The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 5 December 2023 3:44 pm A dozen years ago, after some dabbling on ancestry.com, I connected with a same-last-name relative living on the West Coast. She wasn’t exactly distant or long lost, but I’d had only the vaguest notion of her existence, and I don’t think that she’d ever heard of me. Stephanie and I met her and a friend for dinner when she was in town to visit some other Princes with whom nobody on our side of the divide was currently in touch. It was quite a kick hearing somebody mention people I knew of, however slightly I knew of them, as if an authentic connection existed, even if it was basically by default. Everybody was very friendly to one another for an evening…and that was pretty much that for this briefest of Prince family reunions.

On Saturday afternoon, I took part in a different yet similar familial coming together. No offense to my cousin from 2011, but this one I felt more deeply, lack of bloodlines be damned.

Saturday at the Sheraton in Flushing was Queens Baseball Convention day, a highlight of the offseason calendar for the past decade. QBC is a Hot Stove miracle pulled off by a bunch of people, led by primary organizers Keith Blacknick and Dan Twohig, who bleed orange and blue and give their sweat and tears to the endeavor as well. Every offseason, I wander into a venue that they’ve transformed into a winter wonderland for Mets fans, which is to say it’s full of Mets talk and Mets stuff and Mets vibes and Mets personalities (Billy Wagner, Cliff Floyd and Terry Collins topped the bill this year) and, of course, more Mets fans. It’s easy enough to remember QBC is coming up while not wholly appreciating that this thing doesn’t happen without so many folks making it happen.

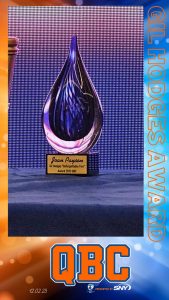

I show up every year to help present an award named for Gil Hodges. The award was conceived back when Gil was being unjustly ignored for the Hall of Fame. Then Gil was voted into Cooperstown. QBC still gives out the award, because Gil is still Gil and the sentiment behind showing appreciation for unforgettable members of the Mets family glows on.

This year’s version of the Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award was dedicated to the mom of our clan, Joan Whitney Payson. I’d prefer to refer to her from here on out as Mrs. Payson, because it doesn’t feel right or respectful to call her “Joan” or “Payson”. She was Mrs. Payson in life (1903-1975) and is Mrs. Payson for all time, and not in that unctuous way reporters refer only to sports franchise owners and nobody else in earshot as “Mr. So-and-So”. If we’re all going to be super formal and call one another by title, fine. If we’re not, it’s a bit much to “Mister” up the owner just because they’re the owner. Nelson and Fred; Fred and Jeff and Saul; Steve and Alex. They were or are people, just like you and me, even if people who can own sports franchises may have access to a different level of resources than you or I. This year’s version of the Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award was dedicated to the mom of our clan, Joan Whitney Payson. I’d prefer to refer to her from here on out as Mrs. Payson, because it doesn’t feel right or respectful to call her “Joan” or “Payson”. She was Mrs. Payson in life (1903-1975) and is Mrs. Payson for all time, and not in that unctuous way reporters refer only to sports franchise owners and nobody else in earshot as “Mr. So-and-So”. If we’re all going to be super formal and call one another by title, fine. If we’re not, it’s a bit much to “Mister” up the owner just because they’re the owner. Nelson and Fred; Fred and Jeff and Saul; Steve and Alex. They were or are people, just like you and me, even if people who can own sports franchises may have access to a different level of resources than you or I.

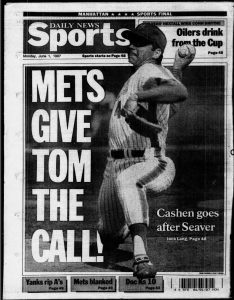

But Mrs. Payson was Mrs. Payson, and the chance to take a few minutes at QBC to illuminate her story in the middle of winter for a roomful of Mets fans who relish a little Mets history is one I don’t forget to appreciate. Through this platform over the years, I’ve had the opportunity to offer some insights on Gil Hodges, Ed Charles, Tom Seaver and several other leading lights of the Mets family. Given that Mrs. Payson hasn’t necessarily been top of Mets fan mind since her passing from the scene, I loved that Keith and Dan wanted to bring this woman’s legacy center stage.

I also loved that accepting the award on behalf of Mrs. Payson were some very warm people named Payson and de Roulet…and that I got to meet them and talk to them and realize that their family may not own the Mets any longer, but the Mets never truly left their family. These relations weren’t long lost and they weren’t distant. Spending quality time with Mrs. Payson’s daughter-in-law Joanne brought me back to that dinner with my cousin. She knew the stories people like me grew up on. She sprinkled names into conversation that until Saturday were only anecdotal to me. She made clear the Mets still meant something in their family’s lives, and that this little honor from QBC wasn’t incidental. In their own way, they’d been waiting for the Mets to care about Mrs. Payson. Never mind that it’s been 48 years since she died or nearly 44 years since the family got out of the baseball business. This was bigger than business to them.

You aren’t related to the woman who brought the Mets to life without that life remaining embedded in your life. These members of the Payson family tree clearly value that bond. The modern-day Mets seem to understand it. Not only did they co-name a high-rollers speakeasy for her down the right field line at Citi Field at the outset of 2023 — Joanne laughed when I brought up that branding, reminding me of Mrs. Payson’s patronage of Toots Shor’s place — but a representative of current Mets ownership, Josh Cohen, son of Steve and Alex, accompanied the Payson/de Roulet contingent to QBC. You could almost hear a circle being squared.

Daniel de Roulet, Mrs. Payson’s great-grandson, officially accepted the Gil Hodges award. Joan (he can call her that) would have been very happy to have received this token of everybody’s esteem, he said, but the real award for her and those standing in for her on this day was the presence all these years later of so many Mets fans, still caring so much about this team it was her pleasure to put into operation.

That he made sure to wear an orange sweater over a blue shirt for the occasion made his words resonate that much more.

The following are the remarks I delivered at QBC Saturday. Here’s to the woman who provided the baseball team that inspires us to this day.

***We’re gathered here today to remember two people at the heart of the beginnings of our favorite baseball team, the New York Mets.

When the Mets first took the field in St. Louis, on April 11, 1962, their first baseman was Gil Hodges. He hit the Mets’ first home run that night, one of 370 in his magnificent career. Seven-and-a-half years later to the day, Gil was managing the Mets in their first World Series game in Baltimore. Within a week, he would be known forever more as the manager of the 1969 world champions, just as we know him now and forever as Baseball Hall of Famer Gil Hodges.

We are today, as we’ve been for a decade, monumentally proud to present an award in his name, the Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award, to those members of the Met family who, like Gil, have warmed our hearts, brightened our spirits, and continued to light our way, and we remain incredibly appreciative that the Hodges family has blessed this endeavor. Gil Hodges Jr. joined us when the Queens Baseball Convention began in January of 2014, and Irene Hodges was thoughtful enough to spend some time with us here last December. They both represent their dad’s legacy so wonderfully.

There was little chance that if you were going to start a new National League baseball team in New York in 1962 that you wouldn’t find a spot for Gil Hodges. He’d been a Brooklyn Dodgers player since the 1940s, a Brooklyn Dodgers icon since the 1950s and a New York favorite for all time when some team from Los Angeles made him available in the 1961 expansion draft. Gil was on the verge of turning 38, but he still had some pop in his bat and no prospective Met could have loomed as more popular for a team that was still a blank slate. In fact, the first Met who was ever booed, during the introduction of the starting lineups at the Home Opener two days after Gil hit that first home run in St. Louis, was Jim Marshall. Marshall was a late injury replacement for Hodges, whose knee was acting up. Nothing personal against Jim, but the fans who trekked to Upper Manhattan on a chilly, damp day wanted to see the hero they remembered from Flatbush — and not just the old Dodgers fans in the crowd.

Said one former follower of the New York Giants on the eve of that first Mets game at the Polo Grounds regarding the presence of Gil Hodges, “It’s wonderful to be rooting for him after hating him for so many years.” Spoken like a true Giants fan. Spoken like a true baseball fan. Spoken like someone we can call the very first Mets fan.

Of course she was the first Mets fan. She more or less started the Mets.

And that’s the other person from the beginnings of our favorite baseball team whose memory we honor today, presenting the Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award to the family of Mrs. Joan Whitney Payson, the founding owner of the New York Mets.

As important as a few other figures in Mets lore are to the foundation of our franchise — Bill Shea, the attorney who started working the phones the minute the Dodgers and Giants left town because he knew New York wouldn’t be whole again until it was back in the National League; Branch Rickey, who placed his reputation behind the Continental League gambit that paved the way for National League expansion; George Weiss, the club’s shall we say president of baseball operations, stocking a roster under less than generous circumstances and playing for time with familiar faces until a farm system could take root; and Casey Stengel, the most familiar face of all, with a persona the public could embrace while forgiving the new team’s competitive shortfalls — you can’t say anybody was MORE important to getting this thing we love off the ground than Mrs. Payson. As important as a few other figures in Mets lore are to the foundation of our franchise — Bill Shea, the attorney who started working the phones the minute the Dodgers and Giants left town because he knew New York wouldn’t be whole again until it was back in the National League; Branch Rickey, who placed his reputation behind the Continental League gambit that paved the way for National League expansion; George Weiss, the club’s shall we say president of baseball operations, stocking a roster under less than generous circumstances and playing for time with familiar faces until a farm system could take root; and Casey Stengel, the most familiar face of all, with a persona the public could embrace while forgiving the new team’s competitive shortfalls — you can’t say anybody was MORE important to getting this thing we love off the ground than Mrs. Payson.

Quick question, please answer with a show of hands: how many people here would own the New York Mets if they could?

Quick followup: how many of you are in a position to make that happen?

Happily, Mrs. Payson had the ability to own a baseball team, and more critically, she had the desire to own one. She’d already owned a small piece of one, the ballclub she called her own from a heart-and-soul standpoint, the aforementioned New York Giants. That was no bloodless investment, either. “My mother used to take me to the Polo Grounds when I was a little girl,” she once reflected, “and I almost feel as if I’d grown up there.” Her childhood baseball home was vacated when the Giants moved to San Francisco — she was the only member of their ownership group to vote against it — so she did something productive about it.

This baseball-loving lady, in conjunction with the gentlemen mentioned above, started the New York Mets. After all, she told a reporter, “once you’re a National Leaguer, you’re always a National Leaguer.” This new bunch of National Leaguers whose existence as a unit Mrs. Payson made possible played at the Polo Grounds for two years while Shea Stadium was being built, and they caught on fast with old Giants fans, old Dodgers fans and the New Breed of Mets fans who found their spiritual home in whichever borough the Mets set up shop.

Sitting adjacent to the home team’s dugout, always keeping score and usually wearing a colorful hat you could make out from the Mezzanine, was the woman who didn’t need to own the team to adore it as she did. Not that ownership didn’t have its privileges. If she wasn’t at the game, she made sure the game came to her. The summer the Mets shocked the world and first contended for first place, in 1969, there was one TV station in Maine that aired Mets games under a special arrangement with a local seasonal resident. Guess who had a house in Maine.

Seven years earlier, when the Mets were new and only the flair and volume of their losing was shocking, Mrs. Payson traveled to Europe in-season. She left instructions to be wired the results of the games so she could keep up. The results in 1962 could be a little depressing, so she amended her guidance: please wire only when the Mets win. Let’s just say the transatlantic cables grew cold.

Mrs. Payson didn’t seek out attention as owner of a major league baseball club. It may not have fit her personality and it may not have fit the times. “I think I’m some kind of a vice president or something,” she demurred when asked about her role. Even at what would qualify as an owner’s most glorious moment, the acceptance of the Commissioner’s Trophy, in 1969, she stood before NBC’s cameras in the victorious post-World Series clubhouse only long enough to graciously accept congratulations. The extent of her remarks was to call out to her manager, Gil Hodges, to be careful and not trip on the temporary platform the network had built. Good to her word, she was still rooting for Gil.

At any moment, Mrs. Payson had every right to step into the spotlight, but left the daily operation of the franchise to others. Professional sports was an old boys’ network and perhaps she was content to mostly sit in her box seat, fill out her scorecard and cheer her team on. Still, she was no disinterested party. I’ve often wondered, had she lived beyond 1975, what Mrs. Payson would have done when free agency came along in 1976. We already know she spent a decade trying to pry loose from the Giants her favorite player from the Polo Grounds, Willie Mays, offering Horace Stoneham whatever it took in terms of cash to acquire his contract while Willie was in his prime. She finally got her man, albeit once he was at the tail end of his brilliant career. Willie Mays’s No. 24 hangs in the Citi Field rafters as testament not only to Willie’s unbreakable link to National League baseball in New York, but as a reminder of Mrs. Payson’s dedication, perseverance and fandom.

She was the woman who brought National League baseball back to New York, and she was the woman who brought the greatest National League baseball player back to New York. Pretty good accomplishments amid a crusty old boys’ network. If anyone harbored any doubts she could hold her own in a locker room atmosphere, I refer you to the team dinner she attended during the club’s first Spring Training. According to left fielder Frank Thomas, Mrs. Payson ordered herself a steak. When asked how she wanted it prepared, she said, “Just cut off its horns, wipe its ass and bring it out.”

Conversely, there was a distinctive touch Mrs. Payson brought to ownership that might have been absent from other hands. In her last year at the helm of the club, shortly before she passed away, there was a brief note in the Sporting News, informing readers that “sterling silver baby cups from Tiffany’s were sent by Mrs. Joan Payson to Bob Apodaca, Jon Matlack and Randy Tate, all of whom became daddies within the last year.” When you read that, you knew Mrs. Payson had nurtured an operation where “bring your kiddies/bring your wife” really meant something.

“Why do people fuss over me?” Mrs. Payson once asked. “I’m not important.” We’d respectfully disagree. Mrs. Payson was the first woman to own, on her own steam, a big-time professional sports franchise. That alone is pretty impressive. That it was the New York Mets, and considering what the New York Mets became in their first eight years — both an immediately beloved institution and the champions of the world — Mrs. Payson’s impact shouldn’t be understated. She gave us the Mets.

The least we can do as Mets fans at a Mets fanfest is say thank you and present her with the Gil Hodges Unforgettable Fire Award.

by Greg Prince on 30 November 2023 9:08 am Of all the key offseason hires approved by Steve Cohen, I haven’t seen the name Florian Cloud de Bounevialle O’Malley Armstrong appointed as Senior Vice President, Strategic Planning, or whatever title would imply a person has been brought in to help the Mets figure out what to do next. No wonder she’s not in Flushing, given the personal mission statement this individual issued twenty years ago and how it clashes with the way the Mets went about their baseball business this year.

The would-be Met executive in question is a British singer better known by her stage name Dido, the same Dido who had a decent-sized hit in 2003 called “White Flag,” an anthem dedicated to not giving up.

I will go down with this ship

And I won’t put my hands up and surrender

There will be no white flag above my door

Dido was singing about a romance, but her message can apply to any difficult situation. The song — which went to No. 1 in several countries and reached the Top Five on Billboard’s Adult Contemporary chart in America — isn’t thematically unusual in pop annals. “Don’t Give Up On Us” by David Soul topped the Hot 100 in 1977; “Hang On In There Baby” by Johnny Bristol went Top Ten in 1974 and happens to rank as my nineteenth-favorite song of “All-Time”. The 1985 Mets’ highlight video (film was passé in the MTV era) aired by SportsChannel during nearly every rain delay in 1986 was titled “No Surrender,” with Bruce Springsteen’s track off the Born in the U.S.A. album one of many apt tunes licensed for inclusion (if not into perpetuity, as the video’s soundtrack was hacked beyond aural recognition when revived by SNY as Mets Yearbook: 1985). Those Mets whose exploits Springsteen serenaded dueled the Cardinals down to the final weekend. No retreat, baby. No surrender.

Yet it is Dido’s ditty that comes to mind in the wake of 2023 because of the phrase inserted in the chorus. The white flag is an ancient, enduring and potent symbol of giving up, and giving up is such an odious notion within the human condition. There are more nuanced meanings available, however. In recent centuries, according to the History Channel website, “the white flag has become an internationally recognized symbol not only for surrender but also for the wish to initiate ceasefires and conduct battlefield negotiations. Medieval heralds carried white wands and standards to distinguish themselves from combatants, and Civil War soldiers waved white flags of truce before collecting their wounded.” When you look at the white flag less as a communiqué of capitulation and more in the realm of saying, à la Eric Cartman, “screw you guys, we’re going home,” then you can rationalize the value of a white flag once you’ve concluded you don’t have the wherewithal to even pretend to compete any longer.

For 2023, Faith and Fear in Flushing chooses as its Nikon Camera Player of the Year — an award presented to the entity or concept that best symbolizes, illustrates or transcends the year in Metsdom — The White Flag. By the middle of a campaign that was going nowhere, the Mets arrived at the realization that the most sensible way to play out their season was to find the first door leading to the future and give up on any pretense of contention.

In the words of Quick Draw McGraw Snagglepuss, exit stage 2024.

Between just before midnight on July 27 and just before 6 PM on Deadline Day, August 1, the New York Mets traded from their roster six veteran players. Five were exactly the kinds of players any team would want on their roster if that team was serious about making a run for a playoff spot, which is, in theory, the idea at the heart of any baseball season. Offed in the 112-hour selling period were a quality closer, two professional hitters and two starting pitchers universally described as future Hall of Famers. Each of those players the Mets no longer saw any need to keep around was placed in a good home, which is to say on a team with its eyes on October. Indeed, each of the teams acquiring one of these Mets played beyond the regular season. Between just before midnight on July 27 and just before 6 PM on Deadline Day, August 1, the New York Mets traded from their roster six veteran players. Five were exactly the kinds of players any team would want on their roster if that team was serious about making a run for a playoff spot, which is, in theory, the idea at the heart of any baseball season. Offed in the 112-hour selling period were a quality closer, two professional hitters and two starting pitchers universally described as future Hall of Famers. Each of those players the Mets no longer saw any need to keep around was placed in a good home, which is to say on a team with its eyes on October. Indeed, each of the teams acquiring one of these Mets played beyond the regular season.

The Miami Marlins traded for David Robertson, the quality closer. They made it to the Wild Card round.

The Milwaukee Brewers traded for Mark Canha, one of the professional hitters. They won their division.

The Arizona Diamondbacks traded for Tommy Pham, the other professional hitter. They won the National League pennant.

The Houston Astros traded for Justin Verlander, owner of three Cy Young Awards. They went to the League Championship Series.

The Texas Rangers traded for Max Scherzer, whose trophy case also houses a trio of Cy Youngs. They won the World Series.

Imagine having all these postseason pieces alongside a passel of other capable and accomplished players, including a few very much in their prime, all on one team. Then imagine looking at that team as a whole.

It looks better in the anticipatory imagination than it did on the field for the first four months of the 2023 season. The New York Mets already tried that cast. Scherzer and Verlander and Pham and Canha and Robertson and Alonso and Lindor and McNeil and Senga and Nimmo and Ottavino and Raley and an injection of youth from Alvarez and Baty and Vientos. A person planning to watch that collection of talent every day as of Opening Day couldn’t wait to see what they’d do together.

A person who actually watched that collection of talent every day from Opening Day until July 27 couldn’t stand to look at them any longer. A lot of people, actually — a lot of people who were Mets fans with high hopes at the outset of 2023 and a lot of people who had virtually no hope by the second half of the season.

Myself I’d count as no longer one of the truly hopeful by the night of June 8, once the Mets had been swept by the Braves in Atlanta. “Swept” doesn’t really do what the Braves did to the Mets justice. In each of three games at Truist Park, the Mets took a lead. In each of those three games, the Braves overcame the Mets’ lead. The series finale served as the most stark example of the chasm that had developed between these two franchises in the eight months since they each finished with 101 wins in 2022. The Mets hit three home runs; scored in five separate innings; and took or held a lead during every inning between the second and the ninth.

The Braves won in ten, 13-10.

A result of this nature in another season would have launched me into a rage or sent me spiraling into despair. This result in this season liberated me. As of June 8, when the Mets fell 8½ games behind the Braves, I was freed of the expectations that hadn’t matched the reality of the Mets for 63 games. This was no longer 2022. This was no longer Mets vs. Braves for the duration. The 2023 Mets had played with lethargy rather than urgency in April and May. June was starting no better. The Braves were still the Braves. Huzzah, I decided on June 8, I no longer have to take this team seriously as a National League East contender. After the way the Mets let the division title slip from their grasp in 2022, it was a perverse relief not to validate their presumed powerhouse status. Presumption evaporated on June 8. The Mets’ chance to catch the Braves evaporated with it.

But I didn’t think they would altogether disappear from the Wild Card race. And I don’t know if they ever did altogether disappear from the Wild Card race, even as June maintained its rancid pace — they’d ended June 1 at 30-27 and awoke July 1 at 36-46. That June swoon sure resembles a disappearing act. Yet the world in which fans of my vintage learned baseball, wherein your team was either fighting for first place or was languishing no place, had evolved into one dripping with consolation prizes. One Wild Card became two. Two Wild Cards became three. With three Wild Cards up for grabs, you have to be absolutely awful to be prohibitively out of it at the dawn of July. When the Mets completed compiling their nineteenth loss in their previous twenty-five contests, they sat ten games from the nearest Wild Card. Not a promising position from which to launch a highly improbable comeback, but not an absolutely impossible scenario, certainly not when you considered…

a) Roughly half a season remained.

b) The Wild Card scramble encompassed a slew of flawed entrants.

c) It was the fiftieth anniversary of 1973.

From July 1 through July 7, the Mets won six in a row. Verlander won a game and looked great doing it (7 IP, 0 ER). Scherzer won a game, regardless of how he looked (6 IP, 4 ER). Senga and Robertson teamed up on a four-hitter, striking out thirteen between them, winning and saving the Mets to victory once Alvarez (homer) and Canha (triple) provided some ninth-inning firepower. The 42-46 Mets were now 6½ games from the Wild Card. Fluidity was the fuel of conditional optimism. So many teams were fewer than double-digits from the final playoff berth. So many weeks were still on the schedule. So many Mets seemed to be coming alive. So, why couldn’t the Mets transform lethargy into energy?

I don’t know. But they didn’t. They lost their final two games before the All-Star break, their first two after the All-Star break, traded off some wins and losses for the better part of the next two weeks and entered the night of July 27 seven games under .500 and 7½ from a Wild Card. With a little over two months to go, they were running in place.

Steve Cohen saw the same team every Mets fan had in 2023, the one that looked imposing in March, the one that had marched into a miasma by late July, less the fog of war than a fog of bore. At the same stage in 1973, the Met record was worse (44-57 then vs. 47-54 now) and the distance from a playoff spot was three games farther away, and if you wished to hang your hat on You Gotta Believe, you were welcome to. But there’s a reason a season like 1973 lives on in legend: because it doesn’t happen every year.

Cohen discerned 1973 wasn’t going to happen in 2023, so he signed off on the trading of Robertson on the 27th; Scherzer on the 29th; Canha on the 31st; and Verlander and Pham and, for good measure, journeyman reliever Dominic Leone (to the then still aspirational Angels) on the First of August. Leone was the Mike Phillips-for-Joel Youngblood transaction of this Deadline Day. Robertson, Canha and Pham felt like standard-issue selloffs, veterans going somewhere else as a towel was being thrown in. A team that planned to contend over the final 61 games wouldn’t let go of its closer, even if he was a contingency closer, and wouldn’t have dispatched two bats that had been through the wars unless there was an obvious replacement in the wings (there wasn’t). But at the risk of diminishing the significance of the trades of Robertson, Canha and Pham, it was Scherzer on a Saturday night and Verlander on the succeeding Tuesday afternoon that made the deadline experience a full-blown Anti-Dido.

The White Flag was soaring above Citi Field, roughly where a 2023 pennant might have flown. Not only were Verlander, who had found his footing after an injury, and Scherzer, whose season hadn’t been quite so encouraging but he still carried that “knows how to win” cachet to the mound, were big names. They were tethered to big contracts. Not long, but hefty. How are you going to trade superstars of their caliber without picking up a ton of the ton they were owed?

You are going to be Steve Cohen is how. You are going to display a healthy impatience for how things are going, pick up the contractual tab in order to pry loose the best available prospects and determine that the preferable course of action is to lean into next season and the seasons after that, no matter how discouraging these half-dozen trades could have been interpreted in the context of this season. You interpret the trades instead as a necessary reset and bring back minor leaguers labeled legitimate prospects, executing what one self-styled wag referred to as the Steve Cohen Supplemental Draft. Suddenly, your farm system is restocked. Suddenly, a longshot playoff bid that has vanished is forgotten. Suddenly, you’ve heard of Luisangel Acuña and Drew Gilbert and Ryan Clifford and a bunch of other fresh faces nowhere near ready in the moment, but the hell with the moment. There are moments to come.

With their white flag, the Mets initiated a competitive ceasefire and conducted what amounted to battlefield negotiations with the general managers of organizations that were still out there fighting. They distinguished themselves from combatants by playing whoever they had handy and collected more than their share of wounds amid some grisly box scores. Mostly, they got through the season. They never effectively replaced Verlander and Scherzer (they are future Hall of Famers), but it’s not like we had really gotten attached to them as Mets. The starting pitching without them, led skillfully by Senga, performed with consistent competence down what in other seasons we would have labeled the stretch. Robertson wasn’t missed that much because there weren’t many save opportunities. DJ Stewart in right was enough of a revelation to erase cornermen Canha and Pham from our collective consciousness until perhaps we noticed them participating in the playoffs. Ronny Mauricio came up, flashed some of the ability we’d been told he’d been honing, and reminded us what fun it is to welcome genuine comers to the big leagues.

The Mets finished a little more below .500 (75-87) than they were when they began to make their trades, nine games from the third Wild Card slot, which is to say that for all their temporary tanking, they didn’t plunge significantly deeper into the abyss than they already had. Seven-and-a-half out when they commenced dealing. Nine out long after the dealing was done. They were a reflection of the squishy blob that represented the middle tier of their league. The postseason made room for a pair of 84-78 clubs in Miami and Arizona; Arizona made its way to the World Series. The 1973 Mets qualified at 82-79, albeit by capturing first place. Different times.

Still, one is permitted to squint in the rearview back to late July and make out a scenario in which those five players who helped five different contenders confirm their playoff reservations stayed with the Mets and were of similar use to our team, which wasn’t really in it, but not totally out of it, and played better than .500 ball — 22-21 — over their final 43 games despite the white flag having been definitively waved. Maybe 22-21 becomes 27-16 if we still have those guys we traded… and certain other teams don’t have some of those guys we traded…and because we didn’t wave the white flag, we don’t display post-deadline symptoms of shell shock (like that 0-6 road trip before we more or less straightened ourselves out)…and a few other things happen…and luck is finally on our side…and You Gotta Believe! But then you remember what everything looked like when we landed in late July and how you likely weren’t saying to yourself, “I just know we’re going to ride Verlander, Scherzer, Robertson, Canha and Pham in conjunction with everybody else here to a pennant.”

Whether the Mets of the fairly near future, elevated by the prospects received in exchange for raising the white flag in 2023, are in for a tangibly better ride is a component of the remains-to-be-scenery. It’s almost as if we can’t know what will happen until it actually happens. Or know what might have happened when it didn’t happen.

FAITH AND FEAR’S PREVIOUS NIKON CAMERA PLAYERS OF THE YEAR

1980: The Magic*

2005: The WFAN broadcast team of Gary Cohen and Howie Rose

2006: Shea Stadium

2007: Uncertainty

2008: The 162-Game Schedule

2009: Two Hands

2010: Realization

2011: Commitment

2012: No-Hitter Nomenclature

2013: Harvey Days

2014: The Dudafly Effect

2015: Precedent — Or The Lack Thereof

2016: The Home Run

2017: The Disabled List

2018: The Last Days of David Wright

2019: Our Kids

2020: Distance (Nikon Mini)

2021: Trajectories

2022: Something Short of Satisfaction

*Manufacturers Hanover Trust Player of the Year

National League Town is the Mets podcast that takes controversial stands like “David Wright oughta get a bunch of Hall of Fame votes!” Listen for elaboration here.

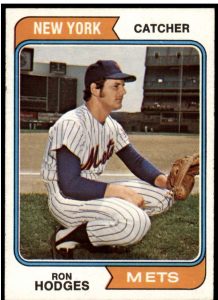

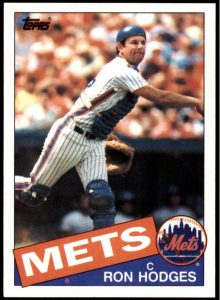

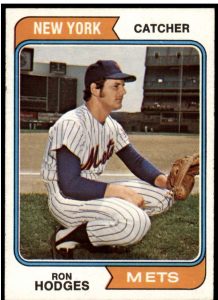

by Greg Prince on 25 November 2023 7:11 pm I have a few overriding memories of Ron Hodges’s Mets career that aren’t his signature moment in baseball.

1) Memorial Day 1976: The Mets have won the first game of a holiday doubleheader against Pittsburgh. They’re being shut out by Doc Medich in the second game. Ron Hodges hits a home run in the ninth. They still lose, but I remember the home run. Until I looked it up after learning of Ron’s passing at the age of 74 on Friday, I kind of remembered the home run being more dramatic. Maybe it won the game. Maybe it was his second of the game or at least the day. No, just a solo home run that brought the Mets within one. Hodges had been in Tidewater most of 1975, once the glitter of what he’d done as a rookie in 1973 had worn off and the Mets had become more interested in grooming John Stearns as the eventual successor to Jerry Grote. Clearly, Hodges was now back to stay. Maybe that’s what felt dramatic about it.

2) August 1980: The Mets aren’t doing well. They were for several months, but they’ve been beset by frontline injuries, including one that’s taken out their only All-Star, Stearns. Alex Treviño — good defense, light bat, zero power — is starting most games. Butch Benton, first-round draft pick in 1975, is backing up Treviño with a batting average so low (.048) that the caliber of his catching doesn’t immediately spring to mind in 2023. They miss Stearns. Maybe they miss somebody else in their catching corps. Briefly commiserating with a fellow Mets fan in 1980, I’m asked, “Why isn’t Ron Hodges playing?” He’s out with an injury, I said. Mystery solved for that guy, but it occurred to me that Hodges could be absent for more than a month — he hadn’t played since the Fourth of July — and somebody not paying rapt Met attention might not notice.

3) June 21, 1984: Rusty Staub delivers the difference-maker in a critical 10-7 home win over the Phillies on the first day of summer, as critical as a win can be on the first day of summer, considering the season wouldn’t be over until early fall. It felt as big as any June game I could remember. I was following along from a distance — a lot of calls to Sportsphone while grinding out my summer semester at USF — but I was all over this game. The Mets entered a half-game behind the Phillies for first place. The Cubs were circling the top of the standings as well, but knocking out the Phillies, who’d owned the division more years than not since 1976, was paramount to me. Staub’s pinch-hit single in the seventh to put the Mets ahead to stay signified something more than a pleasant June afternoon result unfolding. It was Rusty! The last time we were in first place this deep into a season was 1973! Who was one of our heroes then? Rusty! Of course Rusty was sent away after 1975 and wouldn’t return until 1981. If you wanted a sturdier throughline from You Gotta Believe to believing anew, you needed look no further than the contributions of Ron Hodges, a player who, save for a Triple-A stint in 1975 or Disabled List stay in 1980, had been at Shea since the last time Shea was inarguably the place to be. Versus Philadelphia this day in 1984, he reaches on a two-out error in the fifth, which allows two runs to score; drives in a run on a groundout in the seventh; walks with the bases loaded in the eighth for one more insurance tally. None of it is heroic, exactly. All of it helpful to a newly minted first-place ballclub, all of it a testament to what can happen if somebody hangs around long enough.

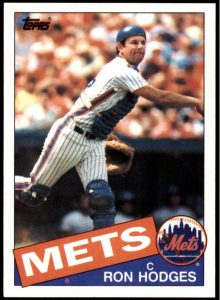

Ron Hodges hung around plenty. He showed up with little notice in ’73 and was a Met every single season thereafter through ’84, a dozen seasons in all. As a Met and only a Met, only Ed Kranepool and David Wright outlasted him. That he made himself technically irreplaceable for twelve years without ever excelling on the level of Wright or building a legend à la Kranepool makes his endurance all the more remarkable.

Scouting report? He was good at being Ron Hodges. Every franchise is better off when it has somebody who fits that description.

Ron settling in at Shea. A lefty-swinging minor leaguer who wasn’t necessarily filling any Mets fan’s radar in the hotly anticipated prospect sense, Hodges was called up from Double-A Memphis in June for the primary reason catchers are called up before September. Because some other catcher is hurt. That might be an oversimplification, but without running the research, I’d swear it’s mostly true. Butch Benton was called up because Stearns was hurt. Francisco Alvarez was called up because Omar Narváez was hurt. Ron Hodges was called up because Jerry May was hurt. Jerry May, a veteran, was here because Jerry Grote was hurt. For years, the catching pecking order had been Grote and Duffy Dyer, unless Grote was hurt. Then it was Dyer and hope for the best. Depth demanded something more in June of 1973 once the Jerrys were left hanging on the DL vine.

Thus, it was deemed time in Flushing, N.Y., for Ron Hodges from Rocky Mount, Va., who in the Daily News accounting of his promotion was identified as “no relation to late Met manager” Gil, a point hammered home in Ron’s yearbook writeups for years to come. His annual capsule bios also never failed to note Ron “had impressed Yogi Berra during 1972 inspection tour of Florida Instructional League,” where no-relation Hodges earned all-star honors. “He’s an outstanding receiver and the best catching prospect in the organization,” Billy Connors, the Mets’ minor league pitching coach informed the News. His batting average at Memphis was .173, so it was probably all about behind the plate for Ron.

Nonetheless, the freshman just shy of his 24th birthday when he came up, was a .300 hitter after his first fifteen starts, mixing in a homer and eight RBIs before National League pitchers tamed his bat. Nonetheless, Ron’s hot streak and dependable backstopping provided enough runway for Yogi — who knew something about catching — to carry Hodges along with Grote and Dyer once the incumbent came back and the Mets made their late-season move to advance from last place to first.

With a healed Grote ensconced, Hodges’s starts became rare (and Dyer’s nonexistent), but when opportunity knocked, boy did Ron answer. At Shea Stadium on the night of September 20, with the Pirates barely clinging to both first place and a one-run lead, Berra’s catching depth went into effect. Yogi used Ken Boswell to lead off the bottom of the ninth as a pinch-hitter for Grote, who had guided Jerry Koosman through eight innings of four-hit ball. Boswell responded with a single. Don Hahn sacrificed him to second. One out later, Duffy pinch-hit for reliever Harry Parker and doubled home Ken. Tie game. Hoping to build the winning run, Yogi sent Greg Harts in to pinch-run for Dyer. When that run did not materialize, it was Hodges’s turn to play. He caught the tenth, eleventh and twelfth, three perfect innings from Ray Sadecki.

In the top of the thirteenth, with one out, Richie Zisk singled. With two out, Dave Augustine…well, let’s get Bob Murphy on the mic to tell us what happened next.

“The two-one pitch…

“Hit in the air to left field, it’s deep…

“Back goes Jones, BY THE FENCE…

“It hits the TOP of the fence, comes back in play…

“Jones grabs it!

“The relay throw to the plate, they may get him…

“…HE’S OUT!

“He’s out at the plate!

“An INCREDIBLE play!”

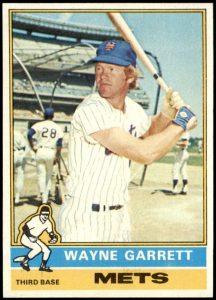

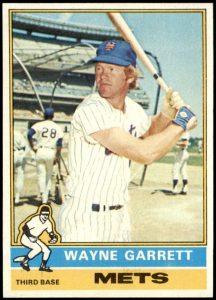

“Jones” is Cleon Jones, the left fielder, who is in the midst of a splendid career and a spectacular September. “The relay throw” is Wayne Garrett, Met third baseman more nights than not between 1969 and 1976, whether by choice or default; he’s playing shortstop at the moment after Buddy Harrelson was pinch-hit for in the whirlwind ninth. Garrett, too, is tearing it up this September. “To the plate” means Ron Hodges. Once Yogi has Grote, Grote is his September security blanket. Ron hasn’t started since the nightcap of the Labor Day twinbill that doubled as Craig Swan’s major league debut. He’s caught four-and-a-third mopup innings in the past two-and-a-half weeks before tonight.

Yet he finishes off an incredible play. Zisk is not fast as a baserunner, but he is a formidable physical force if he’s sliding into you, especially with the season on the line. Ron Hodges absorbed all 200 pounds of Zisk, tagged him, showed umpire John McSherry the ball, stood up, dusted himself off, came to bat in the bottom of the inning, and drove home John Milner from second with the winning run in a 4-3 victory. The Mets were a half-game from first place. The next night, they’d be in it, never to vacate it.

“There’s no comparison to anything I’ve ever done,” Hodges said after the game — and that was two nights after he’d delivered a game-tying pinch-single in the ninth in Pittsburgh. Rookie Ron Hodges was a pennant race veteran. He was the indispensable “2” on the 7-6-2 of a lifetime, and he drove in the only walkoff run of the Mets’ miraculous September. His signature moment in baseball is as indelible as just about any other Met’s.

That was Game No. 153 of the Mets’ 1973 season. Hodges wouldn’t play again. It was all Grote all the time all the way to the division-clincher on October 1 in Chicago. A World Series Game One ninth-inning pinch-walk for Harrelson, with Teddy Martinez immediately replacing him on the basepaths, represented his postseason participation, not only for ’73, but forever. We may have been told we had to believe more in ’74, yet Septembers were done sizzling at Shea for the rest of the Seventies. Save for a split-season mirage in 1981, the Mets would not legitimately contend into the final weeks of a campaign until the twilight of Ron Hodges’s career, and even then, in 1984, the Mets would have needed a couple of miracles on the order of 1973 to catch the Cubs, who passed them for first place for good in August.

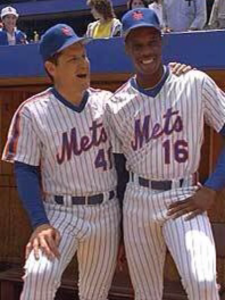

By then, the staff Hodges caught as a rookie, helmed by Seaver, Koosman and Matlack, had gone through multiple changes. In 1984, it was full of young, electrifying arms who were eliciting comparisons to the rotation Ron had come up on. Gooden. Darling. Fernandez. In between, there had been Swan maturing and lasting almost as long as Hodges, and Zachry, and Espinosa, and Falcone, and Bomback, and any number of starting pitchers and relievers. Hodges was around for all of them. Stearns succeeded Grote as the starting catcher in 1977; injuries curtailed his incumbency. Treviño showed enough promise that he got a decent number of reps before going to Cincinnati in the George Foster trade. Benton didn’t work out in the scheme of catching depth. Neither did journeyman Bruce Bochy, among others. In 1984, a former first-round pick named John Gibbons (your 2024 New York Mets bench coach) was the designated catcher of the future until injured. Another rookie, Mike Fitzgerald, took over, with Keith Hernandez frequently visiting the mound from first base to furnish any insight a neophyte catcher might not have handy for the fresh-faced pitchers.

Hodges persevered. Still there in 1984, same as in 1973, same as in all the seasons in between. Played in more than half his team’s games only once. Batted over .260 only once. Homered as many as five times only once. The statistics seemed beside the point after a while. We had a catcher who batted from the left side, a catcher who’d been through the last true pennant race the Mets had contested, certainly the last one they’d won. We had a catcher and Hodges had a role. “When I went back to Tidewater in 1975,” Ron reflected for his SABR biography in 2018, “I made a decision to be a backup in the majors rather than a starter in the minors.” Given his longevity, it appears Hodges knew what he was doing.

Ron getting up to leave. Ron Hodges’s final start in the majors came on September 25, 1984, after the Mets were eliminated from postseason contention. Most of his Septembers since his first one could have been described that way, but these were the 1984 Mets, and they were en route to better days. Hodges left his soon-to-be erstwhile employers something to remember him by, a single that tied another game with the Phillies, 4-4 in the bottom of the ninth. Ron came out for a pinch-runner, Jose Oquendo, and could watch from the bench as his then-and-now teammate Staub blasted the two-run homer that won the game for the Mets. It was a big deal in that Rusty became the first player since Ty Cobb to go deep before turning 20 and after turning 40. Rusty had one more year ahead of him as a Met. Ron would get one more at-bat, pinch-hitting in Montreal on the last day of the season. John Stearns was making what proved the last start of his career. GM Frank Cashen’s eyes that day were no doubt on the Expos’ catcher, Gary Carter. Carter would be a Met in a little over two months, acquired in December for four Mets who included Fitzgerald. By then, connections with their previous longtime catchers were severed. Stearns was a free agent who didn’t play after 1984. Hodges, too. “We wish Ron all the best,” Cashen said when the Mets confirmed they weren’t picking up the veteran’s option for 1985. “He has always been a gentleman and a credit to the ballclub.”

We mostly remember Ron Hodges for one play at the plate in top of an inning and the at-bat that followed in the bottom of that frame, and given the momentousness of the context that surrounded those events, that’s an appropriate reflex. But let’s remember the years after as well. It was easy to take for granted a backup catcher who, by job description, didn’t play very much. Yet the list of backup catchers who did it for as long as Ron did it for the Mets is limited to one.

***The following is something I wrote a few years ago for a song parody contest on the Crane Pool Forum. All you need to know, besides that it’s sung to the tune of Meat Loaf’s immortal “Paradise by the Dashboard Light,” is a) the contest demanded a reference to a 1970s television show be woven within the lyrics; b) the Phil Rizzuto portion should be interpreted as being announced by — who else? — Bob Murphy; and c) the story is being told from the perspective of a rookie catcher first called up in 1973.

With that, I share with you here my 2020 salute to Ron Hodges, “Paradise by the Scoreboard Light”.

——

Well I remember every little thing

As if it happened just a year ago

Summoned up to Shea when there was only one catcher on-site

And I never dreamed my shot

Would come along quite so quickly

And all the Blues in Memphis

They were wishing they were me that night

The Eastern Division grew close and tight

Nobody was that good

No team was going right

We were sitting in the basement with a ghost of a chance

Sitting in the basement with a ghost of a chance

C’mon, hold on tight

Oh c’mon, for dear life

Though it’s kinda hopeless stuck down in sixth place

I could see a smile light up on Tug McGraw’s face

Ain’t no doubt about it

We were hardly dead

We were less than seven out

With a month ahead

Ain’t no need to resign, man

Someone alert that ol’ Sign Man

Ain’t no doubt about it

You gotta believe

It ain’t over ’til it’s over

When ya got Matlack, Koosman & Seav’

Pirates, don’t ya hear our steps?

We’re now recovered from our injuries

I’m mostly sitting on the bench

But watching’s fun, just the same

Bucs, we’re gonna let ya know

Oh, you’re gonna come to regret us

I opened up my eyes

I got a big surprise

Yogi made some moves

And suddenly I’m in the game

Grote and Dyer, they were done for the night

“Ronnie,” Yogi said, “you’re gonna do all right”

And we headed into extras with a ghost of a chance

Headed into extras with a ghost of a chance

C’mon, hold on tight

Oh c’mon, for dear life

Though I was sorta nervous on that Thursday night

I could see paradise by the scoreboard light

Though being third-string could certainly bite

(Could certainly bite)

Paradise by the scoreboard light

Could only do what I could

And let my pitch-framing skills do the rest

Ain’t no doubt about it

We were doubly blessed

’Cause we were barely one game out and we were barely…

It’s beginning to feel like Sixty-Nine

And Sixty-Nine was mighty fine

It’s beginning to feel like Sixty-Nine

And Sixty-Nine was mighty fine

It’s beginning to feel like Sixty-Nine

And Sixty-Nine was mighty fine

It’s beginning to feel like Sixty-Nine

And Sixty-Nine was mighty fine

***

Dave Augustine, the Pirates’ promising outfield prospect, in the box

Zisk takes a slight lead off first as Sadecki looks in for the sign

Young Ron Hodges behind the plate late in his rookie season

In June he was at Double-A, now he’s in the heat of a pennant race

Augustine fouls one off, over into the box seats behind first base

The ball is caught by a fan who looks very familiar to me

Why, yes, that’s Archie Bunker from Astoria, right here in Queens

I had the pleasure of meeting Mr. Bunker before tonight’s game

Archie and his son-in-law Mike are guests of our sponsor Rheingold

Natural Rheingold worked with local taverns to provide two tickets

To patrons of one of the local taverns that supports Mets baseball

And Archie’s name was drawn from an entry sent in by Kelsey’s Bar

You know, I’ve got to tell you, that Mr. Bunker is a real character

He had some very provocative things to say to me when we met

He’s also quite a bowler and asked if he could be on my new show

“Bowling for Dollars,” airing weeknights on WOR-TV, Channel 9

I told Mr. Bunker I’m not the one who makes those decisions

But I will say he seems ready-made for television

Augustine, who had called time, steps back into the box

He had gone over to the on-deck circle for some pine tar

Now everybody in the crowd, including Archie Bunker

Perches forward in his chair for the next pitch

This has been a tense affair from the word ‘go’ tonight

We’re in the top of the thirteenth inning, tied at three with two out

Again, Zisk at first, Augustine at bat with a count of two-and-one

The veteran lefty Ray Sadecki on the mound

The youngster Ron Hodges puts down his fingers for the sign

Fasten your seat belts…

***

Stop right there!

We’re gonna know right now

Dave Augustine clocks it

Off Sadecki

He hits it a ton

It’s surely going

Will we ever recover?

Will a two-run homer keep us from first place?

Dave Augustine’s fly ball seems destined for space

Is it going?

Is there a way it’s not going?

Can we get it

Before it goes?

Will Augustine’s fly ball somehow not clear the fence?

Might there still be an outcome that eludes common sense?

We’re gonna know right now

If we can go any further

And still win this

And then maybe the pennant

Well, keep an eye on it

Maybe, maybe keep an eye on it

Keep an eye on it

We could pick up ground by Friday morning

Well, keep an eye on it

Maybe, maybe Cleon’s tryin’ it

Jones is at the track

The track they put out there for his warning

Well, keep an eye on it

Maybe, maybe it’s dyin’, it’s —

The ball is not out!

It could be a new day that is dawning

We’re gonna know right now

That it’s in play

Off the top of the wall

Yes it’s in play

No it didn’t leave Shea

It took a crazy high bounce into Cleon Jones’ glove

Seems our chances at first place have been given a shove

We’re gonna know right now

If we can go any further

We might love this

We might love this forever

What’s it gonna be, Zisk?

Come on, you can hardly run

What’s it gonna be, Zisk?

Score or not?

What’s it gonna BE, Zisk?

Safe… or… OUT?

Keep an eye on Zisk

Richie isn’t fast enough for this

Well, keep an eye on Zisk

Maybe we’ll nab him with a relay

We’re gonna know right now

Will we love this?

Will we love this forever?

Where’s the relay?

Will Cleon reach Garrett?

If Garrett grabs the relay

Will he get it to me?

Can I block the plate fully

And withstand Richie Zisk?

We’re gonna know right now

If we go any further

If we’ll love this

If we’ll love this forever

Keep an eye on Zisk

Will we love this forever?

Keep an eye on Zisk

Will we love this forever?

I caught the ball from Wayne Garrett

For a play at the plate

Then I tagged Richie Zisk, whose speed did not rate

I heard the ump John McSherry call him “OUT!” and not safe

And we would love this to the end of time

I swore, we’d love this to the end of time

Then I delivered the game-winning hit

John Milner scored on my drive

We ended the night just a half a game out

In the playoffs we were soon to arrive

I’d play eleven more years

And they weren’t the worst

But nothing could match

The thrill of coming in first

Backup ’til the end of time

It’s just what I would do (woo-wooo!)

Yet you’ll see in the rotunda

My number

The number I wore

Was Forty-Two

It was long ago and it was far away

And that ball, somehow, well, it never left Shea

It was long ago and it was far away

Augustine, you can see, is a footnote today

It was long ago and it was far away

No, I’m not related to Gilbert Ray

by Greg Prince on 24 November 2023 2:42 pm My friend Matt Silverstone. It feels good to write that. It doesn’t feel good knowing I’m writing it because I recently did a little curiosity-driven Internet snooping and discovered Matt died eight years ago. I seem to run into that situation when I start to wonder whatever happened to some old friend of mine with whom I long ago lost touch. Matt and I last got together in 1991, for lunch. Never heard from him again. I’m in time-shifted mourning.

We met when we were twelve. The junior high side of twelve. It’s an important distinction. Elementary school was well over. We were a matter of weeks past the age of absolute innocence if we use the movie Stand by Me as our guide. “I never had any friends later on like the ones I had when I was twelve,” Richard Dreyfuss as the Stephen King stand-in says at the end. “Jesus, does anyone?” The narrator had been recalling the summer when he and his three best friends went out in search of a dead body. That doesn’t sound like something I would have been into doing the summer I was twelve. By the summer I was fifteen, I imagine Matt could have talked me into it.

Matt was the first friend I made in seventh grade. I don’t remember what brought us together. Probably proximity in the same homeroom. Homerooms were determined alphabetically. My last name was the first to be called for the back of the alphabet in seventh grade. If there was one more kid named “Sullivan” or “Weinstein,” I may have wound up in another homeroom and maybe Matt and I wouldn’t have come into contact in quite the same manner. Or maybe we got chummy in math class and it was destiny. As for what drew us into hanging out, he said something amusing and I laughed is my guess. Or the other way around. Matt was a good listener. He was also innately funnier than I was. Wry and dry. I’ve been trying to remember some of the hilarious things he said all the years I knew him so I can quote him and illustrate that he was one of the funniest people I ever knew, but I think it was mostly delivery.

In ninth grade, there were two guys in one of our classes who, for lack of a more precise term, we’ll label preppies. This was before “preppies” were a thing, but go with it. One of them called out to the other about nothing of note, maybe a little too excitedly. Matt watched them interact and pegged them to me as “the gold dust twins,” no further elaboration. None needed. I laughed for about three weeks.

Anyway, in the fall of seventh grade we got to talking, and it became habitual. I went over to his house on a Saturday, which seemed an exotic thing to do, given that he lived on the other side of town. On that first trip I met his parents and his baseball cards. He wasn’t all that interested in either entity, but I knew who his father was before I ever knew Matt. His father was Lou Silverstone. If you read Mad magazine in the 1970s, you recognized the byline. Yes, Matt would confirm to those who would ask, that was his dad. It didn’t seem to impress him much. Lou didn’t seem terribly impressed by himself, either. He was low-key friendly, a good match for Matt’s Canadian-born mother. I aged out of the Mad habit as junior high went on, but I’m still grateful that when we were in high school Lou slipped me a complimentary copy of the issue with his parody of The White Shadow in it. He seemed particularly proud of that one.

Matt didn’t slip me any complimentary baseball cards from his collection, but I seem to recall we worked out a reasonable price for a stack of his otherwise neglected 1970 Topps, particularly some Seattle Pilots I was suddenly yearning for in November of 1975. I learned early on that while Matt was pro-Mets in that way kids on Long Island grew up being then, he wasn’t much of a sports fan. He wore a New York Giants hoodie to school, which caught my eye since I didn’t know too many other Giants fans. He shrugged that his grandmother gave it to him.

Some of the cards Matt didn’t sell me and other flammables became subject to Matt’s experiments with matches and rubber cement up in his treehouse. I’d never before been in a treehouse and, other than Matt’s, I haven’t been in one since. I didn’t know treehouses actually existed outside comic strips. It served as Matt’s pied-à-terre, where he could take a friend from the other side of town and burn things in peace. There was a bit of a rebellious or nihilistic streak to Matt. He didn’t have much use for the conventions of polite society. Maybe he grew tired of answering the same questions about who his father was or what it was like to be as tall as he was. Burning cardboard in the treehouse was one of his ways of going off the grid. Rubber cement, I learned from him, made for effective lighter fluid.

I waited this long to mention Matt’s height. He was a head or more taller than most everybody in junior high, 6-foot-6 by high school. He appeared mature enough so that on the first day of tenth grade, a vice principal told him in all earnestness he shouldn’t be sticking around this building anymore now that he’d graduated. I had decent height, enough to be placed in the back row of class pictures. Matt was the kid who was always directed to the center of that row. It must have gotten tiring to be reminded, when nobody had anything else to say, that he was unusually tall. Kids are good at pointing out physical differences. I’m pretty sure I never commented to him that he was tall. Maybe that’s why we stayed friends.

Matt did go out for basketball. Mostly the bench in JV, then on the varsity our senior year. He was just enough of a jock to make it work for him; he liked to surprise-punch me in the arm, as if that was something friends did. I never got mad at him for it, but that shit hurt. His game was being tall. Once in a while I’d get caught up in some schoolyard two-on-two with him versus any comers who wandered by. I wasn’t much good, but was usually willing to throw myself into it for a few minutes. Matt was a splendid teammate. Introduced me to the phrase, “Let’s kick some ass.” I’d heard others threaten to kick “your” ass (or my ass), but never with “ass” used as a non-specific object of kicking. I thought he made up the term.

I attended Matt’s JV games, which were usually sad affairs in that they were played after the varsity ones, which meant the gym cleared out and it was me and Matt’s parents representing maybe a quarter of the crowd. Matt, in turn, came to my school plays and made himself available to deliver copies of the school paper to various classrooms at my request when I was editor. From 1979 to 1982, he joined me at one Mets game annually, always into the experience if not deeply invested in the outcome. We supported each other’s endeavors and formed what amounted to our own social or antisocial circle. Matt didn’t not get along with anybody, but he was allergic to adolescent niceties. If “everybody” was doing it or watching it or talking about it, Matt wasn’t terribly interested in it.

As ninth grade drew to a close, what Matt wanted to do most was cut class. Like treehouses, that was one of those things I’d heard of but didn’t know was something that really existed outside of teachers warning against it. Matt talked me into joining him, probably to our shared detriment. I was very much on the bubble when it came to passing biology with the Regents on the horizon, and the biggest cutting-class call of all was not going to a review session that I, maybe both of us, could have used; my mother certainly believed I should have been there. Then again, it wasn’t mandatory, and we had our bikes, and we were riding on the boardwalk early on a June afternoon when those other suckers were stuck in school trying to remember which ventricle did what. Let’s just say I scraped by in bio and just now had to Google “ventricle,” whereas I’ll never forget that day on the boardwalk.

Having led me astray at the end of ninth grade, Matt set my agenda for the summer that followed. A lot of bike riding. He was really into bikes, especially fixing up old ones, including one for me. A lot of going to the beach, which was never something that appealed to me a ton once my family installed central air conditioning, but this was our dead-body summer, when Matt was expert at talking me into whatever. Without having to sell it, Matt convinced me everything we did was exactly what we should have been doing, even if it was stuff it wouldn’t have otherwise occurred to me to do, even if it was stuff I knew Matt shouldn’t have been doing. For example, Matt purchased from a classmate for twenty dollars and carried around a switchblade. I write that now and I wouldn’t blame you for expecting Blackboard Jungle to break out, but no rumbles were on the horizon. It was just Matt’s process for defying whatever might be expected of an exceptionally tall if otherwise average suburban ninth-grader going on tenth. He mostly liked to talk about the knife, as if he was keeping it handy for show ‘n’ tell (he gave it a name — Boopsie, I think, derived from Betty Boop). The only cutting he was gonna do was of class. The whiff of danger was enough.

I believe my role in Matt’s life as junior high was becoming high school was to be the kid who wasn’t remotely dangerous. Matt’s parents seemed to appreciate he had one friend who didn’t seem like the type to sell him a switchblade.

Midway through college, Matt transferred to a school on the East Coast of Florida. I was on the West Coast. He had his parents’ old Chevy Malibu and treated it like his bike, not hesitating to go out for a long ride, in this case to my side of the state. He’d call me on a Saturday afternoon and tell me to get ready for his arrival. I didn’t tell him no, and a few hours later he’d appear. This was during Matt’s would-be Lothario phase. Like with the switchblade, it made for better talk than action, which was just as well based on his patter. We’d run into a couple of girls I knew on the dorm elevator and he’d turn on the charm. The girls would laugh and exit. I’d cringe. He’d be undeterred.

I’ve been blackout drunk once in my life. It was one of those weekends Matt showed up. His advance instructions were for me to furnish gin. He’d bring tonic to make gin and tonics and then we’d go out. I’d heard of gin and I’d heard of tonic and I’d heard of them mixed together. I had never partaken. But if Matt is driving all the way over from the East Coast, I’d hate to be a bad host. Plus there was a party that night at the dorm that didn’t require any driving, so I guessed it was OK to have a few. I went to the Albertson’s liquor store, I picked up the distilled spirit in question, and we made gin and tonics, regardless that neither of us was adept at measuring gin versus tonic. Beyond cringing in the elevator at his rap (“hey, we’ve got gin and tonics in Greg’s room”), what I mostly remember is waking up after midnight on my roommate’s bed muttering about how “what I really want is to be in love,” and Matt listening to this without judgment. I’d be sober enough soon enough to give him directions to the 24-hour McDonald’s on Fowler Avenue, which is where one would go after adding too much gin to the gin and tonics. The next morning, he wakes me up bright and early so we can drive to Clearwater Beach, a spot he assumed I knew the location of. Only vaguely. I wasn’t any more of a beachgoer in Florida than I was in Long Beach unless Matt called.

Our last lunch was a half-dozen years after college. We’d kept in touch, but didn’t see each other very much. He was working in the same North Shore town I was, so it was convenient. I told him about a Mexican restaurant, and he was very much that’s it, that’s the place where we have to go, Mexican food absolutely. There was a little Damone from Fast Times at Ridgemont High to Matt: act like wherever you are, that’s the place to be. Setting baseball cards ablaze in a treehouse. Riding bikes on the boardwalk when we were supposed to be reviewing biology. Mixing gin and tonics like total amateurs. Mexican for lunch. I’d known Matt for sixteen years by then. It was a blast being reintroduced to his moves.

This was the summer of a bit of upheaval at my magazine, with an editor coming in who I didn’t necessarily trust. I droned on quite a bit during lunch about whatever indignities I perceived were being foisted upon me. Matt listened, because Matt was good at listening, though I had the sense it might have been a bit much with the droning on my end. Regardless, when we returned to my office for a few minutes after lunch and I introduced him to the momentary bane of my existence, Matt used all of his six feet and six inches to seem intimidating on my behalf. Later on, the editor and I would work out our differences and we remain friends to this day. At the time, however, the guy confessed he thought Matt was gonna kick his ass for me.

My wedding was a few months away at that point and I told Matt to be on the lookout for an invitation. I don’t think I ever got an RSVP. I was disappointed, but not surprised. The same scenario played out for my Bar Mitzvah. Matt didn’t really go in for those things. He did agree to be a groomsman at my sister’s wedding mostly because he assumed there’d be bridesmaids to work his charms on. I don’t think he signed my high school yearbook, either. That was Matt being Matt, I decided. Matt being Matt made him one of my favorite people ever. Matt being Matt also made me not reach out beyond 1991. I don’t want to bother somebody who doesn’t care to be bothered. I’ll see him when I see him, I figured, but I never did see him again. He didn’t show up for the two high school reunions I bothered with, and I knew damn well he wasn’t a social media person. I made cursory searches a few times, anyway. No dice.

His father I did bump into a few times, on the LIRR in the late 1990s. Lou had moved from Mad to Cracked as one might in his field. Became its editor, in fact. Matty was doing fine, he said, he’d send my regards. Lou died at 90 in March of 2015, the same year my father took ill. Eight months later, my recent rabbit-hole exploration revealed, Matt — married with two children and living one county east of me — died at the age of 52, apparently from cancer, which seems to have taken too many of my friends from my youth, guys with whom I was no longer in contact but had never forgotten. Matt was certainly unforgettable to me, down to my bones. My arm still hurts thinking about him.

by Greg Prince on 22 November 2023 2:01 pm “I call to order the 2023 meeting of the Faith and Fear in Flushing Awards Committee for the purpose of selecting the Richie Ashburn Most Valuable Met for the season just past. Before we proceed, is there any old business?”

“Yeah — who did we name last year?”

“Uh… Starling Marte.”

“Wow. That doesn’t look very visionary a year later.”

“Perhaps not, but FAFIFAC isn’t in the business of forecasting. It’s in the business of reflecting.”

“Still, I’m beginning to wonder if there’s a FAFIF MVM curse. Who did we give the award to the year before last?”

“Uh… Aaron Loup and four other relievers who pitched a lot and pretty well.”

“Loup? He was gone the next year.”

“C’mon. One of the other relievers in that writeup was Edwin Diaz.”

“The Diaz who got hurt during Spring Training this year?”

“Well, it wasn’t Yennsy Diaz.”

“Ohmigod, we really are putting a curse on these guys.”

“Nonsense. We gave it to Jacob deGrom three times.”

“And look at him now. Missed most of the year and won’t be back until who knows when.”

“We also gave it to Beltran, Wright and Reyes, and they’re all on the Hall of Fame ballot.”

“See? None of them is still playing. Maybe we prematurely ended their careers.”

“Let’s get serious about this season. How about a nomination for the Most Valuable Met of 2023?”

“I nominate Nobody.”

“You really believe this curse business?”

“No, I’m saying that after a year like 2023, it’s clear that Nobody was ‘most valuable’ to the Mets, certainly not valuable enough to make any kind of difference.”

“We can’t do that.”

“Why not?”

“Because we don’t do that.”

“That’s not an answer.”

“It is in this case. We’ve given a Most Valuable Met award since the end of our first season in 2005, no matter how not good the season was.”

“I know. But has any season felt less valuable than the one we just got through?”

“I never thought of it that way.”

“Think about it.”

“I have. And you’ve got a point. Twenty Twenty-Three felt uniquely lacking in value while it played out and I have little desire to revisit it in granular form.”

“Great. So we’re agreed that our Most Valuable Met should be Nobody. Can I get a second?”

“Hold on. We don’t do that.”

“You already said that.”

“And I’ll keep saying it. Every baseball season, even the shortest and least inspiring, has its most valuable players, and even the lamest Met years have their most valuable players. We always come up with somebody because somebody inevitably stands out. Remember, we named the award for Richie Ashburn because the beat writers voted Ashburn the first Mets MVP in 1962, and that team lost 120 games.”

“Fine. But just so you know, to me, the MVM of 2023 is Nobody.”

“Duly noted. Now let’s get serious. Who’s our Most Valuable Met?”

“I don’t know. Lindor? Senga?”

“Yeah, that’s pretty much what I was thinking.”

“Which one?”

“Both, with Francisco Lindor and Kodai Senga sharing the designation as Faith and Fear in Flushing’s Richie Ashburn Most Valuable Mets for 2023.”

“Great. Move to adjourn!”

“Wait!”

“What?”

“There’s got to be more to it than that.”

“Why?”

“Because we do that.”

“These are your reasons? ‘We don’t do that.’ ‘We do do that.’”

“Baseball is defined by its traditions, and it is our tradition to celebrate our MVMs.”

“Can’t we start a new tradition of getting it over with? Like we wished the 2023 Mets had simply gotten their season over with?”

“Hmm…that would embody the spirit in which the 2023 Mets season played out.”

“Glad you see it my way. Move to adjourn!”

“Not so fast.”

“Never so fast with you. Why can’t we adjourn?”

“Listen, an entire season of Mets baseball was played, and we’re here to honor the two Mets who were not only here from the beginning of the season to the end — which isn’t something too many Mets could say — but two Mets who excelled from beginning to end.”

“I seem to recall Lindor slumping for a while.”

“Everybody slumps.”

“Wasn’t there a pop fly he didn’t catch?”

“Everybody makes mistakes. He was nominated for a Gold Glove, for cryin’ out loud.”

“His batting average was pretty low in the middle of the season.”

“It rose in the second half, and he was never not productive. More than a hundred runs scored, nearly a hundred runs driven in, first Met in the 30-30 club since Wright — and he won the Silver Slugger! First Met shortstop since Reyes to do that.”

“Senga barely qualified for the ERA title.”

“But he did, in fact, qualify. Finished second in the National League in that category, same place he finished in Rookie of the Year voting.”

“He pitched professionally in Japan for more than a decade. Was he really a rookie?”

“In the eyes of MLB, he was. We’ll take their word for it.”

“That bit where he always needed extra rest never sat right with me.”

“Call it an adjustment period. You change countries, rely on an interpreter and get batters out for six months.”

“Had some bad outings.”

“Had many more good outings, especially as he got used to pitching in the majors. The Mets won seventeen of his twenty-nine starts, and this wasn’t a team that won nearly enough of anybody’s starts.”

“I couldn’t help but notice that on the night both Lindor and Senga were being toasted for reaching their individual milestones — Senga becoming the first Met rookie since Gooden to strike out 200 and Lindor belting his 30th home run to make himself 30-30 — that the Mets lost.”

“So?”

“So it sort of symbolized for me the futility of this team that its two most valuable players couldn’t push it over the top in the game where they were lauded for personal stuff.”

“That’s a highly selective interpretation.”

“Well, we are a selection committee.”

“As a responsible selection committed, we’re looking at a much broader body of work. Lindor missed all of two games in 2023. Two! Senga, even with the rotation accommodating the extra rest that he functioned better with, never missed a start. They posted up and then some. Some years that really stands out.”

“If you say so.”

“I do say so. And now I need you to say so.”

“Fine. Here’s to our co-MVMs of 2023. If they weren’t necessarily more deserving than Nobody, they were certainly way better than nothing.”

“I’ll take that as a ‘yea’ vote for Lindor and Senga.”

“Yay. I mean ‘yea.’”

“Move to adjourn.”

“Seconded.”

“The 2023 meeting of the Faith and Fear in Flushing Awards Committee for the purpose of selecting the Richie Ashburn Most Valuable Met for the season just past is now adjourned. We will reconvene in short order to consider candidacies for the 2023 Nikon Camera Player of the Year.”

“Yay.”

FAITH AND FEAR’S PREVIOUS RICHIE ASHBURN MOST VALUABLE METS

2005: Pedro Martinez (original recording)

2005: Pedro Martinez (deluxe reissue)

2006: Carlos Beltran

2007: David Wright

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Pedro Feliciano

2010: R.A. Dickey

2011: Jose Reyes

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Daniel Murphy, Dillon Gee and LaTroy Hawkins

2014: Jacob deGrom

2015: Yoenis Cespedes

2016: Asdrubal Cabrera

2017: Jacob deGrom

2018: Jacob deGrom

2019: Pete Alonso

2020: Michael Conforto and Dom Smith (the RichAshes)

2021: Aaron Loup and the One-Third Troupe

2022: Starling Marte

Still to come: The Nikon Camera Player of the Year for 2023.

Here right now: A new episode of National League Town.