olbermann, who combines impressive investigative skills with an amazing memory for details. Olbermann had helped me in the earliest days of my Schmelz quest, noting (apparently from memory) where Schmelz could be found in the team photos. He was familiar with Topps’ simultaneously voluminous and haphazard photo archives, whose contents are the gold standard for baseball photo hunters, and reported that there was nothing for Schmelz. That was disappointing but no surprise — in 1967, as one of its early labor actions, the nascent players’ union told its members to stop posing for Topps. That’s why late-60s Topps cards feature lots of old photos and hatless shots in airbrushed uniforms.

As my quest continued, Olbermann became an eagerly awaited herald of Schmelz sightings. He unearthed a casual shot of our quarry on the grass in spring training with other Mets pitchers. It was in color — eureka! — but not very good — ugh! A group shot from the Instructional League came to light — apparently that’s when Schmelz wore 16. I found black-and-white photos from his Goldpanners tenure. But nothing was revealed that might let me end my hunt.

And then finally, in late 2016, the white whale was sighted and the crews were able to land a harpoon. Olbermann found and shared a Dexter Press shot of Schmelz, this time wearing 48.

A shot in color.

A shot where Schmelz is facing the camera.

A shot where Schmelz doesn’t look like he’s been kneed in the groin or is trying to make a hasty getaway.

Of course I made a new Lost Mets card — I honestly can’t remember if it was the third, the fourth or some even higher number. By now I was pretty good at Photoshop, adept at sharpening and color-correcting and other subtleties the program offers. And the image Olbermann had so kindly shared was big enough and clear enough to work with.

It came out OK. But only OK. Somewhere in the transition from digital image to card stock, Schmelz’s face wound up a little too red, and fuzziness crept into the formerly sharp details. Holding the finished card in my hand, I sighed and reached for my keyboard to open Photoshop and try again. And then I stopped myself. What I had was better than anything I’d had before, and better than what I’d recently imagined might be out there. More than that, I sensed, simply wasn’t possible with the mysterious Alan George Schmelz.

So the crews reeled in their harpoons and rowed back to the ship, and the great white whale vanished beneath the waves again. I assume he flipped his tail derisively as he went. That’s OK, as is the fact that I know he’s out there somewhere. Maybe I’ll run across him one day; for now, I’m content to stay in port.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1965: Ron Swoboda

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1986: Keith Hernandez

1988: Gary Carter

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2007: Jose Reyes

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2010: Ike Davis

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2019: Dom Smith

by Jason Fry on 31 August 2020 9:07 pm You know things have really taken a turn for the worse when even Jacob deGrom can’t save the Mets.

The Mets and Marlins reported for makeup duty a little after 1 pm Monday, with Miami not particularly excited at having to fly up and back to New York in a single day, and presumably even less excited to face the best pitcher in the National League. The Mets didn’t look terribly excited about the matinee either, having just had their season holed below the waterline by a mostly anonymous band of Plan B Yankees and now being required to make a home stopover before heading to Baltimore. The early innings fairly whizzed by, with 18 different guys not looking terribly interested in hanging around the batter’s box longer than necessary, and I had the same thought I think a lot of Mets fans had: DeGrom is dealing, the Marlins don’t want to be here, this could be a special day.

Call that Exhibit No. 954 in the continuing series, Don’t Try to Outguess Baseball. DeGrom gave up an infield single in the third to Lewis Brinson on a ball perfectly placed to confound both Andres Gimenez and Amed Rosario, was staked to a 2-0 lead in the bottom of the third, and then had the roof cave in come the sixth. Yes, there was an error by Pete Alonso that made three of the four runs unearned, but there were also too many balls left over the middle and hit a long way — deGrom has absorbed an absurd amount of unfairness during his tenure as the Mets’ ace, but he was beaten fair and square on this day. Shocking though it was to watch, even Superman occasionally flies into things.

After the game, the Mets made some head-scratching moves, acquiring Robinson Chirinos and Miguel Castro and reacquiring Todd Frazier, who left the team about five minutes ago. Chirinos is a backup catcher who seems to have forgotten how to hit in 2020, Castro is a reliever who throws a 98 MPH sinker but still somehow gets lit up a lot, and Todd Frazier is Todd Frazier. None of the acquisitions did much of anything to fill holes; Frazier, while a genial sort, threatens to block players who deserve playing time more than he does. We don’t know what the Mets gave up to get this underwhelming haul, beyond marginal prospect Kevin Smith, but I trust neither Brodie Van Wagenen nor the Wilpons in their red-giant phase.

The pleasures of the game were faint. There was the fact that it happened it all, I suppose, which really ought not to be nothing — it wasn’t so long ago that the idea of baseball as a distraction would have seemed like deliverance, regardless of the final score. And there was Robinson Cano, who may not like DHing but sure seems suited for it. In a season full of sighs and grumbling, Cano has looked a lot more like the Hall of Fame bat he once was than the player who stumbled and gimped through a foggy first season as a Met; it’s not enough to make the trade that brought him here a winner by any means, but seeing how that’s a sunk cost, anything that makes the deal more palatable is welcome.

But again, faint pleasures. The Mets aren’t out of it — it’s hard to be out of it in this weird sprint of a season — but it certainly feels like their chances are slipping away, and nothing they did at the trading deadline changed that dispiriting equation overmuch. To steal a beat from Sunday’s post, today wasn’t a good day either.

by Jason Fry on 31 August 2020 1:35 am Shot. Chaser.

If I were a kind recapper, this paragraph wouldn’t exist. All you need to know is right up there, and why do you want to get riled up all over again? Go outside. Pet your dog. Call your mom. Do something else. Do anything else.

All right. The rest of you weird masochists can keep reading and absorb the earthshaking analysis that no one connected to the New York Mets had a good Sunday.