The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 31 December 2020 3:05 pm When the planes hit the Twin Towers, as far as I know, none of the phone calls from the people on board were messages of hate or revenge — they were all messages of love.

—David, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Love, Actually

Today I turn the age Jenrry Mejia was wearing when he was suspended from baseball for life after testing positive for ingestion of performance-enhancing substances. Jenrry’s still alive and he’s no longer suspended from baseball, so maybe there’s hope for us all.

Ol’ No. 58. I can relate. (Image by The 7 Line.) We shall expel 2020 from the present in a matter of hours. Our collective problems will not magically disappear, but we can pretend at least for a couple of days that a new year can alter the course of time. Dick Clark built an additional wing onto his empire by appealing to such Rockin’ Eve thinking.

With the last day of 2020, the one of which I feel most proprietary on an annual basis, I wish to offer a little co-director’s commentary regarding thirty people whose times and lives I also grew a little proprietary about in recent months. Those would be My Guys, as I came to think of them: the subjects of my A Met for All Seasons essays.

You know the series. Gosh, I hope you do. Jason and I offered it up twice a week for thirty weeks, from sometime in April to sometime in November, partly because we’d mulled doing something like it for about nine years, more because in April there was no baseball to write about from a fierce urgency of now standpoint. Looking back was all we could do. I’m comfortable with that direction. When you reach the age reflected on Jenrry Mejia’s most recent Mets uniform top, hindsight beats 2020.

I spent seven months thinking about My Guys. I’ve continued to think about My Guys. I haven’t been out much, so I haven’t had much opportunity to talk about them out loud. It’s my birthday. Indulge me for another thirty paragraphs, would you?

***My first guy and the first we presented overall, on April 21, was Rico Brogna, representing 1994. Rico was the AMFAS pilot episode in my mind, one I kind of had in the can. I’ve been telling what I think of as my Rico Brogna story since the 1994-95 strike, and it seemed uncommonly pertinent to the present day. He was the midsummer revelation of a year that suddenly stopped and left me wondering when baseball would be back, specifically because I had one thing to look forward to: the return of Rico Brogna. My first recurring theme was embodied by that first AMFAS season as well. I’m fond of the less-remembered Met years and bringing to light what was considered a relatively big deal in its time. “Less remembered” is not to be confused with forgotten (which I don’t think any Met ever is completely) or shall we say obscure (which is more Jason’s beat than mine).

Donn Clendenon, on May 1, came with an agenda. My agenda, that is. I wished to poke a hole in a phrase that had come to bug me. “Without so-and-so, such-and-such never would have happened.” It bugged me because why do we assume we had to do “without” so-and-so? I realize it’s a term of appreciation and acknowledgement, but after a while, it struck me as an unnecessary tic. In 1969, we were with Donn Clendenon. That’s what mattered. His impact on 1969 mattered. His whole life mattered as well, and it was pretty substantial, but I made a conscious decision to not retell it when others had told it more deeply. I was inevitably more about the Season than I was the Met.

Willie Mays, on May 5, was another agenda item, sort of. I had tired of the reflex social media reaction to pictures of players in uniforms with which they are not universally associated. Willie Mays is the subject of a lot of that ironic “legend” stuff, as in “Mets legend Willie Mays,” it’s funny because he was mostly a Giant and, besides, he was old when he ended his career as a Met in 1973 (though sixteen years younger than I am now, and I’m just a kid). I’ve always been defensive on Willie Mays’s Mets behalf, as if claiming perhaps the greatest ballplayer ever as one of your own requires a brief. Also, May 5 was one day before Willie’s birthday, and I’m not beyond a cheap calendar-driven hook.

Al Leiter, on May 15, represented my first challenge. I had him for 2002, which was a mostly crappy year. Al wasn’t crappy in 2002, but it wasn’t exactly “his” year. So I thought about Al Leiter in 2002, and the first thing I thought of was him starting on Opening Day that year and me being there and being satisfied that he and I were together, which led me to check my notes and confirm Al had started with me at a game more than any Met pitcher had. Satisfaction wasn’t guaranteed, but I rarely left Shea disgusted.

Ah, Melvin Mora, May 19, the 2000 entrant. I say “ah,” because nobody left a comment, which tells me either nobody cared or I did a less than compelling job of making people care. Ah, whaddaya gonna do? Melvin occupies a very specific moment in time for the Mets. He was here for two seasons, yet not at the beginning of his first nor the end of his second. They happened to be two of the most momentous seasons in modern Met times: 1999 and 2000. Melvin played a pivotal role late in the first of his seasons and was sent away before he could do more in he second of them. I fell in love with him in the interim, yet didn’t really mourn his departure. We needed a shortstop, and Melvin, who could do it all, couldn’t really play short. Thus, Melvin Mora for Mike Bordick. Which led to a whole other thing I couldn’t get behind: hating the trade that brought us Mike Bordick because Bordick was here, not monumentally effective, then gone, while Mora thrived in Baltimore. As the series went on, I came to hate hating trades. It’s too easy and ultimately pointless to be pissed off all the time.

R.A. Dickey, on May 29, was my first AMFAS from the FAFIF era (so many acronyms!). Anybody I’d already written about a lot as he was being a Met was going to take some thinking. I didn’t want to fully recycle the Best of Dickey or whatever from 2010 to 2012 (his last season was his essay season). I wanted to provide fresh takes by doing this stuff. I split the difference for R.A., repurposing a few lines here and there to celebrate the way the knuckleballer made the language dance. That was what attracted me to R.A. ten years earlier.

Johan Santana, June 2, was, to me, something of a copout. I didn’t tell you anything I hadn’t already told you about the man whose uniform number my age was repping until midnight last night. I tried to do it a little differently than I had before, peeling layer by layer the onion that was Johan’s finest 2008 hour, his last start and our last win at Shea, but I was doing Johan on June 2 for one reason: because I couldn’t get otherwise interested in writing about the Mets during the George Floyd protests. I had planned to do Pedro Martinez on that day, but little seemed more irrelevant than thousands of words on a retired pitcher who did whatever whenever while America was trying to figure itself out in the present. The calendar reminded me we had just passed the anniversary of Johan’s no-hitter, and, like I said, I’m not beyond a cheap hook. I think what I wrote was fine, but my heart was not in the exercise that day.

Lenny Randle, June 12, was the manifestation of a determination I’d made during the preceding offseason that there was something to like about every Mets season, even the seasons we instantly dismiss or smolderingly detest. Lenny’s big year was 1977. I liked that he joined our ranks and flourished and gave me something to root for. I can’t just spit at seasons and eras. There are too many microclimates. Cloudy with a chance of Randle is sometimes all there is to enjoy. Enjoy it, I figure.

Jason Isringhausen, June 16, sort of picked up on the Randle theme in that for nearly a quarter-of-a-century you can’t mention Isringhausen and his running mates of popular imagination Bill Pulsipher and Paul Wilson without eliciting groans from Mets fans. I think when I began to write about Izzy and 1995, my headspace overlapped with the dismay that Generation K didn’t pan out. But as I got into the story, I found myself grateful for what Izzy (and Pulse) gave us in ’95. They gave us hope. We didn’t know that they wouldn’t engender a whole lot of it down the line. It was just a great scintilla of time to be a Mets fan, that hour when you’re sure something is about to get better. I doubt I’d convince too many people that it’s OK to be happy for what there was rather than rueful for what there wasn’t, but I was happy basking anew in the glow of young Izzy and all that seemed to be transpiring around him. Writing this essay was a turning point of sorts for me as a fan. My cup measured as half-full.

Mookie Wilson, on June 26, became the second of My Guys to bump Pedro Martinez. The schedule for better-late-than-never 2020 had just been issued. It was gonna be a short season, almost as short as the last time baseball jury-rigged itself in miniature, the second half of 1981. The terrain was ideal to go back to that split season and the biggest swing Mookie ever took…until five years later. Before 2020, I had a real soft spot for the less-remembered Met exploits of the shortened seasons. 1981. 1994. 1995. My cup’s not nearly as half-full for 2020.

Craig Swan, on June 30, got to be 1978’s AMFAS because he won the ERA title when few Mets were winning anything. Because of the ERA title, I’ve carried an image of Swan as one of the best pitchers the Mets have ever had. Was he? Define “best” and “ever” narrowly, and absolutely. He was definitely around a long time and I got a kick out of exploring a Met I hadn’t thought that much about over the preceding 36 years.

Now, on July 10, Pedro Martinez was ready for his closeup. The longer he waited, the longer his essay grew. I’d been wanting to do right by Pedro every fall for the preceding decade, because every fall in presenting the Most Valuable Met winner, I’d list the previous winners — just like the papers would when awards were announced — and I’d be reminded I’d long ago given Pedro one lousy paragraph for his sublime 2005. This is an example of me not getting out much even in non-pandemics because, yeah, I really thought about this. Pedro had kind of a Swan vibe to me; to truly get what he meant at his Met peak, you had to have lived it. I hope what I wrote got that across.

Tommie Agee, on July 14, was essentially written by a seven-year-old, as told to a 57-year-old. I sometimes ghost for others in my day job, so why not ghost for my younger self? The best way for me to present Agee to you was how I processed him in 1970. Plus some later stuff. Call it a collaboration between me at seven and me fifty years later.

Jacob deGrom, on July 24, became the easiest scheduling decision of the series for me. He was pitching on July 24. Ohmigod, somebody was pitching on a day in 2020! In practical terms, the coming of belated Opening Day meant fitting AMFAS around our game stories. I have to admit I felt the Mets of “now” were getting in the way of the Mets of “then,” but I guess it was good to have baseball back. Writing about Jacob deGrom, as I’d been doing since 2014 (his year in our spotlight), wasn’t much of a chore. There wasn’t a whole lot new to say, and I didn’t pretend to try to find a novel truth. It’s always a good day to write about Jacob deGrom. And an even better day to watch him pitch.

Darryl Strawberry, on July 28, is where time came to matter most to me in this series. My season of choice was 1983, and that meant looking at Darryl through the prism of looking forward to his debut, which was a preoccupation for three years as a Mets fan. Had I drawn 1987 or 1990, I would have approached Darryl differently. I liked hanging out with his potential in ’83. I loved knowing we were on the verge of something special with him and his team. I loved that we couldn’t be sure of it then because you can never be sure. I loved not defaulting to something I’ve really come to disdain, the bit where a Mets fan can’t look at the 1986 Mets without grumbling that they should’ve won more. We won in 1986. I would’ve liked more. Who wouldn’t? But that’s postscript. The story was and is Darryl Strawberry was frigging amazing.

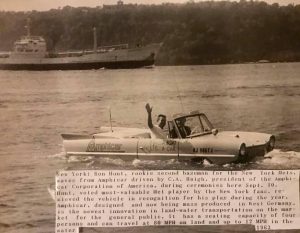

What I wrote about Ron Hunt, on August 7, was a year in the making, you might say, though he wasn’t even my original draft choice for 1963 (apologies, Tim Harkness). On August 9, 2019, I had the good fortune to spend a little time in the presence of Ron and his family as he greeted fans at Citi Field. I hadn’t written one word about it here because that was the night Todd Frazier hit his three-run homer off Sean Doolittle, Michael Conforto whacked a walkoff hit, Pete Alonso grabbed Conforto’s shirt, and a rapidly developing playoff chase took precedence. I kept meaning to write about the rest of that night, which was amazing to live through on so many levels, but never got around to it. The Hunt portion, still in my notebook, dovetailed with this assignment, the only one that involved a Met I never saw play as a Met. Instead of it being an academic exercise, I got to take it personally, and I’m delighted I had that opportunity.

I already did meta for Joe Orsulak, AMFAS subject for 1993. As I wrote on August 11, I wasn’t completely certain why I wanted to profile Joe, other than I’d always said he was one of my favorite Mets…except I still wasn’t sure why he so rose in my esteem. And I’m still not, but I do like him and I did like thinking about him again.

Ike Davis, on August 21, was a vestige of another age. When I selected him in the AMFAS draft of 2011, I congratulated myself on the coup. I had our future superstar! I’d have so much to write about! That was based on Ike’s rookie season of 2010 and all the expectations it raised. Fast-forward nine years. Ike Davis’s Met career was long over and faded into the background. I’d written probably twice a year about his ultimate shortcomings while Ike was not living up to expectations about his arc. I didn’t want to write about the same damn thing. I remembered that my late friend Dana Brand, who lived only long enough to see Ike fall down in Denver and essentially never get up, was once kind enough to praise my “unusual techniques and genres to present the experience of the Mets: lists, dialogues, fantasies, glossaries, etc.” Well, I reasoned, if it was good enough for Dana, it was good enough for Davis, thus instead of another expository essay, I imagined some wise guy at the track giving me a can’t-miss tip on this kid running in the ’10th. Paired with my epigram of choice that day — the Guys & Dolls number about having “the horse right here” (a favorite of my mother’s) — it allowed me to fashion an old tale in a new light. Thank you, Dana.

When I got to Jose Reyes on August 25, I had a plan. Each of my next four Tuesdays starting with that one would encompass sort of a mini-countdown: second-favorite position player; second-favorite pitcher; favorite position player; favorite pitcher. Events would disrupt my planning, just as events disrupted Jose’s road to unimpeachable Met immortality. I chose 2007 for Jose because it demonstrated the absolute apogee of his abilities and indicated the beginning of realizing he was far from perfect. Still close enough to the innocent Jose of whom I’d grown so fond that I felt comfortable being mostly effusive about Reyes before having to get real. I still love the guy. That might be dangerous.

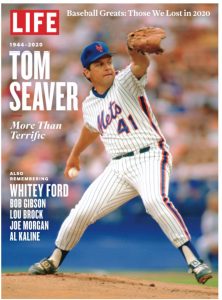

Tom Seaver was not slated for September 4, but how was I gonna write about any other Met two days after we learned of Tom’s death? Gil Hodges would regularly bump other pitchers to accommodate Seaver, so I guess it was appropriate that Tug McGraw had to wait another few days. I had decided to write about Tom in 1971, but how exactly? By transporting myself back to 1971. There was no point in telling the whole Seaver story that day because for two days we’d all been doing that. Instead, I got very specific. Tom the idol whose number I had to wear in Pee Wee League. Tom the “author” whose book I had to read as soon as my mother bought it for me. Tom the pitcher whose win total had to reach 20 games by the end of the year. That was the Tom Seaver I lived with in 1971. That was the Tom Seaver I called my favorite player then. I realized that was the Tom Seaver I call my favorite player still.

Tug McGraw came in from the bullpen on September 8. Just as his essay was postponed, “his” year was pushed back, at least from where it should have been. He’d have been better slotted in 1973, except we had Willie Mays there. Willie could have fit well in 1972, except we had Gary Gentry there. Gary would have been ideal for 1969, except we had Donn Clendenon there. Donn might have been just as at home in 1970, except we had Tommie Agee there. Tommie came over in 1968, but we had Cleon Jones there. And nobody was touching Tom Seaver in 1971. Musical chairs were a fact of AMFAS life for the Mets who contributed to our most memorable miracles (apologies to the seatless Met greats of the era). Anyway, I was doing the year Tug was traded, 1974, maybe the last Met season for which my detailed memories are fuzzier than they are clear. I do remember the Mets being a big letdown in general, nobody more so than McGraw, which is why when it came to writing about ’74, I pegged Tug to his trade as much as the career that preceded it. That I remember very well and that was the unusual trade in Met history where both teams involved made out pretty well. It also gave me an excuse to say a few words about John Stearns, the one Met I was genuinely sorry I didn’t find a season for in all this.

Mike Vail was September 1975 for me, so profiling him in September 2020 was a must. I noticed that when I wrote about Vail on September 18, I could feel my AMFAS voice changing, just as I suppose it was doing when I was 12 going on 13. My understanding of the Mets was deepening as I moved into adolescence. I was a little less childlike, just slightly more adult. I don’t know that I’ve progressed all that much even at this late date.

“FONZIE WAS SO GREAT!” and “FONZIE’S TEAMS WERE SO GREAT!” probably would have covered all I had to say on September 22, but I attempted to be a little more articulate than that regarding Edgardo Alfonzo and 1997. Not much more articulate, though. That’s a symptom of how viscerally I cherish Fonzie and that first year when his Mets broke through. Do the Fonzie, indeed.

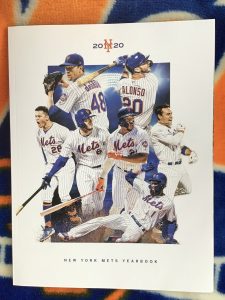

Pete Alonso on October 2 endured a bit of the Ike Davis syndrome, as doctors call it. When I grabbed Pete in the AMFAS supplemental draft Jason and I conducted in March, I was excited that I was gonna get to write about the most dynamic contemporary Met in captivity. Months later, the Polar Bear had melted a little in the heat. I waited until the 2020 season was over to assess where he stood after two years in the majors. It was more fun doing the part where I revisited the feats of his unprecedented rookie year. This is what you run into trying to take the long view of a career still in progress.

Dwight Gooden was first going to appear in July, adjacent to my mother’s birthday because she liked him so much. But he kept getting pushed back. He was going to appear for sure on September 8 because of that countdown-within-a-countdown plan I described above, but Seaver’s passing changed all that. Getting to Doc on October 6 was fine. He’d completed his singular 1985 in early October. His 1985 was so singular as a whole that, while it’s often cited as the best individual Met season ever, its elements are never really dissected, which is what I set out to do. It’s also impossible to write about Doc without “…and then, he tested positive,” but I swear I don’t see that as the defining episode of Doc’s Met career. I’m Team Half-Full.

Matt Harvey was such a tabloid drama that I thought that was the best way to approach him and his 2016 on October 16. Bringing “Scott Boras” and “Sandy Alderson” into the story — and going as meta as I could get away with — turned a potential frown upside down.

Lee Mazzilli, profiled on October 20, was an outsize figure for someone who was a fairly average ballplayer. Such was the context of rooting for the Mets when Mazzilli was at his best. I’m particularly gratified that Lee had a 1986 coda to his 1980 story. I didn’t write much in this series about the Mets when they were in their larger-than-life phase — Jason covered 1986 through 1992 — but getting to ride along with My Guys of that period in earlier, slighter times (Mookie and Mazz in particular) and feeling them experience the ultimate World Series payoff was vicariously gratifying. I wish the Mets won a lot more than they did as I was fitfully coming of age as what we’ll call an adult, but I gotta tell ya, I wouldn’t trade the journey from the late ’70s to 1986 for anything.

Steve Cohen interrupted what I was deep in the midst of writing on October 30. He also changed my long-term plan for the AMFAS finale. But on the Friday that he was approved by MLB’s owners to buy the Mets, there was no other story I could see me dropping in our readers’ laps. Thus, Steve Cohen became A Met for All Seasons, 2021 edition. My original notion was to give that honor to To Be Determined. It was gonna be a whole thing. I’ll gladly swap the conceptual for the reality.

John Olerud, bumped to November 3 by Cohen, was given room to run. As if Oly (cycle notwithstanding) could run. Then again, we did run to glory with John batting third almost every day in 1999. This was my last chance to really dwell in what may be my favorite era of Mets baseball — though sometimes I think whichever one I’m writing about is my favorite — and I wanted to make it count. Who better to drive us in than Olerud? (Side note: this published on Election Day, and I was determined to get Oly’s essay up before other, more pressing issues distracted even the hardest-core among us from Mets of the past.)

Ed Kranepool had to end the series. Never mind To Be Determined, my initially penciled-in entrant for November 13. Ed was and is the personification of A Met for All Seasons. Though any notion that I had a maximum word count for any given column disappeared back in spring, I really let my Krane flag fly as I traveled to his and the series’s final year of 1979. Midway through I decided I wanted to explicitly mention each year Ed played. When I got to the end, I realized I forgot to specify 1963, so I went back and put it in. I had so much fun doing this one. I had fun doing all of them, really. And I had fun sharing them with you.

Thirty-first paragraph alert: Thank you for your indulgence today, thank you reading year-round. See you in 2021.

by Greg Prince on 30 December 2020 7:08 pm Ray Daviault first came out of the bullpen for Casey Stengel on April 13, 1962. the second reliever used in the New York Mets’ first-ever home game. Ray’s mere presence made him the first Canadian in a Mets uniform. On July 7, after Marv Throneberry delivered a pinch-hit two-run homer in the bottom of the ninth at the Polo Grounds, Ray had his first win on this or any continent.

Les Rohr was the first player the Mets ever chose in an amateur draft, the second player chosen overall in 1965. On September 19, 1967, he became a big leaguer for the first time, beating the Dodgers at Shea Stadium, 6-3. Les would finish the year with his second win, besting Don Drysdale in Los Angeles come September 30.

Rick Baldwin would have had enough of a challenge reaching the majors at age 21. Assigning him No. 45 could have only added to the pressure. Forty-Five had just been vacated by Tug McGraw, traded in the preceding offseason. Being the first to follow a legend, even numerically, is the definition of a tough act to follow. Yet in his first appearance, on April 10, 1975, Rick threw a scoreless inning of relief and he settled in nicely, pitching in a third of all Mets games that season.

Claudell Washington had no act to follow. He was a trailblazer in his time, his time being 1980 in terms of the Met clock. He was the first acquisition of the Doubleday-Wilpon regime and, through his part in a Magic summer, Claudell indicated the new general manager Frank Cashen knew what he was doing when it came to reeling in talent.

Tony Fernandez was supposed to help make things better in 1993. Honestly, he didn’t, which was too bad, not only for the 1993 Mets, but for a shortstop who had distinguished himself greatly as a Blue Jay and Padre. The Mets would trade Tony to Toronto after a couple of months and Tony would help make things even better for the defending world champions, helping the Jays to their second consecutive Series win. Like Claudell Washington, Tony Fernandez enjoyed a long post-Mets playing career.

Phil Linz’s calling card was a last. It was his off-field playing, of a harmonica, that was credited in legend for spurring the Yankees to the final pennant of their seemingly endless American League dynasty. With Phil tooting away on the mouth harp on the team bus; manager Yogi Berra telling him to, in so many words, put the damn thing away; and Mickey Mantle making sure Phil heard differently (“Yogi says play it louder”), the backup infielder caused the usually mellow Berra to blow his stack. The slumping Yankees suddenly caught fire and Phil Linz was forever a musical icon.

That was in 1964. In 1967, with the Yankee empire too far gone to be saved by a charming anecdote, Phil Linz became a Met. He’d keep company for a season-and-a-half with beloved Mets coach Yogi Berra, the two of them posing happily for photographers once reunited at the Mayor’s Trophy Game. Unsurprisingly, a harmonica was in the picture. The Mets released Linz after the 1968 season, though Gil Hodges invited him to Spring Training for the following year. Phil declined, seeing as how he had thriving nightspot Mr. Laffs to tend to in the city. And besides, as the former New York/New York player put it to author Bill Ryczek decades later, “I was tired of sitting on the bench for a ninth-place team.”

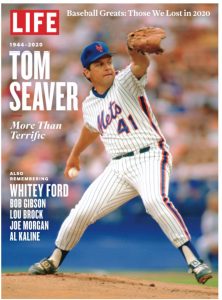

The Mets wouldn’t be a ninth-place team in 1969. Gil Hodges had plenty to do with that. So did his ace pitcher, Tom Seaver. Tom Seaver had a lot to do with everything from 1967 until almost the middle of 1977 and then again in 1983. How completely did Tom dominate the Met scene during his long, if interrupted tenure? Let’s answer that literally. Seaver started 395 games for the New York Mets and completed 171 of them. By comparison, since 1992 — the year Tom Seaver became the first player inducted into the Hall of Fame bearing a Mets cap on his plaque — 148 different pitchers have started 4,528 games for the Mets and together they completed 167 of them. The Mets wouldn’t be a ninth-place team in 1969. Gil Hodges had plenty to do with that. So did his ace pitcher, Tom Seaver. Tom Seaver had a lot to do with everything from 1967 until almost the middle of 1977 and then again in 1983. How completely did Tom dominate the Met scene during his long, if interrupted tenure? Let’s answer that literally. Seaver started 395 games for the New York Mets and completed 171 of them. By comparison, since 1992 — the year Tom Seaver became the first player inducted into the Hall of Fame bearing a Mets cap on his plaque — 148 different pitchers have started 4,528 games for the Mets and together they completed 167 of them.

Whoever said they don’t make ’em like that anymore wasn’t kidding.

Image by Warren Zvon. Numbers say so much on behalf of Tom Seaver. So do images, such as those designed by the fabulous illustrator Warren Fottrell (a.k.a. Warren Zvon), a beautiful soul we lost in 2020. Warren did most of his speaking through graphic art, but he stopped by our blog on the occasion of Tom’s 75th birthday and left this comment:

Some people have a special type of integrity that can’t be described with words. Tom, throughout all his years in the spotlight, before and beyond, has been this type of person. Not only true to himself but true to the world around him. Not afraid to speak the truth. He wanted to be a winner but knew that the only way to truly be one was to take responsibility for being a loser when that was a required truth.

Over the years I’ve learned a lot from the mightiest of Mets aces, things he never intended to teach me and things I never set out to learn.

As a kid going to Shea, watching the Mets play, I wasn’t as big a fan as I am now. I took George Thomas Seaver for granted then.

He was simply our best pitcher.

But now, because of the way he has lived his life, the way he has consistently been the person he strives to be, I no longer do. I’ve learned that he is so much more than just a great Mets pitcher of the past, and when he goes a piece of me will go with him. A big piece.

So, yeah, Tom was the complete package, the greatest Met we’ve ever known, the greatest Met we’ll ever know. But his death is not the complete story when we look back at this year that has had far too much sadness, baseball-related or not. We are well aware we lost The Franchise in 2020. We should also remember the six other Mets who passed away this less than terrific year. Ray Daviault. Rick Baldwin. Les Rohr. Claudell Washington. Phil Linz. Mets fans rooted for them when they entered a game. Mets fans applauded when they did something good. Mets fans might have wished each of them had done a little more or stayed a little longer as Mets, but what they did in our uniform of choice deserves acknowledgement and another round of applause.

Seaver shared an affiliation with those guys, just as he shared an affiliation with the half-dozen Hall of Famers beside himself who died in 2020. I can’t imagine this year didn’t set a record for most baseball fans left mourning the loss of a personal favorite. Every player who’s ever played is some fan’s favorite, probably, but this year saw the passing of not just those we dare to call immortals, but those who defined their ballclubs.

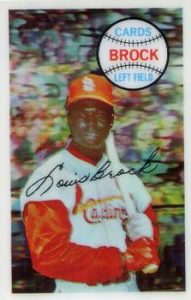

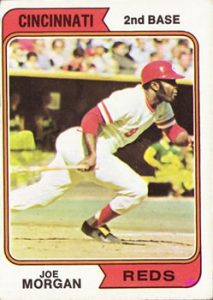

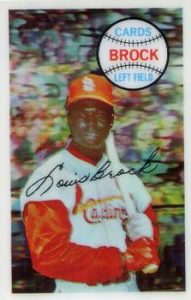

Bob Gibson. Lou Brock. Joe Morgan. Whitey Ford. Al Kaline. Phil Niekro. They, like Seaver, were ballplayers kids idolized and adults revered. Gibson with the ERA nobody’s surpassed (the only figures lower were the batters he sent sprawling to the dirt). Brock who ran on everybody and collected more bags than Carrie Bradshaw. Morgan who sent the Big Red Machine into a whole other gear and made necessary the split screen for postseason telecasts, just so NBC could keep showing him leading off first. Ford with the World Series performances that were so historic that they knocked Babe Ruth out of the record books (the pitching record books). Kaline who won a batting title as a veritable baby and kept piling up base hits into middle age. Niekro the eternal elder who practically never stopped getting outs on the pitch he mastered better than anybody who’d ever lived.

It wasn’t just that they, like Seaver, were great. They were epic. They left indelible impressions on anybody who loved the game.

Bob Gibson became our assistant pitching coach, you might recall. It was 1981. Old teammate Joe Torre recruited him to give the Mets staff some attitude. It was not transferable, but the thrill of Gibby in a Mets uniform was something to behold. I was less thrilled at the thought of him knocking down an Agee here or a Milner there, but Bob had his reasons. Also, he was wearing a Cardinals uniform then. I wasn’t supposed to like him. Bob Gibson became our assistant pitching coach, you might recall. It was 1981. Old teammate Joe Torre recruited him to give the Mets staff some attitude. It was not transferable, but the thrill of Gibby in a Mets uniform was something to behold. I was less thrilled at the thought of him knocking down an Agee here or a Milner there, but Bob had his reasons. Also, he was wearing a Cardinals uniform then. I wasn’t supposed to like him.

Lou Brock I never stopped liking, even on those occasions he was sliding into second ahead of the tag on a bullet delivered by Jerry Grote. Brock v. Grote never was fully settled, but we knew it was a case of the premier base stealer in the land versus an arm that was the envy of his catching peers. Only one of the people at the center of the battle that mesmerized Mets and Cardinals fans for a generation smiled much. Hence, though I pulled for Jerry to throw him out, I could never dislike Lou.

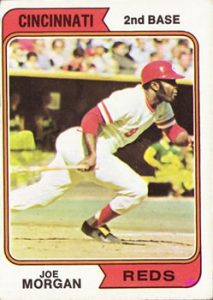

Joe Morgan was something else. At his height (no pun intended), Little Joe was a bigger deal on those powerhouse Reds than any of his co-stars, and his co-stars were frigging Pete Rose, Johnny Bench and Tony Perez. Getting Morgan to Cincinnati was like adding whipped cream to ice cream and syrup. It was already fantastic, but now you won’t believe what this concoction tastes like. I can still see him breaking from the box on his 1974 card. He’s probably gonna come all the way around. Joe Morgan was something else. At his height (no pun intended), Little Joe was a bigger deal on those powerhouse Reds than any of his co-stars, and his co-stars were frigging Pete Rose, Johnny Bench and Tony Perez. Getting Morgan to Cincinnati was like adding whipped cream to ice cream and syrup. It was already fantastic, but now you won’t believe what this concoction tastes like. I can still see him breaking from the box on his 1974 card. He’s probably gonna come all the way around.

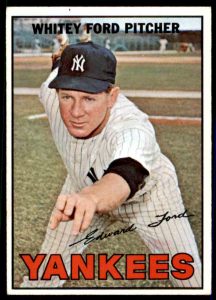

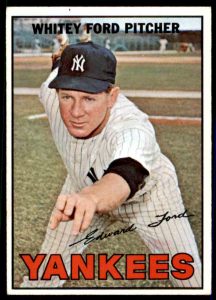

Whitey Ford was a name out of the past when I first heard of him, so far out of the past that my father said he saw him in high school. Not “went to see the Chairman of the Board at the Stadium” see him in high school, mind you. My dad was in high school and Ford was in high school and their schools played each other on one diamond or another. They were contemporaries, a couple of kids from Queens. Ford retired two years before I started watching baseball, which I found hard to believe once I learned his career spanned 1950 to 1967. I had scattered memories of 1967. My dad was my dad. Hard to put that together when you’re barely more than a tyke. I discovered not too long ago that Ford tried a comeback of sorts in 1968, pitching at Shea in the Mayor’s Trophy Game against the Mets. They didn’t score off him. Not too many did. Whitey Ford was a name out of the past when I first heard of him, so far out of the past that my father said he saw him in high school. Not “went to see the Chairman of the Board at the Stadium” see him in high school, mind you. My dad was in high school and Ford was in high school and their schools played each other on one diamond or another. They were contemporaries, a couple of kids from Queens. Ford retired two years before I started watching baseball, which I found hard to believe once I learned his career spanned 1950 to 1967. I had scattered memories of 1967. My dad was my dad. Hard to put that together when you’re barely more than a tyke. I discovered not too long ago that Ford tried a comeback of sorts in 1968, pitching at Shea in the Mayor’s Trophy Game against the Mets. They didn’t score off him. Not too many did.

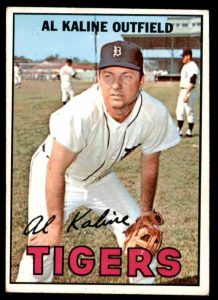

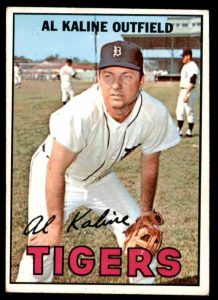

Al Kaline was part of the foundation of my baseball cognizance, one of the ’67 Topps my sister bequeathed me once it was clear I cared about the cards and she never would again. I gleaned from the back that he was the Tiger among all Tigers. He remained so into 1974 as he chased 3,000 hits and 400 homers. The former he got, the latter he missed by one (a moderate-sized disappointment to me the summer I was eleven and tracking his progress). Also in his last year playing for Detroit, I stared intently at a battery. It had the name of a great ballplayer. Alkaline. To this day I revel a bit when I pick up an alkaline battery. “It’s Al Kaline!” Al Kaline was part of the foundation of my baseball cognizance, one of the ’67 Topps my sister bequeathed me once it was clear I cared about the cards and she never would again. I gleaned from the back that he was the Tiger among all Tigers. He remained so into 1974 as he chased 3,000 hits and 400 homers. The former he got, the latter he missed by one (a moderate-sized disappointment to me the summer I was eleven and tracking his progress). Also in his last year playing for Detroit, I stared intently at a battery. It had the name of a great ballplayer. Alkaline. To this day I revel a bit when I pick up an alkaline battery. “It’s Al Kaline!”

Photo by Sharon Chapman. Phil Niekro dared stand in the way of Met destiny in 1969, throwing the very first pitch they’d ever seen in a postseason game. Fortunately, the Mets persevered in Game One of that maiden NLCS, but the outcome was no given, considering Niekro won 23 games that year (finishing second to Seaver for the Cy Young) and was on a path that would take him past 300 before he was done. He was another of those opponents I couldn’t help rooting for on the side. When I attended college in Florida, Phil was still pitching for the Braves, whose games I listened to on the radio. This was when Torre had taken over in Atlanta and I felt a kinship with his new club. I rooted hard for the 1982 Braves to win the pennant, mainly so Phil Niekro could finally pitch in a World Series. The Braves lost that NLCS, too, making Phil 0-for-2 in his best stabs at a championship. Nevertheless, he made the Hall of Fame without a ring. He also made it to Citi Field one September day in 2012 to help promote a documentary called Knuckleball! His role, on film and in actuality, was to mentor another late bloomer named R.A. Dickey. Watching them reunite during BP was a joy, as was the chance to ask Niekro a question about what it was like facing Seaver in the playoffs. He threw me a curve, telling me he saw his assignment as facing the Met hitters and “Seaver batted ninth.”

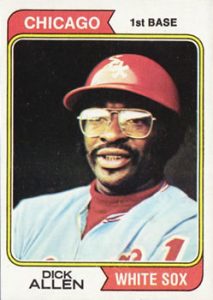

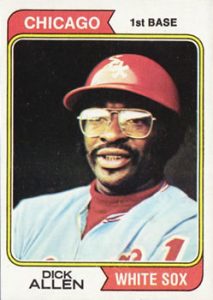

Maybe someday soon when we remember Hall of Famers who left us in 2020, we’ll add Dick Allen to the discussion. Allen isn’t in, but he’s come close via a veterans committee vote and is considered a favorite to cross the plate eventually. To Phillies fans in the ’60s, Allen was every bit the immortal that Seaver was to us and the aforementioned six were where they reigned. True, Allen didn’t necessarily mesh with Philly during his initial go-round, but those were complicated times. Nobody doubted he could mash (especially against the Mets), and everybody saw him put it together once he landed on the White Sox in 1972. When he died, I was moved to call up the image of his 1974 card. There he was, relaxed in the dugout and looking as he was to me when I was eleven: the coolest man in the majors. Maybe someday soon when we remember Hall of Famers who left us in 2020, we’ll add Dick Allen to the discussion. Allen isn’t in, but he’s come close via a veterans committee vote and is considered a favorite to cross the plate eventually. To Phillies fans in the ’60s, Allen was every bit the immortal that Seaver was to us and the aforementioned six were where they reigned. True, Allen didn’t necessarily mesh with Philly during his initial go-round, but those were complicated times. Nobody doubted he could mash (especially against the Mets), and everybody saw him put it together once he landed on the White Sox in 1972. When he died, I was moved to call up the image of his 1974 card. There he was, relaxed in the dugout and looking as he was to me when I was eleven: the coolest man in the majors.

Qualifying for Cooperstown isn’t a prerequisite for leaving an impression, not when you were a kid who collected cards and listened to games and took the announcers at their word. Bob and Ralph and Lindsey were always respectful of and effusive over the likes of Denis Menke and Bob Watson and Glenn Beckert (even if he was a Cub) and Lindy McDaniel (who always seemed to be notching a save for the Yankees) and of course Jimmy Wynn the Toy Cannon, as if it that was how it appeared on his driver’s license. Jay Johnstone was considered a real card (even if he never played for St. Louis). Biff Pocoroba caught in Atlanta and got a rise out of everybody when they heard his mellifluous name called. Horace Clarke was a misunderstood staple in the Bronx at second. Roger Moret was almost unbeatable for a spell in Boston. I had plenty of Bart Johnsons and Ed Farmers in my shoeboxes. I probably had a few Adrian Devines, too. Tony Taylor was endlessly dependable. Ron Perranoski helped revolutionize relieving. A little before my time but just in time for me to cherish his ’67 card was Lou Johnson of the Dodgers. A little later, but just in time to frustrate the Mets for the final time during the 1986 regular season, was the Expos’ Bob Sebra, who outdueled Ron Darling the final week of the year to remember.

Kim Batiste of the Phillies. Damaso Garcia of the Blue Jays. Matt Keough of the A’s. Ted Cox who stirred prospect hype with the Red Sox before they traded him to Cleveland. Tommy Sandt. Ed Sprague. Bob Oliver. Mike Ryan. They were pictured on cardboard. They were performing on television. They were important because we love baseball. They were important to those who knew and loved them, too, of course. For their families and friends, they didn’t have to be baseball players on baseball cards. Isn’t it something that actual people stand behind those images?

Eddie Kasko, who I remember as a manager of the Red Sox, died in 2020. John McNamara, who we all remember as a manager of the Red Sox, died in 2020. Billy DeMars, who I remember coaching for the Phillies forever, died in 2020. Jim Frey, batting coach and father figure to rookie Darryl Strawberry before he left to steer the Cubs past the Mets in ’84. Hal Smith, who isn’t the hero of the 1960 World Series but made it possible for Bill Mazeroski to be because he also hit a dramatic home run. Don Larsen, who threw a perfect game in the World Series in 1956 (as if that’s a sentence to type in a nonchalant font).

Four of the heretofore 17 surviving New York Giants: Gil Coan, Johnny Antonelli, Mike McCormick, Foster Castleman. Antonelli won 25 games for the 1954 world champions; the Mets acquired him for 1962, but Antonelli opted to retire. McCormick won a Cy Young in ’67, still a Giant in San Francisco. Now there are 13 surviving New York Baseball Giants. I get together with other lovers of the New York Baseball Giants over Zoom these days. We used to get together at an East Side bar called Finnerty’s, an establishment usually devoted to serving Bay Area fans. That place, like too many that depend on people being out and about, didn’t survive 2020’s pandemic ravages. Same for a Midtown sports bar very close to the hearts of myriad New York baseball fans, yours truly included, Foley’s.

“Young man!”

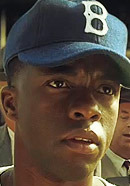

That was my favorite line from the movie 42 because it was what the actor playing Jackie Robinson said to the actor playing a young Ed Charles. We know who mature Ed Charles grew up to be. We also got to know the actor playing Jackie Robinson as one of cinema’s brightest stars, Chadwick Boseman. He died on rescheduled Jackie Robinson Night in 2020 at the age of 43.

Young man, indeed.

I went to a game in 2019, which seemed unremarkable as an event because going to a game is what a person who loves baseball routinely did prior to 2020, except this was kind of a special game for numerous reasons. One of them was I found myself sitting in the same section as the family and friends of the visiting Pittsburgh Pirates, right next to the wife and child of outfielder Starling Marte. Mrs. Marte urged her youngster to cheer “Daddy” on every time he batted. Steven Matz was pitching a shutout, so I didn’t particularly want Marte to succeed, but I have to admit I did get a kick out of the cry. When Big Daddy Marte was rumored to maybe be coming to the Mets, I hoped a little it would happen given my (admittedly tenuous) connection. When I learned in May that Noelia Marte, all of 32, had died of a heart attack, I felt the connection again. I went to a game in 2019, which seemed unremarkable as an event because going to a game is what a person who loves baseball routinely did prior to 2020, except this was kind of a special game for numerous reasons. One of them was I found myself sitting in the same section as the family and friends of the visiting Pittsburgh Pirates, right next to the wife and child of outfielder Starling Marte. Mrs. Marte urged her youngster to cheer “Daddy” on every time he batted. Steven Matz was pitching a shutout, so I didn’t particularly want Marte to succeed, but I have to admit I did get a kick out of the cry. When Big Daddy Marte was rumored to maybe be coming to the Mets, I hoped a little it would happen given my (admittedly tenuous) connection. When I learned in May that Noelia Marte, all of 32, had died of a heart attack, I felt the connection again.

“Pat Cawley of Glendale” was the State Farm Agent of the Day on basically every SNY telecast for years; Gary, Keith and Ron spoke of him as if he was a relation. Suddenly one night this offseason I saw Pat passed away. He was only 55. Luke Gasparre greeted me and who knows how many fans from his post atop Section 310 at Citi Field. Luke ushered at Shea Stadium for the life of the old ballpark and did the same through the first decade of the new ballpark. The World War II veteran died this year, too, having lived to be 95. Claire Shulman became Queens borough president in 1986 and had the honor of presiding as the Commissioner’s Trophy came home to Flushing — she also showed homeland loyalty by making municipal bets on behalf of the Mets during various Subway Series conflicts. Shulman died in 2020 at 94. Roger Kahn, who made Brooklyn even more famous than it already was via The Boys of Summer, signed off the beat for good at 92.

“As an old National League fan,” Pete Hamill reflected in 2000 of the interborough Fall Classic just completed, “I was rooting for the Mets.” Hamill’s report in The Subway Series Reader, which was maddeningly evenhanded, took the time to celebrate the Mets’ lone win, in Game Three, particularly Benny Agbayani’s exploits. “Instantly,” Hamill wrote, “hope rose for millions of Mets fans.” Sort of like it did for readers every time they saw Pete Hamill’s byline. We wouldn’t see it again after his passing in 2020 at the age of 85.

In the midst of that World Series, I wrote as much as I could to every Mets fan whose e-mail address I had. One of those fellow Subway Series travelers was a former colleague named Jim Ryan. Jim had sold advertising at the magazine I edited. He wasn’t a me-level Mets fan, but Shea was where his sympathies resided, which was no small thing when you worked in an office in New York in the Baseball Chernobyl years that followed 1996. I still remember Jim’s reply to whatever I wrote coming out of Game Three. He scored a ticket for the game and reported on a peanut vendor who, like Berra to Linz in 1964, told some overly loud Yankee bellower to stick it. Jim was so impressed that he claimed to have bought out the vendor’s entire stock on the spot.

Jim knew how to execute a grand Met gesture. Two years earlier, in 1998, Jim asked a friend of his who worked for the Mets to arrange for a dream of mine to come true. The dream was embedded so deeply in my subconscious that I don’t know that I dared speak it unless specifically asked. In the course of conversation, however, I revealed to Jim that I had never set foot on the field at Shea Stadium. Others would have nodded and shrugged. Jim made it happen. He arranged through his friend to get us on the VIP list for the DynaMets Dash one Sunday after the Mets played the Braves. We were very big kids to be taking part in this decidedly youth-oriented promotion, but they didn’t have the dash when I was 14 & under. So we ran the bases as if we weren’t too old for such glorious nonsense.

When I divined in September that Jim Ryan, 54, died of a heart attack, I was back on the field with him again, each of us dashing (he was way more dashing than I was), each of us laughing that we were part of this. I was in the office with Jim, too, sharing a stray moment related to some client of his or some story of mine or some ’70s song we both loved. When word spread through channels that Jim had passed away far, far too young, I noticed two of my fellow co-workers from those days used the same term to describe Jim: a friend to all. It was true. Everybody liked him and nobody didn’t like him. We were never incredibly close, but in those passing minutes that make a day and a week and a big chunk of your life before you know it, he was a friend to me, and I appreciated it. I still do.

by Greg Prince on 29 December 2020 1:34 pm Considering he didn’t file a single column all year, Oscar Madison had a pretty good 2020. You might even say he showed up ready to play more often than Jed Lowrie did…but who among us in a Mets cap didn’t?

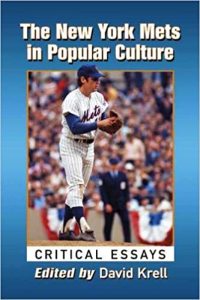

Oscar and his milieu enjoyed a recurring role across the pages of The New York Mets in Popular Culture, a recently published buffet of eclectic “critical essays” edited by the diligent David Krell. Leaning on the academic side of the street, a little up the block from what we do in this space, the book explores the margins of the Mets baseball experience. The more ephemeral it goes, the better it gets. The essays in which the Mets-loving reader learns more about Rheingold; Joan Payson; Bob Murphy’s beginnings; the truly original Mets of the American Association; calling Sports Phone, winning the Mayor’s Trophy; and one man’s adoration of Dave Kingman make this, as Murph might have put it, an excellent addition to your baseball library. The Mets-curious reader receives as well a bit of an anthropological explanation for what makes the Mets the Mets in movies and other media. Krell and his collaborators make a thoughtful case for the Mets mattering in every corner of the universe they touch — and The Odd Couple indeed gets its due in its various incarnations. Oscar and his milieu enjoyed a recurring role across the pages of The New York Mets in Popular Culture, a recently published buffet of eclectic “critical essays” edited by the diligent David Krell. Leaning on the academic side of the street, a little up the block from what we do in this space, the book explores the margins of the Mets baseball experience. The more ephemeral it goes, the better it gets. The essays in which the Mets-loving reader learns more about Rheingold; Joan Payson; Bob Murphy’s beginnings; the truly original Mets of the American Association; calling Sports Phone, winning the Mayor’s Trophy; and one man’s adoration of Dave Kingman make this, as Murph might have put it, an excellent addition to your baseball library. The Mets-curious reader receives as well a bit of an anthropological explanation for what makes the Mets the Mets in movies and other media. Krell and his collaborators make a thoughtful case for the Mets mattering in every corner of the universe they touch — and The Odd Couple indeed gets its due in its various incarnations.

The fiftieth anniversary of The Odd Couple series was celebrated by that living, breathing Smithsonian Institution of show business, Gilbert Gottfried’s Amazing Colossal Podcast when Gilbert and his co-host Frank Santopadre (a devoted if inevitably disgusted Mets fan I’m delighted to call my friend) invited on the sons of Jack Klugman, Adam and David, to recall how their dad and Tony Randall made television history as Oscar and his reluctantly tolerated roommate Felix Unger.

In an even more specific district of the podcast universe, diehard OC fans like myself were introduced to 1049 Park Avenue, in which Ted Linhart and Garrett Eisler began to painstakingly break down every episode of the ABC sitcom. Well, not every episode. They have little use for the first, laughtracked season, and they’re a little choosy about the second season. Also, they’re not at all into sports, which I find odd since Oscar’s a sportswriter who we revere for wearing a Mets cap, but to each podcast its own. Though the title — taken from Oscar’s fancy Manhattan address — is quite clever, my wife expressed surprise they don’t call their show The Pod Couple. (I did a search. The title was already taken.)

As you can see, regardless of what’s on the air in a given year, Oscar lives, whether a person likes baseball or not, just as Felix lives, opera buffdom optional. Still, it never hurts to idealize Oscar. Take it from one of his press box successors, so-called real-life division, Sports Illustrated all-timer Steve Rushin, whose second coming-of-age memoir, Nights in White Castle came to paperback in 2020 and therefore into my price range. “Marriage,” Steve recalls through the filter of his college-age thinking, “seems inevitable and impossible. Even my literary hero, the divorced sportswriter Oscar Madison on The Odd Couple, had to get married before he became single, free to roam — in his Mets cap and sweatshirt, sandwich in hand — through his eight-room apartment in Manhattan.”

A little subtler sighting, but a sighting is a sighting: In The Happy Days of Garry Marshall, a tribute aired on ABC, May 12, 2020, a publicity shot from The Odd Couple features Oscar Madison in his Mets cap. (Another still photo shows Marshall — who wore a lot of baseball caps — wearing a 2000 Subway Series cap, which included the Mets NY logo.)

An Oscar named de la Renta was world-renowned in the realm of fashion, but it’s Oscar Madison’s headwear choice that remains eternal. We wouldn’t let a year go by, even a year such as 2020, without grabbing a sandwich for ourselves and rewinding to all the times we sighted the New York Mets in the popular culture. When we do, whether it’s from art produced in the year just past or from art from a ways back that became evident to us over the preceding twelve months, we tip Oscar’s Cap.

The 2020 Oscar’s Cap Awards, our ninth such annual salute, got the earliest possible start, on a New Year’s Eve that seemed like it was ushering in just any other year. It was then, at Barclays Center, that the Strokes rung out 2019 by debuting a song called “Ode to the Mets”. It would soon appear on their 2020 albumThe New Abnormal, produced by Rick Rubin (known far and wide as a musical icon, known to me in second grade as new kid in the class Ricky, who borrowed and diligently returned my copy of Kosher Comics). The Mets aren’t actually mentioned in the lyrics, but lead singer Julian Casablancas said he wrote the song on the Mets-Willets Point subway platform after what The Athletic termed “a disheartening trip to Citi Field”. The motivator was eventually revealed to be the 3-0 loss inflicted by Madison Bumgarner in the 2016 Wild Card Game. “I’ve had my heart broken many times, obviously, as a Mets fan,” Casablancas told mlb.com.

More evidence that people used to routinely take trips to Citi Field, or at least on the 7 train to somewhere, emerged in January when commuters had the chance to hear the following over MTA-approved speakers: “This is Mets-Willets Point — HOME OF THE METS! I love the Mets, ’cause I’m from Queens, and you’re riding the 7 train.” That was Awkwafina, promoting her very funny Comedy Central show Awkwafina is Nora From Queens. You can tell it’s from January because nowhere in her announcement does she remind you to wear a mask. On the show itself, in the fifth episode of the first season (February 19, 2020), one of the dads at the Elmhurst Community Center laid this bit of emotion on its viewers:

“He’s got his little Mets cap on, and he just pulls away from me, darts across the street, runs right at me, jumps in my arms. So that was the first time Timmy hugged me after the divorce.”

The Late Show with Stephen Colbert senior producer Jake Plunkett wore a Mets cap while he drove his mother Bootsie to meet Dr. James Hamblin to learn more about the coronavirus on March 16, 2020. To be sure, by March we learned 2020 was a good time to, if you weren’t deemed essential to others’ well-being, stay home, catch up on one’s streaming or, better yet, reading. Sure, you couldn’t take a cruise, but thanks to Friend of FAFIF Kevin Chapman, you could definitely be a passenger on Lethal Voyage, the third book in the Mike Stoneman detective series. And as long as you’re setting a course for adventure with Det. Stoneman, you might as well sit in on board for a hand of poker with 1986 world champion New York Met Lenny Dykstra — wearing his championship ring as he sails the high seas, no less. Mike, addressing Lenny as Nails, tells him, “I just want to say that I always appreciated your hustle on the field. When you hit that home run off Houston in game 3, I jumped three feet off my bar stool.” Gosh, who didn’t?

Just as there was no cruising to a game in Flushing this summer, there were no jaunts to the U.S. Open across the boardwalk. Yet that doesn’t mean there wasn’t Two For Tennis (The Adventures of Mark) by Michael Elias, another author we’re proud to count in our community of readers and commenters. In Michael’s book, protagonist Mark seeks solace and distraction in the doings of the Mets before and after the last days of Shea. Mark follows his favorite ballclub’s pursuit of playoff berth redemption behind Johan Santana and Carlos Delgado in September of 2008; sees the Mets fall short in their Wild Card bid on Shea’s last day and realizes while doing a crossword realizes that the 41-down clue for “Stadium in Queens” is ASHE rather than SHEA. Nelson Figueroa also gets a shoutout.

We’ll give a shoutout to Steve Cohen for maybe sparing us lines like these in the future: “Married a Mets fan. He’s a glutton for punishment.” That view of the world was stated by Jerry Orbach as Lennie Briscoe on Law & Order, referring to Rafael Celaya (who “loves the Mets, always listening to their games in the summer”). That’s from “Couples,” Season 13, Episode 23, May 21, 2003, just as the Fred & Jeff Wilpon ownership cabal was making its presence truly felt. Its vibe was still being felt on May 7, 2020, when Seth Myers devoted his “A Closer Look” segment on Late Night to baseball’s pandemic-fueled absence:

“Who are we supposed to root for when baseball comes back, the Mets? I mean, they’re the only team that’s doing better during quarantine. I’m pretty sure the last president they met with was William Henry Harrison, and then he died ten days later. That was the year Mr. Met caught typhoid.”

This endorsement of the way Wilpon things were followed directly on the heels of the finale of the brilliant Brockmire, which aired May 6, 2020, in which title character Jim Brockmire (portrayed by Mets fan Hank Azaria) begged protégé-turned-tycoon Charles, “Oh please buy the New York Mets. Somebody should. Those people have suffered for long enough.” (“The Long Offseason,” Season 4, Episode 8). It didn’t take a sharp eye to notice a large portrait of Shea Stadium’s upper deck hangs in a conference room during the final season of Brockmire.

“Can you buy the Yankees?

“No.”

“Can you buy the Mets?”

“Oh yeah!”

—Dell Scott (Kevin Hart) determining just how rich his fabulously wealthy employer Philip Lacasse (Bryan Cranston) is in 2017’s The Upside

On Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj (Volume 2, Episode 2, released May 24, 2020), the host explains the dollar value of the legal marijuana marketplace in the US as such: “With that much money, you could buy the Mets thirteen times.”

Yet for all the grief the Mets took right up until Cohen took over, contemporary creative types can’t resist paying homage.

On Netflix’s Big Mouth, Andrew has a Mets poster in his room featuring the ’80s racing stripe.

Rapper Tobe Nwigwe posted a picture of himself wearing a black Mets jersey to his Facebook page in October 2019.

In the 2020 documentary Miss Americana, Taylor Swift is spotted with Jack Antonoff in a Mets cap about 42 minutes in.

A framed blue Mets jersey appears in the background when Fred (Seth Rogen) visits the office of his friend Lance (O’Shea Jackson) in the 2019 comedy Long Shot.

In the Netflix series Unorthodox (2020), a character with the unfortunate name Yanky wears what can be best described as a weird Mets cap.

In 2020’s interactive Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt interactive special Kimmy vs. the Reverend, Mikey appears to tell the viewer that a wrong decision was made, and adds, “the Mets don’t suck, you suck!”

In the third episode of the 2020 HBO Max series Love Life, Danny Two Phones (Gus Halper) invites Darby Carter (Anna Kendrick) on a date to Friday night’s Mets game, which is bucket hat night. Darby demurs.

“We heard the heartbeat for our little Mets fan.”

—Chris Fischer, wearing a Mets cap, regarding his wife’s pregnancy, Expecting Amy, Episode 1, HBO Max 2020 documentary series

In the Season 32 premiere of The Simpsons (“Undercover Burns”; September 27, 2020), Mr. Burns assumes an incognito persona by the name of Fred Kranepool.

Here’s an exchange from The Outsider, “Dark Uncle,” Episode 3, January 19, 2020 (HBO); while a Cubs game is on at a bar:

ALEC PELLEY: The first game my Dad ever took me to was at Wrigley. 1985, Cubbies-Mets, must’ve been towards the end of the season somewhere. After all these years, who can remember the date?

HOLLY GIBNEY: Did they win or lose?

ALEC: Cubbies lost.

HOLLY: September 26.

ALEC: September 26. I wish I could remember who was pitching.

HOLLY: Johnny Abrego started for the Cubs, but was knocked out in the fourth. He was relieved by Ron Meridith, Steve Engel and Jay Baller. Dwight Gooden, on the other hand, threw a complete game shutout for the Mets.

You’ve heard of a political football? The Mets are sometimes a political baseball.

• Mr. Met was listed as part of the festivities for the opening of Mike Bloomberg’s Bayside field office, February 6, 2020, when the ex-mayor ever so briefly ran for president. Earlier, while campaigning in Oakland, Bloomberg had made a reference to how being the Mets manager — as opposed to the position he’d filled in New York or the one he seemed to want in Washington — is the hardest job in America.

• On June 20, 2020, celebrity Mets fan John Leguizamo sent out a fundraising email for Long Island Congressional candidate Perry Gershon in which both the endorser and the endorsee wore Mets caps. Gershon was seen often on the campaign trail in an orange cap with a blue NY, matching the motif of his signage and Web site. Alas, the candidate most likely to introduce resolutions praising the “valiance and vitality of the New York Mets” in the House of Representatives lost his primary. But Leguizamo’s garb was not incidental; John also wore a Mets cap during a Zoom panel presented by Variety dedicated to Latinx creatives, released October 15, 2020.

• “I couldn’t be a better pitcher for the New York Mets than Jacob deGrom.”

—Chris Christie on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert February 25, 2020

• Paterson, N.J., mayor André Sayegh appeared on MSNBC’s All In With Chris Hayes on May 21, 2020, to discuss his city’s success with COVID-19 contact tracing, wore a Mets hoodie — blue, with a big orange NY — while addressing the topic.

• On Full Frontal with Samantha Bee, September 30, 2020, one day after the first presidential debate, Bee countered Donald Trump’s charge that Joe Biden wears the biggest mask he’s ever seen, offering Mr. Met and his mask as evidence to the contrary.

More real life than politics: The scheduled guest on Late Night with Seth Meyers when NBC News broke in to announce Trump tested positive for COVID-19 at around 1 AM, October 2, 2020, was David Wright, promoting his upcoming book, The Captain. After the initial report, anchored by Brian Williams, the network rejoined Late Night, with the previously recorded Wright interview already in progress.

As if I have to tell you, the Mets and elections interacting is hardly a recent phenomenon. One excavated-in-2020 example comes from the October 14, 2000, Saturday Night Live presidential debate sketch, moderator Jim Lehrer (Chris Parnell) grew so disengaged by Al Gore and George Bush that he tuned into the Mets-Cardinals playoff game on his monitor (that year’s second debate and Game One took place on the same night, October 11).

Here a few other Mets sightings from the SNL archives, including a couple from very recent times:

In his first appearance as a Saturday Night Live cast member, during host Jack Black’s monologue/musical number on October 4, 2003, Kenan Thompson wears a contemporary Mets road jersey.

“A Manhattan eye surgeon is offering free LASIK Eye Surgery in exchange for a pair of Mets playoff tickets. Here’s some advice: If someone can’t afford baseball tickets, don’t let them operate on your eyes. With lasers.”

—Seth Meyers, Weekend Update, SNL, October 7, 2006 (when Mets swept Dodgers in NLDS); Season 32, Episode 2

“I love the Mets! But every time I suggest a Mets-themed prom, you guys look at me like I’m crazy! Well, here I go — final effort: Let’s do a Mets prom! Blue and orange streamers, hot dogs! My uncle knows Mookie Wilson. He can come! Therefore, my theme is, ‘Remember the Night We Mets?’ Thank you.”

—Fred Armisen (wearing a Mets road jersey and a blue Mets cap) as Billy Zerillo, in a prom committee meeting, Saturday Night Live, May 19, 2007 (Season 32, Episode 20)

On Saturday Night Live, October 6, 2007 (Season 33, Episode 2), Fred Armisen as Omar Minaya and Kenan Thompson as Willie Randolph take to the Weekend Update desk to unsuccessfully explain away the Mets’ late-season collapse (with Thompson in a home Mets uniform and blue cap).

Kenan Thompson wears a blue Tom Seaver throwback batting practice jersey in the “Driving School” sketch on Saturday Night Live, March 8, 2008 (Season 33, Episode 7)

An egg wearing a tiny Mets cap was part of a bumper during the 2019-20 season finale of Saturday Night Live (S. 45, E. 18), May 9, 2020.

On Saturday Night Live, October 31, 2020 (Season 46, Episode 5), in another of the big John Mulaney-led musical sketches celebrating New York’s weirdness, Maya Rudolph appeared as the Statue of Liberty channeling Elaine Stritch by singing, in an updated version of “I’m Still Here”: “Danced for the ’86 Mets and broke my ankle, but I’m still here.”

“I had my first New Year’s Eve kiss with Mr. Met’s daughter. Stacy Met. Sweet girl. Big head.”

—Timothée Chalamet, monologue, hosting Saturday Night Live, Season 46, Episode 8, December 12, 2020

The death of the artist Christo (1935-2020) brings to mind Fred Armisen as Tom Jankeloff visiting The Gates in Central Park on Saturday Night Live, February 19, 2005 (Season 30, Episode 13), while wearing a windbreaker displaying the Mets script logo and the number 31. All that was missing was a blue cap to complement the onslaught of orange fabric.

A couple of other passings in the realm of pop culture and the Mets are worth noting here. Richard Herd (1932-2020) was Matt Wilhelm, George Costanza’s boss with a New York baseball team on Seinfeld. In “The Millennium” (Season 8, Episode 20; May 1, 1997), Mr. Wilhelm departed that organization to take on a new role: head scouting director for the New York Mets — the job George wanted. And Jerry Stiller (1927-2020), when he wasn’t George Costanza’s Festivus-inventing father Frank, played characteristically none too pleased as Arthur Spooner when his son-in-law Doug Heffernan (Kevin James) took him to Shea Stadium on The King of Queens (“Doug Out”; Season 2, Episode 6; October 25, 1999), though he did cheer up when Doug leapt onto the field to attempt to retrieve a foul ball for him. Alas, Doug was thrown in “Mets jail” for his would-be good deed.

Now let’s spend a few moments with Philip Roth’s 1997 novel American Pastoral:

One night in the Summer of 1985, while visiting New York, I went out to see the Mets play the Astros, and while circling the stadium with my friends, looking for the gate to our seats, I saw the Swede, thirty-six years older than when I’d watched him play ball for Upsala. He wore a white shirt, a striped tie, and a charcoal-gray summer suit, and he was still terrifically handsome.

[…]

“You’re Zuckerman?”, he replied, vigorously shaking my hand. “The author?”

[…]

“These are my friends,” I said, sweeping an arm out to introduce the three people with me. “And this man”, I said to them, “is the greatest athlete in the history of Weequahic High. A real artist in three sports. Played first base like Keith Hernandez — thinking. A line drive doubles hitter. Do you know that?” I said to his son. “Your dad was our Hernandez.”

“Hernandez’s a lefty,” he replied.

[…]

The following letter reached me by way of my publisher a couple of weeks before Memorial Day, 1995.

Dear Skip Zuckerman:

I apologize for any inconvenience this letter may cause you. You may not remember our meeting at Shea Stadium. I was with my oldest son (now a first year college student) and you were out with some friends to see the Mets. That was ten years ago, the era of Carter-Gooden-Hernandez, when you could still watch the Mets. You can’t anymore.

[…]

Sincerely,

Seymour “Swede” Levov, WHS 1945

Need a few more reminders that 1986 is eternal?

In the 2020 Long Island-set film Standing Up, Falling Down, Marty, a dermatologist played by Billy Crystal, watches the 1986 World Series, calls the son from whom he is estranged and mentions that Ron Darling is his son’s favorite player.

“What a great-looking crowd — so many stars, so much cocaine. Is the is the Emmys or the Mets’ locker room?”

—David Letterman, 2020 Emmys (9/20/2020), reading jokes ostensibly left in his tuxedo pocket from when he last wore it, hosting the 1986 Emmys

ESPN announced a multipart documentary delving into the 1986 Mets, their city and the times in which they conquered the world will appear in 2021. It is being crafted by Friend of FAFIF Nick Davis and I have a feeling it will be very much worth watching.

Need another reminder of what life was like ten years after 1986?

From Mystery Science Theater 3000, Episode 704 (February 24, 1996), during the opening scene to the The Incredible Melting Man, amid a countdown to launch:

VOICEOVER: T-minus 25 seconds.

CROW T. ROBOT: The Mets lost today.

The Oakland Mets (whose uniforms looked more softball than baseball) lost to the California Stars when Ralph Hinkley homered for the California Stars in Season 2, Episode 1 of The Greatest American Hero, “The Two-Hundred-Mile-an-Hour Fast Ball,” November 4, 1981. No, we’re not sure what a team called the “Mets” was doing playing as “Oakland”. We are, however, certain the Mets were nowhere near a World Series in the late ’70s, but a stock photo of a Mets game at Shea Stadium (wide angle, probably from the ballpark’s early days) appears in a TV Guide ad for the March 20, 1977, premiere of the ABC movie Murder at the World Series, which itself filmed its baseball sequences at the Astrodome, as the World Series in question pit the Astros versus the A’s. Maybe somewhere in here was the seed of the idea that became Major League Baseball’s 2020 postseason bubble.

And maybe, had the Mets provided season tickets to one of the leading songstresses of the late ’70s, they would have been invincible, because “of the fifteen New York Met games she’s attended, the Mets have won all fifteen.” The lady in question was Gloria Gaynor, whose great baseball luck was mentioned by Casey Kasem as he introduced “I Will Survive” as the No. 1 song on American Top 40, March 17, 1979. Casey had been telling a story of how Gaynor’s South American tour crossed paths with that of New York Cosmos, and how her pregame concert may have helped the Cosmos break their winless streak (the Cosmos resented the idea they needed an opening act let alone the kind of luck Gloria claimed to bring her teams). Nine years earlier, in his very first AT40 (July 4, 1970, based on the Billboard chart of July 11, 1970), Casey talked up “Everything Is Beautiful” by Ray Stevens at No. 29 this way: “If success contained calories, this guy would outweigh the New York Mets.”

In those days, the Mets were defending world champions, a fact that didn’t escape the showrunners of That Girl at the time:

“There are a lot of great men. There’s the infield of the Mets…”

—Donald Hollinger, That Girl, “Easy Faller,” Season 4, Episode 25, March 19, 1970

“When I can explain why I can miss an entire inning of a Mets baseball game because I’ve been staring at your picture on my television set […] then I’ll be able to explain why I love you.”

—Donald Hollinger’s note to Ann Marie, That Girl, “All’s Well That Ends,” Season 4, Episode 26, March 26, 1970

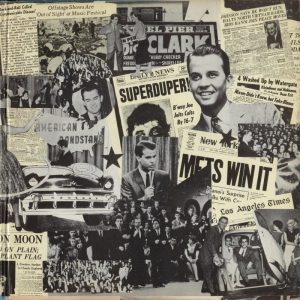

The Dick Clark 20 Years of Rock N’ Roll double album from 1973 included the front page of the Post announcing the Mets’ world championship in 1969 part of its gatefold art, indicative of what a surpassing cultural moment, not just pop cultural, the Mets winning it all was. Though they didn’t make it as tracks in the Clark-curated collection, two songs in the aftermath of the 1969 World Series that celebrated the most unlikely championship ever made themselves known to us a mere 51 years later: the Calypso-flavored “Mets” by the San Joe Trio (which namechecked several of the champs); and the garage-rocker “The Mets Special” by Rodd Keith (sounds a little like Eric Burdon and the Animals).

To understand just how far the Mets came to get where they got as the ’60 ended, here are a couple of instances of how they were portrayed just a few short years earlier:

• The 1963 Off-Broadway revue Put It In Writing included a song, written by Fred Ebb and Norman Martin, that included the following lyrics: “When you run for a ball run right into the stands/Don’t forget, you’re a Met/When a grounder arrives let it slip through your hands/Don’t forget, you’re a Met,” asserting Mets fans preferred their new team lose.

• George Carlin on The Merv Griffin Show in 1965 referred to his character Lyle O. Higley, head of a chapter of the John Birch Society, as “a veteran of two wars, a depression and a Mets doubleheader”.

More recently from the world of big-time talk shows, especially those helmed by Mets fans and/or hosting Mets fans…

• Jerry Seinfeld joined Jimmy Kimmel on May 5, 2020, and compared notes on throwing out first pitches at Citi Field.

• Bill Maher’s suit jacket lining displayed the Mets skyline logo on Real Time, October 23, 2020. Four weeks later, on the eighteenth-season finale of his show (November 20, 2020), Bill’s montage of audiences applauding — a symptom of doing pandemic shows in front of nobody — included a clip from the Polo Grounds of fans behind a LET’S GO METS banner. Maher had been a minority owner under the Wilpons; Steve Cohen had just bought the ballclub when this episode aired.

• And on May 7, 2020, over on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, Pete Alonso appeared in the extended (142-part) version of The Last Dance, ESPN’s Michael Jordan documentary, offering this rumination: “I remember him. He played baseball for the Birmingham Barons. He also played basketball? That makes sense. He was pretty tall?”

He was, Pete, he was.

Archie Bunker may have been a Mets fan from Astoria, but nobody could accuse him of having been a particularly progressive Mets fan. One wonders what he might have made of Kim Ng being named Miami Marlins general manager in 2020 after hearing him express disgust to son-in-law and philosophical foil Michael Stivic that neighbor Irene Lorenzo was about to receive pay equal to his own: “Whaddaya gonna say when a woman is managing the Mets?” (All In The Family, “Archie’s Helping Hand,” Season 5, Episode 6; October 19, 1974).

It’s just a guess, but he probably would have said what he said less than a year later:

“I gotta go down to Kelsey’s and watch the Mets play ball.”

That pressing appointment came up on September 15, 1975 (“Alone At Last,” Season 6, Episode 2), on a night when in real life Mike Vail tied the franchise and league rookie hitting record versus the Expos. In TV Land, “I won on a ballgame,” the betting Bunker reports to wife Edith. “The Mets beat them San Diego Padres.”

Think Archie took in a lot of Broadway? Probably not, but to appeal to the widest possible audience, there was this radio ad copy for the explicitly gay-themed production Torch Song Trilogy that ran on the New York airwaves in 1982:

“…which then leaves the rest of us non-gays who will be immediately threatened and say, ‘Torch Song Trilogy? No way, nah, listen, I’m going out to Shea Stadium to catch the Mets and squash beer cans with my bare fists.’”

Once you’ve squashed beer cans with your bare fists, what’s left to do except tick off a bunch more Mets pop culture sightings to close out the year?

In the series finale of Anthony Bourdain: No Reservations, “Brooklyn,” Season 8, Episode 16, November 5, 2012, there are two Mets sightings: a green Mets cap on a waiter at Pok Pok, a Thai restaurant; and a Mets beer mat in the garage of a collector in Red Hook.

In his 2013 novel Dissident Gardens, set largely in Queens, Mets fan Jonathan Lethem has one of his characters, Lenny Angrush, try to convince Bill Shea to name the Mets the Sunnyside Proletariats.

On Flea Market Flip, Season 8, Episode 11, “Zen and the Art of Flipping” (February 19, 2017), a fella wearing a Mets cap backwards (adorned by upside-down sunglasses, no less) is spotted browsing for bargains.

In the 1988 film Rocket Gibraltar, very young Macaulay Culkin plays Cy Blue Black, a kid who wears a Mets t-shirt and a Mets cap.

In Billy On The Street, Season 2, Episode 4 (January 4, 2013), a bystander named Jonathan is asked to help a contestant answer a question, and Jonathan is wearing a blue Mets t-shirt (Mets script logo on front).

“I’ve watched a Met game from the owner’s box and partied with Gooden and Strawberry afterwards.”

—Matt Bromley (James Van Der Beek), Pose, Season 1, Episode 1, June 3, 2018