The blog for Mets fans

who like to read

ABOUT US

Faith and Fear in Flushing made its debut on Feb. 16, 2005, the brainchild of two longtime friends and lifelong Met fans.

Greg Prince discovered the Mets when he was 6, during the magical summer of 1969. He is a Long Island-based writer, editor and communications consultant. Contact him here.

Jason Fry is a Brooklyn writer whose first memories include his mom leaping up and down cheering for Rusty Staub. Check out his other writing here.

Got something to say? Leave a comment, or email us at faithandfear@gmail.com. (Sorry, but we have no interest in ads, sponsored content or guest posts.)

Need our RSS feed? It's here.

Visit our Facebook page, or drop by the personal pages for Greg and Jason.

Or follow us on Twitter: Here's Greg, and here's Jason.

|

by Greg Prince on 14 September 2020 8:08 am The Mets shuffled off from Buffalo with one more loss than win for their weekend’s work and three fewer games remaining on their truncated schedule, thereby humbling their already modest postseason chances. Not that they were much to begin with, but sooner or later, you can take only so much comfort from relative proximity to a final playoff spot when you can’t string together more than a couple of wins at a time.

Sunday’s attempt to capture their series versus the Blue Jays dissipated quickly, as an onslaught of hits (8) against old nemesis Hyun-Jin Ryu produced a paucity of runs (1). Maybe there would have been more scoring early, but the mysteriously reappeared Todd Frazier ran the Mets out of their first-inning rally, and opportunities grew less plentiful from there. David Peterson returned to a more competent form than we last witnessed from the rookie — 5 IP, 3 H, 2 BB, 2 R — but the pieces refused to be put together overall. Relievers Brad Brach and Jared Hughes let the Jays do the walking, then the hitting. Toruffalo’s lead grew to an insurmountable 7-1 before settling in at a final of 7-3.

Despite dropping ten of their past sixteen contests, the Mets remain sorta, kinda in it. Five games under .500 with two weeks to go doesn’t necessarily disqualify you in 2020. It actually keeps you viable, just two games behind the least worst among the jumble of NL pretenders. Get hot, hope others in your lax bracket don’t and maybe you’ve got something there. Or as Leo McGarry once told Jed Bartlet, “Act as if ye have faith and faith shall be given to you. Put it another way, fake it till you make it.”

Sound like a plan? Not really. But it hasn’t stopped us from pinning our hopes on fragile bulletin boards before. It was only last September that we had no real chance at making the playoffs, yet we hung in with the illusion that we might for as long as we could. The sight of Ryu was a reminder of one of the high points derived from late 2019’s power of positive thinking. On this very date, September 14, Ryu of the Dodgers dueled deGrom of the Mets at Citi Field. It was indeed a genuine modern pitchers’ duel. Both aces went seven innings. Neither man gave up a run or a walk. Rajai Davis doubled with the bases loaded off Julio Urias to supply all the offense the Mets would get and need. The 3-0 win that Saturday night placed us three out of a Wild Card, statistically further than we are now from this year’s version of an October lottery ticket, but it felt a great deal more real. We had played for five-and-a-half months. We had a winning record. We had withstood Hyun-Jin Ryu.

It’s hard to believe I’m feeling nostalgic for an also-ran stretch run of incredibly recent vintage, but it felt real enough. The next night, an ESPN Sunday, had that do-or-die September quality to it. We didn’t quite do, losing in heartbreaking fashion to L.A., but we weren’t dead yet. Or maybe we were but refused to sign the death certificate. After being throttled in Colorado on Monday night, we were ready to call it a year. Then we won on Tuesday night, so we called it no such thing. And on Wednesday afternoon in Denver, when we came dramatically from behind to beat the Rockies once more, the race was as on as it could be. We were still three out and there even fewer games left with which to gain ground, but what’s the point of staying mathematically alive in September if you’re not going to milk it for all it’s worth?

The milking yielded little in the way of sustenance after Colorado. The Mets went to Cincinnati and didn’t sweep, which is what they pretty much had to do to maintain the contention illusion. After losing on Saturday afternoon to the Reds and slipping 4½ out with eight to play, Todd Frazier put on a brave face. “I felt like we had to go 9-1, so here’s our one,” he said. “Let’s roll from here.” The roll never came. The Mets were eliminated at home a few nights later.

During the early portion of this year’s Spring Training, before we knew nobody was training for anything, I saw Seth Lugo interviewed on SNY. Whatever he said didn’t stay with me. The image that accompanied his appearance, however, has lingered in my consciousness. It was a clip of Seth striking out a batter at Coors Field in that Wednesday afternoon game. It wasn’t identified by a graphic, but I recognized the situation. I recognized the shadows. September shadows. Pennant race shadows. The Mets’ chances didn’t exist beyond a shadow of a doubt, but the shadows knew they were still in it. Being still in it is its own triumph in September. That image of the shadows falling over home plate at Coors Field while Seth Lugo gave the Mets two innings to keep us incrementally alive kept me going as much as anything during baseball’s hiatus. Those shadows were where I wanted to get back to once baseball got back. Arrive alive at that juncture where the shadows encroach and keep rolling this time — if there was to be a “this time” in 2020.

This time isn’t much. There was a shadow over home plate not long after the 3:07 PM start in Buffalo on Sunday, but the minor league park there doesn’t have multiple tiers, so the effect of the shadow was negligible. As is the feeling that the Mets are still in it. Sometimes it seems the only commonality between the Mets of this September and last September is an overreliance on Todd Frazier.

by Greg Prince on 13 September 2020 1:16 pm In a sixty-game season whose primary appeal may be the encompassing of elements largely unprecedented, you pretty much have to be in it for those things you’ve never seen before. They may not add up to an orthodox major league campaign, let alone big-picture success, but they sure do get your attention.

Take a 1-unassisted at third base. Take it, frame it and hang it over the fireplace. Nobody seems to believe they’d ever seen one before Saturday night. Now we have. It was a beauty, for sure, executed by Seth Lugo out of sheer desperation. With runners on first and second in the home — which is to say Toronto in Buffalo — fourth, Vlad Guerrero, Jr., chops a ball to the left side. Lugo fields it. His momentum carries him toward third. His third baseman, J.D. Davis, has broken away from the bag, so all Lugo can do is race the baserunner from second, Travis Shaw, to third. The only way Seth can win the race is by sliding into the bag, which he does. He scurries, he slides and he gets the out. It was truly gorgeous, not to mention Amazin’.

It also goes down as one of those stirring defensive plays — Keith Hernandez stretching into foul territory like Gumby and creating a 3-1 forceout of Jose Cruz at first with Bobby Ojeda covering; Endy Chavez elevating to rob Scott Rolen over the left field wall and then firing to double Jim Edmonds off first in a certain NLCS game; Yoenis Cespedes setting off a throw as if from a cannon in center to nail and shock Sean Rodriguez at third — that occurs in service to a loss that can’t help but take the edge of the inherent enjoyment of the moment that took your breath away several innings before. Appreciation for its beauty may be hard to garner the next morning, but gosh, “what a play,” you’d have to say, no matter that everything else didn’t quite work out as a Mets fan might wish.

No, everything else did not work out Saturday night at Sahlen Field, speaking of largely unprecedented elements. The Mets absorbed their first-ever regular-season defeat in Buffalo a night after posting their first-ever regular-season victory in Buffalo amid their first-ever regular-season series in Buffalo. Pending the prevalence of viruses and the judgment of Canadian officials, we probably won’t be able to say, “the Mets are playing in Buffalo” ever again, so we might as well acknowledge the top-tier strangeness therein.

It’s been mentioned ad bisonem since the Toronto Blue Jays were motivated to temporarily make a home away from home out of the home of their Triple-A affiliate that New York State is currently if briefly home to three big league baseball clubs for the first time since 1957. Prior to the departure of the Giants and Dodgers, the “State” part of New York was implied. The last time Buffalo was big league in the baseball sense, the team was the Blues and the league was the Federal. The National League’s Buffalo Bisons stampeded from the scene following the 1885 season. Met notables from Ed Kranepool to Matt Harvey completed their finishing-school activities in Buffalo, but by then, the affiliation was decidedly minor. Buffalo tried to add an MLB franchise to its lineup of NFL Bills, NHL Sabres and (for a pre-Clippers spell) NBA Braves, but the effort never sufficiently impressed those who make expansion decisions. Roy Hobbs and the New York Knights played in Buffalo, but that was in the movies.

In 2020, with the Global Pandemic refusing to budge from leading every league in disruptiveness, it’s the Blue Jays hosting Eastern Division visitors from both leagues in not quite Ontario. On TV, it’s a good-looking park. Fresh, open-air, a pleasant antidote to the confining confines of the Rogers Centre. The fan experience is about the same as it is at Citi Field or any established venue. It’s empty as hell up there and the fans are noticeably flat, if cheeky in their presence. Gov. Cuomo claims a front-row perch in corrugated form. So does Geddy Lee.

The Met offense that scored 18 runs Friday night essentially also took a seat and sat by watching on Saturday night. Talk about flat. Nope, ya can’t save for tomorrow what you score today. For all the innovations shepherded into ad hoc existence by Rob Manfred, he has not allowed for the retroactive rejiggering of run stocks. Thus, two runs would have to do on Saturday for the Mets, and they didn’t do, as the Blue Jays scratched out three. Lugo looked good pitching as well as fielding, and the Met bullpen wasn’t particularly culpable, but the Mets didn’t make the most of their occasional opportunities versus former patsy Robbie Ray and his relief successors.

Perhaps I’m burying the twin ledes here: that Wilson Ramos didn’t come through at a crucial juncture and that Amed Rosario shut the books closed without allowing Howie Rose the chance to put a win in them. Perhaps you’d like to bury the instigators of those game-determining actions. I woke up Sunday morning so stoked by how well Seth Lugo executed his 1-unassisted and how novel the Sahlen setting was that I had nudged the worst of the Saturday night feebleness to a lesser level of my consciousness. I’m assuming neither Ramos nor Rosario has been unconditionally released since last night, nor have they been left by the side of the road out on the 190 beyond the center field fence, yet their respective misdeeds can’t be drenched in hot sauce like so many wings.

Yeah, I, too, was fuming that Ramos swung at a two-oh pitch after six consecutive balls had been issued by Toruffalo closer Rafael Dolis to start the ninth and proceeded to ground into the continent’s most unnecessary double play. And, yeah, Amed Rosario, having been given the gift of first base via a mishandled strike three on what the presumed final out of the ballgame didn’t have to return the favor by getting picked off for the definitive final out of the ballgame…though it was only defined as definitive once replay review took a look. Replay review did a lot of looking Saturday night. The crew in Chelsea was called on six separate times to intensely examine on-field yeas or nays from Sahlen. The last of their requested interventions, the one that ultimately ended Rosario’s otherwise splendid night (3-for-3 plus the heads-up dash to first base on strike three), reversed an umpire’s ruling that said Amed didn’t get picked off.

Was a game-losing pickoff another first for the Mets annals? I’m not sure, but I can’t remember another. I know the Mets once won a game when Frankie Rodriguez turned and flung to Ruben Tejada to pick Roger Bernadina off second. I know a World Series game was once ended on a pickoff play at first, but that forehead-slapper (Koji Uehara removing Kolten Wong in 2013) didn’t involve the Mets. Let’s say this particular result was unprecedented. Let’s hope we never see it duplicated.

Let’s figure out Rosario’s future when this demi-season is over. His bat has been heating up even as his utility has diminished. Amed is a suddenly outdated model of shortstop in the wake of the introduction of the all-new Andrés Giménez. Through little fault of his own, Rosario’s become a perfectly functional Ty Wigginton-type rendered obsolete, or at least superfluous, once a next-gen David Wright-caliber prospect rolls off the line fully loaded and ready to roar. Rosey maintains the talent that tantalized us, yet he’s been a young player coming along in fits and starts for four seasons. In real life, he’s still young. In baseball terms, he seems to be getting on a little. From the moment of his debut in 2017 through the end of 2019, Amed Rosario was the latest-born of all Mets ever, joining his family’s roster on November 20, 1995. Since this season commenced, we’ve had Mets born in 1996 (Ariel Jurado), 1997 (Ali Sanchez) and 1998 (precocious Giménez). Time flies when you’re on your way to getting picked off in Buffalo.

Speaking of Buffalo, before we memory-hole every good thing Wilson Ramos has ever done, up to and including an agile block of a pitch in the dirt Saturday night that probably nobody remembers in the wake of that ill-advised ninth-inning swing, congratulations to No. 40 once again on leading the Mets to that 18-1 win Friday night. Wilson homered, had three hits, reached base four times and drove in four runs. He would have totaled five RBIs, except in the ninth inning, with the 17-run lead appearing reasonably secure, Ramos’s deep fly to left with Jeff McNeil on third was not converted into a sacrifice fly. This was probably quaint baseball etiquette being exercised on the Mets’ part, but I’d like to think third base coach Gary DiSarcina was thinking, “It’s 18-1, and we’ve never won 18-1 before. We’ve won 19-1 before. Everybody knows that ‘did they win?’ story. Let’s do something new. I’m gonna hold the Squirrel right where he is.”

Whether or not Met lore was on our third base coach’s mind when he didn’t send McNeil, the effect was historymaking. By romping “only” 18-1, the Mets notched a Unicorn Score, a final tally by which the Mets have won ONCE and only ONCE. Like 19-1 in 1964, the Wrigley Field afternoon that gave us the cynic of legend calling a newspaper office and taking nothing for granted regarding the outcome. Like 24-4 in 2018 at Citizens Bank, the last time the Mets spawned a mythically singular triumphant digital creature. Each of the previous twenty-three Unicorn Scores in Mets history that has thus far gone uncloned was registered in a ballpark of that ilk: a place with an implied sense of MLB permanence. This one, at Sahlen Field, happened where the Mets will likely never play again after this series. And it included the first Met save credited for the questionably strenuous preservation of a lead of as many as 17 runs. Such a perfectly regulation save was assigned Friday to the ledger of the newest Met (No. 1,110), Erasmo Ramirez.

Erasmo indeed came on in relief, indeed went the final three and indeed didn’t surrender the inflated advantage he was assigned to protect. That’s a save in any season, even if nobody ever conceived of a Met reliever saving that large a lead. Way to go, Erasmo — if you’re gonna make history, you might as well make it count like nothing that’s ever been counted before.

If you’re gonna make a playoff run, you’d better make it real. With fourteen games to go, the Mets aren’t doing that. The 2020 Mets’ alleged playoff run is more chimera than unicorn, their would-be journey to the tourney less a winding road than a cul de sac. Win one or two, lose two or three, go round and round until there’s no point in calling what you’re doing getting anywhere. The Mets haven’t been getting anywhere and they’re running out of time to get anywhere. Hence, we might as well enjoy what skewed view there is before the sun sets beyond the eastern shore of Lake Erie.

Games in Buffalo. Extraordinarily safe saves. A pitcher forcing a runner at third using his feet and his wits. It’s baseball for now. It will do until it doesn’t.

by Jason Fry on 12 September 2020 10:08 am WHAM! BIFF! SOCK! OOF!

I’d been eager for a view of Sahlen Field, the highest-capacity Triple-A park in the U.S., which a generation ago was talked up as a ready-made big-league park for expansion. (It was also the first park built by the now-ubiquitous HOK, since renamed Populous.) Expansion never happened, but Sahlen is now a big-league park as the temporary home of the COVID-relocated Toronto Blue Jays.

Sahlen Field has a tangential link to the Mets, having been home to their Triple-A affiliate from 2009 through 2012. I don’t recall them ever playing an exhibition game there, not that it would have been televised in a summer in less desperate need of novelty than this one.

I didn’t get my view of Sahlen for a simple reason: I was driving. Friday was the day my kid restarted school in Massachusetts, complete with mandatory COVID test, lots and lots of health-awareness signs and a two-week quarantine to kick things off. We’ll see how that goes; for now, I spent the day hauling boxes out of storage and helping set up a dorm room. Driving back, I forgot the schedule and so tuned in to find the Mets down 1-0.

Typical, I thought, trying to remember which bad starting pitcher to invoke as lead-in to being mad at Brodie Van Wagenen and the Wilpons, father and failson.

But no, that run had actually been given up by Jacob deGrom, it was the top of the third, and the Mets were trying to make up the difference. Which they did within minutes, thanks to a drive to center from Michael Conforto. That made it 3-1, often enough for deGrom to perform his magic in relative safety, but the Blue Jays had arrived with their gloves on the wrong hands, and promptly gifted the Mets another run.

Next inning came the deluge — a 10-run inning, highlighted by Dominic Smith‘s grand slam, more Blue Jays fielding malfeasance, and a parade of hits. After that the only questions were if deGrom would be bothered by the half-hour breaks (no) or if a Blue Jay would actually injure himself not fielding a ball (also no, though it was a near thing).

Oh, and Erasmo Ramirez came in with a 15-run 13-run lead and recorded a save, because baseball. (It was just barely the most ridiculous such save of the week — the Braves’ Bryse Wilson came in with a 14-run lead on Wednesday and got one too.)

Before I moved to New York I drove fairly regularly, and baseball was always a welcome companion in the car, at least when radio reception allowed it to be one in the pre-digital era. (I used to spend weekend afternoons parked on the Virginia side of the Potomac River because I’d discovered that the water boosted WFAN’s signal enough to be heard during the day in D.C.) But of course you’re dependent on what kind of game you’re getting. I’ve driven through sloggy games in which the Mets can’t get out of their own way, and the effect can be to make you feel even more confined, like a Watchmen outtake in which it’s not clear who’s locked in with whom.

This was the opposite: I was late reporting for duty, the Mets apparently had been politely waiting for me, and once I arrived they delivered a (nighttime) daydream of insta-offense. Seriously, the 10-run inning began shortly before I pulled into a Sonic Drive-In and was still going on when I finished my burger and departed, and I realized with a start that Dom Smith’s grand slam had been part of that same doomed Blue Jays quest to get three outs, and not something that had happened during some previous hour or week.

It’s not always going to be like that, of course — you take your laughers when you can get them, and exponential laughers like Friday’s are strange visitations from the baseball gods that can only be marveled at. But as driving companions, I’ll take 18 runs and an almost-complete absence of peril any night the Mets feel like delivering those things. The miles shrank as the runs mounted; if only it were always so.

Though seriously guys — wouldn’t it have been better to score 18 runs behind one of the bad pitchers?

by Jason Fry on 11 September 2020 9:00 am Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

July 21, 2004 was a hot and sticky day in New York, with the temperature in the high 80s and a night that didn’t promise to be much more comfortable. The Mets were bumping along around .500, and kinda maybe sorta battling for a National League East lead that no team particularly seemed to want to claim. That night at Shea they were scheduled to play the Expos, who’d escaped contraction but been reduced to Major League Baseball’s wards and were widely expected to be moved out of Montreal as soon as it could be arranged.

None of those factors was particularly compelling, but I was going to game anyway, because the Mets had called up a third baseman billed as their brightest hitting prospect in years, a Virginia kid named David Wright. The Mets had drafted Wright as compensation for Mike Hampton becoming enamored of the schools in Colorado and Wright had torn up minor-league pitching, first at Binghamton and then at Norfolk. He had nothing left to prove down there; it was time to see what he could do under the bright lights.

I talked my friend Tim into going and secured seats behind home plate in the upper deck. They were the red seats, but boxes — not too far from the field and set apart from the upper reaches of Shea, which during sparsely attended games mostly belonged to smokers, drunks, and guys hoping to find someone to fight. My seat cost $23.

Wright fielded a grounder in the first, throwing across the diamond to Ty Wigginton, the man whose job he’d taken, to retire Jose Vidro. In the second he came to the plate for the first time in the big leagues. That first at-bat wasn’t what he’d hoped for during all those nights dreaming about what might be: he was retired on a pop-up in foul territory, with Expos catcher Brian Schneider making a nifty catch that ended with him flipped over the dugout railing. Wright made outs in his other three at-bats as well: a groundout, a pop to short and a fly ball to right. The Mets won by a single run.

Not a debut heavy on fireworks, but as Tim and I left Shea I made sure to tuck my ticket stub deeper in my pocket. When I got home, I filed it in a cubby of my desk instead of tossing it in with the recycling. Everything I’d heard and seen had convinced me that David Wright would be special.

And he was. That’s understating things rather dramatically. Wright quickly developed into a precocious hitter who was never out of an at-bat, combining a jeweler’s eye for the strike zone with superlative natural gifts and an indomitable work ethic. Within a couple of years, he’d become the face of the franchise, and I knew that one day I’d clear my calendar to see his final game, and then again to see the Mets retire his number 5. That number had belonged to some illustrious Mets over the years: Ed Charles wore it dancing near the mound as Jerry Koosman jackknifed into Jerry Grote‘s arms, Davey Johnson had it on his back while out-scheming Whitey Herzog and John McNamara and everyone else, and John Olerud had donned it as part of the Best Infield in Baseball. But all of that was in the past — 5 belonged to Wright now, and would never belong to any other New York Met. And he was. That’s understating things rather dramatically. Wright quickly developed into a precocious hitter who was never out of an at-bat, combining a jeweler’s eye for the strike zone with superlative natural gifts and an indomitable work ethic. Within a couple of years, he’d become the face of the franchise, and I knew that one day I’d clear my calendar to see his final game, and then again to see the Mets retire his number 5. That number had belonged to some illustrious Mets over the years: Ed Charles wore it dancing near the mound as Jerry Koosman jackknifed into Jerry Grote‘s arms, Davey Johnson had it on his back while out-scheming Whitey Herzog and John McNamara and everyone else, and John Olerud had donned it as part of the Best Infield in Baseball. But all of that was in the past — 5 belonged to Wright now, and would never belong to any other New York Met.

It was on Wright’s back for a lot of memories. There he was, willing a drive to center over the head of Johnny Damon at Shea. And drenched in champagne next to Jose Reyes, the other young star we became used to seeing to Wright’s left. It was on his back as he flew through the air one night in San Diego, coming down with a ball in his bare hand.

Not all of those memories were happy ones, of course. Wright wore 5 as the Mets shut down Shea in a sendoff turned funeral, and in a new park whose dimensions might as well have been engineered to undermine him as an offensive force. He was wearing it when he took a fastball to the head, left sprawling in the Citi Field dust, and when he returned but didn’t look quite the same.

He was wearing it in 2011, the year he represents in our series and a season that wasn’t particularly a happy one. The Mets finished 77-85; Wright spent a good chunk of the late spring and early summer on the DL, shelved by a stress fracture in his lower back that he’d incurred making a diving tag play at third in April. At the time it seemed like an acute malady, the kind of unfortunate injury Wright had incurred because he only knew how to play hard; later, as his body began to balk at commands and betray him, we’d see it as the beginning of the end. The injury caused calcium deposits that fueled the spinal stenosis that would eventually drive Wright from the field before his time, though genetics and the wear and tear of baseball also contributed.

But if that was the beginning of Wright’s slide into autumn, there were some wonderful summer moments along the way. Like the 2013 World Baseball Classic, where he lit up the spring stage and claimed the nickname Captain America for himself. The nickname was a perfect fit, one that lent even Wright’s rare moments of pique a sheen of heroism. Take poor umpire Toby Basner, who ejected Wright the next year and was preserved for eternity glaring over at the dugout as Wright informed him that “you’re the worst.” Can you imagine Captain America himself telling you you’re bad at your job in front of the country and God and everybody? I’m still a little surprised that Basner didn’t disperse into a bashful pink mist out of sheer embarrassment.

And then there was 2015. Wright went on the DL in mid-April with what was thought to be a hamstring strain; while he was out, the spinal stenosis was diagnosed. He wouldn’t return until late August, but when he did it was with an exclamation mark of a moment, homering into Citizens Bank Park’s upper deck on the third pitch he saw. There was the moment a couple of weeks later when Wright crossed the plate in D.C. a hair before the tag, popping up to declare himself safe and flinging his fist out in exultation once the good news was confirmed. He was front and center that fall as the Mets slipped past the Dodgers in Chavez Ravine, obliterated the Cubs at Wrigley, and christened Citi Field as a World Series venue with a home run. And then there was 2015. Wright went on the DL in mid-April with what was thought to be a hamstring strain; while he was out, the spinal stenosis was diagnosed. He wouldn’t return until late August, but when he did it was with an exclamation mark of a moment, homering into Citizens Bank Park’s upper deck on the third pitch he saw. There was the moment a couple of weeks later when Wright crossed the plate in D.C. a hair before the tag, popping up to declare himself safe and flinging his fist out in exultation once the good news was confirmed. He was front and center that fall as the Mets slipped past the Dodgers in Chavez Ravine, obliterated the Cubs at Wrigley, and christened Citi Field as a World Series venue with a home run.

Yeah, he was special all right — off the field as well as on. We heard innumerable stories about Wright’s kindness and fundamental decency, and for every one we learned about we knew that there were two or three more that had remained private. There was Max Rubin, the kid with Down Syndrome who asked Wright to hit a home run against the Yankees. David replied “I’ll try,” and then did just that … but that’s not the story. The story is that after the game Max gathered Wright up in a hug, radiant with happiness, and then the camera pulled back to show that Wright’s smile was even bigger.

Or there was the story that was my favorite, because it was such a small thing: an affectionate portrait of Jay Horwitz revealed that the Mets PR legend had chronic trouble with email addresses, and his careless autocompletes meant Wright routinely got messages intended for a Horwitz colleague with a similar email address. All of which Wright dutifully redirected to where they belonged. What multimillionaire athlete does that? Heck, you probably have someone in your office who doesn’t care enough to do that.

In May 2016, spinal stenosis drove Wright from the game he loved. The rest of the year passed without him. So did all of 2017. 2018 began without him; the days got longer and then shorter with no sign of him in blue and orange. Every so often we’d get an update, and each one was grim: a surgery, a period of enforced inactivity, all of them accompanied by Wright insisting that this was not the end and he was optimistic. We learned how hard he worked to fight his body to a draw, becoming the Job of baseball. And though we’d learned never to bet against him, we all sensed that there were some obstacles not even Captain America could overcome.

And so, simultaneously cruelly and mercifully, an endgame was crafted — a pair of cameos at the end of September by way of orchestrated farewell. The Saturday night game on Sept. 29, 2018 became a sellout within a couple of hours of the announcement. The date I’d imagined as part of some distant hazy future — often I’d pictured it including my son Joshua, impossibly grown up and playing hooky from college — had arrived, far earlier than it should have and with a fair amount of bitter mixed in with the sweet.

I knew I had to be there. I’d been there at the beginning, after all. And after David Wright had brought me so much joy, how couldn’t I be there at the end?

As it happened, my companion wasn’t Joshua but Emily. We arrived nearly an hour before game time and found ourselves amid throngs of people wearing WRIGHT 5 shirts, some of them carrying placards — to use a term I’ve only ever heard used by flight attendants and Casey Stengel — expressing thanks, love and devotion.

We watched from the Promenade as Wright’s pregame gamboling in the outfield drew standing ovations and as he scooped up a first pitch from his daughter Olivia Shea before scooping her up as well. We stood and yelled and clapped as he ran out to his position alone, then was joined by his teammates. We looked at the big screen to see the joy on his face and that of Reyes as the two embraced — my feelings about Reyes were complicated by then, to say the least, but Wright’s happiness at playing beside his friend was genuine and impossible to resist. We rose again as Wright came to the plate for this first at-bat, and marveled at the patience he showed in working out a walk. We cheered madly when he fielded a grounder and threw sidearm for a putout at first. And there we were on our feet again when he led off in the fourth.

The second pitch from Miami’s Trevor Richards was a high fastball; Wright swung and popped it up outside first. I tried to will it into the seats. So did 44,000 other people. It was not to be — the ball came down in Peter O’Brien‘s glove. Wright smiled a little sheepishly, though you could see he was ticked, and headed for the dugout.

He was back at his position for the top of the fifth, and I let myself dream. I imagined that after the foul out he’d told Mickey Callaway that he was moving around fine out there and Mickey had asked him if he wanted one more at-bat. I didn’t need to wonder what the answer would have been. So I was reluctant — unwilling, almost — to register that Callaway had left the dugout and stopped near home to speak with the umpire.

That had been the plan, and there would be no reprieve. Wright hugged his teammates and waved, while the Mets and Marlins both clapped, and then he vanished into the dugout. And I realized what had pierced me most deeply that night wasn’t the highlights of heroic days, but the tiny little things that would never make a YouTube clip.

I could queue up Wright scoring in Washington or homering in Philadelphia whenever I wanted. But it would be harder to find a recording of all his little mannerisms, which I’d committed to memory years ago and could recognize even from a distant vantage point. The way he came in on a grounder, eyeing it like it was prey, or scuffed the dirt near third with his feet in a bit of nervous, meticulous grooming. The way he’d reseal his batting gloves before arriving at the plate, then raise his bat like a knight with a broadsword, exhale deeply, and get to work. Even the way he’d loosen up in the outfield before the game started, arms swinging and feet shuffling. Those were the things that crushed me on that last night — instantly recognizable tics and tells I’d seen a thousand times, come to take for granted, and realized I would never see again. I could queue up Wright scoring in Washington or homering in Philadelphia whenever I wanted. But it would be harder to find a recording of all his little mannerisms, which I’d committed to memory years ago and could recognize even from a distant vantage point. The way he came in on a grounder, eyeing it like it was prey, or scuffed the dirt near third with his feet in a bit of nervous, meticulous grooming. The way he’d reseal his batting gloves before arriving at the plate, then raise his bat like a knight with a broadsword, exhale deeply, and get to work. Even the way he’d loosen up in the outfield before the game started, arms swinging and feet shuffling. Those were the things that crushed me on that last night — instantly recognizable tics and tells I’d seen a thousand times, come to take for granted, and realized I would never see again.

Wright left the field as planned, and the Mets and Marlins played on and on and on, a scoreless game that ground along in low gear. (Eventually the Mets won by a single run.) After a video tribute, Wright himself returned for a few words. He was impeccably gracious, of course — thanking all of us for coming out to thank him. He was competitive, of course — his first words were satisfaction that his team had won. And best of all, he seemed at peace with an ending he had fought so hard to avoid.

And then he went back into the dugout, followed by the camera. Looking from the big board to the field, I could just spot the white square of his jersey, then a bit of his shoulder. I looked back at the video board and there he was, making his way down the dugout, until he reached the steps, and then he was gone. He was gone and it was time to go home.

Wright’s final at-bat wasn’t what he’d hoped for during all those days of grueling rehab work in St. Lucie: he was retired on a pop-up in foul territory. But everything that came before, between that hot July night back in 2004 and that cool September evening in 2018? It was special. That’s understating things rather dramatically. And as Emily and I left Citi Field, beneath the glow of fireworks, I made sure to tuck my printed ticket deeper into my pocket.

(For those keeping score at home, yes, this is a minor rewrite of the original farewell.)

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1965: Ron Swoboda

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1967: Al Schmelz

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1971: Tom Seaver

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

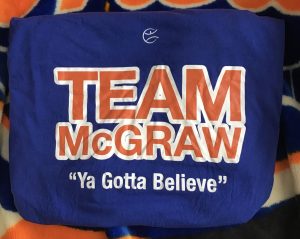

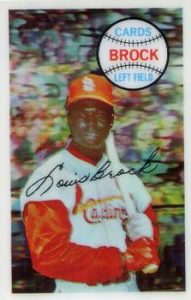

1974: Tug McGraw

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1986: Keith Hernandez

1988: Gary Carter

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2007: Jose Reyes

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2010: Ike Davis

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2019: Dom Smith

by Greg Prince on 10 September 2020 8:18 am They’re messing with us, right? The Mets getting us to take them semi-seriously for another day is part of a larger prank, right? They look moribund half the time. They give up late-inning leads the other half. They play in a depressing cartoon atmosphere where balls travel a thousand feet and the fans in the stands, who never move and never emote, appear as if painted by Hanna-Barbera. They have one starting pitcher, one former starting pitcher turned former reliever, and after that, per Dom DeLuise’s short-lived sitcom, it’s Lotsa Luck.

This is what they’re putting out there as a playoff contender of sorts in September? This is what gets somebody like Jake Marisnick, who helped the Houston Astros win Rob Manfred’s memorial piece of tin in 2017, to say, “this team’s too good to not make the playoffs”? He said that two nights ago, after the Mets were blitzed by the Orioles, 11-2, the day after the Mets coughed up a comeback to the Phillies, 9-8. The 2020 Mets remind me of what Whitey Herzog said about the Mets coming into 1986 off a pair of bridesmaid finishes: “They think they won the last two years, anyway.”

The Mets haven’t lacked for outward displays of confidence. They’ve lacked for wins. They haven’t won more than they’ve lost since this delayed season was less than a week old. They frustrate us. They irritate us. They let us down more than they lift us up.

Then, as on Wednesday night at perpetually vacant Citi Field, they mess with us. They fall behind by what seems like a hundred runs early, except it’s only four, and they come back — and this time they come back without giving up what they came back to get. They catch balls they’re nowhere near, they make dazzling throws from distant precincts, they launch moon shots at will and, just as amazingly, Edwin Diaz gets three outs without giving up a single run.

In the end, behind Michael Conforto, who is hitting .340, perfecting running basket catches and would be hearing serenades of “M-V-P!” if serenaders were allowed in attendance; behind Jeff McNeil, who is hitting .315 and has left the Squirrely doldrums of August in the dust; behind Andrés Giménez and Luis Guillorme, who’ve got gloves and know how to use them; behind Pete Alonso, who breaks ties as deftly as he assigns nicknames (Conforto is now Silky Elk); and, well, behind everybody not named Rick Porcello, the Mets won in scintillating fashion, 7-6, after trailing by scores of 5-1 and 6-3 to a Baltimore bunch that poured on waves of offense yet somehow kept getting hung out to dry. The Orioles pounded 14 hits and left 13 runners on base. Didn’t we used to do that?

Maybe we still do. Maybe we just didn’t for one night. We do enough things right and scintillate in encouraging proportions so that we find us believing in us, which is what we chronically do in September if given any reason at all. If you can remember as far back to last September (it was the one that had people in the stands), we were both never exactly in it yet never fully out of it until mathematical elimination tapped us on the shoulder (which nobody is allowed to do anybody anymore), thus we took ourselves — the Mets, that is — semi-seriously and then some.

Right now, if you’ve bothered to examine the standings, we’re not exactly in it, but we’re not fully out of it. We’re a little less fully out of it today because we were never completely out of it last night. This condition doesn’t demand to be taken seriously as contention. This condition demands to be taken seriously by a therapist.

They’re messing with us, right? Mess with us again like that real soon.

by Jason Fry on 9 September 2020 10:30 am Re Tuesday’s game: Blah blah blah Michael Wacha blah blah blah Orioles blah blah Robert Gsellman blah blah blah blah blah blah five games under .500 blah blah blah blah blah sinking fast.

I could have expanded that to 800 words, but why? Here’s the only analysis that matters: The Mets have 30 percent of a starting pitching staff. Jacob deGrom is Jacob deGrom, whose only flaw is he can’t start the other 80 percent of his team’s games. Seth Lugo is a solid starting pitcher who’s still ramping up to the pitch count demanded, and with a bad elbow. David Peterson is learning to navigate his first big-league season. Steven Matz has disintegrated and vanished. Wacha and Rick Porcello have struggled to pitch around the giant forks sticking out of their backs. Meanwhile, Noah Syndergaard‘s UCL exploded, Marcus Stroman opted out and Zack Wheeler was allowed to go to Philadelphia with no resistance from the Mets, unless catty quotes to beat reporters count.

In a given five-day stretch the Mets can count on a reliable start the first day, hope for one the second day, hold their breath the third day, and on the fourth and fifth days they brace for impact the moment the starter makes contact with the rubber. That’s a fatal flaw for any baseball team with contending hopes in a normal season and it sure looks like an equally fatal one in this weirdo season. Which makes sense: two hoary pieces of baseball wisdom hold that you never have enough starting pitching and momentum is the next day’s starter. Both of those have been proved correct repeatedly this year, beginning with the Mets surveying their wrecked rotation and carrying through with the Mets’ inability to get on any kind of a roll, largely because they’re down by three or four runs before the fifth inning more often than not.

Baseball teams can tinker around the margins and fix stuff, but there aren’t enough shovels to fill a crater in the middle of a starting rotation. You can’t patchwork enough relief to fix it, you can’t reliably outhit it, and no number of socially distanced team meetings, overturned Zoom cameras or lineup tweaks will make it go away. Which means that every other problem, ultimately, is just so much blah blah blah.

by Greg Prince on 8 September 2020 5:33 pm Welcome to A Met for All Seasons, a series in which we consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

Keep on searching now

Got to look up

Don’t look down

Keep the faith

—Little Richard

As baseball’s Winter Meetings approached in 1974, the Mets’ new general manager, Joe McDonald, drew some attention when he told reporters that he’d be aggressive in the trade market and that the only players he would consider “untouchable” were his big three starting pitchers: Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman and Jon Matlack. I guess it was a newsworthy enough statement that my sixth-grade teacher incorporated the anecdote into an upcoming vocabulary lesson.

“The Mets said they have only three ‘untouchable’ players,” Mr. Schneider told us. “Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman and Tug McGraw.”

On one hand, I was delighted that the Mets had broken through the elementary school wall and had become part of our curriculum. On the other, Mr. Schneider’s inaccuracy played like fingernails on our blackboard to my ears. Clearly Mr. Schneider had read the same article I had. Mr. Schneider was a prototypical cool teacher; a year later, Gabe Kaplan would play a version of him on television. But c’mon, Mr. S., get your facts straight.

In our casual open classroom atmosphere, I didn’t bother raising my hand. I just called out, “Jon Matlack, not Tug McGraw.” I did that a couple of times. Mr. Schneider ignored me. His point was his point, whatever it was. The implication, however, is what stays with me to this day. Tug McGraw seemed untouchable because the idea of the Mets trading Tug McGraw seemed unimaginable.

Yet on December 3, 1974, Tug McGraw proved touchable. McDonald and the Mets traded him.

It’s still unimaginable.

Three years after the Original Mets made their unique impression, along came a man who could only be termed the Met original. Within the realm of “there’s nobody like him,” there was nobody like Tug McGraw — not playing for this franchise in the 1960s and 1970s, not doing anything for anybody anywhere, probably. Amid a stream of characters who’ve defined what’s it meant to be Mets, Tug stands out as one of a kind.

He was a goof.

He was a wit.

He had a soul which often came to the fore

He had a heart which he inevitably wore on his sleeve.

He mastered a pitch few threw.

He coined a phrase everybody knew.

He was Tug McGraw.

Of the Mets.

And the Mets traded him.

In December of 1974, if you could pull yourself back from remembering who he was, you could imagine it. Except you couldn’t pull yourself back from remembering who he was. You couldn’t imagine doing that. Why would you? A thirty-year-old reliever coming off a dismal season after having been not so hot most (but not all) of the previous season, especially if you could fill a couple of holes by trading him…him you’d trade.

But if his name was Tug McGraw, and he’d been Tug McGraw of the Mets for nearly a decade and you understood what that had meant on the field, off the field and to the fans?

What the hell? They traded Tug McGraw?

I graduated sixth grade more than 45 years ago. I still haven’t solved the emotional equation that allowed for the trade of the pitcher who wore No. 45.

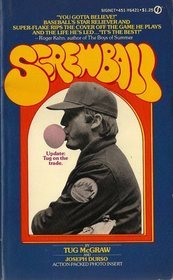

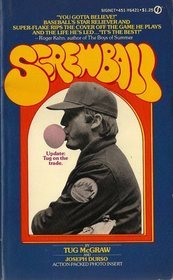

***Above all else, Tug McGraw came with a user’s manual. Not at first, but, for me, just after the Mets could use him. It was called Screwball. What Catcher in the Rye was for so many, Screwball was for me. It was the book that told me, at the transitional age of twelve, that I wasn’t the only one like that. It was the book that told me it was all right to feel a little off. Screwball showed me screwing up isn’t fatal. Maybe it gave me a little too much carte blanche to try it. As adolescence overcame me, I kind of got used to screwing up.

A book almost as good as the pitcher pictured. I didn’t read Screwball until it was out in paperback, which wasn’t released until the co-author (McGraw wrote it with Joe Durso) was no longer wearing the outfit he modeled on the cover. The cover, in fact, promised that in this edition we’d get “Tug on the trade.” That covered just a couple of pages up front. The rest was what was published following the 1973 season, when it was concluded that people would want to read what some lefty relief pitcher had to say about his life and everything around him. Following the 1973 season and postseason, Tug was a figure of immense public interest.

We’d been into Tug one way or another since a 20-year-old southpaw from somewhere in California showed up in St. Petersburg and introduced himself to Casey Stengel. The Mets were making room for myriad young arms in New York. None of them was lifting the 1965 Mets from the cellar. One of them, however, beat Sandy Koufax. Tug took his lumps plenty before August 26, before doing his first version of the unbelievable. Koufax, the premier pitcher of his generation and perhaps his century, had defeated the Mets thirteen times since 1962. The Mets had defeated him never. Given that one entity was at his peak and the other was permanently in the pits, who could possibly reverse the pattern?

Frank Edwin McGraw, Jr., that’s who. Not that anybody ever called Tug that except to let you know he wasn’t technically a born Tug. Almost born that way, but not quite. According to Screwball, Frank became Tug based on his behavior when “my mother used to nurse me when I was a baby and it was chow time. I guess she began calling me her little Tugger, and as time went by, everybody began using that name. While I was growing up, that’s what I thought my name really was.”

Tug followed his older brother Hank (Frank, Hank; it could get very confusing among the McGraws) into sports, then into baseball, then to the Mets. Hank never made it out of the minor leagues. Tug got his big break in 1965 when the Mets attempted to portray their Youth of America as in full bloom, regardless of their individual states of readiness. Sixteen of 43 players used that year were 23 or younger when the calendar flipped to ’65; ten of them were making their major league debut that year. One of them, Greg Goossen, was destined to go down in baseball history as the crux of one of Stengel’s best and last lines, said to have gone something like this:

“And we’ve got this kid who’s twenty who in ten years has a chance to be thirty.”

Except Greg wasn’t even twenty yet. Goossen made his MLB debut at 19. Jim Bethke and Kevin Collins commenced playing in the big leagues in 1965 at 18. Tug, a little more than two months the senior of veritable veteran Ed Kranepool, was an old man of 20 when Casey handed him the ball in the eighth inning at still-spanking new Shea Stadium on April 18. Relieving Jack Fisher, who had relieved Al Jackson, Tug McGraw entered his name in the Met annals by striking out Orlando Cepeda with the bases full of San Francisco Giants. “I jumped up in the air and started walking around like we’d just won the World Series or something,” he’d recall. Except that was only the second out of the inning. After retiring opposing pitcher Bob Shaw to fully escape the jam, Tug was literally shaking. Trainer Gus Mauch handed him a couple of tranquilizers.

The real excitement came four months later, McGraw vs. Koufax, Tug having been assigned to the starting rotation by Stengel’s successor Wes Westrum only recently. When that one went final in favor of the Mets, “I started jumping up and down when it ended, going crazy as usual, but this time the rest of the guys didn’t shake their heads or anything, and nobody went around the locker room saying McGraw’s some strange cat.”

He was, though, in the best sense possible. When I read Screwball, I realized conformity was overrated and that sedation wasn’t necessarily advisable. McGraw didn’t turn 21 until a few days after beating Koufax, though he didn’t have a straight line to success in front of him directly thereafter. Tug’s rookie year yielded a 2-7 record. Beating Sandy Koufax came four days prior to his 21st birthday and four days after his first win. The decisions would pile up in September in the wrong direction. Then came a detour into the Marine Corps to fulfill his service obligations. The USMC wasn’t exactly Tug’s bag.

Tug’s baseball career didn’t march in formation for the next three seasons. He experienced injuries. He experienced setbacks. Besting Koufax made for a great trivia question, but by 1968, there wasn’t a whole lot else to his CV. The lefty was studying barbering in case baseball wasn’t a long-term bet. The new manager, a Marine vet named Gil Hodges, sent him to Triple-A Jacksonville in hopes the now 23-year-old — married to a lady named Phyllis, taking care of a pooch named Pucci, and honing a pitch he referred to as a screwjie — would come down with a case of latent maturity.

In 1969, Hodges found room in his bullpen for an older and reasonably wiser McGraw, and McGraw contributed substantially to what was about to become known as a Miracle. It was the dawn of an era when a good relief pitcher was understood to be something more than a failed starter. Tug thrived in the later innings, or whenever Hodges decided he needed Tug. In 1969, when the likes of Seaver, Koosman and Gentry weren’t finishing everything they started, McGraw relieved 38 times, posting eight wins from the pen along with a dozen saves. Tug didn’t get into any of the games versus Atlanta or Baltimore in the postseason, but as lefty partner to righty Ron Taylor (9 W, 13 S), he provided an extra measure of certainty that the Mets would get there.

Plus his teammates appreciated him. Consider Art Shamsky in 2020 reflecting on what he remembered from playing behind and being around Tug McGraw some 50 years earlier (I asked Art about Tug when I spoke to him last week):

“Tug might’ve been the greatest character I’ve ever met in the game, and there were a lot of characters I’ve met over the years. Tug was the kind of person who, any time, any situation, any place, any circumstance, would say what’s on his mind. He was such an outgoing, gregarious, full-of-life person. He was just very, very special. A fun teammate, a great guy to be around, always seemed to be in a good mood. Just made everybody around him laugh. Along with Koosman on that team, just two of the best teammates you could want. He loved life. A special friend. A special guy.”

The early ’70s should have been Tug’s time. In many ways, they were. He was established reliever with a World Series ring to his credit. The screwjie, or scroogie, however he chose to spell it, got better and better. In 1971 and 1972, he unfurled ERAs of 1.70 in consecutive years, and before you kick that relief pitcher earned run averages don’t tell us much, understand that in those two seasons, Tug threw a combined 217 innings, or precisely as many as Jacob deGrom threw in 2018, when he posted his mind-boggling 1.70 ERA. In ’72, Tug saved 27 games, by far a Mets record (it would go unsurpassed at Shea until Jesse Orosco topped it in 1984) and made the All-Star team, the first Mets reliever to do so.

But Tug wasn’t necessarily the type to feed off success without a struggle. He’d been that way since he was earning his nickname in infancy. One of the most affecting chapters in Screwball revolves around a Mets road trip that took Tug to California in 1970. His parents, already divorced, were around, and he could feel the tension. The shootings of student protesters at Kent State by members of the Ohio National Guard had happened, and Tug couldn’t quickly or quietly tune them out. “I never could believe that the country had reached the point where National Guard guys would have to shoot other people,” he wrote. And the pitcher’s mound didn’t necessarily offer refuge. Even after rescuing the team from a jam at Candlestick Park, Tug found himself “wobbl[ing] into the clubhouse. I got the hell out of sight somewhere in a corner and started sobbing again.”

Tug tried to sum up his feelings in his diary: “I really don’t know in which direction to head or what to do. Why? Because I’m a people and I’m screwed up.”

***Deep into the summer of 1973, no Mets fan would have argued with that assessment. Tug, as personable a people as the Mets had, was screwed up on the mound. He was our most reliable reliever from the previous four seasons, outlasting Taylor and Danny Frisella until he was unquestionably the Fireman of Flushing. Only problem was, in ’73, Tug was downright flammable. Actually, that wasn’t the only problem. The Mets, who’d been a champion once and perfectly competent since, had slid to the basement of the National League East. It wasn’t all McGraw’s fault, but a fireman who extinguished chances to win could be labeled a primary culprit.

When things appeared their bleakest, Tug encountered the power of positive thinking in the person of Joe Badamo. As Tug put it in Screwball, “He sells insurance. Insurance and motivation.” Tug knew Joe through Duffy Dyer, who, along with some other Mets, was introduced to him by Hodges. Badamo may not have been a guru, but Tug was willing to follow what he had to say.

“We rapped a while,” Tug wrote, eventually coming around to the twinned subjects of confidence and concentration, and the only way the motivator said the pitcher could ensure having both was “to believe in yourself. Realize that you haven’t lost your ability. Start thinking positively. Damn the torpedoes, and all that jazz.”

Tug took it to heart. “I said, ‘You gotta believe. That’s it, I guess, you gotta believe.’”

From one conversation with one person, a movement was born. Tug threw “You Gotta Believe” to a few fans and they threw it back to him as if in a game of catch. He brought it into the clubhouse, and it caught on. Without thinking, he blurted it in the middle of a pep talk delivered by chairman of the board M. Donald Grant (and later had to convince the stodgy executive he wasn’t mocking him). “You Gotta Believe” took root in July, when the injury-riddled Mets were still in last place, when Tug was still in his epic 1973 slump.

The spirit that captured New York and conquered the National League was alive and well at Shea Stadium in 1973. It took on a life of its own in September, as the Mets made their move from last place to first place in the space of less than a month. Tug’s year was reborn. Tug on, if you will, this statistical beauty: From September 5 to September 25, as the Mets took 15 of 19, McGraw made a dozen appearances. Every one of them was a personal and team success: he saved nine games and won three more. Eight of the outings were at least two innings long.

The Mets were on their way to the division title, the pennant and a seven-game World Series duel that fell just a touch short of dethroning the Oakland A’s mid-dynasty. Tug was more than a beloved teammate and character by the time it was over. He was a folk hero, a legend, the personification of Belief. By shouting and leaping and pounding his glove to his thigh (and getting batters out by the bushel), he was the Met who made 1973 a miracle of its own. The Mets have never retired “You Gotta Believe” as a catchphrase since then. When things get dark enough to allow in only the slightest glint of light, it’s the light that takes precedence in our collective inner Tug. We gotta believe, we keep telling one another, because in 1973, that’s what Tug told us. Those words would live with us forever.

Yet somehow, Tug McGraw would stay in our immediate company only one year longer.

***The 1974 Mets were the personification of lackluster. Whatever clicked in 1973 failed to make a sound. Same basic cast, same midseason trajectory (a lot of muddling along), but no September magic. Tug didn’t have it again and all the positive thinking in the world couldn’t conjure a miracle. Yogi Berra tried to shake him out of his doldrums by starting him a few games. It worked a little in 1973, before the unbelievable stretch run occurred. It had its moments in 1974, too. On September 1, he blanked the Braves, 3-0, going the distance. It was the last time any Met faced Hank Aaron, who earlier in the year had become baseball’s all-time home run king. It was also the last time Tug McGraw won a game for the Mets. He’d lose several in September to finish 6-11 with a 4.16 ERA and all of three saves. Still, he was embroidered in the fabric of what it meant to love the New York Mets. Tug loved being a New York Met. Didn’t know how to be anything else.

“If I got traded,” he said in Steve Jacobson’s book, The Pitching Staff, “I wouldn’t even know how to put another uniform on.”

He’d get practice.

Joe McDonald touched him and traded him. Tug McGraw, Don Hahn and Dave Schneck to the Philadelphia Phillies for Mac Scarce, Del Unser and John Stearns, not necessarily in that order. Scarce, to be 26 on Opening Day 1975, projected as the direct replacement for McGraw, at least in theory. He was a lefty the Mets had seen plenty over the years. Scarce’s ERA versus New York between 1972 and 1974, covering 13 appearances, was a scant 1.37. If Mac could do something like that against everybody else, you couldn’t say he wouldn’t represent something approximating an upgrade over an older pitcher who’d mostly flailed for two years (save, of course, for a memorable September and October).

Unser, turning 30 himself, was a pro’s pro type. Got to balls in center, made contact at the plate. Hahn wasn’t the answer in New York. Schneck, my own fixation on his name when he came up from the minors in 1972 notwithstanding (I loved that we had a guy named Dave Schneck), never made much of multiple auditions on the major league level. Combined with another fall 1974 acquisition, Gene Clines from Pittsburgh, Del Unser meant the Mets were upgrading their outfield for ’75 for sure.

John Stearns was the real prize if you had a telescope. That was the sell from McDonald. The Phillies had drafted Stearns out of the University of Colorado second in the nation in 1973. He was a football star, but was channeling that aggressiveness into baseball, specifically at catcher, a position where the Mets couldn’t rely on Jerry Grote into eternity. Stearns was 23 at the time of the trade. In ten years, he had a chance to be star.

This was a wise trade on paper. Center field was improved immediately. Catcher was taken care of for the future, at least as much as one could see ahead. The new bullpen lefty certainly hadn’t put up numbers that would make you believe they would be any worse than what you were replacing.

This was a horrible trade in the heart and soul. The Mets traded their heart and soul and threw in a spirit to be missed later. Tug McGraw told us we had to believe. Forgive us if we couldn’t believe this was happening.

The trade from December 3, 1974, proved to be the most frustrating kind. There were no winners. Or, more specifically, there were no losers. Trades where you can gloat that you stole somebody and gave up nobody are the ones you take pleasure in citing for eternity. We cite the Keith Hernandez trade that way. Angels fans cite the Nolan Ryan trade that way, presumably. I wouldn’t blame Phillies fans for feeling perpetually good about getting Tug McGraw as they did. They had a catcher, Bob Boone. They had, after another trade, Garry Maddox in center. They weren’t missing Unser or Stearns. In fact they’d get Unser back down the line.

We wouldn’t miss Hahn or Schneck. Unser was very good in 1975. Batted .294. Gave us defense the likes of which we hadn’t enjoyed since the height of Tommie Agee. Should have made the All-Star team, I will always insist. Then the Mets traded him to Montreal in 1976, sending Del and Wayne Garrett north for Pepe Mangual, Jim Dwyer and a dose of incredulity. Maybe he’d never have another 1975, but Unser’s value as a bench player would endure into the next decade. He’d be part of a certain Phillies team that won a certain world championship.

The Phils didn’t miss Scarce. Neither would we after his exactly one appearance as a Met. It didn’t go well, losing a game as it did. Then Mac was knifed from the Mets’ plans, traded to the Reds for Tom “The Blade” Hall. I honestly thought Scarce wouldn’t be bad. I at least thought he wouldn’t be scarce.

The idea of Stearns taking over behind the plate for the Mets was a great one. It wasn’t only a great idea, it proved a fine reality. After backing up Grote in ’75 and volunteering to get better at Tidewater most of ’76, Stearns became the No. 1 catcher Flushing in ’77. He also became an All-Star for the first time — the first of four times as a Met. Granted, John’s All-Star selections generally fell in that “we have to take a Met” category, somewhere behind the Benches, Simmonses and Carters of the National League, but an All-Star is an All-Star. Bad Dude, as he was called, was solid behind the plate. Took no guff. Didn’t care for losing, which, unfortunately, the Mets of his era did a lot. That wasn’t John’s fault. When he was healthy (which wasn’t always), John led those Mets as far as they could be led. He hung on long enough to see the Mets turn the corner into contention in 1984. He deserved to be part of the kind of team they were becoming. He was one of my favorites of his time.

Any trade that brought us John Stearns and left him with us for a stretch of ten seasons could not be considered terrible. It wasn’t Ryan-for-Fregosi or Otis-for-Foy or any others you care to rue. But it’s hard to say it was a win for New York. New York sent Tug McGraw to another city. That it was a nearby city whose team competed in the same division, and that team was already getting better, and that they’d be in the playoffs perennially, and in the World Series in 1980, and winning the championship that year, and that the man on the mound for the first last out in Philadelphia World Series history would be Tug McGraw…

That’s not a win for us. That’s a win for them. That’s a win for Tug, who had his shoulder fixed once he got down to Philadelphia and pitched very well for essentially the same period that Stearns caught very well. They both lasted until 1984. McGraw, by the time he was done, had passed forty. He lasted a long time. Casey Stengel would have been impressed.

***In the non-aligned popular baseball imagination, I wouldn’t be surprised if Tug McGraw is mainly remembered as a Philadelphia Phillie folk hero, jumping around as he did when they won that World Series. He pitched for them more than he did for us. The video from his Philly exploits is less grainy than the clips from New York. He settled in the Delaware Valley. Did television in the market. Was a regular in Clearwater every Spring. The Phillies embraced him as their own. So did the Mets when a milestone anniversary rolled around, but not as much. It was, in retrospect, similar to Mike Piazza enduring in more minds as a Met rather than a Dodger when all is said and done. Win some, lose some.

Of course, we won’t take the perceptual loss without filing a protest here. We had Tug first. We had Tug plenty. Tug gave us his all before the Phillies were anything to him but another opponent. Tug said, “You Gotta Believe” to us and we never stopped believing. When Tug was diagnosed with brain cancer in 2003, in Clearwater, we felt it in our bones. When Tug died in January 2004, too soon, at the age of 59, it was our loss. It was the Phillies fans’ loss, too. It was a blow to anybody who ever connected heart, soul and baseball.

“Tug is OURS,” says any fan who can claim his legacy. He was ours, but I guess we could share him.

Screwball, coming into my paperback possession as it did in 1975, made those Phillies years better because as long as I could read about Tug being a Met, it was as if he never totally left. Hell, the first time he came back to pitch at Shea, he instinctively headed into the home dugout following the third out of his first visiting inning. Maybe he never fully believed he wasn’t with us. I read Screwball and offered a book report on it in sixth grade. Then in eighth grade. Then in tenth grade. Then it fell off the back of my bike, and I was probably more heartbroken than I was when Tug was traded. In adulthood, I eventually stumbled into a hardcover copy in a used bookstore down the block from Wrigley Field and cherish its words if not its format to this day.

The paperback was as prized a possession as I ever had baseballwise. I prize, too, that I got to tell Tug McGraw about it. By some great turn of fortune, I was given a ticket to a baseball alumni dinner in 1999. One of the old-timers on hand was Tug, then 55. He was gregarious as ever. I went up to him with a baseball for an autograph, as was encouraged by the organizers. I’m sorry I didn’t have a copy of the book on me, any copy. But I did tell him about it. I told him I read Screwball over and over and over, and I did three book reports on it, and that I probably would have kept doing book reports on it had it not gone missing.

Tug McGraw stared into my eyes and told me, “You’re scarin’ me, man!” and laughed uproariously as he handed me back the baseball. You believe that?

PREVIOUS METS FOR ALL SEASONS

1962: Richie Ashburn

1963: Ron Hunt

1964: Rod Kanehl

1965: Ron Swoboda

1966: Shaun Fitzmaurice

1967: Al Schmelz

1969: Donn Clendenon

1970: Tommie Agee

1971: Tom Seaver

1972: Gary Gentry

1973: Willie Mays

1977: Lenny Randle

1978: Craig Swan

1981: Mookie Wilson

1982: Rusty Staub

1983: Darryl Strawberry

1986: Keith Hernandez

1988: Gary Carter

1990: Gregg Jefferies

1991: Rich Sauveur

1992: Todd Hundley

1993: Joe Orsulak

1994: Rico Brogna

1995: Jason Isringhausen

1996: Rey Ordoñez

1998: Todd Pratt

2000: Melvin Mora

2001: Mike Piazza

2002: Al Leiter

2003: David Cone

2004: Joe Hietpas

2005: Pedro Martinez

2007: Jose Reyes

2008: Johan Santana

2009: Angel Pagan

2010: Ike Davis

2012: R.A. Dickey

2013: Wilmer Flores

2014: Jacob deGrom

2019: Dom Smith

by Greg Prince on 7 September 2020 11:25 pm “Whoa, there he is! Whadda you doin’ around here?”

“I had’ta take a walk, get outta the house. I love my wife and kids, honest to God I do, but I love ’em more with a little ‘social distance’ now and then, get my drift?”

“I hear that. It’s been a long year this week.”

“What about you? What brings you out here to the park?”

“Labor Day picnic. Don’t you remember? We would do this every year.”

“Labor Day — right. I can’t remember from one day to the next what day is what. So they’re still doin’ this? Remember, I haven’t been with the company in like three years.”

“Yup. The bosses thought they’d do us a big favor one last time.”

“Last time? What’s up?”

“You hadn’t heard? They’re sellin’ the company.”

“For real? We used’ta hear those rumors all the time, but I learned to drown ’em out.”

“Supposedly it’s all frank and earnest. I mean nothin’s official, but it’s what everybody’s sayin’. Real rich guy takin’ over. We’ll see.”

“No kiddin’. Remember, we were always sayin’ ‘they oughta sell, but they never will.’”

“I hear that. But it looks like it’s goin’ down, and soon.”

“So they’re havin’ one last Labor Day blowout for the employees, huh? Mighty big of them.”

“They got sentimental, I guess. I didn’t think they’d be doin’ anything this year, with everything crazy, but here they are, gettin’ ready for the tournament, or so they hope.”

“What tournament?”

“You been outta the loop, huh? There’s a whole thing. Top eight teams go. We may or not make it. So what should just be fun today is gettin’ kinda serious out there.”

“Yeah, I haven’t really paid attention in a few years. It’s hard to see from here who’s playin’.”

“I know. They won’t let us get too close. It’s weird that they’re havin’ this without anybody allowed to watch.”

“Everything’s weird these days. God, I guess I haven’t been by in ages. Hey, is that Zack? How’s he doin’?”

“He’s doin’ great, but take a closer look at his shirt. He ain’t with us no more.”

“No, I guess he’s not. What gives with that?”

“Zack wanted a raise. The bosses told him no dice, Zack went across the street.”

“He got his raise, huh?”

“And then some. I think he’s takin’ some pleasure today in stickin’ it to the old gang.”

“Well, good for him. I’d do it if I could.”

“Who wouldn’t? Loyalty is whatever gets ya to the first of the next month.”

“Who ya got instead of Zack?”

“Some kid who looked good for a while earlier, but today not so much. They replaced him as soon as they could with somebody I don’t really know. He’s listed as a journeyman in the company directory, but from what I can tell, he’s doin’ good for himself.”

“I’m tryin’ to make out his name from here. I think it’s written in marker.”

“Yeah, he wasn’t even supposed to be here today.”

“Erasmus? Is that it? I had an aunt or great aunt or something who went to high school there, in Brooklyn. Erasmus Hall.”

“Whatever his name is, he seems OK.”

“Jake still here, or did he want a raise, too.”

“Oh, Jake’s still here. Him they gave a raise. He was worth it. They probably wish they could have him out there every day.”

“The union wouldn’t go for that, I’ll bet.”

“Management couldn’t fuck up Jake. Give them a chance, they’ll try.”

“Yeesh. Hey, what about that guy I heard about, the Polish Bear?”

“Watch it. Nobody has a sense of humor about that stuff anymore.”

“What? What did I say? I didn’t mean anything by it.”

“It’s Polar Bear. Between you and me, nobody’s really talkin’ about him that much this year.”

“Where is he? Is he on the field?”

“Not today. I mean he’s playin’, but he doesn’t have what you or I would call a position.”

“They’re doin’ that now? Oh, for…”

“Uh-huh. All kinds’a weird shit this year. They said it’s because of the Corona. I don’t know.”

“What about that big klutz they brought in? You know, with the bat sometimes, but really raw. Good kid, but seemed lost.”

“Dom?”

“Yeah, Dom, that’s it. He still here?”

“He’s still here. I didn’t have a lot of faith in him either, but he’s kind of figured out what he’s doin’. It’s good to see. The guys really like him.”

“Great. And Michael? He was gonna be good, but that manager we had was all weird about trustin’ him.”

“That was fuckin’ bizarre, wasn’t it? Yeah, Michael’s still here. They leave him alone and let him do his thing, and they’re better off for it.”

“And that skinny kid from out west, always pointin’ to the sky?”

“Brandon?”

“That’s it — Brandon.”

“He’s still here. Still pointin’ to the sky. Funny guy, sorta, but he makes himself useful.”

“Great. Hey, what about that other kid, the one everybody was gettin’ all excited about for a while. Anwar…Amstel…”

“Amed?”

“That’s right, Amed. Everybody was all, ‘can’t wait for Amed, Amed’s gonna be the man.’ How’d that work out?”

“Funny you mention that. Amed’s probably gonna hafta go to HR pretty soon.”

“What, did he make a Polish Bear joke, too?”

“Nah, they just gotta find another job for him or transfer him or something.”

“What happened to his old job? Automation?”

“Take a look out there. See that kid runnin’ around, gettin’ to everything, takin’ charge, just fuckin’ knowin’ what he’s doin’ like he was born to do it?”

“Oh yeah. Nice. Who is that?”

“That’s Andrés. He’s pretty much got Amed’s job now.”

“I can see why. Jeez, he’s smooth. How old is he anyway?”

“Just turned 22. He’s gonna make everybody look bad by comparison — or make the whole department look good if they let him handle everything like he’s doin’ today.”

“Holy crap, 22. That’s young. How old is Amed?”

“Amed’s 24.”

“That ain’t old either.”

“It ain’t. But ya know how this business is. It’s what’ve ya done for me lately, whaddaya gonna do for me tomorrow? André’s got today on lock and he’s got tomorrow right in front of him.”

“Not a bad place to be.”

“Not bad at all.”

“Crazy.”

“Uh-huh.”

“So they gonna win or what?”

“The rest of the way? Who knows? Today? Uh…nah, doesn’t look like it. I don’t even know who we’ve got on the mound right now. I think he joined the company right around the time Erasmus Hall did. I can’t keep track of everybody the bosses hire and fire.”

“Still a lotta turnover here, huh?”

“You don’t know the half of it. This guy pitching, though, they may let him go before the inning is over.”

“Not good, huh?”

“Maybe, maybe not. Who can tell anymore?”

“Hey, when did he put a runner on second? Seriously, I didn’t even see that. Weren’t they just ahead? Didn’t that guy they were all yellin’ ‘SQUIRREL!’ at do something and everybody was goin’ nuts?”

“I don’t know. I never know. Everything changes so fast. Blame it on this fuckin’ year. It’s crazy.”

“I hear that.”

by Greg Prince on 6 September 2020 8:18 pm In a sixty-game season with all the irregularities passed off as the new normal, it wouldn’t have been terrible to have halted Sunday afternoon’s Mets-Phillies game once it went official. Not for the usual reason that the Mets led after four-and-a-half and the bullpen later blew up, but because, in the middle of fifth inning of the 41st game on the schedule, the Mets led, 4-1, with the Mets’ pitcher of record the closest thing we’ve seen in some time to No. 41.

The Mets kept playing, the Mets kept scoring and we’d have to “settle” for a 14-1 Mets win, which is close enough to the numerical Tom Seaver salute I had in mind (to say the least). The presence of Sunday’s No. 41 stand-in might have worn No. 48, but Jacob deGrom channeled the Seaverian spirit as well as could have been hoped for.

This was the Met tribute I’d been waiting for since we learned of Tom’s passing. Moments of silence, smudges of dirt and patches in black were all properly respectful, but nothing could pay most Terrific homage like a most Terrific outing by the reigning Met ace. We surely had the right man on the Citi Field mound to take care of the stylistic and statistical details.

Jacob deGrom was about as good as he usually is, which is to say he was the best pitcher in baseball on Sunday. He went seven innings, the 2020 equivalent of nine, and he all but shut down the Phillies, allowing one run on three hits (Andrew Knapp’s first-inning homer the only actual damage). Dealing fastballs and sliders, Jake walked two and struck out twelve. Seventy-four of deGrom’s 108 pitches were strikes; thirty-five of his 74 strikes were swung on and missed. Nobody had eluded that many bats in a major league game in more than four years.