The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 18 September 2020 4:47 pm Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

The golden age of baseball coincides neatly with when one happened to be twelve years old.

—John Thorn, Official Historian, MLB

If first base is childhood and second base is adolescence, the summer you’re twelve years old is your indecisive third base coach putting on and taking off the steal sign so often that you might want to call time. The summer I was twelve years old, 1975, I stayed close to first, but I had my eye on second. No wonder, then, that as summer grew late, I took off for second — and, as summer was turning to fall, ran straight toward the newest of Met stars, Mike Vail.

As Met metaphors go, you had to be there, and I was. I was with the Mets practically every minute of every day in 1975, treasuring the successes of the lingering icons of my childhood while savoring the accomplishments of the unusually large quantity of newcomers who had joined them. Seventeen Mets made their team debuts in ’75, the most in any season since notoriously transient ’67. They were breaths of fresh air, though I don’t mean to imply the extant atmosphere was wholly stale, for I also took comfort that the foundation of 1975 was formed by figures so familiar to me.

It could still be 1969 if you wanted it to be. Tom Seaver pitched as Terrific as ever (22-9; 2.38 ERA; a league-leading 235 strikeouts). Jerry Grote regularly caught the two- going on three-time Cy Young winner. Bud Harrelson was still around, at least when the disabled list didn’t beckon. Wayne Garrett, too, no matter how often they tried to replace him. It could be any year in Mets history when you saw Eddie Kranepool grab a bat and emerge in the on-deck circle. Jerry Koosman notched a couple of saves, once stole second base and pulled down 14 wins. Cleon Jones, who’d been piling up hits for the Mets since 1963, missed time early, but eventually returned. By July of ’75, Jones’s collection of singles, doubles, triples and homers was up to 1,188, the most in Met history.

It could still be 1973, too. Felix Millan played in every game. Rusty Staub drove in runs at a franchise-record pace en route to becoming the first Met burst past a hundred ribbies. Jon Matlack was so good, he wasn’t only an All-Star, he was the Midsummer Classic’s co-MVP, with Bill Madlock, because who could resist the homophonic possibilities? John Milner was on hand, if in a slump. Ron Hodges was in the minors, but not permanently. Harry Parker had put down stakes in the bullpen. The callups from a couple of years earlier were making strides — Bob Apodaca (13 saves) more so than Craig Swan (6.39 ERA), but strides were strides. George Stone, who might have been asked by Yogi Berra to start at least one more game in a recent October, was thought more or less recovered from arm problems. Yogi managed as he had in 1973, though apparently not enough, because he didn’t last the duration of 1975. Then again, neither did Jones, who had a falling out with Berra, which led to an unconditional release that reads as unthinkable in retrospect, but real time didn’t sit still to take stock of how good a player used to be. Jones was, in the middle of 1975, a .240 hitter judged insubordinate by his manager. Berra was a manager whose alleged contenders trailed Pittsburgh by 9½ at the two-thirds mark. Berra was next an ex-manager, replaced by coach Roy McMillan.

Cleon and Yogi had had it already by the summer of ’75, but they weren’t the only ones for whom it had been called a day in Flushing. The all-time Met hit king, who had batted .340 in ’69 and sizzled through September of ’73, was shown the door not only weeks before Yogi was told it was over for him, but also not so many months after Tug McGraw, Ken Boswell, Duffy Dyer, Don Hahn and Ray Sadecki were dispatched to distant precincts following the massive Met disappointment of ’74. They’d all been heroes of or at least contributors to pennant drives past. But past was past. Thank you for your service. The present is presently all that is accounted for.

So maybe most days it couldn’t be 1969 or 1973, but as a 12-year-old, maybe I didn’t want 1975 to be moored solely to what had been. I loved all we’d pulled off when I was 6 and again when I was 10 — it helped explain why I’d been a Mets fan literally half my life — but I sort of wanted to move forward, to race toward second, as it were. I didn’t want to be merely satisfied by the presence of old faces. I wanted to be excited by new faces. Old faces that looked different once they were under a Mets cap would suffice just as well.

Joe Torre, whose 1967 baseball card was my first, now wore a Mets cap as he attempted to dislodge Garrett from third. So did Jesus Alou, who had played in the same outfield with his brothers in 1963, against the Mets, just after Cleon Jones was initially promoted. Alou was a .350 pinch-hitter from the right side, complementing Kranepool’s .400 clip from the left. Del Unser had been around. Now he was a Met, and a superb one at that; should’ve made the All-Star team, I’ll never tire of mentioning. Gene Clines was always a Pirate. Now he, too, was a Met. Likewise former Astro Bob Gallagher, former Giant Mike Phillips, former Red Tom Hall and a couple of American League relievers who existed for me mostly in the pages of Baseball Digest: Ken Sanders and Skip Lockwood. Big Dave Kingman, who in 1971 simultaneously socked a home run off both Jerry Koosman and a bus minding its own business in the Shea Stadium parking lot when visiting from San Francisco, was suddenly a Met, purchased in Spring Training. Soon Sky King (don’t call him Kong) owned our all-time single-season franchise home run record, a mark I assumed by law would always belong to Original Frank Thomas.

We had imports representing varying degrees of exotica and we had kids of our own breaking through the grass ceiling and introducing themselves as Mets in full. Rick Baldwin, 21, put on Tug McGraw’s 45 and got warm in the pen. Randy Tate was almost as young and just as new; he wore 48 and almost threw a no-hitter (which is to say he didn’t, but still). Another rookie, John Stearns, accompanied old Del Unser and fairly familiar if frighteningly fleeting one-game wonder Mac Scarce from Philadelphia, so technically Stearns wasn’t homegrown, but he was as fresh-faced as it got behind the plate on the days Grote wasn’t catching. If you read the Sporting News, as I began to the summer I was twelve, you salivated at the realization that we had a third baseman coming along who was leading the International League in runs batted in. His name was Roy Staiger and he, too, would be elevated to the majors by the Mets in 1975.

Move over, Garrett. Move over, Torre. Staiger’s here! Oh, the things I thought when I was twelve.

This blended roster-family of old, new and newish gave me many a moment and milestone across my seventh season as a fan. But the player who punctuated all this dizzying activity most tantalizingly — not with a period, but with an ellipsis, as if to indicate there was more to come — was Mike Vail, a heretofore underpublicized August callup who electrified September. There was no deafening buzz that I can recall soundtracking the promotion of Mike Vail. Vail hadn’t habitually haunted the back pages of the Official Yearbook. He wasn’t hailed as a Future Star and had never gotten our hopes up.

Hold Tide. Mike’s coming. Unless you were tracking the St. Louis Cardinals’ farm system (where he’d been fellow Northern Californian Keith Hernandez’s roommate), you probably hadn’t heard of him a year earlier. I’d heard of him only the previous fall when I’d read that he was the throw-in to the deal that sent utilityman and 1973 alumnus Teddy Martinez to the Cards for utilityman and former Indian Jack Heidemann. If you’re considered the extra guy in a trade that swaps who’s slated to sit, you’re just asking to be overlooked. For whatever reason, Vail’s name, however small the type it might have been printed in when the papers first reported his acquisition, stuck with me immediately and stayed with me indefinitely. Yeah, I thought, we got a lot of new guys for next year, but nobody’s talking about Mike Vail. I was feeling a little pride of propriety in his forthcoming fortunes. Maybe I figured we who sported punchy two-syllable names had to stick together.

Coming into 1975, Vail was 23 and a four-year minor league veteran. It’s not as if the numbers implied he couldn’t hit. In ’74, the righty batted a combined .334 at Single-A Modesto and Double-A Arkansas, but promising outfielders in the Cardinal system had to wait in line behind Lou Brock, Bake McBride and Reggie Smith. St. Louis was set. Vail grew antsy and requested a trade. To show just how sophisticated the scouting of prospects could be in bygone decades, GM Joe McDonald detailed for the Sporting News the intricate strategizing he undertook with his Cardinal counterpart, Bing Devine, in order to land Mike on the Mets.

“When Bing and I decided to swap Martinez and Heidemann,” Joe said, “I felt we needed another player in the deal. I asked for Vail, and Bing said OK.”

The 1975 yearbook’s YOUNG MEN WITH A FUTURE page featured eight players; none was Mike Vail. Instead, Vail rolled in with the Tides. He proved high Tide. Highest International Leaguer, in fact. Mike hit .342 at Triple-A, better than every player in his circuit (Pirate infield hopeful Willie Randolph was IL runner-up, with a .339 average; Ellis Valentine in the Expo chain finished fifth, at .306). A big chunk of that .342 was built on a 19-game hitting streak that pretty much compelled his callup. His AAA season was enough to earn him International League MVP honors, a prize never before won by a Tide and something snagged the year before by Jim Rice, who was only propelling the Red Sox to first place in the AL East this year. Thus, despite no springtime hype, and no play on page 58 among the rising Brock Pemberton, Rich Puig and Luis Rosado types, Vail hit his way to New York, debuting on August 18 and validating my determination to let his name rattle around in my consciousness all summer.

At the time, the Mets’ outfield seemed to invite little in the way of flux. They may not have been Brock/McBride/Smith, but in right, incumbent Staub was on his way to pounding out those team-record 105 RBIs; in center, former Phillie Unser had settled in nicely en route to posting a .294 average; and in left, Kingman was taking dead aim at Thomas’s franchise mark of 34 home runs, a total that had sat undisturbed since 1962. Then again, Kingman (who had usurped Jones’s position before Cleon’s tenure met an ignominious end) was said to be versatile, having played first and third for the Giants…and, quite frankly, he wasn’t putting down defensive roots in left. The Mets were scuffling to remain viable in the division race, hovering a little above .500 and clinging unconvincingly to wishing distance of the first-place Pirates. A team in the Mets’ position could hardly turn down a .342 batting average, regardless of its league of origin.

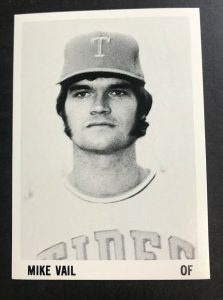

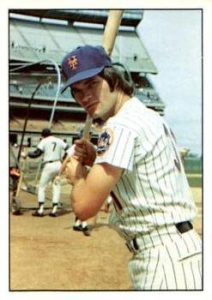

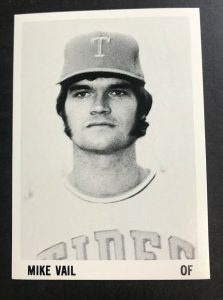

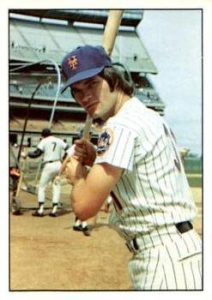

Mike, whose publicity photo revealed a Prince Valiant haircut, had to take his first NL swing inside the Astrodome against fireballer J.R. Richard, as intimidating an hombre as any rookie could encounter. Talk about being welcomed to the big time. Yet Vail announced his presence with authority, producing a pinch-hit single. Logging a 1-for-1 and holding a 1.000 batting average was not an inauspicious way to get Vail’s party started.

Soon Mike’s soirée became a full-time affair. He got his first start in left on August 20. The position became his for keeps on August 25. With corner outfielders Vail and Staub flanking a platoon of Unser and Clines, the Mets commenced contending in earnest. The club that had faded behind Berra discovered depth behind McMillan. Late August wound down with a five-game winning streak in Southern California and the Mets creeping to within four lengths of the Pirates. Seaver, Koosman and Matlack threw complete games in succession. Kingman was up to 28 homers. Staub had 90 RBIs.

The future looks like this SSPC card when you’re of a certain age. And Mike Vail was the hottest Met of all. In San Diego, he went 9-for-14. In L.A., he notched a hit a day. When the Mets returned to Shea to open September, Vail belted his first home run, off John Candelaria, to give Tom Seaver a 1-0 first-inning lead. It was all Tom would need en route to completing a four-hit shutout. It was not only Seaver’s 20th win of the year, it included his 200th strikeout of the season, the eighth consecutive season he’d fanned at least that many. It was an all-time baseball record and it rightly received the lion’s share of attention that Labor Day afternoon.

But if you were paying attention, you couldn’t help but notice that Mike Vail had hit in nine games in a row. And once the Mets leveled off and unfortunately fell away from their chase of the Pirates, you mostly noticed that Vail had kept hitting, at least one hit in every game as September got going. On September 3, the day I started junior high, Vail’s streak reached ten. On September 7, as the Mets finished a dishearteningly dreadful homestand (they’d won both of Seaver’s starts but dropped their four other contests), the streak stood at 14. A three-game sweep by the Expos at Jarry Park essentially buried the Mets’ divisional aspirations — they were nine out with eighteen to play — but Mike just kept getting mightier. He hit in every game in Canada and now claimed a hitting streak of 17.

Did you know what the record for a Met hitting streak was? In the course of 1975, we’d been reminded that among Mets Tommie Agee had collected the most hits in a season (185), Donn Clendenon had driven in the most runs (97) and, of course, Frank Thomas had the most homers (34). Those standards were in the course of being refashioned by Millan (191), Staub (105) and Kingman (36). But streaks don’t build over a season. They appear out of nowhere, not unlike their architects sometimes. Vail was a throw-in when Felix, Rusty and Sky, not to mention Tom, Jerry and Jon were excelling. Now Mike was front and center for us, and Jack Heidemann (.214 in limited action) could be considered the throw-in to the Vail trade.

The record for a Met hitting streak was 23, established by erstwhile Met left fielder Cleon Jones in 1970. This was getting mentioned regularly. Ditto for another nugget: the record for a hitting streak by a National League rookie was also 23, shared by Joe “Goldie” Rapp of the 1921 Phillies and equaled in 1948 by another Phillie — and Original Met — Richie Ashburn. The division title hopes were gone. Seaver’s quest for the Cy Young appeared secure. There was time for Staub and Kingman and Millan to do what they were trying to do; even Millan’s goal (or our goal for him) of playing every single game, something no Met had ever done, would have to wait to unfold, one by one, until it got to 162. What Mike Vail was doing was all about immediacy, the fierce urgency of now. He was, as a new late-night television show set to debut in about a month would announce itself, live from New York.

Mike Vail had breathed life into the cause surrounding a team otherwise running out of time. As fans, even when we’re 12-year-old fans, maybe especially when we’re 12-year-old fans, we need a cause. In September of 1975, we needed Mike Vail’s hitting streak to keep on keepin’ on.

On September 10, the Mets traveled to Pittsburgh for a two-game series that no longer much mattered in the standings. Seaver lost the first game. Koosman won the second. Vail hit in both. The streak reached 19. The succeeding weekend brought them to St. Louis. Folks at Busch Stadium got to see what Devine deemed expendable. Vail went 1-for-3 on Friday the 12th; 2-for-5 on Saturday the 13th; and 1-for-4 on Sunday the 14th. The former Cardinal farmhand was now a lifetime .347 major league hitter riding a hitting streak of 22 games.

On Monday, September 15, the Mets welcomed Montreal to Shea Stadium. Steve Rogers was the opposing pitcher. Rogers retired Vail on a grounder in the first and a hard liner in the fourth. In the sixth, however, with the Mets trailing by two and Unser on second, Mike’s golden rap came at last. It was a single to center. The Mets halved the Expos’ lead but, honestly, more important was all at once Vail tied Goldie Rapp, Richie Ashburn and Cleon Jones. It was as long a hitting streak as ever forged by an NL rookie; by a New York Met; or any player anywhere in 1975 — the longest in that last category.

I, alone in my bedroom, went suitably nuts. The sparse Shea crowd of 7,259 that had been chanting, “LET’S GO MIKE!” stood and applauded for two solid minutes. But they’d have a little more to cheer two innings later when, with the score tied, Vail came up again, this time with runners on first and second, and stroked another single off Rogers, this one to left. Gene Clines came home to give the Mets a 3-2 edge, one maintained in the ninth on Skip Lockwood’s first Met save.

What a maiden voyage into the big leagues for Michael Lewis Vail. In crafting his record-tying streak, he batted .364, with 36 hits in 99 at-bats — a “steady rat-atat-tat of base hits,” in Jack Lang’s beat-writer lingo. Better than the numbers was the hope he represented. The Mets hadn’t developed many hitters in their 14-year history, hardly anybody beyond Cleon Jones and Ed Kranepool when it came to Met longevity. Mike might not have been seeded on the farm, but he did hone his skills as a Tide, and we Mets fans embraced him as our shiningest future light.

The streak ended the next night in an eighteen-inning game (Mike went 0-for-8), but the brief rookie campaign had worked its magic. Vail concluded 1975 with a .302 batting average and a grip on the Metsian imagination. When Joe Frazier, his skipper with the Tides, was introduced as the Mets’ next full-time manager, one of the questions Frazier received was whether he had any more Vails down there. Joe and everybody at the press conference laughed, because, yes, that’s exactly what we needed. More Mike Vails. More record hitting streaks. More future. We’d seen so many icons of 1969 and 1973 go. The day after the ’75 season ended, our first manager, Casey Stengel, died. On the day the ’75 playoffs started, our only owner, Joan Payson, passed on, too. Yes, we could really use some future around here.

Vail’s 1975 was truly a treat. Instead, we got a slap in the face come December when McDonald’s track record for offseason heists went off the rails. At the urging of de facto showrunner M. Donald Grant, the GM got rid of Rusty Staub before Rusty Staub accrued the contractual ability to veto trades. The news was dispiriting as all get out: Staub and Tide pitcher Bill Laxton to Detroit for Mickey Lolich and minor league outfielder Billy Baldwin. Lolich, 35, had been a helluva lefty for the Tigers…several years earlier. Staub, 31, was at his peak as a Met, both as an icon and as a hitter. He’d stay at his peak in Detroit. After driving in 105 runs for the Mets in ’75, he’d average 106 runs batted in for the Tigers across 1976, 1977 and 1978. (And, by the by, Baldwin wasn’t destined to morph from throw-in to steal.)

The only aspect of the Staub trade that made the transaction remotely palatable didn’t emanate from contemplating whatever Lolich might do in a new league. It was from knowing that at least the way had been paved for Mike Vail to continue developing as an everyday player. True, he’d played left for the final month-plus of 1975, and he’d be assigned Rusty’s old perch in right in ’76, but if Dave Kingman could be versatile, so could Vail. At least we’d have that to look forward to.

Except, no, not really, because Mike played a little hoops in the offseason and dislocated his right foot on the court. The damaged Achilles tendon kept him off the baseball field until June. The Mike Vail who returned wasn’t the Mike Vail we remembered. He batted .217 as a part-timer and never strung together more than five consecutive games with at least one base hit in all of 1976.

Meanwhile, Frazier’s management style didn’t win many games after ’76, nor did it retain the confidence of those making the decisions above him. He was gone before June of ’77. Others would be gone in June of ’77. The less said about the post-Payson ownership situation in the late 1970s, the better. The future that awaited Mike Vail and the Mets was not much future at all. Mike didn’t light up anybody’s life in 1977, leaving him to be claimed off waivers by Cleveland in the Spring of ’78. We’d see him again quite a bit as a Cub, for whom he once blasted an eleventh-inning grand slam off Dale Murray that somehow didn’t beat us.

Mike wound up playing for seven different teams in a career that spanned ten seasons, compiling 447 base hits in all, or 447 more than anybody writing or reading this ever has or ever will. His last year, with the Dodgers, came in 1984, or one year before Rusty took his final bow, fortunately in a Mets uniform, with new management having reacquired him five years after the previous regime shipped him to Michigan.

The story of Mike Vail’s Metsian journey, if you venture beyond the ellipsis, tends to curdle (as too many Met stories do), so let’s rewind it to where it was its most delightful. Let’s abide by what was written on Mike’s behalf in the 1976 yearbook, when his 1975 exploits were still fresh in everybody’s recollections…

“Collected more ink and superlatives than any rookie in Met history after reporting from Tidewater.”

I wasn’t baseball-conscious in 1967 when Tom Seaver first dropped by from Jacksonville, but putting aside that possible freshman-sensation omission, yeah, it’s true. Mike Vail came out of the box ready-made and astounding. I was older at the end of the 1975 season than I was at its beginning — a hazard of aging, it seems — but I was still 12. At 12, my analytical approach to the game allowed me to project forward with utmost confidence that if this guy is this good for us now, he’s gonna keep being great for us forever, or for however long he plays for us, which will clearly be for a very long time. I was sure of it. I was sure of Vail.

“It definitely for me has a ‘my favorite year’ quality to it,” Conan O’Brien once said of his experience writing for Saturday Night Live, a program that debuted on October 11, 1975. “I’ll never be that young and naïve again.” In the fall of 1975, I was that young and naïve, and I had years of Mike Vail to look forward to.

In my heart, sometimes, I still am and I still do.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1965: Ron Swoboda

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1967: Al Schmelz

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1971: Tom Seaver

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1974: Tug McGraw

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1986: Keith Hernandez

1988: Gary Carter

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2007: Jose Reyes

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2010: Ike Davis

2011: David Wright

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2017: Paul Sewald

2019: Dom Smith

by Greg Prince on 18 September 2020 12:22 pm Jules, y’know, honey, this isn’t real. You know what it is? It’s St. Elmo’s Fire. Electric flashes of light that appear in dark skies out of nowhere. Sailors would guide entire journeys by it, but the joke was on them. There was no fire. There wasn’t even a St. Elmo. They made it up. They made it up because they thought they needed it to keep ’em going when times got tough, just like you’re making up all of this.

We’re all going through this. It’s our time on the edge.

—Rob Lowe as Billy Hicks

The 1993 Jets were supposed to be better than they were. They’d made big-deal offseason acquisitions. Boomer Esiason. Ronnie Lott. Then they went out and played as the Jets tend to play, losing four of their first six games…after which safety Brian Washington defiantly declared they were “the best 2-4 team in football”. While this pronouncement didn’t go down well in the New York media, it’s difficult to mount an argument regarding a status nobody had previously ever thought of contesting before.

With that in mind, I’m here to tell you that after 50 games, the Mets are the best 23-27 team in baseball. Also, they’re the only 23-27 team in baseball, so that probably makes them the worst of their kind as well. How it is we have thirty baseball teams and only one with this precise record is probably a bigger mystery than how the Mets, at four games under .500, are still something of a playoff contender, but let’s assume the game totals will more or less even out by next Sunday. For now, let’s celebrate the surge that has brought the Mets to their unquestioned position atop the mountain of 23-27 teams in baseball.

WOO!

Honestly, it’s been pretty invigorating watching this team both not lose and somehow win these past two nights, considering the one undeniable strong suit they thought they had going for them — the upper echelon of their starting rotation — got its asset kicked. Yet they survived the thrashing and battled on, just like a real team with something to play for in the third week of September. Wednesday, it was Cy deGrom and his amazing, colossal, spasming hamstring splattering our time-tested formula for competing all over the Delaware Valley. But then the Met relief corps, under the direction of bullpen coach Nancy Walker, acted as the quicker picker-upper, and the Met offense proceeded to score just enough to wipe Jake’s and our slate clean.

Thursday night, there was another fine mess that had to be absorbed ASAP, this one spilled by the heretofore reliable Seth Lugo. We’ve long considered Seth a competitor to the leading national brands of starters, but sadly he proved too soggy to be of much use. After the Mets had put three on the board in the top of the first, Lugo took to the mound and got supergenerous with the givebacks. A homer to Harper. A homer to Bohm. A homer to Gregorius. A triple to Segura, who usually homers against Met pitching, but that’s OK, because here came Adam Haseley to drive him in.

After one, it was Phillies 4 Mets 3. Before Lugo could slither out of the second, it was Phillies 6 Mets 3, with Bryce bashing another dinger along the way, and did you hear Seth’s hamstring barking? Me, neither, but after an inning-and-two-thirds of this Citizens Band Box horror show, you wouldn’t have blamed Luis Rojas for invoking any malady he could think of and bringing out the hook. Just as deGrom blessedly swears he’s fine after his spasm revelation, Lugo claims he is physically well. He just sucked was all. “I made some bad pitches, but I also made some pitches that got hit, too,” Seth said, shedding absolutely no light on the situation.

Erasmo Ramirez, on the other hand, was nothing but light. Light so bright than no smoke from a distant fire could dim his effect on our fortunes. Like Michael Wacha the night before, Ramirez strolled in and clamped down the Philadelphia chaos. Erasmo for two-and-a-third, followed by Chasen Shreve for two-and-a-third, followed by Jeurys Familia for one-and-a-third. Put all these ones and two and thirds together, and suddenly you’re back in a game you were plummeting from a few full innings before.

In the top of the sixth, the Mets opted to stop being impressed by Phillie starter Aaron Nola and returned to attacking him successfully. Pete Alonso, who was so desperate for a big hit the night before that he tried batting and chewing gum at the same time, regenerated his swing and blew a bubble right in his Nola’s face by launching a bomb to left field. Pete can still do that. He has 12 home runs in this year and, I’m guessing, about 16 hits in all. Still, when he connects, he detonates, and after Jeff McNeil worked out the Mets’ fifth walk of the night off Nola, Joe Girardi replaced his ace with pure dynamite.

It doesn’t really matter who Girardi brings in from the Phillie bullpen. They’re all potentially explosive to the touch. Blake Parker was ol’ Joe’s choice. Andrés Giménez patiently ignored the ticking device and took a walk. Soon enough, though, Brandon Nimmo lit the fuse: tripling in both McNeil and Giménez and tying a game that appeared lost in the second. Except these are the Mets in Philadelphia, where few leads sit undisturbed for long. The only thing more common than games there getting tied and untied is the SNY shot of cheesesteaks sizzling. And because the SNY camera crew is not in attendance on the road this year, we didn’t even get that.

The 6-6 tie stayed in effect until the ninth when another Phillie reliever burst into flaming wreckage. Brandon Workman threw. Brandon Nimmo swung. We had a Brandon new pair of roller skates and Nimmo was the Brandon new key. Our Wyoming Walloper blasted it so far that he didn’t even bother sprinting to first, which may be a Nimmo first.

“The guys had two choices,” Nimmo would say later. “Give up, or keep fighting. The guys chose to keep fighting.” God, I love that inspirational introspection when it comes out of the mouths of Mets. As the Mother Superior in Pee-wee’s Big Adventure might have put it, “Oh, Brandon, you are an inspiration to us all!” To which the next several hitters in the Mets lineup essentially replied, “We’ll say! We’re going to start a paper route right now.”

Read all about it: Michael Conforto singled; one out later, Dom Smith tripled; immediately thereafter, Robinson Cano homered. It was a bounty of runs, indeed. By the time Cano extended the Met lead to four, Garrett Cleavinger had replaced Brandon Workman, but it barely mattered. Phillie pitching provided the gravy for this delicious dish of savory offense piled over a steaming bed of scoreless innings. With no cheesesteaks in evidence, the Mets had to find another way to feast. Ramirez. Shreve. Familia. Justin Wilson in and out of a little trouble but ultimately unscathed. And, at 10-6 and with no save opportunity in sight (unless he created one for somebody else), Edwin Diaz came in and finished the job. The job got tense — Sugar may have been on third-day fumes — but it got done. The Mets emerged from a series they couldn’t lose by winning it. DeGrom was no good. Lugo was lousy. Yet the Mets took two of three to become…

THE

BEST

23-27 TEAM

IN BASEBALL!

Which gets them…what? Maybe nothing. Probably nothing. They inched a little closer to something than they were 24 hours earlier (which is about how long this game took), but there are still a few too many bodies between them and whatever it is they’re trying to grab, which, by the way, can be defined as the second-best sub-second place record in the National League, a status nobody had ever thought of contesting before. Talk about an inspiration to us all.

That said, when a camera briefly spotted Todd Frazier looking pleased with the outcome, I thought to myself, “I wonder if they’d put him on the postseason roster,” a postseason roster we’ll make up because we think we need it to keep us going. Maybe we do.

by Greg Prince on 17 September 2020 11:23 am Jacob deGrom gets hit like Jacob deGrom never gets hit. Then Jacob deGrom leaves with an injury like Jacob deGrom does in our worst nightmares. Then the Mets, down by three in the third, turn to Michael Wacha, a lapsed starter the Mets resist turning to as a matter of course. Then the Mets run the bases without regard for doing it well.

Then the Mets win?

Yes, then the Mets win. They won Wednesday night’s game against the Phillies and won the Go Figure Cup, awarded annually to the team that has no earthly business winning a game they were so clearly destined to lose.

Destiny took a holiday for a change. The Mets have lost enough games they seemed moments from winning that it was about time they had one mysteriously float over from the ‘L’ column. And it’s not like they weren’t proactive about making it happen. Wacha hung in for four very solid innings, giving up only a solo homer to Jean Segura in the third, which made the Mets’ deficit 4-0 and the Mets’ likelihood of prevailing highly unlikely.

But this whole season has been unlikely, so why not keep watching and divine whatever good news there was to be discerned? Like Jake was gone not for the season but probably for no more than the five days until his next scheduled start because all that ailed him was a hamstring spasm. I sometimes get those sitting at my desk typing, but I don’t use my legs nearly as much as Jake does. Jake’s Cy Young chances may wind up falling outside the razor-thin margin for error, given that his ERA shot up above 2 during his two uncharacteristic non-deGrominant innings, but if he doesn’t win it, we can dismiss the awarding of a Cy as rather silly in a sixty-game sprint.

And if he does somehow win it despite an earned run average of 2.09 (gasp!) with no more than two starts remaining, we’ll change our tune without missing a beat and revert to singing the praises of the wisdom of the BBWAA.

Besides, no matter what happens with the Cy, we’ve already captured the Go Figure Cup. Go figure, Wacha was fine after Segura crushed him, and so were Justin Wilson, Miguel Castro and the recently less cringe-inducing Edwin Diaz for an inning apiece after Wacha left. Go figure, J.D. Davis, playing this strange position wherein he bats several times a game yet doesn’t trot out to the field at all, homered and drove in three runs. J.D. going deep may not sound worthy of going figuring, but Mr. Davis had not hit one out since August 18, or nearly a month before, for those of you who no longer bother with niceties like calendars.

One of the runs J.D. drove in, the one that tied the game at four in the eighth, scored via the seemingly disinterested feet of Michael Conforto. Michael had walked with two out. J.D. doubled to center. Michael only sort of ran from first because he didn’t seem aware that there were two out. What should have been a fairly easy tally became uncomfortably close at the plate. It was still a run, but it was a little too typical of how the Mets have run themselves out of innings of late.

There’d be more of that in the ninth: more scoring, more running without thinking the process through. The good part was built on Robinson Cano converting a Hector Neris quick pitch into a single up the middle; pinch-runner Amed Rosario taking second on a Neris balk; and Andrés Giménez taking advantage of Joe Girardi’s decision to intentionally walk Jeff McNeil to instead take on the rookie. Giménez responded with the tie-breaking single, as Rosario sped home without incident from second. The abhorrent part came during the succeeding at-bat, as Jake Marisnick struck out; the ball got away just a little from catcher Andrew Knapp; Giménez took off prematurely from his base; Knapp threw to second; McNeil took off from third; and McNeil got himself tagged out attempting to dive into home by second baseman Scott Kingery, who rushed in with the ball to end the inning.

Yet the Mets didn’t suffer for their foibles and misfortunes. Davis got to Zack Wheeler, Cano and Giménez got to Neris (as does every Met, eventually) and Diaz in particular got the ball over the plate in mostly unhittable fashion, recording three swinging strikeouts that rendered a single somewhere in between shockingly harmless.

Mets 5 Phillies 4. Go figure. Mets still sort of in the playoff picture. They’re two-and-a-half out of a playoff spot with eleven to play and three teams between them and the team they have to reach. Go figure that if you are so inclined. Or just be thankful for small favors and spasms that aren’t fatal.

by Jason Fry on 16 September 2020 11:46 am The Mets played one of their more discouraging games of 2020 on Tuesday night, one that left me so dispirited and annoyed that I decided this morning everyone would be better off reliving the misadventures of Paul Sewald, Jonah, than revisiting what had happened more recently.

Fighting for their lives against the Phillies, the Mets … never really seemed to be in it. Rick Porcello pitched tolerably, briefly losing his way in the fourth for two runs and then making a mistake against Didi Gregorius in the fifth for two more. Which wasn’t great, but it was better than Porcello’s been for too much of the season. And given the Mets’ offensive firepower and the Phils’ flammable bullpen, four runs shouldn’t have been insurmountable. Except they were — the team left 12 men on base, turned 11 hits into just one skinny run (and that came on a Brandon Nimmo solo shot), and failed repeatedly in the clutch. Which you could feel the whole time — it was almost as if you could sense guys tightening up as they came to the plate, squeezing the bat until sawdust shot out from between their fingers.

Wilson Ramos was the biggest offender: inning-ending grounder back to Jake Arrieta in the second with runners on second and third, K in the fourth, inning-ending GIDP on JoJo Romero‘s first pitch with runners on second and third in the sixth. But the Buffalo had company: Pete Alonso flied to center with the bases loaded to end the third, flied to right with one on and none out in the sixth, and fouled to the catcher with one on and one out in the eighth. Alonso is popping everything up and spent large chunks of the game hanging miserably on the dugout railing, looking like the woebegone protagonist of approximately 70,000 country songs featuring deceased dogs, vamoosed wives and busted barns. Jeff McNeil made a boneheaded play to short-circuit the eighth, getting tagged out at third when he a) didn’t need to advance, b) a run was going to score, and c) Jean Segura had no play except for the one McNeil gift-wrapped for him.

It was that kind of night. Afterwards, Luis Rojas talked about poor-quality at-bats and McNeil’s lack of awareness, and Ramos said something that everyone trying to work through COVID can sympathize with: “I’m overthinking every night because I have nothing to do.”

True … except 29 other teams are dealing with the same problem, and a bunch of them have a better chance to make the playoffs despite having less talent than the Mets. And hey, fairness to the other guys on the field: The Phils’ bullpen stood up, at least for one night, and Joe Girardi came up aces with the decision to send Adam Haseley up as a pinch-hitter in the fourth, which seemed overeager at the time but gave his team the win.

There’s no way the Mets should be behind the Marlins or Giants, but the standings say they are, and that’s the only judgment that matters. The Mets are rapidly running out of time to change that judgment, and they’ve given little indication that they’re capable of forcing a different one.

by Jason Fry on 15 September 2020 2:46 pm Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

Every Met roster seems to have one — a guy who slumps around under a little black cloud, trailed by misfortune both chronic and mysterious. Mysterious because he doesn’t seem to deserve what happens to him over and over again, or at least not the “over and over again” part. And because he doesn’t strike you as devoid of ability, or as a bad teammate.

There are words for this kind of player and for this kind of person, as this isn’t just a baseball phenomenon but an unfortunate aspect of life.

“Schlemiel” is the Yiddish word, with the added context (helpful for those of you who vaguely remember Laverne & Shirley) that the schlemiel is the guy who spills his soup and the schlimazel is the guy whose lap it lands in — which, in baseball terms, makes all of us groaning in the stands or on our couches the schlimazels. But the word I’ve always used is Jonah, which is sailors’ lore for a passenger or crewmate who brings bad luck. I think I prefer that one because a baseball team is like a ship’s crew, isolated and trying to get along in a little self-contained world beset by dangers.

The difference between a Jonah and other crewmates not quite fit for duty can be subtle — it’s easier to define what a Jonah isn’t than to nail down what he is. A Jonah needs a certain modicum of talent — your overmatched emergency starters and stone-fingered infielders don’t count, because they shouldn’t have been put it that position in the first place. A truly tragic or star-crossed player isn’t a Jonah either, because when a Jonah screws up your reaction should be more of a sigh than remote-throwing, drywall-punching rage. Life with a Jonah is a grinding, corrosive series of letdowns, not a sequence of blowups that leave craters in the soul. And a Jonah need not be universally viewed as such — the identification can be completely subjective, with one fan’s Jonah another fan’s guy to merely shrug and grumble about.

Which brings us to the 2017 Mets, and Paul Sewald.

The 2017 Mets, in case you’ve forgotten, were deeply terrible in a boring way that you could feel gnawing at your fandom day after day after identical day. This was a team that gave five starts to Tommy Milone, a reliably horrible starting pitcher. (He posted an 8.59 ERA.) Neil Ramirez was a living metronome of suck that ticked and ticked and ticked until I wanted to ram an icepick through both eardrums. Jay Bruce was the top guy in most offensive categories, which might define damning with faint praise. David Wright spent the entire year on the shelf with what turned out to be spinal stenosis. Michael Conforto‘s season ended when he dislocated his shoulder swinging and missing. With every ambulatory outfielder traded or injured, Nori Aoki was brought in late to supply basic competence and felt like a savior. A fire sale of formerly useful players brought back nothing but identically lousy right-handed relievers. Tomas Nido collected his first big-league hit in a meaningless game against the Cubs and ended that game about two minutes later by being tagged 25 feet shy of home plate by the pitcher. The highlights of the year were the presence of Jacob deGrom, cameos by Amed Rosario and Dominic Smith, and the fact that the season actually did end.

The first new Met of 2017 was Sewald, a 25-year-old right-hander from Las Vegas who’d looked perfectly useful over five seasons in the minors, working exclusively in relief. Sewald made his debut on April 8 at Citi Field, entering in the eighth inning of a game the Mets were losing to the Marlins, 4-1. Facing the bottom of the order, he gave up consecutive singles to Adeiny Hechavarria, Dee Gordon and J.T. Realmuto, then retired his only batter when Miguel Rojas sacrificed home a second run.

Not a great debut, but many debuts aren’t great. Sewald looked better in his next outing and again when summoned back to New York in May, but June was a disaster and he finished the year with a 4.55 ERA and an 0-6 record. There’s a blinking light of early onset Jonahdom — no lucking into a win, plenty of stumbling into a loss. In 2018 the Mets were better but Sewald was not — he posted a 6.07 ERA and an 0-7 record, running his career mark to 0-13.

That 0-13 mark probably makes you think of poor Anthony Young, who infamously went 0-27 from 1992 into 1993. But Young, while deeply, improbably and tragically unlucky, wasn’t a Jonah. During his year of misery, your primary thought was that he deserved better. A Jonah rarely elicits such sympathy. Armando Benitez and Braden Looper and Edwin Diaz weren’t/aren’t Jonahs — they had too much talent for that tag, and their failures induced too much rage to qualify. Jason Bay wasn’t a Jonah but a player whose sky caved in on him.

My first Jonah might have been Jose Vizcaino, a relatively blameless player in a statistical sense who nonetheless struck me as beset by deep flaws that were somehow communicable to his teammates. Call that weird prejudice, but weird prejudice is part of Jonah-hood. (Greg has always had a bone-deep loathing of Danny Heep, for no reason I can tell.) If you’re wondering, Vizcaino’s dagger into the Mets’ heart in the 2000 World Series in no way invalidates his Jonah status — Jonahdom is team-specific, and can be escaped with a change of affiliation.

Roger Cedeno was a Jonah, though I consign him to that status a bit reluctantly — he had more talent than your typical Jonah, but was dragged down into the Jonah spectrum by his chronic, sighworthy lunkheadedness.

Aaron Heilman was perhaps the Jonah-est Jonah who ever Jonahed, at least in orange and blue. Enough said.

Jose Offerman counts as a mild Jonah — he was pretty much cooked by the time the Mets brought him in, which isn’t his fault, but still managed to underperform a decent big-league track record.

Some people would call Mike Pelfrey a Jonah, but I blame the Mets for taking ace stuff and producing a pedestrian pitcher.

I detested Jon Niese, but dislike alone doesn’t make a Jonah — if anything it works against it, since a Jonah isn’t someone you want to root against.

Anyway, back to Sewald. After his unassuming start his win-loss record got worse and worse, eventually achieving Curious Factoid status. But the accumulating badness crept up on us — it’s not like anyone was rushing off to update the Sewald Watch, as had happened with Young. You’d be surprised to learn Sewald was now 0-9 or 0-11, but the surprise lay in the specific number, not in the general futility. That was thoroughly expected.

By 2019 Sewald was a known quantity, summoned for long periods from Triple-A but never quite securing a place in the bullpen. We knew his repertoire — meh fastball and changeup, good slider undermined by his lack of another pitch and his tendency to hang that slider at key moments. We had no objection to him as a teammate. We knew him as a standup guy in clubhouse interviews. We read that he was a smart player, interested in scouting reports and sabermetrics and always looking for a way to make his run-of-the-mill arsenal play better. The fact that his preparation never seemed to work? Classic Jonah indicator.

Sewald finally won a game last year — he was the pitcher of record when the Mets beat the Marlins on a bases-loaded walk in the 11th inning at Citi Field in late September, breaking his losing streak at 0-14. He made one final appearance that season, giving up the first of Hechavarria’s deeply annoying home runs in the finale won by Dom Smith. There’s yet another another telltale of Jonahdom — any rare bit of good news is followed immediately by a reminder of who you really are.

Sewald has plied his trade with the Mets during this weirdo season, and while he hasn’t lost a game, at least not yet, he’s sporting a 13.50 ERA. When he takes the mound I sigh, not because I dislike him or root against him, but because I can guess that the kind of things that cause guys to have 13.50 ERAs are in the offing. He’s Paul Sewald, doughty and doomed. He’s a Jonah. It’s not his fault, but the fact that it isn’t his fault doesn’t change what he is.

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1965: Ron Swoboda

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1967: Al Schmelz

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1971: Tom Seaver

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1974: Tug McGraw

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1986: Keith Hernandez

1988: Gary Carter

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2007: Jose Reyes

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2010: Ike Davis

2011: David Wright

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2019: Dom Smith

by Greg Prince on 14 September 2020 8:53 pm The keys are a couple of months from formal exchange, but the hardware store has been put on alert to make up a new set for the new owner who is preparing to move into 41 Seaver Way.

Say “hi” real soon to Steve Cohen, your next control person of the New York Mets. We’ve heard such advice before, like less than a year ago, but this version of it’s really happening seems closer to real than ever before. For a reported $2.42 billion, it ought to be no further than six socially distant feet from our loving embrace. The parties have issued their respective statements that an agreement has been reached. Sterling Partners — you know them as Fred, Jeff and Saul — will sell our favorite baseball team, with hopes and dreams to be named later, to Cohen. You know him as our savior, whether ultimately he is or not.

He’s not a Wilpon, so that’s a start. Once he’s approved, which seems something verging on a given, then not being a Wilpon will only be the beginning. At some point, we will discover that having Steve Cohen calling the shots won’t be a 100% unadulterated delight, if only because no living, active sports franchise owner keeps a universal approval rating extant forever. The only ones we’ve really cared for in this century have been Joan Payson and Nelson Doubleday.

Suitable for framing, as Murph used to say about the team picture. But enough with waving the yellow flag indicating caution. Let your heart race with anticipation. Consider the players who will become available on the open market and either become Mets or not become Mets, but the result won’t be because there’s this murky Madoff residue lurking in the equation. Think about a front office potentially less encumbered and let loose to think ahead and thrive. Think about not cringing when you hear what “the owner of the New York Mets” has to say about the team he and we each have our own kind of stake in.

We’ll all see our own ink blot when we look at Steve Cohen taking charge and imagine our own version of Metsian nirvana. The reality has little chance of matching exactly our wildest wishes, but we’re probably going to like the net Met effect. To reiterate from the last time this seemed to be a sure thing, Cohen is a lifelong Mets fan who has resources like your or I have pocket lint. He saw the Mets at the Polo Grounds. He grew up down the LIRR tracks from Shea Stadium. He’s maintained a piece of the Mets at Citi Field. He’s not known to have fetishized Ebbets Field.

He’s been around. He’s been around the Mets. Think about it. Somebody who intimately knows our team still wants our team, and presumably for more than real estate reasons. Nice to know after all these years, so many of them unkind, that “Mets” means that much to somebody who has so much but wouldn’t rest until he had that.

Which he doesn’t quite, but he’s closing in. When the keys are turned over, then we’ll raise a glass. Make mine a Rheingold. Steve will understand. It never felt like Fred, Jeff or Saul would.

by Greg Prince on 14 September 2020 8:08 am The Mets shuffled off from Buffalo with one more loss than win for their weekend’s work and three fewer games remaining on their truncated schedule, thereby humbling their already modest postseason chances. Not that they were much to begin with, but sooner or later, you can take only so much comfort from relative proximity to a final playoff spot when you can’t string together more than a couple of wins at a time.

Sunday’s attempt to capture their series versus the Blue Jays dissipated quickly, as an onslaught of hits (8) against old nemesis Hyun-Jin Ryu produced a paucity of runs (1). Maybe there would have been more scoring early, but the mysteriously reappeared Todd Frazier ran the Mets out of their first-inning rally, and opportunities grew less plentiful from there. David Peterson returned to a more competent form than we last witnessed from the rookie — 5 IP, 3 H, 2 BB, 2 R — but the pieces refused to be put together overall. Relievers Brad Brach and Jared Hughes let the Jays do the walking, then the hitting. Toruffalo’s lead grew to an insurmountable 7-1 before settling in at a final of 7-3.

Despite dropping ten of their past sixteen contests, the Mets remain sorta, kinda in it. Five games under .500 with two weeks to go doesn’t necessarily disqualify you in 2020. It actually keeps you viable, just two games behind the least worst among the jumble of NL pretenders. Get hot, hope others in your lax bracket don’t and maybe you’ve got something there. Or as Leo McGarry once told Jed Bartlet, “Act as if ye have faith and faith shall be given to you. Put it another way, fake it till you make it.”

Sound like a plan? Not really. But it hasn’t stopped us from pinning our hopes on fragile bulletin boards before. It was only last September that we had no real chance at making the playoffs, yet we hung in with the illusion that we might for as long as we could. The sight of Ryu was a reminder of one of the high points derived from late 2019’s power of positive thinking. On this very date, September 14, Ryu of the Dodgers dueled deGrom of the Mets at Citi Field. It was indeed a genuine modern pitchers’ duel. Both aces went seven innings. Neither man gave up a run or a walk. Rajai Davis doubled with the bases loaded off Julio Urias to supply all the offense the Mets would get and need. The 3-0 win that Saturday night placed us three out of a Wild Card, statistically further than we are now from this year’s version of an October lottery ticket, but it felt a great deal more real. We had played for five-and-a-half months. We had a winning record. We had withstood Hyun-Jin Ryu.

It’s hard to believe I’m feeling nostalgic for an also-ran stretch run of incredibly recent vintage, but it felt real enough. The next night, an ESPN Sunday, had that do-or-die September quality to it. We didn’t quite do, losing in heartbreaking fashion to L.A., but we weren’t dead yet. Or maybe we were but refused to sign the death certificate. After being throttled in Colorado on Monday night, we were ready to call it a year. Then we won on Tuesday night, so we called it no such thing. And on Wednesday afternoon in Denver, when we came dramatically from behind to beat the Rockies once more, the race was as on as it could be. We were still three out and there even fewer games left with which to gain ground, but what’s the point of staying mathematically alive in September if you’re not going to milk it for all it’s worth?

The milking yielded little in the way of sustenance after Colorado. The Mets went to Cincinnati and didn’t sweep, which is what they pretty much had to do to maintain the contention illusion. After losing on Saturday afternoon to the Reds and slipping 4½ out with eight to play, Todd Frazier put on a brave face. “I felt like we had to go 9-1, so here’s our one,” he said. “Let’s roll from here.” The roll never came. The Mets were eliminated at home a few nights later.

During the early portion of this year’s Spring Training, before we knew nobody was training for anything, I saw Seth Lugo interviewed on SNY. Whatever he said didn’t stay with me. The image that accompanied his appearance, however, has lingered in my consciousness. It was a clip of Seth striking out a batter at Coors Field in that Wednesday afternoon game. It wasn’t identified by a graphic, but I recognized the situation. I recognized the shadows. September shadows. Pennant race shadows. The Mets’ chances didn’t exist beyond a shadow of a doubt, but the shadows knew they were still in it. Being still in it is its own triumph in September. That image of the shadows falling over home plate at Coors Field while Seth Lugo gave the Mets two innings to keep us incrementally alive kept me going as much as anything during baseball’s hiatus. Those shadows were where I wanted to get back to once baseball got back. Arrive alive at that juncture where the shadows encroach and keep rolling this time — if there was to be a “this time” in 2020.

This time isn’t much. There was a shadow over home plate not long after the 3:07 PM start in Buffalo on Sunday, but the minor league park there doesn’t have multiple tiers, so the effect of the shadow was negligible. As is the feeling that the Mets are still in it. Sometimes it seems the only commonality between the Mets of this September and last September is an overreliance on Todd Frazier.

by Greg Prince on 13 September 2020 1:16 pm In a sixty-game season whose primary appeal may be the encompassing of elements largely unprecedented, you pretty much have to be in it for those things you’ve never seen before. They may not add up to an orthodox major league campaign, let alone big-picture success, but they sure do get your attention.

Take a 1-unassisted at third base. Take it, frame it and hang it over the fireplace. Nobody seems to believe they’d ever seen one before Saturday night. Now we have. It was a beauty, for sure, executed by Seth Lugo out of sheer desperation. With runners on first and second in the home — which is to say Toronto in Buffalo — fourth, Vlad Guerrero, Jr., chops a ball to the left side. Lugo fields it. His momentum carries him toward third. His third baseman, J.D. Davis, has broken away from the bag, so all Lugo can do is race the baserunner from second, Travis Shaw, to third. The only way Seth can win the race is by sliding into the bag, which he does. He scurries, he slides and he gets the out. It was truly gorgeous, not to mention Amazin’.

It also goes down as one of those stirring defensive plays — Keith Hernandez stretching into foul territory like Gumby and creating a 3-1 forceout of Jose Cruz at first with Bobby Ojeda covering; Endy Chavez elevating to rob Scott Rolen over the left field wall and then firing to double Jim Edmonds off first in a certain NLCS game; Yoenis Cespedes setting off a throw as if from a cannon in center to nail and shock Sean Rodriguez at third — that occurs in service to a loss that can’t help but take the edge of the inherent enjoyment of the moment that took your breath away several innings before. Appreciation for its beauty may be hard to garner the next morning, but gosh, “what a play,” you’d have to say, no matter that everything else didn’t quite work out as a Mets fan might wish.

No, everything else did not work out Saturday night at Sahlen Field, speaking of largely unprecedented elements. The Mets absorbed their first-ever regular-season defeat in Buffalo a night after posting their first-ever regular-season victory in Buffalo amid their first-ever regular-season series in Buffalo. Pending the prevalence of viruses and the judgment of Canadian officials, we probably won’t be able to say, “the Mets are playing in Buffalo” ever again, so we might as well acknowledge the top-tier strangeness therein.

It’s been mentioned ad bisonem since the Toronto Blue Jays were motivated to temporarily make a home away from home out of the home of their Triple-A affiliate that New York State is currently if briefly home to three big league baseball clubs for the first time since 1957. Prior to the departure of the Giants and Dodgers, the “State” part of New York was implied. The last time Buffalo was big league in the baseball sense, the team was the Blues and the league was the Federal. The National League’s Buffalo Bisons stampeded from the scene following the 1885 season. Met notables from Ed Kranepool to Matt Harvey completed their finishing-school activities in Buffalo, but by then, the affiliation was decidedly minor. Buffalo tried to add an MLB franchise to its lineup of NFL Bills, NHL Sabres and (for a pre-Clippers spell) NBA Braves, but the effort never sufficiently impressed those who make expansion decisions. Roy Hobbs and the New York Knights played in Buffalo, but that was in the movies.

In 2020, with the Global Pandemic refusing to budge from leading every league in disruptiveness, it’s the Blue Jays hosting Eastern Division visitors from both leagues in not quite Ontario. On TV, it’s a good-looking park. Fresh, open-air, a pleasant antidote to the confining confines of the Rogers Centre. The fan experience is about the same as it is at Citi Field or any established venue. It’s empty as hell up there and the fans are noticeably flat, if cheeky in their presence. Gov. Cuomo claims a front-row perch in corrugated form. So does Geddy Lee.

The Met offense that scored 18 runs Friday night essentially also took a seat and sat by watching on Saturday night. Talk about flat. Nope, ya can’t save for tomorrow what you score today. For all the innovations shepherded into ad hoc existence by Rob Manfred, he has not allowed for the retroactive rejiggering of run stocks. Thus, two runs would have to do on Saturday for the Mets, and they didn’t do, as the Blue Jays scratched out three. Lugo looked good pitching as well as fielding, and the Met bullpen wasn’t particularly culpable, but the Mets didn’t make the most of their occasional opportunities versus former patsy Robbie Ray and his relief successors.

Perhaps I’m burying the twin ledes here: that Wilson Ramos didn’t come through at a crucial juncture and that Amed Rosario shut the books closed without allowing Howie Rose the chance to put a win in them. Perhaps you’d like to bury the instigators of those game-determining actions. I woke up Sunday morning so stoked by how well Seth Lugo executed his 1-unassisted and how novel the Sahlen setting was that I had nudged the worst of the Saturday night feebleness to a lesser level of my consciousness. I’m assuming neither Ramos nor Rosario has been unconditionally released since last night, nor have they been left by the side of the road out on the 190 beyond the center field fence, yet their respective misdeeds can’t be drenched in hot sauce like so many wings.

Yeah, I, too, was fuming that Ramos swung at a two-oh pitch after six consecutive balls had been issued by Toruffalo closer Rafael Dolis to start the ninth and proceeded to ground into the continent’s most unnecessary double play. And, yeah, Amed Rosario, having been given the gift of first base via a mishandled strike three on what the presumed final out of the ballgame didn’t have to return the favor by getting picked off for the definitive final out of the ballgame…though it was only defined as definitive once replay review took a look. Replay review did a lot of looking Saturday night. The crew in Chelsea was called on six separate times to intensely examine on-field yeas or nays from Sahlen. The last of their requested interventions, the one that ultimately ended Rosario’s otherwise splendid night (3-for-3 plus the heads-up dash to first base on strike three), reversed an umpire’s ruling that said Amed didn’t get picked off.

Was a game-losing pickoff another first for the Mets annals? I’m not sure, but I can’t remember another. I know the Mets once won a game when Frankie Rodriguez turned and flung to Ruben Tejada to pick Roger Bernadina off second. I know a World Series game was once ended on a pickoff play at first, but that forehead-slapper (Koji Uehara removing Kolten Wong in 2013) didn’t involve the Mets. Let’s say this particular result was unprecedented. Let’s hope we never see it duplicated.

Let’s figure out Rosario’s future when this demi-season is over. His bat has been heating up even as his utility has diminished. Amed is a suddenly outdated model of shortstop in the wake of the introduction of the all-new Andrés Giménez. Through little fault of his own, Rosario’s become a perfectly functional Ty Wigginton-type rendered obsolete, or at least superfluous, once a next-gen David Wright-caliber prospect rolls off the line fully loaded and ready to roar. Rosey maintains the talent that tantalized us, yet he’s been a young player coming along in fits and starts for four seasons. In real life, he’s still young. In baseball terms, he seems to be getting on a little. From the moment of his debut in 2017 through the end of 2019, Amed Rosario was the latest-born of all Mets ever, joining his family’s roster on November 20, 1995. Since this season commenced, we’ve had Mets born in 1996 (Ariel Jurado), 1997 (Ali Sanchez) and 1998 (precocious Giménez). Time flies when you’re on your way to getting picked off in Buffalo.

Speaking of Buffalo, before we memory-hole every good thing Wilson Ramos has ever done, up to and including an agile block of a pitch in the dirt Saturday night that probably nobody remembers in the wake of that ill-advised ninth-inning swing, congratulations to No. 40 once again on leading the Mets to that 18-1 win Friday night. Wilson homered, had three hits, reached base four times and drove in four runs. He would have totaled five RBIs, except in the ninth inning, with the 17-run lead appearing reasonably secure, Ramos’s deep fly to left with Jeff McNeil on third was not converted into a sacrifice fly. This was probably quaint baseball etiquette being exercised on the Mets’ part, but I’d like to think third base coach Gary DiSarcina was thinking, “It’s 18-1, and we’ve never won 18-1 before. We’ve won 19-1 before. Everybody knows that ‘did they win?’ story. Let’s do something new. I’m gonna hold the Squirrel right where he is.”

Whether or not Met lore was on our third base coach’s mind when he didn’t send McNeil, the effect was historymaking. By romping “only” 18-1, the Mets notched a Unicorn Score, a final tally by which the Mets have won ONCE and only ONCE. Like 19-1 in 1964, the Wrigley Field afternoon that gave us the cynic of legend calling a newspaper office and taking nothing for granted regarding the outcome. Like 24-4 in 2018 at Citizens Bank, the last time the Mets spawned a mythically singular triumphant digital creature. Each of the previous twenty-three Unicorn Scores in Mets history that has thus far gone uncloned was registered in a ballpark of that ilk: a place with an implied sense of MLB permanence. This one, at Sahlen Field, happened where the Mets will likely never play again after this series. And it included the first Met save credited for the questionably strenuous preservation of a lead of as many as 17 runs. Such a perfectly regulation save was assigned Friday to the ledger of the newest Met (No. 1,110), Erasmo Ramirez.

Erasmo indeed came on in relief, indeed went the final three and indeed didn’t surrender the inflated advantage he was assigned to protect. That’s a save in any season, even if nobody ever conceived of a Met reliever saving that large a lead. Way to go, Erasmo — if you’re gonna make history, you might as well make it count like nothing that’s ever been counted before.

If you’re gonna make a playoff run, you’d better make it real. With fourteen games to go, the Mets aren’t doing that. The 2020 Mets’ alleged playoff run is more chimera than unicorn, their would-be journey to the tourney less a winding road than a cul de sac. Win one or two, lose two or three, go round and round until there’s no point in calling what you’re doing getting anywhere. The Mets haven’t been getting anywhere and they’re running out of time to get anywhere. Hence, we might as well enjoy what skewed view there is before the sun sets beyond the eastern shore of Lake Erie.

Games in Buffalo. Extraordinarily safe saves. A pitcher forcing a runner at third using his feet and his wits. It’s baseball for now. It will do until it doesn’t.

by Jason Fry on 12 September 2020 10:08 am WHAM! BIFF! SOCK! OOF!

I’d been eager for a view of Sahlen Field, the highest-capacity Triple-A park in the U.S., which a generation ago was talked up as a ready-made big-league park for expansion. (It was also the first park built by the now-ubiquitous HOK, since renamed Populous.) Expansion never happened, but Sahlen is now a big-league park as the temporary home of the COVID-relocated Toronto Blue Jays.

Sahlen Field has a tangential link to the Mets, having been home to their Triple-A affiliate from 2009 through 2012. I don’t recall them ever playing an exhibition game there, not that it would have been televised in a summer in less desperate need of novelty than this one.

I didn’t get my view of Sahlen for a simple reason: I was driving. Friday was the day my kid restarted school in Massachusetts, complete with mandatory COVID test, lots and lots of health-awareness signs and a two-week quarantine to kick things off. We’ll see how that goes; for now, I spent the day hauling boxes out of storage and helping set up a dorm room. Driving back, I forgot the schedule and so tuned in to find the Mets down 1-0.

Typical, I thought, trying to remember which bad starting pitcher to invoke as lead-in to being mad at Brodie Van Wagenen and the Wilpons, father and failson.

But no, that run had actually been given up by Jacob deGrom, it was the top of the third, and the Mets were trying to make up the difference. Which they did within minutes, thanks to a drive to center from Michael Conforto. That made it 3-1, often enough for deGrom to perform his magic in relative safety, but the Blue Jays had arrived with their gloves on the wrong hands, and promptly gifted the Mets another run.

Next inning came the deluge — a 10-run inning, highlighted by Dominic Smith‘s grand slam, more Blue Jays fielding malfeasance, and a parade of hits. After that the only questions were if deGrom would be bothered by the half-hour breaks (no) or if a Blue Jay would actually injure himself not fielding a ball (also no, though it was a near thing).

Oh, and Erasmo Ramirez came in with a 15-run 13-run lead and recorded a save, because baseball. (It was just barely the most ridiculous such save of the week — the Braves’ Bryse Wilson came in with a 14-run lead on Wednesday and got one too.)

Before I moved to New York I drove fairly regularly, and baseball was always a welcome companion in the car, at least when radio reception allowed it to be one in the pre-digital era. (I used to spend weekend afternoons parked on the Virginia side of the Potomac River because I’d discovered that the water boosted WFAN’s signal enough to be heard during the day in D.C.) But of course you’re dependent on what kind of game you’re getting. I’ve driven through sloggy games in which the Mets can’t get out of their own way, and the effect can be to make you feel even more confined, like a Watchmen outtake in which it’s not clear who’s locked in with whom.

This was the opposite: I was late reporting for duty, the Mets apparently had been politely waiting for me, and once I arrived they delivered a (nighttime) daydream of insta-offense. Seriously, the 10-run inning began shortly before I pulled into a Sonic Drive-In and was still going on when I finished my burger and departed, and I realized with a start that Dom Smith’s grand slam had been part of that same doomed Blue Jays quest to get three outs, and not something that had happened during some previous hour or week.

It’s not always going to be like that, of course — you take your laughers when you can get them, and exponential laughers like Friday’s are strange visitations from the baseball gods that can only be marveled at. But as driving companions, I’ll take 18 runs and an almost-complete absence of peril any night the Mets feel like delivering those things. The miles shrank as the runs mounted; if only it were always so.

Though seriously guys — wouldn’t it have been better to score 18 runs behind one of the bad pitchers?

by Jason Fry on 11 September 2020 9:00 am Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

July 21, 2004 was a hot and sticky day in New York, with the temperature in the high 80s and a night that didn’t promise to be much more comfortable. The Mets were bumping along around .500, and kinda maybe sorta battling for a National League East lead that no team particularly seemed to want to claim. That night at Shea they were scheduled to play the Expos, who’d escaped contraction but been reduced to Major League Baseball’s wards and were widely expected to be moved out of Montreal as soon as it could be arranged.

None of those factors was particularly compelling, but I was going to game anyway, because the Mets had called up a third baseman billed as their brightest hitting prospect in years, a Virginia kid named David Wright. The Mets had drafted Wright as compensation for Mike Hampton becoming enamored of the schools in Colorado and Wright had torn up minor-league pitching, first at Binghamton and then at Norfolk. He had nothing left to prove down there; it was time to see what he could do under the bright lights.

I talked my friend Tim into going and secured seats behind home plate in the upper deck. They were the red seats, but boxes — not too far from the field and set apart from the upper reaches of Shea, which during sparsely attended games mostly belonged to smokers, drunks, and guys hoping to find someone to fight. My seat cost $23.

Wright fielded a grounder in the first, throwing across the diamond to Ty Wigginton, the man whose job he’d taken, to retire Jose Vidro. In the second he came to the plate for the first time in the big leagues. That first at-bat wasn’t what he’d hoped for during all those nights dreaming about what might be: he was retired on a pop-up in foul territory, with Expos catcher Brian Schneider making a nifty catch that ended with him flipped over the dugout railing. Wright made outs in his other three at-bats as well: a groundout, a pop to short and a fly ball to right. The Mets won by a single run.

Not a debut heavy on fireworks, but as Tim and I left Shea I made sure to tuck my ticket stub deeper in my pocket. When I got home, I filed it in a cubby of my desk instead of tossing it in with the recycling. Everything I’d heard and seen had convinced me that David Wright would be special.

And he was. That’s understating things rather dramatically. Wright quickly developed into a precocious hitter who was never out of an at-bat, combining a jeweler’s eye for the strike zone with superlative natural gifts and an indomitable work ethic. Within a couple of years, he’d become the face of the franchise, and I knew that one day I’d clear my calendar to see his final game, and then again to see the Mets retire his number 5. That number had belonged to some illustrious Mets over the years: Ed Charles wore it dancing near the mound as Jerry Koosman jackknifed into Jerry Grote‘s arms, Davey Johnson had it on his back while out-scheming Whitey Herzog and John McNamara and everyone else, and John Olerud had donned it as part of the Best Infield in Baseball. But all of that was in the past — 5 belonged to Wright now, and would never belong to any other New York Met. And he was. That’s understating things rather dramatically. Wright quickly developed into a precocious hitter who was never out of an at-bat, combining a jeweler’s eye for the strike zone with superlative natural gifts and an indomitable work ethic. Within a couple of years, he’d become the face of the franchise, and I knew that one day I’d clear my calendar to see his final game, and then again to see the Mets retire his number 5. That number had belonged to some illustrious Mets over the years: Ed Charles wore it dancing near the mound as Jerry Koosman jackknifed into Jerry Grote‘s arms, Davey Johnson had it on his back while out-scheming Whitey Herzog and John McNamara and everyone else, and John Olerud had donned it as part of the Best Infield in Baseball. But all of that was in the past — 5 belonged to Wright now, and would never belong to any other New York Met.

It was on Wright’s back for a lot of memories. There he was, willing a drive to center over the head of Johnny Damon at Shea. And drenched in champagne next to Jose Reyes, the other young star we became used to seeing to Wright’s left. It was on his back as he flew through the air one night in San Diego, coming down with a ball in his bare hand.

Not all of those memories were happy ones, of course. Wright wore 5 as the Mets shut down Shea in a sendoff turned funeral, and in a new park whose dimensions might as well have been engineered to undermine him as an offensive force. He was wearing it when he took a fastball to the head, left sprawling in the Citi Field dust, and when he returned but didn’t look quite the same.

He was wearing it in 2011, the year he represents in our series and a season that wasn’t particularly a happy one. The Mets finished 77-85; Wright spent a good chunk of the late spring and early summer on the DL, shelved by a stress fracture in his lower back that he’d incurred making a diving tag play at third in April. At the time it seemed like an acute malady, the kind of unfortunate injury Wright had incurred because he only knew how to play hard; later, as his body began to balk at commands and betray him, we’d see it as the beginning of the end. The injury caused calcium deposits that fueled the spinal stenosis that would eventually drive Wright from the field before his time, though genetics and the wear and tear of baseball also contributed.