The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

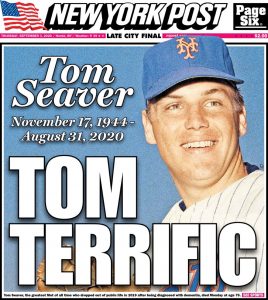

by Greg Prince on 17 November 2020 5:26 am Every November 17, I think, “It’s Tom Seaver’s birthday.” I’m thinking it again. Tom Seaver would have been 76 today. What a heartbreaking sentence to write.

November 17, 1944, was the first baseball birthday I learned. I’m pretty sure I plucked it off the back of one of Tom’s baseball’s cards, presumably his 1971 Topps, since that was the first one of his I ever pulled from a pack. I feel as if I’ve known about November 17, 1944, almost forever. I wasn’t seeking to learn any other player’s birthday. With Seaver, I was always looking to learn more.

Last year, when he reached 75 years old, I had to resist the reflex that I had to resist every time I found cause to write about him since the previous March. I didn’t want to refer to Tom Seaver in the past tense. When his family let it be known in March of 2019 that Tom was withdrawing from public life because of the intensifying effects of dementia, it wasn’t hard for those of us consuming this miserable information from afar to lurch toward a second step, from accepting Tom was altogether out of the spotlight to assuming that made him as good as gone. But nobody said one thing was leading imminently to the other. Tom was missing from our immediate radar for terrible reasons. That was the headline. There was no need for another story.

It was a relief during the summer prior to Tom’s 75th, in late June of 2019, when his daughter Sarah came to town for the dedication of Seaver Way and assured us, in so many words, that Tom was still very much with us, still very much keeping company with Nancy, still very much tending to their vineyard. I wished Tom could have been at Citi Field that weekend joining his 1969 teammates in golden-anniversary celebration of their accomplishments. It seemed all wrong that he wasn’t, but as long as he was somewhere doing something he could enjoy, that seemed all right.

We’d been primed for the worst Seaver news for eighteen months when it came around on September 2, 2020. I was shocked by it anyway. I was lightly scrolling through Twitter, not too many minutes after the postgame show wrapped on SNY, preparing to write up the game of September 2 at some point that night. David Peterson took over in relief of Michael Wacha and pitched four scoreless innings. Michael Conforto went 4-for-5 with 5 RBIs. The Mets beat the Orioles at Camden Yards, 9-4. I don’t remember what exactly I was noodling for a recap, but looking at the box score for the first time since then, I’m reminded that the losing pitcher for Baltimore was John Means, and his name made me think of John Maine, a former Orioles hurler who became a Met staple for several seasons. There was likely a play on words in the offing. We’d been primed for the worst Seaver news for eighteen months when it came around on September 2, 2020. I was shocked by it anyway. I was lightly scrolling through Twitter, not too many minutes after the postgame show wrapped on SNY, preparing to write up the game of September 2 at some point that night. David Peterson took over in relief of Michael Wacha and pitched four scoreless innings. Michael Conforto went 4-for-5 with 5 RBIs. The Mets beat the Orioles at Camden Yards, 9-4. I don’t remember what exactly I was noodling for a recap, but looking at the box score for the first time since then, I’m reminded that the losing pitcher for Baltimore was John Means, and his name made me think of John Maine, a former Orioles hurler who became a Met staple for several seasons. There was likely a play on words in the offing.

Except Twitter had other ideas. I started spotting Seaver’s name in my scrolling. When I saw somebody tweet, “rest in power to the greatest met there ever was,” I didn’t need to get to the end of the lower-case sentiment. I knew where it was going. And I knew where I was going. In a blink, I was in front of my computer to write the Faith and Fear piece I’d known was coming someday but didn’t know was coming that night. Game Seven had arrived in my Mets fan soul. The ball was in my hand.

I had nothing.

Understand that any chance I had to write about Tom Seaver from 2005 forward represented a feast day for me in this space. I’d practically tie a napkin around my neck in anticipation of what was I about to pile on my plate. I get to call attention to the premier career in Mets history. I get to high-five my generational peers as if Tom had just finished another scoreless inning. I get to provide background and context to the later generations who might wonder what all the Franchise fuss is about. I get to feel like I did some summer afternoon in 1975. It was a privilege to write about Tom Seaver in life.

What’s more, I’d been writing in-memoriam tributes for 15 years. Those were remembrances of Mets and Mets figures and others I connected to the Mets that I assigned myself with an utmost sense of purpose and crafted out of veritable holy obligation to the memories of the suddenly departed. I don’t mind telling you that when I wrote those they flowed from my fingers as if they’d been on file waiting to emerge. I wrote nothing in advance. I just knew what to say when the time came. Yet here, with my idol, my hero, my favorite player resting in peace, power or whatever — for minutes that felt like hours — I had nothing to say to my fresh, white, blank Microsoft Word document. Nothing that wasn’t obvious. Nothing that met the moment. Nothing worthy of my subject.

No page ever stared at me so blankly. The situation defied my repertoire. I’d spent 51 years loving Tom Seaver and I couldn’t piece together a proper goodbye. Tom never pitched a Game Seven, but he would have at least thrown a pitch by now. Not having any kind of fastball in me, I typed the word “Terrific” and stared at it. That was my get-me-over curve, I guess. Tom always said the most important pitch was strike one. Eventually, other words followed. They landed on the screen and a finished product landed on the blog before long, but the whole exercise struck me as hollow.

Everything struck me as hollow for the next 24 hours. There were fine stories penned, splendid thoughts uttered, heartfelt montages aired and necessary mourning shared, yet somehow it all felt like nothing. How was the greatest Met there’s ever been transferred so definitively to the past tense? I understood why he was traded when I was 14. I understood why he was left unprotected when I was 21. I understood why he couldn’t be at the reunion when I was 56. I didn’t like any of the reasons, but I understood that things we don’t like happen. I understand life ends, even for somebody so many identify as their idol, their hero, their favorite player. But there was a disconnect between this news and my ability to fully process it when I was 57. I just couldn’t plug in.

On September 3, I watched the Mets play the Yankees on TV from necessarily empty Citi Field under a metaphorically appropriate dark late-afternoon sky. I toggled between thinking it would be wrong for the Mets to not win this game of all games and deciding one thing had absolutely nothing to do with the other. I wouldn’t want the Mets to lose to the Yankees on any occasion, but the literal part of me didn’t see any symbolic relevance to the matchup. Other than in Spring Training, Tom Seaver never pitched against the Yankees for the Mets, certainly not in front of vacant stands. Beat the Yankees. Don’t beat the Yankees. He’s still the Franchise and he’s not coming back either way. (May Dave Mlicki live long and prosper, but if his passing is announced the night before a Subway Series showdown, I think I have my angle.)

While winning one for Tom was a terrific idea in the abstract, I didn’t deeply care, regardless of opponent. The Mets could have been playing the Cubs, and James Qualls III could have been batting cleanup for the visitors, and I don’t know that I would’ve cared deeply. Hollowness reigned.

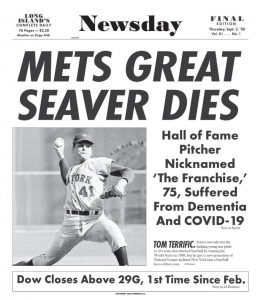

The game went on and on for so long that I couldn’t sit and watch it to conclusion, not if I wanted to take care of three details I decided were essential. I had to go out and buy three newspapers: the News, the Post and Newsday. I stopped buying print editions a long time ago, but these were my lifeline to the Mets as a kid, what sated me between Kiner’s Korner one night and pregame the next. I tracked Tom Seaver putting up his unbelievable numbers in those papers. I read all the good things his teammates and managers and rivals had to say about him. I gleaned when there was trouble mounting between him and the front office. I delivered the June 16, 1977, Newsday that reported he was off to Cincinnati. Talk about bad news on the doorstep.

Not that I hadn’t devoured via social media most everything the News, the Post and Newsday had produced on the subject in the preceding 24 hours. I instinctively needed the physical confirmation that Tom Seaver was no longer with us. That’s what I told myself. I used to save newspapers from momentous events. For the most part over the decades I’ve discarded them in intermittent fits of purging. I’ve kept the front and back pages from every Mets clinching since 1986, but those are celebratory. I don’t know why I had to have these Tom Seaver Died newspapers from September 3, 2020. I just knew I did.

Late afternoon had turned to evening and evening had turned to night. I couldn’t wait for the game to end, lest the papers no longer be on sale. I got in the car, turned on WCBS and made two stops that I thought would bear newsprint fruit. Between a 7-Eleven and a Stop & Shop, I found all three. At Citi, the Mets fell further behind in the eighth, but then caught up in the ninth. There was still some game awaiting me when I returned home.

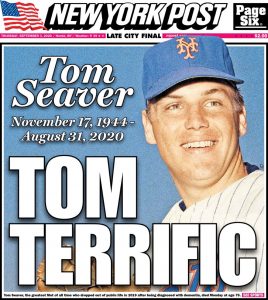

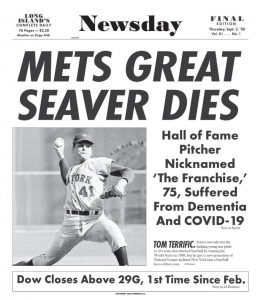

Once inside, I examined the papers I bought. They told their essential story on their respective front pages.

The News: A most ‘Terrific’ life

The Post: TOM TERRIFIC

Newsday: A SCHOOL YEAR LIKE NO OTHER

Check. Check. And what?

I was slapping my forehead in a second. I had seen the Newsday front page online. Not this one. The Seaver one. It was instantly memorable because, by some cosmic coincidence, it was presented in a throwback format. Newsday was commemorating its 80th anniversary that very day by making up its front page to resemble what it published in 1940. Normally I’d admire that kind of homage. On this particular evening, I would have preferred something out of 1970. I was too young to be a Newsday carrier when I was seven, but not too young to read the N.L. Leaders the paper printed most every day. I wanted that version of Newsday in my hands, the one that taught me no starting pitcher was statistically better when he went to the mound every fifth day. Most wins. Most strikeouts. Lowest earned run average. It wasn’t a summer’s day in 1970 without the sports in Newsday reiterating how good Seaver was. But I’d take whatever they’d created in 2020 that had Seaver’s passing on the front page.

I was berating myself over the rookie mistake I’d made when I’d gone out before. I didn’t check to make sure I had the right edition of Newsday. Obviously, because it was late in the day, the late edition must have been sold out (who knew newspapers sell out these days?) and all that was left at the supermarket where I picked this up were the remnants of the stack from early in the day. That had to be it, therefore this would be easily rectified. I’d go out again and get the right one.

Fortunately, the baseball game ended in short order, with Pete Alonso swatting the tenth-inning home run that inevitably had to be hit in Tom’s honor (forget what I said that it didn’t matter whether the Mets won or lost). I’m going out again, I told Stephanie the instant Mets 9 Yankees 7 went in the books. I grabbed an umbrella and a plastic bag and set off on foot in the neighborhood. It was raining too hard by now for my driving comfort and, besides, we have enough stores within walking distance to find a newspaper.

I tromped seven-tenths of a mile in the direction of the train station and the seven-tenths of a mile back as the cats and dogs commenced coming down in buckets. I tried six stores: two chain pharmacies; two chain convenience stores; one deli; one place I want to call a stationery store except I don’t think they sell stationery. Not one of them had the Seaver edition of Newsday. I got wetter and wetter, madder and madder. Why didn’t I go out earlier? Why don’t I get in the car again and try the next town? Why does this matter to me? Am I letting Tom down? Tom is dead. He’s never met me, but now I feel guilty that I’m not making the plays behind him. You didn’t need to be Buddy Harrelson to pick up the right paper. It was a simple ground ball and I let it get by me.

The phrase “hot mess” might apply to how I was coping. But I tell ya what: the hollowness filled in. I felt it now. I felt Tom Seaver’s death. It was real. I connected to it. Going out in search of a newspaper was apparently my true tribute to my favorite player. It was my proper goodbye. No, I didn’t make the play, but I left my feet in pursuit of the ball. It wasn’t going to do either of us any good if I had the late edition of Newsday in my hands or not. In fact, I would learn after doing a little digging, that the METS GREAT SEAVER DIES front page and the coverage that accompanied it only went out to home subscribers. I couldn’t have found it in a store no matter what time I sought it. Maybe if I’d kept my paper route I’d have it.

This was on September 3. It’s November 17 now, the date every year when I think, “it’s Tom Seaver’s birthday.” Tom Seaver would have been 76 today. That sentence remains heartbreaking so soon after September 3. But Tom had 75-plus mostly terrific years. We as fans reveled in the decades’ worth that brought him to our attention and kept him there. We’ll continue to revel in what he did and who he was in and out of a Mets uniform. That’s the headline here.

by Greg Prince on 13 November 2020 10:26 pm Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

I’ve been alive forever

And I wrote the very first song

—Barry Manilow

Jeurys Familia (2012-2018, 2019- ) won’t still be relieving for the Mets in 2029. Jacob deGrom (2014- ) won’t still be starting for the Mets in 2031. Michael Conforto (2015- ) won’t still be driving in runs for the Mets in 2032. Brandon Nimmo (2016- ) won’t still be getting on base by any means necessary for the Mets in 2033. Dom Smith (2017- ) won’t still be pounding out doubles for the Mets in 2034. Jeff McNeil (2018- ) won’t still be pinging from position to position for the Mets in 2035. Pete Alonso (2019- ) won’t still be blasting homers for the Mets in 2036. Andrés Giménez (2020- ) won’t still be making plays in the hole for the Mets in 2037.

And if they are, they won’t be doing whatever they’re still doing for another year besides.

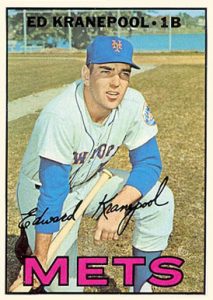

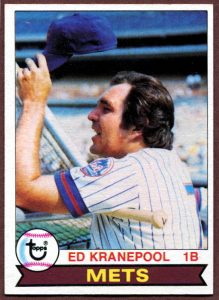

Steadiest Eddie. So let’s salute as unbreakable a Mets record as exists: Ed Kranepool’s 18 seasons as a Met, spanning 1962 to 1979. Nobody else has come close to playing so long for us, let alone playing so long for us and nobody else. It is highly unlikely anybody else will ever play more. Longevity. Continuity. Exclusivity. The combination is not to be underestimated, because the combination crafted by Kranepool has never been equaled.

• Cure David Wright (2004-2016, 2018) of his spinal stenosis and let him play his entire contract, through 2020, without pause. He might make the Hall of Fame, but he comes up a year short of Ed Kranepool as a Met.

• Fix the left elbow of John Franco (1990-2001, 2003-2004) without time away for Tommy John surgery and then keep him around instead of letting him slip off to Houston for his final innings. He comes up two years short of Ed Kranepool as a Met.

• Same for fantasy-version, never-leaves, therefore in theory never-gets-in-trouble so we never have reason to stop loving him Jose Reyes (2003-2011, 2016-2018). Uninterrupted Reyes comes up two years short of Ed Kranepool as a Met.

• What if Buddy Harrelson (1965-1977) never left instead of spending two years with Philly and one in Texas? Still not enough. When Buddy was coaching in 1982 and the Mets were suddenly short of infielders, there was some chatter that the 38-year-old former Gold Glover might have to be activated. Add that hypothetical to the other hypothetical and still nope. Harrelson comes up two years short of Ed Kranepool as a Met.

• Straighter and narrower paths for Darryl Strawberry (1983-1990) and Doc Gooden (1984-1994) that carry them respectively to the ends of their careers (1999 and 2000, respectively) in Flushing? Like Wright, each man still winds up a year short of Ed Kranepool as a Met.

• Maybe if Tom Seaver’s restoration in 1983, intended to eradicate that he was forced to abdicate following his initial 1967-1977 reign, isn’t botched in 1984, and he stays at Shea all the way to 1987, which was when he officially retired…that’s sixteen seasons as a Met and it’s also STILL not enough to measure up to Ed Kranepool as a Met.

And if you’re a New York Met who’s beyond the reach of even Tom Freakin’ Seaver, then, brother, you must be doin’ somethin’ Amazin’.

You can attempt to delete ifs and buts from the story of every Met who isn’t Eddie Kranepool, but they’ve all got ifs and buts. For example, if the Mets never traded Jerry Koosman, he conceivably could have played all nineteen of his seasons with the Mets (and maybe been A Met for All Seasons), but then we don’t get Jesse Orosco and we can’t say for sure who would’ve gotten the second last out of a World Series in Mets history.

No, no buts about Eddie Kranepool. No ifs, either. Ed Kranepool showed up early and stayed as late as he possibly could. He put in 18 seasons; 18 seasons in a row; and 18 seasons in a row as a Met only.

Edward Emil Kranepool in a taxi, honey. Nobody’s had a Met career like Kranepool’s, except Kranepool. Nobody’s been a Met like Kranepool, except Kranepool. Nobody’s been the Mets like Kranepool, except Kranepool. That was the case in 1962, in 1979, in all the seasons in between and, as the four-plus decades since he played have illustrated, forever after. Projections are dangerous to make without the data to back it up, but I feel comfortable declaring nobody else ever will be a Met like Kranepool, except Kranepool.

That’s the beauty. That he’s still Ed Kranepool and there’s still no catching him or matching him let alone the possibility of hatching him, or a reasonable facsimile thereof. There’s exactly one Ed Kranepool. Nobody else has one of him because there is only one of him. Baseball-Reference lists “similarity scores” for every player with decently measurable major league tenure (100 IP; 500 AB), so while you can certainly find statistical comps for Ed Kranepool if so inclined, I don’t believe any other baseball franchise has so deeply embroidered within the fabric of their story any figure quite like him.

Ed Kranepool is of the New York Mets.

The New York Mets are of Ed Kranepool.

He’s ours, dammit.

***Ed Kranepool, we have determined, has the Most Seasons record cold. Most games played, too, with 1,858, topping Wright by more than a full season-and-a-half’s worth. According to Baseball Musings, nobody’s played in more Met losses than Eddie: 1,102, which will come with the territory of anybody whose 18 Met seasons, partial and full, encompassed eight last-place finishes. Krane is second in wins, however, with 746 (with five ties thrown in for middling measure). Befitting a man of his experience, he dots Top Fives and Top Tens all over the Met charts.

He earned his spots in the upper levels of Mets compilation categories by hanging in there. It is no insult to say Ed Kranepool’s best quality as a player was sticking around and sticking around some more. That and arriving in the big leagues sooner than any Met ever had or ever will. The latter is technically unknowable, but give us a shout when you come across another Met not yet old enough to vote.

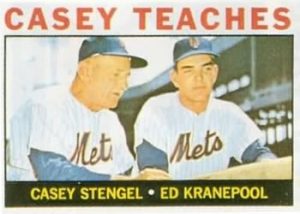

The Youth of America gets some private tutoring. Eddie was only 17, no older than ABBA’s Dancing Queen, when he made his major league debut, which makes sense only when you realize the Mets weren’t yet six months old themselves and how is an infant franchise supposed to know you don’t put a 17-year-old in the big leagues unless it’s World War II or you’re nurturing the next Mel Ott? They signed Ed in late June shortly after his high school graduation and ten days after Marv Throneberry failed to touch two-thirds of the necessary bases to secure what he thought was a triple. So yeah, the baby Mets were in the market for a first baseman of the future practically right away. At James Monroe High School in the Bronx, Ed broke records established generations before by a fella named Hank Greenberg. He was a heavily scouted, hot enough property in those pre-draft days to elicit a bonus of $85,000, a lofty figure for 1962.

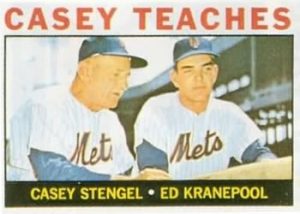

Ed chose the Mets because he deduced advancement on a ballclub in dire need of help would come quickly. Yet the Mets didn’t rush him to the majors right away. No, they waited until September. Then they give him just a taste. The fans, too. They needed something to savor en route to 40-120, something that would tell them the future had some promise in it. Kranepool relieved Gil Hodges on defense on September 22. He got his first base hit a day later in what was supposed to be the final game the Mets would ever play in the Polo Grounds. The following April, Shea Stadium wasn’t ready, so the Mets were back in Manhattan. So was Eddie, though he probably wasn’t ready, either. How could he be? He was only 18. A productive Spring Training had lured Casey Stengel into insisting on Krane’s inclusion on 1963’s Opening Day roster, but the minors beckoned by July.

In 1964, at 19, Eddie was an established big leaguer, though one seemingly final detour to Triple-A at least provided him a story to tell again and again (as if being schooled by Stengel while wet behind the ears wasn’t enough of a conversation piece). After slumping during Shea’s first weeks, he tore up Buffalo, earning a promotion in late May. He played in a doubleheader for the Bisons on a Saturday in Syracuse and schlepped to Queens for a doubleheader the next afternoon. That one, against the Giants, went 32 innings in toto, and Eddie played all of it. Had the May 31 nightcap lasted just a little longer, Krane likes to mention, he would have been playing in another month.

“When are we gonna be ready?” The Mets’ youth movement was planting its seeds during Kranepool’s first years, and it was reasonable to assume he was on the verge of sprouting. In recent times, when prodigy Bryce Harper was breaking in to rave reviews, and later when Juan Soto was doing the same but even more spectacularly, their ascent up the ranks of the all-time teenager home run list was duly noted. You know whose name continued to show up prominently in such historical accountings? Yeah, Ed Kranepool’s. His 12 home runs before the age of 20 slot him eighth among all teens in baseball history. Admittedly, there’s not a ton of competition, given that relatively few players see the majors before their twenties, but among those who did, Eddie showed more power than most of them. Krane is one behind his boyhood idol Mickey Mantle, one ahead of Robin Yount. Mantle and Yount are in the Hall of Fame. (It only seems like Soto already is, too.)

Eddie was at least, after turning twenty the previous November, an All-Star in 1965. The Mets were on their way to losing more than a hundred games for the fourth consecutive season, so this was one of those situations in which there was a Met All-Star because the rules said there had to be, but Eddie was posting very respectable numbers, batting over .300 through mid-June and hitting .287 once he joined the likes of Mays, Aaron and Clemente at Metropolitan Stadium in Bloomington. Ed didn’t play, as the NL won without his contributions, but they certainly didn’t ask him to vacate the premises.

It would be misleading to play the AMFAS Young Player Peaked™ card here, because it’s hard to say a good first half in ’65 and a little pop while still getting proofed if he requested a Rheingold amounted to a peak. There were some good signs for Kranepool, but what Ol’ Case had said in the first part of his famous “in ten years…” line wasn’t quite coming to fruition. You know the bit. Stengel, in what turned out to be his final Spring Training as skipper, was telling reporters about two representatives of his Youth of America. This young feller, he more or less said of Ed Kranepool, is twenty, and in ten years has a chance to be a star. This other young feller, he said of Greg Goossen, is twenty, and in ten years has a chance to be thirty.

The joke is usually on Goossen, and perhaps Stengel, but Kranepool, at twenty, was done being an All-Star. His final 1965 numbers sagged. Once he stopped being a teenager, his home run totals ceased to appear impressive. Once he turned 21, he’d never again play in as many as 150 games in a season. Once he turned 23, he’d never again play in as many as 130 games in a season. It was somewhere around this time that the realization set in that the first amateur the Mets ever signed to much fanfare was never going to set the world on fire as a professional the way scouts thought he might when he was in high school just a few years earlier.

Or as the banner a not particularly satisfied customer brandished not very deep into the young man’s career asked, “IS ED KRANEPOOL OVER THE HILL?”

Ed Kranepool got old before his time, but only in context. When the Mets traded Jim Hickman to the Dodgers following the 1966 season, that left Ed as the only player from 1962 on the club. Those who weren’t particular about specifics would, for the rest of his Met days, refer to him as the last of the Original Mets. It was a misnomer. The Original Mets were the 28 men who broke camp in April. They included Hickman, Hodges and the first/righty Bob Miller. Legend notwithstanding, Marvelous Marv was not an Original Met. Nor were Choo Choo Coleman, the second/lefty Bob Miller or Harry Chiti, who was traded for himself. Eddie was the 45th of 45 men to play as a 1962 Met. In the popular imagination, they’re all lumped together as the lovable losers of legend. Ed played in two defeats and just three games overall that first year. There’d be plenty of losses to which he’d serve as accomplice in ’63 (starting with Opening Day, when Stengel assigned him to right field), but pinning the L of the first year on Kranepool’s forehead isn’t wholly accurate or remotely fair.

But, like with the doubleheader for Buffalo the day before the doubleheader at Shea before May turned to June, it made for a better story to point to Eddie as someone who’d been around forever. Hence, the 1967 yearbook referred to the 22-year-old as “The Dean”. It was funny because it was true. Ed was the only Met who’d been around since at least the end of the beginning. By ’67, with Ron Hunt having departed in the same trade that dispatched Hickman, he was also the only Met left from when Shea was brand, spanking new. Kranepool was only nine days older than Seaver, yet had a five-season and better than a 500-game head start on the good-looking rookie righty who would turn heads like no Met before him. Casey had given way to Wes Westrum. Stengel’s Youth of America had only taken hold in fits and starts. Seaver was the harbinger of the next era. It wasn’t quite in Queens in ’67, but if Seaver was here, it couldn’t be far off.

Kranepool was here, too. He kind of came with the place.

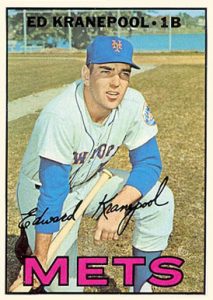

***Growing up, I never thought of Ed Kranepool as a bad player. I never thought of Ed Kranepool as a good player. I just thought Ed Kranepool was a Met. I had never known the Mets without him. Unless you latched onto the Mets when they debuted on April 11, 1962, and then walked away in disgust before June was over (“how could Throneberry miss first AND second?”), nobody had ever experienced the Mets without Ed on their radar if not in their box score. My first exposure to Eddie was on a Topps 1967 baseball card, one of the I don’t know how many dozens that fell into my possession once my sister tired of accumulating them. He’s kneeling in what’s supposed to be an on-deck circle, except it doesn’t appear to be marked as such. He’s just kneeling, somewhere on grass in St. Petersburg. Not that I understood the niceties of baseball card photography when I first got a look at ED KRANEPOOL • 1B or had any conception how long he had been around relative to his teammates or his franchise when I first got my hands on it. I just knew the METS, as the pink-purple lettering identified his employer, were my local team, so I probably wanted to mark this card as special.

This is the version without the beard. At four, maybe five years old, I took a blue Bic pen and drew a beard on Ed Kranepool’s face. I didn’t do that to anybody on any other card from any other team or, come to think of it, any other Met. Maybe I felt an instinctive connection to the Met who’d outlasted all of his previous peers to date. Maybe I was just in the mood to draw a beard on a face. Either way, I can’t recall further evidence of personal affinity for Ed Kranepool. Like I said, he kind of came with the place, simply a fact of Met life, like Shea Stadium, or Kiner’s Korner, or rallies that fell a run short in the ninth.

Gil Hodges must have thought something similar. The kid he said goodbye to in May of 1963 when he retired from playing to take up managing in Washington was still a Met five years later when Gil returned to take the Flushing reins. Lord knows the reins needed him. The Mets had never lost fewer than 95 games, never finished higher than ninth out of ten, and they only reached that height once. By the time Gil came back, Ed “had been around long enough,” Leonard Koppett wrote, “to be seen as disappointing, not the pure promise [he] had been.”

Did Gil Hodges need Ed Kranepool? He didn’t lean on The Dean nearly as much as Stengel and Westrum had, starting him less in 1968 than his predecessors had every year since 1964. It’s no coincidence that Hodges elevated the Mets to a point where they won more often and didn’t fret about losing their lovability. Their standing didn’t exceed ninth, but all contemporary observations agree that this ninth was light years removed from the tenths of yore. The losses (89) continued to outweigh the wins (73), but the chronic ineptitude that took root in ’62 was being professionally removed. Some of that lingering Youth of America was indeed in bloom, but it’s also universally agreed that it was the tending Hodges did that accelerated the growth.

It’s probably a coincidence that the reduction in Kranepool’s playing time occurred in the first season that suggested the Mets were capable of truly getting their act together. Ed’s production tumbled in 1968, even taking into consideration that this was The Year of the Pitcher. Under Hodges, playing time would have to be earned by all Mets, with bonus-baby pedigree serving as no kind of determining factor.

***Ed Kranepool was batting .227 entering play on July 8, 1969, and was mired in a 5-for-53 slump. Nonetheless, Gil Hodges started him and batted him sixth that afternoon against one of the best righthanders in the National League, Ferguson Jenkins. It was, to that moment, the biggest game the Mets were ever scheduled to play in their eight-season existence, really the first big game they’d ever played. The first three months of the season had been a revelation. Instead of falling through the floor, they rose in the standings and, with the halfway mark at hand, they were in second place, seriously challenging the NL East-leading Chicago Cubs for first. The difference between the two teams was five games, unless you counted perceptions. The Cubs were star-laden successors to the Cardinals as smart-money favorites to breeze away with the pennant.

The Mets, no matter that they were well over .500 and actually looking down on multiple teams rather than peering up at everybody, were still the Mets. C’mon, let’s get serious.

That was a challenge the Mets were up for. Their fans, too, 55,096 of whom came to play on a day like no other at Shea. They were stoked to root the Mets over the Cubs as loud as they could. They loved these guys who were blowing by mere respectability and indeed getting serious about first place.

One guy, though, would have to earn it a little more than the others.

At 1:58 PM, according to the tick-tock chronicled in The Year the Mets Lost Last Place, “Jack Lightcap, the Met announcer delivers the starting lineups over the public address system. The crowd greets every Met name with wild cheers, every name except that of the starting first baseman, Ed Kranepool.”

Ed was the Met around whom the Mets as a whole had been chronologically built. His growing pains ensued in full view of those who loved their team but hated that they were so terribly lousy. The sour residue of those years had centered itself on one of 25 Mets in a year when every Met name should have been greeted with wild cheers. “Kranepool,” Dick Schaap and Paul Zimmerman posited, “was young only in chronology, not in manner. He ran like an eighty-year-old man catching a commuter train. His modest ability to hit became even more modest with men on base.”

Krane’s start in ’69 had been good for a while, though this, too, was to form, according to the authors. “[E]very now and then,” they wrote, “Kranepool showed flashes of the brilliance that had been expected of him. For a few weeks, usually at the start of the season, he would hit over .300, and Met fans, starved for a hero, would rally to him. But then Kranepool would start slipping toward his own level […] and the fans would abandon him.” On June 15, with Eddie’s latest seemingly inevitable slump beginning to gather downhill steam, GM Johnny Murphy traded for another first baseman, veteran Donn Clendenon. Clendenon, a righty, settled into a platoon with Kranepool, a lefty. In the week prior to the Cub series, Donn had driven in eleven runs. Donn was linked only to these good new days. Ed went back to what he himself referred to as “a seven-year losing streak”.

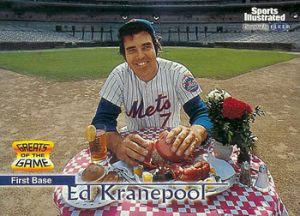

Prepare to dine like a champ. No wonder, then, that if Mets fans had to not respond positively to any Met, perhaps as an exercise in figuratively pinching themselves that everything couldn’t possibly going so well, they had their object of derision all picked out. Eight Mets in July 8’s starting lineup are celebrated as soon as Lightcap announces them. “Kranepool’s name,” Schaap and Zimmerman noted, “inspires a chorus of boos.”

But that was before the game, before the fifth, when, with no runs on the board, Kranepool swung and sent a Jenkins slider over the right field wall. Nobody was booing now. And by the ninth, when the Mets were rallying from a 3-1 deficit, there was no time for ancient recriminations. Everything is happening in the now. Ken Boswell leads off with a fly ball Cubs center fielder Don Young can’t find. It lands as a double. With one out, Clendenon comes off the bench to pinch-hit, the beauty of having two capable first basemen on the roster. He hits one very deep to left-center. Young tracks it down but can’t hold it. It’s another double, though because it took its time not being caught, Boswell has to advance with caution, and he runs only to third.

That’s OK, because Cleon Jones, way up in the batting race, hits one to deep left to score both Ken and Donn. Cleon, a .352 hitter, lands at second. It’s the Mets’ third double of the inning. It’s 1969, and in 1969, managers like Leo Durocher stick with aces like Ferguson Jenkins. Durocher instructs Jenkins to intentionally walk Art Shamsky. The strategy works provisionally as Wayne Garrett grounds to second, leaving runners on second and third for the next batter.

The next batter is Ed Kranepool. Durocher can have him walked, too, so Jenkins can face J.C. Martin. But, are you kidding? Leo’s not worried about any Ed Kranepool.

Maybe he should’ve been, because Eddie makes contact with a one-and-two pitch and bloops it into left field. It falls in for a single. Jones dashes home. The Mets have won, 4-3. The Mets have picked up ground on the Cubs. The Mets are serious contenders. The fans are jubilant, and Eddie has made them so. Ed Kranepool is now batting .232, and he’s going to wind up 1969 batting only .238, but he’s quite clearly having the best season of his life. “I used to get so tired of losing,” he said. “It made the days so long and the nights so unpleasant.”

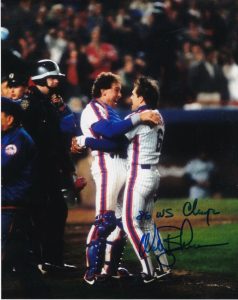

These were better days. The best two, from a Krane’s perspective, came on October 14, when the Met who’d seen it all since 1962 hit a home run in the World Series, and October 16, when the team he’d played for since 1962 won the World Series. Clendenon, Series MVP, and Kranepool combined for four dingers in the five games.

***For the rest of Ed Kranepool’s life, he was a 1969 Met, with a 1969 World Series ring, hard-earned and hard-won. In every public reunion of the world champs, Ed would be as front and center as any of them. The “…since 1962” part was trivia now. The trials and tribulations of a bonus baby who didn’t live up to the hype, who was labeled intermittently as “bitter” or “lazy” was dusty backstory. Eddie beat the Cubs. Eddie beat the Orioles. Eddie, along with his teammates who sung about it on The Ed Sullivan Show, had heart.

Ed Kranepool was now a world champion — a 1969 World Champion New York Met. Nobody could take that away from him. The journey from the basement to the penthouse was complete. With the possible exception of Ed Charles, whose professional baseball career commenced in 1952; was stymied for a decade by institutional racism; and then got bogged down by colorless losing in Kansas City, nobody in a Mets uniform could have appreciated this new reality more than the Krane.

Except the Glider really could call his journey complete. His career ended with Game Five of the World Series (whether he wanted it to or not was another matter). Charles was 36. Kranepool was 24. Though he’d worked as a stockbroker in the offseason and might have thrived in business had he followed that path, he was a ballplayer first and foremost. He had a lot more ball to play.

After 1969, it couldn’t help but be kind of a downer to have to live up to what he’d just been a part of. It showed, not only in his performance but his demeanor. For all the youth he’d embodied, Ed never evinced a sense of ebullience. Maybe he didn’t feel a reason to. He never knew his father, who’d been killed in World War II. He’d been pushed to compete in the top tier of baseball before he was ready. The fans were preternaturally impatient. The reporters always had questions (and occasionally had digs). The manager expected improvement, championship ring or not.

For a spell in 1970, Ed Kranepool went to a place he’d rightfully assumed he was done with, save for annual exhibitions. He was sent to the minors. The erstwhile All-Star, the man who belted a home run in the previous October’s World Series, was batting .118. He was also 25. Not old. Not baseball old, even. It wouldn’t have seemed all that strange if all you knew was age and average and didn’t know the name and what he’d done last summer and fall.

But this was Ed Kranepool, who’d been a Met since 1962 and hadn’t been a minor leaguer since 1964. It was a shock to the system, both that of Mets fans and The Dean. Ed went to Tidewater, hit .310 and returned. The Mets hadn’t thrived in his absence, failing to defend their championship, but Ed was better in the long haul for his visit to Triple-A. Starting in 1971, Ed wasn’t just a young veteran ballplayer, but a reliable young veteran ballplayer. The average soared to .280. The OPS+, for the first time in his career, rose above 100, indicating he was more than a replacement-level player. Not that anybody had that stat handy in ’71, but he’d transitioned to the latter half of his career in style. Gil Hodges’s expectations were being met.

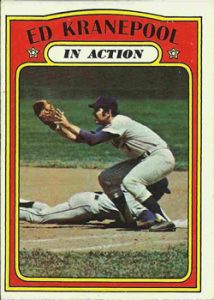

Ed’s speed demanded In Action cards portray him standing his ground. Alas, Gil would be gone before Opening Day 1972, a victim of a fatal heart attack. It was a blow to the entire organization. Nobody likely felt it any more than his fellow first baseman from 1962, the youngster the manager had pushed to mature. “He learned to respect me,” Ed reflected to his SABR biographer Tara Krieger in 2008, “and I learned to respect him.”

The Mets’ next manager, Yogi Berra, who also had played briefly with Kranepool, was a mellower figure. He inherited a club whose offense was bolstered heading into ’72, with trades for Jim Fregosi and Rusty Staub. One of those swaps worked out better than the others — and they were supplemented by another deal for Ed’s former All-Star teammate Willie Mays — but the season, like the two seasons preceding it, were no better than 83-win wonders. They were good enough for third place, which after 1969 wasn’t very good at all.

Then came 1973, and a division captured on 82 wins (maybe that had been the problem from ’70 through ’72 — the Mets were winning one game too many). Eddie was a decidedly part-time player as he reached his late twenties. Clendenon had moved on, but John Milner’s power eventually made him the first baseman more days than not. With the Hammer supplanting the Krane, Ed took more reps in the outfield than he had at any time in a decade. It paid off in the fifth and final game of the NLCS. Staub was out with a sore shoulder, so Berra had to improvise. Eddie started in left, with Cleon in right. Kranepool drove in the Mets’ first two runs in the first, then took a seat so Mays could pinch-hit and drive in another in the fifth. Four innings after that, the Mets had their and Eddie’s second pennant.

***The Mets didn’t win the World Series in 1973, and Ed Kranepool never got close to another postseason once Oakland beat New York in seven games. His legacy, however, was about to be embellished. For Mets fans coming of rooting age in the middle and late ’70s, stories of Kranepool’s shortcomings sounded as if they’d been excavated from the ruins of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It may have happened, but we didn’t really understand. Eddie Kranepool, to us, wasn’t a bonus baby who never delivered on his promise. He was ED-DEE Kranepool who delivered big-time when called upon, two syllables at a time.

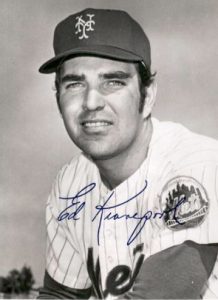

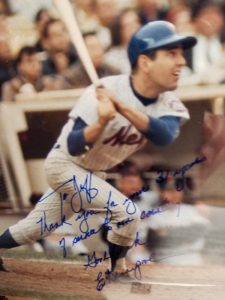

A Mets fan’s view of Ed Kranepool really depended on when one tuned into his long-running show. Getting hooked on the Mets by 1974 got you the Eddie you couldn’t fathom was once considered unpopular. To those of us who were too young to have grasped the 1960s in real time, this Eddie Kranepool, who arose in the wake of his roommate Tug McGraw’s cry of YOU GOTTA BELIEVE, even overshadows the Eddie Kranepool who shows off his 1969 World Series ring. In the 1960s, I was drawing beards on his baseball card. In the 1970s, I was wrapping rubber bands around my Ed Kranepools and storing them safely in a shoe box. I even had him on my closet door — not a card, but an autographed photo. Ed had come to my sixth-grade class one day when I was absent to hand them out. I don’t know how I always managed to be absent for the cool shit, but I was. The story I was told the next day was our teacher was friends with him, so why wouldn’t Ed Kranepool visit Lindell School without notice? Miss Goldstein was kind enough to put aside a picture for me, writing “Greg” on the border. It was almost like it was personalized.

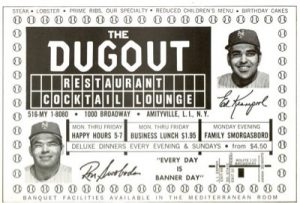

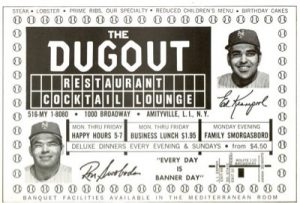

How was I absent for this? While this was an out-of-the-ordinary occurrence, somehow I wasn’t that surprised that Ed Kranepool would visit a random classroom on a random weekday sans warning. Ed and Ron Swoboda had run a restaurant on Long Island. He lived here year-round. Getting the opportunity to meet Ed Kranepool (unless you were dumb enough be out with a cold or something) seemed to come with the territory, like what Wayne Campbell said on Wayne’s World about Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours. A copy of the album was issued to every kid in the suburbs.

Eddie, I’m sure, got a nice hand from a roomful of kids. How nice, I couldn’t say. He was beloved without exactly being lovable, though one must concede love is a matter of taste. Drop by Kranepool’s Ultimate Mets Database fan memories page and you’ll be overwhelmed by how many of the Metsian persuasion pledge eternal allegiance to Eddie — and be more than a little taken aback by those who would be fine if a sinkhole opened up and swallowed him.

Ah, Mets fans.

Generally, familiarity bred affection. Getting really good at something didn’t hurt, either. Ed Kranepool’s 18 seasons yielded 4.3 wins above replacement, per Baseball-Reference. That’s negligible, marginal, insignificant if you didn’t put the number to the name. But the name was Ed Kranepool, and had we known about WAR then, we wouldn’t have cared, because there was one thing Ed Kranepool was, in fact, really good at. Besides sticking around, I mean.

Ed Kranepool became the world’s greatest pinch-hitter this side of Manny Mota. From 1974 to 1977, he batted .447 (42-for-94) in the role that suited him to a tee. In his first pinch-hitting appearance of 1978, he homered off Stan Bahnsen of the Expos to win the game, the first and only walkoff home run of his career. Sometimes he was so good at pinch-hitting, his managers got carried away and pushed him off the bench and into the starting lineup. It was the bench’s loss. For a couple of years, he was pretty close to a regular again and better than ever at it. In his early thirties, he was an approximation of what he was supposed to have been all along. In 1976, he pinch-hit only ten times because Joe Frazier started him more than 100 games, the most votes of confidence Ed had received since Hodges began to fully “respect” him in 1971. In 1975, Ed hit .323 after making Metsopotamia rub its eyes in disbelief by lifting his average above .400 in early June. There was talk of a write-in campaign to make him an All-Star for a second time (it didn’t get anywhere). Poet Bob McKenty was so inspired by the Krane’s surge that he channeled his amazement in verse for the Times:

Although his bat knows no fatigue,

Eddie Kranepool is unique:

The only man in either league

To bat .400 twice a week.

Throughout this second or third phase of his renaissance, Ed Kranepool wore an expression of a man just getting comfortable with being accepted for who he is. The residual gawkiness of the teen and preternatural grumpiness of the dismissed was still in evidence, but this was the Krane. The bird with whom he was homophonically linked is described as large, long-legged and an opportunistic feeder. Some are said to not migrate at all and keep to themselves.

The Krane was indeed a rare bird, native to the meadows of Flushing. Sounds about right. As Leonard Koppett reflected as the flight of the Krane entered what turned out to be its loftiest elevation in 1974, “He didn’t appreciate being the butt of all those jokes in the early days, felt that he hadn’t been given as many opportunities to play regularly as he had earned. He didn’t hold grudges, and he appreciated his responsibilities in a public relations sense, but he was not what one would call a warm personality.”

Nevertheless, Ed Kranepool is who we got as Mets fans, and who we as Mets fans got, even if Ed Kranepool didn’t always seemed thrilled to be Ed Kranepool. He’d smile for the camera if the situation demanded it, but otherwise seemed a little shall we say circumspect about the whole thing — Joe Pesci’s description of the white-haired gent in his mother’s painting in Goodfellas comes to mind: “And this guy’s saying, ‘whaddaya want from me?’”

It’s worth remembering that when a pennant wasn’t being chased, Eddie was essentially just another guy going to work in the same job he had for a long time back when most ballplayers weren’t compensated lavishly and weren’t above replacement. He often seemed unhappy with his situation, maybe with his co-workers, surely with his employers. You stay in the same job for 18 years and not sound surly now and then. Except nobody with a notepad or microphone is likely to ask you what you’re thinking at the end of a bad day or unsatisfying year.

Yet he seemed to smile for the cameras a little more as the years went by. He starred in his very own Gillette Foamy commercial, implicitly attributing the upturn in his fortunes since 1971 not to extra swings in the cage but the shaving cream he was enthusiastically apportioning across his face. When Newsday carriers were encouraged, in the summer of 1977, to convince more of their neighbors to sign up as subscribers, the bait the paper offered us to hustle and sell was a ticket to see the Mets one night real soon, specifically “Mets stars Henderson and Kranepool”. Henderson was the new kid, Steve, from Cincinnati. We all knew Kranepool. We might not have thought of him as a star, but with Seaver and Kingman traded, and Koosman and Matlack struggling, we got it.

I never did sign up any new subscribers (other than my parents), but I would have taken a ticket to Newsday Night at Shea Stadium to see Ed Kranepool. Starting, pinch-hitting, shaving…didn’t matter. ED-DEE could do it all.

***On December 8, 1978, the Mets traded Jerry Koosman to Minnesota for minor league pitcher Greg Field and a player to be named later, leaving only one 1969 Met to be a 1979 Met. Ed Kranepool got to Shea before every one of his world champion teammates and he outlasted them, too. The Dean had extended his tenure to a record-breaking 18th season. He was The Fantasticks, running Off-Broadway since the early ’60s, with no closing date in sight. His peers had been Throneberry and Coleman and the two Bob Millers at the beginning, then the men who made a couple of miracles. Now he was part of a unit whose headliners were named Mazzilli, Stearns, Swan and the darling of the Newsday carrier set, Henderson. Every Met who’d been on an active roster from late September 1962 to late September 1979 had something in common: they had all been Ed Kranepool’s workplace proximity acquaintances. There were close to 300 men who qualified, almost everybody who’d ever been a Met.

That didn’t include Harry Chiti. He’d been traded for himself before Ed got called up.

One of the best ever in a pinch. The late-career magic Kranepool’s bat packed began to wear off in ’78, by which time the long days and unpleasant nights of losing were again entrenched at Shea. The newest iteration of the Youth of America was given the bulk of the playing time by Joe Torre. First baseman Willie Montañez was an RBI machine, so starting the Krane to to keep him sharp became impractical. Ed’s pinch-hitting could still be lethal (15-for-50) but his rare opportunities in the lineup went for naught (2-for-30). Keeping a 33-year-old part-timer fresh was hardly Torre’s priority. When Ed came up in 1962, there was nobody as young as Kranepool. When he headed into 1979, there was nobody in the clubhouse who could possibly relate to all of his baseball life experiences. The 18-year-veteran appeared to be, in the immortal customer-service advice of Rodney Dangerfield, all alone here.

Except on July 14, the highlight of the 63-99 1979 season in a campaign almost entirely devoid of them. It was Old Timers Day at Shea Stadium. The festivities centered on the tenth anniversary of the 1969 Mets. The bulk of them were retired from baseball already. The handful who weren’t were playing for other teams. Seaver was a Red, Koosman a Twin, Nolan Ryan still an Angel long after the Fregosi trade proved less than optimal. Most of those who no longer had a ballgame to play every Saturday showed up at Shea.

One 1969 Met didn’t have to make a special trip. For one afternoon, during pregame ceremonies, Ed Kranepool didn’t have to be a 1979 Met. He could line up with the Mets with whom he identified most closely. He could even break out into a grin when joined in the introductions by perhaps the most famous ’69er of the moment, Chico Escuela, a.k.a. Garrett Morris. Morris had broken through with his “baseball been berry, berry good to me” catchphrase on Saturday Night Live months before. It was uncommonly hip of the 1979 Mets to invite him to reprise his role — that of a 1969 Mets utility infielder — among the authentic alumni. Ed had already gone along with the joke enough to appear in a filmed bit on Weekend Update in which Kranepool had to express dismay with Chico’s new tell-all book, Bad Stuff ’Bout the Mets. Ed was a natural at expressing dismay.

Tom Seaver: “Always take up two parking places.”

Yogi Berra: “Berry, berry bad card player.”

Ed Kranepool: “Borrow Chico’s soap and never give it back.”

Ed stayed in character and shook his head that Chico was stabbing the guys in the back with his revelations. What the hell, it wasn’t like the 1979 Mets were doing any kind of a 1969 impression.

***When the old champs scattered to their post-baseball lives and Ed Kranepool was left to continue in his long-running role, it had to be acknowledged that Eddie hadn’t only been the last of the Met-hicans from 1969 to stay at Shea, he was having a pretty damn long major league career. Those guys who tipped their mesh caps as old-timers in July (the Mets were so cheap in those days) were more or less the same age as Ed. Yet most of them were done. Ed got better at baseball as he went along. True, he was in the denouement phase of his ED-DEE peak by 1979, destined to bat only .232 in his final season, but you didn’t see Jones or Agee or Swoboda or Shamsky still being asked to pinch-hit at a ballpark near you. We’ll say it again: Eddie knew how to stick around.

Except for one night in August when, against the Astros, he left the field before the game was over. To be fair, he thought the game was over. See, the Mets were leading the Astros, 5-0, and starter Pete Falcone had induced Jeffrey Leonard to fly to center with two out in the ninth, so that seemed to end it. Except Frank Taveras had called time at short, which meant Leonard got to swing again, and he used it to single…except this time it was noticed the Mets didn’t have their full complement of nine at their positions because Kranepool, figuring the game was already in the books, had vamoosed to the clubhouse, and…well, let’s just say you don’t come up with the 1962 Mets without somewhere in your soul still being a 1962 Met. The bottom line was an Astro protest was upheld and they had to finish the game the next afternoon (no harm done, except to Falcone’s complete game).

In 1979, an 18-year feast of base hits and dependability was about to end. It would be too much to read into one confusing episode and infer Eddie was trying to tell us, “Hello, I must be going.” Nevertheless, on September 30, 1979, anybody who was watching or listening to the Mets and Cards from St. Louis was about to witness something that seemed unimaginable across the history of the Metropolitan Baseball Club of New York.

It was Ed Kranepool’s last game. Torre sent him up to pinch-hit for John Pacella in the seventh. Eddie produced a double, his 1,418th base hit, which remained the Met standard until David Wright passed him in 2012, and his 90th career pinch-hit, still a franchise record (and 31st all-time in the major leagues). The manager just as quickly removed him for pinch-runner Gil Flores.

That was it. The Ed Kranepool Era was over.

Well, the part where he played for the Mets, that is. When you’re talking Mets, I don’t think the Ed Kranepool Era ever ends.

***Ed Kranepool’s three-year contract expired after the 1979 season. Management was not interested in negotiating a new one. Maybe Ed could have shopped his services to the American League, where the designated hitter was embraced rather than scorned. A man over 35 could get regular swings over there without having to worry about playing the sport the way it’s designed. But the Krane was definitely not a migratory bird. He’d lived all his life in New York, whether it was the Bronx or on Long Island. Free agency opportunities notwithstanding, he wasn’t about to take flight.

Kranepool knew, as everybody did, that the Mets were going to be sold. They were scraping bottom in the standings and drawing ants (flies couldn’t be bothered), but they were still, on paper, a National League jewel in the largest market baseball had. Maybe a new GM would be interested in Kranepool. Better yet, maybe Kranepool could be in on hiring the new GM. Eddie, whose business acumen was a bigger part of skill set than foot speed, tried to put a group together. He was serious. It made the papers. But, ultimately, the group led by Nelson Doubleday and Fred Wilpon bought the Mets. Ed Kranepool didn’t. In 1980, for the first time since there’d been Mets, a Mets season would proceed without Ed Kranepool in uniform.

When the 2020 season was on hold and I had no new games to watch, I checked YouTube to see if anybody had uploaded episodes of my favorite TV drama from when Ed Kranepool was winding down as a player. To my delight, somebody had. The entire series of Lou Grant, which initially ran from 1977 to 1982, was available for my viewing, and I viewed the hell out of it, all 120 episodes. I mention this because a recurring baseball player character was introduced as a love interest for reporter Billie Newman during Season Three, a backup catcher named Ted McCovey, no relation to Willie. Ted isn’t old for a regular person, but he’s not a regular person. He’s a ballplayer and he’s just been placed on irrevocable waivers. Ted tries to explain to Billie what this all means:

You know what baseball’s done for me? Treated me like a kid for the past fourteen years, and now, suddenly, they’re telling me I’m an old man.

I don’t get the sense that’s something Ed Kranepool would have said when the Mets told him his services were no longer required, but I have to imagine he thought some unscripted unsentimental version of it. Ed was their golden boy. He grew up with them. He’d literally spent half his life answering to chants of ED-DEE, maybe tuning out the less flattering remarks that came with it. When Ed Kranepool played his last game, he was fewer than six weeks shy of 35. Not old for a regular person. Not close to old. Not even the oldest Met of his final season (Jose Cardenal was almost 36).

But too old to play for the Mets anymore, which must have been very strange.

***About as great an Internet find as Lou Grant for me was a reprint of a magazine article from the defunct New York Sports, which lives on in pixels thanks to our friends at Metsmerized Online. It’s an article from 1984, breathed back to life by MMO in 2012, written by Len Albin. It’s called “ Ed Kranepool Never Got a Day”. At the time, Ed was feeling underappreciated by Mets management not so many years after he hung up his spikes. His 1,858 games, his 1,418 hits, his 18 seasons cut little ice with an ownership more concerned with trying to make people forget the recent past than celebrating more distant glories. These Mets were just getting good at being in the present. It might have been too much to demand their executives pay proper homage to the past.

Yeah, but this was Ed Kranepool, No. 7 from 1965 forward (and No. 21 for a couple of years before that). This was Ed Kranepool when David Wright was a toddler, Eddie’s records not close to being threatened. They hadn’t given him anything approaching what he — or anybody who’d been a Mets fan more than five minutes — considered his due. No ceremony, no acknowledgement, no nothin’.

“I don’t feel an allegiance to the Mets anymore,” Kranepool told Albin, even as he dressed up in his c. 1978 uniform top and posed Lou Gehrig-style in an empty Shea, addressing the fans who weren’t there for the day he had yet to get. “Loyalty went out the window the day they didn’t sign me.”

Did Eddie mean it? Probably. And probably not. And were the Mets that blithe toward the man who as much as anybody epitomized who they’d been for almost their first two decades? Probably. But probably not. The Mets still had enough of a rearview mirror to gather Old Timers annually in the ’80s. Under Frank Cashen, they inaugurated a Hall of Fame in 1981. True, they hid the commemorative busts in the lobby to the Diamond Club where few were bound to bump into them, and they tended to not announce the ceremonies with sufficient advance notice to draw a large crowd, but they were, in their own less than fantastic way, trying to remember the kinds of Septembers like 1969 and 1973…even a little 1962 sometimes, if not any 1979.

On September 1, 1990, before the Mets took on the Giants in front of more than 40,000 fans, Ed Kranepool got his day. He became the fifth player inducted into the Mets Hall of Fame, the fourteenth member overall. Now he was a world champion, a two-time pennant-winner and recognized by the only organization with which he’d ever been associated as immortal.

The Ed Kranepool story was, at last, complete.

***Only kidding. The Ed Kranepool story was not complete. How could it be? His era is eternal, and the people who owned the Mets were who they were.

In the winter of 2017-18, despite Eddie’s many trips back to Shea Stadium and Citi Field for commemorative occasions, we learned Kranepool was sore at Jeff Wilpon. (Why should he have been any different from the rest of us?) An article, which ran in the New York Times, described Eddie on the outs with the entity that coronated him as a Hall of Famer. Not only that, but Eddie needed a kidney. He was selling much of his baseball memorabilia, not because he needed to, he said, but because it was time.

Amends were made in the summer of 2018, with the then-COO of the Mets reaching out and bringing back Eddie for a first pitch. Of greater import, the Krane got word in the spring of 2019 that a kidney donor with a match for his needs had been found. He was in greatly improved health and spirits by late June, when the 50th anniversary of the 1969 Mets was being toasted by a full house at Citi Field. Tom Seaver couldn’t be there because dementia had sidelined him from public appearances. Too many teammates were no longer with us, but whoever could be there came. Still, without Tom, somebody would have to speak for the group after they were all introduced. That was Seaver’s role at the 40th anniversary. It was always Seaver’s role.

Who better to speak for the 1969 Mets? At the 50th, it was Kranepool’s. Of course it was. Steadiest Eddie was always around. That was worth more than WAR. The most memorable snippet of his brief speech was an admonition to the 2019 team to not give up despite being buried in the standings. “They can do it like we did,” he said to great cheers. The modern Mets eventually listened and inserted themselves into a playoff race you would have thought they’d have needed to pay admission to see.

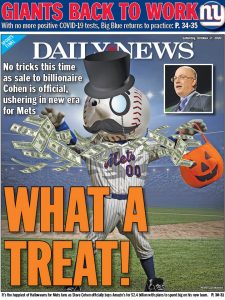

I’d pay admission to attend a reunion of 1979 Mets. Or 1966 Mets. Or any Mets. With Steve Cohen taking over, anything is possible. That Ed Kranepool would be eligible to speak at eighteen of them would make the proposition only more attractive. Nobody ever earned the title A Met for ALL Seasons as much as he did from 1962 through 1979. Before 1980, you couldn’t imagine a season without Kranepool. The slice of 1970 he’d spent at Tidewater was surreal enough.

In Spring Training of ’79, prior to his 18th season, the player to be named later from the Jerry Koosman deal, a minor league reliever named Jesse Orosco, impressed enough to make the ballclub. Or maybe Orosco was chosen a couple of weeks shy of his 22nd birthday because the Mets could pay him the minimum (they’d cut Nelson Briles in camp so they wouldn’t have to pay him a veteran’s salary despite Briles taking part in the Chico Escuela bit). As every baseball fan knows, Jesse Orosco would do so much sticking around in the major leagues that the Mets would be able to trade for him a second time, a dozen years after trading him away, more than twenty years after trading for him the first time, fourteen days before the turn of the next millennium. The Mets wouldn’t hold onto him when they did — they’d trade Orosco for Joe McEwing in Spring Training of 2000 — but that’s some serious sticking around. Jesse was still pitching in 2003, when Jose Reyes was a rookie. You’d figure Kranepool would feel a bond for Orosco based on longevity alone.

Of course the Koosman-Orosco connection is a staple of all Mets historical discussion. The happy kind, anyway. Two pitchers have been on the mound for the last out certifying the Mets world champions, and they were traded for each other: Koosman from 1969 for Orosco from 1986. Not that we knew the back half of that equation in 1979. Yet in 2012, at the Hofstra Mets 50th anniversary conference, I heard Ed Kranepool, in the midst of excoriating the Mets for too swiftly disassembling the 1969 club, rail against the Jerry Koosman trade, even dismissing the Orosco portion of the transaction and the eventual great news that came from it when a friend of mine brought it up to him.

“I don’t care about any Jerry Orosco,” Kranepool fumed.

I’m sure he knew the pitcher’s name was Jesse, but as they said in Animal House, forget it, he’s rolling. And besides, he’s Ed Kranepool. He was being loyal to Jerry Koosman; to 1969; to the Mets he knew best, the Mets with whom he most closely identified, the Mets for whom he’d stand and speak in 2019. Koosman for Orosco turned out to be not a stone steal for the Mets the way we wish all our trades to be (Kooz pitched seven seasons after leaving the Mets and won twenty games as a 37-year-old as soon as he did), but you can’t say it wasn’t a plus trade for the Mets. Orosco grew into an All-Star closer. It was not incidental that he was on the mound for that second world championship. And he did pitch several seasons into the next century.

And we tip our cap right back to ya, Ed. Yet at that moment in 2012, when Eddie was hopping mad all over again that the Mets had traded away his last friend from 1969, leaving him to carry the banner into miserable 1979 all by himself, a fan who’d predated 1986 could feel himself empathizing with the Krane. Yeah, how could they do that to you, Eddie?

Eight years later, that same fan would saddle Kranepool with carrying the 1979 banner, but forget it, I’m rolling.

Ed Kranepool became a Met in 1962. Seventeen years later, he was still a Met. It was miserable 1979. I became a Mets fan in 1969. Seventeen years later, I was still a Mets fan. It was glorious 1986. Meaning? I dunno. Stick at something long enough and you’ll be punished or rewarded, perhaps. But it doesn’t matter that in my eighteenth year of Mets fandom, I received the gaudiest, most overpowering and dominant season of Mets baseball ever, and that in Ed’s eighteenth year of playing for the Mets, he was part of the most depressing, least encouraging season of Mets baseball ever. It wasn’t like either one of us was going to do or be something different.

I’m certain I’m more sentimental about it than he is, but we’re both as loyal as can be to our Mets.

THE METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1965: Ron Swoboda

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1967: Al Schmelz

1968: Cleon Jones

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1971: Tom Seaver

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1974: Tug McGraw

1975: Mike Vail

1976: Mike Phillips

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1979: Ed Kranepool

1980: Lee Mazzilli

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

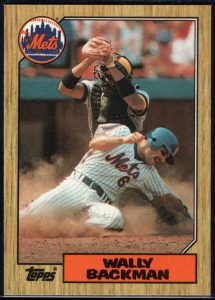

1984: Wally Backman

1985: Dwight Gooden

1986: Keith Hernandez

1987: Lenny Dykstra

1988: Gary Carter

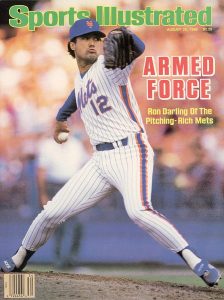

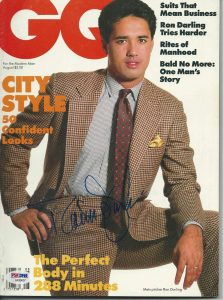

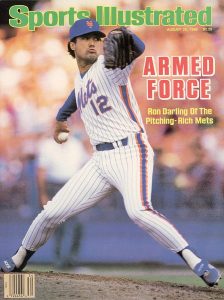

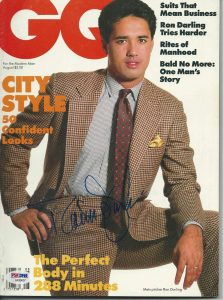

1989: Ron Darling

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1997: Edgardo Alfonzo

1998: Todd Pratt

1999: John Olerud

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

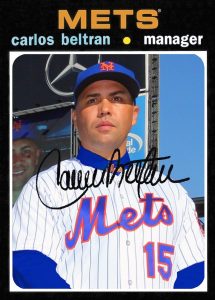

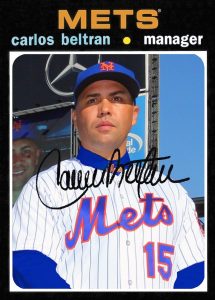

2006: Carlos Beltran

2007: Jose Reyes

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2010: Ike Davis

2011: David Wright

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2015: Michael Conforto

2016: Matt Harvey

2017: Paul Sewald

2018: Noah Syndergaard

2019: Dom Smith

2020: Pete Alonso

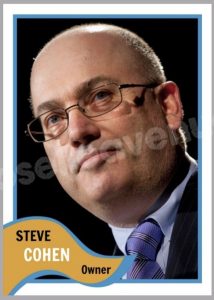

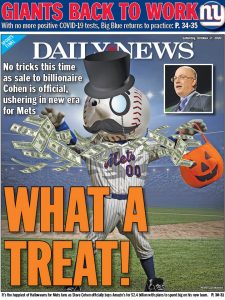

2021: Steve Cohen

by Jason Fry on 10 November 2020 11:48 pm Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

It would be an exaggeration to say that Faith and Fear in Flushing exists because the Mets signed Carlos Beltran in January 2005.

But it wouldn’t be an enormous exaggeration.

In 2005 the Mets already had a reputation for Wilponian meddling and aiming the gun at their own feet, but they hadn’t yet been wrecked by their Madoff misadventure or Major League Baseball’s determination to keep their hamstrung ownership in place. Beltran was a homegrown star who’d outgrown the Royals and logged half a season as a 27-year-old mercenary with the Astros, ending the year by lighting up the 2004 playoffs: a .435 average, 14 RBIs, 21 runs scored, and homers in five straight games.

It was a performance destined to make him very rich, he was the best player on the free-agent market, and the Mets wanted him. Back then, that was enough. The Mets inked Beltran to a seven-year, $119 million deal — not eye-popping now, but a gargantuan sum and commitment then. An exciting new era of Mets baseball was under way, Beltran was going to be its centerpiece, and two lunatic Mets fans decided it was time to turn their daily email kvetching, flights of nostalgic fancy and occasional moments of happiness into something public.

We were a long way from finding our tone, rhythm or anything else — those early posts are just us talking to each other, as we’d been doing over email. But Beltran was on our minds from the start. And in the second-ever Faith and Fear post, Greg offered a prescient warning:

Nevertheless, we will tire of Carlos Beltran. Let me be the first to welcome him to Flushing and show him the door. Not for at least five years, I hope, but it’ll happen. He or his swing will slow down. The strange breezes and thunderous flight path to LaGuardia will get to him. He won’t lead us to the promised land nearly enough and his salary will become unmanageable. He will get booed. Not now, but eventually. It always happens.

What we didn’t imagine was how quickly it would happen. Beltran was hobbled by a quad injury, played through it or was pushed to play through it (you never know, given the Mets) when he probably shouldn’t have, and put up a first season that wasn’t bad — a 2.9 WAR — but wasn’t otherworldly. The fanbase, understandably, wanted otherworldly; a chunk of that fanbase, less understandably, felt entitled to it. Beltran was booed vociferously and complained about endlessly on the airwaves and in the comment sections of the ever-expanding constellation of blogs about the Mets.

Most of those complaints were typical of people who can only see baseball in terms of effort and grit and the will to win and other rah-rah bushwah accepted as intellectual currency by dolts. (Because the universe is malign, these people inevitably sit within two rows of me and are the loudest in their section.) Ironically, Beltran might have won these fans over if he hadn’t been so good in center field — he had an encyclopedic knowledge of positioning and excelled at reading balls off the bat and taking first steps, which let him glide into the gap or back to the fence and corral a lot of drives without lunging or diving, as lesser center fielders needed to do. Fewer showy plays; less balls falling in. That’s the way it’s supposed to work, even if it means you’re not on as many highlight reels. Most of those complaints were typical of people who can only see baseball in terms of effort and grit and the will to win and other rah-rah bushwah accepted as intellectual currency by dolts. (Because the universe is malign, these people inevitably sit within two rows of me and are the loudest in their section.) Ironically, Beltran might have won these fans over if he hadn’t been so good in center field — he had an encyclopedic knowledge of positioning and excelled at reading balls off the bat and taking first steps, which let him glide into the gap or back to the fence and corral a lot of drives without lunging or diving, as lesser center fielders needed to do. Fewer showy plays; less balls falling in. That’s the way it’s supposed to work, even if it means you’re not on as many highlight reels.

One ball Beltran did dive for could have cost him his career — in August 2005, he collided head-to-head with right fielder Mike Cameron in San Diego, one of the most frightening outfield mishaps I’ve seen in more than four decades of watching baseball. Beltran suffered a fractured cheekbone, sustained a concussion that left him unable to remember the next few hours, and contended with bouts of vertigo. He returned to the field six days later and played every game remaining on the schedule. His naysayers would spend the next half-decade deriding him as fragile anyway.

There was also an ugly undertone to that first year. With Omar Minaya at the front-office helm, the Mets were championed (and eventually marketed) as Los Mets, a showcase for Latin superstars such as Beltran, Pedro Martinez and Carlos Delgado. That didn’t sit well with some fans, who saw “Los Mets” not as a way to invite in fans who’d felt little noticed or left out, but as a calculated affront aimed at shoving them aside.

In 2006 Beltran reported for duty healthy, but got off to a slow start, and heard the boos again. That all changed on April 6, one of the more interesting early-season games in franchise history. It was a chippy affair between the Mets and the Nationals, with lead changes and batters taking balls to the ribs. In the seventh, with the Mets up by one, Beltran hit a two-run homer and circled the bases to cheers from the Shea crowd. His face remained impassive, and he plunked himself down on the bench, stone-faced as the fans demanded a curtain call.

It was a peace offering, but Beltran showed zero interest in accepting it. The moment went on, increasingly uncomfortably, until Julio Franco got up from his seat and spoke quietly but pointedly to his teammate. Beltran listened and popped out of the dugout to wave. It was a perfunctory gesture, but the war was over and a magical season (which Beltran represents in A Met for All Seasons) had begun. Beltran tied a club mark with 41 homers, drove in 116, won his first Gold Glove, and put up 8.2 of WAR — an MVP-caliber season. Along the way there were a pair of celebrated walkoffs — a May drive off Philadelphia’s Ryan Madson at 12:33 a.m. in the 16th inning (Gary Cohen exulted that “we’re going home!”) and an August bottom-of-the-ninth homer off St. Louis’s Jason Isringhausen. (Cohen: “HE RIPS IT TO DEEP RIGHT! THAT BALL IS OUTTA HERE! OUTTA HERE! THE METS WIN THE BALLGAME!”)

In the NLCS, Beltran won Game 1 for the Mets with a 430-foot drive off Jeff Weaver and went deep twice in Game 4. He hit .296 for the series … but all anyone remembers is his final at-bat in Game 7. That came with rookie Adam Wainwright on the mound — ironically, he’d stepped in as closer for an injured Isringhausen — and Yadier Molina (then somehow just 24 years old) behind the plate.

It was Cardinals 3, Mets 1, but Wainwright started the bottom of the ninth by giving up back-to-back singles to Jose Valentin and hero-in-waiting Endy Chavez, got Cliff Floyd looking on a curve, then threw Jose Reyes a 1-2 curve — one Reyes lined to center but saw hang up for Jim Edmonds. He then walked Paul Lo Duca, with Anderson Hernandez taking Lo Duca’s place as a pinch-runner. It would come down to Wainwright and Beltran.

As Beltran gathered himself, Molina went to the mound — his third visit of the inning — and told Wainwright to start with a sinker. He then changed his mind and called for a change-up. Wainwright hit the inside corner for strike one, a perfect pitch. Molina called for the curveball inside, another tough pitch that Wainwright executed. Beltran fouled it off for an 0-2 count. Molina decided to double up on the curve, and this time he set up on the outside edge. Wainwright threw what he later said was the best pitch he’d ever thrown for a called strike three, the game and the pennant.

And then this happened. Wainwright would ride that curve to a very successful career, but he’d had trouble harnessing it that inning, throwing two high curves to Valentin and hanging one to Reyes, which unfortunately wound up hit right at Edmonds. He’d gotten the pitch over to strike out Floyd, but the sequence he dropped on Beltran came after an inning in which he’d scuffled and battled. But at the critical moment, with a lot of help from a precocious young catcher showing you why he’d be a Hall of Famer, Wainwright made the pitches he needed to make.