The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Jason Fry on 6 April 2025 12:16 am The City Connects were the perfect uniform for Saturday night’s Mets game, played in murky gray conditions with an inescapable wet chill, cascades of mist wafting through the air, and any ball that touched outfield grass leaving a spray of droplets to mark its progress.

A surprisingly big crowd showed up despite the obvious attractions of watching from a warm couch (my choice) or a friendly barstool instead. Now, no one who follows baseball makes it to their late teens without realizing that the sport is a lousy vehicle for restorative justice. Baseball doesn’t care that you’re one of the hearties sitting in the misty Promenade, that your commute to the ballpark was taxing and unpleasant, or that you’ve been having a rough go of it and would greatly appreciate a ringside seat for a win.

But sometimes you get a win, even when it looks like you won’t.

Former Met Chris Bassitt escaped harm from leadoff doubles in the first and second and then went to work, eviscerating the Mets with selections from his deep arsenal. I always liked Bassitt, who goes about his business looking vaguely pissed off and determined to blame hitters for it, and mourned his rather obvious lack of interest in further duty with the Mets after his lone season with us.

Griffin Canning wasn’t quite as good as Bassitt in his second Mets start, though he was still perfectly fine; he and Jose Butto were undone by an irritating fourth inning that saw Toronto find infield holes with three ground balls in sequence, good for a 1-0 Blue Jay lead. That lead became 2-0 in the sixth, as Butto surrendered back-to-back two-out doubles before Huascar Brazoban — pitching this year with better control and what looks like more conviction — calmed things down.

The Mets then arguably caught a break in the bottom of the seventh, when Toronto manager John Schneider removed Bassitt, who’d thrown 92 pitches and looked, at least to me, like he had plenty left. Yimi Garcia surrendered a single to Brett Baty and walked Jose Siri, but escaped when Starling Marte had a desultory at-bat as a pinch-hitter.

Brendon Little wasn’t so lucky in the eighth, however; with two on and two out Jesse Winker lashed a knuckle-curve that got too much plate to right-center. Winker thought it was out, and if hadn’t been a cold soggy night in April he would have been correct; as it was the ball just eluded George Springer, who was hurt on the play, and Winker wound up with his second triple of the chilly night and a tie game.

Edwin Diaz navigated a somewhat bumpy top of the ninth and the Mets went to work against Nick Sandlin, whom I remember carving them up as a Guardian last summer. With one out Siri walked for the second time, which is both admirable and a little startling. Luis Torrens, a late scratch called upon after Carlos Mendoza pinch-hit for Hayden Senger, spanked a single over the infield to bring in Jays closer Jeff Hoffman with Francisco Lindor at the plate.

Lindor wasted no time, a kind gesture as not even the Citi Field hearties had much stomach for free baseball on this night. Hoffman’s first pitch turned out to be the only one he’d throw: a slider that sat in the middle of the plate and which Lindor whacked to center field. It was one of those plays where you put your hands up instantly because everything is going to be just fine unless the runner leaving from third pulls a hamstring, there’s an earthquake, or the Rapture occurs.

None of those things came to pass: Siri trotted home unmolested, Lindor got showered in water and bored-ballplayer snacks, and all involved got to go home and warm up. It made for a grinding yet ultimately interesting game and a Mets win. Restorative justice? Nah — as we’ve covered, baseball doesn’t do that. But on a chilly April night it felt close enough.

by Greg Prince on 5 April 2025 2:31 am The fans who wait for their team to come off the road while the year is still young are rewarded for their patience with two Openers. There’s Opening Day, which is festive no matter that it’s taking place in another ballpark, and there’s a discrete Home Opener, which grants us a second helping of holiday spirit. As long as we get to unwrap a win somewhere along the way, the composite festiveness outdoes multiple Christmases.

Winning was indeed involved in the Mets’ 2025 Home Opener, which made the déjà vu quality of looking forward to starting all over again quite worthwhile. We may have gone through those “oh boy, baseball is back!” emotions eight days earlier when our team was breaking the season’s seal in Houston, but home is home, and getting to do essentially the same fun thing twice in such a short span can be a paean to righteous gluttony. Picture your favorite all-you-can-eat buffet. Your eyes were probably bigger than your stomach as you grabbed your first plate. In all honestly, you consumed what you really needed by the time you cleaned it. But, look — they’re bringing out a fresh tray of penne or spare ribs or whatever it was that lured you in this joint. Why, yes, you think you will take another trip up there.

The Mets’ second Opening Day no doubt left us feeling more sated than the first one. This one served up a victory that was convincing from every angle, a 5-0 shutout of the Toronto Blue Jays, a franchise that played the very first Spring Training game of its existence versus the New York Mets on March 11, 1977, but, historically speaking, was a stranger at a strange interval in Flushing on Friday. Interleague play is no longer novel, but Mets versus Jays for our Home Opener? Mets versus any AL interloper? In every Home Opener from 1969 through 1992, when the Mets were a member in good standing of a six-team division, the visitor to Shea was a National League East opponent. That never felt strange. I have a hard enough time accepting that we sometimes start our home slate versus the Diamondbacks or Brewers, but at least they’re situated in the same circuit as us.

Of course, once the pageantry is presented and ball begins to be played, it’s more or less just another baseball game…though not altogether. If it was truly Same Bit/Different Day, would nearly 44,000 make it their business to be at Citi Field? Would however many bazillions beyond that compose a robust viewing, listening, and sneaking-an-update audience while ignoring afternoon business they’ve decided was less pressing? The Mets had already played a handful of just-another-games. This wasn’t going to be one of those.

Differentiating it from just-anotherness were, in something approximating a particular order…

• Francisco Lindor, who led off the game with a hustle double that wouldn’t take single for an answer (score one for replay review);

• Pete Alonso, who went to the opposite field and kept going until he had a two-run homer;

• Tylor Megill, whose second consecutive sublime start here in his fifth season has me thinking he’s on a career trajectory resembling that traced by Bobby Jones circa 1997, the year the secondary pride of Fresno put it all together for a few months;

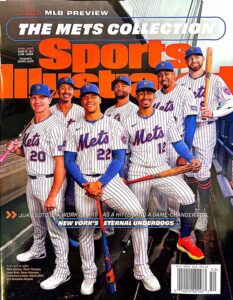

• Juan Soto, the new kid in (the good part of) town who lashed an RBI double that looked like one of those hits that had suitors lining up for his services that became ours, and threw in a nifty catch and heady stolen base for Steve Cohen’s money as well, no extra charge;

• and those inevitably unsung relievers who backed up Megill’s five-and-a-third nearly spotless frames with a spiffy three-and-two- thirds of their own. Hail Reed Garrett, A.J. Minter — abetted by cameras that corrected an umpire who didn’t understand the function of a foul pole — and Max Kranick, the Mets fan from Scranton who grew up to be the Mets closer on Friday.

Kevin Gausman was pretty beguiling between the Mets’ runs in the first and the sixth, but sometimes two bountiful innings is all it takes. Identities are in larval stages this early in a season, yet I’m coming to believe Mets baseball in 2025 might become synonymous with heating the iron, striking while it’s hot, and not letting it cool all the way off before striking again. Any lineup that circles back to Lindor, Soto, and Alonso isn’t going to go cold for long. A little more length would be welcome, and ought to materialize once Jeff McNeil and Francisco Alvarez return, but as long as we’re getting representative production from Nimmo, Vientos, and Winker/Marte, the offense shouldn’t go into sleep mode too often (never mind that it snoozed several nights on the road). Sean Manaea receiving a rousing ovation during the pregame introductions reminded us there will be more to the starting rotation eventually, yet what we’ve received to this point has been adequate-plus. We shall resist singing too many praises of the bullpen, because we don’t really know how to feel confident in Met relievers, but, you know, so far, so good.

Maybe it’s the holiday atmosphere attendant to a Home Opener talking, but it definitely wasn’t just another game, and maybe this isn’t looming as just another year.

by Greg Prince on 3 April 2025 2:55 pm It might stretch credulity if I declared, yup, I knew Pete Alonso was gonna launch a three-run homer to tie the Mets-Marlins game at four in the eighth inning on Wednesday. The Mets had played ragged ball across the first seven and they weren’t too many outs away from a tails-between-their-legs flight home for a Citi Field opener that would necessarily lose a little luster if its purpose was to hail a 2-4 team. Yeah, everybody would stand and cheer the welcome of what Howie Rose unfailingly refers to perennially as the National League season in New York, but discordant notes would infiltrate the runup to introductions and ceremonial first pitches, and who wants that?

Nobody who cares about the Mets. Not you. Not me. Not Pete Alonso, who cares about the Mets as much as anybody, given that he’s carried them intermittently for six going on seven years. In the good Met years, he’s had help. In his less good personal years, he’s insisted, no, he’s got this. The couch isn’t that heavy and the flights of stairs aren’t that steep.

You sure you got this, Pete?

If I wasn’t sure specifically that a tide-turning dinger wasn’t en route, I certainly maintained confidence in Pete as he stood in against Calvin Faucher. Two singles had been bracketed by two outs. Francisco Lindor was on second. Juan Soto was on first. Lindor achieving anything beyond fatherhood in late March and early April is already a victory. Soto’s contribution was a tapper toward first that became a fielder’s choice that nailed Luis Torrens trying to come home from third. Not the worst intermediate outcome, for if Torrens hadn’t dared to attempt to score, you have him on third and Francisco on second, and an open base to put Pete possibly. I don’t know Clayton McCullough’s managerial tendencies yet, even if the rookie skipper already wears that familiar “I’ve been managing the Marlins too long” look every time an SNY camera spots him.

Pete is up, and Pete is working Faucher, and it’s not unlike two nights earlier when the Miami pitcher is Cal Quantrill. The bases were loaded then, one of them also occupied by Soto. Soto, even when he’s not slugging, is getting on base. What few big innings the Mets have cobbled together seem to feature Juan somewhere. The result Monday was Pete’s grand slam, which loosened up the drumtight Met offense once and for all…or so we thought Soon, most Met bats went back into storage. From the seventh inning in the first game of the Marlin series through the seventh inning of third and final game, nineteen innings in all, the Mets had scored three runs. The Marlins weren’t making them look bad. They were doing it to themselves.

But Pete is still up in the eighth on Wednesday. He’d driven in one of the Mets’ three runs from their dry period, way back in the first inning on a double that brought home Soto. The A&S Boys doing their thing, stocking and unstocking bases. High-end retailing has never been so luxurious. Yet a second Alonso double, of the leadoff variety, went to waste in the fourth. By then, the Fish led, 2-1, Clay Holmes had been little more than adequate, and our fielding was showing itself allergic to smoothness. It was easier to imagine the Mets going 2-4 on their first road trip than deciding another Arctic blast was about to descend on South Florida.

Still, I felt good about Alonso as his at-bat versus Faucher preceded. It was a long one. How long is a long at-bat? It should have multiple balls. It should have multiple fouls. It should have a batter who’s done this before. Pete did this on Monday, turning Quantrill’s seventh pitch into his four-run four-bagger. You might remember Pete doing something similar one evening last October versus Devin Williams, then of the Brewers. The process yielded a three-run homer and effectively clinched a postseason series. He needed five pitches that night. Funny, it seemed like more.

The point is that when Pete Alonso gets a count going deep, the count goes in his favor. Other hitters, too, but this is Pete we’re talking about. Anticipation builds around Alonso. He’s been known to anticipate too much from himself and not let the count (let alone the drama) build. Yet you are so taken by the examples that counter that tendency that sometimes you will yourself to expect exceedingly positive resolution.

Five pitches in Milwaukee. Seven pitches on Monday. Wednesday, the balls and the fouls got Pete to a ninth pitch. That was the one that flew out of whatitsName Park to tie the game, 4-4. The Mets were no longer sleepwalking their way to Flushing. The tie signaled a win was at hand. It took eleven innings. It required seven of the eight relief pitchers Carlos Mendoza employs. It especially required the tagging and throwing wizardry of Torrens, who backed up Alonso’s raucous offense with no-joke defense. It ended with a 6-5 Mets victory and a respectable enough 3-3 start to the season (at .500, tails may be removed from between legs and move freely about the cabin). The last time the Mets won a 6-5 decision, it was the end of last June’s trip to London, highlighted by Luis behind the plate stepping on the dish with the bases loaded and then throwing to Alonso for one of the damnedest double plays anybody had ever seen, especially directly prior to a flight home. Back in the present, I had a feeling Luis (who himself was on in relief of Hayden Senger) would come through, too. One of his tags required replay review. “They’re gonna overturn the safe call,” I thought, and they did, much as “he’s gonna come through here” rang true as Pete took Faucher deep in the count and deeper over the center field wall.

A little Pete, a little Luis, a little confidence. Welcome home, men. No notes needed.

by Jason Fry on 2 April 2025 7:51 am Another sign the new season isn’t quite so new? You find yourself struggling to accentuate the positive when things don’t go well.

Things didn’t go well Tuesday night in Miami: Kodai Senga was shaky early, the Mets’ hitting resurgence turned out to be a one-day affair, and Francisco Lindor made not one but two errors at shortstop. The first was just an annoyance, forcing Senga to throw all of one extra pitch, but the second led to disaster, as someone named Graham Pauley doubled two runs home, providing the margin the Marlins would need to beat the Mets behind Sandy Alcantara and his second audition for a new summer employer.

OK, there were some positives. Senga’s ghost fork was effective, which was reassuring after a spring training in which Senga didn’t quite look like himself and you heard mild but real rumblings of discontent around him. Max Kranick contributed three innings of flawless pitching. Luisangel Acuna looked good whether equipped with bat or glove. And new father Lindor did collect his first hit and RBI.

But that didn’t wind up feeling like much in light of that 4-2 verdict, which grates a little more because it was the Marlins at Soilmaster Stadium. (Though it sounded more like Citi Field South.) Once again the Mets looked set up for a storybook finish that fizzled. Once again the bats slumbered. Once again things felt off-kilter and out of sorts.

So far the Mets are a team that was predicted to mash but has done so for exactly one night, and a team that has had superb starting pitching when that was supposed to be their biggest question mark. Don’t try to make sense of it; that so far ought to be the tipoff that we’re attending Small Sample Size Theater, which is reliably surreal, and of course baseball is nothing if not a serial confounder of expectations.

A relatively recent addition to baseball discussions is the concept of error bars — how actual performance can deviate from baseline expectations, both for better and for worse. The Mets’ error bars are a little arsy versy right now in multiple ways, with the starting pitchers bunched up where we thought we’d find the hitters and the hitters occupying the space where we thought we’d find the starters. That’s part of baseball too; it’ll either work itself out or we’ll tell stories about why it didn’t, and eventually those stories will come to make sense. But right now nothing much does. It’s too early to say what this incarnation of the Mets will turn out to be, but we can all hope it involves a lot fewer games like Tuesday’s.

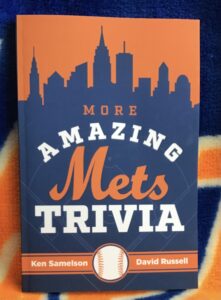

by Greg Prince on 1 April 2025 11:43 am On Monday, I was excited to receive in the mail an advance copy of a great new book called More Amazing Mets Trivia, put together by my dear friend Ken Samelson and his co-author David Russell. I’m delighted to reveal that I did a little reconnaissance on the manuscript last summer, as Ken knew I know a few things about Mets trivia.

Who am I kidding? I know more Mets trivia than could possibly fit in one volume, which is why I’m sharing some bonus questions and answers that might work well in any revised edition Ken and David are planning. Test your knowledge below and see if you’re as much of a stickler for Met facts as I am.

This book is the real deal. Where did Pedro Alfonso get his very familiar nickname?

Pedro, whose fifth-inning grand slam to right-center field at leavemealoneDope Park effectively rescued the Mets’ floundering campaign on Monday night, was already given the benefit of the doubt by Mets fans due to his being the nephew of beloved infielder Edgardo Alfonso, the most chronically misspelled Met Hall of Famer in franchise history. It would have been easy to refer to Pedro as Potsie — the way fans labeled his uncle — but in Spring Training of his rookie year, family-friendly manager Nicky Caraway Seed suggested Alfonso played his original position, third base, like “he’s [bleeping] naked on a [bleeping] horse,” and thus the nickname “Polo Bare” stuck, and all resulting Polo Power emanated from across the diamond. Alfonso now sits 25 strawberries away from the all-time Met record for most individual pieces of fruit consumed in the state of Florida.

With what celebrity did starting pitcher Pete Daverdson “trade” spouses?

Daverdson gave the 2-2 Mets six innings of two-run ball, the club’s first qualitative start of the young, crumbling season. The southpaw was no doubt energized by the presence of his temporary lifemate Scarlett Johannson, obtained in a cash considerations swap with his good friend, SNY sideline reporter Fritz Gelbs. Longtime observers will remember the last time such a controversial transaction rocked baseball was in 1976, when commissioner Bowie Kuhn vetoed Oakland owner Charlie Finley’s sale of Rollie Fingers to Mrs. Mike Kekich (this was before the reserve clause was completely eliminated).

What stands as Louie Torrent’s signature moment as a Met?

The Mets’ backup catcher contributed a two-run home run to the team’s desperately needed 10-4 victory in Miami, ensuring Louie won’t be known merely for that one time he “made it rain,” bringing a torrent of dollar-bill showers on a notable swing through the Midwest’s most high-end gentlemen’s clubs. Interestingly, the Mets were in London that week, but, as Torrent likes to say through a translator, “the Lou wants what the Lou wants, so you better bring a [bleeping] umbrella, fella. Besides, whaddaya think our meal money is for — dinner?” Torrent will continue to fill in as the Mets’ starting catcher until primary backstop Alvy Franklin leaves the unable list and resumes proving that the 2020s are indeed “the Alvy Franklin decade”.

Brendan Nebbish is the senior Met in terms of service time. When was his first game?

The Mets’ first-round draft choice in 1965, Brendan made his debut on April 10, 1968, Gil Hodges’s maiden outing as Mets manager. It was the first rung on a very long ladder Nebbish needed to scale to achieve his current level of renown. Just one year later, as the Mets cruised to an easy win over the Astros at Shea Stadium, Hodges made a point of marching out to left field to remove young Brendan for “growing facial scruff that indicates a lack of character”. The skipper feared kids in what was then called the Midget Mets program would look to Nebbish as a role model and resist shaving. “Next thing you know,” Gil elaborated to reporters, “youngsters will take a pass on personal grooming products and he’ll be messing with my Vitalis checks.” Properly chastened, Nebbish returned to the minors until the following April. His sixth-inning home run Monday night, which came as the Mets nurtured a precarious seven-run lead, was the first of his fifty-eighth major league season.

Marty Sterling batted leadoff Monday night in place of which Met mainstay?

Marty, scion of the silver-tongued Sterling family, found himself in an unfamiliar lineup position, thanks to Francoeur Lindor’s better half Frenchy giving birth to the couple’s third child and first son, Homer. Homer was conceived in the aftermath of last season’s delirious clubhouse celebration when Mr. Lindor went deep in Atlanta. With the Mets’ usual leadoff batter otherwise occupied, Sterling put the heretofore doomed Mets on the board in the third inning with a homer of his own. When he returned to the dugout, he warned the Lindors not to name their next child after what he’d just hit. Francoeur, who has never recorded a base hit in any calendar year prior to Mother’s Day, reportedly looked at his teammate in confusion and asked, “what the [bleep] is going on today?”

Hope you got ’em all right! But don’t fret if you don’t have as much clearly accurate Mets knowledge at your disposal as I’m obviously packing. The important thing is the Mets won, and Ken and David have a real fun book you should definitely check out.

by Jason Fry on 30 March 2025 11:59 am The first week of baseball is seductive and also a little dangerous: You’re so glad to have baseball back and to resume the rhythms of fandom that you can shrug off the disappointment that comes with every game having a winner and a loser. The first week really does offer participant trophies, and each season you need to relearn that you don’t keep those.

So it was with the third game of the Mets’ 2025 season, an odd little game that gets put in the books as a 2-1 loss to the Astros. (Strangely, there’s no meme of Howie Rose putting his headset down on the console in resignation and sighing, “put it in the books.”) I suppose I could raise my descriptive game a bit and try to bill this one as taut, tense or one of the other common pitchers’ duel adjectives, but mostly I found it annoying.

The Mets had one hit — one! — courtesy of Juan Soto in the first, a double over Jose Altuve‘s head, which you probably remember is closer to the ground than most of his MLB peers. That was it — if you arrived in the bottom of the first because you had an errand to run, or thought Saturday night’s game started at the same time as Friday night’s, you missed the entirety of the non-walk portion of the Mets’ offense.

The Mets’ best bid for a second hit came on the very last play of the game, and served as the final judgment from the baseball gods that this wasn’t our day. Once more facing Josh Hader, Soto led off the ninth by working out a walk. Pete Alonso popped up on the first pitch, his first anxious-looking AB of the new season, and Brandon Nimmo grounded to second, which moved Soto into scoring position and made Mark Vientos the last hope. Hader left a sinker in the middle of the strike zone and Vientos scorched it on a line — one that happened to intersect with the glove of shortstop Jeremy Pena.

/place headset on console

/sigh

[quietly] put it in the books

Good things did happen Sunday, starting with Griffin Canning looking awfully good in his Mets’ debut. Canning is 6’2″ but looks about 5’6″ on the mound, an impression I attribute to his even, almost elegant proportions — he doesn’t have a classic power pitcher’s big rear and thick legs — and to his pitching motion, which is admirably compact and fluid. None of that would have been worthy of note if Canning had pitched like he did in an Angels uniform last year, but the Mets have reinvented him and at least for a day it worked. Canning used his slider far more than he had in the past and it was a decidedly effective weapon against Houston’s lineup — a lineup, we should note, made up of guys who were pretty familiar with him. He gave up a solo shot to Pena (which I missed during a brief couch nap but apparently still counts) and a RBI double to Yordan Alvarez, a solid day’s work but, as it turned out, not enough.

Backing up Canning, Jose Butto looked sharp for an inning and a third and less sharp after that, which led to Max Kranick‘s Mets debut. Kranick, a Mets fan before growing up to become a briefly tenured Pittsburgh Pirate, was on the active roster for the wild-card series against the Brewers but never called upon, meaning he spent the offseason as a Mets ghost. He had to be champing at the bit to make his debut; he probably didn’t envision arriving with the bases loaded, one out and Alvarez looming at the plate. No matter: Kranick coaxed a foul pop-up from Alvarez, which Vientos made a nifty grab to snag over the camera well, and Christian Walker grounded out. Welcome to the ranks of the corporeal, Max!

Alas, Canning & Co. were just a touch less effective than Spencer Arrighetti and the Houston relievers who followed him. The Mets’ lone run was conjured out of thin air by Jose Siri, who lived up to his reputation as a maddening yet exciting chaos agent. Siri struck out aggressively in his first AB, and if you don’t think that’s an apt description, well, watch Jose Siri play baseball. But he then walked leading off the sixth, stole second easily and scurried over to third on a Francisco Lindor flyout to center. Up came Soto, who spanked Arrighetti’s first pitch back to him. Arrighetti stared down Siri, then turned to retire Soto at first, which is the way you do it. But the second Arrighetti turned his back Siri came flying down the line, arriving just ahead of Walker’s heave home. I’m not sure whether to applaud a hustle play that worked or suggest Siri have more faith in Alonso; I suspect Siri will give us more exhibits useful for arguing the point.

Baseball being baseball, Siri was also part of the play that turned the game decisively against the Mets, bobbling Alvarez’s drive off the wall before securing it for the throw back to the infield. It was a little thing — just as Arrighetti’s timing on Soto’s grounder was a little thing — but it ate up just enough time for Isaac Paredes to slide safely home instead of possibly being out at the plate.

Little things, whether momentary bobbles or balls scorched along unfortunate trajectories, decide baseball games all the time. That’s another thing you have to relearn in the opening week.

by Jason Fry on 29 March 2025 9:00 am Friday night’s game ended with the sweetest of words. Am I referring to “Mets win” or to “put it in the books?” To quote the tyke from the Internet meme, “Why not both?”

On Thursday the Mets did a lot of things right — hitters refused to expand the strike zone and heretofore suspect relievers pitched with conviction — with the nagging exception of winning the game, as some mean-spirited person ripped out the storybook ending and replaced it with a picture of a sad trombone and a blatted note.

On Friday they once again did a lot of things right, and this time it worked out. The hitters were selective again — Pete Alonso in particular has kept his aggression channeled, avoiding the panicky, I ALONE CAN FIX IT ABs he too often falls prey to. Juan Soto looks, well, Sotoesque, which is wonderful to see up close on a nightly basis. I love the way his plate appearances become these odd running conversations in which he seems to be workshopping his approach with the umpire, the catcher and the hitting coach in his head — and I was predictably overjoyed when Soto hit his first Mets home run, an easy-power line drive off the facing of the right-field deck. That extended a 2-0 Mets lead built with the help of some Houston infield slapstick to 3-0, which didn’t feel like enough but was obviously better than looking uphill all Thursday evening.

On the pitching side, at least for one night Tylor Megill looked like the Tylor Megill that the sabermetrically inclined keep insisting is in there somewhere. Megill trusted his stuff and went after the Astros lineup, keeping his pitch count manageable. It looked like the wheels might come off in the fourth, when Jose Altuve and Isaac Paredes singled to bring up Yordan Alvarez with nobody out. But Megill got Alvarez to fly out to center (a sac fly but nothing more), then struck out Christian Walker and Yainer Diaz with sliders at the bottom of the zone.

That was the kind of inning I was used to seeing get away from Megill — too much nibbling, too little conviction, a mounting pitch count, a ball with too much plate, a dejected trudge off the mound. Not this time — and Megill then navigated the fifth with minimal fuss and deserved better in the sixth. He fanned Jake Meyers to start the inning but watched Meyers scamper to first when the ball kicked off Luis Torrens‘ glove, then got a ground ball from Altuve only to see it elude Francisco Lindor. A little better luck and Megill might have been looking at completing six; instead he had to watch from the dugout as Reed Garrett took over with the game hanging the balance.

Garrett was up to the task, bedeviling the Astros with sinkers, sliders and sweepers to keep the lead at two. “REED FUCKING GARRETT!” I yelled as Garrett marched off the mound, looking like he was yelling something similar.

The Apple TV+ broadcasts aren’t my favorite — the churning probabilities are witless clutter, the fonts all feel too small, and the general feeling is that you’re trapped in some sort of baseball-adjacent app instead of a broadcast. But I do marvel at the fact that you can sync up the picture with either team’s radio feed. That’s a genuine kindness offered to fans, and it actually works — which I mean not in the sense of “the world is so terrible that I’m amazed something functions” but in the sense of “syncing feeds like that sounds super-difficult and the result is flawless, how did they do that?”

Howie Rose and Keith Raad were particularly welcome company because the torpor of spring training had tricked me into forgetting how stressful this all is. First I was barking at Garrett, then I was barking at A.J. Minter (who will probably look out of uniform until late May), then I was barking at Ryne Stanek, and then I was encouraging Edwin Diaz with dread perilously close to the surface, which is a fancy way of saying I was barking at him too. At several points during the barkfest I thought to myself, “My God, it isn’t even April yet.” Like the ad says, ask your doctor if your heart is healthy enough for Mets.

An eye doctor might have been useful too, as the kindest thing one can say about Rob Drake’s strike zone is that it was equitably random. Anything on the outer edge or the bottom border of the strike zone was a coin flip, sometimes not even consistent within at at-bat, but roughly equal numbers of guys in Mets uniforms and Astros uniforms wound up rolling their eyes or huffing in disbelief, so it was more farce than tragedy.

Speaking of uniforms, I hate the Mets’ new road togs. The Mets’ away uniform was both iconic and had a lengthy history; the replacement looks like a knockoff you’d find on Canal Street. The little racing stripes are unnecessary and half-hearted, calling to mind the elusive glories of the de Roulet era, and NEW YORK looks floaty and adrift without the yoke of piping to anchor it. There was no reason to futz with something that worked so beautifully, which I’d thought was something the current regime understood.

Still, win enough games in the new grays and I’ll forgive the unnecessary tinkering. The Mets did that — Diaz was even refreshingly non-terrifying in working a 1-2-3 ninth — and that’s something I could get used to.

by Greg Prince on 28 March 2025 12:14 pm The Mets played to five ties in Spring Training. You can’t do that in the regular season, eight long-ago curfew/rain-related exceptions to the rule notwithstanding,. Therefore, Opening Day 2025 was going to be either a win or a loss, meaning we were bound to process it, in very basic terms, as good or bad.

Loss equals bad, so there ya go. But if you like nuance, it wasn’t that bad. True, a 3-1 loss in the Mets’ first road Opener in an American League park since 2016 — Kansas City, also a loss — isn’t good. Oh-and-one as a record isn’t good. Anticipation resulting in regret isn’t good. Hard to fill the glass to half-full when you’re pouring all factors considered.

But we almost won. That sounds like something you say on behalf of a team that didn’t sign Juan Soto to a record-breaking contract, but the top of the ninth, when one more wave of anticipation built, veered toward pretty good for March 27. The Mets’ offense taking on Framber Valdez was mostly dead all day, if not as dead as on Opening Day from a year earlier (we were one-hit at home). We loaded the bases in the eighth and scored nothing, and that was pretty much our biggest threat to that point.

The ninth, though, felt like the Mets team we loved last September and October, the one we looked forward to through Spring. Versus the accomplished Josh Hader, Starling Marte leads off with a single and Tyrone Taylor follows with the same. Second baseman Luisangel Acuña is up. Acuña as the Opening Day second baseman was a bit of a surprise, as 24 hours earlier it wasn’t clear he’d make the roster. Then again, the alternative, Brett Baty, wasn’t a second baseman a year ago, so either way, it’s not quite how things were being drawn up in Metsopotamian heads. Also, Acuña stood out in the course of the game as the fielder who threw a double play ball past the reach of Pete Alonso for one of the Astros’ three runs. It wasn’t exactly the differencemaker — the Mets had scored none — but it wasn’t inspiring.

What was inspiring was the plate appearance Luisangel proceeded to have against Hader: a dozen pitches, six foul-offs, and, ultimately, four balls. The kid looked like he did when he was brought up to fill in down the stretch last year. He looked like he belonged.

This is where the glass began to approach the half-full mark in earnest. Clay Holmes did not constitute a great advertisement for reliever conversion (he lasted four-and-two-thirds), and there had been a certain crispness lacking all day, but here we were. Bases loaded, nobody out, and any of the next three batters could write a storybook next sentence.

The first didn’t seem likely, but did it seem likely that Hayden Senger would be playing on Opening Day in the major leagues? This is the guy who’s been in the Met system since 2018 and has never exactly hit for much. He was in because Carlos Mendoza opted to shoot his shot pinch-hitting for Luis Torrens with Jesse Winker to lead off the eighth (which didn’t work). All the bench had left was Baty and Jose Siri, neither of them a catcher and, to be fair, neither of them Rusty Staub. Senger versus Hader? As long as he doesn’t hit into a double play, you’ll take your chances.

Senger struck out. Not totally unexpected, and not the worst outcome, because the lineup turns over, and it’s the non-Ohtani MVP of the National League up, Francisco Lindor. Hand Francisco the pen. Any next sentence that includes Lindor is promising.

Sure enough, Francisco drives one to center. Francisco driving one to center has meant some marvelous turns of events in recent memory. A drive to center effectively clinched a playoff berth in Atlanta. Another, a little to right-center, more or less won a playoff series at Citi Field. This drive to center was a flyout, good enough only to push Marte home and Taylor to third. That meant one run, but two outs.

That also meant Juan Soto was coming up with two men on. Soto’s Met debut thus far had been fruitful if not impactful. One single. Two walks. No runs facilitated, but you could say that about every Met batter prior to the ninth. This was a pivot point, however. Not for fifteen years. Just for Opening Day.

Hader had been on the ropes through five batters and twenty-nine pitches. Even Senger didn’t make it very easy on the Astro closer. He seemed gettable, and who better to do the getting than Soto? Sure enough, Juan worked a two-and-oh count, which ascended to three-and-two. What were the odds Hader could sneak something past Soto and end the game?

I imagine one of those gambling apps would have told me in advance. I wouldn’t have bet against Juan, though if I had, I would have collected. Hader threw a slider that tailed away from the plate. Juan guessed wrong on it and swung in desperation. No go. Strike three. Ballgame. Ouch.

Only so much ouch. It was just one game. True, it was the only game we’ve had all year, so the 0-1 record didn’t sit well as I attempted to digest it and dinner. But Juan will get more cracks and probably prevail plenty in comparably deep at-bats. And Holmes wasn’t so out of his element that I don’t believe he’s miscast as a starting pitcher. And hey, how about Huascar Brazoban coming in and shutting down the Astros for two-and-a-third? He wasn’t guaranteed a spot in the bullpen, yet he, along with Danny Young, kept the game viable post-Holmes. And that Acuña time up really was a sight to behold.

Mix in the reasonable conclusion that the Mets won’t post an ohfer with runners in scoring position into perpetuity nor leave ten runners on base for every one they score, and you have to be almost satisfied that the Mets almost came back. And did we mention it’s baseball season again? And that the new road togs looked sharp? It is and they did.

The glass came ever so close to topping the half-full line. Another chance awaits to fill it to brimming.

by Greg Prince on 27 March 2025 1:53 pm It was 34 degrees this morning in New York because it’s March 27, and on March 27, about a week beyond winter, you’re as likely as not to get a very chilly morning. Days with mornings with that low a temperature don’t exactly scream baseball weather.

But the Mets were in Florida for a month-and-a-half (where they compiled an identical number of wins and losses, which seems to be the proper way to handle Spring Training) and now are in Houston, where there’s a retractable roof. So play ball on March 27. And March 28. And so on and so on until the weather is uniformly chilly again, sometime in the heart of fall.

Welcome to the dawn of a new season, even if new seasons oughta start in April. A lot of traditional baseball oughtas get flattened by progress’s army of steamrollers and erased like a blackboard. Houston used to be in the National League, and maybe still oughta. We didn’t used to open seasons let alone play in the regular season versus American League teams, and probably still shouldn’t oughta. No need coming back to the pox on strategy that remains the designated hitter, a quasi-position that spread to the NL for good in 2022 and isn’t going away. “Baseball has marked the time,” Terence Mann declared in Field of Dreams. The time is March 27.

Too soon? Probably. Glad to greet it today? Absolutely.

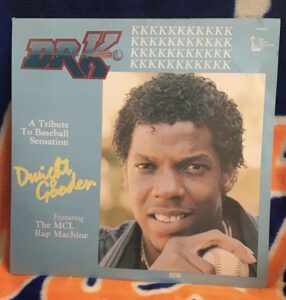

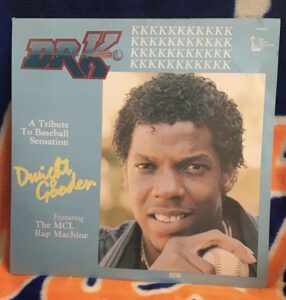

March 27 marks the 32nd birthday of the Mets’ Opening Day starting pitcher, Clay Holmes. Clay Holmes is starting on Opening Day? I used to get hung up on who takes the ball on Opening Day because Tom Seaver takes the ball on Opening Day, and if you don’t have him, Dwight Gooden takes the ball on Opening Day. This Opening Day, the hill is manned by the former closer of a team from another league, someone who’s never been a Met or an ace before. Blasphemy? The Mets’ rotation isn’t deep enough for standing on ceremony. Holmes looked good in Spring and was deployed so his birthday would be his throw day and, besides, starting pitchers don’t go that deep most days, so what the hell? Have a happy birthday, Clay Holmes. Give us five or six innings we can celebrate.

It is also Brandon Nimmo’s 32nd birthday. As soon as Brandon steps into the box score, he reaches the baseline qualification for Hall of Fame consideration. This season is Nimmo’s tenth in the big leagues. That should rate more of a “wow!” than I’m willing to give it. I feel we’ve watched Brandon age in real time, which is to say for a while he was a very young player, then he was a player who was still young but had gained experience, and now he’s a solid veteran in the solid prime of his solid career. We are predisposed to love a lifetime Met. That’s what Brandon has been and will hopefully remain without pause.

Prior to David Wright, Eddie Kranepool was our primary example of a lifetime Met. Came up with us. Stayed with us. Never played for anybody but us. Plus he was Eddie Kranepool. We lost Eddie last September. Given his eighteen seasons — which included an Opening Day start in right field at the age of 18 on April 9, 1963, at the Polo Grounds, along with six more at first base spanning 1965 to 1977 — our memories of the Krane should and will live on without much prompting. A sleeve patch affixed to our jerseys will underscore for us Eddie’s eternal Met presence in 2025. A check of Baseball-Reference reminds us Eddie was usually ready for the season to start every season, whether he was starting or not. Mr. Kranepool, from the year he was a veritable kid to the last year he played as a grizzled vet, in 1979, batted .295 in April, his best month hitting. He didn’t have any at-bats in March. Baseball didn’t commence so early back then.

Since last summer, which was winding down when we said goodbye to Ed — having already bid adieu in 2024 to Bud Harrelson, Jim McAndrew, Pat Zachry, Jerry Grote, and Willie Mays — too many other Mets have passed away. They won’t get patches, because sleeve space is limited, but let’s remember them for a moment. Since last summer, which was winding down when we said goodbye to Ed — having already bid adieu in 2024 to Bud Harrelson, Jim McAndrew, Pat Zachry, Jerry Grote, and Willie Mays — too many other Mets have passed away. They won’t get patches, because sleeve space is limited, but let’s remember them for a moment.

Wayne Graham, our infielder from 1964 who went on to a long and distinguished college coaching career at Rice University (one of his charges was eventual Met Phil Humber);

Ron Locke, who pitched for us in 1964, something I learned when I picked up his 1965 baseball card in 1975 at the first baseball card show I ever attended;

Jack DiLauro, whose contribution to the 1969 Mets I wouldn’t have known about from the front of the 1970 baseball card I pulled from a pack as a kid because he’d been traded over the winter and his cap was blank (I had to flip it over to grasp he’d been one of ours);

Bob Gallagher, the 1975 Met outfielder who we received in exchange for another Miracle man, Ken Boswell;

Lenny Randle, one of the few Met reasons to have felt good about 1977;

Mark Bradley, the toolsy 1983 Mets outfielder who holds the distinction of being the first Met I ever photographed with my own camera, on a rainy Saturday afternoon in St. Petersburg (the game was cancelled, but I know I have the picture somewhere);

Rickey Henderson, the leadoff man of leadoff men who requires no reintroduction from his eventful days with us in 1999 and 2000 (the A’s, wherever they play now, will wear a patch in his honor);

Felix Mantilla, who lasted all of 1962 as an Original Met and ninety years in all;

Tommie Reynolds, an infielder-outfielder who crouched behind the plate in a classic and absurd emergency catcher situation in 1967;

Mike Cubbage, a Met player for one season, in 1981 (he homered for us in his final MLB AB), a Met coach under five different dugout administrations, and about as interim as an interim manager could be, steering the ship home for the final week of 1991 before returning to assisting;

and Jeff Torborg, a well-regarded baseball man whose best work probably wasn’t as Met manager in 1992 and 1993, but when he passed, I read nothing but kind words from those who knew him, so maybe it just wasn’t the right fit here.

Going back prior to last summer, in May, Bill Murphy, referred to in his playing days as Billy, passed on. Murphy was a Rule 5 player who stuck through 1966 in order for the Mets to hold on to him. I began to research his story and found some fascinating threads, but never got around to weaving them together. I hope to give Bill his due before long.

For now, thanks to all the Mets who’ve come before, a sum that measured 1,252 overall (Ashburn to Acuña) through 2024. The all-time quantity can increase by as many as seven while the Mets are in Houston, as the first 26-man roster of 2025 includes Holmes; similarly reoptimized starter Griffin Canning; backup catcher/Whole Foods utilityman Hayden Senger; childhood Mets fan who grew up to relieve for his favorite team Max Kranick; defensive whiz and pun waiting to be run into the ground Jose Siri; former division rival A.J. Minter; and somebody named Juan Soto. More will emerge, but these are the half-dozen poised to make their Met debuts late this March, and I look forward to welcoming them. Especially that Soto fellow.

Fitting enough we’re packing seven potential first-time Mets in Houston as this is the first Opening Day that has pitted the Mets versus the Astros. One Shea Home Opener (2005, this blog’s first April and that ballpark’s fourth-from-last), but nothing that led off a season. We each began life as expansion franchises in the same April, but not only have we never been until now each other’s first opponent, we’ve competed against one another in a season’s first week only six times, no such series more recent than 1994. In 1968, in our fifth game of the year, we and they did play 24 innings. The Astros scored once, the Mets not at all; the 1968 Mets lacked the equivalent of Lindor, Soto, Alonso, Nimmo, and Vientos to get things going on the offensive foot. Drop that crew into 1968, and it might not have become known as The Year of the Pitcher…at least in theory.

All that has been theoretical about this club leading into 2025 is about to turn actual. All the excitement a lot of us have been feeling is about to be put on the line. I’ve been up for other seasons to start — all of them, really — but this one has a legit April-in-March sense to it. Like it really couldn’t wait another day. Good thing it’s arriving when it is. All that has been theoretical about this club leading into 2025 is about to turn actual. All the excitement a lot of us have been feeling is about to be put on the line. I’ve been up for other seasons to start — all of them, really — but this one has a legit April-in-March sense to it. Like it really couldn’t wait another day. Good thing it’s arriving when it is.

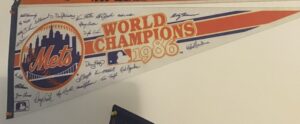

by Greg Prince on 24 March 2025 6:24 pm Baseball seasons run only so many games and so many months long. Yet if you’re lucky, they last forever. Also, if you’re a little unlucky after the fact, they stick around without a peer emerging to join them where you left them. The season that lands at No. 3 among MY FAVORITE SEASONS, FROM LEAST FAVORITE TO MOST FAVORITE, 1969-PRESENT but surely gave me my hands-down favorite result did its best to set itself apart from anything that could have come after it. As far as I’m concerned, it’s done everything it’s had to do since its moment in the spotlight, even if it’s had to carry on with a status we never dreamed it would maintain for decades.

When it was coming along, we had dreamed only of the season it would give us when it was giving it to us. Boy, did it deliver.

3. 1986

It’s late one morning in May. I look up at a clock. It’s around 11:30. All I can think is, “Eight hours until the Mets game tonight.”

That was 1986 to me while it was going on. Watching the clock and waiting for the Mets equaled winning time. It occurs to me I didn’t have a lot else going on in my life that didn’t involve counting down to tonight’s game. It wasn’t an ideal route to personal fulfillment, waiting on a team of total strangers to report to work and make me ebullient, but I have no baseball-related regrets. I couldn’t stand for time to stand still because I wanted the game to get here. When the game got here, the Mets would probably win it, and by probably, I mean almost certainly. Once that game was won, I wanted another. The hours between wins dragged because the hours while the games were being won were, per the recording talents of George Foster, Metsmerizing.

With hindsight, maybe we’d appreciate those hours dragging. Don’t go away so quickly, season that had no Met precedent and has produced no worthy Met successor! What Mets fan wouldn’t want to continue living inside the baseball world that was 1986? If every season could be 1986, I wouldn’t argue with the outcome. But every season can’t be 1986. It would be too much to ask, maybe too much to take. Besides, how would you be able to differentiate it from all the other seasons? With hindsight, maybe we’d appreciate those hours dragging. Don’t go away so quickly, season that had no Met precedent and has produced no worthy Met successor! What Mets fan wouldn’t want to continue living inside the baseball world that was 1986? If every season could be 1986, I wouldn’t argue with the outcome. But every season can’t be 1986. It would be too much to ask, maybe too much to take. Besides, how would you be able to differentiate it from all the other seasons?

In the great flight of Mets history, nothing else looks like 1986, and nothing else competes with 1986. That the Mets were celebrating their 25th anniversary all year brought the poles into stark relief (the kind Casey Stengel was usually saddled with in 1962 as soon he removed his starting pitcher). The full Met CV —108 regular-season wins; a divisional margin of 21½ games beyond any rival’s reach; an NLCS that couldn’t have been tighter for six games (but we won four of ’em); and a World Series that teetered on defeat but literally couldn’t be lost — has no remotely Metropolitan doppelgänger. There have been occasional subsequent invigorating roughshod rides through spring and summer that ultimately sagged in fall. There had been one previous world championship, but consensus pegs that one as a surprise for the ages, maybe the surprise for all ages. The 1986 Mets’ final acts versus Houston and Boston would have fit neatly in any highlight reel produced in miraculous 1969 or nearly as unbelievable 1973, but where they led was no stunner once you remembered these were the 1986 Mets. The 1986 Mets existed to win everything in sight, to take care of business like nobody’s business, with dominance and prominence, to say nothing of verve and panache.

That they did. Every day had you sneaking peeks at nearby clocks in anticipation. Looking forward to first pitches and last outs was how we lived. The Mets we rooted for were far and away the team in baseball. It took a little while to sink in that this was us. Eventually, we stopped pinching ourselves.

Yeah, we had a team like that once. Just once. Requesting another world championship after nearly forty years doesn’t seem greedy, but I doubt there can ever be another 1986 in this lifetime. My lifetime has encompassed one 1986. It oughta sate me. It makes me want a sequel. Sequels rarely measure up to the original, but I’d be willing to try another year like it on for size.

I wish us good luck casting the parts.

PART I — BECOMING THE 1986 METS IN 1986

Taking the long view, you’re usually safe starting with January 24, 1980, and the sale of the downtrodden Metropolitan Baseball Club of New York, Inc., to Doubleday & Company, fronted by Abner Doubleday descendant Nelson Doubleday, with Fred Wilpon on board holding a minority stake. They talk about reviving National League baseball in New York. They are greeted as liberators. They hire Frank Cashen, the GM in Baltimore from when they were a powerhouse (except for a five-game series in October of 1969), and Cashen goes to work. It doesn’t show in the standings for several seasons, but the farm system gets replenished. It begins to bloom. The crops are transported to New York. A manager from the Met minor leagues — also with Oriole pedigree — is promoted. Davey Johnson leads a young, talented team that has been augmented by a couple of imported superstars out of the utter wilderness and into serious contention. As 1986 arrives, the Mets are pretty much right there to greet it and grab it.

Taking the granular view, I’d say the 1986 Mets began to reveal they had become The 1986 Mets in boldface type on the dreary Monday evening of April 21, a rainy night in Flushing when paid attendance for the game against the Pirates (in those days actual turnstile count) was the lowest it would be all year. It was also the last time the Mets would enter action behind Pittsburgh in the NL East. Not that that was the yardstick anybody planned on using to measure 1986. Still, the Buccos, otherwise experiencing their own franchise doldrums, were 6-2. The Mets were 5-3. The Mets had been 2-3. Won their first two. Lost their next three. In retrospect, the first week of the season was the opening minutes of a first-round high-seed/low-seed March Madness matchup. The high seed comes out cold. The low seed hits a few baskets. Fans of the true blue blood programs understand there’s a long way to go in this game, not to mention tournament. Just give it a few more minutes.

Orange and blue blood didn’t necessarily circulate to our brains that way. Every game was precious. Every opponent was dangerous. The Pirates? The Pirates, coming off 104 losses the year before, had taken eight of eighteen from us, including three of six in September when us winning every game was imperative. We had built a one-game lead on St. Louis on September 12 after we bested them two out of three at Shea, yet finished three games in back of them. Down the stretch in 1985, the Cardinals dusted their cursed red feathers off and returned to winning. We futzed around and found out that you had to beat the Pirates and Cubs and Expos and Phillies, too. Gathering even a touch of panic at the idea of being 2-3 on April 14, or feeling a scintilla of anxiety that we were sitting in back of Pittsburgh starting play on April 21, required no hindsight to negate. Of course it was silly.

Or was it? We hadn’t learned how not to be nervous yet. Examining our roster and simply relaxing didn’t come easily. Not after coming close in 1984 and coming even closer in 1985. April wasn’t only close to March. It still carried the whiff of the near-misses of the previous two years. A certain strain of Mets madness infiltrated April’s air.

Then, on April 21, the Mets pulled into a second-place tie with the Pirates. Again, not the goal of the season whose competitive contours were still gestating, but significant for how we got there. The Mets trailed, 2-0, after a half-inning; 4-2 in the middle of the eighth; and 5-4 heading to the bottom of the ninth. Two comebacks, each on two-run homers off the scalding bats of demonstrative teammates — Gary Carter (.351) in the third, Ray Knight (.391) in the eighth — were poised to go to waste. Or would have in another year.

This wasn’t another year. This was 1986. This was Lenny Dykstra singling to lead off the home ninth, Kevin Mitchell bunting him to second, Tim Teufel doubling Dykstra home to tie the score at five apiece, and, within two batters, Carter driving home Teufel. Mets win, 6-5, in their first walkoff triumph of the young year. Now tied with Pittsburgh in the standings, the Mets would sweep the two-game set the next night; the season series versus Pittsburgh would turn out Mets 17 Pirates 1. No more futzing around. The Mets were on a five-game wining streak. An off day Wednesday, combined with a Cardinal loss, allowed us to nose into first place all by ourselves as we alighted at Busch Stadium for four critical games, Thursday through Sunday. Critical? In April? After last October, and our winning only two of three when we required one more in St. Louis in that season’s penultimate series, yes.

By the end of Sunday the 27th, once ex-Met Clint Hurdle lofted the last of new Met Bobby Ojeda’s pitches into star Met Darryl Strawberry’s glove, the Mets completed confirming they were The 1986 Mets. It hadn’t been a week since we trailed the Pirates, but now we led the team we had to lead by four-and-a-half games. We swept the Cardinals. I mean, we swept the hell out of the Cardinals. Thursday’s affair was another “nope, not this year”-style comeback, featuring Howard Johnson’s game-tying two-run homer off Todd Worrell in the ninth. Friday’s game was a pure whitewashing, Doc Gooden going the distance in a 9-0 breeze. Saturday’s game ended in one of those ninths that didn’t get away, with a 4-0 first-inning lead staying undisturbed until the final inning, when an eerily familiar Cardinal rally (three singles, one double and a sac bunt) fell short as Wally Backman turned the clutchest of 4-6-3 DPs. And Sunday’s game was the kind of coup de grâce that The 1986 Mets were honing into their specialty. Ojeda, picked up in an offseason trade we had no idea would bring us our winningest pitcher, threw a complete game. Rookie outfielder-third baseman Kevin Mitchell filled in at shortstop because Davey decided he could play it just fine. Mitchell homered, as did Teufel, the righthanded second baseman the Mets lacked in 1985 (Backman could do everything you wanted except handle lefties). These three added to Doc and Darryl and Keith and Gary and everybody else? The Mets were clearly improved. The Cardinals were clearly done.

The Mets left Missouri on a nine-game winning streak that grew to eleven. After a lone loss in Atlanta, they won another seven straight. The 2-3 Mets of April 14 morphed into the 20-4 Mets of May 10, a top seed turning all prospective NL East Cinderellas into pumpkins. Nobody in the division loomed as very concerning. Now and then, the Expos would present a theoretical obstacle — they drew as close as 2½ out on a West Coast afternoon in late May, and took two of three from us twice in June — but nothing insurmountable. We were playing from ahead in the standings from the instant we took the field in St. Louis on April 24, far ahead soon enough.

My favorite quote of the season came not from a Met, but from somebody who used to be one. In that second Expo series, at Shea, Montreal had pulled to within eight games of us after winning the first two. This was June 25, with well over a half-season remaining. The second-place Expos had their eyes on not just a sweep, but a statement. Instead, they saw a 2-0 lead in the Wednesday matinee finale turn into 5-2 loss. Instead of making up enough ground to get to within seven games of the Mets, they had fallen back to nine.

“Nine out is so damn close to ten,” their shortstop Hubie Brooks admitted after the loss. “Seven out is so damn close to five. I think we did good, but it’s too bad we couldn’t be better than nine out.”

I read that and thought, that’s it. That’s the concession speech. The Mets had played 68 of 162 games, and they had essentially clinched their division. To celebrate, they built a new eight-game winning streak. I guess this is where the Mets left zero doubt about being The 1986 Mets. Microspells of not stomping on opponents were capable of raising Mets fan eyebrows, because, well, our eyebrows hovered over eyes that had seen first-place Met clubs not finish on top in ’84 and ’85. You didn’t fully shake off your tendency to doubt, because you lived the previous years. I read that and thought, that’s it. That’s the concession speech. The Mets had played 68 of 162 games, and they had essentially clinched their division. To celebrate, they built a new eight-game winning streak. I guess this is where the Mets left zero doubt about being The 1986 Mets. Microspells of not stomping on opponents were capable of raising Mets fan eyebrows, because, well, our eyebrows hovered over eyes that had seen first-place Met clubs not finish on top in ’84 and ’85. You didn’t fully shake off your tendency to doubt, because you lived the previous years.

But, really, you didn’t have any doubt.

PART II — BEING THE 1986 METS IN 1986

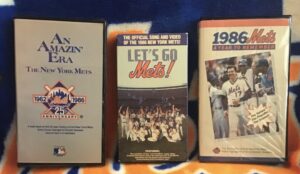

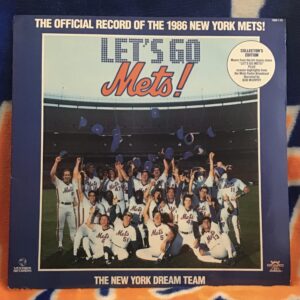

The above is the on-field stuff. The substance. What separates The 1986 Mets in the mind’s eye is the flair. The fights. The twelve-inch dance mixes. The video productions. The curtain calls. The high-fives that would send the hands of mere mortals flying into Field Level. The aura. The top of the order. The heart of the order. The bench. The rotation. The back end of the bullpen. The speed. The power. The savvy. The rally caps. The hot foots/feet. The woman in the wedding dress brandishing a MARRY ME LENNY placard in the stands. The women and everything else we didn’t know about until the books and the documentaries came out much later. The best action in any sport being analyzed by the brightest mind in any booth, Tim McCarver’s. Ralph Kiner was in fine fettle, too, and Steve Zabriskie provided understated balance to McCarver’s brilliance and Kiner’s gleam. Bob Murphy was atop his game on WHN, paired with a worthy partner in Gary Thorne. Sure, some nights you had to put up with Fran Healy on Sportschannel, and no, they never did rustle up a dependable lefty specialist. Honestly, though, if those are your biggest problems, you don’t have problems.

I suppose the rest of the league didn’t love how the Mets took one game at a time and framed each as museum-quality. The 1986 Mets really loved being as good as they were. They didn’t act as if they’d been there before. Keith Hernandez had been to the mountaintop, as a Cardinal in 1982. Mex’s intensity was different from Kid’s; Carter blew the roof off open-air stadia with his exultations. Nobody besides Keith had won a World Series. These guys were all hungry to be the best and didn’t mind reveling in their status as the provisional kings of any mountain they scaled. It was infectious from a distance. We hadn’t made the playoffs in thirteen years. We had never carried around baseball’s best record or biggest lead day after day, week after week. They were excited? We were excited! I suppose the rest of the league didn’t love how the Mets took one game at a time and framed each as museum-quality. The 1986 Mets really loved being as good as they were. They didn’t act as if they’d been there before. Keith Hernandez had been to the mountaintop, as a Cardinal in 1982. Mex’s intensity was different from Kid’s; Carter blew the roof off open-air stadia with his exultations. Nobody besides Keith had won a World Series. These guys were all hungry to be the best and didn’t mind reveling in their status as the provisional kings of any mountain they scaled. It was infectious from a distance. We hadn’t made the playoffs in thirteen years. We had never carried around baseball’s best record or biggest lead day after day, week after week. They were excited? We were excited!

Put another way, we had the teamwork to make the dream work.

Dissent could be discernible from an odd corner or two. For example, New York’s leading aficionado of underdogs Jimmy Breslin, who helped make the Original Mets as famous as could be for chronic failure via Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game?, registered a vote of protest against The 1986 Mets’ rampaging success. “[T]his year,” Breslin wrote in the News in August, “with the Mets winning so many games, it is embarrassing, for they resemble the old Yankees.” A month later, as the Mets closed in on their inevitable mathematical clinching, he expounded on the theme:

“When I sit alone, of course, I fanatically root for the Mets to lose. What do I need with a boring winner, with a first baseman, Hernandez, whom I don’t like personally but who can field the bunt and start a double play by throwing the lead runner out at third. My sports love still is the 1962 Mets, who lost 120 games, and who had as a first baseman, Marvin Throneberry. I still could see Throneberry in my mind on Friday night, Marvin Throneberry bent over, glove ready, eagerly looking at a ground ball, his mouth wide open, ready to bite the ball if it took a hop, eagerly watching, watching, watching as the ground ball went under his glove and through his legs and into right field.”

Mass huzzahs for the modern-day Mets ensued despite the columnist’s protestations. In the making-of video that accompanied the music video the Mets made in tribute to their awesomeness (because how else were you going to know the video had been made?), perhaps a member of Twisted Sister who wasn’t Dee Snider put it best: “Isn’t it nice to turn on the television and not have to worry that they may lose this evening — they’re still twenty games ahead! Think about that, they’re twenty games ahead, even if they lose once in a while. That’s what you call luxury! That’s almost as good as having a rent control apartment in Manhattan.” Mass huzzahs for the modern-day Mets ensued despite the columnist’s protestations. In the making-of video that accompanied the music video the Mets made in tribute to their awesomeness (because how else were you going to know the video had been made?), perhaps a member of Twisted Sister who wasn’t Dee Snider put it best: “Isn’t it nice to turn on the television and not have to worry that they may lose this evening — they’re still twenty games ahead! Think about that, they’re twenty games ahead, even if they lose once in a while. That’s what you call luxury! That’s almost as good as having a rent control apartment in Manhattan.”

Let’s Go Mets Go, indeed.

PART III — STAYING THE 1986 METS IN 1986

One-hundred eight wins weren’t going to amount to a pitcher’s mound of beans if The 1986 Mets didn’t deliver in October. I don’t live in a world where they didn’t beat the Astros or the Red Sox, so I don’t know how I’d look back on them had they not brushed aside the best efforts of Bob Knepper and Dave Smith in Game Three of the National League Championship Series; or if Darryl Strawberry hadn’t connected off Nolan Ryan in Game Five, leading eventually to Gary Carter avenging Charlie Kerfeld in the twelfth inning; or if they hadn’t won…deep breath…Game Six. Ohmigod, Game Six. Ohmigod, and I don’t mean OMG. If anybody thought the Mets made 1986 look too easy for six months, Game Six in the Astrodome, culminating in a 7-6 win in sixteen innings and, oh yes, the National League pennant, reminded one and all that this team constantly created laurels rather than sat on them.

It could have gone the other way. The Astros could have held on in Game Three or Game Five or Game Six. They could have forced Game Seven, with Mike Scott on the hill, the Mets having every chance to look like fools swinging and missing at the ex-Met’s totally legitimate split-finger fastball whose movements weren’t enhanced by any foreign object, no sir. Or they could have sapped Scott of his strength and won the flag in seven. I wouldn’t have put anything past The 1986 Mets while they were being The 1986 Mets.

Not that I was pining to find out. Mets in six in the NLCS was sufficient. Bring on Boston!

Boston was brought on with a bit much velocity. The Mets endured the last of their Astrodome marathon on Wednesday, October 15. That gave them time to fly home (while tearing apart their airplane), rest up, work out, and, apparently, not be ready to play optimal ball on Saturday, October 18. Ron Darling pitched swell in Game One of the World Series. Bruce Hurst was a little sweller and won, 1-0. The next night, the hyped Dwight Gooden-Roger Clemens duel faltered on both ends, but faltered more for Gooden. A lot more. We lost, 9-3. Suddenly, the best team in the sport was down zero games to two in a best-of-seven situation.

What could have happened against Houston but didn’t was now in the process of happening against Boston. Then came Games Three and Four, and no frigging way was it going to happen. We won Game Three with ease (7-1), Game Four with essentially the same (6-2). Now we just had to win two out of a possible three. You’re gonna tell me we’re not gonna win two out of a possible three? That’s all we did all year. Two out of three fifty-four times in the regular season. Two out of three twice against the Astros. Hurst, the new Scott in practicality if not sandpaper, shut us down in Game Five, 4-2. So now we had to go back to Shea and win two of two. Shoot, we can win two of two.

First, however, we had to win one of one, because we trailed the World Series three games to two, meaning we faced a Game Six that literally could not be lost. Another Game Six? Didn’t we just do this in Houston? That was basically the greatest baseball game you thought you’d ever see, but it was ten days and a postseason lifetime ago. Plus, Scott or not, we’d led that series three games to two. This next Game Six had no hypothetical give to it. Could you imagine these robust, indefatigable, making-of-video-making Mets going down in six games to the Boston Red Sox? You didn’t have to imagine. It was happening in front of us for four-and-a-half innings, Red Sox 2 Mets 0, some dude parachuting from out of the sky, 24-game winner Clemens riding a no-hitter. Doubt was permissible in infinitesimal doses. We tied it in the fifth (phew!). We gave a one-run lead back in the seventh (damn!). We retied it in the eighth (yay!). We had a genuine chance to win it in the ninth, but didn’t (hmm…). We gave up two runs in the top of the tenth.

Expletive implied.

Suffice it to say, the bottom of the tenth of Game Six of the 1986 World Series took care of itself. The Red Sox led, 5-3, with two outs and no Mets on base. DiamondVision flickered discouraging word that it was all over. Yet The 1986 Mets, who’d already revealed and confirmed themselves The 1986 Mets, still maintained one out with which to play and a veritable Baseball Bugs conga line of individuals capable of making the most of a little leeway. Gary Carter singles. Kevin Mitchell singles. Ray Knight singles. A run scores. The Red Sox lead, 5-4. Mitchell is on third. Knight is on first. Former Met Calvin Schiraldi, the current Red Sox closer, is replaced by Bob Stanley, the Red Sox’ former closer. Mookie Wilson, drafted by the Mets on June 7, 1977, eight days before Tom Seaver (a current Red Sock) was traded, is up. Stanley throws a wild pitch. Mitchell dashes home. The game is tied. Knight moves up to second. Wilson continues to be up.

At this moment, within this at-bat, the World Series literally couldn’t be lost. Carter, Mitchell, Knight, Schiraldi, Stanley and perhaps catcher Rich Gedman saw to that. It had all been on a beautiful, silver platter for the Red Sox, and the Mets took it away. Maybe in the eleventh inning, the situation would change, and the Mets literally could lose. But not in the tenth.

Wilson fouled off everything until he didn’t. His fair contact — a little roller up along first, per Vin Scully — was adequate for no more than a sprinter’s chance to beat out an infield base hit. If Mookie made it to first base safely, Knight would be on third, and Howard Johnson would be up. You couldn’t ask for more than that in the nanosecond you watched Mookie’s grounder trickle.

A nanosecond later, you got more than you asked for. You got the Red Sox’ first baseman, Bill Buckner, playing the part of Jimmy Breslin’s beau ideal of a first baseman, Marv Throneberry. The ground ball went under his glove and through his legs and into right field.

Mets 6 Red Sox 5. Series tied at three. Both teams have a chance to win this thing in seven.

But the Mets are going to win it. The Red Sox sure as hell aren’t going to. They take an early 3-0 lead off Darling, and Hurst holds us scoreless through five, but we’re The 1986 Mets. Fueled particularly by that trademark Mex brand of intensity (a tide-turning two-run single off Hurst after his brother gives him the high sign from the stands), we score three in the sixth. Then, two in the seventh, with Knight socking the tiebreaking home run over the wall. Boston gets two back in the top of the eighth, and that should make us uncomfortable, but nah. The Mets add two in the bottom of the eighth to make it 8-5. Jesse Orosco is on, just as he was in Houston when brass tacks were everywhere. He barely survived an Astro onslaught under the Dome. At Shea, nobody has to threaten him to throw nothing but sliders. He’s got this. So do Carter and Hernandez and Backman and Santana and Knight and Wilson and Dykstra and Strawberry. Davey has his platoons and his hunches, but here and now, you get the feeling he has precisely who he would want on the field to win a World Series.

Not that you wouldn’t trust any of the understudies right now. Everything about The 1986 Mets was, as Billy Joel reminded us regularly as summer seeped into fall, a matter of trust. Hearn the good-natured reserve. Heep the old pro. Mazzilli in his surprise second term. Elster, fresh from the bushes, smooth in the field. Teufel, not as much of a dirt-eater as Backman at second, but absolutely the slugger who walked off the Phillies in extras with a grand slam. Mitchell, brandishing numerous gloves to go with a potent bat. HoJo, who not only mortally wounded Worrell and the Redbirds in April, but won that crazy July game in Cincinnati, the one in which, as Breslin noticed, Hernandez fielded the bunt and started a double play by throwing the lead runner out at third…which happened to be manned by Carter. Howard Johnson had three 30-30 seasons in his near future. On the days and nights Mitchell didn’t start (85 games in all), the bench included 1989’s National League MVP. Come to think of it, on the nights Dykstra didn’t start (64 games in all), it had the guy who would in 1993 place second to Barry Bonds for Most Valuable honors. Deep depth abounded just about everywhere you surveyed.

Darling (15-6) and McDowell (14-9, 22 saves) weren’t at their sharpest in this game, nor Gooden (17-6) in this series, but we wouldn’t be The 1986 Mets without any of them. And how about El Sid (16-6) holding the potentially crumbling fort in crucial middle relief? How about Ojeda (18-5) starting both Game Sixes and writing a new definition of withstand? How about Aguilera, if you allow yourself to look past the leadoff home run he allowed Dave Henderson in the tenth inning of Game Six? Aggie won ten games as the rotation’s forgotten man and kept Game Six of the NLCS scoreless for the three innings bridging Bobby O and Roger McD. How about Doug Sisk, despite the slump he sunk into in July of ’84 and seemed to come out of only intermittently? Sisk faced 312 batters in 1986 and gave up no home runs — no Met pitcher has come away from more encounters with batters in any season gopher-free. Hey, how about Randy Niemann, the personification of not the answer in lefty specializing? He did win his one start, in an August doubleheader, and Frank Cashen himself singled him out as a premier sprayer of champagne in Houston. Darling (15-6) and McDowell (14-9, 22 saves) weren’t at their sharpest in this game, nor Gooden (17-6) in this series, but we wouldn’t be The 1986 Mets without any of them. And how about El Sid (16-6) holding the potentially crumbling fort in crucial middle relief? How about Ojeda (18-5) starting both Game Sixes and writing a new definition of withstand? How about Aguilera, if you allow yourself to look past the leadoff home run he allowed Dave Henderson in the tenth inning of Game Six? Aggie won ten games as the rotation’s forgotten man and kept Game Six of the NLCS scoreless for the three innings bridging Bobby O and Roger McD. How about Doug Sisk, despite the slump he sunk into in July of ’84 and seemed to come out of only intermittently? Sisk faced 312 batters in 1986 and gave up no home runs — no Met pitcher has come away from more encounters with batters in any season gopher-free. Hey, how about Randy Niemann, the personification of not the answer in lefty specializing? He did win his one start, in an August doubleheader, and Frank Cashen himself singled him out as a premier sprayer of champagne in Houston.