The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 28 September 2010 7:50 am It’s a Sunday afternoon in September 1996. I’m at Shea Stadium with my best friend Chuck, diehard Met sympathizer, but better described as a bandwagon rider in terms of his actual Met fandom. Yet in September 1996, there is no bandwagon. There’s just me guilting him into joining me for a game against the Braves. Paul Wilson pitches well. T#m Gl@v!ne pitches better. Mets lose, 3-2.

Still, a nice afternoon at the place where I always want to go, a place to which I have no idea how much I’ll be going over the next dozen seasons. In 1996, a trip to Shea is still just a little bit of a novelty for me — only eight times all year, the last time I’ll go less than ten. It’s too special to leave so soon so late in this mostly lost season. I’m here; my best friend is here; “our” team is slipping away. Mark Wohlers comes on to strike out Andy Tomberlin and ends the game. But our day lingers just a little longer. Chuck and I both understand a season requires savoring, even if it’s the 1996 Mets’ season.

So we sit for a couple of minutes after the final pitch in our Mezzanine seats, resigned to baseball winding down and summer winding down and us getting a little older. We’re mostly taking one last long look around.

We’re interrupted. It’s an usher. “C’mon,” he says. “You guys gotta go.”

Huh? It’s no more than two minutes since Tomberlin whiffed. There is no night half of a doubleheader coming up, no concert, no soccer match, no Bar Mitzvah. Nobody’s tearing the place down for another dozen years. Yet there’s no time to dawdle. Shea Stadium must be vacated at once.

Jesus.

***

It’s a Saturday night in August 2010. I’m at Citi Field with my wife and our dear friends the Haineses. Jim’s been disgusted with the Mets for all nine years I’ve known him, which is to say he’s as big a fan as I am. We’ve just watched The Last Play at Shea, a movie I’ve now seen three times, the first two at the Tribeca Film Festival in April. After the second viewing there, I suggested to Dana Brand (who, like me, appears in the film) that they really ought to show this at Citi Field. From my lips to somebody’s ear…or it was just too obvious an idea not to be hatched in multiple minds.

The movie’s over. It’s been roundly enjoyed by all among us taking it in for the third (me), second (Stephanie) or first (Jim and Daria) time. As with every movie I’ve ever gone to see, there’s a bathroom scene as soon as it’s over. Jim and I go to the men’s room on the third base side of the Excelsior level, Daria and Stephanie to the ladies’. Stephanie’s a little slower to come out than the rest of us, so the other three among us do what three people do after a movie, no matter where it’s projected — we wait nearby for our fourth.

It’s no more than a couple of minutes that we’re standing and chatting, the personification of minding our own business, when a Citi Field guard comes over to us and tells us we have to move along. He addresses us as if we are teens loitering outside the 7-Eleven, as if standing around a stadium that is otherwise filing out is our nefarious goal, as if we are planning on hiding inside the Caesar’s Club until the Mets return home from their seven-game road trip.

I tell him we’re waiting for my wife to come out of the ladies room.

Oh, he said, that’s OK, and walks away.

Jesus. The wrong things never change, do they?

***

Shea Stadium was emptied for good two years ago today, but part of me has never left it. Part of me never will. Part of me only recently stopped dwelling daily on the last time I moved along, on September 28, 2008. I’ve wanted it to exist again almost every day since then. I’ve wanted it to be tangible. And I’ve wanted it in Flushing.

I understand that’s impossible, but I’ll take what I can get. The Last Play at Shea, playing at Citi Field, was about all I could hope for.

Citi Field and Shea Stadium never felt closer than on the night of August 21. The showing of the movie ensured that, but even more comforting were the trivia questions that were asked to keep us entertained before the lights went down. They were all about Shea Stadium. Alex Anthony was compelled to keep repeating the phrase: “Shea Stadium.” It felt so good to hear those words again in something approaching an official capacity in this space.

On August 21, Shea was an honored guest at Citi, no longer shamed with nonperson status at Orwellian Park. For a couple of hours, I wasn’t sitting in the anti-Shea of 2009, a structure erected with every intention of blotting out every memory of the previous 45 years. I was sitting in the place that came after Shea — its successor, not its replacement.

There’s a great deal of difference.

***

The movie starts with an overhead shot of Shea Stadium. And a roar goes up, at least as voluble as anything greeting, say, Jason Bay in the course of this baseball season. The Mets are in Pittsburgh tonight. For the first time I can recall, NYM is on the out-of-town scoreboard. When a couple of highlights are shown before the movie starts, there is approval that the Mets are winning. The crowd is a Met crowd as much as it’s a Billy Joel crowd (couldn’t definitively say the same, sadly, on the first night Billy played Shea in July ’08). But what this really is is a Shea crowd. Tom Seaver and Keith Hernandez and Mike Piazza and Bill Buckner all receive hearty applause. So does Billy Joel, of course, though Pete Flynn might be the bigger rock star here. But nothing makes people as happy here as seeing Shea Stadium go above the marquee inside Citi Field. There was some kind of hunger for this moment, for this validation. I’m convinced of that.

With the Mets away, the movie would play. The 2010 version of Citi Field learned a few things after 2009. I’m convinced of that, too. The greatest lesson is on display in the New York Mets Hall of Fame & Museum that now anchors the Jackie Robinson Rotunda. The spirit of Shea informs just about everything in there. It has to. All but three of previous Met years happened there. The Shea Bridge, too, is a grand embellishment of Citi Field’s sophomore season. Its stated purpose (besides connecting the Verizon Studio to the Catch of the Day) is honoring Bill Shea, but the plaques on either side of it have chiseled into them an image of his stadium, not his face. The bridge debuted without a name when the stadium opened. It took a year to do the right thing, same as it did unveiling the museum.

The Mets take their sweet time on a lot of matters that would make them look and feel better if they got to them sooner. Reviving actual Hall of Fame inductions took eight years. When the first Citi Field class of Cashen, Johnson, Gooden and Strawberry made their acceptance speeches, the phrase “Shea Stadium” was uttered over and over. That’s where those guys’ triumphs took place, just as they did for Seaver and Hernandez and Piazza and Joel and John, Paul, George and Ringo, and, to whatever limited extent they achieved them, the Fab Three of Beltran, Reyes and Wright.

***

When I filmed my interview for The Last Play at Shea during Shea’s last week, I was asked what the stadium meant to me. I said Shea Stadium had forever been my “destination”. That was the word that came to me in late September 2008. It was always about going to Shea or wanting to go to Shea or planning to go to Shea or yearning to go to Shea. I started going to Shea so often at some point in its final decade that it stopped amazing me that it literally was my destination on a regular basis. It was all coming back to me by the last week of its existence. There’d be no more going to Shea Stadium. I would no longer have my destination.

That didn’t get used in the movie, but I thought of it again after seeing the film a third time. Citi Field seamlessly (albeit with a little psychic kicking and screaming) has taken over as my destination, even if it could never quite fill the role as brilliantly as Shea. Citi Field was destined to be Roger Moore to Shea’s Sean Connery. Yet it’s where I go as much as I can. I don’t dream about it the same way, I don’t reflexively answer that it’s where I want to be. If there’s a threat of rain before a game to which I hold a ticket, I still say something to the effect of “I’m going to check the weather at Shea,” not to be contrary, but just because that’s where I’ve always looked.

It can rain all it wants on Citi Field. I instinctively crave blue skies and a few harmless puffy cumulus clouds over Shea.

***

It took a second season for Citi Field to acknowledge Shea Stadium. It’s been two years since there was a Shea Stadium. I still grope around for it, any sign of it, same as I do the Polo Grounds. The Polo Grounds last hosted baseball in 1963. I never saw a game there, but they’re both in the same boat now. The boat’s a ghost ship. You can’t see it, so you have to feel it.

Sunday night on Mad Men, Don told his 12-year-old daughter he was taking her to Shea Stadium to see the Beatles. Sally Draper screamed. So did I. We had different reasons. An affable production called The Rocker plugged amiably along on HBO a few weeks ago. It doesn’t matter what the plot was, except Rainn Wilson — playing an over-the-hill heavy metal drummer — admonished his much younger and more reticent bandmates that the Beatles didn’t ask permission from their parents to play “a little pub called Shea Stadium”. It was the best part of The Rocker. I sat through one solid hour of a piece of dreck called Old Dogs recently because I’d been promised it included a scene filmed at Shea Stadium. Indeed, for maybe one minute, while John Travolta, Robin Williams and two intolerable child actors frolicked in a Flushing stadium that no longer exists, it was four-star movie.

Then there was a serendipitous DVD viewing Stephanie and I had of Small Time Crooks, Woody Allen’s 2000 screwball comedy caper, which was a little moldy in its sensibilities, but captured Shea Stadium at dusk brilliantly. Woody and Elaine May show up at a Mets game. The greens of Mezzanine; the blues of Loge; the misty-water-colored memories…it doesn’t matter that at the moment Woody’s crowd is cheering, Sammy Sosa has just hit a home run of Masato Yoshii. It’s Merengue Night 1999, and the Mets come back and win.

At Shea. I was there.

So yeah, they bring a documentary about Shea Stadium to Citi Field, and they show me scenes from a Shea Stadium concert at Citi Field, and they set the final heartbreaking moments of September 28, 2008 to “This Is The Time” — Damion Easley walks; Ryan Church swings; Cameron Maybin closes his mitt…the ghost ship rides again. It’s the only way Shea sets sail these days. If it takes reliving its unhappiest of endings, so be it.

***

I’m a fan of last long looks around. After the first Billy Joel show in 2008 (the one that turned out to be the penultimate play at Shea), I waited in the right field corner of Field Level for Stephanie to emerge from the rest room. I also waited for someone to tell me to get moving, but no one did. I marveled at how Shea was set up for this unusual event, how there were all these chairs in the outfield, how there was this enormous stage, how on earth they’d cart everything away and make it look presentable for games the next week. I marveled at how the formidable Shea scoreboard was obscured by the concert apparatus, never fathoming that cameras would capture that signature Shea landmark falling to the ground three months later and that it would represent the gut punch of the movie Billy Joel’s people were making even more than Church’s flyout would.

And I marveled again that no one told me to move it, buddy.

The longest last look around came 74 days after the concert, after the Mets lost to the Marlins, after Tom Seaver and Mike Piazza walked through the center field gate, after the final recorded music every played at Shea Stadium — “New York State of Mind” — wound down. I stayed in one place after a game as long as I ever did at Shea.

Part of me is still there. Part of me has moved on, but honestly, not that much. My inner GPS’s default setting is still set where it was set ages ago. It’s recalibrated itself to make Citi Field my de facto destination, and that’s fine. I have a nice time in spite of (or sometimes because of) the Mets when I’m there and then I go home.

The new destination isn’t home. But it will have to do.

***

They give tours of Citi Field. It’s a good idea executed with mixed results. I took one on Labor Day weekend. Some of it is impossible to screw up, like the part where you’re taken to the warning track behind home plate, then into the dugout and down the first base line; you linger in front of the 330 sign in the right field corner and then by the Mets bullpen before you’re led through the home clubhouse. That part works very nicely.

The way the Mets run certain things, is it ever really a new era? Too much of it, however, is devoted to showing you the suites and the clubs to which you, the average Mets fan, won’t otherwise be gaining admission. Our tour guide was an absolute disaster during the parts of the tour that didn’t involve the playing surface. A few examples of the letdown factor:

• She dismissed the pictures of great New York sports journalists in the press box as “some old guys you’ve never heard of”.

• She sneered at the notion that anybody would actually want to have a wedding at Citi Field, while informing you that you could.

• She pointed to the oversized baseball cards on the Empire level with a brusque “there are some baseball cards” as opposed to taking two minutes and walking us through a brief history of the Mets from 1962 through 2009 (the just-traded Jeff Francouer had been removed and no 2010 card had yet taken his place).

No effort was made to explain the origins of the club, why it plays in Queens, what happened in the parking lot to our left in 1969 and 1986 — she didn’t even bother pointing out the window at the five markers that signify home, first, second, third and the mound.

I have a friend who gave tours of Shea Stadium during the five minutes when tours were given of Shea Stadium, in 1994. He carried a baseball in his pocket. A baseball marked with shoe polish. He then explained its significance, how a ball hit Cleon Jones on the foot and how Gil Hodges proved it with a ball just like this one, and the Mets went on to win their first World Series. Both Gil and my friend used their wits to create and tell Mets history, respectively.

There was little wit served up and no history to be learned on this tour, other than a pool table in the players’ lounge once belonged to the Rolling Stones. The presentation was shoddy, it was shabby and it was largely inaccurate. She carried a script but had clearly memorized only a few random bullet points. Nothing was mentioned of why Citi Field is designed as it is, what ballpark’s architecture inspired it, no “wow!” factoids about how many bricks it took to build the place. Our guide kept telling us there was ample opportunity to sneak into the well-guarded precincts of the Delta 360 Whatever It’s Called Club and other high-end eateries when, in fact, they’d sooner shoot you than not redirect you to where you belong if you’re a peon of the Promenade.

And why do they always think all we want to do is sneak into places?

***

If you’ve dealt with Citi Field personnel on any kind of going basis, it shouldn’t surprise you to know our tour guide seemed distracted and impatient with having to guide a tour. While she wasn’t rude (and offered to take on-field pictures for anyone who wanted to pose), it was clear this young lady had better things to do on this Sunday than her job. That’s how it is most Sundays at Citi Field when there’s a game. Most other days, too.

The Mets rarely go the extra 330 feet. Cripes, somebody’s small child needed to use a bathroom. The guide discovered the bathroom where we were standing was locked. Next place we went, same thing. The Mets had not thought to make a single bathroom available even though they had tours going through all day and chances are somebody was going to need to use one. Our group was accompanied by a security guard (because people who pay ten bucks to take a tour of a ballpark must be guarded at all times). Neither the guide nor the guard thought to check in with HQ and ask can we get a key up here for a kid who needs to use a bathroom? That would be going not so much the extra mile but just a lousy ninety feet.

You’ve seen the Mets in action. You know they don’t go an extra ninety feet if they can help it.

***

We had started in the Rotunda — Jackie Robinson; great American; let’s go upstairs — and we ended in the Rotunda — there’s the museum, knock yourselves out — and that was that. The only employee in the museum was another guard, skulking in silence. You’d think maybe a team that gives tours and brings you to its neato museum at the end would have somebody on duty to answer questions, some kind of resident historian, somebody to enhance the experience.

Yeah, you’d think.

You’d also think this wasn’t possible: During one leg of the tour when we were broken into two mini-groups and had to ride in two separate elevators, the guide’s group (mine) arrived at the next point ahead of the guard’s group. The guide had to ad-lib for a minute or two and seemed flummoxed. She went to a staple of these sorts of events and asked if anybody had any questions. When nobody did at that moment, she continued, “Anybody have any favorite Met memories?”

One man spoke up. Last game at Shea, he said. What an experience, what an unforgettable day, they had to drag me out of that place. The guide warmed to his recollection and agreed yes, sometimes the old ballparks mean the most to us because that’s where we have our memories and…uh…

She didn’t know what else to say, so she asked the same man another question.

“Did the Mets win or lose that game?”

***

I was the last tour member to leave the museum. I wanted to soak it up, take a few pictures, watch the video (whose script I wrote) in relative peace. I had to be my own historian. I’m a tough crowd on the subject of Mets history, but I honestly wouldn’t have minded somebody else telling me something I didn’t know. As it was, I took it upon myself to answer various and sundry questions the guide and guards couldn’t — including is there an open bathroom around here? Yes, I said, upstairs in the subway station.

When I left, I was genuinely bummed out. What a lousy tour. What a lousy sense of the Met self. They put up this great museum — I’m still shocked at how absolutely on target it is — and they lined the plaza and park and parking lots with those great banners of Met legends. To me, they’re all legends. They don’t have to be superstars. They just had to be Mets.

LIke Marv Throneberry.

Marv’s banner ranks as one of my favorite discoveries of 2010. It was as if somebody with the Mets was paying attention or hadn’t forgotten. Marvelous Marv did not personify Excellence Again and Again or Six Sigma or anything that would mistaken for the Mets’ wanna-be corporate soul of the 21st century. Marv was a Manhattan Met, the ironic idol of the Polo Grounds, he who got cheered despite his epic ineptitude. He got booed, too, but nobody’s perfect, not even a 1962 Mets fan.

The Mets saw fit to put up a banner of Marv Throneberry, the slugger who hit 16 home runs and the first baseman who committed 17 errors. The Met who more famously than any of his expansion teammates could not Play This Game. He was the baserunner who would have had a triple had he chosen to touch bags other than third. He was the fielder for whom rundowns were drills that used live grenades. He was the feller who wasn’t given a piece of birthday cake because Ol’ Case wuz afraid he’d drop it.

Marv Throneberry flies from a lamp post outside Citi Field, and long may he wave.

***

On this eerily quiet afternoon that followed the dreadfully disappointing tour, I wanted to commune with the first Met folk hero. I wanted to get up close to the Marv Throneberry banner and take its picture. That, I decided, would cheer me up.

Except it turns out Marv’s banner isn’t in just any parking lot. It’s in the players’ parking lot and somebody’s stationed at its entrance to keep you out, even if you explain all you want to do is take a picture of the Throneberry flag. I suppose that sounds weird, but I’m outside the Mets ballpark; it should sound like a perfectly reasonable request.

It wasn’t taken that way.

The guard was cordial, but despite being old enough to have quite possibly guarded Marv Throneberry’s automobile (or even Richie Ashburn’s), he didn’t let me in. “We can’t have David Wright’s car getting scratched up,” he told me.

The Marv Throneberry banner: Don't get any closer, buddy. I couldn’t argue with that logic, even though the last thing I’d want to do is cause harm to an innocent Lincoln. I accepted that this man was just doing his job and walked a few steps away before exploding in that way I have of losing my cool after bottling up my dismay for a few minutes too many.

“THIS PLACE IS RUN LIKE SOME KIND OF FUCKING PRISON!” I said, realizing that was a little over-the-top, considering my problem wasn’t getting out, but getting in. I instantly apologized with my standard “I don’t mean to get mad at you…” but he didn’t seem upset with my outburst. In fact, he kind of nodded in agreement at my assessment of Citi Field’s penitentiary leitmotif. Nevertheless, I would have to take my picture of Marv Throneberry’s banner from a distance, over a chain link fence.

Oh Marv, I thought as I snapped my photo, what’s become of our Mets? In your day they were lovable losers. Now they’re only half of that. Why must they be like this? And I’m pretty sure I could hear him answering back from somewhere beyond that lamp post:

“I still don’t know why they didn’t let you stay in your seat a couple of minutes longer in 1996.”

by Jason Fry on 27 September 2010 1:32 am In the last two games against the Phillies, one player has gone 5 for 8 with two home runs, a diving catch, a statement made on the field and fiery talk off the field. This player has raised his average 46 points since September 3. He’s not a September call-up or a rookie, but a familiar face.

His name is Carlos Beltran. He’s nearing the end of its sixth season with the Mets, with questions about whether there will be a seventh. Looking back at his time in orange and blue, two things stand out:

1) He is a remarkably good baseball player.

2) He has been treated horribly by a ridiculous organization and too many of its fans.

Beltran’s 2009 was marred by injuries, as were the seasons of many of his teammates. But he came back late in the year, and I had hope that he might be whole in 2010. But then January brought unhappy news: Beltran had opted for knee surgery in Colorado, and wouldn’t resume baseball activities until April. The Mets were livid, fuming that he hadn’t had permission.

My reaction was pretty straightforward: I was disappointed, but then I remembered how the Mets had handled injuries to Jose Reyes and other players during the horror show of 2009. Remember all that? Remember how players were day-to-day, would sit on the bench without going on the DL, would re-emerge for a brief, ineffective game or two, then go on the DL for lengthy periods? Remember how medical diagnoses relating to the Mets seemed to have more to do with spin than reality? After all that, and the pussyfooting around Madoff, and Dave Howard’s word games about obstructed views, I wasn’t inclined to believe a word the Mets said.

Beltran didn’t come back from knee surgery until the All-Star break, joining the Mets in San Francisco for an 11-game West Coast swing. The Mets went 2-9, and if you listened to talk radio you’d have immediately concluded that the problem was Beltran. (Without Beltran, by the way, the Mets had ended the first half of the season with a 3-9 skid.)

Yes, it was pretty obvious that Beltran had returned too soon from a long layoff — his timing wasn’t there and he’d lost a step in the outfield, hampered by the surgery or his knee brace or both. But the analysis from the troglodyte wing of the city’s columnists and the mouth-breathers on the FAN had little to do with his surgically repaired knee and a lot to do with the supposed quality of his heart. It was the same barber-chair stuff it’s always been: Beltran plays without passion, he’s listless, he’s passive, not a leader but a cancer.

One of the great things about advanced stats is they allow you to test your impressions against reality, showing you where your gut is correct and where your eyes are deceiving you or your prejudices are getting in the way. This stuff will never be even fifth or sixth nature to me, let alone second, but one stat I love is WAR, or Wins Above Replacement. It’s an ideal tool for figuring out how rosters should be constructed, and for seeing who’s worth his salary and who isn’t. (Here’s a basic guide to WAR from our new pals at Yahoo Sports’ Big League Stew, and here’s Joe Posnanski on why he likes WAR.)

So here’s Carlos Beltran. Basically, a player with a WAR of 2.0 or above is worthy of being an everyday player, and one with a WAR above 5.0 is a star. But don’t worry about that too much — remember Wins Above Replacement, and think how many guys the Mets have run out in recent seasons who definitely qualified as “Replacement.”

What do we see? We probably remember that Beltran struggled in 2005, and WAR backs that up: He put up a 2.2 WAR, which is OK but by no means impossible to find, and certainly not what you want from the first year of a seven-year megadeal. But after that? Holy God. In 2006 his WAR was 7.5, and the only player who did better was named Pujols. In 2007 he put up a 5.1 WAR; in 2008 he was ninth in all of MLB with a 7.1 WAR. In 2009 his WAR was 3.1, injuries and all. That’s two monster seasons, a very good one, one that was probably better than you figured, and one that was underwhelming but OK. Here are the Mets’ all-time leading hitters as measured by WAR through June. Beltran’s fourth, right up there with Keith Hernandez. And if you convert the stat to WAR per 700 plate appearances, he stands alone. Fangraphs also tries to assign a dollar value to players based on their WAR, which you’ll find at the bottom of Beltran’s player page. I know advanced-stats folks consider those valuations kind of wonky (and all advanced stats are works in progress), but it’s still a useful guide for figuring out if a player is worth his salary. By Fangraph’s calculations, Beltran has been worth the money and then some.

So that’s Carlos Beltran according to statistics. Now let’s wade into the intangibles, which is where the conversation about Beltran often becomes full of yeah buts.

I’ve never particularly understood this. I’ve always thought that the complaints about Beltran lacking passion were based on fan interpretations of his body language, which seems slightly more reliable than phrenology in assessing a ballplayer. In the field Beltran has always been superb at positioning himself, reading balls off the bat and taking that first step necessary to be in position to corral drives into the gap or against the fence. If his first step were slower and he had to lunge or dive for balls instead of catching them on the run, would that be playing with passion? If he tarted up good catches with hotdoggy pratfalls, a la the loathsome Jim Edmonds, would that be intensity? Was his stumbling, game-saving snag against the Astros halfway up Tal’s Hill unsatisfying because he didn’t grit his teeth or come off the field whooping and hollering? Why isn’t his headfirst collision with Mike Cameron — which could have ended both careers if it had gone slightly differently — remembered as proof of his grit or toughness?

I suspect Beltran’s entire Mets career would be regarded differently if he’d swung and missed the final pitch of the 2006 playoffs instead of taking it for a called third strike, even though it would have changed absolutely nothing. But if this proves anything, it’s that a lot of fans are crazy. Being fooled by a 12-to-6 knee-buckler of a curve isn’t a sign of passivity, but a sign that a very good pitcher made a perfect pitch. Players get to two strikes, look fastball and get erased by perfectly thrown curveballs every goddamn day. Sometimes it happens while you’re in the can or around the corner getting Doritos, and sometimes it happens in the ninth inning of Game 7 of the League Championship Series. Should Beltran have swung too late to show he really cared? Should he have smashed himself in the face with the bat to express his grief? Does the case against Carlos Beltran really come down to the fact that he doesn’t grimace enough? And if it does, whom is that an indictment of: Beltran, or columnists and fans who judge a player’s value to a team by facial expressions?

The Walter Reed incident was particularly distasteful on many levels. Mets officials anonymously threw Beltran, Luis Castillo and Oliver Perez — three players they were unhappy with — to the wolves, setting them up for a public shaming. (Here’s Matthew Callan’s great post from back then.) Beltran, though, had a reason he hadn’t been there — he’d had a lunch meeting about a school his foundation was building in Puerto Rico. I never heard a New York scribe challenge that, even though it would have sold a ton of papers. A couple of days later, Beltran’s agent Scott Boras had this to say about Beltran’s treatment by the Mets: “The team has a duty to run the organization professionally. Giving the players [short] notice, knowing they have plans or obligations in their personal lives, and then to admonish the players without checking, it’s totally unprofessional on all fronts.” I don’t particularly like Boras, but take a moment to think back on how many times the Mets have come across as dysfunctional and/or disorganized in recent years and tell me he’s wrong.

None of this mattered to New York columnists, who criticized Beltran’s attitude and work habits despite the fact that he’d been pretty thoroughly absolved. Here’s a sample from Mike Lupica: “All athletes worry about their next contracts when they get close to the end of their current ones. It is why Beltran wanted to get back on the field, even in his current diminished capacity, hoping he would look better than he has before his walk year, worried about what happens to him when he comes to the end of his $100 million contract a year from now.”

Really? Beltran returned early from knee surgery because he was worried about his 2011 performance? Beyond the character assassination by generalization (“all athletes”), it’s not even a logical charge. If Lupica were correct about Beltran’s motives (he doesn’t offer a shred of evidence that he is), wouldn’t Beltran have been better served sitting out for all of 2010 to avoid putting up subpar numbers and potentially reinjuring himself? Couldn’t you just as plausibly claim that Beltran talked himself into thinking he was more ready than he was because he loves to play baseball and wanted to help his teammates? I don’t know that that’s true, but why is Lupica’s version more believable than that?

And if you care about such things, Beltran has evidenced plenty of passion in talking with reporters. He’s the guy who called the Mets the team to beat in 2008. Just two days ago, he was the one who was most upset with Chase Utley’s takeout slide of Ruben Tejada, and admitted trying to take out Utley and Wilson Valdez. Contrast that with, say, David Wright’s purse-lipped, vaguely corporate bromides after awful losses, and ask which player you’d expect to be crucified for a lack of passion.

Carlos Beltran is one of the greatest players to ever wear a Mets uniform. If there’s anything shameful about his years in New York, it’s not that he had a subpar first season by his high standards, or that he got fooled by a great curveball when we really wish he hadn’t, or that he had the misfortune to be betrayed by his knee, or that he employs an agent fans dislike, or that he plays baseball with grace and ease instead of flailing Francoeuresque fire. What’s shameful is that he’s been treated shabbily and sometimes viciously by an organization and a fanbase that doesn’t appreciate him.

by Greg Prince on 26 September 2010 7:28 pm Let’s not mistake this for a triumph. A triumph is clinching your division. The Phillies will know triumph very soon.

But they don’t know it yet.

You can only win what’s in front of you on a given day. The Mets won a ballgame they didn’t want to lose, one I’m pretty sure none of us wanted them to lose. We can create our own unflattering Met narratives, thus we didn’t need an obvious storyline hitting us over the head like so many flying corks in somebody else’s clubhouse. METS WATCH PHILLIES CLINCH was one to be avoided at all costs.

So now what? The Mets will return to desolate Citi Field Monday night, probably play with less passion and purpose against the Brewers and Nationals than they generated against the Phillies, and we’ll find reasons to feel less than impressed. Should they somehow sweep the next two homestands, finish above .500, finish ahead of the Marlins (they’re one game behind in the largely ignored race for third place), all that will do is irk us into asking where this was when it might have done us some real good. Either way, ten minutes later, the manager will be fired — unless a season-ending hot streak somehow saves his job, in which case we’ll scream bloody murder because we’ll know it’s all a mirage.

Yet Sunday at Citizens Bank Park wasn’t a figment of our imagination or speculation. It was a baseball game between two baseball teams: no Davids, no Goliaths, nobody vocally scrounging for pride or revenge. Just a baseball game conducted by professional baseball clubs. Both sides seemed a little tight, they both made some mistakes, but one recovered its poise and did enough good things to outlast the other. Most notably, Carlos Beltran truly returned to Carlos Beltran form (3-for-5, 2 home runs, mobility in the field) for the first time since early 2009. Was that a mirage? Or have the past 15 months been the outlier? Dude was a pretty great ballplayer for a decade before his knees kicked him in the groin, so to speak. We won’t find out for sure if his form is permanent in the final week of 2010, but gosh, for one afternoon in Philadelphia, he was a grand spectacle like that we once knew and generally cherished.

Other sweet sights: the enduring rebirth of Nick Evans; the surprising stinginess of our bullpen (Green, Acosta, Feliciano, Dessens and Takahashi gave up nothing, aided in no small part by Nick and Carlos’s infinite play list); and a line of Mets slapping hands when it was done. When we were the about-to-clinch club in 1986, I rolled my eyes a lot at Mike Schmidt’s declaration that nobody was going to drink champagne in his also-ran face. Those Mets traveled to the Vet needing to win one game to officially secure their division title. With three weeks remaining and a 22-game lead in their back pockets, there was never a more foregone conclusion than the outcome of the 1986 regular season. But the Mets went 0-3, and while it didn’t matter once the Mets were in the heart of October, I still remember being annoyed about it. I’m annoyed about it still. I’m annoyed, still, that the Mets were swept in Pittsburgh in 2006 with a crown waiting to be worn. That it meant I could go to Shea and witness the coronation first-hand never lessened the transient frustration of not getting it done when it could get done.

These Mets today saw to it that the eventual N.L. East champion Phillies couldn’t get it done. They’ll schlep their t-shirts and their bubbly to D.C., and their pleasant and gracious fans will have to make an extra trip on a school/work night. In the end, they’ll have what they came for. But not at our expense, not today.

It’s not a triumph. But it will have to do.

by Greg Prince on 26 September 2010 2:27 am “Making an entrance after the president. That’s just not how we play bridge. It’s not how we say cricket.”

–Toby Ziegler, The West Wing, regarding breaches of protocol

Instead of veering wide of second base, Carlos Beltran directed his legs straight toward those of Chase Utley and Wilson Valdez. Instead of leaving three runners on base, Lucas Duda drove them all home. Instead of melting down after a poor first inning, Dillon Gee toughened up for the next six.

Instead of losing in Philadelphia, the Mets won. That was a nice change of pace.

It’s not like the Mets hadn’t won before at Citizens Bank Park in 2010; it only feels that way. We’re 3-5 there, which isn’t great, but it ain’t 0-8. The Phillies are a very good team, but they’re not unbeatable. Nobody is. Glad the Mets finally figured that out.

After the 5-2 victory that snapped the Mets’ six-game losing streak and the Phillies’ eleven-game winning streak — and kept the Phils from clinching a tie for the division title — Josh Thole told Kevin Burkhardt it was like the Mets got their “pride” back. Josh is 23 (and appears 14), so he may be given to wide-eyed overstatement. But he’s one of the Mets, so I’ll take his word for it: The Mets got their pride back by beating Philadelphia at Philadelphia and by one of the Mets making a harder slide than he usually does.

Two questions regarding the return of this “pride”:

1) That’s all it took?

2) Where the hell was it before?

Beltran’s slide was good fundamental baseball. It broke up a potential double play. It scattered Utley and Valdez and it allowed the Mets to build what became their winning rally. If there hadn’t been uncommon amounts of chit-chat about Utley’s hard slide the night before, I would not have noticed anything unusual about Carlos’s “retaliation”. Beltran’s slide looked like a thousand slides I’ve seen the Mets make in my life, if not that many lately.

If that’s what fills the Mets with pride, so be it. I’d like to think the paychecks, the uniforms and the fact that a couple of million people follow their every move would make a fella proud to be a Met, but at 75-79, we’ll take what we can get.

From a young Gee’s perspective, this was a big win. He’s only made four starts in the major leagues, so they should all be big. Gee’s postgame comments were in line with this weekend’s narrative about how great it is for the Mets to play in the Citizens Bank “atmosphere”. I don’t mean to get hung up on what is said after games as opposed to what happens during them (though the Mets are generally more interesting talking than playing), but again, why should this all seem like such a step up in class for the Mets? You’re all in the same league, even if you don’t all have similar records. Let’s not invest opponents with any more mystique than they need. The Boston Garden’s been torn down a long time — until another one’s built, make yourself at home wherever you play. The bases are 90 feet apart no matter which park you visit.

Fortunately, Gee pitched as if he doesn’t distinguish among the Nationals, the Phillies or the 1985-86 Celtics (50-1 at home, regular season and playoffs combined). Ryan Howard took him on a very long ride in the first, but after that, no Phillies went anywhere on Dillon’s watch. Hard to say what it means for his long-term chances, but there is no long term at the moment, there’s just September. Dillon Gee is here because it’s September, and he just pitched a wonderful game. Lucas Duda is here because it’s September, and he delivered the Mets’ first big hit in literally ten days. Gee, Duda, Thole, the rest of the kids…they can be proud of being Mets without somebody signing permission slips.

They’re young, but they’re not that young.

by Greg Prince on 25 September 2010 1:00 pm The 2010 Mets are a temporary condition. Mets fandom, however, is a lifetime proposition. Some dispatches from around Metsopotamia, most of them showing us again that blue and orange waters run deep.

• Faith and Fear reader Tim Hanley wrote in to let us know he and his home movie of Ron Swoboda’s Game Four catch in the 1969 World Series will be included in the forthcoming Baseball: A New York Love Story, with his segment premiering on Channel 13, Wednesday, September 29, at 10:30 PM and Channel 21 Thursday, September 30, at 12:30 AM. This is part of a multichapter documentary WNET produced in conjunction with Baseball: The Tenth Inning, which itself debuts Tuesday. Ken Burns’s work picks up where his original masterpiece left off, in the early ’90s. If there are 30 seconds devoted to the Mets in these four new hours, I’ll be shocked.

• Faith and Fear reader Sharon Chapman is running diligently toward the New York City Marathon in early November. When not training, she’s been raising funds (with the help of viewers like you) for the Tug McGraw Foundation, collecting nearly $5,400 to date for a most worthy cause. Her most recent warmup race was the Rock ‘n’ Roll Philadelphia Half Marathon and her wristband of choice, naturally, bore the imprint of your favorite blog. To donate to Tug’s foundation and help fight brain tumors, please click here.

Hey guy! The FAFIF tee takes its place alongside the likes of Stan the Man in Cooperstown. • We can now say the Faith and Fear t-shirt has made it to the Hall of Fame. Inducted? Not quite, but ace illustrator Jim Haines was kind enough to don our garment of choice when visiting Cooperstown this summer and thorough enough to let everyone checking out the ballparks exhibit the URL you all need to know. Note that Jim has stopped off at the Polo Grounds; that was the first home of the Mets in case anybody in Mets ownership needs to be reminded.

The rarely photographed back of our shirt, pictured in front of images rarely invoked at Citi Field. • There are no actual Elimination shirts, but Randy Medina at the Apple knew there ought to be. And they were a hit! Hopefully the Fourth Place Clinching shirts are right around the corner.

• The Apple’s Elimination apparel line may be pure fiction, but you can actually still get a Gary Sheffield 500th Home Run cap on mets.com for some unfathomable reason along with $19.97 plus shipping and handling. $19.97 for a Gary Sheffield 500th Home Run cap? That’s about $17.97 more than it should be (if it should be at all), but take heart: it’s marked down from $24.99.

• Can’t let the subject of Metwear go by without tipping you off to Metstradamus’s investigative report from an Old Navy location in Queens. Let’s just say it’s a great place to get your hands on a Marlins tee.

• Belated congratulations to savvy Mets GM nominee Howard Megdal who swept all his primaries (including ours) and has since taken the next step of letting the Mets know about it. We look forward to a Megdal administration, both for the wins and the poems we’re sure it will produce.

• One of the greatest World Series games ever has just turned up intact on kinescope, thanks to Bing Crosby’s superstition and meticulousness. You’ve gotta read Richard Sandomir’s story in the Times of how we’ll finally get to see the Yankees lose Game Seven of the 1960 Fall Classic to Bill Mazeroski and the Pirates. How is this Mets-related? C’mon…

• Throughout this mostly desultory year, Matt Silverman has been rebuilding the season-by-season history of New York Mets, even the seasons that were akin to 2010 (spoiler alert: there were a lot of them). Visit Met Silverman and catch up, starting with the most recent installment, a salute to 1982 that far exceeds the 65-97 campaign itself.

• Finally, a reluctant farewell to 1979 Met pitcher Wayne Twitchell, who died too young (62, from cancer) earlier this month in his native Oregon. Aaron Fentress of the Oregonian captures his life before, during and after his time as a major leaguer, most of which he spent with the Phillies. I was on hand for his one and only Met home start, which wasn’t the greatest night for either him or me, but it’s all part of the tapestry. Our condolences go out to his loving family.

by Greg Prince on 25 September 2010 3:47 am The Mets have lost six in a row for the first time all season and have fallen five games below .500 for the first time all season. It is said you shouldn’t necessarily trust everything you see out of a team in September, yet I find it surprising we didn’t see this kind of downward spiral manifest in all its utter ugliness until now.

It’s also said you’re never as bad as you look when you’re losing. But the Mets have looked bad for a very long time; they just somehow once in a while avoided losing. That brand of luck appears to have been pulled from the shelf.

It will get worse before it can possibly get better. The Mets are likely to taste the nadir of their profession when the team they’ve considered their primary rival for the past four seasons clinches its fourth consecutive division title in their faces. It could happen Saturday night if the Braves lose their afternoon game in Washington. If not Saturday, then Sunday. The Phillies’ magic number is 2. After observing these two franchises for four seasons, to say nothing of nine innings Friday night, can you possibly doubt a clinching isn’t in the immediate offing?

The Phillies play to win, and they won. The Mets play until they don’t have to anymore. They have nine games remaining. If someone told them they could stay out on a field and plow through 81 consecutive innings to fulfill their contractual commitment, I honestly think they’d take a deep breath and bear down as much as they are capable of bearing down until they grounded into 243 outs if that’s what it would take to get their season over any quicker.

Among the many things one can find to irritate oneself from watching the Mets have the string played out around them these days, I took particular note of comments made by Jerry Manuel before Friday night’s inevitable loss. The subject was the impact a series like this — played in such a raucous atmosphere — might have on his young, impressionable players. Manuel went on about how it would be good for them to see what it’s like to compete inside the steaming cauldron that is Citizens Bank Park when a potential division-clinching is on the line.

It wasn’t so much Manuel agreeing with the premise, as posed by Kevin Burkhardt, that got me — it was that the Mets are suddenly going to learn about this now? Like this should be a novelty for them? They’re the New York Mets. They shouldn’t have to go to Philadelphia or anywhere to learn what it means to be hard-nosed or psyched up or whatever you want to call it. It wasn’t that long ago (though it feels like an eternity) when the Mets would occasionally blame a letdown in a place like Miami on their not being used to empty ballparks because they were so accustomed to more dynamic surroundings. The Mets would put a charge into Shea, Shea — we — would put a charge into the Mets and the collective energy level would reach as high as the Keyspan sign in left.

So now the Mets arrive from No Life Stadium, where they were swept in environs befitting their tepid pulse rate, and Philadelphia is supposed to provide some kind of lesson in how to get fired up. And they lose again anyway. The Mets don’t win when nobody (other than the Pirates) is on hand and nothing is at stake, and the Mets don’t win when they’re taking on a chronically motivated opponent in front of 45,000 red-clad brayers tased out of their minds on success.

Geez, whatever. Whatever the excuse of the night is, throw it on the pile.

Much was made afterwards Friday night about the hard, chippy slide Chase Utley took toward the body of Ruben Tejada in the fifth inning in the midst of a 5-4-3 double play. If this were an era in which the Mets also slide hard and chippily, it would have probably gone unnoticed, yet because the Mets lack familiarity with playing to win, it came off as unsporting or worse. Tejada, to his everlasting credit, not only turned the double play (despite a lousy throw from David Wright) but brushed the whole thing off as baseball being baseball.

If the Mets are pissed off about it, as their postgame quotes indicate, great. Go out and find the other team’s second baseman. And when you’ve done more than not saying “pardon me” by Mr. Utley on our way to high tea, keep it up elsewhere. You don’t have to start throwing elbows or knockdowns every other inning, but don’t treat getting riled up like it’s that suit you only put on for special occasions. Every game is supposed to be a special occasion. Every game is an occasion to get riled up. Every game is a game to play to win.

After Chase sent Ruben heels over head, the Mets “began yelling at Utley from the bench,” according to Andy Martino in the News. That I do find surprising, for it indicates the Mets actually watch the games they’re nominally playing.

If we’re sitting here in some future September examining yet another Mets win and we’re poring over quotes from battle-tested veterans like Tejada and Thole and Davis about how it all started for them that night in Philadelphia in 2010 — when they were rookies getting regularly pulverized and posterized until it dawned on them how the game was supposed to be played because they saw Chase Utley take nothing for granted…then I’ll believe the business about this being a good experience. For the time being, it’s just more of the same: The Phillies won and the Mets landed on their ass.

And if former second baseman and current Brooklyn Cyclones manager Wally Backman happened to be watching the postgame show, how far do you suppose he threw his TV when Wright said “cooler heads prevailed” and “we’ll re-evaluate the way we go into second base”? Enough with the cooler heads and the Committee to Re-Evaluate Slides, David Wright, chairman. Just shut up and take somebody out already.

As for R.A. Dickey, he could have pitched more effectively, but he had another MVP night when it came to offering analysis of why the Mets lost. Words and phrases R.A. used in a sentence as he stood by his locker answering questions:

• etiquette

• grotesque

• refined palate

• culture

• deem

• formidable

• Petri dish

• oblivion

• vortex

Granted, “that sure was a good no-hitter I just threw” would have sounded better than any of that, but barring unforeseen events like the Mets winning games the rest of the season, R.A. Dickey’s Every Fifth Day Impromptu SAT Prep Course is the best, last reason to stay tuned to this team.

As if we don’t do this sort of thing everyday, Jason and I collaborated on a “Dear John” letter kissing the 2010 Mets goodbye at Yahoo! Sports’ Big League Stew. You can feel our scorn and read us spurn here.

by Greg Prince on 24 September 2010 9:25 am Welcome to Flashback Friday: Take Me Out to 34 Ballparks, a celebration, critique and countdown of every major league ballpark one baseball fan has been fortunate enough to visit in a lifetime of going to ballgames.

BALLPARK: Coors Field

HOME TEAM: Colorado Rockies

VISITS: 1

VISITED: August 17. 1995

CHRONOLOGY: 14th of 34

RANKING: 10th of 34

I’m flying high over Denver, Colorado, with America’s hottest team and we’re all about to soar…

Now we’re talking! Coors Field — Top 10, baby! Excitement! Excitement not just that we’ve reached rarefied air in our countdown (figuratively and literally), but we are at the center of the action! It’s the summer of 1995, and no place in baseball is more happening than LoDo.

LoDo, if you haven’t had the pleasure, is Lower Downtown Denver, perfectly chosen spot for Coors Field, the National League’s first legitimately new ballpark since 1977, maybe since 1962. I say “legitimately” in deference to the inauguration of two expansion teams in 1993 and the introduction to the senior circuit of two retrofitted football stadia to our National pastime, absurdly large Mile High Stadium and simply absurd Joe Robbie Stadium (a name with the staying power of a minute steak).

Mile High played a huge role in the development of the Rockies their two seasons, allowing the club to introduce itself to the region with authority. The Rockies drew 4,483,350 fans in 1993, a record that will absolutely never be broken. If novelty and size didn’t come with expiration dates, the Rockies might have never wanted to leave the Broncos’ old paddock. But that arrangement was just temporary. Baseball was coming to Denver and it was going to have a ballpark to make it feel at home.

And boy did it. Coors Field felt perfect on contact. The National League needed Coors Field. We were down 0-3 in the ballpark department by the mid-’90s, getting our ass kicked in the architectural All-Star Game. The American League had Camden Yards, Jacobs Field, the Ballpark in Arlington.

The National League had like six variations of Veterans Stadium.

If you skip back over where the Rockies squatted (and the Marlins continue to squat until 2012), the last new place any N.L. team opened was frigging Olympic Stadium. Before that, the spate of Vets. Before that, Shea, and before that, Dodger Stadium, the only thing in the league besides Wrigley actually built for baseball.

Ohmigod how we needed Coors Field. Denver needed it, too. My first trip there was in 1990, pre-Rockies. You know what the locals were campaigning for? Baseball! They wanted it. I can still see the t-shirt I brought home for a friend: If We Build It, Major League Baseball Will Come. “It” was a beautifully illustrated classic ballpark. That t-shirt combined a clumsy slogan and a busy design, but I loved darling sentiment. As extra large as the Broncos were out there, they wanted more than football.

And they got it. The Rockies came to town in the first National League expansion since 1969, drawing those unbelievable crowds (1993 Home Opener: 80,227) in unbelievably gruesome weather, but the Coloradoans didn’t care. First a ballclub. Then a field to match their dreams. They couldn’t and wouldn’t stay away.

Most major league cities weren’t enamored of their home team when the 1995 season commenced given that it was opening late because of the longest strike in the sport’s history. The pox on both their houses sentiment ran strong. Me, I was easy — the second replacement baseball was replaced by the real thing, I conjured short-term memory loss regarding labor vs. management and salivated for the Mets’ return as if conditioned by Doc Pavlov himself. Rockies fans were even easier. They waited two years for Coors Field to open, then another three weeks while a truncated Spring Training scrambled to completion and then blew off the aftereffects of a snowstorm to fill more than 47,000 seats in LoDo. The Rockies did not let their loving patrons down, winning a dramatic Opening Night in 14 innings, 11-9

Which sucked from our perspective, since the Mets were the opposition that long, cold evening, but otherwise it was hard not to get caught up in what was going on in LoDo. The Rockies brought bricks to the National League for the first time in the age of concrete. They strove to evoke Ebbets Field (but weren’t nuts about it like some owners I could mention). And they put their new ballpark to great use, racing out to a 7-1 start and, for a while, putting a stranglehold on first place — all in their third year.

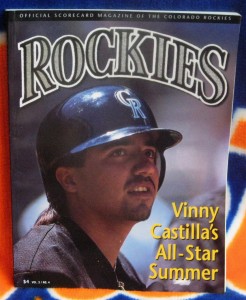

These were the days of the Blake Street Bombers, when everybody admired the ballpark and marveled at the thin air and asked no questions about whether anything else was fueling that fusillade of home runs. It was simply a great if slightly aberrational story: Dante Bichette (who beat us in the opener; bastard), Larry Walker, Vinny Castilla and Andres Galarraga were in the midst of combining for 139 home runs. Altogether, the Rockies hit .282 in 1995, best in the league. Altogether, the Rockies pitched to a 4.97 ERA, worst in the league. Yet unfathomable hitting was making up for wretched pitching. The Rockies were hot — the hottest thing baseball had to offer.

In the middle of August, I donned my oven mitts and reached in to grab a slice for myself.

Synergy was the buzzword of that trip. The name of the ballpark: Coors Field. The locally based company that bought the naming rights: Coors Brewing. Product marketed by company: beer. Industry I covered like a tarpaulin in 1995: beverages.

You could see it like you could see the mountains all around you in Colorado. This was meant to be, me and Coors Field in its rookie year. It was destiny and a smart PR guy who put us together. What, you think they’d want to schedule a press visit to their brewery when the Rockies were out of town? You think I would go for that?

The beauty part was the Coors-Rockies relationship went beyond slapping a name atop the LoDo landmark. Coors Field was so of the moment that it came with its own microbrewery, SandLot Brewery. It was truly one of the great ideas of all-time, doubling as a ballpark attraction for the team and a working laboratory for the company (it’s where the Blue Moon brand was created). My gosh, just thinking of the name SandLot puts me back there, and I mean back there, because I got the insider’s tour: where they made the beer, how they made the beer and, most importantly, what the beer tasted like as it made its way from tank to tap handle.

I believe the technical term for the taste was “perfect”. I’m not a beer guy, really. I wrote about it, but not with any great aficionadoness if that’s a word…and after a few samples at SandLot, you can bet it was. I don’t know if it was simple thirst or the charge I got from being on the inside sipping from what the brewmasters call “the pigtail” after getting to enjoy the outside of Coors Field and witnessing LoDo come to life for a Rockies game, but I was so into that beer. Neither at a baseball game nor in a business situation had I ever gotten tipsy before. But here, at both, I definitely was.

And I didn’t mind.

After the finest and freshest beer I’ve ever savored — Squeeze Play Wheat, they called it — my handlers and I headed to our seats. What kind of seats do you suppose the folks from Coors rated at Coors Field? Damn good seats: eight rows behind the Rockies’ dugout. Pete Coors himself was four rows in front of us. Bret Saberhagen was four rows in front of him, leaning over the dugout railing and shooting the breeze with his new teammates. More center of the action stuff: Saberhagen was the big prize of the trading deadline, the kind of proven ace a serious contender reaches out to scoop up from some downtrodden team dying to shed payroll…which was us in 1995. We gave them Bret Saberhagen (for Juan Acevedo and the immortal Arnold Gooch). Saberhagen never much impressed me as a Met but seeing him as a Rockie, just eight rows away…wow!

That was probably the beer talking. But sobered up and settled in after a fashion, my wowness never dissipated as the night wore on. Coors Field felt as fresh as what SandLot was brewing. It was crisp and open and electric, like no place I’d been for baseball. The house was packed and engaged by its baseball team. Intelligently engaged. Three years in the bigs and these were major league fans. Not only did they cheer their Rockies as three-quarters of their Bombers lay waste to Cubs pitching, but they were savvy enough to scoreboard-watch. The Dodgers had edged ahead of the Rockies in the N.L. West, but they were losing in Cincinnati. When that game went final, a roar went forth that was as majestic as the Rocky Mountains.

Good idea building It. They came.

I could have fallen in serious like with the Rockies if I’d imbibed a little more. Rick Reilly had suggested (albeit fancifully) after the Opener that even a Mets fan just visiting Coors Field would be tempted to never leave the joint. I could see that. I wanted a piece of it to take home. I spent an inning in the team store picking out apparel and posters and postcards so I could remember Coors Field when I was back on Long Island wistfully remembering what it was like to be in the center of the action, caught up in a team that was instantly good, as opposed to the Mets who were relentlessly bad. And my hosts, who had probably treated a few guests to nights like these, presented me with parting gifts: a Rockies cap; a Coors Field baseball; an Inaugural Season beer glass with a Coors logo. I’m sure ethics would have told me to have graciously declined the goody bag. I’m sure I would have told ethics to have another Squeeze Play.

When my professional obligations were fulfilled the next day, I retired to my cozy room at the cozy hotel down the road from the brewery in Golden and watched the next Rockies game, which wasn’t going nearly as well for the home team as the one the night before. A brutal storm rolled through the area, causing a long rain delay at Coors Field. When play resumed, the park had lost most of its customers. One of the Rockie announcers hoped empty seats would never be so prevalent on any kind of regular basis. That, he said, would be a sad sight to behold.

The announcer’s fear eventually came to fruition. The 1995 Rockies rode their fab four sluggers to the Wild Card (they lost the division series to Atlanta, Bret Saberhagen getting clobbered in the finale), but they faded from contention immediately after that first magical season. Chronically piss-poor pitching, impossible altitude, diminished novelty…the Rockies crumbled into ordinariness almost immediately and Denver reverted to full-time football town for the next dozen years. Coors Field remained well-built, but fewer and fewer came. Across the National League, ballparks like it rose and nipped away at the uniqueness of it. Almost everybody has something like it now.

But Coors Field did it first, did it with style and showed me unprecedented hospitality in the process. I toast it still.

by Greg Prince on 24 September 2010 3:17 am Just when you thought you’d never again see a 1998 Met in the big leagues — no one who knew the rare pleasure of dressing in the same clubhouse as Tony Phillips, Ralph Milliard, Todd Haney, Willie Blair and Jorge Fabregas — up stepped Jay Payton to emerge as this season’s Longest Ago Met Still Active (LAMSA).

It got close there for five months, and it didn’t look like anyone would materialize to fill the about-to-be eternal void, but then again Jay always was something of a slow starter.

Payton bided his time this season at Triple-A Colorado Springs, recovering from shoulder surgery that kept him out all of 2009. Sound familiar? That was the unfair and unfortunate story of Payton’s oft-delayed rise through the Mets’ minor league system. He was a sandwich pick in the 1994 draft but didn’t reach the bigs until the rosters were expanded on September 1, 1998, and didn’t stick for good until the beginning of the 2000 season. He didn’t do much till June and didn’t really kick it in gear until August. But there Jay Payton was throughout October, starting center fielder in every game of the postseason for the National League champs.

Metwise, Payton peaked in his official rookie year (ranking third in N.L. voting), suffering yet another injury in 2001 and being sent packing at the trade deadline in 2002 for rotation stabilizer John Thomson. The Mets were 4½ games from the Wild Card lead when Payton left. Bolstered by Thomson, they finished approximately a hundred games out. Cause-and-effect or coincidence? Hard to say.

Jay took well to Coors Field — hit .473 there in 2002, .321 in 2003 — but then made the mistake of leaving as a free agent. He wandered through San Diego, Boston, Oakland and Baltimore before his right shoulder took him off the major league map in 2009. Last year, while Payton was rehabbing (“I didn’t want an injury to be the reason why I quit the game”), there were no 1998 Mets in MLB captivity. It escaped our notice since we were properly Metsmerized that there was still a 1997 Met — Jason Isringhausen — active as well as two 1995 and 1996 Mets — Izzy and Paul Byrd.

Those pitchers are done, but Payton, 37, is lately back in Denver, gray beard and all (how is it I’m 47, yet 37, when applied to a ballplayer, sounds old?). We congratulate him on his perseverance and I thank him personally for the events of September 13, 2000, when I was working just north of Astor Place and not particularly loving it. There was a day game at Shea and I took one of my curiously timed long lunches so I could go off somewhere sunny and listen to the broadcast in peace. A late-afternoon meeting loomed, but I willfully ignored it as long as I could so I could sit on a bench and stay tuned through a compelling pitchers duel: Mike Hampton vs. Jeff D’Amico. Hampton was good (8 IP, 4 H, 2 BB, 7 SO, 1 ER), future Met D’Amico slightly better (8 IP, 4 H, 1 BB, 10 SO, 0 ER).

D’Amico gave way to Curt Leskanic to start the ninth. Jay Payton doubled to lead off and, two outs later, scored on a Robin Ventura double. No way I could go back to the office now. I gave myself the tenth to see what would happen before giving in to the realities of office life. After Armando Benitez escaped the top of the inning unscathed, the Mets faced ex-Amazin’ Juan Acevedo. With one out, Mike Bordick singled to center; Joe McEwing did the same. Bubba Trammell popped up for the second out.

Then Jay Payton and…BOOM!

Three-run homer! The Mets win 4-1 and solidify their Wild Card lead. I am exultant in Washington Square Park, where shouting and giving phantom high-fives won’t draw any undue attention. Then I reluctantly race back for my meeting, floating from walkoff-winning and dragging from the realization I can’t sit outside any longer on a perfect end-of-summer day and luxuriate in Mets Extra.

I’m still on the mailing list for the magazine I edited in those days and a couple of the changes I suggested at that meeting ten years ago are still in effect. When an issue shows up here, I leaf through it disinterestedly, but sometimes I notice a section title I named in 2000 and think back not to the dreary meeting that birthed them but the tense day game that preceded it. Maybe Jay Payton inspired my apparent abiding brilliance. Or maybe I just like thinking about better Met Septembers than this one.

Chase Field in Phoenix served this week as LAMSA Hall, where the four Longest Ago Mets Still Active congregated for an impromptu Bobby Valentine Era reunion. The Rockies were fighting for their playoff lives with Payton, Melvin Mora (Met debut: May 30, 1999) and recent addition Octavio Dotel (Met debut: June 26, 1999) in purple and black. In the Arizona bullpen, Dotel tradee Mike Hampton (Met debut: March 29, 2000) stood ready to turn around switch-hitters and thwart lefties as needed.

Wednesday night, Mora staked Colorado to an early 3-0 lead on a shot over the left field wall, but the Rox couldn’t make it stand up; they were trailing 5-4 when Hampton — who, like Payton, seemed so done in the face of multiple injuries that he was available to join a half-dozen retired 2000 teammates at a Mets Alumni event in May — came on in the eighth and struck out leadoff batter Dexter Fowler. He also sounded like Payton when he was called up from Reno early this month: “I’m not ready to give it up, not ready to quit — it’s never been an option.”

Funny thing about those prime-time (1997-2001) Bobby Valentine Mets: the best of them never did quit easily, did they? If you’d like a tenth-anniversary reminder of their cheerfully obstinate nature, you are advised to check out Matthew Callan’s delightfully evocative In the Year 2000 series on Amazin’ Avenue.

Meanwhile, a look at where Jay Payton fits in on the LAMSA timeline…

LONGEST AGO MET STILL ACTIVE: Chronology

• Felix Mantilla, debuted as a Met, 4/11/1962; last game in the major leagues, 10/2/1966

• Al Jackson, 4/14/1962; 9/26/1969

• Chris Cannizzaro, 4/14/1962*; 9/28/1974

• Ed Kranepool, 9/22/1962; 9/30/1979

• Tug McGraw, 4/18/1965; 9/25/1984

• Nolan Ryan, 9/11/1966; 9/22/1993

• Jesse Orosco, 4/5/1979; 9/27/2003

• John Franco, 4/11/1990; 7/1/2005

• Jeff Kent, 8/28/1992; 9/27/2008

• Jason Isringhausen**, 7/17/1995; 6/13/2009

• Paul Byrd**, 7/28/1995; 10/3/2009

• Jay Payton**, 9/1/1998; 9/23/2010 (current)

* Cannizzaro was Jackson’s catcher on April 14, 1962, at the Polo Grounds, so for LAMSA purposes, he debuted as a Met after his pitcher.

**For much of 2009 and 2010 — with Isringhausen injured, Byrd sitting out and Payton working his way back — Melvin Mora (5/30/1999) held what turned out to be interim LAMSA status. As we learned first-hand in August, the 38-year-old Mora, despite striking out to end a furious Rockies comeback Thursday night, is as ageless as his most magical Met moment is timeless.

Complementing the Longest Ago Met Still Active designation is Last Met Standing: the final player from each Met season to wear a major league uniform in game action. Who had the longevity to outlast all his former teammates from a given year?

Let’s find out…

LAST MET STANDING: 1962-1998

1962-1964: Ed Kranepool (final MLB game: 9/30/1979)

1965: Tug McGraw (9/25/1984)

1966: Nolan Ryan (9/22/1993)

1967: Tom Seaver (9/19/1986)

1968-1971: Nolan Ryan (9/22/1993)

1972-1975: Tom Seaver (9/19/1986)

1976-1977: Lee Mazzilli (10/7/1989; ALCS)

1978: Alex Treviño (9/30/1990)

1979: Jesse Orosco (9/27/2003)

1980: Hubie Brooks (7/2/1994)

1981-1987: Jesse Orosco (9/27/2003)

1988-1989: David Cone (5/28/2003)

1990-1991: John Franco (7/1/2005)

1992-1994: Jeff Kent (9/27/2008)

1995-1996: Paul Byrd (10/3/2009)

1997: Jason Isringhausen (6/13/2009)

1998: Jay Payton (9/23/2010; current)

Still to be determined is who will be the Last Met Standing from the seasons immediately following 1998. The candidates come from those onetime Mets who played in the major leagues in 2010:

1999: Mora, Dotel, Payton

2000: Hampton, Mora, Payton

2001: Payton, Bruce Chen

The 2002 Mets, as generally disgraceful as they were, still managed to spawn a surprising number of major league survivors who have demonstrated staying power clear to this season: Payton; Chen; the regrettable Gary Matthews, Jr.; Scott Strickland (after a five-year absence); Ty Wigginton, Tyler Walker (whose five-game stint eight years ago completely escapes my usually airtight memory); Marco Scutaro; and the last Bobby Valentine Met to remain a Met as we prepare to end the Jerry Manuel era, Pedro Feliciano. Since Feliciano, 34, is a lefty, we can assume that if he remains healthy, he will remain employed by somebody somewhere for quite a while longer. Thus, that 2002 75-86 banner should fly safely from Pedro’s trusty left hand for not a few years to come.

2003 brought Jose Reyes to the big leagues, while 2004 saw the debut of David Wright. If we’re groping around for the last 2003 and 2004 Mets any sooner than the end of this decade at the earliest, then there’s something very wrong with the world.

by Greg Prince on 23 September 2010 7:41 am [T]he ending always comes at last

Endings always come too fast

They come too fast

But they pass too slow…

— Jimmy Webb

The Mets began this baseball season by playing the Florida Marlins. They suffered their first loss while playing the Florida Marlins. They absorbed their first serious body blow when they were swept by the Florida Marlins. They kick-started their best stretch of baseball by sweeping the Florida Marlins. Then they started drifting aimlessly out to sea while playing the Florida Marlins in Florida Marlin home games far from Florida. Wednesday night, they finished playing the Florida Marlins.

And they never stopped losing to the Florida Marlins.

I think it’s fair to say if I never see Gaby Sanchez, Dan Uggla, Mike Stanton or any of the Florida Marlins again, it will be too soon, though the Mets’ first game of 2011 will be against the Florida Marlins, and, by then, I’ll be carping that I can’t wait to see the Mets play anybody — even the godforsaken Florida Marlins.

The final Met loss of the penultimate season at Soilmaster Stadium, on what was technically the last night there was summer, would have been a memorable train wreck had anybody any reason to keep an eye on the tracks. This was the kind of game — fall way behind immediately; scratch and claw enough to make you believe redemption is getting loose in the on-deck circle; find a way to fall cruelly and viciously short at the end — you fume about for ages if it means anything in the standings or if it’s the middle of May or if you’re 15 years old and haven’t yet fully learned what the Mets will do to you if you watch them too often and too closely. As was, in as meaningless a context as the Mets are capable of providing them, it was still pretty bad.

Seriously, this is what I think of every time they show Niese in profile. Jon Niese, pictured at left, got knocked silly in the first inning. Well, he knocked himself silly by walking three Marlins en route to digging the five-run hole from which my momma done tol’ me the Mets were never going to emerge. Overall, Niese has been a feelgood story for the 2010 Mets, but it feels now like he ought to take a seat as soon as possible. The kid from Defiance has defied the odds to a great extent this season, logging 165.1 innings to date, far more than we could have counted on coming off last year’s gruesome leg injury. It was to his credit that after the five-run first he bore down and was mostly effective until he left in the bottom of the sixth. But it would probably be to his detriment to ask much more out of him and his not-quite 24-year-old left arm.

Hopefully his final two starts — his because on the attrition-addled, Ollie-saddled Mets of September 2010, nobody else is available to take them — won’t represent some kind of workload tipping point per his long-term well-being. Maybe worrying about another dozen or so innings is unnecessary fretting, but he hasn’t been particularly effective in a month, and there’s more to Jon Niese’s Met future than the Brewers on Tuesday and the Nationals on the final Sunday.

There’s almost certainly nothing left to the Met future of Jerry Manuel beyond October 3 except one final press briefing in which he sheepishly grins, shakes his head and says something you’d laugh along with if you found anything about the team he leaves behind amusing. Of course he won’t be back next year. It’s an open secret, which nonetheless doesn’t make it polite to speak about in decibels above a whisper when Jerry’s in the room.

A few weeks ago Wally Backman seemed to be openly coveting Jerry’s job when he answered some questions for the Post. Last Sunday, Mike “Talk to the Back” Pelfrey couldn’t resist speculating what it might be like playing for Joe Torre if Joe Torre was managing the Mets. And Torre himself briefly let it be known he wouldn’t be averse to considering such an opportunity before “closing the door” on it when informed he appeared gauche being so openly amenable to taking another man’s job.

The last big game Jerry Manuel managed was, not surprisingly, against the Florida Marlins, two years ago next week. The Mets didn’t win that one either, though it’s tough to pin it on Jerry’s managing. Consensus had it Manuel came into a tough situation midway through 2008 and made the best of it, leading the club through a 40-19 revival at one point and guiding also-runners to almost-winners. When his status was shifted from interim to permanent, it was a popular choice.

Everything since then has gone horribly wrong under Manuel. He earned the shot in 2009 through what he had done to get to the end of 2008 in contending shape (I still have no idea how we led the Phillies as late as we did). He earned a chance at redemption in 2010 because 2009 didn’t seem a fair reflection of his skills in the wake of all his players’ injuries. 2010 is clearly the end of the line. He hasn’t motivated the Mets, he hasn’t strategized the Mets out of their continual malaise, he couldn’t slow the Mets’ post-Puerto Rico tumble from making its inevitable downhill descent.

On merit, Jerry Manuel doesn’t deserve to return. But he does deserve to go out as one of thirty major league managers — the kind who isn’t talked about or talked to as if he already isn’t there. I won’t feel bad when somebody else is managing the New York Mets (unless it’s Art Howe again), but I do feel bad that Manuel can’t get to the finish line without his dismissal being cavalierly treated as a foregone conclusion. When Willie Randolph’s managerial tenure was on the clock and Gary Carter publicly leapt at the chance to not just throw him under the bus but to back the bus up over his still employed body, it was a cringeworthy incident. There’s a code that says you don’t do that. It’s fine for the rest of us to grease the skids, as we’re just watching from a distance, but when you’re in a profession, it’s simply bad form to join a conga line intent on kicking a colleague to the curb.

“I don’t know” is a good all-purpose answer to give for the record when somebody asks about replacing a manager who’s already in office if you’re either a prospective replacement or one of the players who’s still being managed by that guy. And if you’re a person talking to that guy, take it easy on him. You can hear it in the voices of the Mets’ beat reporters when they question Manuel about almost anything, with the implication embedded in every inquiry about next year being you’re not going to be here but…